Mark Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]

Lori Schott drove from Eastern Colorado to Los Angeles for one reason: she wanted Mark Zuckerberg to see her face.

Her daughter Annalee died by suicide at 18 in 2020. Before her death, Annalee filled journal entries with comparisons between her own looks and the curated images of other girls on Instagram. She measured herself against filters, against beauty standards, against an impossible standard created by an algorithm she didn't understand. Schott kept those journals. Now she carries them to a Los Angeles courthouse, where the most powerful tech CEO in the world is about to answer for the product that her daughter spent her final years consuming.

"I don't care if I had to hire a pack mule to get me here, I was going to be here," Schott told reporters outside the courthouse. "I want him to see my face, because my face is Anna's face."

This isn't just another lawsuit. This is a watershed moment for Big Tech accountability. For the first time in a major case, a parent bereaved by alleged social media harms will sit face-to-face with the founder and CEO of the company whose product, she believes, contributed to her daughter's death. Thousands of similar cases are waiting in the wings, watching this trial. Legislators are watching. The public is watching.

What happens in this Los Angeles courtroom over the next several weeks could reshape how social media companies design their products, how they talk about addiction, and how they balance profit against safety. It could also set precedents that echo through the tech industry for a decade.

This is the story of why that testimony matters, what it reveals about social media's design choices, and what comes next.

The Trial That Changed Everything

The bellwether trial isn't about a single user. It's about a pattern.

Meta and Google-owned YouTube stand accused of designing their products with full knowledge that they're addictive by design. The lawsuit alleges that both companies deliberately engineered their platforms to maximize engagement—the time users spend scrolling, tapping, and watching—regardless of the mental health consequences, particularly for minors.

This is different from previous social media litigation. Previous cases focused on specific harms: cyberbullying, self-harm content, predatory behavior. This case is broader. It asks a fundamental question: Did these companies knowingly design addictive products?

The parents sitting in the courtroom have personal answers to that question. Annalee Schott. Coco Arnold, who died of fentanyl poisoning at 17 after meeting a dealer on Instagram. These aren't hypothetical users. These are names. These are faces. These are lives.

The trial opened with testimony from Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri, who faced uncomfortable questions about Meta's internal research into how their products affect girls' mental health. He testified that using Instagram up to 16 hours daily wouldn't necessarily constitute addiction—a claim that made parents in the courtroom gasp audibly. Several had camped out overnight in the rain to ensure they'd have seats behind him as he testified.

Now Zuckerberg faces the same courtroom, the same parents, the same questions.

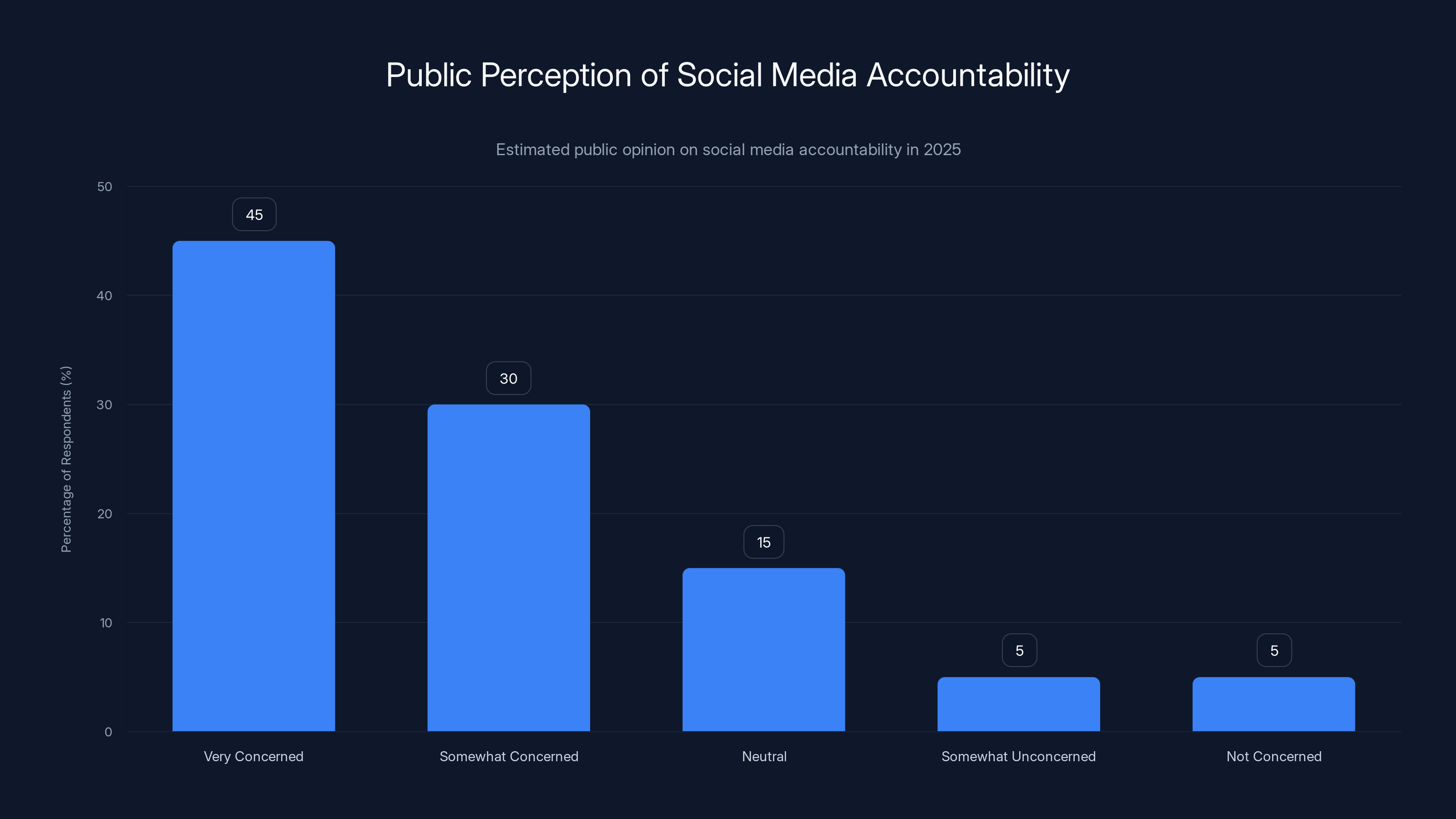

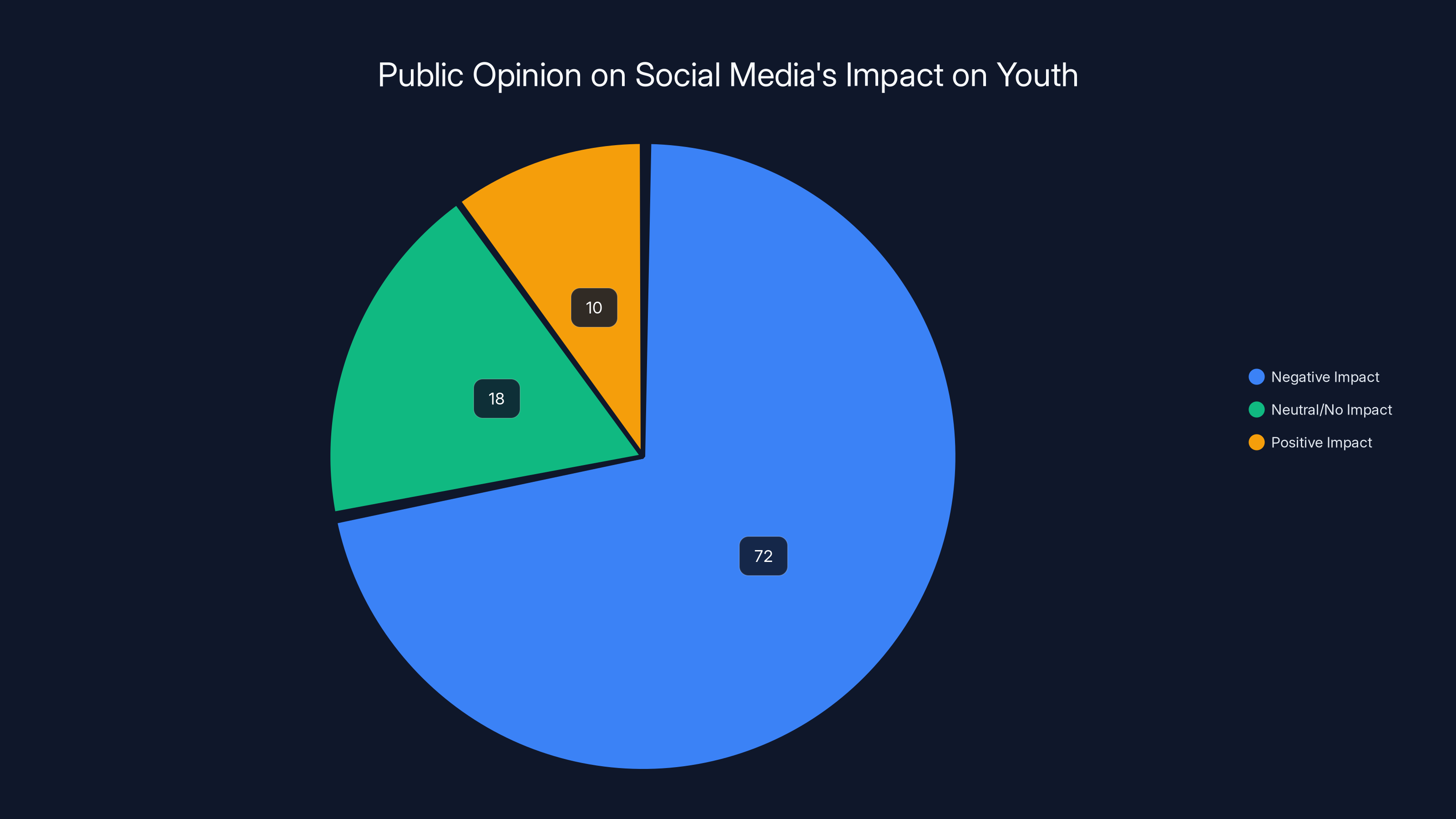

Estimated data suggests that a significant portion of the public is very concerned about social media accountability, reflecting the high stakes of the trial involving Mark Zuckerberg.

Understanding the Addictive Design Thesis

Let's be clear about what "addictive design" actually means in this legal context.

It's not that social media apps use algorithms. Every app uses algorithms. Netflix recommends shows. Spotify recommends songs. Amazon recommends products. That's not the allegation.

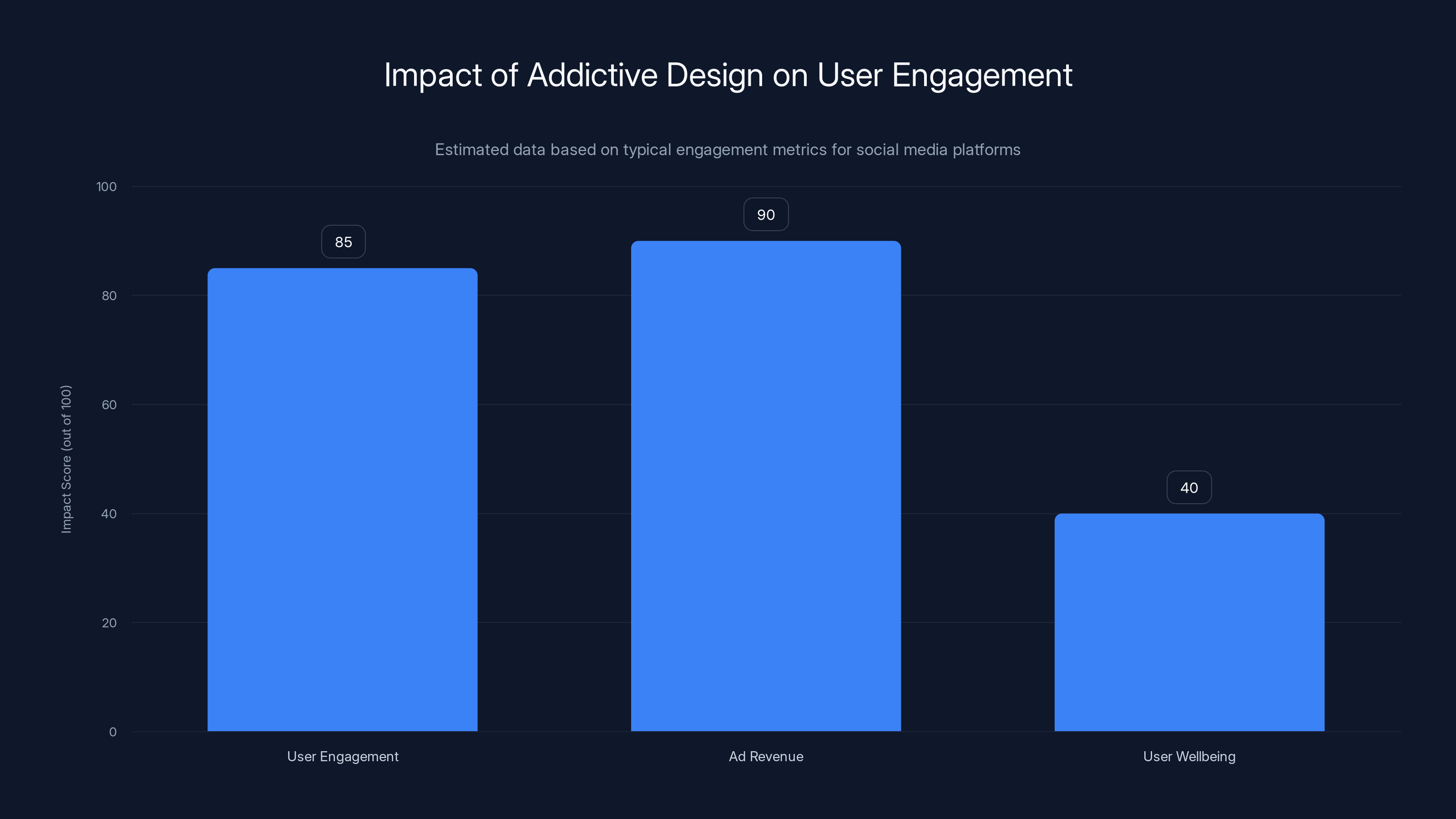

The allegation is more specific: Meta and Google deliberately designed their products using psychological principles and behavioral insights to maximize the time users spend on the platform, knowing this would increase engagement metrics and advertising revenue. The design choices allegedly prioritize user retention and engagement over user wellbeing.

Consider the mechanics. When you open Instagram, you're not greeted with chronological posts from people you follow. Instead, you're served a feed algorithmically optimized to keep you scrolling. Why? Because the longer you stay, the more ads you see. The more ads you see, the more revenue Meta generates.

But here's where it gets legally problematic: if Meta's internal research shows that minors are particularly vulnerable to these mechanics, and if they continued using them anyway, that's negligence at minimum.

Mosseri's testimony hinted at exactly this. He discussed documents about Meta's engagement metrics, profit incentives, and internal research about negative mental health effects—particularly on girls. The cognitive dissonance was striking. Meta knows the mental health costs. Meta continues the practices anyway.

The question Zuckerberg will face: Why?

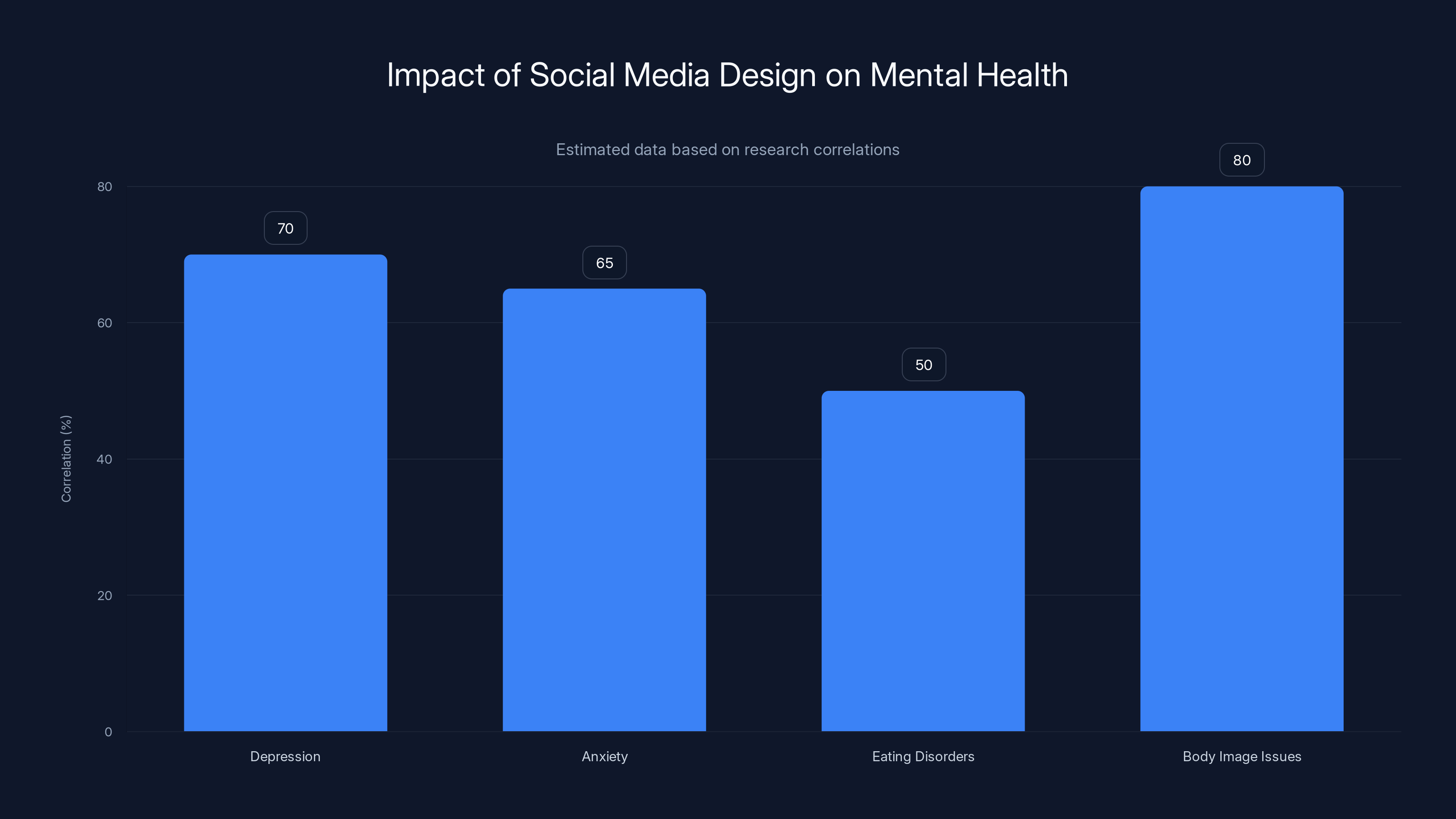

Estimated data suggests a high correlation between heavy social media use and various mental health issues, particularly among teenage girls.

What Zuckerberg's Internal Emails Reveal

One of the most damaging aspects of this trial involves Zuckerberg's own words.

Court documents include internal emails and messages where Zuckerberg discussed design choices. Some of these communications show the CEO thinking through trade-offs between safety and engagement. Others show decisions made in favor of engagement despite known safety risks.

The plaintiff's lawyers will almost certainly introduce these communications during Zuckerberg's testimony. They'll ask him to explain his reasoning. They'll ask whether he considered the mental health impact of these choices. They'll ask whether he knew minors were particularly at risk.

What makes this particularly powerful is the contrast between Zuckerberg's public statements and his private communications. Publicly, Meta positions itself as a company committed to user safety. Internally, the emails tell a different story—or at least that's what the plaintiff's lawyers will argue.

Zuckerberg has been deposed before in antitrust cases. But this trial is different. These aren't regulators asking about market dominance. These are bereaved parents asking about their children.

The Mental Health Evidence

Behind the legal arguments sits a growing body of research on social media and mental health.

Major studies have found correlations between heavy social media use and depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and body image issues—particularly among teenage girls. A landmark study found that girls who use Instagram for more than an hour daily have double the risk of depression and anxiety compared to those using it minimally.

But here's the critical distinction: correlation isn't causation, and the defense will emphasize this. Just because two things occur together doesn't mean one caused the other. Maybe depressed teens use social media more. Maybe anxious teens seek connection online. Maybe the relationship is bidirectional.

However, Meta's own research—disclosed during discovery—suggests internal acknowledgment of causation. Leaked documents show that Meta's researchers found negative mental health effects specifically linked to design features like the comparison metrics (likes, follower counts) and algorithm-driven feeds.

Zuckerberg will be asked about this research. He'll be asked why, if Meta knew about these effects, the company didn't change the design. He'll be asked whether profit was the reason.

Addictive design significantly boosts user engagement and ad revenue but negatively impacts user wellbeing. Estimated data.

The Addiction Definition Problem

Mosseri's testimony highlighted a crucial tension in this case: How do you legally define addiction to a non-chemical product?

Clinical addiction involves specific neurological and behavioral markers. Most definitions require substance dependence—meaning your body has physically adapted to a drug and experiences withdrawal when you stop. Addiction to social media doesn't have a clinical definition in the DSM-5, the diagnostic manual used by psychiatrists.

So when the plaintiff argues that Meta designed an addictive product, what does that actually mean? Is it about time spent? Compulsive use despite negative consequences? Preoccupation? Difficulty controlling use?

Mosseri sidestepped this by drawing a distinction between "addiction" and "problematic use." He argued that using Instagram 16 hours daily might not be addiction—it's just... heavy use. One parent in the courtroom later described this testimony as absurd. "Sixteen hours?" she said incredulously. "That's problematic by any definition."

But Mosseri's legalism has a point. If the law doesn't have a clear definition of addiction to social media, then Meta can argue their product doesn't cause it. Zuckerberg will likely use the same argument.

The plaintiff's lawyers will counter by pointing to behavioral patterns that mirror substance addiction: continued use despite negative consequences, difficulty controlling use, tolerance (needing more engagement to feel satisfied), and withdrawal symptoms when use is interrupted.

Zuckerberg will be asked whether Meta tracks these metrics. The answer, almost certainly, is yes.

The Algorithmic Amplification Question

One of the most damaging allegations involves how Meta's algorithm amplifies emotionally charged content.

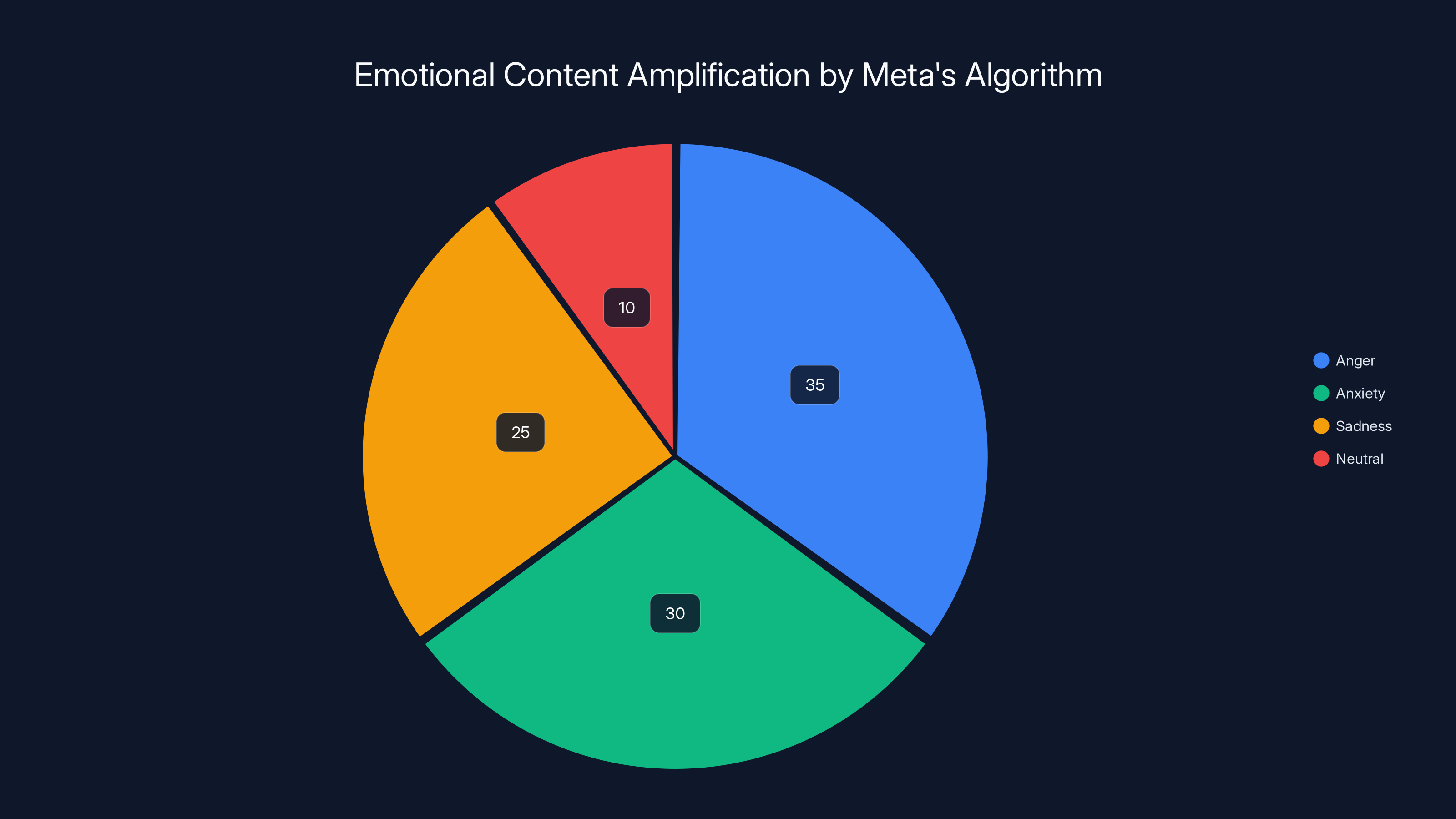

Research shows that content triggering strong emotions—particularly anger, anxiety, and sadness—gets more engagement than neutral content. Meta's algorithm, optimized for engagement, therefore amplifies emotionally negative content.

For a teenage girl struggling with body image, this has brutal consequences. The algorithm feeds her more content that triggers body comparison and anxiety. The more she engages with this content (even through angry reactions), the more it gets amplified. She becomes trapped in a feedback loop.

Meta's internal research acknowledged this mechanism. The documents disclosed during discovery show researchers explaining that their algorithm amplifies content that triggers negative emotions.

Zuckerberg will be asked whether he was aware of this. He'll be asked whether Meta considered changing the algorithm to prioritize user wellbeing over engagement. He'll be asked why they didn't.

The plaintiff's case turns on these design choices. They're arguing that Meta didn't accidentally create engagement-optimized products. They're arguing Meta deliberately built them this way, understood the mental health costs, and prioritized profit anyway.

Estimated data suggests that Meta's algorithm amplifies emotionally charged content, with anger and anxiety receiving the highest amplification compared to neutral content.

Testimony Strategy and Legal Dynamics

Zuckerberg's testimony will be unlike his previous public appearances.

When Zuckerberg testified before Congress about antitrust issues, he faced politicians who often didn't understand the technical details. He could fall back on technical explanations, deflections, and procedural arguments. This jury will be different. They're regular people. Parents, probably. Some who've dealt with teenagers and social media themselves.

The plaintiff's lawyers will likely take a different approach than lawmakers did. Rather than asking about market share and competitive dynamics, they'll focus on design choices and intent. They'll show documents. They'll ask for explanations that a jury can understand.

Zuckerberg's defense will likely emphasize several themes:

First, user choice. Meta didn't force anyone to use Instagram. Users could take breaks, set time limits, or stop using the app entirely. The company isn't responsible if people choose heavy use.

Second, benefits. Instagram connects people, lets them express themselves, creates community. For many, these benefits outweigh risks. Zuckerberg will likely emphasize the positive uses of the platform.

Third, causation uncertainty. Even if some users experience mental health issues while using Instagram, that doesn't prove Instagram caused those issues. Correlation isn't causation. The jury shouldn't assign fault without clear proof of causation.

The plaintiff's lawyers will counter each argument. They'll point to design choices that discourage taking breaks. They'll argue that connection and community can be achieved without addictive mechanics. They'll point to Meta's internal research acknowledging that their design choices cause harm.

The Filter and Beauty Standard Issue

Mosseri's testimony included an uncomfortable moment about Instagram filters.

The app offers filters that alter users' appearance—smoothing skin, enlarging eyes, changing facial structure. Meta's internal research found that these filters contribute to body image issues and eating disorders, particularly among young girls.

Internally, Meta apparently discussed restricting these filters or banning them outright. But they didn't. Zuckerberg will be asked why.

The answer is almost certainly that filters drive engagement. Users share photos with filters. Their friends react. They take more photos with filters. The engagement metrics increase. Advertising revenue increases.

Meta could have prioritized user mental health by eliminating filters that distort appearance. They didn't. That choice will hang in the courtroom when Zuckerberg testifies.

Parents in the gallery will likely have personal connections to this issue. Annalee Schott compared her own appearance to filtered images of other girls. How many teenage girls do the same thing every day? How many develop eating disorders partly because they're comparing their real faces to filtered versions of other people's faces?

Zuckerberg will have to answer for that design choice.

A recent survey shows that 72% of Americans believe social media negatively impacts teenagers' mental health. This perception may increase following Zuckerberg's testimony. Estimated data.

What Previous Tech Trials Tell Us

This trial doesn't exist in a vacuum. There are precedents.

The tobacco trials of the 1990s established a template for holding companies accountable when internal documents showed they knew about harms and continued harmful practices anyway. Tobacco companies knew their products were addictive and deadly. They researched this. They documented it internally. And they continued marketing to vulnerable populations anyway.

The courts held them accountable.

There are similarities here, though with important differences. Tobacco companies were marketing a chemical product with direct physiological effects. Social media is different. But the pattern is similar: internal knowledge of harm, continued harmful practices, prioritization of profit over safety.

Other tech trials have been less successful at holding companies accountable. The Facebook antitrust case struggled in some jurisdictions because proving market harm required technical expertise that juries didn't always have. But this trial doesn't require that expertise. It requires asking a jury: Did this company deliberately design an addictive product for children? Did they know it would cause harm? Did they prioritize profit anyway?

Those are questions ordinary people can answer.

The Ripple Effect Across Tech

Whether Zuckerberg wins or loses, this testimony will reshape tech.

If the plaintiff prevails, the implications are enormous. Every social media company, every app that uses engagement-optimized algorithms, every product designed to maximize time-on-platform will face scrutiny. The liability exposure is staggering. We're not talking about settlements in the hundreds of millions. We're talking about cases that could cost billions.

But even if Zuckerberg's team wins, they lose. The testimony will be public. The documents will be public. Zuckerberg's explanations will be scrutinized by legislators, regulators, and other tech executives.

That scrutiny has already begun. The trial has renewed calls for legislation regulating social media. The UK, Australia, and European countries are all considering or implementing new regulations. Even in America, previously gridlocked legislatures are moving toward bipartisan bills targeting social media's impact on minors.

Zuckerberg's testimony will inform that legislation. If he claims Meta cares about user wellbeing while documents show the opposite, legislators will notice. If he argues that users choose to spend 16 hours daily on Instagram, they'll find that unconvincing.

The testimony matters legally, but it matters even more politically.

The Parent's Perspective and Moral Dimension

What makes this trial different from other tech litigation is the presence of bereaved parents.

These aren't abstract stakeholders. They're not even primarily seeking financial damages (though they'll receive them if they win). They're there because they want accountability. They want the person responsible for the product that harmed their children to acknowledge that harm.

Schott's insistence on being in the courtroom—"I want him to see my face, because my face is Anna's face"—cuts through all the legal complexity. This is about a parent who lost a child.

Zuckerberg is a parent too. That fact will hang in the air. When he's testifying, he'll be looking at faces of parents who lost their children. How does he explain that? How does he explain prioritizing engagement over safety to parents who believe that choice killed their kids?

This is where legal strategy meets human reality. Zuckerberg can't hide behind technical explanations or legalism. He's facing the human cost of his company's design choices.

What Happens After Testimony

Zuckerberg's testimony is one part of a weeks-long trial.

The plaintiff will present expert witnesses on addiction, on adolescent psychology, on how algorithms work. Meta will present its own experts. Both sides will bring economists to discuss damages. The jury will ultimately decide whether Meta bears responsibility for the alleged harms.

But the legal outcome is almost secondary to the cultural impact. If videos of Zuckerberg's testimony circulate widely—and they will—the public narrative about social media will shift.

We're already seeing this shift. Public opinion on social media's impact on youth has turned negative. A recent survey found that 86% of Americans want Meta and Google held accountable for the social media addiction crisis. That number will likely increase after Zuckerberg's testimony if he comes across as evasive or prioritizes profit over safety.

Regulators notice these shifts. Congress notices. State legislatures notice. The political pressure on tech companies is building.

Zuckerberg's testimony could accelerate that pressure significantly.

The Bigger Question About Tech Accountability

Why does this trial matter beyond Meta?

Because it asks a question that goes to the heart of how technology companies operate: Should they be held accountable when they knowingly design products that harm users?

Right now, tech companies operate with remarkable freedom. The Section 230 protections shield them from liability for user-generated content. Antitrust law hasn't caught up to platform dynamics. Most regulation lags years behind technological change.

So companies can design products in ways that prioritize profit over safety, knowing that legal liability is limited. That creates perverse incentives. Why optimize for user wellbeing when you can optimize for engagement and profit?

This trial is testing whether courts will intervene. If they do, it changes the incentive structure for every tech company. If they don't, it signals that designing addictive products is acceptable as long as you're not breaking existing laws.

Zuckerberg's testimony will be crucial in answering that question.

Expert Predictions and Legal Analysis

Trial lawyers watching this case have varying predictions.

Some believe the plaintiff has a strong case. Meta's internal documents are damaging. The connection between algorithm design and mental health outcomes is increasingly well-documented. And most importantly, the jury pool is sympathetic—these are everyday people who understand social media's impact because they've seen it with their own kids.

Others believe Meta has advantages. The law isn't entirely clear on liability for non-chemical addiction. Meta can argue that users choose their consumption levels. The evidence of direct causation, while suggestive, isn't definitive by legal standards.

Most experts agree that the outcome will turn on Zuckerberg's testimony. If he comes across as callous or dismissive of mental health concerns, the jury will be more likely to rule against Meta. If he comes across as genuinely thoughtful about the trade-offs between engagement and wellbeing, he has a better chance.

But here's what's almost certain: Zuckerberg will be uncomfortable. These aren't the sympathetic questions he gets from tech journalists or friendly forums. These are adversarial questions from lawyers representing bereaved parents. And whatever he says will be scrutinized for authenticity.

The Path Forward for Social Media

If this trial results in major damages or new legal standards, what comes next?

We might see significant changes to how apps are designed. Engagement metrics might be replaced with wellbeing metrics. Algorithms might be tuned to prioritize user safety over time-on-platform. Age verification might become more rigorous, with special protections for minors.

We might also see legislation. Congress has been considering various bills targeting social media's impact on youth. A plaintiff victory in this trial would provide political momentum for those bills.

Meta would almost certainly appeal a negative ruling. The case could reach appellate courts and potentially the Supreme Court. The legal questions—about addiction to digital products, about corporate liability for user choices, about the balance between profit and safety—will take years to fully resolve.

But the immediate impact of Zuckerberg's testimony will be felt quickly. His words will be quoted in legislative hearings. They'll be analyzed by regulators. They'll inform how other companies design their products.

That's why his testimony matters so much. It's not just about this case. It's about the future of technology design.

The Human Element

There's something powerful about a parent insisting that her presence matters.

"I want him to see my face, because my face is Anna's face."

That statement cuts through all the complexity of algorithmic design, engagement metrics, and corporate structure. It's about accountability. It's about forcing a CEO to see the human cost of his company's decisions.

Schott will be watching Zuckerberg as he testifies. She wants him to see her grief. She wants him to understand that the metrics he cares about—engagement, retention, daily active users—correspond to real people with real lives.

Whether Zuckerberg's presence in that courtroom actually changes anything legally remains to be seen. But there's something important happening regardless. A parent is holding a tech CEO accountable in the most direct way possible: by making him look her in the eye while she describes what his company's product did to her daughter.

That's not how most corporate accountability happens. It's direct. It's personal. It's uncomfortable.

It's also, maybe, exactly what's needed.

FAQ

What is the social media addiction trial about?

The bellwether trial in Los Angeles is examining whether Meta and Google-owned YouTube deliberately designed their platforms to be addictive, particularly for minors. The case specifically alleges that both companies engineered their products to maximize engagement despite knowing the mental health consequences, prioritizing profit over user safety. The trial will set precedent for thousands of similar lawsuits pending against social media companies.

Why is Mark Zuckerberg's testimony so important?

As Meta's founder and CEO, Zuckerberg is being called to account for major design decisions at the company level. His testimony follows Instagram CEO Adam Mosseri's uncomfortable questioning about engagement metrics and mental health research. Zuckerberg's statements will likely be referenced in future trials and legislative hearings, making his testimony one of the most consequential moments in tech accountability litigation to date.

What mental health evidence supports the case against Meta?

Research shows correlations between heavy social media use and depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and body image issues, particularly among teenage girls. Meta's own internal research, disclosed during court discovery, allegedly acknowledged these negative effects and linked them directly to design features like engagement metrics and algorithm-driven feeds that prioritize emotionally charged content.

What design choices are being questioned in the trial?

The trial focuses on several specific design decisions: the use of algorithms optimized for engagement rather than chronological feeds, appearance-altering filters that contribute to body image issues, comparison metrics like likes and follower counts, and the amplification of emotionally charged content. Each choice allegedly prioritizes user retention and advertising revenue over user wellbeing.

How could this trial impact other tech companies?

If the plaintiff prevails, the legal liability exposure extends to every company using engagement-optimized algorithms. This includes streaming services, video platforms, shopping apps, and any product designed to maximize time-on-platform. Even if Meta wins, the public testimony and disclosed documents will inform new legislation and regulatory scrutiny across the tech industry.

What legal standard applies to social media addiction?

Unlike substance addiction, which has clinical definitions in medical literature, social media addiction isn't formally defined in the DSM-5. The trial will help courts determine what legal definition should apply. The plaintiff's lawyers will likely point to behavioral patterns mirroring substance addiction: continued use despite negative consequences, difficulty controlling use, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms. Meta's defense will likely emphasize the lack of a clear clinical standard.

What does "addictive design" actually mean legally?

In this context, addictive design means deliberately engineering products using psychological principles and behavioral insights to maximize user engagement and time-on-platform, knowing this creates harmful effects. It's not simply using algorithms to recommend content—it's specifically designing those algorithms to exploit psychological vulnerabilities, particularly in minors, for profit maximization.

How might this trial lead to new legislation?

Previously gridlocked legislatures are moving toward bipartisan bills targeting social media's impact on minors. Zuckerberg's testimony will be public and scrutinized by lawmakers. If he appears evasive about the trade-offs between profit and safety, it will provide political momentum for stronger regulation. The UK, Australia, and European countries are already implementing stricter regulations that may influence American policy.

Key Takeaways

- Mark Zuckerberg's testimony represents the first major moment where a bereaved parent confronts a tech CEO directly over alleged harms caused by platform design

- Meta's internal documents show the company knew about mental health impacts of their algorithm and design choices, yet prioritized engagement and profit anyway

- The trial focuses not on individual bad actors but on deliberate design choices that allegedly exploit psychological vulnerabilities in minors for revenue generation

- If the plaintiff prevails, the liability exposure extends across the entire tech industry, affecting any company using engagement-optimized algorithms

- Zuckerberg's testimony will inform future legislation targeting social media's impact on youth, with bipartisan momentum building for regulatory action

- The trial sets precedent comparable to tobacco litigation, establishing that companies cannot knowingly design harmful products without legal accountability

Related Articles

- Meta's Child Safety Crisis: What the New Mexico Trial Reveals [2025]

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]

- Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: What You Need to Know [2025]

- DOJ Antitrust Chief's Surprise Exit Weeks Before Live Nation Trial [2025]

![Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/zuckerberg-takes-stand-in-social-media-trial-what-s-at-stake/image-1-1771419910350.jpg)