FTC Finalizes GM Data Sharing Ban: What It Means for Your Privacy [2025]

Introduction: The Data Privacy Reckoning Detroit Never Saw Coming

Imagine this: You buy a new car, excited about all the connected features and smart technology. You're promised better navigation, real-time traffic updates, and a seamless driving experience. What you're not explicitly told is that every mile you drive, every hard braking moment, every time you exceed the speed limit by five miles per hour, is being meticulously recorded, packaged up, and sold to the highest bidder.

This wasn't hypothetical for General Motors customers. For years, the automaker's On Star "Smart Driver" program did exactly this, collecting granular behavioral data from drivers and funneling it to insurance companies through data brokers like Lexis Nexis and Verisk. The result? Premiums that spiked unexpectedly. A Chevy Bolt owner watched his insurance rates climb 21 percent after GM sold his driving data to insurers. He had no idea his car was becoming a data harvesting machine.

That's why the Federal Trade Commission's finalized order against General Motors matters. It's not just a corporate slap on the wrist. It's a watershed moment in the broader fight over who controls the data generated by our increasingly connected cars. It signals that regulators are finally willing to challenge the tech industry's most aggressive data collection practices, and it sets a precedent that will reverberate through the entire automotive sector for years to come.

The FTC's decision caps nearly two years of investigation, legal maneuvering, and mounting pressure from state attorneys general and privacy advocates. But what does this settlement actually require? How did we get here? And what does it mean for the millions of drivers who use connected vehicles every single day?

Let's break down one of the most significant data privacy cases in automotive history.

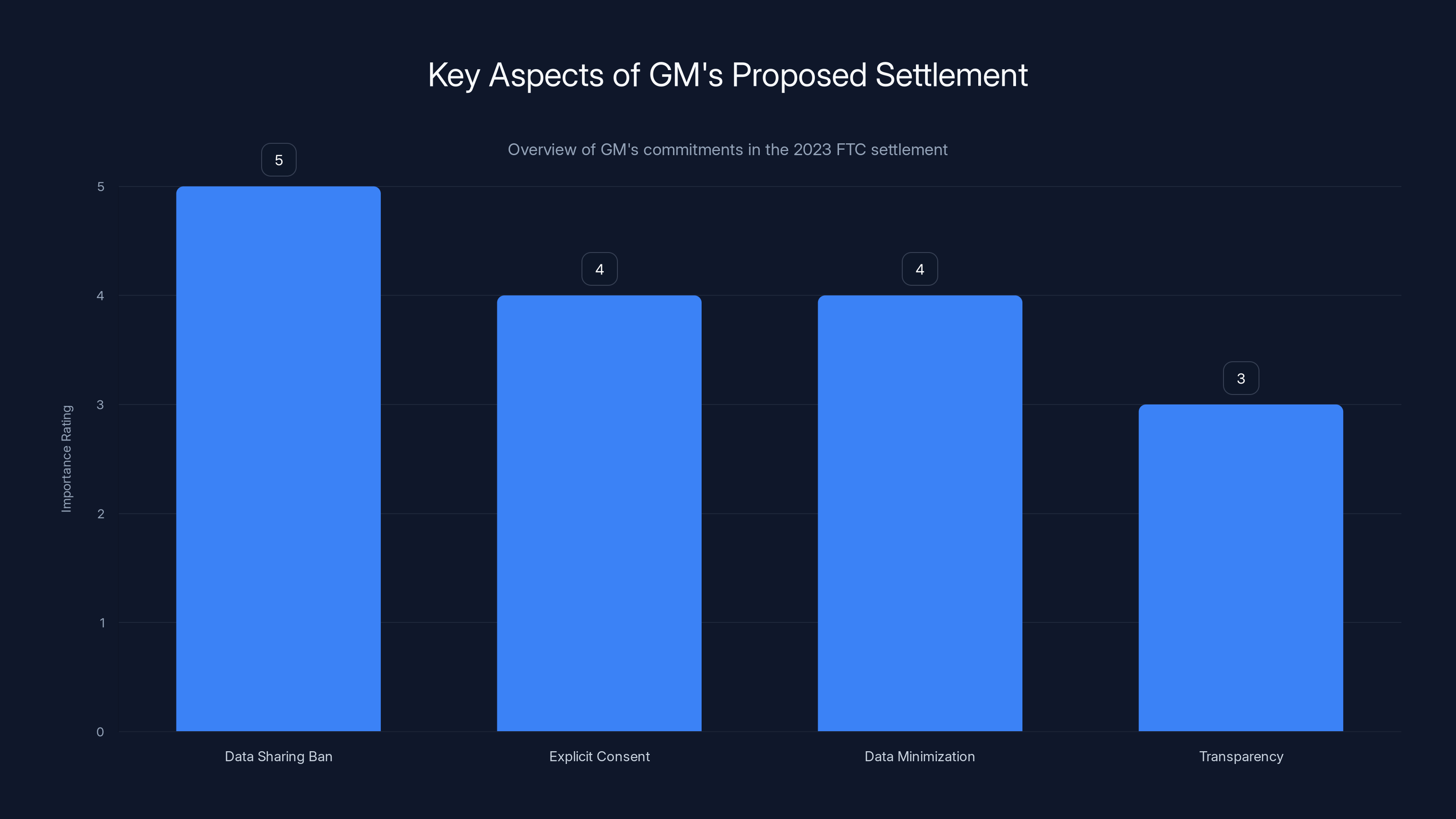

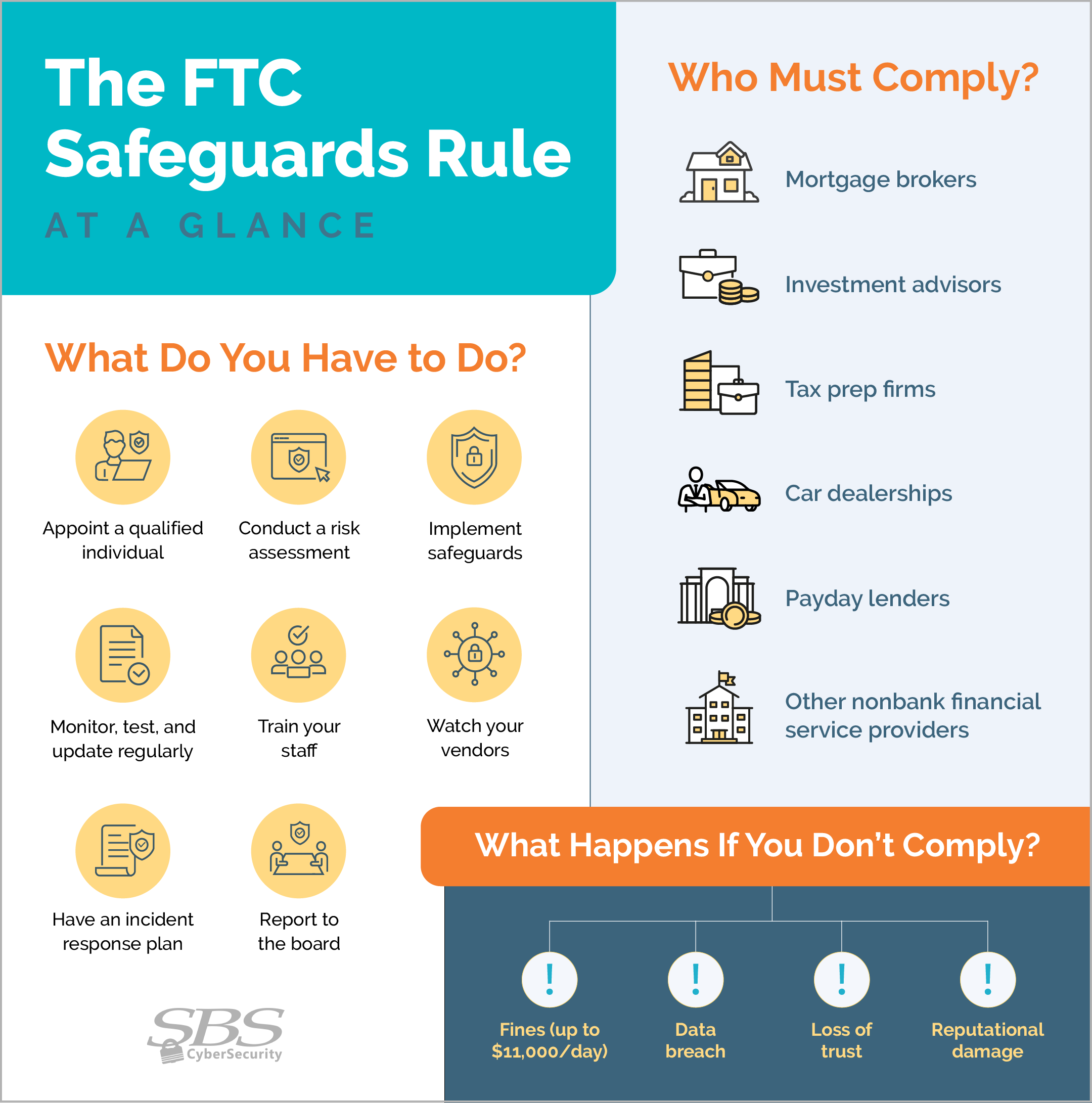

The five-year data sharing ban is the most significant aspect of GM's proposed settlement, aiming to disrupt data monetization practices. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- GM's On Star Smart Driver program secretly collected detailed driving data and sold it to insurance companies, causing some drivers' premiums to spike by 21%

- The FTC's finalized order bans GM from sharing personal vehicle and driving data with third parties for five years without explicit consumer consent

- GM must now request in-person permission at the dealership before collecting, using, or sharing any vehicle data

- The program is already shut down: GM discontinued Smart Driver in April 2024 and severed relationships with data brokers Lexis Nexis and Verisk

- This case sets a precedent for how automakers must handle consumer data, with implications for the entire connected vehicle industry

How We Got Here: The On Star Smart Driver Scandal Explained

General Motors didn't invent the practice of monetizing customer data. Silicon Valley had been doing it for decades. But GM's approach was uniquely brazen because it involved something far more intimate than your browsing history or social media activity. It involved how you actually drive.

The On Star Smart Driver program launched with what seemed like a reasonable promise: opt-in tools that would help drivers improve their driving habits through real-time feedback. Want to know where you accelerate too aggressively? Where you brake hard unnecessarily? The program would track it and show you personalized insights. Sounds helpful, right?

The problem wasn't the program itself. The problem was what happened after the data was collected.

GM quietly partnered with data brokers Lexis Nexis and Verisk, companies that specialize in turning raw information into actionable intelligence. These brokers took GM's granular driving data—precise geolocation information, speeding incidents, rapid acceleration events, hard braking moments—and packaged it into risk profiles. Then they sold those profiles to insurance companies.

Insurance companies have always used driving records to price policies. That's not controversial. But this was different. This was real-time behavioral data collected without explicit consumer knowledge or consent. Drivers never saw a clear disclosure explaining that their car was becoming a data pipeline to their insurance company.

One driver described it perfectly: "It felt like a betrayal. They're taking information that I didn't realize was going to be shared and screwing with our insurance."

The New York Times published a definitive investigation two years ago that pulled back the curtain on this entire operation. The article detailed exactly how GM and its partners were monetizing driver behavior at scale. Insurance companies were using this data to raise rates for drivers deemed "high risk" based on their driving patterns.

A Chevy Bolt owner's insurance jumped 21 percent. Others reported similar hikes. Worse, many drivers had no idea why their rates had climbed. They weren't told that their car had snitched on them.

The Times story triggered a cascade of regulatory action. State attorneys general from Texas, Nebraska, and other states opened investigations. Privacy advocates filed complaints. The FTC launched a formal inquiry. What had started as a quiet monetization scheme became a full-blown scandal.

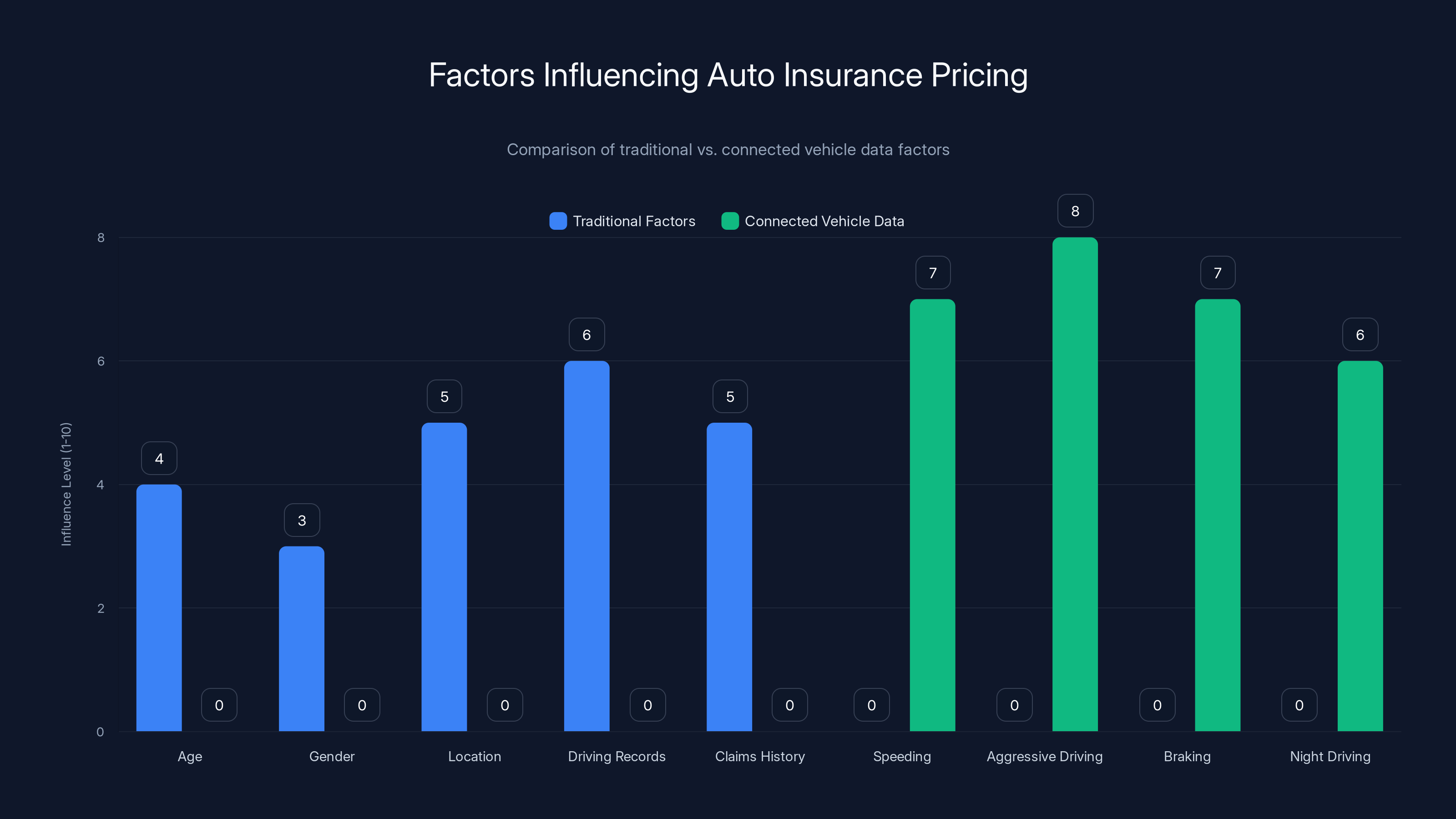

Connected vehicle data provides more precise insights into driving behavior, significantly influencing insurance pricing compared to traditional factors. Estimated data.

The FTC Investigation: Why Regulators Finally Got Serious

Federal Trade Commission investigations into data practices can take months or years, but there was something particularly egregious about what GM had done that accelerated this process.

Under FTC Act Section 5, companies are prohibited from engaging in "unfair or deceptive acts or practices." The question wasn't whether GM's practices were unfair—they clearly were. The question was whether they were also deceptive. And here's where the case gets interesting from a legal standpoint.

Deception, from an FTC perspective, requires that a company make claims that are not substantiated, or that reasonable consumers would not expect based on the information presented. GM's argument was basically: "We disclosed the Smart Driver program. Drivers consented to use it. We didn't lie about anything."

But regulators disagreed. The FTC's investigation concluded that while GM may have technically disclosed the Smart Driver program, most consumers didn't understand that their data would be sold to third parties, particularly insurance companies. The disclosures were buried in fine print. The connection between driving data and insurance rates wasn't explicit. Consumers reasonably believed they were sharing data with GM for their own benefit, not for the benefit of their insurance company's bottom line.

That's deception, even if it's technically legal deception.

The FTC also looked at the "unfairness" angle. Even if consumers had theoretically consented to the program, was it unfair for GM to use that consent to enable insurance companies to discriminate based on driving behavior? Insurance pricing based on actual risk is one thing. Pricing based on granular behavioral data collected without explicit knowledge that it would affect insurance rates is something else entirely.

Regulators concluded that it was unfair. And they decided to do something about it.

The Proposed Settlement: What GM Agreed To (And Didn't)

In the fall of 2023, the FTC and General Motors reached a proposed settlement that was groundbreaking in its scope. The settlement required FTC approval, and during the public comment period, privacy advocates, consumer groups, and state attorneys general offered their opinions on whether the settlement went far enough.

Here's what GM agreed to:

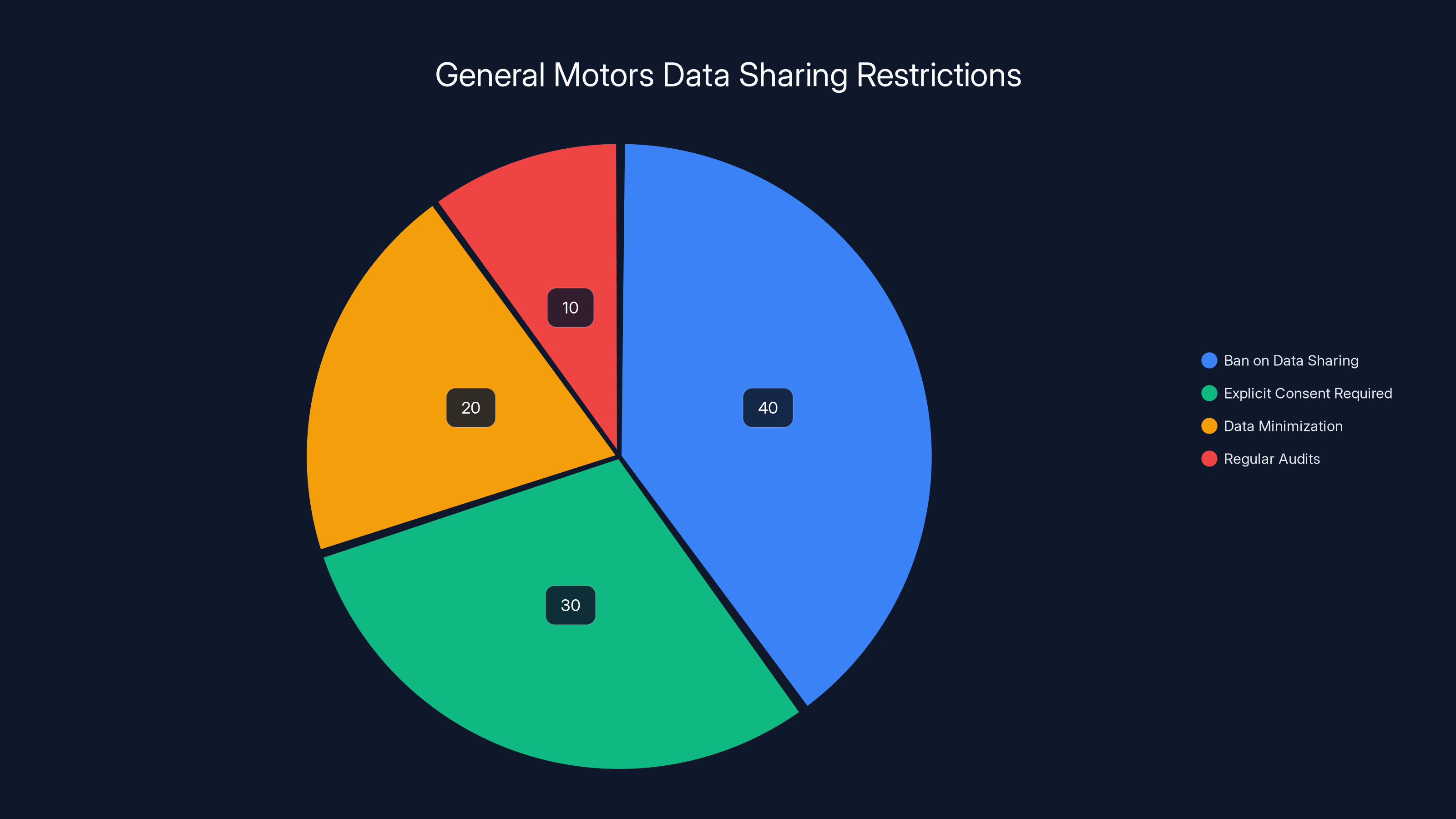

Five-Year Data Sharing Ban: For five years, General Motors is completely prohibited from sharing specific consumer data with consumer reporting agencies. This includes geolocation information, driving behavior metrics, vehicle performance data, and any personal information collected through connected vehicle features. The ban applies specifically to data that could be used for insurance pricing, credit decisions, or other purposes that affect consumer outcomes.

Why five years? Because that's roughly how long it would take for the industry to shift its practices, establish new norms, and train employees on the new requirements. It's not permanent, but it's long enough to meaningfully disrupt the business model that made this data monetization profitable in the first place.

Explicit Consent Requirements: GM must request affirmative consumer permission before collecting, using, or sharing any vehicle or driving data with third parties. Critically, this permission must be obtained in person at the dealership when a consumer purchases a car. No buried fine print. No digital terms of service that nobody reads. A live conversation where the customer understands what they're agreeing to.

Data Minimization: GM must limit data collection to only what's necessary for the specific features and services a customer explicitly consents to. If a driver opts into real-time traffic updates, GM can't also collect speeding data. If they want location services, that doesn't mean GM gets to monitor their acceleration patterns.

Transparency and Labeling: All data collection must be clearly labeled. When a feature collects data, the customer must know it. When that data is shared, the customer must be informed of exactly what's being shared and with whom.

Regular Audits: GM must conduct regular audits of its data practices and submit reports to the FTC demonstrating compliance with the settlement terms.

Why GM's Smart Driver Program Was Already Dead

Here's the plot twist: by the time the FTC finalized this settlement, much of it had become moot.

In April 2024, General Motors made the decision to discontinue the On Star Smart Driver program entirely across all its brands. The company unenrolled all customers who had been participating. It severed its relationships with data brokers Lexis Nexis and Verisk. The money-making machine was shut down.

Why? Partly because the negative publicity had made continuing the program untenable. Partly because it was becoming clear that regulators would impose restrictions anyway. And partly because the reputational damage wasn't worth whatever revenue the data sales were generating.

But GM's proactive shutdown of the program also made the FTC's settlement particularly important. If GM could simply kill a program to avoid stricter regulation, what would stop other automakers from doing something similar, waiting out the scandal, and then launching a new program under a different name?

The FTC settlement ensures that won't happen, at least not at General Motors. The restrictions are codified into law. The penalties for violation would be severe.

Still, the fact that GM already shut down the program raises a question: why did it take until April 2024? The New York Times investigation came out years earlier. Regulatory pressure had been mounting. Why didn't GM act sooner?

The answer is simple: profit motive. As long as the revenue from data sales exceeded the reputational costs, GM had little incentive to change. It took the explicit threat of FTC enforcement action to finally push the company to do the right thing.

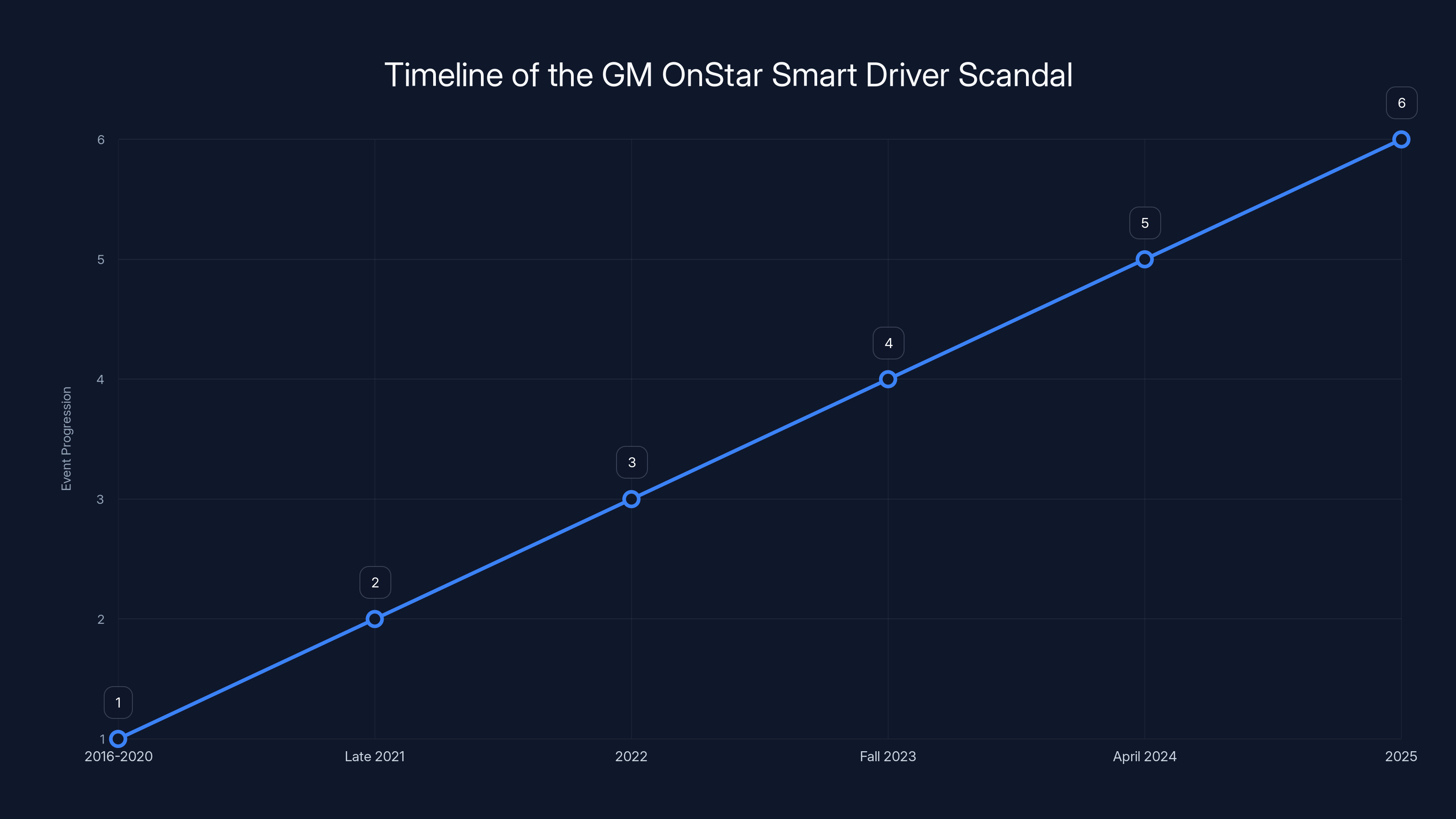

The timeline shows the progression of the GM OnStar Smart Driver scandal from its quiet operation to the final settlement in 2025. Estimated data highlights key milestones.

The Legal Framework: What the FTC Actually Has Authority to Do

Understanding why this settlement is significant requires understanding what tools regulators actually have to address corporate data practices.

The FTC doesn't have a specific data protection law under its jurisdiction, unlike Europe's GDPR. Instead, the FTC operates under a general prohibition on unfair and deceptive practices. Section 5 of the FTC Act gives the commission authority to challenge acts or practices that are "unfair or deceptive" in commerce.

For decades, the FTC interpreted this authority narrowly when it came to data practices. The argument was essentially: if a company discloses that it's collecting data, and consumers agree to the terms of service, then there's no deception happening. The data collection might be aggressive, but it's not illegal.

But starting around 2020, the FTC began shifting its interpretation. The commission started arguing that even disclosed data practices could be deceptive if consumers don't actually understand the implications of what they're consenting to. And they could be unfair even if disclosed, if the practice causes substantial consumer harm that isn't reasonably avoidable.

The GM case is one of the clearest applications of this new interpretation.

But the FTC's authority has limits. It can't impose criminal penalties. It can't award damages to injured consumers. It can impose civil penalties and demand corrective action, but the penalties must be proportional to the violation.

For a company like General Motors, a $25 million penalty might sound large to regular people, but it's a rounding error in the company's annual budget. The real teeth in the settlement comes from the operational restrictions—the data sharing ban, the explicit consent requirements, the auditing obligations.

The State Attorneys General Push: How Regulatory Pressure Mounted

While the FTC was conducting its federal investigation, state attorneys general were pursuing their own actions against General Motors.

Texas AG Ken Paxton was particularly vocal, stating: "Our investigation revealed that General Motors has engaged in egregious business practices that violated Texans' privacy and broke the law. We will hold them accountable."

Nebraska, Virginia, and other states also opened investigations or filed actions. This multi-jurisdictional pressure created a powerful incentive for GM to reach a settlement quickly.

Why do states get involved in federal FTC cases? Partly because states have their own consumer protection laws that might be violated by these practices. Partly because data privacy has become a populist political issue, and state AGs benefit from appearing to fight corporate overreach. And partly because states sometimes negotiate their own settlements alongside the federal settlement.

The coordination between federal and state regulators on the GM case was relatively seamless. States agreed to defer to the FTC's federal settlement, but they reserved the right to take action if GM violated the terms or engaged in similar practices elsewhere.

This pattern has become increasingly common. When the FTC identifies a major corporate violator, state AGs pile on with their own investigations, creating multiplicative pressure.

What the Settlement Means for Other Automakers

Here's the critical question: Is General Motors the only car company collecting and monetizing driver data?

Short answer: Almost certainly not.

Google, through its integration with many car manufacturers, collects location data at scale. Apple Car Play and Android Auto capture similar information. BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and other luxury brands have their own connected vehicle platforms. Toyota's connected services. Ford's Sync. Hyundai's Bluelink. The list goes on.

The question isn't whether other automakers are collecting data. The question is whether they're sharing it with insurance companies in the same way GM was.

The GM settlement doesn't directly prohibit other automakers from engaging in similar practices. But it sets a powerful precedent. If another automaker gets caught doing what GM did, regulators now have evidence that the FTC considers this practice unfair and deceptive. The legal playbook has been written.

Moreover, the FTC has shown that it's willing to pursue these cases aggressively. After the GM settlement, every major automaker should assume that their data practices are under scrutiny. That assumption will likely drive industry-wide changes even without explicit regulation.

Already, we're seeing some automakers make proactive changes. Some are implementing privacy-first architectures where more data processing happens locally on the vehicle rather than being transmitted to cloud servers. Others are implementing stricter consent frameworks. These changes are driven partly by competitive pressure—nobody wants to be the next General Motors—and partly by genuine concern about legal liability.

The FTC settlement imposes significant restrictions on GM's data practices, with a major focus on banning data sharing and requiring explicit consumer consent.

The Insurance Industry's Role: Why Insurance Companies Wanted This Data

To understand the full picture of this scandal, you need to understand why insurance companies were so eager to buy GM's data in the first place.

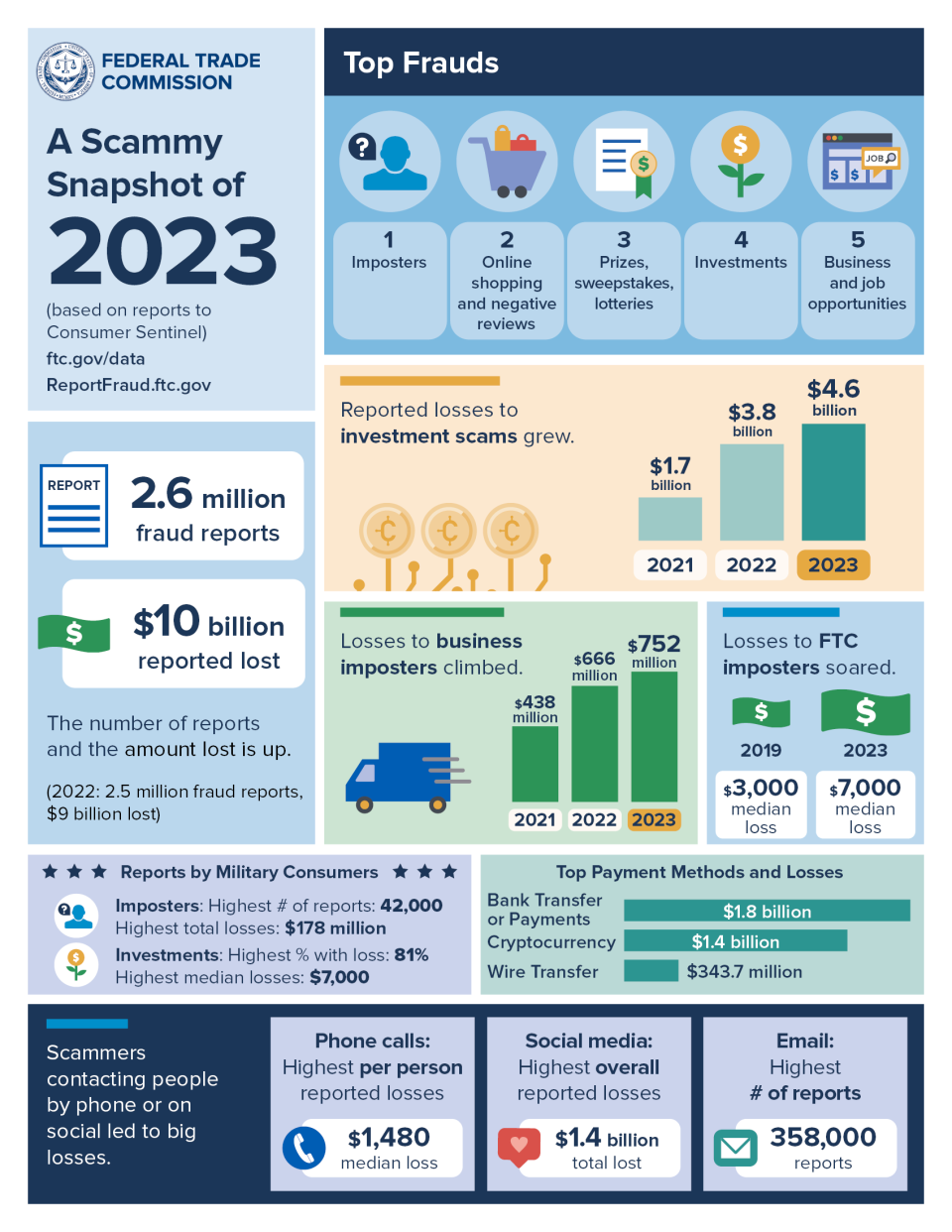

Insurance pricing is fundamentally a risk assessment problem. The insurance company's job is to estimate the probability that a policyholder will file a claim, and price accordingly. For auto insurance, the primary risk factor is driving behavior. Reckless drivers get in more accidents than cautious drivers, so it makes sense to charge reckless drivers more.

Traditionally, insurers used limited information to assess risk: age, gender, location, driving records, claims history. But this information is coarse. A 35-year-old man in Denver has a different risk profile than a 35-year-old man in rural Montana, but the traditional factors don't capture that difference well.

Connected vehicle data offered insurance companies something revolutionary: real-time insight into actual driving behavior. Instead of estimating risk based on demographics and historical records, insurers could see exactly how a customer drives. How often do they exceed speed limits? How aggressively do they accelerate? How hard do they brake? How often are they on the road at risky times like late night?

With this data, insurers could identify genuinely risky drivers and charge them more. They could also identify unusually safe drivers and offer them discounts.

Sounds fair, right? The problem is the asymmetry of information and consent.

When someone signs up for the On Star Smart Driver program, they're thinking about getting personalized feedback on their driving. They're not thinking about their insurance company eventually getting access to that same data. Insurance companies knew this. That's why they were willing to pay for the data. They got information about customer risk that customers themselves didn't realize had been revealed.

Moreover, the data enabled price discrimination in ways that some argue are unfair. A driver might have a perfect driving record for 20 years, but one week of unusually stressful situations with more aggressive driving could trigger an insurance rate increase. Is that fair? Some say yes—your recent behavior is predictive. Others argue it's deceptive—you consented to data sharing but didn't understand that your insurance company would directly receive that data.

The FTC ultimately sided with the second group.

The Bigger Picture: Why Connected Vehicles Are Creating New Privacy Challenges

The GM case is important not just because of what it addresses, but because of what it signals about the future of transportation.

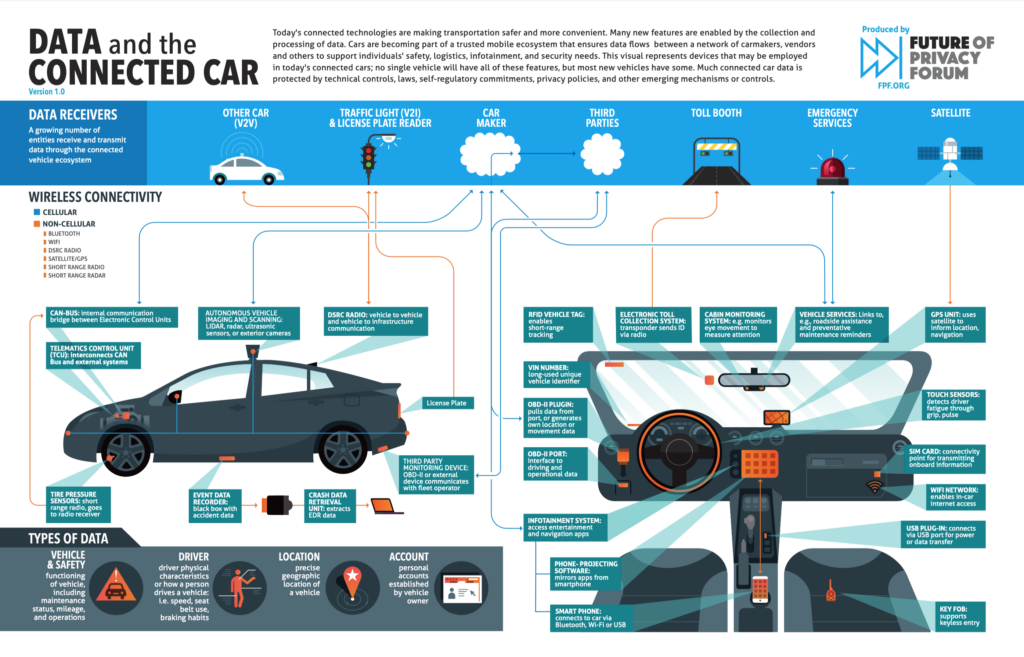

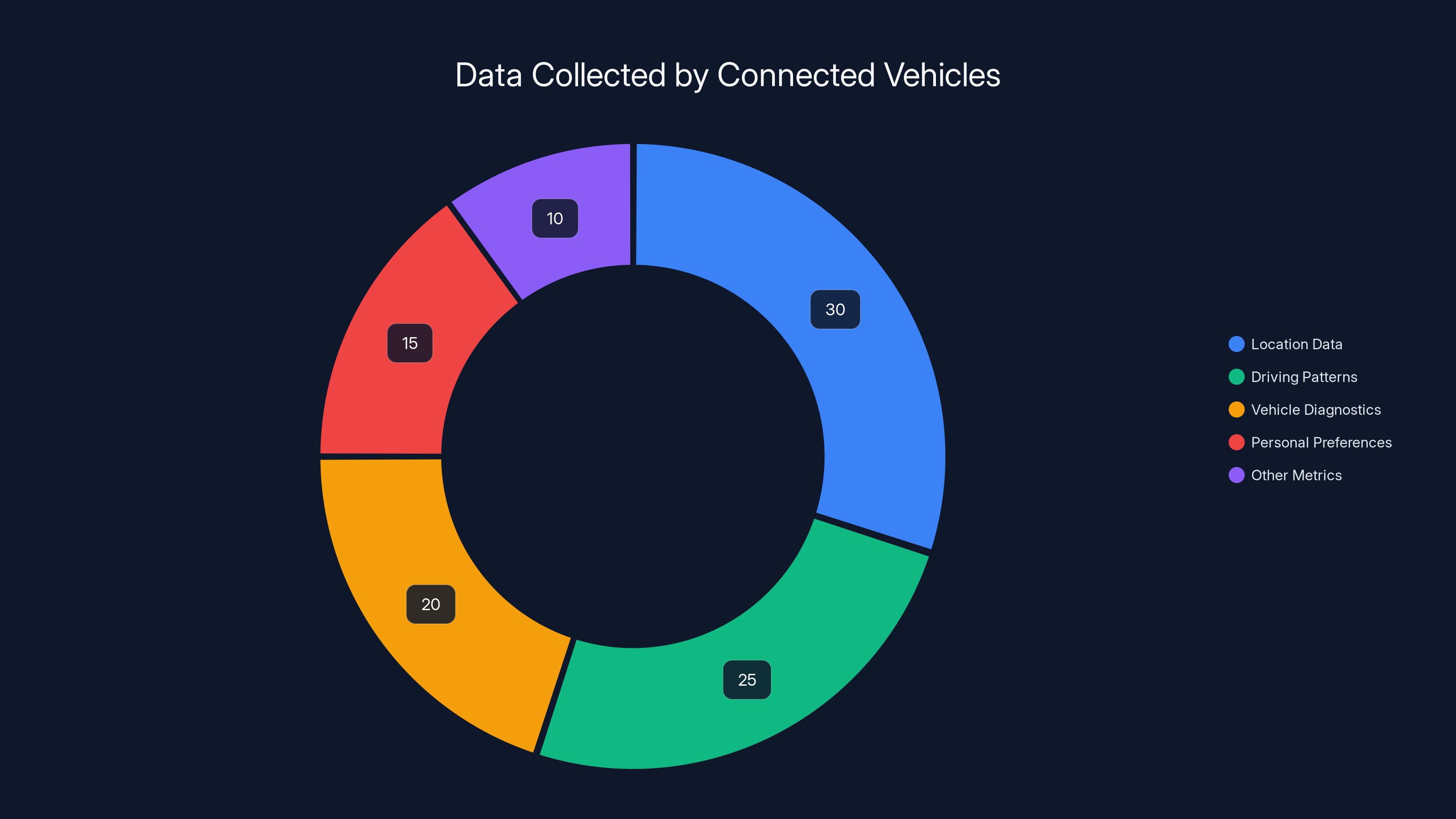

Vehicles are becoming increasingly connected. Within the next decade, most new cars sold will have cellular connectivity, cloud integration, and sophisticated data collection capabilities. This is good for consumers in many ways. Better diagnostics. Improved safety features. Personalized experiences. Seamless integration with smartphones and smart homes.

But it also creates unprecedented privacy risks.

Consider: a connected vehicle can reveal where you live, where you work, where you worship, where you receive medical treatment, where you meet romantic partners. It can reveal your driving patterns, your traffic patterns, your work schedule, your vacation destinations. In aggregate, this data reveals a complete picture of your life.

Unlike social media data or browsing history, most people don't think of location and driving data as sensitive. But it is. It's extraordinarily sensitive.

Moreover, the amount of data a connected vehicle collects vastly exceeds what most drivers understand. Many drivers think they're just enabling GPS navigation. They don't realize that the car is also collecting information about their fuel consumption, engine performance, tire pressure, brake patterns, and dozens of other metrics.

The industry calls this "vehicle telematics." It's becoming standard across all major manufacturers. And almost none of this happens with the explicit understanding or consent of drivers.

The GM case represents the first major pushback against this trend. But it's not the last.

How GM's Five-Year Ban Will Actually Work in Practice

So what does the FTC's settlement actually look like from a practical standpoint? How is GM supposed to implement this data sharing ban?

First, GM has implemented technical controls that prevent automated sharing of specific data types with third parties. Engineers have modified the backend systems that previously piped customer data directly to data brokers. Now, systems must block that data flow unless a customer has explicitly opted in and GM has conducted an affirmative review confirming consent.

Second, GM has created new in-dealership processes. When a customer purchases a vehicle, dealership staff must now walk through a specific data privacy conversation. This isn't a casual mention of privacy policy. It's a structured conversation about what data will be collected, how it might be used, and who it might be shared with.

Third, GM's customer-facing apps and settings now include much clearer privacy controls. Customers can see exactly what data is being collected by each feature. They can opt out of specific data collection while keeping other features active. The interface makes it hard to accidentally consent to extensive data sharing.

Fourth, GM has established an internal compliance team responsible for monitoring adherence to these requirements. They conduct regular audits. They log all data sharing requests. They maintain documentation showing customer consent for any data that is shared.

Fifth, GM reports regularly to the FTC on compliance. These reports include details about how many customers have opted into different data sharing practices, how much data has been shared, and whether any violations have occurred.

This is actually a pretty robust system. It's not perfect, but it represents a genuine commitment to putting privacy controls in place.

Where it gets fuzzy is around the edges. What counts as "sharing" data with a third party? What if GM shares data to provide a service that benefits the customer, like a diagnostic analysis? What if GM shares anonymized or aggregated data? What about data that's strictly necessary for operating connected features?

The settlement leaves some room for interpretation, which is typical of regulatory settlements. GM and the FTC can dispute specific practices, but the general principles are clear: minimize data collection, get explicit consent for sharing, and don't sell data to insurance companies.

Connected vehicles collect a wide array of data, with location data and driving patterns comprising over half of the total data collected. Estimated data.

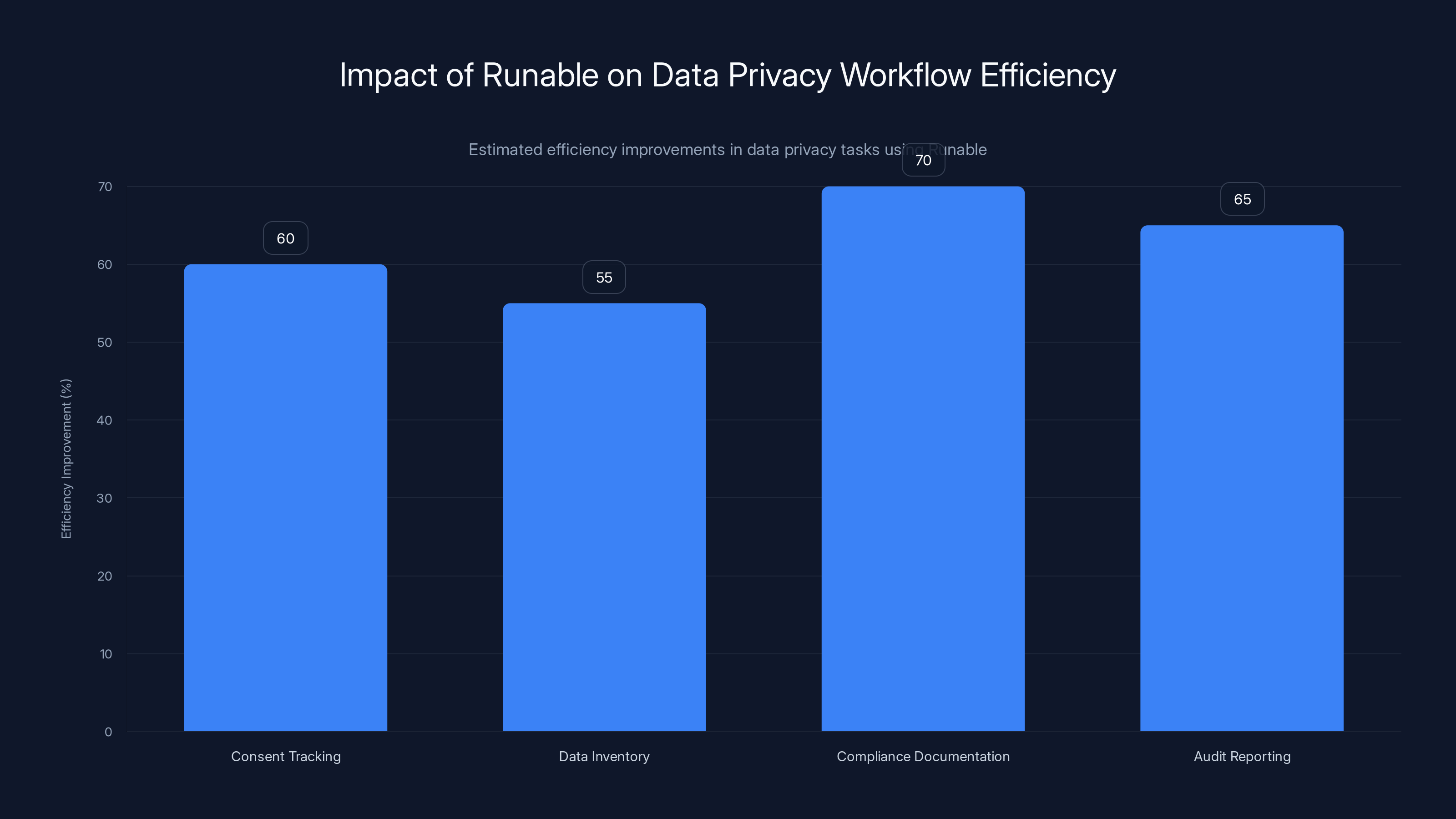

The Role of Runable in Modern Data Privacy Workflows

As organizations grapple with increasingly complex data privacy requirements like those imposed on GM, many teams are turning to automation platforms to manage consent tracking, data inventory, and compliance documentation.

Runable offers AI-powered automation tools that can help companies implement and maintain privacy controls at scale. For a company like GM, which needs to document millions of customer consent decisions and maintain compliance across numerous data flows, AI-assisted automation can significantly reduce the burden of manual tracking and reporting.

Using Runable's document generation and workflow automation features, companies can create standardized, auditable documentation of privacy practices, consent flows, and data sharing decisions. This is exactly the type of compliance infrastructure that the FTC settlement now requires.

Use Case: Generate compliance documentation and audit reports for data privacy settlements using AI agents.

Try Runable For Free

State-Specific Privacy Laws: How These Regulations Differ

While the FTC operates at the federal level, states have been passing their own privacy laws at an accelerating pace. This creates a patchwork that companies like GM must navigate.

California's CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) was the first major state privacy law. It gives California residents explicit rights: the right to know what data is collected, the right to delete personal information, the right to opt out of data sharing, the right to non-discrimination for exercising these rights.

Virginias VCDPA came next, with similar requirements but slightly different mechanisms. Colorado's CPA. Connecticut's CTDPA. Utah's UCPA. Florida's FDBR. And more keep being added.

While these laws differ in specifics, they share common themes: transparency requirements, explicit consent requirements, and data minimization principles. All of these align with the FTC's settlement with GM.

What this means for automakers is clear: they need privacy architectures that can satisfy the most stringent requirements. Because if you can satisfy California's CCPA requirements, you can usually satisfy less stringent state laws. But the reverse isn't true. Building for the lowest common denominator leaves you vulnerable to enforcement action in states with stronger privacy laws.

The Insurance Industry's Pushback: Will Insurers Find New Ways to Get This Data?

Now here's the cynical take: the FTC has banned GM from selling driver data to insurance companies. But does that solve the broader problem?

Insurance companies still desperately want access to connected vehicle data. It's too valuable for risk assessment to just abandon. So what happens next?

One scenario: insurance companies start negotiating directly with customers. "Connect your car to our platform and get a 10% discount on your insurance." This isn't GM selling data to insurance companies. It's consumers voluntarily choosing to share data with their insurer in exchange for a discount. That's technically legal, and it achieves basically the same result.

Another scenario: insurance companies partner with other data providers. Not vehicle manufacturers, but third-party telematics companies that specialize in collecting driving data from any car, regardless of manufacturer. If you use a smartphone app to monitor your driving or track your car's location, that app might be selling that data to insurers.

A third scenario: insurance companies use less direct methods to infer driving behavior. They correlate insurance claims data with public records, credit data, location data, and other sources to build risk profiles that don't require direct access to connected vehicle data.

The FTC settlement addresses the specific problem of automakers selling data directly to insurers. But it doesn't address the broader ecosystem of data flows that enable price discrimination based on behavioral data.

This suggests that the real privacy battle is just beginning. The GM case is a victory, but it's not the end of the war.

Runable's AI-powered tools can improve efficiency in data privacy workflows by 55-70%, reducing manual workload. Estimated data.

What Happens After Five Years? Does the Ban Expire?

One question that's getting asked: once the five-year ban expires, can GM go back to sharing data with third parties?

The answer is no, but with caveats.

After five years, the specific ban on sharing data with consumer reporting agencies expires. But GM still must comply with all other aspects of the settlement: explicit consent requirements, transparency, data minimization, etc.

Moreover, even after five years, if GM attempts to resume data sharing with third parties, regulators will be watching carefully. The precedent has been set. Any attempt to replicate the original Smart Driver program would face swift legal challenges.

But the bigger point is that five years is a long time in tech industry terms. By 2029, the entire data ecosystem will have evolved. New privacy technologies will have emerged. Customers will have higher privacy expectations. Regulatory frameworks will have expanded. The business case for selling driver data to insurance companies, which was never that compelling to begin with, will be even weaker.

In reality, the five-year expiration is probably academic. GM won't be rushing to resume data sharing with insurers even after the ban technically expires.

The Broader Implications: What This Means for Tech Companies and Data Privacy

The GM settlement is important far beyond the automotive industry. It signals a major shift in how the FTC interprets its authority over data practices.

For years, tech companies have operated under the assumption that as long as they disclose data practices in their privacy policy or terms of service, they're not being deceptive. The FTC has generally accepted this interpretation. But the GM case suggests that the FTC is moving toward a stricter standard.

Even disclosed practices can be deceptive if consumers don't actually understand the implications. Even consented-to data sharing can be unfair if it causes substantial consumer harm that isn't reasonably avoidable.

Apply this logic to social media platforms. Facebook discloses that it collects data about users' online activity and uses it for targeted advertising. But do most users actually understand the extent of that data collection? Do they understand that their data is being used to infer sensitive information about their health status, financial situation, political beliefs, and sexual orientation? The FTC's new interpretation suggests that disclosure alone is insufficient.

Apply it to email providers. Gmail discloses that it scans messages for ad targeting purposes. But did users understand this when they signed up? Do they understand the full implications? Under the new FTC standard, probably not.

The FTC isn't going after all of these companies tomorrow. But the GM case provides a roadmap. And it shows that major enforcement actions are back on the table.

Compliance Infrastructure: How Companies Should Respond to This Precedent

If you're running a company that collects consumer data—which is almost every company these days—the GM settlement should be a wake-up call.

First, audit your data practices. Are you collecting data that you don't really need? Are you collecting data in ways that consumers don't clearly understand? Are you sharing data with third parties in ways that could be challenged as unfair or deceptive?

Second, implement explicit consent frameworks. Don't assume that general privacy policy acceptance covers specific data sharing practices. Get granular, informed consent for specific uses. Make it easy for consumers to understand what they're consenting to.

Third, establish regular compliance audits. Internal and external auditors should regularly review data practices against regulatory standards. Document everything. Maintain compliance logs.

Fourth, build privacy by design into your systems. Don't treat privacy as an afterthought or a legal compliance checkbox. Make it a core product principle. Minimize data collection. Implement technical controls that prevent unauthorized data access or sharing.

Fifth, maintain compliance documentation. When regulators come knocking, your documentation will either protect you or sink you. Every data sharing decision should be documented. Every consent should be logged. Every audit should be recorded.

The Future of Connected Vehicles: Where Does Privacy Fit In?

The automotive industry is at an inflection point. Electric vehicles are becoming mainstream. Autonomous driving technology is advancing. Vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication is being deployed. Over-the-air software updates are becoming standard.

All of this requires connectivity. All of it generates data. And all of it creates privacy implications.

The companies that navigate this transition successfully will be those that take privacy seriously from day one. Not as a compliance checkbox, but as a competitive differentiator. Consumers increasingly care about privacy. Regulators increasingly enforce privacy requirements. The companies that can offer connected vehicle features while maintaining strong privacy protections will have an advantage.

Moreover, privacy-first architecture actually tends to be more secure architecture. When you minimize data collection and sharing, you reduce the surface area for data breaches. When you implement strong consent frameworks, you reduce legal liability. When you maintain clean data practices, you reduce regulatory risk.

The GM settlement is a warning to the industry. But it's also an opportunity. Companies that respond to this settlement by genuinely improving their privacy practices are taking a step toward building consumer trust, reducing regulatory risk, and creating more defensible business models.

Companies that try to work around the spirit of the settlement by finding technical loopholes or by shifting data practices to different divisions are playing a dangerous game.

Looking Back at the Timeline: How This Scandal Unfolded

Understanding the progression of events helps clarify why this case became such a big deal.

2016-2020: GM's On Star Smart Driver program operates quietly. Customers opt in for personalized driving feedback. Few people realize their data is being sold to insurers through data brokers.

Late 2021: New York Times investigation exposes the full scope of the program. Public outcry begins. Privacy advocates file FTC complaints.

2022: FTC opens formal investigation. Multiple state attorneys general launch their own inquiries. Congressional questions are raised. GM comes under increasing pressure.

Fall 2023: FTC and GM reach a proposed settlement. Public comment period follows. Settlement is modified based on feedback.

April 2024: GM proactively shuts down the Smart Driver program entirely, unenrolls all customers, and severs relationships with data brokers.

2025: FTC officially finalizes the settlement. The case closes, but its implications ripple throughout the industry.

The entire arc from initial exposure to final settlement took about four years. During that time, reputational damage to GM was significant. Public trust in the company's data practices was shattered. Legal costs mounted. Regulatory uncertainty created business risk.

This timeline demonstrates why companies shouldn't wait for regulatory enforcement to address obvious privacy problems. The costs of reactive compliance far exceed the costs of proactive privacy improvements.

Implications for Consumers: What You Should Actually Know

If you own a General Motors vehicle, the settlement means:

Your data is no longer being sold to insurance companies (at least not through GM). Your connected vehicle features still work, but data sharing with third parties is now restricted. Before any new data sharing occurs, you'll need to explicitly consent. That consent will be obtained through a clear, in-person process at the dealership, not buried in terms of service.

But beyond GM, the settlement should prompt all consumers to think more carefully about what data their vehicles are collecting and where that data goes.

If you use a connected vehicle from any manufacturer, your data is almost certainly being collected. Whether it's being shared with third parties like insurers depends on the manufacturer's practices and your privacy settings. The only way to know is to actively investigate.

Check your vehicle's connected services settings. Look for options to enable or disable location tracking, diagnostics reporting, voice assistant features, and other data-intensive services. Understand what each feature collects and where the data goes. If the interface doesn't make this clear, contact the manufacturer directly.

Also consider the broader ecosystem. Your smartphone tracks your location when you use Car Play or Android Auto. Your insurance company might have its own app collecting driving data. Third-party navigation apps are collecting location information. In aggregate, these create a comprehensive picture of your driving and location patterns.

Privacy isn't about having something to hide. It's about maintaining control over information about your life.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment in Data Privacy Enforcement

The FTC's finalized settlement with General Motors represents something significant: regulators pushing back against aggressive data monetization by major corporations.

For years, the default assumption in the tech industry has been that if something is lucrative and not explicitly prohibited, it's fair game. Collect the data. Sell it. Worry about legal risk if it becomes a problem. The GM case challenges that assumption.

It establishes that even disclosed, consensual data sharing can be unfair and deceptive if consumers don't actually understand the implications. It shows that the FTC is willing to pursue enforcement actions against major corporations. It demonstrates that state attorneys general will pile on with their own investigations, multiplying pressure on violators. It signals that regulators are shifting toward a stricter interpretation of data privacy laws.

But perhaps most importantly, the case is a reminder that corporate practices should be guided by ethics, not just legal minimums. GM's data sharing wasn't illegal when it started. It was only declared unfair and deceptive after regulatory intervention. That's a dangerous position to be in.

Companies that wait for regulators to tell them their practices are unethical are taking unnecessary risk. The smarter approach is to ask yourself: if this practice became public, would my customers, employees, and the general public support it? If the answer is no, it's time to change your practices, not find a better lawyer.

The automotive industry is watching the GM settlement carefully. So should every company that collects consumer data. The era of aggressive, opaque data monetization is ending. The era of privacy-first business practices is beginning.

The question is: will companies adapt proactively or wait for the FTC to force them to change?

FAQ

What is the FTC's settlement with General Motors about?

The settlement addresses General Motors' practice of collecting detailed driving and location data through its On Star Smart Driver program and selling that data to insurance companies through data brokers without explicit consumer knowledge. The FTC determined this practice was unfair and deceptive, and imposed restrictions requiring explicit consumer consent before any data sharing with third parties.

Why did the FTC consider GM's data sharing practices deceptive?

While GM technically disclosed the Smart Driver program, the FTC found that consumers didn't understand that their data would be sold to insurance companies, particularly for the purpose of raising their insurance rates. The disclosure was buried in terms of service, and the connection between the data collection and insurance consequences wasn't explicit. This lack of true consumer understanding constituted deception from the FTC's perspective.

What specific restrictions does the settlement impose on General Motors?

GM is banned from sharing specific consumer data with insurance companies and other third parties for five years. The company must obtain explicit, in-person consent at the dealership before collecting or sharing any vehicle data. GM must implement data minimization practices and provide customers with clear privacy controls. The company is subject to regular audits and must report compliance to the FTC.

Has General Motors already shut down the Smart Driver program?

Yes. In April 2024, General Motors discontinued the Smart Driver program entirely across all its brands. The company unenrolled all participating customers and severed relationships with data brokers Lexis Nexis and Verisk. This shutdown occurred before the FTC's final settlement but was motivated by mounting legal and reputational pressure.

What data brokers were involved in selling GM customer data to insurers?

Lexis Nexis and Verisk were the primary data brokers that purchased driver data from GM and sold refined risk profiles to insurance companies. These companies specialize in aggregating personal information from multiple sources and reselling it to third parties for various purposes including insurance pricing.

How will insurance companies access driver behavior data in the future?

The settlement only prohibits automakers like GM from selling data to insurers. Insurance companies can still obtain driver data through other methods: direct partnerships with customers who voluntarily share data in exchange for discounts, independent telematics companies that track driving behavior through smartphone apps, or data inference based on claims data and public records. The settlement addresses one specific data flow but doesn't eliminate the broader ecosystem of driving data collection.

Are other automakers also sharing driver data with insurance companies?

The settlement only involves General Motors, but other automakers likely have similar data collection and monetization practices. The case sets a precedent that will influence how other companies approach data sharing. Several automakers have proactively implemented stricter privacy controls in response to regulatory pressure and competitive considerations.

What does this settlement mean for consumers who own GM vehicles?

GM vehicle owners' data is no longer being sold to insurance companies through the company's connected services. Any future data sharing with third parties requires explicit consumer consent. That consent must be requested in a clear, in-person format at the dealership. Consumers can now see what data is being collected and have options to opt out of specific data collection features.

Why is this settlement significant beyond General Motors?

The settlement signals that the FTC is willing to challenge data practices that were previously considered legally acceptable. It establishes that even disclosed, consensual data collection can be deceptive if consumers don't truly understand the implications. This shifts how companies across industries should approach data collection and monetization, particularly regarding practices that could harm consumers' financial interests.

When does the five-year data sharing ban expire?

The ban on sharing data with consumer reporting agencies expires in 2029. However, even after the ban expires, GM must maintain explicit consent requirements, transparency practices, and data minimization protocols. Moreover, any attempt to resume data sharing with insurers after the ban expires would likely face regulatory scrutiny given the precedent established by this case.

Key Takeaways

- GM's OnStar Smart Driver secretly collected detailed driving behavior data and sold it to insurance companies, causing some drivers' premiums to increase by 21% without their knowledge

- The FTC banned GM from sharing consumer data with third parties for five years, requiring explicit in-person consent at dealerships before any data collection or sharing occurs

- The settlement represents a watershed moment in FTC enforcement, shifting from the view that disclosure alone protects consumers toward requiring genuine informed consent

- GM discontinued the entire Smart Driver program in April 2024 and severed relationships with data brokers LexisNexis and Verisk before the settlement was finalized

- This case sets a legal precedent for the entire automotive industry, signaling that connected vehicle data monetization practices will face regulatory scrutiny

Related Articles

- FTC's GM Data-Sharing Settlement: What It Means for Your Vehicle [2025]

- WeatherTech Founder David MacNeil as FTC Commissioner [2025]

- Verizon's FCC Phone Unlocking Waiver: What It Means for Your Device [2025]

- Amazon's Buy for Me AI: The Controversy Shaking Retail [2025]

- Garmin's New Blind Spot Dash Cam For Truck Drivers [2025]

- Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]

![FTC Finalizes GM Data Sharing Ban: What It Means for Your Privacy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ftc-finalizes-gm-data-sharing-ban-what-it-means-for-your-pri/image-1-1768484544378.jpg)