US State Department Launches Freedom.gov: The Controversial Censorship Circumvention Portal

Something unusual is happening at the intersection of American foreign policy and digital rights. The US State Department quietly began developing a web portal that could fundamentally shift how people worldwide access information their governments have blocked. The platform, hosted at freedom.gov, represents one of the most explicit government efforts to circumvent national censorship laws—and it's already sparking international controversy before its full launch.

This isn't your typical policy initiative. It's a direct challenge to the censorship frameworks that countries like Germany, France, and the United Kingdom have painstakingly built over the past decade. These nations, guided by legislation like the EU's Digital Services Act and the UK's Online Safety Act, block access to specific categories of content: hate speech, terrorist propaganda, child sexual abuse material, and election disinformation. The freedom.gov project would essentially punch holes in those walls, allowing citizens to see exactly what their governments decided they shouldn't see.

The development reveals deeper fractures in the US-European alliance. For years, American policymakers have championed digital freedom and the free flow of information as democratic ideals. Europe, meanwhile, has taken a different approach, arguing that some forms of speech cause tangible social harm and that protecting vulnerable populations sometimes requires content restrictions. These two philosophies have always existed in tension, but freedom.gov represents the first time the US government has actively built infrastructure to undermine European content policies.

What makes this situation particularly complex is the ecosystem behind it. The State Department isn't acting alone. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), part of the Department of Homeland Security, registered and administers the domain. Immigration and Customs Enforcement maintains a presence in discussions about the platform's capabilities. This multi-agency involvement suggests the project carries weight at the highest levels of government, not just the State Department's digital freedom advocates.

The timing also matters. The portal was supposed to launch publicly at the Munich Security Conference, but internal State Department resistance forced a delay. Some officials worried about the reputational consequences and the potential to poison relationships with key allies. Others questioned whether the US government should be actively helping citizens circumvent laws passed by democratic governments. These concerns didn't kill the project—they just postponed it.

Right now, freedom.gov's homepage displays a simple message: "Freedom is Coming. Information is power. Reclaim your human right to free expression. Get Ready." It's aspirational language designed to frame the platform as a tool for liberation. But beneath that messaging lies a sophisticated technical infrastructure designed to mask user identity and location, making it appear as though European citizens are connecting from the United States.

The implications spread far beyond internet access. This is fundamentally about competing visions of what the internet should be, who gets to decide what's acceptable speech, and whether any government should actively help its citizens break the laws of other democracies. The answers to those questions will shape digital policy for years to come.

The Genesis of Freedom.gov: Why the US Built This Platform

Understanding freedom.gov requires understanding America's approach to digital policy over the past two decades. The US has consistently positioned itself as the global champion of internet freedom. This isn't purely ideological—it's also practical. American tech companies benefit enormously from a permissive internet environment. The fewer restrictions governments place on content, the fewer compliance challenges US tech firms face in foreign markets.

The State Department's Digital Diplomacy office has quietly built relationships with NGOs focused on internet freedom. Organizations like Freedom House and the Reporters Without Borders have documented how authoritarian governments use content blocking to suppress dissent. The State Department extended this concern to democracies, arguing that European content policies, while well-intentioned, still constitute censorship that violates fundamental rights.

But the real catalyst came from shifting geopolitical dynamics. As the US-EU relationship cooled during the Trump administration and remained complicated afterward, digital policy became another point of friction. The EU's Digital Services Act, which mandates content moderation and transparency from large platforms, felt to American officials like regulatory overreach. The freedom.gov project evolved as a response—essentially telling Europe that if they're going to restrict content, the US will help their citizens access it anyway.

There's also a post-pandemic element here. During COVID-19, governments worldwide expanded content moderation to combat what they termed disinformation. The US government, particularly the Disinformation Governance Board (which later disbanded), became involved in flagging content it considered misleading. When Republican lawmakers attacked the board as a threat to free speech, it became politically toxic. Freedom.gov can be read as a way to reclaim the free speech mantle after that controversy.

The technical architecture reveals the sophistication of the planning. Officials discussed implementing Virtual Private Network (VPN) functionality directly into the platform. This would create a technical shield, making a visitor from Berlin appear to be accessing from Arlington, Virginia. VPNs work by routing traffic through servers in different countries, essentially hiding your real location. Building this capability into freedom.gov would mean no separate software installation required—just visit the site and instantly bypass geographic restrictions.

This technical choice matters tremendously. It suggests the State Department isn't just passively hosting blocked content. It's actively investing in circumvention technology. That's different from a privacy tool that happens to bypass censorship as a side effect. This is purpose-built infrastructure designed specifically to undermine European content policies.

The project also reflects institutional momentum within US government agencies focused on digital rights. These agencies have budgets, staff, and political support. They view content moderation in democracies as concerning, even if that moderation targets genuinely harmful content like child exploitation material. From their perspective, the internet should remain maximally open, and restrictions constitute a slippery slope toward authoritarianism.

There's a historical echo here too. During the Cold War, the US broadcast content into countries that restricted media access—Radio Free Europe, Voice of America. Those programs faced intense criticism from the Soviet bloc but were celebrated in the West as beacons of free information. Freedom.gov positions itself within that tradition, framing it as a contemporary version of information liberation.

But this comparison obscures a crucial difference. Cold War broadcasting targeted authoritarian regimes. Freedom.gov targets allied democracies that passed content policies through legitimate legislative processes. That distinction changes the ethical calculus significantly.

This timeline highlights key geopolitical and policy shifts that influenced the creation of Freedom.gov, including US-EU tensions and digital policy changes. Estimated data.

Europe's Content Moderation Framework: Why They Ban What They Ban

To understand the controversy, you need to understand what freedom.gov would let Europeans access. European governments aren't randomly censoring the internet. Their content restrictions follow specific legal frameworks with identifiable purposes.

The EU's Digital Services Act, implemented across all member states, requires platforms to remove content in several categories. Hate speech—defined as content inciting violence or discrimination based on protected characteristics—faces removal. That includes material targeting religious minorities, immigrants, or ethnic groups. The logic is straightforward: a functioning democracy requires that vulnerable groups can participate without fear of violence incited by hateful propaganda.

Terrorist propaganda faces similar restrictions. If an organization is designated as terrorist, content produced by or promoting that organization gets removed. This includes recruitment material and ideology justifications. The reasoning draws from security concerns and the devastating impact of radicalization. A 2023 study found that terrorist organizations use social media for recruitment with increasing sophistication. Content removal policies aim to disrupt that pipeline.

Child sexual abuse material (CSAM) receives absolute legal protection across all democracies. This isn't a matter of debate—CSAM involves the documented exploitation and abuse of children. Removing CSAM isn't censorship; it's protection against child abuse. Yet freedom.gov would allow access to content that every democratic government prohibits.

Election disinformation represents a newer category. After 2016 and 2020, European governments became concerned about coordinated disinformation campaigns targeting elections. The UK's Online Safety Act specifically permits removal of election interference content. These provisions target material deliberately designed to confuse voters about voting procedures, candidate backgrounds, or election legitimacy.

The Digital Services Act also addresses coordinated inauthentic behavior. This means removing networks of accounts designed to artificially amplify certain messages or manipulate public opinion. The policy recognizes that the threat to democracy comes not just from individual statements but from coordinated manipulation campaigns that distort information environments.

None of these provisions involve blocking websites for being unpopular or containing criticism of government. They target specific harmful content categories where democratic legislatures concluded that harm outweighed free speech interests. A typical removed post isn't "the government is bad"—it's content that crosses into incitement, exploitation, or disinformation.

This matters because the freedom.gov framing presents these policies as simple censorship. But the reality is more nuanced. When Germany removes content calling for violence against Muslims, that's a policy judgment that societal safety sometimes requires content restrictions. Reasonable people can disagree with that judgment, but it's not the same as censoring political opposition.

Yet European systems aren't perfect. Content moderation at scale inevitably produces errors. Legitimate speech sometimes gets removed. Algorithms make mistakes. The cultural variance also matters—what Europeans consider acceptable hate speech boundaries differ from American norms. The threshold for removal is generally lower in Europe than in the US.

That's the actual debate worth having. It's not whether any content should be restricted, but where the boundaries sit and who decides. Should governments or platforms make these judgments? Should the boundaries be narrow (only direct violence incitement) or broader (include dehumanizing speech)? These are legitimate policy questions. Freedom.gov bypasses them entirely.

Britain's Online Safety Act adds another layer. It requires platforms to protect child safety, prevent terrorism, and address illegal content. It also includes vague provisions about "legal but harmful" content, which critics argue could expand to political speech. These provisions remain contentious even within the UK. But broadly, the Online Safety Act follows similar logic to the DSA—some content causes enough harm to justify removal.

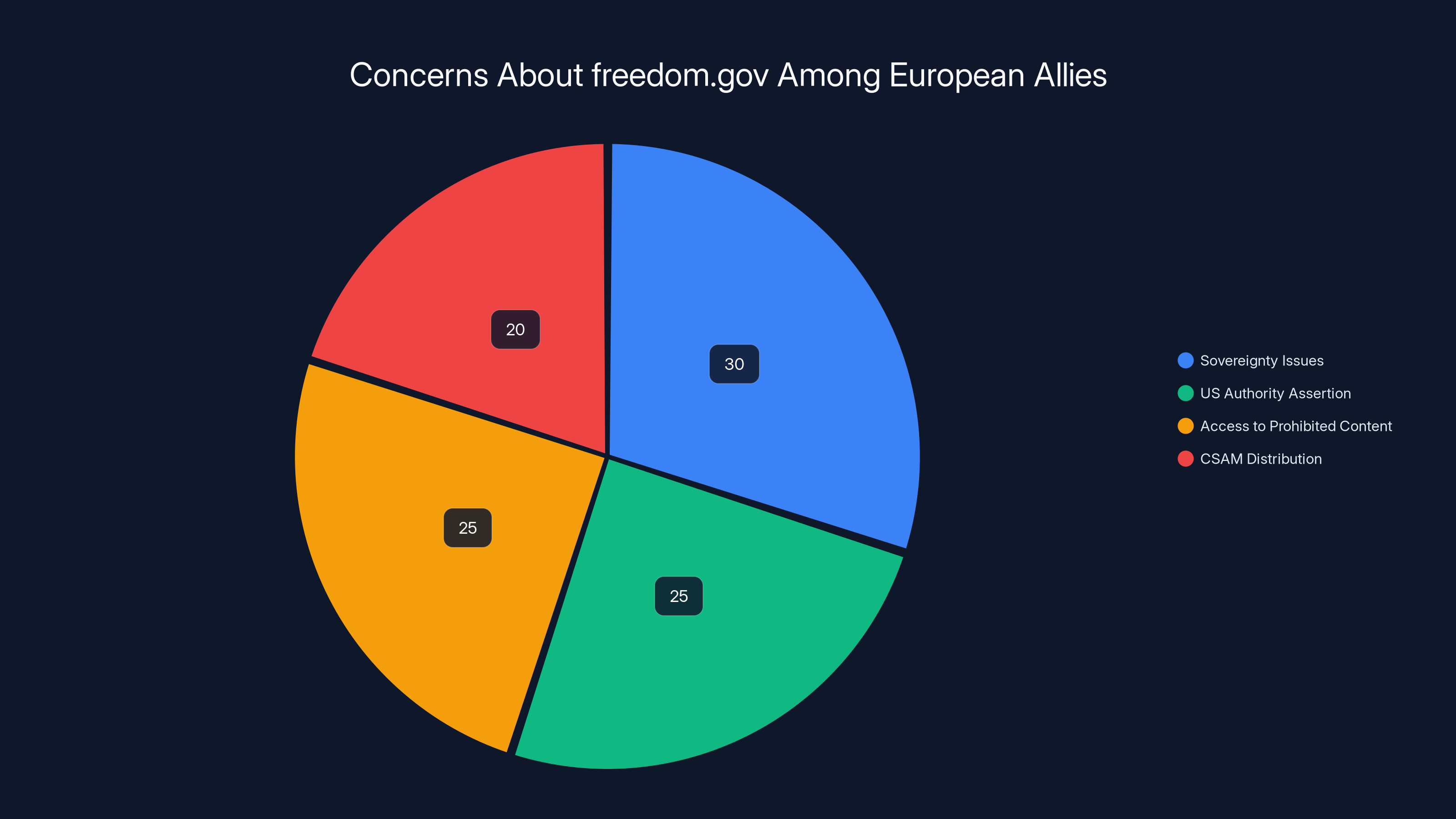

Estimated data shows sovereignty issues as the primary concern, followed by assertions of US authority and access to prohibited content, including CSAM.

The Technical Architecture: How Freedom.gov Would Actually Work

The proposed technical implementation of freedom.gov reveals how seriously the State Department approached this project. This isn't a simple directory of blocked content or a list of URLs. It's designed as an active circumvention tool with multiple layers of technical sophistication.

The VPN functionality represents the core innovation. A VPN operates by encrypting your traffic and routing it through a server in another country. When you connect to a VPN in the US, websites see your traffic as originating from the US rather than your actual location. For Europeans, this means they could visit freedom.gov, connect through its built-in VPN, and instantly appear to be in America. Geographic restrictions disappear because the technical infrastructure makes geographic information irrelevant.

This is different from traditional VPN applications you download and install. Those require technical sophistication—finding a reliable VPN service, installing software, managing encryption keys, troubleshooting connection issues. Freedom.gov would integrate VPN functionality directly into the website. You wouldn't need any software. You wouldn't need technical knowledge. Visit the site and the circumvention happens automatically.

From a technical standpoint, this requires substantial infrastructure. Freedom.gov would need to host servers that handle encryption, route traffic to origin servers, and manage the traffic volume. Thousands of simultaneous users could overwhelm a standard web server. The State Department would need to architect a distributed system, possibly using Content Delivery Networks to handle traffic in multiple regions.

Security becomes another consideration. A VPN system that routes all user traffic through government servers creates both privacy opportunities and vulnerabilities. On one hand, it hides user identity from the websites they visit. On the other hand, it concentrates that traffic on US government infrastructure. If the VPN server gets compromised, an attacker could theoretically monitor all user activity.

The actual implementation would likely follow established patterns. Tor, the anonymity network used for uncensored communication, operates through multiple layers of encryption. A simplified version could power freedom.gov. Users connect to an entry node, which connects to several relay nodes, which finally connects to an exit node that makes the actual request. This layering means no single point of visibility into user activity.

But building this requires significant resources and expertise. You need people who understand cryptography, network protocols, distributed systems, and security. The US government has that expertise within military and intelligence agencies. Repurposing it for freedom.gov makes sense logistically but raises questions about the military-surveillance establishment's involvement in a platform that frames itself as defending human rights.

The technical architecture also requires handling the content itself. Freedom.gov would need to host or access the material that European governments blocked. For simple things like articles or documents, that means storing copies on US servers. But for dynamically generated content or streams, more complex mirroring would be required. Some platforms might actively prevent mirroring through technical means, forcing the State Department to find workarounds.

Traffic patterns would reveal another challenge. If thousands of German users suddenly access American IP addresses, that's noticeable to network administrators and potentially to intelligence agencies. The anonymization helps, but large-scale circumvention creates detectable patterns. European governments watching network traffic could identify users accessing freedom.gov and potentially take action against them, unless the portal's own users implement additional privacy measures.

The practical reality is that building this requires operational security normally associated with intelligence operations. You need redundant systems. You need failovers if parts get taken down. You need ways to update content and security patches without revealing infrastructure details. This infrastructure exists within government agencies, but deploying it for what's nominally a public website suggests coordination across security and diplomatic apparatus.

Maintaining the platform adds another layer of complexity. Content removal policies change constantly as governments update laws. New blocking categories emerge. Freedom.gov would need to track these changes and update its content library accordingly. That requires staff monitoring global content policy, analyzing new regulations, and updating the platform's systems. Again, this speaks to the resource commitment and institutional seriousness behind the project.

The Geopolitical Backlash: Why Allies Are Concerned

When word leaked about freedom.gov, European officials responded with alarm. This wasn't skepticism about the project's technical merits. It was fundamental concern about what the project signals about the US-European relationship and the future of digital cooperation.

The most direct concern involves sovereignty. Countries enact content policies as expressions of democratic will. Germany's hate speech laws reflect German history and German values. The UK's Online Safety Act represents British judgment about how to balance free expression with other social goods. When the US government builds infrastructure specifically designed to circumvent those policies, it's telling allied democracies that their legal frameworks don't deserve respect.

This is particularly sensitive because it comes from a US administration that has emphasized putting America first and questioning the value of international alliances. Building freedom.gov looks less like "defending human rights" and more like "asserting American authority over global internet governance." From the European perspective, it suggests the US wants a world where American values override locally enacted laws.

Nina Jankowicz, the former executive director of the Homeland Security's Disinformation Governance Board, articulated the most inflammatory concern: freedom.gov would help Europeans access hate speech, pornography, and child sexual abuse material. Even if that's not the project's stated goal, those would be side effects. Users might access the portal for content they consider valuable but encounter hate speech along the way. Or they might deliberately seek out prohibited content for reasons the State Department doesn't endorse.

The focus on CSAM is particularly significant. No government wants its infrastructure used to distribute child exploitation material. The fact that freedom.gov's broad approach to circumvention would make CSAM accessible represents a genuine ethical problem, regardless of the platform's intentions. European governments can't simply accept that this is acceptable collateral damage in the name of free speech.

There's also a retaliation risk that nobody discusses publicly but everyone understands. If the US builds infrastructure circumventing European laws, what prevents European governments from building equivalent infrastructure circumventing US laws? The US has hate speech protections that virtually no other democracy has. Imagine if Germany built a portal allowing Americans to access content violating US laws about things like election interference in foreign elections. The reciprocal logic suggests digital warfare.

Tech companies operating in Europe express concern too. They've invested substantial resources in compliance with GDPR, the DSA, and national laws. If users access prohibited content through freedom.gov, does the platform bear responsibility? Do the original platforms? What about companies that facilitate access to freedom.gov? The legal gray areas multiply.

There's also concern about what freedom.gov signals for digital policy generally. If the US government openly circumvents content policies, what leverage does it have when negotiating trade agreements or tech regulation? The project basically says "we don't respect European content law," which undermines any claim that the US cares about rules-based international order in digital space.

Inside the State Department itself, resistance emerged from diplomats who understand the relationship costs. Munich Security Conference attendees who heard about the plan reportedly expressed concern. European intelligence officials let American counterparts know this would damage trust. The State Department delayed launch specifically because officials worried about these diplomatic consequences.

But there's no fundamental resolution to this tension. Either the US believes that digital freedom overrides national content policies, or it doesn't. Either it respects European legal frameworks, or it doesn't. Freedom.gov represents a clear answer: digital freedom, as America defines it, overrides European legal frameworks.

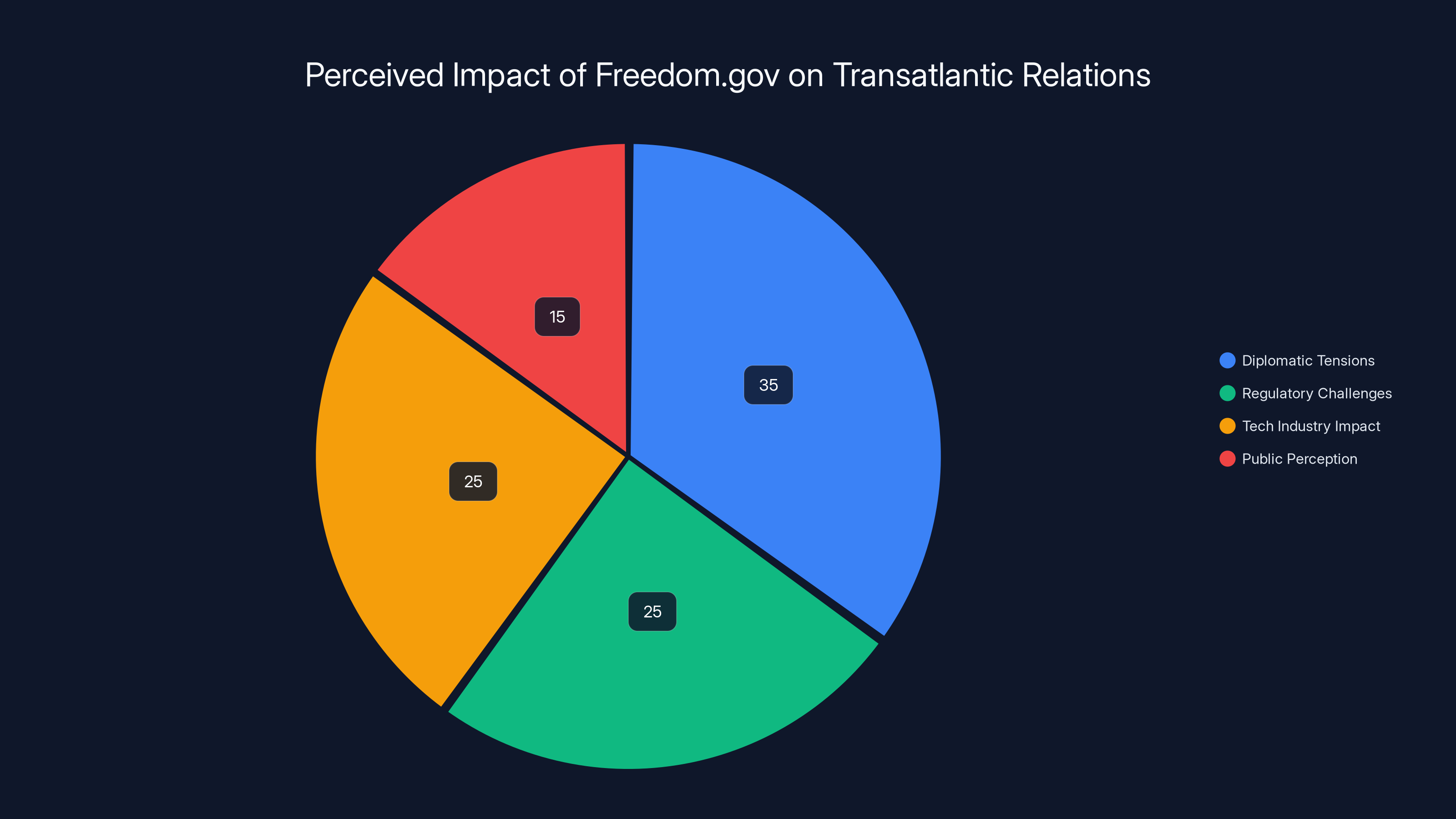

Freedom.gov is estimated to have the greatest impact on diplomatic tensions (35%), followed by regulatory challenges and tech industry impact (25% each), with public perception being least affected (15%). Estimated data based on narrative insights.

The Free Speech Argument: America's Counter-Position

The US position isn't unreasonable, even if its implementation through freedom.gov is controversial. The argument goes like this: free speech is fundamental to human dignity and democratic societies. Governments that restrict speech, even for well-intentioned reasons, inevitably expand those restrictions over time. Today's "hate speech" becomes tomorrow's "opposition to government policy." The only safe approach is maximum permissiveness.

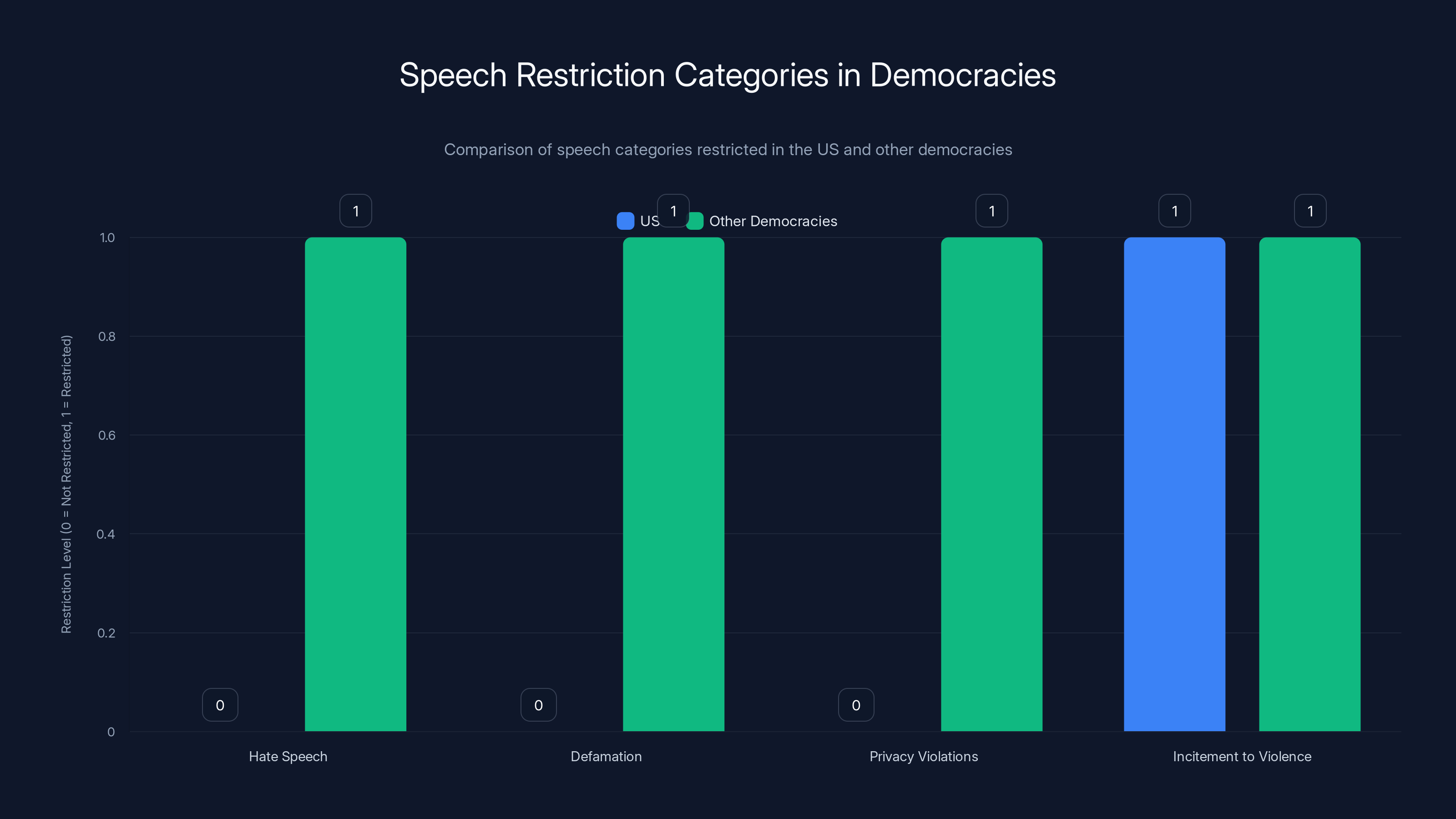

This reflects America's unique constitutional tradition. The First Amendment, interpreted very broadly by US courts, permits almost all speech except direct incitement to imminent violence. This isn't universally shared. Many democracies recognize additional speech categories that can be restricted—hate speech, defamation, privacy violations. The US treats these as acceptable speech subject to civil liability but not criminal prohibition.

The American perspective draws from historical experience. The US government famously sought to suppress various speech—civil rights advocacy, anti-war protest, radical labor organizing. That suppression was wrong, and society benefited when it ended. This history makes Americans skeptical of any government authority to restrict speech. If you give governments power to block harmful speech, that power will be abused.

That skepticism isn't unreasonable. European hate speech laws have faced criticism from scholars and rights organizations. Amanda Knox, the American student convicted in Italy, faced conviction partly based on how Italian law treats speech about sexual assault. That example shows how different legal frameworks can produce outcomes that seem unjust from an American perspective. If you trust your own legal system but not others', restricting speech seems risky.

Furthermore, content moderation has real costs. When platforms remove content, they sometimes remove legitimate speech as collateral damage. Machine learning systems make mistakes. Human moderators have biases. The more broadly you define prohibited categories, the more legitimate speech gets swept up. From this viewpoint, the safest approach is restricting removal to the narrowest possible categories.

There's also the point about slippery slopes. Britain's Online Safety Act includes language about "legal but harmful" content. That provision is genuinely concerning because "harmful" is subjective. Today's harmful content might be tomorrow's political opposition. Germany's Netz DG law, which penalizes platforms for insufficient hate speech removal, has been criticized for pressuring overly aggressive moderation. These examples show that even well-intentioned frameworks can expand in problematic directions.

The American position also draws from tech industry values. Silicon Valley companies that built the modern internet embraced permissiveness as a design principle. They believed maximum openness would create innovation and connection. While that philosophy had real benefits, it also enabled harassment, misinformation, and extremism. But the tech industry remains largely committed to permissiveness, and that perspective influences US policy.

The State Department's position is that digital rights are human rights, and governments restricting content violate those rights. This connects to UN documents and international frameworks that protect freedom of expression. From this viewpoint, the US isn't just defending abstract principles—it's defending human rights as understood by the international community.

But there's a tension within this argument. The US government cracks down on misinformation, particularly election interference. The Disinformation Governance Board, though short-lived, represented an effort to restrict false information about elections. That suggests the US does believe governments should sometimes restrict speech, just in different categories than Europe does.

The actual difference is narrower than freedom.gov's framing suggests. Both the US and Europe restrict speech in certain categories. Both believe some content causes enough harm to justify removal. They disagree about where the line sits and who decides. The US is willing to tolerate hate speech in pursuit of broad permissiveness. Europe is willing to restrict hate speech in pursuit of protecting vulnerable groups. Both positions have merit and drawbacks.

What freedom.gov does is collapse this nuanced discussion into a simple narrative: freedom versus censorship. That rhetorical move enables the project but obscures the actual disagreement, which is about how much speech can be restricted without enabling authoritarianism.

What Freedom.gov Would Actually Let People Access

Understanding the controversy requires being concrete about what freedom.gov would provide access to. The project isn't just about high-minded free speech principles. It would let users access actual content that European governments have determined causes harm.

Hate speech represents a significant portion of removed content. This includes material characterizing immigrants as a threat to national identity, content suggesting religious minorities are conspirators against the nation, and material depicting certain ethnic groups as inherently inferior. Not all of this is obscure—major politicians in various European countries produce hate speech that violates local laws but wouldn't be illegal in the US.

Marine Le Pen, the French far-right politician, has produced content that violates France's hate speech laws but would be protected speech in the US. Hungary's Viktor Orban has made speeches about replacement theory—the conspiracy theory that European countries are intentionally replacing white populations with immigrants—that constitute hate speech under EU law but are commonplace in American political discourse.

Freedom.gov would let Europeans access that content. Someone in Paris could use the platform to watch speeches that the French government determined violate hate speech law. The State Department apparently believes that right outweighs the harm of that content's circulation.

Terrorist propaganda represents another major category. This includes recruitment material, ideological writings, and training content produced by organizations designated as terrorist. Some of this is extremely explicit—detailed instructions for violence, calls to join armed groups, propaganda glorifying attacks. European governments remove this content believing it facilitates recruitment and violence.

Freedom.gov would make that content accessible. A radicalized individual in the UK could access ISIS propaganda through the platform. A German citizen could access content from prohibited far-right extremist groups. Again, this isn't incidental—the State Department is consciously building infrastructure that would facilitate access to this material.

The CSAM issue deserves specific attention because it's qualitatively different. European governments don't remove CSAM because they believe it's objectionable speech. They remove it because each image represents documented child abuse. The children in those images were harmed. Making that material accessible means perpetuating and profiting from that harm.

No honest framing of freedom.gov can avoid this reality. The platform would make CSAM more accessible. Users could bypass protections that every democratic government implemented to prevent distribution of child exploitation material. The State Department's response is essentially that this is acceptable collateral damage in pursuit of broader digital freedom.

Election interference content is worth examining too. This includes material spreading false information about voting procedures, candidate backgrounds, or election legitimacy. Some examples are crude—completely false claims about how to vote. Others are more sophisticated—accurate information about one candidate paired with misleading context suggesting malfeasance.

Freedom.gov would let Europeans access this content. A German could use the platform to see content the German government determined was election interference. During election season, political operatives could circulate content through freedom.gov that would otherwise be removed. Again, the State Department apparently believes access to election interference content outweighs the harm of election manipulation.

There's also content in gray areas—material that violates European content policies but has arguable speech value. Conspiracy theories about political figures, content that's dehumanizing but not quite hate speech, material that's misleading but not provably false. Freedom.gov would give Europeans access to this entire spectrum.

The cumulative effect is significant. Freedom.gov wouldn't just be a tool for accessing suppressed political speech. It would be a comprehensive vehicle for accessing content that democracies have determined is sufficiently harmful to restrict. The State Department's position is that access to that content matters more than preventing its harm.

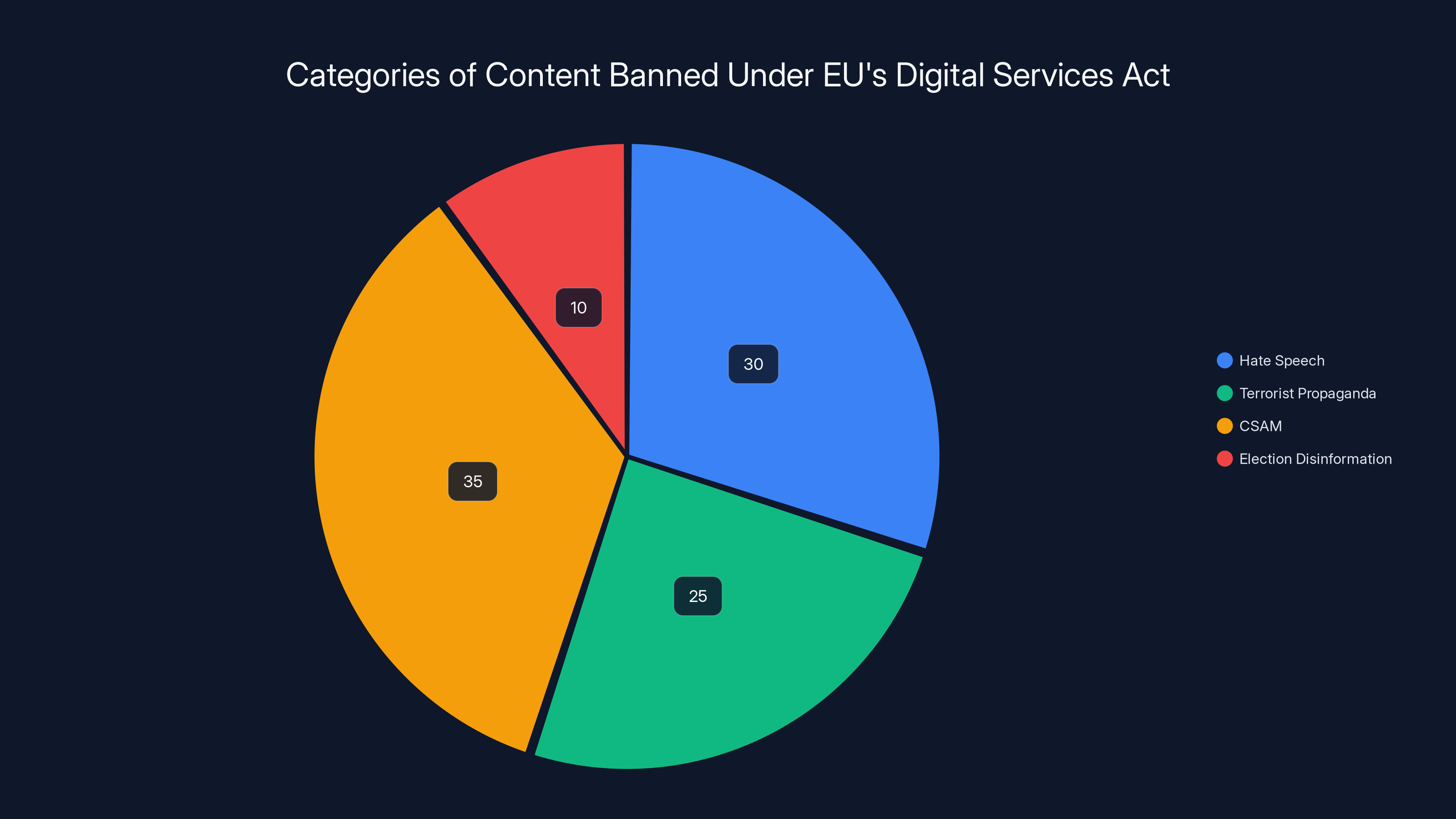

Estimated data suggests that CSAM and hate speech are the most targeted categories under the EU's Digital Services Act, reflecting priorities in protecting vulnerable groups and children.

The Regulatory Context: Why Europe Enacted These Laws

European content policies didn't emerge in a vacuum. They developed in response to specific historical events and documented harms. Understanding those origins helps explain why Europeans view freedom.gov not as defending freedom but as enabling harm.

Hate speech laws in Germany and Austria trace directly to the Holocaust. These countries saw how dehumanizing propaganda preceded genocide. Their view, shaped by devastating historical experience, is that allowing unlimited hate speech creates conditions for the violence that follows. German law specifically targets speech that dehumanizes groups or encourages discrimination based on protected characteristics.

This isn't an abstract concern for Germany. The country has experienced violence targeting immigrants, religious minorities, and political opponents. Neo-Nazi groups have committed murders. Dehumanizing content contributed to that violence. From the German perspective, restricting hate speech is how you prevent that history from repeating.

Britain's Online Safety Act developed partly in response to social media-facilitated harassment and terrorism. The 2017 Manchester bombing was preceded by digital radicalization. Young British citizens were accessing extremist content online and being recruited to violence. The Online Safety Act's requirement that platforms prevent terrorism reflects the experience of that radicalization process.

The EU's focus on coordinated inauthentic behavior emerged from documented election interference. Russia's Internet Research Agency manipulated social media to influence the 2016 US election and various European elections. European governments saw how coordinated bot networks and troll accounts could distort information environments and manipulate voters. From their perspective, removing coordinated manipulation is how you protect election integrity.

CSAM restrictions emerged from law enforcement's experience with exploitation networks. Online platforms enabled global distribution of abuse material and created new demand for abuse content. Countries discovered that removing CSAM was necessary to disrupt the economic incentives for continued abuse. This isn't political—it's a direct response to how technology enabled child exploitation.

The disinformation focus intensified during COVID-19. False information about vaccines, treatments, and virus origins circulated rapidly and caused real harm. Millions of people died from preventable disease partly because they believed false information. European governments responded by requiring platforms to remove medically dangerous misinformation. Again, this reflects documented harm, not censorship of legitimate opinion.

There's also a structural reason for European content policies. The EU is multicultural in ways the US isn't. Germany has a large Turkish diaspora. France has a significant North African Muslim population. Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden host substantial immigrant communities. In such contexts, speech that dehumanizes minorities or incites discrimination against them has direct impact on people's ability to participate in society.

Compare this to the US, where the First Amendment means you can't legally restrict hate speech, yet the US still experiences violence against minorities fueled by hateful rhetoric. The difference is constitutional tradition, not absence of hate speech. European governments looked at the US and saw hate speech without legal remedy and concluded that wasn't a model worth replicating.

What's crucial to understand is that these policies passed through democratic processes. German hate speech law didn't emerge from authoritarian decree. Germans debated it, voted on it, and elected representatives who supported it. Same with Britain's Online Safety Act, the DSA, and other European content frameworks. These aren't paternalistic restrictions imposed by unelected bureaucrats. They're laws that democratic societies chose.

This matters because it undermines the simple narrative that freedom.gov opposes. Freedom.gov frames its mission as defending human rights against authoritarian censorship. But European content policies aren't authoritarian. They're democratic choices about how to balance competing interests. The fact that Americans would make different choices doesn't make European choices inherently illegitimate.

The State Department's Official Position and Non-Defense

When asked directly about freedom.gov, the State Department offered a carefully worded response that's illuminating in what it doesn't say. The department denied having "a program specifically meant to circumvent censorship in Europe." That precise language is important because it technically accurate while avoiding the substance of the complaint.

The State Department can truthfully say that freedom.gov isn't specifically focused on Europe. The platform would be available globally. Anyone anywhere could use it to access content their government blocked. The platform isn't exclusively designed to undermine European policy—it's designed to undermine all government content policies.

But that's a narrow defense. The factual claims about freedom.gov—that it would include VPN functionality, that it would let users bypass geographic restrictions, that European authorities were concerned about it—don't get disputed. The department instead offers a different framing: digital freedom is a priority, including "privacy and censorship-circumvention technologies like VPNs."

This phrasing is strategically interesting. It groups VPNs with privacy tools and frames both as democratic goods. That's not dishonest—VPNs do provide privacy. But it elides that freedom.gov would be specifically designed to defeat content policies, not just provide privacy generally.

The State Department spokesperson also doesn't defend freedom.gov's specific contents. When asked about child exploitation material or terrorist propaganda becoming accessible, the department doesn't argue that such access is fine. It simply doesn't engage with the question. Instead, it reframes to abstract language about digital freedom and privacy.

That rhetorical move is common in government communications. When you can't defend the concrete implications of your policy, you move to more abstract language. Freedom.gov's concrete implication is that terrorist propaganda and child exploitation material would become more accessible. That's difficult to defend. So instead, the conversation becomes about "digital freedom" in the abstract.

The state department's non-defense is also revealing in another way: it doesn't claim that the specific content concerns are wrong. It doesn't argue that hate speech isn't actually hate speech or that CSAM concerns are overblown. It doesn't defend the specific harms that freedom.gov would enable. It just pivots to broader themes.

What the statement does do is place digital freedom alongside privacy as equivalent goods. From the State Department's perspective, accessing content and protecting privacy are both democratic values that should be protected. The European perspective would be that these values sometimes conflict—you might need to restrict access to some content to protect vulnerable populations.

The State Department's statement essentially says the US prioritizes access to information over protection from harmful content. That's a legitimate position, but it's not the only legitimate position. European democracies prioritize protection from demonstrable harms—hate speech violence, child exploitation, election interference. They've concluded that restricting access to content causing such harms is justified.

What's notably absent from the State Department's response is engagement with why European democracies enacted these policies. There's no acknowledgment that Germany, France, and Britain made deliberate choices based on their experiences and values. There's no argument that those choices were wrong in a substantive way. Instead, there's just a reassertion of American values about digital freedom without engaging with the actual disagreement.

This pattern has been consistent throughout freedom.gov's development and limited disclosure. When European officials express concern, the US response is to reassert the value of digital freedom rather than directly address the content concerns. That rhetorical move allows the conversation to stay at the level of principles while avoiding specifics that would be difficult to defend.

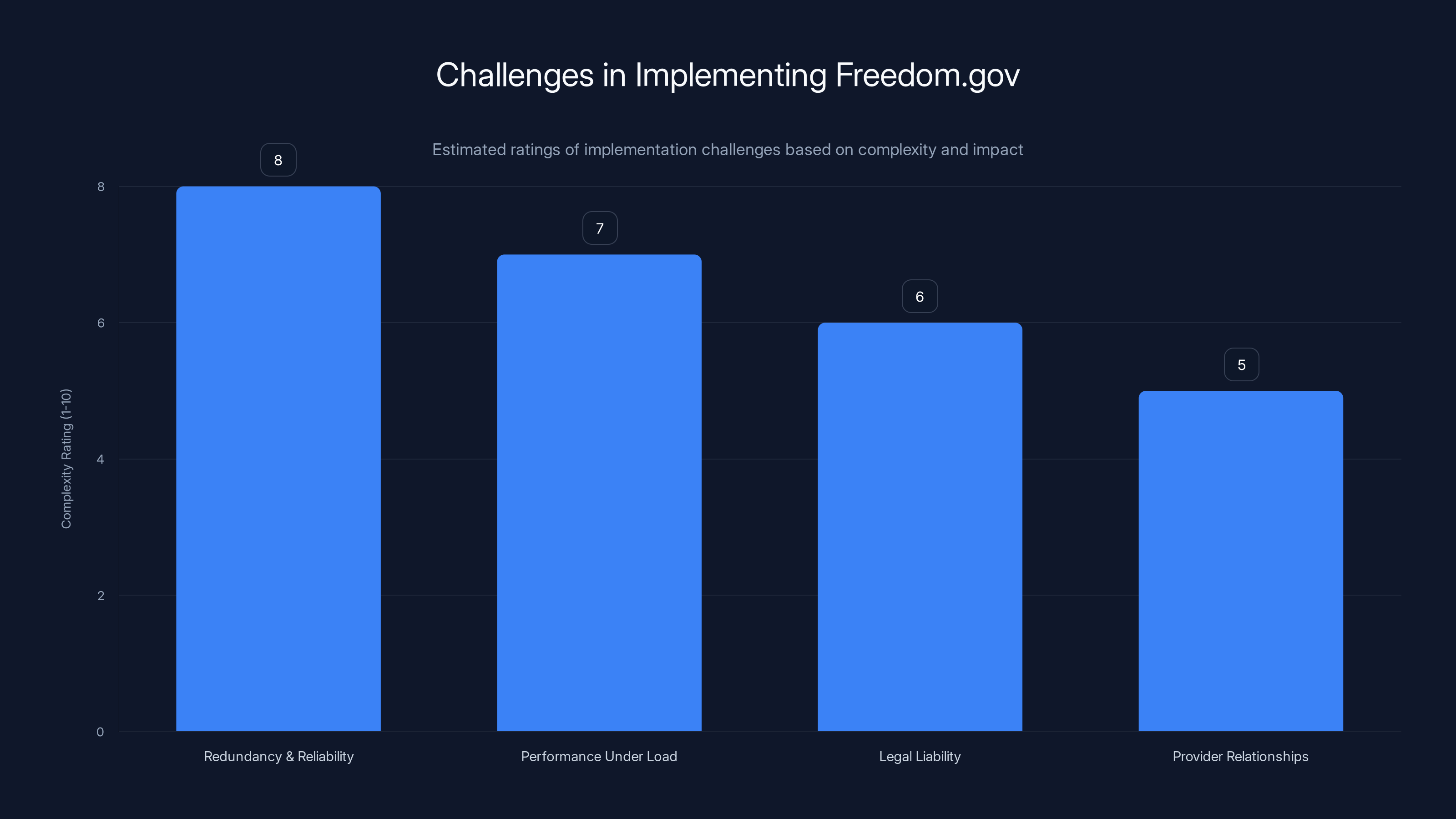

The chart illustrates the estimated complexity of key challenges in implementing freedom.gov, highlighting redundancy and reliability as the most complex issue. Estimated data.

Implications for the Transatlantic Relationship

Freedom.gov represents a significant moment in US-European relations that goes beyond digital policy. It signals fundamental disagreement about the future direction of technology governance and the respect various governments have for each other's democratic choices.

At the surface level, it damages the specific diplomatic relationship. When the US government builds infrastructure specifically designed to circumvent another country's laws, that other country takes it personally. Diplomacy requires accepting that allies will make different choices sometimes. But it also requires not actively undermining those choices through government action.

European leaders invested significant political capital in the DSA and Online Safety Act. These regulations faced opposition from tech companies and libertarian voices arguing they would stifle innovation. European governments chose consumer protection over tech industry interests. That was a specific democratic choice. When the US government then builds infrastructure to circumvent those policies, it's basically telling Europe that its democratic choices don't matter.

The timing makes this worse. The Trump administration has questioned the value of NATO and trans-Atlantic cooperation. Freedom.gov, whether intentionally or not, comes across as the US asserting unilateral authority over digital rights, disregarding European input. From a European perspective, this fits a pattern of American digital exceptionalism.

There are also practical consequences for tech companies. These firms operate globally and must comply with laws in multiple jurisdictions. They've invested in DSA and Online Safety Act compliance. Freedom.gov creates a situation where government-hosted infrastructure circumvents the very policies companies must comply with. That increases regulatory uncertainty and compliance costs.

One second-order effect is that it gives other governments justification for their own content policies. If the US can argue that digital freedom overrides national laws, Russian and Chinese governments can use equivalent logic for their own content restrictions. They can say, "The US government doesn't respect other countries' content policies, so why should we?" Freedom.gov, paradoxically, could weaken the case against authoritarian censorship.

There's also a precedent concern. If the US government can build a portal circumventing content laws, why can't China build one promoting different content? Why can't Russia build one circumventing EU sanctions on Russian media? The absence of universal rules means any government can justify its own digital actions. Freedom.gov tips the balance toward a world of digital conflict rather than digital cooperation.

Internally in Europe, freedom.gov creates political problems for European leadership. Centrist European politicians who've invested in trans-Atlantic cooperation now have to explain why the US is actively undermining European law. Right-wing populists can point to freedom.gov as evidence that the US can't be trusted to respect European sovereignty. This plays into narratives about American digital imperialism that weaken pro-American sentiment.

For American intelligence and security agencies, freedom.gov also creates some problematic dynamics. European intelligence services have traditionally shared information with US counterparts partly because they assumed shared commitment to democratic values. If the US government is helping people access terrorist propaganda and child exploitation material, that makes intelligence sharing more complicated. Why would you share terrorism intelligence with a government that's helping people access extremist content?

The long-term relationship risk is that Europe accelerates digital autonomy and decoupling. The EU is already investing in digital sovereignty initiatives and trying to reduce dependence on US technology. Freedom.gov contributes to the argument that Europe can't rely on the US to respect European values and choices. That accelerates investment in European tech infrastructure and reduces US tech companies' access to European markets.

In some ways, freedom.gov represents the logic of digital conflict rather than digital cooperation. It assumes zero-sum competition over what the internet should be rather than negotiation and compromise. That assumption might be increasingly accurate, but freedom.gov advances it while claiming to defend universal principles.

The Disinformation Governance Board Connection: Context and Criticism

The fact that freedom.gov emerged from agencies that included former Disinformation Governance Board officials provides important context. The board was briefly controversial and was ultimately shut down, and freedom.gov partially represents how those officials are pursuing similar goals through different mechanisms.

The Disinformation Governance Board, created in 2022, was intended to combat false information that could harm national security. The board's mission included monitoring Russian disinformation campaigns, coordinating government responses to false information, and raising awareness about disinformation threats. These are reasonable goals that most democracies undertake through various agencies.

But the board became controversial because it seemed to blur the line between combating false information from foreign actors and countering domestic speech the government disliked. When Republicans learned about the board, they quickly attacked it as the government's "Ministry of Truth." The board became a symbol of government overreach into free speech.

Nina Jankowicz, the board's director, faced particularly intense criticism. She had previously tweeted about Hunter Biden's laptop in ways critics felt were partisan. Her appointment thus looked to conservatives like the government placing a Democratic partisan in charge of determining what counted as disinformation. The board lost political support rapidly and was shut down within a few months.

But the underlying concern—coordinating responses to disinformation—didn't disappear. It just got dispersed across other agencies. Freedom.gov can be read as an attempt to pursue the same goals—protecting Americans and democratic allies from harmful false information—through a different mechanism. Instead of the government determining what's false and countering it, freedom.gov provides access to information European governments restricted.

The shift is from government deciding what's true to government providing access to contested information and letting citizens decide. That's more ideologically consistent with American free speech values. But it also means ceding to other governments the authority to determine what's harmful, then building infrastructure to undermine their determinations.

What's interesting is that this represents a kind of ideological resolution of the disinformation board controversy. Conservatives attacked the board for giving government power to determine what's false. Freedom.gov bypasses government determination entirely—it assumes individuals should access all information and decide themselves. That's more permissive but requires much less government authority over speech.

This also explains why some State Department officials were concerned about freedom.gov. Officials who had defended the Disinformation Governance Board wanted to preserve some government role in addressing harmful information. Freedom.gov's approach of pure access without discrimination felt to them like ceding too much ground.

The political economy matters here. Disinformation Governance Board officials and their supporters in the bureaucracy had political support from the Biden administration but faced congressional opposition and public skepticism. Freedom.gov allowed those officials to continue pursuing digital policy goals while avoiding the political vulnerabilities that killed the board. It's government reshaping its approach in response to political feedback while maintaining core objectives.

The historical sequence also shows that concerns about false information and its harms didn't disappear when the Disinformation Governance Board shut down. The concerns were always legitimate—governments worldwide do experience disinformation campaigns. The problem was institutional design and the appearance of government overreach. Freedom.gov represents an answer to that institutional problem: don't have government curate information; just provide access to everything and trust people to sort it out.

But this answer has its own institutional problems. It assumes that access to information is sufficient to counter disinformation. Research shows that's not always true. People often believe false information that confirms their biases and dismiss accurate information that contradicts them. Merely providing access to content doesn't mean people will believe it or that false information won't spread.

Freedom.gov thus represents a shift in how the US government approaches information problems, but not a solution to them. The shift is from government curation to government provision of access. Whether that's more effective at addressing the actual harms of disinformation is unclear and untested.

The US restricts fewer speech categories compared to other democracies, primarily limiting only direct incitement to violence.

Technical Feasibility and Implementation Challenges

While the technical architecture of freedom.gov is conceptually straightforward, implementing it at scale presents genuine challenges that would shape how the project actually works.

The first challenge is redundancy and reliability. Any system designed to help people circumvent government blocking needs to be reliable. If freedom.gov goes down or experiences outages, users can't access it when they need it most. This means building redundant infrastructure across multiple data centers and geographic regions. The State Department would need backup systems and failover capabilities. This infrastructure is expensive and operationally complex.

Performance under load represents another challenge. If thousands of users simultaneously connect through freedom.gov, the infrastructure needs to handle that load without degradation. Each encrypted connection consumes resources. Routing traffic through multiple relay systems adds latency. The user experience could degrade significantly under high load, making the platform unreliable precisely when most needed.

Legal liability creates another layer of complexity. If terrorist organizations use freedom.gov to distribute propaganda and someone is radicalized and commits violence, is the US government liable? The government has some legal immunity for hosting content, but that immunity might not extend to hosting content specifically designed to circumvent foreign laws. The legal theories here are untested.

Relationships with internet infrastructure providers create practical problems too. Internet service providers, cloud hosting companies, and network carriers could refuse to carry traffic to freedom.gov or route it through their systems. They might face pressure from foreign governments or face legal liability themselves. The State Department would need secure infrastructure that major providers can't easily interfere with.

Content management at scale adds operational burden. Someone needs to monitor what content becomes newly blocked in which jurisdictions, verify that freedom.gov has access to that content, and ensure the platform stays current. This requires staff monitoring global content policy, understanding different legal frameworks, and managing the platform's content library.

Security becomes increasingly difficult with higher stakes. If a foreign government wants to compromise freedom.gov's infrastructure to track users, the incentives are substantial. The State Department would need security practices normally associated with classified systems. That might mean air-gapped networks, offline backups, and security protocols that reduce the platform's usability.

User verification creates an interesting problem. Should freedom.gov verify that users are actually from countries with content restrictions? Or should it be globally available? If it requires verification, that means infrastructure to verify identity, creating privacy risks. If it's globally available, it becomes a general circumvention tool, not specifically a response to censorship.

Financial sustainability is worth considering too. Maintaining this infrastructure costs significant money annually. Does the State Department budget for indefinite maintenance? What happens if funding gets cut? Does the platform get shut down, leaving users suddenly without access? Or do they transition it to another agency or NGO? The long-term financial model isn't clear.

Scaling to global demand also means facing political pressure in multiple countries. China, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and others would likely demand that the US take down the platform or risk diplomatic consequences. The US would have to decide how committed it is to freedom.gov when faced with that pressure.

The Path Forward: Will Freedom.gov Actually Launch?

Given the delay and internal opposition, whether freedom.gov actually reaches public launch remains uncertain. The project has momentum from multiple US agencies, but it faces real resistance internally and internationally.

The strongest indicator that something happens is that multiple agencies are invested. CISA has registered the domain and likely allocated resources. The State Department has made public statements suggesting the project is real. These aren't just idea-stage concepts—they're resource commitments by major government agencies.

But the diplomatic pushback is also real. European officials have made clear that freedom.gov would significantly damage relationships. That matters because the State Department cares about diplomatic relationships. If the cost to the relationship outweighs the perceived benefit, officials might shelve the project indefinitely while maintaining the appearance that work continues.

The political environment affects this too. If the US elects leadership less committed to challenging Europe or more focused on other priorities, freedom.gov could quietly get de-prioritized. Bureaucratic projects can exist in zombie states—not officially canceled, just not actively developed—for years.

One possibility is a compromise. Maybe the platform launches but focuses on specific content categories rather than a broad approach. Perhaps it makes available political content and news that got blocked, while excluding terrorist propaganda and CSAM. That would be less controversial while still providing a tool for accessing censored information.

Another possibility is that it launches quietly in a limited form—available in some regions but not widely advertised. This would allow it to exist without massive diplomatic fallout. Users who know about it could access it; but without official promotion, it wouldn't face intense scrutiny.

The most likely scenario, based on current momentum and the structure of government decision-making, is that something launches but in a limited form. Perhaps the initial version is narrowly focused on political content. Perhaps it launches in limited geographic regions. Perhaps it includes technical limitations—maybe the VPN isn't fully implemented, or access isn't universal.

But a full public launch with complete functionality and global availability faces obstacles that might prevent it. The diplomatic costs are substantial. The technical challenges are real. The internal opposition is documented. The ethical concerns about CSAM access are difficult to overcome even for those committed to the project.

What's already happened is that freedom.gov has changed the conversation about digital rights and government authority. The project's existence, even unreleased, signals US government thinking about these issues. It's influenced how other countries think about US tech policy. The platform's reputational effect might exceed its practical effect.

For people concerned about digital rights and access to information, the question isn't just whether freedom.gov launches. It's whether its general approach—that access should be prioritized over harm prevention—becomes dominant in policy. The existence of the project suggests that trend is already happening, regardless of whether freedom.gov itself goes public.

Policy Implications for the Future of Digital Governance

Freedom.gov represents more than a single platform. It signals the direction of US digital policy and raises questions about how nations will govern the internet going forward.

One implication is that nations will face increasing pressure to choose between compatibility with US digital values and implementation of their own content policies. If the US makes accessing all content a priority through platforms like freedom.gov, it becomes difficult for other countries to maintain content restrictions without appearing to oppose freedom. That's a form of soft power—using the framing of free speech to constrain other governments' policy choices.

Another implication is that digital governance will increasingly become state-to-state conflict rather than negotiation. If the US builds platforms circumventing other countries' laws, those countries will build equivalent responses. You get digital tit-for-tat where each government tries to undermine others' policies. That fragmentation makes the internet less unified and less accessible.

There are also implications for how governments and tech companies relate. If governments start building their own infrastructure to circumvent policies other governments enact, companies face impossible compliance burdens. Do they comply with content policies that the US government is actively circumventing? Which government's rules matter more? The lack of clarity drives companies toward localization and fragmentation.

The precedent freedom.gov sets matters too. If it's acceptable for the US government to build tools circumventing European law, what other tools are acceptable? Could the US build platforms distributing content that violates sanctions? Could it build platforms violating other countries' laws? Without clear principles about what's acceptable, freedom.gov opens a door that other governments will walk through in ways the US might not like.

For actual internet users in censorship-prone regions, freedom.gov might create more problems than solutions. The existence of a US government-backed circumvention tool could provide justification for more aggressive government crackdowns in authoritarian countries. "See, the US is helping people circumvent national security laws," becomes an argument for more surveillance and control.

There's also an implication for how nation-states approach digital sovereignty. The EU is already investing in digital infrastructure autonomy. Freedom.gov strengthens the case for Europe to build its own internet infrastructure independent of US control. That fragmentation might be inevitable, but freedom.gov accelerates it.

Going forward, expect more government-built tools designed to circumvent other governments' policies. Expect more conflict over what the internet should be. Expect continued divergence between the US model of maximum permissiveness and the European model of regulated access. Freedom.gov is one data point in this larger trend, not a unique anomaly.

FAQ

What exactly is freedom.gov and who is building it?

Freedom.gov is a web portal being developed by the US State Department in coordination with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and Department of Homeland Security. The platform would provide access to online content that governments have blocked or restricted within their countries, such as hate speech, terrorist propaganda, and other censored materials. While officially a State Department initiative, the domain registration and administration involve multiple US government agencies, indicating substantial institutional commitment and resources behind the project.

How would freedom.gov allow people to access blocked content?

The platform would incorporate virtual private network (VPN) functionality directly into the website. Users visiting freedom.gov would be able to connect through the VPN, which would route their traffic through US servers and mask their location as appearing to come from the United States. This technical circumvention would make geographic content restrictions ineffective because websites and governments would see users as accessing from the US rather than their actual location. The key innovation is integrating this functionality directly into the platform so users wouldn't need to download separate VPN software or possess technical knowledge.

Why is Europe concerned about freedom.gov?

European governments enacted content policies including the EU's Digital Services Act and the UK's Online Safety Act through democratic processes to remove hate speech, terrorist propaganda, election disinformation, and child sexual abuse material. Freedom.gov would specifically circumvent these laws that European citizens voted for through their representatives. The concern goes beyond abstract free speech principles to concrete harms. Access to hate speech could fuel violence against minorities, terrorist propaganda could facilitate radicalization, and access to child exploitation material perpetuates documented abuse. European officials worry that freedom.gov shows the US doesn't respect allied democracies' legal frameworks.

What content would freedom.gov make accessible that's currently blocked?

Freedom.gov would provide access to a broad range of content that European governments have restricted, including dehumanizing material targeting immigrants or religious minorities, terrorist recruitment and ideology content, election interference material with false voting information, coordinated disinformation campaigns, and child sexual abuse material. While some of this content might have marginal speech value, the platform's broad approach means it would make accessible materials that cause documented harm. The project doesn't distinguish between valuable suppressed speech and genuinely harmful content.

Is freedom.gov actually going to launch?

As of early 2025, freedom.gov had not yet publicly launched despite initial planning for release at the Munich Security Conference. The delay reflects internal State Department opposition and significant international pushback, particularly from European allies. While multiple US government agencies have invested resources and the domain remains registered and operational, the substantial diplomatic costs and internal bureaucratic friction suggest the platform might launch in limited form or remain in indefinite development. The political feasibility is uncertain even if the technical feasibility is relatively clear.

How does freedom.gov compare to other circumvention tools like Tor or commercial VPNs?

Freedom.gov differs from existing circumvention tools in being directly operated and funded by the US government. Tor and commercial VPN services are private tools that happen to enable access to blocked content as a side effect of providing privacy or security. Freedom.gov is specifically designed and funded by government to circumvent content policies. This creates different legal, diplomatic, and political implications. It also means the infrastructure is directly maintained and operated by government rather than private entities, with attendant security and accountability differences.

Could freedom.gov damage the US-European alliance?

Yes, significantly. European officials have indicated that freedom.gov would substantially damage diplomatic relationships and trust. From Europe's perspective, it represents the US government actively undermining laws that democratic societies enacted. It signals disrespect for European sovereignty and values. The damage could accelerate European digital autonomy efforts, reduce intelligence sharing, and weaken support for NATO and trans-Atlantic cooperation. The project thus carries real diplomatic costs that must be weighed against perceived benefits of advancing digital freedom.

What would happen to people who use freedom.gov in countries with strict content laws?

Users who access freedom.gov might face legal consequences depending on their country's laws. Some countries criminalize circumventing government content policies. Using the platform could theoretically expose users to prosecution. European countries likely wouldn't criminalize access (they have different legal traditions than authoritarian states), but the risk exists in other regions. The platform's security protections help mitigate this, but can't completely eliminate legal risk for users in restrictive jurisdictions.

How does freedom.gov relate to American free speech values?

Freedom.gov represents a particular interpretation of American free speech values that prioritizes maximum access to information and deep skepticism of government restrictions. This reflects the First Amendment tradition where almost all speech is protected except direct incitement to violence. However, it assumes that access to information is always preferable to harm prevention, and that slippery slopes inevitably follow any speech restrictions. This interpretation isn't universal even within American constitutional law, and it differs substantially from how other democracies balance free speech with other rights.

Conclusion: The Future of Digital Rights in a Fragmented Internet

Freedom.gov sits at the center of a fundamental tension that will shape digital policy for decades. It forces a choice between competing visions of what the internet should be and whose values should determine how it works.

The US approach, represented by freedom.gov, prioritizes access and trusts individuals to determine what information matters. This reflects both genuine American values about freedom and the practical interests of American tech companies that benefit from permissive internet environments. It assumes that giving governments power to restrict content inevitably leads to abuse, and that even well-intentioned restrictions create dangerous precedents.

The European approach prioritizes protection from demonstrable harms and trusts democratic processes to determine which harms justify restrictions. This reflects European historical experience with how propaganda precedes violence and how misinformation affects democratic participation. It assumes that some speech causes sufficient harm to justify restriction, and that trust in democratic institutions makes that safe.

Both approaches have legitimate foundations. The US is right to be concerned about government overreach in content moderation. Europe is right to be concerned about harm from unrestricted speech. These aren't obviously compatible positions, and freedom.gov forces a confrontation between them.

What freedom.gov reveals is that the digital world is increasingly fragmented. The unified vision of an open internet connecting everyone is giving way to a reality where different regions will have different rules. The US is committed to maximum access. Europe is committed to regulated content. China and Russia have their own approaches. India, Brazil, and others are developing their own frameworks. Freedom.gov accelerates this fragmentation by making clear that the US is willing to actively undermine other regions' rules.

The practical consequences will likely include more government-built circumvention tools, more digital conflict between nations, more pressure on companies to comply with conflicting regulations, and more rapid digital localization as countries build their own infrastructure independent of US influence. Freedom.gov is a symptom of these larger trends, but it also actively drives them.

For people concerned about genuine digital rights and access to information, freedom.gov presents a dilemma. On one hand, helping people access information their governments block is a valid goal. On the other hand, the platform would also facilitate access to terrorist propaganda and child exploitation material, harms that deserve serious consideration. Neither the US nor European position fully resolves this tension.

The reasonable middle ground would be more sophisticated approaches that distinguish between valuable suppressed speech and genuinely harmful content. But that requires nuance that both the US government's broad access approach and the European government's broad restriction approach lack. Instead, we're getting digitalized ideological conflict where governments assert competing visions without attempting compromise.

Freedom.gov, whether it ultimately launches publicly or remains in indefinite development, has already changed the conversation. It's a statement that the US government views digital freedom as a higher priority than respecting allied democracies' legal choices. That statement, regardless of its implementation, will shape how other countries approach digital governance. They're taking note that the US plays by its own rules, and they're building their own rules accordingly.

The internet we're building is increasingly one where different regions have fundamentally different experiences. Users in the US have maximum access. Users in Europe have curated access. Users in China have heavily restricted access. Users elsewhere fall somewhere on that spectrum. That fragmentation was probably inevitable, but freedom.gov represents the choice to accelerate it rather than resist it.

For anyone involved in technology, policy, diplomacy, or digital rights, understanding freedom.gov matters because it signals the direction those fields are heading. We're not moving toward one global internet with universal rules. We're moving toward multiple internets, each reflecting the values and choices of the countries that shape them. Freedom.gov is one data point in that larger transformation, but it's a significant one.

Key Takeaways

- Freedom.gov is a US State Department platform designed to help people access content their governments have blocked, including hate speech and terrorist propaganda

- The project represents fundamental disagreement between the US (maximum access) and Europe (regulated content) about digital rights and government authority

- European governments enacted content policies like the DSA and Online Safety Act through democratic processes to remove harmful material, which freedom.gov would circumvent

- Technical implementation includes integrated VPN functionality making users appear to access from the US, effectively defeating geographic content restrictions

- Internal State Department opposition and diplomatic pressure from European allies caused delays in the project's public launch

- Freedom.gov could accelerate digital fragmentation where different regions enforce fundamentally different internet rules and content policies

- The project raises unresolved questions about access to harmful content like CSAM and terrorist propaganda justified in the name of digital freedom

Related Articles

- Freedom.gov: Trump's Plan to Help Europeans Bypass Content Bans [2025]

- La Liga VPN Block: What Spain's Court Order Means for Streaming [2025]

- EU Investigation into Shein's Addictive Design & Illegal Products [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: EU Data Privacy Probe Explained [2025]

- Roblox Lawsuit: Child Safety Failures & Legal Impact [2025]

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Teen Instagram Addiction [2025]

![Freedom.gov: US State Department's Controversial Censorship Circumvention Portal [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/freedom-gov-us-state-department-s-controversial-censorship-c/image-1-1771594810290.jpg)