Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Social Media Addiction: What Changed [2025]

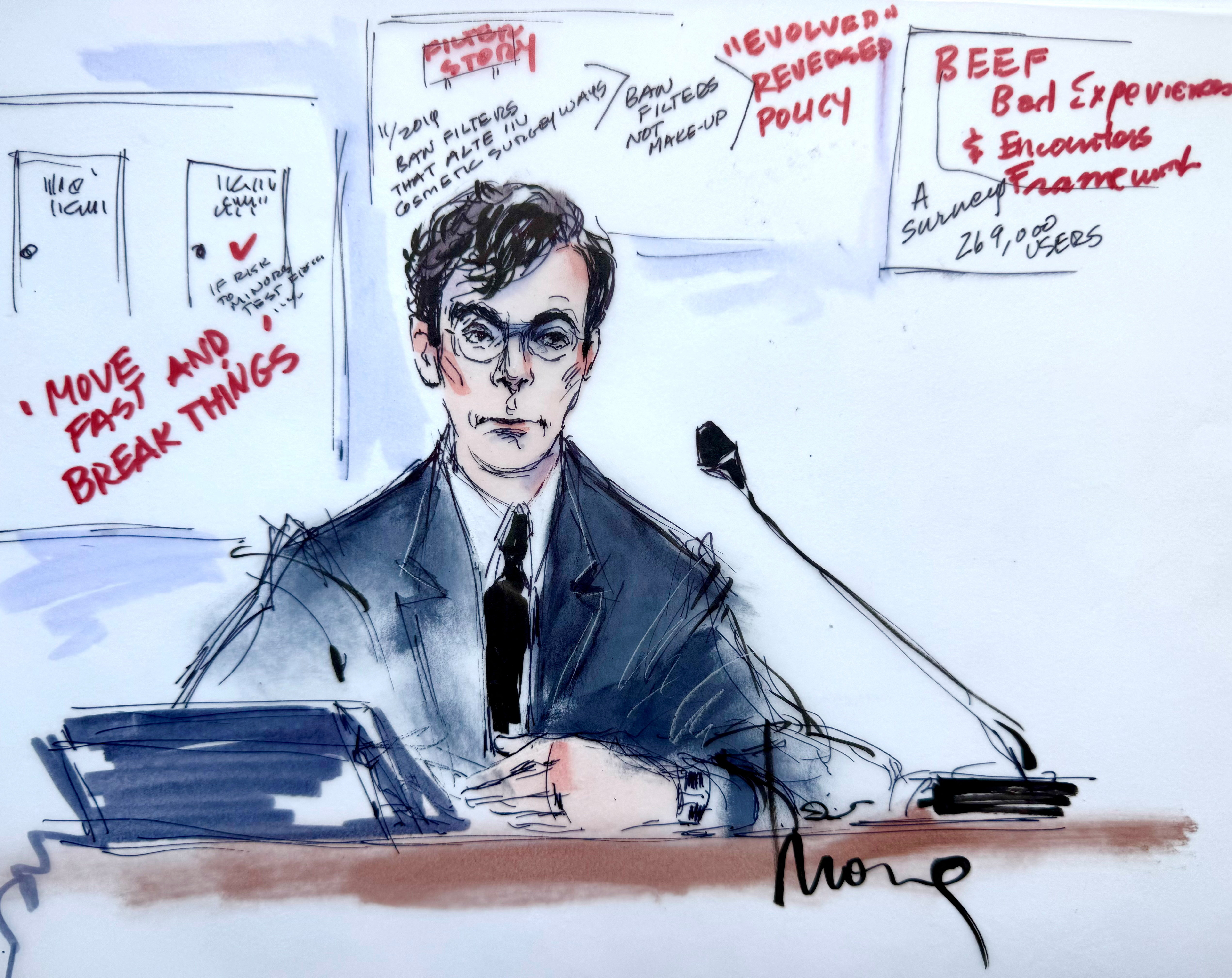

Mark Zuckerberg sat in a Los Angeles courtroom on Wednesday and made a bold claim: Meta doesn't care about making Instagram addictive. Instead, the company insists it's focused on making the platform "useful." According to CNBC, this statement was part of a broader defense strategy during a landmark trial.

It's the kind of statement that sounds reasonable in a vacuum. But when you dig into what "useful" actually means in the context of social media—and when you examine the historical documents that came up during his testimony—the picture gets a lot messier. As reported by PBS, the trial has brought to light internal documents that challenge Meta's narrative.

This trial, brought by a California woman identified as "KGM" in court documents, represents a watershed moment for Big Tech. It's the first time a major social media founder has had to defend his platform's design philosophy in front of a jury. The implications stretch far beyond this single lawsuit. They touch on how platforms are built, what incentives drive their product decisions, and whether regulators can actually hold these companies accountable. BBC News highlights the broader regulatory implications of this case.

The Trial That Changed Everything

This isn't some minor IP dispute or contract disagreement. This is a jury trial that questions whether Meta deliberately engineered Instagram to be addictive to children. The plaintiff, now 20 years old, alleges that Instagram's design features harmed her during her childhood—features that were specifically engineered to keep her coming back. According to Lawsuit Information Center, this case could set a precedent for future litigation against tech companies.

The reason this matters so much is that it challenges the fundamental excuse tech companies have used for years: "We're just giving people what they want." If a jury agrees that the platforms were deliberately designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities, it opens the door to liability, regulation, and potentially massive damages. PBS reports that Zuckerberg's testimony is a critical component of Meta's defense strategy.

Zuckerberg's appearance is notable because he rarely testifies in court anymore. He's worth over $200 billion, runs one of the most influential companies in human history, and has the resources to send his legal team to handle almost anything. The fact that he personally showed up suggests Meta's legal advisors thought his presence mattered. Maybe they thought his charm and technical credibility could sway a jury. Or maybe they felt he needed to be there to make the credibility argument work. Yahoo Finance notes the significance of his personal involvement in the trial.

What actually happened was described by multiple outlets as "combative." That's journalist code for: the conversation didn't go the way Meta probably hoped. NPR provides insights into the courtroom dynamics.

Estimated data suggests internal documents and engagement metrics are crucial in the trial, with high importance scores. Zuckerberg's testimony and the concept of 'usefulness' are also significant but slightly less so.

What Zuckerberg Actually Said About "Usefulness"

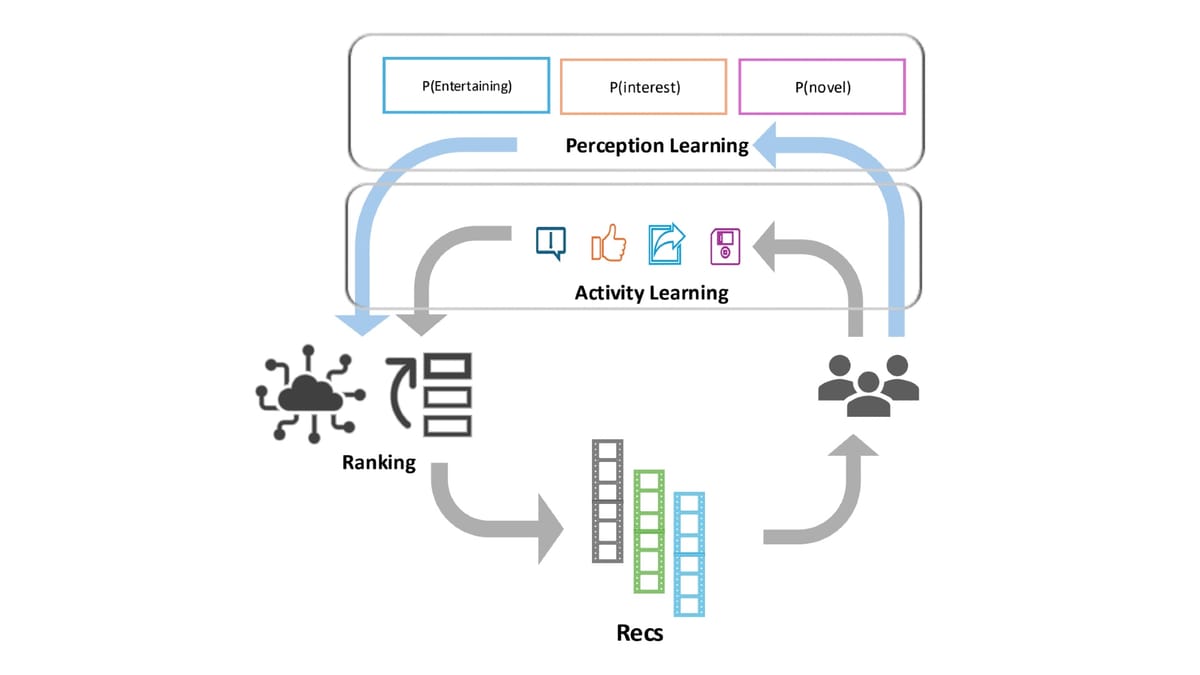

On the stand, Zuckerberg argued that Meta had "made the conscious decision to move away from" engagement-focused goals, instead focusing on what the company calls "utility." If something is useful, he reasoned, people will naturally use it more—not because they're trapped in a compulsion loop, but because the product genuinely serves their needs. This strategy was highlighted in Engadget's coverage of the trial.

It's a clever rhetorical move. It takes the accusation (your platform is designed to be addictive) and reframes it as a feature (our platform is designed to be useful). But here's the problem: the evidence introduced at trial suggests that engagement and usefulness weren't always treated as separate things at Meta. PBS reports that internal documents contradict this narrative.

Prosecutors apparently showed documents where "improving engagement" was listed among company goals. When asked about this contradiction, Zuckerberg claimed the company had shifted priorities. But the timing matters. When did this shift happen? Was it before KGM was using Instagram, or after the company realized it might face lawsuits? BBC News explores these critical questions.

This is where the trial gets genuinely interesting from a legal and strategic perspective. Courts don't typically care about a company's stated intentions—they care about what the evidence shows the company actually did. If Meta's internal documents reveal that engagement metrics drove product decisions, then Zuckerberg's testimony about the company's current philosophy becomes less relevant. What matters is what the company incentivized and rewarded. CNBC provides further analysis on this aspect of the trial.

Estimated data suggests that engagement metrics and user growth are highly prioritized in internal documents. This can challenge claims that these factors didn't drive company behavior.

The Historical Documents That Contradicted His Testimony

One of the most damaging moments came when Zuckerberg was confronted with his own previous public statements. He'd said on Joe Rogan's podcast that he can't be fired by Meta's board because he controls the majority voting power. When lawyers brought this up, he accused them of "mischaracterizing" his past comments—more than a dozen times, according to reports. Engadget highlights this aspect of the trial.

This pattern is significant. When you're on the stand and you keep saying "you're mischaracterizing me," it does two things: it makes you sound defensive, and it suggests the original statements are hard to defend on their face. A jury watching this play out might reasonably think: if these statements were so commonly mischaracterized, why did you phrase them that way in the first place? PBS provides further insights into the courtroom dynamics.

But the bigger issue is the internal documents. Tech companies like Meta generate millions of internal communications every year—emails, Slack messages, product design documents, metrics dashboards, quarterly planning documents. Lawyers can subpoena all of this. And when those documents show that a team was celebrating a 15% increase in daily active users, or that promotions were tied to engagement metrics, or that product decisions were justified based on "time spent in app," it becomes very difficult to claim the company wasn't prioritizing engagement. CNBC reports on the significance of these documents.

The challenge for Zuckerberg's defense is that he has to argue that all of those historical incentives didn't actually drive behavior the way they appear to have. It's like arguing that a building has a staircase leading to the roof, but people only take it when the roof is genuinely useful—not because the staircase is there and accessible. BBC News explores this analogy in detail.

What "Addiction" Actually Means in Court

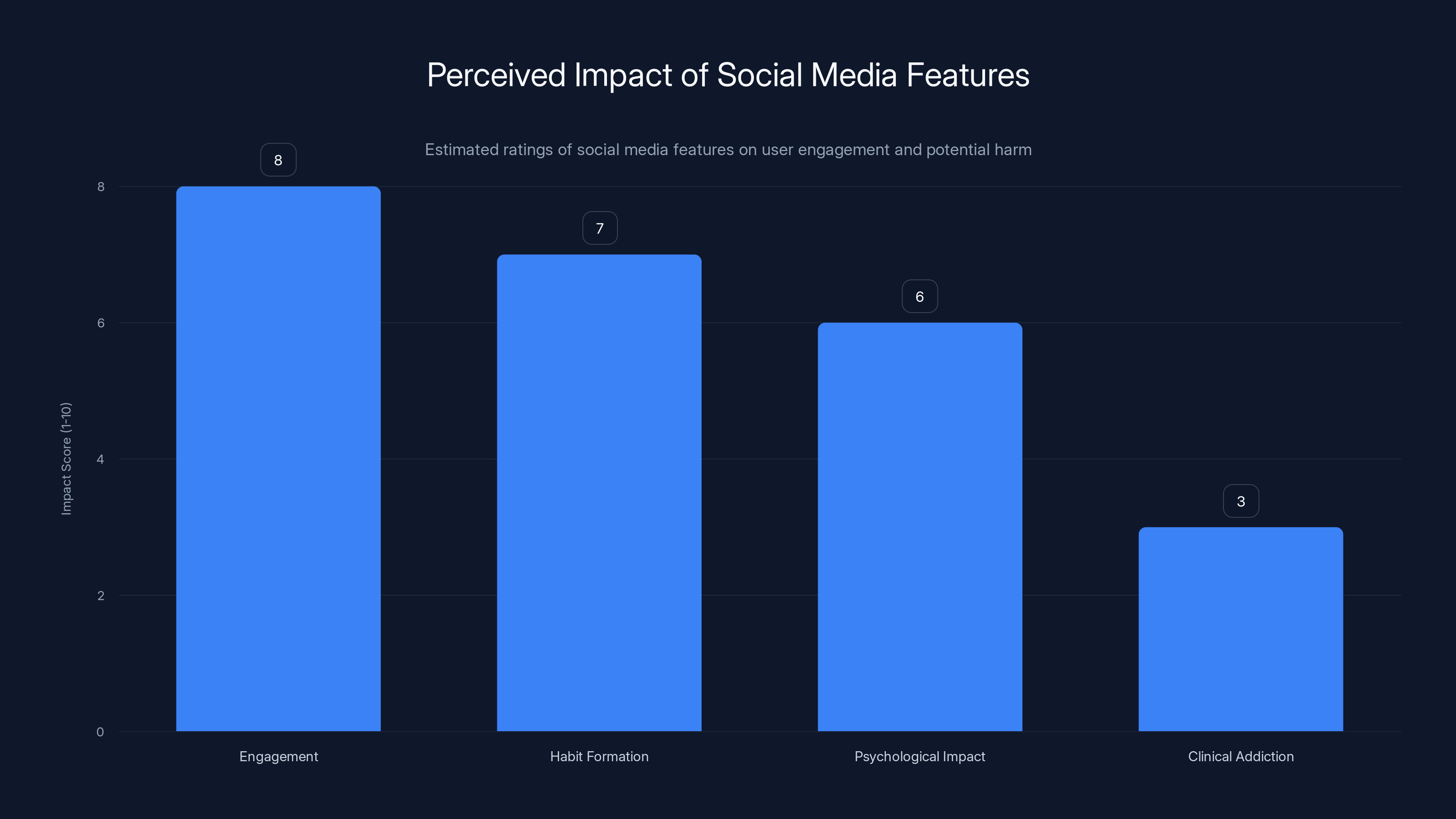

One detail that's been underreported: Meta's lawyers have explicitly argued that social media shouldn't be considered "addictive" in the clinical sense. Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram, testified that the platform isn't "clinically addictive." PBS provides insights into this argument.

This is a deliberate semantic strategy. "Addiction" in clinical terms refers to a psychiatric condition with specific diagnostic criteria. It's not the same as "habitually using something" or "finding something engaging." Meta's argument is essentially: yes, people use Instagram a lot, but that doesn't mean it's addictive in the medical sense, so we shouldn't be liable for addiction-related harms. Engadget discusses this defense strategy.

The problem with this defense is that it misses the point of the lawsuit. The plaintiff isn't claiming she was "clinically addicted" in the sense that she has a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. She's claiming that Meta designed features specifically to exploit reward mechanisms in the brain—mechanisms that make it harder to disengage from the platform. That's not the same as clinical addiction, but it might still constitute deliberate harm. BBC News explores the nuances of this argument.

This is where the trial actually becomes about first principles. What responsibility do platforms have for the psychological effects of their design? If you engineer a feature to trigger dopamine release, and you know it will cause people to spend more time on your platform, does the clinical status of their eventual behavior matter legally? Or is the intent to manipulate itself the problem? CNBC provides further analysis on these questions.

These aren't settled questions. The courts are figuring them out in real time.

Estimated data suggests that while social media features are highly engaging and may form habits, they are perceived as less impactful in terms of clinical addiction. Estimated data.

The AI Glasses Controversy: A Weird Subplot

One of the strangest moments from the trial wasn't about testimony at all. As Zuckerberg was being escorted into the courthouse, members of his entourage were wearing Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses. A judge was so concerned about the possibility of recording or facial recognition that she had to warn people not to use the glasses in court. PBS reports on this unusual incident.

It's almost comically on-the-nose. Here's Meta's CEO, defending himself against charges that his company builds products designed to manipulate and surveil users, and he rolls up with surveillance glasses. Whether intentional or not, it became a visual metaphor for the trial itself. Engadget highlights the irony of the situation.

Meta's glasses don't currently have native facial recognition, though reports suggest the company is developing that capability. But the judge's concern reveals something important: there's genuine anxiety about surveillance and control around these products. And that anxiety isn't coming from nowhere. It's built on years of reporting about data collection, privacy violations, and features that users don't fully understand. CNBC provides further context on the privacy concerns.

When a judge has to warn people not to use your product in her courtroom, your product's reputation problem is real.

Why This Trial Matters Beyond Meta

This case is being watched because it's precedent-setting. It's one of the first high-profile trials where a social media company's design philosophy is being examined in detail. But it's not the only one. Meta is also facing a separate proceeding in New Mexico with similar allegations. And there are dozens of similar lawsuits working their way through courts across the country. PBS highlights the broader implications of this trial.

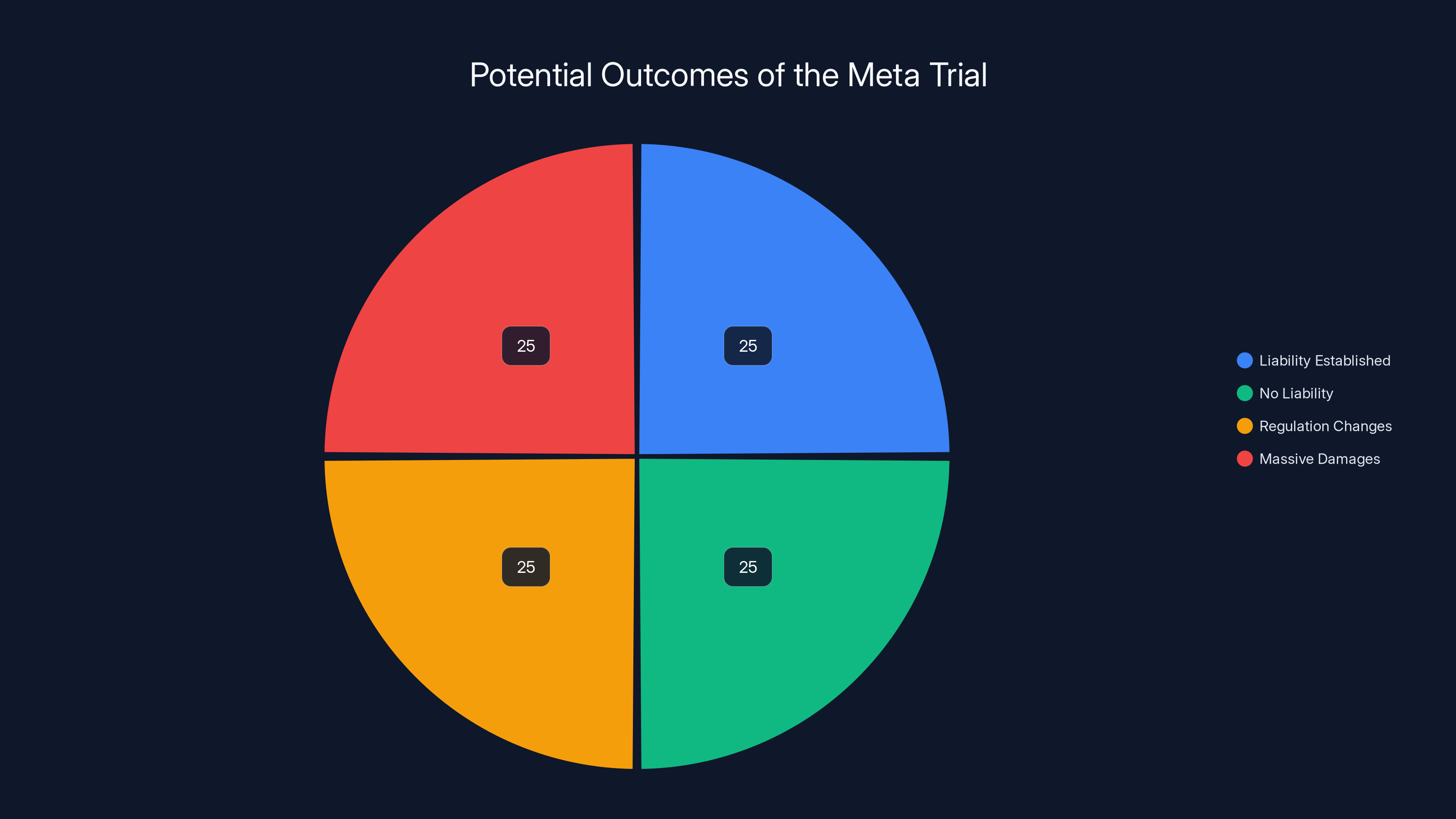

If KGM wins—if a jury agrees that Meta deliberately designed Instagram to be addictive to children—it fundamentally changes the legal landscape. Other platforms would face much higher litigation risk. Damages could be substantial. And, critically, regulators would have a precedent for arguing that these companies knowingly designed harmful products. CNBC explores the potential outcomes of the trial.

If Meta wins, it sends a different signal: social media companies have broad latitude to design their platforms however they want, as long as they can claim the features serve some legitimate purpose. That's a much weaker standard. Engadget discusses the implications of a potential Meta victory.

The stakes are enormous. And unlike regulatory battles in Congress, which are slow and subject to lobbying pressure, court verdicts are final. A jury can't be lobbied. They can't be influenced by a company's PR budget. They either believe the evidence or they don't. BBC News provides further insights into the significance of the trial.

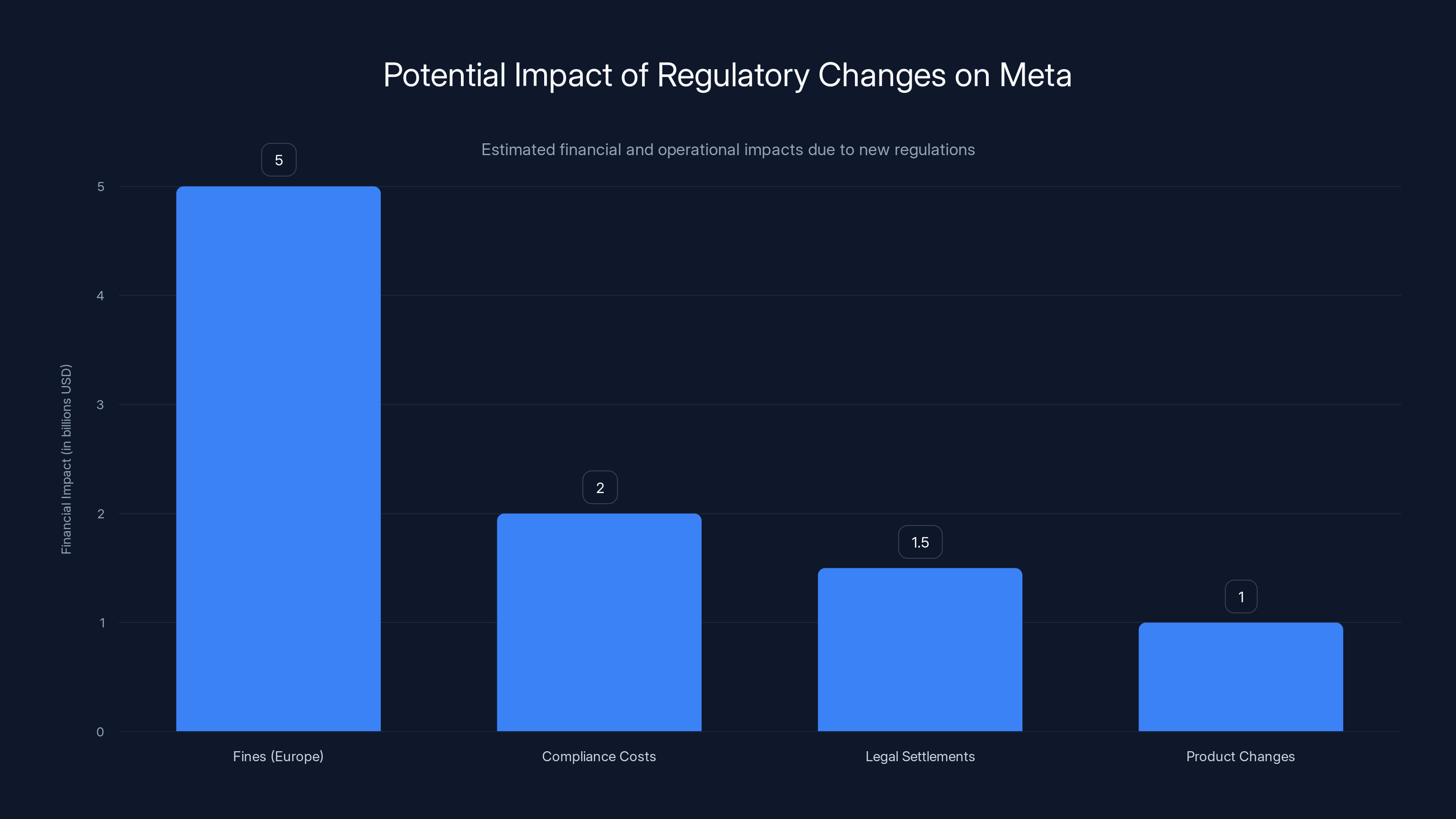

Estimated data suggests that regulatory changes could cost Meta billions in fines, compliance, and settlements. Product changes might also incur significant costs.

What the Evidence Reveals About Meta's Culture

Zuckerberg's testimony, and the trial more broadly, has made something clear: Meta was obsessed with engagement metrics for a very long time. This isn't speculation or conspiracy theory. It's documented in internal communications, product planning documents, and executive presentations. PBS reports on the internal culture at Meta.

Engagement is how Meta makes money. More time in app equals more ads served equals more revenue. So naturally, the company's incentive structure has always rewarded people who figured out how to increase engagement. That's not surprising. It's also not sinister in the abstract—companies optimize for their revenue drivers all the time. CNBC provides further analysis on Meta's business model.

But when you're optimizing for engagement among children, and when the mechanisms you use to drive engagement are deliberately engineered to exploit psychological vulnerabilities, the ethics become questionable. And if you did this while having internal research showing the harms, the legal liability becomes real. Engadget explores the ethical implications of Meta's strategies.

Meta has conducted internal research on Instagram's effects on teenage mental health. Some of this research has leaked over the years. It shows the company knew about negative effects—increased anxiety, body image issues, sleep disruption—but continued pursuing the same engagement-focused strategies anyway. BBC News reports on the internal research findings.

Zuckerberg's testimony didn't really address this head-on. He talked about making the platform "useful" and claimed a shift in philosophy. But he didn't explain why, if the company was so concerned about usefulness, it didn't prioritize mental health research earlier. He didn't explain the gap between what internal research showed and what the company publicly claimed. PBS provides further insights into these contradictions.

The Timing Question: When Did Meta Change?

One of the most important unresolved questions from the trial is timing. When exactly did Meta shift from prioritizing engagement to prioritizing "usefulness"? Was it before KGM joined Instagram in 2010-ish? Or was it after lawsuits started appearing? CNBC explores the significance of the timing question.

If the shift was recent, it significantly undermines Zuckerberg's defense. It suggests that Meta only changed course when facing legal pressure, not because the company independently decided engagement-focused design was problematic. Engadget discusses the implications of a recent shift.

The trial evidence will hopefully make this clear. If there are product decisions, org restructures, or metric changes that can be dated, the jury will see them. They'll see whether Meta was pushing hard on engagement in 2010, 2015, 2018, and when that changed. BBC News provides further analysis on the evidence presented.

This timing question matters for causation. The lawsuit claims Instagram's design caused harm to KGM. If Meta's design was engagement-focused during the years KGM was using the app, that's direct causation. If Meta had already shifted away from engagement-focused design by the time she joined, that weakens the claim. PBS explores the legal implications of the timing question.

But Zuckerberg's testimony suggested the shift was recent and deliberate. "We made the conscious decision to move away," he said. That language implies it was a choice the company made, not something that naturally evolved. And it implies the choice was relatively recent. CNBC provides further insights into Zuckerberg's testimony.

Estimated data: The trial could lead to liability, regulatory changes, or massive damages, each with an equal likelihood of 25% based on the trial's significance and potential impact.

What "Usefulness" Obscures

There's something clever about the way Meta frames this. By claiming the company prioritizes "usefulness," they're making an argument that's almost impossible to disprove. How do you prove something isn't useful? Usefulness is subjective. If someone uses Instagram to stay connected with friends, that's genuinely useful to them. The fact that the platform also shows them content designed to maximize engagement doesn't negate the usefulness. Engadget discusses the rhetorical strategy behind Meta's defense.

So Meta's strategy is: admit the platform is engaging, but reframe engagement as a consequence of usefulness, not a goal in itself. People use it more because it's useful, not because we engineered it to be addictive. BBC News explores the implications of this strategy.

It's a smart rhetorical move. But it assumes the jury won't look closely at how "usefulness" was actually defined inside Meta. Did the company measure usefulness? What metrics did it use? Or is "usefulness" just a label they're applying retroactively to justify engagement-focused design? CNBC provides further analysis on the evidence presented.

If internal documents show that Meta measured success primarily through engagement, then their claim to prioritize usefulness becomes harder to believe. You measure what you care about. If you measure engagement, you care about engagement. PBS explores the contradictions in Meta's defense.

The Broader Regulatory Implications

This trial is happening against a backdrop of increasing regulatory scrutiny. The EU has passed the Digital Services Act, which imposes strict requirements on how large platforms can design their products, especially for minors. Several US states have passed laws restricting how platforms can collect data from children. There's talk in Congress of comprehensive social media regulation. BBC News provides insights into the regulatory context.

Zuckerberg's testimony and the evidence presented at trial will almost certainly be cited in these regulatory debates. If a jury finds that Meta deliberately designed Instagram to be addictive, that's ammunition for regulators arguing that comprehensive rules are necessary. CNBC explores the potential regulatory outcomes.

Conversely, if Meta wins, if a jury agrees that social media engagement is just a natural consequence of usefulness, then the regulatory case becomes harder. You can't regulate something that's just a natural market outcome. Engadget discusses the implications of a potential Meta victory.

So this trial isn't just about KGM and her damages. It's about establishing a factual record that will shape policy for years to come. PBS highlights the broader implications of the trial.

The Mental Health Question: What Does the Research Actually Show?

Underlying this whole trial is a simple factual question: does Instagram harm teenage mental health? The answer, based on independent research, appears to be yes—but with important caveats. BBC News reports on the mental health implications of social media use.

Multiple studies have found correlations between heavy social media use and increased rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues among teenagers. But correlation isn't causation. It's possible that teenagers with existing mental health issues use social media more, rather than social media causing the issues. CNBC provides further analysis on the research findings.

Meta has funded research arguing that the relationship is more complex and less harmful than critics suggest. Independent researchers have pushed back, noting that Meta's research tends to reach different conclusions than peer-reviewed studies. The scientific community hasn't reached complete consensus, though the preponderance of evidence suggests some harm, particularly for heavy users. Engadget explores the nuances of the research.

In the trial context, this becomes important because the defendant can claim: the science is unclear, so it's unreasonable to say Meta deliberately caused harm. The plaintiff has to show that Meta designed features knowing they would cause harm. If the harm itself is scientifically contested, that's a harder argument to make. PBS provides further insights into the legal implications of the research.

But if internal Meta research showed the company knew about harms while continuing to pursue engagement-focused design anyway, that becomes a different story. You can be liable for harm even if the science is contested, if you knowingly caused it. BBC News explores the implications of internal research findings.

What Comes Next: The Verdict and Beyond

The trial is ongoing, so the verdict hasn't come down yet. But based on how these things typically unfold, here's what to watch for:

First, look at jury selection and composition. Did the jury include people with teenage children or younger siblings? Are there tech workers on the jury who might have insider knowledge of how these companies operate? Jurors' personal experiences with social media will influence how they interpret the evidence. CNBC provides insights into the jury selection process.

Second, watch for how the defense characterizes the evidence. If Meta's lawyers spend a lot of time arguing that correlation isn't causation, that's a sign they're worried about the psychological research. If they focus on freedom of speech and market competition, they're trying to move the conversation away from the specific evidence. Engadget discusses the defense strategy.

Third, pay attention to the damages discussion if the plaintiff wins. Judges and juries award damages based on what they think the company did wrong and how much harm resulted. If they award significant damages, it signals they believe Meta acted knowingly and caused substantial harm. BBC News explores the potential outcomes of the trial.

Finally, watch for what other courts do. If KGM wins, expect dozens of similar cases to move forward more aggressively. Defendants will push harder for settlement. Regulators will cite the verdict. If Meta wins, the opposite happens—lawsuits get dismissed, settlements become less likely, and regulators face an uphill battle arguing for strict social media rules. PBS provides further insights into the broader implications of the trial.

The Precedent Question: What Should Tech Company Responsibility Look Like?

Underlying all of this is a bigger question: what should we expect from tech companies in terms of responsibility for their products' effects?

One view holds that companies should be held strictly liable for any harm caused by their products. If Instagram contributes to teen anxiety, Meta is responsible for damages and must change the product. CNBC explores the potential legal implications.

Another view holds that companies should only be liable if they deliberately caused harm knowing it would happen. Simple negligence or failure to prevent harm isn't enough. This is a higher bar for plaintiffs to clear. Engadget discusses the legal standards involved.

A third view holds that companies should face regulatory oversight before a lawsuit is necessary. The government should set rules about what product design is allowed, and companies that violate those rules face fines and remedies. This is the EU's approach with the Digital Services Act. BBC News provides insights into the regulatory context.

Zuckerberg's testimony suggests Meta wants courts to adopt the middle view: we're only liable if you can prove we deliberately caused harm. And we didn't deliberately cause harm—we were just making the platform useful, and engagement was a natural consequence. PBS explores the implications of Meta's defense strategy.

The jury will ultimately decide which view prevails in this specific case. But the broader debate will continue regardless of the verdict. Society is having a real conversation about tech company responsibility. Courts, regulators, and the public are all weighing in. The outcome of this trial will influence that conversation but won't settle it completely. CNBC provides further analysis on the broader implications of the trial.

Why The Courtroom Fight Matters More Than the Verdict

Even if Meta wins the trial, something important has already happened: the company's decision-making process has been exposed. Internal documents, product metrics, and strategic choices have been scrutinized publicly. That scrutiny has already influenced how people think about Meta. Engadget discusses the implications of the trial's public scrutiny.

Zuckerberg showed up in court in person, which means his credibility is now on the line. Whether the jury believed him or not, his testimony is part of the public record. When he said the company made a "conscious decision" to move away from engagement metrics, that claim is now testable. Someone can look at the dates of that decision and compare them to when lawsuits started appearing. BBC News explores the implications of Zuckerberg's testimony.

This is the real power of the court system for these kinds of cases. It's not just about damages or liability. It's about forcing companies to tell the truth under oath and expose their decision-making to public scrutiny. That creates pressure that regulatory agencies and Congress can leverage. CNBC provides further analysis on the trial's significance.

If Zuckerberg's testimony is compelling and the jury believes him, Meta emerges with some vindication. But if the testimony seems evasive or is contradicted by documents, the damage to the company's reputation and political standing is real—regardless of the jury's verdict on liability. PBS explores the potential outcomes of the trial.

Looking Forward: What Changes Are Coming

Whether Meta wins or loses this trial, the trajectory is clear: social media companies will face increasing scrutiny and regulation. BBC News provides insights into the future of social media regulation.

In Europe, the Digital Services Act is already in effect. Companies that violate its provisions face fines up to 6% of global revenue. For Meta, that could mean billions of dollars in penalties. CNBC explores the potential financial implications for Meta.

In the US, multiple states have passed or are considering laws restricting how platforms can target content to minors. Congress has been discussing comprehensive social media regulation for years. This trial will inform those debates. Engadget discusses the potential regulatory outcomes.

For Meta specifically, the most likely scenario is a combination of legal settlements, regulatory compliance costs, and product changes. The company will probably reach settlements with some of these lawsuits. It will implement new safeguards to comply with regulations. It might restructure how Instagram operates for minors. PBS provides further insights into the potential changes for Meta.

But the fundamental business model—making money by serving ads to engaged users—is unlikely to change. Instead, Meta will optimize within the constraints imposed by law and regulation. BBC News explores the implications for Meta's business model.

Zuckerberg's testimony is part of that evolving story. It's not the whole story, but it's a significant chapter. The outcome of this trial will shape what comes next. CNBC provides further analysis on the trial's significance.

Conclusion: A Moment of Reckoning

Mark Zuckerberg testified that Meta's goal is to make Instagram "useful," not addictive. It's a simple statement that encapsulates a much larger debate about tech company responsibility. Engadget discusses the implications of Zuckerberg's testimony.

The evidence suggests the reality is more complicated. Meta spent years optimizing for engagement. Engagement is closely related to addiction-like usage patterns. The company knew about negative effects from its internal research. And the shift toward "usefulness" as a guiding principle appears to be relatively recent. BBC News explores the contradictions in Meta's defense.

Whether a jury agrees with this interpretation remains to be seen. But the trial itself has already accomplished something important: it's forced Meta to defend its design philosophy in public, under oath, with evidence. That's a rare moment for a company of Meta's size and influence. CNBC provides further analysis on the trial's significance.

The broader implication is that tech companies are increasingly vulnerable to legal and regulatory challenges. The era of move-fast-and-break-things is ending. Companies now have to answer for the things they break. PBS explores the implications for the tech industry.

For Meta, that's a significant shift. For everyone else, it's a reminder that even the most powerful companies aren't above accountability. They just had to be taken to court to prove it. BBC News provides further insights into the trial's broader implications.

FAQ

What is the social media addiction trial about?

The trial focuses on whether Meta deliberately engineered Instagram's features to be addictive to children. A California woman identified as "KGM" filed suit claiming that Instagram's design features harmed her during her childhood by exploiting psychological vulnerabilities. The case examines internal company documents and strategic decisions to determine if Meta prioritized engagement metrics specifically to create addictive user behavior. PBS provides further insights into the trial.

Why is Mark Zuckerberg's testimony significant?

Zuckerberg's in-court appearance is rare for a CEO of his stature and wealth. His testimony is significant because he personally defended Meta's product philosophy, claiming the company prioritizes "usefulness" over engagement. However, his testimony was reportedly combative, and prosecutors confronted him with internal company documents suggesting engagement was historically a core company goal, creating contradictions the jury must evaluate. CNBC provides further analysis on Zuckerberg's testimony.

What does "usefulness" mean in Meta's defense?

Meta argues that if Instagram is genuinely useful for connecting people, users naturally spend more time on the platform—not because they're trapped in an addiction loop. However, the defense's credibility depends on whether internal documents show the company actually measured and prioritized usefulness, or whether it historically prioritized engagement metrics that may have secondarily created addictive behavior patterns. Engadget discusses the implications of Meta's defense strategy.

What internal documents were used as evidence in the trial?

Prosecutors presented company documents showing that "improving engagement" was listed among Meta's official company goals. These documents contradict Zuckerberg's claim that Meta moved away from engagement-focused objectives. The timing and content of these documents are crucial because they reveal what the company actually incentivized and prioritized historically. PBS provides further insights into the evidence presented.

What is the difference between clinical addiction and problematic social media use?

Clinical addiction is a diagnosable psychiatric condition with specific medical criteria. Problematic social media use may not meet clinical addiction standards but could still involve compulsive behavior and psychological harm. Meta's defense relies on the distinction that Instagram isn't "clinically addictive," but this sidesteps whether the platform was deliberately designed to exploit reward mechanisms and create compulsive usage patterns. BBC News explores the nuances of this argument.

How could this trial affect social media regulation?

If the jury finds Meta deliberately designed Instagram to be addictive, it strengthens the legal and political case for comprehensive social media regulation. The verdict could serve as precedent for other lawsuits and evidence that regulators can cite when proposing restrictions on how platforms target content to minors and design engagement-focused features. CNBC explores the potential regulatory outcomes.

What happened with the Ray-Ban glasses incident in the courtroom?

Members of Zuckerberg's entourage wore Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses while entering the courthouse. The judge issued a warning against using the glasses in court due to concerns about recording proceedings or using facial recognition on jurors. The incident became a visual metaphor for the trial's themes around surveillance and user data collection. Engadget provides further insights into the incident.

What are the potential damages if Meta loses the trial?

Damages could include compensation for the plaintiff's claimed harm and potentially punitive damages if the jury determines Meta acted with intentional disregard for the plaintiff's wellbeing. Significant damages could establish liability that affects dozens of similar pending lawsuits against Meta and other social media companies. BBC News explores the potential outcomes of the trial.

What does Meta's "conscious decision" to shift away from engagement-focused goals mean?

Zuckerberg testified that Meta made a deliberate choice to move away from engagement-focused metrics toward measuring usefulness. However, the timing of this shift is crucial—if it occurred recently or only after facing lawsuits, it suggests Meta only changed course under legal pressure rather than independent judgment that the strategy was harmful. PBS provides further insights into the timing question.

How does this trial connect to broader tech regulation efforts?

The trial is occurring alongside the EU's Digital Services Act implementation and proposed US state and federal social media regulations. The evidence presented and the verdict will inform how regulators approach social media company accountability. A finding against Meta strengthens the regulatory argument that companies deliberately exploit users and need strict oversight. CNBC explores the potential regulatory implications.

What is the role of Meta's internal mental health research in the trial?

Meta has conducted internal research showing that Instagram contributes to teenage anxiety, body image issues, and sleep disruption. If the company continued pursuing engagement-focused design despite knowing about these harms, that knowledge becomes evidence of deliberate harm rather than negligence, significantly strengthening the plaintiff's case. Engadget provides further insights into the internal research findings.

What happens if Meta wins the trial?

If Meta prevails, courts would signal that social media companies have broad latitude to design platforms for engagement as long as they can claim features serve legitimate purposes like usefulness or connection. This would set a higher bar for future lawsuits and weaken the regulatory case for restricting platform design practices. BBC News explores the implications of a potential Meta victory.

Key Takeaways

- Zuckerberg testified that Meta shifted focus from engagement metrics to platform usefulness, contradicting internal documents that show engagement was historically a core company goal. CNBC provides further analysis on the contradictions in Meta's defense.

- The trial represents a rare moment of legal accountability for a major tech CEO, with evidence and testimony now part of the public record. Engadget discusses the implications of the trial's public scrutiny.

- Meta's defense relies on the argument that usefulness naturally drives engagement, but the timing and documentation of a shift away from engagement metrics is legally crucial. BBC News explores the significance of the timing question.

- The verdict will set precedent for dozens of pending lawsuits against Meta and influence how regulators approach social media platform accountability. PBS provides further insights into the broader implications of the trial.

- European regulation through the Digital Services Act and proposed US legislation will likely cite this trial's evidence when determining how platforms must redesign their products. CNBC explores the potential regulatory outcomes.

Related Articles

- Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]

- Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Social Media Giants Face Historic Trials Over Teen Addiction & Mental Health [2025]

- European Commission Probes Shein's Addictive App Design and Illegal Products [2025]

- The Rise of Bating Apps and Digital Intimacy Communities [2025]

![Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Social Media Addiction: What Changed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/mark-zuckerberg-s-testimony-on-social-media-addiction-what-c/image-1-1771459843193.jpg)