How Bill Gates Predicted Adaptive AI in 1983: The History of Software That Learns

It's easy to think artificial intelligence exploded overnight. You blink, Chat GPT hits 100 million users, and suddenly every software company is slapping "AI-powered" on their product. But the truth? The smartest people in tech saw this coming decades ago.

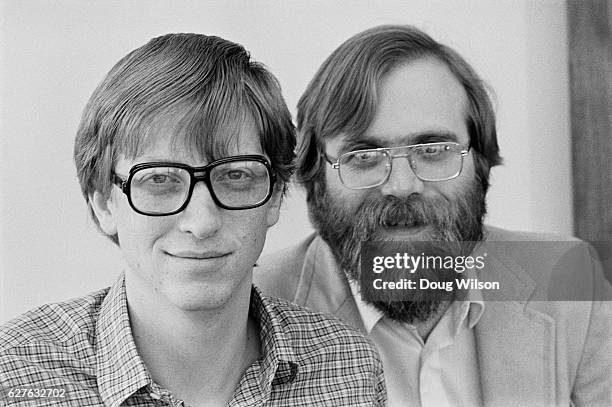

In 1983, when most people were thinking about AI as a sci-fi fantasy, Bill Gates and his brilliant software architect Charles Simonyi were already talking about something they called "softer software." Not artificial intelligence. Not machine learning. Just software that could learn your habits and adapt to the way you actually work.

The crazy part? Their 1983 vision describes exactly what modern AI assistants do today. Personalization engines. Adaptive copilots. Smart suggestions that anticipate what you need. It was all there, four decades before we had the computing power or training data to make it real.

This isn't just tech history trivia. It's a masterclass in how visionary thinking works—identifying what users actually need, stripping away hype, and focusing on practical solutions that evolve. Because here's the thing: Gates and Simonyi didn't care about the philosophy of what makes something "artificial intelligence." They cared about solving real problems for real people.

Let's dive into how two of tech's most influential minds predicted the future of software, why the industry got distracted by hype for decades, and what their thinking tells us about where AI is actually going.

TL; DR

- Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi proposed "softer software" in 1983, a vision of programs that learn user habits and adapt behavior over time

- They deliberately avoided the term "AI" because it was too loaded with philosophical baggage and unrealistic expectations

- Their concept predicted modern adaptive assistants, personalization engines, and copilots by 40+ years

- The industry repeatedly fell for AI hype cycles while the real value came from practical, incremental learning systems

- Modern software finally delivers on that 1983 vision, proving Gates and Simonyi were thinking about problems that mattered

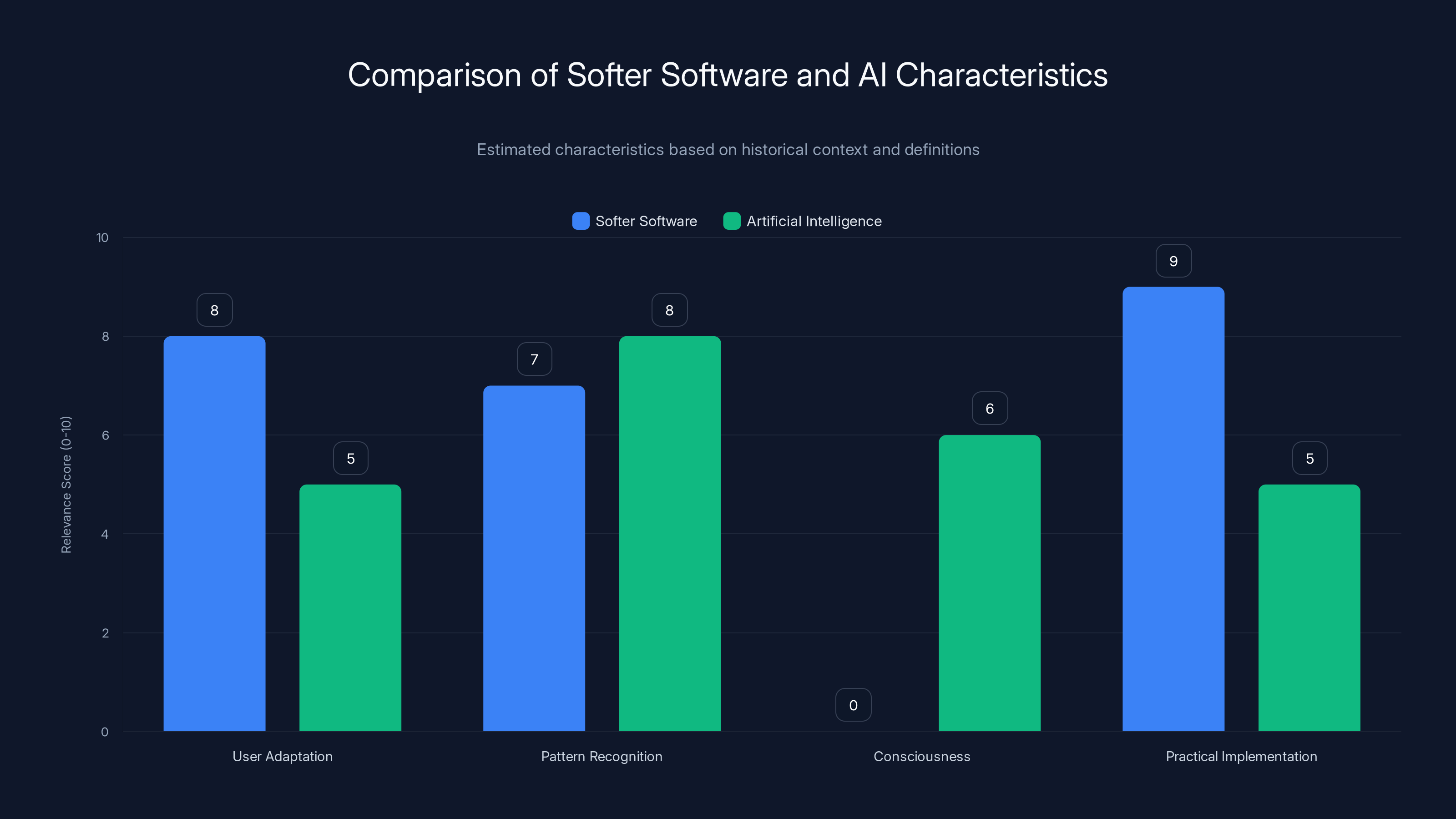

Softer software emphasizes user adaptation and practical implementation, while AI focuses more on pattern recognition and theoretical consciousness. Estimated data based on conceptual differences.

The 1985 AI Hype Cycle: Nothing New Under the Sun

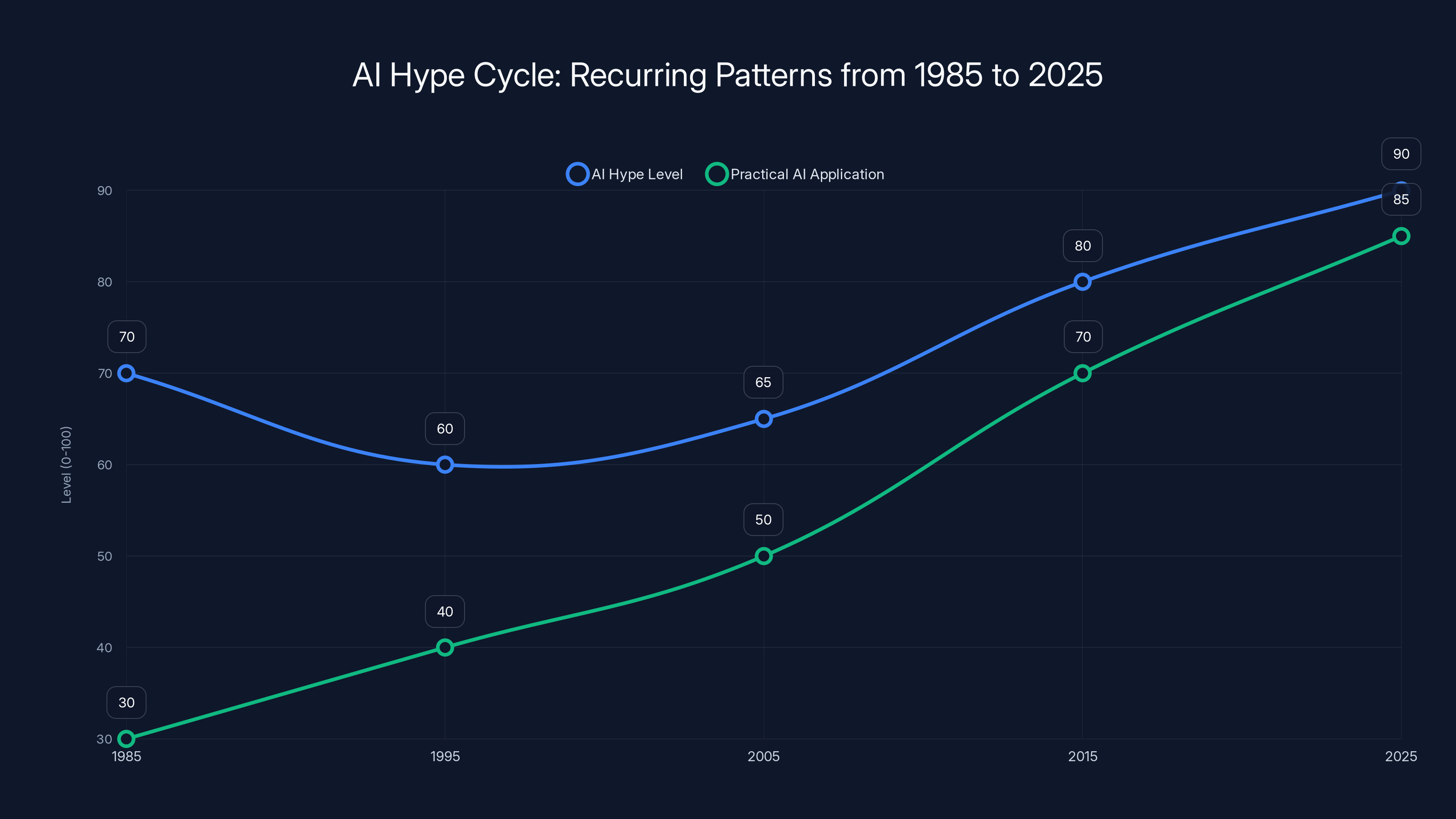

You want to know something wild? In 1985, the industry was already panicking about AI hype. Info World magazine ran an editorial asking whether 1985 would finally be "the year when artificial intelligence emerges from the ivory towers of academia." The answer, of course, was no. Not in 1985. Not in 1995. Not even in 2015.

But the way they described the problem sounds exactly like 2023.

The magazine's editorial director, James E. Fawcette, identified what would become a recurring pattern in tech: software companies desperate for a new hook to sell products started slapping "AI" on everything. The problem wasn't that AI was impossible. The problem was that the term itself became a barrier to understanding what software could actually do.

"The words artificial intelligence are a barrier to the technology's application," Fawcette wrote. "They are so value and image-laden that the term itself obstructs practical work."

Sound familiar? How many times have you heard "AI" used as a marketing term for something that's just... slightly smarter search, or a better recommendation algorithm?

Fawcette identified two specific problems with how AI was being abused in the mid-1980s. The first was "AI-hype"—vacuous programs promising to run your entire business if you just fed it some data. The second was what he called "Rube Goldberg overdesign syndrome"—massively over-engineered systems built to solve grand philosophical problems instead of practical ones.

Both problems are still destroying software in 2025. We've got companies building elaborate AI systems that nobody actually needs, and we've got products that promise AI will replace entire job categories when what they actually do is slightly optimize a spreadsheet.

The difference between 1985 and now? We finally have the computing power and data to make some of those promises actually work. But the core insight from that era still applies: the most useful software isn't the one promising to think for you. It's the one that learns how you think and adapts accordingly.

Charles Simonyi's "Softer Software" Vision: The Real Innovation

Here's where it gets interesting. While everyone was obsessing over whether machines could achieve true artificial intelligence, Charles Simonyi was asking a different question: what if software could just... get better at helping you?

Simonyi wasn't some academic theorist. He was the guy who led the teams that built Microsoft Word and Excel. If you've ever used a pull-down menu, clicked an icon, or used a WYSIWYG editor, you're using his legacy. The man understood user interfaces in a way most people still don't.

In an August 1983 Info World piece, Simonyi made the case against even using the term "artificial intelligence."

"AI is a very complex goal," he said. "You need a philosopher to determine what AI is." Instead of chasing that philosophical problem, why not focus on something empirical? Something that actually works?

He called it "softer software."

The definition was beautiful in its simplicity: software that "modifies its behavior over time, based on its experience with the user." The goal wasn't to create thinking machines. The goal was to make software that learned your patterns and adapted to help you work more effectively.

Inf World gave a concrete example. Imagine you're using a word processor and you consistently request double-spacing, right-margin justification, and a particular heading on each page. With softer software, the program would "remember" these preferences and suggest them, or apply them automatically the next time you're doing similar work.

Today, that sounds obvious. Your email client learns your contacts. Your phone predicts your next word. Your music app recommends songs based on what you've listened to. But in 1983, this was genuinely radical. Most software was static. It did what you told it to do and nothing more. The idea that software could adapt? That was the innovation.

Simonyi took it further. He predicted that in the future, "the computer will be a working partner in the sense of anticipating your behavior and suggesting things to you. It will mold itself based on events that have taken place over a period of time."

Read that again. That's basically a description of modern AI copilots. He said that in 1983.

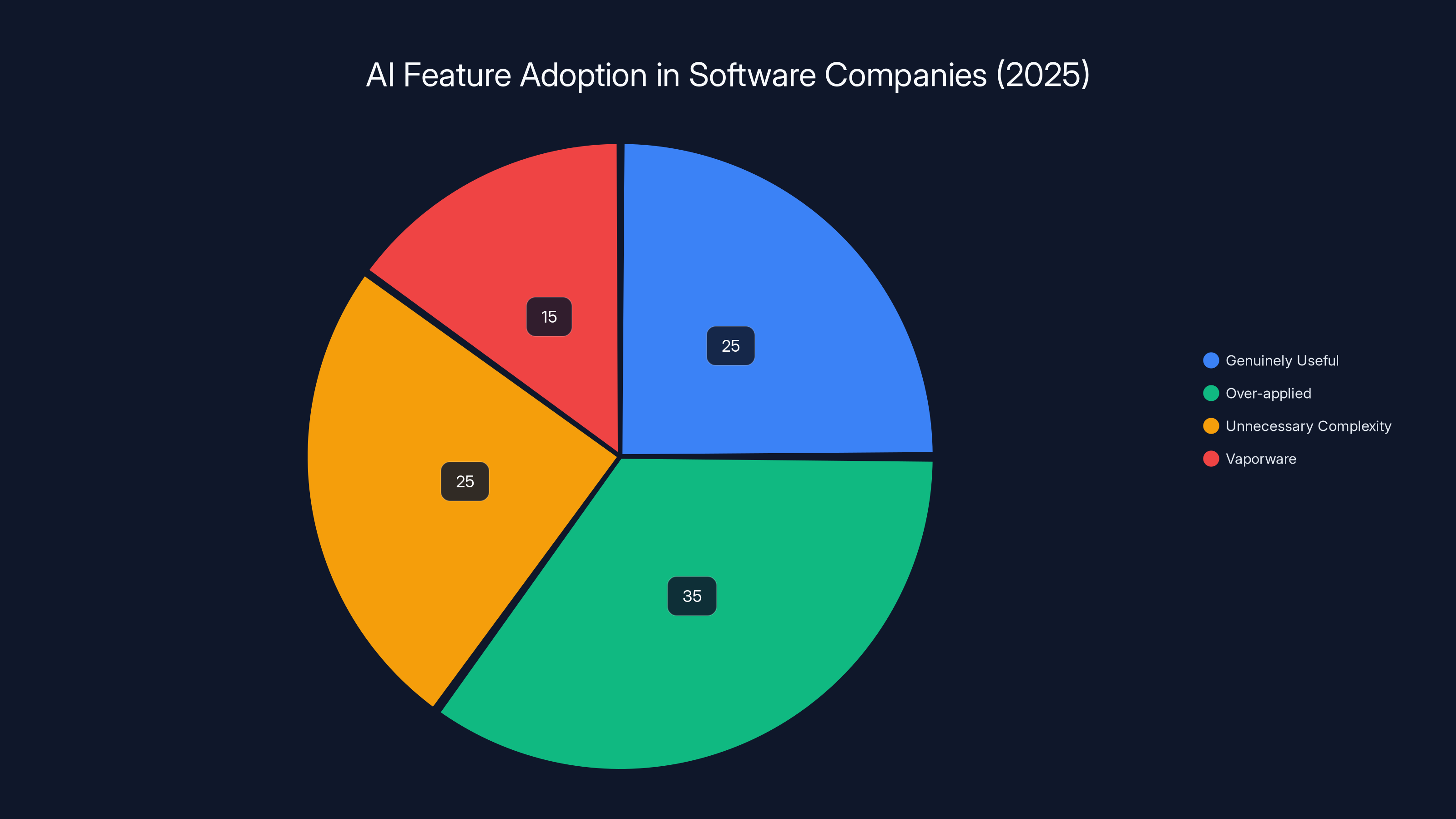

In 2025, only about 25% of AI features are genuinely useful, while 75% result in over-application, unnecessary complexity, or vaporware. (Estimated data)

Microsoft's Expert Systems: The First Real Implementation

Now, you might be thinking: okay, so they had this nice theory. But did they actually build anything?

Yes. Microsoft started taking "tentative steps" toward softer software with what they called "expert systems." These were designed to improve the functionality of Multiplan, Microsoft's spreadsheet program at the time.

Instead of throwing users into a blank grid of empty cells, the expert systems could help build formulas, create charts, and suggest functions based on what the user was trying to do. It learned patterns. It offered helpful suggestions. It made a complex tool less intimidating for non-experts.

Was this artificial intelligence in the philosophical sense? No. Was it useful? Absolutely.

Multiplan itself eventually got superseded by Excel, which became the gold standard spreadsheet because it understood users. Excel wasn't the most mathematically powerful option. It was the most intuitive. It adapted to how people actually worked. That's the Simonyi influence right there.

The expert systems approach never became a named feature. You didn't buy "Simonyi's Adaptive Software Engine 1.0." Instead, that philosophy got baked into how Microsoft built products—responsiveness to user behavior, intelligent defaults, features that anticipate what you're trying to do.

It was so effective that nobody talks about it as "AI." It's just... how good software works now.

Why "Softer Software" Beat "Artificial Intelligence"

Here's a question worth asking: why did Gates and Simonyi deliberately avoid calling their innovation "artificial intelligence"?

It wasn't cowardice or a PR stunt. It was intellectual honesty. They understood that the term "AI" had become so loaded with philosophical expectations, sci-fi imagery, and impossible promises that it actually prevented people from understanding what was actually possible.

The academic AI research community was pursuing "general artificial intelligence"—machines that could think like humans. That was the grand goal. But that goal was decades away (and arguably still is). Meanwhile, real problems needed solving right now.

Fawcette captured the problem perfectly in his 1985 editorial: "The term itself obstructs practical work." People heard "artificial intelligence" and thought of either:

- Science fiction nightmare scenarios (killer robots, Big Brother)

- Magic silver-bullet solutions that could automate your entire business

Neither of those helped anyone understand what software could actually do to improve their work experience.

So what did Gates and Simonyi call their vision instead? "Softer software." Less grandiose. More honest about limitations. More focused on the actual user benefit.

The name itself was the innovation. By stepping away from AI terminology, they made the concept accessible and practical. And that accessibility is why their ideas actually got implemented, while purely "AI" research mostly stayed in academia.

There's a lesson here for anyone building technology: naming and framing matter enormously. The right name helps people understand what something actually does. The wrong name—no matter how impressive it sounds—confuses people and sets false expectations.

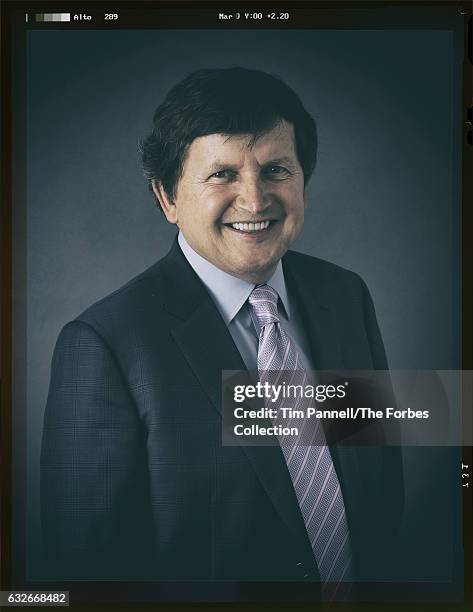

The Oracle Exception: When Skepticism Got It Right

Not everyone in the 1980s bought into the AI hype, even in its softer form. Larry Ellison, the founder of Oracle, made the contrarian argument in 1987 that not everything should be AI.

Ellison wasn't saying AI was impossible. He was saying it was being over-applied. Not every problem needs machine learning. Not every system needs to be adaptive. Sometimes a simple, straightforward tool is the right answer.

He was right then. He's still right now.

In 2025, we're seeing the same pattern again. Every software company is scrambling to add AI features. Some of those features are genuinely useful. Many are just elaborate ways to solve problems that simpler tools could handle. The spray-and-pray approach to AI implementation is racking up a lot of waste.

The interesting thing is that Gates and Simonyi weren't pushing blind AI evangelism either. Their vision of "softer software" was fundamentally about constraint and practicality. Learn from user behavior. Adapt incrementally. Solve real problems. It wasn't hype. It was engineering philosophy.

Ellison's skepticism wasn't anti-AI. It was pro-pragmatism. And that pragmatism is what actually separated the useful innovations from the vaporware in both the 1980s and now.

The AI hype cycle shows recurring peaks and troughs from 1985 to 2025, with hype often outpacing practical applications. Estimated data.

Why the Industry Ignored the 1983 Vision for 40 Years

If the softer software vision was so good, why didn't the entire industry immediately adopt it?

Three reasons.

First, the computing infrastructure wasn't there. Building truly adaptive systems requires data, processing power, and sophisticated algorithms. In 1983, you had none of those things. Computers were thousands of times slower. Storage cost thousands of times more. The vision was right, but the foundation didn't exist yet.

Second, the hype cycle was more profitable than pragmatism. If you're a software company trying to raise venture capital, saying "we're going to make our products incrementally more responsive to user behavior over many years" doesn't sound as exciting as "we're building artificial intelligence that will revolutionize everything." The venture capital and media attention goes to the bold promises, not the steady improvements.

Third, the academic side of AI split off from the practical side. University AI research programs pursued theoretical goals (general intelligence, reasoning, consciousness) while software engineers focused on building useful products. These two communities didn't really talk to each other. The academics didn't think the engineers' work was "real AI." The engineers weren't interested in unsolved philosophical problems.

This split meant that the practical vision of adaptive, learning software got lost in the noise of overhyped academic research.

But here's what's interesting: the practical vision just kept quietly winning. Every major software company eventually discovered the Simonyi principle—adapt to users, learn from behavior, make the tool smarter over time—because it actually works. It just didn't get branded as "AI" in the 1980s and 1990s. It was just... good software design.

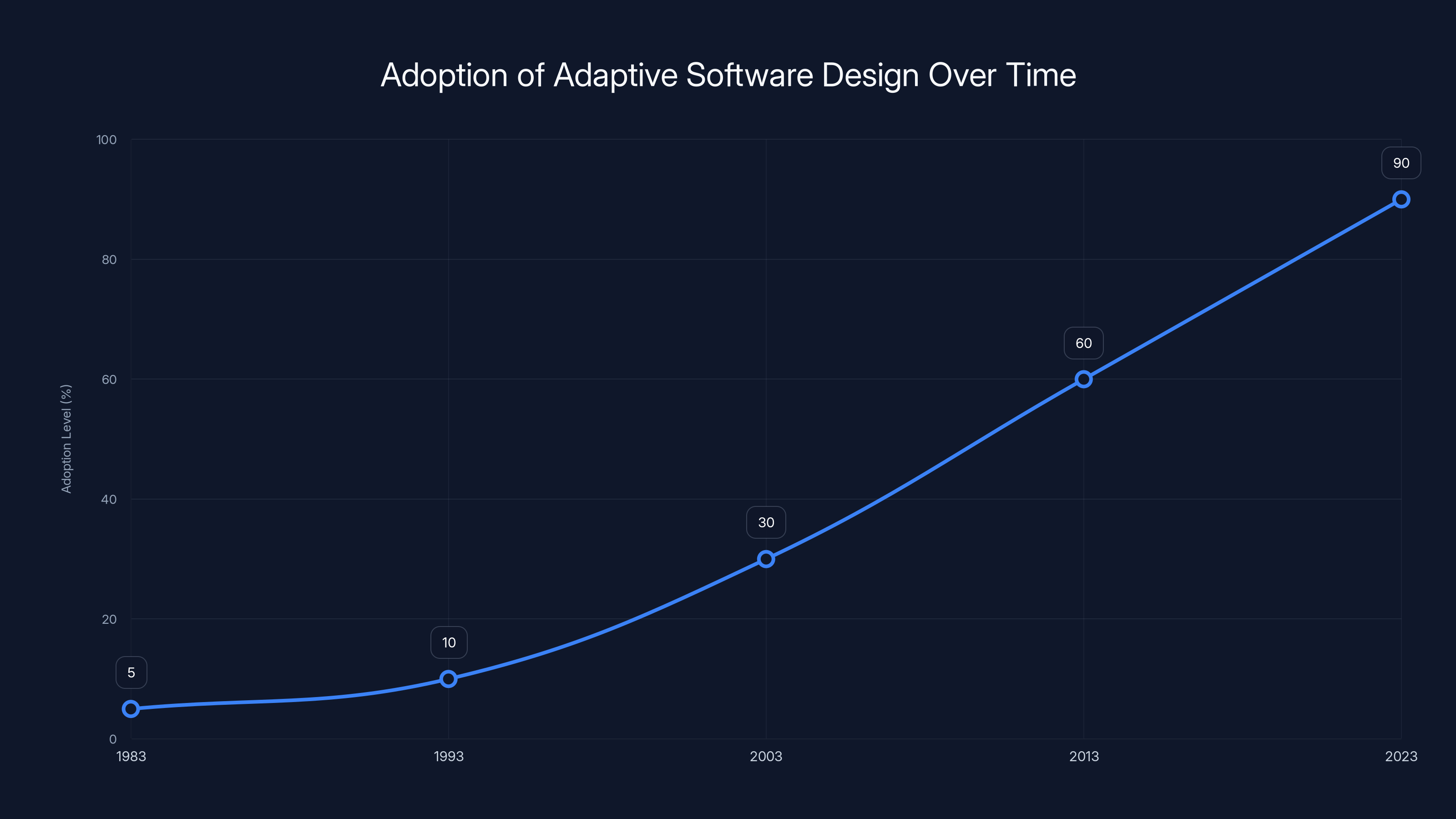

The Personalization Engine Era: Softer Software Gets Real

Sometime in the 2010s, the conditions finally aligned for the softer software vision to come true at scale.

First, the technology got there. Cloud computing gave us the processing power and storage. Machine learning algorithms matured. We had datasets so large they'd have been unimaginable in 1983. The infrastructure finally existed.

Second, mobile and web applications created a new context where adaptation was obviously useful. Your phone knows your location, your contacts, your calendar. It can predict what you need with remarkable accuracy. It learns from every interaction. It's softer software, even if nobody calls it that.

Third, companies figured out that personalization actually increases engagement and revenue. Netflix recommends shows. Amazon recommends products. Spotify recommends music. These aren't AI in the philosophical sense. They're softer software—systems that learn your patterns and adapt their behavior to match your preferences.

And they work. They massively increase user engagement and retention. Suddenly the Simonyi vision wasn't just nice to have. It was essential to being competitive.

The interesting part is that none of this required "true" artificial intelligence. It required statistical pattern matching, A/B testing, and incremental optimization. Exactly what Simonyi described in 1983.

Modern AI Assistants: The Full Realization

When Open AI released Chat GPT in late 2022, people acted like something completely new had appeared. And in a way, they were right—the scale and capability of large language models was genuinely novel.

But here's the thing: Chat GPT and the modern AI copilots that followed are just the ultimate expression of the softer software vision.

They learn from user input. They adapt their responses based on context and conversation history. They anticipate what you're trying to accomplish and suggest the next step. They mold themselves based on how you interact with them. They're a "working partner in the sense of anticipating your behavior and suggesting things to you."

Simonyi's words, exactly.

The difference is that instead of learning your spreadsheet preferences or document formatting habits, modern AI assistants learn language patterns and can reason across domains. But the fundamental principle is identical. Software that learns. Software that adapts. Software that gets better because it understands how you work.

The hype around modern AI obscures this continuity. People talk about Chat GPT like it's the arrival of thinking machines. Some of that is justified—the capability jump was real. But the core insight goes back to 1983. The Simonyi principle. The softer software vision.

The adoption of adaptive software design principles has steadily increased over the past 40 years, reaching widespread use by 2023. (Estimated data)

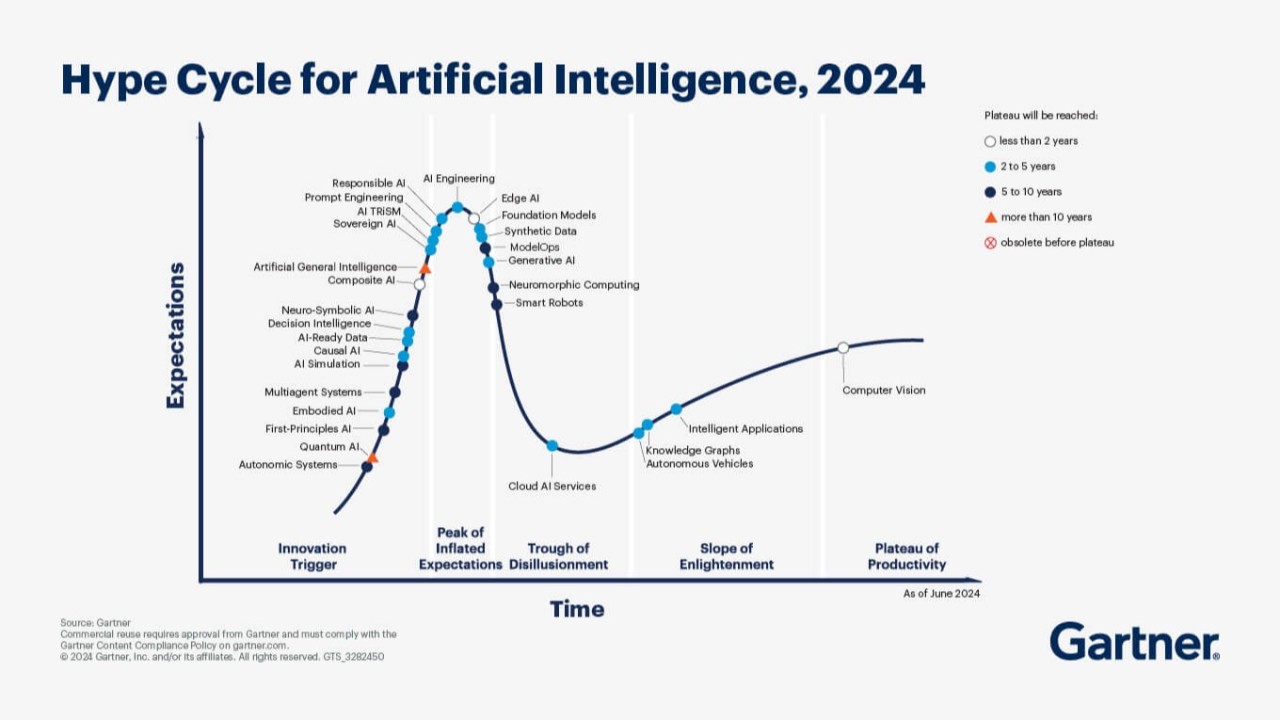

The 2023 Generative AI Boom: Hype vs. Reality

Now we're in another hype cycle. It's 2025, and people are predicting that AI will automate entire industries, replace most white-collar workers, and possibly kill us all. Some of that might be true. But a lot of it sounds exactly like the 1985 predictions that never came true.

Fawcette's warning still applies: "The problem is: What can AI really do?"

Here's what we've learned:

What AI actually does well: Pattern recognition across massive datasets. Writing and editing text. Generating images from descriptions. Finding anomalies in data. Making predictions based on historical patterns. Answering questions. Explaining concepts.

What AI still struggles with: Novel creative thinking. Reasoning through truly complex problems. Handling context that requires deep real-world knowledge. Making ethical judgments. Knowing what it doesn't know. Adapting to genuinely new situations.

So the reality is somewhere in the middle. AI is genuinely useful for a lot of tasks, but it's not the universal solution that hype suggests. Which is exactly what Simonyi understood in 1983: different tools for different jobs, and the real win is making them adapt to how humans actually work.

The companies that are going to win with AI aren't the ones that make the biggest promises. They're the ones that identify genuine use cases, implement solutions thoughtfully, and iterate based on real user feedback. That's the softer software principle applied to modern AI.

How the 1983 Vision Shapes 2025 Development

You might think that Gates and Simonyi's ideas are just historical artifacts—interesting for context but not relevant to how software gets built today.

You'd be wrong.

The principles of softer software are everywhere in modern product design:

Adaptive interfaces: Software that rearranges itself based on how you use it. Google Docs learns what formatting you prefer and highlights it. Figma's tools change based on what you're designing. This is direct softer software.

Contextual assistance: Instead of flooding you with options, modern software suggests the feature you probably need right now. That's learning your behavior. That's adaptation.

Incremental automation: The best automation isn't replacing human work—it's removing friction from routine tasks. You still make decisions. The software just learns what decisions you consistently make and offers to do them for you. Softer software principle.

Personalized recommendations: Every major platform uses this. Netflix learns what shows you like. You Tube learns what videos engage you. Linked In learns what content you interact with. Pure softer software.

Predictive text and code completion: Your phone predicts your next word. Git Hub Copilot predicts your next line of code. Both are learning your patterns. Both are softer software.

The vision didn't just survive. It became the dominant paradigm in software design.

The Hype-Reality Gap: Then and Now

Let's be specific about how the 1980s hype loop matches the 2023-2025 hype loop:

Then (1985): "AI will revolutionize software. Every company will use it. It will solve impossible problems. Competitors who don't invest in AI will fall behind."

Now (2023-2025): "Generative AI will revolutionize software. Every company will use it. It will solve impossible problems. Competitors who don't invest in AI will fall behind."

They're not just similar. They're identical. Which suggests the pattern is structural, not accidental. Every time a new powerful technology emerges, the same hype machine activates. Same promises. Same fears. Same boom-bust cycle.

What's different this time is the technology is actually more capable. But that doesn't change the fact that a lot of the hype will turn out to be overblown, and the real value will come from the boring, practical applications that nobody's shouting about.

Fawcette's advice still applies: identify what software can actually do for real users doing real work. Strip away the philosophy and the grand promises. Focus on practical benefit. That's where the sustainable competitive advantage is.

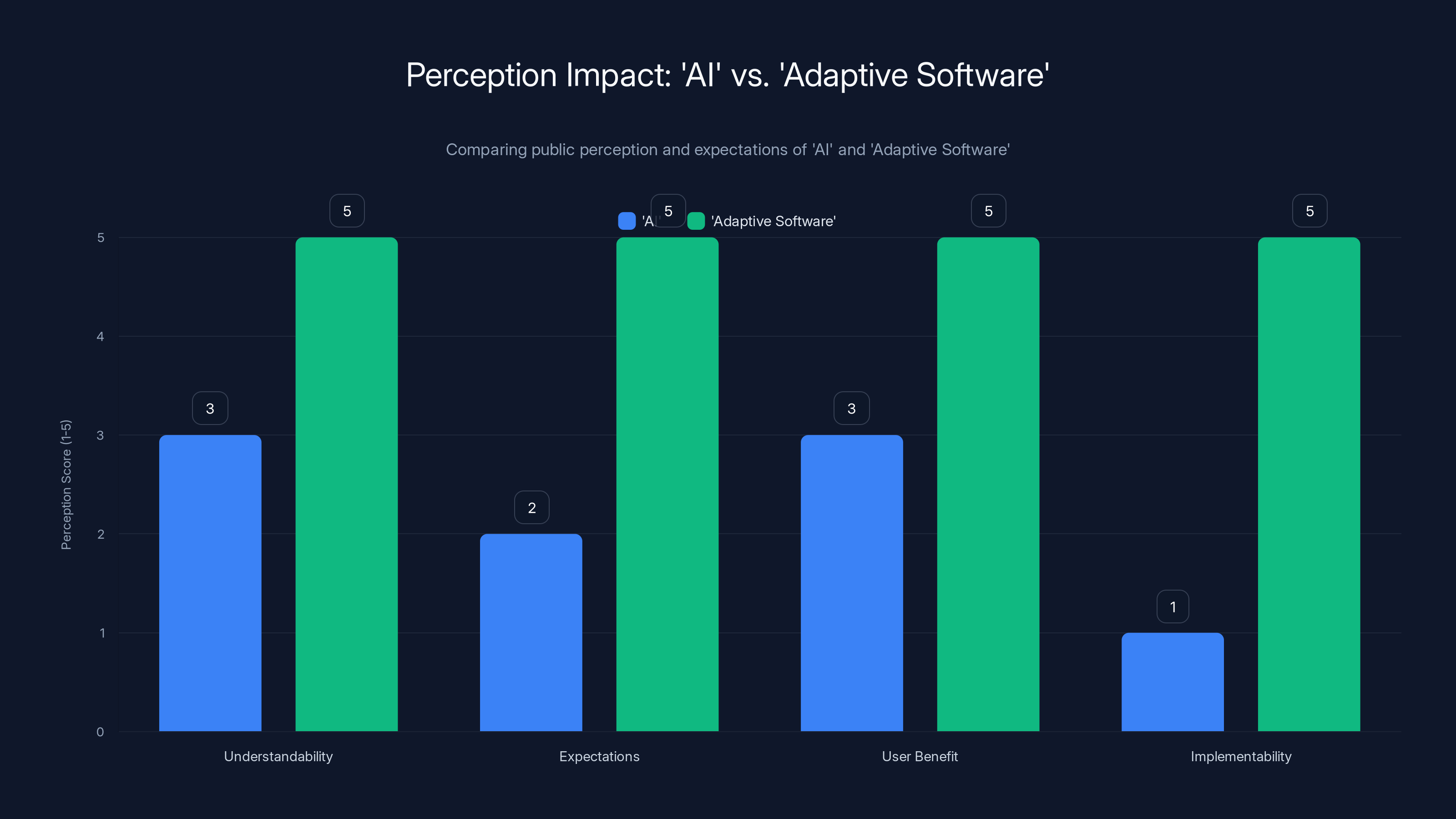

The term 'Adaptive Software' scores higher across all factors compared to 'AI', suggesting it is more understandable, sets realistic expectations, emphasizes user benefits, and is more implementable. Estimated data.

Why Naming Matters: "AI" vs. "Adaptive Software"

Here's something that still fascinates me about the Simonyi approach: he won the naming battle by refusing to call it what everyone else was calling it.

By calling it "softer software" instead of "artificial intelligence," Simonyi accomplished several things:

-

He made it understandable. People could grasp what "software that adapts to users" means. "Artificial intelligence" requires philosophical clarification.

-

He set realistic expectations. "Softer" implies gradual, incremental improvement. "Intelligence" implies consciousness and reasoning. Totally different mental models.

-

He focused on benefit, not capability. The name emphasizes what the software does for the user (adapts, learns, helps), not what philosophical property it has.

-

He made it implementable. You could start building softer software in 1983. You couldn't build "artificial intelligence" in 1983, no matter how hard you tried.

In 2025, we're seeing the exact opposite dynamic. Every software company is trying to put "AI" on everything because the term has become synonymous with "advanced" and "future-proof." It's great marketing but terrible for clarity.

Where's the Simonyi of 2025? Where's someone going to say, "We're not building 'AI'—we're building software that learns from your behavior, anticipates your needs, and adapts to how you work." Clear. Honest. Practical.

That person will probably win, because honest framing about what software can actually do will eventually beat inflated claims.

Building Softer Software in 2025: Practical Principles

If you're building software in 2025, here's how the softer software principle translates to practice:

Start with observation, not imagination. Study how users actually work. What patterns do they exhibit? Where do they get stuck? Where do they make repeated decisions? Simonyi always started with user observation.

Make incremental adaptation visible. Don't secretly change how the software works. Let users see that the software is learning their preferences. Build trust through transparency.

Prioritize one area of learning, not omniscience. Your software doesn't need to be smart about everything. Pick one specific way it can learn user behavior and do that well. The expert systems approach: narrow domain, deep utility.

Test empirically, not philosophically. Does the adaptation actually help users? Do they feel the software is getting smarter, or does it feel creepy? Measure real outcomes, not theoretical AI capability.

Respect user agency. Softer software suggests and learns. It doesn't override. The user is always in control. That's what makes it "softer"—it responds to the user's direction.

Plan for long-term evolution. The magic of softer software is that it gets better over years, not days. You can't make a great adaptive system in a MVP. You need to think in terms of continuous learning and improvement.

These principles work for any software team. You don't need cutting-edge AI research. You need discipline, user focus, and the willingness to iterate slowly toward elegance.

What Fawcette Got Right: The Timeless Warning

Before we wrap up, let's acknowledge James Fawcette's 1985 editorial was genuinely insightful. His core warning was: the term "artificial intelligence" obstructs practical work. Look for software that solves real problems, not software that promises to be intelligent.

40 years later, that warning is more relevant than ever.

In 2025, we have companies building:

- AI-powered dashboards that don't actually provide actionable insights

- Chatbots trained on your company data that hallucinate confidently

- "Predictive" tools that are just running the same algorithms on old assumptions

- Automation systems that break the moment real-world conditions change

All of these sound impressive. All of them promise that AI will solve your problems. Most of them are Rube Goldberg overdesigns that fail at basic utility.

Fawcette's solution still works: ask what the software actually does for your people. Not what it claims to be. Not what it promises. What does it actually do? Is it clearer than the alternative? Faster? More reliable? Does it make work easier?

If yes, it's good software. Call it AI or softer software or whatever. The name doesn't matter. The utility does.

The Future of Adaptive Software: What's Next

So what's the next evolution beyond where we are now?

I think we're going to see a bifurcation. On one side, companies will keep chasing increasingly capable AI models, bigger datasets, more computational power. The capabilities will keep growing. Some amazing things will happen. Some terrible things will happen.

On the other side, companies will realize that the real value comes from deep domain expertise, thoughtful design, and software that actually understands the user's specific context. You don't need GPT-10 to make accounting software dramatically better. You need to understand accounting deeply and build software that learns how your company actually does accounting.

The softer software principle survives and thrives in that second category. It's not about raw capability. It's about understanding users and designing systems that evolve with them.

The winners will be the companies that marry those two approaches: modern AI capability applied with the discipline and pragmatism of the softer software philosophy.

Simonyi would approve.

FAQ

What was "softer software"?

Softer software was Charles Simonyi's 1983 concept for programs that modify their behavior based on experience with users, learning preferences and patterns over time to become more useful and adaptive without requiring explicit "artificial intelligence." The term was intentionally chosen to avoid the philosophical baggage and unrealistic expectations that came with "AI" terminology.

How does softer software differ from artificial intelligence?

Softer software focuses on practical learning and adaptation to user behavior through observation and pattern recognition, while "artificial intelligence" implies philosophical properties like consciousness or reasoning. Softer software is measurable and implementable, while AI in the philosophical sense remained more theoretical. Modern AI assistants actually implement the softer software principle at scale through large language models and personalization systems.

Why did Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi avoid using the term "AI" in 1983?

Simonyi believed the term "AI" had become so loaded with philosophical expectations and sci-fi imagery that it obstructed practical software development. By coining "softer software," they created a clearer, more honest framework for describing programs that learn user patterns without claiming to achieve general intelligence or consciousness.

What were Microsoft's expert systems, and how did they apply softer software?

Microsoft's expert systems were early implementations of the softer software principle, designed to improve Multiplan spreadsheet functionality by helping users build formulas, create charts, and discover functions based on observed work patterns. Instead of presenting users with blank cells, the systems learned what they typically did and suggested relevant features—making complex software more accessible and intuitive.

How does modern software embody the softer software principle?

Today's adaptive interfaces, personalized recommendations, contextual assistance, and learning algorithms all reflect the softer software principle. Netflix learning your viewing preferences, Word suggesting formatting based on patterns, and Git Hub Copilot predicting code are all examples of software that learns behavior and adapts, exactly as Simonyi envisioned in 1983.

What does the 1985 AI hype cycle tell us about current generative AI trends?

The warnings from Info World's 1985 editorial about AI overhype—companies using "AI" as marketing language without delivering real value, overly complex systems solving abstract problems rather than user needs—apply almost identically to 2023-2025 generative AI claims. The pattern suggests that while the technology is more capable, much of the hype will again prove overblown, and sustainable value will come from practical applications rather than grand promises.

What principles should guide building modern adaptive software?

Start with observing actual user behavior rather than imagining what software could do, make adaptation visible and transparent to build trust, focus on learning one specific behavior pattern deeply, test empirically against user outcomes rather than theoretical capability, respect user agency by suggesting rather than overriding decisions, and plan for long-term evolution rather than trying to build the perfect system immediately.

Why did Larry Ellison's skepticism about AI in 1987 matter?

Ellison's argument that not every problem needs AI was a pragmatic counterpoint to hype. His skepticism wasn't anti-technology but pro-pragmatism—recognizing that different problems need different tools, and forcing AI onto every problem wastes resources and creates unreliable systems. That principle remains true in 2025.

How would the softer software approach handle modern generative AI?

Applying softer software principles to modern AI means using these powerful models where they genuinely solve user problems, implementing them with clear expectations and measurable outcomes, allowing the systems to learn from user interaction and feedback, being transparent about limitations, and maintaining user control over system behavior. It's about wielding AI capability with the discipline and pragmatism Simonyi advocated, avoiding the grand promises that Fawcette warned against in 1985.

Final Thoughts: Why 1983 Still Matters

It's tempting to dismiss the past as quaint. "Look how slow those computers were. Look how limited the data. Look how naive they were about what machines could do."

But Gates and Simonyi didn't get the technical details wrong. They got the human details right. They understood that the most powerful software isn't the most theoretically sophisticated. It's the software that carefully observes how people actually work and designs itself around that reality.

That insight doesn't age. If anything, it gets more valuable as technology gets more complex. When everything is smart, the differentiator is thoughtfulness. When every company has access to the same AI models, the differentiator is knowing how to apply them wisely.

So maybe in 2045, some new technology will emerge and the cycle will repeat. The hype will inflate. The warnings will go unheeded. And some quiet pragmatist will propose a new name for a better way of thinking about it.

But underneath, the softer software principle will still be there. Learning from users. Adapting to their needs. Getting better over time. Making work easier without making promises it can't keep.

That's not quaint. That's timeless.

Use Case: Document adaptive learning—create presentations and reports that learn from your input patterns and suggest content structure automatically.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- Bill Gates and Charles Simonyi proposed 'softer software' in 1983—adaptive programs that learn user behavior—which perfectly describes modern AI assistants 40+ years before the technology matured

- They deliberately avoided calling it 'AI' because the term was loaded with unrealistic expectations and philosophical baggage that obscured practical problem-solving

- The same AI hype-reality gap that existed in 1985 is nearly identical to 2023-2025, suggesting the pattern is structural and the real value comes from unglamorous practical applications

- Modern personalization engines (Netflix, Spotify, Amazon), adaptive interfaces (Excel, Word), and AI assistants all implement Simonyi's softer software principle at scale

- Companies winning in 2025 focus on observable user problems and incremental adaptation, not grand promises about artificial intelligence capabilities

Related Articles

- How Spotify's Top Developers Stopped Coding: The AI Revolution [2025]

- Airbnb's AI Search Revolution: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Why OpenAI Retired GPT-4o: What It Means for Users [2025]

- ChatGPT-4o Shutdown: Why Users Are Grieving the Model Switch to GPT-5 [2025]

- 7 Biggest Tech News Stories This Week: Claude Crushes ChatGPT, Galaxy S26 Teasers [2025]

- AI Video Generation Without Degradation: How Error Recycling Fixes Drift [2025]

![How Bill Gates Predicted Adaptive AI in 1983 [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-bill-gates-predicted-adaptive-ai-in-1983-2025/image-1-1771137325687.jpg)