FTC Meta Monopoly Appeal: What's Really at Stake [2025]

When the Federal Trade Commission announced it would appeal a November ruling that cleared Meta of monopoly charges, nobody was particularly shocked. What did raise eyebrows, though, was the subtext: this case isn't just about Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions anymore. It's become a proxy war over antitrust law, judicial independence, political pressure, and what competition even means in an age where TikTok didn't exist when Facebook acquired Instagram.

The stakes are genuinely massive. If the FTC wins on appeal, Meta could be forced to divest Instagram or WhatsApp, fundamentally restructuring one of the world's most valuable companies. If Meta holds, it sets a precedent that platform acquisitions are fair game as long as the market's "competitive." But the real story is messier than the legal arguments. It involves Trump's relationship with Zuckerberg, a judge facing impeachment threats from Republicans, and a regulatory body trying to figure out whether "personal social networking" is even a market anymore.

Let me walk you through what happened, why the original ruling went Meta's way, and what could happen next.

The Original Case: What the FTC Was Actually Trying to Prove

The FTC's case against Meta started simple enough on the surface, but got complicated fast. The agency alleged that Meta maintained an illegal monopoly in "personal social networking services" through anticompetitive conduct. Specifically, the FTC pointed to two acquisitions as the smoking gun: Instagram in 2012 (for roughly

The FTC's argument was straightforward. In 2012, Instagram was becoming a legitimate threat to Facebook. It was growing faster, had better engagement, and represented what many users considered the future of social networking: photo-first, real-time, minimal algorithmic interference. So Meta didn't compete. It bought Instagram instead, removing the threat. Then WhatsApp came along with a different value proposition—encrypted messaging without ads. Again, potential threat. Again, Meta bought it.

According to the FTC, this pattern showed Meta identified competitive threats and eliminated them through acquisition rather than competing fairly. Over a decade, this created a monopoly in personal social networking that let Meta degrade service quality (more ads, worse experiences) without losing users because there were nowhere else to go.

The remedy the FTC sought was dramatic: force Meta to divest Instagram and/or WhatsApp, breaking the company apart. This wasn't a fine or a behavioral remedy. This was structural—actually break up the company.

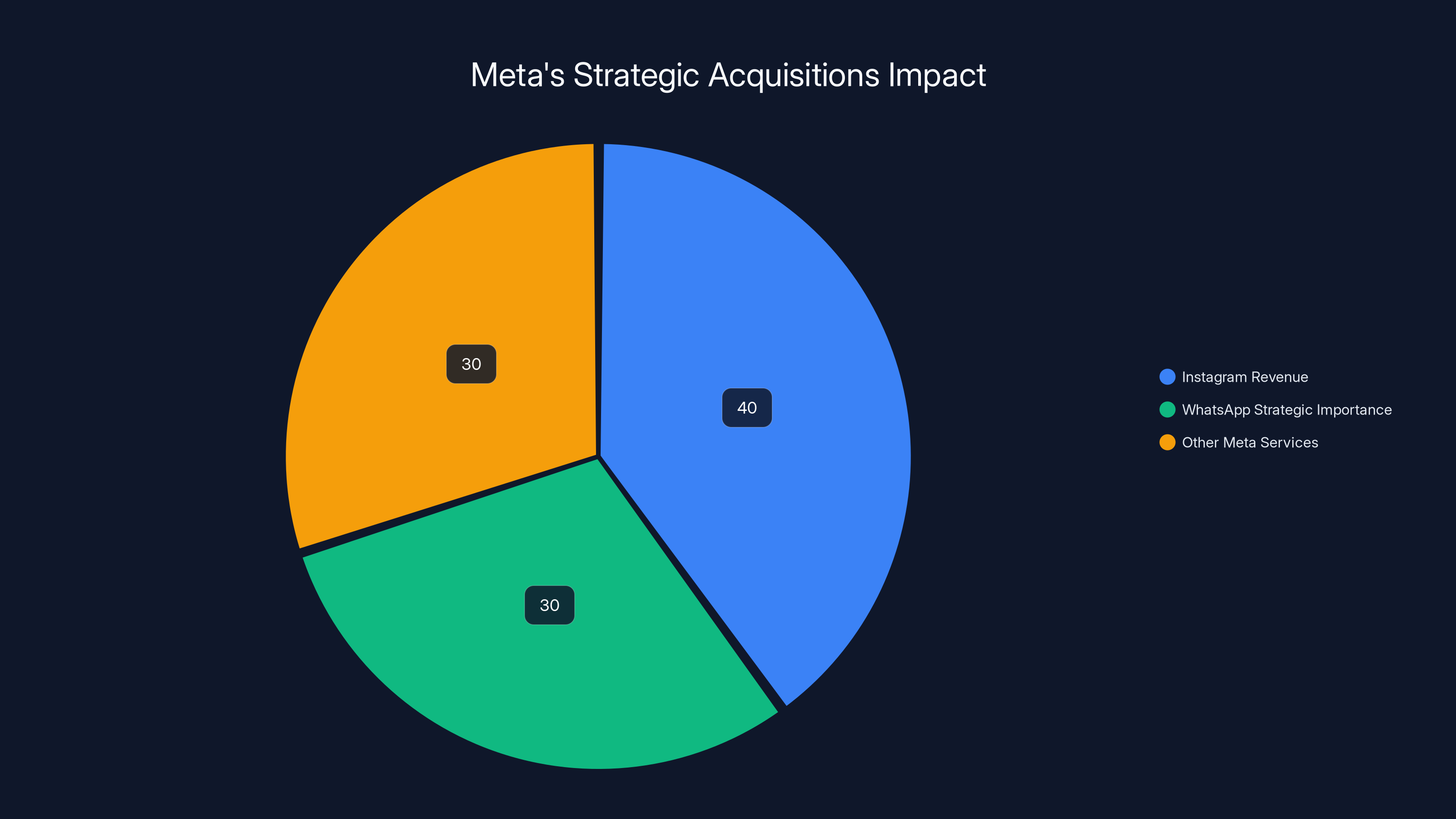

For Meta, this represented an existential threat. Instagram today represents a huge chunk of the company's revenue and user engagement. WhatsApp, while less profitable, is strategically important in emerging markets and represents the company's bet on messaging services. A forced divestment could've created two or three independent companies, fundamentally changing the competitive landscape.

But here's where it gets interesting: Judge James Boasberg didn't buy the FTC's argument.

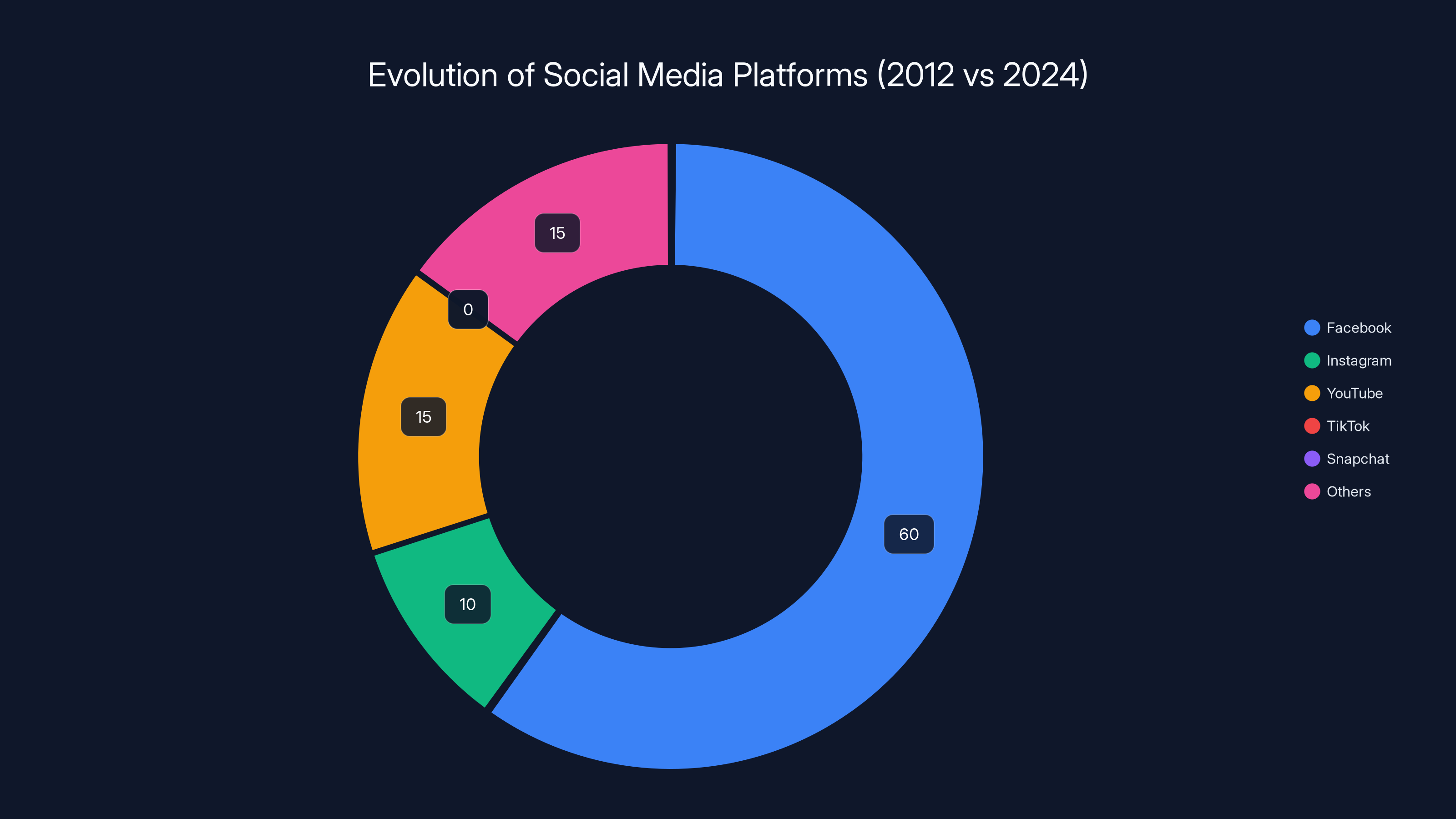

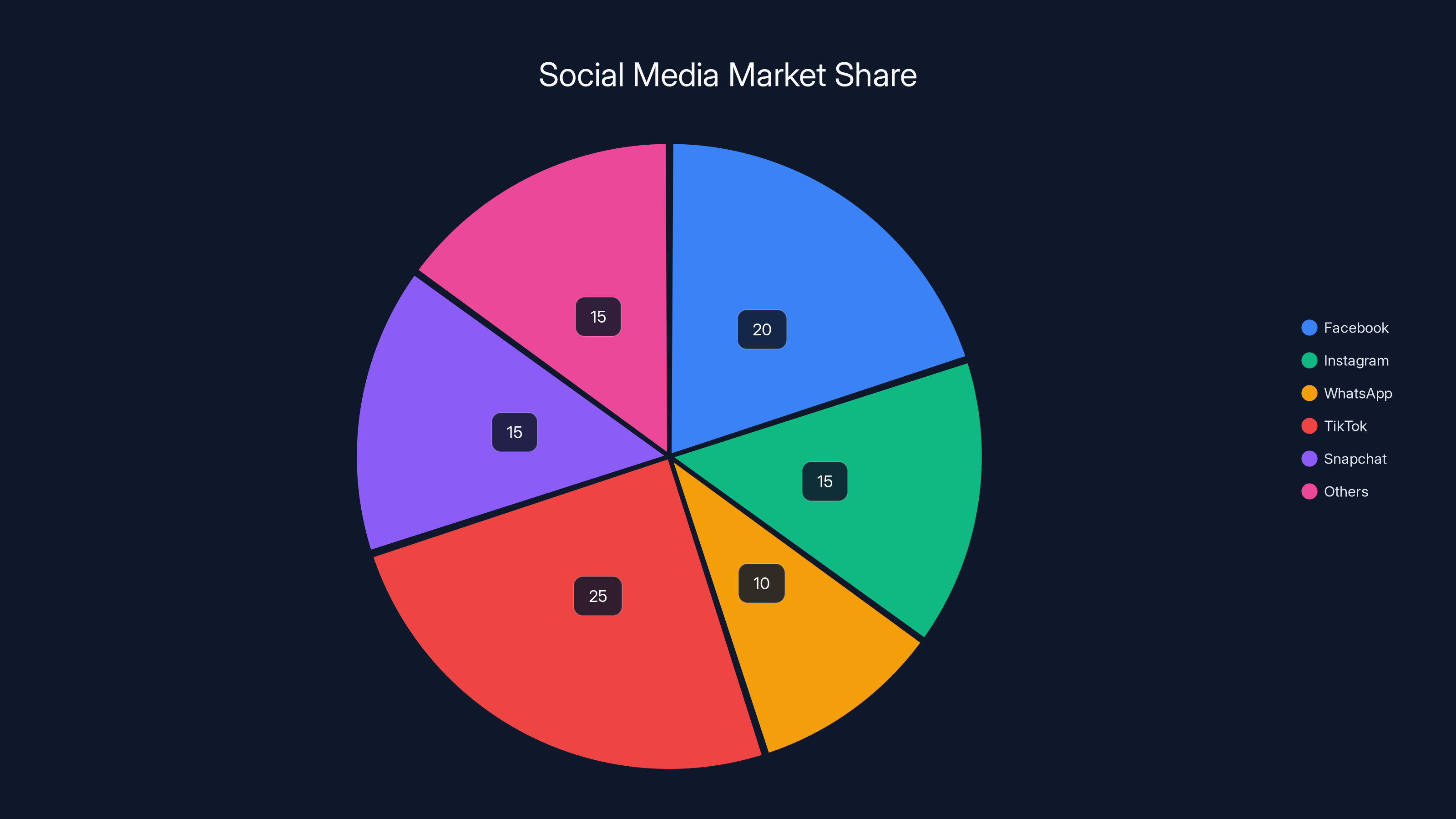

Estimated data shows TikTok holds a significant share in the personal social networking market, challenging Meta's dominance.

Why Judge Boasberg Sided with Meta

Boasberg's November ruling wasn't a gut-punch to the FTC just because he disagreed with their economic theory. The ruling identified specific, concrete problems with how the FTC defined the market and made their case.

First, there's the market definition problem. The FTC argued Meta had a monopoly in "personal social networking." But Boasberg asked a practical question: what actually is that market? The FTC said it included Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. Everyone else? Out of scope. This is crucial because if you define the market narrowly, you can make Meta look dominant. But if you define it broadly, the picture changes completely.

Boasberg's key insight was that Instagram and TikTok are functionally interchangeable from a user perspective. Yes, they have different features, but they serve the same need: scrolling through visual content, discovering new creators, maintaining connections with friends. For a teenager in 2025, Instagram and TikTok are basically the same product with different interfaces. You're not forced to use one if you don't want to—you can just use the other.

This matters because it means Meta doesn't face zero competition. TikTok is a massive competitor. It's worth over $50 billion (when China's willing to sell it). It's where younger users increasingly spend time. It's where content trends originate. By any reasonable measure, TikTok competes with Instagram. If you include TikTok in the market, Meta's share drops significantly, and defining it as a monopoly becomes much harder.

Second, Boasberg looked at the FTC's argument that Meta was degrading service quality. The FTC claimed Meta added more ads and decreased experience quality precisely because it had a monopoly and users couldn't leave. But Boasberg found evidence that Meta continuously improved its apps, adding new features, updating the algorithm, responding to user feedback. Instagram in 2024 is objectively more feature-rich than Instagram in 2014. Both apps have more ad load, sure, but that's industry-wide. Snapchat also runs ads. TikTok absolutely runs ads. This isn't abuse of monopoly power—it's the business model for free social platforms.

Third, there's the temporal problem. When Meta acquired Instagram in 2012, the competitive landscape was fundamentally different. Facebook was the dominant social network, but the concept of social media was still evolving. Twitter was about news and public figures. Instagram was about photos. Snapchat didn't exist yet. YouTube was video, not social discovery. The idea of grouping all these into separate markets made sense in 2012.

But by 2024, that distinction has collapsed. Boasberg emphasized that "the Court finds it impossible to believe that consumers would prefer the versions of Instagram and Facebook that existed a decade ago to the versions that exist today." The products evolved. The markets merged. You can't prosecute a 2012 acquisition based on 2024 market conditions when market conditions have changed fundamentally.

Lastly, there's the structural problem with the remedy. Even if you accepted the FTC's market definition from 2012, forcing a divestment in 2024 is a different question. Instagram didn't exist as an independent company for over a decade. The tech stack is integrated. The ad systems are integrated. The infrastructure is integrated. Unwinding that would be chaos. Who runs the divested Instagram? How does it keep its user data when it's been fed into Meta's systems for 12 years? What's the licensing arrangement for underlying technology? Boasberg implied that the FTC wanted to undo the clock on an acquisition that was legal when it happened, based on market conditions that have since changed.

All of this is why Boasberg ruled in Meta's favor.

The Political Context That Nobody's Ignoring

But here's the thing that makes this case genuinely weird: the politics are impossible to ignore.

Donald Trump has a personal grudge against Meta. He's been vocal about it. In 2017, he called Facebook and Zuckerberg "anti-Trump." Then in 2021, Meta banned Trump from Facebook and Instagram after January 6th. Trump sued. Meta fought back. It was messy.

Now, heading into Trump's second term, Zuckerberg has been performing diplomacy. He donated

Meanwhile, Judge Boasberg—who ruled for Meta—is facing impeachment threats from Republican lawmakers. Specifically, Brandon Gill proposed articles of impeachment, claiming Boasberg is a "rogue partisan judge" abusing power to silence conservatives. No serious action came of this, but the signal was clear: there's partisan pressure on the judge.

The FTC, under Biden, pursued this case aggressively. The current administration (still Biden when the ruling came down) represented a more activist antitrust position. But Trump's second term is beginning, and his approach to tech regulation is famously friendly to billionaires, especially when they've recently made large political donations.

When FTC spokesperson Joe Simonson announced the appeal, he specifically noted that the case originated during Trump's first term, when Trump was frustrated with Facebook. The implication was stark: we're not giving up on this, even though the new administration might prefer we do.

Meta's response was carefully diplomatic. The company's legal chief said they "look forward to continuing to partner with the Administration and to invest in America." Not exactly a victory lap. More like: we know the political winds have shifted, we're hoping you don't push this further, and we're obviously your friend.

What's genuinely unclear is whether a different judge (which a new trial would mean) would see this case differently now that the political context has changed. If Trump's Department of Justice is less interested in aggressive antitrust enforcement, that pressure could influence judicial decision-making, whether intentionally or not.

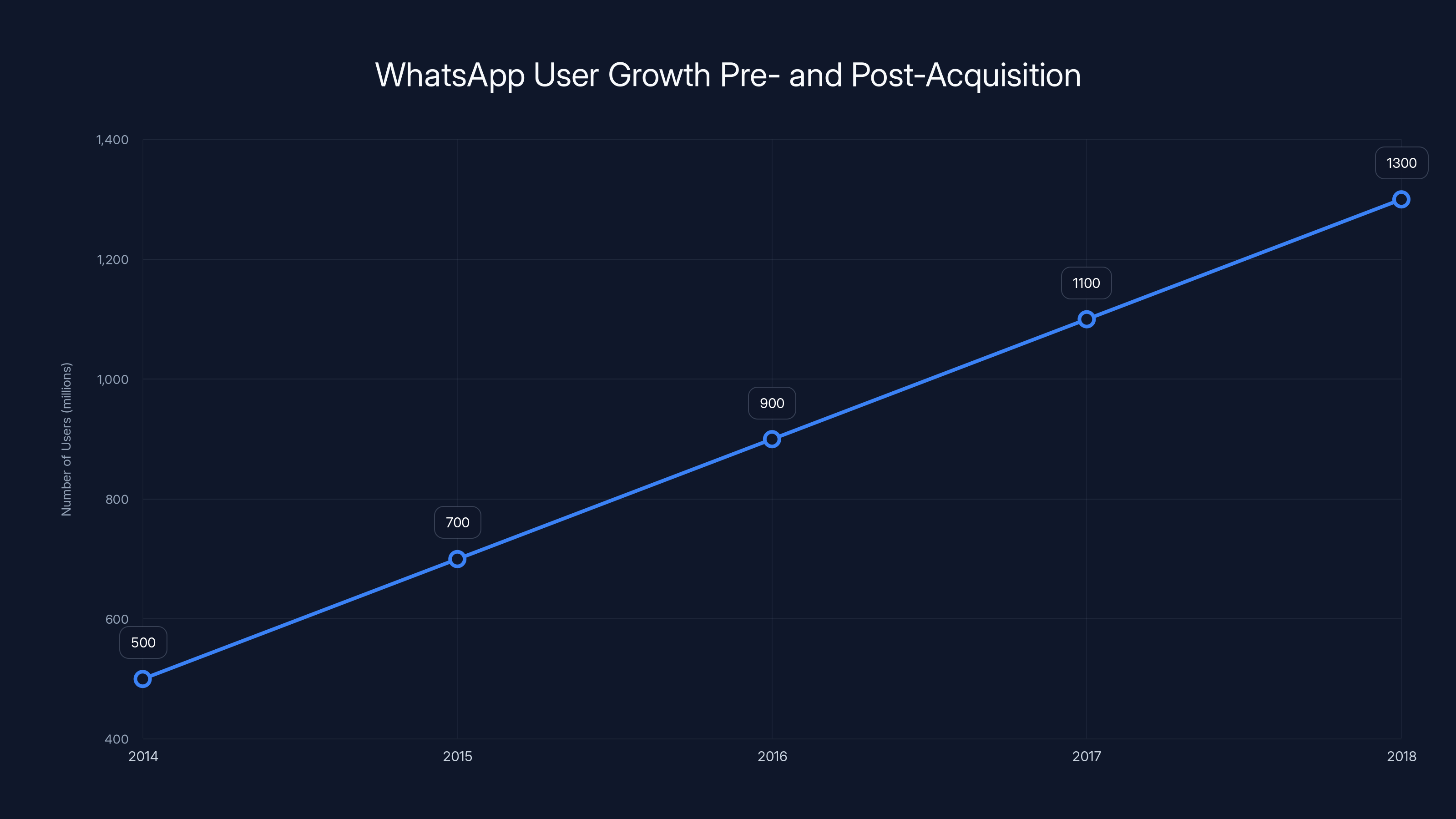

WhatsApp's user base grew from 500 million in 2014 to an estimated 1.3 billion by 2018, highlighting its rapid expansion and strategic value to Meta. Estimated data.

What Changed in Social Media Since 2012?

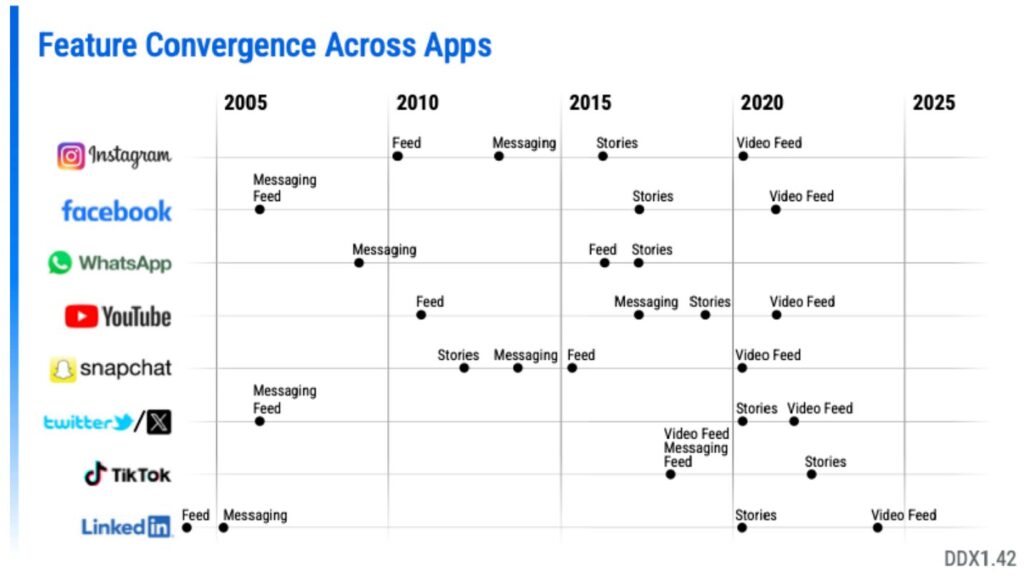

To understand why Boasberg's market definition argument is so powerful, you need to grasp how drastically social media has transformed in 13 years.

In 2012, when Meta acquired Instagram for

The key insight from 2012: these were perceived as separate markets. Facebook = social network for connecting with friends. Twitter = news and public conversation. Instagram = photos. The FTC could credibly argue that Meta was buying Instagram to own "personal social networking," a distinct market from other platforms.

But by 2024? The lines have completely blurred. Instagram evolved from just photos into video (Reels), stories, messaging, shopping, and basically everything TikTok does. Facebook became less relevant. YouTube became a social network for discovery, not just video hosting. TikTok became the dominant platform for younger users, serving the exact same function as Instagram: discovering content, following creators, casual entertainment. Snapchat evolved too—it's also doing everything Meta's doing now.

The modern reality: there isn't a coherent "personal social networking" market anymore. There's a broader "social media" market with multiple overlapping platforms. Users aren't locked into one. A teenager might split time between Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, BeReal, Discord, and YouTube. They're not forced to choose Instagram just because it's the only option in some narrow market definition.

This is why Boasberg's ruling makes sense legally. You can't prosecute a 2012 acquisition in a 2024 market condition where market conditions have shifted completely.

But the FTC's counter-argument is: yes, you can, because Meta's actions deliberately shaped the market to prevent competition. By acquiring Instagram and integrating it, Meta prevented the market from developing naturally. If Instagram had remained independent, it might've been a standalone company today worth $100+ billion. That's lost competition caused by the 2012 acquisition. The fact that the market has evolved differently than it would have suggests Meta's acquisition was anticompetitive.

This is a genuinely tough question legally. And that's probably why the FTC is appealing—there's legitimate disagreement here.

The Appeal Process: What Happens Next

When the FTC appealed Boasberg's ruling, the case went to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. This is a big deal because the DC Circuit is where most major antitrust appeals go. It's prestigious, important, and the judges there take tech regulation seriously.

The appeals court will look at Boasberg's ruling and decide: did he get the law right? Did he misapply antitrust principles? Did he abuse his discretion in interpreting market definitions? The appellate court doesn't retry the case. It reviews whether the original judge applied the law correctly.

For the FTC, the path to victory requires convincing the appeals court that Boasberg made an error in defining the market too broadly (by including TikTok) or in concluding that Meta wasn't degrading service quality. The FTC will argue that the 2012 market definition was correct at the time, and Meta's acquisitions were designed to prevent competition specifically in that defined market.

For Meta, the path is easier: they need the appeals court to agree with Boasberg that markets have evolved, that competition is vigorous (TikTok proves it), and that service quality hasn't degraded despite increased ad load (because ad loads are industry-wide).

Historically, appeals courts are skeptical of antitrust cases. They want clear evidence of competitive harm, not just concerns about market structure. The FTC has to prove that consumers were actually harmed by Meta's acquisitions. Boasberg found they weren't—Instagram and Facebook offer better features today than they would have if they'd remained separate competitors. That's a high bar for the FTC to clear on appeal.

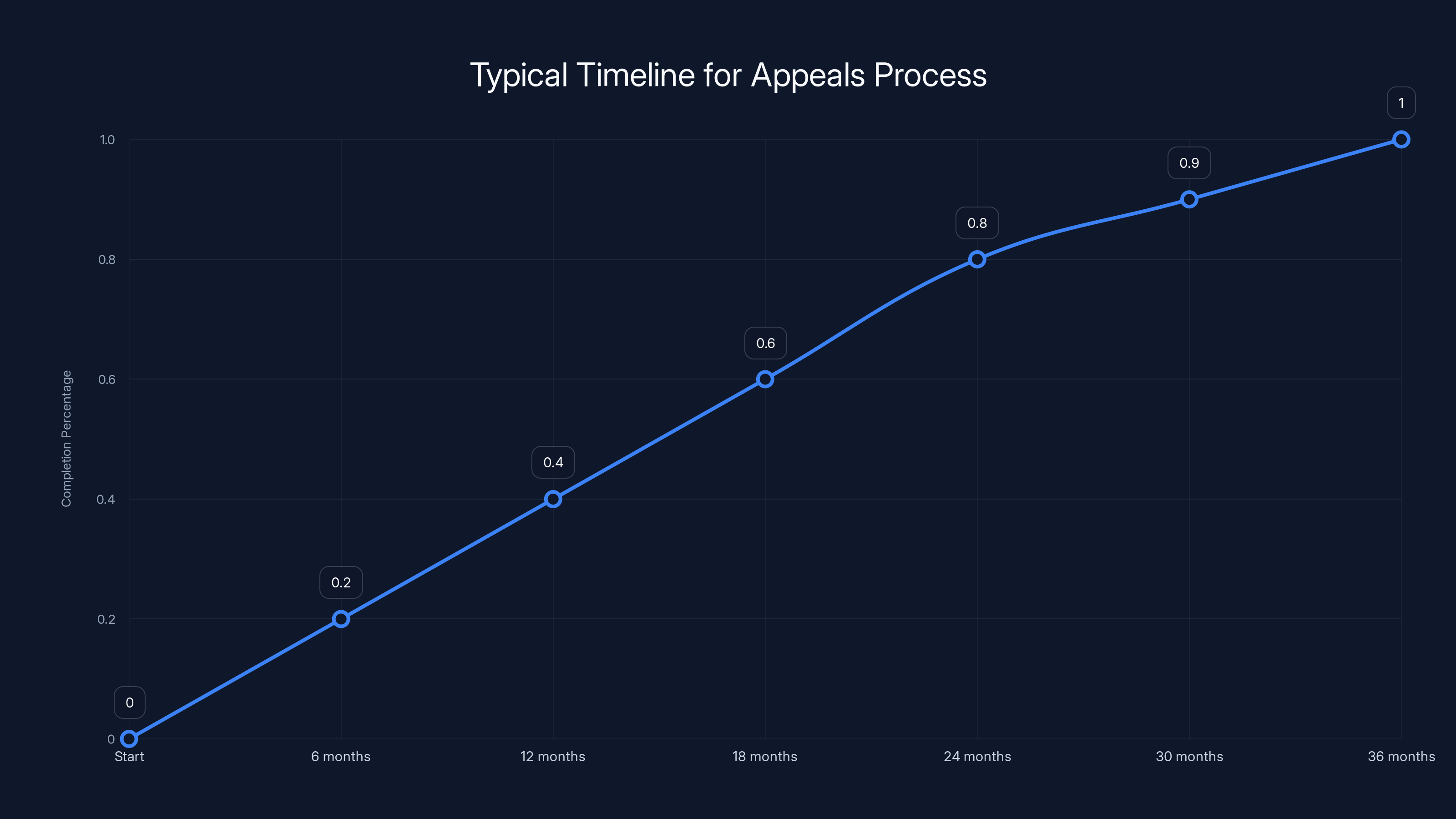

The timeline is unclear. Appeals can take 18 months to three years. So this case could drag on through the Trump administration and potentially into 2026 or beyond.

How Antitrust Law Actually Works (It's More Complicated Than You Think)

Understanding this case requires understanding modern antitrust law, which is genuinely confusing because antitrust law itself is in the middle of a philosophical shift.

Traditionally, antitrust enforcement focused on "consumer harm." Does the monopoly hurt consumers? If the company is providing good service at reasonable prices, antitrust law doesn't care if it's a monopoly. This is called the "consumer welfare standard," and it dominated antitrust thinking from the 1980s onward.

Under the consumer welfare standard, Meta's acquisitions look fine. Instagram users got better service (integration with Facebook's infrastructure, better algorithms, new features). Facebook users got access to Instagram's features through Facebook. WhatsApp users... well, WhatsApp has been stagnant, which is arguably not great, but they still have end-to-end encryption and a clean interface.

Consumers have more choice than ever. You can use TikTok, Snapchat, YouTube, Discord, BeReal, Mastodon, Threads, Bluesky, Twitter/X. Yes, Meta owns multiple platforms, but users aren't forced to use Meta's ecosystem. That's the Meta defense.

But there's a newer school of antitrust thought that focuses on "competition on the merits." This perspective says antitrust should prevent dominant companies from buying potential competitors specifically to prevent competition, even if consumers temporarily benefit. The concern is: yes, Instagram is better now as part of Meta. But what if Instagram had remained independent? It might've competed differently, innovated differently, and provided consumers with more choice. By acquiring Instagram before it could become a genuine competitive threat, Meta prevented that future competition.

The FTC's case leans toward this newer thinking. The argument is: Meta identified Instagram as a serious competitive threat, and rather than compete with it, Meta bought it. This prevented competition "on the merits." Even if consumers like Instagram today, the fact that competition was foreclosed is the harm.

Boasberg, in his ruling, basically sided with the older consumer welfare standard. He looked at current conditions and asked: are consumers being harmed? His answer was no. They have choices. Service quality is good. Prices are free (ad-supported). Therefore, no antitrust violation.

This disagreement about what antitrust law should do is the real crux of the case. And it's a genuinely unsettled question in American antitrust law right now.

The social media landscape has shifted significantly from 2012 to 2024, with platforms like TikTok emerging and Instagram expanding beyond photos. Estimated data shows a more diversified market share.

The WhatsApp Acquisition and Its Different Story

While the Instagram acquisition gets most attention, the WhatsApp acquisition is actually interesting and under-discussed in coverage of this case.

Meta acquired WhatsApp in 2014 for $19 billion. At the time, it was the most expensive app acquisition ever. WhatsApp had 500 million users. It was growing at 50 million new users per month. It was encrypted. It was minimal-ad (basically no ads). It was simple.

Why would Meta pay $19 billion for an app with minimal revenue? The FTC's answer: because it was a competitive threat to Messenger. Facebook's Messenger was struggling. WhatsApp was the dominant messaging app globally. By acquiring WhatsApp, Meta consolidated messaging under its control.

More interesting: Meta integrated WhatsApp's user base and backend into its systems but kept WhatsApp's user interface and brand separate. WhatsApp today is still WhatsApp. But it's connected to Meta's infrastructure, and Meta uses WhatsApp data for targeting ads on other Meta properties. This integration happened slowly and secretly. WhatsApp's original co-founders, Jan Koum and Brian Acton, had promised users that WhatsApp would remain ad-free and private. After Meta's acquisition, that promise gradually eroded.

Jan Koum eventually left Meta in 2018, reportedly frustrated that Meta was using WhatsApp data for ad targeting, contradicting the original promise to WhatsApp users. This is a concrete example of what the FTC means by Meta leveraging an acquisition to integrate a competitor.

Boasberg's ruling sort of dismissed this concern. He noted that WhatsApp isn't really a social networking app in the sense that Facebook is. WhatsApp is messaging. It's a different market. Therefore, even if Meta acquired WhatsApp to prevent competition, it doesn't necessarily violate antitrust law in the "personal social networking" market.

The FTC might argue on appeal that this misses the point: Meta's strategy was to acquire any platform that could become a vehicle for social communication, then integrate it into the Meta ecosystem. It's about preventing competitors in any form of communication technology. But Boasberg's narrower reading was that antitrust law as written focuses on specific markets, and WhatsApp isn't in the social networking market.

This distinction matters for the appeal. If the appeals court sides with the FTC's broader view of what competition Meta was foreclosing, the WhatsApp acquisition could become more central to the case.

TikTok as the Game-Changing Competitor

Here's what makes this case genuinely confusing for antitrust purposes: TikTok.

TikTok didn't exist when Meta acquired Instagram. TikTok launched in 2016 as Musical.ly, then became TikTok in 2018. By 2020, TikTok had 500 million users and was the fastest-growing social app ever. By 2024, TikTok has 1.5 billion users globally and is genuinely Instagram's biggest competitor.

This creates a timing problem for antitrust. The FTC's case is basically: "In 2012-2014, Meta acquired Instagram and WhatsApp to prevent competition." But the biggest competitor to Instagram, TikTok, didn't exist in 2012-2014. So did Meta actually create a monopoly if a bigger competitor emerged after the acquisitions? Or does TikTok's existence prove the market is competitive?

Boasberg said it proves competition is vigorous. Meta doesn't face zero competition because TikTok exists and is crushing it with younger users. Therefore, no monopoly.

The FTC's counter-argument is: yes, TikTok is now a huge competitor, but that doesn't vindicate Meta's 2012 acquisition. It just means Meta got lucky that a different company (ByteDance) out-innovated them. If Instagram had remained independent in 2012, Instagram plus TikTok might have created a different competitive dynamic. ByteDance might've acquired Instagram instead. Or Instagram might've become a public company. Or it might've integrated with TikTok's features earlier. The point is: we'll never know because Meta bought it.

This is the cleanest version of the FTC's argument. Meta bought out its competitors preemptively, preventing the market from developing naturally. Yes, TikTok emerged as a new competitor, but that doesn't retroactively make the 2012 acquisition competitive. It just means the market eventually became competitive anyway despite Meta's attempts to foreclose competition.

Boasberg's counter is pragmatic: we can't undo the clock. We can't know what would've happened in an alternate universe where Instagram stayed independent. We can only look at current market conditions and ask: is competition happening now? Yes. Are consumers being harmed? No. Therefore, no remedy is warranted.

This disagreement is probably what the appeals court will focus on.

Why the FTC Might Lose on Appeal

Let's be honest: the FTC has an uphill battle here. Not because the law is clearly in Meta's favor, but because of several structural problems with the FTC's case.

First, there's the market definition problem. The FTC's definition of "personal social networking" is pretty narrow and somewhat arbitrary. Why those apps and not others? The FTC says Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat are in the same market, but TikTok is different. But why? They all serve the same function. Boasberg asked this question and found the FTC's answer unconvincing. Appeals courts tend to defer to judges' factual findings unless they're clearly unreasonable. Boasberg's finding that the market includes TikTok seems reasonable to most observers.

Second, there's the passage of time problem. Meta acquired Instagram in 2012. WhatsApp in 2014. We're now in 2025. If these acquisitions violated antitrust law, why did it take until 2020 for the FTC to file suit? Why did it take until 2025 to get a ruling? In antitrust law, there's a concept of laches—unreasonable delay. If Meta's behavior was so obviously anticompetitive, shouldn't the FTC have moved faster? This doesn't automatically bar the case, but it makes judges skeptical.

Third, there's the consumer benefit problem. The FTC has to prove that consumers were harmed. But Instagram is objectively better as part of Meta. It has more features, better integration, superior algorithms. How do you argue that Instagram users were harmed by Meta acquiring Instagram when the product they use today is demonstrably better because of the acquisition? This is a huge problem for the FTC. They're basically arguing: "Yes, consumers got a better product, but they should have gotten an even better product if Instagram had remained independent." That's a hard sell to judges.

Fourth, there's the remedy problem. If the FTC wins, what's the remedy? Force Meta to divest Instagram? But Instagram has been integrated into Meta's systems for 13 years. Unwinding that is technically complex and might actually harm consumers by breaking a unified system. Do you force Meta to keep Instagram integrated but operate it independently? That's weird and hard to enforce. The lack of a clear remedy that would actually benefit consumers makes judges reluctant to rule for the FTC.

All of these factors work against the FTC on appeal.

Estimated data shows TikTok as a significant player in the social media market, reducing Meta's dominance when considering a broader market definition.

Why the FTC Might Win on Appeal

That said, the FTC isn't totally without a case.

First, there's historical precedent. The Supreme Court has previously held that companies cannot acquire potential competitors for the purpose of eliminating future competition, even if consumers benefit in the short term. The classic case is United States v. Alcoa (1945), where the Court found that Alcoa's vertical integration practices violated antitrust law because they foreclosed competitors, even though Alcoa's prices were reasonable.

The FTC's argument is: Meta did the same thing. Meta identified Instagram and WhatsApp as potential competitors, acquired them before they could pose a serious threat, and integrated them into Meta's ecosystem. This foreclosed competition, even though consumers technically benefit from the integration.

Second, there's the predatory pattern argument. Meta didn't just acquire Instagram once and move on. The company has a documented pattern of acquiring potential competitors: Instagram, WhatsApp, and also companies like GIPHY, CrowdTangle, and others. This pattern suggests a strategy of preventing competition rather than competing. If the appeals court sees this pattern, they might be more inclined to find antitrust violation.

Third, there's the data integration argument. Meta integrates WhatsApp and Instagram user data into its ad targeting system. This means Meta can track users across multiple platforms and services. This creates lock-in effects where users are unlikely to leave because Meta has comprehensive data on them across multiple services. This is anticompetitive foreclosure by integration, not just acquisition.

Fourth, there's the international precedent. The EU has been more aggressive in antitrust enforcement against Meta. In 2022, the Irish Data Protection Commission found that Meta was unlawfully combining user data across its services. The UK's Competition and Markets Authority has investigated Meta's acquisitions. If the appeals court looks at international precedent, there's a trend toward seeing Meta's behavior as anticompetitive.

So the FTC has genuine arguments. The question is whether they're strong enough to overcome Boasberg's findings.

What Happens If the FTC Wins on Appeal

If the FTC wins and the appeals court reverses Boasberg's ruling, the case goes back to the district court for further proceedings. This could mean a new trial or a remand for Boasberg to reconsider. If Boasberg ultimately rules for the FTC, the question becomes remedy.

The most dramatic remedy would be forced divestment. Meta would have to sell Instagram and/or WhatsApp to independent buyers or operate them as separate companies with separate governance. This would be unprecedented in modern tech. It would also be technically complex. How do you separate Instagram from Meta's ad infrastructure after 13 years of integration? Who buys Instagram? A private equity firm? Another tech company? What prevents that buyer from just buying WhatsApp too and creating the same structure?

A less dramatic remedy might be behavioral—ordering Meta to stop using data across its platforms for ad targeting, or preventing Meta from acquiring other social media companies in the future. But behavioral remedies are notoriously hard to enforce and often require ongoing regulatory oversight.

The most likely scenario if the FTC wins is that the case settles during appeal. Meta offers concessions—maybe they stop integrating WhatsApp data into ad targeting, or they divest GIPHY, or they agree not to acquire new social media companies for five years. The FTC claims victory, Meta pays a fine or agrees to behavioral changes, and the case closes without full divestment.

But if the case goes to trial and the FTC wins outright, divestment is definitely on the table. And that would reshape the tech industry dramatically.

What Happens If Meta Wins (More Likely)

If the appeals court affirms Boasberg's ruling and sides with Meta, antitrust law as it applies to platform acquisitions becomes very permissive. The message to tech companies is: as long as your market is competitive and consumers like your products, antitrust enforcement probably won't touch you even if you acquire potential competitors.

This has major implications. It means companies like Amazon could acquire more e-commerce competitors. Google could acquire more ad tech companies (beyond the current Fitbit and Waze deals). Microsoft could keep acquiring gaming companies. TikTok could acquire YouTube if it somehow had the capital (hypothetically).

For Meta specifically, a win means the company can pursue acquisitions without antitrust fear, as long as the market remains competitive. Meta's current strategy of acquiring companies like Giphy and CrowdTangle would be safe.

But there's a political element too. If Trump's administration is skeptical of antitrust enforcement generally, and if judges are increasingly business-friendly, a Meta win sets a precedent that would make future antitrust enforcement harder. The FTC could appeal to the Supreme Court, but Supreme Court justices have become skeptical of aggressive antitrust enforcement in recent years.

Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions are crucial to Meta, with Instagram contributing significantly to revenue and WhatsApp being strategically vital in emerging markets. (Estimated data)

The Bigger Picture: What This Case Means for Tech Regulation

This case is genuinely important because it will define how antitrust law applies to platform acquisitions for the next 10+ years.

There are two competing visions here. The first vision, represented by Boasberg and Meta, says antitrust law should focus on current competition and consumer outcomes. If the market is competitive today and consumers benefit, there's no violation. The second vision, represented by the FTC, says antitrust law should also focus on foreclosed competition and the process by which a company became dominant. If you bought out your competitors to prevent competition, that's a violation regardless of current market conditions.

These visions matter beyond just Meta. They affect how the entire tech industry will operate. Will companies feel free to acquire potential competitors? Or will they feel constrained by antitrust concerns? This affects innovation incentives, startup valuations, venture capital strategy, and the overall competitive dynamics of tech.

For consumers, it also matters. If Meta can acquire any competitor without fear, Meta becomes more powerful. If acquisitions are constrained by antitrust law, you get more independent competitors. Which scenario is better for consumers is genuinely debatable. Independent competitors might innovate differently and provide more choice. Or they might duplicate efforts and create a fragmented ecosystem. There are reasonable arguments on both sides.

What's clear is that this case will influence tech regulation in the Trump administration, through the appeals process, and potentially up to the Supreme Court.

The Political Game: Trump, Zuckerberg, and Judge Boasberg

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: politics.

Trump has a well-documented grudge against Meta. He claims the company was anti-Trump during his first term. In 2021, Meta banned Trump from Facebook and Instagram following January 6th. Trump sued. Meta defended the ban. The legal fight went back and forth.

Then, in early 2025, Meta apparently decided to make peace. Zuckerberg donated

Meanwhile, Judge Boasberg—who ruled for Meta—is facing political pressure from the Republican side. Brandon Gill, a Republican congressman, proposed impeachment articles against Boasberg, claiming he's a "rogue partisan judge" protecting conservatives. No action came of it, yet, but the threat hangs over the case.

This creates a perception, whether fair or not, that Boasberg might be swayed by political pressure. If you're a Republican or if you benefit from a Republican-friendly policy environment, you want judges to know that. Conversely, if you're a judge and you rule against Meta just weeks after Trump takes office and just months after Zuckerberg makes peace with Trump, it looks like you're inviting Republican retaliation.

The FTC, under Biden, pursued this case as part of an aggressive antitrust agenda. But Trump's antitrust policy is less clear-cut. Trump talks tough on Big Tech but has cozied up to tech billionaires. Trump's antitrust enforcement against Microsoft in the 1990s was famous, but his second term might be different.

So here's the political calculation: Boasberg ruled for Meta in November when the Biden administration was still in office and when antitrust enforcement was a priority. But now that Trump has taken office and Zuckerberg has made peace with Trump, the political climate has shifted. The FTC is appealing despite this shift.

Will that influence the appeals court? Probably not directly. Judges are supposed to be independent. But judges are also aware of the political environment and the consequences of their decisions. An appeals court that rules against Meta just weeks after Trump takes office and just months after Zuckerberg makes peace with Trump risks looking partisan.

This isn't to say the appeals court will rule for Meta because of political pressure. But it's a factor in the equation.

Meta's Integration Strategy and What It Says About Competition

Meta's approach to Instagram and WhatsApp reveals something important about how the company thinks about competition: Meta believes the way to compete is not through product differentiation or better features, but through integration and network effects.

When Meta acquired Instagram, the company didn't try to keep Instagram as a separate competitor. Instead, Meta integrated Instagram's technology into Facebook's infrastructure, combined the user bases for ad targeting purposes, and created a unified advertising platform. This gave advertisers more sophisticated tools to reach audiences across multiple Meta properties.

For consumers, this integration meant better ad targeting (you see ads you're more likely to click on), but it also meant less privacy (Meta knows your Instagram behavior, your Facebook behavior, and links them together for profile building).

The same happened with WhatsApp. WhatsApp was originally designed to be ad-free and privacy-first, with end-to-end encryption. But Meta gradually integrated WhatsApp data into Meta's ad targeting system. WhatsApp users can now be profiled and targeted with ads on Facebook and Instagram based on their WhatsApp usage patterns. This violates the original promise of WhatsApp's founders that the service would remain ad-free and privacy-focused.

This integration strategy reveals Meta's competitive philosophy: we don't win by offering a better product than competitors, we win by buying competitors and integrating them into a unified ecosystem where we control all the data. This is efficient for Meta and arguably beneficial for advertisers, but it's precisely the kind of conduct that antitrust law traditionally says is anticompetitive.

The appeals court will have to grapple with this. Is integration of acquired platforms illegal? Or is it just smart business? The answer depends on whether you think antitrust law should prevent companies from integrating data across platforms or whether it should focus only on consumer harm. This is the philosophical divide between Boasberg and the FTC.

Appeals in the US Court of Appeals typically take between 18 months to 3 years. This chart illustrates a projected timeline for completion. Estimated data.

What About the Future? Precedent and Implications

If Meta wins on appeal, the precedent is: platform acquisitions are generally fine as long as the market remains competitive. This would permit Amazon to acquire more e-commerce competitors, Google to acquire more search competitors, Microsoft to acquire more gaming competitors, and so on. It would be an antitrust loss for regulators and a win for big tech.

If the FTC wins, the precedent is: platform acquisitions can be anticompetitive if they foreclose competition, even if consumers currently benefit. This would constrain acquisitions and encourage more antitrust enforcement. It would be a win for regulators and potentially harder for big tech, but also potentially better for startup founders who could build companies without fear of being acquired by giants.

The Supreme Court doesn't typically take antitrust cases unless there's a circuit split or a major legal question. This case might end up at the Supreme Court eventually if the appeals court rules for the FTC. And given the Supreme Court's recent skepticism of aggressive antitrust enforcement, the odds of the FTC winning at that level are not great.

But we're a long way from the Supreme Court. First, the DC Circuit has to rule. That could take 18-24 months.

Real-World Consequences: How This Case Affects You

You might be wondering: how does this case affect me? I use Instagram. I use WhatsApp. Why should I care about Meta's antitrust case?

Here's why: the outcome determines whether Meta can keep consolidating power or whether it must operate its properties more independently.

If Meta wins and can keep integrating data across platforms, you should expect more targeted ads. Meta will know your behavior across Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook and use that knowledge to serve ads. You'll see ads that are increasingly tailored to your specific interests and behavior patterns. This is efficient for Meta but reduces your privacy.

If the FTC wins and forces some degree of separation, you'd have more privacy. Meta would be restricted in how much data it can combine across platforms. You might see less targeted ads, meaning you'd see ads less relevant to you. WhatsApp might actually remain more private and ad-free, as originally promised.

Also, the outcome affects your choices. If Meta wins and acquisitions are permitted, you'll have fewer independent alternative platforms. Meta would feel free to acquire any new social media app that becomes popular. If the FTC wins, startups that build new social platforms would be safer from acquisition, meaning more independent competitors and more choice for you.

Long-term, the precedent affects tech innovation. If Meta can acquire competitors without fear, other founders might be less willing to build social platforms, knowing Meta could just buy them out. If acquisitions are constrained, there might be more independent social platforms, more competition, and potentially better products.

So this case isn't just about Meta's legal fate. It's about the structure of the social media industry and what choices you'll have in the future.

The Timeline: When Will This Resolve?

The FTC announced its appeal in January 2025. Here's what the timeline probably looks like:

- January-March 2025: Briefing at the appeals court. Both sides submit written arguments.

- April-June 2025: Oral arguments before the DC Circuit Court of Appeals. Judges ask questions, both sides respond.

- Q3-Q4 2025 or early 2026: The appeals court issues a ruling. This could affirm Boasberg (Meta wins), reverse Boasberg (FTC wins), or remand for further proceedings.

- If the FTC wins: Meta likely appeals to the Supreme Court. Supreme Court decision whether to take the case comes in 2026.

- If Meta wins: The case is over unless the FTC petitions the Supreme Court (unlikely if they lost at the appeals level).

So realistically, we probably have an appeals court ruling sometime in late 2025 or early 2026. A Supreme Court decision, if it reaches there, would come in 2027 or later.

This is a long process. In the meantime, Meta continues to operate normally, and the FTC continues to pursue other antitrust cases against Amazon, Apple, and Google.

Comparing This Case to Apple and Google Antitrust Cases

Meta's case isn't happening in isolation. The FTC and DOJ have also pursued antitrust cases against Apple and Google. Understanding those cases helps contextualize Meta.

The Apple case focuses on whether Apple's control over the iPhone App Store violates antitrust law. The core question: does Apple have monopoly power in smartphone apps? Does it abuse that power by charging 30% commission and preventing users from sideloading apps? This case is still ongoing, with a federal judge ruling partially in favor of the FTC but upholding most of Apple's practices.

The Google case focuses on whether Google has a monopoly in search and whether Google's exclusive deals with Apple, Mozilla, and others foreclose competition. The DOJ won at trial in 2024, with the judge finding that Google does maintain an illegal monopoly in search through anticompetitive practices. But Google is appealing and likely has a decent shot at overturning the ruling.

Meta's case is different from both. It's not about market power in a current market (like Apple's App Store or Google's search). It's about whether past acquisitions were anticompetitive. This makes it harder to prosecute because you're arguing about historical competitive harm rather than current consumer harm.

The pattern across all three cases is that the FTC/DOJ are pursuing big tech aggressively, but judges are skeptical of structural remedies and focused on consumer harm. This suggests the appeals court might also be skeptical of the FTC's Meta case.

The Bigger Regulatory Picture

Meta's case happens in a context of broader regulatory scrutiny of tech companies. The EU is pursuing antitrust cases against Meta and Google. The UK is investigating platform mergers and acquisitions. The FTC is pursuing cases against Amazon, Apple, and Google as well. There's a global trend toward tighter tech regulation.

However, there's also a counter-trend with Trump's election. Trump has been skeptical of aggressive antitrust enforcement and skeptical of the FTC and its leadership. Trump's DOJ might pursue different priorities than Biden's DOJ. This creates uncertainty about whether the FTC's case against Meta will remain a priority or whether the agency will shift focus.

The appeals court will likely look at the broader regulatory environment when deciding this case. If the trend is toward less aggressive enforcement, judges might be reluctant to order a major structural remedy like forced divestment. If the trend is toward more enforcement, judges might be more willing to support the FTC.

FAQ

What exactly is the FTC alleging against Meta?

The FTC alleges that Meta maintained an illegal monopoly in "personal social networking services" by acquiring Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014. The agency argues that Meta identified these companies as potential competitors and bought them to eliminate competition rather than compete with them on the merits. The FTC sought to force Meta to divest these platforms as a remedy.

Why did Judge Boasberg rule in Meta's favor?

Boasberg ruled that the FTC failed to prove Meta had a monopoly in the relevant market. Specifically, the judge found that the market for social networking includes TikTok as a major competitor, not just Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat. By including TikTok in the market definition, Meta's market share is much smaller, and the monopoly allegation falls apart. Additionally, Boasberg found that Instagram and Facebook have improved significantly since the acquisitions, suggesting consumers haven't been harmed.

How does the appeals process work in this case?

The appeals court reviews whether Judge Boasberg applied antitrust law correctly. It doesn't retry the case or hear new evidence. The FTC must convince the appellate judges that Boasberg made an error in law or in his factual findings. If the appeals court agrees with Boasberg, Meta wins and the case is over (unless it goes to the Supreme Court). If the appeals court sides with the FTC, the case goes back to the lower court for further proceedings or a new trial.

What's the market definition and why does it matter?

Market definition is crucial in antitrust law because it determines whether a company is dominant. If the market is defined narrowly as "personal social networking" (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat), Meta looks dominant. If the market is defined broadly as "social media" (including TikTok, YouTube, Snapchat, Discord, etc.), Meta is one of several major competitors. The FTC argued for the narrow definition; Boasberg agreed with Meta's broader definition. The appeals court will likely focus on this question.

Could Meta be forced to divest Instagram or WhatsApp?

Yes, if the FTC wins on appeal and the case ultimately goes against Meta, forced divestment is possible. This would mean Meta would have to sell Instagram and/or WhatsApp to another company or operate them as independent entities. This would be unprecedented in modern tech and would require Meta to unwind 13 years of integration, which is technically complex. More likely is a settlement with behavioral concessions or partial divestment.

How does this case affect consumers?

If Meta wins, consumers should expect more targeted advertising across Meta's platforms because Meta can continue integrating data across Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook. If the FTC wins, consumers might get more privacy restrictions on Meta's data integration. Additionally, if the FTC wins, startups building new social platforms might be safer from acquisition, leading to more competition and consumer choice.

What's the political context of this case?

Trump has had a contentious relationship with Meta and Zuckerberg. Trump was frustrated with Facebook's fact-checking, and Meta banned Trump from its platforms after January 6th, 2021. Since Trump took office in 2025, Zuckerberg has attempted to repair the relationship by donating to Trump's inauguration and settling lawsuits. This political context may influence judicial decision-making, though judges are supposed to be independent. The appeals court is aware of this political environment and may be cautious about appearing partisan.

When will this case be resolved?

The appeals process typically takes 18-24 months. An appeals court ruling is likely in late 2025 or early 2026. If the FTC loses at the appeals level, the case is likely over. If the FTC wins, Meta will probably appeal to the Supreme Court, which would take another 2+ years. So a final resolution could take 3-4 years total from now.

Is this case similar to previous antitrust cases?

The FTC has pursued similar acquisition-based antitrust cases, but this is different from current cases against Apple (App Store monopoly) and Google (search monopoly). Meta's case is backward-looking, focusing on whether past acquisitions were anticompetitive. This makes it harder to prosecute than current consumer harm cases. Historically, courts have been skeptical of arguments that past acquisitions should be undone if current market conditions are competitive.

What would the ruling mean for other tech companies?

If Meta wins, it sets a precedent that platform acquisitions are generally acceptable as long as the market remains competitive. This would permit Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and others to pursue acquisitions more aggressively. If the FTC wins, it establishes that acquisitions can be anticompetitive even if consumers benefit, constraining tech company acquisition strategies and potentially spurring more antitrust enforcement.

Could Meta settle this case?

Yes, settlement is possible and perhaps likely. Meta might offer concessions like restricting data integration across platforms, agreeing not to pursue certain acquisitions in the future, paying a fine, or divesting certain properties like GIPHY or CrowdTangle. Settlements often occur during the appeals process when both sides recognize the risks of continuing litigation.

The Bottom Line

The FTC's appeal of Meta's monopoly case is fundamentally a question about what antitrust law should do: focus on current market competition and consumer outcomes, or also prevent companies from buying out competitors to foreclose future competition?

Judge Boasberg sided with the first view—current conditions matter most, and by that measure, Meta isn't a monopoly because TikTok competes fiercely. The FTC represents the second view—the process by which Meta became dominant matters, and acquiring Instagram to prevent competition was anticompetitive regardless of current outcomes.

The appeals court will eventually have to choose between these visions, and that choice will define antitrust law's application to platform acquisitions for a decade or more.

Meanwhile, the political context is undeniable. Zuckerberg has made peace with Trump, Meta's lawyer has kept the tone diplomatic, and Judge Boasberg faces political pressure from Republicans. The appeals court will make its decision in this environment, aware that tech regulation is a politically charged issue.

The most likely outcome? Meta wins on appeal, the precedent becomes permissive toward tech acquisitions, and antitrust enforcement shifts toward different targets. But if judges decide that foreclosing future competition is genuinely anticompetitive regardless of current market conditions, the FTC has a real shot.

We'll know more when oral arguments happen in spring 2025 and when the DC Circuit issues its ruling later in the year. Until then, this case will remain one of the most important regulatory battles in tech, with implications far beyond Meta.

Key Takeaways

- The FTC is appealing a November 2024 ruling that cleared Meta of monopoly charges, arguing Meta's Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions illegally foreclosed competition

- Judge Boasberg ruled against the FTC primarily because TikTok is a major competitor to Instagram, making Meta's market share not dominant when the market is defined broadly

- The core legal question is whether antitrust law should focus on current market competition or also prevent acquisitions that foreclose future competition opportunities

- Political tensions are real: Zuckerberg recently made peace with Trump, Judge Boasberg faces Republican impeachment threats, and the regulatory environment has shifted

- If the FTC wins on appeal, Meta could be forced to divest Instagram or WhatsApp; if Meta wins, it sets a permissive precedent for tech acquisitions that will last 10+ years

Related Articles

- FTC Appeals Meta Antitrust Ruling: What It Means for Big Tech [2025]

- FTC's Meta Antitrust Appeal: What's at Stake in 2025

- Meta's Illegal Gambling Ad Problem: What the UK Watchdog Found [2025]

- WeatherTech Founder David MacNeil as FTC Commissioner [2025]

- X's Algorithm Open Source Move: What Really Changed [2025]

- Trump Mobile FTC Investigation: False Advertising Claims & Political Pressure [2025]

![FTC Meta Monopoly Appeal: What's Really at Stake [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ftc-meta-monopoly-appeal-what-s-really-at-stake-2025/image-1-1768952365673.jpg)