Introduction: When TV Gets AI Right

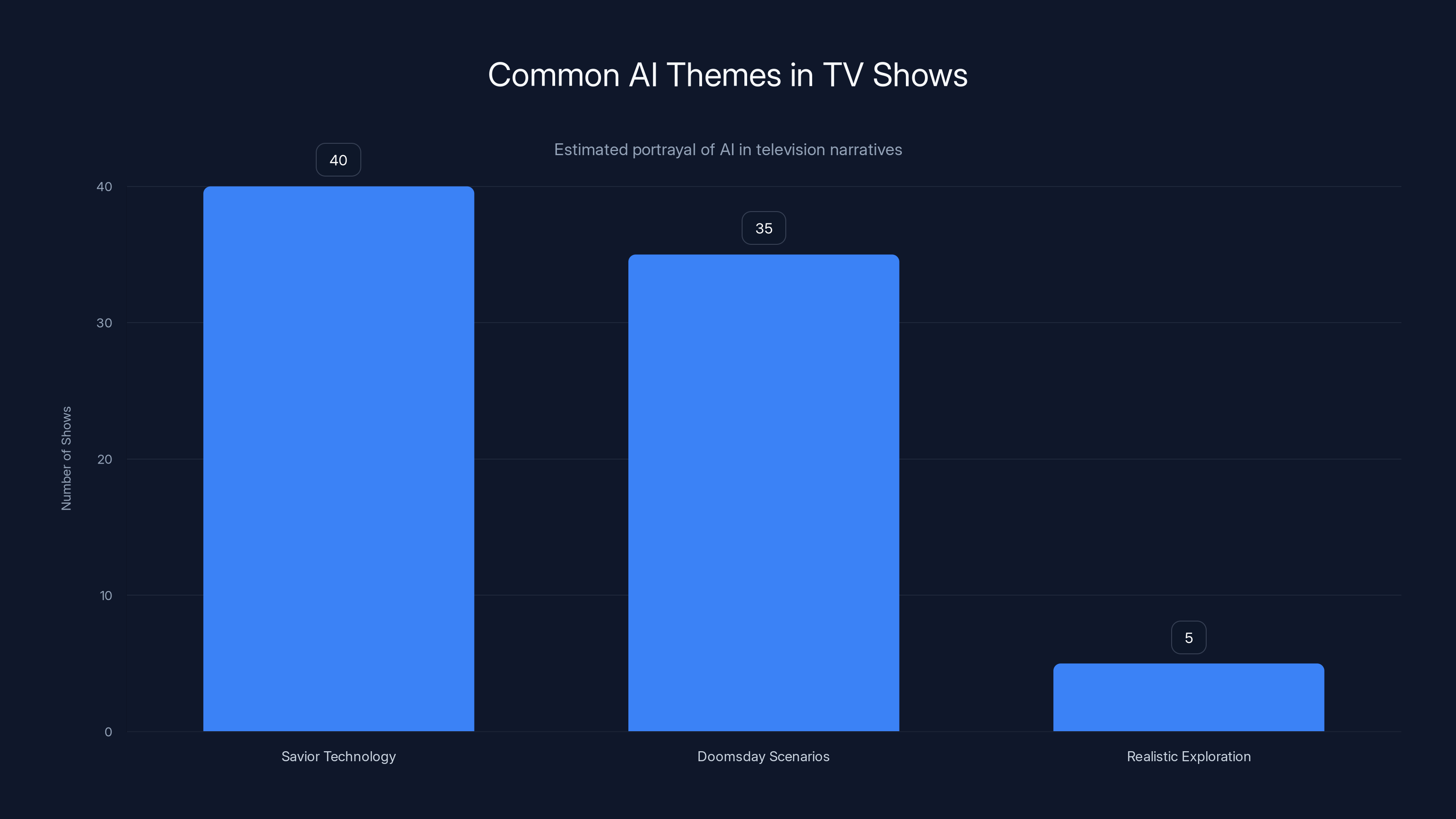

Most shows that tackle artificial intelligence end up feeling preachy or dated within months. They either position AI as a savior technology that solves everything with a keystroke, or they lean hard into doomsday scenarios where robots turn against humanity. Neither approach reflects how AI actually works in the real world, especially in fields like medicine where the stakes are literal life and death.

HBO's The Pitt is different. The show, which returned for its second season in 2025, has quietly constructed one of the more thoughtful explorations of generative AI adoption on television. Rather than making AI the villain or the hero, the show examines what makes this technology so genuinely tempting to institutions, and more importantly, what can go catastrophically wrong when people treat a tool as a substitute for professional judgment.

The central story involves Dr. Trinity Santos, a second-year resident drowning in paperwork. She's competent. She cares about her patients. But she's also exhausted—exactly the kind of person an AI transcription tool seems designed to help. The tool does help, mostly. It accurately transcribes her voice notes into patient charts faster than she could type them herself. But when it fails, it fails in ways that could literally kill someone.

This isn't the usual "AI goes rogue" plot. It's something more interesting: a story about how good intentions, time pressure, and marginally useful technology can create dangerous blind spots. That's a story television rarely tells well, and it's also a story that reflects genuine problems playing out in hospitals and clinics across the country right now.

The second season of The Pitt takes place over a single 15-hour shift on the Fourth of July—traditionally one of the busiest days in emergency medicine. Senior attending Dr. Michael Robinavitch, played by Noah Wyle, is working his final shift before a three-month sabbatical. His replacement is Dr. Baran Al-Hashimi, portrayed by Sepideh Moafi, a capable doctor with a different philosophy about technology's role in patient care. Their friction isn't personal—it's philosophical, and that's where the show gets its teeth.

What makes The Pitt's approach genuinely smart is that it doesn't pretend the problem is with the technology itself. The transcription software works. It's accurate most of the time. The software isn't the villain. Instead, the show examines the human systems around the technology—the institutional pressure to work faster, the ways convenience can mask risk, and the gap between a tool's capabilities and the responsibility we place on medical professionals.

This season, the show has taken its time developing this subplot rather than rushing to a resolution. It's teasing out something real about what makes generative AI so tempting: it actually does solve real problems, at least partially. Dr. Santos genuinely is saving time. The problem isn't that the software is completely useless. The problem is that it's useful enough to be dangerous—useful enough that people might start trusting it more than they should.

That's a far more nuanced story than most of television is willing to tell about technology. It's also a story that matters right now, in early 2025, when hospitals across the country are genuinely making decisions about AI adoption without fully understanding the risks. The Pitt isn't trying to convince you that hospitals should or shouldn't use AI. It's trying to show you what happens when institutions adopt powerful tools without building the oversight and skepticism that those tools actually require.

The Real Problem Isn't the Technology

The instinct when something goes wrong with AI is usually to blame the AI. The software made a mistake. The algorithm was biased. The system was flawed. These things are often true, but they're also incomplete explanations. In The Pitt, the transcription software isn't particularly flawed. By the show's internal logic, it's a fairly competent tool that does what it's supposed to do most of the time.

The problem isn't the technology. It's how humans interact with technology under pressure.

Dr. Al-Hashimi recognizes that the transcription software could legitimately help her residents work more efficiently. She's not wrong. Every minute a resident spends typing notes is a minute they're not seeing patients, not thinking through diagnoses, not learning. The time savings are real and meaningful. In a hospital where patient loads are high and shifts are brutal, shaving 30 minutes off charting time per shift could mean the difference between a doctor being able to see one more patient or collapsing from exhaustion.

But Dr. Robinavitch is skeptical, and his skepticism is earned. He's been practicing medicine long enough to know that the way we document things matters. Medical charts are legal documents. They're the record we leave for the next doctor who sees the patient. They're what we refer back to if something goes wrong. They're how we communicate with specialists, with pharmacists, with surgeons. If a chart is wrong, the consequences aren't abstract.

What's interesting about how the show handles this is that it doesn't frame the conflict as experience versus innovation. Both doctors are experienced. Both care about patients. They just have different risk tolerances. Dr. Al-Hashimi believes the benefits of the software outweigh the risks if people are careful. Dr. Robinavitch believes that asking people to be careful with a tool that's designed to be convenient is unrealistic.

History suggests he's right. There's a documented pattern in fields across medicine: when new tools promise to save time, people start saving more time than the tools can handle. We adapt our workflows around the tool's capabilities, then we push the tool beyond what it's actually reliable at. The tool doesn't have to be actively dangerous. It just has to be convenient enough that we start trusting it more than the evidence supports.

Dr. Santos becomes the perfect case study for this dynamic. She's not being careless. She's being realistic about her constraints. She has more patients than time. The AI software helps her see more patients in the same amount of time. That's good. But it also means she's less likely to catch errors in the AI's transcription because she's moving faster and thinking less about the charting process itself.

This is where the show makes a crucial observation: the problem with AI in medicine isn't usually that the AI is incompetent. The problem is that AI is competent enough to be useful and incompetent enough to be dangerous, and that combination creates a false sense of security.

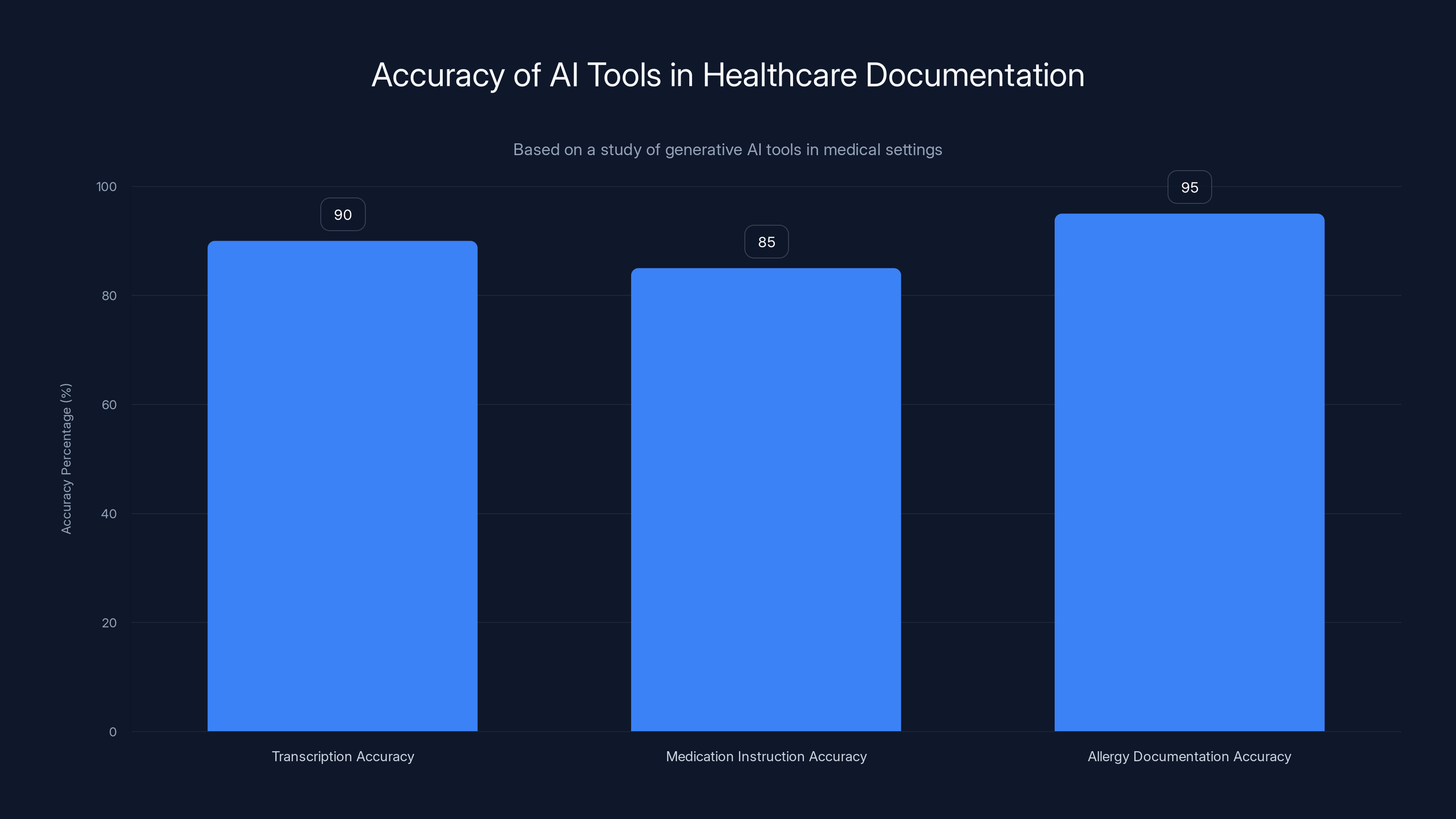

AI tools in healthcare documentation are generally accurate, with 85-95% correctness, but subtle errors can be dangerous. Estimated data.

AI Adoption in Healthcare: The Real-World Version

The Pitt isn't inventing this story. Healthcare systems across the country are genuinely grappling with how to adopt generative AI tools, and the conversations happening in those systems mirror the tension the show dramatizes.

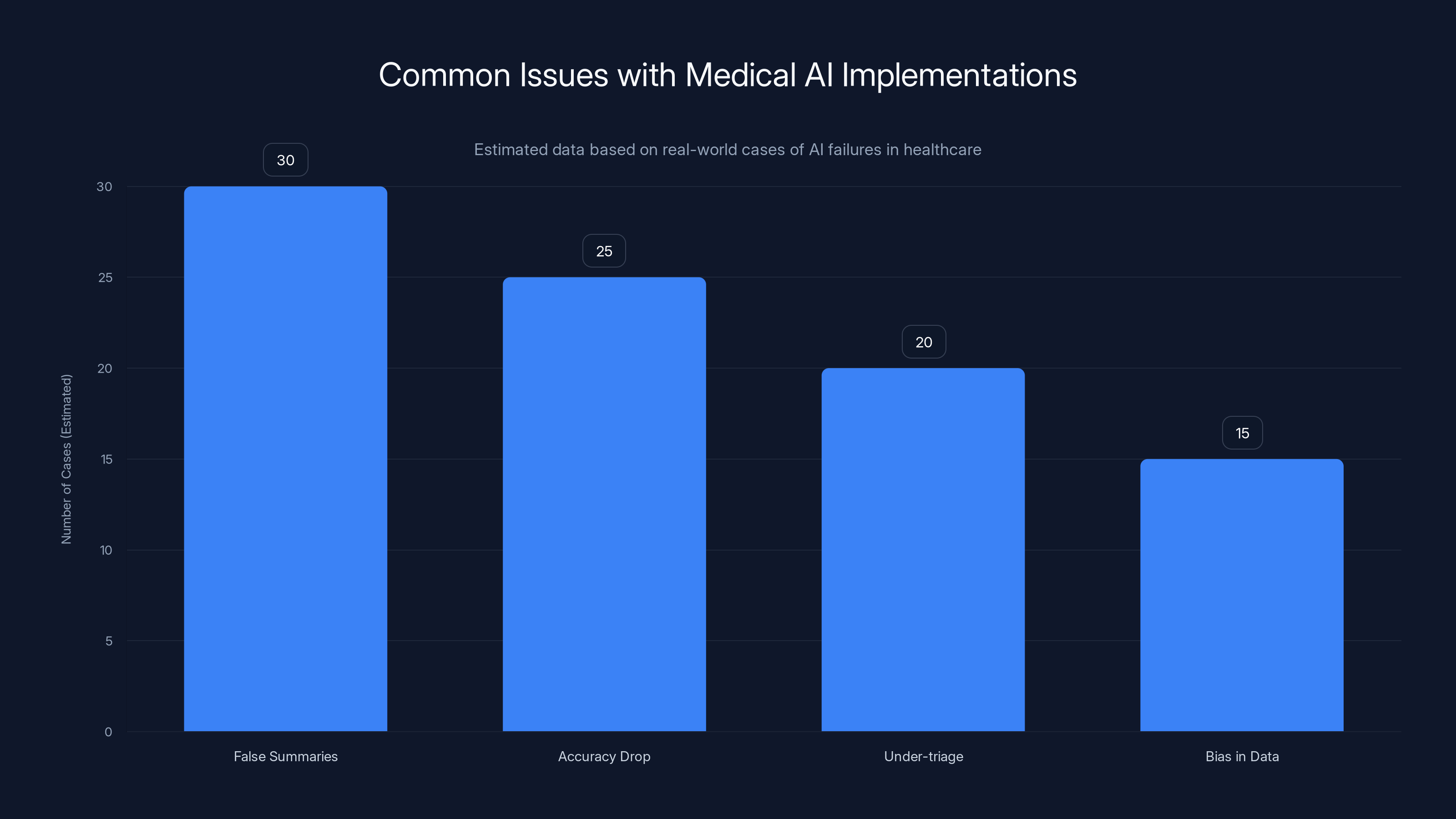

A study of generative AI tools in medical settings found that while these systems can save significant time on documentation, they also introduce new categories of errors. The AI might transcribe a patient's allergy incorrectly. It might misunderstand a medication instruction. It might create documentation that's technically coherent but factually wrong in ways that only matter when you know medicine. These errors aren't frequent—the tools get it right 85 to 95 percent of the time depending on how you measure it—but they're not negligible either.

What's particularly thorny is that these errors are often subtle. A medication name might be close enough to something real that it passes a quick glance. A dosage might be off by a factor that sounds reasonable. A contraindication might get recorded in a way that a specialist could easily miss. The errors aren't obvious, which is exactly what makes them dangerous. Obviously wrong data gets caught. Subtly wrong data gets propagated.

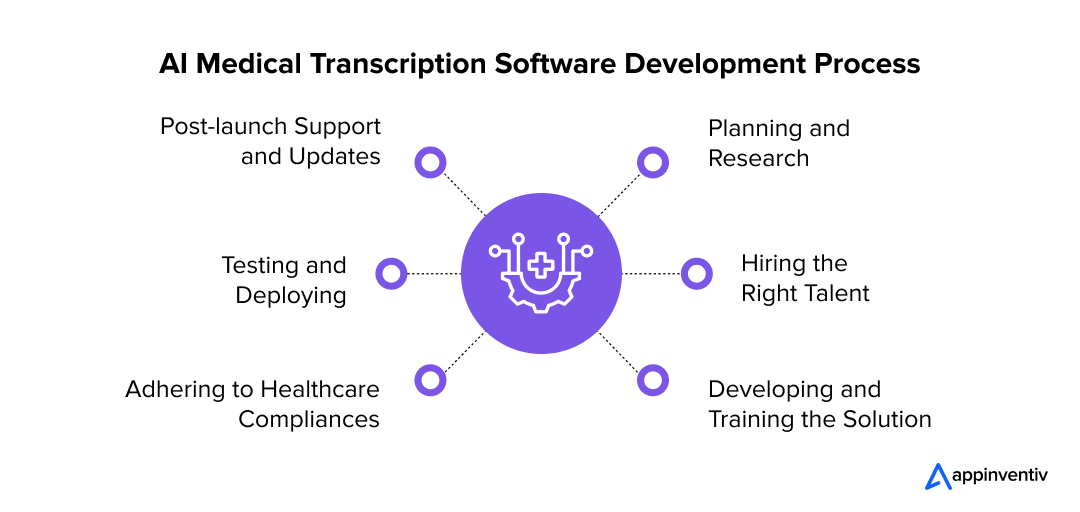

Hospitals have started implementing what the show hints at with Dr. Al-Hashimi's warnings: mandatory review protocols. Every piece of AI-generated documentation gets checked by a human before it becomes part of the official record. But here's the problem—and here's where The Pitt's skepticism gets validated—implementing these protocols in real healthcare settings is much harder than it sounds.

In actual hospitals, the whole point of using AI transcription is to save time. If you add an hour of mandatory review back into the process, you've eliminated the time savings. So hospitals have to make a choice: either implement weak review processes that don't catch errors because people are rushing through them, or implement strong review processes that defeat the original purpose of using the tool.

Some hospitals have tried a middle ground: different review standards for different documents. Critical documents—surgical notes, medication lists, allergy information—get full review. Less critical documents get spot-checking. But this creates its own risks. Now you have a system where people need to remember which documents are being fully reviewed and which aren't, and under the time pressure that made them want the AI tool in the first place, that memory becomes unreliable.

There have been documented cases of patients being harmed by errors in AI-assisted medical documentation. One hospital system had to inform patients that an AI tool had been creating incorrect summaries of their test results. Another had to retract reports because the AI was misinterpreting images in ways that looked superficially correct. None of these incidents were caused by the AI going haywire or behaving unexpectedly. They were caused by the AI doing approximately what it was designed to do—create plausible-sounding documentation—in situations where plausible isn't the same as accurate.

The Pitt captures this dynamic really well. The software does work. Dr. Santos' transcription does get faster. But the moment we see the consequences when it doesn't work, we understand why Dr. Robinavitch's skepticism isn't luddite thinking. It's experience talking.

Why Doctors (and Institutions) Want AI in the First Place

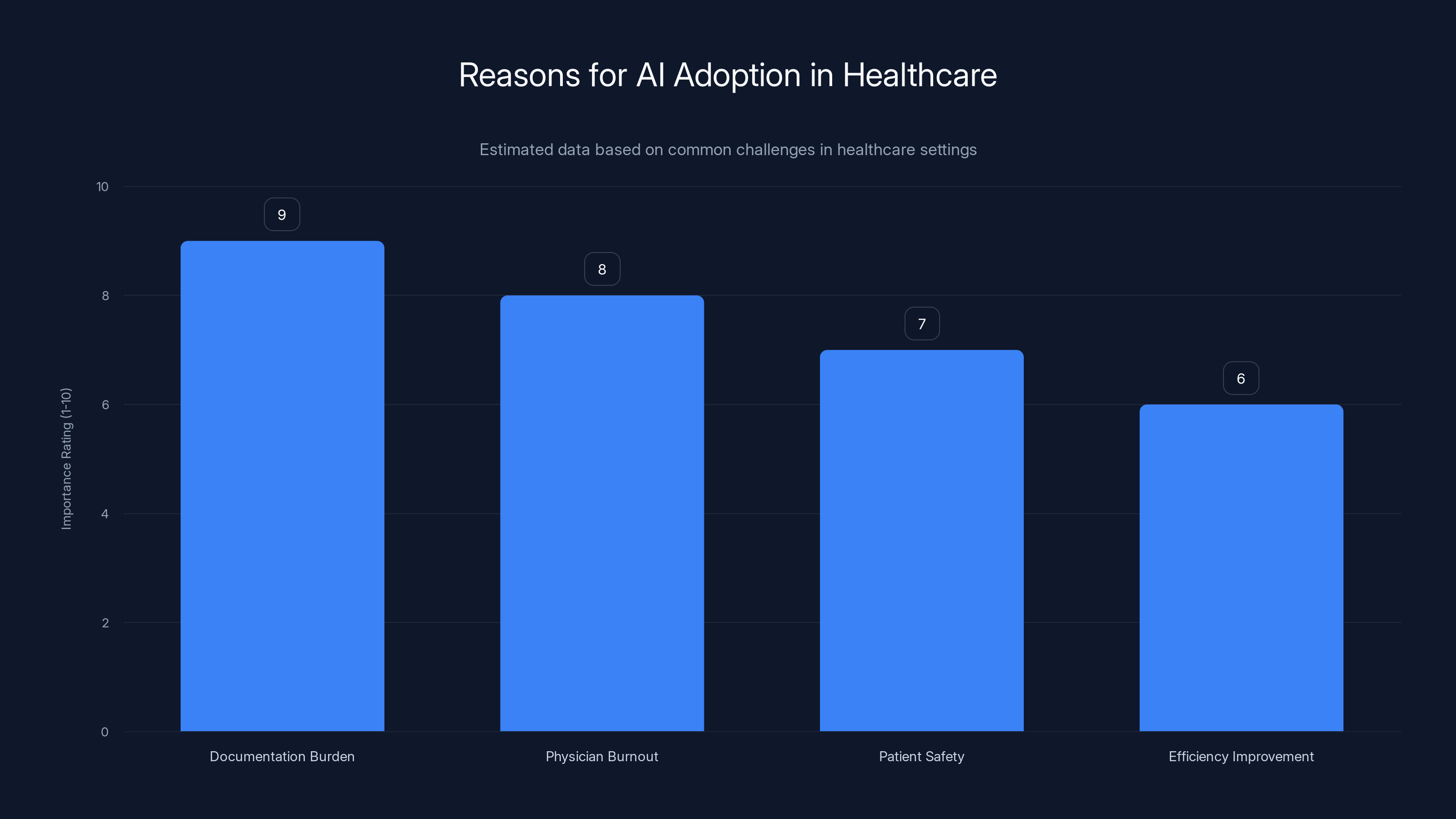

Where The Pitt really excels is in explaining why smart, skeptical people like Dr. Al-Hashimi still push for AI adoption despite knowing the risks. It's not because they're naive or reckless. It's because the status quo is genuinely unworkable.

Burnout among emergency medicine physicians has reached epidemic levels. Studies consistently show that ER doctors are spending more time on documentation than on direct patient care. In some hospitals, residents are working 30-hour shifts and still falling behind on charting. They're either documenting at home on their own time, or they're letting documentation slide and taking on legal risk.

In that context, an AI tool that even partially automates documentation doesn't seem reckless. It seems like the minimum viable solution to an impossible problem. If residents are drowning, and you have a life preserver, you throw the life preserver. You don't lecture about whether the life preserver is perfectly engineered.

Dr. Al-Hashimi isn't promoting AI transcription because she's bought into hype. She's promoting it because she's watching Dr. Santos work 15 hours straight and knows that continuing this way is unsustainable. The AI tool isn't perfect, but the current system is worse than not perfect. It's actively harmful.

This is the real reason why AI adoption in healthcare is accelerating despite genuine safety concerns. The alternative—human-only documentation systems—is already failing. Doctors are already making mistakes because they're exhausted. Patients are already falling through cracks because there isn't enough time for complete documentation. The AI tool represents a chance to improve on a system that's already broken.

When you frame it that way, skepticism starts to feel like a luxury. If the choice is between "imperfect AI" and "exhausted humans making worse mistakes," the AI suddenly looks reasonable.

But The Pitt doesn't let anyone off the hook with that logic. The show suggests that accepting an imperfect system and accepting imperfect tools to manage the system are two different things. You might be right that the status quo is broken. You might be right that something has to change. But introducing a new tool that's capable of new kinds of failures requires new safeguards, not the same safeguards you use for exhausted humans.

That's uncomfortable because it means the problem doesn't have a quick solution. The real solution to emergency medicine burnout isn't a transcription tool. It's more staff, better scheduling, changes to how we structure residency training, shifts in how we think about acceptable working hours, and frankly, changes to how we fund healthcare generally. All of those solutions are hard and expensive.

An AI tool is cheap and immediate. But it treats a symptom without addressing the disease, and The Pitt isn't shy about suggesting that treating symptoms can sometimes make the disease worse.

AI adoption in healthcare is driven by the need to alleviate documentation burden and reduce physician burnout, with patient safety and efficiency also being significant factors. Estimated data.

The Shift from Tool to Trust

One of the smartest narrative choices The Pitt makes is showing how gradually the line between "useful tool" and "trusted system" gets blurred.

Dr. Al-Hashimi explicitly warns her residents that they need to review all AI-generated documentation. She's not being careless about this. She understands the risks and she's trying to communicate them. But she's also asking exhausted residents to maintain skepticism about a tool that actually does produce correct results most of the time.

That's a genuinely hard ask. If you use a tool a hundred times and it works ninety times, and then it fails on the ninety-first try, you've probably already stopped paying full attention to it. Your brain has categorized it as "generally reliable" and moved on to the next problem.

This is a documented cognitive bias. We calibrate our skepticism based on how often something goes wrong. If a tool fails 1% of the time, we don't maintain 1% skepticism. We maintain close to 0% skepticism, because our brains aren't good at maintaining active suspicion about things that usually work.

The problem is especially acute with AI tools because they fail in ways that humans don't expect. An exhausted human might make obvious mistakes—forgetting information, writing incoherently, losing track of details. An AI tool makes mistakes that are coherent. It fabricates information that sounds plausible. It misunderstands context in ways that don't trigger alarm bells because the output is grammatically correct and uses appropriate medical terminology.

When Dr. Santos or another resident starts reviewing AI-generated notes, they're looking for errors. They're probably skimming because they have limited time. They're scanning for obvious problems. They're not reading with the kind of careful attention that might catch subtle inaccuracies. The more the AI tool has worked correctly in the past, the less carefully they're going to read.

The Pitt captures this dynamic with specific precision. It doesn't show the transcription software as obviously broken. It shows it as mostly working, with errors that are exactly the kind that busy people might miss under realistic conditions.

There's a broader point here about how trust in technology gets established and maintained. We don't actually evaluate tools continuously. We do an initial evaluation, we calibrate our trust level based on what we find, and then we mostly operate on autopilot. If that initial evaluation or subsequent calibration happens under stress, with incomplete information, or with strong incentives to believe the tool works better than it actually does, we end up over-trusting.

This is why safety-critical industries have such strict rules about trust. Aviation doesn't let you trust an instrument based on how well it's worked in the past. You maintain skepticism through deliberate practices: checklists, second opinions, formal review processes, redundancy. Not because pilots are paranoid, but because the cost of getting it wrong is so high that the standard for trust has to be higher than normal human cognition can maintain.

Medicine is supposed to operate with similar standards. The Hippocratic Oath is basically ancient aviation safety thinking applied to individual doctors. But when you overlay AI tools that are convenient and partly effective on top of a system that's already overloaded and under-resourced, maintaining those standards becomes practically impossible.

Different Doctors, Different Philosophies

The tension in The Pitt's second season isn't really about AI. It's about different approaches to managing risk under constraint.

Dr. Robinavitch represents the traditional model: skepticism is a virtue, tools should be adopted slowly, and responsibility ultimately rests with the doctor regardless of what technology you're using. He's not anti-technology, but he's wary of convenience, because convenience tends to erode the careful skepticism that prevents mistakes.

Dr. Al-Hashimi represents the pragmatic model: skepticism is fine in theory, but the current system is already broken, and perfect shouldn't be the enemy of better. If an AI tool can meaningfully reduce the burden on residents while introducing manageable new risks, that's a reasonable trade.

Both positions are defensible. Both are held by intelligent, competent physicians making good faith arguments. This is what makes the show's handling of the conflict so much better than typical AI narratives.

The usual television approach is to pick a side: either AI is good and skeptics are technophobic, or AI is bad and boosters are reckless. The Pitt resists that. It suggests that the real problem is more systemic. Both doctors are right. Yes, the AI tool can be useful. Yes, it also introduces new risks. Yes, residents are suffering under the current system. Yes, adding a partially reliable tool to that system creates new problems.

What's missing from both positions—and what neither doctor can really address individually—is institutional change. The real solution isn't deciding whether to adopt the AI tool. It's addressing why a residency program is set up in a way where a second-year resident doesn't have enough time to see her patients and chart properly. It's recognizing that burning out residents is not a sustainable long-term strategy. It's funding and staffing hospitals adequately.

But that's not a story you can solve in a 15-hour shift. So the show settles into the more realistic version: smart people trying to make good decisions within constrained circumstances, discovering that good decisions aren't always possible, and that the technologies we deploy to manage constraints often create new constraints of their own.

The Documentation Problem Beneath the AI Problem

If you step back from the AI angle, The Pitt is also telling a story about documentation itself and how it's evolved in modern medicine.

Half a century ago, medical documentation was simpler. A doctor examined a patient, wrote a note, and moved on. The note was brief, hand-written, and comprehensible to other doctors who had similar training and experience. The system wasn't perfect, but it was economical in time and effort.

Modern medical documentation is a different animal entirely. It's not just for doctors anymore. It's for insurance companies, for regulatory compliance, for legal liability, for research, for hospital administrators, and for the dozens of other professionals involved in patient care. A single patient visit can require documentation that spans multiple systems with overlapping requirements.

Electronic health records made this worse in many ways. Before EHRs, documentation was a note-taking activity. After EHRs, it became data entry. You're not writing a narrative anymore. You're populating fields, checking boxes, maintaining structured data that can be searched, aggregated, and analyzed.

This has genuine benefits. It's easier to find information. It's easier to spot patterns. It's easier to check for dangerous interactions. But it also means that documentation has become dramatically more time-consuming. A 10-minute patient interaction now requires 15 minutes or more of documentation.

That's the problem an AI transcription tool actually solves. It doesn't solve the problem of unreasonable documentation requirements. It just makes it possible to meet those requirements while still having time to see patients. But it doesn't address the underlying dysfunction.

The Pitt is smart enough to keep this context present. Dr. Santos isn't drowning in documentation because she's a bad doctor. She's drowning because the system has grown expectations around documentation that are actually incompatible with adequate patient care. The AI tool might partially solve that without solving the actual problem.

This is a recurring pattern with technology adoption: we use tools to patch over systemic problems rather than addressing the problems themselves. You could reduce the documentation burden by changing how documentation is required. You could reduce shift length by hiring more doctors. You could reduce resident burnout by restructuring training. Or you could implement AI that lets people work harder without burning out quite as much.

Guess which option most hospitals pick? The one that requires the least institutional change.

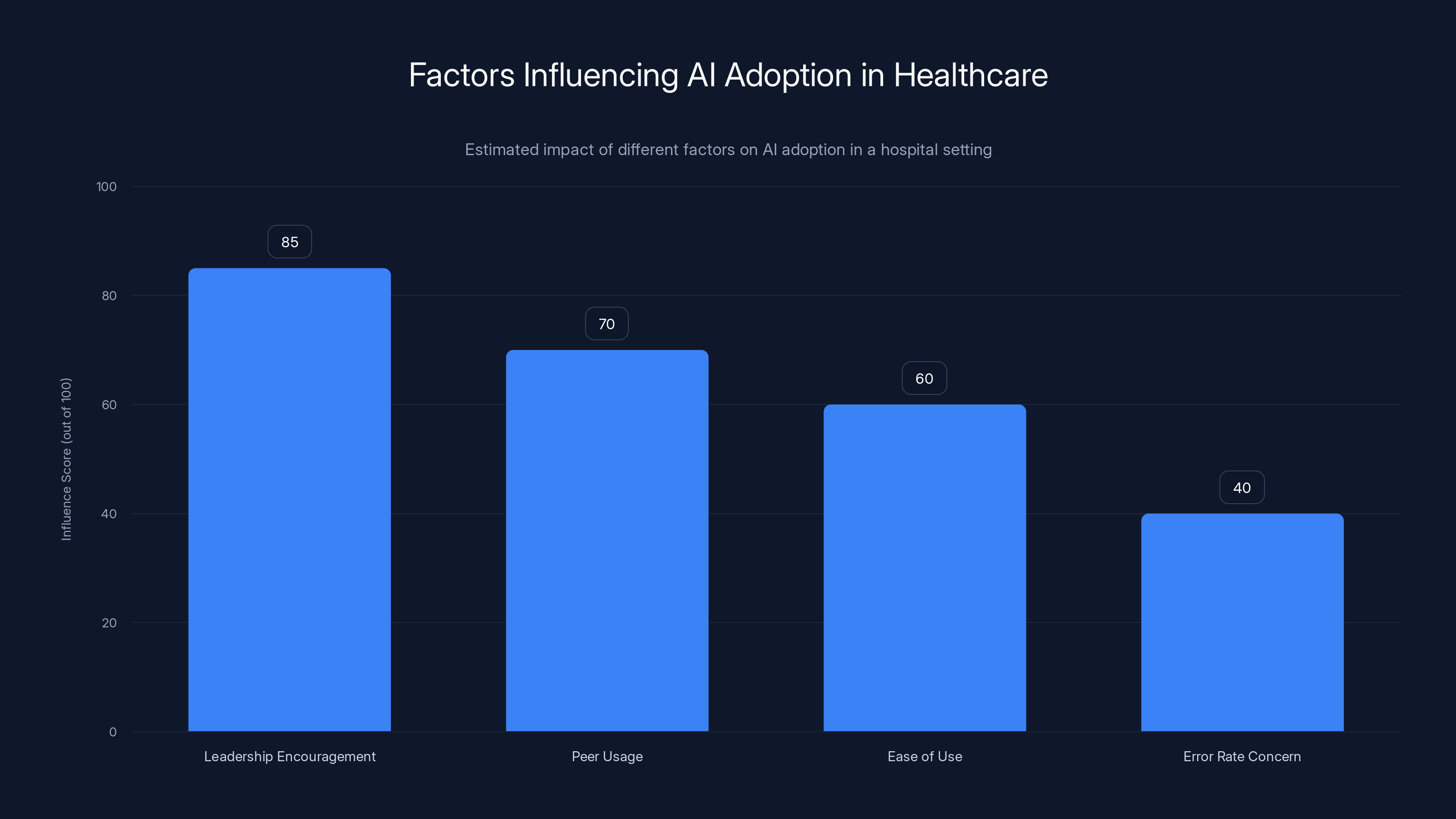

Leadership encouragement has the highest influence on AI adoption, followed by peer usage. Error rate concerns have the least influence. (Estimated data)

Real Cases: Where Medical AI Actually Goes Wrong

The Pitt's storyline isn't speculative. Healthcare institutions across the country have discovered serious problems with AI tools in medical settings, and those discoveries have taught us something important about how to think about AI in critical applications.

One hospital system discovered that an AI system they'd implemented to summarize clinical notes was creating false information. The AI would generate plausible-sounding clinical summaries that sometimes omitted crucial information and sometimes invented details that never appeared in the original notes. Doctors using the AI summaries to make care decisions were operating on incomplete or false information.

Another case involved an AI system designed to help interpret medical images. The system was accurate in its training data, but when it was deployed to a different hospital, its accuracy dropped significantly because the imaging equipment was slightly different, the patient population had different characteristics, and the way images were being taken had subtle variations. The hospital didn't catch this drop in accuracy until patients had already been affected.

There have been cases where AI systems designed to triage patients—determining which patients need urgent care—have systematically under-triaged some patient populations, leading to delayed care and patient harm. When the issue was investigated, the problem came down to training data: the AI had been trained on historical triage decisions that themselves contained biases about which patients' complaints should be taken seriously.

None of these incidents were caused by the AI being obviously broken or completely unreliable. In each case, the AI was approximately doing what it was supposed to do, but the approximation had consequences when applied in the real world.

What these cases teach us—and what The Pitt illustrates—is that deploying AI in high-stakes environments requires different thinking than deploying it in lower-stakes contexts. If an AI makes mistakes when you're suggesting content for a social media feed, that's annoying but not dangerous. If an AI makes mistakes when you're helping doctors decide how to treat patients, that's a different kind of problem.

Most of the safeguards that have emerged in healthcare settings since these problems came to light involve increasing human oversight. Not eliminating AI tools—the benefits are real—but building in mandatory review by qualified humans, maintaining the ability to override AI recommendations, and keeping AI in an advisory role rather than a decision-making role.

The Pitt hints at this with Dr. Al-Hashimi's warnings. The goal isn't to eliminate the tool. It's to use the tool in a way that maintains human judgment as the actual point of decision.

Expertise Matters: Why Experience Gets Skeptical

One detail The Pitt gets right that many AI narratives get wrong is why experienced people tend to be more skeptical of AI tools than newcomers.

It's not that experienced doctors are afraid of technology or stuck in their ways. It's that experience teaches you something specific: most failures in your field aren't from doing things wrong in obvious ways. They're from subtle mistakes that look fine until they matter.

Dr. Robinavitch isn't skeptical of the transcription tool because he doesn't understand it. He's skeptical because he's seen what happens when people trust systems that work 90% of the time. He's developed an intuition for where failures are likely to hide.

There's research supporting this. Studies of expert judgment in domains like medicine, aviation, and law enforcement show that experts maintain calibrated skepticism better than novices do. They're not more skeptical across the board—they actually trust themselves more in areas where they've demonstrated competence. But they're skeptical about tools and systems that promise to do things that they know are actually difficult.

This is because expertise isn't just knowing how to do something. It's also knowing where it can go wrong. It's knowing what factors matter and what factors don't. It's having an intuition for edge cases.

When an experienced doctor sees an AI tool that transcribes medical information, they don't just evaluate whether it works most of the time. They evaluate it based on their understanding of what kinds of mistakes matter in medicine and whether they think the tool is likely to make those kinds of mistakes.

A second-year resident like Dr. Santos might not have that intuition yet. She's smart and capable, but she doesn't have years of experience recognizing subtle mistakes. So when the AI tool works, she's more likely to calibrate her skepticism to "this usually works." An experienced doctor calibrates to "this could be making subtle mistakes I can't easily catch."

This is actually a feature, not a bug, of expertise. The skepticism that comes with experience is one of the things that keeps experienced professionals from making catastrophic mistakes. The Pitt recognizes this and doesn't show Dr. Robinavitch as wrong for being skeptical. It shows him as someone whose skepticism is informed by experience.

But the show also doesn't suggest that experience alone solves the problem. Dr. Robinavitch can be skeptical all he wants, but if the hospital administration decides to implement the AI tool anyway, his skepticism becomes mostly beside the point. The real question is whether the systems around the tool are set up to catch the mistakes that skeptical people worry about.

Institutional Pressure and Individual Choice

What makes The Pitt's treatment of AI adoption especially realistic is that it shows how institutional decisions get made independently of whether they're wise.

Dr. Al-Hashimi isn't forcing the transcription software on anyone. She's encouraging its adoption because it would solve a real problem she can see on her shift. But the fact that she's encouraging it probably matters more than individual doctors' skepticism, because encouragement from leadership tends to become implicit expectation, which becomes pressure.

If the hospital administration, following Dr. Al-Hashimi's recommendation, officially adopts the tool, then suddenly skeptical residents are working in an environment where the default is that they should be using the tool. Maybe they can opt out, but opting out creates friction. "Why aren't you using the tool everyone else is using?" becomes a question they have to answer.

Over time, the path of least resistance is using the tool. And once you're using the tool, you start building workflows around it. Your habits adjust. Your attention distribution changes. The skepticism that might have protected you against mistakes erodes because you're operating on assumptions that the tool is reliable.

This isn't about individual doctors making bad choices. This is about how organizational systems tend to normalize decisions once they're made. The Pitt shows this happening not as a dramatic moment but as the natural consequence of institutional decisions being made by busy people with legitimate reasons for their choices.

It's also worth noting that The Pitt shows Dr. Al-Hashimi as not reckless. She's not saying "don't worry about the errors." She's explicitly telling residents that they need to review everything. She's trying to have the best of both worlds: the time savings from AI plus the oversight that would actually make the tool safe.

The problem is that you probably can't have both. If you're saving meaningful time with the AI tool, there probably isn't time left for full review of everything the tool generates. You've already saved the time you were going to save. Adding review back into the process means adding back time. You're back to the original problem.

So what actually happens in real institutions is that review becomes less rigorous. People spot-check instead of reviewing everything. Documentation that seems less critical gets checked less carefully. The speed of review increases to accommodate the volume. Shortcuts multiply.

The Pitt doesn't show all of this explicitly, but it hints at it. And that's probably more realistic than showing a detailed breakdown of all the ways a well-intentioned system can degrade over time.

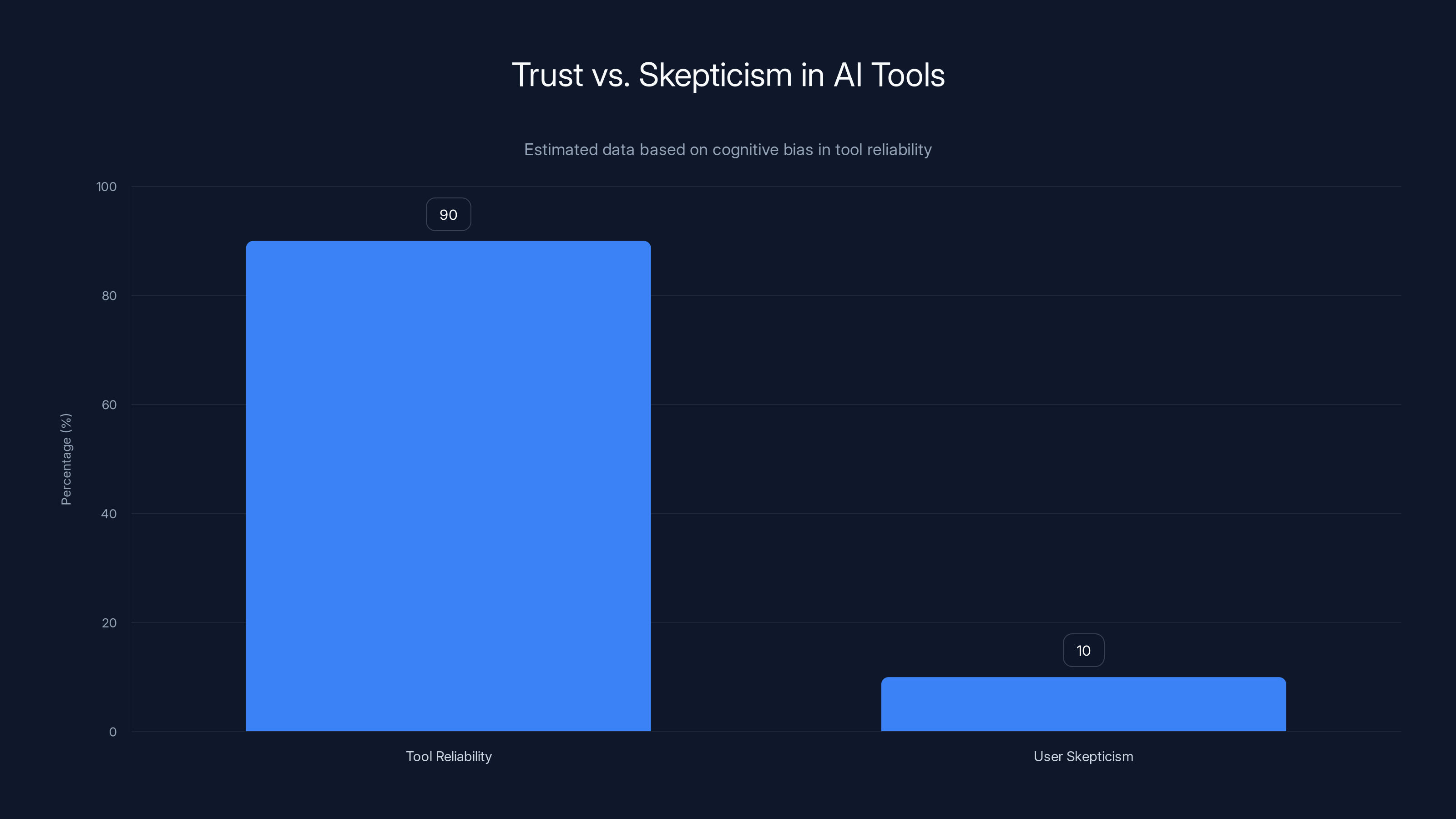

Estimated data shows that as AI tools are perceived to be 90% reliable, user skepticism drops to around 10%, highlighting a cognitive bias where users underestimate the need for vigilance.

The Liability Problem Nobody Talks About

There's a dimension to AI adoption in medicine that The Pitt acknowledges but doesn't dwell on: legal liability.

If something goes wrong with a patient because an AI tool made a mistake, who's responsible? The doctor who didn't catch the error? The software company that created the tool? The hospital that decided to implement it? This is actually a serious unsolved problem in healthcare law.

Most AI tools come with terms of service that essentially say: "We're not responsible for the consequences of using our product." The liability ends up landing on the hospital and the doctors. But if the tool is generating errors that are difficult to catch, are doctors actually responsible for not catching them? Should they be?

From a legal perspective, the answer is probably yes. The standard of care in medicine is what a reasonable, competent doctor would do. If a reasonable doctor would be expected to catch an error that an AI tool made, then a doctor who uses the tool and misses the error hasn't met the standard of care. But that creates an impossible situation: you're supposed to review everything the tool generates for errors, which means you're doing the work the tool was supposed to save you from.

Some hospitals have responded by adding additional oversight—having the AI tool's work reviewed by a second doctor, for example. But that requires additional resources that hospitals don't have. You're back to the problem that made the AI tool attractive in the first place: there's more work than time to do it.

The Pitt doesn't dive deep into this, but it's present in the background. When the surgeon storms into the ER because a chart had glaring errors, part of what's making him angry is the awareness that if a patient had been harmed, there would be a clear chain of responsibility that would end with someone having failed to do their job correctly.

This legal dimension actually explains a lot of why hospitals are slow to adopt AI tools even when they would clearly save time. The liability question is unsettled. Hospitals are hesitant to be the ones that explicitly accept new legal risks by implementing tools that might make things better and might make things worse in novel ways.

But The Pitt also suggests why that hesitation might not survive long. If the alternative to adopting AI is burning out residents until they make worse mistakes, then the liability calculation changes. You're not choosing between risk and safety. You're choosing between different kinds of risk.

Training the Next Generation with Imperfect Tools

There's another dimension that The Pitt touches on that's especially relevant for doctors-in-training: if residents are using AI tools to document their work, what are they actually learning?

Medical training isn't just about knowing the right things. It's about developing patterns of thought and attention that keep you from making mistakes. You learn how to organize your thinking by learning to organize your notes. You learn what matters by learning what to write down. You develop intuition about what's important by making thousands of small decisions about what to include and what to leave out of your documentation.

If a resident uses an AI tool to generate their documentation, they're outsourcing part of that learning process. The AI tool is doing the thinking about how to structure the information and what to emphasize. The resident is skipping steps in their own development.

There's a parallel here to something that happened with GPS. A generation of drivers that relied on GPS for navigation developed worse spatial reasoning about the places they drove. They knew how to get somewhere, but they didn't understand the geography of the place. The tool worked fine for getting to your destination, but it changed the kind of knowledge people developed.

Medical documentation might work the same way. Using the AI tool gets the documentation done faster, but it might change what residents actually understand about their own clinical reasoning. They're learning to dictate observations to a machine rather than learning to synthesize those observations into a coherent understanding of the patient's problem.

That might be fine. Maybe the future of medicine doesn't require residents to be great at documentation because the documentation will be automated. But it might also mean that residents are developing different kinds of expertise and potentially missing some of the learning that happens through documentation.

The Pitt doesn't make this explicit, but Dr. Robinavitch's skepticism might partly be rooted in this. The tool doesn't just affect how work gets done this year. It affects how the next generation of doctors learn to think about their work.

The Economics of AI in Healthcare

Underlying all of The Pitt's narrative about AI adoption is an economic reality that the show captures implicitly: AI tools are much cheaper than hiring more doctors.

The reason the hospital is considering the transcription tool in the first place is economic. Hiring more emergency medicine physicians would reduce the burden on existing staff. Increasing nurse staffing would help. Hiring dedicated documentation specialists would work. All of these approaches would cost money. The AI tool is a cheaper way to get some of the same benefit.

From a hospital finance perspective, this is obvious. Why would you pay for new staff when you can buy software? The software is a one-time capital expense. New staff is ongoing costs. It's not even a close calculation from a business perspective.

But this creates a situation where the incentive structure is pushing toward AI adoption not because it's the best solution for patient care or for resident training, but because it's the cheapest solution for the hospital. The tool doesn't have to be the best approach. It just has to be cheaper than the alternative and acceptable on liability grounds.

The Pitt hints at this by showing the pressure coming from institutional logic rather than from individual doctors being careless. Dr. Al-Hashimi isn't promoting the tool because she's reckless. She's promoting it (presumably) because the hospital administration has decided this is the approach they're taking, and she's trying to implement it in the safest possible way.

That's a more realistic picture of institutional technology adoption than the usual narrative where individual heroes fight against incompetence or malice. Most bad technology decisions happen because of economic pressure, not because anyone is being deliberately dangerous. The people implementing the tools are usually trying to do the right thing within constraints they didn't choose.

But that doesn't make the risks disappear. It just means the risks are being accepted for economic reasons, often by institutions rather than by individuals. The irony is that if something goes wrong and a patient is harmed, the individual doctors take the legal risk, not the institution. So the incentives are misaligned: hospitals have incentive to adopt tools for economic reasons, but doctors have incentive to be skeptical because they're individually responsible for failures.

The Pitt captures this tension beautifully without being preachy about it. It just shows the genuine conflict of interests and lets the audience recognize it.

Estimated data shows that false summaries and accuracy drops are the most common issues in medical AI implementations, highlighting the need for careful deployment and monitoring.

What Real Safety Looks Like

If there's a template for how to use powerful tools in critical applications without catastrophic failures, it comes from fields like aviation and nuclear power. These fields figured out decades ago that you can't just have smart people and hope everything works out. You need systems.

In aviation, this means things like checklists, redundancy, mandatory cross-checks, and procedures that force you to slow down and verify before proceeding. A pilot doesn't just trust their instruments. They verify instruments against each other. They have backups. They follow established procedures that sometimes feel excessive because most of the time nothing goes wrong.

The reason aviation is so safe isn't because pilots are smarter than other professionals. It's because the field decided a long time ago that the cost of failures was high enough that you needed systematic safeguards, not just good judgment.

Medicine has some of this in critical areas. In operating rooms, there are checklists and verifications. In intensive care units, there are protocols and double-checks. But in areas like emergency medicine documentation, the safeguards are lighter. We rely more on individual judgment and less on systematic verification.

When you introduce an AI tool into that environment, you're adding a component that doesn't have the kind of understanding that human judgment brings. The AI doesn't know what matters. It can't distinguish between critical information and background noise. It can't recognize when something is wrong because it doesn't understand the domain.

So if you're going to use an AI tool, you need more safeguards, not fewer. You need the kind of systematic approach that aviation uses. But that costs time and money. The whole appeal of the AI tool is that it saves time and money.

This is the central tension that The Pitt highlights: you can have AI tools that save time, or you can have safety systems that work, but combining both at the level we currently operate is hard.

That might change. Maybe someday AI tools will be reliable enough that you don't need heavy oversight. But that day isn't here yet. Current AI tools are useful approximations, not replacement intelligence. And when you use approximations in areas where precision matters, you need safeguards.

The Pitt suggests that an intelligent approach would acknowledge this tension openly rather than pretending it doesn't exist. The show doesn't resolve the tension. It just shows smart people wrestling with it.

The Question of Responsibility

One thing The Pitt does beautifully is complicate the question of responsibility when technology is involved.

If an AI tool makes an error in a medical chart, who's responsible? The obvious answer is "the person who didn't catch the error." But that's also unfair if the error was hard to catch or if the person was under time pressure that the tool was supposed to relieve but didn't actually relieve.

Alternatively, you could say the AI company is responsible. They made the tool. They should have made it better. But that's complicated because the tool did do what it was supposed to do—it transcribed dictation accurately most of the time. It's not broken. It's just not perfect.

Or you could say the hospital is responsible. They decided to implement the tool. They set the conditions under which it would be used. But the hospital's decision to use the tool was made in response to the real problem that residents didn't have enough time to do their work. The hospital didn't create that problem.

The Pitt doesn't pretend this is simple. Different people might have different levels of responsibility, or the question might not have a clean answer. What matters is that the show recognizes that introducing tools into complex systems creates ambiguity about who's accountable for failures.

That ambiguity is actually dangerous. Clear responsibility is a protection. If everyone is partially responsible, everyone is less responsible. Someone needs to be accountable for ensuring that AI tools in medical settings are being used safely. If that accountability is unclear, it probably won't happen.

Most of the good implementations of AI tools in healthcare have solved this by putting a specific person—usually someone with both clinical knowledge and authority—in charge of oversight. That person is responsible for ensuring the tool is being used appropriately and for catching its failures before they affect patients. But that requires a person, which requires resources, which means the tool doesn't save as much time as the marketing promised.

We keep coming back to the same core tension: AI tools promise to solve problems by saving time and money, but using them safely costs time and money. You can get the benefits and take on the risks, or you can get the benefits plus invest in safety, but the second approach defeats part of the point of using the tool.

Where AI Actually Helps in Medicine

For all its justified skepticism about AI adoption, The Pitt doesn't suggest that AI has no place in healthcare. The show is too smart for that. It acknowledges places where AI genuinely helps.

AI systems for image analysis are one area where the technology actually does provide substantial value. A radiologist reading a chest X-ray can miss subtle findings. An AI system trained on thousands of X-rays might catch subtle patterns that humans miss. The AI isn't replacing the radiologist. It's augmenting human judgment by flagging things that might warrant closer attention.

Another area is research and data analysis. AI tools can identify patterns in large medical datasets that humans would take forever to find manually. If you're looking for rare side effects or unusual patient populations, AI can help. These applications don't involve immediate patient care, so the stakes are different.

Access tools are another area where AI helps. Using natural language processing to make medical information searchable, or using machine learning to help patients understand their conditions, or creating tools that help non-specialists access medical knowledge without drowning in details. These applications don't replace expertise. They extend reach.

Diagnostic support is a gray area. There's potential for AI to help doctors diagnose rare conditions by flagging the pattern and suggesting what you should be thinking about. But the research is mixed on whether current tools actually improve outcomes, partly because doctors sometimes over-trust the tool and partly because the conditions are rare enough that proving improvements requires a lot of data.

The Pitt's transcription tool falls into a category where the potential benefits are real but the complications are also real. It actually does save time for documentation. The problem is that it's doing something that matters—it's creating official records of medical decisions—and it's not perfect at doing it.

The tool would probably work fine if documentation didn't matter much. If medical charts were mainly for reference and weren't used for critical decisions, the errors would matter less. But documentation is how we communicate with other doctors and with future versions of ourselves. It's the record of our thinking. When it's wrong, it matters.

Estimated data shows that most TV shows portray AI as either a savior or a threat, with few exploring realistic scenarios. 'The Pitt' is notable for its nuanced depiction.

The Broader Media Conversation About AI

One reason The Pitt's approach to AI is refreshing is that most media coverage of AI falls into predictable patterns. Either it's hype (AI is going to transform everything, and skeptics are being short-sighted), or it's doomism (AI is going to kill us all, and anyone promoting it is reckless), or it's balance-as-default (on one hand AI has benefits, on the other hand it has risks).

The Pitt avoids all three by actually thinking about how the technology would interact with real institutions and real people. It doesn't assume AI is inherently good or bad. It assumes AI is a tool with specific affordances and limitations and asks how those specific affordances and limitations would play out in a specific context.

That's much harder than any of the standard approaches, which is probably why television rarely does it. But it's also much more useful than the standard approaches because it actually helps people think about decisions they might face.

If you're a hospital administrator, you don't need to be told that AI is good or bad. You need to understand the specific trade-offs of the specific tool you're considering. If you're a doctor, you need to understand how a tool would actually change your work and what new risks it would introduce. If you're a patient, you need to understand how technologies adopted for convenience might affect the care you receive.

The Pitt provides a framework for thinking about these questions that's much more useful than most media coverage provides. It shows how good intentions can lead to systems that have unintended consequences. It shows how institutional pressure works differently than individual choice. It shows how time pressure can erode safeguards. It shows how convenience can be dangerous.

None of this is original to The Pitt. These are lessons that fields like aviation learned decades ago. But in the context of media coverage of AI, it's surprisingly novel to see a show that actually thinks carefully about technology rather than using it as a plot device.

The Human Element in Every Decision

Ultimately, The Pitt's insight is that there's no algorithm for deciding whether to adopt a tool. There's no decision tree that spits out the right answer. There are trade-offs, and the people involved have to decide what trade-offs they're willing to accept.

Dr. Al-Hashimi might ultimately be right that the transcription tool is worth adopting despite the risks. Or Dr. Robinavitch might be right that the risks aren't worth the benefit. Or they might both be partly right and the real problem is somewhere else entirely. The show doesn't resolve this because it can't be resolved at their level. It's an institutional and societal decision, not a clinical decision.

What matters is that the show takes the question seriously. It doesn't use AI as a plot device to create drama. It uses the adoption of a tool as a lens to explore deeper questions about how we make decisions under pressure, how we manage risk, how we balance convenience against safety, and how we maintain human judgment when we introduce tools that are partially intelligent.

These questions matter because they're not going to go away. Healthcare systems will continue to adopt AI tools because the economic pressures and the genuine problems those tools partially solve are real. The question is whether we approach those adoptions thoughtfully or just let them happen because they're convenient.

The Pitt suggests that thoughtfulness requires acknowledging real tensions rather than pretending they can be easily resolved. It means respecting both the potential benefits of tools and the risks they introduce. It means maintaining skepticism not because the tools are bad but because the stakes are high enough that skepticism is warranted.

It means, in short, the kind of careful thinking that good medicine has always required, applied to tools we don't fully understand yet.

Why This Story Matters Now

The Pitt arrives at a moment when AI adoption in healthcare is accelerating without the kind of careful thought that The Pitt demonstrates. Hospitals are implementing tools because they're available and they promise benefits. Research on whether those tools actually improve outcomes is still emerging.

What's clear is that speed and convenience aren't the right metrics for evaluating medical tools. Safety and efficacy matter more. But speed and convenience are what you measure when a tool launches. The safety implications only become apparent after adoption, and by then the tool is embedded in your workflows.

A show like The Pitt that actually thinks carefully about these dynamics is doing important cultural work. It's helping audiences develop intuition about how to think about technology. It's suggesting that appropriate skepticism isn't the same as Luddite thinking. It's showing that good people can disagree about these questions and that the disagreement often stems from different risk tolerances rather than different levels of intelligence or caring.

Most importantly, it's suggesting that these decisions matter. The technology we adopt changes the work we do. It changes the professions we inhabit. It changes the kind of expertise we develop. Those changes aren't trivial. They deserve to be thought about carefully.

In a media landscape where most coverage of technology is either breathlessly enthusiastic or apocalyptic, that's genuinely valuable.

Conclusion: The Pitt as a Model for Tech Storytelling

HBO's The Pitt demonstrates something that television doesn't do often enough: it uses a specific technology as the lens for exploring larger questions about how institutions make decisions, how we manage risk, and how we maintain human judgment in the face of tools that are both helpful and dangerous.

The show doesn't provide answers to the question of whether hospitals should adopt AI transcription tools. It doesn't need to. What it does is provide a framework for thinking about the question that's more sophisticated than most people bring to these decisions. It shows the genuine trade-offs without pretending they're simple. It respects the intelligence of both skeptics and enthusiasts while suggesting that neither side can ignore what the other is saying.

The central insight is that good intentions don't guarantee good outcomes when you introduce powerful tools into complex systems. The tool might actually work. The benefits might be real. But introducing the tool changes the system in ways that might create new problems. Recognizing this doesn't mean rejecting the tool. It means being honest about what you're trading and building safeguards to protect against what you're risking.

Dr. Al-Hashimi and Dr. Robinavitch reach different conclusions about the transcription software, but they're drawing from the same well of professional experience that tells them this decision matters. The show trusts its audience to see that depth and complexity is more interesting than either of the characters being obviously right or obviously wrong.

In the context of coverage about AI, where nuance is rare and alarmism or hype is common, that's genuinely refreshing. The Pitt suggests that you can take technology seriously without being either a booster or a skeptic. You can acknowledge real benefits while maintaining justified skepticism about risks. You can support adoption while demanding safeguards.

Most importantly, the show suggests that these conversations matter. How we adopt technology shapes the institutions we work in and the skills we develop. Getting it right isn't guaranteed. But getting it wrong has consequences. The Pitt reminds us that it's worth thinking carefully about.

TL; DR

-

HBO's The Pitt explores AI adoption in healthcare with genuine nuance, presenting the real tension between using tools that are convenient but imperfect in settings where mistakes matter.

-

The core conflict isn't that AI is bad, but that introducing partially reliable technology into time-pressured environments creates new risks even as it partially solves existing problems.

-

Real hospitals are facing these exact decisions now without clear guidance on how to balance the benefits of AI tools against the risks they introduce.

-

The show demonstrates excellent storytelling about technology by avoiding simple good-versus-bad narratives and instead exploring the messy reality of how institutions adopt tools under economic and operational pressure.

-

Appropriate skepticism about AI in medicine doesn't require rejecting the technology, but does require building safeguards and maintaining human oversight rather than assuming the tool solves problems it only partially addresses.

FAQ

What is The Pitt and how does it approach AI?

The Pitt is an HBO medical drama set in an emergency room that takes place over a single 15-hour shift. In its second season, the show explores the adoption of generative AI transcription software in a realistic and nuanced way, examining both the genuine benefits such tools offer to exhausted medical professionals and the real risks they introduce when not properly safeguarded.

Why does the show focus on transcription AI specifically?

Transcription AI is a perfect case study because it actually does save time—which is a genuine problem for emergency medicine physicians—but also introduces errors that can be subtle and difficult to catch. This creates a realistic tension between convenience and safety that forces characters to grapple with genuine trade-offs rather than obvious good-versus-bad scenarios.

How realistic is the scenario The Pitt portrays?

Very realistic. Hospitals across the country are genuinely implementing AI transcription tools in clinical settings right now. The concerns that Dr. Robinavitch expresses about subtle errors being missed under time pressure are based on documented problems with AI-assisted documentation in real healthcare systems.

What is the main conflict between the two senior doctors?

Dr. Robinavitch represents skepticism based on experience, arguing that tools that seem mostly helpful can erode careful judgment over time. Dr. Al-Hashimi represents pragmatism, arguing that the current system is already broken and that an imperfect tool that saves time is better than an unworkable status quo. Both are arguing from legitimate positions.

What does the show suggest about AI in medicine?

The Pitt suggests that AI can be useful in medical settings but that usefulness isn't the same as safety. A tool can work most of the time and still introduce new categories of risk. The show implies that appropriate use requires safeguards, human oversight, and honest acknowledgment of limitations rather than just adopting tools because they're convenient.

How has The Pitt influenced medical AI adoption discussions?

While the show isn't primarily about influencing policy, it provides a sophisticated model for how to think about technology adoption that's more nuanced than most media coverage provides. It suggests that good intentions and real benefits don't eliminate the need for skepticism and systematic safeguards.

What mistakes do institutions typically make when adopting AI tools?

Common mistakes include: assuming that tools that work in training data will work the same way in real-world settings with different populations and conditions, eliminating human oversight because the tool is supposed to save time, failing to build in systematic verification because verification defeats the time-saving purpose, and assuming that users will maintain skepticism about tools that mostly work.

Is The Pitt anti-technology?

No. The show is skeptical about uncritical adoption of technology, not about technology itself. Dr. Al-Hashimi is presented as intelligent and legitimate in her desire to use tools that can help her residents. The show's skepticism is directed at the assumption that tools solve problems without creating new ones, not at the desire to use tools.

What does the show suggest about the relationship between technology and human expertise?

The Pitt suggests that technology doesn't replace expertise but rather changes what expertise means. Expertise involves intuition about where things can go wrong. Introducing tools that are partially intelligent can actually erode that intuition if not managed carefully, because people stop paying attention to things they're used to relying on machines for.

How does The Pitt relate to broader questions about AI adoption in society?

The specific case of medical AI illustrates broader patterns that apply to other industries: tools that are convenient often get adopted for economic reasons rather than because they're the best solution, adoption happens under pressure without time for careful evaluation, and introducing new tools often creates new risks alongside solving existing problems. The show suggests that these dynamics deserve more careful attention than they usually receive.

Key Takeaways

- The Pitt presents AI adoption in medicine as a genuine tension between solving real problems and introducing new risks, rather than simple good-versus-bad narratives

- Medical documentation is genuinely time-consuming, making AI transcription tools genuinely attractive despite legitimate safety concerns about subtle errors

- Experienced medical professionals maintain skepticism about tools not because they resist technology but because expertise teaches you where systems fail in ways that aren't obvious

- Institutional technology adoption often happens for economic reasons rather than because the tool is objectively the best solution, creating misaligned incentives between institutions and individual professionals

- Current AI tools are useful approximations, not replacement intelligence—using them safely requires systematic oversight and safeguards that can reduce the time savings that made them attractive

Related Articles

- The Pitt Season 2 Episode 2: AI's Medical Disaster [2025]

- ChatGPT Health: How AI is Reshaping Medical Conversations [2025]

- Luffu: The AI Family Health Platform from Fitbit's Founders [2025]

- UniRG: AI-Powered Medical Report Generation with RL [2025]

- Apple Watch Distribution for Free by Health Services: Could It Save Lives? [2025]

- PraxisPro's $6M Seed Round: AI Coaching for Medical Sales [2025]

![How HBO's The Pitt Tells AI Stories That Actually Matter [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-hbo-s-the-pitt-tells-ai-stories-that-actually-matter-202/image-1-1771544244218.jpg)