ICE Enforcement Safety Guide: Know Your Rights [2025]

It's 6 AM on a weekday morning. Federal agents knock on your door. Your heart stops. Within seconds, your entire world shifts into crisis mode.

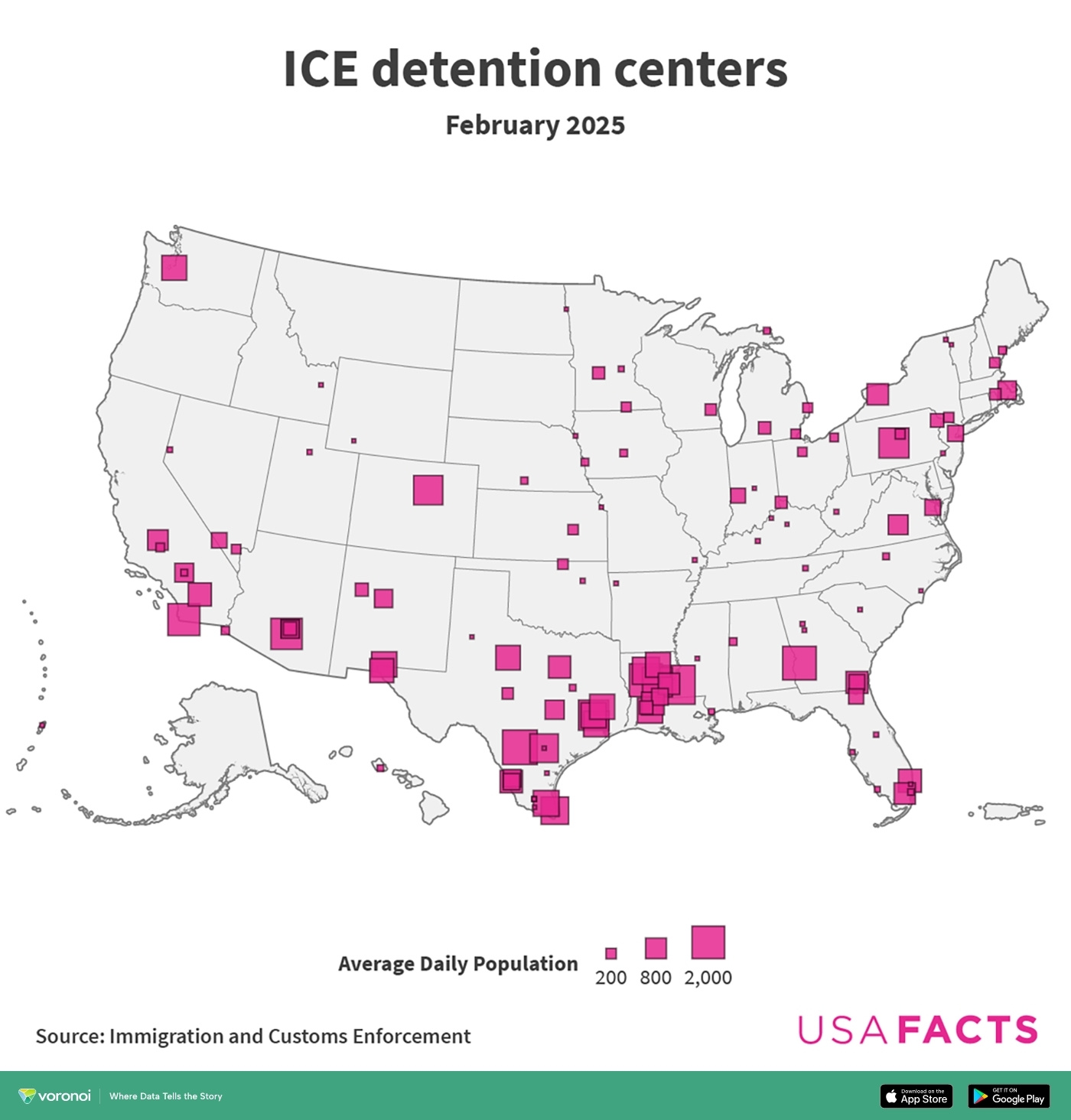

This isn't hypothetical anymore. Across American communities, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations have escalated to levels not seen in years. Minneapolis has seen deployments that dwarf the entire local police presence. Portland experienced armed confrontations that left civilians hospitalized. And these incidents represent just the visible tip of a much larger enforcement apparatus that's reshaping daily life for millions of Americans.

But here's what matters right now: you have options. You have rights. And even if you're terrified (which is completely reasonable), there are concrete steps you can take to protect yourself, your family, and your community.

The challenge is that the landscape has shifted faster than most resources have adapted. Traditional advice about "don't open the door" still holds legal weight, but it doesn't account for the intensity and unpredictability of current enforcement operations. Federal agents have been documented violating constitutional rights with increasing frequency. Local law enforcement agencies that used to maintain some checks on federal overreach are being outmaneuvered by the sheer scale of ICE deployments.

This guide walks through the practical, tactical, and strategic approaches to navigating this reality. Whether you're directly at risk, supporting someone who is, or simply concerned about what's happening in your community, understanding these frameworks can mean the difference between safety and catastrophe.

TL; DR

- Constitutional protections still matter: ICE agents typically need judicial warrants to enter homes, not just administrative warrants, but enforcement has become increasingly chaotic and unpredictable

- Document everything: Recording interactions with federal agents is legal and crucial for accountability, though current safety risks mean personal risk assessment is essential

- Build community infrastructure: Emergency contact lists, trusted support networks, and prepared documentation can save lives during enforcement operations

- Know the legal landscape: Immigration violations are generally civil, not criminal offenses, which affects your interaction strategy and legal options

- Risk assessment is individual: Your vulnerability depends on immigration status, citizenship, location, visibility, and current threat levels in your area

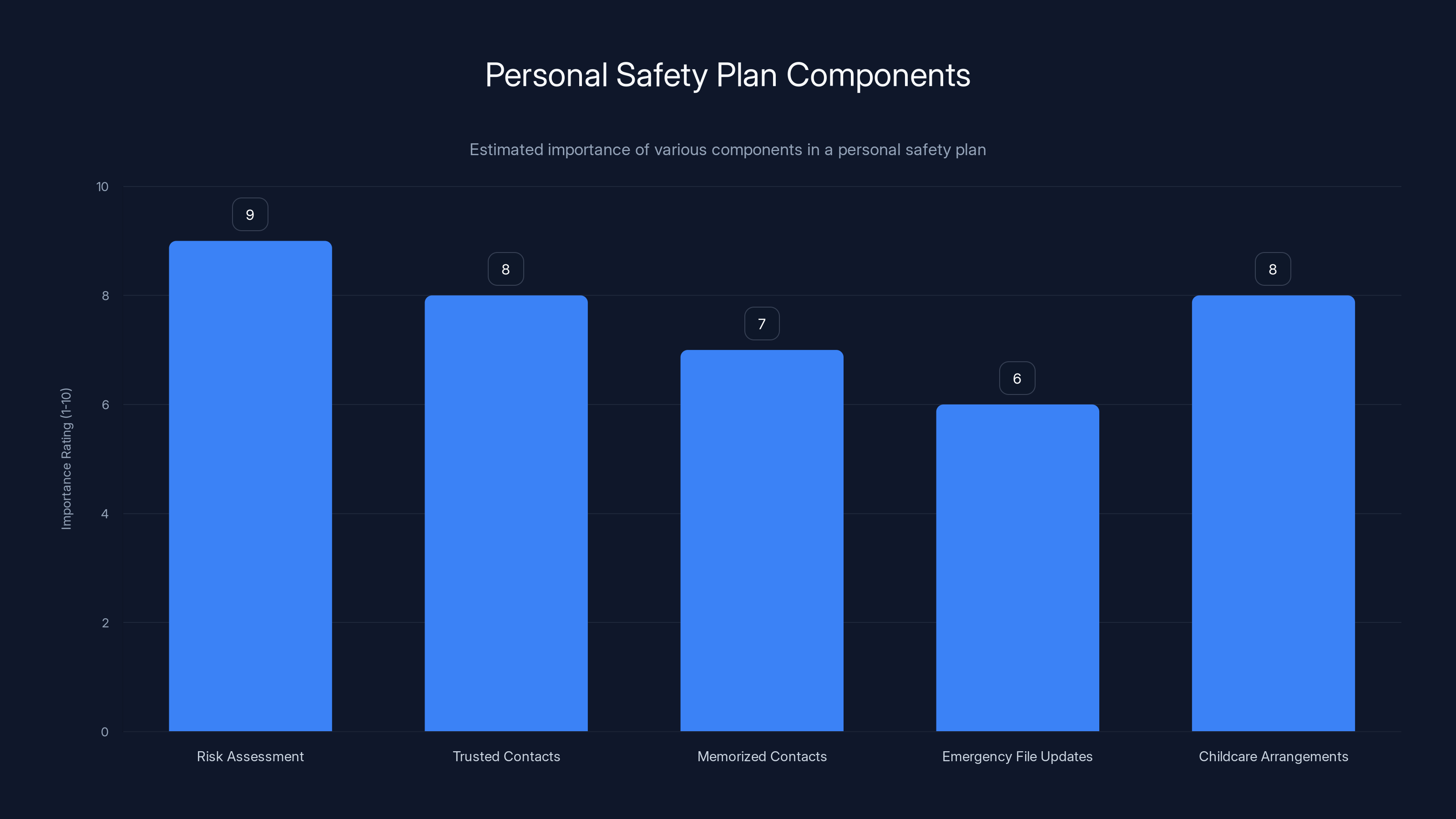

Risk assessment and establishing trusted contacts are the most critical components of a personal safety plan. Estimated data based on typical safety plan priorities.

Understanding the Current Enforcement Landscape

The past year has fundamentally changed how ICE operates in American communities. This isn't just an increase in enforcement activity, though that's certainly happening. It's a shift in the entire operational framework.

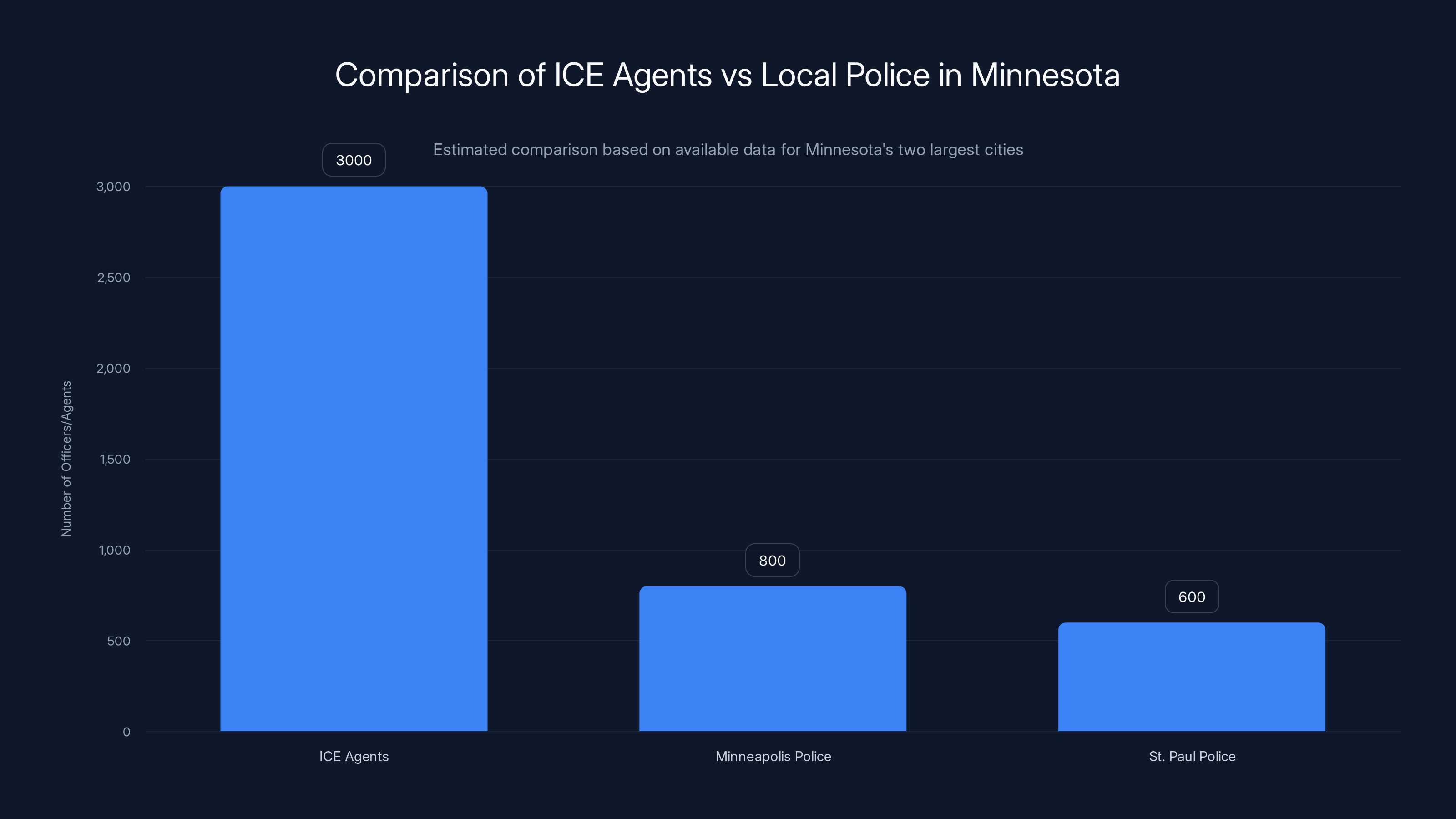

Consider the numbers. ICE deployed 2,000 agents to Minnesota alone, with plans to surge an additional 1,000. Minnesota's two largest cities combined have fewer police officers than this federal deployment. This creates a situation where federal immigration agents literally outnumber local law enforcement in geographic areas where they're operating. That ratio matters enormously. Local police departments, whatever their limitations, typically operate under some community oversight and local accountability structures. Federal immigration agents, deployed en masse from outside the region, operate under different command structures with minimal local accountability.

The Department of Homeland Security's enforcement budget has expanded substantially. This isn't just more agents. It's more resources, more operational freedom, and more capacity to sustain extended campaigns in specific regions. When you have that kind of resource commitment, operations become more aggressive by necessity. You're trying to justify that investment.

What's particularly unsettling is the documented pattern of these operations extending beyond the intended targets. U.S. citizens have been arrested during ICE operations. Documented immigrants with legal status have been detained. The net cast by enforcement operations tends to be much wider than the specific legal targets.

Add to this the well-documented history of violence and constitutional violations by both ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). These aren't isolated incidents. They represent a pattern of aggression, inadequate oversight, and minimal accountability that has characterized these agencies for years. The difference now is the scale, the intensity, and the reduced restraint.

Agencies justify this expansion through national security and public safety rhetoric. But that framing obscures the actual risk calculus. Immigration violations are almost entirely civil matters, not criminal offenses. You're not dealing with law enforcement responding to crimes. You're dealing with administrative enforcement of civil immigration code.

That distinction matters legally, procedurally, and ethically. It's the foundation of everything that follows.

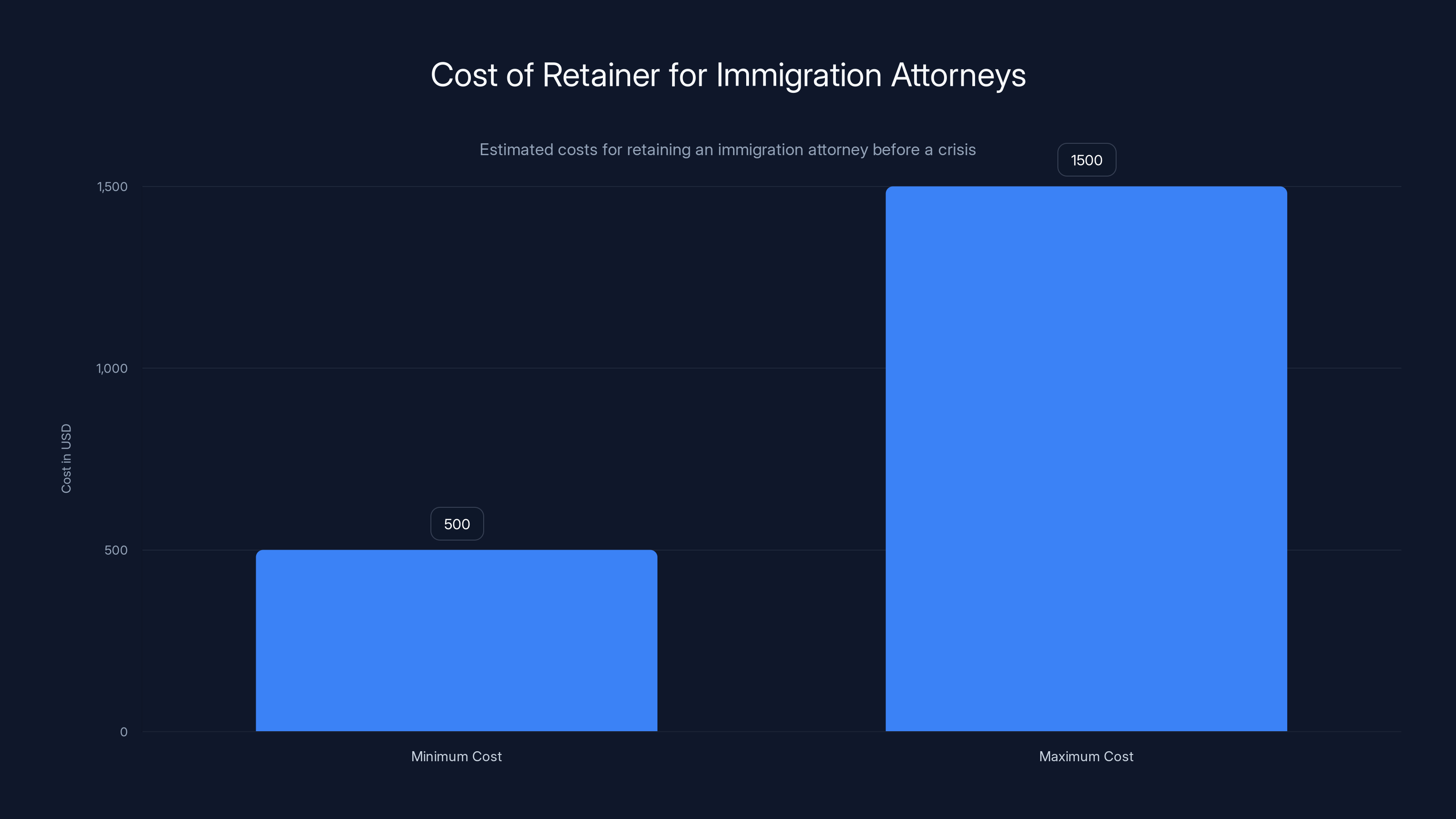

The cost of retaining an immigration attorney ranges from

Your Constitutional Rights During ICE Interactions

Let's start with what the law actually says, because this foundation hasn't changed even as enforcement has become more chaotic.

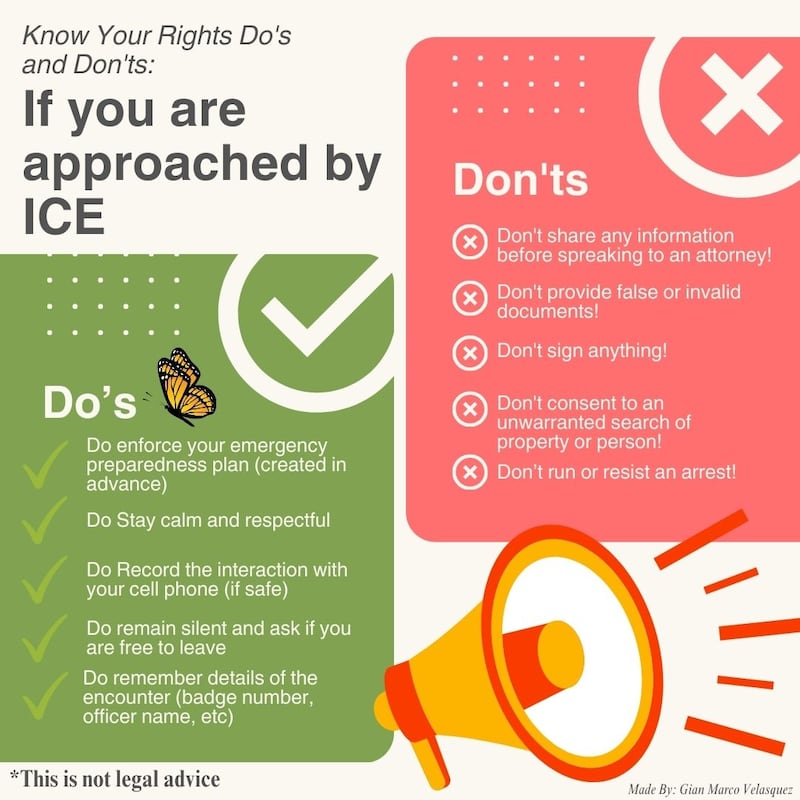

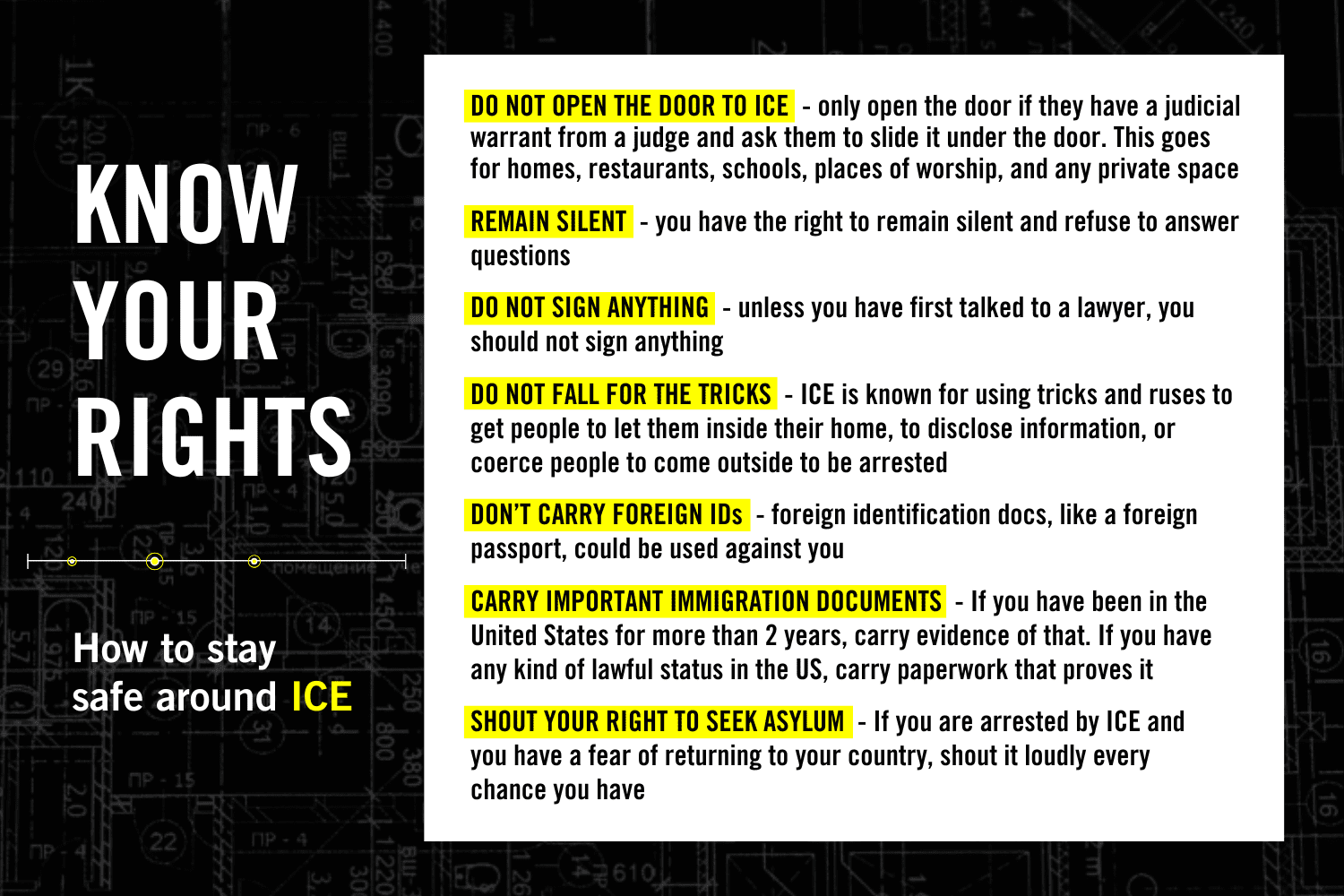

First principle: ICE agents need a judicial warrant signed by a judge to enter your home without permission. This is the critical distinction that traditional guidance emphasizes. An administrative warrant that ICE agents typically carry does not give them the authority to enter a home. It's a civil document, not a judicial authorization. This matters because it creates a legal boundary. Agents cannot legally cross your threshold without consent if they only have administrative paperwork.

Second principle: You have the right to refuse consent to search. You can say no. You can close the door. You can tell agents they may not enter your home. This right exists whether you're a citizen or not. Exercising your constitutional rights is not an admission of guilt. It's not an act of defiance. It's a fundamental legal protection.

Third principle: You have the right to remain silent. You're not legally required to answer questions from immigration agents. You can provide your name if asked, but beyond that, you can decline to answer. This is true for citizens and non-citizens alike. The Fifth Amendment protects everyone in this scenario.

Fourth principle: You have the right to record interactions with law enforcement in public spaces. This is legal. This is protected speech. Recording can be crucial documentation, especially given the pattern of constitutional violations. Video evidence is the most effective tool for accountability when violations occur.

Fifth principle: Refusing to consent to a search is not probable cause for arrest. Agents cannot arrest you simply because you declined a search or refused to answer questions. They would need independent grounds for arrest based on actual evidence of a crime or immigration violation.

Now, here's the massive caveat: all of these rights exist on paper. Enforcement of these rights depends on multiple factors: whether you can afford legal representation, whether local courts are willing to enforce constitutional protections against federal agents, whether agents themselves recognize or respect these boundaries, and whether you survive any violent confrontation during enforcement.

The documented pattern shows that ICE and CBP have increasingly violated these constitutional protections. Agents have entered homes without proper warrants. Agents have arrested people for simply asking questions or refusing searches. Agents have used force in situations that didn't justify force. And the accountability mechanisms for these violations are remarkably weak.

You have these rights. But exercising them carries real risk in the current environment, and that risk isn't equally distributed. A U.S. citizen has different protections than a non-citizen. A person with documentation has different vulnerability than someone without. A person in a community with strong civil rights advocacy has different support structures than someone isolated.

These rights are foundational, but they're not sufficient protection by themselves.

Creating a Personal Safety Plan

Beyond constitutional knowledge, you need an actual plan. This isn't paranoia. This is practical preparation for a scenario that's increasingly likely in many communities.

Start with identifying your personal risk profile. Are you in direct immigration enforcement targeting? Are you a U.S. citizen? Are you in a state or city where ICE operations are currently active? Are you visibly identifiable as someone from a particular community? Are you involved in activism or public visibility that makes you a higher-profile target? Do you have dependents who rely on you?

Your risk level determines the intensity of your preparation. Someone at direct risk of deportation needs more extensive safety infrastructure than someone with secure immigration status. A person with young children needs different contingency plans than someone without dependents. These aren't static categories. Your risk can change based on operational tempo, political circumstances, and personal decisions.

Once you've assessed your risk level, build your emergency infrastructure. This starts with trusted contacts. Not just family members, but people you can call immediately in a crisis situation. Identify at least three people who:

- Live in different geographic locations (so they're not simultaneously affected by the same operation)

- Are available on very short notice

- Understand what you're asking them to do

- Are willing to act as emergency guardians or power of attorney if needed

- Have the capacity to manage money, documents, or childcare in an emergency

Memorize their phone numbers. Don't rely on having your phone available. In past ICE operations, people have been separated from their phones, their belongings, and sometimes their children. Memorized contact information is your lifeline when everything else is inaccessible.

Second, ensure your children's school and daycare have these emergency contacts on file. Make it clear that these people have authorization to pick up your children if you're unable to do so. Get this in writing. Make sure the people named actually understand they might need to assume custody temporarily.

Third, if you're at specific risk of deportation, consider establishing a power of attorney and naming a guardian for minor children. This is legal preparation that happens through proper channels. An attorney can establish documents that give trusted people the authority to manage your financial and legal affairs if you're detained or deported. A guardianship establishes who has custody of your children if you're unable to care for them. These documents are legally binding and protect your family's interests in the worst-case scenario.

Fourth, gather your critical documents. This includes birth certificates, immigration documents, medical records, school records, and financial documents. Physical copies matter because digital access might be cut off. Consider storing copies with your trusted emergency contact or in a secure location separate from your home. If you're detained, you might not have access to your home for an extended period.

Fifth, have a communication plan. How will you contact your emergency support network? What information will you provide? What are they authorized to do with that information? If you have undocumented status, how will you communicate with a lawyer? Many immigration attorneys recommend having a lawyer on retainer specifically for emergency situations. It might cost

Sixth, establish a code word or signal that indicates you need emergency response. This is practical tradecraft. If you're detained and someone calls asking if you're okay, your pre-arranged signal tells them whether you're actually fine or whether they need to activate the emergency plan. This protects against someone impersonating an official or creating a false sense of security.

Seventh, have a financial contingency plan. If you're detained or deported, who handles your rent or mortgage? Who manages your bills? Who feeds your pets? These practical details matter enormously in extended detention scenarios. A person detained for weeks or months can lose their housing if bills go unpaid. They can lose employment if they don't show up for work. They can lose custody of children if they can't arrange childcare. Planning for these contingencies is protective.

Estimated data shows that having

Documentation and Recording Best Practices

If an ICE interaction occurs, documentation becomes critical. Video and audio recording of these interactions serves multiple purposes: it creates evidence for potential legal challenges, it deters some forms of misconduct by agents, and it provides accountability documentation if violations occur.

Recording law varies by state. In most states, you can record a conversation if you're a party to that conversation, even if the other party hasn't consented. Some states require all parties to consent to recording. Regardless of the specific law, recording an interaction happening in a public space where you have a right to be is generally legal. Police and federal agents often claim that recording is illegal when it's actually protected. Knowing your state's specific law is helpful, but the general principle is that you have more recording rights than agents will claim.

If you're recording, do it visibly. Having your phone out recording creates a deterrent effect and makes it clear you're documenting the interaction. It also makes it harder for agents to claim later that they didn't know they were being recorded.

What should you record? Everything that's happening. The presence of agents, their conduct, their statements, the interaction with other people, the conditions. Video is better than audio because it provides visual evidence of what occurred. If you're recording audio only, describe what's happening verbally as you record.

Protect your recording. If you're arrested or detained, your phone might be seized. Get the recording off your phone as quickly as possible. Send it to someone else. Upload it to a cloud service. The longer the recording stays only on your phone, the higher the risk it gets lost, deleted, or seized.

Beyond recording, document in writing what happened. If you have access to paper and pen during detention, write down dates, times, names of agents if visible, what was said, what happened, physical injuries, any force used, any rights violations. If you don't have access to writing materials during detention, write it down as soon as you're released or transferred. Memory degrades quickly. Written documentation creates a contemporaneous record that's much more credible than recollection weeks or months later.

If you witness an ICE interaction involving someone else, your documentation matters. You're an independent witness. Your video, your written account, your willingness to provide a statement—all of this creates accountability documentation. In cases where violations occur, witness documentation is often the difference between a violation that gets ignored and a violation that creates legal consequences.

Keep records organized. Put dates on all documentation. Store them safely. If a legal challenge occurs, you'll need to produce these records. The more thorough and organized your documentation, the more useful it is for legal proceedings.

Understanding Your Interactions with ICE Agents

If you encounter ICE agents, there are specific tactical approaches to the interaction. These are based on legal principle but also practical reality of how these interactions unfold.

First, identify whether the agents are actually ICE. This matters. There are variations between different federal agencies, and misidentification is possible. Ask to see identification. Look for the specific agency name. ICE agents will have identification from the Department of Homeland Security. CBP agents are different. Border Patrol agents are different. Knowing who you're interacting with informs your legal approach.

Second, don't open your door for an administrative warrant. If agents are at your door with only an administrative warrant, you can refuse them entry. This is legally clear. Tell them: "I do not consent to entry. You need a judicial warrant signed by a judge." You can say this through a closed door. You don't need to let them in. If they force entry anyway, that's a rights violation. You've established that clearly on record.

Third, don't answer questions beyond identifying yourself. You're not required to explain your immigration status, your employment, your background, or anything else. You can say: "I don't answer questions. I want to speak to a lawyer." Repeating this calmly and consistently is your right. Agents will try to persuade you, pressure you, and sometimes threaten you. But your right to remain silent is absolute.

Fourth, if you're in a vehicle during an interaction, be aware of your options. You can refuse consent to search your vehicle. You can ask if you're free to leave. You can say you want to speak to a lawyer. But you also need to assess physical safety. If agents have weapons drawn or you're in an unsafe situation, de-escalation and compliance with immediate physical commands is more important than asserting rights. Once you're in a safer situation, you can reassert those rights.

Fifth, if agents attempt to detain you, you're entering a different legal situation. Detention is more serious than an investigative stop. If detained, you're generally permitted to ask whether you're free to leave and whether you're being arrested. If detained without arrest, there are time limits (typically 24-48 hours) within which you must be released or charged. If arrested, you have the right to counsel. But these rights are only meaningful if you exercise them.

Sixth, be aware that immigration agents sometimes misrepresent their authority. They might claim they can enter your home when they can't. They might claim you're required to answer questions when you're not. They might claim that refusing consent is illegal. None of these claims are accurate, but agents make them frequently. Knowing the actual law protects you from being manipulated into voluntarily giving up your rights.

Seventh, don't lie to agents. This is important. Lying to federal agents can be prosecuted as an independent offense separate from immigration violations. If you don't want to answer, you assert your right to remain silent. But if you do answer, you answer truthfully. Lying creates additional criminal exposure.

Eighth, understand that these interactions can escalate physically. Recent incidents involving ICE and CBP have included shootings, even of people who weren't resisting or threatening. This isn't about fairness. It's about recognizing that these operations are increasingly militarized and unpredictable. If there's immediate physical danger, protecting your physical safety takes priority over asserting constitutional rights. Once you're in a safer situation, you can reassert those rights.

In Minnesota, ICE agents outnumber local police significantly, with 3,000 agents compared to a combined 1,400 officers in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Estimated data based on narrative.

Supporting Others in Your Community

You might not be directly at risk, but people around you might be. Supporting them requires both practical action and understanding your own limitations and risks.

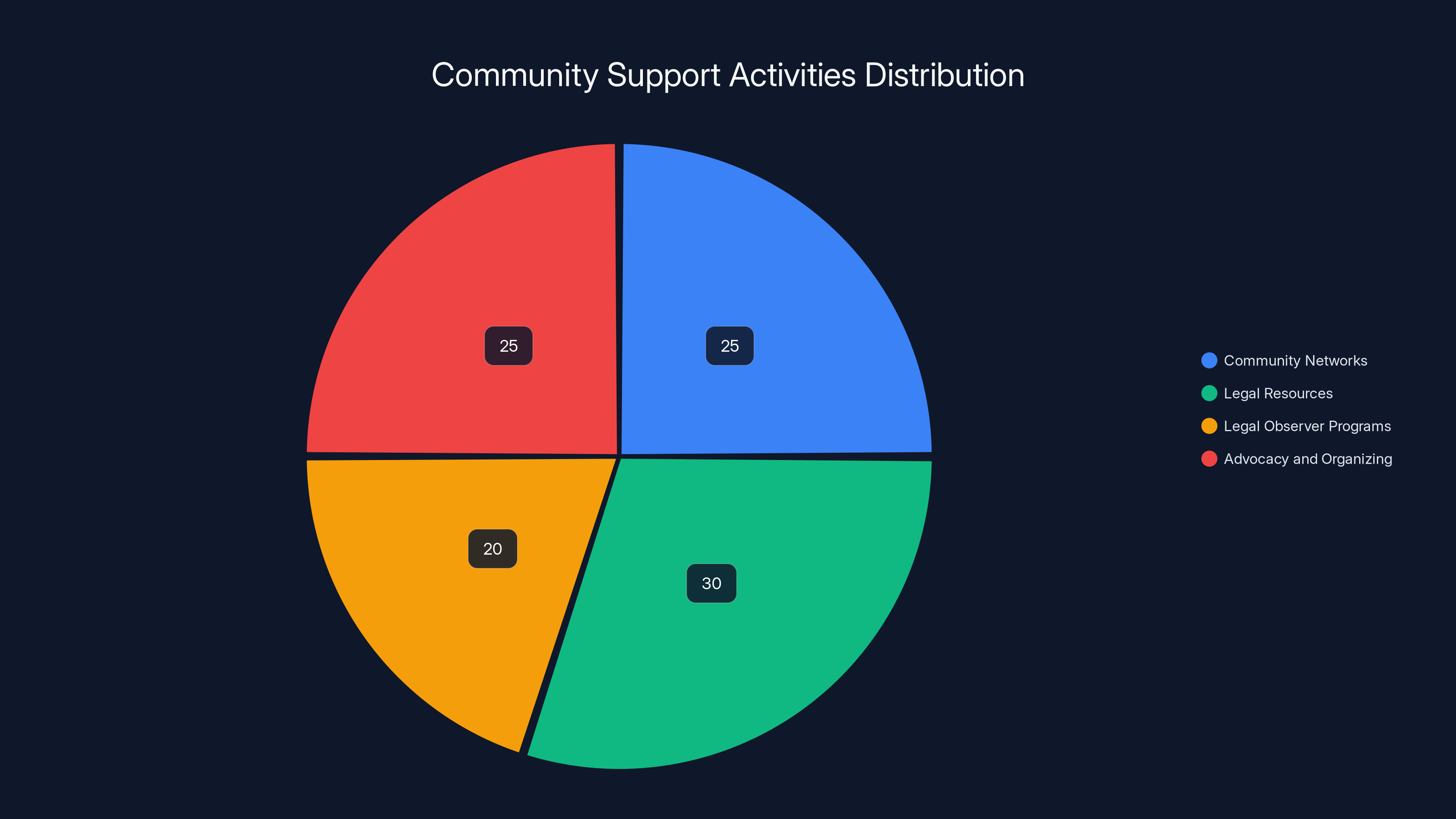

First, establish community networks. This starts with communication infrastructure. Neighborhood group chats, community organizing groups, faith-based networks, or mutual aid organizations can coordinate response when ICE operations occur in the area. When people know that there's an established community infrastructure responding to enforcement, it changes the whole dynamic. It means detention isn't isolation. It means families aren't separated without backup plans. It means there are immediate lawyers, legal observers, and support.

Second, know the resources in your community. Identify legal organizations that provide immigration defense. Know their phone numbers, their availability, their capacity. Some organizations have rapid response teams that can be on scene when ICE operations are happening. Some offer free or low-cost legal consultation. Some coordinate community monitoring of detention facilities. Knowing these resources before an emergency means you can actually access them when minutes matter.

Third, participate in or support legal observer programs. These are organized groups of people trained to observe police and federal enforcement activities, document what happens, identify violations, and provide testimony if needed. Legal observers don't intervene in the enforcement action itself, but they create an accountability presence. Their documentation has been used successfully in court challenges to enforcement tactics.

Fourth, support advocacy and organizing work. Organizations working on immigration policy, civil rights, and community protection do the long-term political work that constrains enforcement. This might be financial support, volunteering, participation in advocacy campaigns, or simply elevating the visibility of these issues. This work doesn't prevent individual enforcement actions, but it shapes the broader environment in which enforcement operates.

Fifth, provide concrete support to people affected by enforcement. If someone is detained, can you help their family? Can you handle their bills, their childcare, their employment communication? Can you help get them legal representation? Practical support is often the difference between someone's life falling apart during detention and their life remaining stable.

Sixth, understand the limits of community protection. You can create infrastructure, documentation, and advocacy. You can provide support. You can't prevent all enforcement actions. You might not be able to prevent all violations. Sometimes despite your best efforts, people are still detained or deported. That's not failure. That's the reality of an aggressive enforcement system. The infrastructure still matters because it shapes the outcomes of those situations.

Seventh, protect yourself while supporting others. If you're participating in legal observation or community monitoring, understand the risks to yourself. Federal agents don't always tolerate observation of their operations. There are documented cases of legal observers being harassed, threatened, or arrested for filming federal enforcement. This doesn't mean you shouldn't do it. But it means you should do it strategically, with knowledge of your rights, and with backup from other observers.

The Border and Travel Considerations

If you're at immigration risk, travel to the border creates additional vulnerability. Border Patrol has broad authority in the border region, and ICE operations have extended into areas far from the actual border.

Technically, Border Patrol operates within roughly 100 miles of the international border. Practically, ICE operates nationwide. But the border region itself represents elevated risk. If you're traveling to or through the border region and you have immigration concerns, understand that checkpoints exist. Border Patrol conducts stops far from the actual border. These interactions are governed by different legal frameworks than internal enforcement.

If you're traveling by car through a border region, you can refuse consent to search your vehicle, but you cannot refuse to stop at a checkpoint. Border Patrol can order you to stop for questioning. That's different from the rights you have during an internal ICE stop. Border agents can also check your documents and your immigration status without a warrant in the border region.

If you're crossing the border internationally, carry documents that establish your status. If you're a U.S. citizen, a passport is most secure, though a Real ID license can work. If you're not a citizen, have your immigration documents readily available. The interaction at border crossings is typically straightforward if your documentation is in order. If your status is unclear, crossing an international border is riskier than being in the interior.

International travel is particularly risky if your immigration status is irregular. Many people overseas are unable to return to the U.S. if they've left as undocumented immigrants. Consular processing (getting a visa after the fact) is complicated and not always possible. If you leave, returning legally might not be straightforward. This is worth considering carefully before international travel.

Domestic air travel also involves documentation. TSA requires identification. Airlines verify that passengers are authorized to enter their destination. If you're traveling within the U.S. and your status is questionable, air travel is riskier than driving. ICE agents are sometimes stationed at airports. TSA shares information with other agencies. You're creating more points of contact with systems that can flag immigration issues.

None of this is meant to suggest you can't travel. But travel carries specific risks depending on your status, your location, and your destination. Understanding those risks lets you make informed decisions.

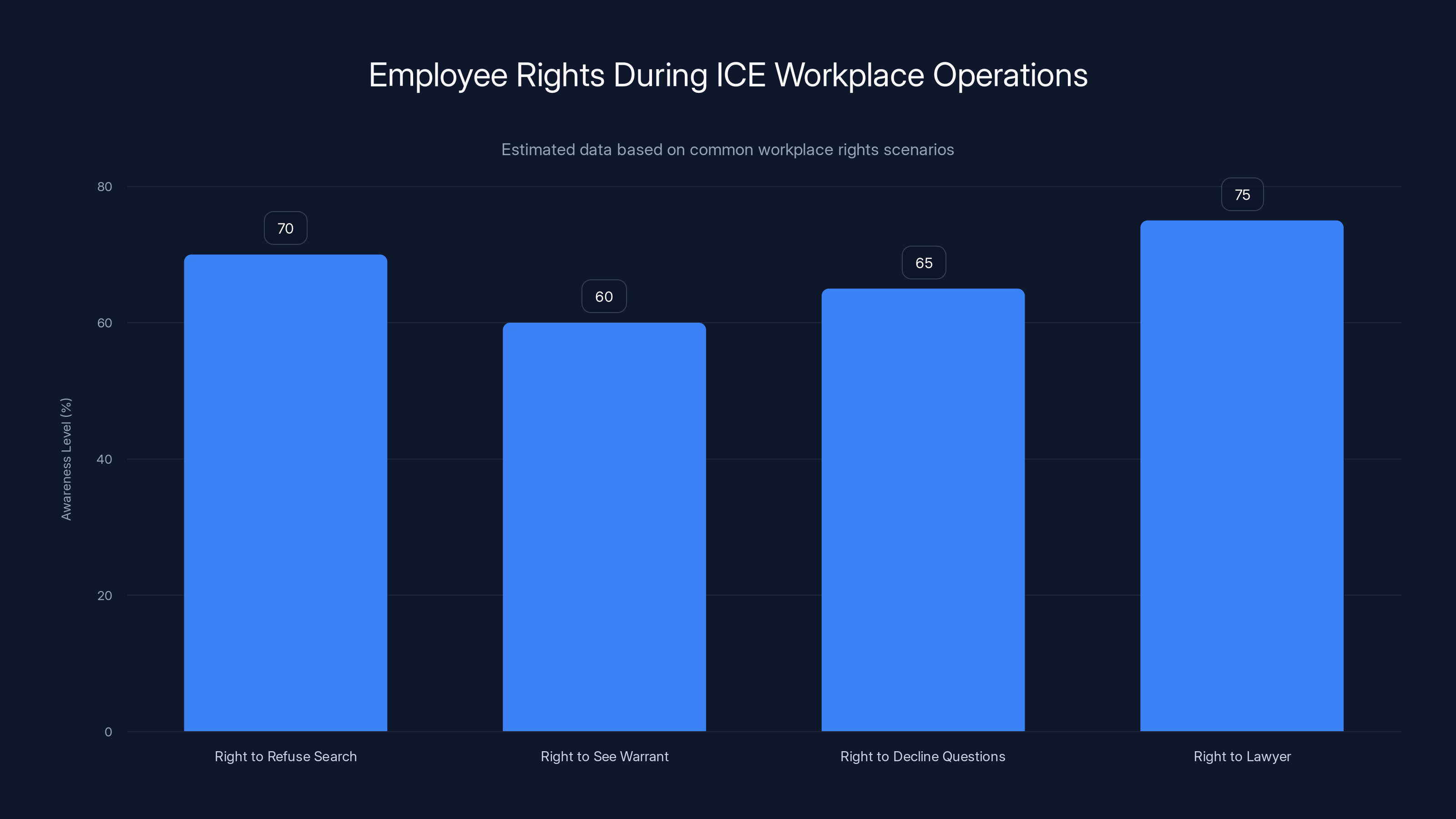

Estimated data shows varying levels of employee awareness of their rights during ICE operations, with the highest awareness for the right to speak to a lawyer.

Workplace Rights and Documentation

ICE conducts workplace operations. Federal agents show up at job sites, particularly in industries with significant immigrant employment. These operations can be chaotic and dangerous, and they raise specific legal and practical considerations.

First, understand your workplace rights. Employers are required to verify employment authorization through an I-9 form when hiring. But employers cannot discriminate in this verification process based on national origin. An employer cannot single out workers who appear foreign for additional verification. Employment authorization verification is required, but discrimination is illegal.

If ICE agents show up at your workplace, you have rights even as an employee. You can refuse consent to search your person or belongings. You can ask to see a judicial warrant. You can decline to answer questions. You can ask to speak to a lawyer. These rights exist on employer property just as they do elsewhere.

Employers are not required to allow ICE agents into the workplace, but many do. Once agents are there, they can conduct interviews with employees. Employees can refuse interviews. Employees can refuse to answer questions. But refusing might make an employee more suspicious or might lead to detention. This creates a practical bind. Cooperating might expose immigration status. Refusing might increase vulnerability to enforcement action.

If you're undocumented and working, understand that your employer technically violated the law by hiring you. The employer can face penalties. But more pressingly, your presence at the workplace is documented. Any workplace-based enforcement action targets you directly. This is a reality of undocumented work.

If ICE operates at your workplace:

- Remain calm and comply with immediate physical commands (for safety)

- Don't run or resist physically

- Ask whether you're free to leave

- Decline consent to search

- Request to speak to a lawyer

- Remember any badge numbers or agent names if possible

- Document what happens (if safe to do so)

- Contact your emergency support network immediately

Co-workers can be witnesses and can document what happens. Employers have insurance and legal obligations. If agents exceed their authority or violate rights, that's actionable. But it's only actionable if it's documented and if legal representation is secured.

Documentation matters. You want your I-9 form, your employment records, your pay stubs. If you're terminated following an immigration enforcement action, that might be illegal retaliation depending on circumstances. Documentation helps establish what happened and what you were owed.

Financial Preparation for Enforcement Scenarios

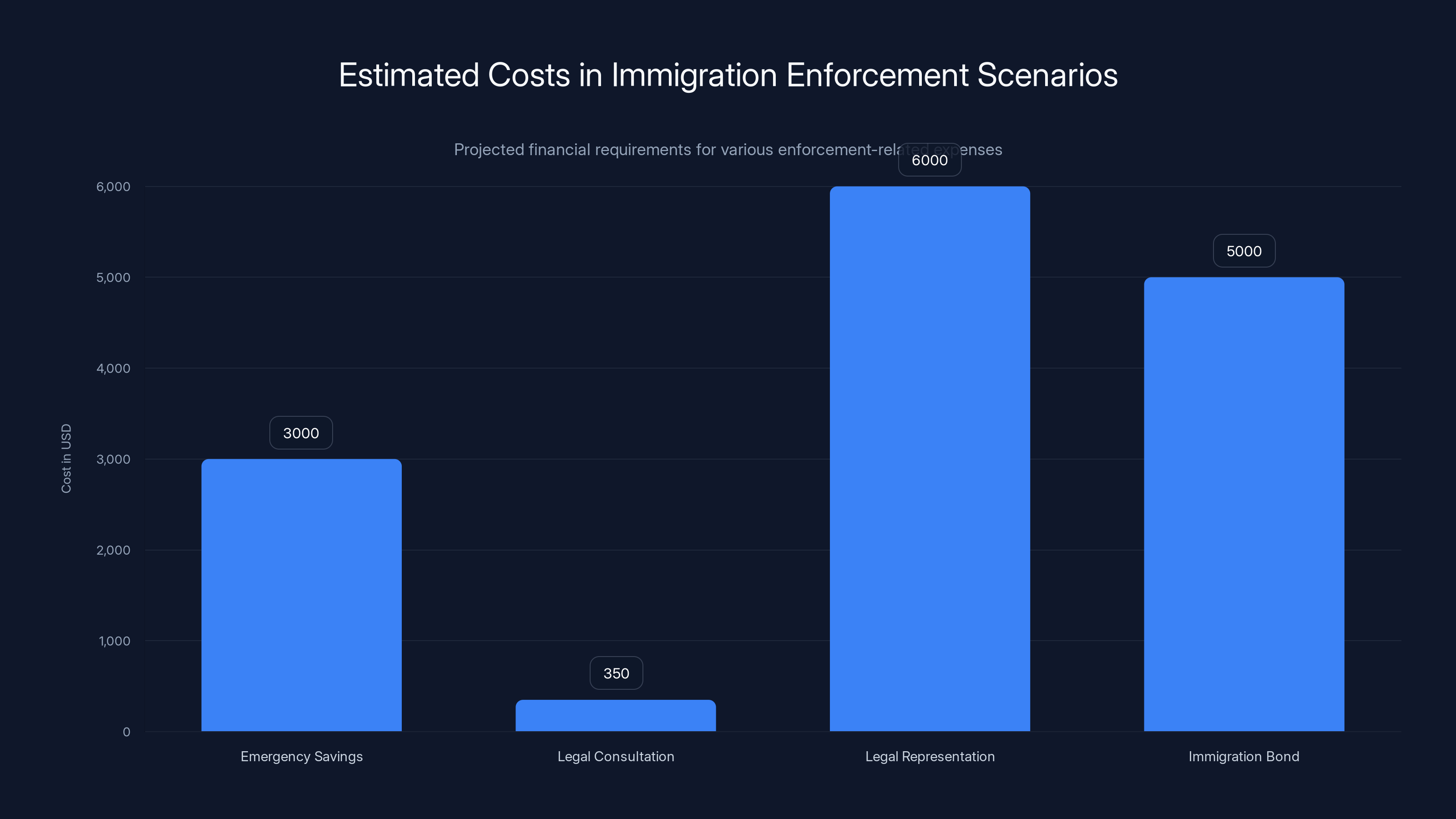

Detention is expensive. Immigration litigation is expensive. Loss of income during enforcement is expensive. Financial preparation can make the difference between manageable disruption and financial devastation.

First, have accessible savings. If you're detained, do you have money available for bail, bond, legal representation, family expenses? Emergency savings of

Second, establish a contingency fund specifically for legal representation. Immigration law is specialized. Good immigration attorneys don't work cheap. They charge hourly rates typically

Third, understand what bonds and bail mean in immigration context. In criminal cases, bail is money to secure release pending trial. In immigration cases, bonds work similarly but are more expensive. An immigration bond might be

Fourth, be aware that detained people are sometimes pressured to sign away assets or rights in exchange for release. This is predatory. Don't sign anything without consulting a lawyer. Any agreement made while detained and vulnerable is likely voidable, but it's better not to make these agreements in the first place.

Fifth, have a power of attorney that allows someone to access your finances if you're detained. Without this, your money is essentially locked up. Bills go unpaid. Debts accumulate. Your credit deteriorates. Someone with power of attorney can manage your money, pay your bills, and keep your financial situation stable during detention.

Sixth, understand that deportation doesn't necessarily mean you lose your U.S. assets. Depending on your situation, property, bank accounts, and other assets might remain accessible. But you need to establish who manages them. Again, power of attorney is critical.

The overall point is that financial preparation changes the practical outcome of enforcement. It doesn't prevent enforcement. But it determines whether enforcement results in temporary disruption or long-term financial destruction.

Estimated data shows a balanced distribution of community support activities, with legal resources slightly prioritized.

Technology and Digital Security

In the current enforcement environment, digital security is part of your overall safety plan. Emails, texts, social media, and digital communications can be accessed by enforcement agents with proper legal process (warrants, subpoenas). But some communications are more vulnerable than others.

First, understand that digital communications can be subpoenaed. If you're using standard email, text, or social media, law enforcement can potentially obtain access through warrants or subpoenas. There's no expectation of complete privacy in these communications. But they still require legal process. Agents can't simply access your email without proper authorization.

Second, consider using encrypted communications for sensitive information. Signal is an encrypted messaging app that's widely used for security-conscious communication. Wire, Telegram, and other apps offer encryption options. These don't make communications impossible to access, but they require more sophisticated legal process and technical effort. For basic communication about sensitive topics, encrypted messaging is more secure than standard text or email.

Third, be aware of information you post publicly. Social media, online forums, publicly accessible information all create a digital record. If you're at immigration risk, this record matters. Posts about your location, your status, your activities—all of this can be used in enforcement contexts. Think carefully about what you're sharing publicly.

Fourth, understand that your phone can be seized and searched during detention. Anything on your phone can be accessed by agents if they have your phone. This means that sensitive communications, photos, documents, or information on your phone becomes accessible if you're detained. For this reason, keep sensitive information off your phone when possible. Use the cloud for documents (with password protection). Use encrypted communication apps for sensitive conversations. Keep your phone relatively clean of sensitive content.

Fifth, have a backup of critical digital information. If your phone is seized, you can still access critical documents, photos, or information from other sources. Cloud backup, external drives, or printed documents all provide redundancy. A detained person needs access to information even if their phone is inaccessible.

Sixth, consider digital security practices that are broadly good hygiene: strong passwords, two-factor authentication for sensitive accounts, regular password updates. These protect against various forms of unauthorized access, including potential abuse of access by law enforcement.

Digital security won't prevent enforcement. But it limits the digital information available to enforcement agents and protects your privacy from casual access.

Working with Legal Representation

Legal representation is critical to navigating immigration enforcement. But understanding how to work with immigration attorneys is important.

First, find an immigration attorney before you need one. This is ideally something done when you're not in crisis. Research immigration attorneys in your area, check their background, understand their experience. If you can't afford private representation, connect with nonprofits that provide free or sliding-scale immigration legal services. Legal aid organizations, law school clinics, and nonprofit immigration organizations all provide representation.

If you locate an attorney before crisis occurs, you can establish a retainer relationship. This typically costs

Second, be honest with your attorney about your situation. Immigration attorneys are bound by confidentiality. What you tell them is privileged communication and cannot be disclosed to enforcement authorities. But attorneys can only help effectively if they have complete information. Don't hide relevant facts from your attorney hoping to protect yourself. The attorney needs to know everything to represent you effectively.

Third, understand the difference between different types of proceedings. If you're detained, you'll be placed in removal proceedings, which is an immigration court process. This is distinct from criminal court proceedings. Immigration court is a civil process, not criminal. The judge works for the Department of Justice (the same agency that prosecutes you), which affects the dynamics. But understanding that this is civil proceedings, not criminal, informs the legal strategy.

Fourth, know that there might be cancellation of removal available to you. If you've been in the U.S. for 10 years, have U.S. citizen or permanent resident family members, and haven't been convicted of certain crimes, you might qualify for cancellation of removal, which allows you to remain in the U.S. even if you're undocumented. This is a powerful legal remedy, but it requires proper legal representation to pursue.

Fifth, understand that immigration law is constantly changing. Policy changes, new regulations, new court decisions—all of these affect immigration proceedings. Your attorney should be current with these changes. Working with an attorney who specializes in immigration is better than working with a generalist attorney who does some immigration work.

Sixth, if you're detained and cannot afford an attorney, you can request a court-appointed attorney if certain conditions are met. But public legal services for immigration matters are extremely limited. Most detained people don't have access to free attorneys. This is a significant gap in the system. If possible, secure private representation before detention.

Community Monitoring and Accountability

Beyond individual protection, community-level responses to ICE operations serve multiple functions. They create documented evidence of what's happening. They deter some forms of misconduct. They provide immediate support to people being affected. And they maintain political visibility of enforcement activity.

Legal observer programs train community members to observe and document police or federal enforcement activities. Observers aren't intervening in the enforcement action. They're present with cameras, notebooks, and legal knowledge. They document badge numbers, agent conduct, statements made, force used, and conditions. This documentation becomes evidence if violations occur.

Community monitoring doesn't prevent all enforcement. But it creates accountability. If agents know that their actions are being observed and documented, some forms of misconduct decrease. And if violations do occur, documented evidence is essential for legal challenges.

Rapid response teams can coordinate immediate support when ICE operations are reported. This might include legal observers, documentation, communication with attorneys, support for families of detained people, and coordination with other community resources. When enforcement happens, rapid response teams can activate immediately, providing coordinated community support rather than isolated individual responses.

Direct action and protest can increase the political visibility of enforcement. Public opposition to ICE operations puts political pressure on elected officials, shapes public opinion, and maintains visibility of these issues. Protest doesn't stop individual enforcement actions, but sustained public opposition can shape broader policy.

Community organizing creates infrastructure for long-term response to enforcement. This might include community meetings, education about rights, network building, and coordination of resources. When individual enforcement actions occur, they happen within the context of this broader community organizing, which provides structure and support.

Information sharing about enforcement activity is important. If ICE operations are reported in a neighborhood, that information should spread quickly through community networks. People know to be cautious, to gather documentation, to prepare for possible operations. This doesn't prevent enforcement, but it mobilizes response.

All of this requires volunteers, resources, and sustained commitment. It's not easy work. But it fundamentally changes the context in which enforcement happens.

State and Local Government Response

Local governments have varying levels of cooperation with federal ICE operations. Some jurisdictions are "sanctuary cities" that limit cooperation with federal immigration enforcement. Other jurisdictions actively cooperate. Understanding your local government's position matters.

Some states have passed laws limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities. These laws typically prevent local police from collaborating with ICE, prevent jails from holding people for ICE beyond their normal release date, and limit information sharing with federal immigration agencies. These protections don't prevent ICE from operating independently, but they limit the support ICE receives from local law enforcement infrastructure.

Local police unions, police chiefs, and sheriffs have sometimes opposed ICE operations in their jurisdictions. This isn't necessarily from humanitarian concern. It's often from practical concerns about community relations, resource diversion, and the complications of federal agents operating in their jurisdiction. But when local law enforcement expresses opposition to ICE operations, it can create practical limitations on those operations.

Some local jurisdictions have passed laws protecting day laborers, limiting immigration enforcement in certain locations, or requiring notification to legal organizations when federal enforcement happens. These local protections don't prevent federal enforcement, but they can create procedural requirements that protect people.

Organized effort to change local government policy can reduce local cooperation with ICE. This might include advocating for sanctuary policies, advocating for restrictions on cooperation, advocating for legal resources, or advocating for local investigation of federal violations.

Local government response is not guaranteed protection. But it shapes the practical context in which enforcement happens and can meaningfully improve outcomes.

Emotional and Psychological Support

Enforcement operations create trauma. Fear of detention, actual detention, loss of loved ones, separation from family, threat of deportation—these create psychological harm that extends beyond the immediate enforcement action.

Access to mental health support is important. Therapists familiar with trauma, immigration stress, and community violence can provide support. Many community organizations offer mental health services specifically for people affected by immigration enforcement. These services are often free or sliding scale.

Peer support is also important. Community gatherings, support groups, family networks—these provide emotional connection and reduce isolation. Knowing that others are experiencing similar fears and that there's community support available helps with psychological resilience.

For children, enforcement operations are particularly traumatic. Children might witness parents being detained. Children might be separated from parents. Children might experience fear of future enforcement. Schools and child care providers should be prepared to support children experiencing immigration-related trauma. Parents should ensure that schools understand what might happen and how to support affected children.

After enforcement actions, trauma continues. People who are detained experience ongoing effects. People whose family members are deported experience grief and loss. Communities experiencing repeated enforcement operations experience collective trauma. Mental health support, community processing, and access to counseling are important for healing.

Future Preparation and Long-Term Strategies

Immediate safety planning addresses the current moment. But longer-term strategies might include considering immigration options that might be available to you, exploring permanent solutions to your status, or making decisions about where you want to live.

Some people might qualify for legal status that they haven't pursued. Asylum is available to people persecuted based on protected characteristics. Family-based immigration allows sponsorship by relatives. Employment-based immigration allows sponsorship by employers. Not everyone qualifies for these options, but some people do. Working with an immigration attorney to explore these options might reveal paths to legal status that you weren't aware of.

Some people decide that the risk of enforcement has become intolerable and consider relocation. This might mean moving to a different state (though enforcement is nationwide), moving to a different country if you have options, or making other significant life changes. These are major decisions that should be made thoughtfully with support and legal counsel.

Some people decide to fight for their right to remain in the U.S. and actively participate in advocacy, organizing, and legal challenges to enforcement. This is a conscious choice to engage with resistance, with understanding of the risks involved.

None of these choices is objectively correct. But having thought them through, having professional counsel, and having made conscious decisions about your path forward is protective. Living in constant fear and reaction is more destabilizing than making intentional choices about your future, even if those choices involve significant risk.

Navigating Misinformation and Scams

During enforcement escalation, misinformation spreads. Some of it is well-intentioned but inaccurate. Some of it is predatory scams targeting vulnerable people.

You might hear claims that certain documents protect you from deportation. Some of these documents have value. Some are worthless. Depending on the actual document and your specific situation, a piece of paper might actually protect you, or it might be a scam selling you false hope.

You might hear claims about special rights available to people in certain circumstances. Some of these claims are accurate. Some are fabrications. Immigration law is complex, and specialized knowledge is required to separate accurate claims from misinformation.

You might be approached with offers to help you "disappear" or evade enforcement for money. These range from legitimate relocation assistance to outright scams where your money is taken and no services are provided.

You might hear claims about immigration processing programs or pathways that aren't actually available. Bad actors exploit people's desperation to maintain hope that solutions exist.

Protection from these scams comes from:

- Using established legal organizations and attorneys rather than private operators

- Verifying claims through multiple sources

- Being skeptical of anyone promising guaranteed protection from deportation

- Understanding that legitimate legal options exist but aren't secret

- Consulting with real attorneys before giving money to anyone

Scams specifically targeting vulnerable people during enforcement escalation are common. Your safeguard is knowledge and caution.

FAQ

What should I do if ICE agents arrive at my home?

If agents are at your door, stay calm. Ask to see identification and verify they're actually ICE. Tell them "I do not consent to entry. You need a judicial warrant signed by a judge." Do not open the door. Do not answer questions. Ask to speak to a lawyer. If they force entry, that's a potential rights violation. Once in a safer situation, contact your attorney and document everything that happened.

What's the difference between an administrative warrant and a judicial warrant?

An administrative warrant is a civil document that ICE agents use for immigration enforcement. It does not authorize entry into someone's home without permission. A judicial warrant is signed by a judge and gives law enforcement authority to enter homes and conduct searches. Judicial warrants are much more restrictive for ICE to obtain, which is why immigration agents typically carry administrative warrants instead. This legal distinction is crucial to your rights.

Can I record ICE agents if they stop me?

Yes, in most states you can record interactions with law enforcement and federal agents in public spaces. Recording law varies by state (some require all-party consent for recording conversations, but this usually applies to recorded phone calls, not public interactions). Recording an interaction happening in public where you have a right to be is generally legal and protected. Recording creates important documentation of what happened.

What are my rights if I'm detained by ICE?

You have the right to remain silent beyond providing your name. You have the right to speak to a lawyer. You cannot be held indefinitely without legal process. Technically, ICE should have 48 hours to determine whether to place you in formal removal proceedings. You have the right to a hearing before a judge before being deported. These rights are legal protections, but they're only meaningful if you assert them and if you have legal representation.

How much money should I have set aside for an ICE emergency?

This depends on your specific situation and risk level. Ideally, you'd have

What should I do if someone I know is detained by ICE?

First, find out where they're being held. This information is often available through ICE facility locators or by contacting local immigration attorneys. Second, contact an immigration attorney immediately. Third, gather emergency family support and let their dependents know they're okay if that's possible. Fourth, ensure bills are paid and childcare is arranged. Fifth, help coordinate legal representation and document the circumstances of detention. Finally, connect them with support services if they're released.

Can I be deported if I'm a U.S. citizen?

No, U.S. citizens cannot be deported. But ICE agents have detained and attempted to deport U.S. citizens in documented cases due to errors or misidentification. If you're a U.S. citizen, you should carry proof of citizenship if possible (passport, birth certificate, or naturalization certificate). If detained, you should clearly assert your citizenship status and demand to speak to an attorney who can prove your status.

Are there immigration options available to people with irregular status?

Depending on your specific circumstances, there might be. Asylum is available to people persecuted based on protected characteristics. Cancellation of removal is available to people who've been in the U.S. for 10 years with family ties and no serious criminal convictions. Some employers sponsor employees for work visas. Some family members can sponsor relatives for immigration. These options aren't available to everyone, but working with an immigration attorney to explore them is worthwhile.

How do I find a trustworthy immigration attorney?

Look for immigration attorneys with demonstrated experience, check bar association verification, ask for references, and verify they're actually licensed to practice law. Immigration nonprofits can recommend attorneys. Law school clinics can provide services. Avoid anyone who guarantees specific outcomes or charges excessive upfront fees. Legitimate attorneys will discuss your case, explain options, and be honest about what's possible.

What happens to my employment if I'm detained by ICE?

If you're detained, you'll miss work. This can result in termination, though employers cannot legally fire you specifically for being detained by immigration enforcement (this would be illegal retaliation in some circumstances). Realistically, your employer might not hold your job during extended detention. Having emergency funds to cover lost income or having a power of attorney who can communicate with your employer are protective measures.

Conclusion

There's no single right way to navigate the current immigration enforcement environment. The landscape is chaotic. Agents behave unpredictably. Constitutional protections exist on paper but aren't always enforced. Communities are mobilizing in various ways to respond. The reality is terrifying for millions of people, and that fear is completely justified.

But this moment also requires clear thinking about actual risk, actual options, and actual steps that reduce vulnerability and provide support.

You have legal rights. Knowing what they are and how to assert them is foundational. Constitutional protections around entry to homes, rights to remain silent, and rights to counsel are real. They've been tested in court. But asserting these rights in interactions with armed federal agents requires knowledge, nerve, and often legal representation.

Beyond individual legal rights, there's the practical work of building community infrastructure that supports people affected by enforcement. Emergency contact networks, trusted support people, legal resources, documented plans, and collective response create a fundamentally different context than isolated individual responses.

There's also the work of understanding your own specific situation. Your risk level depends on immigration status, citizenship, location, and visibility. Your resources depend on finances, legal knowledge, community connections, and support systems. Your options depend on your specific circumstances and what you're willing to do.

None of this is meant to suggest that individual safety planning prevents the political problems with immigration enforcement. The broader issues are policy failures, inadequate oversight, constitutional violations by agencies designed to enforce immigration law, and political choices to prioritize enforcement over humane immigration policy. These are problems that require political solutions, not just individual protection.

But while political solutions are being fought for, people are still being detained, separated from families, and deported. Protecting people in that context requires the practical, tactical, and community-level work described here.

If you're directly at risk, you need a plan. If you're supporting people at risk, you need infrastructure. If you're an observer of this situation, you need understanding of what's happening and what options exist for response.

The moment is serious. The risks are real. But so are the options for protection, support, and response. Moving from fear into action, from isolation into community, and from powerlessness into strategic response is possible. It requires knowledge, preparation, and sustained commitment. But it's possible.

Start where you are. Know your rights. Build your emergency plan. Connect with your community. Support people affected by enforcement. Participate in advocacy for policy change. Do what you can with what you have. This moment requires that.

Key Takeaways

- ICE agents generally need judicial warrants to enter homes, not administrative warrants, but enforcement has become increasingly chaotic and violations are common

- Personal safety planning requires identifying risk level, building emergency contacts, establishing power of attorney, and preparing financial resources for legal representation

- Community-level infrastructure including legal observers, rapid response teams, and neighborhood networks creates accountability and coordinated support during enforcement

- Recording federal enforcement interactions is generally legal and creates essential documentation for accountability when violations occur

- Understanding the difference between civil immigration violations (not criminal) and the increasingly militarized enforcement approach helps assess actual risk and response strategies

Related Articles

- Minnesota Sues to Stop ICE 'Invasion': Legal Battle Over Operation Metro Surge [2025]

- Right-Wing Influencers Minneapolis ICE: Social Media Propaganda [2025]

- Trump's Mass Deportation Machine: How Federal Law Enforcement Replaced Militias [2025]

- Apple's ICEBlock Ban: Why Tech Companies Must Defend Civic Accountability [2025]

- Spotify Ends ICE Recruitment Ads: What Changed & Why [2025]

- Surveillance Goes Both Ways: How Citizens Are Recording Police [2025]

![ICE Enforcement Safety Guide: Know Your Rights [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-enforcement-safety-guide-know-your-rights-2025/image-1-1768302446295.jpg)