Introduction: When Witnessing Truth Becomes an Act of Courage

Something shifted in how we understand reality. Not gradually over years, but visibly, measurably, in real time. We watch the same events—a shooting, a protest, a policy announcement—and emerge convinced we witnessed different worlds. Technology promised to connect us. Instead, it fragmented our perception of what's actually happening.

Then came Minneapolis, January 2025. What started as another incident became a crystalline moment where the stakes of this fragmentation became impossible to ignore. A 37-year-old legal observer named Renee Nicole Good was killed by federal agents during an Immigration and Customs Enforcement raid. Within hours, the narrative fractured into incompatible versions. According to the Star Tribune, her mother described her as "an amazing human being."

One version existed in grainy 13-second clips, promoted across algorithmic feeds as the authoritative record. Another existed in the four-minute video captured by neighbors—multiple angles, multiple witnesses, context that changed everything. The first told you one story. The second told you another.

Here's what matters: ordinary people—neighbors in puffy coats and flannel shirts, walking their dogs on residential streets—refused to look away. They held their phones steady. They recorded. They bore witness. Not because they were activists or journalists or legal observers. They did it because they believed that shared reality was worth protecting.

This is the story of how misinformation, deepfakes, artificial intelligence, and political tribalism have eroded our collective ability to agree on basic facts. But more importantly, it's the story of why some people are still fighting to preserve the idea that truth matters at all.

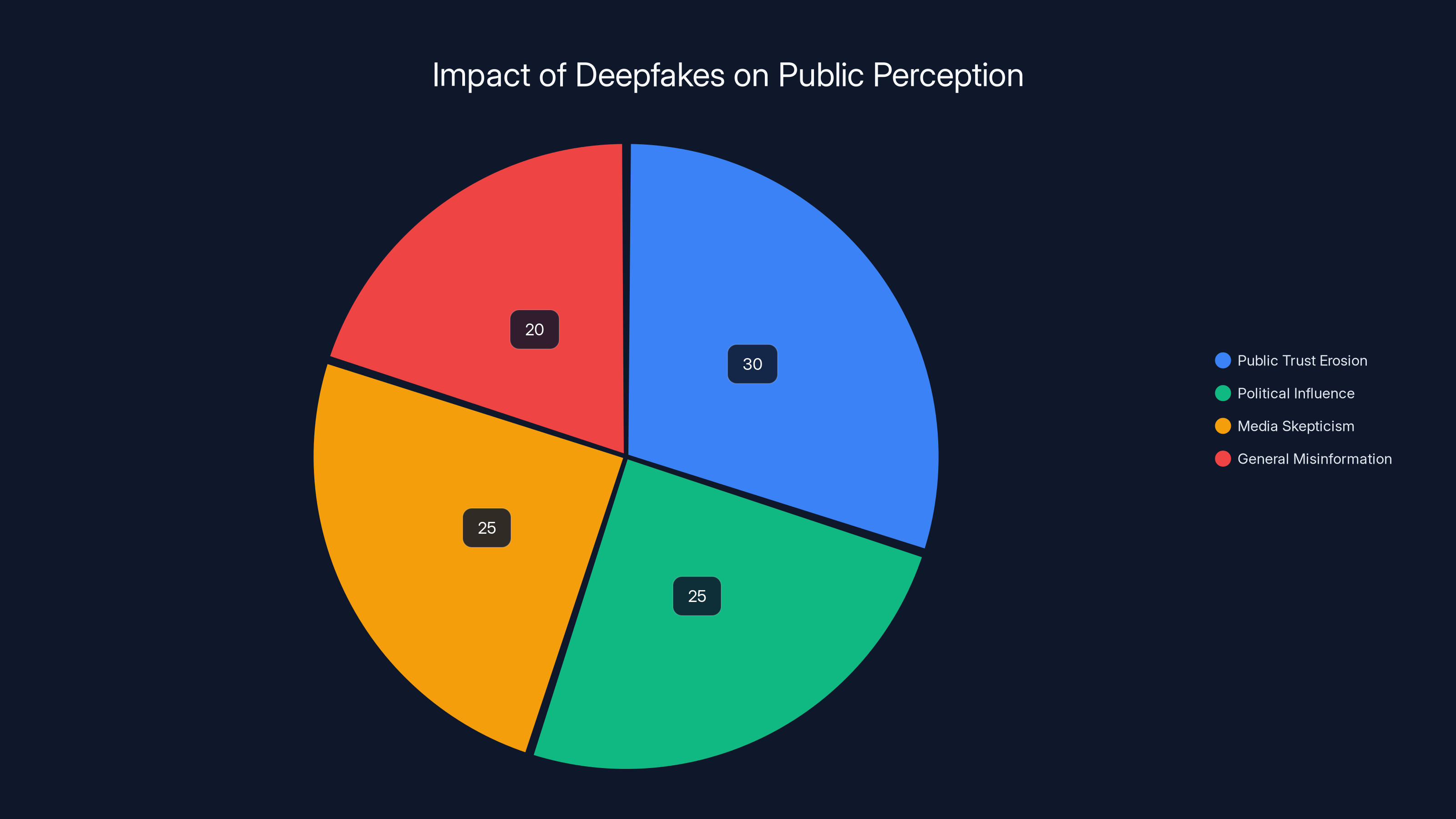

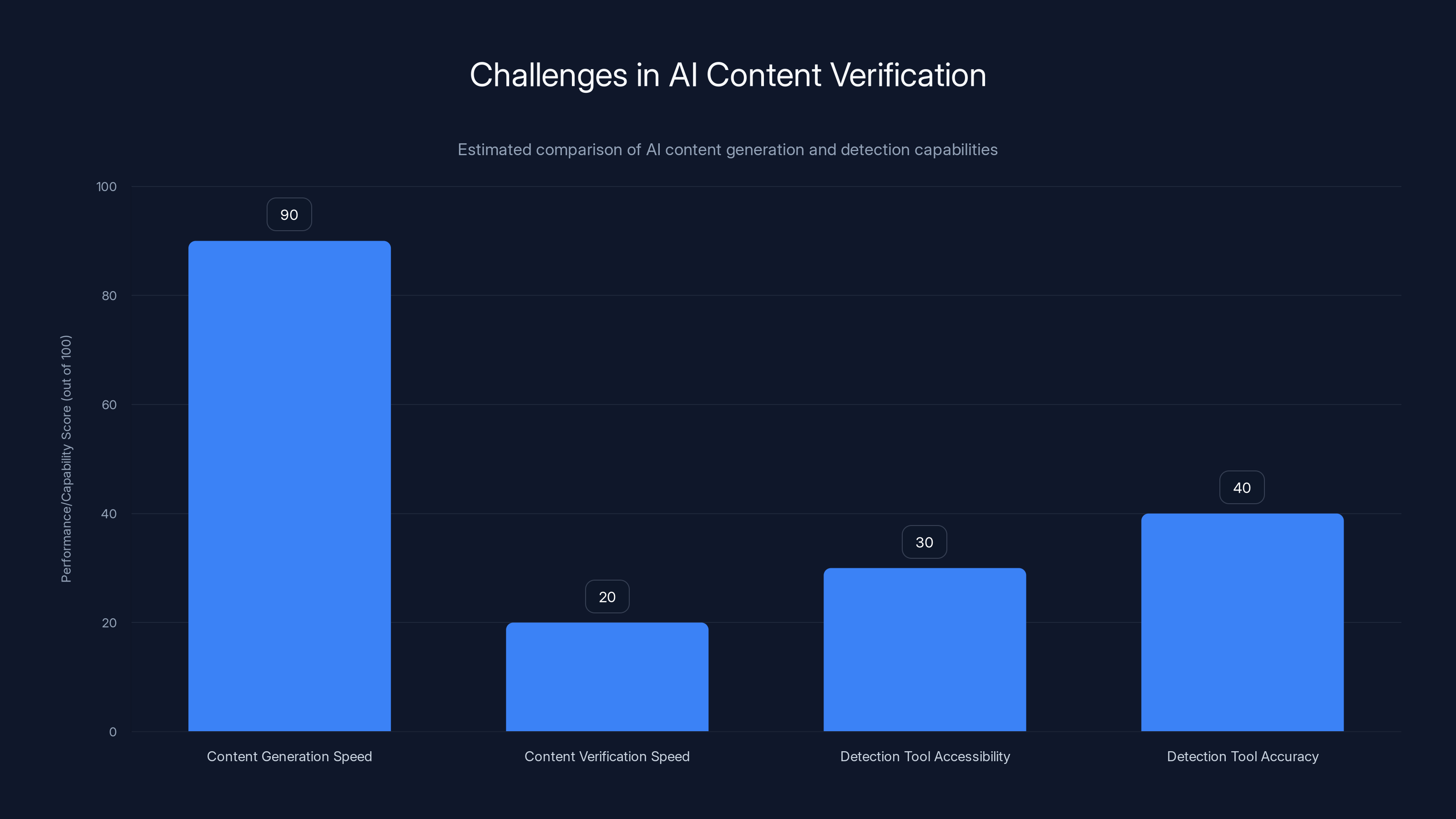

Estimated data shows that deepfakes significantly erode public trust (30%) and influence political decisions (25%), contributing to media skepticism and misinformation.

TL; DR

- Shared reality is collapsing: Political tribalism and algorithmic fragmentation mean Americans increasingly inhabit incompatible factual universes

- Technology accelerated the problem: AI-generated content, manipulated videos, and algorithmic amplification have made falsehoods easier to create and spread than truth

- Witnessing is becoming radical: Ordinary citizens recording events are now crucial counterweights to official narratives and institutional propaganda

- The Minneapolis shooting revealed the stakes: One grainy clip versus multiple videos, one narrative versus documented reality—the choice matters

- Truth still has defenders: Despite the odds, people continue to risk themselves to preserve verifiable facts and shared understanding

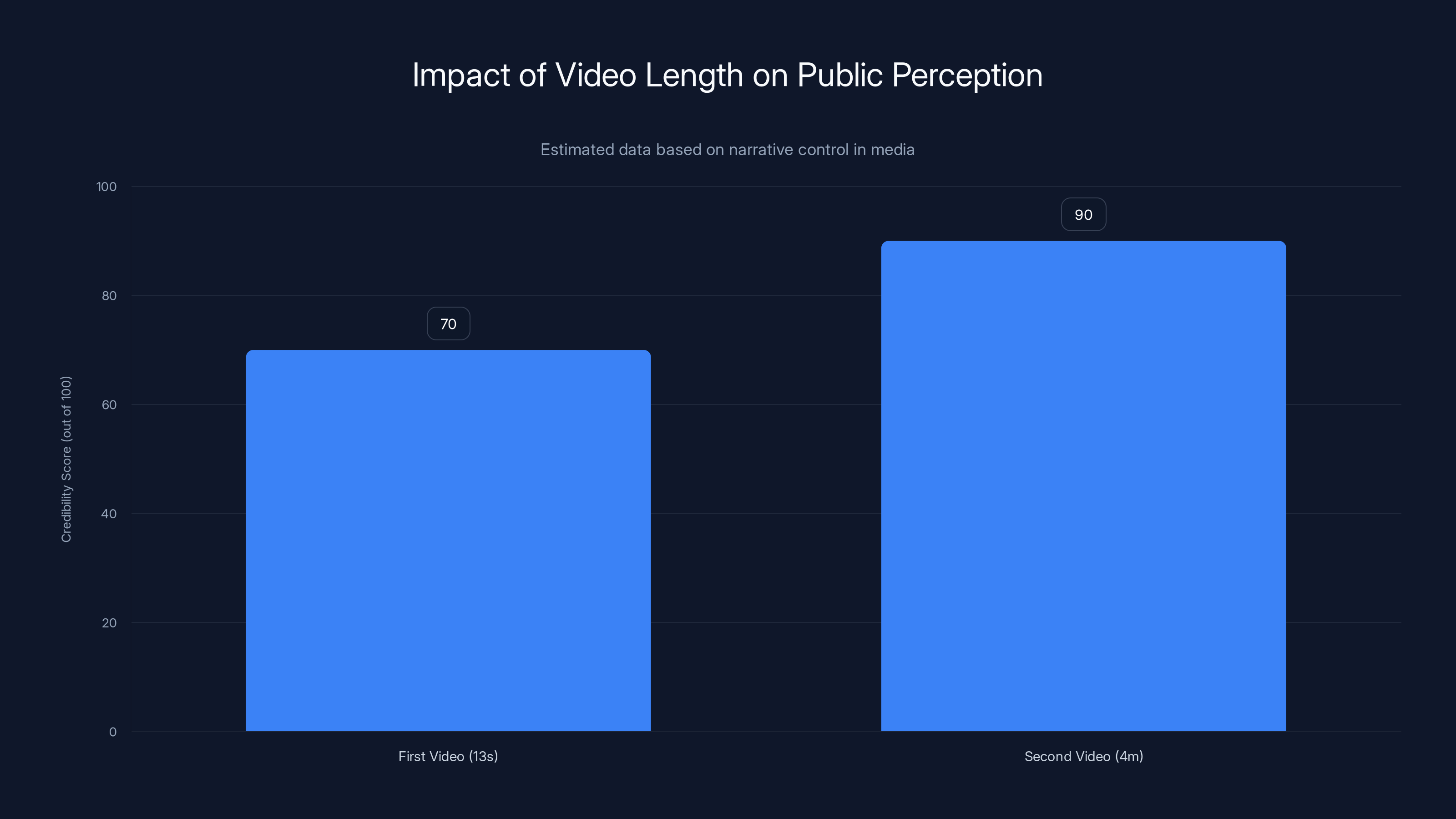

Estimated data suggests longer videos with more context tend to be perceived as more credible, highlighting the impact of narrative control through selective video promotion.

The Erosion of Shared Reality: How We Got Here

The Fragmentation Accelerated

We didn't wake up one morning unable to agree on whether the sky is blue. The fragmentation happened in layers, each one seeming small at the time.

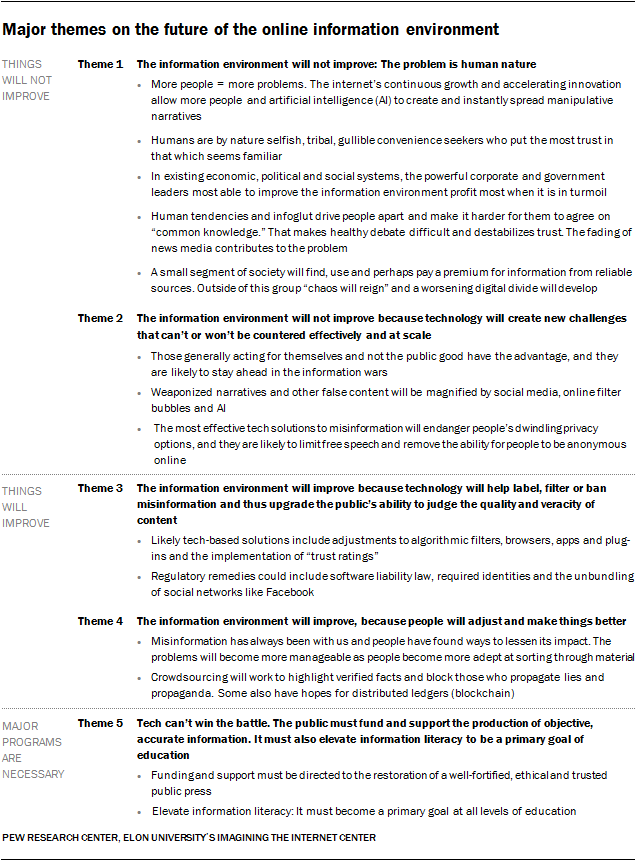

First came the algorithmic sorting. Social media platforms, optimizing for engagement, learned that confirmation feels good. Show people what they already believe, and they click more, share more, stay longer. The algorithm isn't neutral; it's a curator that actively pushes people toward their own versions of the truth. A person interested in immigration policy gets fed immigration stories that align with their existing views. A different person, interested in the same policy, gets a completely different set of stories.

Then came political tribalism—not new, but newly weaponized. When your side controls the narrative, the other side's evidence becomes automatically suspect. When truth gets tied to partisan identity, disagreeing about facts feels like a betrayal of your community. The incentive structure flips: admitting you were wrong means admitting your tribe was wrong. So people don't. They double down.

But the real transformation started with the internet's basic architecture. Before, truth had friction. If you wanted to spread a lie, you had to print it, distribute it, risk getting caught. Now, a lie can spread to a million people before the truth even finishes getting dressed. Every platform learned this the hard way.

Then came synthetic media. Deepfakes aren't sophisticated yet, but they don't need to be. All they need to do is introduce reasonable doubt. A video of a politician saying something inappropriate appears, it spreads for 24 hours, and even when it's debunked, 40% of people still believe it was real. The damage is done. The reputational cost is paid. Truth becomes optional.

The Role of Political Leadership in Weaponizing Doubt

When political leaders actively disregard reality, something breaks at the institutional level. It's not just that some people believe false things. It's that the most powerful people in the country are explicitly telling you not to trust what you see with your own eyes.

This isn't subtle messaging. This is explicit. When an administration calls someone a terrorist before her name is even known, before any investigation, based purely on her presence at a demonstration, it's not gathering information. It's manufacturing a narrative. When a single grainy clip is promoted as the authoritative record while multiple other videos are dismissed, it's not about finding truth. It's about controlling the story.

When leaders do this, they're not just lying. They're destroying the very concept that truth exists independently of power. They're saying: whatever serves my interests is real. Everything else is fake news. This is the ultimate corruption of language—not distorting reality to serve an agenda, but insisting reality doesn't exist at all except as whatever the powerful say it is.

The effect cascades. If the President says the footage contradicts what actually happened, and half the country follows him, what does truth even mean? If reality is just contested interpretation, then whoever has the biggest megaphone wins. The people with the most resources, the strongest algorithms, the most shameless willingness to lie—they control what's real.

Technology as an Accelerant

None of this is new in human politics. The difference is technological acceleration. Before the internet, spreading misinformation was hard. You needed presses, distribution networks, coordination. It cost money. It left traces. It could be countered.

Now a single person with a phone can reach millions of people. A bot farm can make a lie seem like widespread consensus. Artificial intelligence can generate convincing fake videos, fake audio, fake images. The cost of creating false evidence approaches zero. The cost of fact-checking approaches infinity.

Generative AI made this worse, not better. When anyone can feed a prompt and get back a plausible-sounding article, a convincing image, a video snippet, the epistemic ground shifts. You start to assume everything could be fake. You start to distrust even the things you saw yourself, because maybe you didn't understand what you were seeing.

And the platforms knew this was happening. They had teams studying misinformation, algorithmic amplification, the spread of falsehoods. They knew exactly what was going wrong. They also knew it was profitable. Engagement is higher when people are angry, when they're threatened, when they're certain the other side is lying. So even when platforms built protections against disinformation, they dismantled them when profitability required it.

The timeline here is deliberate, not accidental. Silicon Valley leaders lobbied against regulation. They removed fact-checking labels. They weakened content moderation. They optimized for engagement over truth. It wasn't that they didn't know. It was that they chose something else.

The Minneapolis Moment: When One Video Isn't Enough

The First Video, The Second Video, The Third

January 2025. An ICE raid. A residential neighborhood. A car accelerating. Three gunshots. The sound of impact.

The first video is 13 seconds long. It's grainy. It's the kind of video that, if you showed it to ten people, ten people might interpret it differently. Some would see a threat. Some would see a mistake. Some would see murder.

Within minutes, another video surfaced. This one shows more context. You see the armed agents before the shots. You see their positioning. You see what happens after the car accelerates. It's four minutes long, and it changes everything.

But the administration chose the first video. The 13-second clip. The one that's ambiguous. The one that doesn't show enough to make a judgment. They promoted that single angle as the truth, and they dismissed everything else as misinformation.

This is how narrative control works in the age of unlimited video. It's not that they prevented the other videos from existing. It's that they had a bigger megaphone. They could beam the preferred angle to more people, faster. The algorithm amplified their version. Their partisan media echoed it. By the time most people had access to the fuller video, many had already made up their minds.

The truly chilling part is how explicit it is. An administration willing to say, out loud, that your eyes are lying to you. That the video you're watching is fake, even though you're watching it. That the 13-second clip is real, and the four-minute clip is disinformation, even though both are real.

Renee Good and the Question of Witness

Renee Nicole Good was 37 years old. She was a legal observer, one of many people trained to document what happens when federal agents exercise power. Her job was to see and to record. To bear witness.

When the shooting happened, hundreds of people heard the shots. Dozens saw what happened. And what's extraordinary, what cuts against the entire narrative of apathy and alienation in modern America, is that they didn't leave. They didn't turn away. They didn't delete their videos.

They recorded. They watched. They put their phones up because they understood, maybe not consciously but in their bones, that someone with authority had just used lethal force, and whether it was justified depended entirely on what actually happened. And if the only record of what actually happened could be erased or rewritten, then no one was safe.

This is the moment where technology cuts in two directions. The same video platforms that amplify lies also allow evidence to persist. The same AI that can create deepfakes also helps analysts verify real footage. The same algorithms that create filter bubbles also occasionally break them when something becomes undeniable.

Renee Good's death forced a choice. You could either accept the official narrative—the 13-second clip, the explanation provided by authority—or you could look at the other evidence. You could be a passive consumer of whatever narrative was pushed to you, or you could actively seek additional information.

Most of the people in that Minneapolis neighborhood chose to seek additional information. They chose to record. To share. To bear witness. In 2025, this is a radical act.

The Ecosystem of Narrative Control

What's fascinating about the Minneapolis shooting is how quickly the ecosystem mobilized. Not just the administration, but the entire apparatus of institutional propaganda.

Official channels issued statements before any investigation. Media aligned with the administration ran the preferred interpretation. Online platforms amplified certain videos while de-prioritizing others. Algorithms served the 13-second clip to people and asked them to share their reactions, turning engagement into propaganda.

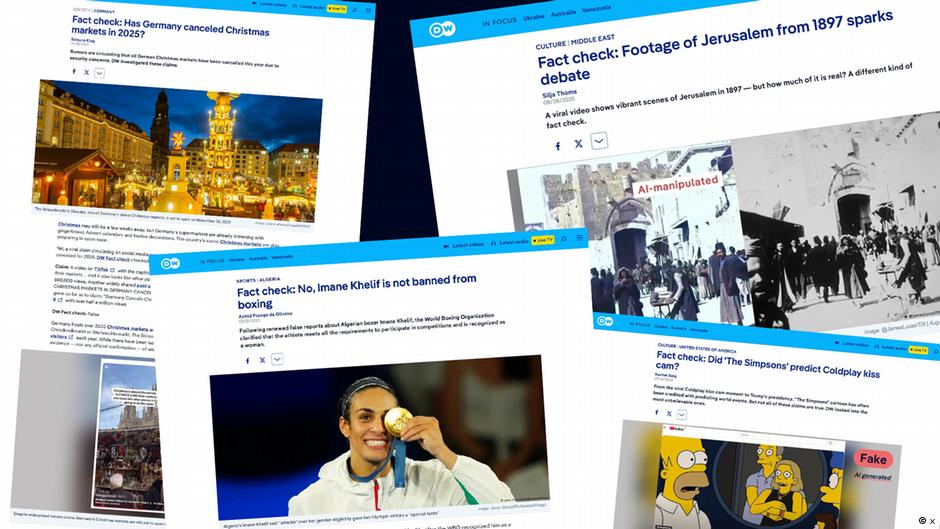

Meanwhile, fact-checkers faced visa denial. Journalists covering the story got harassed. Anyone presenting the fuller evidence got labeled as pushing a narrative. The irony is brutal: the accusation of bias was itself a propaganda technique, a way of saying, "You can't trust anyone who contradicts what we're telling you."

This is the new ecosystem. Not just one lie, but an interlocking system designed to prevent truth from gaining traction. Slow down the spread of inconvenient evidence. Speed up the spread of official narrative. Make people distrust experts. Make people afraid to publicly share what they believe. Create enough noise and ambiguity that nothing can be known for certain.

What stopped it, what forced a reckoning, was the stubbornness of ordinary people. The neighbors recording. The legal observers documenting. The family members screaming the truth into the cameras. The video evidence that couldn't be un-recorded or rewritten.

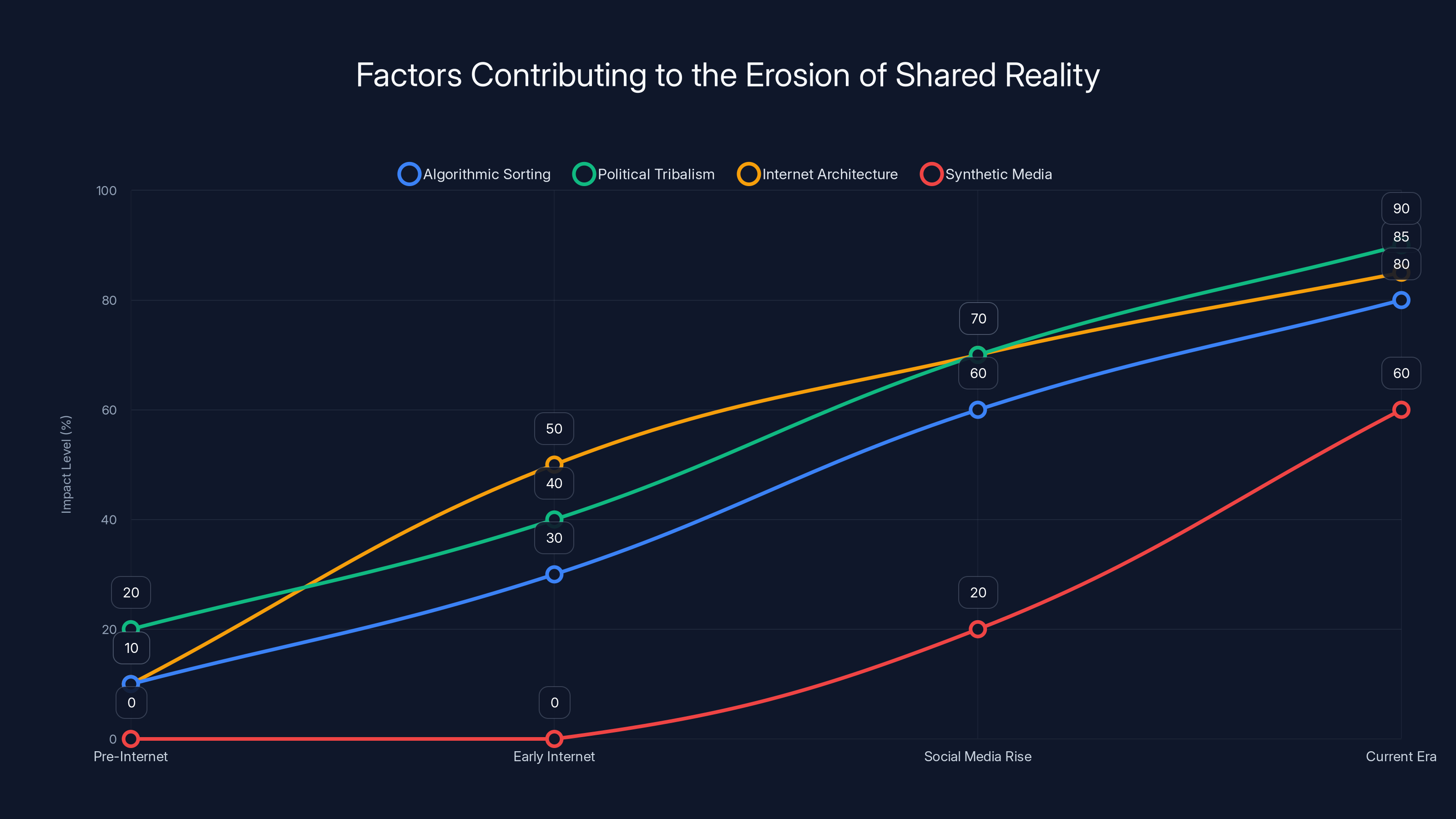

Estimated data shows how algorithmic sorting, political tribalism, internet architecture, and synthetic media have increasingly contributed to the erosion of shared reality over time.

The Deepfakes Are Coming: The Technology That Broke Trust

Why Deepfakes Destroy Verifiability

Deepfakes are scary not because they're good, but because they're good enough. A convincing fake video doesn't need to fool everyone. It needs to fool 30% of people for 72 hours. That's long enough for it to spread to millions. Long enough for it to shape political decisions. Long enough for it to cause real harm.

What makes deepfakes truly destructive is the epistemic problem they create. Before deepfakes, video evidence was basically reliable. You could argue about context, about framing, about interpretation. But if you saw it on video, it happened. The burden of proof was on the person claiming it was fake.

Deepfakes flipped that burden. Now, any video can be dismissed as potentially fake. You can't prove it's real anymore. The person making the claim has to prove the negative: "This isn't a deepfake." Good luck with that. There's no technical consensus on deepfake detection. The tools lag behind the generation tools.

So now we live in a world where the epistemic foundation is cracked. You watched something happen. You saw it with your own eyes. But maybe it was AI-generated? Maybe it was deepfaked? Maybe the angles were edited? Maybe it's out of context? Every claim can be doubted. Every piece of evidence is contingent.

This is what the administration understood when it promoted the ambiguous 13-second clip. It doesn't matter if it's real, as long as people doubt the alternatives. If people think the four-minute video might be doctored, might be edited, might be AI-generated, then the grainy clip becomes equally valid. Truth becomes a matter of preference.

The AI Acceleration Problem

Generative AI made deepfakes worse. Now you don't need expensive software and days of processing time. You feed a prompt to an AI, and it generates plausible fake content instantly. Text, images, audio, video. Each one is good enough to fool some people. Collectively, they create an environment where nothing is verifiable.

What's worse is that the same tools that create deepfakes also help detect them. An AI can spot when another AI generated something. But only if you're looking for it. Only if you're willing to do the work to verify. Most people aren't. Most people see something that confirms their priors and they share it.

The platforms knew this. They studied it. They watched the problem accelerate. And instead of implementing protections, they dismantled what few existed. Fact-checking labels were removed. Content moderation was scaled back. Verification tools were buried.

Not because the problem wasn't real. But because slowing down misinformation meant slowing down all engagement. And engagement is what drives growth. Engagement is what drives ad revenue. So the platforms chose profit.

The cost of this choice will be measured in eroded trust, in lost institutional legitimacy, in generations of people who don't believe anything they see. And by the time the damage becomes undeniable, the companies will have already made their money.

Building Resilience Against Synthetic Media

So what do you do when any video can be fake? When text can be AI-generated? When audio can be synthesized? How do you maintain epistemological standards?

First, you go back to basics. Multiple sources. Different angles. Corroborating evidence. The Minneapolis video was compelling not because of any single clip, but because dozens of people recorded it. Different phones, different positions, different lighting. The consistency across multiple recordings made it hard to dismiss.

Second, you value institutional expertise. Forensic analysts who can examine videos and assess whether they're doctored. Journalists with networks and resources and editorial standards. Researchers who study misinformation. Not because these people are infallible, but because they have methods. They have accountability. They have professional standards.

Third, you resist the assumption that all sources are equally valid. A video recorded by someone present at the scene has more credibility than a clip promoted by a politician who wasn't there. A scientific study in a peer-reviewed journal has more credibility than a blog post. An official body camera has more credibility than someone's claim.

This sounds obvious. But when the political culture has eroded trust in all institutions, when the dominant political movement explicitly tells people to doubt experts, it becomes radical. It means standing apart from your social group. It means admitting uncertainty. It means caring more about what actually happened than about what makes you feel right.

A few people in Minneapolis did that. They recorded the truth, even when the truth was inconvenient.

Tribalism, Algorithm, and the Dissolution of Shared Fact

The Filter Bubble Factory

Social media companies discovered something powerful: people are willing to spend hours on platforms that confirm what they already believe. If you believe X, show you more X. If you believe not-X, show them more not-X. Everyone stays engaged. Everyone feels validated. Everyone stays on the platform longer.

The business model requires fragmentation. Consensus is boring. Agreement is boring. Conflict is compelling. So the algorithm learned to personalize your truth. Your feed is built for you, and your friend's feed is built for them. You inhabit different information ecosystems even though you live in the same city.

Over time, this creates people who don't just disagree on policy. They disagree on basic facts. You've seen one set of evidence, they've seen another. You've read articles with certain sources, they've read articles with different sources. You've been surrounded by people who agree with you, they've been surrounded by people who agree with them.

This isn't accidental. This is the incentive structure of the platform. And it's incredibly effective at eroding the possibility of democratic deliberation, because deliberation requires that participants at least agree on what actually happened.

The Tribal Cost of Admitting You Were Wrong

Here's what social psychology tells us: once you've publicly taken a position, admitting you were wrong is harder than doubling down. Your identity is now tied to being right. Your friends' identities are tied to supporting you. To admit error is to let down your tribe.

This effect is amplified on social media, where everything is public and where your statements are algorithmically immortalized. You can't just change your mind quietly. You have to change your mind publicly, and accept the public consequence.

And the cost has been raised artificially. If your tribe has been told that the other side is evil, then admitting the other side was right on one issue feels like admitting they're right about everything. It feels like a betrayal.

So people don't. They find ways to reinterpret evidence. They claim the other video is fake, or out of context, or misleading. They trust sources that support their tribe, however unreliable. They dismiss sources that contradict their tribe, however credible.

This is why the Minneapolis shooting didn't immediately convince everyone. Half the country had already decided what the truth was based on tribal affiliation. The evidence had to be overwhelming, undeniable, multiple. And even then, some percentage of people rejected it, because accepting it meant accepting that they'd been wrong about their own government's actions.

The Generational Fracture

What's particularly corrosive is that different age cohorts have been trained in completely different epistemologies. Older generations learned to trust institutions: newspapers, government agencies, universities. Younger generations learned to distrust institutions and to create their own information ecosystems online.

Neither side is entirely right. Institutions can be captured and corrupted. But so can online communities. Neither source is pure truth. But when they completely diverge, when they're getting completely different information, shared democracy becomes impossible.

You can't have a functioning government if half the population doesn't believe what the other half believes actually happened. You can't have a functioning justice system. You can't have a functioning free press. You can't have anything because you don't even have baseline agreement on reality.

The Minneapolis shooting forced a moment of intersection. Because the evidence was so overwhelming, because there were so many videos, because the contradiction with the official narrative was so stark, it threatened the filter bubble. For a brief moment, people who had been in completely different information ecosystems had to confront the same facts.

Some people rejected the facts. Some people rejected the official narrative. And some people—the ones in the streets with their phones—did what citizens are supposed to do: they recorded the truth and made it impossible to ignore.

This chart highlights the stark difference in perceived inflation rates between two groups, illustrating the challenge in forming a consensus for policy-making. Estimated data.

When Witnessing Becomes Resistance

The Courage of the Ordinary

Let's be clear about what happened in Minneapolis. People heard gunshots. People saw federal agents. People understood that lethal force had been used. And instead of going inside, instead of protecting themselves, instead of assuming the official narrative would be accurate, they stayed. They recorded. They bore witness.

This isn't normal. This isn't what most people do. Most people keep their heads down. Most people assume that powerful institutions will handle things. Most people don't want to get involved. Most people don't want to risk themselves.

But the people in Minneapolis did. They risked themselves because they understood something true: that power corrupts the story it tells about itself. That the people with authority have incentives to present themselves as acting correctly, even when they're not. That without witnesses, without evidence, without a record made by ordinary people, the powerful can rewrite history.

This is what it looks like when democratic institutions have eroded so far that ordinary citizens have to perform the function of the free press. Have to perform the function of an independent judiciary. Have to perform the function of institutional accountability.

It's not sustainable. It's not ideal. It's what you're left with when every other system has failed.

The Role of Documentation

What's remarkable about the Minneapolis shooting is that it generated so much documentation. Not one video, but dozens. Not one perspective, but many. This redundancy is crucial. It makes the lie harder. It makes the official narrative harder to sustain.

But this redundancy doesn't happen by accident. It happens because enough people decided that documentation was important enough to risk themselves for. To pull out their phones while federal agents were nearby. To keep recording even when the situation was dangerous. To upload the footage even when they knew it would get them attention they didn't want.

They did it because they understood something about power and truth. That power wants narrative control. That truth is fragile. That the only thing more fragile is the will to tell it.

Every person with a phone became a witness. Every person who recorded became a documentarian. Every person who shared became a journalist. This is what accountability looks like when professional institutions have failed.

The Danger of Being a Witness

But let's not romanticize this. Being a witness is dangerous. Especially when the thing you're witnessing is the government exercising lethal force. Especially when the government has already decided you're an enemy.

The people in Minneapolis knew this. They knew that recording could get them harassed. Could get them targeted. Could get them in legal trouble. They did it anyway.

This is the cost of living in a culture of institutional distrust. It's not just that people don't believe the official narrative anymore. It's that they have to personally risk themselves to create alternative narratives. They have to become their own press. Their own accountability mechanism. Their own check on power.

It's exhausting. It's dangerous. And it's what happens when every other system has failed so comprehensively that ordinary people have to stand in the gap.

The Information Ecosystem's Failure

Professional Journalism's Slow Collapse

Once upon a time, this is what newspapers did. They sent reporters to the scene. They interviewed witnesses. They gathered documents. They fact-checked official statements. They published stories that held power accountable. This was their function.

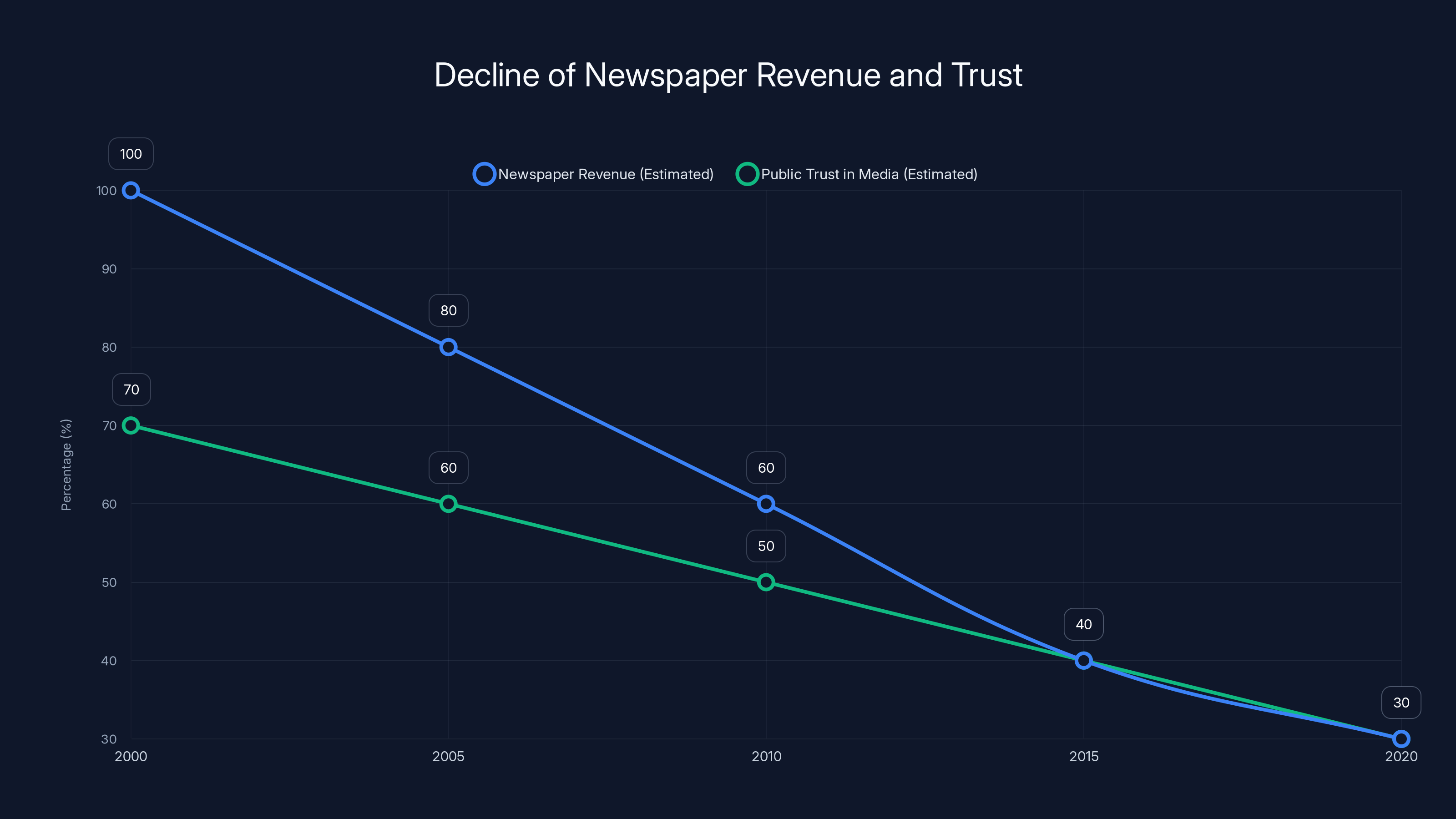

But the business model collapsed. When the internet made information free, the revenue that supported news organizations evaporated. As revenue declined, staff was cut. As staff was cut, quality declined. As quality declined, trust declined. As trust declined, revenue declined further.

Now most newspapers are shadows of what they were. The ones that survived did so by finding new revenue streams: paywalls, partnerships, political alignment. The last one is the most dangerous, because it means the newspapers become organs of particular political movements rather than sources of neutral fact.

What you're left with is a press that's fragmented, financially unstable, and increasingly tribal. The idea that there's a shared set of facts that newspapers report is gone. Instead, there are competing narratives, each with their own news outlets, their own preferred interpretations.

So when something like the Minneapolis shooting happens, there's no unified journalistic response. There's no Walter Cronkite moment where everyone agrees on what happened. Instead, there are competing versions, each amplified by different outlets, each reaching different audiences.

The citizens with phones became the journalists because professional journalism failed to be what democracy required.

The Fact-Checking Facade

For a while, there was hope that fact-checking could solve the misinformation problem. Outlets dedicated to verifying claims, flagging false statements, providing corrections. This seemed reasonable. If you could just show people what was true, they'd believe it.

But that's not how psychology works. Fact-checks often backfire, reinforcing false beliefs in people who already hold them. People interpret fact-checks through their tribal lens. If a fact-checker contradicts their preferred narrative, they assume the fact-checker is biased.

And the political response to fact-checking has been to destroy its credibility. Fact-checkers are dismissed as biased. Their credentials are questioned. Their neutrality is attacked. And because they're operating in an environment where everyone's credibility is equally suspect, they can't win.

Now, being a fact-checker can get you denied a US visa. It can get you harassed. It can get you fired. This is the world we've created: where the people trying to establish what's actually true are treated as enemies of the state.

The Platform Abdication

Social media platforms are the infrastructure of modern communication. They decide what billions of people see. They decided, at various points, to include fact-checking labels. To include context on political claims. To slow the spread of misinformation.

Then they decided not to. Or more accurately, they decided that the political cost of doing so exceeded the benefit. That supporting fact-checking meant facing accusations of bias. That moderation meant facing accusations of censorship. That it was easier to just let the chaos continue and let the algorithms run.

The platforms could have maintained their standards. They had the resources. They had the expertise. They chose not to, because it was more profitable not to.

So the infrastructure of truth-telling got worse, not better. The tools for spreading falsehoods got more sophisticated. The tools for verifying truth got weaker. The platforms optimized for engagement over accuracy, which means they optimized for divisiveness, for outrage, for lies.

Everyone knows this. Everyone sees it happening. And still it continues, because the incentive structures are so misaligned that no individual platform has reason to change. If one platform started moderating heavily, users would just migrate to a less-moderated platform. So there's a race to the bottom, toward less moderation, less fact-checking, more algorithmic amplification.

The citizens with phones were the last defense against this completely corrupted information ecosystem.

Estimated data shows a parallel decline in newspaper revenue and public trust from 2000 to 2020, highlighting the challenges faced by traditional media in the digital age.

Institutional Capture and the Legitimacy Crisis

When Power Redefines Reality

There's a particular moment where institutional legitimacy breaks. It's not when institutions make mistakes. It's when they deny making mistakes, when they redefine reality to claim they didn't do what they obviously did.

When an administration calls someone a terrorist before any investigation, before knowing anything about them, it's not about facts. It's about power. It's saying: reality is whatever I say it is. What you see with your own eyes doesn't matter. What documents show doesn't matter. What experts conclude doesn't matter. What matters is my interpretation.

This is authoritarian rhetoric. This is what happens when power stops trying to convince people that it's right and instead tries to convince them that they can't trust their own perception of reality.

Once a government does this, trust is gone. Not just trust in that particular claim, but trust in the institution itself. Because if you can't trust the government to tell you basic facts about what it's doing, you can't trust the government at all. You can't live in a society where power gets to redefine reality, because that means nothing is stable, nothing is knowable, nothing can be planned around.

This is why the Minneapolis moment mattered so much. It was a visible moment where ordinary people explicitly rejected an official reality. They said: we know what we saw. We have evidence. We're not accepting your redefinition of events.

The Erosion of Democratic Norms

Democracy doesn't require that everyone agrees. It requires that everyone agrees on how disagreement works. It requires shared procedures, shared institutions, shared acceptance that some neutral arbiter can resolve disputes.

But when the government itself becomes a party to the dispute, when the government is making claims about its own actions, that system breaks down. Who's the neutral arbiter? The court system, which is part of the same government? The press, which can be dismissed as biased? The scientific community, whose findings can be rejected as politically motivated?

Once this level of institutional distrust is reached, democracy becomes very difficult. Because you don't have a shared set of institutions that everyone accepts as legitimate. You have competing power centers, each claiming legitimacy, each using their power to push their version of reality.

The response to this is what we're seeing: people taking evidence-gathering into their own hands. People using technology to create their own accountability mechanisms. People refusing to accept official narratives that contradict the evidence they can see.

It's a regression from institutional democracy to something older: direct witness, personal verification, community consensus based on shared evidence. It works better than nothing, but it's not sustainable at scale. You can't run a nation of 330 million people on the basis of what crowds of people with phones happen to record.

The Question of Legitimacy Restoration

How do you restore institutional legitimacy once it's been this thoroughly eroded? You can't do it through the institutions themselves, because the problem is that the institutions are making claims that contradict people's direct experience.

You could start by having the institutions acknowledge what actually happened. That Renee Good was killed. That the shooting was caught on multiple videos. That the grainy 13-second clip doesn't show what officials claimed it shows. That the official narrative was wrong.

Then you could have some accountability. An investigation that's actually independent. Officials being held responsible. A commitment to not lying about basic facts.

But this requires a level of humility and honesty that institutions rarely exhibit, especially when admitting the truth means admitting wrongdoing. So instead, we get continued denials, continued attacks on the people who witnessed the truth, continued attempts to delegitimize evidence.

And every time that happens, the erosion gets deeper. Fewer people trust the institutions. More people turn to their tribes, to their own information sources, to their own versions of reality.

The Minneapolis residents with their phones were creating a counter-institution: a network of witnesses, a distributed archive of evidence, a shared commitment to truth-telling that didn't require official permission.

Artificial Intelligence and the Collapse of Verifiability

The Generative AI Problem

Artificial intelligence was supposed to help us solve problems. And it does, in narrow domains. It helps you write emails faster. It helps you debug code. It helps you research topics.

But it also made the misinformation problem exponentially worse. Because now, instead of needing to laboriously fake evidence, you can prompt an AI and get plausible-sounding false content in seconds. Text that sounds authoritative. Images that look real. Audio that's indistinguishable from the original.

The problem is asymmetrical. It takes seconds to generate false content. It takes hours to verify that it's false. The speed of falsehood now exceeds the speed of truth by orders of magnitude.

And this happened right when institutional truth-telling was already collapsing. So you have a situation where the institutions making claims about reality are less trustworthy than ever before, and the tools for creating false competing claims are more accessible than ever before.

The Minneapolis shooting happened in this environment. Multiple angles, multiple videos, overwhelming evidence. But it also happened in an environment where any of those videos could theoretically be deepfaked. Where you can't simply believe your own eyes anymore, because your own eyes might be deceiving you with AI-generated content.

The Detection Impossibility

There are tools that can detect AI-generated content. But they're slow. They require expertise. They cost money. And they're always behind the generation tools. As soon as someone makes a better detection algorithm, the generation tools get better at evading it.

So you reach a point where it's technically possible that anything could be AI-generated. You could go to a video and wonder: is this real? Could it be a deepfake? How would I even know?

For most people, the answer is: you wouldn't know. You'd have to trust experts. You'd have to trust institutions. And we've already established that those institutions have eroded credibility.

So you're stuck in a position of radical uncertainty. You can't know whether the evidence is real. You can't trust the institutions that might verify it. You can't verify it yourself, because you don't have the expertise or the tools.

The response of many people is to just pick a version of reality and stick with it. To choose a tribe and trust their interpretation. To accept that truth is contested and that there's no objective fact of the matter.

This is exactly what the most powerful people in the country want. A population that's given up on truth. That accepts reality as malleable. That can be told what to believe and will believe it, not because of evidence, but because it aligns with their tribe.

The Minneapolis Counterexample

But the Minneapolis shooting is a counterexample to this complete epistemic collapse. Because even though AI-generated content is possible, even though any individual video could theoretically be fake, the weight of evidence becomes undeniable.

When you have dozens of videos from different angles, recorded on different devices, showing consistent events, the probability that they're all deepfakes approaches zero. When you have eyewitnesses corroborating the videos, when you have forensic evidence, when you have background elements that would be technically difficult to fake, the lie becomes very hard to maintain.

This is what the people in Minneapolis understood. That overwhelming evidence, redundant evidence, evidence from multiple sources, becomes truth that's very hard to deny.

So they bore witness. They recorded. They created the record that made institutional denial more difficult. They did the work that institutions should have been doing but weren't.

AI-generated content can be produced much faster and more easily than it can be verified, highlighting a significant challenge in maintaining verifiability. Estimated data.

The Response: Minnesota Nice and the Reclamation of Truth

When Officials Break

There's a moment in the Minneapolis response where you see institutional officials directly contradicting their federal counterparts. The mayor tells ICE to leave. The senator tells reporters that the Trump administration's explanation doesn't make sense.

These aren't radical statements. They're normal statements. But in the context of government officials flatly contradicting each other, they become significant. They're a break from the unified front that power usually presents.

Why? Because the evidence is so overwhelming that maintaining the official lie requires too much institutional integrity. The mayor has to deal with his constituents directly. The senator has to answer to voters. They can't maintain a lie when the people they serve have seen the evidence.

So instead of defending the indefensible, they attack it. They take the side of the visible truth. They break ranks with the federal government.

This is what accountability looks like when it still works. When the evidence becomes undeniable enough that some people in power can't maintain the lie anymore. When they choose, however reluctantly, to side with reality.

The Human Cost of Bearing Witness

Renee Good is dead. The neighbors who recorded the shooting will be identifiable on video, which means they'll get attention they don't want. They might get harassed. They might get doxxed. They took a real risk to document truth.

And they did it anyway. Because they understood something that our institutions have forgotten: that truth is worth protecting. That reality is worth defending. That bearing witness is a moral act.

This shouldn't be necessary. In a functioning society, we'd have a free press, independent judiciary, transparent government processes. We wouldn't need ordinary people to risk themselves to create a record of what happened.

But we do live in this society. So people rose to the occasion. They became what the institutions failed to be.

The Possibility of Shared Reality

What's interesting about the Minnesota response is that it suggests shared reality is still possible. Despite tribalism, despite algorithms, despite institutional capture, when the evidence is overwhelming enough, people can still agree on what happened.

It requires: Multiple independent sources. Overwhelming redundancy of evidence. Official contradiction that makes denial harder. Cultural context that values truth over tribalism.

Minnesota has some of these factors. It's a relatively civic-minded state, with strong institutional traditions, with a population that votes and engages with local government. It doesn't have the level of partisan polarization of some other states.

But the fact that it worked at all, in any context, suggests that the idea of shared reality isn't dead. It's just much harder to maintain. It requires more evidence. It requires more coordination. It requires people to actively choose truth over comfortable lies.

The people in Minneapolis made that choice. So did some institutional officials. So did some portion of the population that rejected the official narrative.

The Broader Pattern: Trumpism and the Contempt for Reality

The Explicit Rejection of Fact

When Donald Trump took office, he brought with him an explicit ideology of contempt for reality. Not just for any particular reality, but for the very concept that objective reality exists.

We're not talking about different interpretations of policy. We're talking about basic claims of fact. Weather. Crowd sizes. Electoral results. The degree to which this has been systematic and explicit is unprecedented in modern American politics.

And it's been effective. In the context of partisan media that's already encouraging people to reject mainstream sources, having the president explicitly tell you that your eyes are lying to you creates permission structures. If the president says the evidence is fake, then maybe it is. Maybe I can trust my tribal news source more than my own observation.

The Acceleration Through Social Media

Trump didn't invent contempt for truth. But he weaponized it and accelerated it through social media in ways that were previously impossible. A president can now broadcast directly to millions of followers without any intermediary. Can make claims, no matter how false, and have them amplified by algorithms optimized for engagement.

The traditional media couldn't keep up. By the time a fact-checker corrected a false claim, it had already spread to millions of people and been reinforced by tribal media. The correction reached a fraction of the people the original lie reached.

This is how the information environment changed. Not through gradual erosion, but through systematic exploitation of technological affordances in service of a contempt for reality.

The Institutional Collaboration

What's notable is how little resistance institutions put up. When a president says obviously false things, you'd expect major institutional backlash. Congressional Republicans denying the facts, media refuting the claims, bureaucrats refusing to implement obviously false assertions.

But that didn't happen. Or it happened inconsistently, at the margins. The mainstream media fact-checked, but couldn't compete with the reach of the president's direct broadcasts. Congress largely went along, out of partisan loyalty. Bureaucrats implemented policies on the basis of false premises.

The institutions that were supposed to check power either failed or actively collaborated with the assault on reality.

So ordinary people had to do the work. Had to record. Had to document. Had to create evidence that was so overwhelming that it became harder to deny.

Beyond Minneapolis: The Stakes of a Shared Reality

Democracy Requires Consensus on Facts

You can have a functioning democracy where people disagree about values. Where people want different outcomes. Where people have different priorities. But you need a baseline consensus on facts.

If half the country believes inflation is 20% and half believes it's 3%, you can't make policy. You can't debate. You can't deliberate. You don't have democracy, you have two groups talking past each other.

The assault on reality is an assault on democracy itself. Because it's trying to create the conditions where facts don't exist, where every claim is contingent, where there's no shared ground.

Once you lose that shared ground, you lose the ability to govern together. You're left with power contests, with might-makes-right, with whoever has the biggest megaphone winning. That's not democracy. That's authoritarianism.

The Technological Hopelessness

The frustrating thing about the technological dimension is that the tools exist to do better. You could build platforms that highlight verified sources, that slow the spread of misinformation, that create friction for sharing unverified claims.

You could create better deepfake detection. You could require authentication for official accounts. You could build reputation systems that reward accurate information and penalize false information.

But this requires choosing accuracy over engagement, truth over profit. And the entire industry structure is set up to optimize for the opposite.

So the technological problem won't be solved technologically. It'll be solved politically, if it's solved at all. Which means it requires regulation, which means it requires political will, which is increasingly scarce.

The people in Minneapolis who recorded the truth were working around the fact that the technology of communication has been optimized to spread lies faster than truth. They were creating redundancy, documentation, evidence. They were doing the work that the institutions should be doing.

The Personal Responsibility

But there's also a personal responsibility here. For each of us, individually, to care about what's actually true. To be willing to look at evidence that contradicts what we want to believe. To accept that we might be wrong. To update our beliefs when the evidence demands it.

This is hard. It's much easier to stay in your tribe, to accept the version of reality you're given, to assume that anything contradicting it is lies.

But democracy requires this effort. Citizenship requires this effort. The people in Minneapolis made the effort. They recorded. They risked themselves. They said: I believe reality is important enough to fight for.

That has to be infectious. It has to spread. Because if it doesn't, if most people give up on truth and retreat into tribes, then the experiment of democracy and shared reality dies.

It's not dead yet. The Minneapolis shooting shows that. But it's on life support, and we're not sure who's going to keep it alive.

Looking Forward: Can Shared Reality Survive?

The Pessimistic Case

Let's be honest about what we're facing. The incentive structures are all aligned against truth. Profit-motivated platforms have no reason to slow misinformation. Political movements benefit from a confused and fractured electorate. Elites have incentives to deny reality when reality is that they're failing.

Technology is getting better at creating false content and worse at detecting it. Institutions are losing credibility. Tribal identity increasingly overrides factual belief. And the political response is to attack truth-tellers rather than fix the institutions.

In this environment, it's hard to imagine a path where shared reality is restored. The forces eroding it are much stronger than the forces trying to maintain it. And the people in Minneapolis, however heroic, are a handful of ordinary people against global technology companies and federal governments.

From this perspective, the Minneapolis moment is a rearguard action. A last stand before consensus reality collapses into tribal epistemic warfare.

The Optimistic Possibility

But there's another possibility. That the collapse of institutional truth-telling creates an opening for peer-to-peer verification. That the people who lose trust in institutions also lose trust in tribal media. That enough evidence accumulates that denial becomes impossible.

The Minneapolis shooting could be the first of many moments where the weight of video evidence overwhelms the official narrative. As more people get phones, as video becomes more ubiquitous, as the friction of recording approaches zero, the ability of powerful institutions to maintain false narratives decreases.

It's possible that we're not heading toward a post-truth world, but toward a more granular, distributed, verified-by-community version of truth. Where no single institution controls the narrative, but the aggregate evidence points toward what actually happened.

This would require some things we don't have: a commitment to truth over tribalism, willingness to accept evidence that contradicts tribal identity, technological infrastructure that prioritizes accuracy over engagement. But it's possible.

What Would Need to Change

For shared reality to survive, several things would need to change.

First, the platforms would need to be regulated or restructured to not optimize for engagement at the expense of accuracy. This seems unlikely given current political trends, but it's necessary.

Second, the media would need to rebuild credibility by actually being accurate and transparent. This requires investment, which requires revenue, which is hard to come by in the current model. But it's necessary.

Third, political leadership would need to commit to truth, even when truth is inconvenient. This requires a level of integrity that's increasingly rare. But it's necessary.

Fourth, people would need to accept that they might be wrong, and update their beliefs when evidence demands it. This is hard, psychologically. But it's necessary.

And fifth, communities would need to do what Minneapolis did: bear witness, create evidence, build records that are harder to deny. This is what ordinary people can do, and what is already happening.

The Minneapolis shooting shows what's possible when enough people care enough about truth to risk themselves for it. The question is whether that becomes infectious, whether it spreads, whether it becomes the norm rather than the exception.

There's no guarantee. But there's possibility. And in a time of deep institutional failure and technological assault on reality, possibility is something.

The Radical Act of Witnessing

Why This Matters Beyond Minneapolis

The Minneapolis shooting will fade from headlines. The immediate controversy will die down. But the principle it established remains important. That ordinary people bearing witness to power matters. That evidence created by citizens can override official narratives. That reality, when documented thoroughly enough, is hard to deny.

This principle applies to every instance of institutional power exercising coercion. Every police shooting, every government action, every abuse by authority. The ability of ordinary people to create a record, to document what happened, to make it harder for institutions to lie, is foundational to any form of accountability.

And in a time when institutions have lost the credibility to be trusted, when tribal media can't be trusted, when official channels can't be trusted, distributed citizen documentation becomes the only reliable source of truth.

This is the responsibility and the power of every person who witnesses something important. Pull out your phone. Record. Make sure the truth survives the night.

The Future of Verification

We're in the middle of a technological and epistemological crisis. The tools for creating false information are becoming more sophisticated. The tools for verifying truth are becoming inadequate. The institutions traditionally responsible for truth-telling are losing credibility.

The resolution of this crisis will probably be messy. It might involve some regression to pre-technological forms of verification: community consensus, personal networks, local institutions. It might involve new technologies designed to verify rather than deceive. It might involve a complete restructuring of media and information architecture.

But whatever happens, the principle that Minneapolis demonstrated will remain true. That people bearing witness, creating records, building evidence is not optional. It's foundational to the possibility of truth surviving in a hostile information environment.

The Cost and the Necessity

We should be clear that this is a cost. In a functioning society, ordinary people shouldn't have to risk themselves to document government actions. In a functioning society, we'd have a free press, independent oversight, transparent institutions. We'd have institutional truth-telling that doesn't require street-level verification.

But we don't have that. So people have to do the work themselves. They have to pull out their phones. They have to record. They have to share. They have to risk their names, their safety, their social standing to preserve the record of what actually happened.

Renee Good risked more than that. She risked her life. And she lost it. Her death is the ultimate cost of a society where ordinary people have to be the check on power.

But her death also illuminated something true. That people still care about reality. That despite everything, despite tribalism and algorithms and institutional failure, ordinary people will still stand in the gap and bear witness.

That's the Minneapolis moment. That's what survives, even as everything else crumbles.

FAQ

What does "shared reality" mean in the context of modern politics?

Shared reality refers to a baseline consensus on basic facts that members of a democracy agree on, regardless of their political differences. In 2025, this has eroded significantly due to algorithmic fragmentation, institutional distrust, and deliberate disinformation campaigns. When people experience completely different information ecosystems and doubt the same evidence differently, shared reality becomes impossible, and democratic governance becomes severely compromised.

How have social media algorithms contributed to the erosion of shared truth?

Social media algorithms are optimized for engagement rather than accuracy. When platforms show users content that confirms their existing beliefs, people become isolated in filter bubbles where contradictory evidence never appears. This creates different information worlds for people living in the same community. Over time, people develop completely different factual understandings of the same events, making democratic deliberation and consensus-building nearly impossible.

Why did ordinary citizens in Minneapolis recording videos matter more than official statements?

Multiple videos from different angles created redundant evidence that was difficult to dismiss as fake or out of context. When official narratives contradicted what dozens of people independently recorded, the weight of distributed citizen documentation became more credible than institutional claims. This demonstrates that in environments where institutions have lost credibility, peer-to-peer verification can replace institutional truth-telling.

What is the relationship between artificial intelligence and deepfakes in undermining trust?

Generative AI has made creating convincing false content dramatically easier and cheaper. Simultaneously, it has introduced justified doubt about whether any given video or image is authentic. This creates an asymmetrical epistemic problem: creating false evidence takes seconds, while verifying authentic evidence takes hours or longer. In this environment, people rationally distrust all evidence, which benefits those in power who want to control narratives.

How does tribal identity affect people's willingness to accept contradictory evidence?

When your tribal identity becomes tied to your factual beliefs, admitting you were wrong feels like betraying your community. Psychological research shows that people under tribal pressure often double down on false beliefs rather than update them, because updating would require public admission of error and loss of social standing within their group. This makes it extremely difficult to build consensus on facts when those facts contradict tribal narratives.

What would it take to restore institutional credibility around truth-telling?

Restoring institutional credibility would require: transparent acknowledgment of past lies, genuine accountability for officials who spread disinformation, investment in journalism and fact-checking, regulation of platforms to prioritize accuracy over engagement, political leadership that commits to truth even when inconvenient, and time for these commitments to demonstrate results. Currently, none of these conditions are being met at scale, making restoration difficult.

Can shared reality survive technological change and political polarization?

Shared reality can survive if enough people commit to evidence-based reasoning, if some institutions rebuild credibility through transparency and accuracy, if platforms are regulated to reduce misinformation spread, and if communities continue the work Minneapolis residents demonstrated: creating overwhelming, redundant documentation of important events. However, without significant changes to incentive structures and political culture, the erosion of shared reality will likely continue.

Conclusion: The Minneapolis Lesson

Renee Nicole Good is dead. She was killed by federal agents during an immigration raid in Minneapolis. The official narrative claimed one version of events. Multiple videos documented a different reality. Ordinary people with phones became the only reliable source of truth.

This is where we are in 2025. Not in a post-truth world, because truth still exists and still matters. But in a world where institutions can no longer be trusted to tell it, where tribal media distorts it, where technology makes it easier to create lies than to verify facts, where political movements explicitly reject it.

Instead, truth survives through the courage of ordinary people. Through neighbors recording. Through legal observers documenting. Through families telling what they saw. Through the refusal of a community to accept an official lie when the evidence contradicted it.

This shouldn't be necessary. In a functioning society with healthy institutions, a free press, and transparent government, shared reality would be protected by those institutions. We wouldn't need ordinary people to risk themselves to preserve the factual record.

But we do live in this society. And so people rose to the occasion. They became journalists when journalism failed. They became fact-checkers when fact-checking became impossible. They became the check on power when official checks failed.

That's the Minneapolis moment. That's what it looks like when citizens still believe that reality matters more than comfortable lies. That's what it looks like when truth becomes a resistance act.

The question is whether this becomes the norm or remains the exception. Whether enough people start bearing witness, documenting, refusing to accept official narratives without evidence. Whether communities continue what Minneapolis started: the work of creating overwhelming, undeniable, distributed truth.

If they do, shared reality survives. Not as something protected by institutions, but as something defended by communities. Not as something guaranteed, but as something worth fighting for.

Renee Good learned this lesson too late. Her death illuminates what it costs to bear witness to power. But it also shows what's possible when people decide that truth is worth the risk.

That's the lesson to carry forward: reality still matters. And we're the ones responsible for protecting it.

Key Takeaways

- Shared reality is collapsing due to algorithmic fragmentation, institutional distrust, and deliberate disinformation—but ordinary people bearing witness can still defend documented truth

- Technology has made creating false evidence exponentially easier while fact-checking lags behind, creating an asymmetrical epistemic crisis

- When institutions abandon truth-telling, citizens must do the work—the Minneapolis shooting shows how redundant documentation from multiple sources becomes more credible than official narratives

- Political leadership explicitly rejecting reality, combined with platforms dismantling misinformation protections, has created conditions where Orwellian narrative control is technically possible

- Democracy requires baseline factual consensus—without it, you have tribal information warfare instead of deliberation, and whoever controls the biggest megaphone wins

Related Articles

- How Political Narratives Get Rewritten Online: The Disinformation Crisis [2025]

- The Viral Food Delivery Reddit Scam: How AI Fooled Millions [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: UK Regulation and AI Abuse [2025]

- AI Operating Systems: The Next Platform Battle & App Ecosystem

- Grok's Explicit Content Problem: AI Safety at the Breaking Point [2025]

- AI Models Learning Through Self-Generated Questions [2025]

![Reality Still Matters: How Truth Survives Technology and Politics [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/reality-still-matters-how-truth-survives-technology-and-poli/image-1-1767964061915.jpg)