How Social Media Distorts Geopolitics: The Venezuela Crisis Reality

Geopolitics used to unfold at the pace of diplomacy. Governments would gather, statements would be carefully crafted, and the world would absorb the implications over days or weeks. You'd read about it in the newspaper, hear it on evening news broadcasts, maybe discuss it around the dinner table.

Now, a US military intervention in a Latin American country becomes a Tik Tok narrative before the initial reports have even been verified. Within hours, not days, social media has constructed its own reality. Side A has already won the discourse. Side B has already mobilized its counternarrative. The actual facts? They're fighting for attention somewhere in the middle, losing ground by the minute.

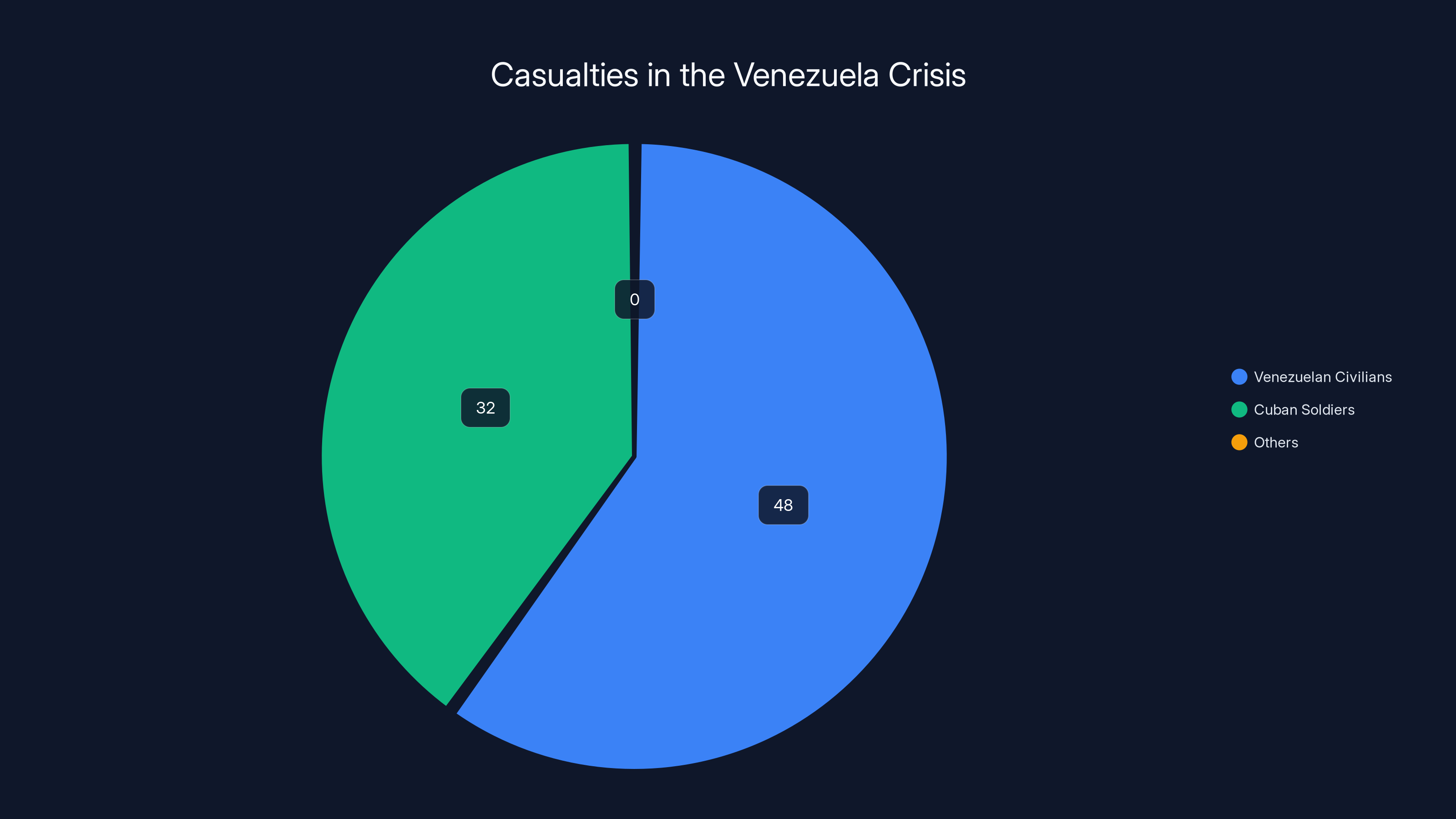

On January 3, the United States launched a military intervention in Venezuela. Sky thundered over Caracas with explosions. At least 80 people died, though the full death toll remains contested. The sitting president, Nicolás Maduro, was captured and transported to the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn. Cuban president Miguel Díaz-Canel confirmed that 32 Cuban soldiers died in combat. And yet, for millions of people scrolling through their phones, none of that felt quite real. What felt real were the competing narratives, the memes, the 60-second video explainers, the influencer takes.

This is not a simple story about misinformation. This is about something far more fundamental: the collapse of shared reality itself. When social media platforms become the primary source through which billions of people understand geopolitics, something breaks. Our collective ability to comprehend complicated international events, to sit with complexity, to defer judgment until facts are gathered—that capacity atrophies.

The question haunting journalists, researchers, and policymakers isn't whether social media spreads false information. We already know that. The harder question is this: What happens when the medium itself makes truth almost irrelevant?

TL; DR

- Geopolitical complexity collapses into 60-second social media videos that prioritize emotional resonance over accuracy

- Verification takes hours; virality takes minutes, creating a reality where false narratives spread faster than corrections

- Influencers now shape global understanding of military interventions, with algorithmic amplification replacing journalistic gatekeeping

- Polarization weaponizes nuance, where legitimate critiques of US interventionism become ammunition for authoritarian regimes

- Democratic discourse erodes when citizens form opinions about international affairs through algorithm-optimized content rather than reported facts

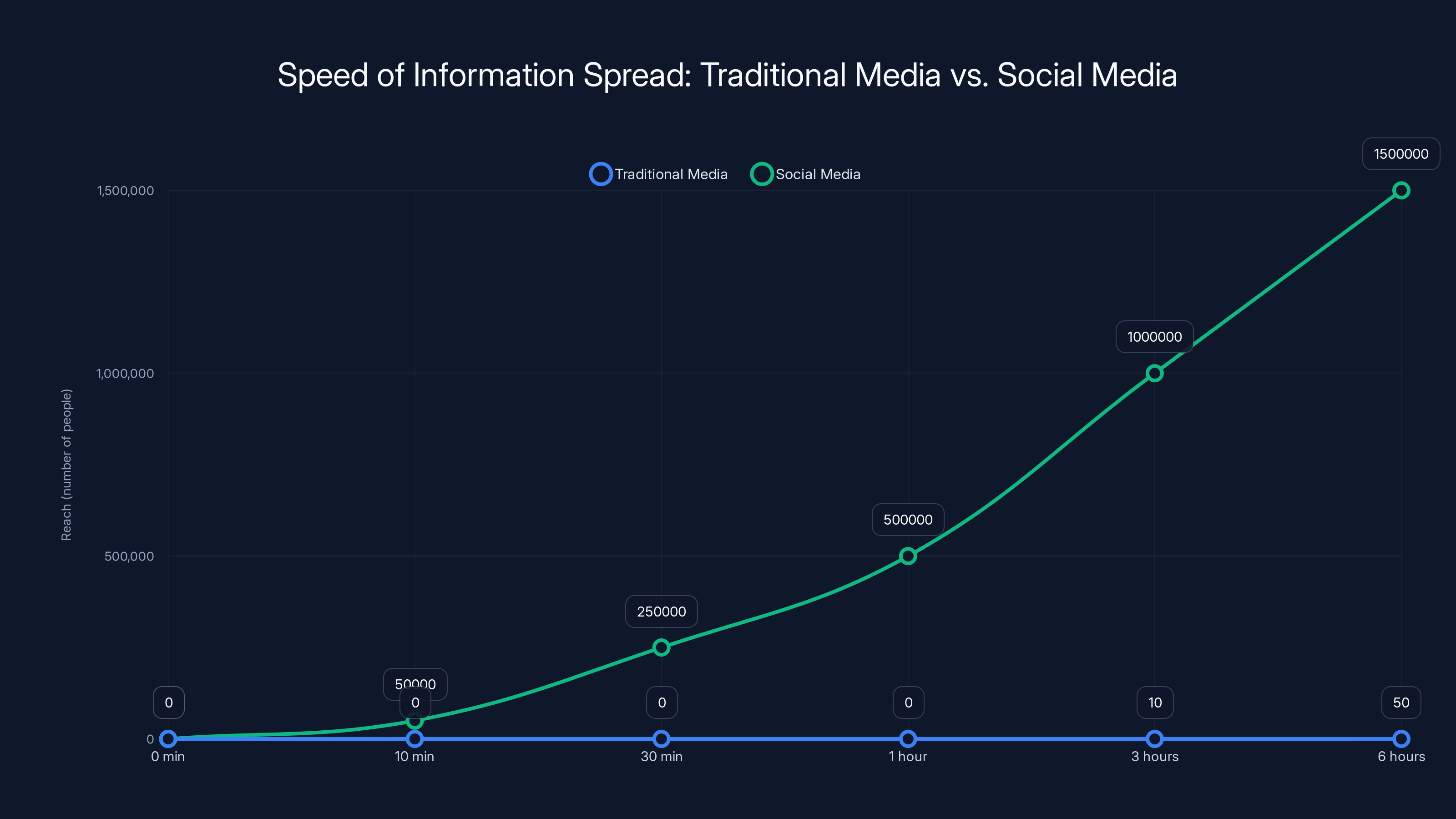

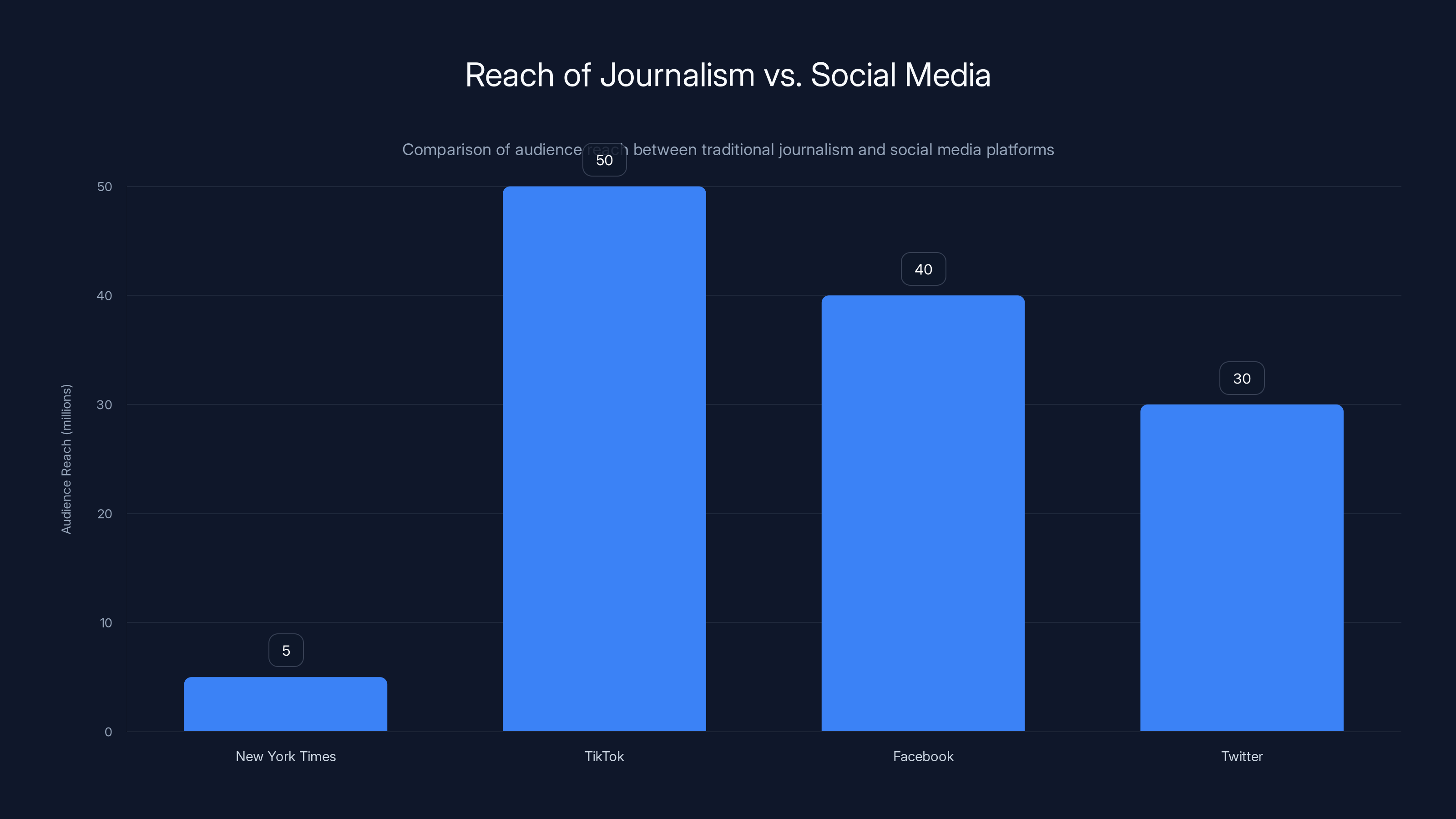

Social media can reach millions within hours, while traditional media takes longer to verify and disseminate information. Estimated data highlights the disparity in speed.

The Speed Problem: Why Minutes Beat Hours

There's a mechanical truth at the heart of modern media: the speed of verification versus the speed of spread. This isn't new, but it's become catastrophic.

Traditional journalism operates on a verification timeline. A reporter receives information. They contact sources. They seek comment from relevant parties. They check facts against existing reporting. They run the story past editors. This process takes hours, sometimes days. For complex geopolitical events involving multiple countries, military operations, and unclear casualty figures, this timeline makes sense. You need time to actually understand what happened.

Social media operates on a different timeline entirely. Someone records a video, types a caption, hits post. If the algorithm likes it, 50,000 people see it in minutes. If they engage, 500,000 see it within the hour. By the time fact-checkers have even identified the claim worth investigating, the narrative has already colonized the minds of millions.

Julio Juárez, a psychological researcher at UNAM, describes this as the complete inversion of information flow. "The time that traditional media needed to verify information has been devoured by the speed of social media platforms," he explains. "From the first reports of the attack on Venezuela, social media operated as a massive amplifier that not only transmitted different perspectives but also constructed reality."

Notice the language: not just transmitted perspectives, but constructed reality. This is the subtle horror. On social media, you're not passively receiving information. You're watching reality being built in real-time through competing narratives, each vying for algorithm superiority.

When the Venezuela intervention happened, here's what actually occurred on the ground: Complex military operations with unclear objectives. Civilian casualties mixed with military casualties, with disputed numbers from different sources. International law questions that remain genuinely unresolved. Reasonable people disagreeing about whether the intervention was justified, effective, or legal.

Here's what social media said happened: About 47 different versions of events, each packaged for maximum emotional impact and minimum nuance. Some showed the US as saviors. Others showed the US as imperial aggressors. Few showed the genuine uncertainty about what was really happening. Why? Because uncertainty doesn't algorithm well.

The mechanical problem is this: Truth is complicated. Lies are simple. Algorithms reward engagement. Engagement comes from emotional response. Complexity doesn't generate emotion. Certainty does. Therefore, algorithms will always accelerate the spread of false certainties over true ambiguities.

This creates a systematic bias that no amount of fact-checking can overcome. A fact-check saying "the true death toll is unclear pending investigation" will never compete with a confident claim: "the death toll was exactly X." The first is true. The second is engaging. Social media will amplify the second.

The Narrative Arms Race: How Competing Realities Emerge

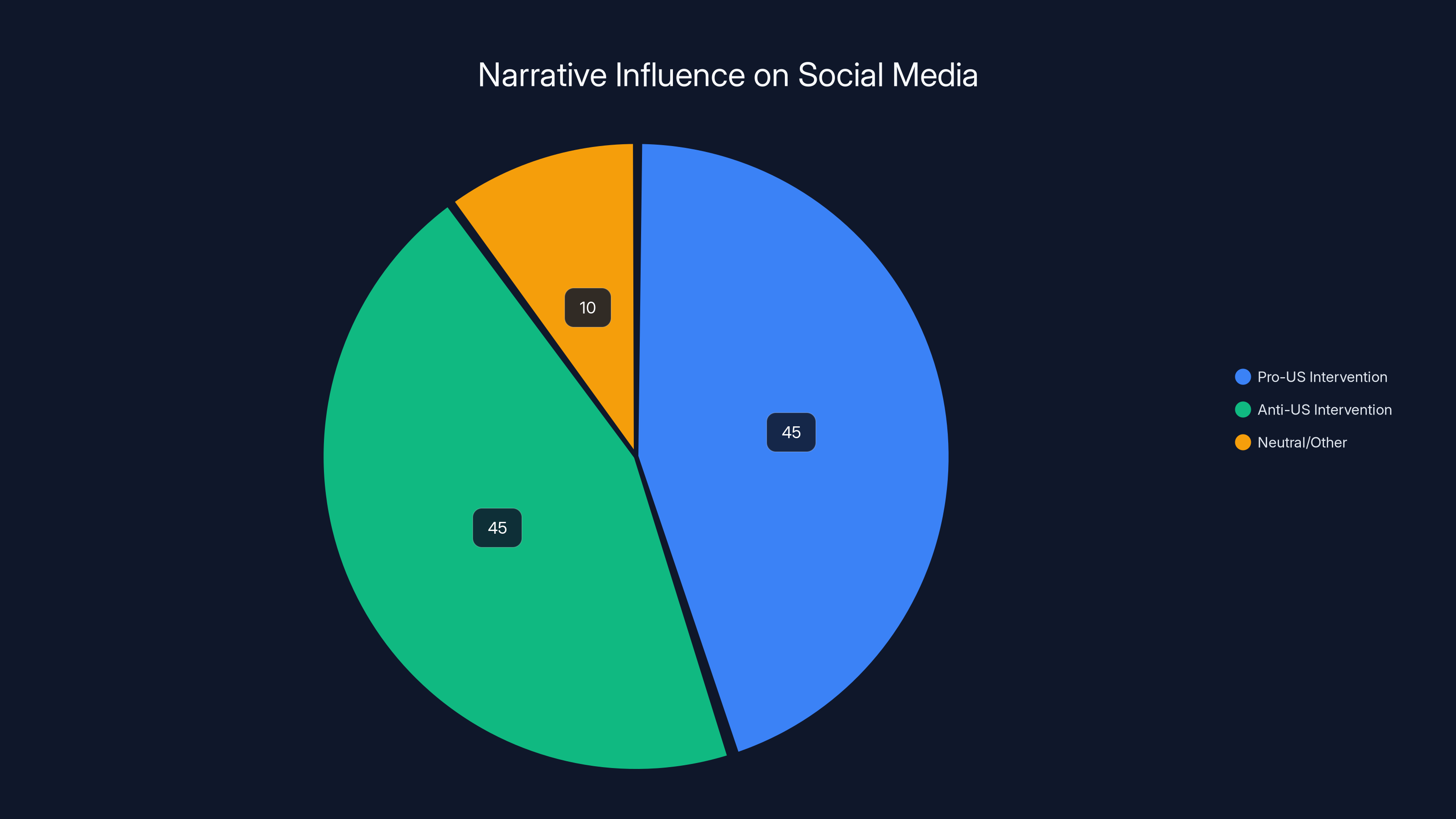

Two opposing narratives emerged about the Venezuela intervention, and neither is entirely fabricated. Both contain kernels of truth. Both are presented through carefully curated selective facts. And both gained enormous reach through social media amplification.

The first narrative went something like this: Venezuela had descended into authoritarian dictatorship under Nicolás Maduro. Human rights were systematically violated. Elections were stolen. The economy was destroyed. Millions fled as refugees. The US intervention was justified as humanitarian intervention to restore democracy and human rights. When you frame it this way, the operation looks like the rescue mission the White House described.

The second narrative told a different story: The United States has a 200-year history of military interventions in Latin America, almost always claiming humanitarian justification, almost always benefiting US economic interests while destabilizing entire regions. This Venezuela intervention fits that historical pattern perfectly. The US immediately claimed that American oil companies would revive Venezuelan oil production. The real motivation wasn't democracy; it was resource extraction. When you frame it this way, the operation looks like colonial resource theft dressed in humanitarian language.

Here's the problem: Both narratives contain true elements. The Maduro regime did commit documented human rights abuses. That's verified by multiple international human rights organizations. The US does have a historical pattern of Latin American interventions that destabilized regions and enriched American corporations. That's also historically documented.

But on social media, you don't get "both of these things are true." You get forced to pick a side. The algorithm shows you content that confirms your existing leaning. If you already distrust the US, you'll see content about historical interventions and corporate resource extraction. If you already support the intervention, you'll see content about Maduro's authoritarian abuses. Within 48 hours, you've constructed a complete worldview that makes you immune to contradictory facts.

Rafael Uzcategui, a sociologist and human rights researcher in Caracas, watched this happen with growing frustration. "I'm bothered by the misunderstanding and biased narratives that people, for ideological reasons, continue to impose from outside," he told reporters. "We've made a great effort to work with international human rights institutions, whose reports have provided an important diagnosis, which is public and easily accessible, of the deterioration of the situation."

He had actually done the work. He'd studied the situation on the ground. He'd coordinated with international human rights organizations. He had documented evidence. And yet, none of that mattered in the social media discourse, because documented evidence doesn't spread as fast as emotional narratives.

Tecayahuatzin Mancilla, the creator behind a popular Spanish-language Instagram account about history and geopolitics, posted a satirical video showing Mexico celebrating New Year while the US boasted about bombing Venezuela "for the sake of world security." The point was clear: American exceptionalism. The world is America.

It was clever. It was funny. It resonated with millions of people instantly. It also flattened genuine complexity into comedy. Was the US intervention motivated by humanitarian concerns or resource extraction? According to the video, the answer was obvious: American empire. But the real answer is more complicated.

This is the narrative arms race. It's not that malicious actors are creating falsehoods. It's that the medium itself rewards oversimplification. Whoever can package complexity into the most emotionally compelling 60-second narrative wins the algorithm. Not wins at truth-telling. Just wins.

Estimated data shows both pro and anti-US intervention narratives have equal reach on social media, with a small portion remaining neutral or exposed to both sides.

Why Fact-Checking Fails at Scale

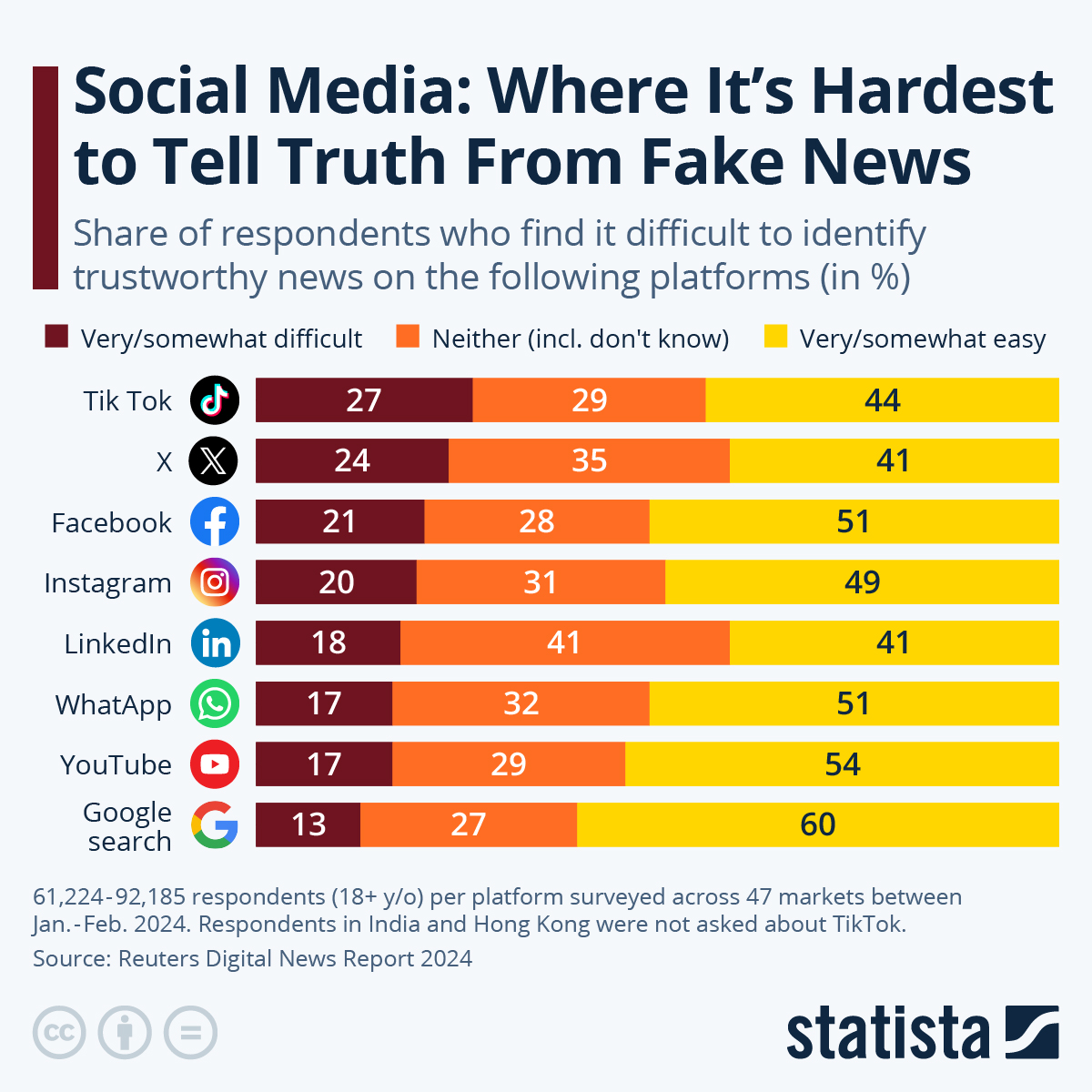

Fact-checkers work overtime during major geopolitical crises. They're trying to verify claims, catch demonstrable falsehoods, provide corrections. It's noble work. It's also nearly useless at scale.

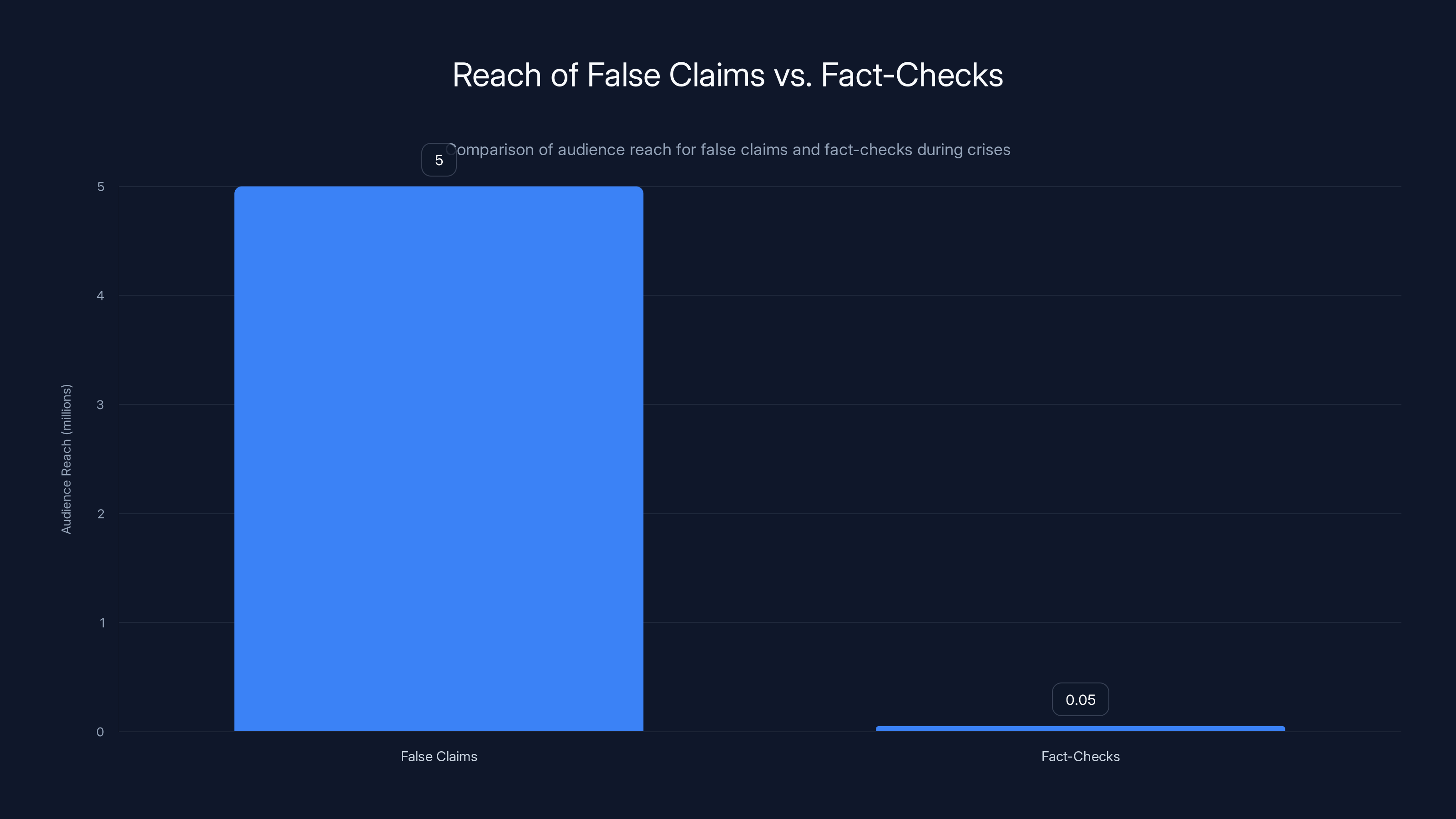

Here's why: A false claim about Venezuela spreads to 5 million people on Tik Tok. A fact-check is published on a dedicated fact-checking website. Maybe 50,000 people see it. That's a 1% reach ratio. But worse: The 50,000 people who see the fact-check are disproportionately people who already distrust the original false claim. You're preaching to the converted.

The 5 million people who believed the false claim? Most never see the correction. And of the ones who do, studies show they don't actually update their beliefs. The original false claim forms a kind of mental framework. Corrections don't dismantle the framework; they just create cognitive dissonance that people resolve by dismissing the correction.

This is called the "backfire effect," though researchers debate how often it actually occurs. But the core principle is sound: Once you've believed something, evidence against it doesn't just fail to convince you. It can make you believe it more strongly.

On social media, this becomes a systemic problem. Misinformation isn't a bug; it's a feature of the architecture. The platform doesn't make money from truth. It makes money from engagement. False claims that trigger emotional response—anger, outrage, fear—generate more engagement than true claims that generate confusion or ambivalence.

So even if Facebook or Tik Tok wanted to prioritize truth-telling, the business model works against them. A platform that said "this is complicated, be skeptical" would lose users to a platform that said "this is simple, here's the truth." The incentive structure is fundamentally misaligned with accuracy.

During the Venezuela crisis, fact-checkers tried to verify specific claims: casualty figures, details about Maduro's capture, whether certain videos were authentic. All important work. But they were playing defense against an opponent with infinite offense. Every video that got fact-checked was replaced by three new false claims. It was whack-a-mole with unlimited moles.

The real problem isn't fact-checkers' failure. It's that fact-checking was always a reactive solution to a structural problem. You can't fact-check your way out of an algorithm designed to reward engagement over accuracy. The platform would have to change. And the platform makes too much money from the current system to change.

The Influencer Problem: When Credibility Becomes Arbitrary

You know who has credibility on social media? The person with the biggest following. That's literally it. It doesn't matter if you've studied international law for 20 years. It doesn't matter if you've covered geopolitical crises in person. What matters is if you have 2 million followers.

This is the influencer problem. Social media has inverted the credibility hierarchy. Traditional experts—historians, lawyers, journalists, diplomats—have been replaced by... anyone with a large following. Some influencers are thoughtful and knowledgeable. Many are not. The algorithm doesn't distinguish.

During the Venezuela crisis, geopolitical takes from Tik Tok creators with millions of followers were treated with the same credibility as analysis from actual experts. Actually, worse. The expert analysis was read by maybe 100,000 people. The influencer take was seen by 10 million. The influencer won the credibility game not through superior knowledge but through superior reach.

This creates a weird inversion where the most confident voice wins, regardless of accuracy. An influencer confidently stating that the US intervention was about oil expansion reaches more people than a careful analysis explaining that US motivation was mixed: partly humanitarian concern, partly resource interests, partly geopolitical positioning against China and Russia. The mixed answer is more accurate. The confident answer wins.

And here's the thing: Influencers aren't necessarily lying. They're just optimizing for what works. They've learned—from thousands of posts and millions of engagements—that audiences respond to clarity and confidence. Nuance is engagement poison. So they deliver clarity, even when the situation demands nuance.

A 22-year-old Tik Toker with 3 million followers can say "the US is invading Venezuela for oil" with absolute certainty. A 60-year-old geopoliticist with 40 years of experience says "the situation is complex and the motivations are mixed." Who's more credible? On social media, the first person, every time.

This is catastrophic for democratic discourse about geopolitics. Because geopolitics actually requires expertise. It requires historical knowledge, understanding of international law, knowledge of the countries involved, awareness of economic flows and strategic interests. This can't be conveyed in 60 seconds. But that's the medium everyone's using.

The influencer ecosystem doesn't require expertise. It requires an audience. And audiences are attracted to confidence, not accuracy. This creates a selection effect where the most charismatic liars outcompete the most careful truth-tellers.

It's not that influencers are deliberately spreading propaganda. Many genuinely believe what they're saying. They've just optimized their thinking for what algorithms reward. They've become expert at expressing opinions with confidence, at framing issues in emotionally resonant ways, at identifying their audience's existing biases and reflecting them back, amplified.

The Polarization Paradox: How Criticism Becomes Ammunition

Here's where it gets strange. Some of the social media criticism of the Venezuela intervention was legitimate. The US has invaded Latin American countries before. US military interventions have destabilized regions. American oil companies have benefited from previous Latin American conflicts. These are historical facts. They're important context.

And yet, these legitimate historical critiques were weaponized. Because social media doesn't distinguish between "the US has done this before, so we should be skeptical" and "therefore this intervention is wrong." It collapses legitimate context into ideological ammunition.

Meanwhile, the Maduro regime—an authoritarian government that had documented human rights abuses, that had stolen elections, that had destroyed the economy—got defended by people who cared more about opposing American imperialism than about actual Venezuelan human rights. Not because the people defending Maduro were defending authoritarianism, but because social media forced them to pick a tribe. If you were anti-US-intervention, you ended up defending Maduro. If you were pro-intervention, you ended up defending what might be imperial resource extraction. The nuance got obliterated.

A Venezuelan named Dayani López replied to the satirical video with raw honesty. "Where was the concern for international law when Maduro violated our human and civil rights year after year? Where were those laws when they starved us, killed our students for protesting peacefully? Where were YOU during those 25 years when we were crying out for help?"

Her critique was cutting precisely because it was true. Venezuelan citizens had been suffering under an authoritarian regime. The international community had largely ignored them. Now that the US intervened, suddenly international law and humanitarian concerns mattered. But only in this moment. Only for this intervention. It felt hypocritical.

And it was. But the social media discourse didn't allow for that complexity. You couldn't simultaneously say: "US interventions have caused problems historically AND Maduro's authoritarianism needed to be addressed AND we should be skeptical about American motives AND Venezuelan human rights matter." All of that is true. Social media doesn't have room for it.

Instead, you had to choose: You're either defending Maduro and ignoring Venezuelan suffering, or you're defending US intervention and ignoring historical imperialism. The polarization wasn't created by outside bad actors. It was created by the medium itself, which rewards those who take the clearest possible position.

This is how social media corrupts even legitimate discourse. It's not that the criticism of US imperialism was wrong. It was right. But the medium didn't allow that rightness to exist alongside other truths. So people ended up in tribes based on what Tik Tok and Twitter algorithms showed them, not based on actual analysis of what was happening.

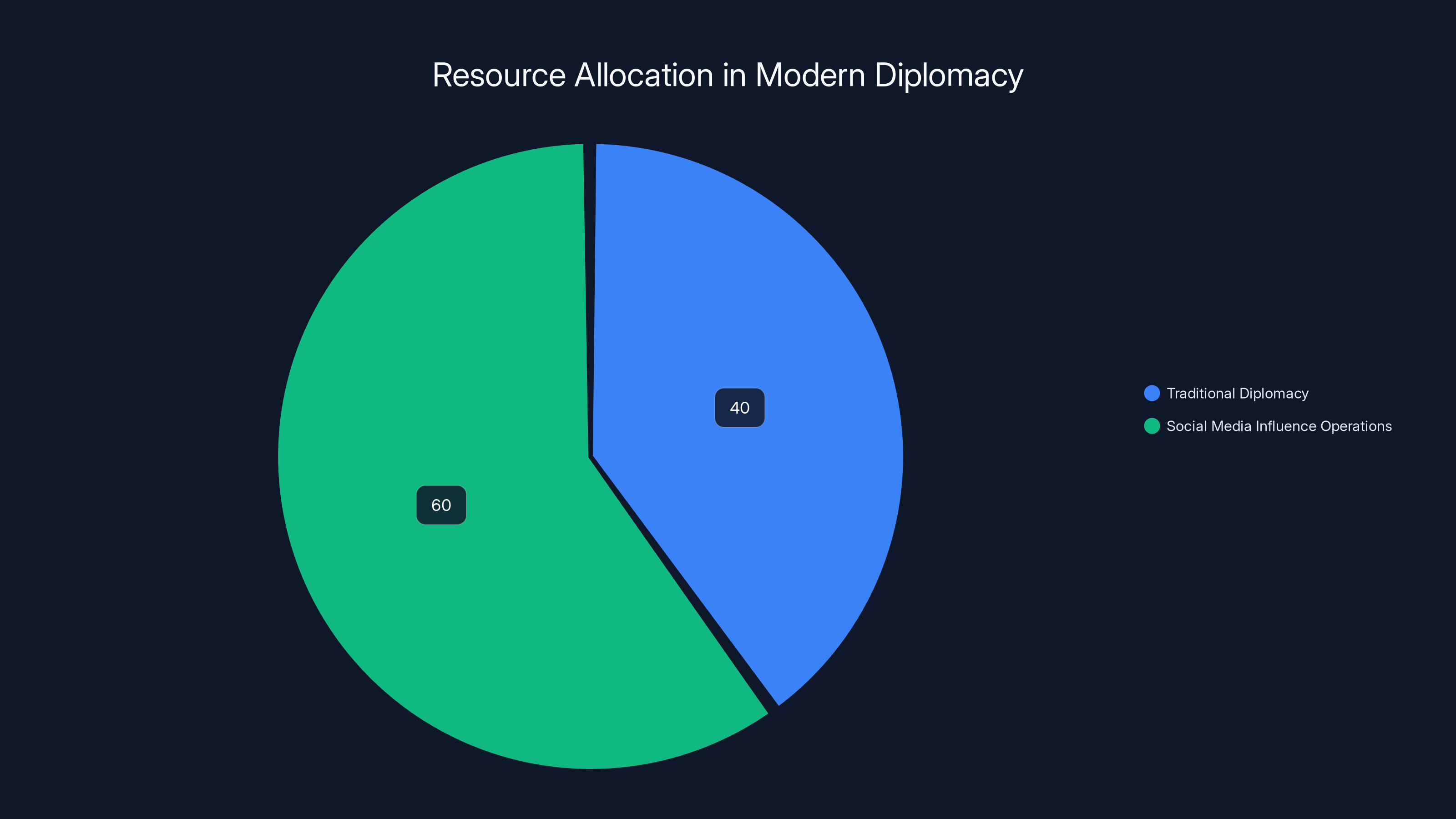

Estimated data shows a shift towards social media influence operations, with 60% of resources now allocated to this area, reflecting its growing importance in modern diplomacy.

The Information Asymmetry Problem

Here's a structural problem with social media discourse about international events: Information asymmetry. Some people have access to better information. Some people are on the ground and have direct knowledge. Some people have spent 20 years studying a region. Some people got their information from a Tik Tok video posted by someone they've never heard of.

All of these people are given equal voice on social media. Actually, the person with the Tik Tok video has more voice, because the algorithm prefers short, clear, emotionally engaging content.

Rafael Uzcategui had spent years documenting human rights abuses in Venezuela. He'd worked with international organizations. He'd collected evidence. His analysis should have been authoritative. And yet, on social media, it competed for attention with influencers who had no specialized knowledge but had massive followings.

This isn't a problem that can be solved by better fact-checking or media literacy. It's a structural problem with the medium. The platform doesn't care whether you know what you're talking about. It cares whether people click, like, and share. If a 19-year-old makes a funny video about geopolitics that goes viral, they now have more credibility on the platform than a 50-year-old expert who studied the situation extensively.

This creates a world where geographic proximity to events, expertise, and actual knowledge matter less than entertainment value. A Venezuelan refugee in Miami has less social media influence than a You Tuber in California who's never been to Venezuela but has a big following.

The cost of this information asymmetry is massive. When it comes to understanding what's happening in your own country, you have to compete for attention on social media with people who don't know what they're talking about but who are better at generating engagement.

This is why coverage of the Venezuela crisis was so distorted. The people with the best information—people on the ground, regional experts, historians, human rights researchers—had less reach than influencers playing to pre-existing biases and generating emotional reactions.

The Temporal Collapse: When History Gets Forgotten in Real Time

Social media exists in an eternal present. Tik Tok doesn't have archives. Twitter threads disappear into the feed. Yesterday's viral video is replaced by today's viral video. This creates a weird temporal condition where historical context gets lost constantly.

When the US intervened in Venezuela, social media immediately brought up the history of US interventions in Latin America. That's important context. But because social media has no memory, it presented this context without the full historical picture.

The full picture looks like this: The US intervened in Guatemala in 1953, overthrowing a democratically elected government and installing a dictatorship that lasted 30 years, resulting in 200,000 deaths. The US intervened in Chile in 1973, helping overthrow a democratically elected government and installing a dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, resulting in 3,000 documented deaths. The US invaded Panama in 1989, ostensibly to capture a drug trafficker, actually to reassert US hegemony over the Panama Canal. These are real historical events.

And yet, what's interesting is that these interventions are not all equivalent morally. Some overthrew elected governments. Some attempted to remove authoritarian dictators. Some were driven purely by resource extraction. Some had mixed motives. The historical pattern is real, but it's more complex than "the US always intervenes in Latin America."

Social media compressed this into a simple narrative: The US has always intervened in Latin America, therefore this intervention is bad. But a fuller historical understanding would say: The US has intervened in Latin America with mixed results and mixed motives. We should be skeptical but not cynical. We should demand transparency about actual motives. We should evaluate this specific intervention on its specific merits while being aware of historical precedent.

That's not something that works in social media's temporal economy. You can't say "this is complicated and historically contingent" when you have 60 seconds before the algorithm stops showing people your video.

So the temporal collapse creates a kind of historical amnesia combined with pattern-matching paranoia. People remember that US interventions have been bad historically, but they don't remember the variations. So they assume this one will be bad too. But that assumption, though historically informed, might not actually be correct for this specific case.

The Engagement Economy and Truth Decay

Let's be very clear about something: This isn't an accident. This isn't a bug that platforms haven't figured out how to fix. This is working exactly as designed.

Social media platforms make money from engagement. Engagement means people spending time on the platform, clicking, scrolling, interacting. The algorithm learns what generates engagement and amplifies it. False information that triggers emotional response generates engagement. True information that creates confusion does not.

This is the core problem. Not incompetence. Not a few bad actors spreading propaganda. Not insufficient fact-checking. It's that the business model is fundamentally misaligned with truth-telling.

Consider the incentives: If you're a social media platform, what makes you more money?

A video explaining that Venezuelan casualties are unclear pending investigation, with detailed sourcing and academic caution, or a video confidently stating the exact casualty figure?

Obviously, the confident version. Engagement. Shares. Comments from people who agree or disagree. The algorithm favors it. You show it to more people. Those people generate more engagement. Your ad revenue goes up.

No platform executive wakes up and says, "Let's make sure misinformation spreads faster than truth." They don't have to. The system does it automatically. The engagement incentive creates truth decay as an emergent property.

This is why every effort to moderate content, every fact-check, every policy change, ultimately fails. You can't fact-check your way out of a fundamentally broken incentive structure. You can't add more moderators when the algorithm itself rewards engagement over accuracy. You're trying to patch a system that's broken by design.

The Venezuela crisis perfectly illustrated this. Every false claim that spread was an engagement win. Every true claim with nuance and uncertainty was an engagement loss. The platform didn't need propaganda spreaders. The truth-decay happened naturally.

Social media platforms like TikTok have a significantly larger reach compared to traditional journalism outlets like the New York Times. Estimated data highlights the disparity in audience size.

The Democratic Deficit: When Voters Don't Understand What They're Voting About

Here's where this becomes genuinely dangerous for democracy: In many countries, public opinion matters for foreign policy. If Americans understood what the US military was doing in Venezuela, they might demand transparency or congressional approval. If they actually knew the details, they might have different opinions.

But they don't understand, because their understanding comes from social media. They have a sense that something happened, they have strong emotional reactions, they have opinions. But these opinions are constructed from algorithm-optimized snippets, not from actual information.

This creates a democratic deficit. The public has lost the ability to actually understand foreign policy. They can react emotionally. They can express political preference. But they can't actually comprehend what's happening or why.

A well-functioning democracy requires informed citizens. Not experts, just informed. People who know basic facts, who understand context, who can change their minds when presented with new evidence. Social media systematically undermines every one of these requirements.

It's not just about Venezuela. It's about every international event that shapes the world. Climate change. Trade policy. Military deployments. Refugee crises. Pandemics. All of these are understood by most people almost entirely through social media distortions.

The result is a public that's engaged but uninformed, passionate but confused, certain but wrong. They're certain about things that are actually complicated. They're confused about things that are actually simple. This is worse than indifference. This is worse than lack of knowledge.

At least indifference doesn't vote against its own interests based on misinformation. At least lack of knowledge doesn't opine confidently about things it doesn't understand.

The Solutions Problem: Why Easy Answers Don't Work

Everyone has solutions. Make fact-checking faster. Add media literacy education. Regulate social media platforms. Require sources. Build alternative platforms. Breakup Big Tech. All of these ideas have merit. None of them actually solve the problem.

Faster fact-checking? Doesn't matter when false claims spread six times faster than corrections.

Media literacy education? Good to have, but you can't educate your way out of a system designed to manipulate. It's like teaching people to resist hypnosis while surrounding them with hypnotists.

Regulating platforms? Governments are bad at regulating technology. And platforms operate internationally, so what does regulation even mean?

Requiring sources? People don't read sources. They read headlines and engage with conclusions.

Building alternative platforms? If the alternative platform doesn't have massive reach, it solves nothing. And if it does achieve scale, why would it operate differently? It has the same business model.

Breakup Big Tech? Maybe. But if you break up Facebook, you get 47 smaller social media companies, each optimizing for engagement over accuracy. Is that better?

The real problem is structural. The medium itself—short-form video, algorithm-driven distribution, engagement incentives, temporal collapse, influencer dynamics—creates conditions where truth struggles to survive. You can't fix this with tweaks. You'd need to redesign the medium entirely.

What might that look like? Platforms optimized for understanding rather than engagement. Platforms where slow, thoughtful content is amplified. Platforms where experts have more reach than influencers. Platforms where false information gets suppressed even if it's engaging. Platforms where you see historical context alongside current events. Platforms where nuance is rewarded.

No such platform exists. Because such a platform would have lower engagement, less ad revenue, and would lose users to platforms that are more entertaining. The incentive structure works against it.

What Happens When Geopolitics Becomes Content

Here's the deeper problem: Geopolitics has become content. It's not something governments do in private, that journalists cover, that citizens learn about. It's entertainment. It's engagement. It's a commodity for social media platforms.

This changes the nature of geopolitics itself. Decisions get made not just based on strategy but on how they'll play on social media. Narratives matter more than outcomes. Optics are managed more carefully than operations. The geopolitical decision-maker now has social media engagement as an objective alongside traditional objectives like military advantage or diplomatic leverage.

Donald Trump understood this better than any other modern political leader. He didn't just use social media as a channel. He understood that the messaging was the strategy. A military intervention in Venezuela could be positioned as righteous intervention or imperialist resource extraction, depending on the narrative. The narrative was partly independent of reality. It could be shaped.

So governments now operate in a world where actual facts matter less than the social media narrative about facts. A casualty number is less important than what influencers say about the casualty number. An objective is less important than whether it polls well on Twitter. A military victory is less important than whether it generates positive engagement.

This is new. This is genuinely dangerous. Because geopolitical decisions based on what's engaging are not good decisions. They're decisions that prioritize spectacle over strategy. They're decisions that work if the audience is passive. They fail catastrophically if the audience gets to vote or if reality intrudes.

The Venezuela intervention seemed popular on social media. But did it accomplish its stated objectives? Is the region more stable? Is democracy being restored? Is humanitarian crisis improving? These are harder questions than "does this generate engagement." But these are the questions that actually matter.

Social media has inverted the importance hierarchy. Engagement now matters more than outcomes. The narrative now matters more than reality. The 60-second video now shapes policy more than expert analysis.

The tragedy is that this is working exactly as the medium designed it. No one did anything wrong, from the platform's perspective. Everything is functioning optimally. It's just that optimal functioning of social media engagement mechanics is catastrophic for informed democratic discourse about geopolitics.

False claims reach 5 million people, while fact-checks reach only 50,000. This 1% reach ratio highlights the challenge of correcting misinformation at scale. Estimated data.

The International Implications: When Misinformation Becomes Diplomacy

The Venezuela crisis demonstrated something that geopolitical analysts are still grappling with: Foreign governments now pay attention to social media narratives almost as much as they pay attention to traditional diplomatic channels.

When a narrative goes viral suggesting that an intervention is about resource extraction rather than humanitarian concern, the government that launched the intervention has to spend political capital responding. The false narrative becomes a real problem, not because people believe it, but because it shapes international opinion, domestic political support, and future diplomatic relationships.

This means that spreading false narratives about geopolitical events is now a form of power projection. If you can seed narratives on social media that make another country look bad, you've scored a diplomatic victory. You don't need to prove your narrative is true. You just need to make it engaging enough to spread.

Countries are starting to understand this. They're allocating resources to social media influence operations. They're hiring people who understand algorithm optimization. They're creating content designed to go viral. It's warfare, but the battlefield is engagement metrics.

Meanwhile, traditional diplomacy, which used to happen between governments through formal channels, is increasingly happening between narratives on social media. The formal diplomatic statement says one thing. The social media narrative says another. And increasingly, the social media narrative is what matters, because that's what shapes how citizens understand the event.

This creates a new vulnerability for democracies. Because social media is harder to defend against than traditional propaganda. Traditional propaganda came from identifiable sources. You knew it was propaganda. Social media engagement comes from distributed sources, from influencers, from regular citizens. It looks organic. It's harder to identify and counter as foreign interference.

The Venezuela crisis showed this in real time. Which narratives were organic? Which were promoted by foreign governments? Which were promoted by US interests? Which were genuinely reflections of actual analysis? Almost impossible to tell. The signals are too mixed.

The implication is troubling: In a world where geopolitics is conducted through social media, the country with the best narrative wins, not the country with the best strategy. This advantages countries good at information manipulation and disadvantages countries committed to truth-telling. It's a race to the bottom in terms of intellectual honesty.

Why Journalists Can't Solve This Alone

There's a temptation to believe that better journalism can fix this. If newspapers just did better reporting, if investigative journalism was better funded, if fact-checkers were more prominent, surely we could counter the social media distortion.

It's a comforting belief. And it's wrong.

The problem isn't journalism quality. Many news organizations do excellent reporting on the Venezuela situation. The problem is reach and engagement. Excellent reporting in the New York Times reaches 5 million people. A false claim on Tik Tok reaches 50 million. The journalist can be right and still lose the discourse.

More fundamentally, journalism operates on a different principle than social media. Journalism is about establishing facts through reporting and sourcing. Social media is about generating engagement. These are opposing incentive systems. You can't use one system to defeat the other.

A journalist writes: "Casualty figures remain unclear. Various sources report different numbers. Investigation is ongoing."

Tik Tok says: "The death toll was exactly 47."

The journalist is more accurate. Tik Tok gets more engagement. Who wins the discourse? Tik Tok. It's not a fair fight because they're not fighting on the same terms.

Journalists can report accurately. They can provide context. They can do their jobs excellently. But unless traditional journalism regains reach parity with social media, facts will continue to lose to engagement.

This is why the problem can't be solved through journalism alone. Journalism can be excellent. Journalism can be accurate. But if the public gets information primarily through social media, then excellent journalism is fighting with one hand tied behind its back.

The real solution would be structural: Making traditional journalism more prominent again. Funding investigative reporting. Making social media less prominent in the information ecosystem. But these are political questions, not journalistic questions.

The Audience Problem: We Want Stories, Not Facts

Here's the uncomfortable truth that no one wants to admit: People prefer narratives to facts. We're storytelling creatures. We don't just want to know what happened. We want to know what it means. Why did it happen? What does it tell us about good and evil? Where do we fit in the story?

Social media understands this. It gives us stories. Clear stories with heroes and villains, with beginning and end, with moral clarity. Facts are boring and ambiguous. Stories are engaging and clear.

A fact: "The US military intervened in Venezuela, capturing the president."

A story: "The mighty American empire once again strikes at a small country to steal its resources, showing that international law means nothing to those with power."

Another story: "Democratic forces finally liberate Venezuela from the tyrant Maduro, showing that freedom and justice ultimately prevail."

Both are stories. Neither is entirely true. But both feel true because they're emotionally coherent. The facts are ambiguous. The stories are clear. People want the stories.

This is partly a human problem, not a media problem. We're built to think in narratives. We evolved to understand the world through stories. It's not a failure of our cognition. It's just how human brains work.

But social media exploits this. It's engineered specifically to give us the narrative-driven content we naturally crave. It removes friction from the storytelling process. It amplifies the clearest stories. It removes the voices arguing for ambiguity.

You can't solve this through fact-checking or better information, because the problem isn't information. The problem is that facts feel unsatisfying compared to stories. A person who understands the Venezuela situation completely would still find that understanding unsatisfying compared to a clean narrative.

The intervention resulted in at least 80 casualties, with 32 Cuban soldiers confirmed dead. Estimated data.

What Informed Democratic Discourse Actually Requires

If you want citizens to understand geopolitical events and form informed opinions, here's what you actually need:

First, time. You need time to gather information, to think about it, to hear multiple perspectives, to let initial reactions settle. Social media compresses this to seconds.

Second, expertise. You need access to people who actually know what they're talking about. Not experts who tweet, but experts who write long pieces explaining their thinking. Social media surfaces influencers, not experts.

Third, context. You need historical knowledge and regional understanding. You need to know how this situation connects to previous situations. Social media lives in the eternal present.

Fourth, acknowledgment of uncertainty. You need to be comfortable with "we don't know yet" and "reasonable people disagree." Social media demands confidence and certainty.

Fifth, intellectual humility. You need to be willing to change your mind when presented with evidence. Social media is engineered to reinforce existing beliefs, not challenge them.

Sixth, shared reality. You need to agree on basic facts, even if you disagree on interpretation. Social media fractures reality into competing narratives.

None of this is what social media provides. All of it is what informed democratic discourse requires. You can see the problem immediately.

The Venezuela crisis was shaped by forces that operated against all six requirements. It was immediate, not thoughtful. It centered influencers, not experts. It was contextless. It demanded certainty. It reinforced existing beliefs. It fractured reality.

This is not sustainable for a functioning democracy. At some point, you can't make important national decisions when your population doesn't understand what's happening. You have strong opinions, but they're not informed. You're engaged, but you're confused. You're certain, but you're wrong.

This is the dangerous condition we're moving into.

The Long-Term Costs of Unverified Reality

Imagine a future where all major geopolitical events are experienced through social media distortion. You wake up, check Tik Tok, get a narrative about what happened internationally. You form an opinion based on that narrative. That opinion shapes your vote. That vote shapes policy. That policy shapes geopolitics. The distortion becomes reality.

This feedback loop is already operating. It will only accelerate.

The costs of this are enormous and often invisible. Better decisions are not made. Diplomatic opportunities are lost because the narrative doesn't allow them. Atrocities happen that could have been prevented because social media was focused on a different narrative. Opportunities for peace are missed because conflict narratives generate more engagement.

Military personnel have to operate in an environment where every decision is being evaluated through social media optics. Scientists have to communicate through Tik Tok if they want public support for research. Historians can't explain nuance because nuance doesn't go viral. Policymakers have to calculate political cost in terms of Twitter trending topics.

The system gets dumber. The decisions get worse. The discourse becomes increasingly incoherent.

And the scary part is that no one's doing this intentionally. No one woke up and said, "Let's make the world less informed about geopolitics." The system is just optimizing for engagement. The degradation is a side effect. But it's happening.

The Path Forward: What Would Actually Help

There's no easy solution. But there are principles that might help:

First, we need to be clear about what social media is: An entertainment medium, not an information medium. Treat it accordingly. Don't go to Tik Tok for geopolitical understanding. Go there for memes.

Second, we need to create real alternatives. Platforms or spaces or institutions where long-form analysis is rewarded. Where experts have more reach than influencers. Where engagement isn't the primary metric. This is hard. It requires investment. But it's necessary.

Third, we need intellectual humility. When you see someone confidently explaining something complicated in 60 seconds, that's a red flag. Actual expertise looks like nuance. Nuance looks like uncertainty. If an explanation is clean and clear, it's probably wrong.

Fourth, we need to slow down our reactions. When something huge happens internationally, the instinct is to form an opinion immediately. Resist that instinct. Wait for multiple sources. Wait for time to clarify what actually happened. Your initial reaction is not reliable.

Fifth, we need to defend journalism. Actual journalism, the kind that requires funding and time and expertise. It's under assault from platforms that don't pay for content but do show it. Supporting journalism is supporting informed democracy.

Sixth, we need to be very skeptical of narratives that are too clean. Reality is messy. If a geopolitical event is explained as purely good or purely bad, purely imperialist or purely humanitarian, that's a narrative, not an analysis. Real analysis lives in the complications.

Seventh, we need to remember that our initial emotional reaction is not information. It's just emotion. Information comes from investigation, from multiple sources, from time. The fact that something feels true doesn't make it true.

Last, we need to collectively decide that informed citizenship matters. It's easier to just react emotionally to social media narratives. It's harder to actually understand what's happening. But the difference between an informed citizenry and an uninformed one is eventually catastrophic.

Conclusion: The Cost of Narrative Reality

The Venezuela intervention was a real geopolitical event with real consequences. Real people died. Real institutions changed. Real power was exercised. But the way most people in most countries understand that event is through social media narratives that are mediated by algorithms designed to maximize engagement, not accuracy.

This is not sustainable. You can't make good decisions as a society if you don't understand what's happening. You can't have functioning democracy if public opinion is shaped by Tik Tok engagement metrics rather than facts. You can't have informed citizenship when the primary information source is engineered to reward emotional response over understanding.

The immediate future is clear: More geopolitical events will be filtered through social media. More narratives will compete for engagement. More people will form strong opinions based on incomplete information. More policy will be shaped by what's trending rather than what's true. The distortion will accelerate.

But the long-term future is uncertain. At some point, the gap between narrative and reality becomes too great to ignore. At some point, decisions made based on distorted information produce consequences so severe that people demand something better. Whether that pushes us toward better media, better literacy, better platforms, or something else entirely remains to be seen.

What's clear is that the current system is broken. Not because any individual is acting maliciously, but because the system itself is optimized for engagement over understanding, for narrative over fact, for speed over accuracy.

Until we rebuild the information ecosystem with different incentives, geopolitics will continue to be experienced as narrative rather than reality. And that's a threat to everything that depends on informed collective understanding.

FAQ

What is the impact of social media on geopolitical events?

Social media has fundamentally changed how geopolitical events are understood and communicated. Instead of information flowing through traditional journalists and experts, it now flows through algorithm-optimized content designed for engagement. This creates a systematic bias toward simplification, emotional resonance, and narrative clarity, regardless of accuracy. Major military interventions are now experienced by billions as 60-second videos rather than as complex international affairs requiring historical context and expert analysis.

How does the algorithm affect the spread of information about international conflicts?

Algorithms prioritize engagement above all else, which means emotionally charged content spreads faster than nuanced content. False claims that trigger anger or fear generate more engagement than accurate claims that require context to understand. A Tik Tok video confidently stating something false reaches millions before a fact-check documenting the inaccuracy can reach thousands. This creates a structural advantage for oversimplification and misinformation, not because platforms want this, but because engagement metrics reward it.

Why can't fact-checking effectively counter misinformation during major international events?

Fact-checking fails at scale for several reasons: false information spreads six times faster than corrections, fact-checks reach far fewer people than the original false claims, people who believe false claims are unlikely to read corrections, and corrections often don't change minds even when they reach people. During a crisis like the Venezuela intervention, fact-checkers work reactively, always chasing new false claims. By the time a fact-check is published, the false narrative has already reached millions and the algorithm has moved on to the next viral claim.

What role do influencers play in shaping understanding of geopolitical events?

Influencers have essentially replaced experts as credible sources of information on social media. Someone with millions of followers can confidently explain complex geopolitical situations, even without subject matter expertise, and reach far more people than an actual historian or international relations scholar. This creates a credibility inversion where reach determines authority rather than knowledge. An influencer's entertaining but inaccurate take on the Venezuela intervention reached more people than a geopoliticist's careful analysis of historical context and competing interests.

How do competing narratives affect democratic discourse about international intervention?

When geopolitical events reduce to competing social media narratives, citizens are forced to choose between camps rather than form informed, nuanced opinions. Someone might simultaneously believe that the US has a history of destabilizing Latin America AND that addressing Maduro's authoritarianism was justified. But social media forces these into opposing positions. This polarization isn't created by outside propaganda; it emerges from the medium's architecture, which rewards taking the clearest possible position rather than acknowledging complexity.

What structural changes would be needed to improve how social media covers geopolitical events?

Fundamental structural changes would be required: platforms would need to prioritize understanding over engagement, slow content delivery instead of accelerating it, amplify experts instead of influencers, include historical context automatically, reward nuance instead of certainty, and create shared reality instead of factional ones. Essentially, they would need to operate against their current business model. Because advertising revenue depends on engagement metrics, platforms have perverse incentives to maintain the current system even though it's catastrophic for informed discourse about geopolitics.

How can individuals make better judgments about international events covered on social media?

Treat social media as entertainment, not information. If something important is explained in under 60 seconds, assume it's wrong. Read long-form journalism from established news organizations before forming strong opinions. Develop intellectual humility—if an explanation is clean and clear, it's probably oversimplified. Wait to react; your initial emotional response isn't reliable information. Look for sources who acknowledge uncertainty and complexity rather than those who display absolute confidence. Remember that viral doesn't mean true.

Key Takeaways

- Social media algorithms collapse complex geopolitics into engagement-optimized narratives, creating a reality where false certainties spread faster than true uncertainties

- Fact-checking cannot overcome algorithmic amplification, which rewards speed and emotion over accuracy

- Influencers now determine credibility based on follower count rather than expertise, inverting the traditional hierarchy of knowledge

- Polarization emerges from the medium itself, forcing people into binary camps that prevent nuanced understanding

- Democratic discourse erodes when citizens form opinions about international affairs without access to facts, context, or time for reflection

- Governments now optimize for social media narratives alongside traditional geopolitical strategy, with engagement metrics influencing real policy decisions

- The structural problems cannot be solved with incremental fixes like better fact-checking or media literacy, because the underlying business model rewards misinformation

This article investigates how social media platforms have fundamentally altered the way geopolitical events are understood and communicated globally. Using the January 2026 US intervention in Venezuela as a case study, we examine the mechanisms through which narratives replace facts, algorithms determine credibility, and informed democratic discourse becomes impossible at scale.

Related Articles

- How Political Narratives Get Rewritten Online: The Disinformation Crisis [2025]

- How Disinformation Spreads on Social Media During Major Events [2025]

- Reality Still Matters: How Truth Survives Technology and Politics [2025]

- The Viral Food Delivery Reddit Scam: How AI Fooled Millions [2025]

- Political Language Is Dying: How America Lost Its Words [2025]

- Can a Social App Really Fix Social Media's 'Terrible Devastation'? [2025]

![How Social Media Distorts Geopolitics: The Venezuela Crisis Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-social-media-distorts-geopolitics-the-venezuela-crisis-r/image-1-1768127855069.jpg)