Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement

Last Saturday morning in Minneapolis, federal agents shot and killed Alex Pretti, a 38-year-old nurse who worked at Hennepin Healthcare. Within hours, engineers at Palantir were asking uncomfortable questions on internal Slack channels. Not about the shooting itself, but about their company's role in making it possible.

The killing triggered something that had been simmering for months inside one of Silicon Valley's most powerful defense contractors: a collision between what the company claims its technology does and what workers fear it's actually being used for.

Palantir isn't a household name like Google or Meta. But if you've ever been flagged by immigration enforcement, audited by the IRS, or caught in a dragnet by law enforcement, there's a decent chance Palantir's software had something to do with it. The company builds surveillance and data integration platforms for government agencies. They're really, really good at it. And increasingly, employees are asking whether being good at something means you should be doing it.

This isn't your typical corporate ethics debate. This is about whether a private company should profit from helping the government identify, track, and deport immigrants. It's about whether AI can be deployed humanely, or whether certain applications are inherently harmful no matter how carefully you design them. And it's about what happens when a company's leadership argues they're actually making enforcement more humane by providing better tools, while their own workers don't buy it.

What We Know About Palantir's ICE Work

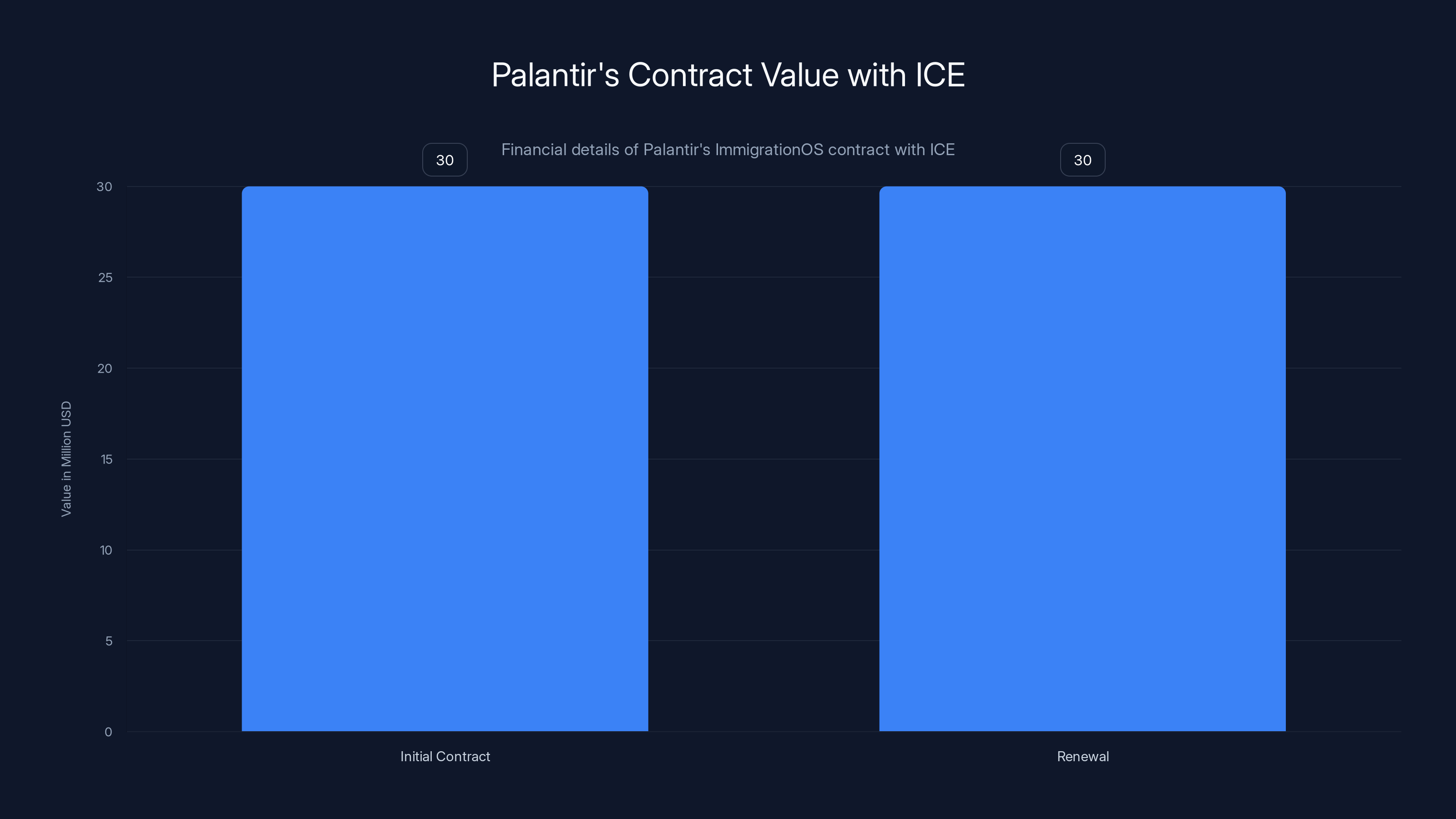

Palantir's involvement with Immigration and Customs Enforcement goes back years, but the details have been deliberately obscure. In April 2025, the company landed a $30 million contract to build something called Immigration OS, a comprehensive platform designed to give ICE what government documents call "near real-time visibility" into immigration enforcement operations.

That's corporate speak for: Palantir built a system that helps ICE agents know where immigrants are, who they are, and what they're doing in real time.

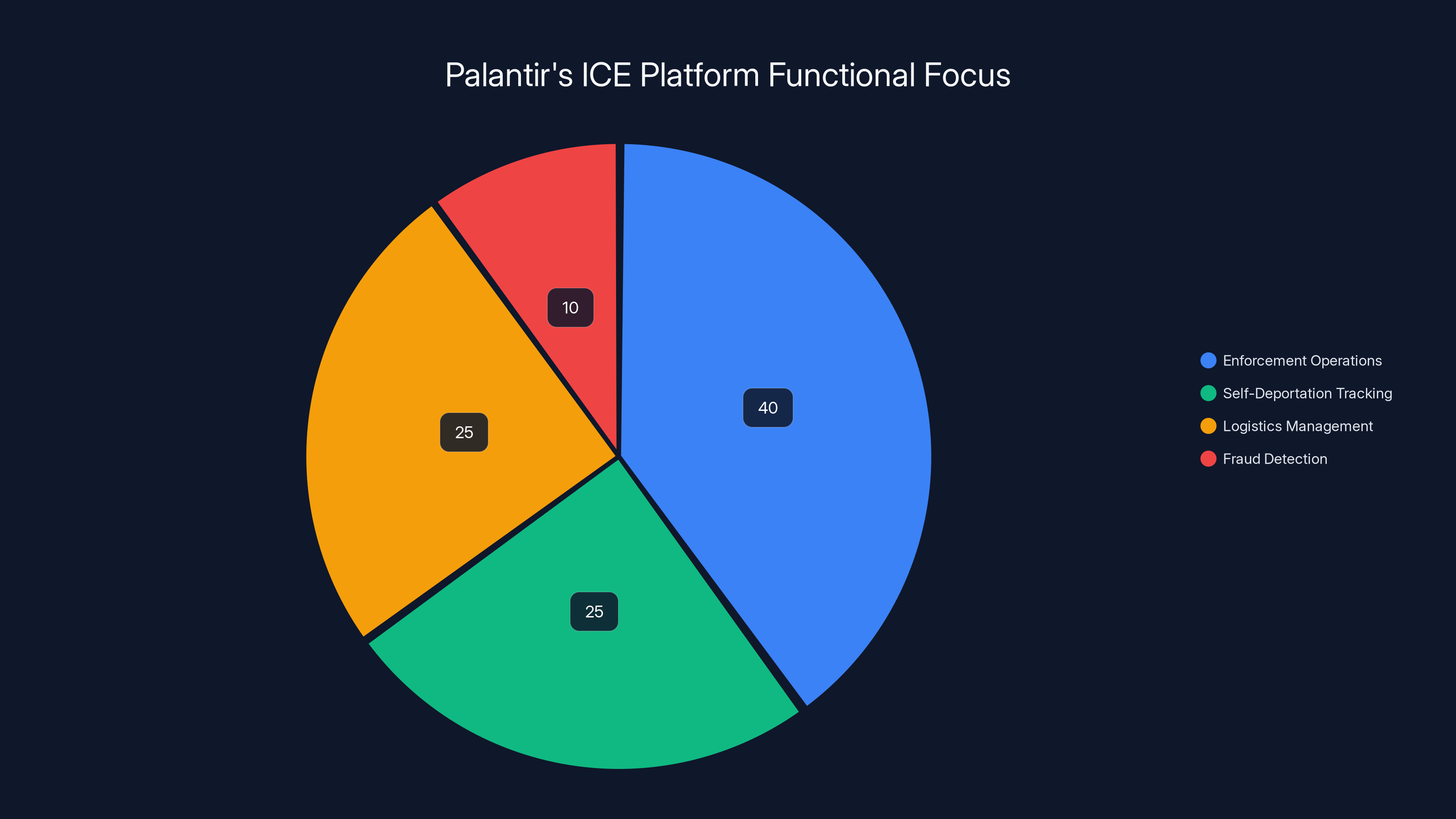

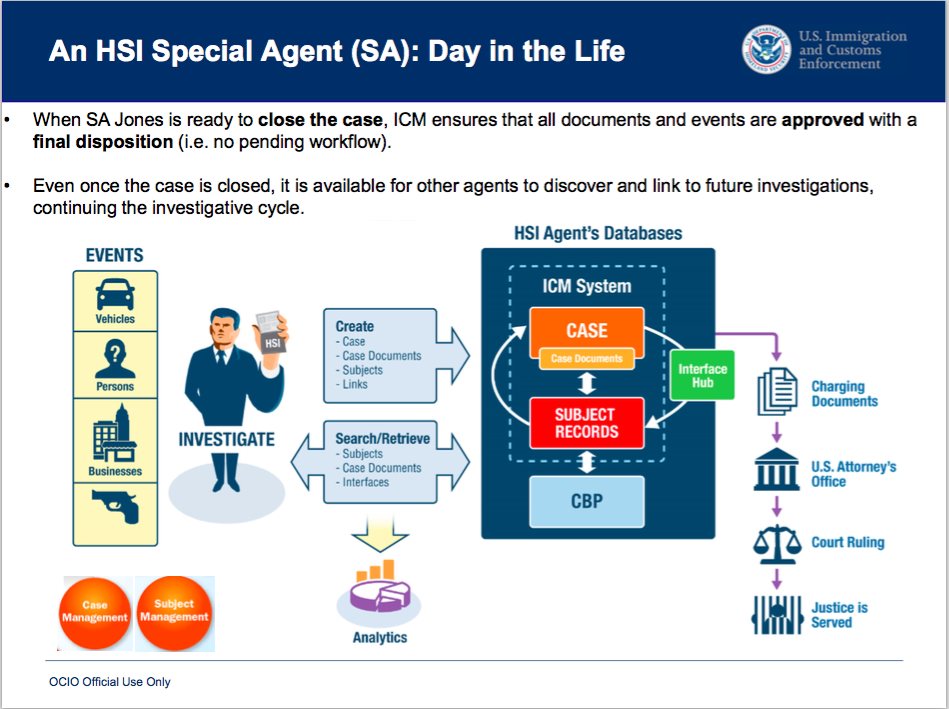

The platform has three main functions. First, "Enforcement Operations Prioritization and Targeting" sounds bureaucratic until you realize what it means: Palantir's system helps ICE decide who to deport. It pulls together data from multiple sources—databases, apps, external records—and identifies people who match whatever criteria ICE is using that week. Second, the system tracks "Self-Deportation," monitoring people who are voluntarily leaving the country to make sure they actually go. Third, the platform handles logistics: scheduling, resource planning, and execution of enforcement operations.

In September, six months into a pilot program, the contract was renewed for another six months. By that point, the self-deportation tracking module had been integrated into the targeting system, making it harder to see where one capability ended and another began.

There's also a separate, newer pilot with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to identify fraudulent benefit submissions. That's smaller, but it sets a precedent: Palantir isn't just working on enforcement operations, it's working across the entire immigration system.

Palantir's contract with ICE for ImmigrationOS is valued at $30 million for the initial phase, with a renewal of the same amount. Estimated data for renewal based on initial contract.

The Problem With "Precision" and "Informed Decisions"

When Palantir's privacy and civil liberties team published their defense of the ICE work on the company's internal wiki, they used language that sounded reasonable on its surface. The technology, they argued, helps ICE make "more precise, informed decisions" and provides "officers and agents with the data to make more informed decisions."

Here's the problem: precision in the wrong direction just means you're wrong more efficiently.

ICE doesn't exist in a vacuum. The agency operates within a political context where immigration enforcement is weaponized. When the Trump administration came into office in 2025, ICE received explicit orders to expand interior enforcement in cities like Minneapolis. Suddenly, the agency had quotas and directives that had nothing to do with public safety and everything to do with visibility and headline-grabbing numbers.

In that context, giving ICE better targeting tools doesn't make enforcement more humane. It makes it more effective at whatever you're telling it to do. If you tell an AI system to prioritize cases with limited family ties, it will do that. If you tell it to focus on a particular neighborhood with a high immigrant population, it will do that. The system doesn't care about fairness. It cares about optimization.

Palantir's own wiki acknowledges this indirectly. It mentions "increasing reporting around U. S. Citizens being swept up in enforcement action and held, as well as reports of racial profiling allegedly applied as pretense for the detention of some U. S. Citizens." The company's response? That ICE "remain committed to avoiding the unlawful/unnecessary targeting." Commitment is nice. Enforcement mechanisms are better.

When one worker asked whether ICE could use Palantir's systems for purposes beyond what's specified in the contract, the answer they got was blunt: Yes. The company doesn't police the usage of its platform. They build "strong controls," but ultimately they're taking the position that bad outcomes are "governed by the law and oversight mechanisms within the system." That's another way of saying, "Not our problem."

The Internal Uprising and What It Reveals

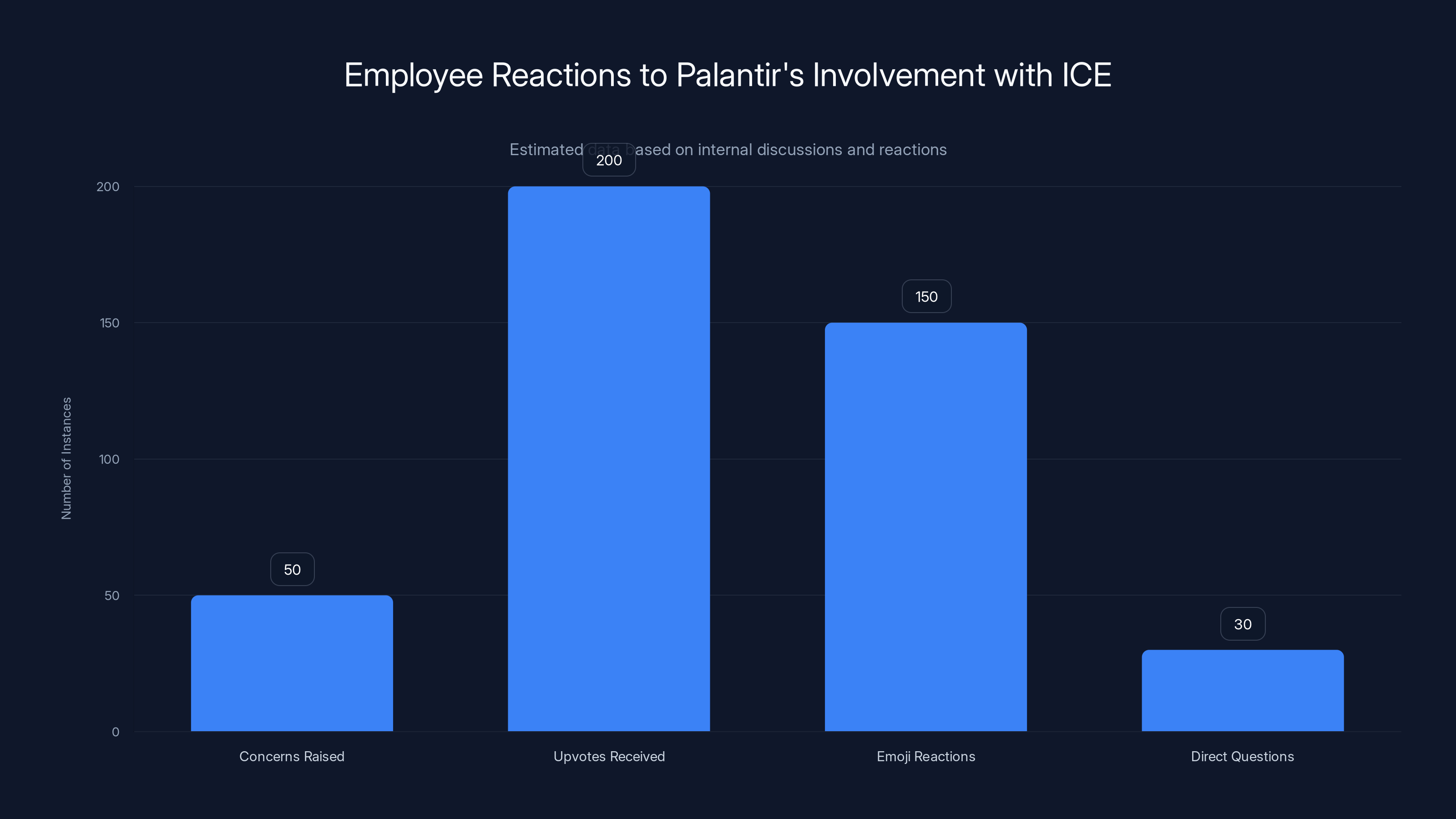

On Saturday afternoon, after the killing in Minneapolis, Palantir's Slack channels lit up. Employees who had been silently uncomfortable for months suddenly started talking. The discussion happened in a company-wide channel meant for news and world events, which made it visible to thousands of workers.

"Our involvement with ice has been internally swept under the rug under Trump 2 too much. We need an understanding of our involvement here," one engineer wrote.

Another asked: "Can Palantir put any pressure on ICE at all?"

A third: "I've read stories of folks rounded up who were seeking asylum with no order to leave the country, no criminal record, and consistently check in with authorities. Literally no reason to be rounded up. Surely we aren't helping do that?"

These weren't fringe employees or junior staff. They were engineers, product people, and people with institutional knowledge. They got dozens of upvotes and emoji reactions from colleagues. This wasn't one person complaining. This was significant internal pressure.

What's telling is what happened next. Courtney Bowman, Palantir's global director of privacy and civil liberties engineering, responded by linking to the company's internal wiki. Not by addressing the concerns directly. Not by announcing policy changes. Just by saying, "Here's what we already told people about this."

It was defensive. It was the corporate equivalent of handing someone a press release instead of having a conversation.

One worker directly asked whether ICE could build its own workflows using Palantir's system to pull data from outside sources. The answer came from Akash Jain, Palantir's CTO for U. S. Government work. "Yes, we do not take the position of policing the use of our platform for every workflow," he said.

Read that again. A company that has built its entire reputation on working with governments is explicitly saying it won't monitor or restrict how those governments use its tools once they're deployed.

Estimated data shows that the primary focus of Palantir's ImmigrationOS platform is on enforcement operations, with significant attention also given to self-deportation tracking and logistics management. Fraud detection is a smaller, yet emerging focus area.

Why This Matters Beyond Palantir

Palantir is just the most visible case of a broader problem: what happens when companies with significant technical capability decide to work with government enforcement agencies?

There are legitimate arguments for why you might do it. If immigration enforcement is going to happen anyway—and it is—maybe you want people inside the system trying to make it less destructive. Maybe you think refusing to work with ICE just means someone else will build them a worse system. Maybe you believe that some government work is more defensible than others.

But there's a fundamental asymmetry here. Once you give a government agency a powerful tool, you lose control of it. You can't decide when it gets used. You can't decide against whom it gets deployed. You can't undo it when politics shift and the agency gets a directive to be more aggressive.

And you definitely can't claim you're making things "more humane" while simultaneously refusing to enforce any limits on how your tool is used.

The employees asking questions inside Palantir seem to understand something the leadership doesn't quite want to admit: there are some applications of AI technology that are difficult to make ethically sound no matter how good your intentions are. Building a system that helps identify and deport people might be one of them.

The Privacy and Civil Liberties Team's Defense

Palantir created a privacy and civil liberties team, which is something. Most defense contractors don't even pretend to have one. The team's wiki post defending the ICE work is genuinely interesting because it shows how a thoughtful person might talk themselves into being comfortable with this work.

The argument goes something like this: the technology is "making a difference in mitigating risks while enabling targeted outcomes." Translation: Palantir's system helps ICE agents make better decisions about whom to prioritize. That's different from arbitrary enforcement. That's discrimination based on intelligence rather than on whims.

Except it's not actually that different. The system still depends entirely on what input you give it. If ICE tells Palantir's system, "Find people without family ties," it will do that. If the directive is, "Focus on neighborhoods with high immigrant populations," it will do that. The system itself is neutral, but the application isn't.

The wiki also argues that Palantir's customers at ICE "remain committed to avoiding the unlawful/unnecessary targeting, apprehension, and detention of U. S. Citizens." Commitment is great. But we have evidence that it's not working. Immigration and enforcement agencies have repeatedly swept up U. S. citizens and permanent residents by mistake. Sometimes for days. Sometimes longer.

Adding better technology doesn't fix broken oversight. It just makes the mistakes faster.

There's also this telling phrase: "We believe that our work could have a real and positive impact on ICE enforcement operations by providing officers and agents with the data to make more precise, informed decisions." Could. Believe. The language is soft, uncertain. But the contract is real. The $30 million is real. The system is in production.

What Happens in a Political Shift

One of the most important things to understand about this situation is that it didn't emerge suddenly. The contract was signed. The work was ongoing. Employees knew about it on some level. But the killing in Minneapolis created a trigger moment.

Political context matters enormously here. In 2024, enforcement operations were one thing. With a new administration in 2025 that had explicitly campaigned on dramatically expanding immigration enforcement, the work took on different meaning. The same tool that might be used for priority-setting suddenly looked like it could be used for dragnet operations.

When political winds shift, government agencies shift with them. And the tools they have shift how they operate. Palantir can't control that. They can try to build in limitations. They can refuse to add certain capabilities. But once the software is deployed, the company has limited leverage.

This is what employees were worried about. Not that the technology was inherently evil. But that it could be used differently depending on who was in charge.

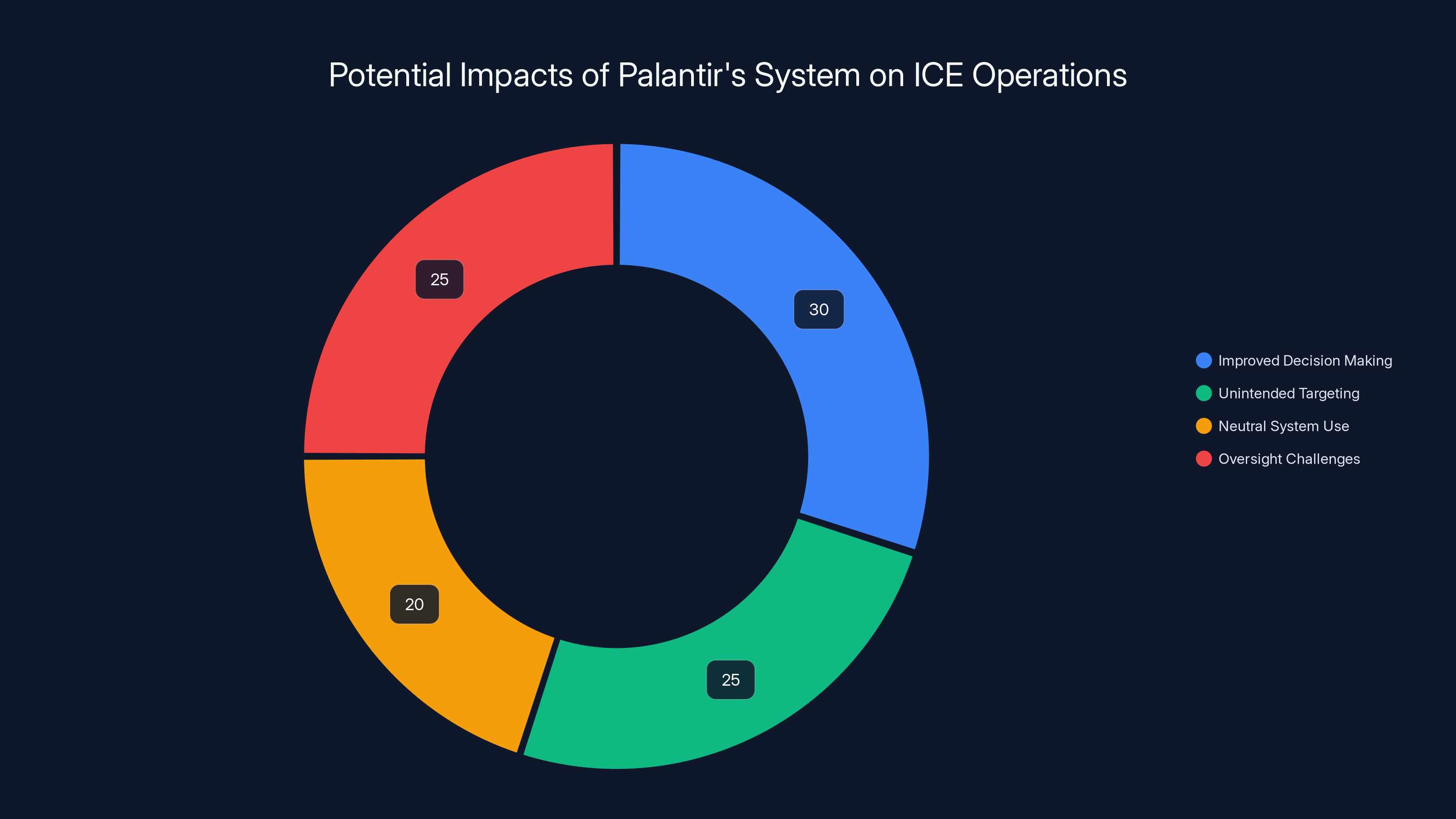

Estimated data suggests that while Palantir's system may improve decision-making (30%), significant challenges remain with unintended targeting (25%) and oversight (25%). Neutral system use accounts for 20%.

The Question of Demand and Supply

There's a classic argument that if Palantir doesn't build this system, someone else will. Someone maybe less thoughtful. Someone without a privacy and civil liberties team. Someone willing to build whatever ICE asks for without pushback.

That argument has some validity. But it's also a bit too convenient. Every defense contractor in the world could justify any project with that logic. "We need to build this surveillance system because if we don't, someone worse will."

At some point, you have to ask: is the limiting principle that you only do things that are better than the worst possible alternative? Or is it that you do things you can feel good about?

Employees at Palantir are clearly struggling with that question. The company's leadership seems to have made peace with the first limiting principle. Build the system. Make it as good as you can. Let oversight mechanisms handle the rest.

That's a defensible position. But it's not obviously the only defensible position. And it's why the internal conversation matters. It suggests that even people inside the organization aren't fully convinced.

The Data Problem: Where ICE Gets Its Information

One detail that didn't get enough attention: Jain said ICE can pull data from "outside sources, whether that be from other agencies or commercially available third-party data."

That's a huge expansion of what the system can do. It's not just about immigration databases. It's about anything. Commercial data brokers sell information about where people go, what they buy, what they search for. If ICE can plug that into Palantir's system, suddenly you're connecting immigration enforcement to consumer behavior.

Imagine ICE can see: this person searched for asylum processes, visited immigration lawyer websites, bought a plane ticket to Miami, and received money transfers from Central America. Is that person now a priority for enforcement? We don't know. We also don't know if there are any oversight mechanisms preventing it.

Commercial data is part of the ecosystem now. Most Americans don't realize how much information about them is available for purchase. When government enforcement agencies get access to that data, combined with government databases, combined with predictive algorithms, you get something genuinely unprecedented in human history: the ability to identify and locate specific populations at scale.

Palantir's system makes that possible at ICE. It's not the only company doing this kind of work. But it's the largest, the most sophisticated, and the most visible.

What Employees Are Actually Worried About

Reading the Slack conversation, the employee concerns cluster around a few themes. First, uncertainty. They don't know what Palantir is actually building. They're finding out from news reports. The company isn't proactively communicating about its government work.

Second, powerlessness. Even after asking for clarification, they don't get meaningful answers. The response is basically: "Here's how we justify it internally. Here's our trust that ICE will use it responsibly."

Third, complicity. One worker wrote, "In my opinion ICE are the bad guys. I am not proud that the company I enjoy so much working for is part of this." That's someone who likes working at Palantir. Who values the work, the people, the mission. But who can't reconcile that with the ICE contract.

That's the real problem Palantir faces. It's not external pressure. It's not activist campaigns. It's people inside the company saying, "I don't want to be part of this." When your engineers and product people feel that way, it becomes a retention problem. It becomes a morale problem. It affects the culture.

And unlike external pressure, which companies can resist or outlast, internal pressure changes how you do business day-to-day.

Estimated data suggests that while precision may increase efficiency and visibility, it may not significantly enhance fairness or public safety. (Estimated data)

The Precedent This Sets

If Palantir keeps growing its immigration work, it sets a precedent for other big tech companies. When the largest data integration platform in the world is comfortable working with enforcement agencies, it normalizes similar work across the industry.

Amazon already sells facial recognition to police departments. Microsoft has raised concerns about law enforcement use of its facial recognition tech but still sells other tools to ICE. Google has walked away from some military contracts but maintains significant government relationships. Meta provides data to law enforcement agencies.

Palantir's ICE work doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a broader ecosystem where government surveillance is increasingly enabled by private companies.

The question isn't whether this technology will exist. It will. The question is whether it will be built thoughtfully, with limitations and oversight, or whether it will be built aggressively with minimal constraints.

Palantir's employees are pushing for the first option. The company's leadership seems to be drifting toward the second.

Why This Matters for Immigration

Immigration policy in America is fundamentally broken. It's incoherent. It's enforced inconsistently. It produces outcomes that nobody—not immigration advocates, not enforcement hawks, not families separated by it—actually wants.

In that broken system, giving enforcement agencies better tools doesn't fix anything. It just makes the broken system more efficient at breaking things.

What's been missing from this conversation is any serious discussion of whether immigration enforcement through deportation is the right approach. Instead, we get debates about whether enforcement should be "humane." Those are different questions.

Palantir's system, no matter how well-designed, doesn't solve that fundamental problem. It just makes it faster.

The Role of Contracts and Government Relationships

Palantir didn't choose to work with ICE because it believed in immigration enforcement as a policy. It chose to work with ICE because ICE has money and Palantir's business model is to sell data integration platforms to government agencies.

That's not nefarious. That's how business works. Companies sell things to governments. Governments use those things for whatever purposes they have.

But it's worth being clear about what's actually happening. Palantir isn't making moral judgments about immigration policy. It's selling tools. That's simpler, in a way. But it's also more troubling, because it means the company isn't taking a position. It's just executing contracts.

The problem is that executing contracts with ICE in 2025 means something specific. It means empowering a particular vision of immigration enforcement. It means the tools exist, deployed at scale, during a period when enforcement is being aggressively expanded.

Timing matters. Contracts signed in different political moments have different meanings.

Estimated data shows significant internal pressure with 50 concerns raised, 200 upvotes, 150 emoji reactions, and 30 direct questions, highlighting employee unrest over Palantir's involvement with ICE.

What Should Palantir Do?

There are a few options. The company could shut down the ICE work entirely. That would be a dramatic statement, but it would also signal that there are some government relationships the company won't pursue.

The company could agree to limit ICE's use of the system to specific purposes. It could require auditing and oversight. It could attach conditions to the contract about how the data can be used.

The company could be radically transparent internally about what it's doing. If employees knew exactly what they were building, if there was a real conversation about ethics rather than a defensive wiki post, it would change the tone.

Or the company could do what it seems to be doing now: accept that some people will be uncomfortable with the work, defend the decision internally as best it can, and wait for the conversation to move on.

Each of those choices has different implications for Palantir's culture, its reputation, and its ability to recruit and retain talented engineers who care about ethics.

The Broader Tech Industry Problem

Palantir isn't unique in working with government enforcement. But it's the most visible case because it's the largest and the most sophisticated. Most tech companies have quietly worked with law enforcement for years. The difference is that Palantir's work is more visible and more comprehensive.

What the Palantir case reveals is that there's growing internal awareness within tech companies that some work is ethically problematic. Employees are asking questions. They're pushing back. They want to know what their companies are doing and why.

That internal pressure is real. It matters. And it's one of the few leverage points that can actually influence how companies behave, because losing talented engineers is expensive.

But it requires sustained pressure. One killing, one moment of viral outrage, isn't usually enough. The conversation fades. People move on. Companies wait for the pressure to pass.

That's where we are with Palantir and ICE. The initial shock is fading. The company has made its statements. The question now is whether the internal pressure will persist or whether it will dissipate.

Lessons for Other Companies and Workers

If you work at a tech company doing government contracts, there are some lessons here. First, you probably don't know exactly what your work is being used for. You think you do. You've read the contract. You've seen the documentation. But in practice, the scope of use always expands.

Second, you have more leverage than you think. Talent is expensive. Morale matters. If enough people are uncomfortable, companies have to respond.

Third, transparency from leadership is possible but requires pushing. Companies will default to defensive positions and internal communications. You have to ask the hard questions explicitly.

Fourth, individual choices matter. You can work somewhere else. You can choose not to work on certain projects. That's not as dramatic as quitting, but it changes the composition of teams and the momentum of projects.

Finally, this is a conversation that needs to happen in more companies, not just Palantir. Every tech company with government contracts should be having this conversation with employees.

Looking Ahead

The Palantir-ICE relationship will probably continue. The contract is signed. The system is in production. The company has defended the work publicly and internally. Walking away from it would be a dramatic reversal.

But the internal conversation that started with Alex Pretti's killing might persist. If enough employees continue to push, if the pressure doesn't fully dissipate, the company might eventually add more constraints or reconsider the scope of work.

Or it might not. Companies can be surprisingly resilient to internal pressure, especially if the financial incentives are strong enough.

What's clear is that the era of tech companies quietly doing government enforcement work without internal scrutiny is over. Employees now expect transparency. They expect conversation. They expect to be able to push back.

Whether companies respond to that expectation or resist it will define what the tech industry looks like over the next few years.

FAQ

What exactly does Palantir's Immigration OS platform do?

Immigration OS is a data integration and analysis platform that gives ICE near real-time visibility into immigration enforcement operations. It has three main functions: helping ICE agents prioritize whom to target for enforcement, tracking people who are voluntarily self-deporting, and handling logistics for enforcement operations like scheduling and resource planning. The system pulls together data from multiple government databases and, according to company officials, can also access data from other agencies and commercial third-party sources.

How much is Palantir being paid for this work?

Palantir secured a $30 million contract with ICE in April 2025 to build and deploy the Immigration OS platform. The initial pilot program was scheduled to run for six months and was renewed in September for an additional six-month period. The company is also running a separate pilot program with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) focused on identifying fraudulent benefit submissions, though the financial terms of that contract aren't publicly disclosed.

Why are Palantir employees upset about this work?

Employees expressed concerns about several issues: lack of transparency from leadership about the scope and nature of the ICE work, worry that the technology is being used to target vulnerable populations despite company assurances, concerns about racial profiling and wrongful detention of U. S. citizens, and fundamental ethical questions about whether immigration enforcement through deportation is something the company should be supporting. One employee stated directly, "In my opinion ICE are the bad guys. I am not proud that the company I enjoy so much working for is part of this."

What controls does Palantir claim to have built into the system to prevent misuse?

Palantir's privacy and civil liberties team posted an internal statement saying the company has built "strong controls" into the system and trusts that ICE leadership "remain committed to avoiding the unlawful/unnecessary targeting, apprehension, and detention of U. S. Citizens." However, when directly asked whether ICE could use the platform beyond the scope of the contract, company CTO Akash Jain confirmed that ICE can build custom workflows and pull data from outside sources. He stated, "We do not take the position of policing the use of our platform for every workflow."

Could this work be used to target immigrants who are legally in the country or seeking asylum?

Theoretically yes. The system can integrate data from multiple sources, including commercial data brokers. In principle, it could identify people based on search history, financial transactions, location data, or other factors suggesting immigration status or asylum-seeking behavior. While ICE officials claim commitment to avoiding wrongful targeting, the system itself doesn't appear to have built-in enforcement mechanisms preventing such uses. Several Palantir employees pointed to news reports of asylum seekers with no criminal records being arrested, questioning whether the company's tools were being used in those operations.

Why doesn't Palantir just refuse to work with ICE?

Palantir's leadership would argue that ICE will get these capabilities from someone regardless, and a company with Palantir's ethics-focused approach is preferable to competitors without such considerations. Additionally, government contracts are a significant revenue stream for the company. The ICE work is part of broader Department of Homeland Security contracts that also include work with U. S. Citizenship and Immigration Services and other agencies. Walking away from all ICE work would require turning down significant revenue.

What does Palantir's privacy and civil liberties team actually do?

The team, led by Courtney Bowman as global director of privacy and civil liberties engineering, appears to function as an internal advocacy and policy group. They review government contracts for civil liberties implications and publish internal documentation defending work the company has decided to pursue. However, their role seems to be advisory rather than veto-power-holding. When employees raised concerns about the ICE work, the team's response was to link to an internal wiki post defending the work, rather than to announce policy changes or announce additional constraints.

How is this situation different from other tech companies working with government agencies?

While several major tech companies work with government enforcement agencies (Amazon sells facial recognition to police, Microsoft and Google have government contracts), Palantir's work is distinctive because the company's entire business model is built around government data integration work. For Palantir, government contracts aren't a side business—they're the core business. This means that moral concerns about particular government work affect the company's fundamental identity in a way they might not for companies with more diversified revenue streams.

Conclusion

The killing of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis exposed something that had been silently building inside Palantir: a growing gap between what the company's leadership believes about its work and what employees actually believe. That gap didn't emerge because of one incident. It emerged because the company has built itself into an essential part of government enforcement infrastructure without fully reckoning with the implications.

Palantir's defense of its ICE work rests on a few claims. The technology makes enforcement more "precise" and "informed." The company has built safeguards. ICE remains committed to avoiding unlawful detention. Oversight mechanisms will catch problems.

Each of those claims has some merit. None of them are sufficient.

Precision without constraint just means you're wrong more efficiently. Safeguards matter only if they're enforced. Commitment changes with administrations and political winds. And oversight mechanisms have repeatedly failed to prevent immigration agencies from wrongfully detaining U. S. citizens and permanent residents.

The real question isn't whether Palantir's technology works. It does. The question is whether it should. And whether a company that employs talented engineers who care deeply about ethics can continue to build systems that optimize for government enforcement objectives without eventually confronting the fundamental contradiction.

For now, Palantir appears to be holding firm. The contract stands. The system is deployed. The company has made its case internally. But the conversation that started with Alex Pretti's killing might not fully go away. Employees now know what the company is doing. They're uncomfortable with it. They've asked direct questions and gotten defensive responses.

That's not a situation that typically resolves itself quietly. Either Palantir will eventually change course, adding constraints and transparency. Or the discomfort will persist as a drag on company culture, affecting recruitment and retention of the kind of thoughtful engineers the company needs to stay competitive.

What's certain is that the era when tech companies could quietly do government enforcement work without internal scrutiny has ended. Employees expect transparency. They expect to be consulted. They expect that their moral concerns will be taken seriously.

For Palantir, and for every other tech company working on government contracts, that expectation is now permanent. How they respond to it will define what kind of companies they become.

Key Takeaways

- Palantir secured a $30 million contract with ICE in April 2025 to build ImmigrationOS, a platform giving the agency real-time visibility into enforcement operations across targeting, tracking, and logistics

- Internal Slack conversations following a fatal immigration enforcement incident in Minneapolis revealed significant employee concern about the ethical implications of the company's government work

- The company's privacy and civil liberties team defended the work as improving 'precision' in enforcement decisions, but acknowledged it cannot police how ICE uses the platform beyond contract terms

- Key concern: Palantir's system can integrate data from commercial brokers and external agencies, potentially enabling enforcement at scale that exceeds original contract scope

- Employee pushback signals broader tech industry trend of workers expecting transparency and ethical oversight of government contracts, with implications for recruitment and company culture

Related Articles

- Tech Workers Demand CEO Action on ICE: Corporate Accountability in Crisis [2025]

- How Reddit's Communities Became a Force Against ICE [2025]

- ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]

- TikTok Data Center Outage Sparks Censorship Fears: What Really Happened [2025]

- AI Drafting Government Safety Rules: Why It's Dangerous [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

![Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/palantir-s-ice-contract-the-ethics-of-ai-in-immigration-enfo/image-1-1769467077108.jpg)