The Quiet Shift Reshaping AI Interfaces

Something significant just happened in the AI world, and most people barely noticed. Google doesn't usually hire startup teams this way. When a tech giant starts acquiring talent rather than companies, it signals something larger is underway. The company just brought on the CEO and roughly seven senior engineers from Hume AI, a voice-focused AI startup that raised nearly

This isn't a traditional acquisition. It's what the industry calls an "acquihire," and it's become increasingly common as big tech firms compete for specialized talent while sidestepping regulatory scrutiny. But the real story here isn't about corporate consolidation. It's about what this move reveals about the future of how humans interact with AI.

Voice is winning. Not as a niche feature or accessibility tool, but as the primary interface for AI interactions. Screens are being relegated to secondary status. This shift has massive implications for product development, startup strategy, business models, and how we'll work with AI in the next five years.

Let's dig into what's happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

Understanding the Hume AI Acquisition

What Actually Happened

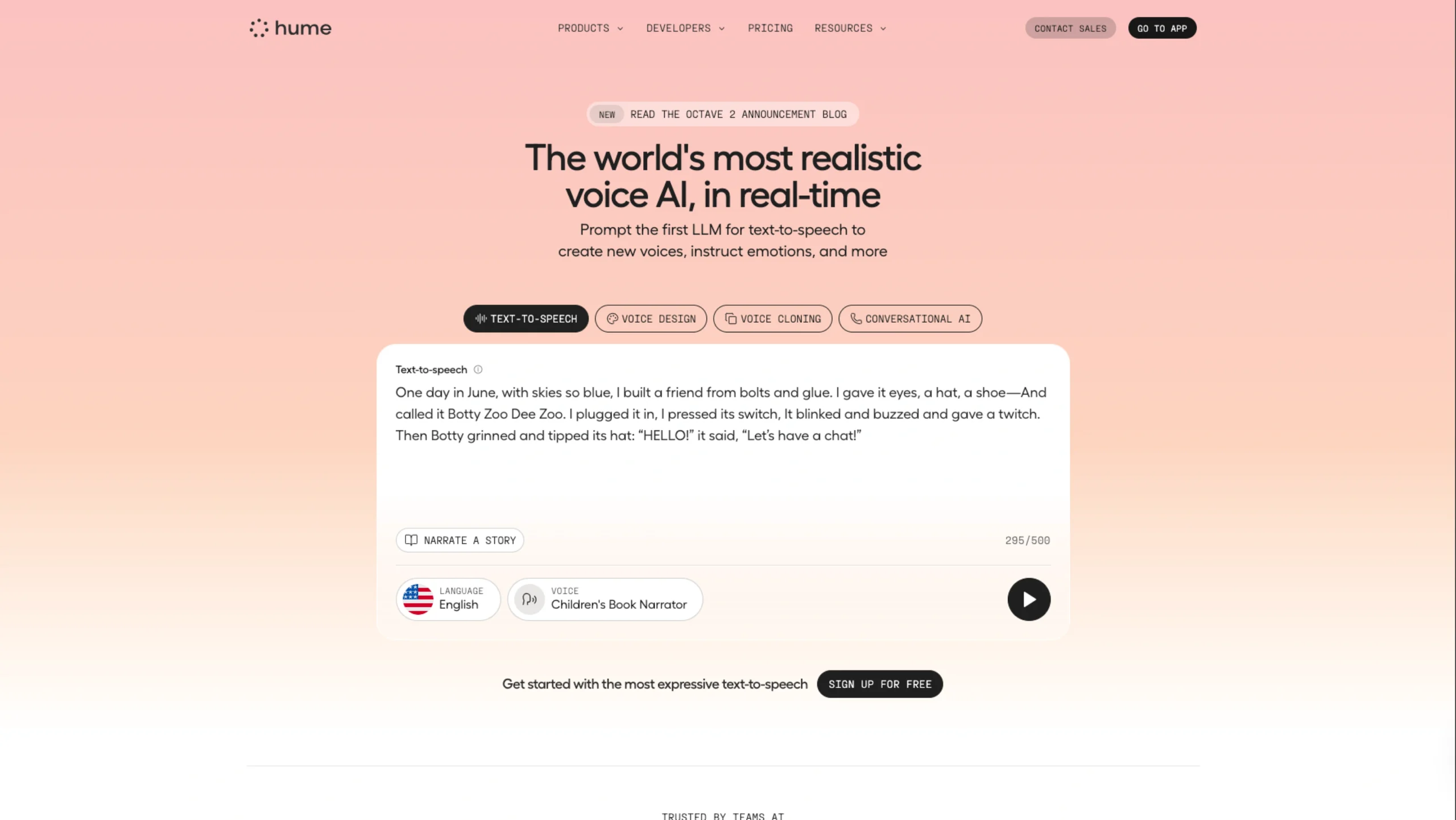

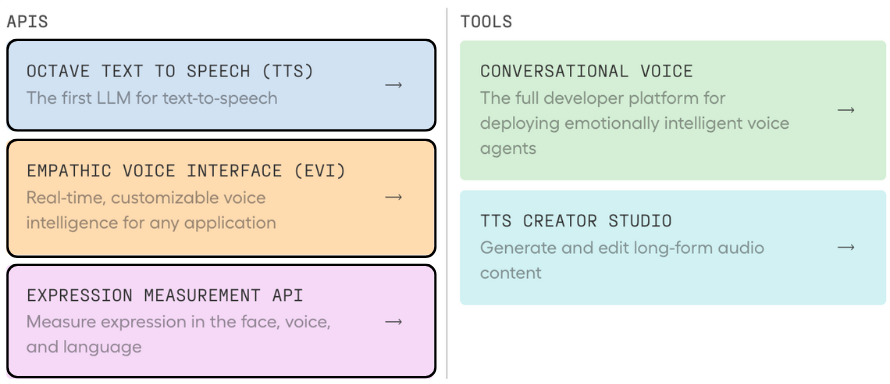

Google Deep Mind entered into a licensing agreement with Hume AI that includes bringing the startup's CEO Alan Cowen and approximately seven other top engineers onto the Google team. The remaining Hume AI organization continues operating as an independent company, licensing its technology to other AI firms. No financial terms were disclosed, but the structural arrangement tells you everything about priorities.

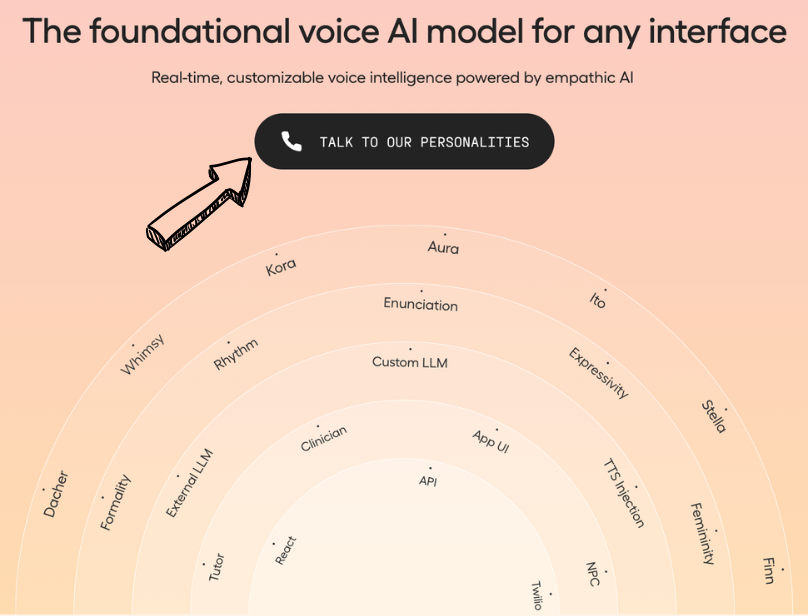

Google didn't want the whole company. It wanted the people and the ideas. Hume AI's core expertise centers on something most voice AI companies barely touch: understanding human emotion and mood through voice analysis. The startup built what it calls an "Empathetic Voice Interface," essentially conversational AI that picks up on emotional context from vocal tone, pace, emphasis, and other acoustic features.

The deal represents Google's strategic acknowledgment that voice interfaces demand specialized talent. You can't just bolt a voice feature onto an existing chatbot. You need teams that understand acoustic analysis, prosody, emotional inference, and conversation design at a fundamental level. Hume AI had built exactly that expertise.

Why Google Chose This Structure

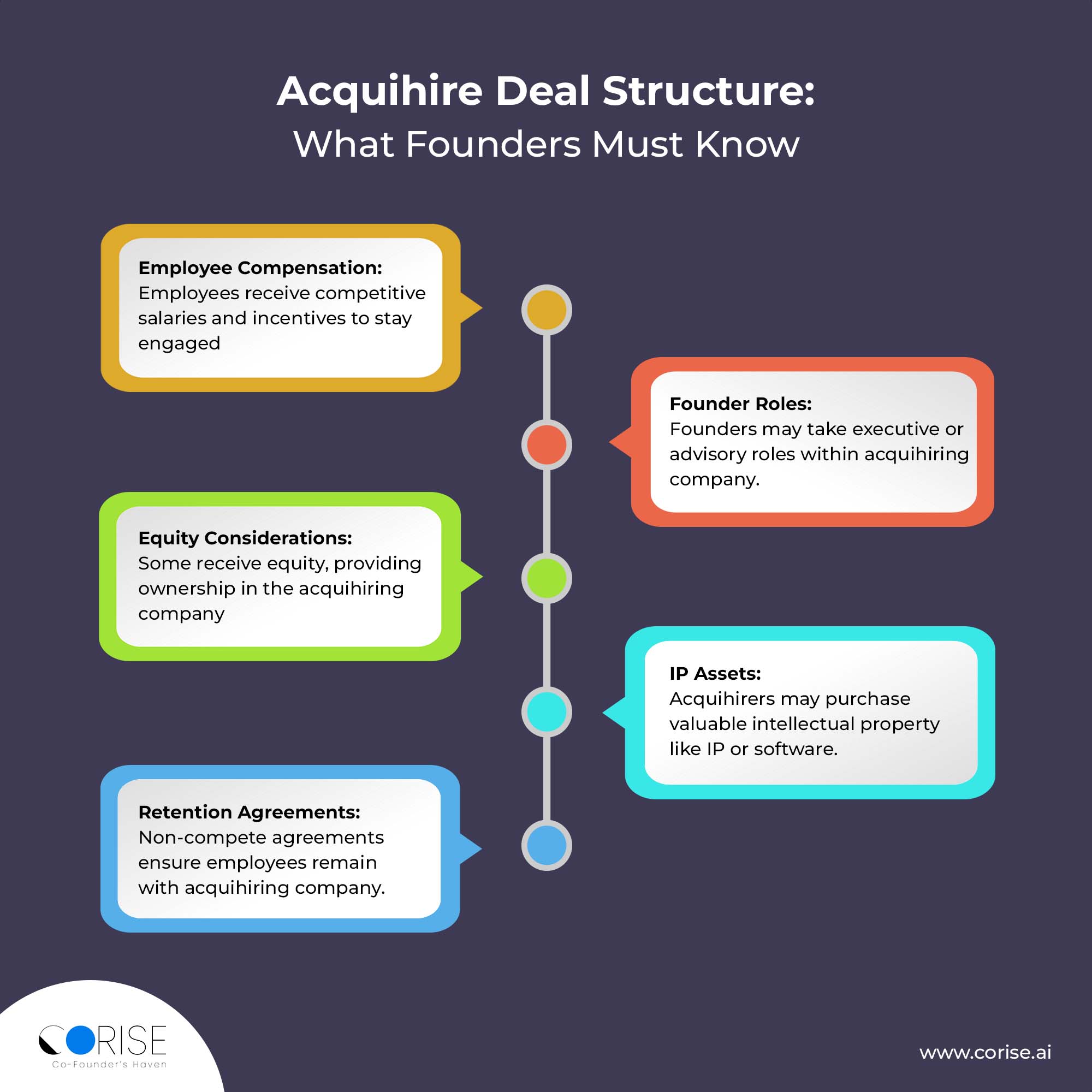

Traditional M&A involves buying the whole company, integrating systems, and often shipping most of the talent within six months. An acquihire works differently. You grab the core team, pay them directly, integrate them into your organization, and let the original company either shut down or pivot to something else.

This approach has become popular because it solves several problems simultaneously. First, regulatory bodies like the FTC have started scrutinizing AI acquisitions more carefully. An acquihire can appear less like a traditional merger and more like hiring top talent. Second, you avoid inheriting legacy systems, contracts, and infrastructure you don't need. Third, you send a market signal: we value talented people more than we value ownership.

The FTC recently indicated it would increase scrutiny on these deals, suggesting they may soon become harder to execute. For now, Google's move represents a window that's slowly closing.

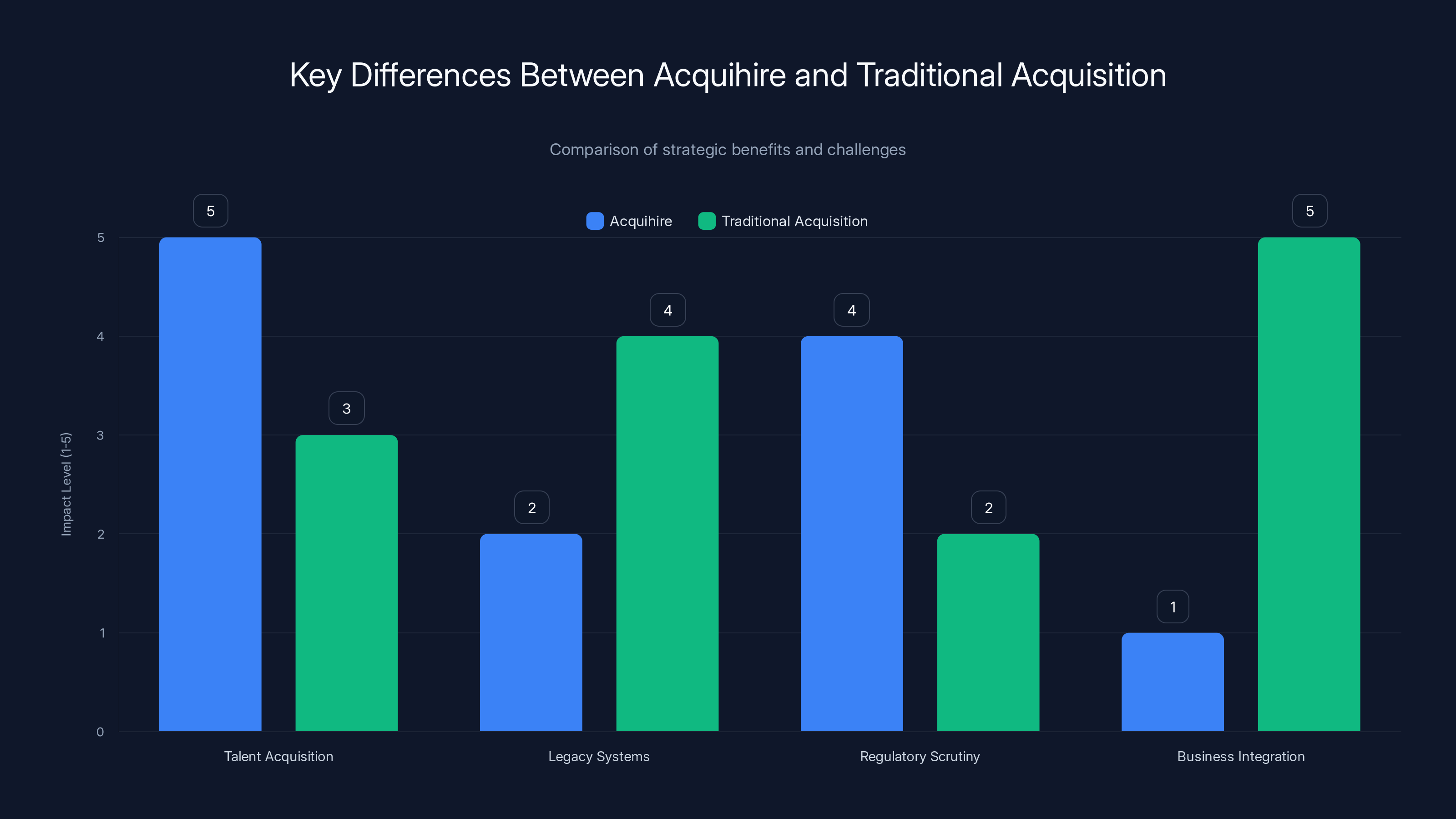

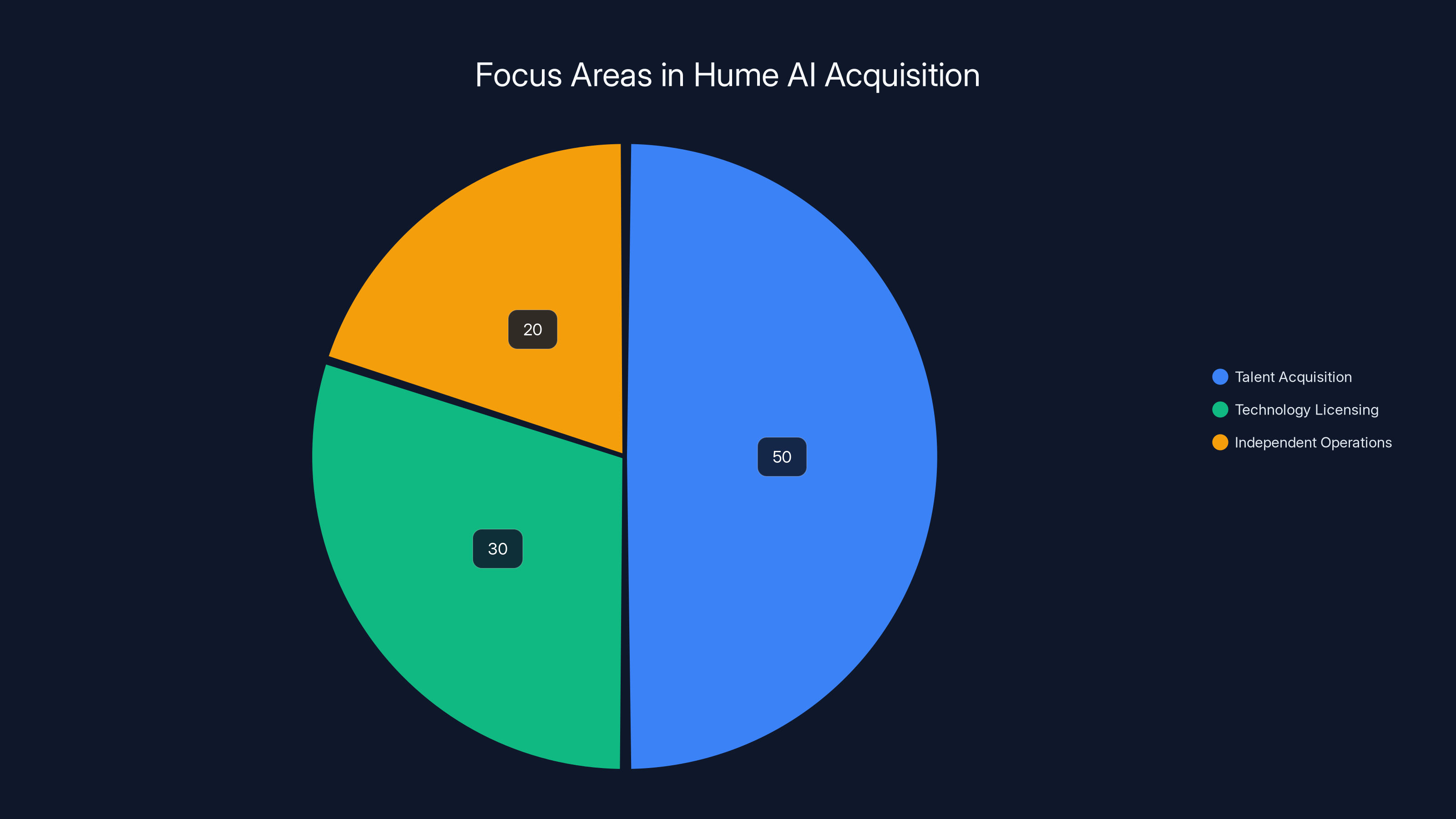

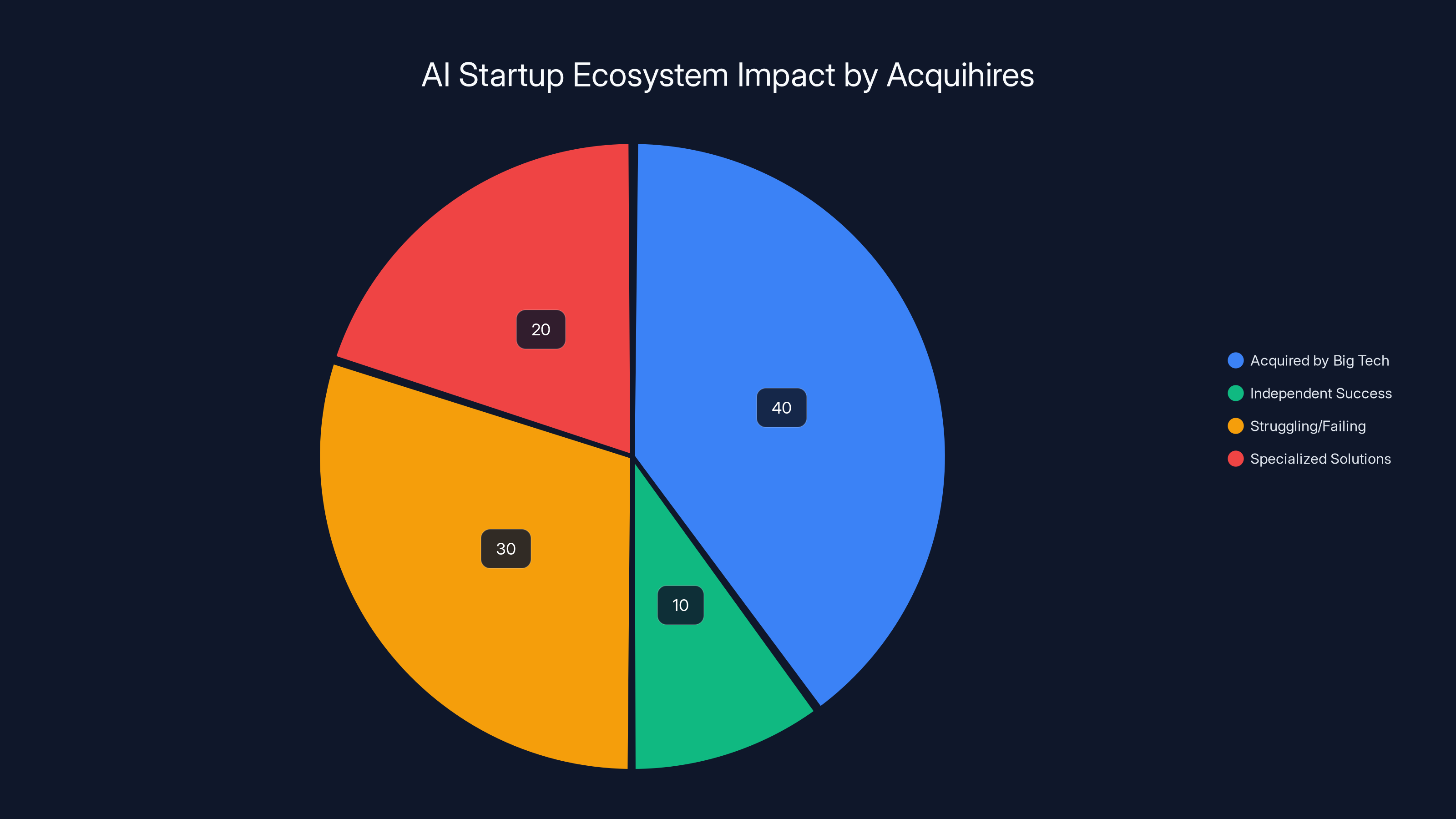

Acquihires focus on talent acquisition with less concern for legacy systems and regulatory scrutiny, while traditional acquisitions involve full business integration. Estimated data.

The Broader Pattern: Big Tech Vacuums Up AI Talent

How Acquihires Became Standard Practice

This isn't the first time we've seen this pattern. Google hired the CEO and top researchers from Windsurf, the AI coding startup that went viral in 2024. OpenAI has executed multiple talent acquisitions in recent months, including teams from Covogo and Roi. The strategy has become normalized across the industry.

What's happening is relatively straightforward: startup founders and early engineers build novel capabilities. They prove the concept works. But scaling to billions of users, integrating with existing products, and capturing regulatory approval requires resources startups can't match. Rather than wait for these teams to either succeed (unlikely) or fail (more likely), big tech companies preempt that timeline by acquiring the people.

For the startup founders, it's pragmatic. You built something valuable. You've raised capital. But odds of competing against Google, OpenAI, or Meta are approximately zero. Taking the offer, getting your team well-compensated, and having your ideas incorporated into products billions of people use? That's a reasonable outcome.

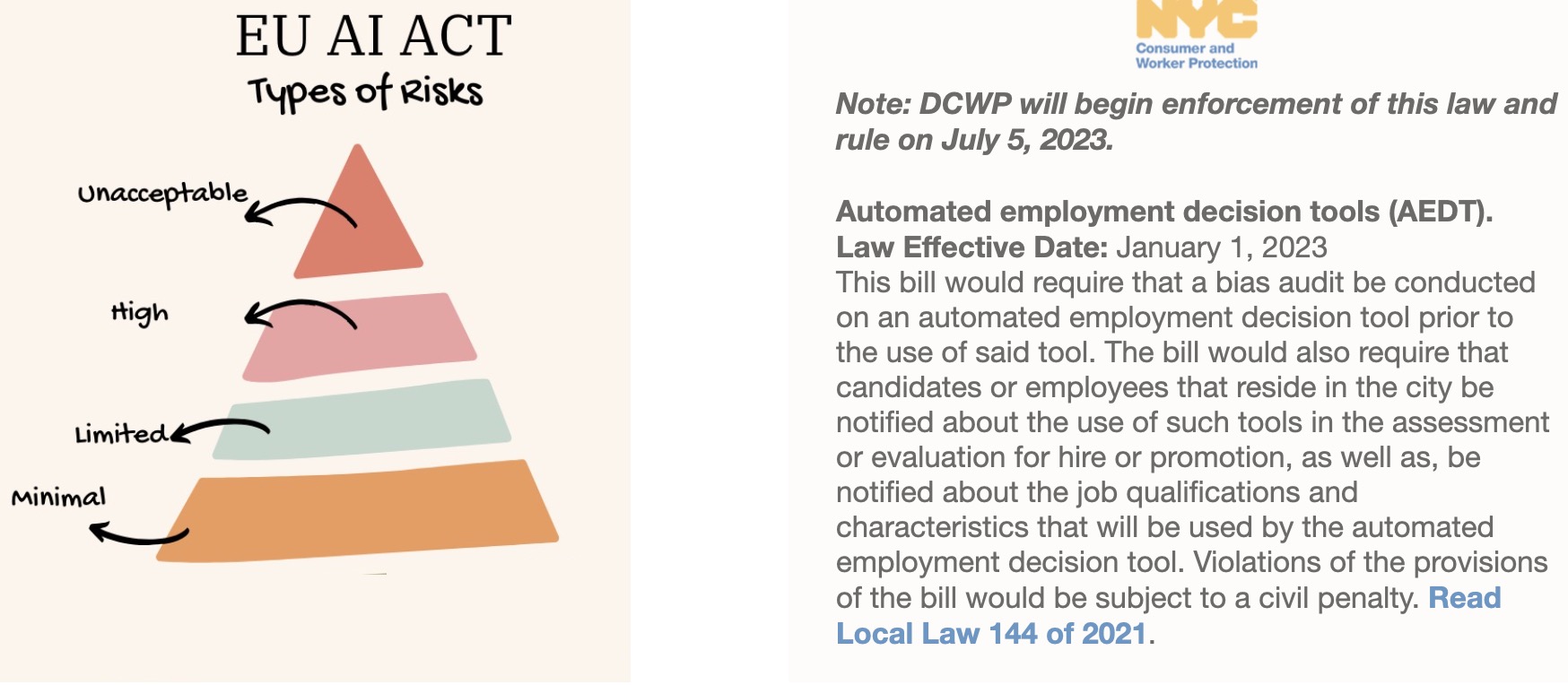

The Regulatory Backdrop

The FTC has been explicit about its concerns. These deals often escape scrutiny because technically, you're not acquiring a company. You're hiring people. That distinction feels important legally but is almost meaningless functionally. If you acquire a startup's entire technical team, you've effectively shut down the competition and absorbed its capabilities.

There's legitimate concern here. Big tech companies have cash to outbid anyone. They can offer equity in companies worth billions, salary premiums, stock options, and opportunities that no startup can match. If every promising AI startup gets vacuumed into Google, OpenAI, or Meta, venture capital dries up, the startup ecosystem stalls, and innovation concentrates among three companies.

But we're not there yet. The FTC said it would take a closer look, not that these deals are illegal. The timeline for regulatory action is usually measured in years, not months.

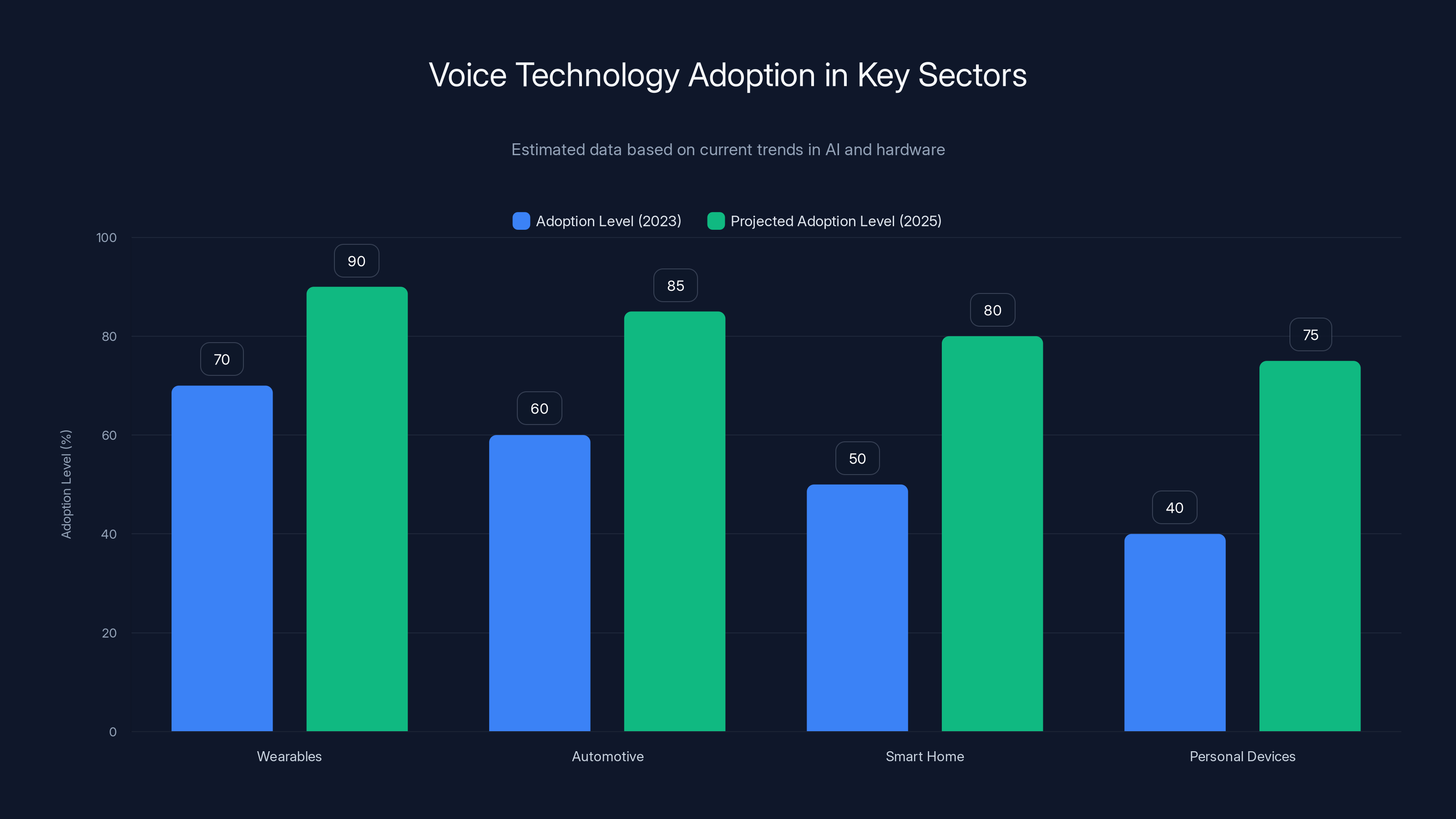

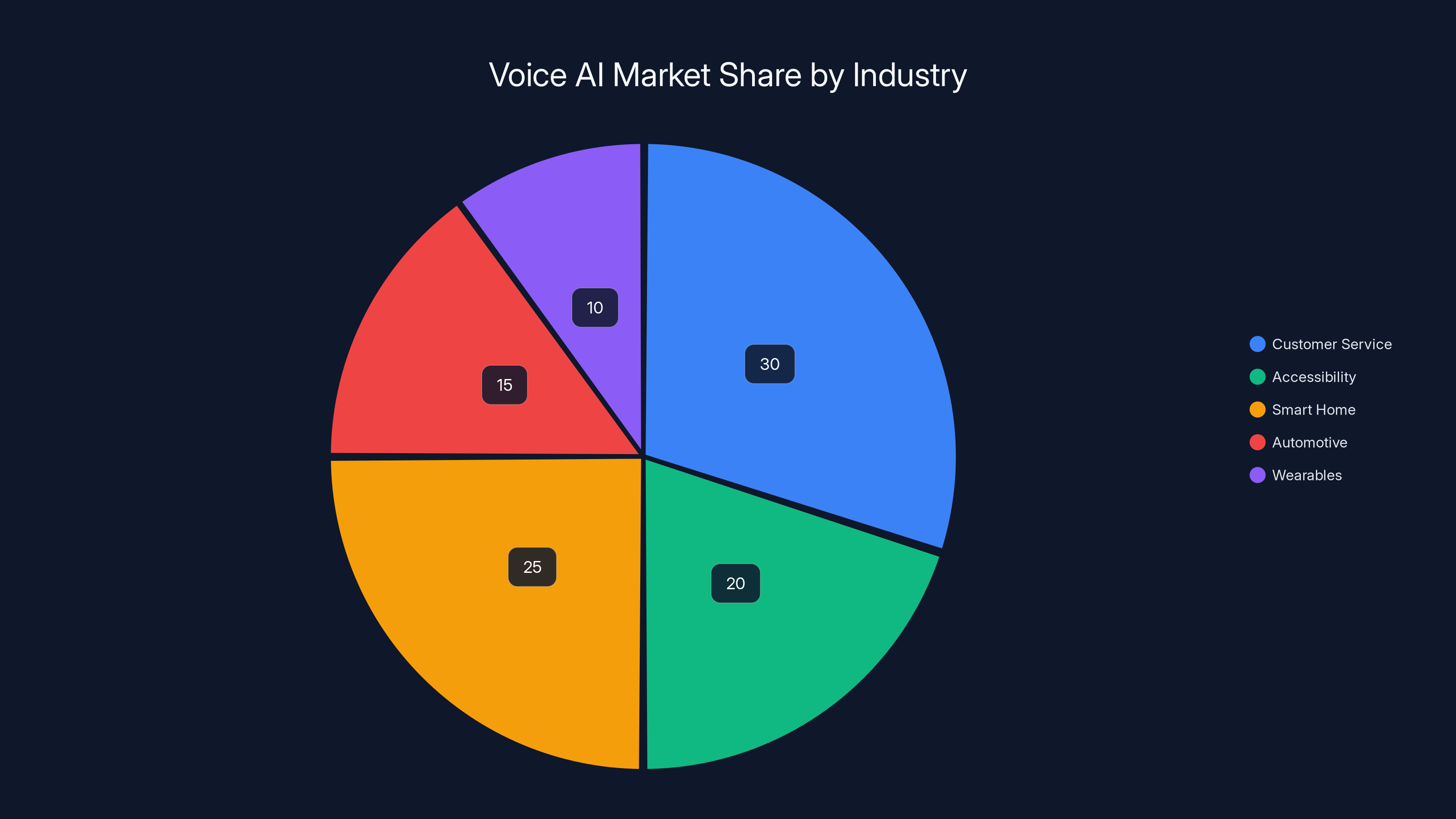

Voice technology is rapidly being adopted across various sectors, with wearables and automotive leading the charge. By 2025, adoption levels are expected to significantly increase as voice becomes the primary input mode. (Estimated data)

Why Voice Is the Next Battleground

The Shift Away From Screens

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: most people don't actually want to type to AI. They want to talk to it.

Screens are useful for scrolling, reading, and careful work. But for quick questions, context-switching, or situations where your hands are occupied, voice beats text every time. You can talk while driving. While cooking. While your hands are covered in paint. While you're walking.

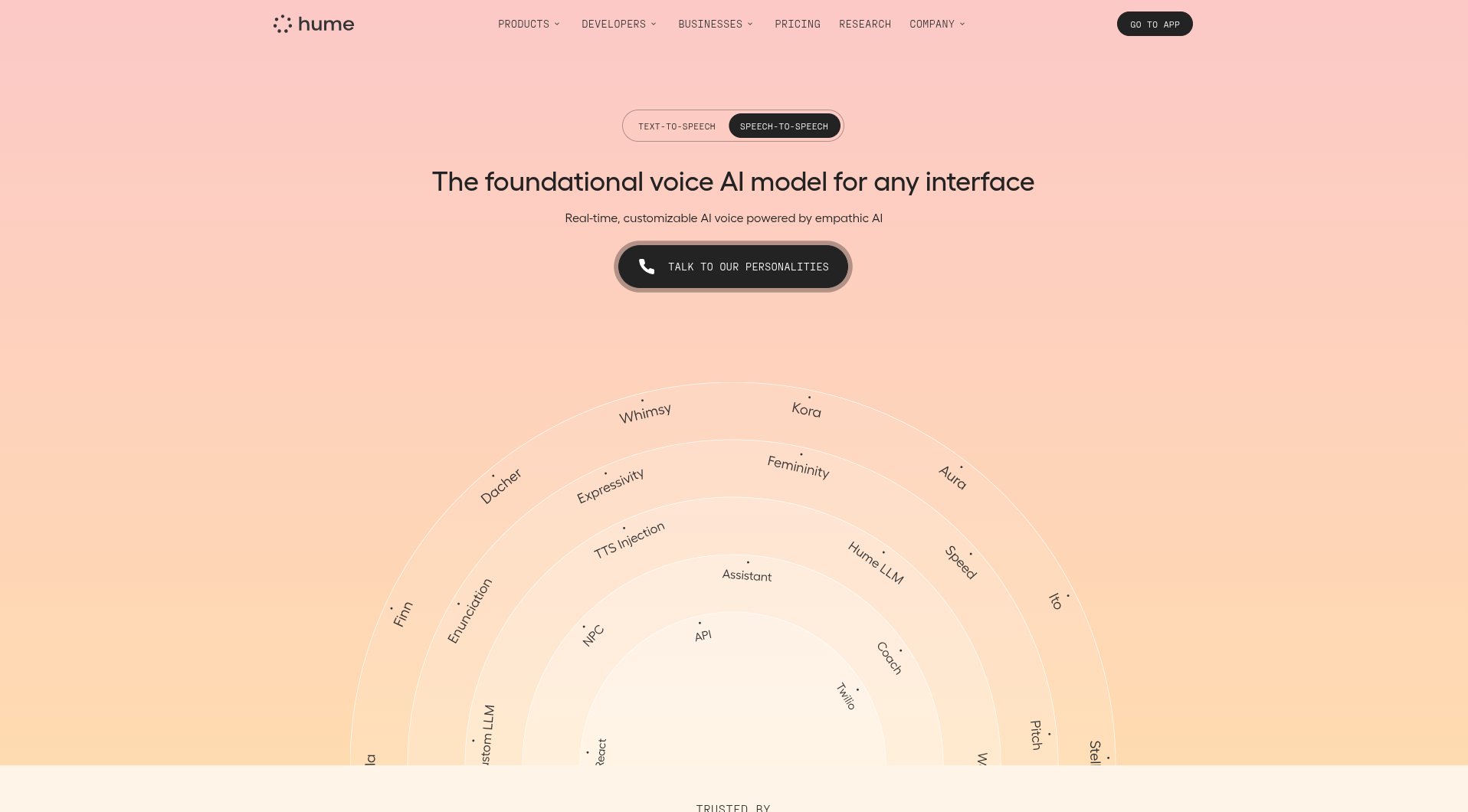

This observation drives everything happening right now. Every major AI company is pouring resources into voice capabilities because they understand something fundamental: voice is the only acceptable input for wearables, automotive, smart home, and countless other form factors.

Vanessa Larco, an investor who watches these trends closely, put it bluntly: "Voice is the only acceptable input mode for wearables. This acquisition will only accelerate the need for voice apps." That's not hype. That's recognizing the obvious consequence of where the hardware is going.

The Hardware Push Is Real

Meta is betting big on this. The company acquired Play AI last year and is pouring resources into making its Ray-Ban smart glasses audio-first. The glasses handle voice-controlled calls, texts, music, and photo sharing. Most importantly, they use audio to help users hear conversations in noisy environments.

OpenAI is reportedly preparing a complete overhaul of its audio models to support a new audio-first personal device, a collaboration with designer Jonny Ive's startup io. Leaks suggest it could be earbuds or some wearable form factor. The device is expected to launch in 2025.

Google itself has been steadily improving Gemini Live, which allows conversational interactions with the chatbot. The company released a new native audio model for its Live API that specifically improved handling of complex workflows. That's not a minor feature update. It's fundamental infrastructure work on audio understanding.

Eleven Labs, the AI voice generation startup, just announced it crossed $330 million in annual recurring revenue. That's a company that exists purely to make voices sound natural and convincing. The revenue growth reflects real demand from companies building voice products.

Everywhere you look, the hardware and AI infrastructure is shifting toward voice-first design.

The Emotional Intelligence Angle

What Makes Hume AI Different

Most voice AI systems do speech-to-text conversion and then process the text. They don't truly listen to the voice itself. Hume AI's differentiator was that it tried to reverse-engineer human emotion from acoustic features.

Your voice carries tremendous information beyond words. Pitch changes. Speaking rate. Emphasis patterns. Vocal fry. Breathiness. Hesitation. All of these communicate emotional state. Humans pick up on this automatically. We know when someone is frustrated, angry, confused, or lying largely through vocal cues. Most AI systems ignore all of this information.

Hume AI built models that don't ignore it. The Empathetic Voice Interface wasn't just a conversational AI. It was conversational AI that understood when you were upset and could adjust its response accordingly. It could detect when you were confused and ask clarifying questions. It could pick up on frustration and offer alternatives.

This capability matters tremendously for voice interfaces. A voice assistant that can't detect emotion is fundamentally limited. It responds the same way regardless of whether you're asking a casual question or in genuine distress. That's not natural conversation.

Why Google Needed This Capability

Google's Gemini is a powerful language model. But language models don't understand emotional context unless you explicitly tell them. "I'm frustrated" versus "I'm fine" might produce different text-based responses, but Gemini won't know which one is true unless you type it.

With vocal analysis, Gemini could know. Not from reading your words but from hearing how you said them. That's a different category of capability.

For a company like Google building voice interfaces at scale, this is crucial. If millions of people are interacting with Gemini through voice, and those interactions are becoming increasingly important for customer support, health assistance, and other high-stakes use cases, then understanding emotional context becomes a safety and usability requirement.

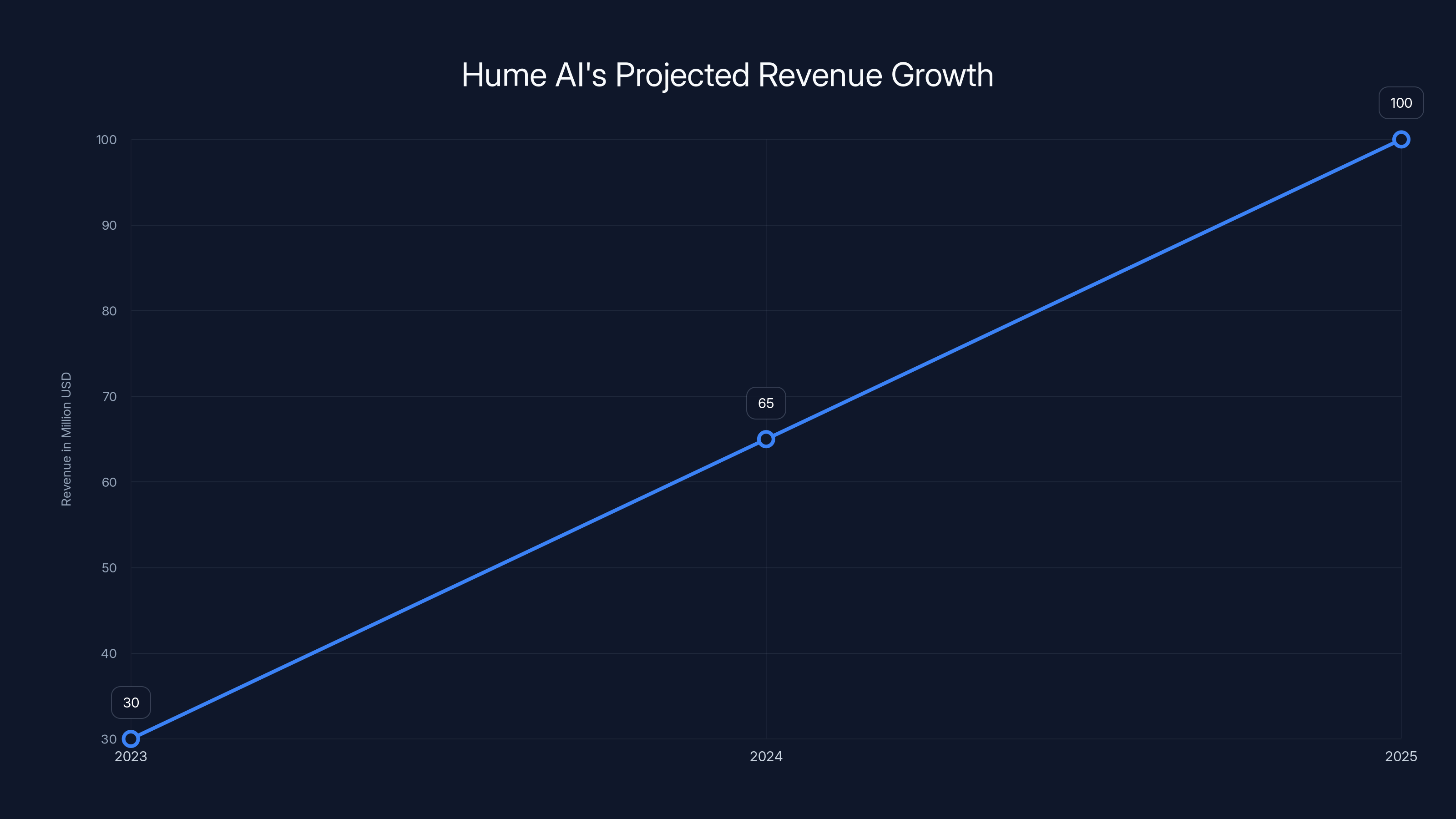

Google presumably paid attention to Hume's revenue trajectory. The startup expected to hit $100 million in revenue this year. That's not a small number for a two-year-old company. Someone was willing to pay for these capabilities. Google realized it should own them.

Estimated data shows Customer Service and Smart Home industries as leading sectors for Voice AI adoption, with Customer Service holding the largest share.

The Competitive Voice AI Landscape

Who Else Is Building Voice

Hume AI wasn't alone in focusing on voice. The entire AI industry is mobilizing around audio capabilities, but different companies are taking different approaches.

OpenAI has been steadily improving its audio API and investing in voice capabilities. The company has real-time audio processing, voice cloning, and translation features. The rumored new personal device suggests OpenAI sees voice as core to its future product strategy.

Meta's Ray-Ban glasses represent a different angle. Rather than starting with a chatbot and adding voice, Meta is building from the hardware backward. The glasses literally have speakers and microphones built in. Every interaction is voice-first by design. The AI models powering them need to work within those constraints.

Anthropic, through its Claude model, has been incrementally improving voice features. Apple is investing heavily in voice quality for Siri. Even traditional voice assistant companies like Amazon (Alexa) are trying to modernize their offerings with large language model capabilities.

What's different about the current moment is that most of these players are no longer treating voice as a separate feature area. It's becoming central to product strategy. That shift happened maybe six months ago. Before that, voice was an accessibility feature or a convenience option. Now it's the primary interface for new form factors.

The Consolidation Dynamic

The talent acquisition trend creates a consolidation dynamic. Early startups build novel approaches to voice. Big tech companies watch. Once the approach proves valuable, acquisition time. The founder gets a payout. The team gets security. The technology gets absorbed into a product at scale.

This pattern repeats across AI. Startups often move faster than incumbents on specific problems. But incumbents can scale solutions to millions of users and integrate them across ecosystems. The acquihire is the handoff point.

For founders, understanding this dynamic is important. If you're building voice AI and it's working, you have a window before a big tech company notices. That window might be 18 months to three years, depending on the application. Getting in front of acquirers before they decide they need to acquire is smart strategy.

The Revenue and Funding Picture

Hume AI's Business Metrics

Hume AI raised close to

For context, most AI startups that raise

Largely, this reflects the urgency around voice AI. Companies building products that depend on voice capabilities need reliable infrastructure. Hume AI provided that infrastructure. Customers were paying for access to the models and APIs.

The licensing arrangement that continued after the leadership team was acquired suggests this revenue stream remains valuable. Hume AI is staying in business, supplying its technology to other AI firms. Google isn't using this as a complete shutdown play. It's acquiring the expertise while letting the business line continue.

Why These Numbers Matter

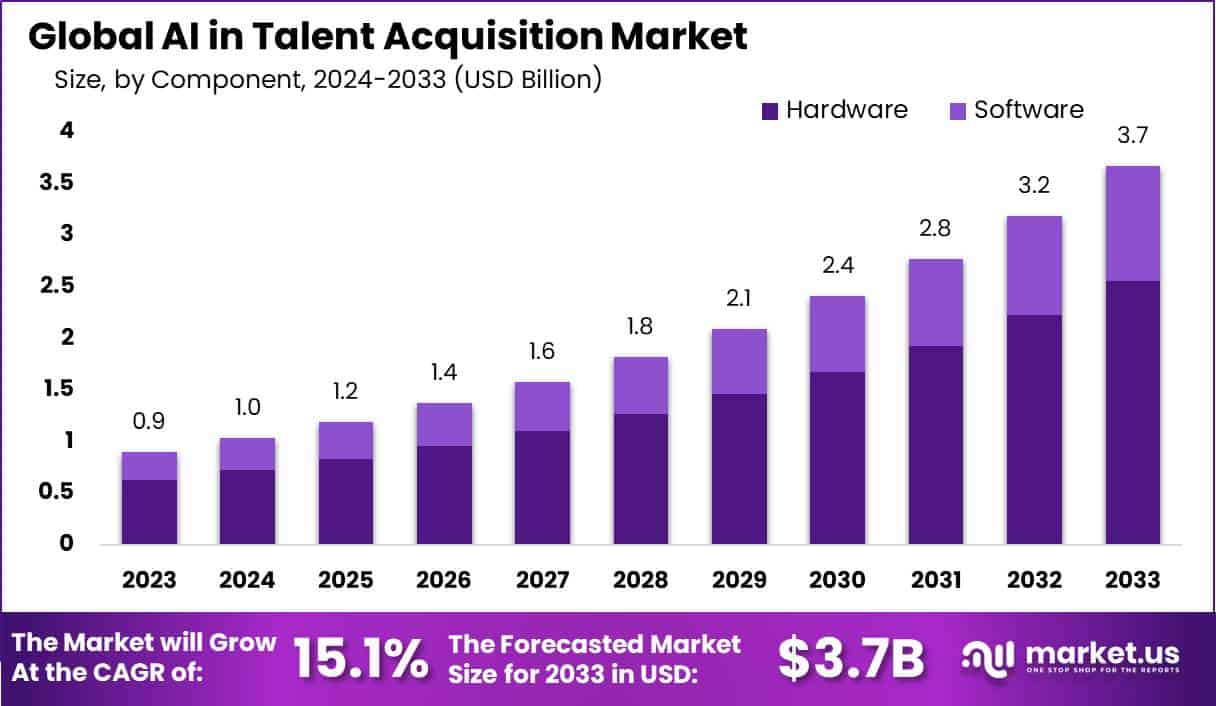

The financial trajectory indicates we're not in early experimentation mode for voice AI anymore. We're in the scaling phase. Customers are building products on top of voice AI infrastructure. They're paying enough to create a $100 million revenue business in a startup.

That's the inflection point you watch for in any technology domain. When startups start hitting nine-figure revenue, the incumbents realize the category is real. At that moment, acquisition becomes strategically important.

The acquisition primarily focused on talent acquisition (50%), followed by technology licensing (30%), and maintaining independent operations (20%). Estimated data.

The Regulatory Scrutiny Problem

Why the FTC Is Watching

Acquihires are gaining attention from regulators because they appear to accomplish the same thing as traditional acquisitions without the regulatory review. If you buy a company, regulators might examine whether the deal reduces competition. If you hire the team, the same competition reduction occurs, but it happens under the radar.

The FTC's recent signal that it would "take a closer look" at these deals suggests enforcement is coming. But probably slowly. Regulatory action takes years. By the time rules clarify, multiple acquihires will have already happened.

The question regulators need to answer: does acquiring a startup's team count as an acquisition subject to Hart-Scott-Rodino review? Currently, the answer is mostly no. Hiring people isn't acquiring a company. But the functional effect is identical. The startup's technology capability gets absorbed. The competition disappears.

What Changes If Regulators Act

If the FTC decides to crack down, acquihires become harder. Big tech companies would need to either do formal M&A (with regulatory review) or pass on the talent. They'd probably do formal M&A. They'd also probably slow down.

But we're not there yet. The current window remains open. Companies like Google can still execute these deals.

The Timeline of Voice AI Development

Recent Milestones

The voice AI push has accelerated tremendously in just the last year.

In 2024, major investments happened. Meta acquired Play AI. Google launched Gemini Live and improved its audio API. OpenAI worked on real-time audio capabilities. Eleven Labs grew to massive scale. A dozen startups launched trying to build the "next thing" in voice.

In 2025, we're seeing the hardware play become real. Devices are launching. Companies are deploying voice-first interfaces. The infrastructure is moving from experimental to production.

The Hume AI acquisition is a midpoint in this evolution. The company proved voice AI could be commercially valuable. Big tech moved to acquire the capability. Within 18 months, we'll probably see these capabilities fully integrated into Google's products and available to billions of users.

What Comes Next

The logical next step is expanding beyond English. Voice AI trained on one language is interesting. Voice AI that works across multiple languages, dialects, and accents is transformative. That's where Hume AI's continued work, under the licensing arrangement, probably focuses.

After that comes personalization. Today's voice AI mostly treats every user identically. Tomorrow's version will adapt to individual voices, preferences, and communication styles. The emotional intelligence Hume AI built is relevant here too. A voice assistant that remembers you were upset last time and adjusts its tone accordingly is genuinely better than one that doesn't.

Finally, there's integration across devices. Right now, voice AI mostly exists in isolation. You talk to your phone. You talk to your earbuds. You talk to your car. But ideally, the same assistant understands context across all those devices and your interactions with each.

Acquihires lead to 40% of AI startups being acquired by big tech, while only 10% succeed independently. Estimated data.

Implications for Product Strategy

How This Changes Product Development

For teams building AI products, the Hume AI acquisition signals something important: voice isn't optional anymore. It's baseline. Any new AI product launching without voice capabilities in 2025 is accepting a significant limitation.

Moreover, it's not enough to have voice capability. The quality matters tremendously. Users notice latency. They notice when the AI doesn't understand their accent. They notice emotional tone.

This means product teams need to invest in voice quality seriously. That investment requires hiring people who understand audio, acoustic analysis, and voice UI design. It's not a small sidebar project. It's core infrastructure.

Companies building voice products should also expect the big tech firms to acquire competitive talent aggressively. If you hire excellent voice researchers, Google, OpenAI, or Meta might try to acquire them. Retention becomes harder.

What This Means for Startup Founding

The acquihire dynamic creates both opportunity and risk for startup founders.

Opportunity: if you build something genuinely novel in voice AI and it gets traction, big tech companies will notice and acquire you. The time to liquidity is shorter than traditional startups.

Risk: you're competing against companies with unlimited resources and existing large user bases. Unless you build something truly differentiated, you'll always be a feature acquisition, not a standalone company.

The smart approach for founders is probably to pick a very specific angle within voice AI and go deep. Don't try to build a general-purpose voice assistant. Build something for a specific use case: healthcare, customer service, accessibility, education. Get traction in that vertical. Then you're valuable either as an acquisition or as a standalone business.

The Broader AI Consolidation Trend

Why Acquihires Are Accelerating

The acquihire trend reflects a fundamental dynamic in AI development right now. The technology is moving so fast that building from scratch in-house is often slower than acquiring teams that already figured things out.

Traditional product development at Google involves lengthy approval processes, stakeholder alignment, and integration with existing systems. That might take 18 months. Acquiring a team that already built working technology might take three months. The speed advantage is enormous.

There's also a competition dynamic. If OpenAI acquires a talented voice team, Google needs to respond. The companies are in an arms race for talent and capability. Acquihires are how you move fast in that context.

The precedent is strong. Google has done this multiple times. OpenAI has normalized it. Meta is doing it. Anthropic has started. Every major AI company has either acquired teams or is considering it.

The Startup Ecosystem Impact

Large-scale acquihires do have a real impact on the startup ecosystem. They signal to investors that building independent AI companies might not be viable long-term. Why invest in a voice AI startup if Google will just hire the team in two years?

That uncertainty makes fundraising harder. VCs become more cautious about funding startups in areas where big tech has obvious interest.

On the flip side, the ability to get acquired by a top company creates a defined path to success. Founders know they can build something, prove it works, and get acquired. That's better odds than the traditional startup path where only 1% of companies succeed independently.

The net effect is probably a reduction in the number of AI startups trying to compete with incumbents. But an increase in AI startups building specialized solutions for specific domains.

Hume AI is projected to grow its annual revenue from

Voice Interfaces vs. Text Interfaces: The Ergonomic Shift

Why Voice Wins for Certain Use Cases

There's an ergonomic and cognitive argument for why voice is winning that goes beyond just convenience.

Text-based interaction requires that you stop what you're doing, formulate a complete question in writing, and type it out. That's a high-friction process. Voice is lower friction. You're already talking. You just talk to the AI instead of a person.

For accessibility, the advantage is enormous. People with mobility limitations, vision loss, or dexterity issues find voice dramatically easier than typing. That's true regardless of how good voice technology gets.

But even for able-bodied users, voice is often better. In a noisy Slack conversation, you might not want to type. While driving, you definitely shouldn't. While standing at a smart home device, voice makes sense.

The categories where voice doesn't win are places where precision matters. You probably want to type a sensitive email rather than dictate it. You might want to use a mouse for graphic design. Reading long documents is easier on a screen than through audio.

So voice doesn't replace text. They coexist. Voice handles quick interactions. Text handles detailed work. The shift happening now is that voice is taking a larger share of quick interactions.

The UX Design Challenge

Building voice interfaces that feel natural is harder than it seems. Text interfaces can be somewhat awkward and still work fine. Voice interfaces that are awkward feel broken.

Users expect voice AI to understand context, handle interruptions, recognize when they're confused, and respond appropriately. That's a high bar. Most voice AI falls short.

This is where Hume AI's emotional intelligence comes in. If the AI understands you're frustrated, it can slow down, repeat itself, or suggest alternatives. That responsiveness makes the interaction feel natural rather than robotic.

Designing voice UX requires deep understanding of conversation. How do real people talk? What are the common patterns? What breaks the flow? These aren't questions you can answer with A/B testing text interfaces. You need researchers who study conversation itself.

Google acquiring Hume AI's team makes sense partly because those people understand this deeply. They've thought about how to design voice conversations at scale.

The Economics of Voice AI Services

Revenue Models in Voice AI

Hume AI's path to $100 million in revenue probably involved selling API access and licensing models. Companies building voice products can license Hume AI's capabilities rather than building in-house.

That's a sustainable business model. Infrastructure companies like Stripe, Twilio, and earlier, AWS, built massive businesses by letting other companies rent their capabilities. Voice AI infrastructure could follow the same pattern.

The licensing approach makes sense for companies that need voice capabilities but don't have the expertise to build them internally. A customer service company doesn't want to hire acoustic researchers. They want to license a voice solution that works.

Once Google acquires the team, that revenue model potentially changes. Google might roll the capability into Gemini and offer it as part of the larger AI suite. Or Google might keep the licensing business alive for customers who prefer point solutions.

Pricing and Market Sizing

Currently, voice API pricing is all over the map. Some providers charge per minute of audio processed. Others charge per request. Some offer volume discounts.

As voice AI becomes more commoditized, pricing will probably converge toward cost-of-goods-sold plus modest margin. That's the pattern we see in cloud computing. You'll eventually pay roughly what it costs to run the inference, plus a small fee for the service.

The market size for voice AI is large. Every company that operates customer service, accessibility, smart home, automotive, or wearable products could be a customer. That's basically every major tech company, plus countless smaller companies.

Estimating TAM (total addressable market) is hard, but probably in the tens of billions annually. That's enough to support multiple independent companies. But Google acquiring the team suggests it wants to own the capability rather than rely on a vendor.

Case Studies: Voice AI in Production

Healthcare Applications

One of the most compelling voice AI use cases is healthcare. Doctors dictate notes constantly. Rather than typing, they speak. The AI transcribes, understands context, and generates structured notes.

Emotional intelligence is valuable here. A patient might say they're fine but sound distressed. The AI could flag that discrepancy for the doctor. A patient might be confused about instructions. The AI could detect that and adapt its explanation.

Companies like Nabla and Cleartax are building in this space. They're not household names, but they're solving real problems for healthcare providers.

Customer Service

Another major use case is customer service. Customers calling a company speak to a voice AI first. The AI handles simple questions. Complex issues get escalated to humans.

The quality of that first interaction determines whether customers get frustrated. Voice AI that understands frustration can de-escalate. Voice AI that sounds natural is less irritating than obviously robotic systems.

Companies like Five 9 and Zendesk are incorporating voice AI into their platforms. But the specialists who understand voice quality deeply are still scattered. Google acquiring Hume AI's team consolidates expertise.

Accessibility Products

Voice-first products can be revolutionary for accessibility. Blind users can use voice input and audio output to interact with computers at full capability. That wasn't always possible.

Eleven Labs' success partly reflects companies building accessibility-focused products that need natural-sounding voice.

The Future of Voice AI: 2025-2027 Predictions

Likely Developments

Within the next 18 months, expect to see:

Major AI companies integrating voice capabilities into their core products. Google's move is a signal that voice is becoming baseline, not optional.

Wearable devices becoming increasingly voice-first. Smartwatches, earbuds, and glasses will rely on voice input by default because screens are small and typing is awkward.

Price competition in voice AI. As the capability becomes more commoditized, pricing per request or per minute will drop. That's good for companies buying voice services, bad for startups trying to build sustainable voice AI businesses.

Improvement in voice AI quality. The current generation understands English reasonably well. Next generation will handle accents better, understand context better, and feel more natural. That improvement requires the kind of expertise Hume AI developed.

Uncertain Developments

Will voice AI become good enough to replace human customer service agents for complex problems? Probably eventually, but it's not there yet.

Will voice AI work across languages equally well? Unlikely in the next two years. English is the easiest to train on because there's so much training data. Other languages will lag.

Will voice input eventually surpass text for professional knowledge work? Probably not. Typing will remain dominant for writing, coding, and detailed work. Voice will handle quick interactions and accessibility.

Strategic Implications for Different Players

What This Means for Google

Google is making a clear bet: voice is the future interface. By acquiring Hume AI's team, the company is signaling it wants to own voice quality rather than rely on vendors. It's also preempting competitors from acquiring the team.

The move also gives Google leverage in the broader AI assistant market. If Gemini has dramatically better voice capabilities than ChatGPT, that's a real product differentiation.

What This Means for OpenAI

OpenAI probably didn't acquire Hume AI's team because Hume doesn't fit OpenAI's model. OpenAI is building a general-purpose AI company. Hume is specialized in voice. But OpenAI is investing heavily in voice capabilities for its planned personal device. If that device is successful, OpenAI might regret not having world-class voice AI expertise in-house.

OpenAI will probably respond by building voice capabilities internally or acquiring other teams with voice expertise.

What This Means for Meta

Meta is already committed to voice through Ray-Ban glasses. Meta's approach is hardware-first, then software. That's different from Google's approach, which is software-first, then hardware.

Meta will probably continue building voice capabilities in-house through its investment in audio and AI research.

What This Means for Startups

For voice AI startups, the Hume AI acquisition is a mixed signal. On one hand, it shows the category is valuable. On the other hand, it shows big tech can acquire your team if you succeed.

Startups in this space need to either move very fast to become independent businesses, or pick niches where they're not competing with Google/OpenAI/Meta directly. Healthcare, customer service for specific verticals, accessibility. Areas where specialization is an advantage.

Comparison: Different Approaches to Voice AI

The Technology Approaches

Different companies are taking fundamentally different approaches to voice AI.

Some (like Google with its acquisition) are focused on emotional intelligence and natural conversation. The idea is that voice AI should understand context and emotion.

Others (like OpenAI) are focused on raw capability. Can the model understand what you're saying and respond usefully? Emotion is secondary.

Still others (like Meta) are focused on efficiency and latency. Voice features need to work on devices with limited compute. Responses need to come back quickly.

None of these approaches is wrong. They're different bets on what matters most. Google's bet, evidenced by acquiring Hume, is that emotional intelligence matters. That's a specific vision of what voice AI should be.

The Business Model Differences

Business models also vary.

Some companies (like Eleven Labs) are building point solutions and charging per API call. That's a software-as-a-service model.

Others (like Google) are building comprehensive products where voice is one feature among many. They're not charging for voice separately; it's part of Gemini.

Still others are building hardware first (Meta with Ray-Ban glasses) and voice is baked into the experience.

These different models create different incentives for innovation.

The Talent Acquisition War

How Big Tech Is Winning for Talent

Google, OpenAI, and other top companies have massive advantages in recruiting talent:

Money. They can offer salaries that startups can't match. Add in equity in billion-dollar companies, and the compensation gap is enormous.

Scale. Your work at Google affects billions of people. That's motivating for many people.

Resources. You get access to massive compute, datasets, and infrastructure. Your research can move faster.

Brand. Working at Google looks good on resumes. It opens doors for future opportunities.

For AI researchers, these advantages are almost impossible for startups to overcome. The best researchers in the world work at big tech companies partly because that's where they can do their best work.

Acquihires are how big tech leverages this advantage. They wait for startups to do risky research, then acquire the teams once it works.

The Downstream Impact

This creates a dynamic where very few AI startups become independent companies. Most eventually get acquired. That might actually be fine, but it does concentrate power.

Smaller companies can't compete with Google's resources. So they either get acquired or focus on niches where concentration isn't possible.

Conclusion: Why Voice Matters

The Hume AI acquisition is part of a larger story about how humans will interact with AI in the future. Voice isn't a feature anymore. It's becoming the primary interface for many use cases.

Understanding why this shift is happening requires understanding both technology and human behavior. Voice is more accessible than typing. It's more convenient in many situations. It's the natural way humans communicate.

AI companies that understand voice deeply have an advantage. Companies that treat voice as an afterthought will lag.

Google's acquisition of Hume AI's team signals the company is taking this seriously. Big tech doesn't usually hire startup teams unless it really matters. The fact that multiple major companies are doing this with voice AI talent suggests we're at a genuine inflection point.

In 18 months, the average AI assistant you interact with will handle voice significantly better than today. You'll probably use voice more than you do now. The awkwardness of current voice AI will fade as capabilities improve.

The companies that own that capability—Google, OpenAI, Meta, and others—will have a real advantage. The startups that pioneered the capability? Some will be acquired. Some will become vendor relationships. Very few will remain independent.

That's not necessarily bad. It's just how technology development works. Startups take risk. Big companies scale risk that works. Sometimes the startup becomes a company. Usually, it becomes a feature in someone else's product.

The broader lesson: watch where big tech is hiring talent. That's where the next inflection point is happening. Voice is one example. There will be others.

FAQ

What is an acquihire and how does it differ from a traditional acquisition?

An acquihire is when a company hires the key employees from another company while letting the acquired company's business continue or shut down separately. This differs from traditional M&A where the entire company is purchased, integrated, and absorbed. Acquihires are strategically useful because they bring specialized talent into the organization, avoid inheriting unwanted legacy systems or contracts, and can sometimes sidestep regulatory scrutiny by appearing as hiring rather than a merger.

Why is voice AI becoming more important than text-based AI interfaces?

Voice interfaces are more convenient for situations where hands are occupied (driving, cooking), less intrusive in social settings than typing, more accessible for people with disabilities, and feel more natural for quick interactions. Voice also has emotional information embedded in tone, pace, and pitch that text lacks, allowing voice-first AI systems to understand context better. As wearables, automotive, and smart home devices become more prevalent, voice becomes the practical interface choice because screens are either unavailable or awkwardly small.

What makes Hume AI's technology different from other voice AI companies?

Hume AI's distinctive capability is understanding human emotion and mood from voice characteristics rather than just transcribing speech. The company built what it calls an "Empathetic Voice Interface" that analyzes vocal tone, speaking rate, emphasis patterns, and other acoustic features to infer emotional state. This emotional intelligence allows the AI to adjust responses based on whether a user is frustrated, confused, or satisfied, making interactions feel more natural and responsive than systems that ignore emotional context entirely.

How does regulatory scrutiny affect talent acquisition deals in AI?

The FTC has indicated it will examine acquihires more closely because they can accomplish the same competitive effect as traditional acquisitions without triggering merger review. When a company acquires another startup's entire technical team, it absorbs the startup's capabilities and eliminates the competition, yet technically it's hiring people rather than buying a company. Increased regulatory attention could eventually require these deals to go through formal acquisition review, making them slower and more difficult to execute.

What are the business implications of voice AI for companies building customer-facing products?

Companies building customer service products, healthcare applications, accessibility tools, smart devices, or wearables increasingly need high-quality voice capabilities as baseline features rather than optional add-ons. Customers expect voice interfaces to be responsive, natural-sounding, and contextually aware. Building voice quality requires hiring researchers and engineers with specialized expertise in acoustic analysis and voice UI design, or licensing these capabilities from infrastructure companies that have built this expertise at scale.

What happens to Hume AI after Google acquired its leadership team?

Under the licensing agreement that accompanied the personnel acquisition, Hume AI continues operating as an independent company and continues supplying its technology to other AI firms. This arrangement allows Google to access Hume's technology and talent while allowing Hume to maintain its revenue streams from customers who prefer point solutions rather than integrated platforms. The company's business model shifts from independent venture to vendor relationship with both Google and other customers.

Why are big tech companies like Google pursuing voice AI as a priority now?

Voice is becoming the primary interface for new hardware form factors including wearables, automotive systems, and smart home devices. These devices have small or nonexistent screens, making voice the practical input method. Additionally, voice interactions with AI are becoming normalized through consumer products like smart speakers and mobile assistants. Companies that own voice quality have a genuine product advantage, making the capability strategically important rather than optional. This inflection point is why multiple major tech companies are simultaneously investing heavily in voice AI capabilities.

What does the Hume AI acquisition signal about the future of AI startups?

The acquisition pattern shows that promising AI startups often face acquisition rather than remaining independent. Big tech companies with more resources can outbid competitors for talent and scale solutions faster than startups can. The path forward for AI startups increasingly involves either being acquired for talent or team, building in niches where specialization is durable, or moving extremely fast to become independent companies before acquisition becomes inevitable. This dynamic is shifting incentives in venture capital toward supporting specialized startups with defensible positions rather than general-purpose AI platforms.

How does voice-first device design change what voice AI needs to be?

When voice is the primary input (as in earbuds, Ray-Ban glasses, or automotive systems), the voice AI system needs different characteristics than voice as an auxiliary feature. Response latency becomes critical because users expect immediate feedback. Naturalness of the voice output matters because users hear it constantly. Context awareness becomes essential because you can't look at a screen to disambiguate what the AI understood. Emotional intelligence matters because voice is the only channel for conveying intent and state. These requirements push voice AI development in different directions than traditional chatbots with voice add-ons.

What are the revenue implications of the shift toward voice-dominant interfaces?

Companies providing voice AI infrastructure can build sustainable revenue by licensing APIs and models to other companies that need voice capabilities. This pattern parallels infrastructure companies like Stripe (payments) and Twilio (communications) that became billion-dollar businesses by letting other companies rent specialized capabilities. As voice AI becomes more commoditized, pricing will likely converge toward cost-of-computation plus modest margins. The market size is substantial because virtually every company in healthcare, customer service, automotive, smart home, and wearables could be a customer for high-quality voice AI infrastructure.

What should product teams prioritize when adding voice capabilities to their products?

Prioritize latency first because voice interactions that feel slow break the user experience. Invest in voice quality because users notice artificial-sounding voices immediately. Test with diverse accents and speech patterns because voice AI trained primarily on standard American English often fails for other dialects. Consider emotional intelligence and context awareness because voice is a limited bandwidth channel and the AI needs to catch nuances that text interfaces miss. Finally, plan for accessibility because voice-first interfaces are valuable for users with disabilities, and accessibility often drives innovation that benefits everyone.

Key Takeaways

- Google acquired Hume AI's CEO and team through a licensing agreement, signaling voice capabilities are now core competitive advantage, not optional features

- Acquihires let big tech acquire specialized talent while sidestepping full regulatory scrutiny, though the FTC is beginning to scrutinize these deals more carefully

- Voice is becoming the primary interface for wearables, automotive, smart home, and accessibility applications because it's more natural than typing or small screens

- Hume AI's distinctive capability was understanding emotions from vocal characteristics, enabling conversational AI to detect frustration or confusion and adjust responses

- The voice AI market is consolidating around major players as startups get acquired for talent, creating a dynamic where few remain independent companies

- Companies building voice-first products need specialized expertise in acoustic analysis, emotional intelligence, and conversation design that startups like Hume pioneered

- Voice interfaces are experiencing rapid adoption as infrastructure companies like ElevenLabs hit $330M+ revenue, validating commercial demand across industries

- The acquihire trend reflects how AI development has shifted from building from scratch to acquiring proven capabilities faster than internal development allows

Related Articles

- Google's Hume AI Acquisition: The Future of Emotionally Intelligent Voice Assistants [2025]

- Apple's AI Pivot: How the New Siri Could Compete With ChatGPT [2025]

- Alexa Plus Gets Sassy: Why AI Assistants Are Developing Attitude [2025]

- Voice Orchestration in India: How Bolna's $6.3M Seed Round Is Reshaping AI Voice Tech [2025]

- Apple's AI Pin: What We Know About the Wearable Device [2025]

- Apple's Siri AI Overhaul: Inside the ChatGPT Competitor Coming to iPhone [2025]

![Google's Hume AI Acquisition: Why Voice Is Winning [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-s-hume-ai-acquisition-why-voice-is-winning-2025/image-1-1769096418212.jpg)