Verizon's FCC Phone Unlocking Waiver: What It Means for Your Device [2025]

Last year, something major happened in the wireless industry, and most people missed it entirely. The Federal Communications Commission quietly granted Verizon a waiver from its long-standing 60-day phone unlocking requirement, a rule that's been in place since 2008. On the surface, this sounds like a technical policy shift. In reality? It's a significant change in how long you might be locked into Verizon's network after buying a new phone.

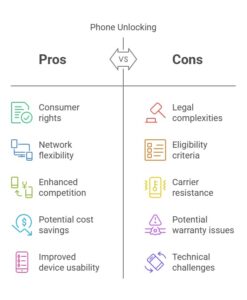

Let me be straight with you: This waiver could affect your ability to switch carriers, potentially limit your resale options, and fundamentally change the carrier flexibility you've had for over a decade. But the story is more nuanced than just "Verizon wins, customers lose." There are legitimate security concerns, competitive dynamics, and trade-offs worth understanding.

The decision caught many consumer advocates off guard. Verizon spent years arguing that the 60-day rule was creating incentives for theft and fraud, claiming criminals specifically targeted their phones because of the locked-in period. When the FCC agreed and granted the waiver, it marked a pivotal moment in how American carriers can manage device access. But here's the thing: the conversation around this waiver reveals deeper questions about device ownership, carrier lock-in, security trade-offs, and what happens when regulations designed to protect consumers start working against them in unexpected ways.

TL; DR

- The Waiver: The FCC eliminated Verizon's requirement to unlock phones 60 days after activation, replacing it with looser CTIA guidelines.

- New Rules: Verizon now unlocks phones only after contract expiration, device payment completion, or early termination fee payment.

- The Claims: Verizon argued the rule incentivized device theft and fraud targeting their network specifically.

- The Impact: Customers may face longer lock-in periods, affecting carrier switching flexibility and phone resale options.

- Industry Context: This decision could signal a broader shift away from FCC-mandated unlocking timelines across the wireless industry.

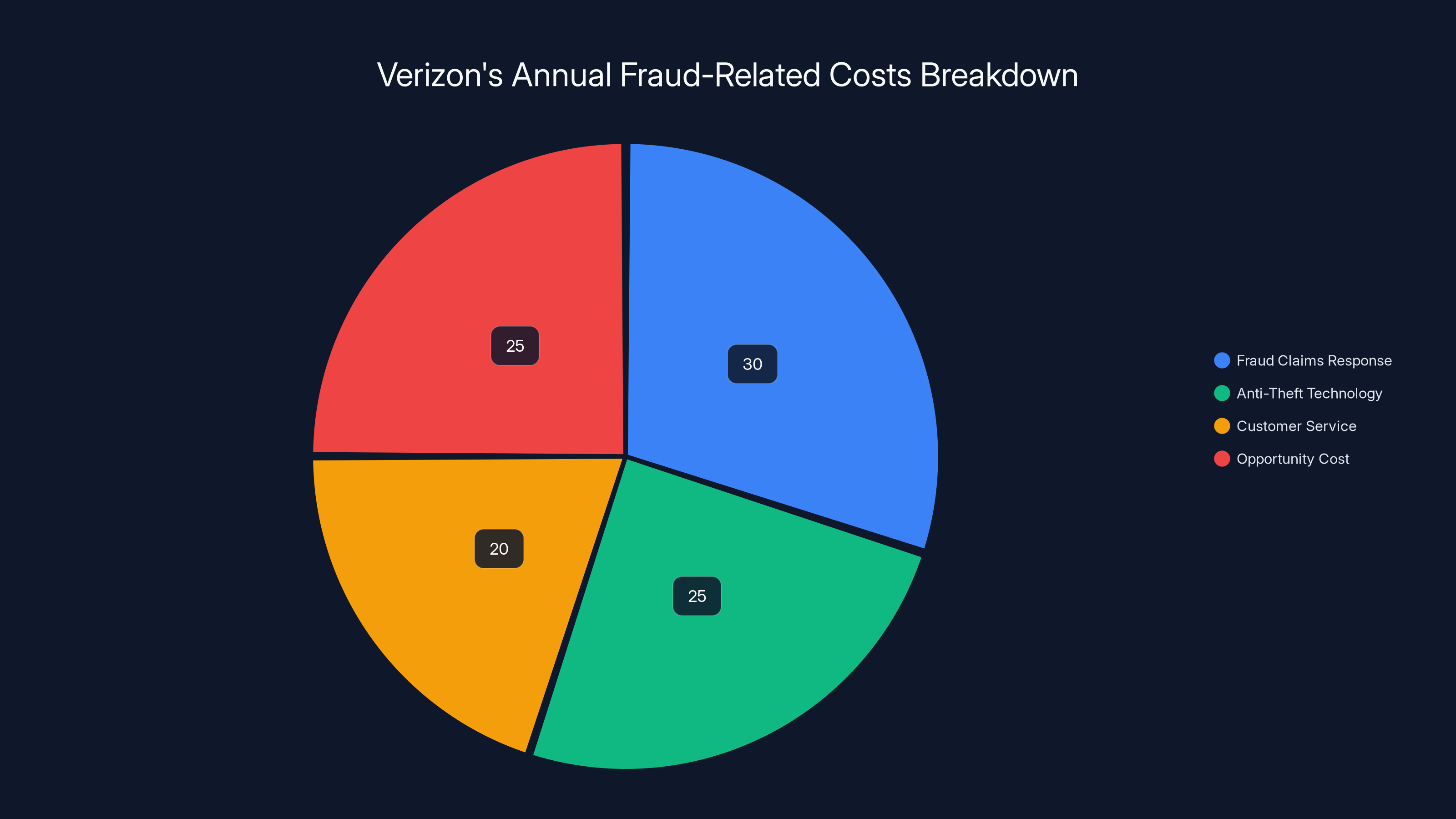

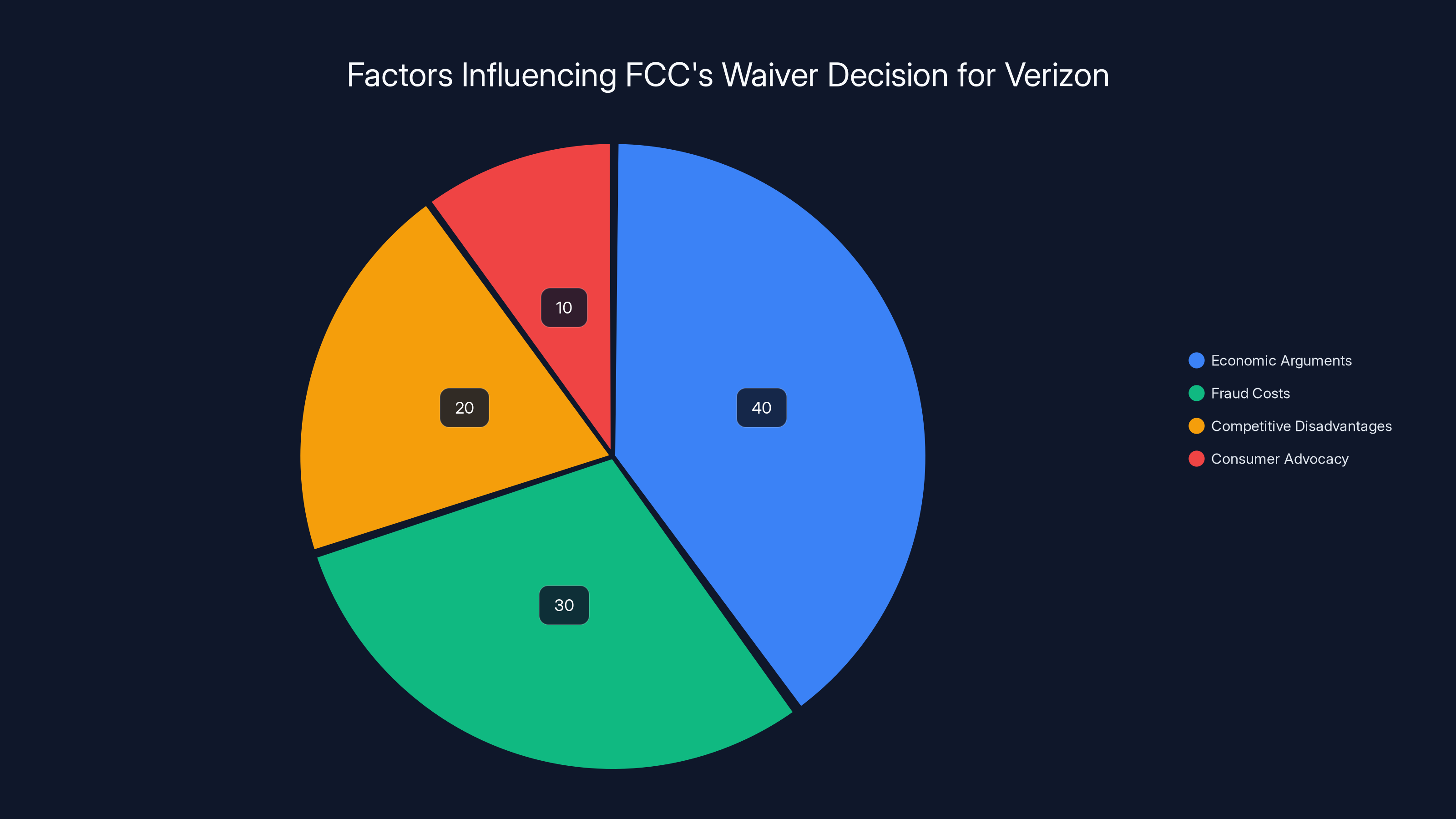

Estimated data shows that Verizon's costs related to combating device theft and fraud are distributed across various areas, with fraud claims response and opportunity costs each accounting for a significant portion.

What the 60-Day Rule Actually Was

To understand why this waiver matters, you need to know what the FCC required in the first place. Back in 2008, when Verizon purchased spectrum licenses in the 700 MHz band, the FCC attached strings. One of those strings was a requirement that Verizon unlock customer phones within 60 days of activation.

This wasn't some random number. The FCC was trying to solve a real problem: carrier lock-in. Before widespread unlocking requirements, customers were locked into their carriers for years. If you bought a phone through a two-year contract, you were stuck with that carrier's service for two years. Period. Switching meant losing your phone or paying hefty early termination fees.

The 60-day rule was designed as a middle ground. It gave carriers time to recoup their device subsidies (which were massive back in 2008), but it also gave customers a reasonable window to try the service and switch if it didn't work for them. You could activate a Verizon phone on January 1st, realize by early March that Verizon's coverage sucked in your area, and unlock your phone to use it on another carrier.

The rule made sense in that specific era. But wireless technology, business models, and fraud patterns have all evolved dramatically since 2008. Verizon's argument for the waiver hinges on these changes.

The Fraud Problem Verizon Claims

Here's where things get complicated. Verizon didn't ask for the waiver just to be difficult. The company presented data to the FCC arguing that the 60-day rule had created unintended consequences, specifically around device theft and fraud.

Specifically, Verizon's argument goes like this: Criminal networks know that any phone activated on Verizon will be unlocked within 60 days. This creates a clear window where stolen devices have maximum value. Thieves can steal a Verizon phone, activate it immediately (sometimes using stolen identification), and wait 60 days knowing the phone will be unlocked and sellable on the secondary market. The phone becomes a liquid asset with an expiration date.

According to the FCC's filing on this decision, Verizon claimed that "criminal networks are specifically targeting Verizon handsets due to the company's unique unlocking policies." The company presented evidence that it was experiencing disproportionate device theft compared to other carriers with different unlocking policies.

Now, here's the legitimate part of this argument: if you're a criminal operating a theft ring, you want predictability. You want to know exactly when the merchandise becomes valuable and sellable. A 60-day window creates that predictability. Other carriers with different unlocking policies might be less attractive targets.

Verizon went further, arguing that combating this theft was costing the company hundreds of millions of dollars annually. These costs come from multiple sources: actually responding to fraud claims, investing in anti-theft technology, customer service handling stolen phones, and the opportunity cost of not being able to implement more aggressive anti-fraud measures.

They also argued these costs came at the expense of network improvements and customer-friendly pricing. In their view, if they weren't burning money fighting fraud, they could invest those hundreds of millions into 5G infrastructure, coverage improvements, or lower prices.

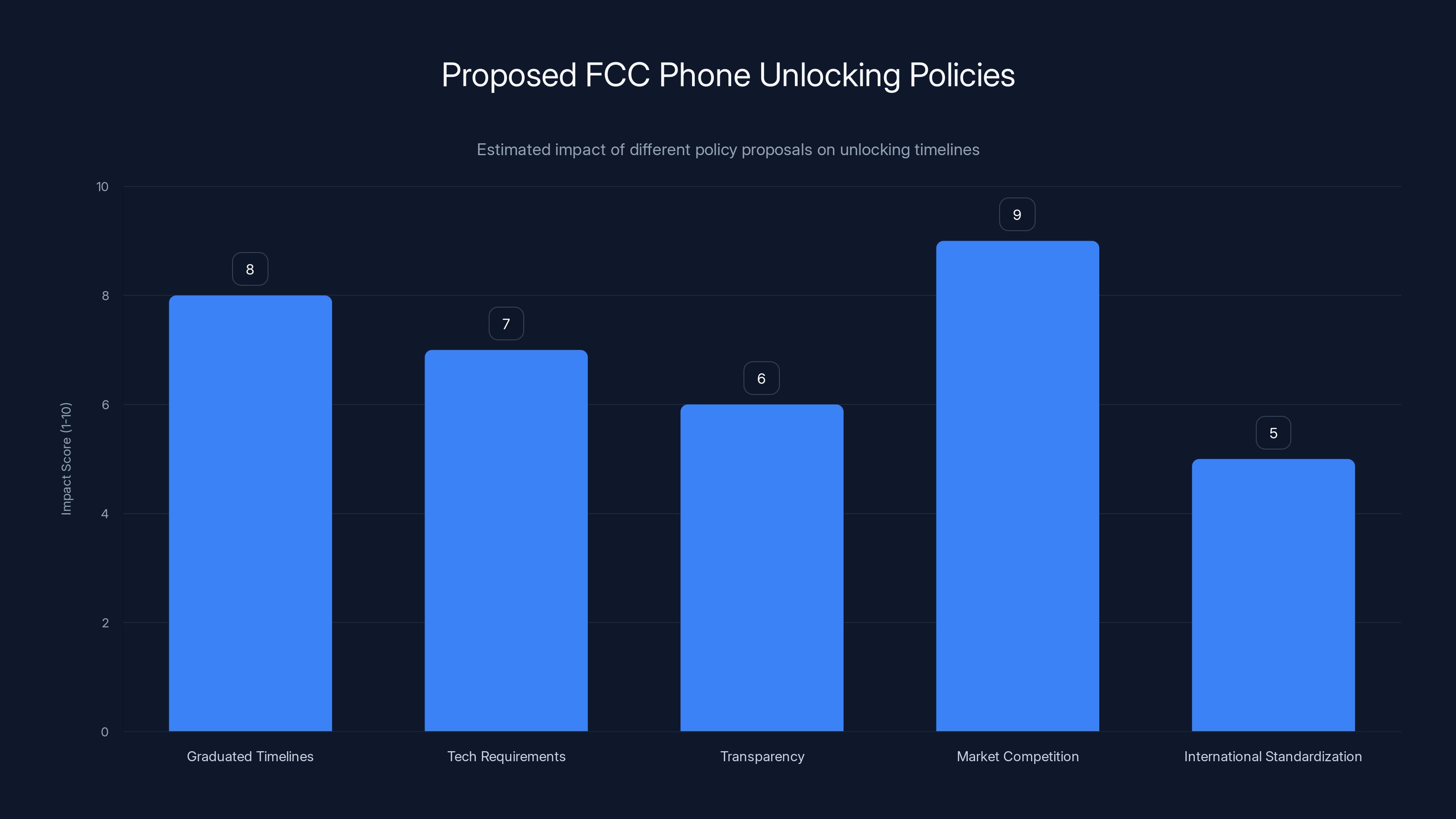

This chart estimates the potential impact of proposed FCC policies on phone unlocking timelines. Market competition is projected to have the highest positive impact. Estimated data.

How Other Carriers Handle Unlocking

Verizon isn't the only carrier in the U.S., and they don't all have identical unlocking policies. Understanding the competitive landscape helps explain why Verizon's argument resonated with the FCC.

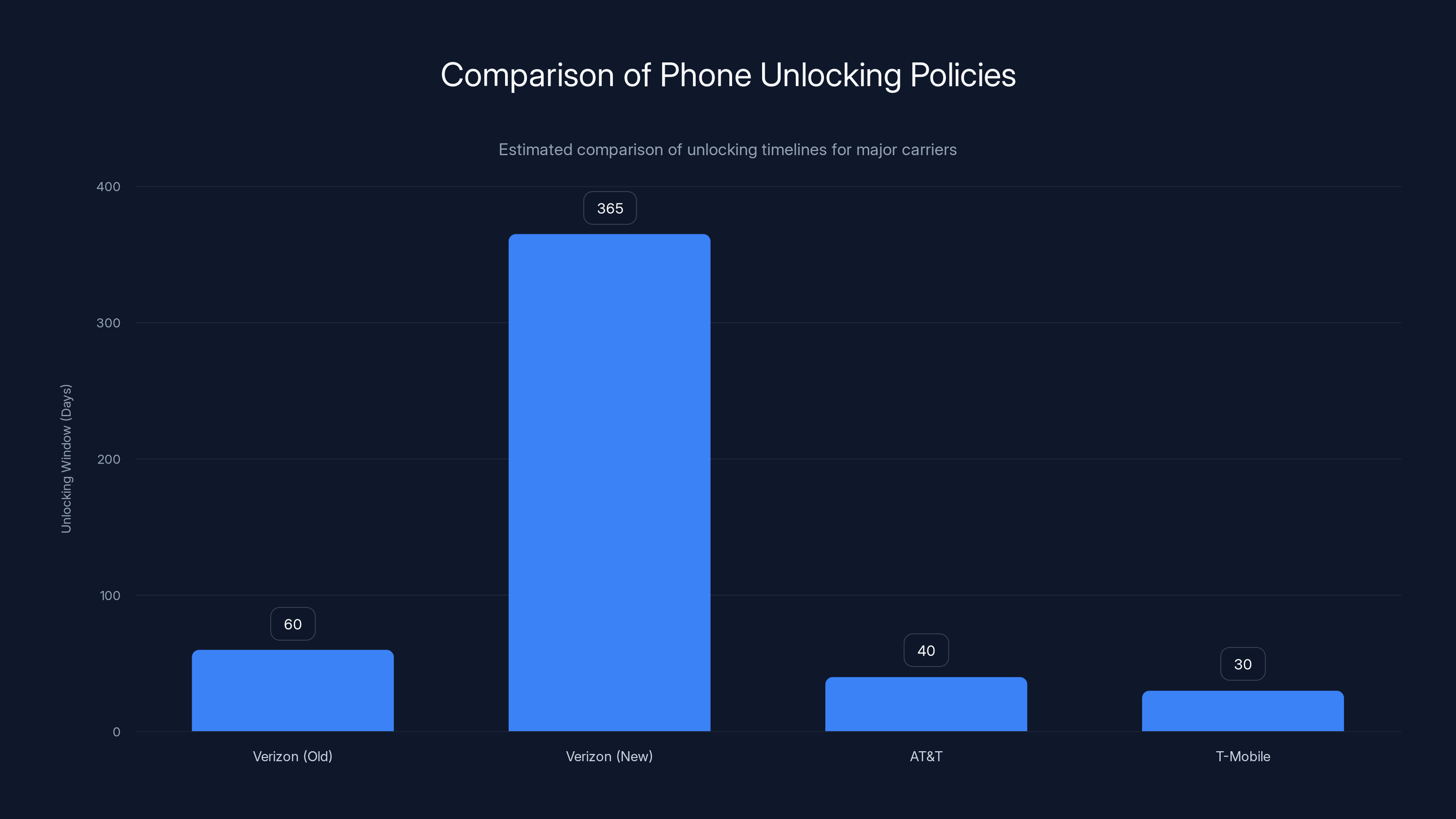

AT&T historically locked phones for 40 days after activation. This is shorter than Verizon's 60 days, which Verizon pointed out as a competitive disadvantage. If a thief can unlock an AT&T phone in 40 days but a Verizon phone in 60 days, Verizon becomes the more attractive theft target.

T-Mobile has been more flexible with unlocking, sometimes unlocking phones faster depending on account status and payment history. Sprint (before the T-Mobile merger) had similar flexible policies.

Internationally, the picture varies wildly. Some countries mandate same-day or next-day unlocking. Others allow carriers up to 180 days. The European Union has specific regulations around device unlocking, and Australia requires carriers to unlock phones at no charge after the contract expires.

Verizon's argument essentially was: "We're at a competitive disadvantage because criminals have figured out exactly how long they have to sell stolen phones." It's the kind of argument that sounds absurd at first, but actually makes logical sense once you think through the economic incentives criminals face.

The CTIA Guidelines: What Actually Replaces the Rule

So if the FCC eliminated the 60-day requirement, what does Verizon actually have to follow now? The answer is the CTIA code—a set of voluntary guidelines from the CTIA, which is the wireless trade group representing major U.S. carriers.

The CTIA code is significantly looser than the FCC's 60-day requirement. Here's what it actually says:

For postpaid phones (the standard monthly billing plans most people have): Carriers should unlock phones after one of three things happens:

- The contract expires

- The customer finishes paying off the device

- The customer pays an early termination fee

Notice the language: "should." This is a guideline, not a legal requirement. Carriers "should" follow it, but the CTIA has limited enforcement power compared to the FCC.

For prepaid phones: The guideline says carriers should unlock "no later than one year after initial activation." So Verizon could theoretically lock a prepaid phone for an entire year under these guidelines.

This is a massive departure from the 60-day rule. Under the old rule, you were guaranteed to be able to switch carriers 60 days after buying any phone. Under the new CTIA guidelines, you might wait months—or until your contract ends or you finish paying—before unlocking is possible.

Verizon claims it will follow these CTIA guidelines, but here's the issue: guidelines aren't rules. There's no FCC enforcement mechanism. If Verizon starts taking 120 days to unlock postpaid phones, there's no government agency with clear authority to stop them.

The Timeline: How We Got Here

The regulatory history here is important, because it shows how policy can shift when circumstances change. This didn't happen overnight.

2008: The FCC conditions Verizon's spectrum license purchase on the 60-day unlocking requirement. This is one of the earliest mandated unlocking rules in the U.S. wireless industry.

2013: The FCC requires all carriers to unlock phones within a certain timeframe as a standard practice, not just Verizon. But Verizon's 60-day requirement remains more restrictive than some competitors.

2022–2023: Verizon submits a request to the FCC asking for a waiver from the 60-day requirement. The company presents data on device theft, fraud losses, and competitive disadvantages.

2024: The FCC grants the waiver. Verizon no longer has to unlock phones within 60 days. The change takes effect one day after the FCC's official order releasing the decision.

2025: This is where we are now. The waiver is in effect, and the FCC says it will "remain in effect until the FCC decides on an appropriate industry-wide approach for the unlocking of handsets." Translation: This is temporary until the FCC figures out what to do across all carriers.

The FCC's language here is key. They're essentially saying: "We're letting Verizon do this, but we're not sure if this should be the standard for everyone." This creates uncertainty about what the industry will look like in a few years.

Estimated data shows Verizon's old policy had a 60-day unlocking window, while the new policy aligns with CTIA guidelines, potentially extending to 365 days. AT&T and T-Mobile have shorter unlocking windows.

What This Means for Your Phone: The Practical Impact

Let's cut through the policy language and talk about what actually changes for you if you buy a Verizon phone starting in 2025.

Switching carriers becomes more complicated. Under the old 60-day rule, you could activate a Verizon phone on day 1, and by day 61 you could unlock it and switch to AT&T, T-Mobile, or any other carrier. That pathway is now gone. Instead, you're looking at waiting until either your contract expires (if you're in a contract) or you finish paying off the phone (usually 24 months of monthly payments).

For most people buying phones in 2025, this means you're locked in for approximately 24 months, not 2 months. That's a 1200% difference.

Resale and trade-in values might be affected. If you're selling a used Verizon phone, one of the biggest factors in its value is whether it's unlocked. An unlocked phone can be sold to anyone. A locked phone can only be sold to Verizon customers or people willing to wait for unlocking. You'll likely get less for a locked device.

International travel might be trickier. If you travel frequently, you probably want to pop a local SIM card into your phone and use local service. A locked Verizon phone forces you to either use Verizon's expensive international roaming or carry a second device.

Early termination becomes more expensive. Some people upgrade their phones before their 24-month payment period is over. Under the old rule, you could at least unlock the old phone at 60 days. Now you might need to pay off the remaining balance or face early termination fees on both the new and old devices.

That said, the practical impact varies depending on your situation. If you never switch carriers, travel internationally, or sell your phones, you might not notice any difference at all.

The Security Trade-Off Nobody's Talking About

There's a legitimate security issue embedded in this policy change, and it deserves more attention than it typically gets.

Device theft has been a growing problem in the U.S. Smartphones are valuable, portable, contain personal data, and can be resold quickly. In 2023 and 2024, phone theft became such a problem that Apple and Google implemented kill switches in their operating systems, allowing users to remotely brick stolen phones.

Verizon's argument is that the 60-day unlocking window made their phones more attractive theft targets because stolen phones had a guaranteed resale window. By eliminating that window, they're making their phones less attractive to thieves. A stolen Verizon phone that won't unlock for months (or until payment is complete) is essentially worthless.

This is probably true. It probably does reduce Verizon phone theft. The question is whether that benefit is worth the downside for legitimate customers.

Here's where it gets thorny: the people who benefit most from faster unlocking are people who need to switch carriers quickly. This includes:

- People who move to areas with poor Verizon coverage

- Small business owners who want to consolidate carriers

- People in bad relationships needing to escape a shared family plan

- Migrants who need to switch to carriers serving their new home country

- Travelers needing local SIM cards

These are generally lower-income people or people in crisis situations. Meanwhile, phone thieves are criminals. So the policy trade-off is: Accept that thieves have easier access to stolen phones, in order to help people in difficult situations switch carriers quickly. Or eliminate the quick-switch option to make phones less attractive to thieves.

Verizon chose option two. You can debate whether that's the right call, but it's not obviously wrong.

Why the FCC Granted This Waiver (And What It Says About Regulatory Capture)

This is where things get a bit frustrating from a consumer perspective. The FCC's decision to grant Verizon's waiver raises questions about regulatory capture—the idea that industries can gradually influence the regulators that are supposed to oversee them.

Verizon is a massive company with an enormous legal team and significant lobbying resources. They presented a detailed case to the FCC with data, expert testimony, and economic arguments. They showed hundreds of millions in alleged fraud costs. They demonstrated competitive disadvantages. They made the case sound technical and inevitable.

Consumer advocacy groups didn't mount an equally resourced counter-campaign. There was no consumer group saying: "Wait, let's study this more carefully before letting Verizon lock phones for 24 months instead of 60 days." The decision happened relatively quietly, and by the time most people knew about it, it was already done.

The FCC's official reasoning in the waiver release mentions that the Commission was concerned about "deadweight loss"—a term meaning economic waste—costing Verizon hundreds of millions annually. The idea that a regulatory body is making decisions primarily on the basis of whether a corporation is experiencing "deadweight loss" is... worth thinking about.

That said, the FCC did include a stipulation: the waiver is temporary. The FCC says Verizon's exemption "will remain in effect until the FCC decides on an appropriate industry-wide approach for the unlocking of handsets." This suggests they're aware this might need to be revisited and that there's a possibility of broader regulatory action down the line.

But here's the catch: once a waiver is in place and a company has restructured its operations around it, reversing it becomes harder. Verizon will have built its security and anti-fraud operations around 180+ day unlocking windows. Going back to 60 days would require new systems and re-evaluation. Companies are very good at explaining why regulatory changes are now impossible, even when similar changes were impossible in the opposite direction years earlier.

Estimated data suggests economic arguments and fraud costs were major factors in the FCC's waiver decision, overshadowing consumer advocacy concerns.

How This Affects Different Verizon Customer Segments

Not every Verizon customer is equally affected by this waiver. The impact varies significantly depending on how you use your phone and whether you're likely to switch carriers.

Contract customers: If you have a traditional two-year contract (rare now, but still exists), you probably won't notice the difference. Your contract expires at approximately the same time you'd be making major decisions about switching carriers anyway. The 60-day rule was most useful for contract customers in the pre-unlocking era, but that's not how most of America buys phones anymore.

Device payment customers: This is where the impact is biggest. If you're financing a

Prepaid customers: These users might actually be hit harder. Under the new CTIA guidelines, prepaid phones can be locked for up to one year. That's a massive lock-in period for people who might be using prepaid specifically because they want flexibility.

Corporate/business customers: If you manage a fleet of Verizon phones for a company and you need to switch carriers, or move employees between carriers, the 60-day rule gave you flexibility. Now you're locked in until contracts or payments expire. For large companies, this is negotiated separately, so they might not be affected, but small businesses using standard consumer plans are affected.

International business travelers: If you frequently need to use local SIM cards abroad, the 60-day rule let you unlock new phones quickly. Now you're either locked in to Verizon's expensive international roaming or you need to wait until unlocking criteria are met.

What AT&T, T-Mobile, and Other Carriers Are Doing

One question everyone's asking: Will other carriers follow Verizon's lead?

AT&T hasn't requested a waiver and continues to operate under the 40-day unlocking policy we mentioned earlier. Interestingly, AT&T has been relatively quiet about phone theft in their public statements compared to Verizon. They might not see the same fraud problems, or they might be handling it differently through technical measures like kill switches.

T-Mobile has generally maintained more flexible unlocking policies, particularly for customers with good payment histories. They've been positioning themselves as the "carrier freedom" option versus more restrictive carriers, so requesting a waiver would undermine that messaging.

US Cellular (a smaller regional carrier) also hasn't requested a waiver, though smaller carriers face different competitive pressures than Verizon.

The interesting thing is that Verizon's waiver is specific to Verizon. The FCC didn't grant blanket permission for all carriers to extend unlocking periods. This means AT&T and T-Mobile still have to unlock faster than Verizon does. From a competitive perspective, this could actually give them an advantage: "Switch to AT&T and get unlocked 20 days faster."

But industry insiders are watching to see if other carriers submit similar waiver requests. If AT&T gets frustrated with the 40-day rule as Verizon was with the 60-day rule, they could make the same arguments. The FCC might feel obligated to treat all carriers equally, leading to industry-wide waiver of these requirements.

The Data Theft & Fraud Angle: Is Verizon's Argument Solid?

Let's examine Verizon's core claim more carefully: that the 60-day rule is causing device theft to be disproportionately targeting their phones.

The argument is internally consistent. Rational criminals would target phones that have the most value and the longest resale window. If Verizon locks for 60 days and AT&T locks for 40 days, Verizon phones are more valuable to thieves. The math checks out.

But there are some nuances worth considering:

Kill switches are now standard. Apple's Activation Lock and Google's Find My Device have made stolen phones much less valuable than they were a few years ago. If a thief steals an iPhone, the original owner can remotely brick it. This happened during the time Verizon was building their fraud case. So theft might be declining industry-wide regardless of unlocking policies.

Verizon's data is selective. The FCC filing mentions that Verizon experiences disproportionate device theft, but we haven't seen independent verification. Verizon has financial incentives to make their theft problem sound worse than it is. Independent research on whether Verizon phones are actually targeted more than other carriers would be helpful, but I'm not aware of comprehensive studies.

Lock-in creates other vulnerabilities. By making phones harder to unlock, Verizon might prevent some theft, but it also creates other problems. Locked phones are less valuable for legitimate resale, creating secondary market distortions. They're harder for owners to use internationally, limiting the market for used phones. These effects are harder to quantify than theft losses, but they're real.

Technology could solve this differently. Instead of longer lock-in periods, carriers could use device fingerprinting, biometric verification, or blockchain-based registration to reduce theft without limiting customer choice. Verizon didn't argue that these alternatives were impossible; they just argued that the 60-day rule was a source of fraud. Other solutions exist.

So is Verizon's argument solid? Partially. The logic is sound, the claimed impacts are plausible, and device theft is a real problem. But the argument is presented as the only solution, when alternatives exist and when some of Verizon's claimed impacts might be overstated.

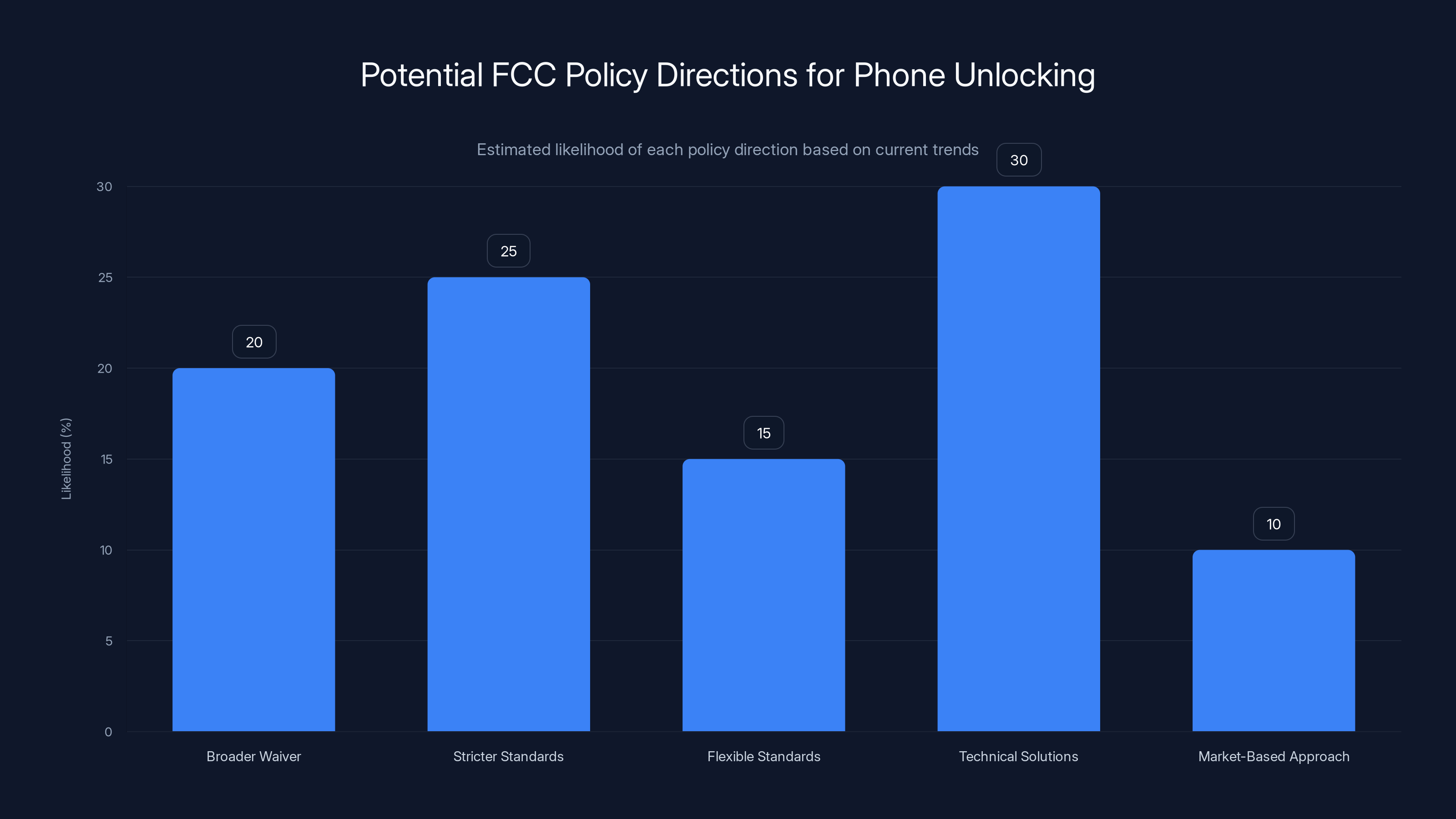

This chart estimates the likelihood of each potential FCC policy direction for phone unlocking. Technical solutions are seen as the most likely due to their consumer-friendly nature. (Estimated data)

The FCC's Temporary Waiver: What Does "Temporary" Actually Mean?

Here's something people often miss: the FCC explicitly said this waiver is temporary. The order states that it "will remain in effect until the FCC decides on an appropriate industry-wide approach for the unlocking of handsets."

This language is important. It means the FCC is not closing the book on phone unlocking policy. They're kicking the decision to some future date when they'll establish industry-wide standards.

So what might that future look like? A few possibilities:

Option 1: Broader Waiver for All Carriers. The FCC could decide that extended unlocking periods benefit all carriers equally and should be standard across the industry. This would essentially make Verizon's current terms the baseline.

Option 2: Stricter Standards. The FCC could study the fraud impacts and decide that the 60-day rule (or even shorter periods) should be enforced industry-wide. This would be a rebuke of Verizon and a consumer-friendly move.

Option 3: Flexible Standards. The FCC could establish unlock timelines based on phone type, payment status, or fraud risk profiles. Maybe locked phones for 30 days while in installment plans, but quicker unlocking once paid off.

Option 4: Technical Solutions. The FCC could decide that device-level security features (kill switches, biometric locks) are sufficient to prevent fraud, making carrier-level lock-in unnecessary. This would be the most consumer-friendly approach.

Option 5: Market-Based Approach. The FCC could step back entirely and let carriers compete on unlocking speed as a selling point. This assumes market competition is sufficient to prevent carriers from locking customers in excessively.

Which direction do you think is most likely? Honestly, it's hard to say. The fact that the FCC granted Verizon's waiver suggests they're open to carrier flexibility. But consumer groups are already pushing back, and Congress occasionally gets involved in telecom issues when there's enough public attention.

International Perspectives: How Other Countries Handle This

It's useful to look beyond the U.S. to understand how different regulatory approaches work in practice.

The European Union requires carriers to unlock phones within 12 months of purchase, or immediately after the contract expires, whichever comes first. This is a middle ground—it gives carriers time to recoup device costs but ensures customers can switch relatively quickly.

Australia goes further, requiring carriers to unlock phones free of charge after the contract expires or minimum payment period is fulfilled. They specifically prohibited carriers from charging unlocking fees, which some U.S. carriers previously did.

Canada is similar to Australia, with regulatory requirements for relatively quick unlocking (typically 30 days after being asked).

South Korea has mandated same-day or next-day unlocking in some cases, though regulations vary by carrier and phone type.

Japan has carrier lock-in laws that allow carriers to lock phones, but require them to unlock upon request during reasonable timeframes.

The global pattern is clear: most developed countries mandate faster unlocking than what Verizon is now allowed to do under the waiver. The U.S. is actually moving toward a less consumer-friendly model than most of the developed world.

That said, international carriers also face different fraud pressures and different market structures. Verizon's argument about theft might be valid given the specific U.S. market dynamics, even if other countries have chosen different trade-offs.

What This Means for the Secondary Market & Phone Resale

One of the less-discussed impacts of the waiver is what it means for buying and selling used phones.

If you've ever sold a used phone online, you know that locked vs. unlocked makes a huge difference in price. An unlocked iPhone might sell for

Under the old 60-day rule, a phone purchased from Verizon would be unlocked within two months, meaning used phones sold after that point would be unlocked and valuable. Under the new rules, a phone might not unlock for 24 months or more, so used phones sold in year one will likely be locked and less valuable.

This creates a few effects:

Reduced incentives for upgrades. If your old phone is worth

Price floors for used devices. Locked phones establish a lower price floor based on their "locked and waiting" state. This affects everyone in the secondary market, not just Verizon customers.

Less phone diversity in the used market. Some people buy used Verizon phones to use on other carriers. If those phones take forever to unlock, this market shrinks. This affects people buying used phones on a budget or in developing markets.

Trade-in dynamics change. Verizon's own trade-in programs might be affected. If a customer trades in a locked phone that will take months to unlock, Verizon gets stuck with the inventory management problem.

The secondary phone market is worth tens of billions of dollars globally. This policy change ripples through that entire ecosystem.

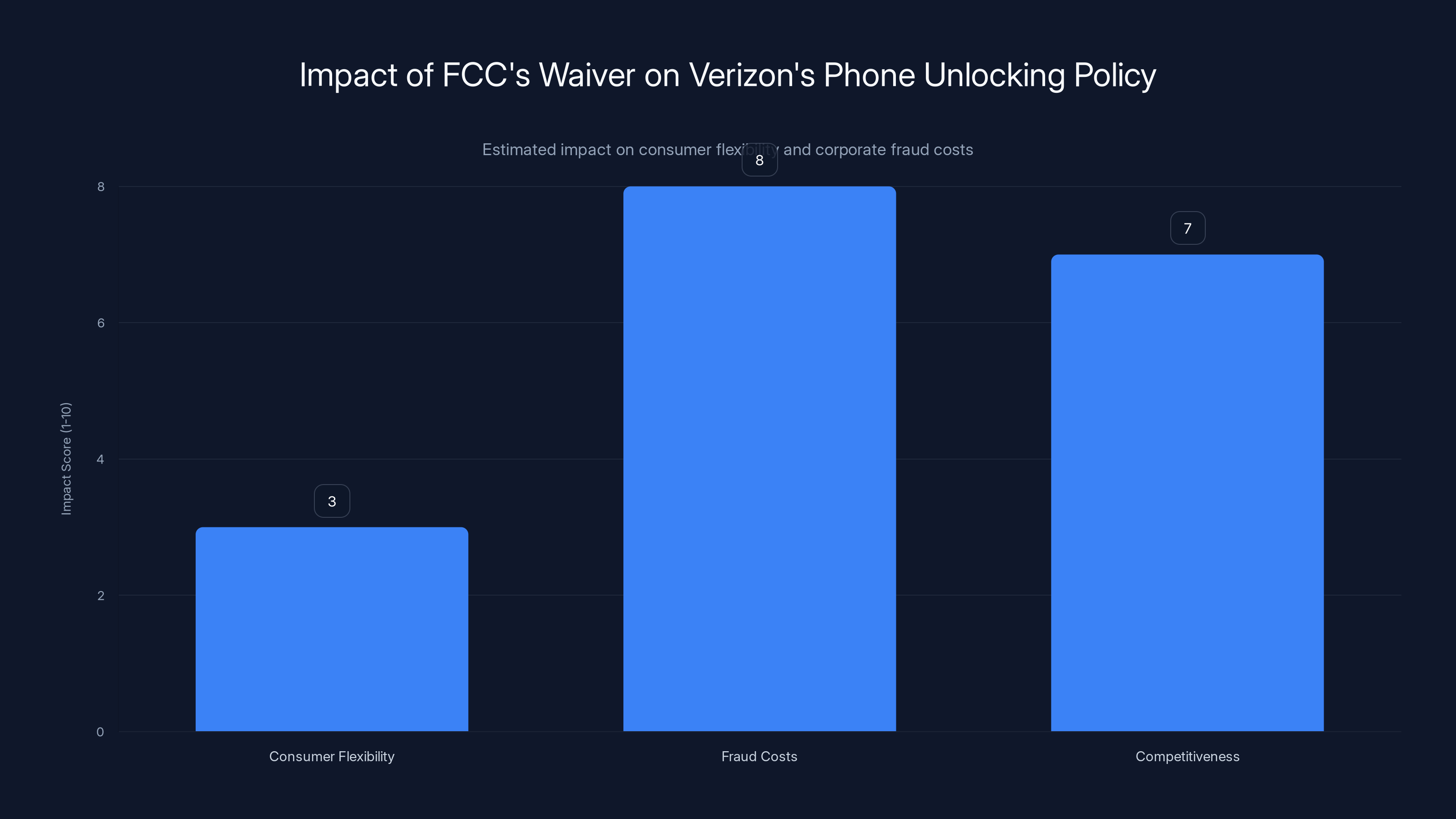

Estimated data shows that while the waiver significantly reduces fraud costs (score: 8) and improves competitiveness (score: 7), it negatively impacts consumer flexibility (score: 3).

Employee & Contractor Implications: Business Phone Management Gets Harder

Small and medium-sized businesses that use Verizon for employee phones are watching this waiver closely.

Let's say you're a construction company with 20 employees, each carrying a Verizon phone. You've got good coverage in most areas, but you're thinking about switching to T-Mobile because they're cheaper. Under the old 60-day rule, you could activate all 20 phones on Verizon, evaluate the service, and if it didn't work, unlock them at day 61 and switch everyone to T-Mobile.

Under the new rules, you're locked in until contracts/payments expire. This reduces your ability to switch carriers responsively. It effectively gives Verizon a 24-month customer retention advantage just from the switching friction.

Large companies (1,000+ employees) have different contracts and can negotiate custom terms, but mid-market businesses (50-500 employees) are stuck with standard consumer terms. This effectively locks them in.

For contractor networks (think: home improvement services where workers use company phones), the lock-in period makes it harder to respond to service issues. If a contractor has poor coverage in a region, it now takes months to resolve instead of weeks.

The Fraud Triangle: Carriers, Customers, and Criminals

Understanding this waiver requires understanding the three-way dynamic between carriers (Verizon), legitimate customers, and criminals (phone thieves and identity fraudsters).

Verizon is trying to make their phones less attractive to criminals. They're saying: "If you steal a Verizon phone, it won't be sellable for months because it'll stay locked. So steal an AT&T phone instead."

But this strategy has costs:

- It inconveniences legitimate customers who want to switch carriers

- It reduces resale value for people selling used phones

- It creates inventory management problems for Verizon (they get locked phones back through trade-ins and can't easily resell them)

- It might not even work if criminals shift to other carriers instead of stopping theft entirely

The fundamental issue is that Verizon is trying to solve a crime problem with a regulation that affects everyone. It's like saying: "To prevent car theft, we're going to make cars harder to sell, so thieves won't want to steal them." It might work for cars, but the side effects are significant.

A more targeted approach might be: "Let's invest in anti-theft technology (kill switches, biometrics, registration systems) that prevents phones from being used after theft, regardless of unlocking status." This solves the crime problem without the side effects.

But developing anti-theft technology costs money and technical resources. Requesting an FCC waiver costs lawyers and lobbyists. Verizon chose the easier path.

What Happened to the Promise of Device Unlock Laws?

There's a broader story here about U.S. telecommunications law and the promise of unlocking.

For decades, carriers locked phones to their networks. You bought an iPhone from Verizon, it worked on Verizon and nowhere else. This lock-in was a huge source of carrier revenue because it forced people to stay on their networks.

In the early 2010s, there was a big push to unlock phones. Activists, small carriers, and some lawmakers argued that customers should own their devices and be able to use them anywhere. It was framed as a freedom issue: "You bought it, you should own it."

The FCC and Congress eventually responded with unlocking rules. The idea was: We'll require carriers to unlock phones so customers have freedom and flexibility.

But now, 15+ years later, Verizon is successfully asking to roll back those protections, and they're doing it with an argument about fraud and theft. It's a reminder that regulatory protections are never permanent. They can be rolled back if companies make the right arguments to the right regulators.

This should matter to anyone who cares about digital freedom. If Verizon wins this argument, and other carriers follow, we could slowly slide back toward a world where device lock-in is the norm again. The pitch will just be different: not "we want to keep you as customers," but "we need to fight fraud."

Preparing for a Locked-Phone Future: What Should You Do?

If you're buying a new Verizon phone in 2025, what are your options?

Option 1: Accept the lock-in. If you're the type of customer who stays with one carrier for years and doesn't switch, this doesn't affect you. Just buy the phone, use it for 24 months, and move on.

Option 2: Negotiate faster unlocking. If you're a customer with a significant account (multiple lines, high spending), you might be able to ask Verizon customer service for faster unlocking. Big companies do this; individuals can try.

Option 3: Buy unlocked phones directly. Instead of buying a subsidized Verizon phone, buy an unlocked phone outright from Apple, Google, or a retailer. You'll pay full price (usually

Option 4: Use eSIM alternatives. eSIM technology allows you to switch carriers virtually without changing the physical SIM card. Verizon's locked phone still works with eSIM switching in some cases, depending on the phone and region.

Option 5: Buy from a competitor. If carrier flexibility matters to you, buy an AT&T or T-Mobile phone instead. AT&T's 40-day rule is shorter than Verizon's, and T-Mobile's policies are more flexible.

Option 6: Wait for the FCC's next move. If you don't urgently need a new phone, waiting 6-12 months to see if the FCC makes any broader policy changes might be worth it. This is low-impact if you're already on an old phone.

None of these options are perfect. They all involve trade-offs between cost, convenience, and flexibility. But understanding your options puts you in a better position to make an informed decision.

Looking Ahead: What Could the FCC Do?

The FCC's waiver for Verizon is temporary. At some point—maybe in 2026, maybe later—the FCC will decide what the industry-wide approach should be for phone unlocking.

What would a smart policy look like? Here's what I'd argue for:

Graduated unlocking timelines. Different rules for different situations. Unlocked within 30 days for customers who've paid off the full device. Unlocked after contract expiration. Unlocked faster (5-10 days) if the customer is switching carriers and asks for it.

Technology-based requirements. Rather than time-based rules, require carriers to implement anti-theft technology (kill switches, registration systems) that reduces fraud without requiring lock-in.

Transparency and reporting. If carriers claim fraud is costing them hundreds of millions, require them to publish actual fraud statistics so the public can see the real impact.

Market-based competition. Let carriers compete on unlocking speed as a differentiator. Some carriers could offer 30-day unlocking as a selling point. This creates competitive pressure for consumer-friendly policies without requiring regulation.

International standardization. Align U.S. rules with international norms (like the EU's 12-month rule) so that global phone markets work more smoothly.

But I'm an optimist. In reality, the FCC might just extend Verizon's waiver to all carriers, making the current situation permanent. Or they might let each carrier negotiate its own terms, creating a fragmented landscape. Policy often moves slowly and in directions that benefit incumbents.

The Bigger Picture: What This Reveals About Regulation

Zoom out, and the Verizon waiver tells us something broader about how regulation works in America in 2025.

Large corporations can hire armies of lawyers and economists to make sophisticated arguments to regulators. They can present data, case studies, and economic analyses showing why their specific problem requires regulatory flexibility. If the regulatory agency agrees (especially if consumer advocacy isn't equally resourced), the company gets what it wants.

Over time, this creates a ratchet effect. Regulations loosen incrementally as companies argue their individual cases. Each individual loosening seems justified. But the cumulative effect is that regulations that existed for good reasons gradually disappear.

This isn't necessarily corruption. The FCC officials who approved Verizon's waiver probably genuinely believed the fraud problem was significant and that the waiver was justified. But it's an example of how regulatory protections erode in the absence of organized opposition.

For consumers, the takeaway is: Regulations that protect you (like the 60-day unlocking rule) are valuable, but they're also fragile. They can be dismantled with the right arguments. Protecting those rules requires ongoing attention and advocacy.

And for those who care about digital freedom and device ownership, the Verizon waiver is a reminder that these principles have to be actively defended. They don't stay in place on their own.

FAQ

What exactly is the FCC's 60-day phone unlocking rule?

The 60-day phone unlocking rule was an FCC requirement that Verizon unlock customer phones within 60 days of activation. This rule was attached to Verizon's spectrum license purchase in 2008 and was designed to give customers a window to try Verizon's service and switch carriers if needed. The rule ensured that if you bought a Verizon phone on January 1st, it would be unlocked by approximately March 1st, allowing you to use it on any carrier.

How did Verizon justify requesting the waiver?

Verizon argued that the 60-day unlocking window created incentives for device theft and fraud because criminals knew they had a predictable timeline before stolen phones would be unlocked and sellable. The company claimed that criminal networks specifically targeted Verizon phones because of this unique policy. Verizon presented data suggesting the rule cost them hundreds of millions of dollars annually in fraud-related losses and prevented them from investing those resources into network improvements and consumer benefits. Verizon also noted competitive disadvantages since other carriers like AT&T had shorter unlocking windows (40 days).

What are the new rules for unlocking Verizon phones after the waiver?

Under the waiver, Verizon now follows the CTIA code rather than the 60-day FCC requirement. This means postpaid phones unlock only after: the contract expires, the customer finishes paying off the device, or the customer pays an early termination fee. For prepaid phones, the guideline allows unlocking "no later than one year after initial activation." Importantly, these CTIA guidelines are voluntary industry standards, not legally enforceable FCC rules, meaning Verizon's compliance is based on their commitment to the code rather than regulatory enforcement.

How does this waiver affect my ability to switch carriers?

The waiver significantly reduces your carrier flexibility. Under the 60-day rule, you could unlock a Verizon phone after 2 months and switch to AT&T, T-Mobile, or any competitor. Under the new rules, you're effectively locked in until you finish paying off the phone (typically 24 months) or your contract expires. If you want to switch carriers before payment is complete, you'd need to either pay off the remaining device balance upfront or wait months for the phone to eventually unlock based on CTIA guidelines.

Will other carriers like AT&T or T-Mobile do the same thing?

AT&T has not requested a waiver and continues to operate under a 40-day unlocking requirement, which is actually more consumer-friendly than Verizon's new situation. T-Mobile has generally maintained flexible unlocking policies and is positioning itself as the "carrier freedom" option, so requesting a waiver would undermine that brand positioning. However, industry observers are watching to see if other carriers will follow Verizon's lead by submitting their own waiver requests. The FCC might feel obligated to treat all carriers equally if multiple requests are submitted, potentially creating industry-wide changes in unlocking timelines.

Is this waiver permanent, or could it be reversed?

The waiver is explicitly temporary. The FCC stated that Verizon's exemption "will remain in effect until the FCC decides on an appropriate industry-wide approach for the unlocking of handsets." This means the FCC is planning to revisit phone unlocking policy in the future and establish broader standards. However, once companies restructure their operations around a waiver, reversing it becomes politically and operationally difficult, even if the FCC theoretically has the authority. The future direction could go multiple ways: the FCC could grant broader waivers to all carriers, impose stricter unlocking standards, or develop alternative approaches using technology-based solutions rather than time-based requirements.

How does this affect used phone resale value?

The waiver negatively impacts used phone resale value because locked phones are worth significantly less than unlocked phones. An unlocked iPhone might sell for

What's the international approach to phone unlocking?

Most developed countries require faster unlocking than what Verizon is now allowed to do. The European Union requires unlocking within 12 months or when the contract expires. Australia and Canada require carriers to unlock phones free of charge after contract expiration. South Korea mandates next-day or same-day unlocking in some cases. Japan requires unlocking within reasonable timeframes upon request. Japan's approach actually puts the U.S. at a competitive disadvantage for global phone standards, as American devices now have longer lock-in periods than devices in most other developed markets.

Why is device theft claimed to be specifically targeting Verizon phones?

Verizon's argument is based on economic logic and predictability. If a thief steals a Verizon phone, they know it will unlock within 60 days, creating a guaranteed resale window and making the device valuable. If AT&T phones unlock in 40 days, those are less attractive theft targets. Rational criminals would theoretically prefer to steal Verizon phones because the predictable 60-day window creates maximum resale value. Verizon presented data claiming disproportionate device theft targeting their network specifically, though independent verification of this claim is limited. The argument is plausible but not definitively proven, and it overlooks that Apple's kill switches and Google's Find My Device have made stolen phones significantly less valuable regardless of carrier unlocking policies.

Conclusion

The FCC's decision to waive Verizon's 60-day phone unlocking requirement is a pivotal moment in U.S. telecommunications policy, even if it didn't get the media attention it deserved. On the surface, it's a technical policy change benefiting one corporation. But the decision reveals deeper patterns about how regulations work, how corporate advocacy influences regulatory bodies, and what it means when protections designed to help consumers gradually erode.

Verizon made a sophisticated argument: The 60-day rule is costing us hundreds of millions in fraud losses and making our phones disproportionate theft targets. Our competitors have shorter unlocking windows. To compete effectively and protect our customers from theft, we need flexibility. The FCC, apparently convinced, agreed.

There's legitimate logic to this argument. Device theft is a real problem. Fraud does cost carriers significant money. And it's true that if all carriers have the same unlocking timelines, Verizon wouldn't be at a disadvantage. The problem is that the solution—locking customers into longer periods—creates its own costs that don't appear in Verizon's fraud statistics.

For you as a customer, this means your wireless flexibility just got more limited. If you buy a Verizon phone in 2025, you're probably locked in for approximately 24 months instead of 2 months. You'll have less ability to quickly switch carriers if service degrades, less flexibility for international travel, and you'll get less money when you sell your used phone.

But it's not all dark. The FCC explicitly said this is temporary. This waiver is not permanent policy. At some future date, the FCC will decide on an industry-wide approach, and the decision could go different directions. Consumer advocacy groups are already pushing back. Congress occasionally gets involved in telecommunications issues. Change is possible.

The broader lesson is that regulatory protections you might take for granted—like the right to unlock the phone you bought—are actually fragile. They exist because someone fought for them decades ago. And they can be dismantled if companies make the right arguments to the right regulators and nobody organizes a counter-argument.

For anyone who cares about device ownership, digital freedom, and the ability to switch between service providers, the Verizon waiver should be a wake-up call. These principles have to be actively defended. They don't stay in place on their own. The phone in your pocket is more locked down than it was a year ago, and you might not have even realized it happened. Now you do. What you do with that knowledge is up to you.

Key Takeaways

- The FCC waived Verizon's 60-day phone unlocking requirement, allowing the carrier to lock phones longer until contracts expire or devices are fully paid off.

- Verizon argued the 60-day rule incentivized device theft and fraud costing hundreds of millions annually, though independent verification is limited.

- Customers now face approximately 24-month lock-in periods instead of 60 days, significantly reducing carrier switching flexibility.

- The waiver is temporary and the FCC will eventually establish industry-wide standards, which could restore protections or make the change permanent.

- International markets already require faster unlocking, putting U.S. customers at a disadvantage compared to EU, Australia, Canada, and other developed nations.

Related Articles

- Amazon's Buy for Me AI: The Controversy Shaking Retail [2025]

- Complete Guide to New Tech Laws Coming in 2026 [2025]

- SMS Scams and How to Protect Yourself: Complete Defense Guide [2025]

- New York's Social Media Warning Labels Law: What You Need to Know [2025]

- DoorDash Food Tampering Case: Gig Economy Safety Crisis [2025]

![Verizon's FCC Phone Unlocking Waiver: What It Means for Your Device [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/verizon-s-fcc-phone-unlocking-waiver-what-it-means-for-your-/image-1-1768327633948.jpg)