The Dark Side of Hot Seed Rounds in AI: When Founders Keep the Money

Here's the conversation nobody's having yet, but they should be. In the last 18 months, I've watched something happen that would've been unthinkable in venture capital a decade ago. Three separate seed rounds, all structured on SAFEs, all raising between

I'm not talking about pivots gone wrong. I'm not talking about teams that tried and failed. I'm talking about founders who raised capital, did the math on risk versus reward, and decided the smartest move was keeping the cash. No product launch. No serious attempt. Just silent repositories of investor capital with zero accountability.

The scary part? None of it was technically illegal. No fraudulent revenue claims. No fake customers. Just a clean exploitation of the SAFE structure combined with a market so hot that institutional diligence essentially evaporated. This article breaks down exactly what happened, why it's happening now, and what you need to do to protect yourself if you're writing checks into this market.

TL; DR

- Three separate 5M seed rounds in 2025 had founders who kept investor capital without building products

- SAFEs provided zero legal recourse because they're structured as debt instruments with no equity rights until conversion

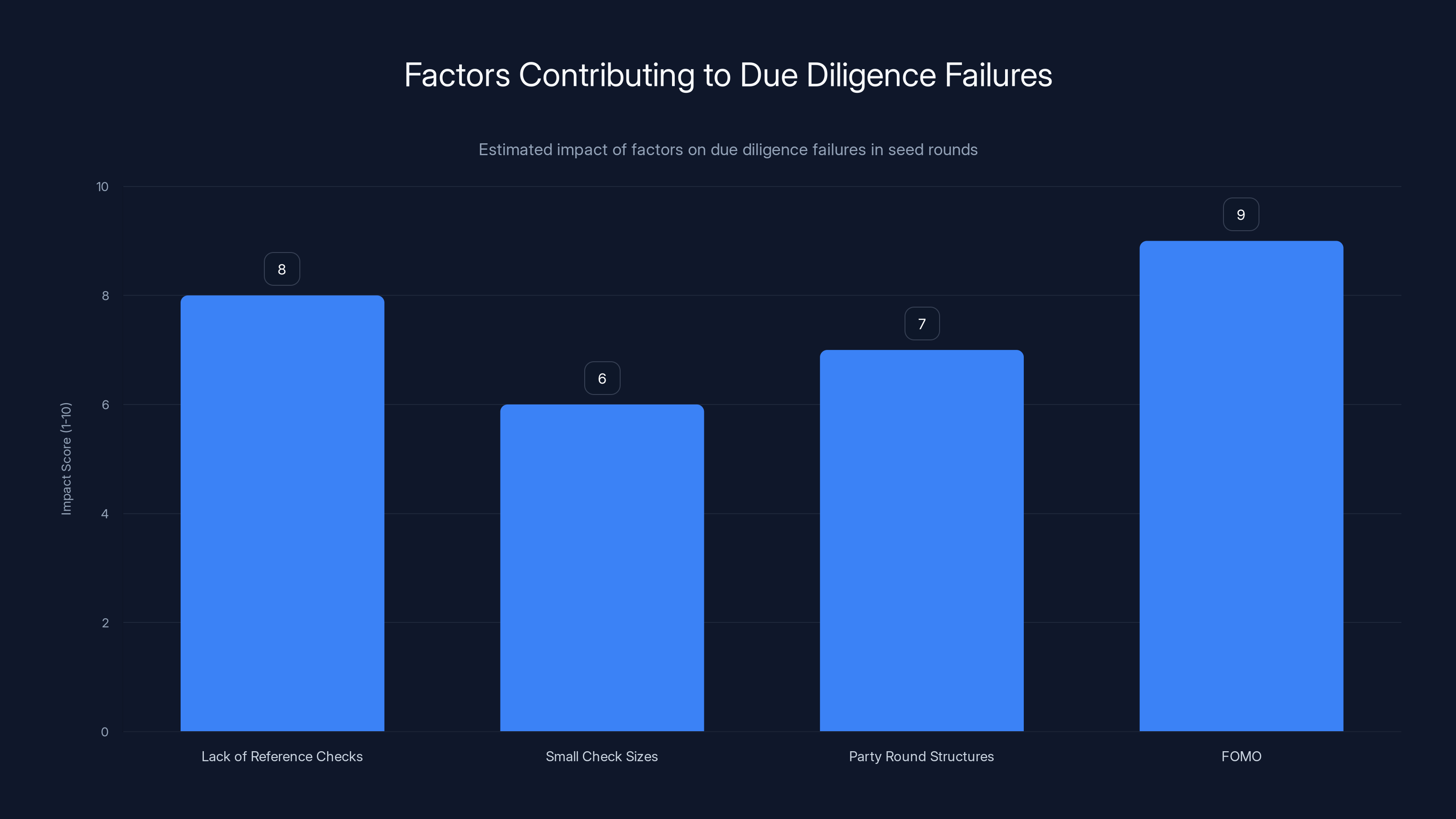

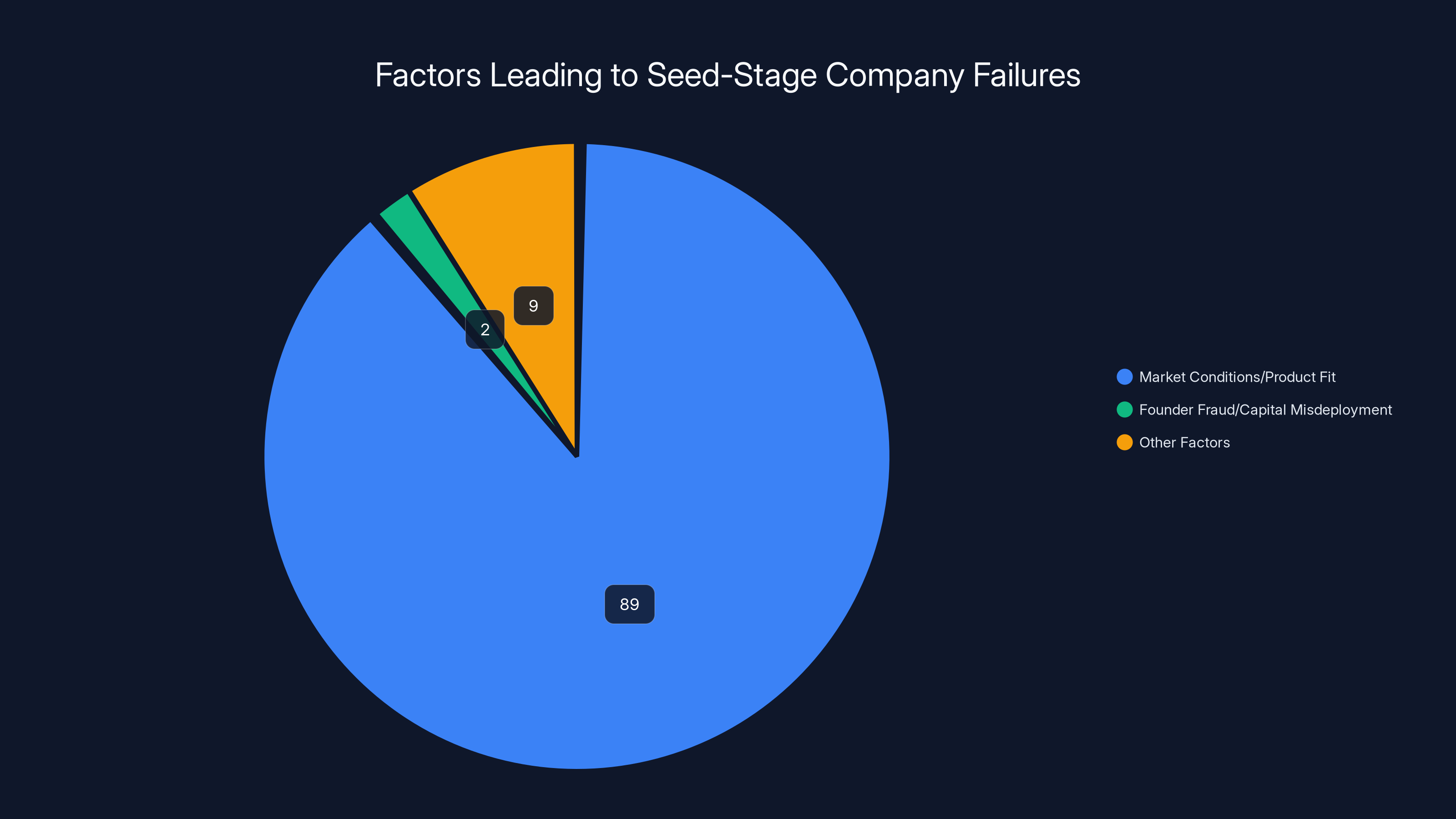

- Reference checks were skipped in 60%+ of cases due to FOMO, hot deal velocity, and party round dynamics

- The AI market's speed enables both hypergrowth and hyper-opportunism at the same velocity

- Investors often misunderstand SAFE mechanics, thinking wired money equals ownership rights when it doesn't

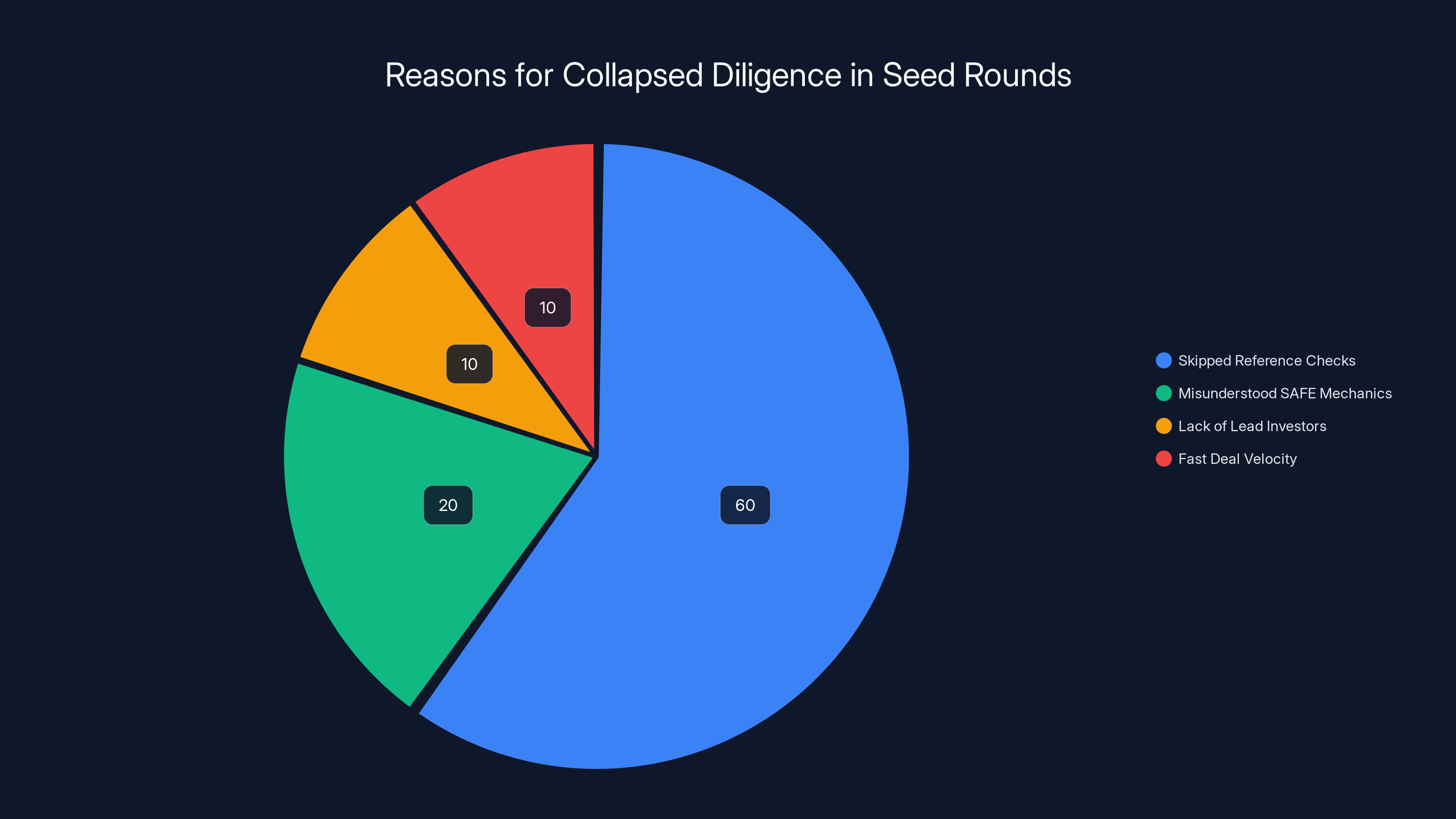

- Diligence collapsed when check sizes stayed small, when leads weren't present, or when deals moved too fast

- The solution isn't complicated: reference checks with prior investors, lead investors who care, and founder background verification before wiring anything

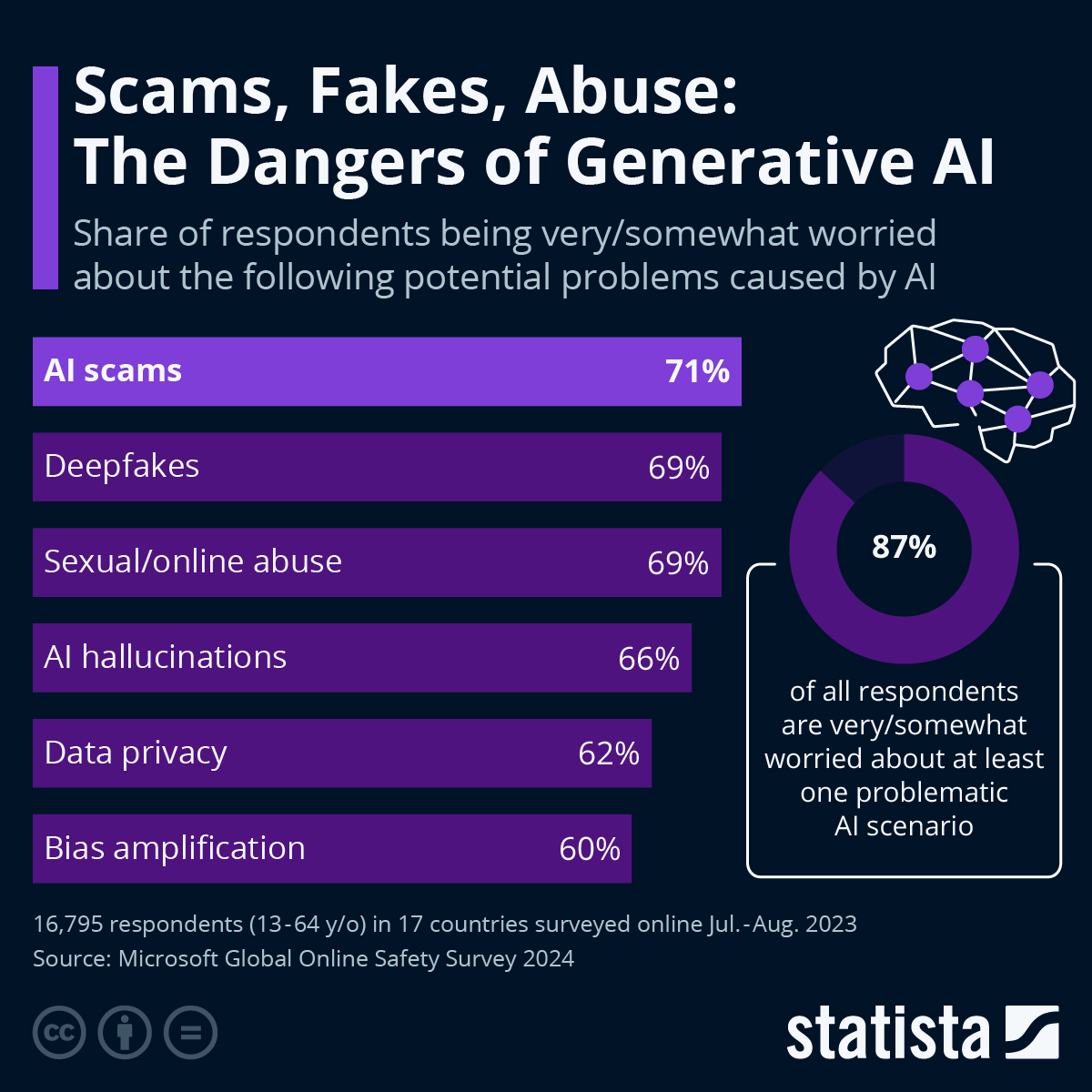

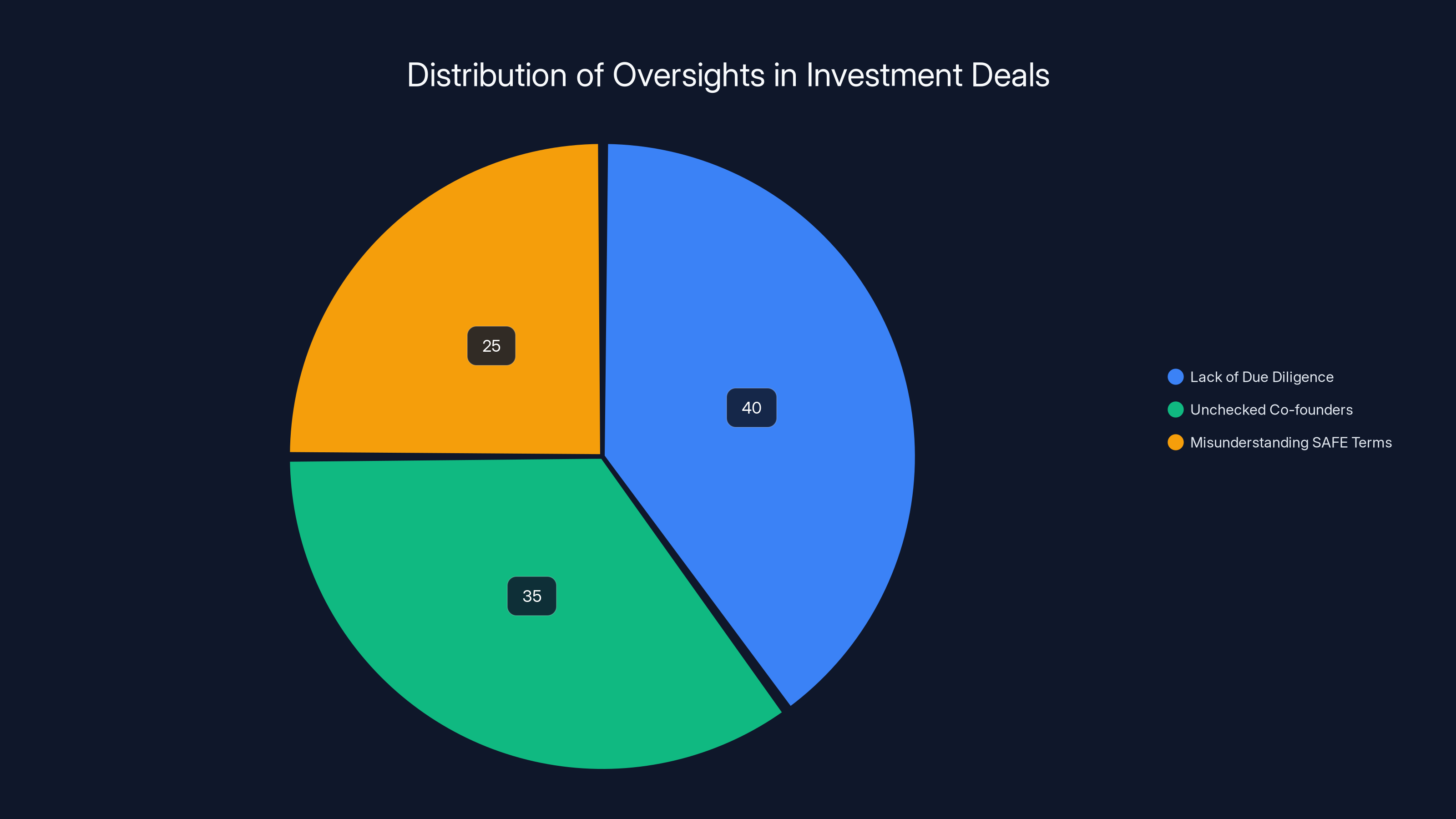

FOMO and lack of reference checks are major contributors to due diligence failures. Estimated data based on common patterns.

The Three Deals That Shattered My Assumptions

I need to be specific here because the pattern matters more than the individual failures.

Deal One: The $5M+ SAFE Nobody Actually Vetted

This round had everything a hot deal needs. The founding team had strong credentials. Prior successful exits. The market opportunity looked real. The round came together fast, which in today's environment is a feature, not a bug. Multiple investors. Institutional capital. Real firms writing checks.

Here's what got skipped: reference checks with the founders' previous investors. When the round moved quickly through FOMO, everyone made an assumption. Someone else had done diligence. Someone else had called the prior VCs to ask what these founders were actually like to work with. Someone else had dug into whether these people followed through when things got hard.

Spoiler alert. No one had.

One founder decided after closing that the personal risk of building a capital-intensive AI product was too high. The upside wasn't certain. The effort required was substantial. But the capital was already in the bank. So they took a different path. Kept most of it. Called the rest "ongoing market research and exploratory expenses."

When investors pushed back, they got told that SAFEs don't create investor rights. That the founders owed them nothing. That the SAFE was debt, not equity, and debt holders don't get to tell you how to run your business.

Technically accurate. Incredibly destructive.

Deal Two: The $4M Split Where Half the Team Wasn't Checked

This one is almost worse because it shows how specific the failure can be. Reference checks were done. On one of the two co-founders. The one who wanted to actually build the company. The founder who saw personal upside in execution.

The other co-founder? No reference checks. No calls to prior investors. No conversation with people who'd worked with them before. And that founder decided the SAFE was basically a personal bank account. Not fraud. Just unconventional cash deployment.

The irony is brutal. They spent time vetting the person who was likely to be trustworthy and skipped the person who became the actual risk.

Deal Three: The $2M+ Party Round With No Lead

This structure screams trouble if you know what to listen for. No lead investor. Just 15-20 people writing small checks.

Classic party round problem. Everyone's checking is small enough to feel comfortable taking minimal risk. So everyone takes the same risk. No one does diligence. Result? A SAFE with 20 different investors, zero founder accountability, and no one willing to be the bad guy who actually pushes back.

The outcome is still unfolding, but it's following the pattern. One founder is keeping the capital. The other is returning portions after pressure. Nothing close to full repayment. Just enough to make the noise stop.

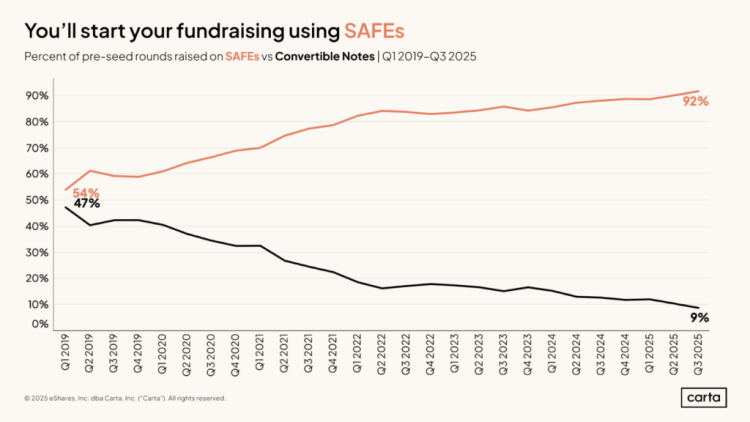

Why SAFEs Became the Perfect Structure for This Problem

To understand how this happened, you need to understand what a SAFE actually is. And I mean actually understand it, not the watered-down version most founders and investors casually discuss.

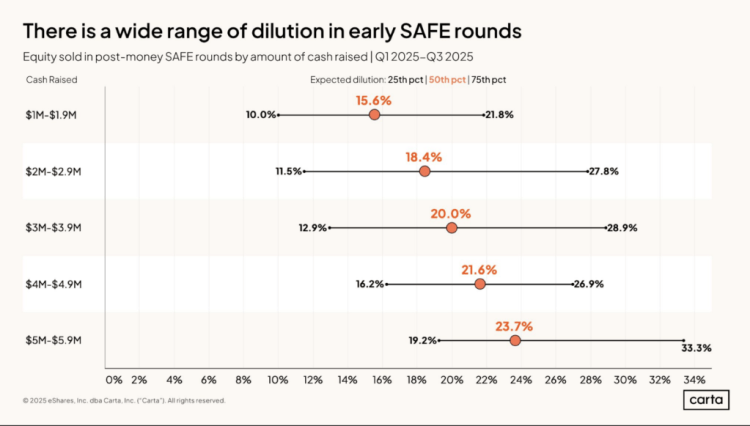

A SAFE is a Simple Agreement for Future Equity. It's not a stock purchase agreement. It's not equity. It's a contractual promise to convert into equity at a future date, usually when the company raises a priced round or hits certain milestones.

Until that conversion happens, SAFE holders are creditors, not shareholders. They have no voting rights. They have no board seat. They have no legal standing to demand that the company actually do anything with the capital. They wired money for the promise of future equity that may or may not materialize.

Let that sink in. You write a $500K check into a SAFE. You own nothing. You control nothing. You have no recourse if the founder decides to spend the money on a house instead of a server. Legally, you just made a loan with no interest, no maturity date, and no collateral.

The SAFE was designed to be founder-friendly and simple. It is both of those things. But in a market where founders can raise capital on hype alone, where diligence is optional, and where there's absolutely zero oversight of what happens after close, it became a vehicle for founders to raise money with zero accountability.

Skipped reference checks accounted for over 60% of collapsed diligence cases, highlighting a major oversight in the investment process. Estimated data based on narrative.

The AI Market's Acceleration Made This Inevitable

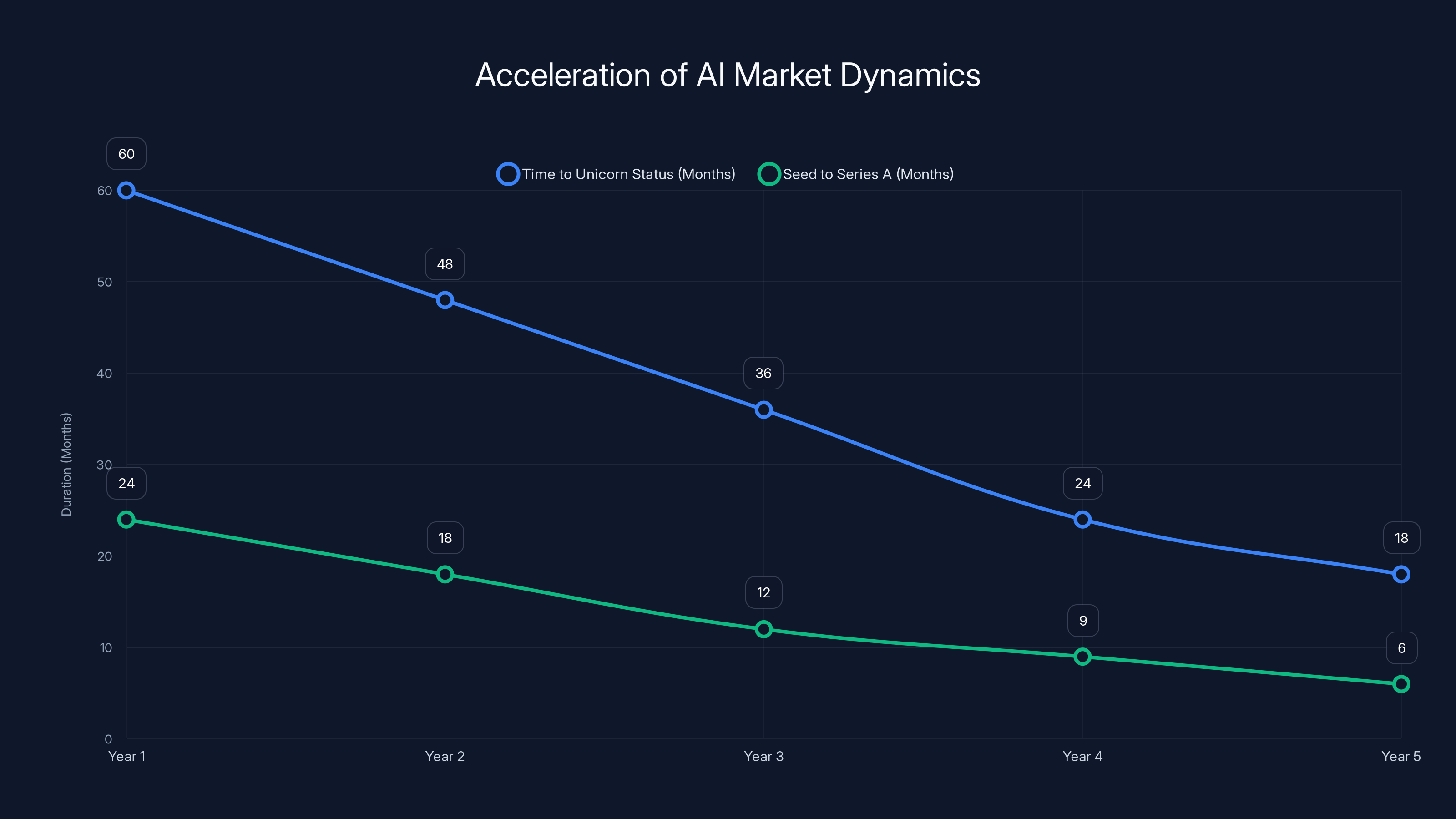

This wouldn't be happening without the specific market conditions we're in right now. The acceleration is real. Companies are hitting unicorn status in 18 months instead of 5 years. AI is moving so fast that what seems impossible one quarter becomes commodity the next. That velocity creates opportunity. It also creates chaos.

When capital is abundant, diligence collapses. This is a pattern as old as venture capital itself. When everyone's competing to deploy capital quickly, the investors who ask hard questions get cut out of rounds. So they stop asking hard questions. Rounds close faster. Diligence gets worse. Risk increases.

Add to that the fact that investors don't fully understand what they're investing in. AI is complex. You can look credible without actually having anything real. A good engineer, a compelling pitch deck, and some basic proof of concept can look exactly like a legitimate startup. Or it can look exactly like someone running a con. The difference isn't always visible at seed stage.

The combination is toxic:

Capital abundance removes the natural friction of "we need to be sure about this". When investors have $100M to deploy and 5,000 companies applying, they move fast and take risks they wouldn't normally take.

FOMO is institutional now. It's not just the founders who feel it. VCs are explicitly looking at whether their portfolio will have AI exposure. Missing a deal that becomes big is a career risk. So they move fast. Too fast.

Complexity works as cover. When something is hard to understand, it's easier to skip diligence. "I don't really understand the technical architecture, so I'll trust the founders." That's how due diligence dies.

Seed velocity is insane. Companies are raising seed rounds, hitting product market fit, and raising Series A in under 12 months. That speed is real. But it also means investors who want in have to move faster than they normally would. Faster than is safe.

The Reference Check Problem That Nobody Wants to Address

Let me be direct about this. Reference checks are the single best way to identify founder risk, and they're being skipped across the market. Not always. But consistently enough to be a systemic problem.

Here's what a real reference check looks like: You call their previous investors. You ask specific questions. Would you invest in them again? What were the founder's weaknesses? When things got hard, how did they respond? Did they take accountability or make excuses? Did they communicate proactively or disappear?

That conversation takes 20 minutes. Maybe 30 if you get into details. And it's worth more than every other form of diligence combined. Because investors who have actually worked with someone will tell you the truth. They'll tell you whether the founder is trustworthy when the pressure is on.

But it requires doing the work. It requires making calls. And in a hot market, that work gets skipped.

In Deal One, no reference checks were done with prior investors. Hot round. Everyone assumed someone else had done it. Everyone was wrong.

In Deal Two, reference checks were done on the wrong founder. The founder who was likely to be fine anyway. The one who probably would've been okay to skip checking. And the founder who became the actual problem never got a call.

In Deal Three, no one did reference checks. Party round. Check sizes too small. Lead investor doesn't exist. No one willing to be the jerk who actually does the work.

The hard truth is that reference checks require institutional discipline. Someone has to be responsible for making the calls. Someone has to actually care about the answer. In large institutional checks, that's usually a partner. In small checks, in party rounds, in hot deals where everyone's moving fast, that responsibility dissolves.

The Economics of Breaking Faith

Here's what's actually happening in the founders' minds. They're doing math.

They raised

The risk-reward math shifts when capital becomes abundant. It's not worth it to spend three years building a capital-intensive AI product when you can take

I'm not saying these founders woke up planning to commit fraud. They didn't. They woke up realizing that the incentive structure let them take a path that required zero effort and delivered material personal wealth. And the SAFE structure meant they owed investors nothing legally.

It's the perfect storm of: abundant capital, no accountability structure, founder optionality, and a legal document that creates zero enforceable obligations.

Estimated data shows that lack of due diligence and unchecked co-founders are major oversights in investment deals, each contributing significantly to potential failures.

When Institutional Investors Act Like Angels

One pattern I noticed across all three deals is that institutional investors were writing checks, but they were acting like angels. They were writing smaller checks than they normally would. They weren't sending partners to do diligence. They weren't demanding board observation rights. They were behaving like they'd written

This happens when deals are hot. The institutional check becomes a portfolio check. "Let's take a small position in this hot round and see what happens." That's fine. But it should come with institutional-level diligence. It often doesn't.

You get institutional capital in institutional amounts, but with angel-level diligence. That's the actual problem. The capital size justifies serious work. The deal heat suggests skipping it. Result? Disaster.

The SAFE Holder Illusion

Here's what I found shocking about the aftermath of these deals. The investors genuinely believed they had recourse. They'd written checks. They'd received SAFE documents. They thought they were investors.

But when they pushed back on founder behavior, they got told the plain truth: "You're SAFE holders. You don't have rights. You're creditors, not owners. We don't have to do anything."

That response is legally accurate. It's also incredibly demoralizing to hear after you've written a $500K check. But it's the reality of the SAFE structure. Until conversion, you have a contractual claim on future equity. You don't have voting rights. You don't have governance rights. You're essentially an unsecured creditor.

Most investors don't think about it that way. They think, "I'm an investor. I own a piece. I have standing." Legally? Not until the priced round.

The Party Round Problem

One of the three deals was structured as a classic party round. No lead investor. 20 small checks. No single person responsible for oversight. This structure works for funding rounds. It's terrible for accountability.

Party rounds exist because they're easy to organize. You don't need one investor to commit to serious capital. You just need 20 people to each put in enough to feel good about the diversification. Each person's check is small enough that they're comfortable taking minimal risk. So they do.

The problem is that when everyone takes minimal risk, no one is responsible for any risk. No one does deep diligence. No one asks hard questions. No one has enough skin in the game to push back when something smells wrong.

A $2M party round with no lead is essentially a leaderless group of people putting money into a SAFE with zero structured accountability. That's a recipe for exactly what happened in Deal Three.

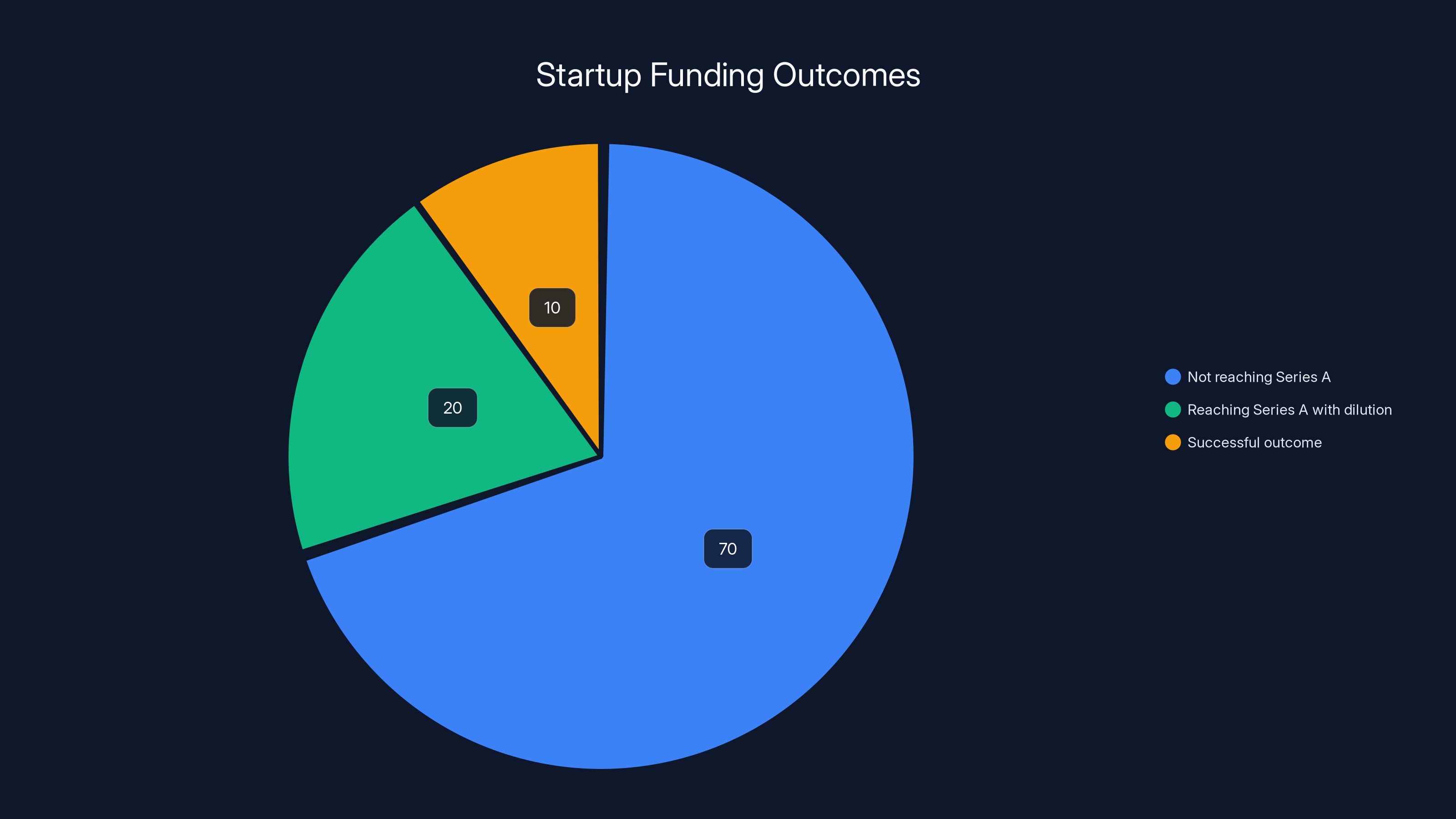

Estimated data shows a 70% probability of not reaching Series A, with only a 10% chance of a successful outcome, highlighting the challenging incentive structure for founders.

What These Founders Actually Said

I want to be specific about how the conversations went because the rationalization is instructive. When investors pushed back, here's what they heard:

From Founder One: "The SAFE is structured as a debt note. You're lenders, not investors. As lenders, you have zero right to direct how we use the capital. We're using it for market research and product exploration."

From Founder Two: "We consulted with our attorney. We have zero obligation to deploy this capital toward the original purpose. SAFE holders have no governance rights and no claim on company decisions."

From Founder Three: "The capital isn't deployed yet, but it will be used for ongoing research. We're exploring whether this market is actually viable and whether we want to continue."

All three statements are technically defensible legally. The SAFE doesn't create governance rights. The SAFE holders aren't owners. The founders can't be sued for breach. Because a SAFE isn't a promise to build something. It's a promise to convert money into equity if a qualifying event happens.

The problem isn't that these arguments are wrong. The problem is that they were predictable, and no one protected against them during diligence.

The Diligence Collapse Was Predictable

When I think about what went wrong, it's not mysterious. The conditions for diligence failure were all present.

Hot market conditions meant investors were competing for access. That removes the luxury of asking hard questions. If you ask too many questions, you get cut out of the round.

Check sizes were too small relative to effort. In Deal One, an investor writing

No lead investor meant no one was responsible for institutional-level diligence. With a lead investor who cares, at least someone is doing the work. With a party round, it's everyone's job and therefore no one's job.

SAFE mechanics aren't well understood by most investors. If you don't understand that you're an unsecured creditor, you won't structure your diligence to protect against unsecured creditor risk.

Deal momentum is powerful. Once a round gets hot, the dynamics change. Money flows in. People FOMO. Hard conversations get skipped to keep the round moving.

All of this is fixable. None of it is inevitable. But it requires discipline that the market is actively punishing right now.

The Institutional Blind Spot

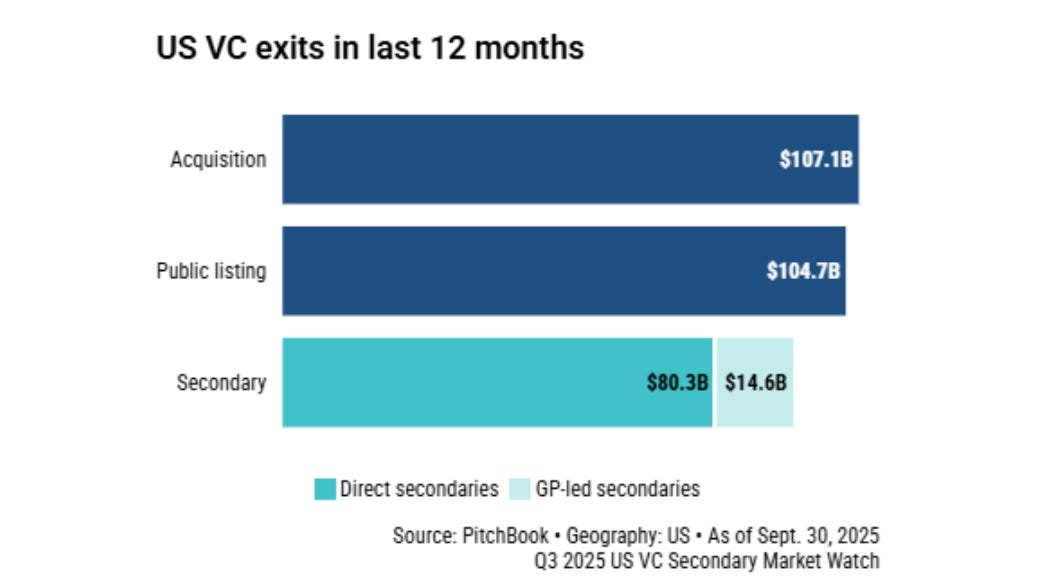

I've watched this in real time, and here's what's genuinely strange about the institutional investor response. They understand seed risk. They understand that 70% of seed companies won't get to Series A. They price that in. They expect 90% of seeds to go sideways.

But they don't seem to have contemplated the scenario where the founders deliberately don't try. Where capital gets raised and then deliberately left on the sidelines while the founders wait to see if a different idea becomes hot.

That's not capital failure. That's founder decision-making failure. And it's a category of risk that most institutional investment theses don't have a line item for.

You get categories like: product risk, market risk, team execution risk, capital efficiency risk. You don't get a category called "founder will take the money and do nothing and claim the SAFE gives them that right."

Because that would require admitting that reference checks matter. That diligence matters. That the speed of the market is creating blind spots that are costing money.

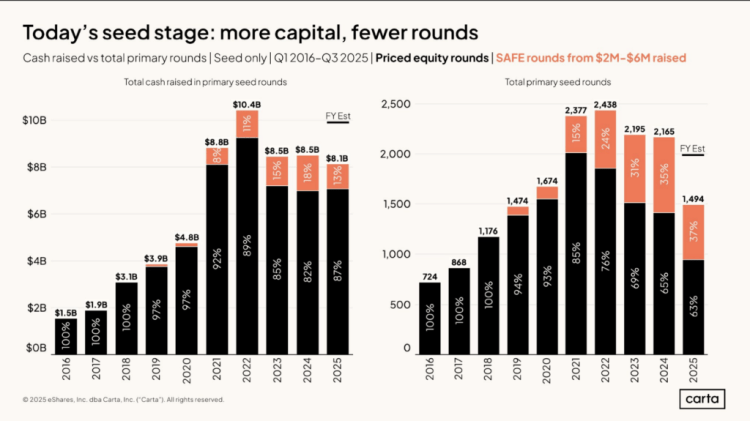

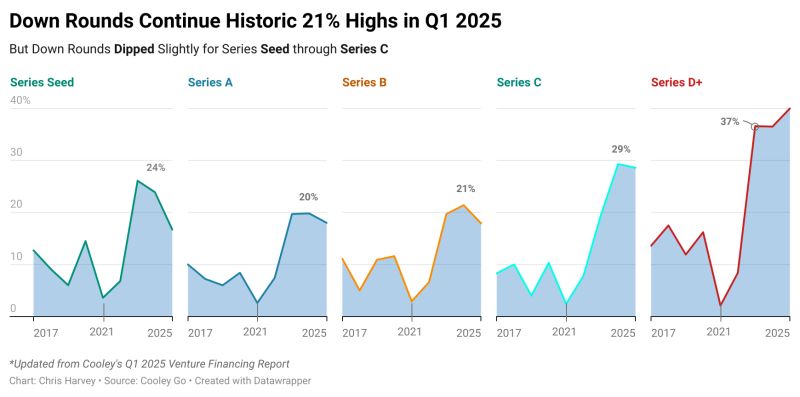

During the 2018-2019 venture boom, 89% of seed-stage company failures were due to market conditions or product fit, with founder fraud or capital misdeployment being a minor factor at 2%.

How to Actually Protect Yourself

If you're writing checks into seed rounds right now, here's what needs to happen before your money moves.

First: Call prior investors. Not the company. Not the CEO. Call the investors who've written checks into this team's previous companies. Ask: "Would you do it again?" If they hesitate, if they equivocate, if they say anything other than "absolutely," that's data. Use it.

Second: Have a lead investor you actually respect. Don't write into a party round. If there's no institutional lead investor who's done real diligence, don't participate. The lead investor's reputation is on the line. They have incentive to get it right. You want that incentive in the round.

Third: Ask about SAFE mechanics before you wire. Have your attorney explain what you're actually getting. You're getting a contractual claim on future equity that the founders are under zero obligation to work toward. That's what you're buying. If that feels risky (it should), adjust your position size accordingly.

Fourth: Check the founder backgrounds. This is basic. Have they done this before? Do they have a track record of following through when things get hard? If you don't know the answer, find out before writing the check.

Fifth: Get specific on use of proceeds. The company should have a clear, detailed budget for how seed capital gets deployed. If it's vague, if it's "market research and product exploration," that should raise a flag. If they won't commit to a timeline or deliverables, that's another flag.

Sixth: Structure for downside protection. If you're writing a meaningful check into a SAFE, negotiate terms that protect you if nothing happens. This might be a cap on the SAFE multiple, a discount on the Series A conversion, or a clawback provision. Make them commit to delivering equity or returning capital.

The Founder Incentive Problem That Nobody Talks About

Here's the uncomfortable truth about this situation. The founders aren't being irrational. They're being perfectly rational within the incentive structure they're facing.

If you raise $3M and there's zero probability that you'll raise a Series A (because the market is competitive, because your product isn't working, because the space got crowded), then you face a choice:

- Spend three years trying to build something that probably won't work, burn the capital, and end up with nothing.

- Keep the capital, return a portion to make the noise stop, and walk away with meaningful personal wealth.

Option two is economically superior if the probability of Series A is low enough. It's not fraud. It's rational economic behavior under uncertainty.

The problem is that SAFEs and the seed structure enable that behavior. A stock purchase agreement creates alignment. You own equity. You want the company to succeed so your equity has value. SAFEs create the opposite alignment. You want to minimize risk and effort while capturing upside. The cleanest way to do that is not building anything.

The fix isn't punishment. The fix is structure. Terms that align founder incentives with investor incentives. Clawback provisions. Conversion triggers tied to milestones. Equity vesting that requires continued work.

These structures exist. They're just not being used because hot markets reward speed over protection.

What's Coming Next

I have a hypothesis about what happens next, and it's not optimistic.

These three deals are just the start. Once founders realize they can raise $3M and keep it with zero legal consequence, that knowledge spreads. Other founders do the math. Realize the risk-reward has shifted. Start taking the same path. Not all of them. Maybe not even most of them. But enough.

Then you get a cohort of seed deals that produced zero companies but plenty of founder wealth extraction. Investors get tired of writing checks that disappear. They pull back. Seed capital dries up. And suddenly the easy environment for raising becomes much harder.

That's the pattern in every bubble. Abundance creates bad behavior. Bad behavior destroys trust. Destroyed trust dries up capital. Capital scarcity creates the next correction.

We're in the abundance phase. We're starting to see the bad behavior phase. The trust destruction phase is coming.

For investors, that means being early with discipline is actually the smart move. If you can deploy capital now while being selective about founders, by the time the pullback happens, you're positioned with a portfolio of reasonable teams while everyone else is stuck on the sidelines.

For founders, this is your moment to prove you're not the person who raised and disappeared. Follow through. Deliver. Because the founders who don't are about to make it very hard for the founders who do.

The AI market's acceleration is evident as companies reach unicorn status faster and the time from seed to Series A shrinks dramatically. Estimated data.

The Uncomfortable Conversation That Needs to Happen

Most of the venture community isn't talking about this openly. It's awkward. It requires admitting that due diligence failed. It requires acknowledging that SAFEs might not be the best structure in high-capital-abundance environments. It requires accepting that the market is rewarding behavior that's destructive.

But here's why it matters. You're probably going to be asked to participate in a seed round in the next six months. You might be an investor. You might be an advisor. You might be a founder in an ecosystem where SAFEs are standard.

When you see the pattern of reference checks being skipped, of party rounds without leads, of SAFE funds being treated as founder discretionary accounts, you'll know what to do. You'll ask hard questions. You'll demand institutional diligence. You'll insist on founder follow-through.

That's not pessimistic. That's realism about market structure and founder incentives. And it's the only way to keep this from becoming the default behavior.

What Investors Are Actually Getting Wrong

There's a fundamental misunderstanding about what risk we're actually managing here. Most seed investors think the risk is product-market fit. Will the market want what they build? Will the team execute? Will capital efficiency allow them to reach $1M ARR?

Those are real risks. But they're not the risk we're seeing here. The risk we're seeing is founder decision-making. Will the founders actually choose to deploy the capital toward the stated mission, or will they choose the path of least resistance and keep the money?

That's a behavioral risk, not a market risk. And it requires diligence focused on founder track record, founder communication patterns, and founder decision-making in previous situations when things got hard.

Most seed diligence doesn't focus there. Most diligence focuses on the market, the product, the go-to-market strategy. That's where we're blind.

The Thesis That Explains All Three Deals

If I had to design a thesis for why these three deals happened, it would be:

Abundant capital + speed-based selection + SAFE legal structure + skipped reference checks = founder extraction

Remove any one element and the outcome changes. If capital had been scarce, investors would've demanded accountability. If rounds moved slower, diligence would've been deeper. If SAFEs created equity governance, founders would have shareholder accountability. If reference checks had been done, the pattern would've been caught before deployment.

But with all four elements present simultaneously, the math tips toward extraction. And that's what we're seeing.

The scary part is that none of these elements are changing soon. Capital is still abundant. Speed is still rewarded. SAFEs are still the standard structure. And reference checks are still optional in hot markets.

So expect to see more of this. Not from every founder. But from enough founders that it becomes a material risk in your allocation decisions.

How to Talk About This With Your LP

If you're a VC managing capital and you're seeing this pattern in your portfolio, here's how the conversation with your LP probably needs to go:

"We have three seed investments that haven't deployed capital as planned. The founders are taking the position that SAFE structures don't require them to build anything specific. We didn't do adequate reference checks to identify this risk in advance. Here's what we're doing differently for future investments:"

That conversation is hard. It requires admitting that process failed. But it's the conversation that protects the fund going forward. Because if you don't acknowledge the pattern, you'll keep hitting it.

Your LPs would rather hear "we had three deals go sideways because of founder decision-making risk we didn't adequately manage" than get a call six months later saying "we have 12 deals in this situation."

The Founder Perspective (And Why They're Not Entirely Wrong)

I want to be fair to the founders here, because the incentive structure they're responding to is real.

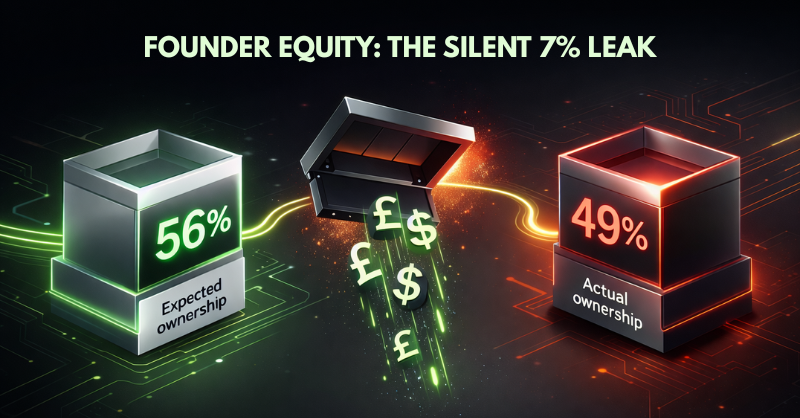

You raise $3M to build a capital-intensive AI product. The market is moving fast. You realize there's a 70% probability you won't get to Series A. You realize even if you do get to Series A, the dilution will be brutal. You realize the effort-to-reward ratio for a 30% probability of a successful outcome is terrible.

Meanwhile, you have $3M in the bank. You could keep it. SAFE structure doesn't prevent you. Founders before you have done it. Why wouldn't you?

From a pure game theory perspective, the founders are making the rational choice. The problem is that the incentive structure that makes their choice rational is also the incentive structure that kills the market over time.

So the fix isn't moral suasion. It's structure. Terms that align founder incentives with investor outcomes. That's the only way to make the rational choice also be the right choice.

What the Next 12 Months Hold

Over the next 12 months, expect to see:

More capital extraction deals. Once founders realize this is possible, more will try it. Not all. But enough that it becomes a known risk category.

Tighter SAFE terms. Smart investors will start demanding SAFE terms that protect them. Clawback provisions. Milestone conversion triggers. These will become standard.

Lead investor discipline. VCs who've been burned will start being more disciplined about requiring leads and institutional diligence. Party rounds will get more scrutiny.

Reference check renaissance. Diligence will shift back toward founder track record and track record with previous investors. This is actually good. It's the diligence that matters most.

Founder selection based on past behavior. The VCs who figure out how to filter for "founders who follow through when things get hard" will have better portfolios. Everyone else will have more capital extraction deals.

The market will self-correct. It always does. But the self-correction is expensive. Expect it to happen in the form of seed capital drying up, multiple compression, and a harder environment for founders who don't have institutional backing.

A Final Reality Check

I've been somewhat harsh on the founders here, and I want to be clear about one thing: this isn't new. Founder behavior in response to incentive structures isn't new. What's new is the scale, the speed, and the fact that the legal structure enables it so cleanly.

There have always been founders who took money and disappeared. There have always been investors who got burned. The difference now is that the abundance of capital combined with the complexity of AI makes it easier to disappear and harder for investors to catch it.

But the market will catch up. Discipline will return. Reference checks will matter again. And the founders who play the game honestly will be left with the capital and the credibility to build real companies.

That might sound optimistic given the tone of this article. But it's actually just realism about market cycles. This is a correction that's already starting. Being aware of it now puts you ahead of the correction when it fully arrives.

FAQ

What is a SAFE and why does it matter for founder accountability?

A SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) is a contractual agreement that converts your money into equity at a future date, usually during a Series A round or when certain milestones are hit. Until that conversion happens, SAFE holders are technically creditors, not shareholders, which means they have zero voting rights, no board representation, and no legal standing to demand how founders deploy capital or what the company actually builds. This distinction is critical because it means founders can theoretically raise capital on a SAFE and choose not to build anything, leaving investors with no legal recourse because the SAFE doesn't create governance obligations.

How did due diligence fail in these three seed rounds?

The diligence failures followed a consistent pattern: founders' prior investors were never contacted to provide reference checks, check sizes were small enough that individual investors felt deep diligence wasn't worth the effort, party round structures meant no single investor was responsible for institutional-level vetting, and FOMO created velocity that prioritized closing rounds over doing careful work. In each case, if investors had called just two previous backers to ask "would you invest in these founders again," the pattern would likely have been caught. But hot markets actively punish investors who ask hard questions, so they stopped asking them.

Why would founders deliberately not build after raising capital?

When founders do the math on risk versus reward, raising capital becomes less attractive than keeping it if the probability of Series A success is low enough. A founder facing a 30% chance of Series A success might rationally choose to keep $3M of seed capital rather than spend three years burning it trying to build something that probably won't work. This isn't fraud legally, because SAFEs don't contractually obligate founders to actually build anything specific. The structure enables the behavior, and the incentive structure rewards it, making it a rational economic choice even if it's destructive to the investment ecosystem.

What's the practical difference between a SAFE holder and a shareholder in terms of investor rights?

Shareholders own equity and have voting rights, board observation rights, and legal standing to make decisions about company direction. SAFE holders have a contractual claim on future equity that doesn't exist until a conversion event occurs. Until then, SAFE holders are unsecured creditors with essentially zero recourse if founders misbehave. They can't vote on founder decisions, they can't demand transparency, and they can't force the company to actually use capital for stated purposes. Legally, a SAFE holder is closer to a bondholder than an owner.

How should investors structure seed rounds to prevent this problem?

Investors need to return to institutional-level diligence even on relatively small seed checks. That means calling prior investors for reference checks, insisting on a lead investor who has skin in the game and responsibility for oversight, getting specific on founder use of proceeds with milestones and deliverables, structuring SAFEs with clawback provisions or milestone conversion triggers, and building founder track record assessment into the investment decision. Additionally, avoiding party rounds without leads removes the "everyone's job, no one's job" accountability problem. These steps require discipline that hot markets actively discourage, but they're the actual protection against this type of capital extraction.

Is this problem likely to get worse in the next 12 months?

Probably yes, at least until the market experiences a correction that makes capital scarce again. Once founders realize they can raise $3M and keep it with zero legal consequence, other founders will do the same. Institutional investors will start tightening SAFE terms and demanding deeper diligence, which will create a bifurcated market where well-backed founders can still raise on standard terms while unproven founders face much tighter requirements. The market will eventually self-correct through reduced capital availability and increased founder scrutiny, but that correction is painful for everyone involved.

What red flags should investors actually watch for during seed diligence?

Red flags include: party rounds with no lead investor (no one responsible for real diligence), vague use of proceeds language ("market research and exploration" is a warning sign), founder reference checks not completed before wiring capital, co-founders who haven't been equally vetted, small check sizes that make individual investors feel diligence isn't worth the time, and deals that move too fast (hot rounds that close in weeks are higher risk than deals that take time to vet). Additionally, founders who seem focused on capital size rather than mission execution, or who express skepticism about reference checks, should be treated as higher risk.

The Bottom Line

The dark side of hot seed rounds in the AI era is that the structure enabled by SAFEs, combined with abundant capital and skipped diligence, has created an environment where founders can rationally choose not to build. That's not fraud in the legal sense. That's not unique to AI. That is, however, a systemic failure in how capital is being deployed at the seed stage.

The fix isn't complicated. It requires diligence. It requires reference checks. It requires institutional investors who are willing to be the jerk in the room asking hard questions. It requires SAFE terms that align founder incentives with investor outcomes. Most of all, it requires acknowledging that speed and abundance have created blind spots that are costing money.

For investors who recognize this pattern and take discipline seriously, this is actually a moment of advantage. You'll be writing checks into a market where others are getting burned because they're not asking basic questions. By the time the broader market catches up, you'll have a portfolio of founders who actually followed through while everyone else is stuck on the sidelines.

For founders, the message is simpler: follow through. The easy extraction path is real, but it's temporary. Once the market corrects, credibility becomes scarce. The founders who can show that they raised capital and actually built something will be in demand. The ones who took money and disappeared will find future capital much harder to raise.

This isn't the end of the AI seed market. This is a correction in process, becoming visible in real time. The smart money is already responding with more diligence. The market will follow. Until then, be careful who you write checks to, and even more careful about the structures you accept when you're the one raising.

Key Takeaways

- Three founders raised 5M on SAFEs in 2025 and simply kept the money without building, exploiting the SAFE's lack of investor governance rights

- Reference checks were skipped in most deals due to FOMO, hot market velocity, party round structures, and investor misunderstanding of SAFE mechanics

- The AI market's acceleration enabled both hypergrowth and hyper-opportunism by the same factors: abundant capital, speed, complexity, and institutional confusion

- SAFE holders are legally creditors, not owners, until conversion occurs, giving founders zero accountability until a priced round happens

- Investors can protect themselves through institutional diligence, lead investors with skin in the game, SAFE terms with clawback provisions, and founder reference checks before wiring

- The market will self-correct over 12 months as founder extraction becomes visible, capital gets scarcer, and SAFE terms tighten, but the correction will be painful

Related Articles

- Why Thinking Machines Lab Lost Its Co-Founders to OpenAI [2025]

- Over 100 New Tech Unicorns in 2025: The Complete List [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

- Where AI Startups Win Against OpenAI: VC Insights 2025

- The Silliest Tech Moments of 2025: From Olive Oil to Identity Fraud [2025]

![The Dark Side of Hot Seed Rounds in AI: When Founders Keep the Money [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-dark-side-of-hot-seed-rounds-in-ai-when-founders-keep-th/image-1-1768491738893.jpg)