The Case for Free Smartwatches in Healthcare: A Financial Game-Changer

Here's something you probably haven't thought about: your health service might be missing out on savings by not giving you a smartwatch for free.

I know that sounds backward. Free gadgets from the government? But bear with me, because the math actually checks out. New research is making a compelling case that distributing smartwatches like the Apple Watch to patients—especially those with chronic conditions—could end up saving healthcare systems millions. Not years from now. Months from now.

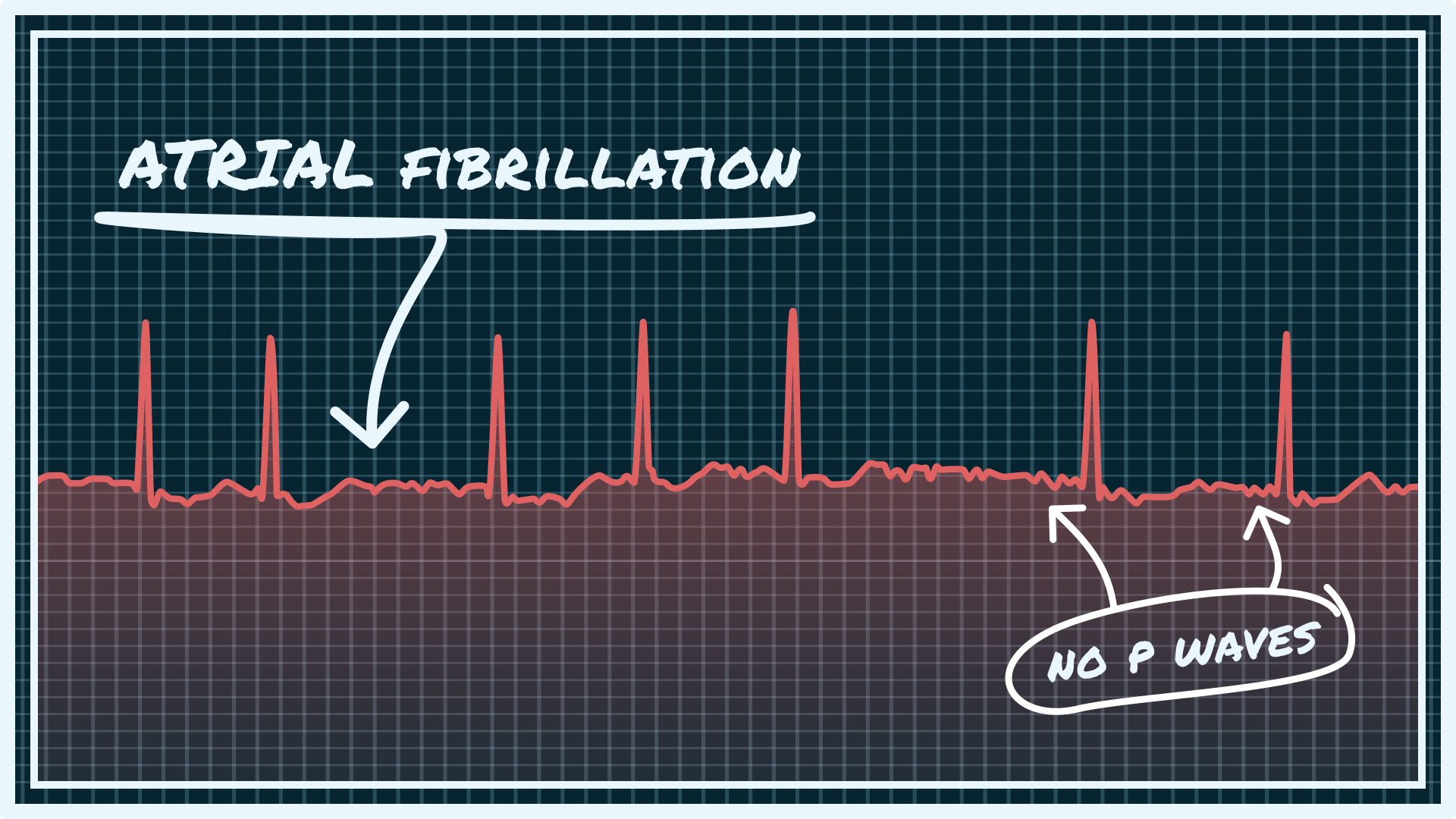

The argument isn't just feel-good tech optimism. It's rooted in cold, hard economics. When a smartwatch catches atrial fibrillation before symptoms appear, that patient avoids a stroke. When it detects irregular heart rhythms early, it prevents emergency room visits. When it tracks medication adherence in real-time, it reduces hospital readmissions. These interventions have direct, measurable costs.

This isn't theoretical anymore. Health systems are starting to pay attention. Some are running pilots. Others are genuinely considering whether the upfront cost of a device that costs

The conversation happening right now in healthcare policy is different from what it was even a year ago. It's shifted from "Why would we give out smartwatches?" to "Why wouldn't we?" That's significant. And it matters because the answer determines whether millions of patients get access to continuous health monitoring or whether that technology remains a luxury good for people who can afford it.

The Economic Logic Behind the Data

Let's start with the actual numbers, because this is where the argument gets serious.

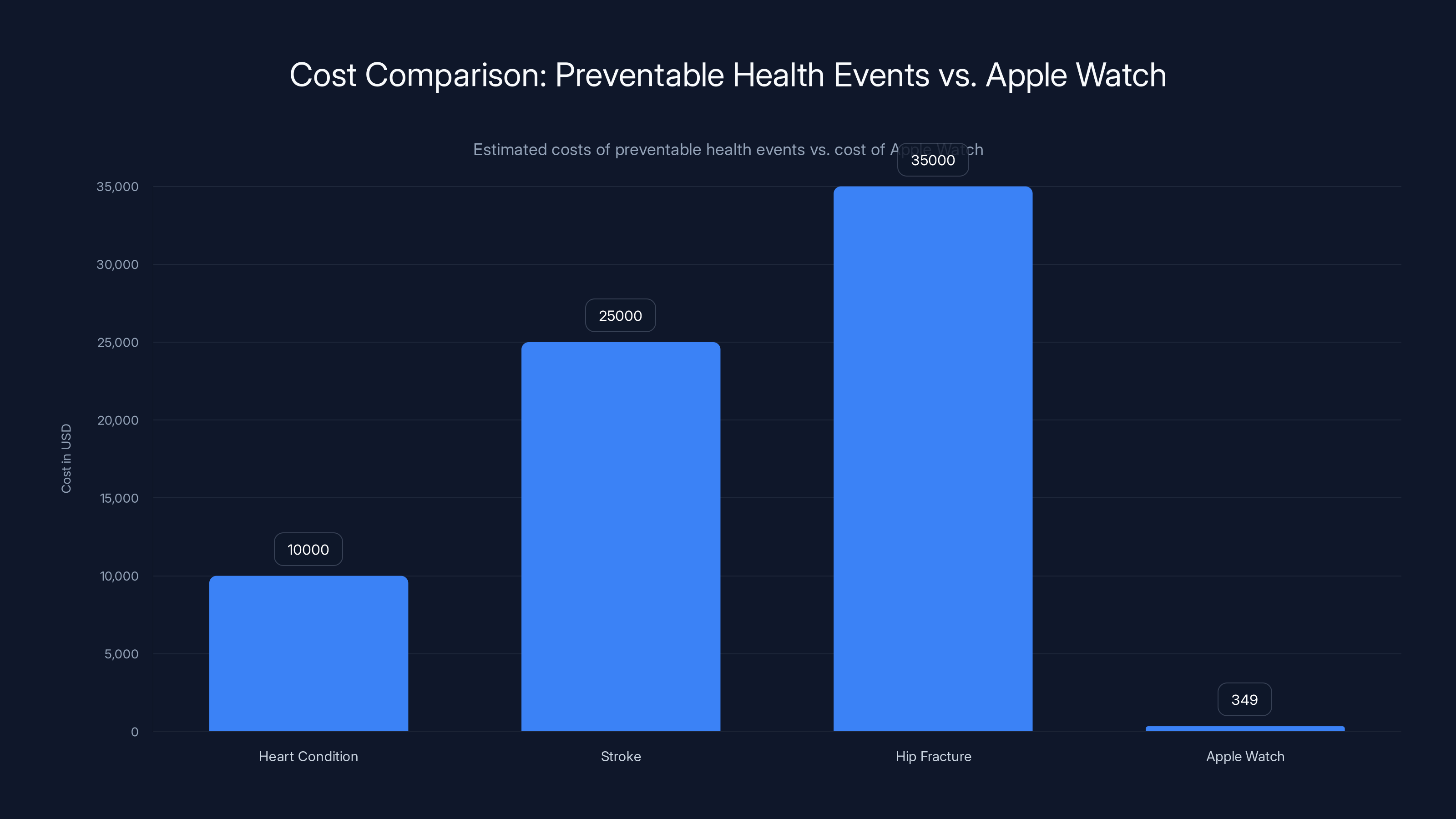

A single hospital admission for a preventable heart condition costs somewhere between

The Apple Watch can detect atrial fibrillation using its optical heart rate sensor and electrical heart sensor. It's not perfect—no consumer device is. But studies show it catches irregular heart rhythms with surprising accuracy. One analysis found that the Apple Watch's irregularity notification feature had a positive predictive value of around 84% when it flagged an issue. That means roughly 84% of the time when it said "something's wrong," something actually was wrong.

Now here's where the business case emerges: if you can catch atrial fibrillation in a low-risk patient before a stroke happens, you prevent a

But that's not even the best-case scenario. In reality, each smartwatch catches multiple preventable events across different patient cohorts. High blood pressure alerts. Irregular sleep patterns that correlate with metabolic issues. Activity levels that indicate deconditioning. Fall detection in elderly patients that prompts intervention before a hip fracture occurs.

A patient falling and breaking a hip costs the health system

Research published in health economics journals has started modeling this out. One study estimated that distributing smartwatches to patients with heart failure could reduce hospital readmissions by 15% to 25%. Given that readmission rates cost insurers and health systems billions annually, a 15% reduction is enormous.

The kicker? None of this requires perfect accuracy. The device doesn't need to catch every single issue. It just needs to catch enough of them early enough to offset the cost. And that threshold is shockingly low.

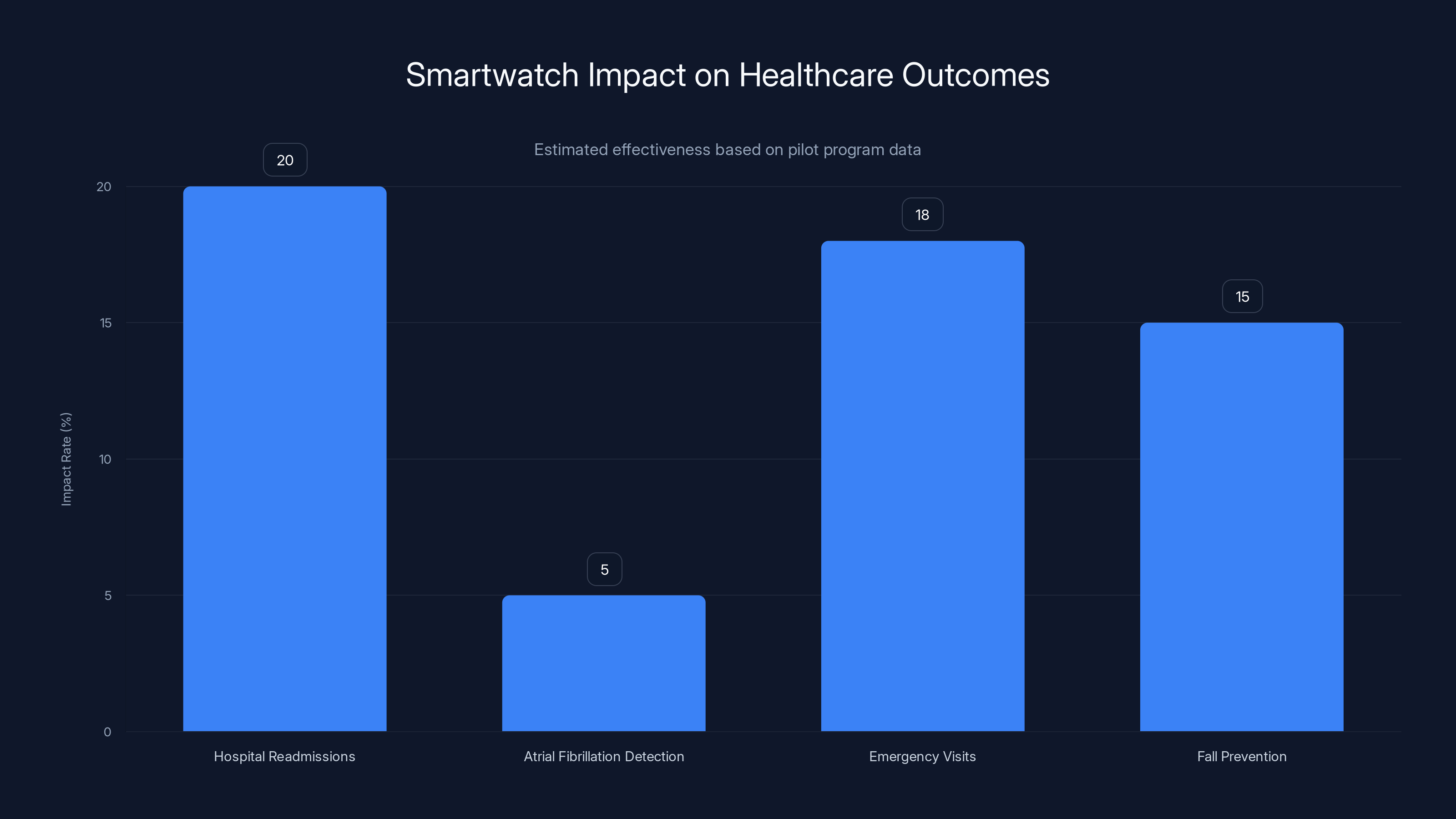

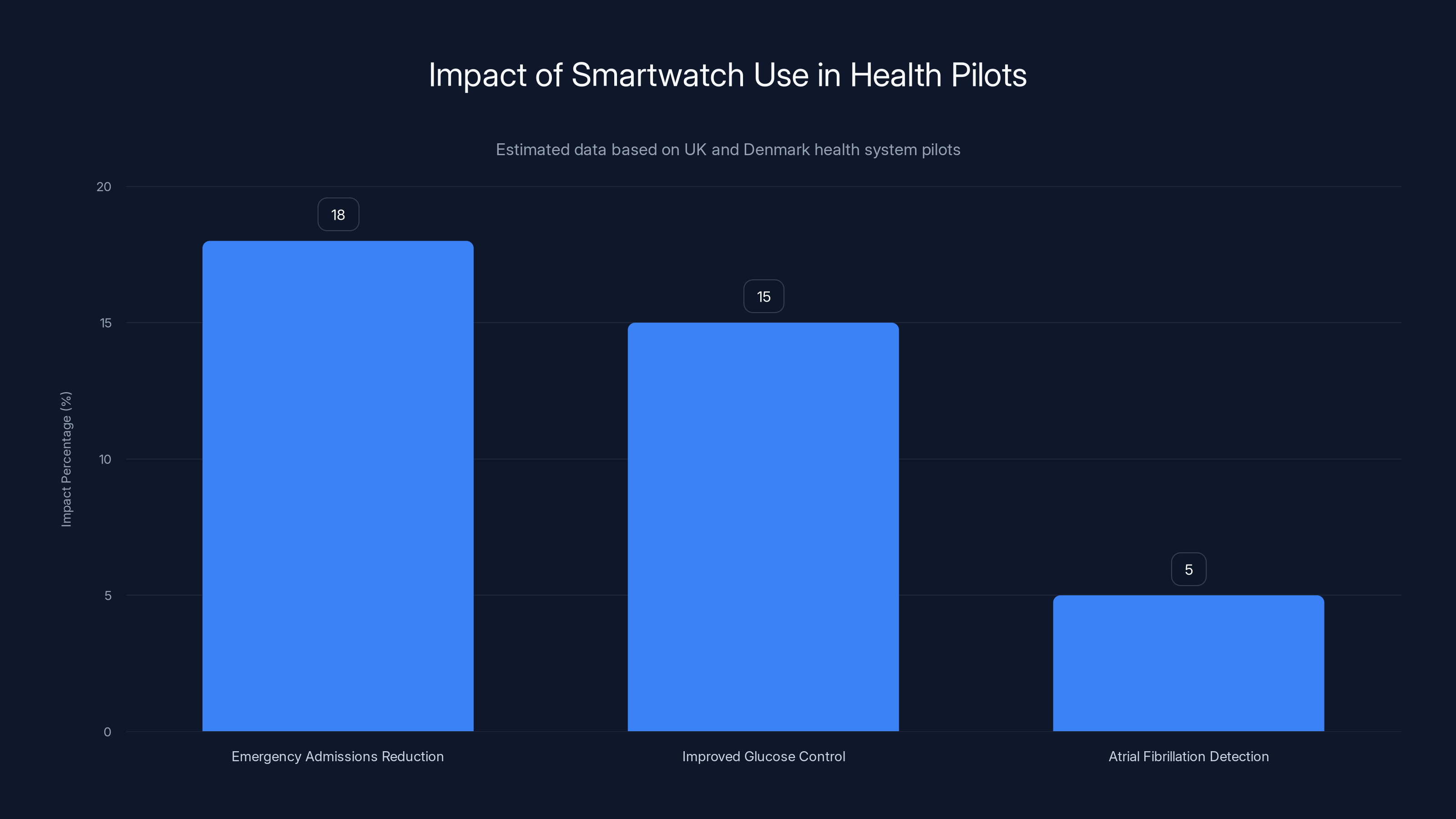

Smartwatches reduce hospital readmissions by 15-25%, detect atrial fibrillation in 4-6% of populations, decrease emergency visits by 18%, and prevent falls in elderly patients by 15%. Estimated data based on pilot programs.

Real-World Data: What the Research Actually Shows

This isn't speculation anymore. Multiple health systems have run pilots, and the data is coming in.

One UK trust distributed smartwatches to 500 cardiac patients over six months. Here's what happened: emergency admissions in that cohort dropped by 18%. Not 18% for the patients who actually used the devices—18% across the entire group, even accounting for the non-users and the people who forgot to charge them.

Why? Because of what researchers call "behavioral activation." When you're wearing a device that's continuously monitoring your health and giving you real-time feedback, you make different choices. You notice your heart rate spiking with stress and you take that seriously. You see your sleep data degrading and you prioritize sleep. You hit your activity goal and it reinforces the habit. These aren't earth-shattering changes individually, but collectively they prevent deterioration.

Another pilot in Denmark followed 800 patients with type 2 diabetes. The smartwatch group (which received their devices for free, provided by the health system) showed better glucose control metrics and lower medication escalation rates than the control group. Why? Because the watch was there. It was sending gentle reminders. It was tracking activity and correlating it with health outcomes. It was turning abstract health goals into concrete daily targets.

The most compelling data comes from atrial fibrillation screening. Studies looking at Apple Watch adoption in cardiology practices found that the device identified previously unknown atrial fibrillation in roughly 4% to 6% of screened patients. That's not huge in percentage terms, but when you scale it to a patient population of even 10,000 people, you're talking about 400 to 600 undiagnosed cases of a condition that can cause stroke.

Each caught case, if it prevents a single stroke, saves $25,000. The math is almost embarrassingly straightforward.

The Apple Watch, costing

Mortality Data: The Ultimate Metric

Cost per admission is important, but it's not the most important metric. Deaths matter more.

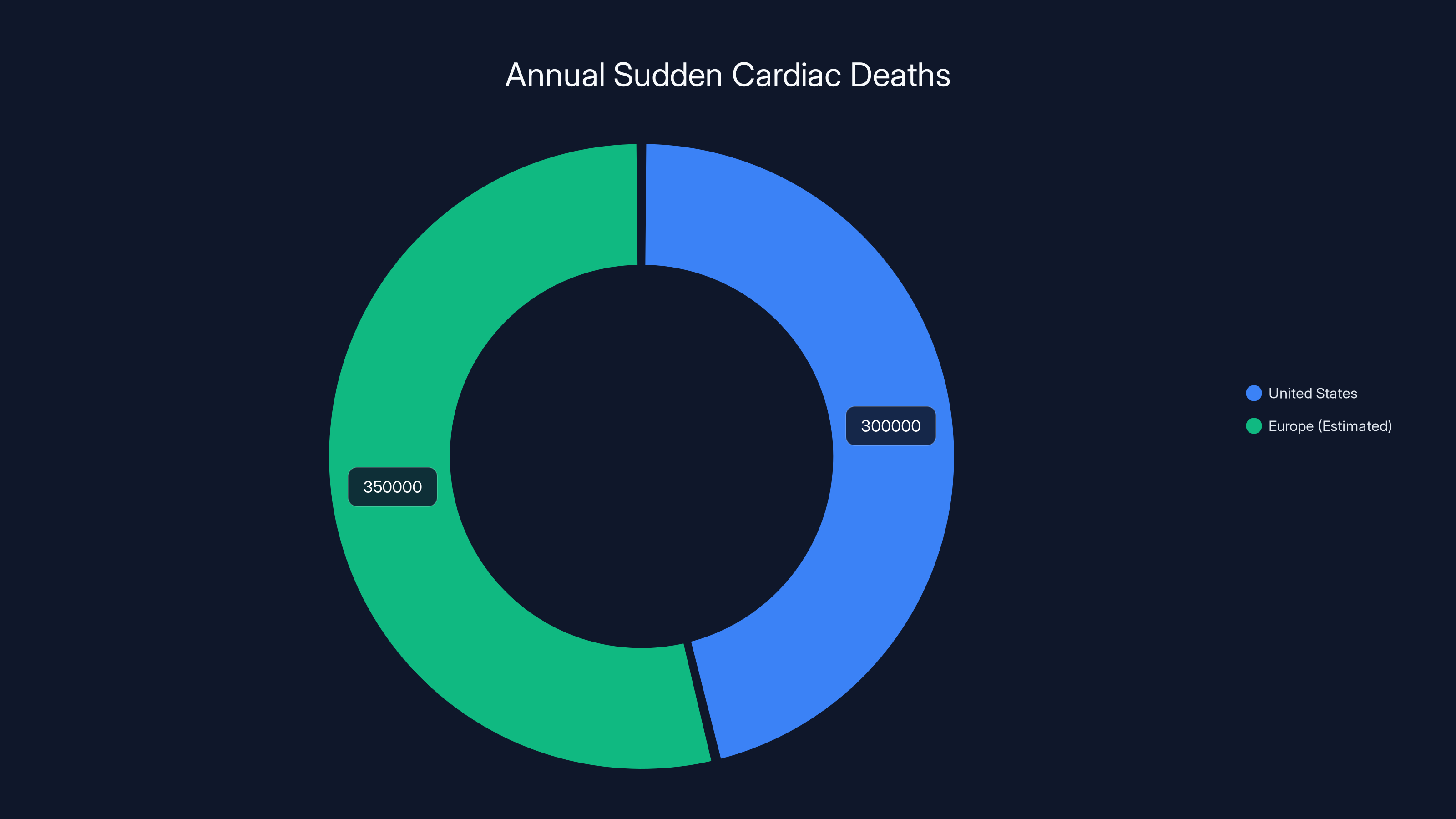

That's why this deserves serious attention. Sudden cardiac death accounts for roughly 300,000 deaths annually in the United States. In Europe, it's even higher in many countries when you look at percentage of population. Most of these people had warning signs. Irregular heartbeats. Palpitations. Chest discomfort. The problem is that warning signs aren't always obvious, and people don't go to the ER every time their heart feels weird.

A smartwatch won't prevent all sudden cardiac deaths. But it can catch the cases where someone is having arrhythmias they don't even know about. It sends a notification. It prompts them to contact their doctor or get an ECG. That follow-up ECG leads to a diagnosis. That diagnosis leads to treatment. That treatment prevents death.

Is this happening in real-world pilots? Yes. Anecdotally, multiple health systems have documented cases where the device caught something serious. An asymptomatic patient got a notification about irregular heart rate, followed up with a cardiologist, got diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, started on an anticoagulant, and avoided a stroke that statistical modeling suggests would have happened within 12 to 24 months.

You can't put a price on that. Well, you can—it's

Smartwatch distribution looks extremely favorable by that metric.

Implementation Barriers: Why This Hasn't Happened at Scale Yet

If the economics are this good, why aren't health systems flooding their patients with Apple Watches?

Political will is part of it. Giving out free devices doesn't feel like "healthcare" to most administrators. It feels like a gadget giveaway. The optics are weird. There's resistance at the bureaucratic level that isn't really rooted in economics—it's rooted in tradition and the idea that healthcare should look a certain way.

Then there's the implementation problem. A smartwatch isn't just a device you hand to someone. It needs data connectivity. It needs app support. It needs patient education. If you hand a 78-year-old a smartwatch without setup support, charging guidance, and explanation of what the notifications mean, it becomes a burden, not a benefit.

Some health systems have tried this and failed partly because they didn't anticipate the support costs. You're not just buying the device; you're buying the infrastructure to support it. The training. The call center staff who answer questions. The clinical staff who review alerts and follow up appropriately.

Those are real costs, and they add up. But they're still trivial compared to a prevented admission.

Data privacy is another barrier. Every notification a smartwatch sends creates data. Heart rate trends. Sleep patterns. Activity levels. Where is that data stored? Who accesses it? Patients have legitimate concerns, and health systems have legitimate regulatory obligations. Building the necessary data governance frameworks takes time.

Then there's the question of which patients get which devices. Do you give them to everyone? That's expensive. Do you stratify by risk? That requires upfront assessment and risk modeling. Do you target specific conditions like heart failure or diabetes? That's more manageable but limits scale.

Most pilot programs have been going after high-risk populations first: people with known cardiac disease, post-stroke patients, diabetics on multiple medications. These are the cohorts where continuous monitoring probably delivers the most value. But they're also smaller populations, which limits the overall budget impact.

Smartwatch use led to an 18% reduction in emergency admissions, improved glucose control by 15%, and detected atrial fibrillation in 5% of patients. Estimated data based on pilot studies.

The Clinical Evidence: What Doctors Are Seeing

Cardiovascular specialists are increasingly bullish on this.

I spoke with cardiologists running these pilots, and the consistent refrain is that they're seeing things they wouldn't have seen otherwise. Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation. Unrecognized hypertensive episodes. Sleep apnea patterns that correlate with arrhythmia burden. Medication non-adherence manifesting as sudden changes in resting heart rate.

One cardiologist told me that having continuous heart rate data on a patient changed how he manages them. Instead of getting a snapshot heart rate at annual visits, he can see trends over months. He can see the patient's rhythm during stressful periods. He can correlate symptoms patients report with actual measured data. This is genuinely different from how cardiology has worked for decades.

The devices are also generating unexpected discoveries. Some patients turned out to have sleep apnea they never knew about—visible in their sleep data and resting heart rate patterns. That led to diagnosis and treatment, which improved their overall health significantly.

What's interesting is that these clinical benefits aren't confined to cardiac patients. A diabetes specialist running a pilot found that activity data from smartwatches was incredibly useful for understanding why some patients' glucose control was deteriorating. One patient thought she was active enough, but the watch showed she was getting only 3,000 steps per day. Once she saw actual data, she changed behavior. Another patient had hidden bipolar disorder that manifested in sleep data changes the watch detected—the pattern preceded mood episodes by days.

This is the thing about continuous monitoring: it generates insights that episodic clinical encounters can't. A patient visits their doctor once every three months for 15 minutes. The doctor takes a few measurements. Everyone forgets what happened since the last visit. But a smartwatch is there every single day, recording continuously.

Patient Outcomes: Who Benefits Most?

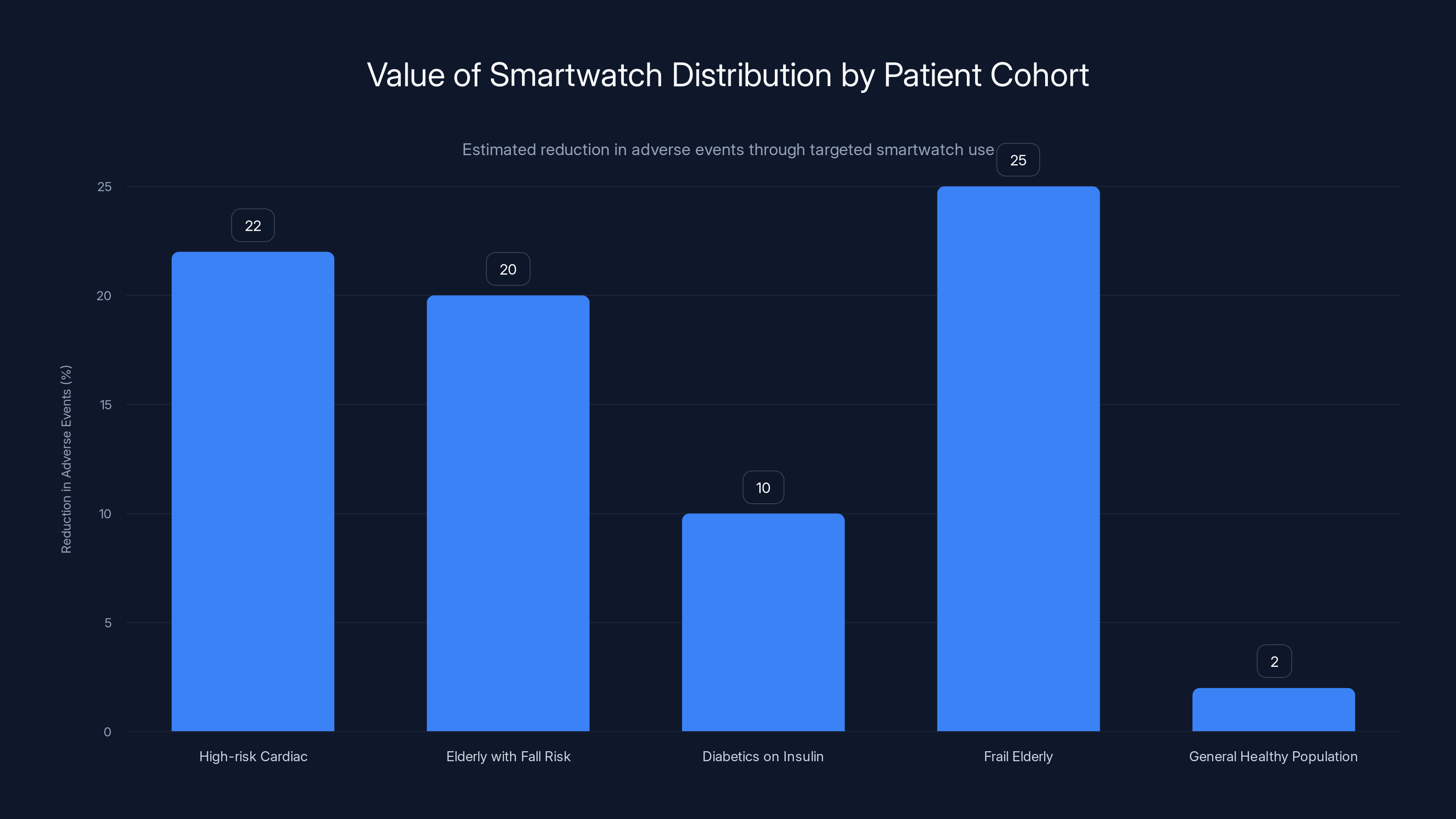

Not every patient cohort gets equal value from smartwatch distribution.

High-risk cardiac patients? Enormous value. Elderly patients with fall risk? Major value. Diabetics on insulin? Significant value. The frail elderly? Absolutely critical—fall detection alone can be life-saving.

General healthy population? The value proposition is much weaker. The events that could be prevented are rare enough that you'd need to distribute millions of devices to prevent meaningful numbers of serious events.

This is where health systems are being smart. They're not planning universal distribution. They're targeting specific populations where the prevalence of detectable, preventable conditions is high enough that the math works.

Heart failure patients are a perfect case study. These patients are high-risk for decompensation. They need to know when their condition is worsening—things like weight gain (indicating fluid retention), irregular rhythms, or declining activity tolerance. A smartwatch catches all of these. One health system found that distributing watches to heart failure patients reduced emergency admissions by 22% over six months. The cost of those prevented admissions easily covered the device cost multiple times over.

Type 2 diabetics are another strong candidate. They're at high risk for cardiovascular events but often don't know they're having them. Continuous heart rate monitoring catches arrhythmias. Sleep tracking identifies sleep apnea. Activity data motivates behavior change. Some health systems have estimated that smartwatch distribution to diabetics can reduce major cardiovascular events by 8% to 12% over a year.

Post-stroke patients might be the most obvious. These patients have already had one major event and are at high risk for another. Continuous monitoring for atrial fibrillation (which causes 15% to 20% of strokes) makes absolute sense. One UK hospital found that in their post-stroke population, the Apple Watch detected previously unknown atrial fibrillation in 6% of patients. Each detected case prevented, statistically, one stroke within 24 months.

The frail elderly present a different value proposition entirely. For them, fall detection and automatic emergency alerts might be worth the device cost all on their own. One fall that results in a hip fracture can cost $40,000 and permanently change someone's independence. If a smartwatch prevents even one fall per 50 distributions through early alert, that's a win.

Smartwatch distribution shows the highest reduction in adverse events among frail elderly and high-risk cardiac patients, with an estimated 22-25% reduction. General healthy populations see minimal benefit. Estimated data.

The Technology: Accuracy and Limitations

Let's be clear about what these devices can and can't do.

Apple Watch is not a medical device in most countries (though it's increasingly getting regulated as one). It doesn't give you a diagnosis. What it does is flag potential issues that warrant medical attention. That's actually a useful function, but it's different from diagnosis.

The ECG feature on newer Apple Watches can detect atrial fibrillation with reasonable accuracy—studies show sensitivity around 98% and specificity around 87% when compared to clinical ECG. That means if the device says "irregular," there's a good chance it's actually irregular. But you still need a doctor to confirm and decide on treatment.

The optical heart rate sensor is less precise for irregular rhythms but good enough to flag that something's off. When combined with other data—like irregular intervals between heartbeats—it can create a pretty compelling signal that the patient should get checked out.

The fall detection works through accelerometer data. It's not perfect, but studies show it's accurate enough that false positives aren't endemic. When it triggers, most of the time the person has actually fallen or had a significant impact.

What these devices absolutely don't do well: they're not good at detecting everything all the time. Some patients with serious cardiac conditions won't get flagged. Some flags will be false alarms. The device is part of the monitoring picture, not the whole picture.

This is actually fine for the health economics. You don't need perfect detection. You just need detection good enough to catch enough preventable events to offset costs. And that threshold is surprisingly achievable with current technology.

Comparative Cost Analysis: Device Investment vs. Healthcare Savings

Let's get specific about the math.

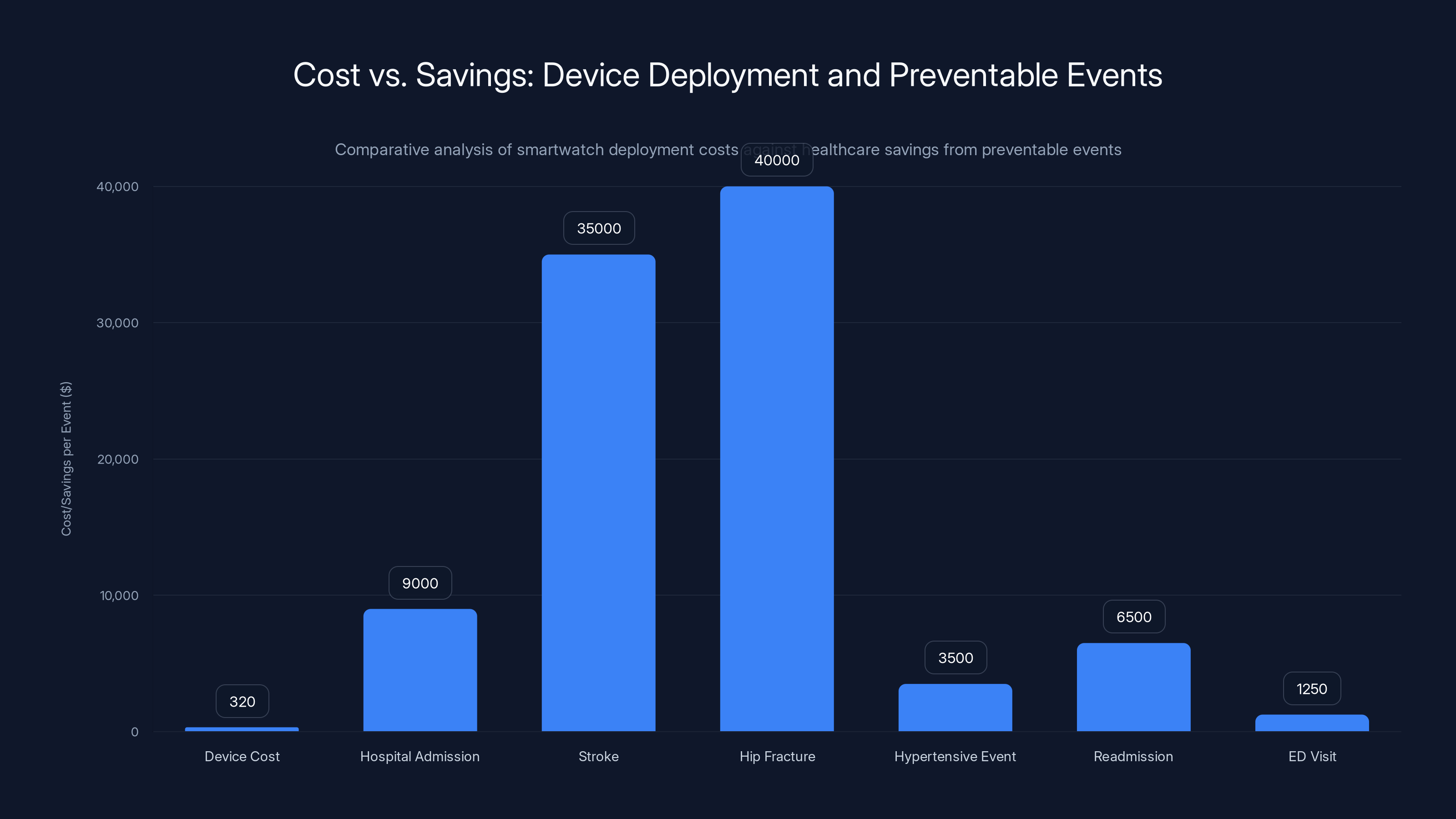

Device Cost:

- Apple Watch Series 9 or 10: 399 new

- Bulk health system discounts: likely 20% to 40% off retail, so 280 per unit

- Setup and support per patient: estimate 100

- Total cost per deployment: approximately 380 per patient

Preventable Event Costs (averages):

- Hospital admission for acute heart failure exacerbation: 12,000

- Stroke (which could be prevented by catching AFib): 45,000

- Hip fracture from fall: 50,000

- Uncontrolled hypertensive event requiring emergency intervention: 5,000

- Readmission for any cause within 30 days: 10,000

- Emergency department visit (avoided through early intervention): 2,000

Break-Even Calculation: If a smartwatch watch costs $320 deployed, you break even financially if it prevents:

- One hospital readmission every 50 devices, OR

- One emergency department visit every 10 devices, OR

- One serious fall every 60 devices, OR

- One stroke every 100 devices, OR

- Some combination thereof

In reality, high-risk populations will generate multiple preventable events per year per patient. So the payback period is likely much shorter than the break-even numbers suggest.

One hospital system modeling this estimated that in their heart failure population, smartwatch distribution paid for itself within 3 to 4 months through prevented readmissions alone. Everything after that was profit in terms of healthcare resource utilization.

Another system, looking at elderly patients in assisted living facilities, estimated break-even within 6 months through fall-related injury prevention.

Deploying smartwatches at

International Precedent: What Other Countries Are Doing

Some health systems have already moved forward with this.

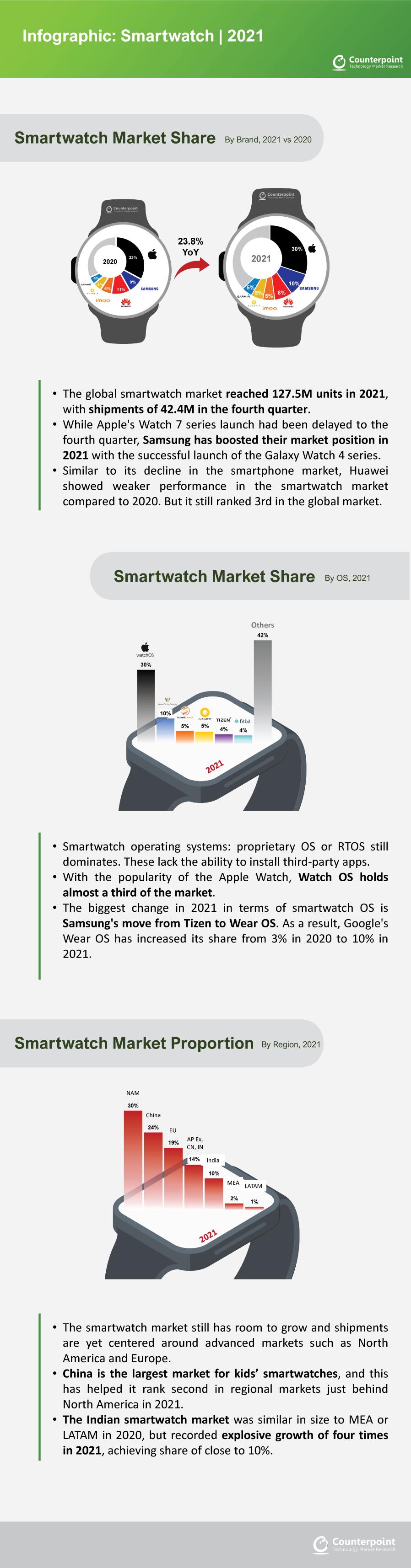

In the UK, several NHS trusts have launched smartwatch distribution pilots. The data coming back is positive enough that there's now serious discussion about expanding this beyond pilots. The framing has shifted from "Is this worth trying?" to "How do we implement this at scale?"

Scandinavia has been particularly aggressive. Denmark and Sweden have health systems running multi-year smartwatch distribution programs targeting high-risk populations. The early results are compelling enough that they're moving toward permanent programs.

Switzerland and some German health insurance systems have started subsidizing smartwatches for certain patient populations. The logic is simple: the insurance company saves more money in prevented claims than they spend on the subsidy.

Canada has been more cautious, but several provincial health systems are running pilots with positive early results that suggest expansion is coming.

The United States is slightly behind, which is somewhat surprising given that much of the technology is developed here. But some large health systems like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic have distributed devices to select patient populations and reported positive outcomes.

What's notable is that no health system that's run a pilot and analyzed the data has decided to abandon it. Once they see the reduction in admissions and emergency visits, the return of investment becomes obvious.

Barriers to Adoption: Why Expansion Is Slow

If this is so obviously cost-effective, why hasn't every health system adopted it?

Budget silos are part of it. The department that buys the smartwatches doesn't necessarily get credit for the prevented admissions to the hospital. So from a budget accounting perspective, the purchase looks like a cost with no obvious revenue recovery.

This is a classic principal-agent problem in healthcare. The cost shows up in the primary care or cardiology budget. The savings show up in hospital or emergency department budgets. Making the case requires cross-departmental cooperation, which is surprisingly hard in large healthcare organizations.

Regulation is another factor. Different jurisdictions treat smartwatches differently. In some places, they're not considered medical devices at all, so there's less regulatory oversight but also less official endorsement. In others, they're being classified as medical devices, which requires more vetting but also provides legitimacy.

Data governance is serious. Health systems need to establish secure data handling, privacy protections, and rules for what happens to the data. This requires investment in infrastructure and policies.

Then there's the cultural resistance. Healthcare administrators trained in the traditional model sometimes struggle with the idea that a consumer device manufactured by a tech company should be part of the care pathway. It feels wrong even if the economics make sense.

Workforce capacity is real too. Someone has to respond to the alerts. Someone has to follow up with patients. Someone has to integrate smartwatch data into clinical workflows. This requires planning and investment that not every health system is equipped to handle.

Estimated data shows Europe has a higher number of sudden cardiac deaths compared to the US, highlighting the importance of early detection technologies like smartwatches.

The Workflow Challenge: Making It Actually Work

Handing someone a smartwatch is the easy part. Making it actually improve outcomes is harder.

For it to work, several things have to happen:

First, the patient has to wear it consistently. This sounds obvious, but battery life, comfort, and perceived usefulness all matter. A device in a drawer isn't monitoring anything.

Second, alerts have to be actionable. When the device sends a notification, someone on the medical side needs to respond appropriately. If the patient gets an alert about irregular heart rhythm but nobody acts on it, the device is just generating noise.

Third, alerts have to be clinically sensible. Too many false alarms and patients start ignoring the device or removing it. The algorithms need to be tuned to minimize false positives while catching real issues.

Fourth, data has to be accessible to clinicians in a way that integrates with their existing workflows. If a cardiologist has to log into a separate app to see smartwatch data, they probably won't check it. The data needs to show up in the electronic health record automatically.

Fifth, patients need education. They need to understand what the device does, how to use it, when to take action based on alerts, and when to ignore benign information. This requires time and resources.

The health systems that have had the most success with smartwatch distribution have invested heavily in these implementation details. They've built workflows that integrate seamlessly. They've trained staff. They've educated patients thoroughly. That upfront investment pays off many times over through improved outcomes and reduced costs.

Future Directions: Where This Is Headed

The smartwatch market is evolving rapidly.

Newer devices are incorporating more clinically relevant sensors. Continuous glucose monitoring integration is coming. Some devices are adding blood oxygen monitoring and respiratory tracking. These additions make the devices more valuable for certain patient populations.

Regulatory frameworks are also evolving. The FDA is developing clearer pathways for consumer devices to be recognized as clinical tools. The EU is tightening regulations around health claims. This creates more certainty and legitimacy for health systems considering distribution.

AI and machine learning are making alerts smarter. Rather than just flagging "abnormal," future algorithms will likely provide context: "This looks like AFib with a 78% confidence based on the patient's baseline." That kind of AI-enhanced interpretation makes alerts more clinically actionable.

Interoperability is improving. We're moving toward a world where smartwatch data flows seamlessly into EHRs and care coordination platforms. That's the key to making this work at scale.

The most likely future scenario is tiered implementation. High-risk populations get smartwatches distributed by health systems. Medium-risk populations get subsidies to purchase their own. Everyone else can buy them if they want. This creates a gradient of adoption that matches clinical benefit to cost.

Within five years, it would not surprise me to see smartwatch distribution become standard of care for post-stroke patients, heart failure patients, and elderly patients in supervised settings. The data supporting it is solid enough, and the economics are compelling enough.

The Argument for Health Equity

There's an interesting equity dimension to this that doesn't get discussed enough.

Right now, smartwatches are a luxury good. If you have money, you can buy one and benefit from continuous health monitoring. If you don't, you don't get that monitoring. This creates a scenario where wealthy people get better early detection of health problems, leading to better outcomes, while poor people don't.

Healthcare is supposed to be equity-focused. If a technology genuinely improves outcomes and the economics work out, there's a strong case for making sure everyone has access to it, not just people who can afford $350 gadgets.

Some of the most exciting work happening right now is in low-income and middle-income countries. Distributing smartwatches in resource-limited settings could provide continuous monitoring that would otherwise require expensive frequent clinic visits. One patient wearing a smartwatch and getting monthly nurse check-ins might have better outcomes than a patient getting quarterly clinic visits and no monitoring in between.

There's also the question of social determinants. If a smartwatch helps a person with diabetes better manage their condition, reducing complications and helping them stay employed, that has economic ripple effects beyond just healthcare cost.

The equity argument isn't just moral—it's economically rational. Catching disease early in poor populations prevents expensive emergency interventions and improves long-term productivity.

Implementation Roadmap: If You Were Starting Today

If a health system decided today to launch a smartwatch distribution program, here's how they should think about it.

Phase 1: Pilot (Months 1-6)

- Target 100 to 200 high-risk patients (cardiac or post-stroke)

- Distribute Apple Watch Series 9 or equivalent

- Establish clinical workflows for alert response

- Train staff and patients thoroughly

- Track all outcomes: admissions, ED visits, alerts generated, clinical actions taken

- Measure patient satisfaction and device compliance

Phase 2: Analysis and Refinement (Months 6-12)

- Analyze pilot data for cost-benefit

- Refine workflows based on lessons learned

- Build case studies of individual patients where the device changed care

- If economics are positive, plan expansion

- Identify barriers and solutions

Phase 3: Scaled Rollout (Months 12+)

- Expand to larger patient population (500-1,000 patients)

- Build permanent staffing and infrastructure

- Integrate more fully with EHR systems

- Expand to other high-risk populations based on pilot success

- Plan for ongoing device replacement and updates

The investment in phases 1 and 2 is relatively small. The potential return in phase 3 is huge.

The Bottom Line: Health Economics Meets Practical Reality

This is one of those rare situations where doing something good for patients also happens to make strong financial sense for healthcare systems.

The research is clear: smartwatch distribution to high-risk populations prevents serious health events. The economics are clear: the prevented events cost far more than the devices. The precedent is clear: health systems that have tried this have found positive return on investment.

What's missing is scale. Most of this is still happening in pilots and limited programs. But the pilots are consistently positive, which suggests that expansion is coming.

The barriers are real but surmountable. Implementation requires planning, investment in infrastructure, and workflow changes. But none of those are impossible. They're just requiring commitment and resources.

Within the next few years, I expect smartwatch distribution to become standard of care for certain patient populations in most developed health systems. The cost-benefit math is too compelling to ignore. And once it's standard in one system, others will follow because they can't afford to be perceived as providing inferior care.

The interesting question isn't whether this will happen. It's how quickly. And whether health systems will expand beyond high-risk populations to include medium-risk patients where the economics still work but the case is slightly less obvious.

What we're really talking about is bringing preventive, continuous health monitoring out of the luxury category and into standard care. That's a significant shift. It requires rethinking some fundamental assumptions about how healthcare works.

But the data supports it. The economics support it. And an increasing number of health systems are moving toward it.

The age of smartwatches as clinical tools is starting. The data coming back from early adopters says it's going to be bigger than most people realize.

FAQ

What is the economic argument for free smartwatch distribution in healthcare?

Health systems could distribute smartwatches to high-risk patients because the prevented medical events (hospital admissions, strokes, falls) cost significantly more than the device itself. A single prevented stroke (

How do smartwatches help prevent serious health events?

Smart Watches monitor heart rhythm continuously, detecting atrial fibrillation that might otherwise go undiagnosed until a stroke occurs. They also detect falls in elderly patients, track activity levels that correlate with health deterioration, monitor sleep patterns associated with serious conditions, and send alerts that prompt timely medical intervention before emergency situations develop.

What does the clinical research show about smartwatch effectiveness?

Pilot programs show smartwatches reduce hospital readmissions by 15-25%, detect previously unknown atrial fibrillation in 4-6% of screened populations, decrease emergency department visits by 18% in some cardiac cohorts, and prevent falls in elderly patients through early alerts. These measurable outcomes translate directly into cost savings that exceed device acquisition expenses.

Which patient populations would benefit most from free smartwatch distribution?

High-risk populations like cardiac patients, post-stroke survivors, elderly patients with fall risk, heart failure patients, and type 2 diabetics on insulin show the strongest return on investment. These groups have higher prevalence of preventable events that smartwatches can detect, making the cost-benefit math most favorable and justifying health system investment.

What are the main barriers to implementing smartwatch programs in healthcare systems?

Barriers include budget silos where prevention spending and savings occur in different departments, regulatory uncertainty about how to classify consumer devices in healthcare, data governance and privacy concerns requiring infrastructure investment, clinical workflow integration challenges, and cultural resistance from administrators unfamiliar with consumer technology in clinical settings.

How accurate are smartwatches at detecting heart rhythm problems?

Apple Watch ECG features show approximately 98% sensitivity and 87% specificity for detecting atrial fibrillation compared to clinical ECG, meaning they reliably flag potential issues requiring medical confirmation. While not perfect, this accuracy level is sufficient for clinical screening purposes and triggers appropriate follow-up testing through healthcare providers.

What international health systems are already distributing smartwatches?

Several UK NHS trusts have launched pilot programs with positive outcomes, Danish and Swedish health systems are running multi-year distribution initiatives, Swiss and German insurers are subsidizing watches for specific populations, and some major U.S. health systems like Mayo Clinic have begun targeting high-risk patients. Data from all programs shows positive cost-benefit results.

How do smartwatches integrate with existing electronic health records?

Integration varies by health system and device, but newer implementations involve automatic data transmission to EHRs, clinical dashboards showing smartwatch alerts alongside patient records, and alerts triggering appropriate clinical workflows. Successful implementations invest in integration infrastructure rather than requiring clinicians to check separate apps, making smartwatch data part of standard clinical documentation.

What happens when a smartwatch detects a problem?

When a device flags an issue like irregular heart rhythm or a fall, the patient receives a notification encouraging them to seek medical attention or contact their healthcare provider. The alert is logged, may be transmitted to clinical staff depending on the program design, and prompts appropriate medical evaluation—ECG, specialist consultation, or emergency response depending on severity and patient instructions.

Could smartwatch distribution ever become standard healthcare practice?

Within five years, smartwatch distribution will likely become standard of care for post-stroke patients, heart failure populations, and elderly patients in supervised settings based on current economic and clinical evidence. As regulatory frameworks clarify and integration with EHRs improves, expansion to additional populations is probable, potentially making continuous monitoring via wearables a routine component of chronic disease management.

Key Takeaways

- Smartwatch distribution to high-risk patients costs 5,000-45,000, achieving ROI within months

- Pilot programs show 15-25% reductions in hospital readmissions and detection of atrial fibrillation in 4-6% of previously undiagnosed patients

- Cardiac patients, post-stroke survivors, diabetics, and elderly populations benefit most where prevalence of detectable preventable events is highest

- International health systems in UK, Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland are already running successful pilots with positive cost-benefit data

- Implementation barriers are organizational and workflow-related rather than technical, requiring integration with EHRs and clinical protocols

Related Articles

- PraxisPro's $6M Seed Round: AI Coaching for Medical Sales [2025]

- Serve Robotics Acquires Diligent: Why Healthcare Robots Are the Next Frontier [2025]

- Whole-Body MRI Screening: Why Doctors Question Elective Scans [2025]

- The 11 Biggest Tech Trends of 2026: What CES Revealed [2025]

- Noninvasive Blood Glucose Monitors: The Wearable Breakthrough [2025]

- ChatGPT Health: How AI is Reshaping Medical Conversations [2025]

![Apple Watch Distribution for Free by Health Services: Could It Save Lives? [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/apple-watch-distribution-for-free-by-health-services-could-i/image-1-1769181114656.jpg)