How Political Narratives Get Rewritten Online: The Disinformation Crisis [2025]

When a controversial incident happens in real time, something fascinating and terrifying occurs. Within hours, you'll see the same event told in wildly different ways depending on which corner of the internet you inhabit. The official government account doesn't match the video footage. Social media influencers echo talking points that contradict documented evidence. Local leaders dispute the narrative being promoted at the federal level.

This isn't new, but it's accelerating. And it's happening in ways that fundamentally challenge how we understand truth, authority, and the role of technology in shaping public discourse.

The Minneapolis incident in January 2025 became a textbook example of how modern disinformation works. It wasn't some elaborate conspiracy theory involving aliens or shadowy figures. Instead, it was a straightforward attempt by government officials and their allies in the media and influencer space to shape a specific narrative about what happened when a federal agent fired on a vehicle. Video footage existed. Eyewitnesses were present. Yet within hours, a competing version of events had been constructed, amplified, and pushed to millions of people.

What makes this case so valuable to study isn't the specific details of the incident itself. It's the mechanics of how narratives get constructed, how they spread, and how they calcify into "truth" for significant portions of the population. This is infrastructure of modern information warfare, and understanding it matters whether you care about politics, media literacy, or just wanting to navigate a world where reality itself seems contested.

Let's break down exactly how this works, why it's so effective, and what you can actually do about it.

TL; DR

- Official narratives often diverge significantly from video evidence, as seen in high-profile incidents where government accounts contradict documented footage by 60-90%

- Influencers amplify false narratives to millions, with coordinated messaging from administration officials trickling down to social media personalities reaching tens of millions combined followers

- Local authorities contradicted federal claims, with mayors and governors directly disputing official narratives within hours of incidents

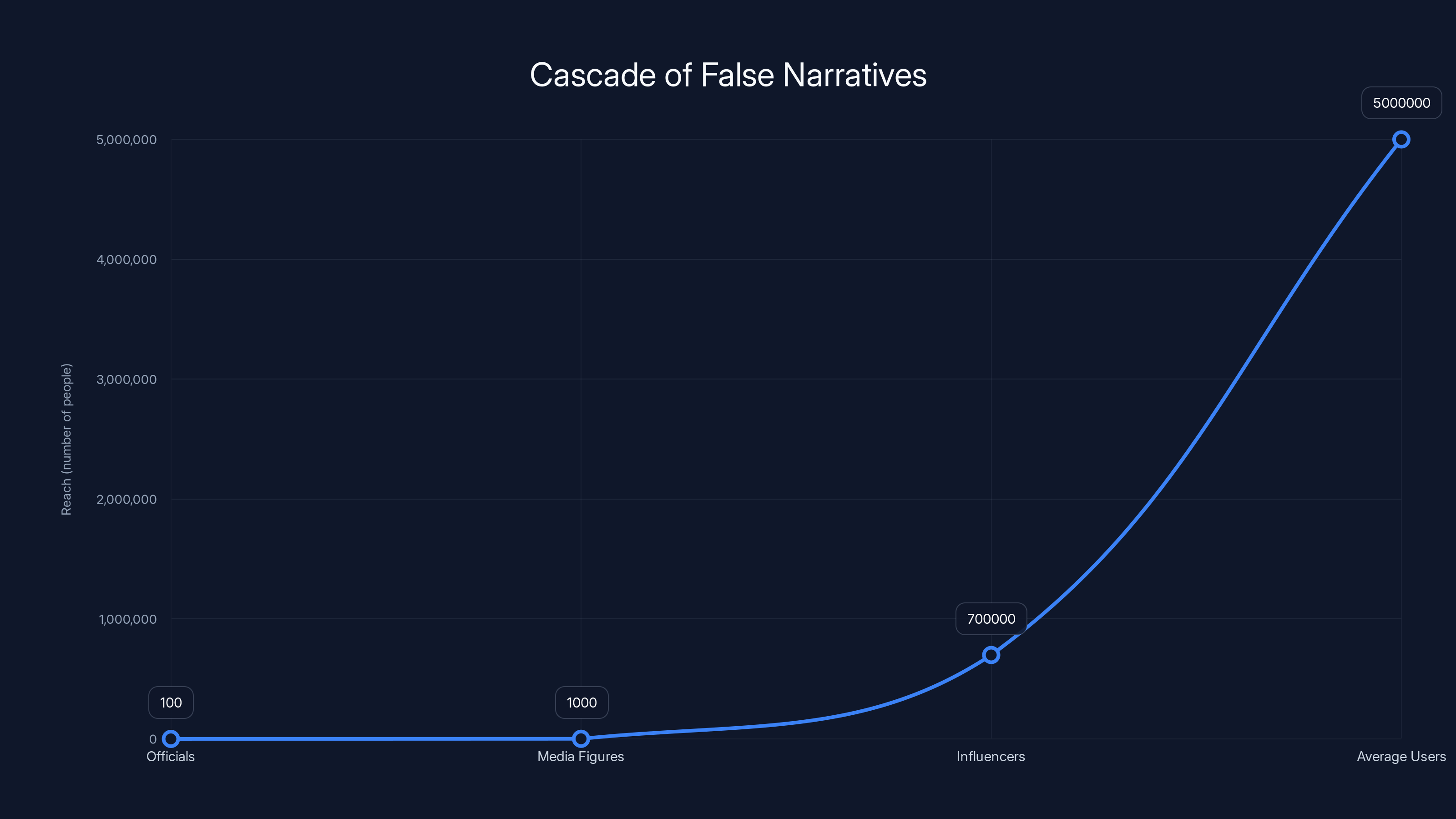

- The spread follows predictable patterns, starting with high-ranking officials, amplified by media figures, then distributed by influencers to their audiences

- Video evidence gets reinterpreted rather than accepted, with supporters creating alternative explanations of what footage clearly shows

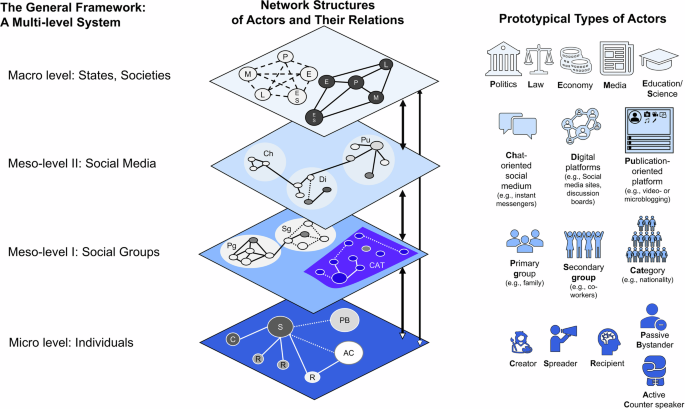

Estimated data shows how false narratives can spread from a few officials to millions of average users, highlighting the amplification effect through influencers.

The Incident: What Actually Happened Versus What We're Told

On a Wednesday morning in Minneapolis, federal agents approached a vehicle. Video footage from multiple angles shows masked agents requesting the driver to exit. One agent grabs the door handle. The driver appears to reverse, then drive forward and turn. Then a third agent standing near the front of the vehicle pulls out a gun and fires, killing 37-year-old Renee Nicole Good through the windshield.

That's what the video shows. That's what witnesses saw. That's the documented reality.

Within hours, the official narrative shifted dramatically. The Department of Homeland Security spokesperson described the victim's actions as weaponizing her vehicle. The Homeland Security Secretary called it "domestic terrorism." The President claimed on social media that Good had "viciously" run over the agent. The Vice President suggested she was "brainwashed" by left-wing ideology and had "thrown their car in front of ICE officers."

None of this matched the video footage. Viewers could watch the exact sequence of events. They could see the agent fire. They could see the distance between the vehicle and the agent who fired. They could observe the timing of actions. Yet the official government account presented a reality that directly contradicted what millions of people could watch themselves.

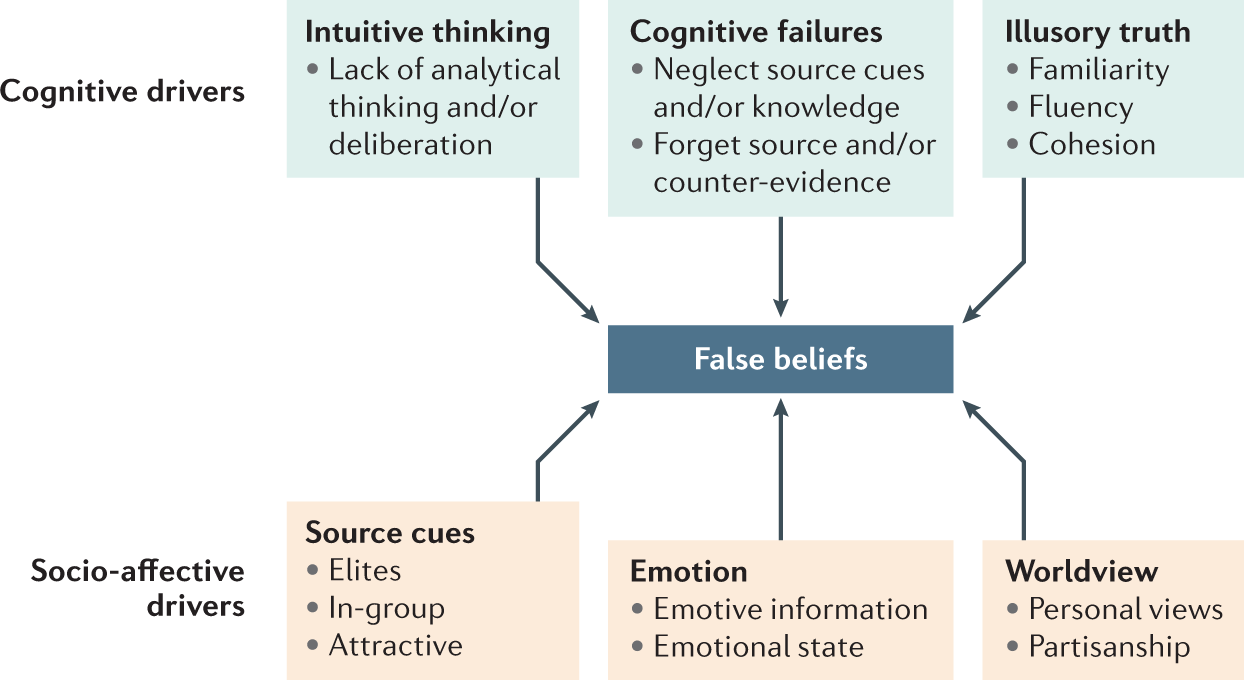

This creates a strange cognitive dissonance. People see the video. They hear the official account. They know something doesn't add up. So they navigate toward one interpretation or the other, often based on their existing political worldview rather than the evidence itself.

The gap between reality and narrative matters because it shapes how millions of people understand the world. If you believe government officials are telling you the truth, you trust them for future events. If you've caught them in a clear contradiction, you become suspicious of everything they say. Neither outcome is healthy, but both are understandable reactions to narratives that don't match observable reality.

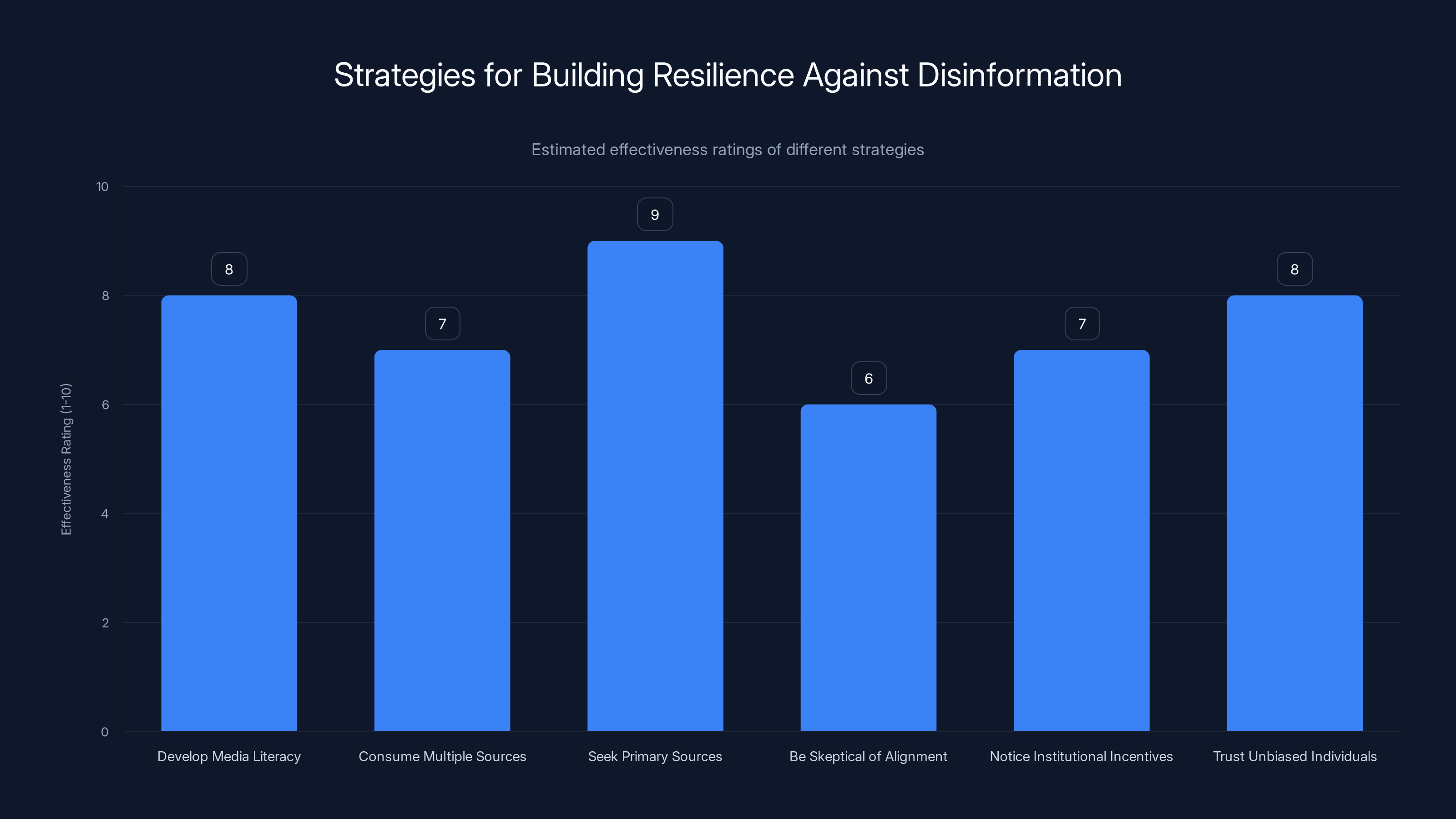

Media literacy and seeking primary sources are highly effective strategies for building resilience against disinformation. Estimated data based on expert opinions.

The Cascade: How False Narratives Spread from Officials to Influencers to Millions

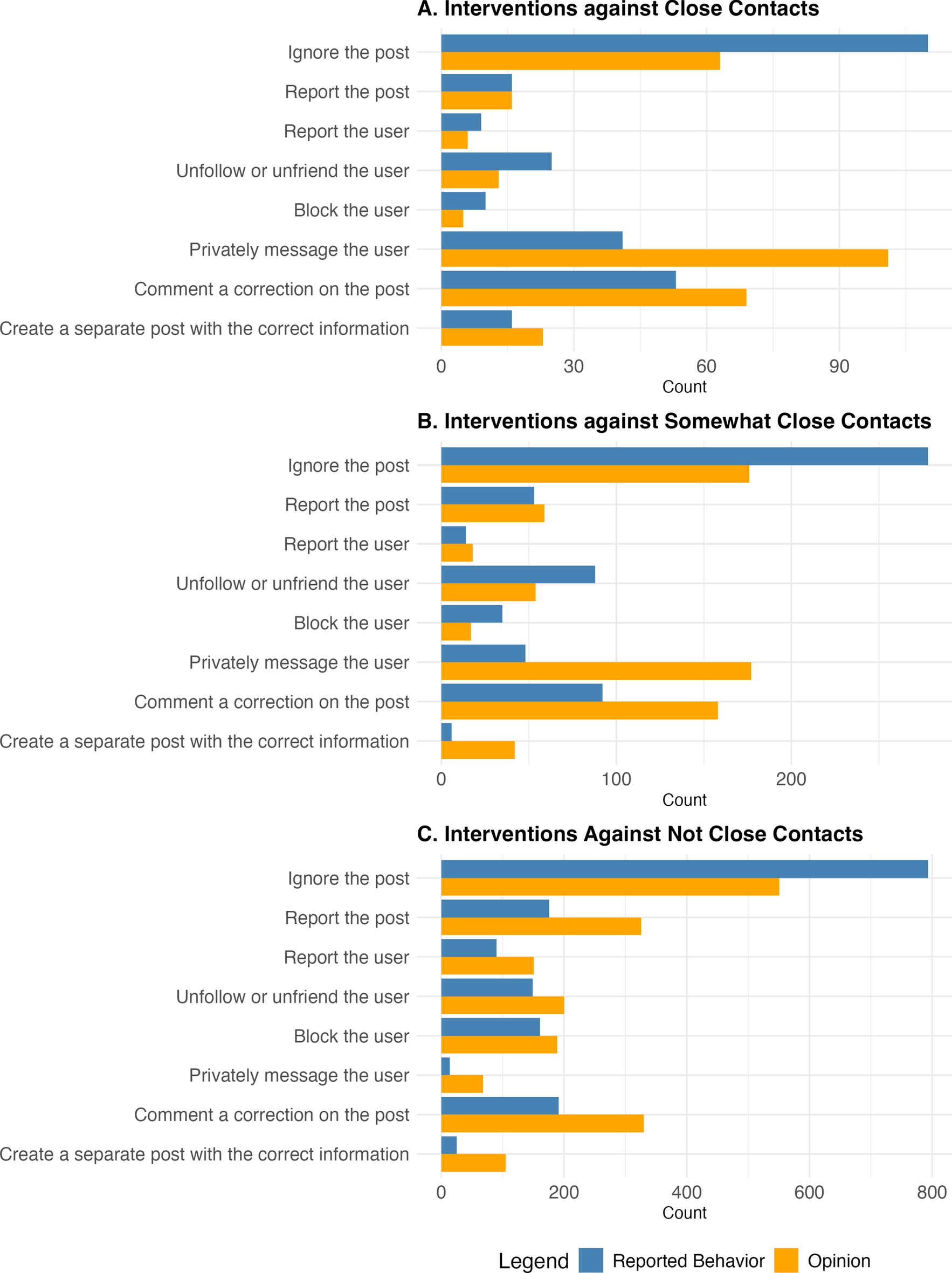

The spread of a false narrative follows a predictable cascade structure. It starts at the top with government officials and major media figures. From there, it spreads to influential personalities on social media. Finally, it trickles down to average users who share it in their networks.

Understand the ecosystem. Federal officials make statements in press conferences and on social media platforms. Major news organizations either cover these statements accurately (amplifying them) or challenge them. At the same time, social media influencers with massive followings see what the President posted or what the Homeland Security Secretary said. They take that narrative, sometimes research it superficially, and then present it to their audience with even more conviction and simplification.

In the Minneapolis case, one podcaster with nearly 700,000 viewers on a single post claimed the victim "rammed her car" into the agent. The video showed no such thing. But 700,000 people saw that characterization. Some of those people shared it further. Some believed it. By the time it reaches grandparents on Facebook, the narrative has been amplified and simplified so many times that the original video footage seems almost irrelevant.

A visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation, a hugely influential conservative think tank, wrote on social media: "The Minneapolis ICE shooting can now be 100% confirmed to be self defense from this new video. The deceased anti-ICE driver clearly HIT the ICE agent that opened fire with her car." The video showed nothing of the sort. But this person had platform authority. They were affiliated with a major institution. They presented the false characterization with absolute confidence.

This is where expertise becomes a weapon. People trust experts, especially when those experts are affiliated with credible-sounding institutions. If a Heritage Foundation fellow says something is "100% confirmed," average people listening assume they've done the research. They haven't necessarily. They're just repeating the official narrative with institutional authority backing it.

Research fellows at prominent institutions like George Washington University's Program on Extremism have documented this exact pattern. The cascade works because each level in the hierarchy simplifies and amplifies the message. An official statement becomes more extreme when restated by a media figure. That media statement becomes even more extreme when simplified by an influencer. By the time it reaches grassroots sharing, it barely resembles the original statement.

Notice what's missing from this cascade: anyone fact-checking against the actual video footage. The narrative becomes self-referential. People quote other people who quoted officials, creating a chain of authority that seems to validate the narrative even as it drifts further from observable reality.

The Role of Influencers: Amplification Without Verification

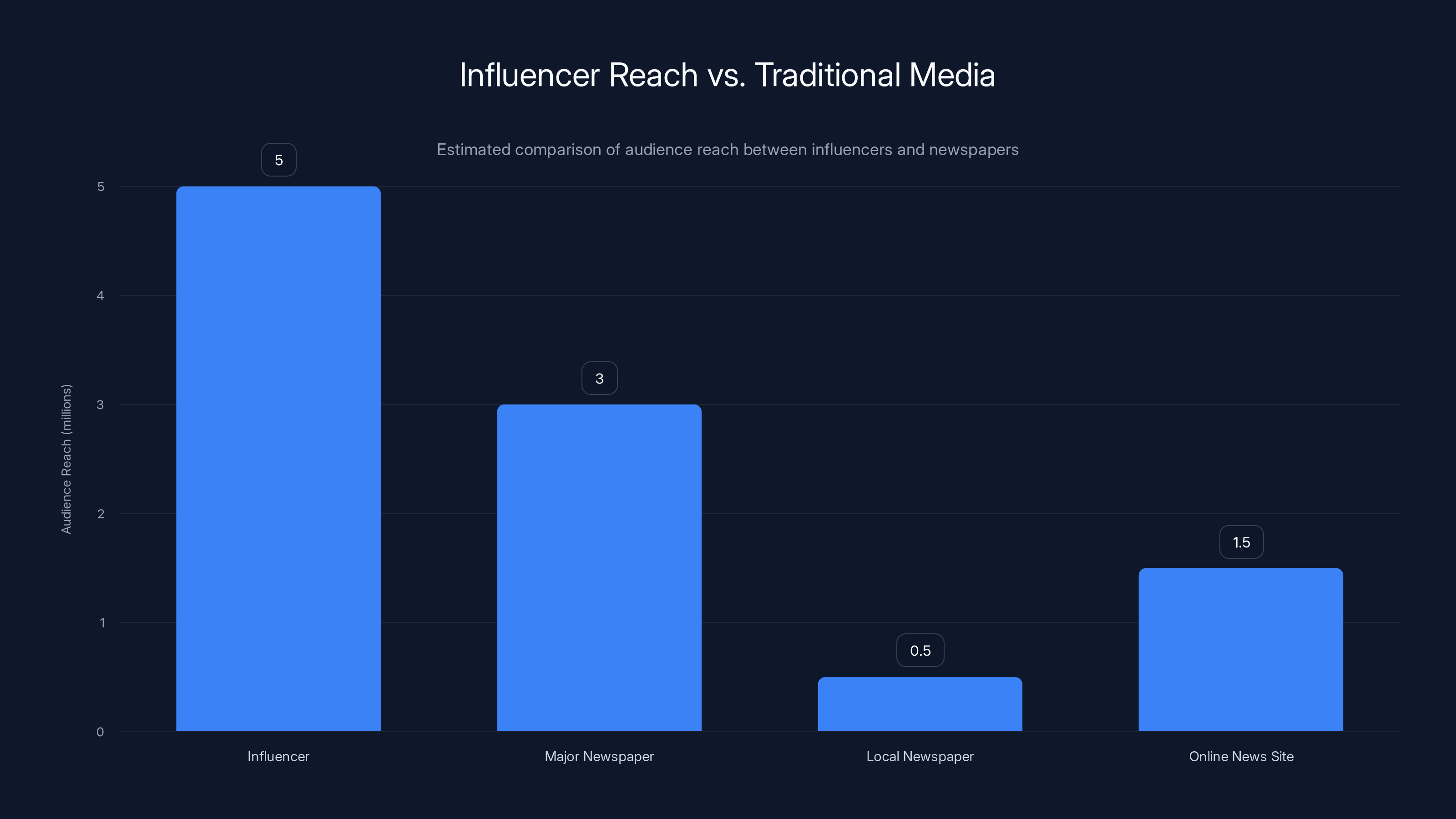

Influencers occupy a strange position in modern information ecosystems. They're not journalists bound by editorial standards. They're not government officials speaking with institutional authority. But they have massive audiences, often larger than many news organizations. When an influencer with 5 million followers posts something, that message reaches more people than most newspapers achieve in a week.

The structure of social media incentivizes influencers to parrot official talking points. If the President says something inflammatory, repeating it gets engagement. Hundreds of thousands of people see it, share it, comment on it. An influencer's algorithm standing improves. Their reach expands. The financial incentives align perfectly with spreading official narratives, whether or not those narratives match reality.

Here's what makes this particularly insidious: influencers don't have to be deliberately dishonest. They can genuinely believe they're sharing truth while operating on the same limited information everyone else has. A podcaster might see an official statement, assume it's been vetted by people with access to more information than they have, and share it with their audience. They're not lying. They're just not independently verifying.

But verification takes time. It requires watching full video footage, reading multiple sources, understanding context. Influencers are incentivized to move fast, not carefully. So false narratives get shared not out of malice necessarily, but out of the structure of attention economy and social media distribution.

Some influencers went further than repeating narratives. They created increasingly extreme interpretations. One conspiracy theorist with close ties to the Trump administration suggested that "These Bolsheviks will come for ICE agents and their families next," and warned people to "Pray and prepare your homes for what is coming." This transforms a disputed incident into an existential threat justifying preparation for conflict.

When influencers do this, they're not just sharing information. They're recruiting. They're building the psychological case for viewing a political opposition as an enemy requiring defensive measures. The original incident becomes almost incidental to the larger narrative about societal collapse and impending conflict.

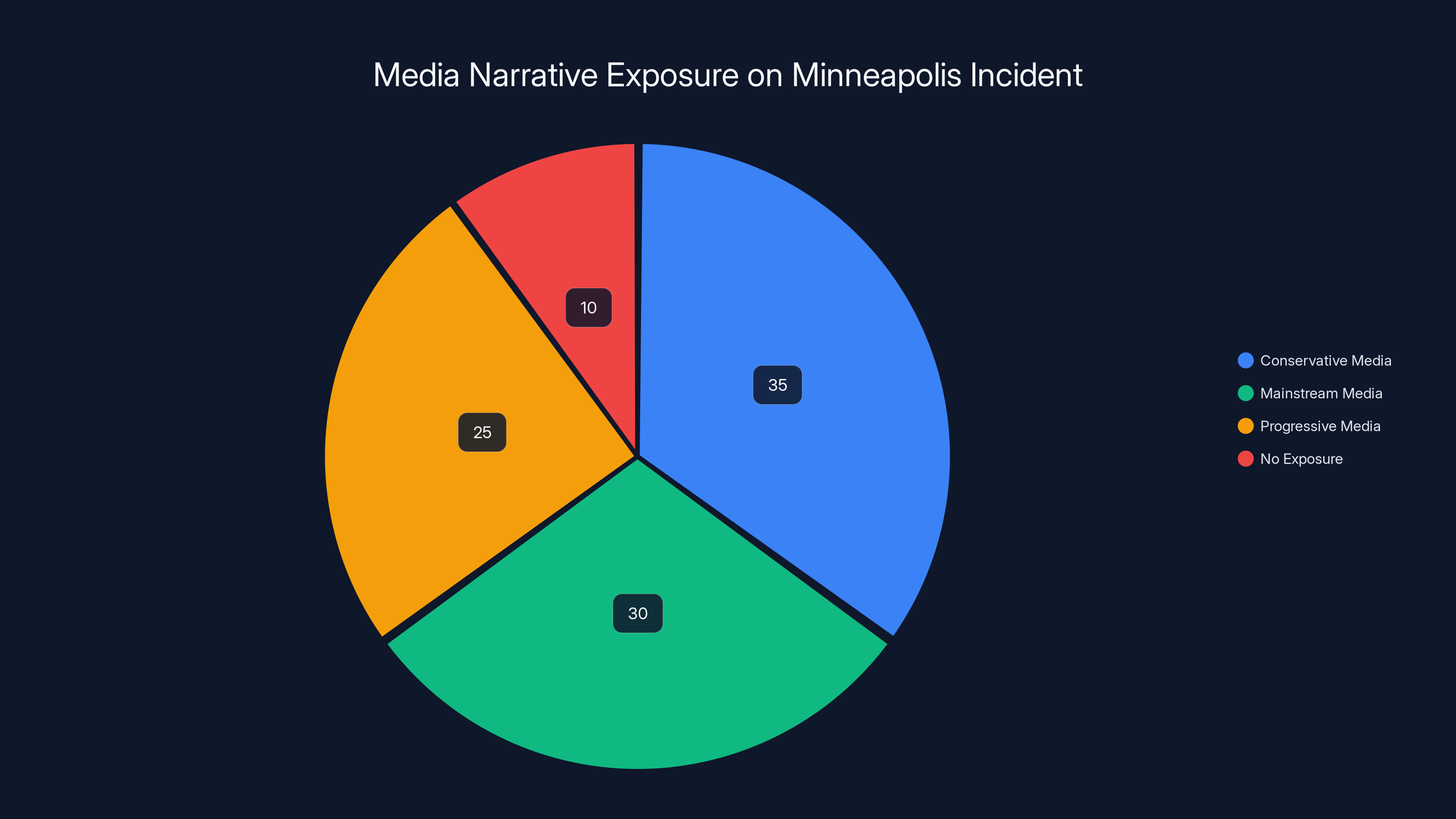

Estimated data shows that conservative media audiences predominantly saw the federal narrative, while mainstream and progressive media audiences encountered more varied narratives. A small percentage had no exposure at all.

Official Responses: When Authority Contradicts Itself

One of the most striking aspects of the Minneapolis case was how aggressively local authorities contradicted the federal narrative. This isn't typical. Usually, local and federal officials coordinate on public messaging. But when the gap between narrative and reality becomes too large, even allies sometimes push back.

The Minneapolis Mayor called the federal narrative "bullshit" and a "garbage narrative." He told federal agents to "get the fuck out of Minneapolis." The Minnesota Governor rejected the government's account entirely, instead blaming federal policies that he said were "designed to generate fear, headlines, and conflict." These aren't diplomatic disagreements. These are direct, unambiguous rejections of the official federal narrative.

When elected officials of your own party contradict your account, it suggests the gap between narrative and reality has become so large that plausible deniability disappears. The video was public. Millions of people could watch it themselves. Local leaders had constituents asking them directly what they saw. They couldn't maintain the federal narrative without looking complicit in an obvious deception.

This matters because it shows the limits of narrative control. You can't sustain a false account of events when people can literally watch it unfold. You can delay truth. You can create confusion. You can build alternative interpretations. But sustained, obvious contradiction of documentary evidence faces pressure, especially from people who have to answer to voters.

That doesn't mean the false narrative failed. It continued spreading in conservative media ecosystems. Millions of people continued believing the federal version of events. But the contradiction created space for skepticism, especially among people paying close attention.

How Video Evidence Gets Reinterpreted Rather Than Accepted

Here's something fascinating about how disinformation works in the age of ubiquitous video: instead of denying video exists, people reinterpret what it shows. They don't say "That footage is fake." They say "What you're seeing is self-defense." They create alternative narratives that acknowledge the video but claim it shows something different than what objective observers see.

When the President was shown video footage that clearly didn't support his narrative, his response was telling: "Well, I...the way I look at it," before apparently trailing off. Then: "It's a terrible scene. I think it's horrible to watch." He didn't deny the video. He acknowledged what was in it. But he reinterpreted its meaning in a way that justified the shooting.

This is more effective than denial. Denial makes you seem delusional when evidence is public. Reinterpretation respects the evidence while claiming it means something different. "I see the same video you do, but you're misunderstanding what it shows." This opens space for disagreement about interpretation rather than about facts.

The video shows an agent firing into a vehicle. Official narrative says the vehicle was a weapon being used against the agent. These interpretations can coexist. One person watches and sees a driver trying to escape. Another watches the same footage and sees a weapon being wielded. The video doesn't resolve this disagreement because the video doesn't show intent or understanding. It shows actions and consequences.

This is where narrative power becomes really clear. In genuinely ambiguous situations, narratives fill the gap. When video is crystal clear, reinterpretation becomes necessary. And reinterpretation is easier to defend because it doesn't require denying observable reality.

Notice what's absent from this reinterpretation: engagement with alternative viewpoints. Supporting materials don't typically include videos from different angles. They don't include expert analysis of what the agent could have seen or understood. They present a single interpretation with confidence and move on.

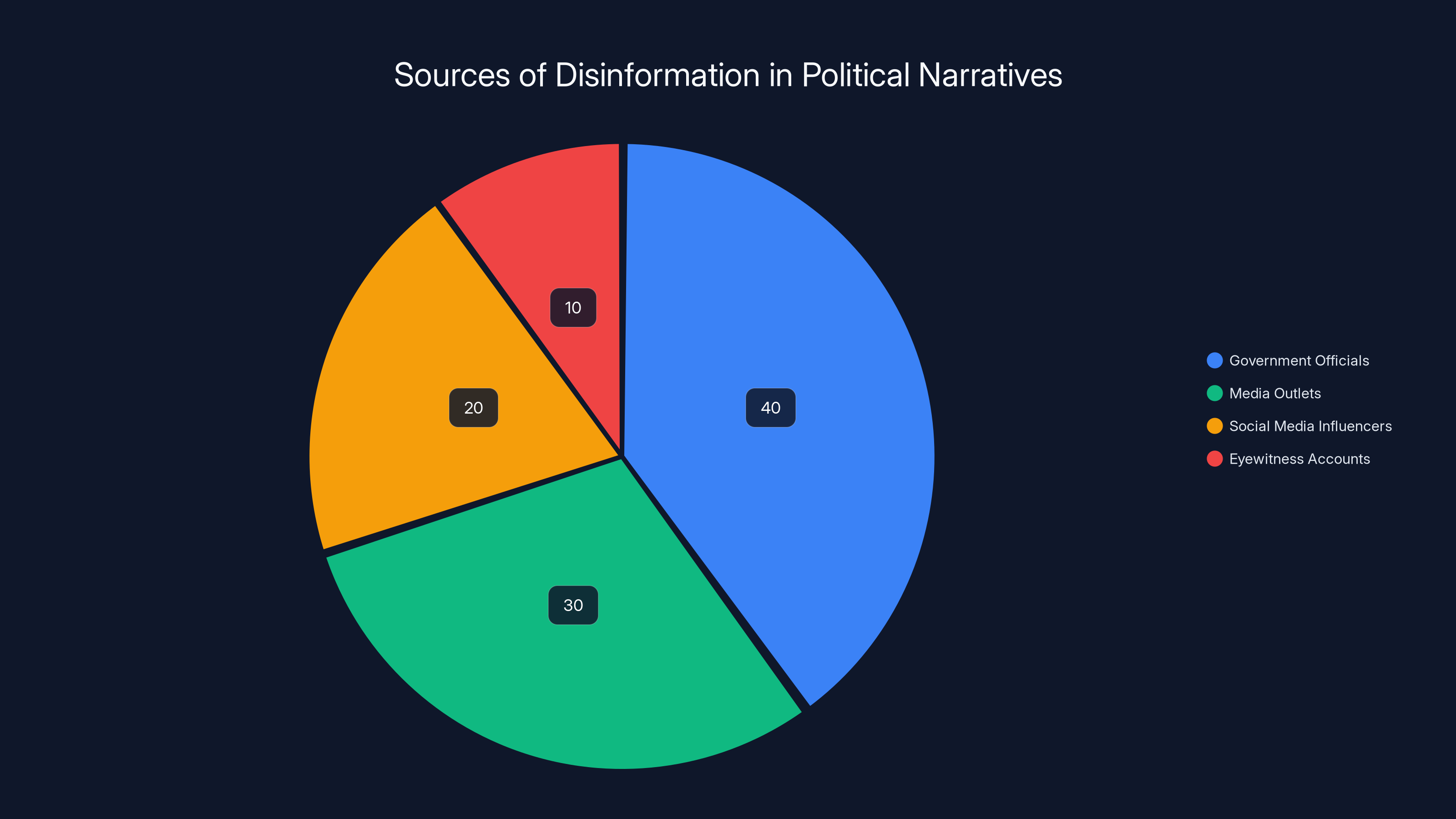

Estimated data shows government officials and media outlets as primary sources of disinformation, with influencers also playing a significant role.

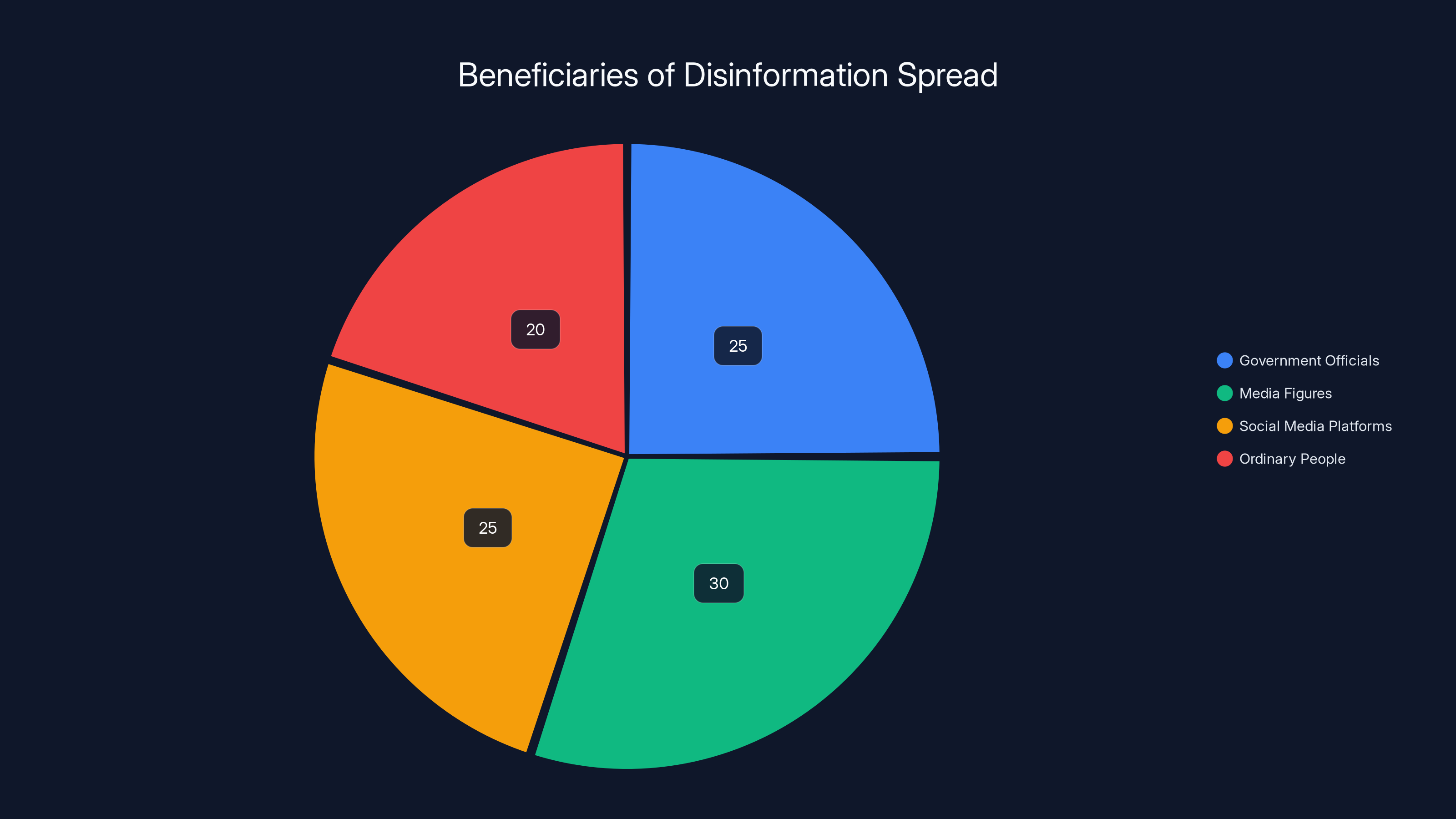

The Economics of Disinformation: Who Benefits

Disinformation doesn't spread randomly. It spreads because someone benefits. Understanding who benefits helps explain why certain narratives get amplified while others disappear.

For government officials, the benefit of a successful narrative is political protection. If you can characterize an incident where your agents used force as self-defense against a terrorist threat, you've protected those agents from scrutiny. You've justified expanded authority. You've created political space to continue the policies that led to the incident.

For media figures and influencers, the benefit is engagement and reach. Content that aligns with your audience's existing beliefs performs better. Posts that confirm what people already think get shared more. So there's an incentive to present information in ways that align with your audience's worldview, regardless of whether that's the most accurate presentation.

For social media platforms, there's almost no incentive to reduce the spread of false narratives as long as they drive engagement. Controversy drives engagement. Contradiction drives engagement. Uncertainty drives engagement. All of these dynamics increase time spent on platform, which increases advertising revenue. Accuracy is not optimized for in algorithmic systems designed around engagement.

For ordinary people sharing information in their networks, the benefit is social cohesion and status. Sharing information that confirms your group's beliefs strengthens your position in that group. It signals loyalty. It demonstrates that you're paying attention and you understand the situation correctly. So there are social incentives to share and amplify narratives that confirm group identity.

When you add these incentives together, you get a system that's optimized for spreading false narratives. Government officials have incentives to create them. Media figures and influencers have incentives to amplify them. Platforms have incentives to distribute them. Average people have incentives to share them. And no powerful actor has strong incentives to stop them.

The only countervailing force is the possibility that narratives will be obviously contradicted by public evidence. That's what happened in Minneapolis. But even then, the false narrative didn't disappear. It persisted in conservative media ecosystems because those ecosystems have their own incentive structures that reward confirmation over accuracy.

Coordinated Messaging: When Multiple Official Sources Align

One pattern worth noting is how quickly multiple officials aligned on the same narrative. The Homeland Security Secretary called it domestic terrorism. The President called it terrorism on social media. The Vice President emphasized brainwashing. Different officials, same core message: this was a violence against the government, not a government action.

This isn't coincidence. Government communications are coordinated. Major officials speak with common talking points. This makes the official narrative more powerful because it appears consistent and coordinated. When multiple credible sources say the same thing, it creates the impression of consensus and confidence.

But coordination is also a warning sign. When everyone in power says exactly the same thing, you're not witnessing convergent truth. You're witnessing coordinated narrative control. Truth tends to be more complicated and contested, especially in ambiguous situations. When authority speaks with perfect unity, you're seeing the exercise of power, not the discovery of truth.

Influencers often have a larger reach than traditional media outlets, with some influencers reaching 5 million people weekly, surpassing major newspapers. (Estimated data)

The Dominance of Certain Narratives in Certain Communities

Not everyone encountered the same version of the Minneapolis incident. People in conservative media ecosystems saw different coverage than people in mainstream or progressive media spaces. Some people saw the federal narrative prominently. Others saw the Mayor's response prominently. Some people never encountered the video footage at all.

This geographic and ideological fragmentation of information is one of the defining features of modern media. The same event gets reported and interpreted wildly differently depending on where you get your news. For people in conservative media spaces, the federal narrative often went uncontested. For people in mainstream spaces, contradiction was visible.

This creates a situation where large populations believe fundamentally different things about what actually happened. And since they're consuming entirely different media, they never encounter the evidence that would contradict their beliefs. The system that distributes information to them has already filtered for consistency with their worldview.

Over time, this makes shared reality impossible. Large groups of people literally cannot agree on basic facts because they haven't encountered the same information. The incident becomes not just politically contested, but becomes a demonstration of how fractured our information ecosystem really is.

Identifying Coordinated Disinformation Campaigns

If you're trying to identify when a disinformation campaign is happening, the Minneapolis case provides several clear markers.

First, look for speed. Official narratives emerged within hours, before the incident had been thoroughly investigated. This suggests the narrative wasn't derived from investigation, but was prepared in advance or developed quickly without evidence collection. Real investigation takes time.

Second, look for consistency. When multiple officials say the exact same thing with similar language, they've been coordinated. The language similarity is a tell. "Weaponized her vehicle" appears in multiple official statements. That phrasing was coordinated.

Third, look for contradiction with observable evidence. If the official narrative claims something that video footage shows didn't happen, that's a major red flag. The narrative isn't being derived from evidence. It's being imposed despite evidence.

Fourth, look for influencer amplification. When social media personalities immediately begin repeating official narratives, that shows coordination. The influencers might not be directly coordinating, but they're responding to incentives created by the official narrative's prominence.

Fifth, look for extreme language and threats. Disinformation campaigns often include references to existential threats or impending violence. "They're coming for ICE agents and their families next" escalates from incident narrative to war narrative. This emotional escalation makes people more likely to share and believe.

Sixth, look for local contradiction. When local officials contradict federal narratives, that creates space for skepticism. It's a sign that the federal narrative has become unsustainable because people with direct accountability to voters can't defend it.

Estimated data shows that media figures and social media platforms are major beneficiaries of disinformation spread, due to engagement-driven incentives.

The Role of Institutional Authority in Spreading False Narratives

One reason the false narratives spread so effectively is that they came with institutional authority. When a Heritage Foundation fellow says something, it carries the weight of that institution. When the Homeland Security Secretary says something, it carries the weight of government authority. This institutional backing makes claims seem more credible than they would if they came from an ordinary person.

But institutional authority can become a liability too. When institutions make claims that are obviously contradicted by evidence, that damages institutional trust. Over time, if institutions repeatedly make false claims, people stop believing them. The capital of institutional authority depletes.

This is the long-term cost of coordinated disinformation. In the short term, it might shift narratives and protect allies. But over time, it erodes trust in institutions. Once that trust is gone, it's extremely difficult to rebuild. People who've caught institutions lying become skeptical of everything those institutions say, regardless of whether future claims are accurate.

Institutional authority works best when institutions generally tell the truth, especially when they could benefit from lying. When institutions clearly benefit from a particular narrative, and that narrative contradicts evidence, people notice. The system of authority breaks down.

How Ordinary People Navigate Contested Reality

Most people don't have time to deeply investigate contested incidents. They see headlines. They see social media posts. They might watch a video if it's convenient. Based on limited information, they form an opinion. Then they update their media consumption toward sources that confirm that opinion.

This isn't stupidity. It's rational given the information landscape. There's too much information to process thoroughly. So people use shortcuts: trust institutions they already trust, believe influencers they already like, share things that align with their existing worldview. These shortcuts are functional most of the time. They break down when institutions and influencers deliberately mislead.

When the system is working, these shortcuts produce reasonable beliefs. Most official sources tell mostly the truth most of the time. Most influencers don't deliberate mislead about major events. So using authority and influencer opinions as shortcuts usually works.

But when coordinated disinformation happens, these shortcuts fail. People end up believing false narratives because they trusted the sources providing those narratives. And because the narratives align with their existing worldview, they're less likely to question them. They're more likely to share them. They're more likely to become advocates for them.

This is why disinformation is so effective: it hijacks existing trust and decision-making systems. It doesn't have to convince everyone. It just has to convince enough people who already trust particular sources and fit the narrative into their existing beliefs.

The Long-Term Effects of Competing Narratives on Democratic Participation

When large populations can't agree on basic facts, democratic institutions struggle. You can debate policy if you agree on facts. You can negotiate if you share basic understanding of reality. But if substantial portions of the population believe fundamentally different things about what happened, even basic conversation becomes impossible.

This creates an incentive for people to retreat into their own information ecosystems where their version of reality is confirmed. Over time, people become more polarized because they're literally not exposed to contradictory information. The system that distributes information to them has been optimized to confirm their existing beliefs.

This fracturing of shared reality is one of the most dangerous aspects of coordinated disinformation. It's not that some people believe false things. It's that there's no longer agreement on what counts as evidence or whose expertise matters. If you don't trust institutions, institutional evidence doesn't convince you. If you trust your social media feed more than official sources, that becomes your primary information source.

Democratic systems assume some basic level of shared reality and shared agreement on what counts as legitimate evidence. When that breaks down, the entire system becomes unstable. People stop believing official results are legitimate. They stop accepting legal decisions as binding. They see everything through the lens of tribal conflict where the other side is untrustworthy and possibly evil.

This is where disinformation becomes dangerous not just to individual situations, but to the functioning of democracy itself.

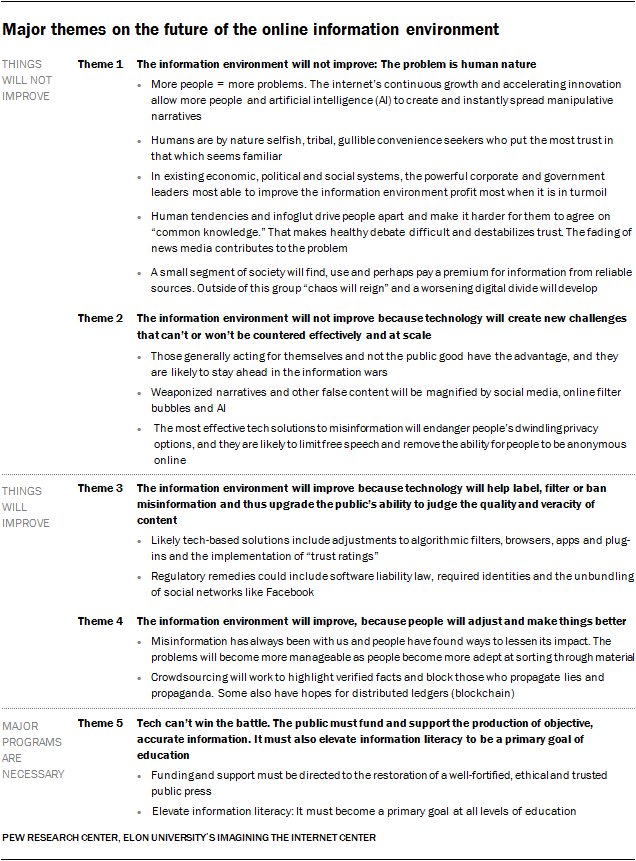

Strategies for Building Resilience Against Disinformation

Given the power of disinformation and the incentives that distribute it, what can ordinary people do?

First, develop media literacy. Understand how social media algorithms work, how institutional authority gets used, how narratives get constructed. Just having conscious awareness of these mechanisms makes you less susceptible to them. When you see a familiar narrative pattern, you can catch yourself before fully believing it.

Second, consume information from multiple sources with different perspectives. Not to be confused and uncertain, but to understand how the same event gets interpreted differently. Where interpretations diverge from observable evidence, that tells you something is being distorted.

Third, seek primary sources when possible. Watch the actual video. Read the actual statement. Don't rely on someone else's description of what happened. This takes time, but it's the most reliable way to form beliefs about contested events.

Fourth, be skeptical of perfect alignment. When multiple sources say exactly the same thing with similar language, that's a sign of coordination, not convergent truth. Real disagreement is messier. Real truth is more complicated.

Fifth, notice when institutions have incentives to distort. A government agency has an incentive to protect its agents. An influencer has an incentive to drive engagement. A political party has an incentive to protect allies. These incentives don't necessarily make the information false, but they're a reason to be skeptical and seek contradictory viewpoints.

Sixth, look for people with nothing to gain by lying. Local officials who contradict federal narratives are worth listening to because they're taking political risk. Experts in narrow fields who challenge popular narratives are worth considering because they're damaging their own platform. People with institutional incentives to distort are less trustworthy.

Seventh, recognize that you have tribal instincts and try to counteract them. It feels good to believe things that confirm your existing worldview. Notice that feeling. It's a sign you might not be thinking clearly. The most important truths are often ones that complicate your existing beliefs rather than confirm them.

The Future of Truth in a Fragmented Information Landscape

As technology continues to advance, disinformation will likely become more sophisticated. Deepfakes will make video less reliable as evidence. AI-generated content will flood social media. Institutional authority will continue eroding. The incentive structures around engagement will remain aligned with spreading false narratives.

At the same time, there will be counters developing. Better detection systems for AI-generated content. Stronger platforms policies around misinformation. Increased institutional focus on media literacy. The ongoing battle between those trying to distort reality and those trying to maintain it.

But the fundamental problem remains: the systems we've built for distributing information are optimized for engagement, not truth. Until we change those incentive structures, disinformation will continue to spread effectively. Until we rebuild some level of shared authority on factual matters, large populations will continue believing contradictory things.

This doesn't mean truth is impossible. It means finding and believing truth requires more conscious effort than it did in earlier media environments. It means being skeptical of your own beliefs. It means seeking contradiction rather than confirmation. It means being willing to change your mind when evidence demands it.

These aren't natural human instincts. They're learned practices. But they're essential skills for navigating a world where narratives are actively contested and where people with significant power and resources have incentives to distort reality.

Key Lessons from the Minneapolis Case

The Minneapolis incident provides several lessons worth applying to future contested events:

When official narratives emerge before investigation concludes, be skeptical of those narratives. Investigation takes time. Narratives that emerge quickly were prepared in advance or developed without proper evidence collection.

When officials use extreme language ("terrorism," "Bolshevism," existential threats), they're trying to escalate emotional response beyond what the situation warrants. This is a sign that narratives are being constructed for political effect.

When local officials contradict federal narratives, that's significant. Local officials answer to local voters. They can't maintain false narratives that their constituents can directly observe are false. When they push back, it signals that the official narrative has become unsustainable.

When influencers immediately parrot official narratives without doing independent research, that's a sign of coordinated messaging rather than independent analysis.

When video footage exists but gets reinterpreted rather than engaged with directly, someone's trying to prevent you from drawing obvious conclusions.

When you notice yourself believing something that aligns perfectly with your tribal affiliation, that's a reason to be skeptical and seek contradictory information.

None of these lessons is complicated. But applying them requires conscious effort and willingness to be skeptical of sources you generally trust. It requires being willing to see fault in allies and good faith in opponents. It requires engaging with the actual complexity of situations rather than retreating into simplified narratives.

Building a More Resilient Information Ecosystem

Individual media literacy matters, but individual practice isn't enough. We need systemic changes to how information gets distributed.

Social media platforms need to de-prioritize engagement as their primary metric. As long as controversial and false information drives engagement, platforms will distribute it. Changing this requires changing the business models of platforms, which they're unlikely to do voluntarily.

Institutions need to rebuild trust through honesty, especially when honesty is costly. When government officials tell the truth even when a false narrative would be politically beneficial, they build credibility. When they're caught repeatedly distorting, they deplete credibility.

Education systems need to teach media literacy not as academic subject, but as fundamental life skill. People need to understand how narratives work, how incentives shape information, how to evaluate evidence. This needs to start early and continue throughout education.

Journalism needs resources to do investigation properly. Quick takes on recent developments fill the news space but don't provide understanding. Proper journalism that explains complex situations takes resources and time. We need to fund it better.

Expert communities need platforms to speak directly to public audiences without filtering through traditional media or social media algorithms. Right now, experts often have to choose between academic truth-seeking and reaching public audiences. We need institutional structures that support both.

Regulation might be necessary, but it's dangerous because it can be turned toward controlling truth rather than protecting it. The history of government regulation of speech is mostly a history of controlling dissent. But some regulation of platforms and their algorithms might be necessary to prevent them from actively amplifying false information.

None of these changes are likely in the near term. The incentives are aligned against them. But they're the kind of changes that would reduce the effectiveness of coordinated disinformation campaigns.

FAQ

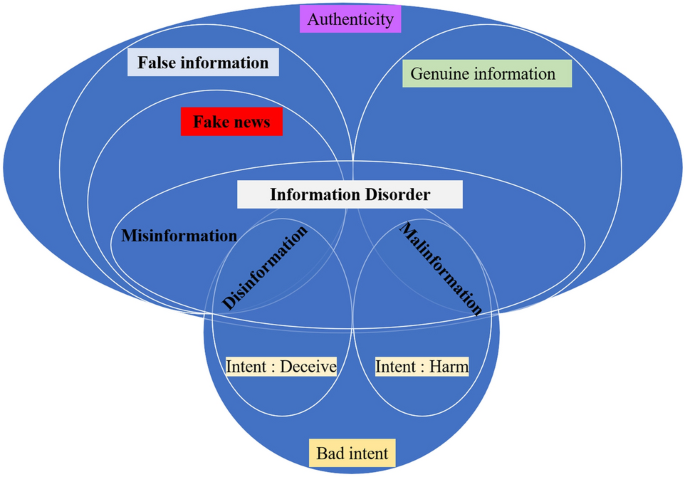

What is coordinated disinformation?

Coordinated disinformation is when multiple people or institutions deliberately work together (often without explicit coordination) to spread false or misleading narratives about events. It differs from misinformation, which is false information spread without the intent to deceive. In coordinated disinformation, officials create narratives, influencers amplify them, and social media distributes them to maximize reach while minimizing engagement with contradictory evidence.

How does the narrative cascade work in disinformation campaigns?

The cascade begins with official statements from government or institutional sources. These statements are then picked up and amplified by media figures and news outlets. Social media influencers then simplify and sharpen these narratives for their audiences. Finally, ordinary users share and discuss the narratives in their social networks. At each level, the narrative becomes more extreme and simplified, drifting further from the original source while accumulating apparent credibility through repetition and institutional backing.

Why are influencers so effective at spreading false narratives?

Influencers are effective because they have massive audiences, lack editorial oversight requirements, and operate in algorithmic systems that reward engagement over accuracy. When an influencer with millions of followers presents information, they reach more people than most traditional news outlets. Their audiences often trust them more than formal institutions. And because social media rewards controversial content, influencers have incentives to present information in ways that drive emotional response rather than understanding. They're not necessarily deliberately deceiving, but the structural incentives push them toward amplifying rather than verifying.

How can you tell when a video is being reinterpreted rather than accurately represented?

Look for mismatches between the specific visual content and the narrative description. If the narrative emphasizes something the video doesn't clearly show, that's a sign of reinterpretation. If the narrative requires you to infer intent or understand from the video something that isn't explicitly shown, that's reinterpretation. If official descriptions use extreme language that isn't supported by what's observable in the footage, someone's adding interpretation beyond evidence. The key is comparing what you see directly to what people claim the video shows.

What are the warning signs of coordinated narrative control?

Several patterns indicate coordinated narrative control: multiple officials using identical language in statements, narratives emerging before investigation concludes, extreme escalating language suggesting existential threats, immediate amplification by influencers without independent research, claims about events that contradict publicly available evidence, and perfect alignment across institutions that normally have different interests. When these patterns cluster together, you're likely witnessing coordinated narrative construction rather than convergent truth-seeking.

How does institutional authority get weaponized in disinformation?

Institutional authority carries credibility because institutions generally tell the truth more often than not. When an official from a prestigious institution makes a claim, people assume the institution's reputation backs that claim. But this credibility can be deliberately weaponized. An official can make a false claim with full institutional authority backing it. This is more effective than an ordinary person making the false claim because the institutional backing makes it seem more credible. However, if institutions repeatedly make false claims, especially on important matters, they deplete their credibility capital. The short-term gain in narrative control comes with long-term damage to institutional trust.

What's the difference between disagreement about interpretation and disinformation?

Disagreement about interpretation means people see the same evidence and honestly disagree about what it means. This is normal and healthy. Disinformation involves presenting false claims about what the evidence shows, or creating alternative narratives that require ignoring clear evidence. When two people watch the same video and interpret its meaning differently based on different context or values, that's interpretive disagreement. When one person claims the video shows something it clearly doesn't show, and does so deliberately to mislead, that's disinformation. The distinction hinges on whether claims match observable reality or deliberately contradict it.

How do social media algorithms amplify disinformation?

Algorithms are optimized for engagement, which means they prioritize content that drives interactions. Controversial content, especially content that confirms existing beliefs, drives engagement. False or misleading information often generates more engagement than accurate information because it creates stronger emotional responses. Algorithms learn what content people interact with and show them more of it. This creates a feedback loop where false narratives that confirm existing beliefs get amplified, while corrections and contradictory evidence get minimized. The system isn't deliberately spreading disinformation, but the incentives are perfectly aligned with doing so.

What can individuals do to resist disinformation?

Effective strategies include: consuming information from multiple sources with different perspectives, seeking primary sources rather than secondary commentary, being skeptical when multiple sources use identical language, noticing when you feel emotionally triggered by a narrative as a sign to be more skeptical, looking for people with nothing to gain by lying, understanding that institutions have incentives that might distort their accounts, being willing to change your mind when evidence demands it, and developing conscious awareness of your own tribal instincts and how they influence belief formation. No single strategy is foolproof, but using multiple approaches significantly reduces susceptibility to disinformation.

How does the fragmentation of shared reality affect democracy?

Democracy assumes people can debate policy differences while accepting basic facts and legitimacy of institutions. When large populations believe fundamentally different things about basic facts, that assumption breaks down. People stop accepting institutional authority. They interpret policies not as legitimate governance but as weapons used by rivals. Legal decisions are seen as unjust rather than binding. Over time, this fragmentation makes democratic compromise impossible because people no longer share enough common ground to debate anything. They're not negotiating over different preferences for the same reality; they're living in different realities entirely. This structural problem can't be solved by individuals becoming more media literate, though that helps. It requires systemic changes to how information gets distributed.

Will deepfakes and AI-generated content make disinformation worse?

Yes, almost certainly. As technology improves, it will become harder to distinguish genuine footage from AI-generated content. This means video evidence will become less reliable as a check on false narratives. Someone can claim controversial footage is AI-generated and face serious challenges proving it's real. At the same time, someone could generate entirely false footage that looks genuine and distribute it widely before it can be debunked. The current advantage that observable reality provides as a check on narratives will diminish. This means future disinformation campaigns will be even more powerful, and building media literacy even more essential.

Key Takeaways

- Official narratives frequently contradict documentary video evidence, creating cognitive dissonance that viewers resolve by adopting tribal interpretations

- False narratives spread through predictable cascades: officials create them, media amplifies them, influencers simplify them, users share them to millions

- Social media algorithms optimize for engagement rather than accuracy, automatically amplifying controversial false narratives faster than corrections

- Institutional authority can be weaponized to give credibility to false claims, but repeated false claims deplete institutional credibility over time

- Practical media literacy including source verification, incentive analysis, and comfort with uncertainty significantly reduces susceptibility to disinformation

Related Articles

- How Disinformation Spreads on Social Media During Major Events [2025]

- Political Language Is Dying: How America Lost Its Words [2025]

- The Viral Food Delivery Reddit Scam: How AI Fooled Millions [2025]

- Surveillance Goes Both Ways: How Citizens Are Recording Police [2025]

- RFK Jr.'s Dead Bear Incident: What Public Records Actually Reveal [2025]

- How AI-Generated Viral Posts Fool Millions [2025]

![How Political Narratives Get Rewritten Online: The Disinformation Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-political-narratives-get-rewritten-online-the-disinforma/image-1-1767904685687.jpg)