How DHS Keeps Failing to Unmask Anonymous ICE Critics Online

Last month, the Department of Homeland Security backed down from a fight it probably shouldn't have picked in the first place. After demanding that Meta (Instagram and Facebook's parent company) hand over the personal information of anonymous accounts monitoring Immigration and Customs Enforcement activity, DHS quietly withdrew its summonses. No explanation. No public statement. Just gone, as reported by Ars Technica.

The moment matters more than you might think. It reveals something fundamental about digital rights in 2025: even the most powerful government agencies can't simply unmask critics whenever they feel threatened. But it also shows that the fight isn't over—it's just shifting.

What happened in Pennsylvania with John Doe and his community watch group isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a larger pattern where DHS has repeatedly tried, and repeatedly failed, to identify people posting about ICE activities online. Each failure suggests the same thing: the First Amendment still has teeth when it comes to anonymous speech, but only if people know how to defend it, as highlighted by Freedom Forum.

This article breaks down exactly what happened, why it matters, how anonymous activists are winning these fights, and what happens next. Because if you care about digital privacy, government overreach, or the right to criticize powerful institutions without fear of retaliation, you need to understand this story.

TL; DR

- DHS withdrew summonses demanding subscriber data from Instagram/Facebook accounts monitoring ICE, signaling First Amendment protections for anonymous critics are holding strong, as noted by Politico.

- The playbook works: Community watch groups successfully quashed DHS summonses by filing motions highlighting First Amendment violations and innocuous content.

- Meta's role matters: The platform initially sought clarification, then notified account holders—giving them a legal window to fight back before information was shared, according to Jakarta Globe.

- Pattern of failures: This is at least the third time DHS tried and failed to unmask ICE critics, suggesting the agency may be testing legal boundaries.

- Political pressure mounting: ICE criticism is at historic highs, with public approval tanking and even House Democrats voting to defund the agency, as reported by Politico.

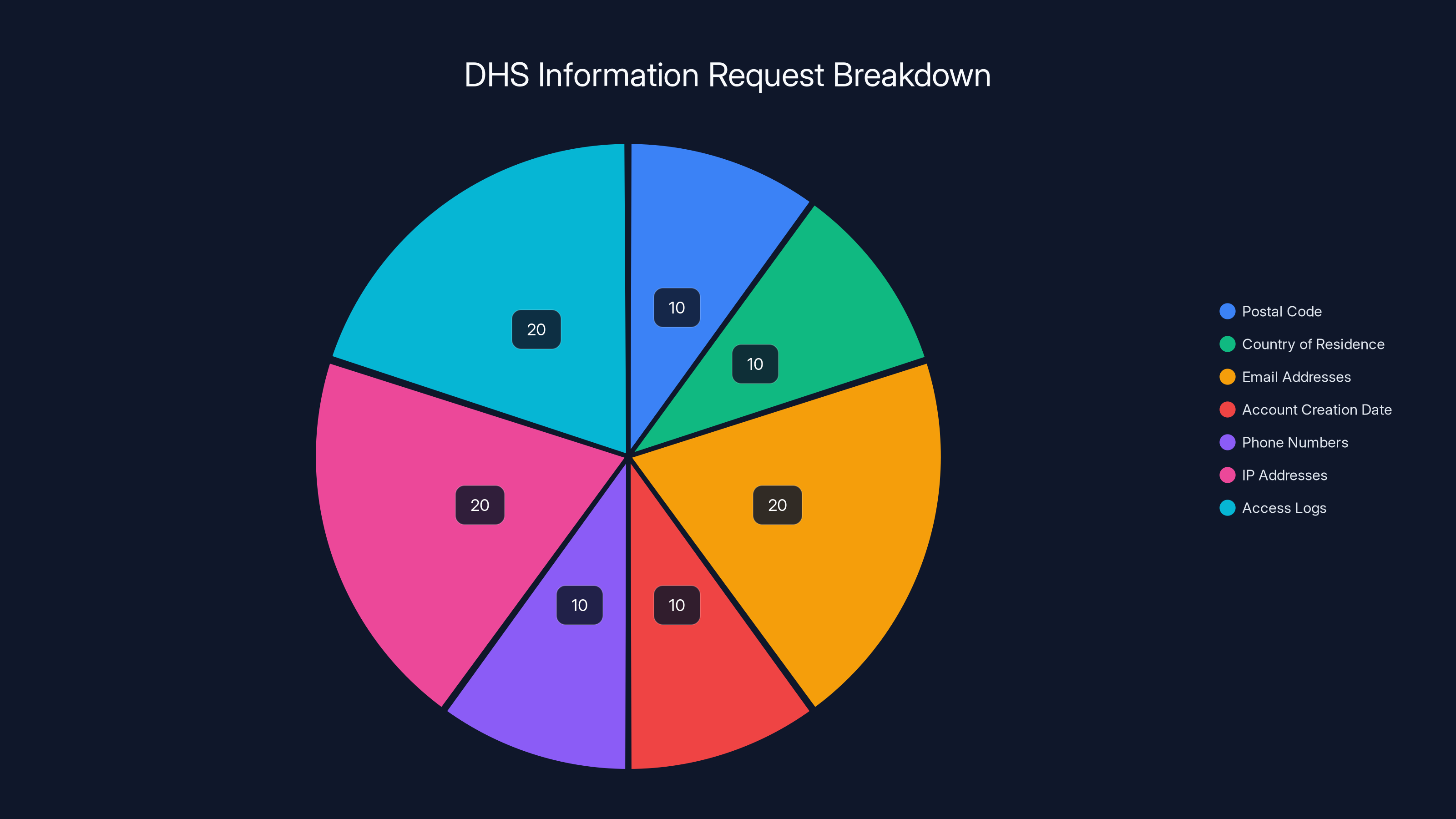

DHS's request for information from Meta was comprehensive, with a significant focus on email addresses and IP access logs. Estimated data.

The Standoff: DHS vs. Anonymous ICE Monitors

In early 2026, John Doe—a pseudonym used in court filings to protect his identity—ran an Instagram account as part of "Mont Co Community Watch," a group documenting ICE activities in Pennsylvania. The group's content was straightforward: they posted information about immigrant rights, due process, fundraising for legal defense, and notices about vigils.

Nothing violent. Nothing threatening. Just community organizing.

Then DHS showed up with a summons, as detailed by Fox 10 Phoenix.

The agency demanded that Meta turn over extensive subscriber information. They wanted Doe's postal code, country of residence, all email addresses on file, account creation date, registered phone numbers, IP address at signup, and logs of every IP address used to access the account along with timestamps. This wasn't a request for post metadata or a narrow inquiry. It was a comprehensive dossier designed to unmask him completely.

DHS's justification? The agency claimed that posting "pictures and videos of agents' faces, license plates, and weapons" constituted threats to "assault, kidnap, or murder" federal officers. They argued the account holders were "impeding the performance of [ICE agents'] duties" by publicly documenting their activities, as reported by BBC.

This is where things get interesting.

The Government's Legal Theory

DHS didn't cite standard subpoena law. Instead, they invoked a statute tied to the "importation/exportation of merchandise"—a customs statute that allows agents to subpoena information about goods crossing borders. It's an oddly specific legal hook, and it suggests DHS was testing whether they could stretch the law's boundaries to claim "unlimited subpoena authority" over online critics.

The strategy was bold. If DHS could establish that posting footage of ICE agents constitutes an impediment to their duties under this statute, the implications would be enormous. DHS could potentially demand subscriber information from anyone posting about ICE, anywhere, anytime. The precedent would gut anonymous speech protections.

DHS Secretary Kristi Noem had already claimed publicly that identifying ICE agents is a crime. But this claim has a problem: ICE employees routinely post LinkedIn profiles. They attend public events. They don't hide. The framing that posting public information about public servants somehow constitutes criminal threatening doesn't hold up legally, as discussed by Inkl.

Why John Doe Fought Back

John Doe didn't accept the summons quietly. Instead, he sued to block it. With representation from the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania (ACLU-PA), Doe argued that the summons violated his First Amendment right to anonymous speech. He also argued that the government hadn't met the legal standard for unmasking, which typically requires demonstrating that the speaker posed a genuine, credible threat or engaged in illegal activity.

Doe's attorney, Ariel Shapell from ACLU-PA, had a straightforward argument: the posts were "innocuous." Showing the court the actual content of Mont Co Community Watch's Instagram feed, Shapell demonstrated that nothing in their posting history suggested violence or criminality. The account existed to inform and organize—core First Amendment-protected activities, as noted by KSTP News.

This was crucial. By forcing DHS to look at the actual evidence (or lack thereof), Doe's legal team made it harder for the government to maintain the fiction that the account posed a threat to federal agents.

Technical measures are estimated to be the most effective for activist protection, followed by organizational and legal preparations. Estimated data.

How Community Watch Groups Won: The Playbook

Doe's victory wasn't unique. In fact, community watch groups had already developed a tested strategy for surviving DHS summonses. And importantly, other groups had already won using similar tactics.

Before DHS came after Doe, the agency had requested subscriber information about six Instagram community watch groups monitoring ICE activities in Los Angeles and other locations. Those groups also filed motions to quash the summonses. And DHS withdrew those requests too, as highlighted by Politico.

The pattern is clear: DHS tries, groups fight back, DHS backs down.

Step 1: Meta Notifies You

When DHS served Meta with a summons seeking subscriber information, the platform didn't immediately comply. Instead, Meta took the time to notify account holders that their information was being requested. This notification is critical—it gives people a legal window to fight back before their data is handed over, as detailed by Jakarta Globe.

Meta's role here shouldn't be understated. The company isn't required by law to notify users about government requests (though some companies do this voluntarily). But the notification period is essential. Without it, DHS could simply demand information and take possession of it before anyone knew to file a motion.

Step 2: File a Motion to Quash

Once notified, account holders must act fast. The next step is filing a formal "motion to quash" the summons—a legal document arguing that the government doesn't have the right to compel the information. This motion must articulate why the summons violates the First Amendment, why the government hasn't met the legal threshold for unmasking anonymous speakers, or both.

In Doe's case, the motion focused on First Amendment protections. The legal standard for unmasking an anonymous speaker was established in cases like Doe v. Cahill and requires showing that the information is necessary to the plaintiff's case and that the plaintiff has exhausted other methods of identifying the defendant. But here, DHS wasn't a civil plaintiff trying to identify a defendant in a lawsuit. DHS was a government agency using an indirect statute (customs law) to unmask political critics.

That's a completely different legal problem.

Step 3: Present Actual Evidence

Here's where Doe's team did something crucial: they didn't just argue law in the abstract. They presented the actual content to the court. They showed that Mont Co Community Watch's posts were about community organizing, not threats. They showed immigrant rights information. They showed vigil notices. They showed fundraising efforts for legal defense.

Judges care about facts. When you put actual evidence in front of a judge and it clearly doesn't match the government's characterization, it becomes hard to justify the summons.

Step 4: Challenge the Legal Theory

Doe's legal team also challenged the specific statute DHS was using. A customs statute designed to govern the importation and exportation of merchandise isn't reasonably read to grant "unlimited subpoena authority" over online speech. That's overreach, and judges tend to notice when government agencies try to misuse statutes in ways Congress clearly didn't intend, as discussed by WHYY.

When you combine a weak legal theory with evidence that contradicts the agency's claims about threats, you get a motion to quash that's very hard to defend.

Why DHS Backed Down (And What It Means)

On January 16, DHS withdrew its summonses. The court filing confirming this withdrawal doesn't explain why. But the implications are clear: DHS looked at what it would face in a legal fight and decided it wasn't worth it, as reported by Ars Technica.

There are a few possibilities. First, it's possible DHS concluded that it simply didn't have evidence to support its claim that Doe's posts constituted threats or impediments to federal duties. Looking at actual Instagram content about immigrant rights and vigils is different from hearing an agency's characterization of that content.

Second, it's possible DHS recognized that the legal theory—using a customs statute to unmask online political critics—is fundamentally weak. A judge could easily rule that this statute was never meant to be used this way, setting a bad precedent for the agency.

Third, and this matters, it's possible DHS was also concerned about the political optics. Trying to unmask anonymous critics during a period of intense ICE criticism, when even House Democrats were voting to defund the agency, wouldn't play well. Losing the case publicly would be worse, as noted by Axios.

The Broader Pattern

This isn't the first time DHS has tried and failed. The Los Angeles groups, the Pennsylvania groups—these aren't unique stories. What we're seeing is a pattern where DHS tests legal boundaries, meets resistance, and backs down.

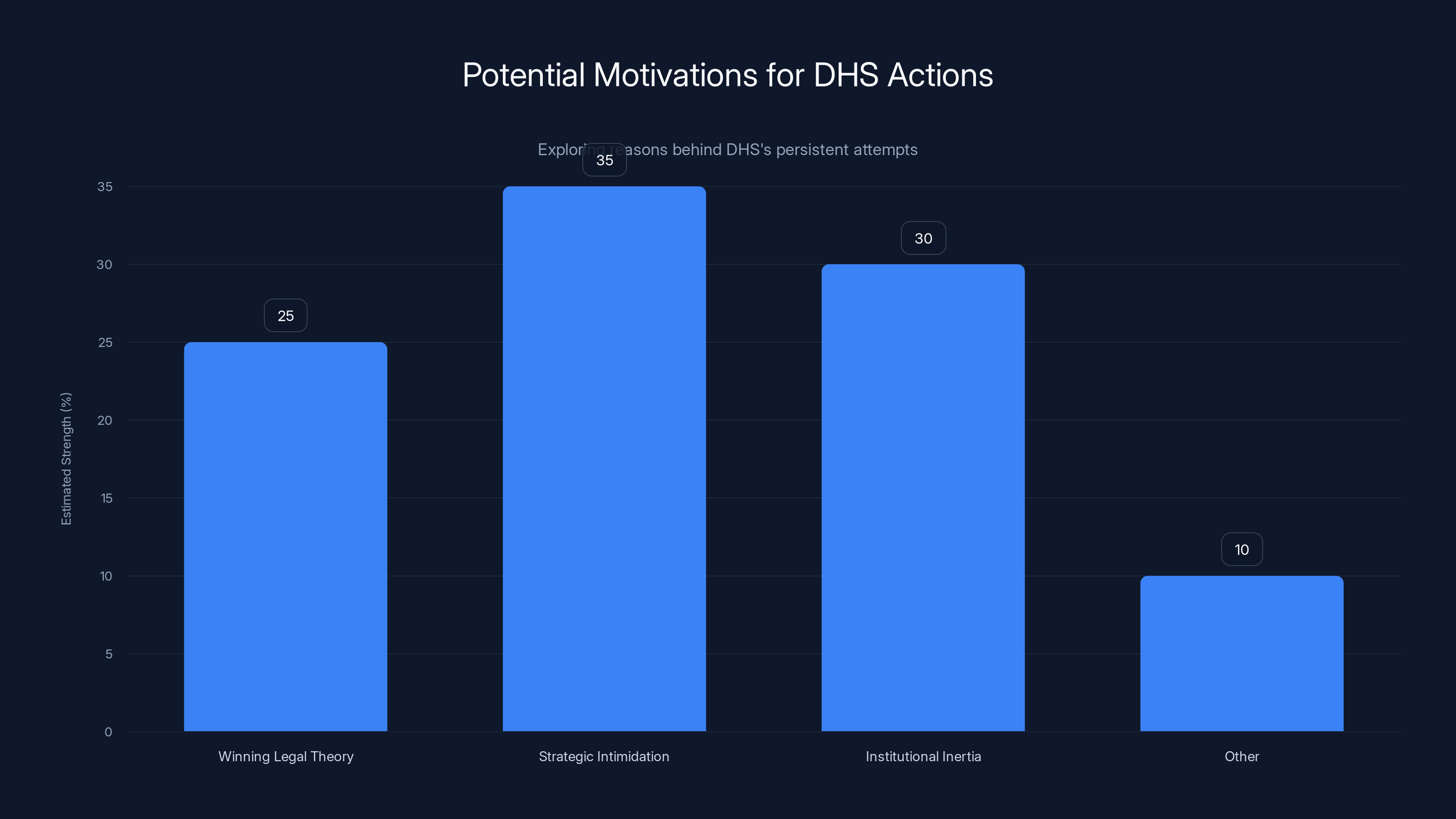

This could suggest a few things about DHS's strategy. Either the agency is genuinely trying to find a legal hook that works (and hasn't found it yet), or they're engaging in strategic litigation to intimidate and test waters without expecting to win. Both are problematic, but they have different implications.

If DHS is genuinely searching for a legal theory that works, then every time they back down, it's a small victory for First Amendment protections. But it also means they'll keep trying.

If they're engaging in intimidation—filing summonses they expect to lose just to frighten critics—then the legal victories matter less. The intimidation already worked.

The chart estimates potential motivations driving DHS's actions, with strategic intimidation and institutional inertia being significant factors. Estimated data.

The First Amendment and Anonymous Speech Online

Why does any of this matter legally? To understand that, you need to know how courts handle anonymous speech.

The First Amendment doesn't explicitly protect anonymity. But decades of case law have established that anonymous speech is core First Amendment activity, especially when it comes to political criticism, activism, and organizing.

In NAACP v. Alabama, the Supreme Court recognized that forcing groups to disclose their membership rolls violated the First Amendment. The Court understood that requiring people to publicly identify as members of controversial organizations could chill speech and association. That logic extends to anonymous online speech, as discussed by Freedom Forum.

When someone criticizes the government anonymously, they're engaging in political speech at the highest level of First Amendment protection. The government can't simply demand their identity because it dislikes what they're saying or finds their criticism inconvenient.

The Legal Standard

But there is a legal standard for unmasking anonymous speakers. It's not absolute protection—it's qualified protection. Courts generally require that before an anonymous speaker is unmasked, the party seeking to unmask them must show:

- Necessity: The information is actually necessary to their case (not just helpful or convenient).

- Exhaustion of alternatives: They've tried other ways to identify the speaker or get the information they need.

- Balancing: The interest in unmasking is weighed against the First Amendment interest in anonymity.

- Specificity: The information sought is specific and limited, not a fishing expedition.

DHS's summons failed on nearly every count. The government's interest in unmasking was based on a weak theory that posting footage of ICE agents somehow impedes their duties. The actual content didn't support claims of threats. And the information sought was extremely broad—essentially a complete dossier.

Anonymous Speech and Government Critics

There's another layer to this. Courts are particularly protective of anonymous speech when the speaker is criticizing the government. The government has significant power. If you're a private citizen or activist criticizing a powerful agency like ICE, anonymity can be essential.

Without anonymity, you might face retaliation. You might lose your job. You might be targeted by the government in other ways. These aren't theoretical concerns—they're real consequences that anonymous speech prevents.

When DHS demands subscriber information from ICE critics, it's not just asking for data. It's threatening the ability of people to criticize the government safely. And courts understand that, as highlighted by Freedom Forum.

ICE Criticism: Why Now? Why So Intense?

To understand why DHS was so motivated to unmask these accounts, you have to understand the political environment around ICE in early 2026.

ICE criticism is at historic levels. Public approval is tanking. Even House Democrats recently voted to defund the agency—a "remarkable shift," as political analysts noted, from just one year earlier when dozens of them voted to expand Trump administration immigration enforcement, according to Politico.

Why the shift? Multiple high-profile incidents.

Deaths and Shootings

Renee Good's killing was a catalyst. That incident, combined with eight other ICE shootings since September alone, energized critics who argue that ICE uses excessive force and operates with insufficient oversight. Footage of these incidents circulated widely on social media, with community watch groups documenting and sharing the videos, as reported by BBC.

Videoography and documentation matter. When ICE agents' actions are on camera, they can't be disputed or minimized in official reports. Community watch groups understood this power.

Immigration Enforcement Tactics

Beyond shootings, ICE's tactics themselves became controversial. Shocking footage emerged of ICE agents using a five-year-old boy as bait to trap family members. Another incident showed agents removing a US citizen from his home in his underwear during what they claimed was a standard warrant enforcement, as detailed by WHYY.

Then came the whistleblower reports. An internal memo revealed that ICE agents were conducting warrantless searches and entering homes without judicial warrants. This became standard practice—not an exception.

Each incident fed the broader narrative: ICE operates without sufficient oversight, uses excessive tactics, and operates in ways that violate civil liberties.

Political Momentum

The House vote to defund ICE didn't pass (Republicans control the House), but the vote itself was significant. It signaled that political momentum was shifting against the agency. And as public approval tanked, DHS faced increasing pressure.

Community watch groups documenting ICE activities were essentially amplifying this pressure. By sharing footage and information on social media, they were building a public record of ICE's conduct. This record informed political debate and gave critics concrete examples to cite.

From DHS's perspective, unmasking these accounts might seem like a way to stem the criticism by identifying and potentially intimidating the people running them.

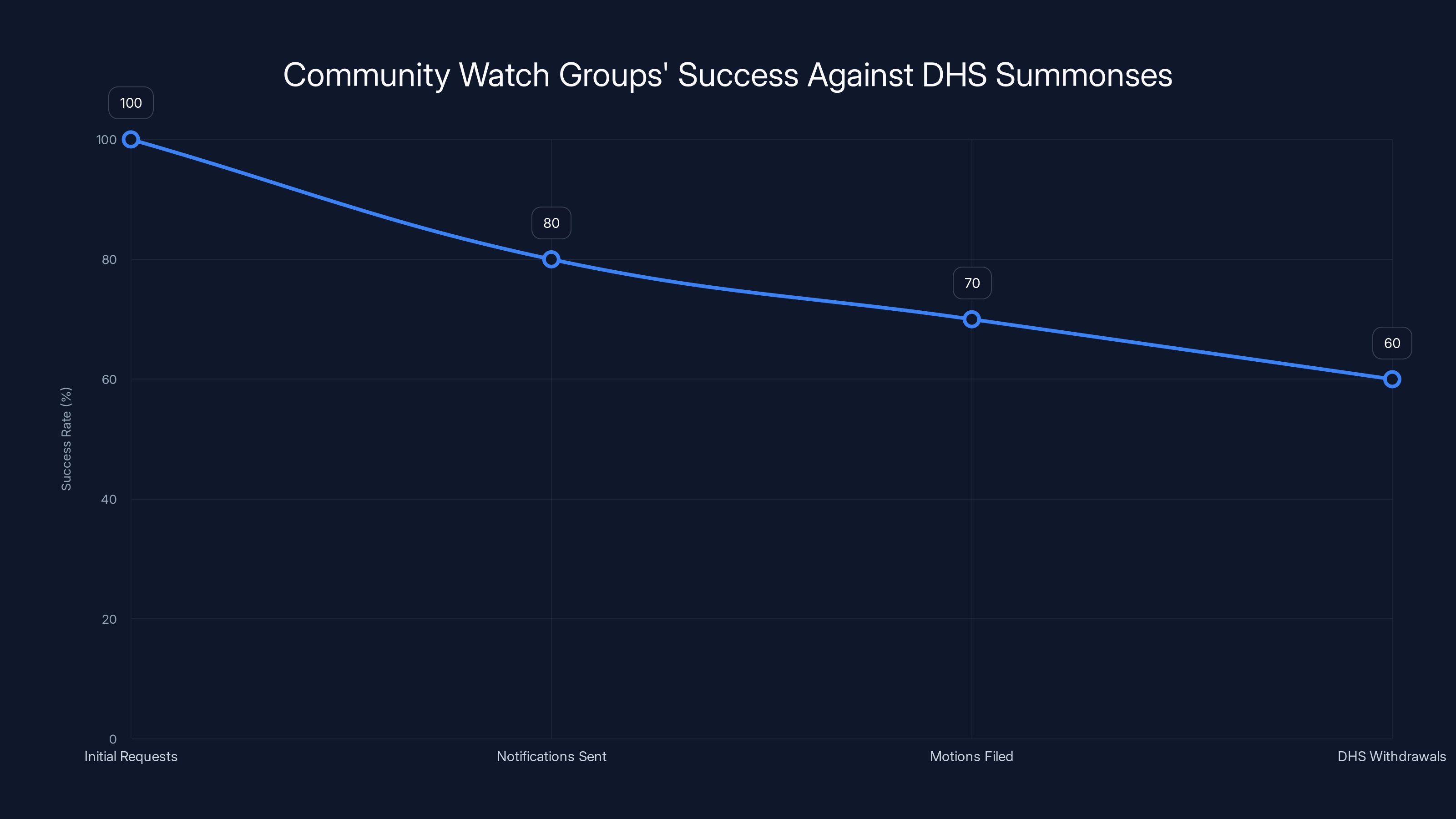

Community watch groups have a high success rate in quashing DHS summonses, with an estimated 60% of requests being withdrawn after motions are filed. Estimated data.

What Meta Did (And Didn't Do)

Meta's role in this story is more complex than it might initially appear. The company didn't simply hand over information. But it also didn't take an aggressive stance against the government demand.

The Notification Process

When DHS served the summonses, Meta didn't immediately comply. Instead, the company sought clarification from DHS about the requests. This is a standard practice—companies often ask the government to narrow overly broad requests or clarify legal grounds.

Then Meta notified the account holders. This notification was the critical window that allowed John Doe and others to file motions to quash before information was shared, as noted by Jakarta Globe.

The Unanswered Question

But here's what remains unclear: would Meta have complied if the account holders hadn't fought back? If Doe hadn't filed a motion to quash, would Meta simply have handed over all the requested data?

Under the law, Meta isn't required to fight government requests if they meet legal standards. If a judge ordered the information released, Meta would likely comply. But Meta also isn't required to facilitate government surveillance of activists.

Meta's notification procedure suggests the company recognizes the importance of giving people a chance to defend their legal rights. But the company's ultimate willingness to comply with court orders—and the absence of any public statement from Meta opposing the requests—leaves a gray area.

What if DHS had gotten a court order? Would Meta have challenged it? Would they have demanded privacy protections? We don't know. And that's concerning.

The Broader Implications: What Happens Next?

Doe's victory is important, but it's also narrow. DHS backed down, but nothing in this case actually establishes legal precedent preventing future attempts. No judge ruled that DHS's theory was unconstitutional. No court decided that the statute couldn't be used this way.

Instead, DHS simply withdrew. And that means the agency could try again, as discussed by Politico.

The Risk of Renewed Attempts

With every failed attempt, DHS gains information. They learn what arguments courts will accept and which ones won't. They learn what account holders are likely to fight and what tactics might work better.

Future summonses could be more carefully crafted. DHS might narrow the information requested. They might develop a more sophisticated legal theory. They might focus on groups with less legal support or fewer resources to fight back.

The playbook that worked for Doe and the Los Angeles groups—file a motion to quash, present evidence that contradicts the government's characterization, challenge the legal theory—might not work as well if DHS gets smarter about future attempts.

The Importance of Legal Support

John Doe had representation from the ACLU. That mattered. Most people don't have access to civil rights lawyers who will fight government summonses. Most activist groups don't have the resources to mount a legal defense.

If DHS starts targeting smaller groups without legal support, or groups less likely to know how to fight back, the outcomes might be different.

The Platform Question

Meta's role also raises questions. What happens if Meta decides to cooperate more readily with government requests? What if Facebook or Instagram change their notification policies? What if platforms decide that government requests are too onerous to fight and start complying more readily?

Much of the success in these cases depends on Meta giving account holders time to fight. If that changes, the entire playbook breaks down.

Estimated data shows that the DHS's summons failed to meet the required legal standards for unmasking anonymous speakers, with low compliance across all criteria.

How Activists Can Protect Themselves

For community organizers and activists considering anonymous accounts to document government agencies, there are practical steps that improve protection.

Technical Measures

First, use a VPN when creating and accessing accounts. This prevents your real IP address from being recorded in platform logs. Second, use a dedicated email address created specifically for the account, not one linked to your real identity.

Third, be careful about the device you use. Don't access the account from a device associated with your real identity. Consider using a separate device or a public computer.

Fourth, avoid location tagging or any metadata that could identify you. Platforms record metadata with every post—timestamp, location data, device information. Stripping this data makes you harder to identify even if the account is compromised.

Legal Preparation

Second, know the law. Understand what First Amendment protections apply to anonymous speech. Know what the legal standard is for unmasking. Having this knowledge means you're prepared if a summons comes.

Third, build relationships with civil rights organizations before you need them. The ACLU, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and other groups provide legal support to activists facing government pressure. If you're already in contact with them, you're better positioned to get quick legal help if needed.

Fourth, document your activities. Keep records of what you post and why. This documentation became crucial in Doe's case—it showed that Mont Co Community Watch's content was innocuous and focused on community organizing, not threats.

Organizational Measures

Fifth, if you're part of a group, establish clear communication protocols. If one account holder is compromised, the group should have ways to continue operating. Don't concentrate all your documentation in one account.

Sixth, consider diversity of platforms. If all your monitoring happens on Instagram, you're vulnerable to an Instagram-specific attack. Spread activities across multiple platforms.

Seventh, build public visibility for your group (not your identity, your group). The more people know about Mont Co Community Watch, the harder it is to shut down quietly. Public awareness creates accountability—if the group suddenly vanishes or its accounts get deactivated, people notice.

The Bigger Picture: Government Surveillance and Chilling Effects

Beyond the specific case of DHS and ICE critics, this story illustrates something broader: how government can use the threat of surveillance to discourage political speech.

Even if DHS ultimately fails to unmask accounts, the attempt itself has a chilling effect. If you know that a government agency might demand your identity for criticizing it, you might think twice about posting. You might self-censor. You might avoid using your real name and face even more risk.

This is particularly true for vulnerable populations. Undocumented immigrants criticizing ICE face unique risks. If they know their identity might be revealed to a deportation agency, they're much less likely to speak up. The chilling effect is even more severe.

First Amendment Under Pressure

The First Amendment is increasingly tested by technology and government power. Platforms can surveil users in ways unimaginable a decade ago. Governments can demand data with relative ease. And people often don't realize that what they post publicly is logged and stored and potentially accessible to authorities.

What makes Doe's case important is that it shows the First Amendment still offers real protection. The government can't just demand subscriber information and expect to get it. There are legal obstacles. There are platforms that notify users. There are civil rights organizations that will fight.

But those protections exist only because people use them. If activists don't file motions to quash, they lose the opportunity. If platforms stop notifying users, the window closes. If civil rights organizations run out of resources, the legal support disappears.

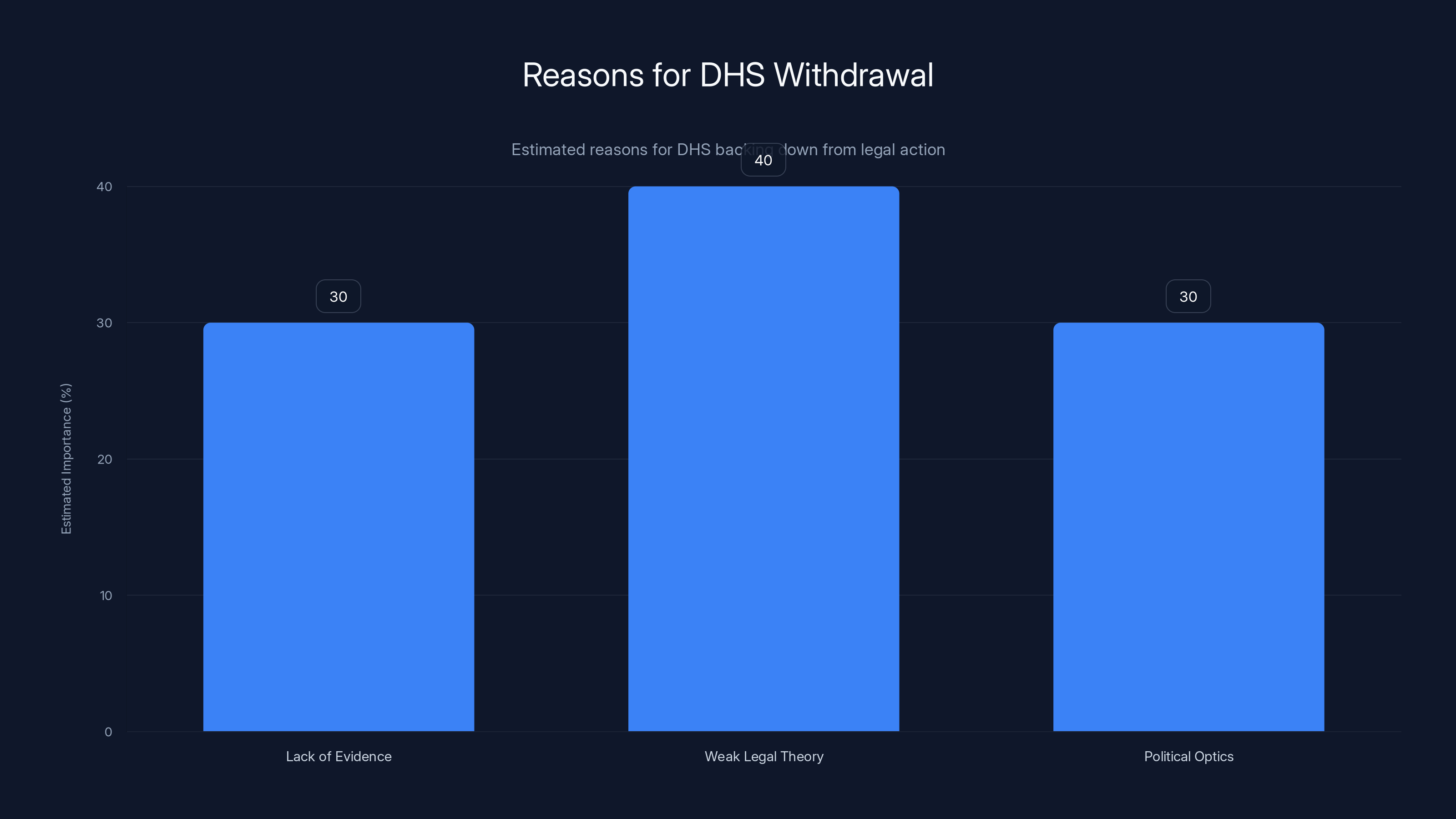

The chart estimates that weak legal theory and political optics were significant factors in DHS's decision to withdraw, alongside a lack of evidence. Estimated data.

International Perspective: How Other Democracies Handle This

The United States isn't the only country struggling with the tension between government surveillance and anonymous speech. Other democracies have developed different approaches.

In Germany, there's a principle of "Anonymität im Netz" (anonymity on the net) that provides stronger default protections for anonymous online speech. Governments must meet higher evidentiary standards before platforms are required to unmask users.

In the European Union, the GDPR creates additional privacy protections that make it harder for governments to demand broad subscriber data without specific justification.

In the UK, there's been significant debate about online safety laws and how they interact with anonymous speech rights. The Online Safety Bill created new obligations for platforms but also protections for privacy.

These international examples suggest that there are different ways to balance government interests in law enforcement with private interests in anonymous speech. The United States' current approach—requiring court orders and allowing civil rights organizations to challenge them—is only one model.

The Future: What Could Change

DHS will likely try again. The agency has shown persistence in pursuing this legal theory, even after multiple failures. But what might change in the coming months and years?

Statutory Changes

One possibility is that DHS or other agencies push Congress to pass new legislation giving them clearer authority to demand subscriber information in national security or law enforcement contexts. Such legislation could bypass the current legal obstacles.

This is politically possible, especially in periods of heightened security concerns or when an administration decides to prioritize law enforcement authority over privacy rights.

Platform Changes

Another possibility is that platforms like Meta become less willing to fight government requests or notify users. If platforms face pressure from government or decide that opposing summonses is too legally costly, they might comply more readily.

Alternatively, platforms might implement policies that reduce anonymity—requiring phone number verification, collecting more identity data, or limiting anonymous account creation. Such policies would make it harder for activists to maintain anonymity.

Legal Strategy Evolution

DHS might also evolve its legal strategy. Rather than using the customs statute, future attempts might cite more direct legal authorities. Rather than seeking broad subscriber data, they might seek specific information in a more narrowly tailored way.

Each iteration of DHS's approach teaches them something about what courts will accept. Eventually, they might develop a strategy that succeeds.

Civil Rights Response

Civil rights organizations will likely continue to fight. But their resources are limited. If DHS increases the volume of summonses, some might slip through without legal opposition. Building stronger institutional support for these fights—perhaps through legislation protecting legal advocacy or requiring platforms to fund legal defenses—could strengthen resistance.

Critical Lessons: What This Case Teaches

Doe's victory offers several important lessons, both for activists and for the broader debate about digital rights.

First, Platforms Matter

Meta's decision to notify account holders made all the difference. That notification gave Doe time to organize a legal defense. Without it, the company could have simply handed over information. Requiring platforms to notify users about government requests should be standard practice, not the exception.

Second, Legal Support Changes Everything

John Doe had a lawyer. He had the ACLU behind him. Not every activist does. If DHS targets groups without legal support, the outcomes will likely be different. Strengthening the legal resources available to activists and creating clearer rights could help level the playing field.

Third, Documentation and Evidence Matter

When Doe's lawyers showed the court the actual content of the Instagram account, it contradicted DHS's narrative. That evidence made a huge difference. Keeping records of your activities, being able to demonstrate what you actually posted, and not posting things that can be mischaracterized as threats—these practical steps matter.

Fourth, Coordination Works

Doe's case is part of a larger pattern where multiple groups have fought and won against DHS. That pattern of success creates precedent (even if informal) and makes it harder for DHS to justify future attempts. When groups coordinate and share information, they become stronger.

Fifth, Political Context Matters

DHS's withdrawal likely had something to do with the political environment. ICE criticism was at historic levels. House Democrats were voting to defund. The optics of trying to silence critics didn't favor DHS. Political pressure and public awareness can influence government behavior.

Questions Remaining: The Unfinished Story

Doe's case raises questions that remain unanswered, and they matter for understanding what happens next.

Why Does DHS Keep Trying?

What drives DHS to keep attempting to unmask critics despite consistent failures? Is it a genuine search for a winning legal theory? Is it strategic intimidation? Is it simply institutional inertia—bureaucrats following procedures without considering whether they work?

Understanding motivation matters for predicting future behavior.

What About Groups Without Legal Support?

Everything in Doe's case depended on sophisticated legal defense. What about smaller groups, less visible groups, or groups with fewer resources? How many summonses are issued that never get challenged because people don't know they can fight them?

Will Platforms Evolve?

Meta's role was crucial but also limited. The company didn't fight the summons—it just notified the account holder. As platforms face increasing government pressure and as they accumulate more user data, will they remain willing to give users time to fight? Or will they start cooperating more readily?

Could This Approach Work Against Other Targets?

DHS's strategy of using obscure statutes to unmask online speakers could be applied in other contexts. Could immigration agencies use it against critics? Could other law enforcement agencies? Could it spread?

Conclusion: The State of Anonymous Speech in 2025

John Doe won his case, and that matters. But his victory is neither definitive nor final. DHS backed down, but the agency could try again. The legal precedent protecting anonymous speech remains strong in principle but vulnerable in practice.

What we're seeing is a crucial moment where the First Amendment meets modern technology and government power. The rules that protected anonymous speech in the pre-internet era are being tested by platforms that collect vast amounts of data and governments that have unprecedented surveillance capabilities.

The outcome of this conflict will shape digital rights for years to come. If civil rights protections hold, if platforms continue to notify users and give them time to fight, if legal support remains available, then anonymous speech should survive. But those "ifs" are significant.

For activists and community organizers, the lesson is clear: you can fight back. You can win. But you need to know your rights, you need legal support, you need to move quickly, and you need to be strategic about security.

For policymakers, the lesson should be equally clear: the current system depends on civil rights organizations filling a gap that government isn't filling. Platforms are acting as impromptu privacy protectors, which is both fortunate and fragile. A more robust, legal framework protecting anonymous speech might be necessary.

For platforms, the lesson is that users—and the public—care about privacy protections. Companies that stand up for user rights, like Meta did here (even if imperfectly), build trust and goodwill. Those that become too willing to cooperate with surveillance lose credibility.

Most importantly, Doe's case demonstrates that the First Amendment still works. It's been tested, challenged, and pressured, but it still provides real protection for anonymous critics of the government. That protection depends on people using it—filing motions to quash, challenging legal overreach, standing up for their rights.

DHS will likely try again. But next time, they'll be trying against a community of activists who know the playbook, who understand their rights, and who have shown they can win. That's not a guarantee of future victories, but it's not nothing either.

The fight for anonymous speech online is far from over. But for the first time in months, the people trying to expose the activities of a powerful government agency got to remain anonymous anyway.

FAQ

What is anonymous online speech and why is it protected?

Anonymous online speech refers to content posted on the internet without revealing the author's real identity. It's protected under the First Amendment because decades of court cases have established that anonymity is essential for political speech, especially when criticizing the government. People might self-censor or face retaliation if forced to speak publicly, so anonymity enables crucial democratic discourse.

How does the legal standard for unmasking anonymous speakers work?

Courts generally require that before unmasking an anonymous speaker, the party seeking the information must prove necessity (the information is actually needed), exhaustion of alternatives (they've tried other methods), proportionality (the benefit outweighs the privacy harm), and specific grounds (not a fishing expedition). This standard protects speakers while allowing legitimate law enforcement in cases of actual criminal conduct or genuine threats.

What role did Meta play in protecting John Doe's identity?

When DHS issued a summons, Meta didn't immediately comply. Instead, the company sought clarification from the government and notified John Doe that his information was being requested. This notification period was critical—it gave Doe time to file a motion to quash the summons before Meta had to release any data. Meta essentially acted as an intermediary, creating a legal window for users to defend their rights, as noted by Jakarta Globe.

Why was DHS using a customs statute to unmask ICE critics?

DHS invoked a statute governing the importation and exportation of merchandise, which seemed like an odd choice. The agency was apparently testing whether they could stretch this statute's boundaries to claim broad subpoena authority over online content. If successful, it would have set a precedent allowing DHS to unmask critics by using indirect legal hooks rather than direct statute law, as discussed by Inkl.

What is the "playbook" that community watch groups use to defend against unmasking?

The playbook consists of: waiting for platform notification of government requests, quickly filing a motion to quash the summons, presenting actual evidence (the actual content of posts) to contradict government characterizations, challenging the government's legal theory, and building public visibility around the group so sudden disappearance would be noticed. This combination of legal and practical tactics has proven effective in multiple cases.

What could happen if DHS tries again with a different legal approach?

DHS could develop more sophisticated legal theories, more narrowly tailored information requests, or might target groups without legal support or public visibility. They could also push Congress for new legislation clarifying government subpoena authority. Alternatively, platforms could change notification policies or become more willing to comply with requests, closing the legal window activists currently rely on to fight unmasking attempts.

How does this case affect undocumented immigrants and other vulnerable groups?

For undocumented immigrants criticizing ICE, the stakes of unmasking are existential—revelation could lead to deportation. Other vulnerable groups face harassment, employment loss, or retaliation. These groups benefit from anonymous speech protections but are most at risk if those protections erode. The case illustrates why First Amendment protection of anonymity matters most for those with the most to lose.

What technical steps can activists take to protect their anonymity?

Key steps include using a VPN when creating and accessing accounts to hide your real IP address, using an email address unlinked to your real identity, accessing accounts only from dedicated devices not associated with your actual identity, avoiding location tagging and metadata, and using platforms' privacy settings maximally. None of these provides perfect protection, but layering multiple technical measures significantly increases security.

Why is this case important beyond the specific incident?

The case tests fundamental questions about government surveillance, corporate responsibility, and digital rights. It shows whether First Amendment protections for anonymous speech actually work in practice, whether platforms will side with users or governments, and whether civil rights organizations can effectively defend digital rights. The outcomes will influence similar cases for years to come.

What would strengthen protections for anonymous online speech?

Potential reforms include: legislation requiring platforms to notify users of government data requests, establishing higher legal standards for government surveillance demands, creating funding for civil rights organizations defending digital rights, implementing stronger data minimization requirements for government agencies, and building transparency into platform compliance with government requests. International privacy frameworks like the GDPR offer additional models worth considering.

Key Takeaways

- DHS repeatedly attempted and failed to unmask anonymous ICE critics using broad data demands, ultimately withdrawing summonses after legal opposition.

- Community watch groups developed a tested playbook: platform notification, quick legal motions, evidence presentation, and legal theory challenges.

- Meta's role in notifying account holders proved crucial, creating a legal window for defenders to organize and file protective motions.

- First Amendment protections for anonymous political speech remain strong in principle but depend on active legal defense and platform cooperation.

- Technical measures like VPNs, separate devices, and metadata stripping, combined with legal support, provide realistic protection for activist anonymity.

Related Articles

- FBI Device Seizure From Washington Post Reporter: Journalist Rights and First Amendment [2025]

- Microsoft BitLocker Encryption Keys FBI Access [2025]

- Age Verification & Social Media: TikTok's Privacy Trade-Off [2025]

- Freecash App: How Misleading Marketing Dupes Users [2025]

- TikTok's US Deal Finalized: What the ByteDance Divestment Means [2025]

- State Attorneys General Fight Trump: The Last Constitutional Check [2025]

![How DHS Keeps Failing to Unmask Anonymous ICE Critics Online [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-dhs-keeps-failing-to-unmask-anonymous-ice-critics-online/image-1-1769200731615.jpg)