Introduction: The Promise of Computing Beyond Earth

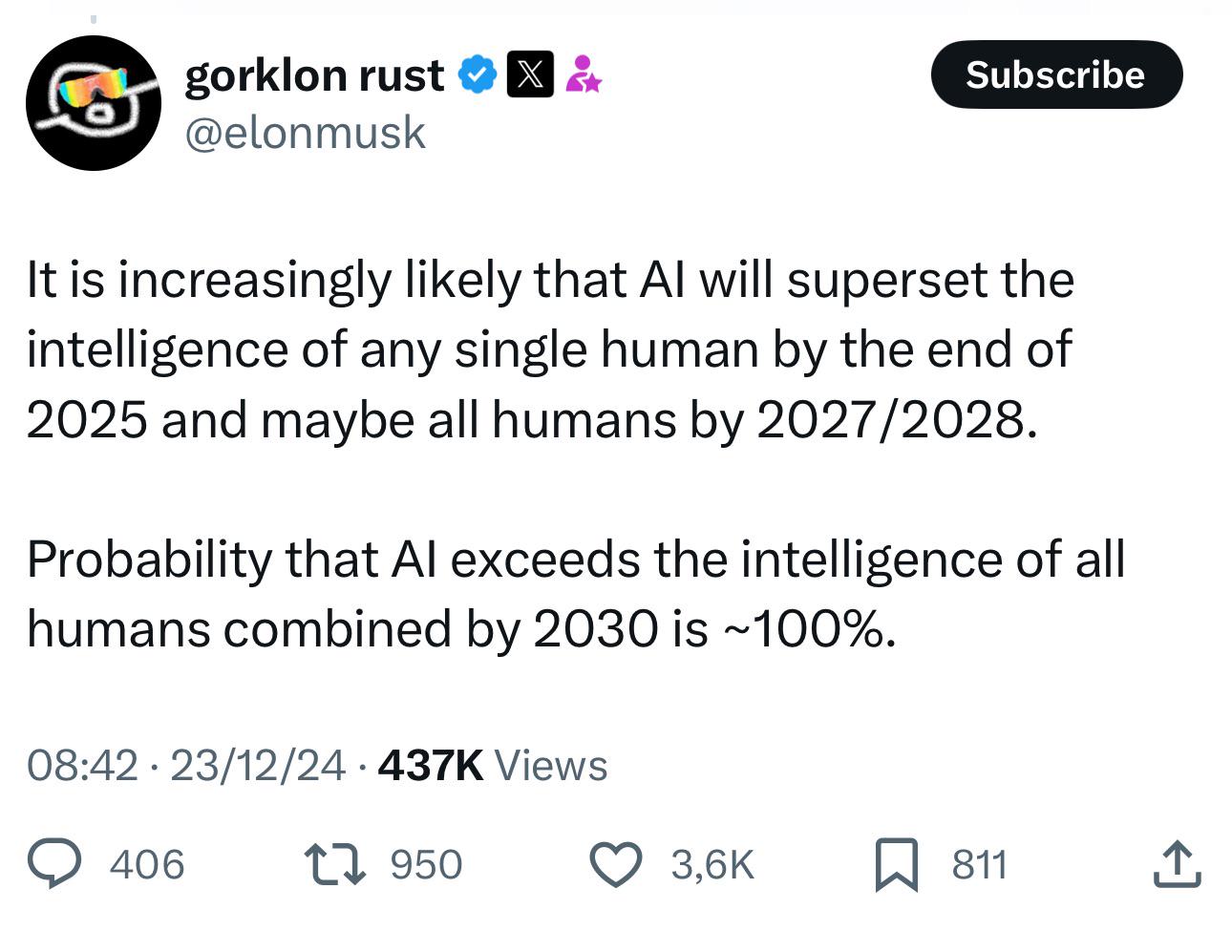

Elon Musk has always had a talent for making the impossible sound inevitable. Whether it's electric vehicles replacing combustion engines, reusable rockets, or neural implants connected to your brain, he frames technical challenges as mere obstacles on the path to greatness. His latest proclamation fits perfectly into this pattern: within three years, he claims, the cheapest way to generate artificial intelligence compute will be in space.

It's a bold statement. Too bold.

The idea itself isn't completely ridiculous. Space has unique advantages. Satellites orbiting Earth experience 24-hour sunlight in certain configurations. They're not bound by terrestrial power grids or cooling infrastructure limitations. Data transmission happens at the speed of light, unobstructed by terrestrial geographic constraints. These factors have genuine appeal for compute-heavy workloads.

But there's a problem with the three-year timeline, and it's not a minor one. It's the kind of problem that separates visionary thinking from engineering reality. This article breaks down why Musk's orbital AI compute prediction is more science fiction than strategy, what would actually need to happen to make it work, and what the real trajectory for space-based computing looks like.

The stakes matter here. If you're making infrastructure investments, betting on business models, or funding startups in the AI space, understanding the actual timeline versus the hype matters tremendously. This isn't about dismissing ambitious thinking. It's about being honest about what engineering timelines actually look like when you're working at the frontiers of multiple technologies simultaneously.

The Current State of AI Compute Economics

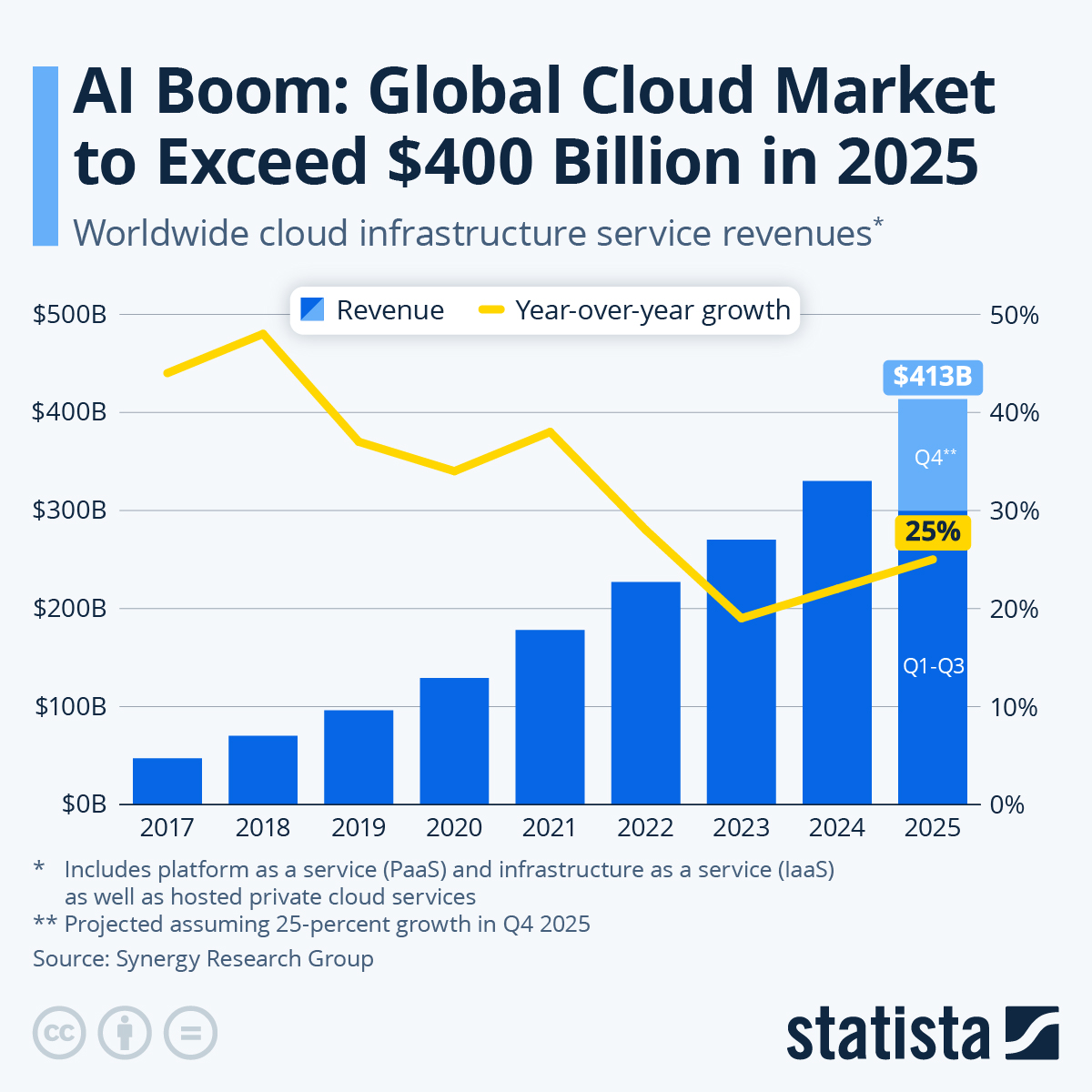

Let's establish baseline reality. Right now, AI training and inference happen almost exclusively on Earth. NVIDIA's H100 and next-generation chips dominate this space. Data centers run them in massive clusters, cooled by elaborate systems, powered by reliable electrical grids, and connected to fiber optic networks.

The economics are brutal. A single H100 costs around

Cost per compute hasn't followed a clean downward trajectory. Yes, chips get better. But data center buildout costs, power infrastructure, cooling systems, and real estate all create a complex economic landscape. The marginal cost per FLOP (floating-point operation) has improved, but we're hitting limits. Efficiency gains are getting smaller.

Space doesn't currently compete with this. Not remotely.

Why Space Computing Seems Attractive in Theory

Let's understand why this idea keeps appearing in conversations about the future of computing. The theoretical advantages are real. They're just heavily outweighed by practical disadvantages that people often overlook.

First, solar power availability. A satellite in geostationary orbit or in certain polar configurations gets sunlight 24/7 (or nearly so). Terrestrial data centers depend on grid power, which requires fuel sources. If solar could reliably power massive compute clusters in space, eliminating terrestrial electricity costs would be huge.

Second, thermal rejection. CPUs generate heat. Lots of it. A single data center can consume as much power as a small city. Dissipating that heat on Earth requires cooling systems using water, air, or specialized refrigeration. Space has nearly infinite heat sink. Radiate it to the vacuum surrounding your satellite, problem solved.

Third, escape from geographical constraints. You can't build a data center everywhere on Earth. Cities have zoning regulations, noise ordinances, power infrastructure limitations. You can't put a data center in the middle of the Sahara, even though it's hot and has tons of sun, because there's no power infrastructure or fiber optic connectivity. Space removes these constraints entirely.

Fourth, physical inevitability of expansion. Earth has finite land. Eventually, if you want to scale compute globally, you might run out of good locations. Space is literally infinite. This is a long-term argument, but it's real.

These aren't stupid arguments. They're why researchers and companies keep exploring space-based computing despite the obvious challenges.

The Engineering Reality: Why Three Years is Fantasy

Now let's get honest about the distance between "theoretically possible" and "actually deployable and economically competitive."

Musk's three-year timeline requires solving multiple simultaneous engineering problems. Not sequentially. Simultaneously. Each one is substantial on its own.

The Launch Cost Problem

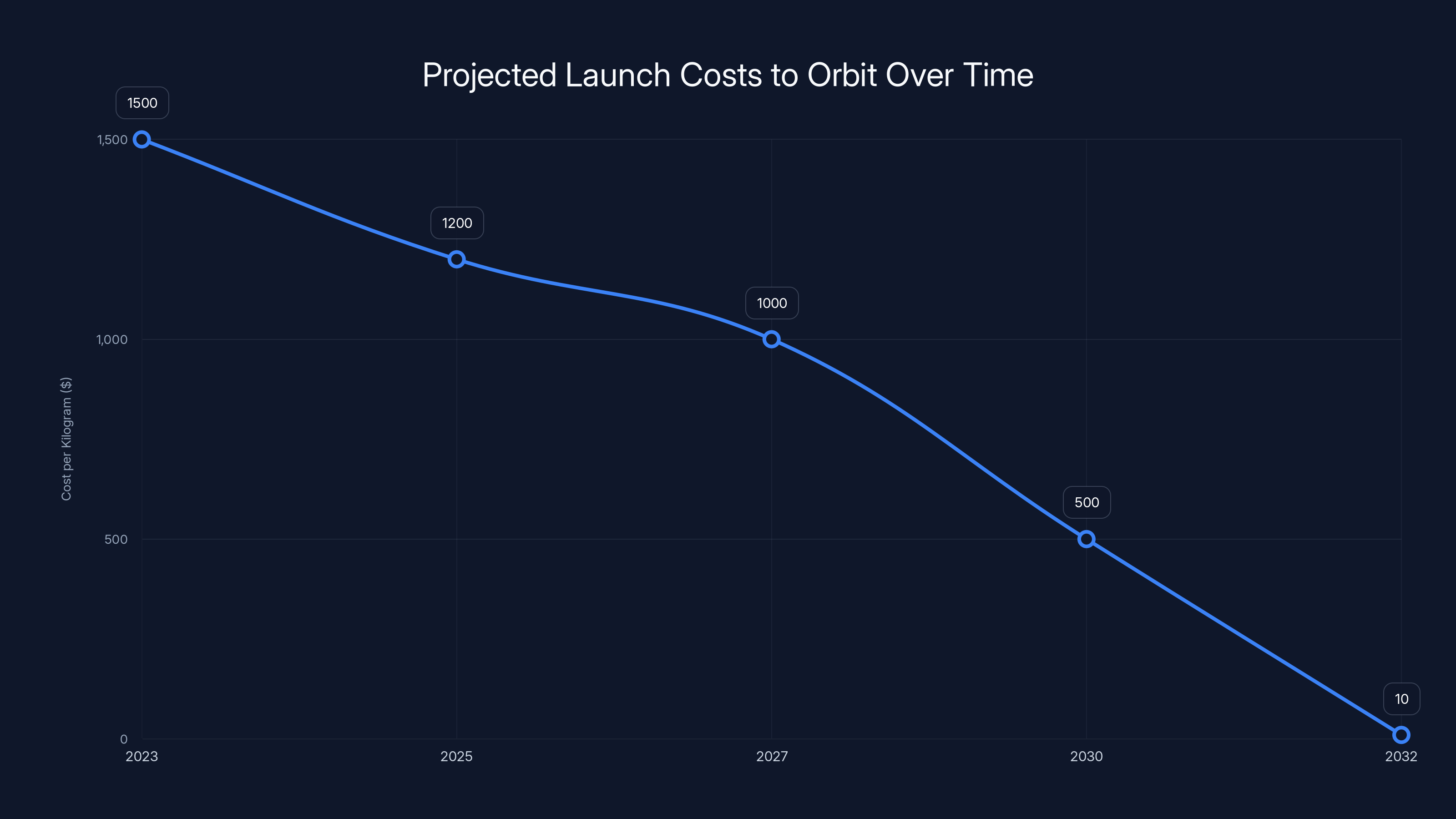

First, you need to get massive hardware to orbit. Space X has made tremendous progress on reducing launch costs. Starship aims to reach perhaps

A single data center rack containing 8-10 H100s weighs roughly 400-500 kilograms. Cooling systems, power distribution, structural support, and other infrastructure add mass. You're looking at a metric ton minimum per rack of serious compute.

At

But here's where it gets worse. Launch costs at $10/kg are aspirational. They assume Starship reaches full operational capability and flies frequently. This isn't happening by 2027. Most estimates from knowledgeable observers put routine, cheap Starship flights several years beyond that. Maybe 2028-2030 at absolute earliest. More realistically, 2032+.

Even if Starship hits $10/kg tomorrow, you still face a problem. Every kilogram has to be launched. A data center on Earth has significant infrastructure costs, but once you've built the building, you don't launch it again. With space infrastructure, continuous refresh cycles, replacement parts, and new capacity all require launches.

The Thermal Rejection Problem

Let's talk about the cooling system that supposedly solves the heat problem.

Radiative cooling works. Physics supports it. A hot object in space radiates heat energy directly into the vacuum. The Stefan-Boltzmann law governs this. The power radiated is proportional to the surface area and the fourth power of the absolute temperature.

Where epsilon is emissivity (how good the material is at radiating), sigma is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, A is surface area, and T is absolute temperature.

The problem is scale. An H100 generates 700 watts. To reject that via radiation alone, you need a radiator surface at a particular temperature. For a typical spacecraft radiator (not special high-performance versions), you're looking at several square meters of radiator per kilowatt of heat.

That means dozens of square meters of radiator per modest compute cluster. Radiators don't just sit around. They need structure. They're exposed to solar input, which complicates the thermal balance. They can fail. When they fail, your system overheats and shuts down. You can't service them without sending a repair crew to space.

Earth-based data centers solve this with water cooling loops, chillers, and backup systems. This is proven, relatively cheap, and easily serviceable. Space-based thermal systems are cutting-edge aerospace engineering problems that require testing, validation, redundancy, and continuous monitoring.

This isn't unsolvable. But it is complex. And it definitely isn't solved by 2027.

The Network Latency Problem

Here's something people don't think about enough. Orbital data center latency from space to ground is governed by the speed of light.

Geosynchronous orbit (where you want to be for continuous coverage) is about 36,000 kilometers away. The speed of light in fiber is roughly 200,000 kilometers per second. That's 180 milliseconds of latency just from the physical distance. Add ground infrastructure, routing, and protocol overhead, and you're looking at 250+ milliseconds of round-trip latency.

For most AI inference tasks, that's acceptable. For some training workflows, it's manageable. But it's not zero. And unlike Earth-based data centers where you can be in the same building as your infrastructure, you have a fundamental physical limit.

Lower Earth orbit fixes this partially. LEO satellites are 400-2,000 kilometers up. That's 2-20 milliseconds of latency. But LEO satellites move. Fast. They circle Earth every 90 minutes. Your data center isn't stationary. You need a constellation of them to maintain continuous coverage.

A constellation might mean 50-100 satellites. Each needs to be independently operational. Launch costs multiply. Coordination becomes a software engineering nightmare.

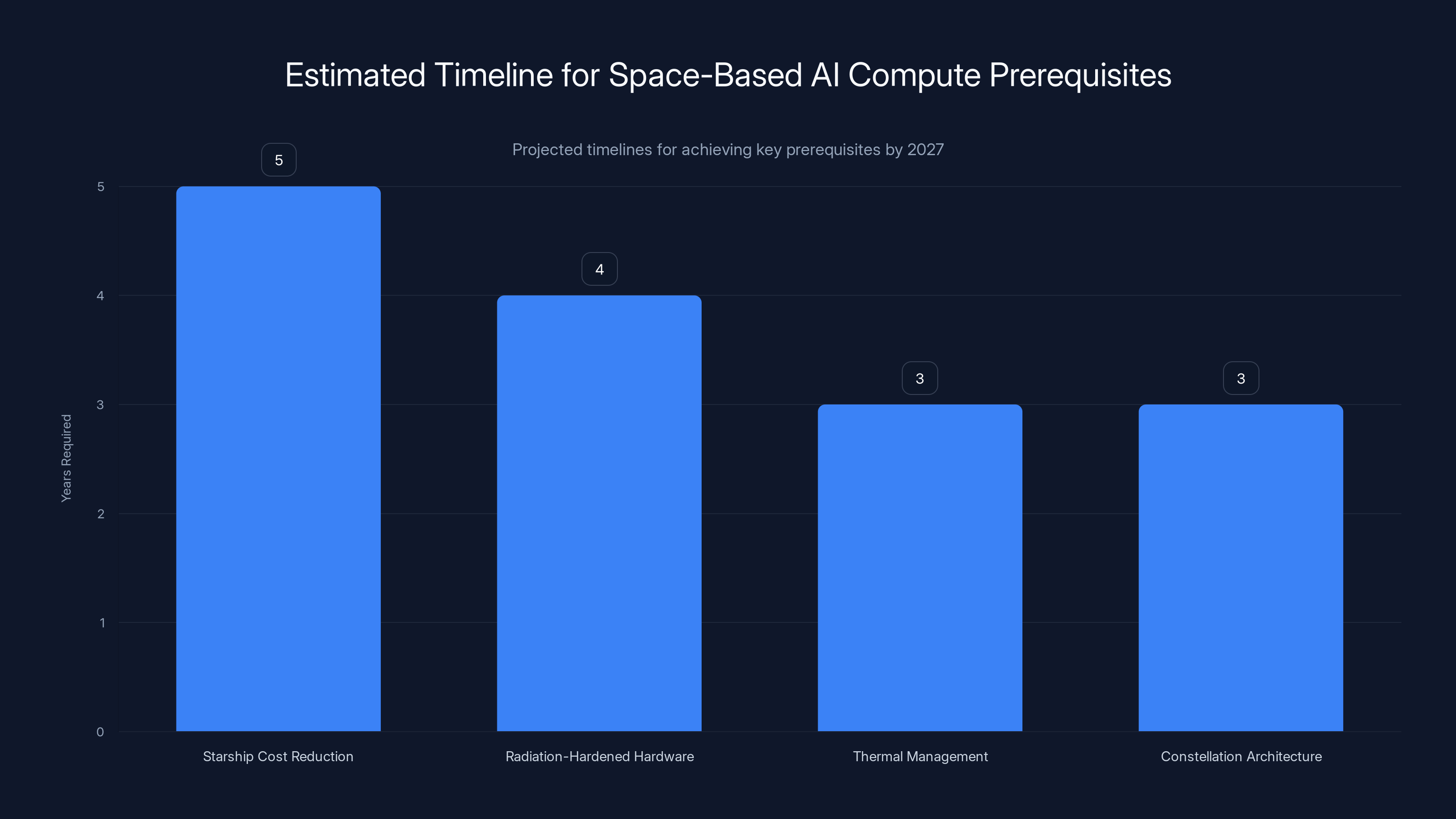

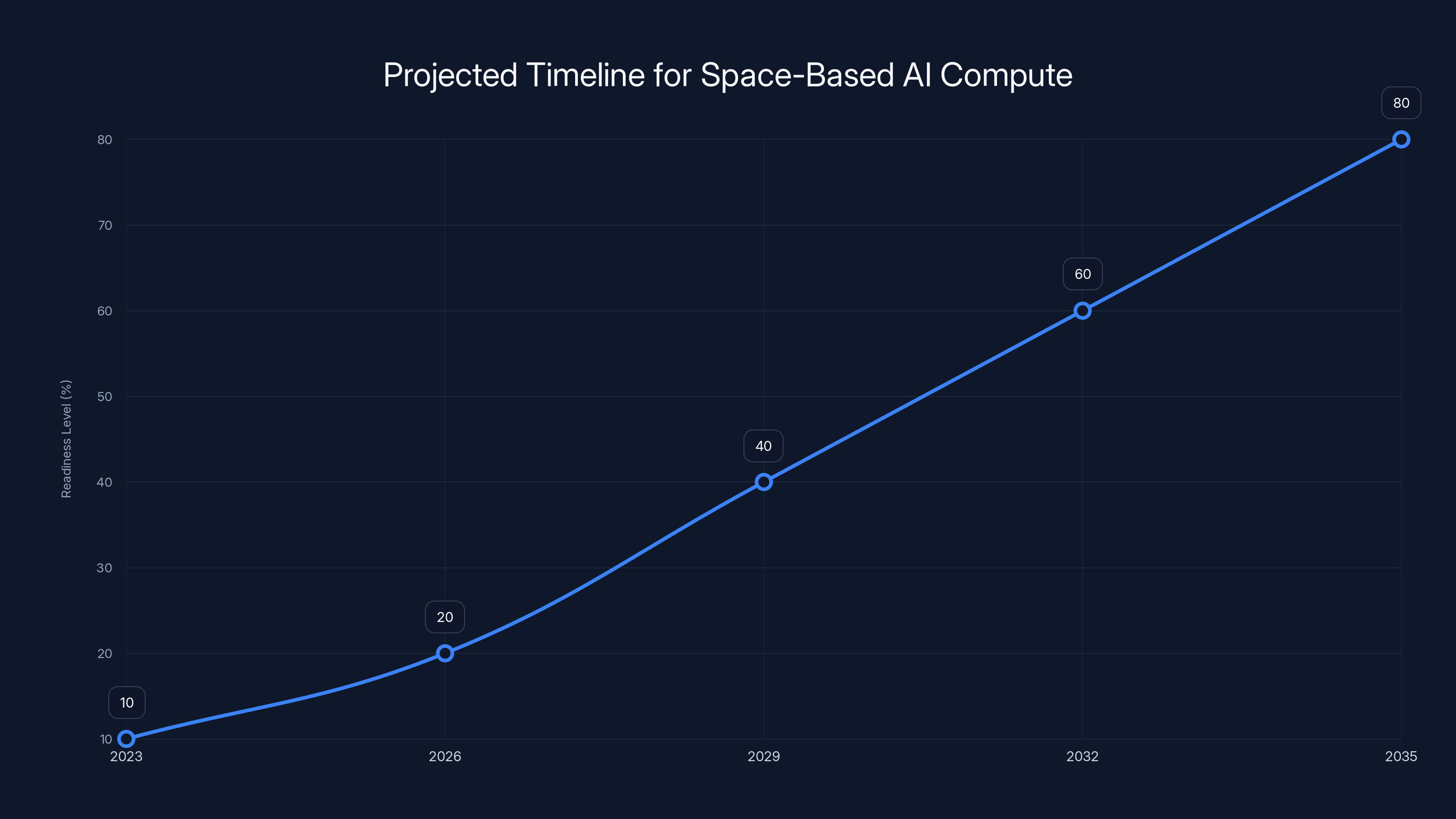

Estimated data suggests that achieving all prerequisites for space-based AI compute by 2027 is challenging, with timelines extending into 2028-2030.

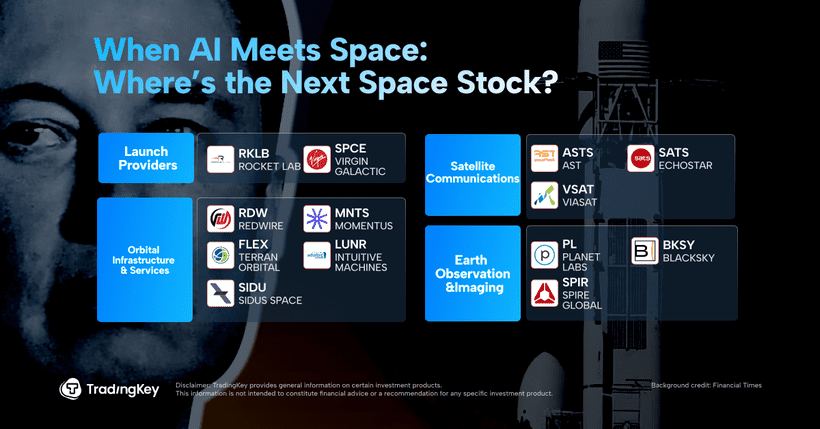

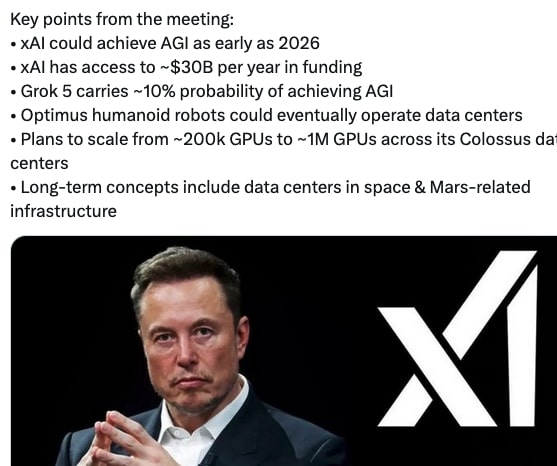

Space X's x AI Acquisition: Strategic or Opportunistic?

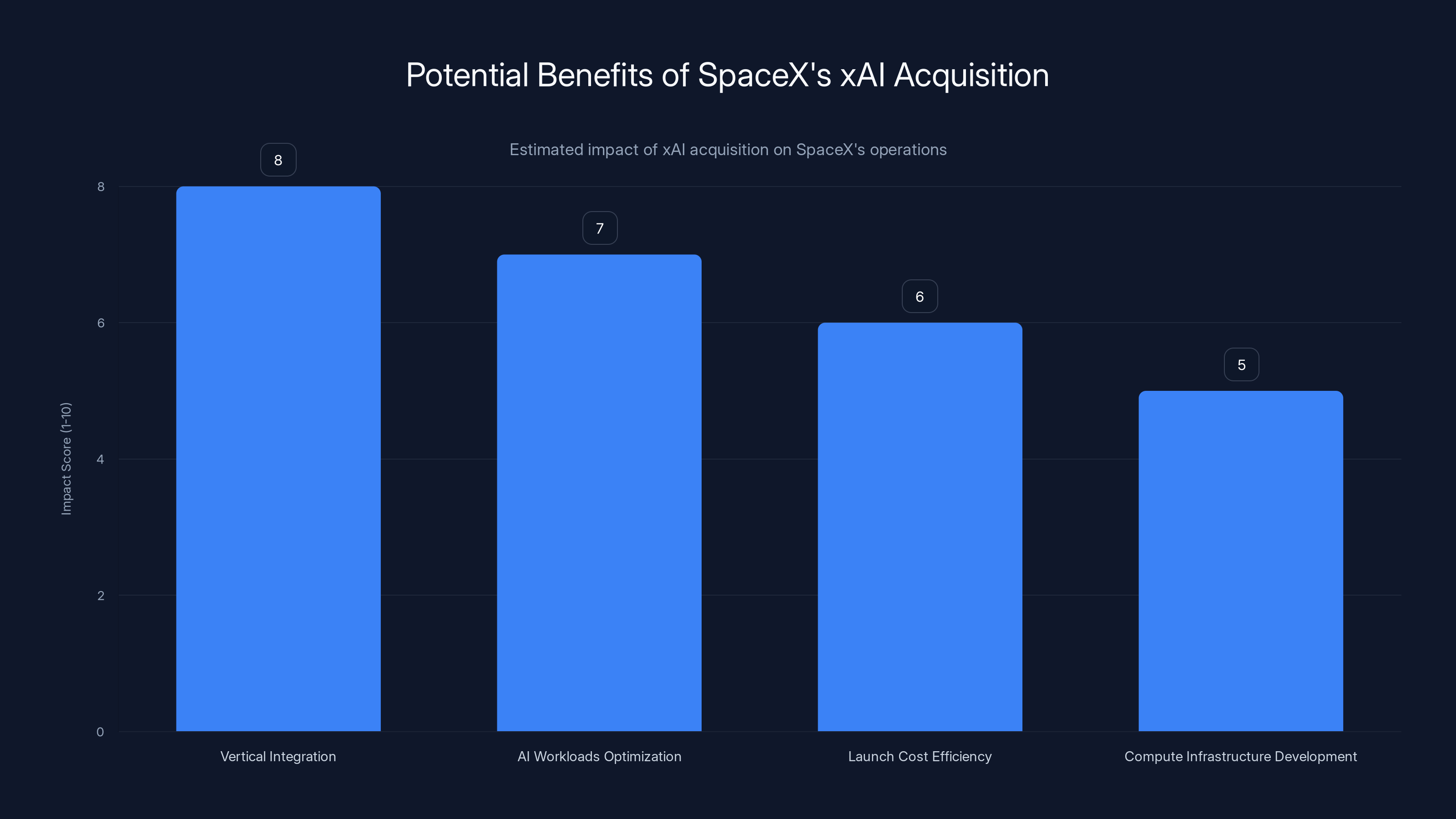

In late 2024, Space X acquired a portion of x AI, the AI company founded by Musk. This isn't a surprise. Musk controls both companies (plus Tesla, Neuralink, and others). The move does signal something: Space X is taking AI seriously as a potential revenue stream.

But it doesn't change the engineering timeline. Acquiring an AI company doesn't accelerate Space X's ability to deploy space-based compute infrastructure. It gives them better internal demand, sure. But demand doesn't solve physics problems.

What the acquisition does suggest is that Musk is thinking about vertical integration. Space X provides launches. x AI provides AI workloads. Theoretically, they could optimize the entire pipeline: launch costs structured for x AI's specific needs, compute architecture customized for available power and thermal conditions, data flow optimized for orbital architecture.

That's smart business thinking. It doesn't make the timeline realistic.

The Integration Challenge

Building a custom AI infrastructure in space requires unprecedented collaboration between aerospace engineering and machine learning engineering. These are different disciplines with different timescales.

Aerospace projects have multi-year qualification and testing phases. Machine learning projects iterate weekly. Getting these to align isn't impossible, but it's genuinely hard. It requires organizational structures and decision-making processes that don't naturally emerge from either domain.

Space X has demonstrated exceptional execution capability on rockets. But building satellites is different. Building compute satellites is different still. And operating compute infrastructure in space isn't Space X's core competency. It's a new domain for them.

That's not a criticism. It's just reality. Executing in a new domain takes time, even for exceptionally capable organizations.

Musk's Track Record on Timelines

Let's look at actual precedent. How accurate has Musk been with three-year predictions?

- Tesla's Full Self-Driving: Promised as functionally complete by 2019. Still in supervised beta in 2025.

- Starship orbital flight: Predicted for 2020. Happened in 2023.

- Mars landing: Original timeline was 2025. Current best estimates are late 2020s, possibly 2030s.

- Neuralink human trials: Predicted for 2019. First patient implanted in 2024.

The pattern is consistent. Bold predictions. Real progress. But timelines slip by years, not months.

This isn't because Musk is lying or unintelligent. It's because extreme engineering challenges are hard to predict. Unforeseen problems emerge. Regulatory requirements surprise you. Integration issues take longer than expected. What sounds feasible from high-level thinking encounters reality.

Estimated data shows a significant decrease in launch costs per kilogram to orbit, potentially reaching $10/kg by 2032. This assumes technological advancements and increased flight frequency.

What Would Actually Need to Happen

Let's outline the prerequisites for space-based AI compute to actually be cheaper than Earth-based by 2027. This is useful because it shows just how unrealistic the timeline is.

Prerequisites for Success

One: Starship reaching $10/kg to orbit reliably and frequently

Right now, Starship is still in development. It can reach orbit intermittently. Achieving reliable, frequent flights with payload costs that low would require:

- Solving remaining technical issues with reusability

- Establishing ground infrastructure at multiple launch sites

- Obtaining regulatory approval for frequent launches

- Proving out in-space refueling capability

- Training and scaling launch operations teams

Experts estimate this needs 3-5 years minimum. So 2028-2030 as a realistic target.

Two: Developing radiation-hardened compute hardware specialized for space

H100s aren't designed for space. Space has radiation. Radiation corrupts data. You need error correction, redundancy, and rad-hardened components. This isn't impossible, but it requires custom chip design. NVIDIA or custom semiconductor designers need to build this. And they need to do it while keeping costs competitive with Earth-based chips.

This is a 2-4 year project independent of everything else.

Three: Solving thermal management at scale

Radiator design, testing, and validation takes time. You need multiple redundant cooling loops. You need to test them under actual space conditions. Thermal modeling needs validation. Contingency systems for radiator failure need development.

Minimum 2-3 years for this domain.

Four: Building a constellation architecture

You can't run AI compute on a single satellite. You need high availability, redundancy, and fault tolerance. This means designing a constellation, planning deployment schedules, and building ground station networks.

2-3 years for this.

Five: Regulatory approval

Launching dozens of heavy satellites raises orbital debris concerns. Collision risk increases. The FCC and international bodies need to approve this. There will be environmental reviews. This is a 1-2 year process separate from everything else.

Six: Making it economically competitive

Even if all the above happens, you need to undercut Earth-based data centers. That means beating $1 per hour for H100-equivalent compute. Your launch costs, satellite costs, operations costs, and overhead need to total less than this.

Given the infrastructure investments required, this is extremely challenging even if everything else works.

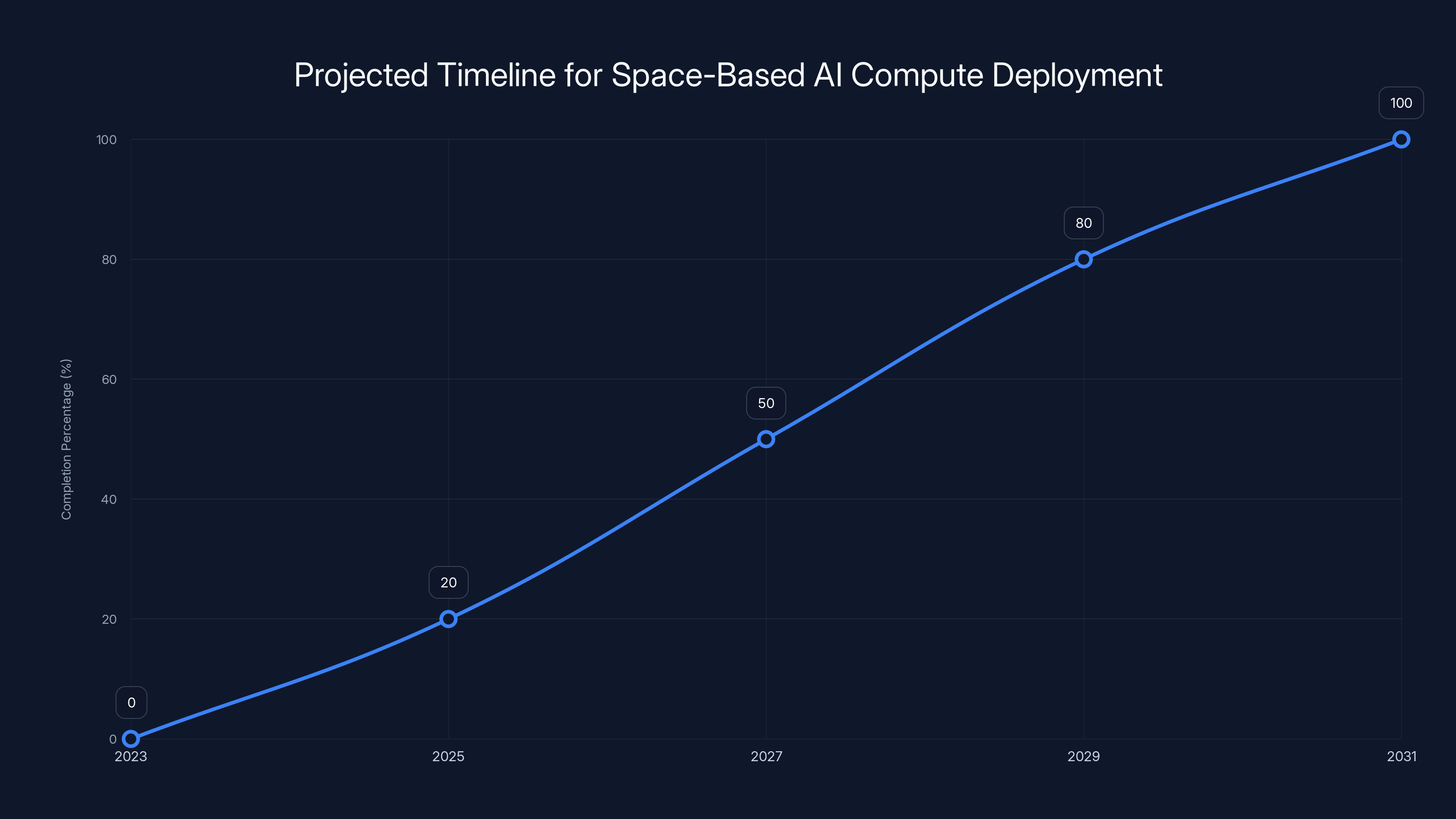

Total Timeline Estimate

These can't happen perfectly in parallel. Some depend on others. A realistic estimate, being optimistic:

- Starship readiness: 2029-2031

- Custom hardware: 2027-2028

- Thermal solutions: 2027-2029

- Constellation architecture: 2026-2028

- Regulatory approval: 2028-2030

- First operational revenue-generating constellation: 2031-2034

- Achieving price competitiveness: 2033-2037

That's roughly a decade from now. Not three years.

The Business Case Problem

Beyond engineering, there's a business problem. Why would customers use space-based AI compute if it costs more?

Initial adopters might accept premium pricing for novel capabilities. Maybe some defense contractors want computation that's literally unhackable from ground-based threats. Maybe some applications really do benefit from continuous 24-hour solar power. These are niche markets.

But mainstream AI compute? Training large language models? Running inference at scale? These customers buy based on price and performance. If space-based compute is more expensive, they don't use it, no matter how cool the technology is.

Musk's claim that it'll be the cheapest way assumes massive volume and mature operations. But volume doesn't build on Day One. You need a decade of operations to work out problems, optimize costs, and achieve scale. And during that decade, Earth-based compute keeps improving.

Moore's Law is slowing, but it's not dead. Custom silicon for AI inference is exploding. Data center efficiency increases continue. By the time space-based compute reaches price parity, Earth-based infrastructure will have improved substantially.

It's a moving target. The math is harder than Musk's three-year statement suggests.

The projected timeline suggests that significant milestones towards space-based AI compute deployment might be achieved by 2029, with full operational capability potentially by 2031. Estimated data based on technical challenges.

Alternative Approaches That Are More Realistic

If you're actually interested in solving the computational power problem, there are more tractable approaches.

Improving Earth-Based Infrastructure

We can still squeeze enormous efficiency gains from terrestrial data centers. Better cooling approaches (immersion cooling, free cooling), optimized chip design, and architectural innovations could reduce costs by 30-50% over the next five years.

This is harder than it sounds, but it's well-understood engineering. The path is clear.

Distributed Compute Networks

Instead of centralized data centers, distribute compute across edge locations. This reduces data transmission costs and latency. It's not as efficient as massive centralization, but it's practical and deployable today.

Power-Aware Algorithm Design

Make AI models smaller, more efficient, and less power-hungry. Techniques like quantization, knowledge distillation, and sparse models are advancing. An efficient model running on cheap hardware might beat an inefficient model on expensive hardware.

These approaches are boring compared to space satellites. But they're practical, testable, and improvable within a three-year timeframe.

The Role of Government and Regulation

Space infrastructure requires government buy-in. The FCC licenses spectrum. The FAA approves launches. The State Department manages international agreements. NORAD tracks objects. Environmental impact assessments happen.

Musk sometimes operates as if these constraints don't exist. But they do. Building a major space infrastructure without government approval is impossible. And government timelines are longer than startup timelines.

There's also the question of international coordination. Orbital slots are managed by the International Telecommunication Union. Launch sites are limited. Frequency spectrum is shared. China, India, and other nations are launching satellites too. The orbital environment is getting crowded.

This isn't a blocker. But it adds complexity that individual companies can't control.

The acquisition of xAI by SpaceX is estimated to have the highest impact on vertical integration, with significant benefits also expected in AI workload optimization and launch cost efficiency. Estimated data.

What Success Actually Looks Like

If space-based AI compute becomes real, it probably looks nothing like Musk's vision. Here's a more realistic scenario:

Around 2035-2040, Space X or another company operates a constellation of compute satellites. They're used for specific applications where orbital advantages matter:

- Defense applications where ground-based networks aren't trustworthy

- Scientific research that needs low-latency orbital position data

- Remote operations where terrestrial connectivity doesn't exist

- Specialized workloads where continuous solar power provides unique benefits

The cost is premium compared to Earth-based infrastructure. Margins are thin. Operations are challenging. But it works, and for specific customers, it provides value.

Maybe, over decades, costs come down enough to compete with terrestrial infrastructure for commodity workloads. Maybe. But that's a generational bet, not a three-year timeline.

This doesn't sound as visionary as Musk's statement. It's also vastly more likely to happen.

Lessons for Evaluating Technological Predictions

This entire discussion is really about how to evaluate claims about transformative technology. Musk is far from alone in making bold predictions. Venture capitalists do it constantly. Technical founders do it. Analysts do it.

How do you separate signal from noise?

First, check the precedent. What has this person or organization predicted before? How accurate were they? Did they revise timelines realistically? This is the strongest indicator of future accuracy.

Second, break down the claim into components. The orbital compute claim breaks into launch costs, thermal management, hardware, constellation design, regulations, and economics. Most predictions fail because one component takes longer than expected. Breaking it down reveals which components are realistic and which are optimistic.

Third, talk to domain experts. Not to the entrepreneur, but to independent engineers in relevant fields. What do they think is realistic? What unknowns concern them? Experts are usually more pessimistic than enthusiasts, but that pessimism is earned through experience.

Fourth, look at historical timelines for similar ventures. Building large infrastructure (satellites, data centers, networks) has consistent timescales. Massive innovation might shave 20-30% off estimates. It doesn't shave 70-80%.

Fifth, distinguish between "technically possible" and "economically viable. These are different questions. Something can be technically possible and still not make economic sense. Most space ventures fail not because the technology is impossible, but because economics don't work.

Estimated data suggests that while space-based AI compute has potential, reaching full operational capability could take over a decade, not just three years.

Why This Matters Right Now

You might be wondering why this matters. Musk makes bold predictions all the time. Why care about this one specifically?

Because AI infrastructure is a genuine bottleneck. Open AI, Anthropic, and other frontier AI labs are power-constrained. They can't build models larger or faster than power infrastructure allows. If you're building AI companies, investing in infrastructure, or making decisions about where to put your resources, understanding the real timeline for next-generation compute matters.

If space-based compute was real by 2027, it would reshape everything. Competition would intensify. Pricing would change. New players could enter. But it's not real by 2027. That's worth knowing.

Meanwhile, other opportunities exist. More efficient algorithms. Better chip designs. Novel cooling approaches. Understanding that Musk's timeline is unrealistic should redirect attention toward what's actually achievable in the next three years.

For teams building productivity tools and automation platforms (like Runable, which helps teams automate workflows with AI), the compute infrastructure bottleneck is real but the three-year space compute solution isn't. Plan infrastructure assuming terrestrial compute availability. Build tools that work efficiently with current hardware. That's the practical approach.

The Honest Assessment

Musk's statement about space-based AI compute being the cheapest option within three years is more marketing than prediction. It's aspirational. It's visionary. It's the kind of statement that attracts capital, talent, and attention.

But it's not realistic.

The technology is decades of engineering away from price competitiveness with terrestrial infrastructure. Launch costs need to improve more. Hardware needs specialization. Thermal systems need maturation. Regulatory frameworks need establishment. Economies of scale need to develop. All of this takes time.

Musk might well be right that space-based compute is inevitable. Maybe in the 2040s or 2050s, orbital data centers support a meaningful fraction of global AI compute. That's a real possibility.

But three years? That's science fiction. And there's nothing wrong with acknowledging that, even when the person making the prediction is usually right about long-term direction.

The most honest assessment is this: the vision might be sound, but the timeline is fantasy. Plan your infrastructure and business decisions accordingly.

Looking Forward: What to Actually Expect

Over the next three years, here's what you should realistically expect:

Space X will continue improving Starship. Flights will increase in frequency and reliability. Launch costs will decrease, though maybe not to the promised $10/kg. This is a genuine achievement and it matters for lots of applications.

x AI will continue developing AI models. Space X's launch capability might give them some operational advantages, but they'll still use mostly terrestrial infrastructure. Their models won't run primarily in space.

Research into space-based computing will continue. Some universities and companies will do interesting experiments. A few demonstrations will launch. They'll be impressive and they'll also be expensive proof-of-concept projects.

Meanwhile, Earth-based AI infrastructure will keep improving. Efficiency gains will mount. New data center designs will emerge. Custom chips will specialize further. The gap between what's practical on Earth and what's practical in space will remain enormous.

By 2027, we might have demonstrated that some kinds of compute can work profitably in space, at least for niche applications. But the cheapest way to generate AI compute? That's still terrestrial. And it will be for years beyond Musk's prediction.

Understanding this helps you make better decisions about infrastructure, investment, and technology bets. The future is genuinely exciting. It's also slower to arrive than optimistic pronouncements suggest.

FAQ

What exactly is Elon Musk claiming about space-based AI compute?

Musk claims that within three years (by roughly 2027), deploying artificial intelligence compute systems in orbit will be the lowest-cost method of generating AI computational power compared to traditional Earth-based data centers. This statement was made following Space X's acquisition of a stake in x AI, Musk's AI company, suggesting the two organizations might pursue this vision together.

Why are space-based data centers theoretically advantageous?

Space offers several theoretical advantages for computing infrastructure. Satellites in orbit experience continuous or near-continuous sunlight, providing free solar power without Earth's night cycles or weather obstruction. Space also provides infinite heat rejection capability through radiative cooling to the vacuum, potentially eliminating cooling costs that plague terrestrial data centers. Additionally, space-based infrastructure isn't constrained by geographical limitations, political borders, or land availability, offering unlimited expansion potential as computational demands grow.

What are the main technical barriers to achieving Musk's timeline?

Multiple engineering challenges must be solved simultaneously. Launch costs need to decrease dramatically, which depends on Starship reaching full operational capability with frequent flights (likely 2029+ realistically). Radiation-hardened computing hardware requires custom semiconductor design for space environments, a 2-4 year project. Thermal management systems need development, testing, and redundancy validation, likely taking 2-3 years. Additionally, building an operational constellation requires architectural design, regulatory approval from the FCC and international bodies, and solving complex software coordination problems. Each of these independently would require years to properly execute.

How accurate has Musk been with three-year technology predictions historically?

Musk's track record shows consistent timeline optimism. Tesla's Full Self-Driving was promised as complete by 2019 and remains in beta in 2025. Starship's orbital flight was predicted for 2020 and achieved in 2023. Neuralink human trials were projected for 2019 and conducted in 2024. Mars landing timelines have repeatedly slipped by years. This pattern suggests that Musk's three-year orbital compute prediction likely understates the actual timeline by 3-5 years minimum, given the unprecedented integration of aerospace engineering with cutting-edge AI infrastructure.

What would a realistic timeline for space-based AI compute actually look like?

A realistic assessment suggests the following progression: Starship reaching dependable low-cost launch capability by 2029-2031, custom radiation-hardened compute hardware development by 2027-2028, thermal management system maturation by 2027-2029, constellation architecture completion by 2026-2028, regulatory approval by 2028-2030, and first operational revenue-generating orbital compute constellation by 2031-2034. Achieving actual price competitiveness with terrestrial data centers would likely require additional years of operational experience, optimization, and scale development, realistically pushing price parity to 2035-2040 or beyond, assuming space-based infrastructure matures at all.

How does Space X's acquisition of x AI relate to space-based computing plans?

The Space X acquisition of a stake in x AI suggests Musk's intention to vertically integrate AI computational capacity with launch capability. This allows theoretical optimization of the entire pipeline from launch through operational compute. However, acquiring an AI company doesn't fundamentally accelerate the underlying engineering challenges of deploying compute infrastructure in space. It provides captive demand for future space-based compute capacity and aligns incentives between the companies, but it doesn't solve physics problems, radiation hardening challenges, or regulatory timelines any faster than they can naturally progress.

What alternatives to space-based compute are more realistic in the three-year timeframe?

More tractable approaches include improving terrestrial data center efficiency through advanced cooling techniques like immersion cooling, optimized chip architecture design, and power management innovations that could reduce costs 30-50% over five years. Distributed edge computing networks spread processing closer to data sources, reducing transmission costs and latency without requiring orbital infrastructure. Finally, power-aware algorithm design through quantization, knowledge distillation, and sparse model approaches reduces computational requirements and hardware costs, potentially allowing efficient models on cheaper infrastructure to outperform resource-intensive approaches.

Why does the timeline matter for AI infrastructure decisions?

Artificial intelligence development is genuinely power-constrained. Frontier AI labs can't build larger models faster than electrical power infrastructure allows. Understanding whether revolutionary new compute sources arrive in three years versus ten years fundamentally changes infrastructure investment decisions, business planning, and technology bets. If you're building AI applications, investing in computing infrastructure, or making long-term technical decisions, knowing that space-based compute is likely decades away rather than three years away refocuses planning toward practical improvements to terrestrial systems that are actually achievable in realistic timeframes.

Conclusion: Vision Versus Realism

Elon Musk deserves credit for audacious thinking. The vision of computational infrastructure in space isn't ridiculous. It's not impossible. It's actually plausible as a long-term development spanning decades. But that's not what he claimed. He claimed three years.

That claim confuses possibility with imminence. It mistakes innovation with inevitability. Most importantly, it misunderstands engineering timelines.

Building transformative infrastructure requires solving multiple hard problems simultaneously. Each one sounds simple from thirty thousand feet. Each one is brutally complex at the engineering level. Integrating them without devastating cost overruns and schedule delays is the real achievement.

Historically, major infrastructure projects—whether satellite networks, power systems, or transportation infrastructure—take 10-20 years from conception to operational scale. Space X is exceptionally good at execution, but even exceptional execution can't overcome fundamental physics or regulatory realities.

The honest assessment is that Musk's three-year timeline reflects optimism, not prophecy. The genuine timeline is more like a decade, and that assumes nearly everything goes right. More realistically, price-competitive space-based AI compute is a 2040s+ phenomenon, if it happens at all.

This doesn't mean you should ignore space-based computing developments. Watch them. They're technically fascinating and potentially important long-term. Study the problems Space X and other organizations solve. But don't build your infrastructure plans or business strategy assuming orbital compute is available at competitive prices in three years.

The real opportunities in the next three years are improving what we have: more efficient algorithms, better chip designs, innovative cooling approaches, and distributed architectures. These are proven. They're improvable. They're within engineering grasp.

Space-based compute is a generation away. Planning accordingly is the practical choice, regardless of how impressive the vision sounds today.

The future is genuinely exciting. It's also slower than the most optimistic voices predict. Understanding that distinction makes you a better decision-maker.

Key Takeaways

- Musk's three-year timeline for space-based AI compute being cheaper than terrestrial infrastructure is aspirational rather than realistic based on historical precedent

- Realistic deployment of profitable orbital compute infrastructure requires solving launch costs, thermal management, radiation hardening, constellation architecture, and regulatory approval simultaneously—a 10+ year effort

- Earth-based data center infrastructure continues improving through efficiency gains, custom chips, and innovative cooling—reducing the gap space-based systems must overcome

- SpaceX's acquisition of xAI aligns incentives for vertical integration but doesn't accelerate underlying engineering challenges or fundamental physics constraints

- A more practical three-year focus should be improving terrestrial compute efficiency, distributed edge networks, and power-aware algorithms rather than waiting for orbital infrastructure

Related Articles

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: The 1 Million Satellite Gambit for AI Compute [2025]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: Inside Musk's $1.25 Trillion Data Center Gamble [2025]

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: Creating the World's Most Valuable Private Company [2025]

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: Building a 1 Million Satellite AI Powerhouse [2025]

- SpaceX's 1 Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

![Space-Based AI Compute: Why Musk's 3-Year Timeline is Unrealistic [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/space-based-ai-compute-why-musk-s-3-year-timeline-is-unreali/image-1-1770172601368.jpg)