Introduction: When Success Stories Turn Into Cautionary Tales

It happened again. Another promising startup founder made the Forbes 30 Under 30 list only to face federal indictment months later. This time, it's Gökçe Güven, a 26-year-old Turkish national and CEO of fintech startup Kalder, charged with securities fraud, wire fraud, visa fraud, and aggravated identity theft. The narrative feels all too familiar at this point.

But here's what makes this case different, and frankly, what should concern every startup founder, investor, and aspiring entrepreneur: the specificity of the alleged fraud reveals systemic failures in how we evaluate new ventures. We're not talking about ambitious projections that missed the mark. We're talking about fabricated client lists, double sets of financial books, and forged documents. This isn't a failure of execution—it's a deliberate deception orchestrated at the highest level.

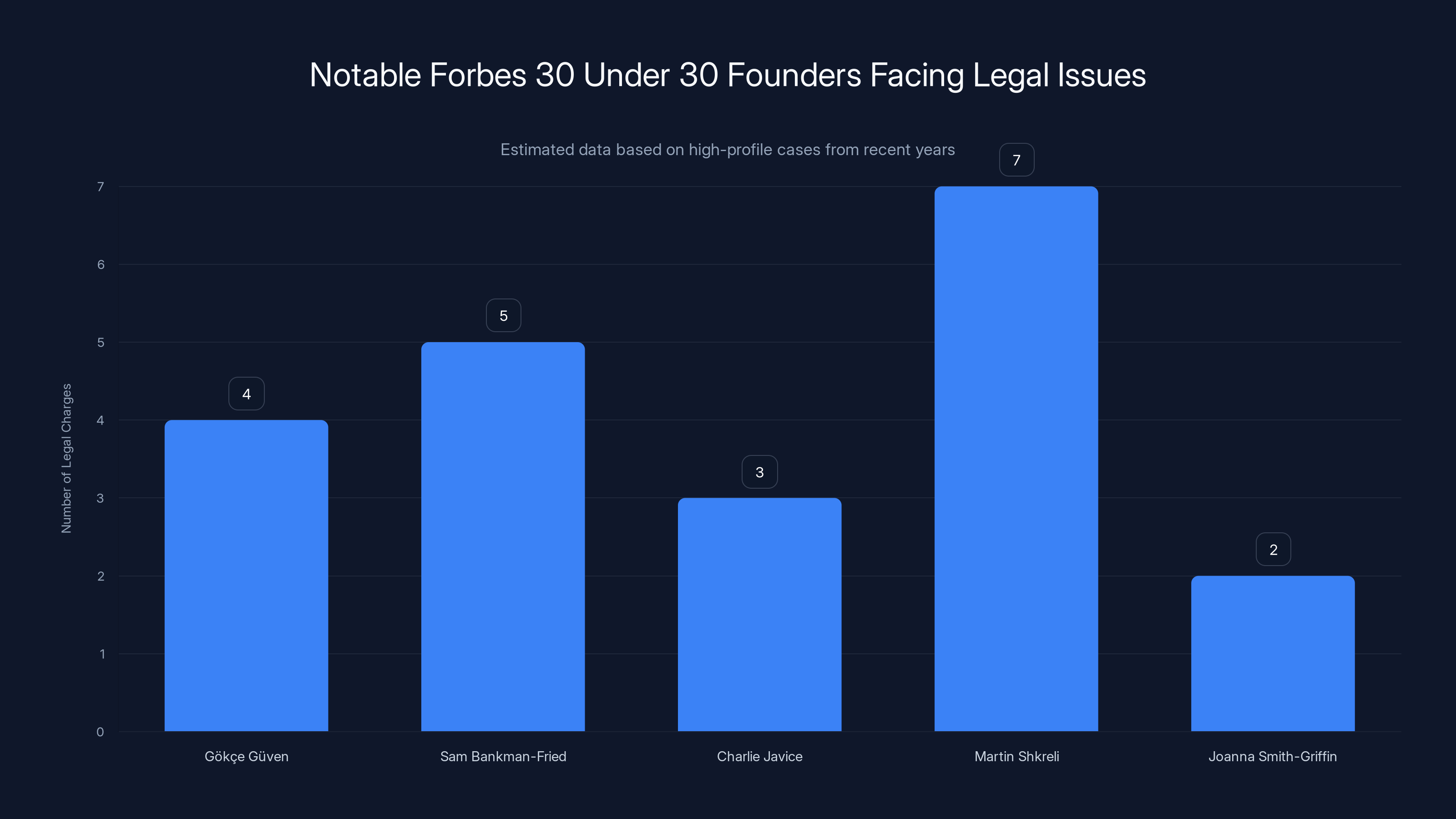

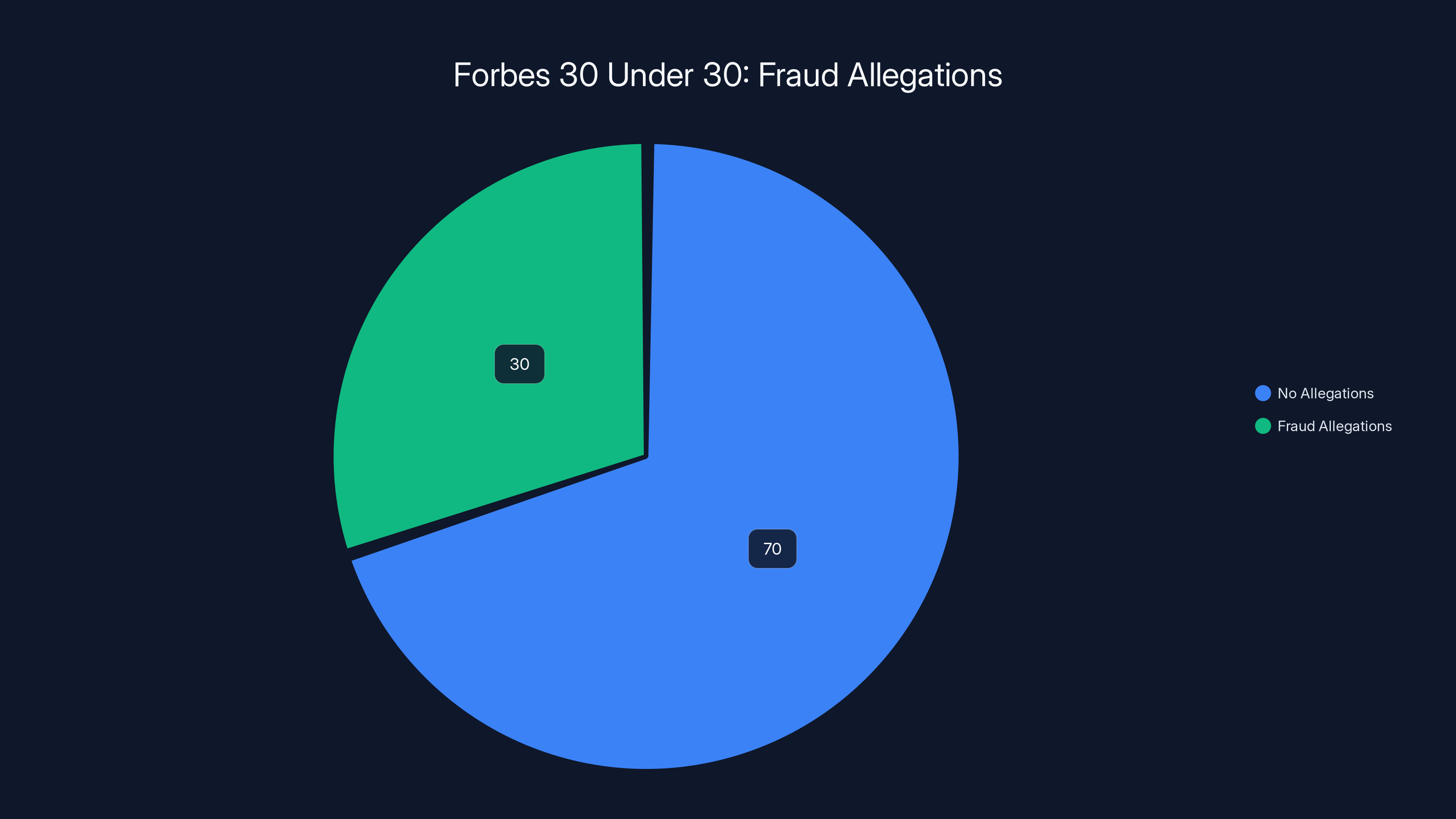

The Kalder case matters because it exposes something uncomfortable about the startup ecosystem. The same environment that celebrates youth and disruption sometimes celebrates fraudsters alongside legitimate innovators. We've seen this pattern with FTX's Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced "crypto savior" who also made Forbes 30 Under 30 before collapsing under the weight of his alleged scheme. We've watched it unfold with Frank CEO Charlie Javice, whose company pivoted from fintech to fraud in the eyes of federal prosecutors. The list extends further back to Martin Shkreli, the infamous "pharma bro," and includes Joanna Smith-Griffin of All Here Education. Forbes 30 Under 30 has inadvertently become a who's who of prosecuted founders.

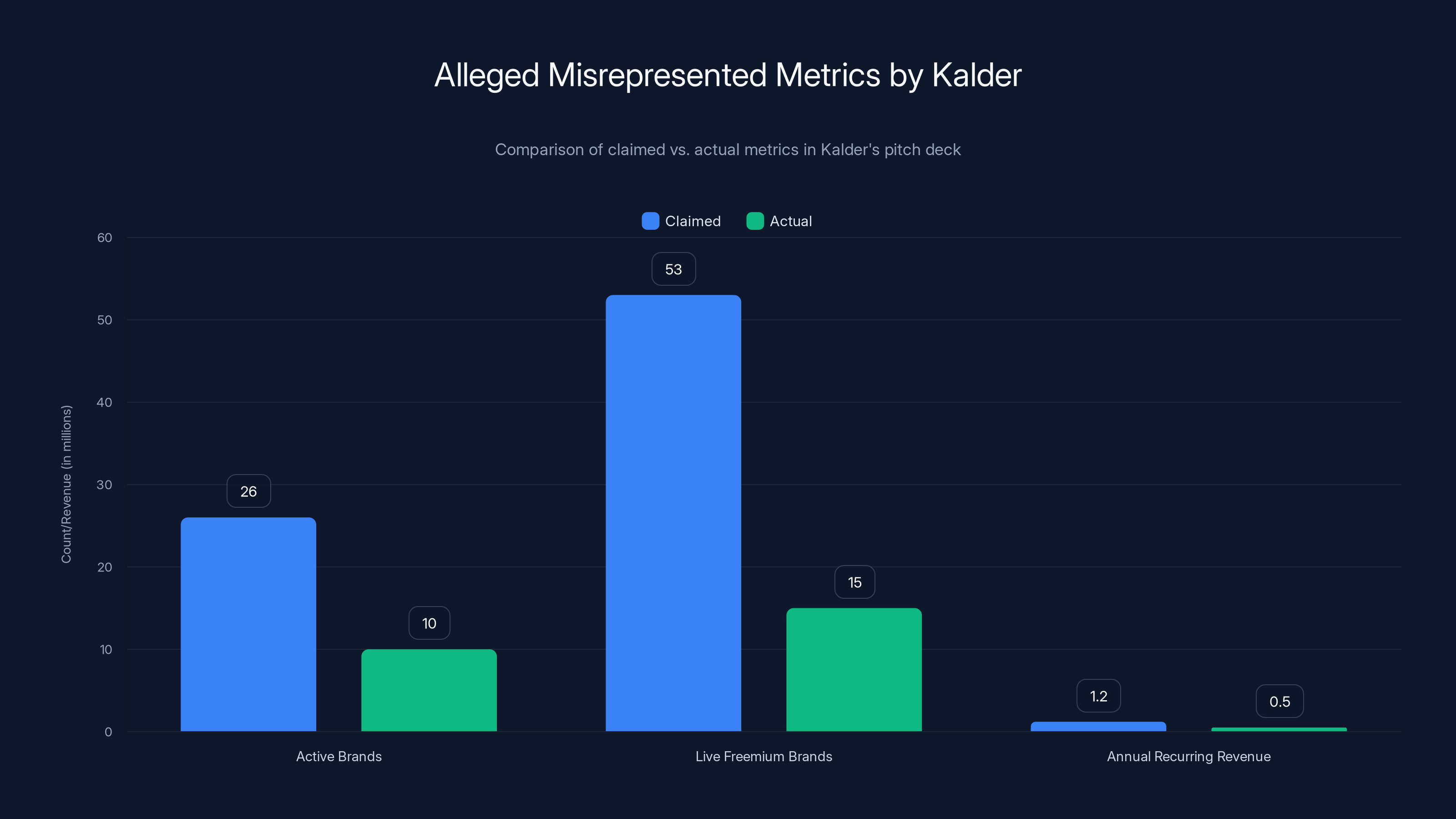

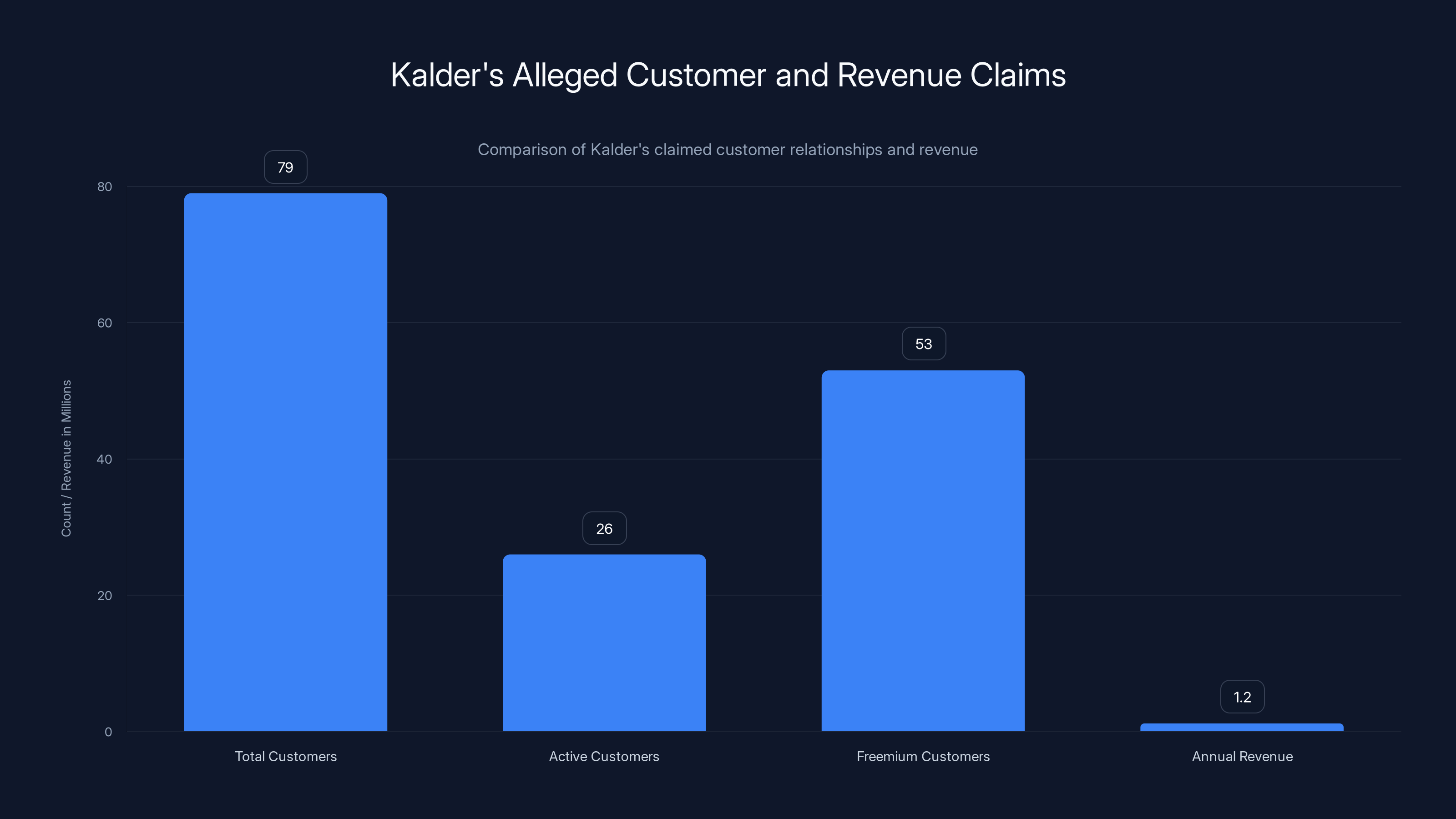

What's particularly striking about Güven's case is how the alleged fraud played out. During Kalder's seed round in April 2024, she allegedly presented investors with a pitch deck so riddled with false information that it reads like a masterclass in what not to do. The deck claimed 26 brands were actively using Kalder and another 53 were in "live freemium." The reality? Many of these companies hadn't signed any agreements at all. Some were barely in pilot programs, heavily discounted to the point of being non-binding relationships. Others existed only on paper.

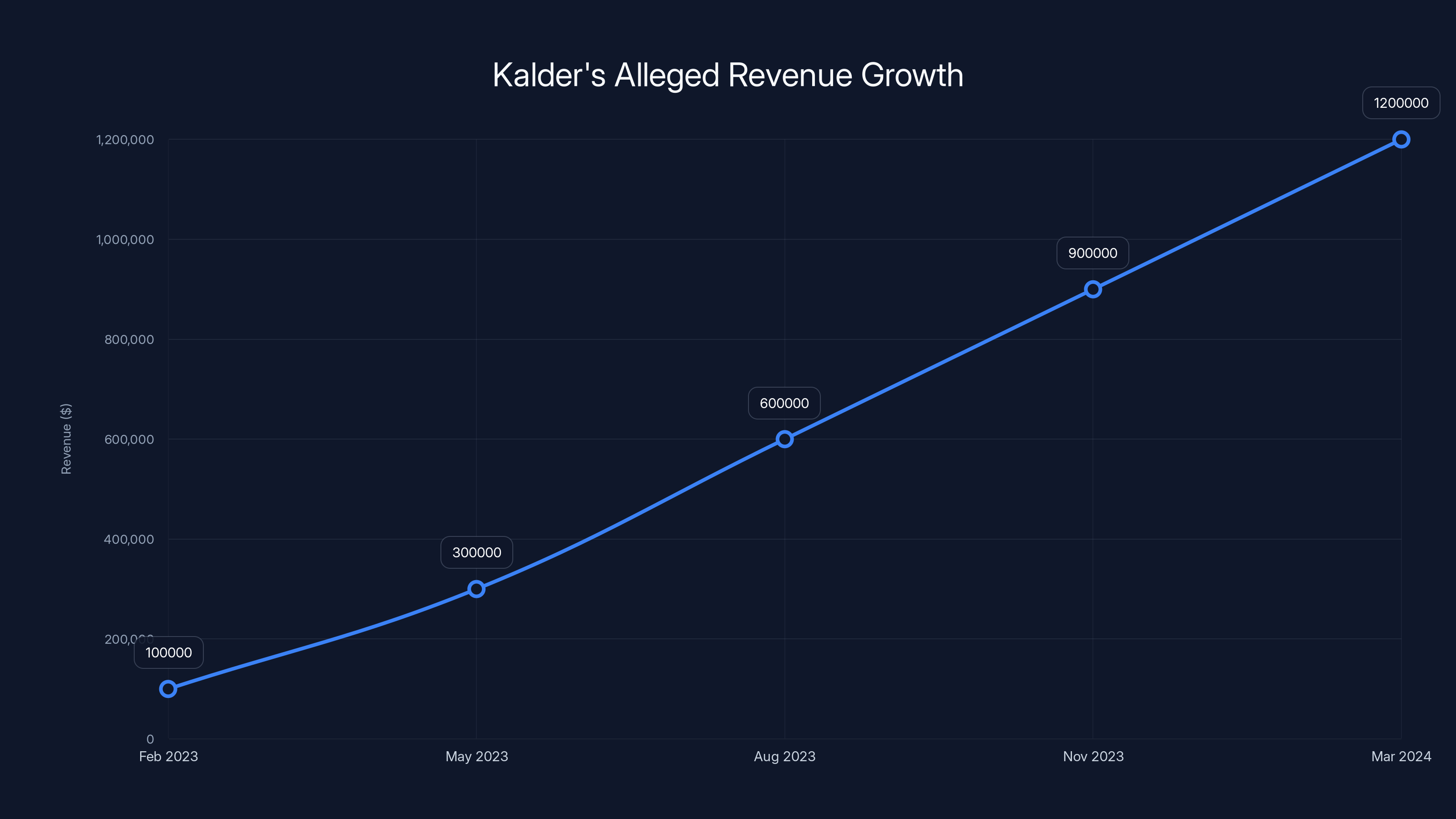

The financial misrepresentation was equally egregious. Kalder's pitch deck allegedly claimed the startup had grown its recurring revenue from zero to $1.2 million annually by March 2024. That's a staggering growth trajectory. In reality, the company hadn't come close to those numbers. And to hide the gap between projected and actual performance, prosecutors say Güven maintained two separate sets of financial books—one honest, one inflated for investor consumption.

The visa fraud component adds another layer. Güven allegedly used fraudulent claims about Kalder's success to obtain an EB-1 visa, a category reserved for individuals demonstrating "extraordinary ability" in their fields. It's the visa category that tech executives, artists, and genuinely exceptional individuals use to establish residence in the United States. Using it fraudulently isn't just a violation of immigration law—it's an insult to the system itself.

Raising $7 million from investors who believed in false information represents more than just criminal activity. It represents a breakdown in every checkpoint that should theoretically prevent this from happening. Where was the due diligence? How did major venture capital firms miss these red flags? Why did the Forbes selection process not surface concerns? Most importantly, what does this tell us about the venture ecosystem's ability to spot fraud before people's life savings disappear?

This article isn't about condemning a 26-year-old or assuming guilt before trial. It's about understanding what went wrong, recognizing the warning signs that investors and founders should watch for, and fundamentally reconsidering how we evaluate emerging businesses. Because the next person affected by startup fraud might be you, an investor in your fund, or someone at your company.

TL; DR

- Gökçe Güven, Kalder CEO, faces federal charges for allegedly raising $7 million with fabricated client lists and inflated revenue claims

- The case reveals systematic failures in venture due diligence, with investors missing obvious red flags about company metrics and customer relationships

- Double bookkeeping and forged documents suggest deliberate fraud, not honest mistakes or overly optimistic projections

- Forbes 30 Under 30 has become an unintended red flag itself, with multiple founders from the list facing federal charges for fraud

- Startups and investors need stronger verification processes, independent audits, and accountability mechanisms to prevent future cases

Kalder allegedly misrepresented its metrics, claiming more active brands and higher revenue than actual. Estimated data based on case details.

The Kalder Case: What Happened and Why It Matters

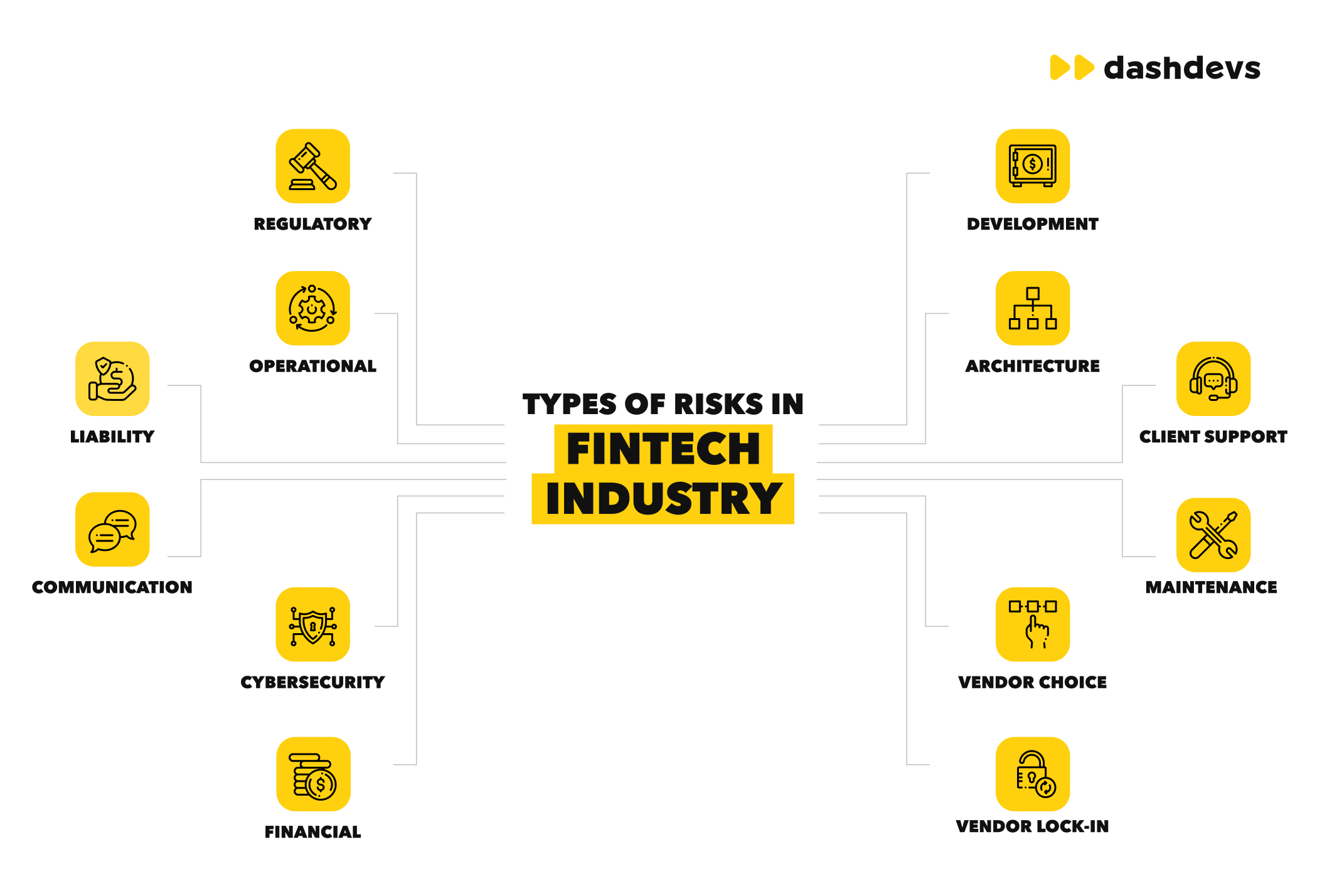

Kalder sounds like a legitimate idea on paper. A fintech startup that helps companies monetize customer rewards programs through affiliate partnerships. The tagline? "Turn Your Rewards into [a] Revenue Engine." It's buzzworthy. It's scalable in theory. It solves a real problem for companies managing loyalty programs.

The company launched in 2022. By early 2024, it had attracted attention from several prominent venture capital firms and appeared to be generating real traction. Major brands seemed interested. The International Air Transport Association, representing most of the world's airlines, allegedly worked with Kalder. Godiva, the luxury chocolatier, appeared on client lists. These aren't small partnerships—they're the kind of relationships that venture investors actually care about.

Then in April 2024, Kalder entered its seed round. The goal was to raise capital to scale the operation, expand the team, and accelerate product development. Nothing unusual there. Thousands of startups run seed rounds every month. Most succeed in raising capital. Some fail to find investors. A small percentage, tragically, commit fraud in the process.

Güven allegedly presented a pitch deck that painted Kalder as already succeeding dramatically. The numbers suggested explosive growth. Recurring revenue had climbed month over month since February 2023 and reached $1.2 million annually by March 2024. For a two-year-old startup, that's remarkable. For a fintech company in a crowded market, it's the kind of trajectory that makes investors lean forward in their chairs.

Over a dozen investors apparently believed the story. They committed $7 million to Kalder's future. That's real money. That's life-changing money for employees who received equity. That's money that came from limited partners, pension funds, and individuals who trusted the venture capital firm's diligence process.

Except the story wasn't true. Or at least, it wasn't what investors thought it was. The alleged fraud came in multiple forms. The client list was partially fabricated. Companies listed as "using Kalder" hadn't actually implemented the system. Companies listed as in "live freemium" were in temporary pilot programs with such deep discounts that they barely qualified as commitments. Some companies on the list had no agreement with Kalder whatsoever—not even for free services.

The revenue claims were equally problematic. The $1.2 million recurring revenue figure wasn't just optimistic. Prosecutors allege it was invented. Kalder hadn't come close to that number. To maintain the fiction, Güven allegedly kept two sets of books. One reflected the actual, much lower financial performance. One reflected the inflated numbers presented to investors. This isn't a gray area. This isn't a founder genuinely believing in her product but being overly optimistic about uptake. This is deliberate, documented misrepresentation.

The visa fraud component reveals something darker still. Güven allegedly used false information about Kalder's success to obtain an EB-1 visa, the extraordinary ability category. EB-1 visas are supposed to be reserved for individuals with demonstrated excellence in their fields. Using fraudulent claims about a company's success to obtain such a visa isn't just an immigration violation. It's an abuse of a system designed to attract genuinely exceptional talent to the United States.

When the Department of Justice announced the indictment, they laid out the evidence methodically. The pitch deck claims. The actual company performance. The two sets of books. The visa fraud allegation. It reads like a textbook case of entrepreneurial fraud, the kind that business schools teach as a cautionary tale about what not to do.

The timing matters too. Güven had just made Forbes 30 Under 30. She had accomplished something that many entrepreneurs spend their entire careers trying to achieve. She had validation from one of the world's most prestigious publications. She was being celebrated as a representative of a new generation of startup leaders. And apparently, during that exact moment, she was committing federal crimes.

Estimated data shows a pattern of legal issues among Forbes 30 Under 30 founders, highlighting systemic risks in the startup ecosystem.

The Forbes 30 Under 30 Pattern: Why Success Lists Have Become Fraud Indicators

Let's talk about the elephant in the room. Forbes 30 Under 30 has become unexpectedly infamous. Not because the publication is bad at vetting. Not because they're systematically celebrating fraudsters. But because success, when it's celebrated this publicly and this early, apparently attracts a specific type of person.

Sam Bankman-Fried is the most obvious example. FTX was the company that would "change everything." He was the young crypto genius who understood what nobody else understood. He made Forbes 30 Under 30. Then FTX collapsed, and it became clear that the entire empire was built on lies. Billions of dollars from customers and investors just vanished. Bankman-Fried was convicted of fraud and conspiracy.

Charlie Javice created Frank, a student loan refinancing platform with a clever interface and genuine appeal to the market. Frank attracted major investment. Javice made Forbes 30 Under 30. Then the federal government sued, alleging that Javice had misrepresented how many students used the app and how much money the company had raised. The case eventually settled, but the damage was done.

Martin Shkreli, the infamous "pharma bro," made Forbes 30 Under 30 for his work in healthcare. He's now serving time in federal prison for securities fraud and conspiracy related to his pharmaceutical company.

Joanna Smith-Griffin founded All Here Education, an AI startup focused on helping students. She also made the list. She also faced fraud allegations related to how she represented the company's traction and technology.

The pattern is so consistent that it's worth asking: what does Forbes 30 Under 30 actually measure? If the list is celebrating innovation and promise, it seems to occasionally celebrate something else instead. Gökçe Güven's inclusion in the 2024 list followed this exact trajectory. She made the list. Within months, she faced federal charges.

One interpretation is that some people who commit fraud are also ambitious enough to pursue Forbes 30 Under 30. Ambition itself isn't the problem. Most ambitious people are honest. But the combination of ambition, access to capital, and willingness to deceive creates a particularly dangerous archetype.

Another interpretation is that the venture ecosystem's speed and emphasis on growth-at-all-costs creates conditions where fraud becomes tempting. If your pitch matters more than your product, if your story matters more than your metrics, then people who are good at telling stories have an advantage. And some people who are good at telling stories are also good at lying.

A third interpretation involves the selection bias of success itself. Getting on Forbes 30 Under 30 means you've already attracted significant attention. You've either built something real or convinced enough people that something real is happening. The publication can't easily distinguish between the two. By the time evidence of fraud emerges, the person is already on the list, already celebrated, already have convinced investors to commit capital.

Regardless of which interpretation is correct, the pattern is undeniable. And it should concern anyone evaluating startups or considering founding one.

What's particularly interesting is that the Kalder case seems more deliberate than some previous fraud cases. Bankman-Fried's fraud allegedly emerged from a complex web of corporate structures and poor accounting. Shkreli's fraud involved misleading investors about the direction of pharmaceutical development. But Kalder? The allegations suggest something simpler and more intentional: Güven allegedly took a legitimate company idea, claimed it had far more traction than it actually had, maintained two sets of financial records, and used those false claims to raise millions of dollars.

This is fraud by committee. It's not a founder overestimating market size or being too optimistic about adoption. It's deliberate misrepresentation, implemented through documents, pitch decks, and falsified books. It's the kind of fraud that requires planning, execution, and compartmentalization.

Red Flags Every Investor Should Have Spotted

Here's what's frustrating about the Kalder case: the red flags were apparently obvious. Not in hindsight, but at the time. The kind of red flags that professional investors are trained to identify.

Let's start with the client list. Kalder allegedly claimed 26 brands were actively using the platform and 53 were in "live freemium." That's 79 customer relationships for a two-year-old startup. In B2B SaaS, especially in fintech, that would be an exceptional achievement. Companies like Stripe, Twilio, and Plaid took years to build that kind of customer diversity. For Kalder to achieve it in two years would be remarkable.

But remarkable should trigger verification. When a startup claims an unusually high number of customers for its stage, due diligence should include contacting customers directly. Not all of them, but a representative sample. Asking questions like: How long have you been using Kalder? What is the scope of your implementation? How much have you spent? What results are you seeing? These aren't trick questions. They're standard due diligence.

If an investor had contacted even three of the 79 alleged customers, they would have discovered the problem. Some of these companies had never signed agreements. Some were in pilot programs so temporary and lightly used that they barely qualified as implementations. This isn't something you can hide from a phone call.

The revenue claims should have triggered similar verification. Kalder allegedly claimed $1.2 million in annual recurring revenue by March 2024, with consistent month-over-month growth since February 2023. For a company at Kalder's stage, that level of recurring revenue is legitimately impressive. But it should also be verified.

When a startup claims recurring revenue, investors should request:

- Detailed breakdown of the revenue by customer

- Written confirmation from customers about payment amounts and frequency

- Bank statements showing actual revenue deposits

- Tax filings reflecting the claimed revenue

- Financial statements prepared by an accountant

These aren't unusual requests. They're standard due diligence for seed-stage companies claiming seven-figure recurring revenue. If Güven's team had been honest, they could have provided documentation. If they couldn't, that's a red flag. If they provided two different sets of documentation, that's beyond a red flag. That's confirmation of fraud.

The fact that Güven allegedly maintained two sets of books is perhaps the most damning evidence. In legitimate companies, there's one set of books. That's it. A CFO, an accountant, a bookkeeper—they all work from the same underlying financial reality. If financial statements differ from what the company's leadership is presenting to investors, something is catastrophically wrong.

Double bookkeeping requires planning and execution. It requires maintaining two separate accounting systems, ensuring that reports are distributed to the right people, and verifying that the numbers in each set of books tell internally consistent stories. This isn't something that happens accidentally. This isn't a result of poor accounting practices. This is deliberate fraud.

A competent due diligence process should include an audit or at minimum a review of the company's accounting practices. Questions like: Who has access to the general ledger? Who approves transactions? Who reconciles accounts? How are financial statements prepared? These questions would reveal inconsistencies if someone was maintaining multiple sets of records.

The visa fraud component reveals another verification failure. Güven allegedly used fraudulent information about Kalder to obtain an EB-1 visa. EB-1 visas require demonstrating extraordinary ability in your field. The government apparently discovered that the information used to support the visa application included false claims about Kalder's success and Güven's personal achievements.

This should have been discoverable through basic background checks. Before investing in a founder who is not a U.S. citizen, investors should verify their immigration status and understand how they obtained their visa. If there are inconsistencies between what the visa application claimed and what the startup actually achieved, that's a massive red flag.

None of these red flags were hidden. None required extraordinary investigative work. They required doing basic due diligence correctly. They required calling customers. They required reviewing financial documentation. They required asking hard questions and verifying answers.

The venture capital firms that invested in Kalder are presumably sophisticated. They've evaluated hundreds of startups. They have processes. They have checklists. Either those processes failed, or they didn't execute them in Kalder's case. Either way, it's a failure.

Kalder's pitch deck suggested a rapid increase in recurring revenue, reaching $1.2 million annually by March 2024. Estimated data based on narrative.

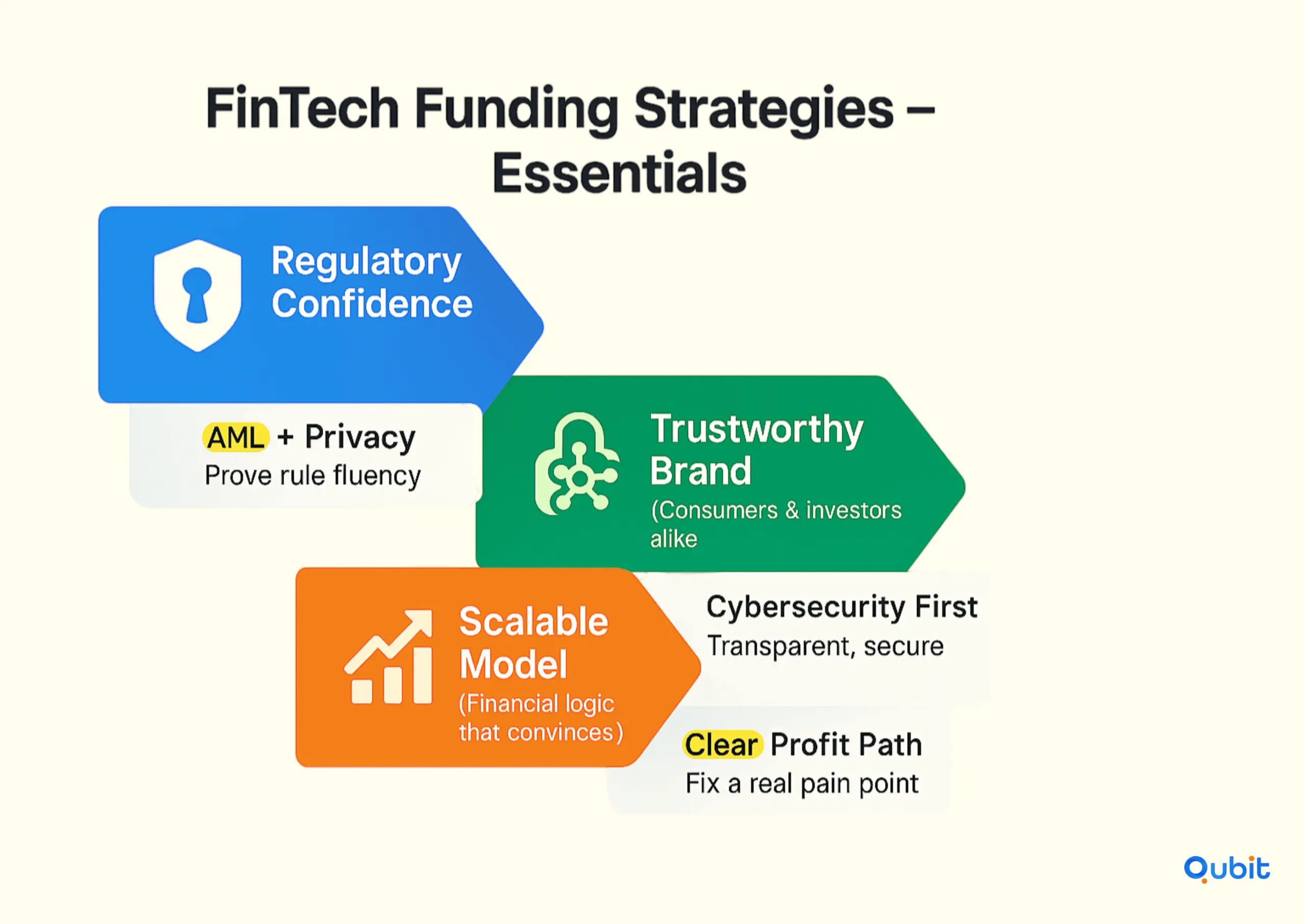

The Venture Due Diligence System Is Broken

The Kalder case reveals something uncomfortable about venture capital: the due diligence system, as currently practiced, doesn't reliably prevent fraud. It doesn't even catch obvious fraud.

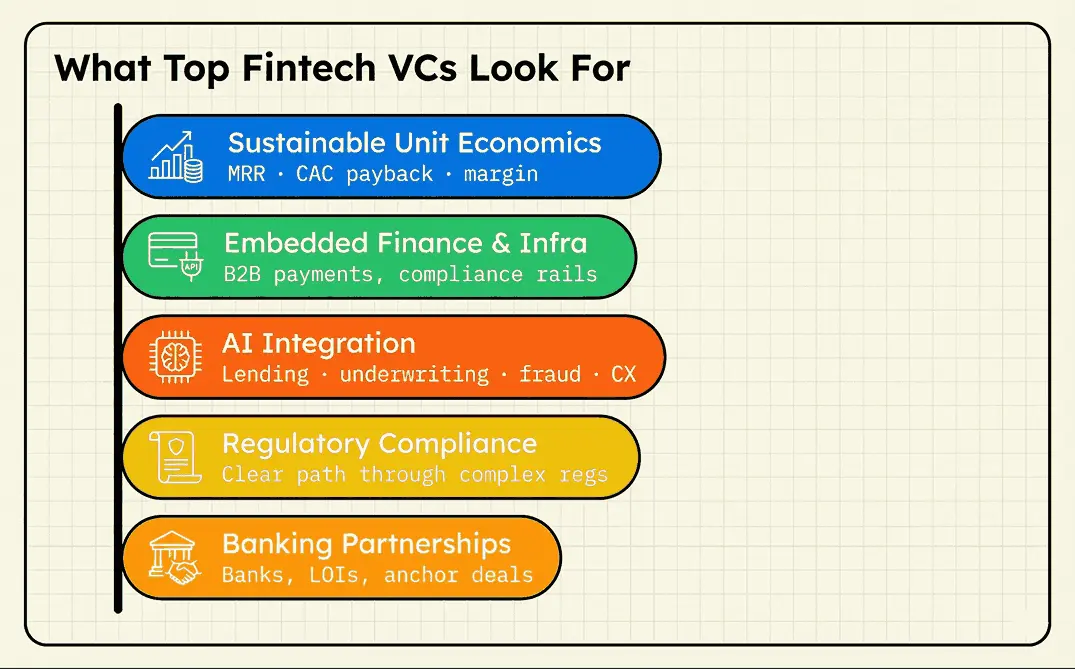

Venture capital due diligence traditionally focuses on market size, product-market fit, team quality, and defensibility. These are the right things to evaluate. But they're evaluated largely through conversations with founders, review of internal documents, and technology assessment. They're not evaluated by talking to customers, verifying metrics independently, or bringing in external auditors.

This made sense when the venture ecosystem was smaller and slower. When startup rounds took months instead of weeks. When there was time for detailed financial review. But modern venture capital has optimized for speed. A good venture capital firm can evaluate a deal in four to six weeks. The timeline is compressed. The due diligence has to be compressed too.

When due diligence is compressed, verification is one of the first things to get cut. Why spend three weeks verifying revenue claims when you can spend one week reviewing financial projections and talking to the founder? Why call customers when the founder has already given you client lists? Why verify anything when the founder's track record seems solid and the Forbes 30 Under 30 validation provides external credibility?

Gökçe Güven had external credibility. She was on Forbes 30 Under 30. That's not a credential you can fake. That's validation from a major publication. If you're a venture capitalist pressed for time, does that credential reduce the due diligence you think is necessary? Almost certainly. And if it does, you've just created the exact conditions where fraud thrives.

Another problem is that venture capital due diligence is not designed to catch lies. It's designed to evaluate fundamentals. If a founder lies about revenue, due diligence might not catch it unless you specifically verify revenue. If a founder misrepresents customer relationships, due diligence might not catch it unless you specifically verify customer relationships.

Modern venture due diligence relies heavily on what the founder and company tell you. There's an inherent assumption of honesty. This assumption made sense when the venture ecosystem was smaller and reputation-based. If you defrauded investors, word got around. You wouldn't be able to raise again.

But the venture ecosystem has grown too large for reputation-based enforcement. There are thousands of venture capital firms, tens of thousands of angel investors, and hundreds of thousands of founders. A founder who commits fraud in New York could raise a second round in Silicon Valley and never face consequences from their first defrauded investors.

The solution isn't to eliminate trust. It's to shift from trust-by-default to verification-by-default. Some venture firms are moving in this direction. They're hiring forensic accountants. They're requiring customer verification calls. They're bringing in technical experts who can assess whether claimed product features actually exist. But this is still rare. Most venture firms, pressed for time and constrained by capital, still operate on assumptions of honesty.

Kalder would never have successfully raised $7 million if Güven had been required to verify her customer relationships and revenue claims independently. The fraud would have been caught. But she wasn't required to do that. She was allowed to tell her story, present her documentation, and raise money based on the investor's comfort level with the narrative.

Wire Fraud and Securities Fraud: Understanding the Charges

Gökçe Güven faces serious charges. Wire fraud. Securities fraud. Visa fraud. Aggravated identity theft. These aren't light allegations. Let's understand what each one means and why the charges are so serious.

Securities fraud is the core charge. It means making false or misleading statements to induce people to invest in securities (in this case, equity in Kalder). The Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 both prohibit this. If you're raising money from investors based on material misrepresentations, that's securities fraud.

What makes a misrepresentation "material" is that it would influence a reasonable investor's decision. If Kalder had

The punishment for securities fraud is severe. Depending on severity and other factors, it can include substantial prison time and massive fines. If convicted, Güven could face decades in prison.

Wire fraud is also serious. It's using electronic communications (email, phone calls, wire transfers, etc.) to execute a fraud scheme. If Güven sent pitch decks via email that contained false information, that's wire fraud. If she made phone calls to investors where she made false statements, that's wire fraud. Wire fraud carries prison sentences up to 20 years and fines up to $250,000.

The wire fraud charge is distinct from securities fraud because it focuses on the method of communication rather than the nature of the false statement. But in practice, if you're committing securities fraud, you're almost always also committing wire fraud, because modern fundraising relies on electronic communications.

Visa fraud is about using fraudulent information to obtain an immigration benefit. This is a federal crime with penalties including fines and deportation. If Güven used false information about Kalder's success and her own achievements to support an EB-1 visa application, she violated immigration law.

Aggravated identity theft is the most specific charge. It suggests that Güven allegedly used someone else's identity as part of the fraud scheme. This could involve forged documents using someone else's name, stolen identities for false customer references, or some other form of identity misuse. Aggravated identity theft carries a mandatory two-year prison sentence on top of any other sentences.

The combination of these charges suggests a complex fraud scheme. This isn't just a founder being overly optimistic about her company's prospects. The charges suggest multiple forms of deception, multiple violations of federal law, and deliberate intent to defraud.

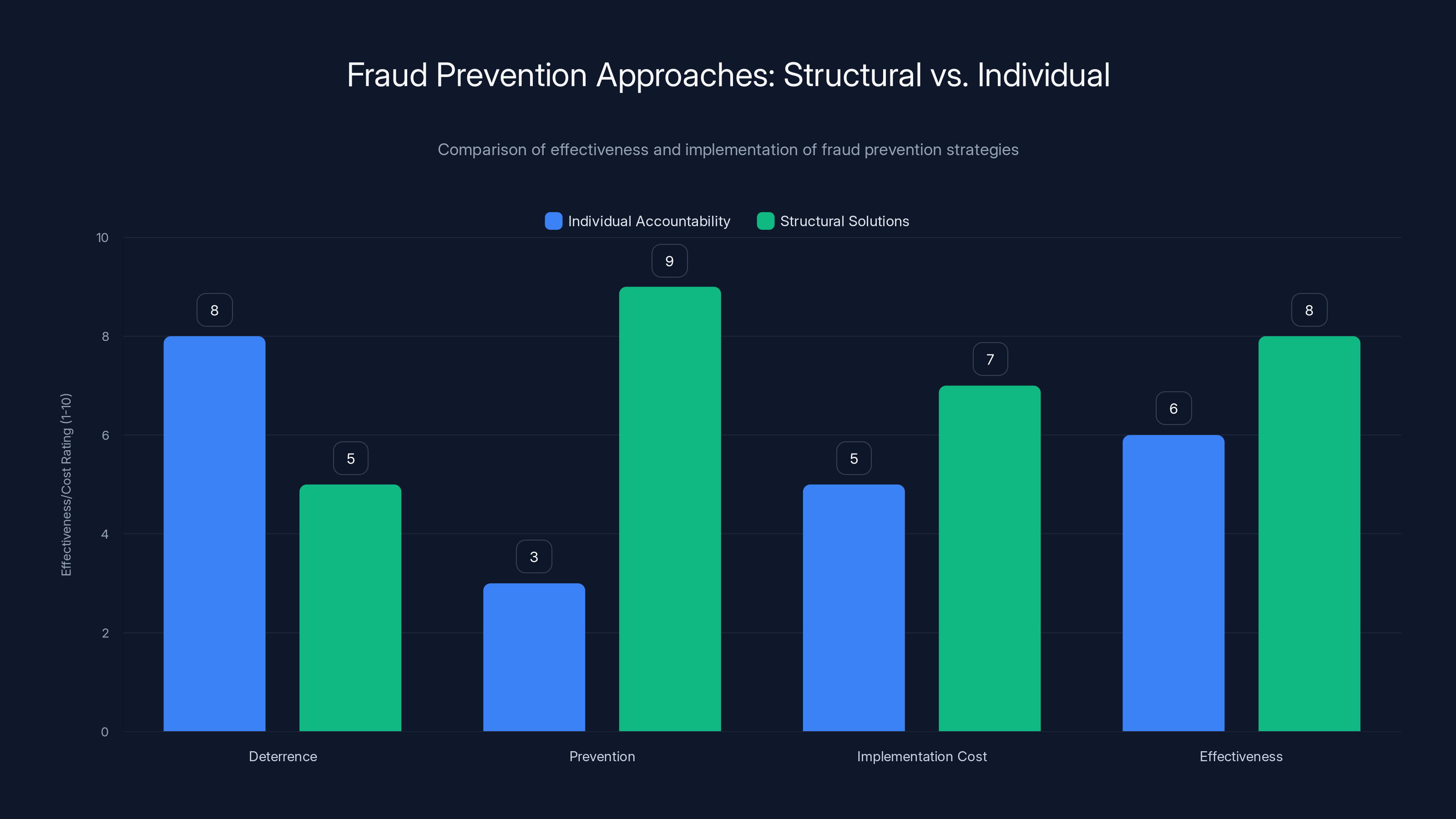

Structural solutions are more effective in preventing fraud, while individual accountability serves as a stronger deterrent. Estimated data based on typical effectiveness and cost considerations.

What Investors Can Actually Do Differently

Okay, so the Kalder case is a disaster. The question is: how do investors prevent this from happening again?

First, independent customer verification. Before investing significant capital in a B2B company, call customers directly. Don't rely on introductions from the founder. Find customer information through SEC filings, public press releases, or industry databases. Call them cold if necessary. Ask specific questions about their implementation, their spend, their satisfaction, and the timeline of their relationship with the company.

If a founder claims 26 paying customers and 53 freemium users, verify at least a statistically significant sample. If you're investing

Second, independent financial audits or reviews. For companies raising over $1 million, require that the company engage a third-party accountant to review or audit their financial statements. This doesn't have to be a full audit, which is expensive. But a review is affordable and will catch gross misstatements.

The reviewer will reconcile revenue claims with bank deposits. They'll verify that the general ledger balances. They'll identify inconsistencies between claimed revenue and actual cash received. If there are two sets of books, a competent review will find evidence of it.

Third, background checks on founders. Before investing in a founder, verify their background. Check immigration status if relevant. Verify education and previous employment. Look for civil litigation or previous fraud allegations. Research their public statements and see if there are inconsistencies.

Fourth, technology audits. If the company claims to have built technology with particular capabilities, have an independent technical expert verify that the technology actually exists and works as claimed. It's too easy for founders to show a prototype that doesn't reflect actual product capabilities.

Fifth, market research. Independent market research costs money, but it's worth it for large rounds. Hire a third party to research the market the startup claims to be targeting. Verify that the market size claims are realistic. Verify that the competitive landscape matches what the founder described.

Sixth, reference calls beyond customers. Talk to previous colleagues and investors. Ask about the founder's integrity and attention to detail. Ask whether they've seen any red flags in the founder's behavior or claims.

Seventh, legal documentation and contracts. Actually read the contracts between the company and its customers. Don't rely on summaries from the founder. Look at the actual agreements to understand the scope, timeline, and exclusivity.

Eighth, fund governance. As an investor, you have rights to information. Exercise them. Get detailed financial statements monthly, not just at funding events. Review expense reports. Understand where money is being spent. Attend board meetings. Ask hard questions.

None of these steps are unusual. Many venture firms already do some or all of them. But doing them inconsistently, doing them under time pressure, or doing them superficially is what opens the door to fraud.

The venture ecosystem needs to normalize comprehensive due diligence even for "hot" founders with external validation. The fact that someone made Forbes 30 Under 30 doesn't mean they're honest. The fact that they're charismatic doesn't mean their metrics are real. The fact that they're ambitious doesn't mean they're trustworthy.

Investors are rationally incentivized to move fast. Moving fast wins deals. It wins returns. But moving fast also creates conditions where fraud thrives. The solution is to move fast on the high-leverage activities (understanding the market, assessing product-market fit, evaluating the team's capability) while moving slow on the verification activities (checking metrics, verifying claims, confirming relationships).

The Startup Community's Response: Responsibility and Accountability

Here's something that gets lost in fraud cases: the damage extends far beyond the investors who lost money. It damages the entire startup community.

When a founder commits fraud, it undermines trust in other founders. Investors become more skeptical. They demand higher valuations for lower equity stakes because they're modeling for higher fraud risk. They demand more monitoring rights. They demand more detailed financial disclosure. These demands make it harder for honest founders to raise capital.

When a founder commits fraud, it damages the startup ecosystem's reputation with regulators. The SEC pays attention. Congress pays attention. There's political appetite for restricting venture capital, regulating startup equity, or creating new requirements for startup fundraising. These regulations, even when well-intentioned, create friction that slows down legitimate innovation.

When a founder commits fraud, it damages the reputation of the accelerators, mentors, and investors who supported that founder. If you were an investor in Kalder, you're associated with fraud. Your reputation takes a hit. Future founders are more skeptical of your guidance. Future investors are more skeptical of your judgment.

When a founder commits fraud, it damages confidence in validation mechanisms like Forbes 30 Under 30. If multiple Forbes 30 Under 30 alumni have been charged with fraud, does that credential lose its meaning? Does it become a liability rather than an asset?

The startup community's response to fraud should be swift and unforgiving. Fraud isn't an honest mistake. It's not a failure of execution. It's a fundamental violation of trust. If you commit fraud, you should be prosecuted. You should go to prison. You should be permanently barred from raising capital or running companies. You should become a cautionary tale.

Some of this will happen to Gökçe Güven. She'll face trial. If convicted, she'll face prison time. She'll be barred from serving as an officer or director of companies. Her career in startup leadership is over.

But there's a broader responsibility. The venture community should own its role in creating conditions where fraud can happen. The emphasis on growth-at-all-costs. The reluctance to do thorough due diligence because it takes time. The tendency to celebrate ambitious founders even when the evidence of their claims is weak. These cultural factors enabled Kalder's fraud.

The response isn't to make venture capital overly bureaucratic. It's to demand integrity at every level. It's to ask hard questions. It's to verify claims. It's to value honest founders who admit what they don't know over charismatic founders who claim certainty about everything.

It's also to recognize that fraud prevention is everyone's job. Investors should do better due diligence. Accelerators should screen founders more carefully. Professional networks should verify claims before recommending people to positions of prominence. Publications like Forbes should have second thoughts before featuring founders who haven't been thoroughly vetted.

The Kalder case is an opportunity for the startup ecosystem to reset. To acknowledge that the current system enables fraud. To implement better safeguards. To choose integrity over speed.

Estimated data suggests that approximately 30% of notable Forbes 30 Under 30 honorees have faced fraud allegations, highlighting a potential pattern of early success linked to questionable practices.

The Role of Credential Inflation and Public Validation

Let's talk about something uncomfortable: Gökçe Güven's inclusion on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list might have actually enabled her fraud.

Here's why. When you're raising money from sophisticated investors, they evaluate you partially on credentials and external validation. Where did you go to school? What have you built before? What do others say about you? Have you been recognized by credible third parties?

Making Forbes 30 Under 30 is such a credential. It's essentially a third-party validation that you're exceptional. The publication reviewed your company, your achievements, and your potential. They decided you qualified for one of the 30 spots allocated to people under 30 in your industry.

But here's the problem. Forbes 30 Under 30 selection is based on the company's current state and the founder's claims about it. If the founder is lying about the company's state, Forbes can't know that. The publication isn't conducting deep due diligence. They're evaluating submissions, conducting interviews, and making decisions based on publicly available information and what the founder tells them.

So Gökçe Güven submitted her application claiming that Kalder had 26 customers, was in discussions with dozens more, and had impressive revenue growth. Forbes evaluated the application. Kalder sounded like a legitimate company with promising early traction. Güven's story seemed compelling. She got selected.

Now here's the insidious part. Once Güven was on the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, that credential changed how investors perceived her. Investors figured that Forbes had done some diligence. That if Güven's company was fraudulent, Forbes wouldn't have featured it. That the credential reduced the investment risk.

This is credential inflation. A credential that is only as strong as its underlying verification becomes treated as though it's more authoritative than it actually is. Forbes isn't a venture capital firm. They don't do financial audits. They don't verify customer relationships. They evaluate submissions and make editorial decisions. That's a meaningful credential, but it's not the same as third-party verification of metrics.

Investors who relied on Forbes 30 Under 30 as evidence that Kalder was legitimate made a mistake. They outsourced their due diligence to a publication that isn't designed to do due diligence.

This happens all the time in venture capital. An accelerator like Y Combinator or Techstars validates a company, so investors assume the company must be solid. A prominent angel investor leads a round, so other investors assume the lead investor did diligence. A company gets media coverage, so investors assume the company must be legitimate (why would they get media coverage if something was wrong?).

Each of these credentials has some value. But they're not substitutes for real due diligence. An accelerator can help a company succeed, but it can't guarantee the company isn't committing fraud. An angel investor can provide good advice, but they might not have verified the company's metrics. Media coverage is often based on press releases and founder interviews, not investigation.

The Kalder case reveals the danger of treating credentials as though they reduce the need for verification. They don't. Each credential is useful information, but it's not gospel. Investors need to verify claims independently regardless of what external validation a company has received.

Frankly, this might be a lesson that Forbes itself needs to take seriously. Multiple founder selections have resulted in fraud prosecutions. That's a problem for the credibility of the list. Does Forbes need to do better vetting of applicants? Should they require financial verification before selecting founders? Should they have a process for removing people from the list if they're charged with fraud?

These are tough questions. But they're worth asking.

Fraud Prevention: Structural Solutions vs. Individual Accountability

When we talk about preventing fraud, there are two approaches: structural solutions and individual accountability.

Individual accountability means prosecuting people who commit fraud. Sending them to prison. Imposing fines. Banning them from the industry. Gökçe Güven will presumably face this approach. If convicted, she'll go to prison.

Individual accountability is important. It's a deterrent. It's justice for victims. But it's not prevention. It doesn't stop the next person from committing fraud.

Structural solutions mean changing the system to make fraud harder to commit and easier to detect. This could include mandatory audits for companies raising over a certain amount. It could include customer verification requirements. It could include standardized financial reporting formats. It could include technology solutions that make double bookkeeping harder.

Some structural solutions are already being implemented. The SEC has increased enforcement. Venture capital firms have improved due diligence processes. Accelerators have implemented better screening. But more can be done.

One potential structural solution is requiring that significant venture fundraising be accompanied by at least a financial review by an independent accountant. This wouldn't be expensive for large rounds. A financial review of a seed-stage company costs maybe

Another potential structural solution is requiring customer verification calls as part of due diligence. Venture capital firms should make customer verification calls a standard part of their process, not an optional extra. If a company can't provide satisfied customer references, it shouldn't get funded.

Another solution is better screening of founder backgrounds. Before a founder raises significant capital, there should be a background check that investigates previous business activities, litigation history, and any signs of dishonesty. This isn't rocket science. It's standard practice in hiring. It should be standard practice in investing.

Another solution is crowdsourced verification. If investors shared fraud detection experiences and red flags, it would be harder for fraudsters to operate. A founder could raise a successful first round using fraud, but word would get out. They couldn't raise a second round.

Technology solutions could help too. Imagine a platform where companies report their metrics, and those metrics are verified through integrations with banking systems, customer management platforms, and accounting software. The data would flow directly from the source, making it impossible to maintain false metrics. Kalder couldn't claim $1.2 million in recurring revenue if the system was pulling revenue data directly from the bank account.

These solutions aren't silver bullets. Determined fraudsters will find workarounds. But they make fraud harder. They increase the chance of detection. They raise the cost of fraud attempts.

The venture ecosystem needs to embrace both individual accountability and structural solutions. Prosecute Kalder. But also implement systems that prevent the next Kalder from happening.

Kalder claimed 79 customer relationships and $1.2 million in annual revenue, which should have prompted thorough verification due to the company's early stage. Estimated data.

What This Means for Startup Founders

If you're a startup founder reading this, the Kalder case is worth thinking about. Not because it's a roadmap for committing fraud, but because it reveals how fragile the venture ecosystem's trust actually is.

If you've been tempted to stretch the truth on your pitch deck, this case is a reason not to. The personal consequences are severe. Prison time. Fines. A permanent criminal record. A destroyed reputation. A destroyed career. It's not worth it.

If you've been thinking about fudging your metrics, maintaining two sets of books, or overstating customer relationships, stop. The risk of getting caught is too high. Auditors will catch it. Due diligence will catch it. Customers will reveal it. It's not sustainable.

More fundamentally, honesty is a competitive advantage in fundraising. If you tell investors that your company has three customers with strong retention and you're working to find the fourth, you'll have fewer doors open than if you claim 26 customers. But the three-customer story is true. You can build on it. You can defend it. You can look investors in the eye and know you're not lying.

The temptation to lie comes when you're desperate. When your real metrics are underwhelming. When you're running out of money. When you feel like you're close to working but just need a little more funding to get there. That desperation is real. But the solution isn't to lie. It's to be honest about where you are and what you need.

Many successful companies have raised capital with modest metrics. Airbnb raised money when it had hundreds of users, not millions. Stripe raised when it had dozens of customers, not thousands. These companies weren't lying about their metrics. They were being honest about where they were and why investors should believe in where they were going.

Honesty also protects you from making bad decisions. If you're maintaining two sets of books, you're not actually understanding your company's financial performance. You're living in a fiction. That fiction will eventually collide with reality. Your cash will run out faster than your fake books suggested. Your customers will churn faster than your fake metrics indicated. You'll make strategic decisions based on data that doesn't reflect reality. Those decisions will be wrong.

Clearly, honesty in startup fundraising matters for legal reasons and for practical reasons. Be honest. Verify your claims. Know your numbers. Build credibility with investors by giving them accurate information. Even if your metrics are underwhelming, they're real. And reality, however disappointing, is better than fiction.

Lessons for Venture Capital Firms and Angel Investors

If you're an investor, the Kalder case is a wake-up call about the state of venture due diligence.

The first lesson is that external validation is not due diligence. Forbes 30 Under 30 is great. It means something. But it's not financial audit. It's not customer verification. Don't treat it as a substitute for doing your own diligence.

The second lesson is that charismatic founders aren't necessarily honest founders. Gökçe Güven was apparently compelling enough to make Forbes 30 Under 30. She was apparently compelling enough to convince over a dozen investors to commit $7 million. Charisma doesn't equal honesty. Evaluate founders on integrity and specificity, not just charisma and confidence.

The third lesson is that comprehensive due diligence is worth the time and money. Spending

The fourth lesson is that speed is the enemy of verification. If you're evaluating a deal in three weeks, you won't do comprehensive due diligence. You'll rely on conversations and documents. If you slow down to five or six weeks, you can do verification. If you slow down to two months, you can do comprehensive audits. Choose speed or verification, but understand that you're making that choice.

The fifth lesson is that you should trust, but verify. This famous phrase from Ronald Reagan applies perfectly to venture capital. You can trust that founders are trying to build real companies. But you should verify that their claimed metrics match reality. Trusting and verifying aren't opposites. They're complementary.

The sixth lesson is that investor rights exist for a reason. Use them. Read financial statements. Attend board meetings. Ask questions. Demand transparency. If a founder gets defensive about providing information, that's a red flag.

The seventh lesson is that you have a responsibility to other investors. If you invest in a company and subsequently discover fraud, you have an obligation to alert other investors and the SEC. Fraud thrives in secrecy. Transparency stops it.

The Path Forward: Rebuilding Trust in Startup Funding

The Kalder fraud case doesn't mean startup funding is broken. Thousands of companies are founded honestly every year. Thousands of founders are trustworthy and building real products. The venture ecosystem has created enormous value and enabled incredible innovation.

But the case does mean there are vulnerabilities. There are places where the system is fragile. Where fraud can happen and go undetected for a while. Where good intentions and reasonable speed combine to create blind spots.

Rebuilding trust doesn't mean eliminating venture capital or implementing draconian regulations. It means being smarter. Being more careful. Being more rigorous. It means choosing verification where it matters most (metrics, customer relationships, financial performance) and moving fast where speed creates value (market feedback, product iteration, strategic decisions).

It means investors demand better. It means founders are more honest. It means accelerators screen more carefully. It means publications think carefully about the credentials they assign.

Most importantly, it means recognizing that fraud is a serious problem that requires serious solutions. Gökçe Güven didn't accidentally create a two-tier financial system. She deliberately deceived investors to raise money. That's not entrepreneurial ambition. That's crime. And it should be treated as such.

The venture ecosystem is strong enough to handle this. To prosecute fraudsters. To improve systems. To rebuild trust. But only if we collectively decide that integrity matters more than speed. That verification matters more than reputation. That honesty matters more than hype.

The Kalder case is a failure. But it's a failure that can teach us something. That can make the next generation of investors, founders, and accelerators better. The question is whether the startup community will learn the lesson or ignore it until the next fraud case arrives.

FAQ

What is the Kalder fraud case about?

Gökçe Güven, a 26-year-old Turkish national and founder of fintech startup Kalder, was charged with federal crimes including securities fraud, wire fraud, visa fraud, and aggravated identity theft. According to federal prosecutors, Güven allegedly presented investors with a pitch deck containing false claims about Kalder's customer relationships and recurring revenue, raised $7 million from over a dozen investors based on this fraudulent documentation, maintained two separate sets of financial books to hide the company's true performance, and used false information about Kalder to obtain an EB-1 visa for extraordinary ability.

What specific metrics did Kalder allegedly misrepresent?

Kalder's pitch deck allegedly claimed the company had 26 brands actively using its platform and 53 brands in "live freemium" status. The company also allegedly claimed $1.2 million in annual recurring revenue with consistent month-over-month growth since February 2023. Federal prosecutors contend that many of the companies on the client list had never signed actual agreements with Kalder, some were in temporary pilot programs with heavy discounts that didn't represent real commitments, and the recurring revenue figures were fabricated rather than based on actual customer payments.

How does the Kalder case relate to other startup fraud cases?

Gökçe Güven is part of a troubling pattern of Forbes 30 Under 30 alumni who were later charged with fraud. Previous notable cases include FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried, Frank CEO Charlie Javice, All Here Education founder Joanna Smith-Griffin, and pharma entrepreneur Martin Shkreli. This pattern suggests either that the Forbes selection process hasn't adequately verified founders' claims or that the recognition itself somehow enables or attracts fraudsters. The pattern raises questions about how credentials like Forbes 30 Under 30 influence investor due diligence decisions.

What warning signs should investors have noticed about Kalder?

Several red flags should have triggered additional verification during Kalder's seed round. First, the customer list of 79 relationships for a two-year-old startup was unusually high and should have prompted verification calls to customers. Second, the claim of $1.2 million in recurring revenue with consistent growth should have required independent financial verification. Third, the existence of two separate sets of financial books suggests deliberate deception that a proper accounting review would have uncovered. Finally, the founder's visa fraud allegations suggest background verification failures that should have been caught earlier.

What does securities fraud mean in the startup context?

Securities fraud occurs when founders make material misrepresentations (false or misleading statements about important facts) to induce investors to purchase equity in a company. Material means that a reasonable investor would consider the information important in making their investment decision. In Kalder's case, false claims about customer relationships and revenue would be material because they directly affect how an investor evaluates the company's growth trajectory and business viability. Securities fraud is a federal crime with serious penalties including prison sentences and substantial fines.

How should investors verify startup metrics before investing?

Investors should implement multiple verification layers including independent customer reference calls made directly to customers rather than through founder introductions, engagement of third-party accountants to review financial statements and reconcile claimed revenue with actual bank deposits, technology audits to verify that claimed product features actually exist and function as described, independent market research to validate market size and competitive landscape claims, legal review of actual customer contracts rather than summaries provided by founders, and background checks on founders that verify education, previous employment, immigration status, and any history of litigation. These verification steps are standard practice for institutional investors but are sometimes overlooked by angel investors or venture firms moving quickly.

What are the specific federal charges against Gökçe Güven and their penalties?

Güven faces four main charges: securities fraud for making false statements to induce investors, which carries potential prison time and fines; wire fraud for using electronic communications to execute the fraud scheme, which carries up to 20 years in prison; visa fraud for using fraudulent claims to obtain an EB-1 visa, which includes potential deportation; and aggravated identity theft, which carries a mandatory two-year prison sentence. The combination of these charges indicates a complex, multi-faceted fraud scheme rather than a simple case of optimistic projections that didn't pan out.

Why did venture investors miss the Kalder fraud?

Multiple factors contributed to the missed fraud detection. First, modern venture capital has optimized for speed, compressing due diligence timelines from months to weeks, which forces investors to prioritize conversations and document review over independent verification. Second, external validation like Forbes 30 Under 30 created a false sense of security that other parties had already conducted due diligence. Third, the venture ecosystem historically operates on trust-by-default assumptions where honesty is presumed unless proven otherwise. Fourth, comprehensive verification requires specific expertise (accounting review, customer calls, technical audits) that not all venture firms have readily available. Finally, investor time constraints and the pressure to move quickly on "hot" deals incentivize shortcuts in the due diligence process.

What structural changes could prevent similar startup fraud cases?

Potential structural solutions include requiring independent financial reviews for any venture round above a specified threshold (potentially $1 million), implementing mandatory customer verification calls as a standard part of due diligence, requiring founder background checks before significant capital deployment, creating industry-wide fraud reporting platforms where investors can share red flags and detection experiences, developing technology solutions that pull metrics directly from banking and accounting systems to make false reporting harder, and establishing clearer standards for what constitutes acceptable credential verification before assigning public validation like Forbes 30 Under 30. These solutions need to balance preventing fraud with avoiding excessive bureaucracy that slows legitimate innovation.

How should startups position themselves honestly during fundraising?

Honest positioning is actually advantageous. If your startup has modest but real metrics, those metrics are defensible and inspirable. Investors will understand that many successful companies like Airbnb and Stripe started with modest numbers. Being honest about your current state and transparent about your plans for growth builds credibility with investors. Honesty also forces you to actually understand your business metrics rather than maintaining false data, which leads to better decision-making. Additionally, honest founders can look investors in the eye knowing they're not lying, which actually increases confidence and trust. The temptation to lie comes from desperation, but honesty is stronger foundation for long-term relationships with investors who will support your company through difficult periods.

What role do publications and accelerators play in preventing startup fraud?

Publications like Forbes and accelerators like Y Combinator and Techstars create credentials that influence how investors evaluate startups. However, these credentials should not be treated as substitutes for independent due diligence. Publications can't conduct deep financial audits of every featured company. Accelerators can provide mentorship and guidance but can't guarantee financial honesty. The venture community has increasingly treated these credentials as having greater authority than they actually possess. A more balanced approach would treat them as useful but non-definitive signals that warrant further investigation rather than as evidence that due diligence has already been completed.

Conclusion: The Reckoning and the Path Forward

Gökçe Güven's fraud charges represent more than just a criminal case. They represent a moment of reckoning for the startup ecosystem. We've built a culture that celebrates ambitious founders, moves fast, and trusts people with other people's money. That culture has created enormous value. It's enabled innovation. It's created companies worth billions of dollars. But it's also created conditions where fraud can flourish.

The Kalder case forces us to ask uncomfortable questions. Have we optimized for speed at the expense of integrity? Have we treated external credentials as substitutes for verification? Have we celebrated ambition even when the evidence supporting claims was weak? The honest answer to all three questions is yes, at least sometimes. Not always, not everywhere, but enough that fraud becomes possible.

But here's the good news: this is fixable. It doesn't require dismantling venture capital. It doesn't require crushing innovation under bureaucratic processes. It requires being smarter about where we move fast and where we move slow.

Move fast on product development. Move fast on market feedback. Move fast on strategic decisions. But move slow on verification. Move slow on financial claims. Move slow on founder background checks. Move slow on customer relationship verification.

The venture ecosystem is strong enough to incorporate these changes. We have the expertise. We have the processes. We have the resources. What we need is the will to prioritize integrity as much as we prioritize returns.

Gökçe Güven will face trial. If convicted, she'll go to prison. Justice will be served to the individuals who lost money investing in Kalder. But the broader work is on the venture community to ensure that the next Kalder doesn't get funded in the first place.

This work starts with acknowledging that the current system has vulnerabilities. It continues with implementing better safeguards. And it culminates in rebuilding a startup ecosystem where honesty and verification are valued as much as speed and growth. That's the path forward. It's not complicated. It just requires commitment.

Key Takeaways

- Gökçe Güven of Kalder was charged with federal fraud for allegedly raising $7 million using fabricated client lists, false revenue claims, and double bookkeeping practices

- Multiple Forbes 30 Under 30 alumni have faced fraud prosecution, suggesting the credential can create false confidence in due diligence rather than reducing investment risk

- Comprehensive due diligence including independent customer verification, financial audits, and background checks would have caught Kalder's fraud immediately

- Modern venture capital's emphasis on speed creates conditions where fraud can occur by compressing the time available for proper verification

- Structural solutions including mandatory financial reviews, customer verification requirements, and founder background checks can prevent future fraud without eliminating venture capital's ability to innovate

![Fintech CEO Fraud Charges: What Startups Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fintech-ceo-fraud-charges-what-startups-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1770079081111.jpg)