Introduction: When Platforms Become Gatekeepers

It happened quietly, then all at once. Users sharing links to ICE List on Facebook and Threads started seeing error messages. The links wouldn't load. Posts got flagged as spam. And suddenly, a public database of government employees became unreachable on the world's largest social network.

This wasn't a hack. It wasn't a government order (at least, not publicly). Meta—the company that owns Facebook, Threads, Instagram, and WhatsApp—made a deliberate choice to block access to a specific website. That website, ICE List, is a crowdsourced wiki that compiles information about immigration enforcement actions and lists the names of thousands of employees working for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and other Department of Homeland Security (DHS) agencies.

On the surface, this looks like a straightforward content moderation decision. Meta has Community Guidelines. The company enforces them. Case closed.

But dig deeper, and you hit uncomfortable questions that don't have clean answers. Who decides what information should be accessible? When does protecting people's privacy become censoring public information? What's the difference between a leaked database and aggregated public records? And how much power should one company have to determine what billions of people can see?

The story of ICE List and Meta's response reveals something fundamental about how modern information flows. It's not about government censorship anymore. It's about private companies making decisions that reshape what we can access, who gets identified, and what counts as protected speech in the digital public square.

This article digs into what happened, why Meta took action, what the ICE List actually contains, the competing interests at stake, and what this moment tells us about the future of platform governance, privacy, and accountability in 2025.

TL; DR

- Meta's Action: Facebook and Threads now block links to ICE List, a crowdsourced wiki listing thousands of government agents' names and immigration enforcement details

- The Trigger: Meta cited Community Guidelines violations, specifically spam flagging, after the site went viral claiming to host a leaked 4,500-person employee database

- Reality Check: Analysis revealed the list relies heavily on publicly available LinkedIn profiles, not actual leaked data

- The Tension: Free speech advocates argue this is censorship; privacy advocates worry about employee safety and harassment risks

- Bottom Line: This reflects a broader shift where tech platforms, not governments, control access to information in the digital era

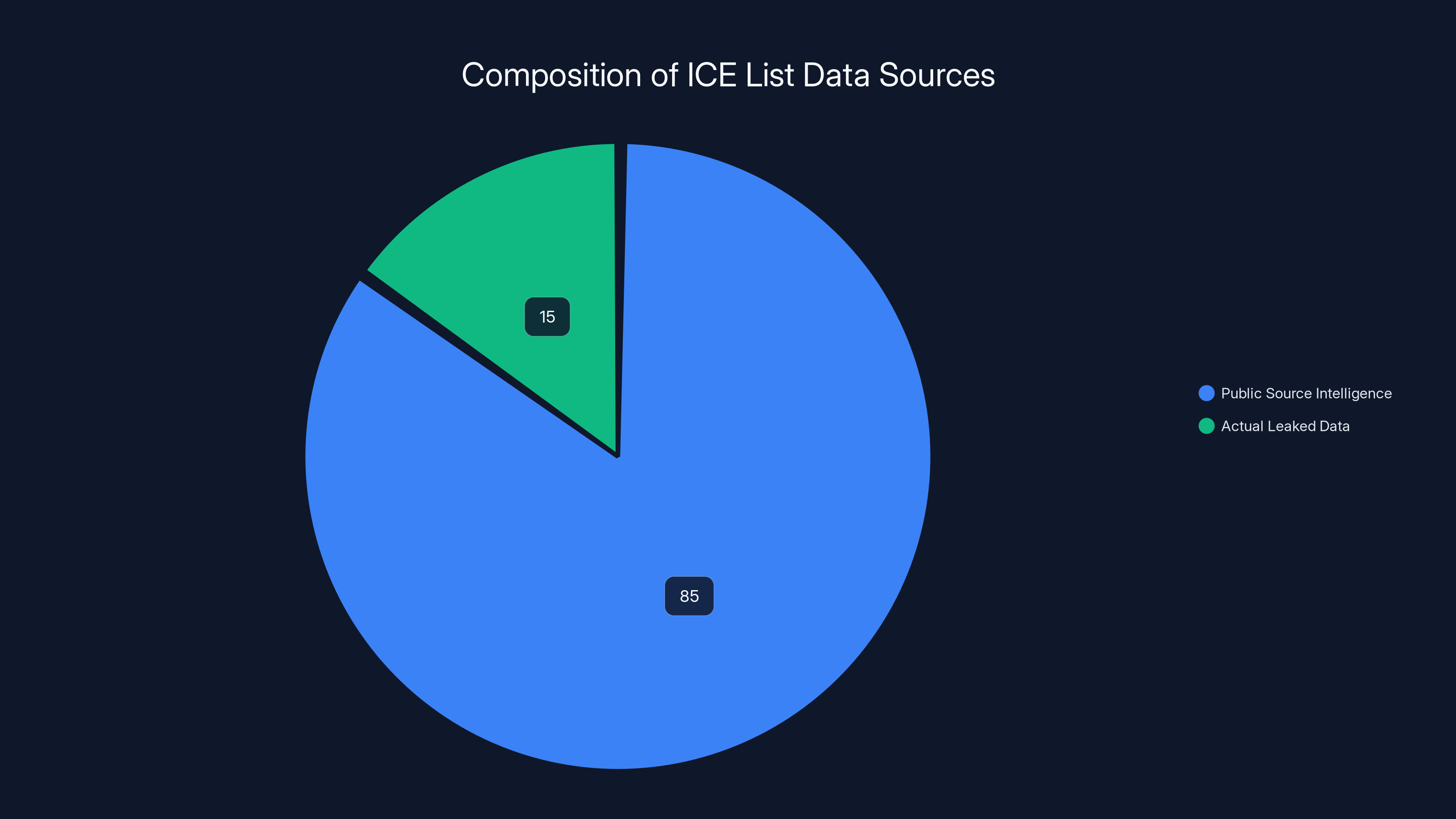

Estimated data suggests that 85% of the ICE List's information came from public sources like LinkedIn, while only 15% was from actual leaks. This distinction alters the perception of the data's sensitivity.

What Is ICE List? Understanding the Database

ICE List presents itself as "an independently maintained public documentation project focused on immigration-enforcement activity." That's the elevator pitch. But what does it actually do?

The site compiles information about immigration enforcement actions, incidents involving ICE and Border Patrol agents, details about detention facilities, vehicle information, and names of individual employees. It's a wiki, meaning it's crowdsourced—anyone can theoretically contribute, edit, and verify information.

The database is organized by category. You can search for specific agents by name, look up incidents by location, find information about detention facilities, or review enforcement actions by date. For someone researching immigration policy or tracking specific enforcement patterns, it's a researcher's tool. For someone with a grudge against a particular agent, it's a targeting list.

Here's where it gets complicated: ICE List claims to aggregate information from multiple sources, including what it describes as leaked DHS data. When the site went viral in early 2024, it announced that it had uploaded a list of 4,500 DHS employees. That's when alarm bells started ringing.

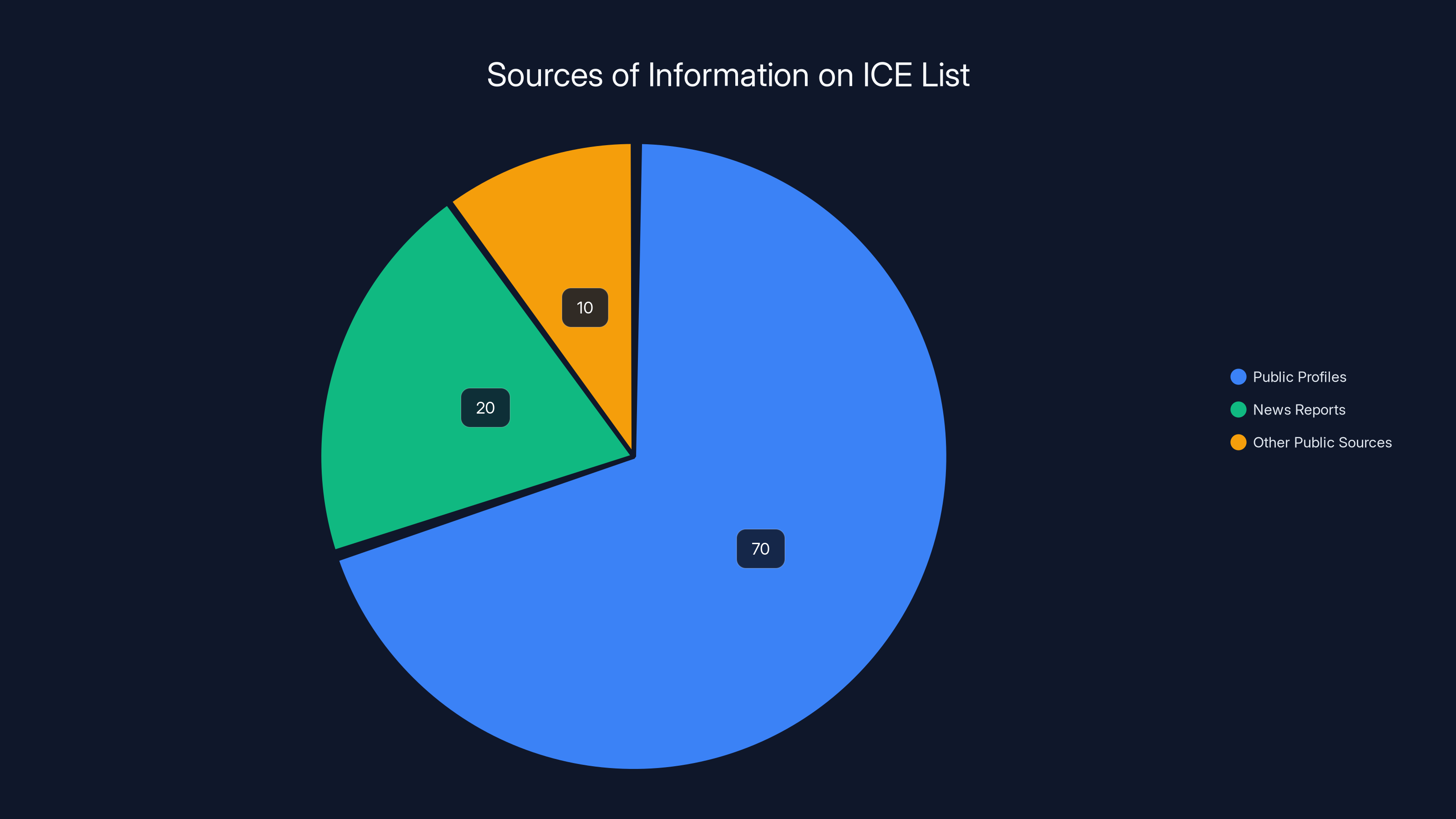

But investigative analysis found something revealing. The database wasn't primarily built from classified leaks. Instead, most of the information came from public sources—specifically, LinkedIn profiles where government employees had listed their jobs, locations, and agency affiliations. People voluntarily shared this information publicly. ICE List simply collected, organized, and centralized it.

That distinction matters enormously for how we evaluate what Meta did. We're not talking about stolen classified documents or breached confidential records. We're talking about aggregating and indexing information people shared openly, then making that aggregated index searchable and findable.

Why ICE List Went Viral: The Timing and Context

ICE List didn't explode in popularity because it was brand new. The project had existed for some time, maintained by immigration activists and researchers. But in early 2024, something changed. The site made headlines, went viral on social media, and suddenly became impossible to avoid in certain communities.

The timing wasn't random. Immigration enforcement was (and remains) a contentious political issue. Activist communities were searching for ways to track and document enforcement patterns they viewed as unjust. Simultaneously, concerns about government overreach and surveillance were at a peak. ICE List positioned itself as a tool for accountability—a way to document who was making enforcement decisions and where they were operating.

For many users, sharing ICE List links felt like activism. It was a way to say, "This is happening, here are the people doing it, and nobody can ignore it anymore." The emotional resonance was powerful, particularly in immigrant communities and among immigrant rights advocates.

But the viral moment also triggered concern. Parents of government employees started getting worried. Law enforcement groups raised concerns about safety. And media coverage shifted the narrative from "tracking enforcement patterns" to "targeting government workers."

Meta was watching. The platform had already faced pressure from various groups about immigration enforcement content. And now, links to a site explicitly naming thousands of government employees were spreading rapidly across their platforms.

The majority of the information on ICE List is derived from public profiles, particularly LinkedIn, accounting for 70% of the data. Estimated data.

Meta's Content Moderation Framework: How Decisions Get Made

Meta didn't wake up one morning and decide to block ICE List on a whim. The company operates a massive content moderation system that processes millions of flagged items daily. Understanding how that system works—and where it failed or succeeded in this case—requires looking under the hood.

Meta's Community Guidelines cover eighteen categories of prohibited content. Several could potentially apply to ICE List links: violence and incitement, dangerous individuals and organizations, targeted harassment, and spam. The error message that appeared when users tried to share ICE List links specifically cited spam flagging.

Spam is Meta's catchall category for content that artificially manipulates the platform—fake engagement, repetitive posts, artificial trending, that kind of thing. But ICE List links weren't being shared as spam. They were being shared as actual resources. Using spam rules to block them felt like a hammer to hang a picture.

Meta's content moderation doesn't rely on humans reading everything. The company uses machine learning models trained to detect suspicious patterns. These models flag potential violations, which then get reviewed by human moderators. Those moderators follow a set of guidelines to decide whether content should be removed, restricted, or allowed.

The problem: machine learning models are terrible at nuance. They see a URL being shared thousands of times in a short period and flag it as spam-like behavior, without understanding the content itself. They see "government employee names" and might flag it as potential harassment. They see organized patterns and assume manipulation.

Meta's system is efficient but blunt. And when a site goes viral for the "wrong" reasons, automated systems tend to overcorrect.

What makes this case particularly interesting is what Meta didn't do. The company didn't take down the site itself (it can't—the site isn't hosted on Meta's servers). It didn't go after the creators legally (too risky, too much bad press). Instead, it simply made the site unreachable through its platforms by blocking links and flagging shares. It's a middle path: not quite censorship, not quite tolerance. Just... unavailability.

The Privacy and Safety Argument: Who Gets Protected?

Why did Meta act? The official answer points to privacy and safety concerns. And there's a real argument there.

Government employees doing enforcement work don't necessarily consent to having their names aggregated into a searchable database. While their LinkedIn profiles are public, the aggregation and presentation is different. A scattered public profile here, another there, doesn't pose the same risk as a centralized, indexed database where you can search for "ICE agents in Denver" or "CBP officers in El Paso."

Once someone's name is in that searchable database, the risk profile changes. Activists might organize protests at their homes. Extremists might target them for violence. Former detainees might seek revenge. Even if no one does anything, the psychological effect of knowing you're publicly listed as a government enforcer in an immigration detention system can be significant.

There's also the reality of how such databases get used. While ICE List frames itself as an accountability tool, critics argue it functions as a targeting list. And looking at actual security incidents, that concern isn't theoretical. Government employees have been targeted, harassed, and threatened because of public identification.

Meta's content policy explicitly prohibits content that could lead to violence or harassment of individuals, even if that person is a public figure or government employee. From that lens, blocking links to a database explicitly designed to identify individuals seems reasonable. The company isn't saying the information is false. It's saying the aggregation and indexing for potential targeting purposes violates their policies.

But here's where it gets complicated. Privacy and safety arguments can justify almost anything. Every piece of information, if weaponized, could hurt someone. Every aggregation of public data could theoretically enable harassment. If Meta takes privacy and safety seriously as blocking criteria, should they also block:

- Business directories that list corporate executives?

- Alumni networks that compile contact information?

- County records that list property owners by address?

- News articles that name police officers involved in controversial incidents?

The consistency question matters. If ICE List employees deserve privacy protection, what about other categories of workers in high-stress, potentially dangerous jobs?

The Free Speech Counterargument: Who Decides What's Accessible?

Free speech advocates looked at Meta's action and saw something troubling: a private company unilaterally deciding that certain information shouldn't be accessible on its platform.

The First Amendment doesn't protect you from Facebook or Twitter censoring you. Those companies are private, not government actors. So legally, Meta has the right to block whatever it wants. But that legal right doesn't answer the practical question: is it good?

ICE List defenders make several arguments. First, the information is entirely public. Nothing in the database comes from classified or hacked sources (despite initial claims). It's aggregated from public profiles, public records, and news articles. If the information is public, they argue, it should be citable and shareable.

Second, government employees—especially those involved in enforcement—have different privacy expectations than private citizens. They're functioning in official capacities, exercising government power. Knowing who's making enforcement decisions is a component of democratic accountability. You should be able to know which agents are responsible for enforcement actions in your area.

Third, the safety concern cuts both ways. Immigration advocates argue that ICE agents have harassed, injured, and separated families without accountability. From their perspective, identifying the people responsible for those actions is accountability, not harassment. The database enables oversight.

Finally, there's the precedent question. If Meta can block links to ICE List because of potential harassment risks, what stops them from blocking other databases? Police officer directories? Abortion clinic locations? Political donor information? Once you accept that platforms can block information for safety reasons, where does that authority stop?

Free speech advocates worry that "safety" becomes a justification for suppressing any information some group finds inconvenient. Government might not be the censor directly, but Meta becomes the censor by proxy.

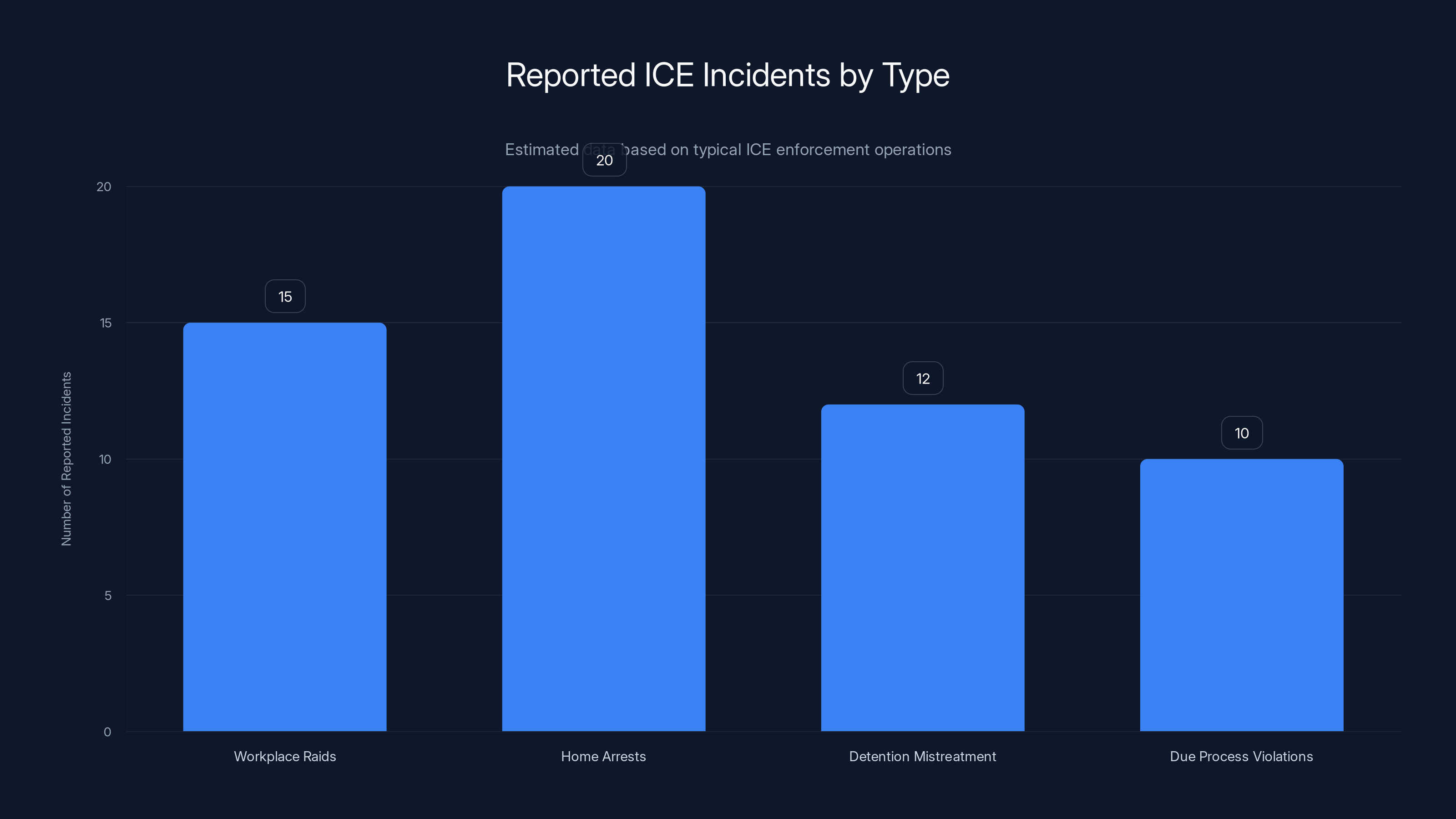

Estimated data shows workplace raids and home arrests are the most frequently reported ICE incidents, highlighting areas for potential oversight and reform.

The Leaked vs. Public Data Distinction: What Actually Happened

One of the most important facts in this entire story got buried beneath the larger narrative: ICE List didn't actually release leaked data. Or more precisely, the "leaked" component was much smaller and less dramatic than initially claimed.

When ICE List announced it had uploaded a "leaked list of 4,500 DHS employees," that announcement drove the viral moment. It sounded like a major breach. Journalists reported it as a leak. And suddenly, Meta was facing pressure to address what looked like stolen confidential information.

But investigative analysis found that the 4,500 names were not from a single leak. Instead, ICE List had compiled the list through what researchers call "public source intelligence"—basically, systematic searching and aggregation of publicly available information. The primary source was LinkedIn, where DHS employees had voluntarily listed their employment, job titles, office locations, and sometimes biographical details.

Some information may have come from actual leaked databases. The site referenced a leak at one point, though specifics were never provided. But the bulk of the database came from manual aggregation of public sources.

This distinction matters because it changes the framing. If Meta was blocking links to a database built from stolen classified information, that's a much more defensible decision. The company would be preventing the distribution of breached sensitive material.

But if Meta is blocking links to a database built from public information, the decision looks different. The company would be saying: "You can't aggregate and index public information on our platform, even if that information is freely available everywhere else."

The irony is that ICE List's marketing got caught in its own narrative. By claiming it had released "leaked" data, it attracted attention and credibility. But when actual analysis showed the leak narrative was overstated, it undermined the project's trustworthiness without necessarily making it less important as an accountability tool.

Platform Moderation at Scale: Why Nuance Breaks Down

Meta moderates billions of pieces of content daily. That number isn't hyperbolic. Facebook alone has over 3 billion users. Instagram has 2 billion. Threads is smaller but growing. The scale is genuinely incomprehensible.

At that scale, nuance becomes impossible. Meta can't hire enough humans to carefully review every piece of content and make case-by-case judgments. The company uses machine learning models to flag potentially problematic content, then human moderators review flagged items based on decision trees—essentially, flowcharts that guide how to classify different types of content.

Those decision trees work great for obvious cases: child exploitation, direct threats, promotion of terrorism. But they fail spectacularly for edge cases like ICE List. The system sees:

- A URL being shared thousands of times rapidly (automated spam flags)

- Content involving government employee identification (potential harassment flags)

- Organized sharing patterns (coordination flags)

- Keyword matches for "names," "database," "tracking" (algorithmic triggers)

And it flags everything as problematic.

The human reviewers then follow their guidelines. Do those guidelines have a specific instruction for "aggregated public databases of government employees"? Probably not. So the reviewer uses the closest match: spam, harassment, or maybe dangerous individuals/organizations. The content gets removed or restricted.

Once a link gets flagged enough times, it enters a different category: a site-wide blocking list. Facebook's algorithms now recognize ICE List's domain and treat any links to it as suspect. The blocking happens automatically, at scale, without individual human review.

This is what happens when you automate judgment at billion-user scale. You sacrifice precision for speed. You accept that some things will be blocked incorrectly because getting most things right matters more than perfecting edge cases.

But from the user's perspective, it doesn't feel like a machine learning limitation. It feels like Meta is deliberately suppressing information. And that perception matters, even if the reality is slightly different.

Incidents Involving ICE Enforcement: Why the Database Exists

To understand why people built ICE List in the first place, you need to understand what "ICE incidents" actually means.

ICE agents conduct enforcement operations: raids on workplaces, arrests at homes, detention in facilities spread across the country. These operations sometimes involve violence, injuries, deaths. Sometimes they involve due process violations. Sometimes they target people with no criminal history.

The problem, from an accountability perspective, is that these incidents are often undocumented or scattered. A family experiences a traumatic raid. They report it to immigrant advocacy organizations. The incident gets noted but isn't systematized. The same agent might conduct ten similar operations over a year, but there's no way to know without talking to affected communities directly.

ICE List's creators wanted to change that. By creating a centralized database of incidents, they aimed to show patterns. "This agent has been involved in fifteen workplace raids in the past year." "This facility has had twelve reported incidents of mistreatment." "This detention center has had the highest mortality rate in the ICE system."

Those patterns matter for oversight. If an individual agent is consistently involved in incidents where rights are violated, that's information the public should have. If a particular facility has a systemic pattern of abuse, people should know before their loved ones are detained there.

From a civil rights perspective, documentation through aggregation is powerful. It transforms scattered, isolated complaints into a visible pattern that's harder to ignore.

But aggregation also enables targeting. Once you have a centralized database of agents, it's easy to organize protests outside their homes, contact their family members, or worse. The same tool that enables accountability oversight can enable harassment.

This is the core tension: the same feature that makes ICE List valuable for civil rights documentation makes it concerning for employee safety. You can't separate them. You have to weigh which matters more.

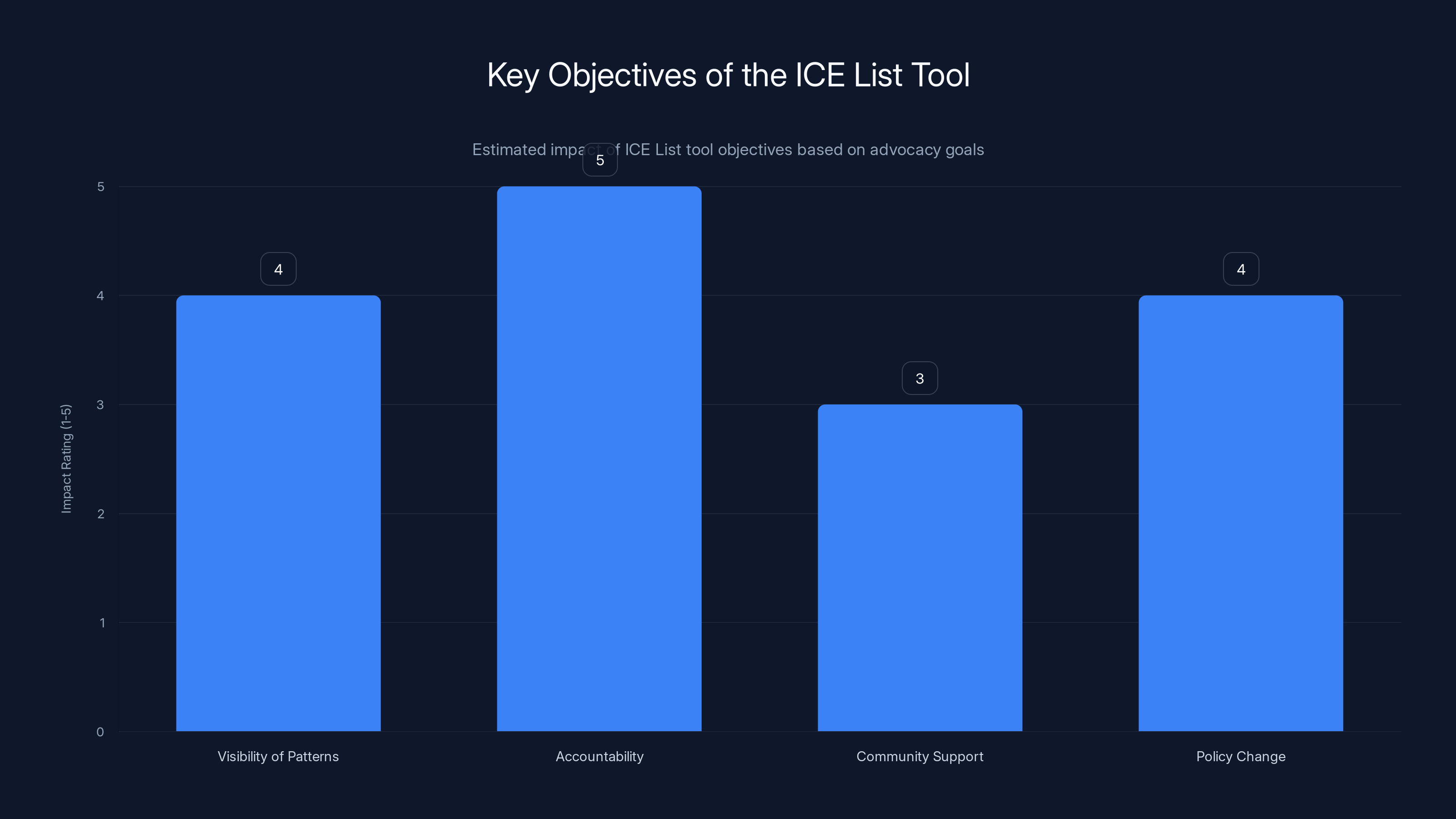

The ICE List tool aims to enhance visibility of enforcement patterns, improve accountability, support communities, and drive policy change. Estimated data based on advocacy goals.

Historical Context: Prior Content Moderation Decisions on Immigration

Meta's decision on ICE List didn't happen in a vacuum. The company had already taken action on immigration-related content before.

Most notably, Meta removed a Facebook group that tracked ICE sightings in Chicago. The group served a specific, practical purpose: posting real-time information about ICE operations in the area so people could alert community members to danger. It was a crowdsourced warning system.

But the Justice Department pressured Meta to remove it, arguing that the group was hampering enforcement operations by providing real-time warnings. Meta complied. The group disappeared.

That precedent matters. It shows that Meta is willing to restrict immigration-related information under pressure. And it suggests that government agencies—while not directly controlling Meta—can influence the company's content decisions through official channels.

The question becomes: Is Meta responding to genuine safety concerns, or is it being pressured to suppress content that makes enforcement harder?

There's also the pattern of how Meta has handled other controversial databases. The company didn't block Zillow's public database of property values, even though that information could theoretically enable burglary targeting of wealthy homeowners. It didn't block LinkedIn, despite the fact that criminals can use it to identify targets. It didn't block Google Maps, which shows locations of police stations.

Why is ICE List different? Is it because of unique safety concerns? Or is it because the database explicitly involves government employees in a controversial agency during a time when immigration enforcement is politically polarized?

The consistency question keeps coming back. If Meta applies its safety and privacy standards evenly, ICE List shouldn't be special. If it's being treated specially, the reasons should be transparent.

The Role of LinkedIn: Where Most Names Actually Come From

Most ICE List data came from LinkedIn. That's worth dwelling on because it highlights a strange disconnect in how we think about information privacy.

LinkedIn is a public network. It's designed for professional networking. People post their job titles, employers, office locations, and career history explicitly to be visible and searchable. When a DHS employee lists themselves as "ICE Agent, Denver Field Office" on LinkedIn, they're doing exactly what the platform is designed for: making their professional information public.

ICE List essentially did what LinkedIn's search function already allows you to do: filter by employer and location. The difference is that ICE List did it at scale, systematically, and created a curated list.

So here's the irony: the information that makes ICE List possible is information that was explicitly made public by the employees themselves. They posted it. They shared it. They wanted to be findable on LinkedIn.

The problem is aggregation and presentation. LinkedIn's search function is scattered. You have to actively search "Immigration and Customs Enforcement" and filter by location to find agents. ICE List puts them all in one place, already organized.

That aggregation adds risk. A person whose LinkedIn profile is public might not realize they're participating in an indexed database. They posted their job title without thinking about how it could be compiled and used.

This is actually a broader problem with information privacy in the age of aggregation. Individual data points seem harmless. But when aggregated, they create visibility that people didn't explicitly consent to. You consented to your info being on LinkedIn, not to it being harvested and indexed into a targeting database.

But that logic could justify blocking all kinds of aggregation. Google's search function is technically aggregation of public information. Should Meta block Google search results? Should YouTube block videos that mention government employees by name?

The answer probably depends on intent and application. A database designed to track enforcement patterns for civil rights documentation is different from a database designed to enable stalking. But the technical implementation is identical. The only difference is how people use it.

Border Patrol and CBP: Different Agency, Same Concerns

ICE List actually targets multiple agencies, not just ICE. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents are also listed. The list includes Border Patrol officers, port-of-entry inspectors, and other CBP employees.

That expansion is important because it changes some of the calculus. Border Patrol operates at the U.S. border, often in remote or tense environments. Officers face threats from smugglers and cartels. Making their identities public could create safety risks that are genuinely different from domestic ICE agents.

Additionally, Border Patrol doesn't have the same public accountability concerns. While ICE conducts interior enforcement and detention operations that affect millions of people annually, Border Patrol's primary job is border security at defined locations. The incentive to document their operations for civil rights purposes is lower.

Including Border Patrol agents in the same database as ICE agents could actually muddy the original accountability mission. It turns a focused civil rights documentation project into a more general government employee tracking database. And that broader database has fewer clear justifications.

When Meta made its blocking decision, it might have been thinking about Border Patrol safety as much as ICE accountability concerns. But the blocking applies to the entire site, not just Border Patrol agents. ICE List creators get blocked even for sharing information narrowly focused on domestic enforcement.

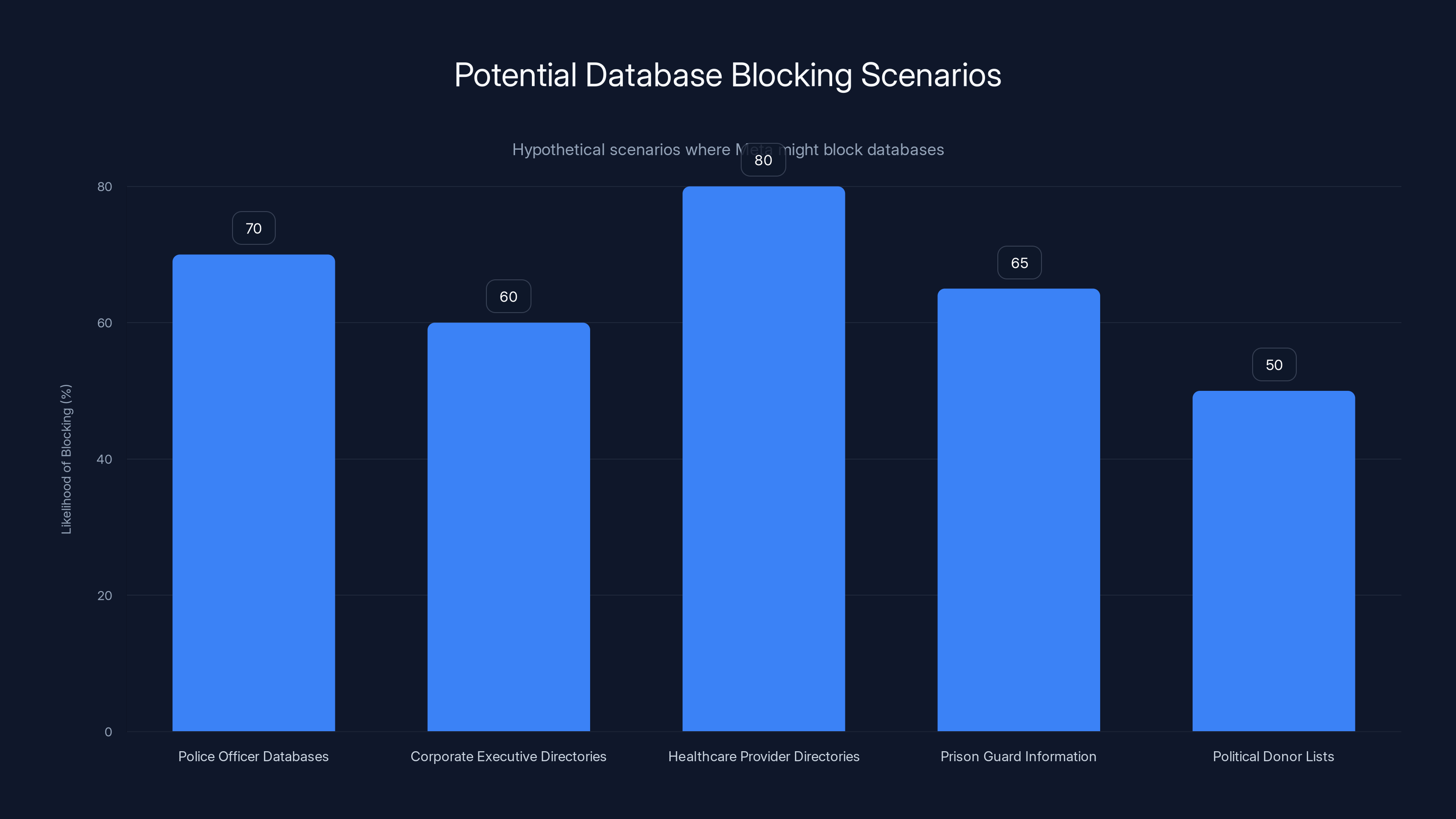

Estimated likelihood of Meta blocking various databases due to safety concerns. The precedent set by blocking the ICE List could influence future decisions.

The Harassment Risk: Concrete Examples and Patterns

Let's be concrete about the harassment risk. It's not hypothetical.

Government employees in controversial positions—and ICE certainly qualifies—have been targeted for harassment, doxxing, and worse. People find their home addresses online, show up at their houses, contact their family members, post their information to encourage others to do the same. In extreme cases, it escalates to violence.

Immigrant rights activists have employed targeted campaigns against specific agents before. They've published information online, organized coordinated social media campaigns, and encouraged others to contact these individuals. Most of the time this stays in legal territory (protest, speech, contact). But it creates an atmosphere where personal safety becomes a genuine concern.

From a government employee's perspective, being in an indexed database feels different than being identifiable through scattered public sources. It feels targeted. It feels like you've been put on a list.

The psychological impact matters. An ICE agent knowing they're in a database designed to track them might become more cautious—which civil rights advocates would say is good, a form of accountability. Or they might become more defensive, less willing to engage with concerns, more likely to see everything as a threat. The agent's family members might face harassment, which is indisputably bad.

Meta's decision makes sense if you prioritize employee safety. It's harder to justify if you prioritize civil rights accountability. The company couldn't have it both ways, so it chose safety (or claimed to, anyway).

What Meta Actually Said (and Didn't Say)

Meta's official position on ICE List is notably sparse. The company didn't issue a lengthy statement explaining its reasoning. It didn't publish a policy blog post walking through the decision. Instead, users who tried to share links saw error messages.

The error message said posts that look like spam are blocked. It didn't mention safety concerns, harassment, targeting, or the specific content of ICE List. It didn't distinguish between actual spam and a database that might enable harassment. It just said: spam.

That reveals something about how Meta operates. When the company makes controversial moderation decisions, it often hides behind generic policy language. "Community Guidelines violation" is vague enough to cover almost anything. Users see that their post was removed but don't know exactly why, and they can't effectively argue against a vague citation.

Compare that to how Meta handled other controversial databases. When the company blocked alleged leaked Roe v. Wade decision details before official release, Meta issued a statement explaining that it was preventing distribution of apparent leaked confidential documents. The company didn't hide behind vague policy language; it explained the specific reasoning.

Why the difference? Possibly because the Roe leak situation was clear-cut: stolen information, legitimate confidentiality concerns, straightforward policy application. The ICE List situation is messier: public information, civil rights concerns, politically polarized, complicated competing interests. Meta might have chosen vagueness precisely because explaining the decision transparently would reveal how complicated and debatable it actually is.

That's frustrating for users trying to understand why their posts are being removed. And it's frustrating for researchers trying to evaluate whether the decision was justified. Meta's opacity makes it impossible to meaningfully engage with the company's reasoning.

The Precedent Question: What Gets Blocked Next?

If Meta can block ICE List, what other databases become vulnerable?

Consider a few hypothetical scenarios:

Police Officer Databases: Civil rights organizations document police misconduct. What if they created a searchable database of officers involved in incidents? Should Meta block it for officer safety? Should the company block links to existing databases like Badges Of Shame or Citizens Police Data Base?

Corporate Executive Directories: Activists targeting corporate practices sometimes identify executives responsible for policies they oppose. Should Meta block links to corporate directories because executives might be harassed?

Healthcare Provider Directories: Abortion providers have been tracked and harassed. Should Meta block public directories of doctors, clinics, and providers for their safety?

Prison Guard Information: Prison abolitionists have created databases of correctional officers. Should those be blocked?

Political Donor Lists: Campaign finance information is public. Should Meta block FEC disclosures because donors might face harassment for their political giving?

Once you accept that platforms can block information aggregation for safety and harassment prevention, the logic doesn't have obvious stopping points. Almost any database of identifiable people could theoretically enable harassment.

Meta's decision on ICE List will be interpreted by others—both critics and supporters—as precedent. It suggests the company is willing to restrict information aggregation when safety concerns arise. That interpretation will shape expectations for how Meta handles similar databases in the future.

The precedent could cut both ways. It might lead to more aggressive enforcement against databases across the spectrum. Or it might be treated as an isolated case specific to immigration enforcement and political sensitivity. But precedent matters in content moderation. Decisions echo.

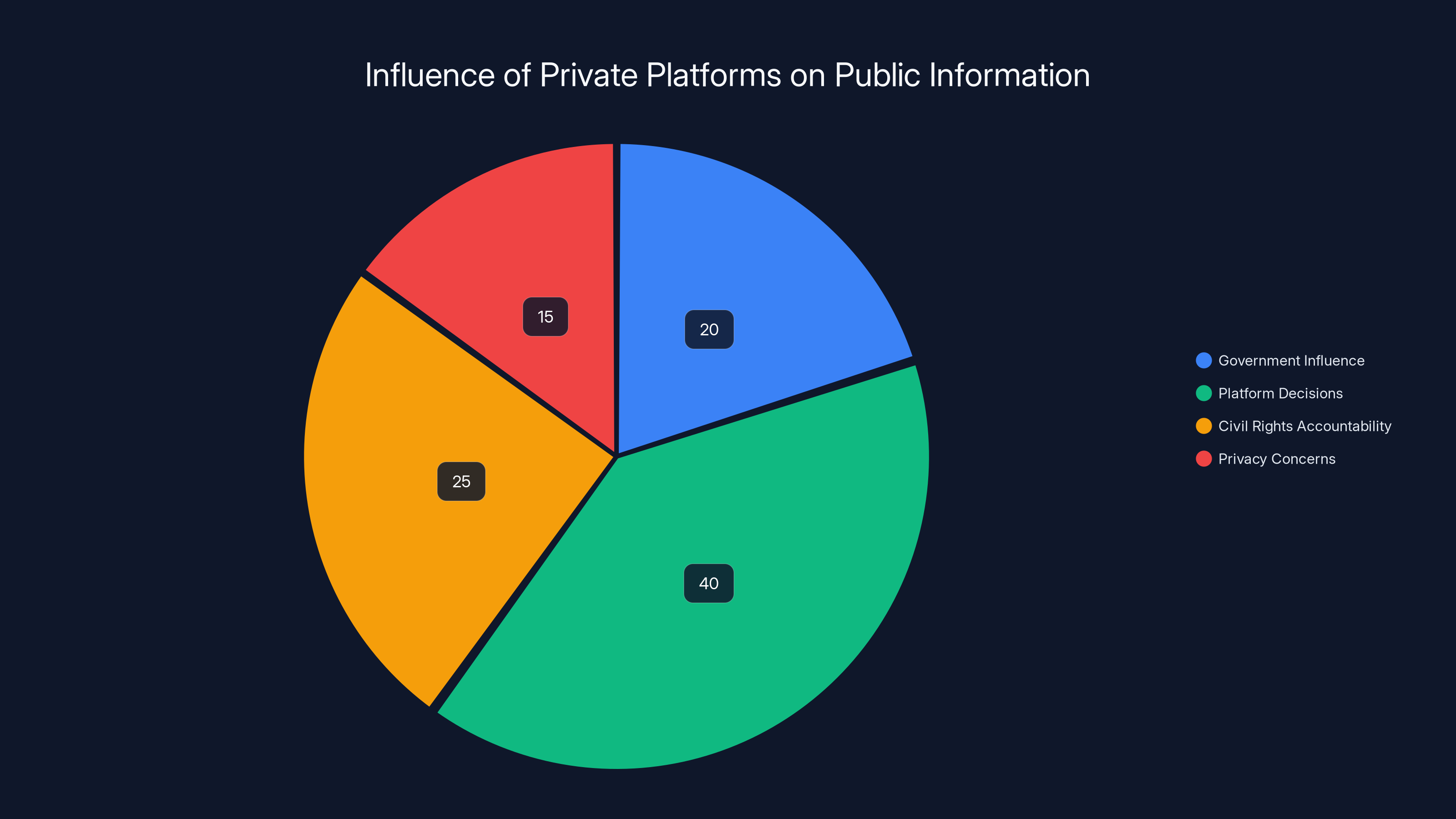

In 2025, private platforms are estimated to have a 40% influence on public information access, surpassing government influence. Estimated data.

Comparing Global Approaches: How Other Platforms Responded

Meta wasn't the only platform that faced this decision. Other tech companies also had to decide whether to allow ICE List links and information.

Some platforms were notably less restrictive. Twitter (now X), despite its own content moderation challenges, allowed links to ICE List. The company didn't remove posts sharing the database. Users could freely share and discuss it.

Reddit, which prides itself on minimal content moderation, similarly allowed ICE List discussions. Subreddits dedicated to immigration, civil rights, and activism hosted detailed conversations about the database.

YouTube videos discussing ICE List and its implications weren't systematically removed. The platform didn't block the content despite its significant law enforcement and government agency presence on the platform.

TikTok didn't block ICE List links, though the platform has its own complicated relationship with political content and government pressure.

The contrast is striking. Meta's approach was notably restrictive compared to other major platforms. That raises a question: was Meta responding to genuine safety concerns that other platforms missed? Or was Meta overcorrecting based on political pressure?

It's worth noting that Meta faced specific pressure from law enforcement groups and government agencies concerned about ICE safety. Those pressures might not have hit other platforms as hard. Twitter and Reddit have smaller law enforcement constituencies. YouTube's transparency around government requests and removals is better publicized.

Meta's approach also reflects the company's broader pattern on immigration enforcement content. The company has removed other immigration-related information before. The pattern suggests more aggressive moderation than competitors.

The Activism Angle: Why Immigration Advocates Built This Tool

Understanding ICE List requires understanding why immigration advocates thought they needed to build it.

From their perspective, ICE operates with insufficient accountability. The agency conducts thousands of enforcement actions annually, often in ways that immigrant rights advocates believe violate rights. But documentation of those actions is scattered. Families report incidents to organizations. Organizations note them. But there's no comprehensive picture.

Newsroom coverage of ICE is sporadic and often doesn't name responsible agents. Court cases sometimes identify specific officers, but that information isn't systematized. Leaked internal documents occasionally provide insights, but comprehensive documentation requires manual compilation from multiple sources.

ICE List was an attempt to change that. By creating a searchable database of incidents, agents, and facilities, the creators hoped to:

- Make patterns visible: Show which agents are repeatedly involved in problematic incidents

- Enable accountability: Document who's responsible for enforcement actions

- Support affected communities: Provide information that could help people understand risks

- Drive policy change: Use documentation to advocate for enforcement reforms

From a civil rights documentation perspective, this is valuable work. Similarly to how the Innocence Project aggregated exonerations to show wrongful conviction patterns, ICE List aggregated incidents to show enforcement patterns.

The problem is that the same database that enables civil rights advocacy also enables harassment and targeting. You can't separate those uses cleanly.

But from the activists' perspective, that's too bad. Accountability sometimes makes people uncomfortable. If ICE agents don't want to be in a database documenting their enforcement actions, they shouldn't conduct enforcement actions that warrant documentation. The solution to bad publicity isn't to suppress the publicizing—it's to change the behavior being publicized.

That's not unreasonable logic. But it's logic that prioritizes civil rights accountability over employee safety. And Meta chose differently.

Policy Implications: What This Means for Platform Governance

Meta's ICE List decision reveals something important about how platform governance actually works in 2025.

The company doesn't make decisions based purely on abstract principles or neutral policy application. Instead, decisions emerge from a complex mix of factors:

- Machine learning systems flagging content based on patterns

- Human moderators applying guidelines that are often vague

- Legal liability calculations

- Pressure from government agencies and law enforcement

- Concern about employee safety for people not even on Meta's payroll

- Political sensitivity around immigration and enforcement

- Public perception and brand management

No single one of these factors explains the decision. It's the combination.

When policymakers think about platform governance, they often focus on rules and appeals processes. If a user's content is removed, they should have recourse. They should know why. They should be able to contest the decision.

But Meta's system doesn't work that way for site-level blocks. When an entire domain gets blocked, users can't effectively appeal. They can't know Meta's reasoning. They can't debate whether the block was appropriate.

This gap between policy and practice is important. Meta has rules. But the enforcement of those rules at scale is opaque, often automated, and difficult to challenge.

From a policy perspective, that's a problem. Platforms making unilateral decisions about what information billions of people can access should probably have more transparency and accountability built in. If Meta can block ICE List, the public should know why, and that decision should be contestable.

Some countries are starting to require exactly that. The EU's Digital Services Act mandates transparency and explanation for content moderation decisions. Similar proposals have been made in the U.S. But Meta predates most of these regulations and has resisted transparency requirements.

The ICE List blocking is a small example of a much larger issue: private platforms functioning as gatekeepers for information, with minimal transparency and accountability.

Technical Workarounds and Information Spread

Once Meta blocked direct links to ICE List, people started finding workarounds. That's how information restriction tends to play out online: you can slow distribution but rarely stop it.

Users started posting screenshots of ICE List data instead of links. They used URL shorteners that didn't get caught by Meta's filters. They posted the domain name as text ("ice-list-dot-com") so users could manually type it. They discussed the database without directly linking to it.

These workarounds are technically against Meta's policies too. But they're harder for automated systems to detect. A screenshot of a database is harder to algorithmically flag than a direct link. Text-based domain names don't match URL filter lists.

So what Meta accomplished was friction, not prevention. The company made sharing ICE List harder. It reduced the casual spread through social media. But it didn't stop people from accessing or sharing the database if they were determined.

From Meta's perspective, friction is sometimes the goal. The company doesn't expect to prevent all sharing of problematic content. Instead, it aims to reduce amplification. By making direct sharing impossible, Meta reduces how much casual exposure the database gets. Someone sees a link in their feed might click it out of curiosity. Someone has to manually type the domain based on a screenshot? Less likely.

That distinction matters. Meta isn't claiming to eliminate access to ICE List. The company is claiming to reduce frictionless spread through its platforms. That's different, and it changes the evaluation of the decision's impact.

DHS and Law Enforcement Pressure: The Political Context

Did Meta's decision come directly from government pressure, or was it an independent choice?

Publicly, Meta hasn't revealed pressure. The company doesn't usually explain how law enforcement or government agencies influence moderation decisions. But based on precedent, it's likely.

We know Meta removed the Chicago ICE sighting tracking group after Justice Department pressure. That's documented. It's not a secret. So there's a clear precedent of Meta being responsive to law enforcement concerns about content that hampers enforcement operations.

When ICE List went viral, DHS likely expressed concern to Meta. Probably through official channels. Probably backed by the argument that the database endangered agent safety and hampered legitimate law enforcement.

Meta would have been in a difficult position. The company depends on a relationship with government. It needs law enforcement cooperation on crime and exploitation. It benefits from DHS cooperation on border security content (human trafficking, cartel recruitment, etc.). Ignoring DHS concerns creates friction.

But Meta also faces pressure from the other direction: civil rights advocates, immigration activists, journalists, and others who believe the company shouldn't comply with government requests that suppress inconvenient information.

Meta's decision suggests it weighted DHS pressure heavier than civil rights objections. That's a political choice, even if Meta frames it as a neutral policy application.

The politics matter here. If Meta is making content decisions based on pressure from law enforcement, that's government censorship through intermediaries. The First Amendment doesn't apply because Meta is private, but the outcome is similar: information becomes less accessible because someone with power doesn't want it shared.

The Broader Conversation: Information Access in 2025

ICE List is a specific case. But it points to a broader question about how information circulates in 2025.

We're living through a transition. Information that was previously difficult to access—government data, employee information, incident records—is increasingly public, aggregable, and searchable. Technology makes compilation and distribution trivial.

That has benefits. Civil rights documentation becomes easier. Corruption becomes harder to hide. Patterns become visible.

It also has costs. Privacy becomes harder to maintain. People can be targeted more easily. Visibility can feel like surveillance.

The old framework was: government controls access to government information (except what it chooses to make public). Private companies control access to business information. Individuals control their personal information.

The new framework is murkier. Information leaks. Databases get hacked. Public information gets aggregated. Once something is online, it's effectively public forever.

Platforms like Meta are trying to impose control on that murkiness. By blocking certain aggregations, the company is saying: "We'll limit how much visibility gets created around this particular information."

But it's not a stable solution. The information doesn't disappear. It just becomes less visible on Meta's platforms. Anyone seriously interested can find it elsewhere.

The real question is: should platforms have that power? Should Meta get to decide which public information can be aggregated and shared through its networks? Or should that decision be left to individuals?

Those aren't questions Meta is equipped to answer. The company is a business focused on engagement, not a neutral platform for information. Its incentives don't align with maximizing public information access.

But governments haven't figured out how to regulate this space effectively. And individuals can't opt out of platforms where social information circulates.

So we're left with private companies making decisions that reshape what information is accessible, often opaquely and based on unclear criteria.

Conclusion: When Private Platforms Shape Public Information

Meta's decision to block links to ICE List is one company's response to a complicated situation. But it illuminates something fundamental about how information flows in 2025.

We've moved past the era where governments alone controlled access to information. Tech platforms now make decisions that are equally consequential. When Meta blocks a website, billions of people lose easy access. When a platform recommends something, it shapes what becomes visible. When content gets flagged as spam, accuracy becomes secondary to algorithmic classification.

The ICE List case specifically reveals the tension between civil rights accountability and individual privacy. Immigration enforcement affects millions of people. Documenting that enforcement creates valuable civil rights records. But that documentation can also create risks for government employees.

Meta had to choose. The company chose to protect employee safety over information access. That's defensible. But it also means a specific interest group—government agencies concerned about employee safety—got priority over another interest group concerned about accountability.

That's inherently political, even if Meta frames it as neutral policy application.

Moving forward, several things seem likely:

First, platforms will continue making these decisions. They won't stop. Meta blocking ICE List won't eliminate the practice of aggregating public databases. It just makes it slightly less convenient.

Second, the decisions will continue to be opaque. Meta isn't likely to suddenly become transparent about why it blocks specific sites. The company will continue hiding behind generic policy language and automated decision-making.

Third, the tension between accountability and privacy will keep getting more acute. As technology makes aggregation easier, platforms will face more pressure to suppress databases they consider risky. And civil rights advocates will push back harder, arguing that suppression prevents necessary documentation.

Finally, regulation will probably increase. Governments frustrated with platform power will try to mandate transparency and appeal processes. The EU already has. Others will follow. Meta will resist, but probably not successfully.

In the immediate term, ICE List remains inaccessible through Facebook and Threads. The database still exists. People can still access it if they know where to look. But the easy spread through Meta's platforms is blocked.

That's less restrictive than censorship but more restrictive than freedom. It's the kind of middle ground that characterizes 2025 information governance: neither fully open nor fully closed, but managed by companies making political choices under the guise of neutral policy application.

Ultimately, the ICE List case is a test case for what comes next. How will platforms balance accountability against privacy? Will they move toward more transparency, or toward opacity? Will governments regulate them, or let them self-govern? Will civil rights advocates accept platform restrictions on accountability tools, or will they find workarounds?

Those questions don't have clean answers yet. But ICE List suggests the answers won't come from platforms voluntarily maximizing information access. They'll come from pressure, regulation, and the ongoing tension between different visions of what platforms should be.

FAQ

What is ICE List?

ICE List is a crowdsourced wiki that documents immigration enforcement actions and lists names of thousands of employees working for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and other Department of Homeland Security agencies. The site aggregates information about enforcement incidents, detention facilities, and individual agents primarily from public sources like LinkedIn profiles and news reports.

How did Meta discover ICE List was spreading on its platform?

ICE List went viral in early 2024 when the site announced it had compiled a list of 4,500 DHS employees. The announcement generated significant media coverage and social media discussion, with users sharing links across Facebook and Threads. Meta's content moderation systems and staff likely flagged the rapidly spreading links as potential violations, leading to the blocking decision.

Why did Meta block links to ICE List specifically?

Meta cited Community Guidelines violations, flagging the links as spam. The company's broader concerns likely involved potential harassment and safety risks to government employees, whose names were being aggregated into a searchable database. While Meta hasn't provided detailed reasoning, the blocking was justified under vague policy categories covering spam and potential harassment.

Is the information on ICE List actually leaked data or public data?

The majority of ICE List information comes from publicly available sources, particularly LinkedIn profiles where DHS employees had voluntarily listed their employment and job titles. While the site initially claimed to host a leaked database, investigative analysis revealed the 4,500-person list was primarily compiled through systematic aggregation of public profiles, not actual breached confidential documents.

Can people still access ICE List after Meta's blocking?

Yes. Meta's block prevents direct link sharing through Facebook and Threads, and some sharing methods trigger error messages. However, the site itself remains online and accessible to anyone who manually navigates to it or uses workarounds like screenshots, text-based domain references, or other platforms that haven't blocked access.

What other platforms have blocked or allowed ICE List?

Twitter (now X), Reddit, YouTube, and TikTok did not systematically block ICE List links. These platforms allowed users to share and discuss the database, contrasting with Meta's more restrictive approach. The difference reflects both varying content moderation philosophies and different law enforcement pressure on different platforms.

Could Meta's action on ICE List set a precedent for blocking other databases?

Potentially. The decision could encourage Meta to apply similar restrictions to other aggregated databases of public figures or government employees, including police officer directories or corporate executive databases. However, it might also be treated as a specific case related to immigration enforcement rather than a broader policy shift. The precedent remains unclear and inconsistently applied.

Did the U.S. government directly pressure Meta to block ICE List?

There's no public confirmation of direct government pressure, though it's likely given documented precedent. Meta removed a Chicago ICE-sighting tracking group after Justice Department pressure previously. The pattern suggests law enforcement concerns probably influenced Meta's decision, though the company hasn't confirmed this.

What are civil rights advocates saying about Meta's decision?

Civil rights groups argue that blocking ICE List suppresses important accountability documentation. They contend that government employees, particularly those conducting enforcement operations, have reduced privacy expectations and that aggregating publicly available information serves civil rights oversight. They view Meta's decision as prioritizing law enforcement interests over public accountability.

How does this decision reflect broader platform governance challenges in 2025?

Meta's ICE List decision exemplifies how private platforms now make determinations about information access that have consequences for billions of users. It highlights opacity in content moderation, inconsistent application of policies, political sensitivity influencing supposedly neutral decisions, and the tension between different stakeholders' interests. The case suggests platforms need greater transparency and accountability in how they govern information flow.

Related Topics Worth Exploring

This situation connects to broader conversations about content moderation, government transparency, privacy rights, and how information circulates online. If you want to understand the bigger picture, consider exploring platform governance regulations like the EU's Digital Services Act, how governments pressure tech companies to remove content, the history of government employee identification online, and how civil rights organizations use data aggregation for advocacy.

The ICE List case is a microcosm of larger tensions about who controls information in 2025, and those tensions will only become more acute as technology makes aggregation and distribution easier.

Key Takeaways

- Meta blocks links to ICE List, a crowdsourced database of immigration enforcement agents' names, citing Community Guidelines and spam concerns

- Most ICE List data comes from public LinkedIn profiles, not actual leaked confidential information, complicating the censorship narrative

- The decision reveals tension between civil rights accountability (documenting enforcement) and employee safety concerns (preventing harassment)

- Different platforms handled ICE List differently—Meta was notably more restrictive than Twitter, Reddit, YouTube, or TikTok

- The case illuminates broader questions about how private platforms control information access and the opacity of content moderation decisions at scale

Related Articles

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation or Political Censorship? [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

- Tech Workers Demand CEO Action on ICE: Corporate Accountability in Crisis [2025]

- UK Pornhub Ban: Age Verification Laws & Digital Privacy [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Minnesota ICE Coercion Case: Federal Punishment of Sanctuary Laws [2025]

![Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-blocks-ice-list-content-moderation-privacy-free-speech-/image-1-1769557142929.jpg)