Introduction: When Law Enforcement Borrows Military Identity

There's a dangerous blurring happening at the border of American law enforcement. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents are showing up to raids in combat gear, tactical formations, and weaponry designed for actual warfare. They're describing operational zones as "theaters." They're using terminology pulled from military doctrine. They're operating with a level of force that would be considered excessive in the actual military context they're trying to mimic.

The problem isn't that ICE officers are incompetent. It's that they're being trained, equipped, and directed to behave like something they're not: military units conducting combat operations. And that mismatch between identity and reality creates cascading failures in tactics, judgment, and outcomes.

I'm not a border policy expert. I'm not here to argue whether immigration enforcement should be more or less aggressive. But I spent years in military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I've watched ICE operations closely over the past year. What stands out isn't the toughness of their approach. What stands out is how badly they're executing the military tactics they're mimicking, and why that matters strategically.

When an agency adopts military equipment and military language, it invites military-level scrutiny. And under that scrutiny, what emerges is a picture of an organization that doesn't understand its own mission, equipment, or tactical purpose. The raids in Minneapolis in 2025 provided a crystalline example of this confusion. So did operations across the country. Watching ICE officers bunch up in doorways, brandish weapons at people who posed no physical threat, and move with zero tactical discipline felt like watching a paramilitary organization that had learned tactics from action movies instead of actual doctrine.

The real danger here isn't just legal exposure or civil rights violations, though those matter. The real danger is strategic. When a law enforcement agency operates like an occupying military force, it creates the exact conditions that fuel resistance, legal challenges, and ultimately, failure of the broader mission.

Let's break down what's happening, piece by piece.

TL; DR

- ICE equipment and uniforms lack standardization and are often inappropriate for civil law enforcement, combining military gear with civilian clothes in ways that confuse everyone involved

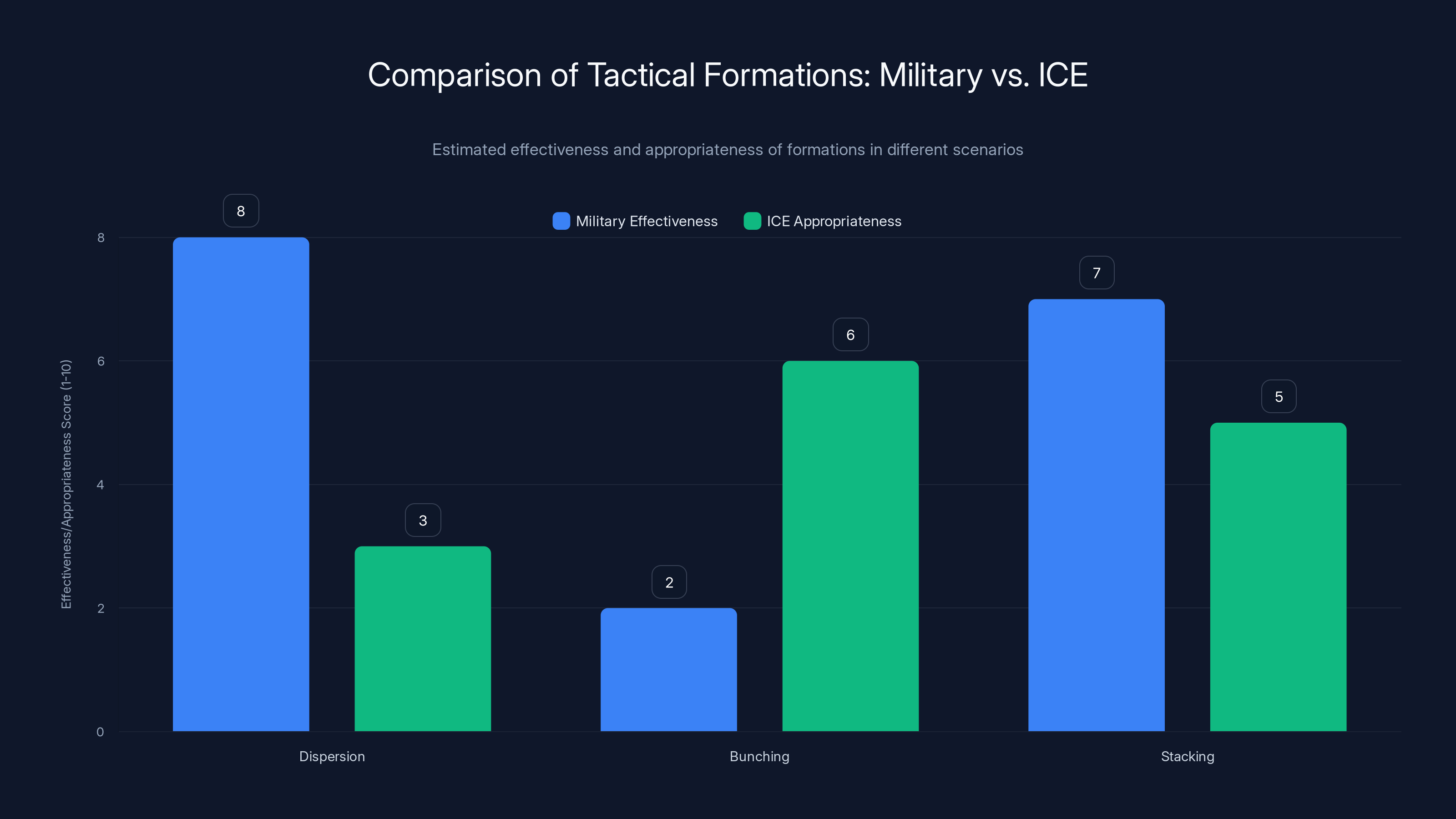

- Tactical formations used by ICE (doorway stacking, clustering, poor dispersion) would be considered suicidal in actual combat and demonstrate fundamental misunderstanding of military doctrine

- Weapons carry unnecessary attachments (optics, silencers, magazine pouches) that make firearms heavier and less effective while signaling force rather than precision

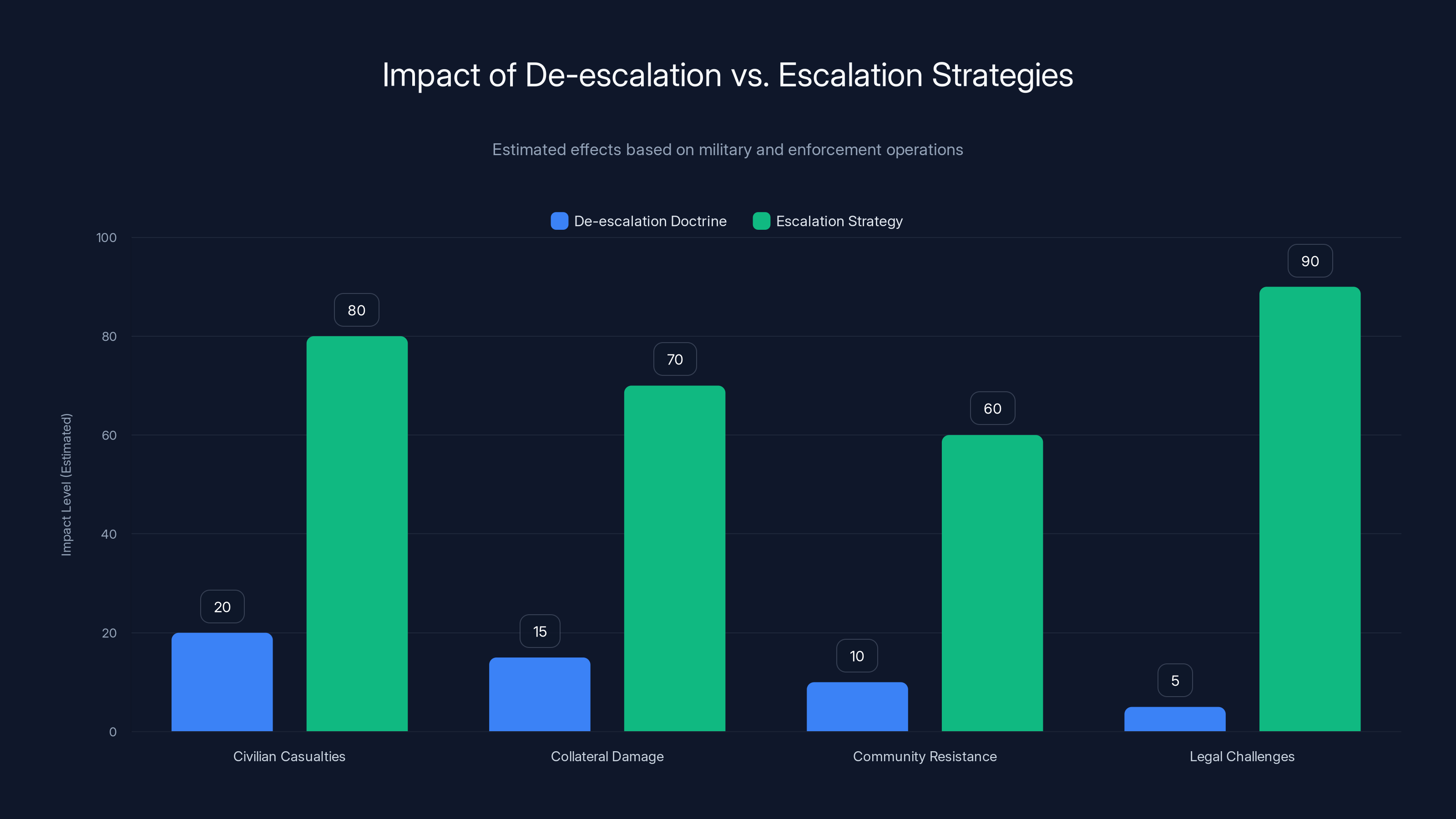

- De-escalation is absent from ICE operations, contrasting sharply with two decades of counterinsurgency doctrine that showed escalation creates more violence and resistance

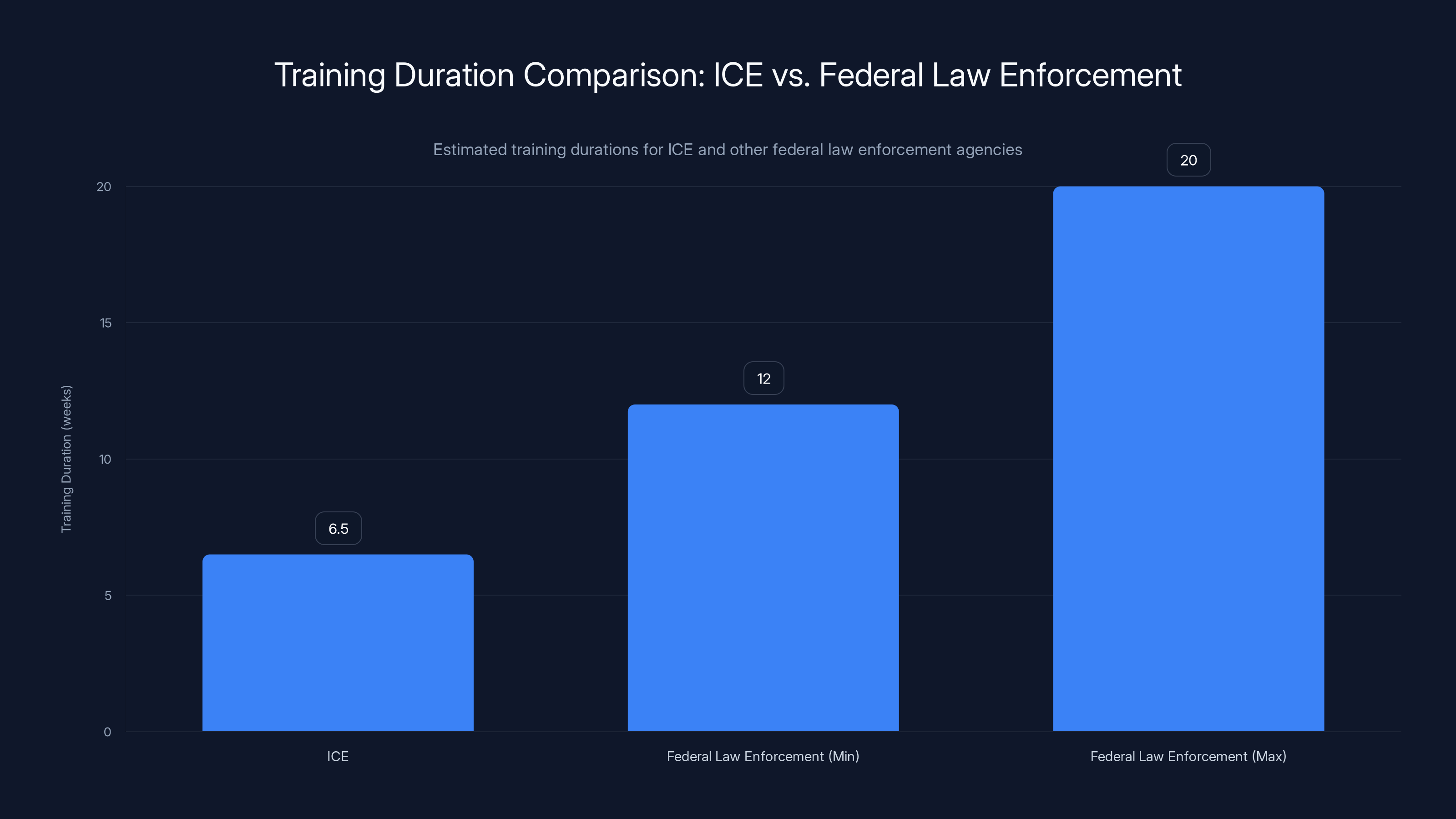

- Training duration is dangerously short (6.5 weeks) compared to actual military entry training (16+ weeks), leaving gaps in situational awareness and decision-making

- Mission clarity is lacking, with officers appearing confused about their actual objectives and often targeting innocent bystanders in the process

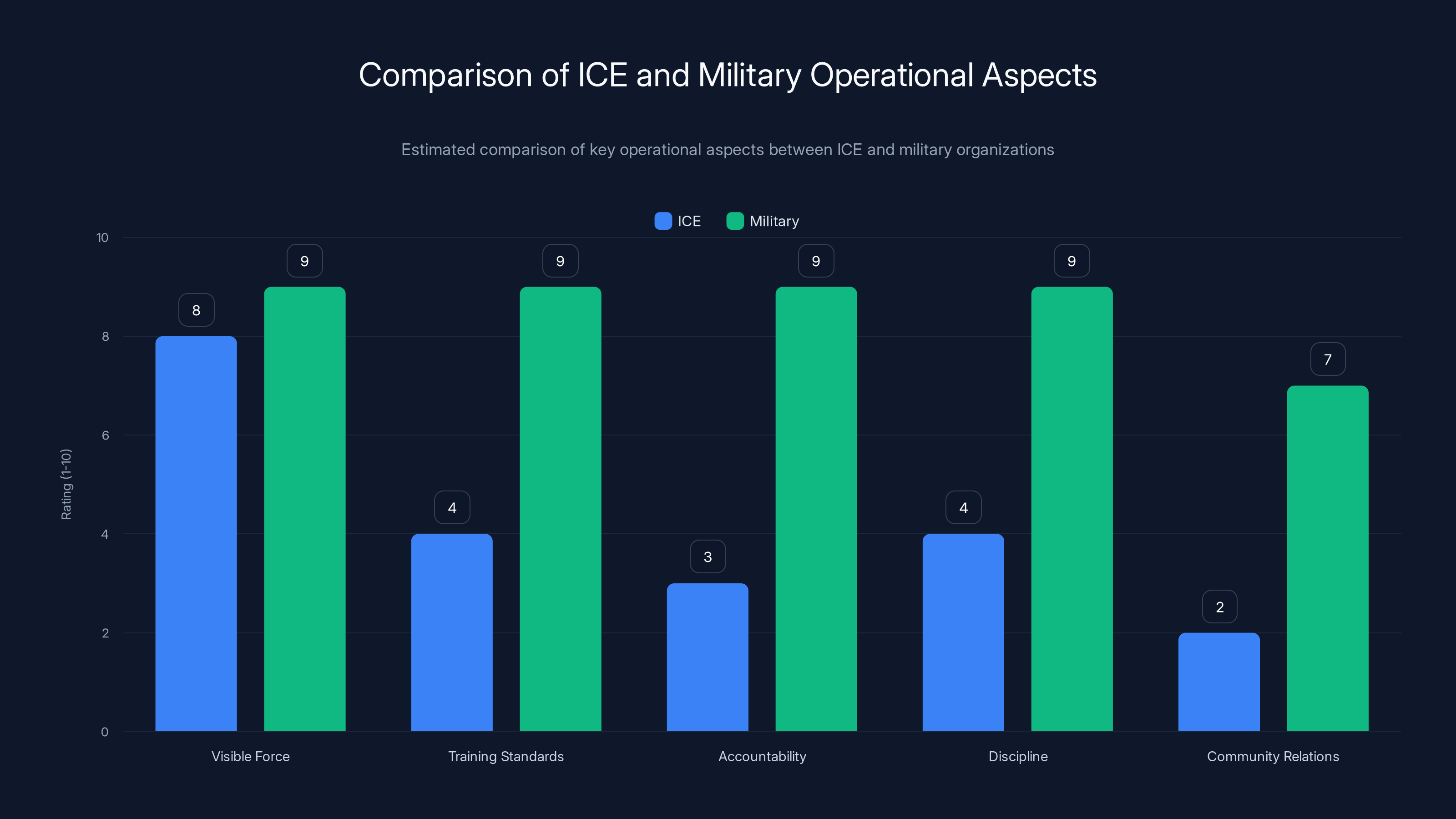

ICE's training duration is significantly shorter than other federal law enforcement agencies, potentially impacting tactical decision-making quality. Estimated data.

The Equipment Problem: Cosplaying Combat Without Understanding Combat

Let's start with the physical stuff. Equipment selection reveals how an organization thinks about its mission.

In actual military operations, soldiers match equipment to the specific mission. A jungle counterinsurgency looks different from an urban raid, which looks completely different from a convoy escort through flat desert. You don't bring the same load-out to every mission because different missions have different threats, different terrain, and different goals.

ICE agents, by contrast, seem to bring the same maximum-force setup to every operation. Ballistic helmets. Plate carriers rated for rifle rounds. Magazine pouches positioned on the legs like they're expecting a sustained firefight. Weapons loaded with tactical attachments that would make a combat infantryman laugh: rail-mounted optics, silencers (which, in a civilian law enforcement context, are honestly just weird), flashlights, lasers, and accessories stacked like a Pinterest board of gear acquisitions.

This is important: a soldier oversaturated with gear becomes less effective in an actual fight. Each attachment adds weight. Weight reduces mobility. Reduced mobility means slower reactions, more fatigue, worse situational awareness. It's basic physics. The tactical operators who actually clear buildings in combat zones typically run relatively clean setups because they understand through experience that less is more. A pistol, a rifle with a red dot and maybe a flashlight, body armor rated for the actual threat. That's it.

ICE agents aren't carrying that way. They're carrying like they watched a tactical gear commercial and bought everything. And that choice—that equipment selection—tells you something important: they're not thinking about the actual threat they're responding to. They're thinking about how they want to look.

Then there's the uniform question. In the Minneapolis raids and elsewhere, ICE agents showed up in a patchwork of gear. Some in tactical vests with labeling. Some in hoodies. Some in masks. Some in baseball caps. Some in ballistic helmets. When you see a raid video and you can't immediately tell who's law enforcement and who's not, you have a uniform problem. Real military units solve this problem because it matters: you need to know who's on your team when things get chaotic. Bad uniform discipline leads to friendly fire. It leads to civilian confusion. It leads to situations where people don't know whether they're being detained by police or targeted by criminals (ICE raids are often confused with kidnappings for exactly this reason).

The military solution to this is boring: everyone wears the same thing in the same way. It's standardized. It's clear. ICE has somehow made the opposite choice, where every agent seems to have interpreted "tactical gear" differently.

Here's another thing: in 20 years of counterinsurgency operations, military units learned that the way you show up to an interaction shapes the entire interaction. Show up maximized, and people respond to the threat. Show up measured, and you create space for compliance without escalation. This isn't soft strategy. It's hard tactical doctrine based on thousands of operations.

ICE's equipment strategy communicates something very specific: "We expect violent resistance from people who haven't demonstrated any intent to resist violently." That's a bet. And it's being made before any actual threat assessment.

De-escalation strategies significantly reduce civilian casualties, collateral damage, and community resistance compared to escalation strategies, which lead to higher legal challenges. Estimated data based on documented military doctrine.

Tactical Formations: Bunching and Confusion

Now let's talk about how ICE officers actually move when they're executing a raid.

In military doctrine, there's a concept called "dispersion." It's simple: don't put all your people in one place. If you bunch up, a single burst of fire, a grenade, an IED—any concentrated attack—can take out multiple team members simultaneously. So soldiers train to spread out, maintain sight lines to teammates, and always have covered and supporting positions. You're taught this in basic training. You rehearse it hundreds of times. It's muscle memory.

Videos of ICE raids show the opposite. Agents bunching up around a doorway. Multiple people in tight clusters. Crowded together in hallways and entryways. In a building where there's actual gunfire, this formation would be a massacre waiting to happen. One automatic weapon, one grenade, one person who knows what they're doing—and you've got multiple casualties from a single moment of contact.

But here's the thing: there isn't actual gunfire in these raids. There are civilians. Potentially armed civilians, but civilians nonetheless. People being arrested, not combatants being engaged. So why train like you're in a firefight?

The answer seems to be: because it looks intimidating.

This is where the costume aspect of the militarization really shows. ICE agents are using tactical formations not because those formations are appropriate for the mission, but because they look like military formations. They're performative. And that performance-over-function approach shows up constantly in how they execute operations.

One common ICE tactic is "stacking" on a door. This is a real military technique used in close-quarters combat when you need to breach an entry quickly and violently. You stand in a line along the side of the door, each person compressed behind the previous one, ready to move through. It's tight. It's aggressive. And it's designed for situations where surprise and violence of action are your advantage.

For serving a civil arrest warrant at someone's home? This is theatrical. It's not tactical. It's a statement. It says, "We're treating you like an enemy combatant," which in turn says, "We expect you to resist violently." And that expectation shapes how the person being arrested responds.

Military tactics designed for combat situations don't map cleanly onto civil law enforcement because the threat profiles are different. But more importantly, they communicate a threat level that creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Show up maximized, and the person you're arresting has less reason to comply peacefully.

In Iraq, we learned this lesson repeatedly. Units that arrived at a location with minimal force, that de-emphasized the threat, that communicated through body language that they were there to execute a specific mission rather than wage war—those units had fewer incidents, fewer civilian casualties, and paradoxically, more effective operations. Counterinsurgency doctrine that emerged from 20 years of operations essentially boils down to: precision beats maximization.

ICE operations seem to operate on the opposite principle: maximization beats precision.

Weapon Handling: When Your Gun Becomes a Statement

Watch ICE raid videos and you'll see something that happens repeatedly: weapons being brandished. Not pointed at a specific target, not maintaining discipline toward a threat—just displayed. Held up. Visible. Meant to communicate force.

In military training, you learn early: you point your weapon only at something you intend to shoot. This isn't arbitrary. It's foundational to preventing accidental discharges, to maintaining discipline, and to ensuring that when a weapon is presented, it means something.

ICE agents brandishing weapons at people who pose no active threat violates that basic discipline. And there's a reason it matters: it changes how the person being arrested perceives the threat. It tells them, "You are one sudden movement away from being shot." That perception changes behavior. Sometimes toward compliance, but sometimes toward panic, flight, or desperate resistance.

A person who perceives imminent lethal threat will sometimes act like it's imminent. They'll run. They'll fight. They'll do things they wouldn't do if they understood they were being detained by police executing a civil warrant.

Weapon discipline is about more than safety (though it's absolutely about safety). It's about communication. And ICE's weapon discipline in these operations communicates escalation.

Then there's the customization issue. I mentioned this before, but it's worth drilling into. ICE officers are carrying weapons set up like they're running a tactical team clearing a hostile structure. Attached optics, weapon lights, rails, accessories everywhere. This is normal in military units because soldiers might actually need to shoot accurately at distance or in low light.

ICE agents are conducting arrests in populated areas. In daylight, mostly. Against people who don't have weapons. So why the setup?

Because the setup looks cool. It communicates dominance. It says, "I'm a trained tactical operator." And it's completely inappropriate for the mission.

A simpler approach—a firearm with minimal attachments, carried with discipline—would be more effective, would communicate less threat, and would actually be more practical for the actual situations ICE faces. But that's not what's happening.

Military formations like dispersion are highly effective in combat, while ICE's use of bunching and stacking is more about intimidation, with lower appropriateness for civilian raids. Estimated data.

Training Gaps and the TV/Movie Problem

Here's something that might explain a lot: ICE officer training is, by standard measures, very short.

Military entry training for soldiers runs 16+ weeks. Law enforcement typically runs 12-20 weeks depending on the agency. ICE officer training runs about 6.5 weeks. That's half the time of military basic training, a quarter the time of typical law enforcement academies.

In 6.5 weeks, you can teach people to follow procedures, to understand legal authorities, to operate equipment. What you can't do is build muscle memory for complex tactical decision-making. You can't run enough scenario-based exercises to build real situational awareness. You can't rehearse enough variations of actual situations to develop judgment that holds under stress.

So where does the tactical knowledge come from?

Some of it from formal training, yes. But some of it, almost certainly, from movies and television. From video games. From other officers who learned from movies and television. When your training is that condensed, pop culture becomes your backup instructor.

And you can see it in how ICE operations look. The stacking formations look like they came from a SWAT drama. The gear customization looks like a tactical gear catalog. The way agents move through spaces looks theatrical, designed to look intimidating rather than designed to be tactically sound.

Real military units don't move like that because they learn through repetition and live scenarios what actually works. They learn that minimal force works better. That communication works better. That precision works better. ICE, with far less training, seems to be learning from entertainment media instead.

Mission Confusion and Collateral Impact

One of the most striking things about watching ICE operations is the apparent confusion about what the mission actually is.

A military unit going into a target location has explicit intelligence about the target. They know who they're looking for, what that person has done, what they might be armed with, whether there are civilians in the location. They plan accordingly. They brief. They rehearse. They move with a specific objective.

ICE raids frequently seem to involve officers who aren't entirely sure who they're looking for or why. Videos show agents stopping, detaining, and arresting people who clearly have no connection to the stated target. Family members. Neighbors. Bystanders. People simply in the wrong place.

This happens because the operation was never precisely targeted. The intelligence was vague or outdated. The briefing was incomplete. The officers executing it don't have clear identification protocols.

In military terms, this is a massive tactical failure. If you're arresting the wrong people, your intelligence was bad. If your intelligence is bad, your planning was bad. If your planning was bad, your training and briefing weren't adequate. Each layer is a failure.

But in the immigration enforcement context, it seems almost accepted. Collateral detentions. Arresting family members with no violations. Stopping people for immigration status checks who have nothing to do with the stated target.

From a strategic perspective, this is catastrophic. Every person who gets detained despite having no violations, every family member arrested, every case where ICE operations traumatize innocent people—each one of those situations generates resistance. Legal challenges. Community distrust. People who will actively avoid cooperating with authorities in the future.

In counterinsurgency doctrine, this is understood thoroughly: overly broad enforcement creates more enemies than it stops. Precision targeting, by contrast, allows some level of community cooperation and reduces backlash.

ICE operations seem designed to create maximum collateral impact. Whether intentional or not, the effect is the same: everyone gets treated as a potential violator, everyone's movements are restricted, everyone's family is at risk.

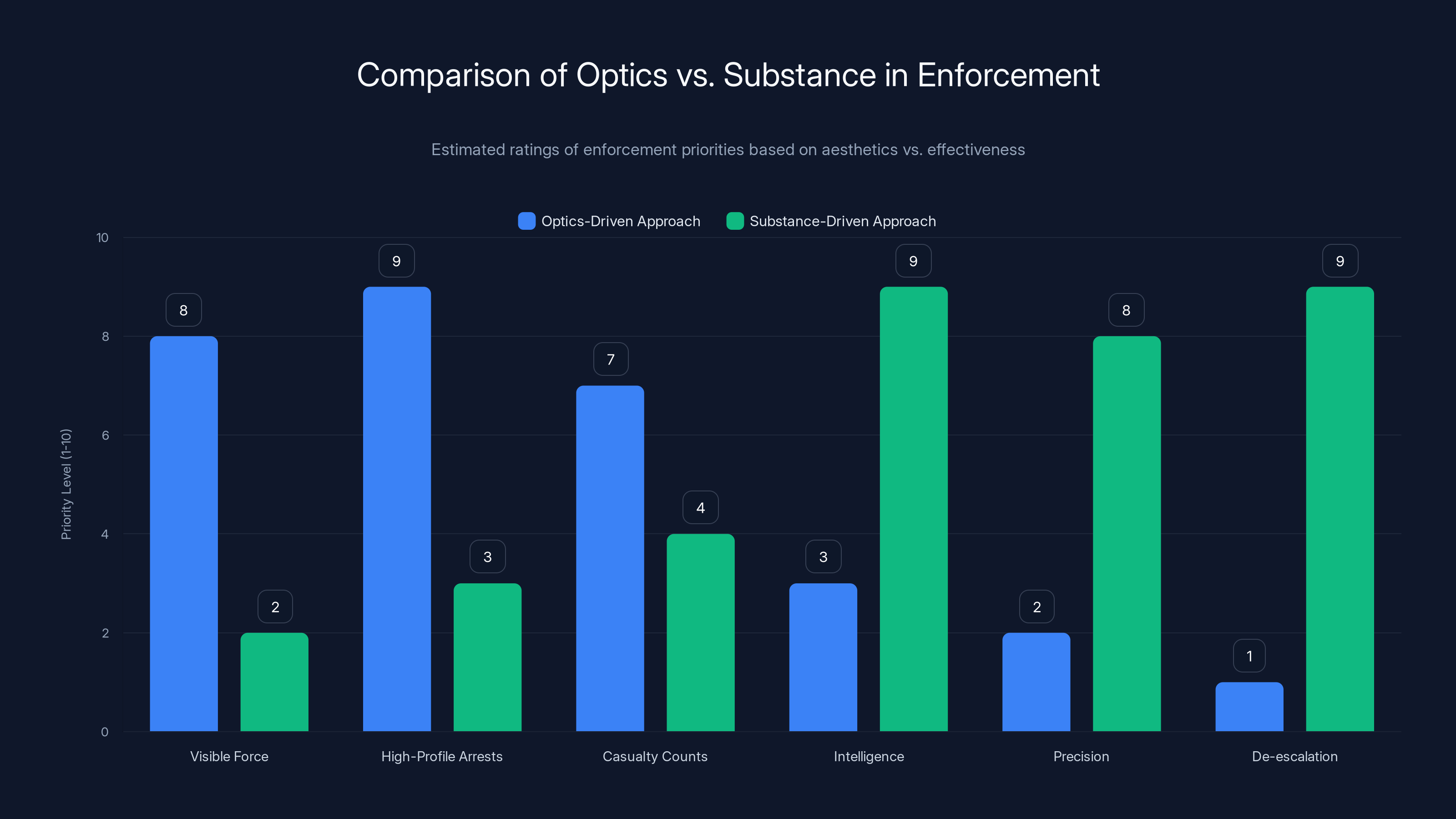

Estimated data suggests that an optics-driven approach prioritizes visible force and high-profile arrests, while a substance-driven approach focuses on intelligence and precision.

De-escalation Doctrine vs. Escalation Strategy

Two decades of military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan taught one consistent lesson: escalation is expensive.

When units de-escalated, when they approached situations with minimal force and clear communication, civilian casualties dropped. Collateral damage dropped. Resistance dropped. The logical chain is simple: if you humiliate people, kill their relatives, or treat them as enemies when they're civilians, their families and communities become enemies. That's not speculation. That's documented military doctrine from the single longest counterinsurgency effort in modern history.

The inverse is also true: de-escalation, precision, and restraint create conditions where communities are more likely to cooperate. Where there's less violent resistance. Where enforcement actions achieve their stated goal rather than generating new grievances.

ICE operations, by contrast, seem designed around escalation. Maximum force appearance. Brandished weapons. Intimidating tactics. The assumption seems to be that showing up harder will produce faster compliance.

But here's what military experience shows: faster compliance through intimidation is often apparent rather than real. People comply out of fear, not out of belief in the legitimacy of the enforcement. And the moment they're safe from the immediate threat, they challenge the enforcement through legal mechanisms. They file lawsuits. They demand investigations. They support political opposition to the agency.

Precision enforcement, by contrast, generates less legal blowback because it's harder to argue against. You weren't intimidated into something you didn't do. You weren't collaterally arrested. You weren't subjected to excessive force. The enforcement was proportional to the violation.

This isn't a philosophical point. It's a practical one. Escalation-based enforcement requires more legal resources to defend against lawsuits, more political resources to defend against criticism, more operational resources to manage the backlash. De-escalation-based enforcement costs less in all those domains.

ICE, from a strategic standpoint, is operating backward. It's creating its own resistance. And then it's surprised when that resistance manifests legally and politically.

The Strategic Problem: Creating the Enemy You're Prepared For

Let's zoom out to strategy. Because this is where the real danger sits.

When an organization equips itself, trains itself, and deploys itself like a paramilitary force, it's essentially preparing for a certain type of enemy. An armed, organized, hostile enemy. A military-like enemy.

But immigration enforcement isn't against military enemies. It's against people who violate civil law. Most of them don't want confrontation. Most of them, if given the option, would prefer to simply not be arrested.

So when ICE shows up armed, intimidating, using maximum force tactics, what's actually happening is the creation of the very condition it's prepared for. You're treating people like enemies, and some percentage of them will respond like enemies. You'll get resistance. You'll get flight. You'll get situations that escalate into actual confrontations.

And then the agency can point to those confrontations and say, "See? We need all this equipment and these tactics." But the confrontations were generated by the tactics. The enemy was created by the approach.

In military strategy, this is called a "self-fulfilling prophecy," and it's considered a massive failure. If your enemy posture creates enemies, your strategy is broken.

ICE's strategy seems broken in this way. The organization is structured and equipped for a conflict it doesn't actually have, which means it's misallocating resources and creating friction with communities that could be partners or at least neutral.

A law enforcement organization structured around precision, communication, de-escalation, and proportional force would likely face fewer confrontations, fewer legal challenges, and more community cooperation. It would be more effective at its actual mission.

ICE, by contrast, is sacrificing effectiveness for the appearance of toughness.

Estimated data shows ICE has high visible force but lacks in training, accountability, and discipline compared to military standards. This imbalance affects community relations.

Weaponizing Aesthetics Over Substance

Here's something that strikes me repeatedly when watching ICE operations: the concern for how things look.

The heavy gear. The tactical formations. The weapons displayed prominently. The multiple arrests at a single location (which creates visual impact). The way operations are sometimes conducted when media is present.

It's optics. Pure optics. And optics-driven enforcement is a problem because optics can override judgment.

A commander concerned primarily with the optics of toughness will prioritize visible force over actual effectiveness. Will pursue high-profile arrests over targeted enforcement. Will show up maximized because maximization looks powerful.

But a commander concerned with actual mission success will prioritize intelligence, precision, de-escalation, and outcomes. Will be willing to make arrests quietly if quiet arrests achieve the goal. Will use minimal force because that's more effective.

ICE seems to operate in the first mode. That's not necessarily intentional. It's often just the result of an organizational culture that values the appearance of being a tough enforcement agency more than the substance of effective enforcement.

Military units that became obsessed with optics rather than substance typically ended up doing worse in actual combat. They'd pursue engagement statistics rather than actual mission success. They'd prioritize casualty counts rather than stability and security. And their casualty counts would often be worse because they weren't optimizing for actual performance.

The analogy holds for ICE. An organization optimizing for the aesthetics of toughness will underperform an organization optimizing for effectiveness. And the communities it operates in will suffer from both the overreach and the ineffectiveness.

The Legal Exposure Problem

Let's talk about something ICE should be very concerned about: legal liability.

When you use force, especially visible force, against people executing civil law enforcement, you're creating a massive paper trail of potential civil rights violations. Each brandished weapon, each excessive force incident, each collateral arrest is a potential lawsuit.

And federal courts have established pretty clearly what the standard is: law enforcement can use force proportional to the threat. If someone's not armed, not resisting violently, and not posing an active threat, then the use of force is disproportional and thus unconstitutional.

ICE's approach—maximized force appearance against people who aren't typically armed or violently resisting—creates a pattern of behavior that's legally vulnerable. And the organization is already seeing litigation. Multiple civil rights cases against ICE officers for excessive force, for wrongful detention, for violations of constitutional protections.

If the organization cared about legal exposure, it would pivot toward the exact opposite of its current approach. It would minimize force presentation. It would increase training on de-escalation. It would prioritize precision targeting over broad sweeps. Because those changes would immediately reduce the organization's legal vulnerability.

The fact that it's not making those changes suggests that legal exposure isn't the primary concern. Something else is driving the escalation. Maybe it's political pressure. Maybe it's cultural. Maybe it's just institutional momentum.

But from a basic risk management perspective, ICE's approach is indefensible. You're buying massive legal exposure to achieve... what? Faster arrests? More visible operations? Those aren't strategic goals. Those are aesthetic goals.

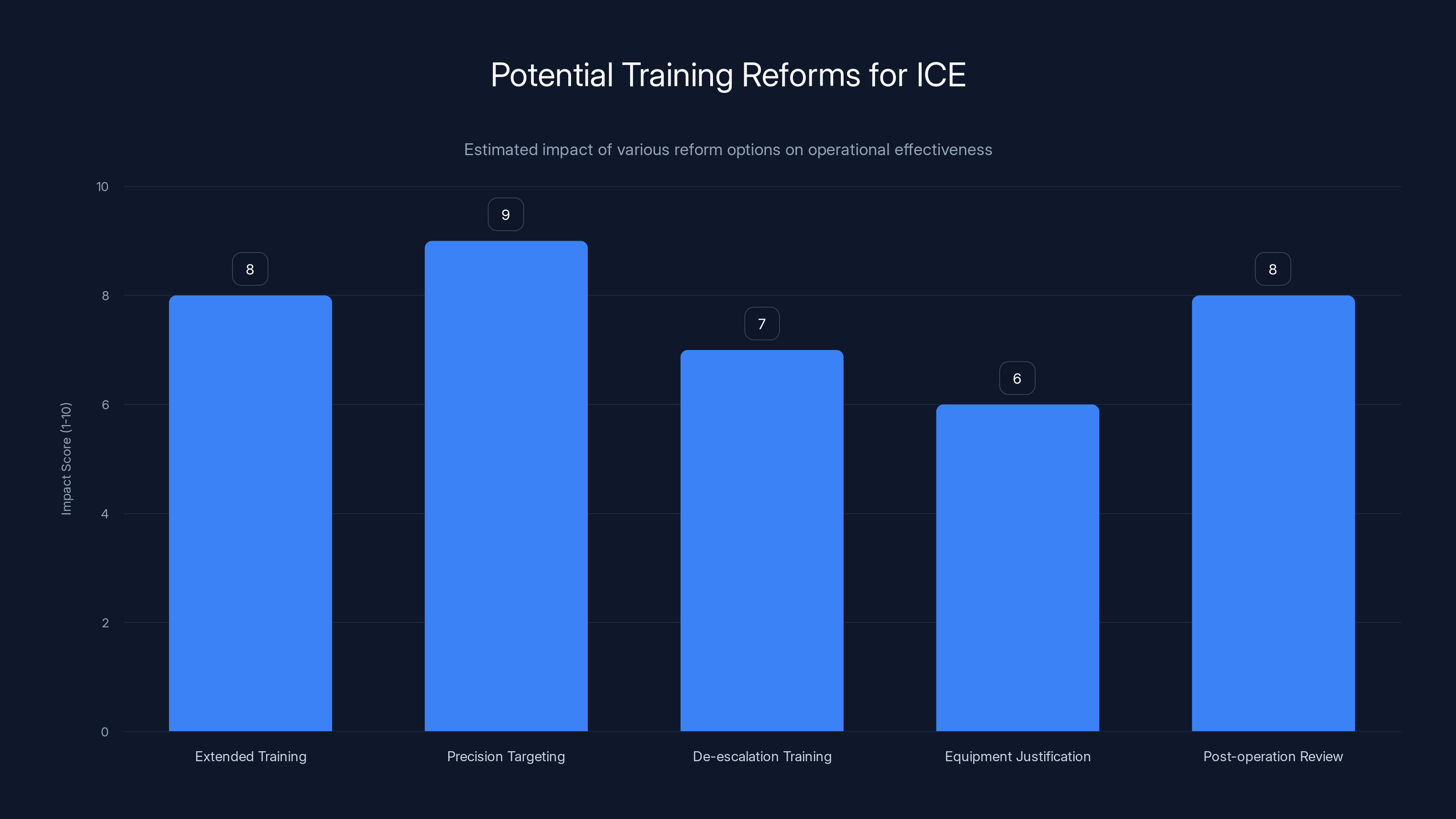

Estimated data suggests that adopting precision targeting protocols and extended training could have the highest impact on ICE's operational effectiveness.

The Comparison Point: How Actual Elite Police Units Operate

There are law enforcement units that operate with genuine tactical sophistication. FBI hostage rescue teams. SWAT units in major departments. Special response units in various agencies.

These units, almost universally, operate with far more restraint than ICE does. They use heavier gear in fewer situations. They select equipment carefully for specific mission types. They train extensively on decision-making under stress. They have clear rules of engagement that prioritize precision over maximization.

Why the difference? Because these units have had actual accountability for their decisions. They've been involved in situations where mistakes cost lives—lives of officers, lives of civilians, lives of hostages. That accountability creates discipline.

ICE, by contrast, operates with less accountability. There are internal reviews, but there's relatively less public scrutiny compared to SWAT units or FBI tactical teams. So there's less incentive to develop the restraint that comes from knowing your actions will be reviewed by expert eyes.

The result is an organization that's less tactically sophisticated than smaller, more specialized units. It's equipped like an elite tactical unit but operated with less discipline or restraint than those units maintain.

That's a dangerous combination. You get the visible aggression of a tactical unit with less of the actual training and judgment that justifies that aggression.

Transparency and Public Perception

One more strategic problem: perception and transparency.

ICE operations aren't secret, but they're also not particularly transparent. Videos emerge after the fact. Reports come out weeks or months later. By then, the damage to community trust is already done.

Compare that to military operations, which face intense scrutiny and documentation. Every civilian casualty is investigated. Rules of engagement are published. Military journalists embed with units. There's accountability built into the system.

ICE operations, by contrast, often seem to operate with the assumption that what happens in a raid is manageable after the fact. If there are questions, internal reviews will address them. If there's criticism, the organization can defend itself later.

But by then, community members have experienced what they experienced: armed agents showing up at their home, relatives being detained, invasions of privacy, trauma. The internal review doesn't undo that.

A more transparent organization—one that publicized its targeting criteria, explained its operational decisions, justified its use of force in real time rather than defensively after the fact—would likely face fewer political challenges. It would build more legitimate authority.

ICE seems to do the opposite. It operates first, explains later, and then acts surprised when communities don't trust it.

Training Alternatives and Reform Options

If ICE wanted to reform its operational approach, it has models to work from.

It could extend training significantly—bringing it to 12+ weeks like most federal law enforcement agencies. That would allow scenario-based training, decision-making under stress, de-escalation practice, and judgment development.

It could adopt precision targeting protocols more similar to what military special operations units use: extensive intelligence, clear identification of targets, operational security, minimal force application.

It could implement mandatory de-escalation training. Not as a theoretical exercise but as a practical, scenario-based program that teaches officers to recognize when maximum force is unnecessary and counterproductive.

It could change its equipment standards to require justification for tactical gear use. Rather than assuming full tactical load-out for every operation, require that officers demonstrate why heavy gear is necessary for a specific mission.

It could implement post-operation review processes that actually penalize excessive force or collateral impact, not just internally but with real consequences for officer advancement and retention.

None of these are revolutionary. They're all standard practices in organizations that care about effective, accountable enforcement.

ICE could adopt any or all of them. The fact that it hasn't suggests that the organizational incentives don't support reform. The incentives support visibility, toughness, and operational volume. Not precision, proportionality, or actual mission effectiveness.

The Future of Immigration Enforcement Strategy

This is worth thinking about at the strategic level. Immigration enforcement isn't going away. The political pressure for immigration control will continue. The question is whether ICE will continue its current trajectory or reform.

If it continues its current trajectory, expect more lawsuits, more community distrust, more political opposition, and ultimately, less effective enforcement. The organization will become more of a political lightning rod and less of an effective agency.

If it reforms—adopting precision-based tactics, extended training, de-escalation protocols, and proportional force standards—it would likely face less political opposition, fewer lawsuits, more community cooperation, and better long-term outcomes for enforcement.

From a purely strategic perspective, the reform path is obviously superior. It's cheaper legally, politically less expensive, and more effective operationally. The only reason to stay on the current path is if the visible toughness is the goal rather than the actual effectiveness of enforcement.

Which gets at the deeper question: what is ICE actually trying to achieve? If it's immigration enforcement effectiveness, the current approach is suboptimal. If it's demonstrating political willingness to be tough on immigration, the current approach makes sense.

Those two goals aren't always aligned. Sometimes being tough and being effective point in opposite directions. Right now, ICE seems to be choosing the tough-looking path over the effective path.

Systemic Issues and Accountability Mechanisms

Underlying all of this is a question of accountability. Who reviews ICE operations? Who determines whether tactics were appropriate? Who has the authority to modify or restrict operations?

Within the military, there are multiple layers of accountability: rules of engagement set by command, after-action reviews, investigation of civilian casualties, congressional oversight, inspector general reviews, and international law constraints.

ICE has some of these. There are internal review processes. There's Department of Homeland Security oversight. But there's less external accountability than the military faces. There's less international scrutiny. There's less documentation requirement.

That difference in accountability structure shapes behavior. When you know your actions will be reviewed by multiple layers of authority, you operate with more restraint. When accountability is lighter, restraint decreases.

Improving ICE operations would require increasing accountability. Making operations more transparent. Requiring justification for use of force decisions. Publishing data on collateral detentions, civilian complaints, and civil rights violations.

These changes would likely improve actual enforcement effectiveness while reducing legal exposure and community friction.

The Bottom Line: Military Aesthetics Without Military Discipline

Here's what stands out about ICE operations when viewed through a military lens: the organization has adopted military aesthetics—equipment, terminology, tactical formations, visible force—without adopting military discipline.

Military organizations have accountability mechanisms, training standards, rules of engagement, and cultural emphasis on proportional force. ICE has adopted the appearance of military operations without the infrastructure that makes military operations legitimate and controlled.

The result is an organization that looks like a paramilitary unit but operates with the discipline of a typical law enforcement agency—which isn't enough. You can't wear the costume of a tactical operator without the training, judgment, and accountability that justifies that costume.

If ICE wants to operate at the level of visible force it's currently employing, it needs to adopt the discipline, training, and accountability that justify that level. Alternatively, if it wants to maintain current training and accountability standards, it needs to significantly dial back visible force and maximize de-escalation tactics.

Right now, it's trying to do both. And that contradiction is creating problems across multiple domains: legal liability, community relations, operational effectiveness, and officer decision-making.

The military comparison isn't perfect—law enforcement isn't military, civilian law is different from military law, and the constraints are appropriately different. But the comparison is useful because it reveals the contradiction. You can't cherry-pick the visible parts of military operations without adopting the discipline that makes those operations sustainable.

ICE is currently trying to do exactly that. And it's showing in every raid video, every collateral arrest, every excessive force incident, and every community statement about distrust and fear.

A more sustainable path forward would require choosing: either adopt full military-style accountability and training, or step back from military-style visible force. The middle ground—military appearance without military discipline—is what's currently failing.

FAQ

What is the primary difference between ICE's operational approach and actual military tactical doctrine?

ICE adopts military aesthetics (equipment, formations, visible force) without corresponding military discipline and accountability. Real military units operate under extensive rules of engagement, multiple accountability layers, and trained decision-making protocols. ICE uses similar visible force tactics but without the training duration (6.5 weeks vs. 16+ weeks), rules of engagement clarity, or post-operation accountability mechanisms that justify such tactics.

How does training duration affect tactical decision-making quality?

Extended training allows scenario-based learning, muscle memory development for complex decisions, and judgment refinement under stress. ICE's 6.5-week training window (compared to 12-20 weeks for most federal law enforcement) leaves minimal time for judgment development. This gap is often filled by cultural knowledge, entertainment media, and informal officer training rather than systematic decision-making frameworks.

Why does excessive force appearance in ICE operations create strategic problems?

Excessive visible force against non-armed, non-resisting civilians violates proportionality standards in constitutional law and generates civil rights litigation. Strategically, it creates community distrust, reduces cooperation with enforcement efforts, and generates political opposition. Military experience from counterinsurgency operations shows that escalation without corresponding threat creates more resistance, not less.

What would a precision-based approach to immigration enforcement look like?

A precision-based approach would involve extended target intelligence gathering, clear identification protocols, minimal force application matched to actual threat level, de-escalation training prioritized over tactical gear accumulation, and post-operation reviews that penalize excessive force or collateral impact. This approach would reduce legal exposure, increase community cooperation, and likely improve actual enforcement effectiveness.

How does the "tactical stacking" formation used in ICE raids differ from its military application?

Tactical stacking is a close-quarters combat formation designed for violent breaches where surprise and overwhelming force are strategic advantages—applicable in actual combat scenarios. In civil law enforcement executing arrest warrants against non-armed civilians, stacking communicates excessive threat, creates unnecessary danger through clustering, and escalates the interaction unnecessarily. Military units use stacking only when the tactical situation justifies it; ICE appears to use it routinely.

What role does organizational accountability play in determining ICE's operational approach?

Organizations with higher external accountability (publication of data, independent reviews, congressional oversight, inspector general authority) typically maintain more restraint in force use. ICE operates with less external transparency than military units or FBI tactical teams, creating fewer incentives for restraint. Increasing accountability would likely decrease excessive force incidents and improve community relations.

How would extending ICE training duration change operational effectiveness?

Extended training (12+ weeks minimum) would allow scenario-based decision-making practice, de-escalation skill development, judgment refinement under stress, and reduced reliance on cultural knowledge or entertainment media for tactical understanding. Military evidence suggests that better-trained personnel make better decisions under stress, use force more proportionally, and have fewer collateral casualties and civilian rights violations.

Why is standardized uniform discipline important in enforcement operations?

Standardized uniforms serve multiple functions: they clearly identify law enforcement to civilians and reduce confusion with criminal actors, they ensure unit cohesion and mutual identification during operations, and they communicate professional authority rather than paramilitary appearance. When ICE agents show up in mixed gear (hoodies, masks, different helmet types), civilians can't immediately distinguish law enforcement from armed criminals, creating dangerous confusion and increasing likelihood of panic or resistance.

Key Insights for Reform and Future Direction

The gap between ICE's current approach and actual military operational standards isn't subtle. It's fundamental. An organization can adopt military equipment and terminology, but without the training, accountability, and discipline that justify those tools, it becomes something less effective than proper law enforcement and more aggressive than civil authority should be.

The path forward isn't complicated. It requires choosing between two options: either raise ICE to actual military-standard accountability and training, or reduce visible force to match the agency's actual training and accountability level. The current middle ground is creating problems that will only compound.

Somewhere in there is a more effective immigration enforcement agency—one that achieves its mission with less community friction, fewer legal challenges, and greater operational precision. But it would require the organization to value actual effectiveness over visible toughness. Whether that change happens will determine whether ICE becomes more effective or continues on its current trajectory toward increasing legal exposure, political opposition, and community distrust.

Key Takeaways

- ICE adopted military aesthetics (heavy equipment, tactical formations) without military discipline, training standards, or accountability mechanisms that justify such tactics

- Training duration of 6.5 weeks versus 16+ weeks for military creates judgment gaps typically filled by pop culture, television, and movies rather than scenario-based decision-making

- Tactical formations like doorway stacking and clustering that would be considered suicidal in actual combat are used routinely against non-armed civilians, indicating performance-driven rather than mission-driven operations

- Weapon brandishing and excessive force appearance in situations without active threat violates constitutional proportionality standards and generates civil rights litigation while failing to improve enforcement effectiveness

- Military doctrine from Iraq and Afghanistan demonstrated that escalation creates more resistance and casualties while de-escalation improves outcomes; ICE operates on opposite principles, creating strategic blowback

Related Articles

- Inside Minneapolis ICE Shooting and Protest Response [2025]

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

- Why ICE Masking Remains Legal Despite Public Outcry [2025]

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

- Minnesota ICE Coercion Case: Federal Punishment of Sanctuary Laws [2025]

![ICE's Military Playbook: Why Paramilitary Tactics Fail in Law Enforcement [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-s-military-playbook-why-paramilitary-tactics-fail-in-law/image-1-1769711868102.jpg)