House Sysadmin Stole 200 Phones: What This Breach Reveals [2025]

You'd think stealing 200 government phones would be hard. Turns out, it's embarrassingly easy—especially when you're the person authorized to order them in the first place.

In early 2025, federal investigators uncovered one of the most brazen asset theft schemes in recent congressional history. A 43-year-old systems administrator working for the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure had ordered 240 brand-new smartphones, shipped them to his home, and methodically sold over 200 of them to a local pawn shop. The alleged crime cost taxpayers $150,000 and exposed critical gaps in government IT asset management, device tracking, and internal controls, as reported by NBC News.

But here's what makes this case fascinating—and terrifying—from a cybersecurity perspective. It wasn't sophisticated hacking that caught him. It wasn't advanced forensics or a surprise audit. It was a random person who bought a phone on eBay, turned it on, and saw a House IT help desk number on the startup screen. That person called. And everything unraveled.

This incident reveals deep structural problems in how government agencies track, manage, and secure mobile devices. It exposes weaknesses in procurement oversight, inventory controls, and the false sense of security that comes from complex device management software. Most critically, it shows that even the smallest slip-up—one phone not disposed of properly—can expose an entire criminal operation.

Let's break down exactly what happened, how investigators caught him, what the security implications are, and what government agencies (and companies) should be doing differently.

The Anatomy of the Theft

Christopher Southerland wasn't some hacker breaking into secure systems. He had legitimate access. That's what made him dangerous.

As a systems administrator for the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, Southerland had real authority. The committee employs roughly 80 staffers. In his role, Southerland could requisition mobile devices—a normal part of IT operations. When people leave, when technology refreshes, when new positions open up, IT admins order phones.

But in early 2023, something changed. Instead of ordering 80–100 phones across the year, Southerland ordered 240 all at once. Not to committee offices. Not to a secure warehouse. To his home address in Maryland, according to BizPac Review.

Two hundred and forty phones. That's three times the total staff size.

No red flags. No approval barriers. No "why does one person need 240 phones?" response from whoever processes purchase orders. The system trusted him. He had the authority. And that authority was never questioned.

Once the phones arrived, the scheme shifted into its operational phase. Southerland couldn't just dump 200 phones on eBay individually. That would create an obvious pattern. Instead, he sold them to a local pawn shop. But even that carried risk—government devices often have software that prevents resale.

So Southerland gave the pawn shop specific instructions: sell these phones only "in parts." Disassemble them. Sell the screens separately, the batteries separately, the logic boards separately. This would bypass the House's mobile device management (MDM) software, which could theoretically track and control the devices remotely. A phone in pieces is much harder to track than a phone intact, as noted by Fox 5 DC.

For a while, it worked. The pawn shop moved inventory. Southerland got paid. No one noticed.

Then came the mistake that unraveled everything.

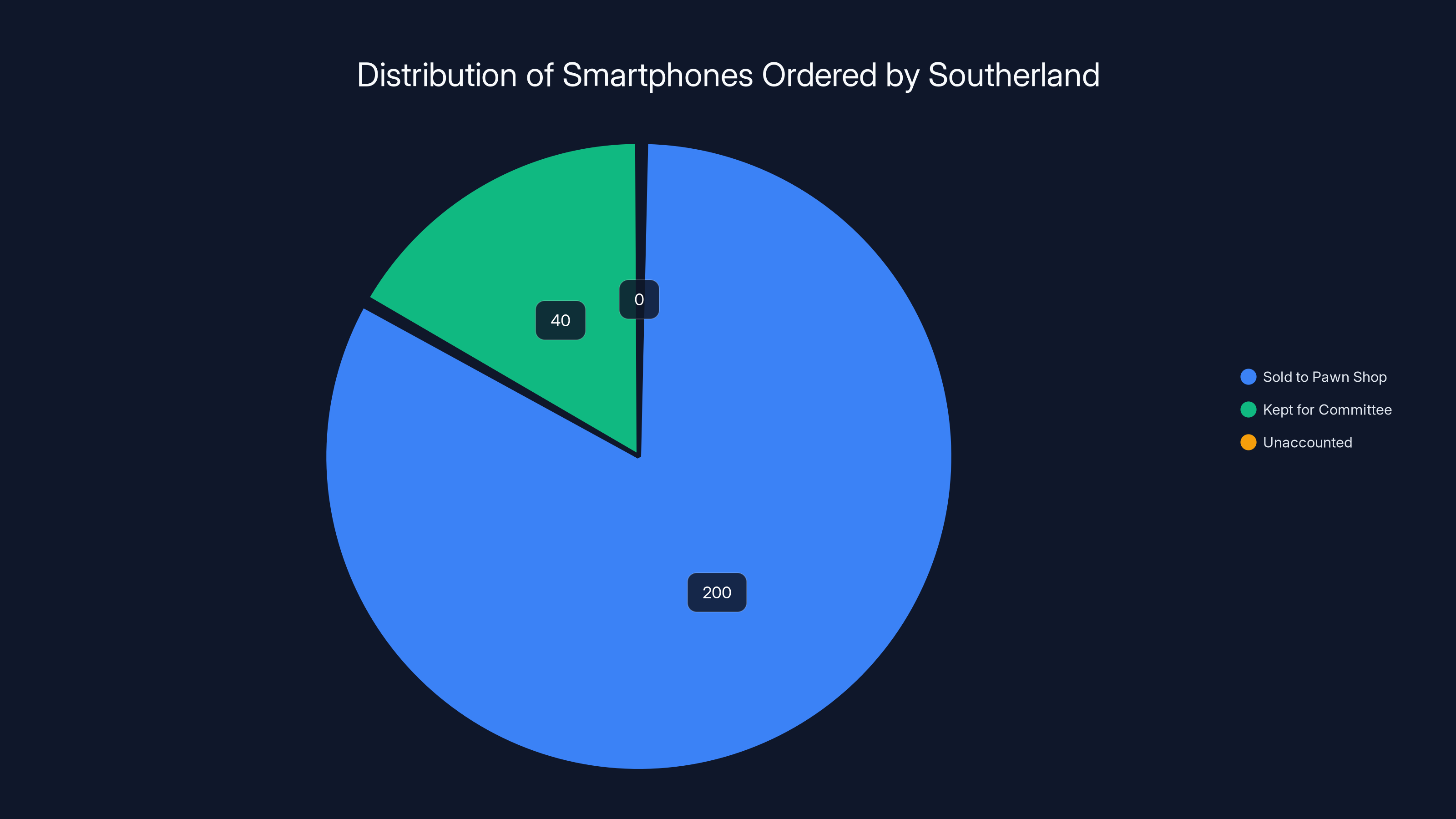

Estimated data shows that out of 240 smartphones ordered, 200 were sold to a pawn shop, while 40 were kept for committee use. No phones were unaccounted for.

How One Phone Exposed Everything

At least one phone—a single, unbroken device—made it through the pawn shop chain without being disassembled. Instead of staying in pieces on a shelf, it ended up intact on eBay.

Someone bought it. And when they powered it on, they didn't see the standard Android or iOS startup screen. They saw something unexpected: a phone number for the House of Representatives Technology Service Desk.

That's not normal. That's not a consumer phone. That's a government device. And someone had just bought it secondhand, which shouldn't be possible.

The buyer did what any reasonable person would do. They called the number.

This single phone call triggered an investigation. House IT staff suddenly realized that government phones were being resold on eBay. They launched a broader investigation. They traced the supply chain backward. They dug into procurement records. They discovered Southerland's massive order in early 2023. They found records of missing inventory. They calculated the loss, as detailed by the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure.

Over $150,000 in taxpayer money. Gone.

Investigators built a case. In December 2025, Southerland was indicted. On January 8, 2026, he was arrested. He was released on personal recognizance with orders to stay away from Capitol grounds. His court date was scheduled for later that month, according to The National Desk.

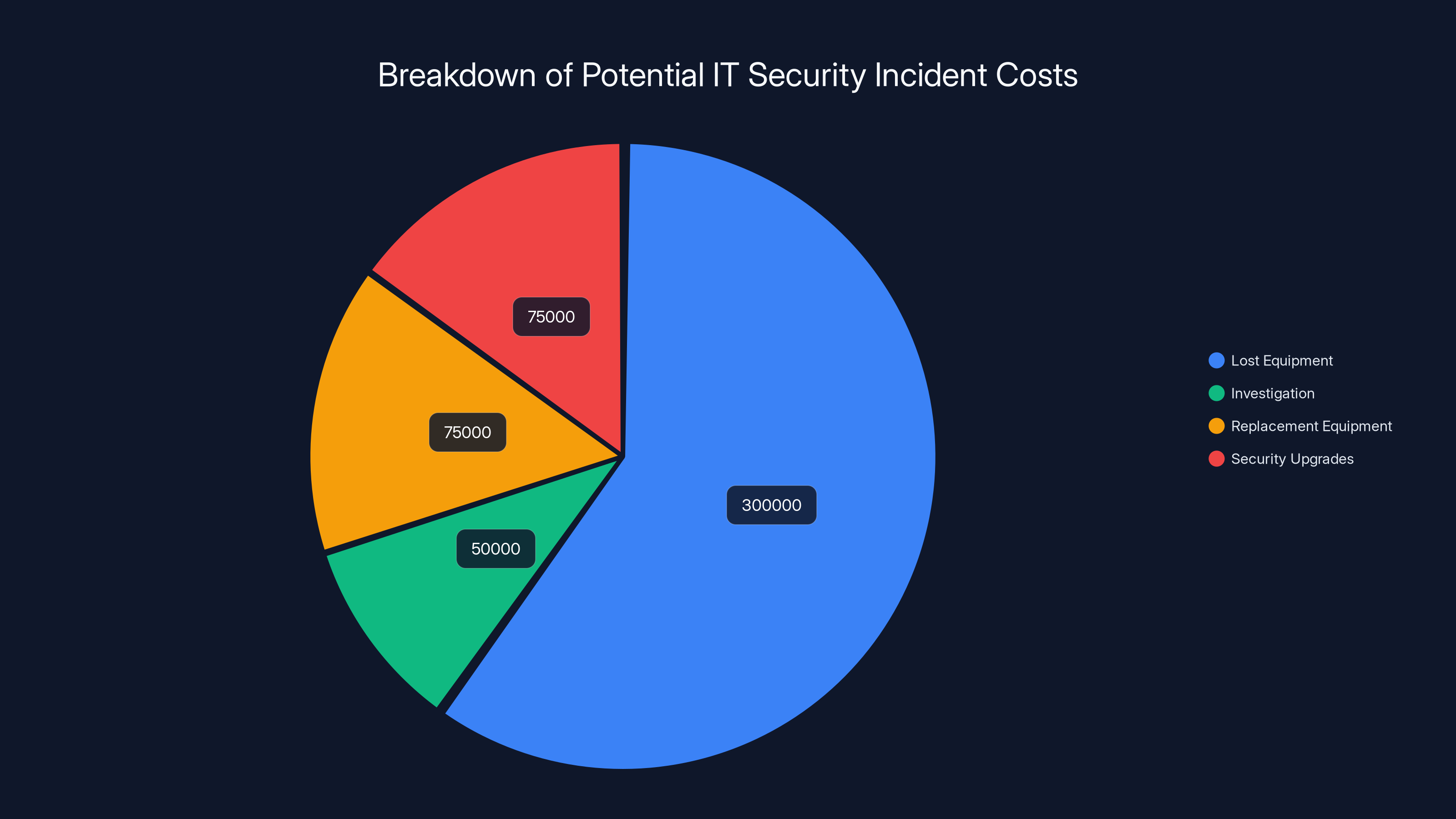

Estimated data shows that lost equipment accounts for the largest portion of costs in a corporate IT security incident, followed by replacement and upgrades.

The Crucial Security Failures

This case reveals multiple, cascading failures in government IT asset management. Each failure alone might not be catastrophic. Together, they created the perfect conditions for theft.

Procurement Controls Are Nonexistent

No one questioned why a single IT administrator needed to order 240 phones for an 80-person committee. There should have been approval workflows. A procurement officer should have asked basic questions. A supervisor should have required justification.

Instead, the order went through. The cost was approximately

Government procurement is broken in many agencies. Spending authority gets delegated too far down the chain. Checks and balances erode. One person can spend six figures without friction.

Inventory Management Is Broken

When phones arrived, nobody physically verified them. Nobody cross-checked delivery receipts against actual inventory in any system. Nobody tracked where the phones went. Were they in a secure storage facility? Were they being distributed to staffers? The system just... assumed they existed.

This is a classic inventory control failure. You can't manage what you don't track. And government agencies often don't track IT assets with any rigor, as noted by Live Now Fox.

Compare this to how retail companies manage inventory. Every item gets barcode-scanned. Every movement gets logged. Every discrepancy triggers alerts. Government IT doesn't operate this way. The assumption is that authorized personnel won't steal. And when that assumption breaks, there's no second line of defense.

Device Management Software Creates False Security

The House had mobile device management software installed on these phones. This software can remotely wipe devices, lock them, track their location, and enforce security policies. On the surface, it seems like a strong control.

But here's the problem: it only works on intact devices. The moment a phone gets disassembled, the MDM software is useless. It can't track pieces. It can't wipe a logic board. It can't control a screen.

This isn't a flaw in MDM itself. It's a flaw in relying on MDM as your only control. You need multiple layers: procurement controls, inventory checks, physical security, asset tagging, regular audits. MDM should be one layer. It shouldn't be the entire security model, as discussed in Wiz's Zero Trust Architecture guide.

Nobody Audits Asset Disposal

Government agencies are supposed to have procedures for disposing of old IT equipment. Phones should be securely wiped. Data should be destroyed. Equipment should be sent to certified e-waste recyclers. This is both a security requirement and an environmental requirement.

But auditing device disposal is tedious. It requires tracking every device through its entire lifecycle, from procurement to final destruction. Many agencies skip this step. Or they do it sporadically. A few phones go missing here, a few there—it gets written off as normal loss.

Southerland exploited this gap. He created the devices from scratch, so there was no "old inventory" disposal story. But the underlying problem is real: government agencies don't have rigorous processes for tracking where every device ends up, as noted by The Hill.

What Southerland's LinkedIn Profile Reveals

Before his arrest, Southerland had a LinkedIn profile listing his technical skills. Python. Linux administration. Microsoft systems like Azure and Active Directory. His profile emphasized expertise in "coordinating complex projects involving multiple stakeholders" and "updating infrastructure such as virtual environments to ensure the smooth operation of processes."

He also wrote: "I have a passion for customer service and can interact with team members in a professional and courteous manner."

This is instructive. From a technical standpoint, Southerland was competent. He understood infrastructure. He could navigate complex systems. He had the knowledge to plan this theft carefully—to understand that intact phones would connect to MDM software, to know that a pawn shop could break them down, to realize that pieces wouldn't trigger alerts.

But he overestimated his own cleverness. He assumed that one minor change—disassembling phones—would be enough to evade tracking. He didn't account for the possibility that someone, somewhere, would fail to follow his instructions. He didn't realize that one unbroken phone, sold on a public marketplace, would get picked up by someone curious enough to call a mysterious phone number.

This is a common pattern in insider threat cases. Technically skilled people convince themselves that they've thought of everything. They haven't. They miss something obvious.

Estimated data shows potential penalties for Southerland, highlighting the severity of federal charges. Prison time ranges from 5 to 10 years, fines up to $250,000, and probation from 3 to 5 years.

Government Mobile Device Management Practices

The House, like most government agencies, uses MDM software to control and monitor employee devices. This is a standard practice. Government employees shouldn't have unlimited freedom with work phones—there are security, privacy, and compliance reasons to enforce policies.

Typical MDM capabilities include:

- Remote wipe: Erase all data on a stolen or lost device

- Enrollment enforcement: Require devices to be enrolled before they connect to networks

- Policy enforcement: Mandate screen locks, encryption, app restrictions

- Location tracking: Know where devices are at any given time

- Application management: Control what apps can be installed

- Compliance reporting: Generate audits showing device status and security posture

These are powerful tools. In theory, they make it nearly impossible to steal government phones, because once they're lost or stolen, they can be remotely erased and locked.

But theory and practice diverge. Southerland's method—deliberately breaking phones—exposed a fundamental weakness. MDM software assumes that devices remain intact. A phone that's been disassembled, sold for parts, and recombined in a consumer setting is no longer managed by the government. It's just a used phone.

This isn't unique to the House. Every government agency with MDM-controlled devices faces the same vulnerability. If someone with legitimate access to procurement deliberately orders devices and removes them from the MDM network, the software can't help.

The Role of the Pawn Shop

The pawn shop played a crucial—and ultimately harmful—role in this scheme.

Southerland gave the pawn shop explicit instructions: sell phones "in parts" only. The shop complied with these instructions for most of the inventory. They disassembled phones and sold components separately. This was supposed to protect the operation.

But at some point, the system failed. Either the pawn shop employee got lazy, or they misunderstood the instruction, or they realized they could make more money selling an intact phone than selling parts. Whatever the reason, at least one phone remained whole.

The pawn shop also failed at what should have been a basic check: verifying that the phones they were purchasing were actually legitimate secondhand inventory. A pawn shop that receives 200 phones at once should have asked questions. Where did these come from? Why are there so many? Why do they all look brand-new? Why are you telling me to disassemble them?

A responsible pawn shop might have verified that Southerland had the right to sell these phones. Some might have checked serial numbers or contacted the manufacturer. Instead, the pawn shop seems to have accepted the transaction without much scrutiny—which is also typical of pawn shops, which generally don't operate with the due diligence of licensed retailers, as noted by All About Cookies.

Estimated data shows significant over-procurement and cost inefficiencies, with 240 phones ordered for only 80 users, costing approximately $168,000.

eBay's Role in Exposing the Scheme

eBay actually wasn't the problem here. eBay was the solution.

Southerland didn't sell the phones to eBay directly. Someone—probably a reseller—bought unassembled phones from the pawn shop, reassembled at least one of them, and listed it on eBay. The platform itself operates with standard marketplace protections. Sellers list items, buyers purchase them, transactions go through.

But the phone itself contained evidence of its origin. The House of Representatives branding, the tech desk number on startup—these were hard-coded into the device's firmware or system. They survived the disassembly and reassembly process. They were visible the moment someone powered on the phone.

This is actually a good security practice. Government devices should clearly identify themselves as government property. This makes them easier to track if lost or stolen. And in this case, it made it impossible for the phones to blend into the consumer market completely.

eBay's role was incidental. It was simply the platform where the breach in Southerland's operation manifested. The real exposure came from the device itself.

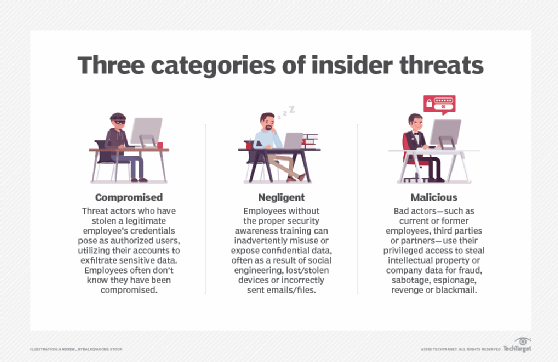

Comparing This to Other Insider Threats

This case isn't unique. Insider threats involving asset theft happen regularly, especially in government and large corporations.

When IT administrators steal company or government assets, there are several common patterns:

Pattern 1: The Slow Drain. An employee gradually takes small amounts of hardware over months or years. A phone here, a monitor there, a network device somewhere else. The cumulative theft adds up, but each individual incident is small enough to avoid suspicion.

Pattern 2: The Bulk Order. An employee with procurement authority orders more equipment than is needed, then claims it was lost or stolen or damaged. They pocket the difference. This is what Southerland did—but he actually sold the equipment rather than creating a paper trail of damaged inventory.

Pattern 3: The Authorized Access Abuse. An employee uses their legitimate access to systems to modify records, approve unauthorized transactions, or grant themselves special privileges. The theft is hidden in paperwork.

Pattern 4: The Collusion Scheme. Multiple employees work together to steal. One handles procurement, another covers up missing inventory, a third handles resale. The work is distributed, making it harder to trace to any single person.

Southerland used elements of Patterns 2 and 4 (with the pawn shop as his unwitting accomplice). He placed a massive order, then worked with a local business to move the inventory.

What separated this from a "successful" theft was the error at the end: that one unbroken phone that made it through to eBay. Without that mistake, the scheme might have continued undetected indefinitely.

The investigation into the resale of government devices was triggered by a single phone call in early 2023, leading to an indictment in December 2025 and an arrest in January 2026. Estimated data.

How This Could Have Been Prevented

From a government IT perspective, there are straightforward controls that would have made this theft impossible or detectable.

Segregation of Duties

One person shouldn't have sole authority to order phones, approve purchases, and sign off on inventory. The process should require multiple people at multiple stages.

Example workflow:

- IT Manager approves the request based on legitimate business need

- Procurement specialist processes the order and verifies it's correct

- Finance approves the expense against budget

- Receiving team verifies and inventories the delivered equipment

- IT manager assigns devices to actual end users

- Periodic audits verify that devices match assignments

If this workflow had been in place, Southerland couldn't have ordered 240 phones and shipped them to his home without others noticing.

Real-Time Inventory Tracking

Every government device should be tagged with a unique identifier and tracked in a real-time inventory system. When a device is ordered, it appears in inventory. When it's assigned to an employee, that assignment is logged. When it's returned or disposed of, that's logged too.

If inventory tracking had been in place, investigators would have immediately seen that 240 phones were ordered but only ~40 were assigned to actual employees. The missing 200 would have triggered an investigation immediately, not months later.

Physical Security and Regular Audits

New devices should be stored in a secure, climate-controlled facility—not in individual homes. Regular audits should verify that physical inventory matches what's in the system. Random spot checks of device serial numbers and MDM enrollment status should be routine.

Vendor Controls

When a system administrator wants to order devices, the system should check whether the request is within normal parameters. 240 phones for an 80-person team isn't normal. Automated alerts should flag this for review.

Suppliers themselves could also be required to verify that large orders have proper authorization before shipping. If the vendor had called the House to confirm that a single person should receive 240 phones at a residential address, red flags would have gone up.

The Implications for Corporate IT Security

This isn't just a government problem. Private companies face similar vulnerabilities.

Corporate IT departments manage thousands of devices—laptops, phones, tablets, network equipment. If procurement controls are weak, if inventory tracking is poor, if one person has too much authority, insider threats can cause massive losses.

Consider a company with 500 employees. If an IT administrator ordered 200 laptops (at

Companies should implement the same controls that government should implement: segregation of duties, real-time tracking, periodic audits, vendor verification, and strong MDM policies.

Legal Consequences for Southerland

Christopher Southerland faced serious federal charges. The indictment would likely include wire fraud, theft of government property, and conspiracy (if the pawn shop knowingly participated).

For theft of government property, penalties can include:

- Prison time: 5–10 years for significant thefts

- Fines: Up to $250,000 or more

- Restitution: Full repayment to the government for stolen property

- Loss of security clearance: Making future government work impossible

- Probation: Supervised release for 3–5 years after prison

At the time of this writing (January 2026), Southerland's case was in the early stages. He'd pled not guilty and was released on personal recognizance, suggesting the court didn't view him as a flight risk. His court date was scheduled for later that month, as reported by Live Now Fox.

The actual charges and penalties would depend on what federal prosecutors decided to pursue and what evidence they could present. The fact that investigators traced the phones, identified the procurement order, and connected it to Southerland's home address suggests they have solid evidence.

What This Case Teaches About Asset Management

The Southerland case is a masterclass in asset management failures and how a single person's curiosity can expose an entire criminal operation.

Key lessons:

1. Trust is not a control. Government and corporate IT often relies too heavily on "trustworthiness." We trust that authorized personnel won't steal. That's not a control. It's hope. Real controls are processes, verification, and oversight.

2. Scale matters. A small order might go unnoticed. A massive order (240 phones for an 80-person committee) should trigger automated alerts. When requests exceed reasonable parameters, approval should be required.

3. Inventory tracking is essential. If you can't account for every device, you can't catch theft. Real-time tracking systems (even if just spreadsheets with regular audits) would have made this impossible.

4. MDM isn't enough. Mobile device management software is helpful, but it's one layer. It doesn't prevent procurement fraud. It doesn't prevent initial theft. Criminals who know how MDM works can plan around it.

5. Disposal processes matter. Devices need to be securely wiped and tracked through disposal. If you don't know where devices end up, you can't catch people who resell them.

6. One mistake unravels everything. Southerland planned carefully, worked with a pawn shop, gave explicit instructions about disassembling devices. But one unbroken phone on eBay ended the operation. Criminals always assume some chance of discovery.

Why Government IT Security Lags Behind Private Sector

Government agencies generally have weaker IT security practices than competitive private companies. Why?

Budget constraints: Government IT departments often operate on tight budgets. They can't afford modern asset management systems, comprehensive monitoring tools, or large security teams.

Bureaucracy: Procurement requires multiple approvals. Budget cycles are rigid. Implementing new systems takes years. This slowness makes it hard to respond to emerging threats.

Hiring and retention: Government IT salaries lag private sector by 30–40%. Good people leave for better-paying private jobs. This creates gaps in expertise and experience.

Culture of trust: Government has traditionally relied on background checks and security clearances, then assumed people wouldn't betray that trust. This is changing, but slowly.

Legacy systems: Much government IT infrastructure is old. Replacing it is expensive and disruptive. So agencies run mixed environments with some modern security tools and some ancient systems.

None of this excuses the failures in the Southerland case. But it explains why government IT sometimes feels decades behind best practices.

Looking Forward: What Needs to Change

If agencies learned from this case, they would:

Implement real-time asset tracking. Every device gets a unique ID, tracked from procurement through disposal. Automated alerts flag discrepancies.

Enforce segregation of duties. No one person can order, approve, receive, and assign devices. Multiple people must be involved at each stage.

Require vendor verification. When large orders are placed, vendors should verify that the order is legitimate before shipping to unusual addresses.

Audit regularly and randomly. Physical spot checks of device inventory should happen monthly. Serial numbers should be verified against MDM enrollment.

Establish clear disposal procedures. Devices should only be disposed of through certified e-waste recyclers. The entire process should be documented and audited.

Train IT staff on insider threat risks. Employees should understand that theft is possible, how it happens, and why controls exist.

Monitor unusual behavior. IT systems should alert supervisors when employees are accessing unusual data, modifying procurement records, or making unusual network connections.

These aren't expensive. They're not even complicated. They're just basic operational discipline. The fact that they were absent from the House of Representatives—arguably the most important technology environment in the U.S. government—suggests that many agencies aren't taking insider threat seriously enough.

The Human Element in Security Failures

Ultimately, this case is about people, not technology.

Southerland was a skilled administrator who convinced himself he could steal $150K in equipment and not get caught. He planned carefully. He used technical knowledge to his advantage. He worked with others to offload inventory. But he made a human mistake—he didn't account for the possibility that one phone wouldn't get disassembled, that one person would call a mysterious number out of curiosity, that one call would trigger an investigation.

This is a fundamental truth of security: you can build the most sophisticated systems, but they fail when people don't follow processes or when they deliberately circumvent them.

The person who caught him wasn't a security analyst with advanced forensics tools. It was someone who bought a phone on eBay and thought, "That's weird, let me call this number."

That's worth remembering when you're designing security systems. Sometimes the most powerful defense isn't technology. It's creating an environment where people report suspicious things, where processes are verified by multiple people, and where no single person has enough authority to cause massive damage.

Southerland had too much authority. No one questioned his judgment. No one verified his orders. And when the first sign of a problem appeared—a government phone on eBay—it took a random person calling a help desk number for anyone to care enough to investigate.

FAQ

What exactly did Christopher Southerland do?

Southerland, a 43-year-old systems administrator for the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, ordered 240 brand-new smartphones and had them shipped to his home address in Maryland in early 2023. He then sold over 200 of these phones to a local pawn shop for personal profit. This resulted in a loss of approximately $150,000 in taxpayer money.

How was the scheme discovered?

The scheme was uncovered when at least one phone escaped the pawn shop's disassembly process and was sold intact on eBay. When a buyer powered on the phone, they saw the House of Representatives Technology Service Desk number displayed on the startup screen. The curious buyer called this number, which alerted House IT staff that government phones were being sold on the secondary market, triggering a full investigation.

Why did Southerland order so many phones?

The government alleged that Southerland deliberately ordered far more phones than the committee needed (240 devices for approximately 80 staffers) specifically to create excess inventory that he could steal and resell. This strategy allowed him to profit from taxpayer-funded equipment through a secondary market resale operation.

What security failures allowed this to happen?

Multiple failures contributed: procurement controls didn't question why one IT administrator needed 240 phones, inventory tracking systems didn't flag missing devices, segregation of duties was absent (one person had too much authority), and disposal procedures weren't enforced. Mobile device management software, while present, was bypassed when phones were disassembled into parts before being resold.

What charges did Southerland face?

Southerland was indicted in December 2025 and arrested on January 8, 2026. While the exact charges weren't fully disclosed, federal prosecutors likely pursued wire fraud charges (for the scheme to defraud the government) and theft of government property. He pled not guilty and was released on personal recognizance with orders to stay away from Capitol grounds.

Could this happen in private companies?

Absolutely. Any organization where one employee has significant procurement authority and weak oversight faces similar insider threat risks. Private companies with poor asset management, weak segregation of duties, and limited inventory tracking can experience similar theft scenarios. The same preventive controls apply: multiple approvers, real-time tracking, periodic audits, and vendor verification.

What does this reveal about government IT security?

This case highlights systemic weaknesses in government IT asset management practices. Government agencies often lag behind private companies in implementing modern controls due to budget constraints, bureaucratic processes, hiring difficulties, and cultural assumptions that trusted employees won't commit fraud. This case demonstrates that trust alone is insufficient as a security control.

How can organizations prevent similar thefts?

Organizations should implement segregation of duties (requiring multiple people to approve major purchases), real-time inventory tracking with automated alerts for unusual orders, vendor verification procedures, regular audits of physical equipment against system records, secure device storage rather than individual homes, and clear disposal procedures with documentation. Additionally, monitoring unusual employee behavior and creating a culture where suspicious activities are reported helps catch insider threats earlier.

The Bottom Line

The Southerland case is a cautionary tale about complacency in asset management and the dangers of concentrated authority. A skilled IT administrator with too much power, inadequate oversight, and weak controls managed to orchestrate a $150,000 theft from the U.S. House of Representatives.

But it's also a story about how systems work when they work well. The moment a single phone made it through Southerland's careful planning and onto eBay, the entire operation became vulnerable. Someone's curiosity. A simple phone call. An investigation. An indictment.

Government agencies and private companies alike should take note. You can't eliminate insider threat risk entirely—employees will always have some level of legitimate access—but you can dramatically reduce it through proper controls, oversight, and verification. No single person should have the authority that Southerland had. No orders should go through without questioning. No inventory should be unaccounted for.

The fact that this happened in Congress—one of the most scrutinized organizations in America—suggests that many other agencies face similar vulnerabilities. It's time for a systematic review of how government manages and tracks IT assets. Not because we should assume the worst about government employees, but because we should assume that some bad actors exist, and our systems should be designed to catch them.

Key Takeaways

- A House sysadmin ordered 240 phones for an 80-person committee, shipped them home, and sold 200+ to pawn shops for $150,000—exposing critical government IT asset management failures

- The scheme was exposed not by sophisticated cybersecurity tools, but by a random person calling a House IT help desk number they found on a phone purchased on eBay

- Multiple security failures enabled this: no procurement approval process, no inventory tracking, no segregation of duties, and reliance on MDM software that could be bypassed by disassembling devices

- Government agencies lag behind private companies in implementing basic controls like real-time asset tracking, vendor verification, and regular audits due to budget constraints and bureaucratic processes

- Prevention requires segregation of duties across multiple approvers, real-time inventory tracking with automated alerts, vendor verification, physical security, and regular audits—not trust alone

Related Articles

- Kimsuky QR Code Phishing: How North Korean Hackers Bypass MFA [2025]

- Salt Typhoon Hacks Congressional Emails: What You Need to Know [2025]

- How to Protect iPhone & Android From Spyware [2025]

- Cybersecurity Insiders Plead Guilty to ALPHV Ransomware Attacks [2025]

- ToneShell Backdoor: Inside the Chinese Government Espionage Campaign [2025]

- Juice Jacking: How to Protect Your Phone from Public Charging Threats [2025]

![House Sysadmin Stole 200 Phones: What This Breach Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/house-sysadmin-stole-200-phones-what-this-breach-reveals-202/image-1-1768424801664.jpg)