The Masked Police Problem Nobody Can Seem to Solve

Imagine police showing up at your door. You can't see their faces. You don't know their names. The badges are hidden or obscured. This isn't science fiction. This is what happens when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents wear face-covering gaiters during raids across America.

The problem isn't subtle. An assassin killed Minnesota state legislator Melissa Hortman and her husband by impersonating law enforcement. How would anyone distinguish between actual cops and someone with bad intentions when officers themselves are unidentifiable? This basic accountability question has sparked a national movement, but the legal answer remains surprisingly complicated.

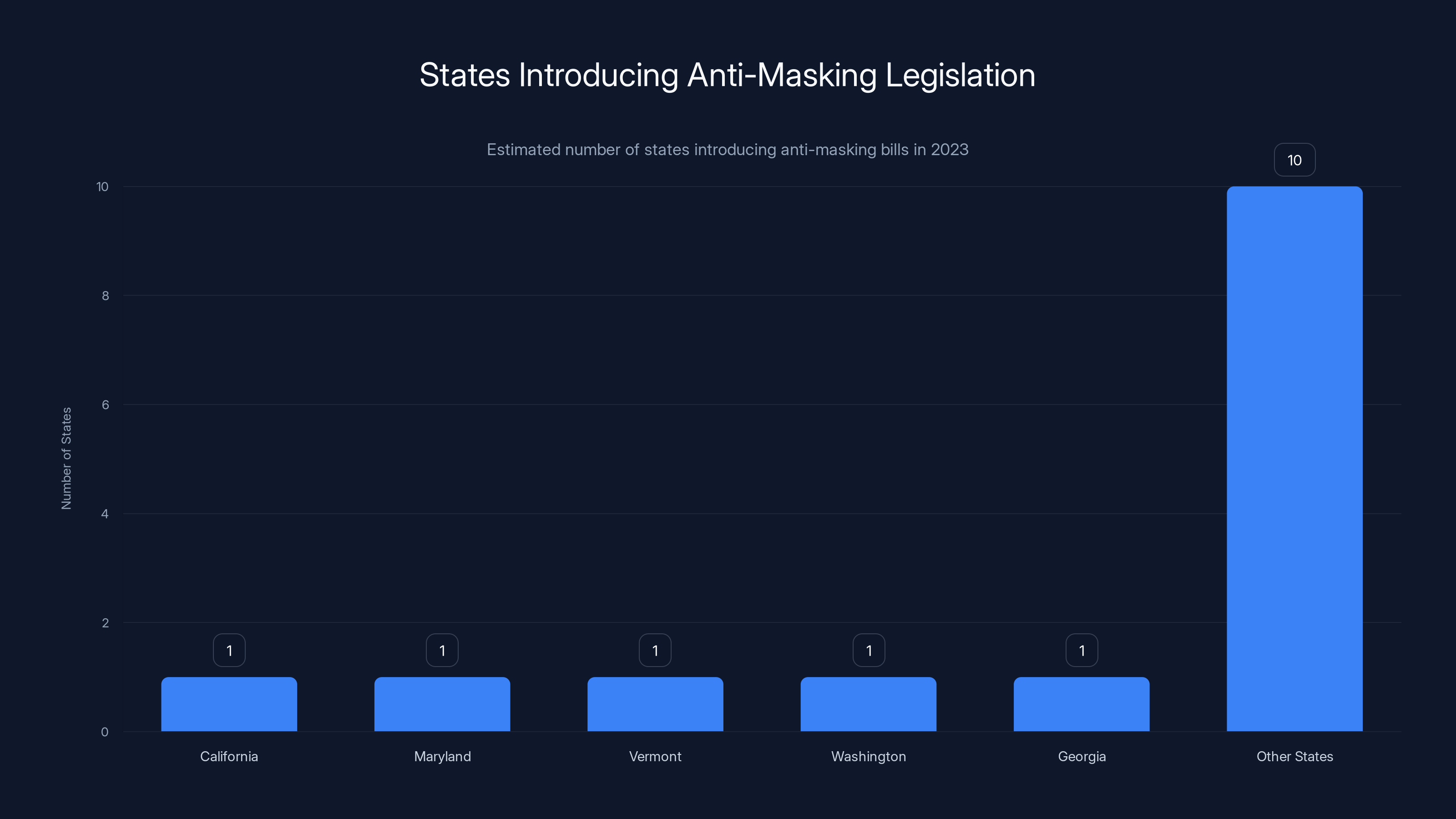

California passed the No Secret Police Act last year, a straightforward law banning masked federal law enforcement. The Department of Homeland Security immediately sued to block it on constitutional grounds. That lawsuit is still pending. Meanwhile, legislatures in at least 15 states have introduced similar anti-masking bills. Maryland, Vermont, Washington, and Georgia all introduced new legislation recently. Yet nothing has stopped ICE from continuing the practice.

The gap between what Americans want and what the law allows reveals something troubling about federal power, state authority, and the limits of legislative action. It also exposes how federal agencies use threats and fear to justify practices most people find unacceptable.

Here's what's actually happening behind the legal standoff, and why constitutional law might be preventing the accountability everyone assumes should be simple.

The Surge in Anti-Masking Laws

After California's No Secret Police Act passed, the legislative floodgates opened. Suddenly, state legislators realized they could act where Congress wouldn't. The House introduced its own version of the No Secret Police Act, while the Senate proposed the VISIBLE Act. Neither has traction with Republican majorities controlling both chambers.

State action moved faster. Los Angeles passed a city ordinance. St. Paul is considering one. Minnesota announced plans to introduce legislation when the session opens. The pattern is consistent across the country: states don't want masked federal police operating within their borders.

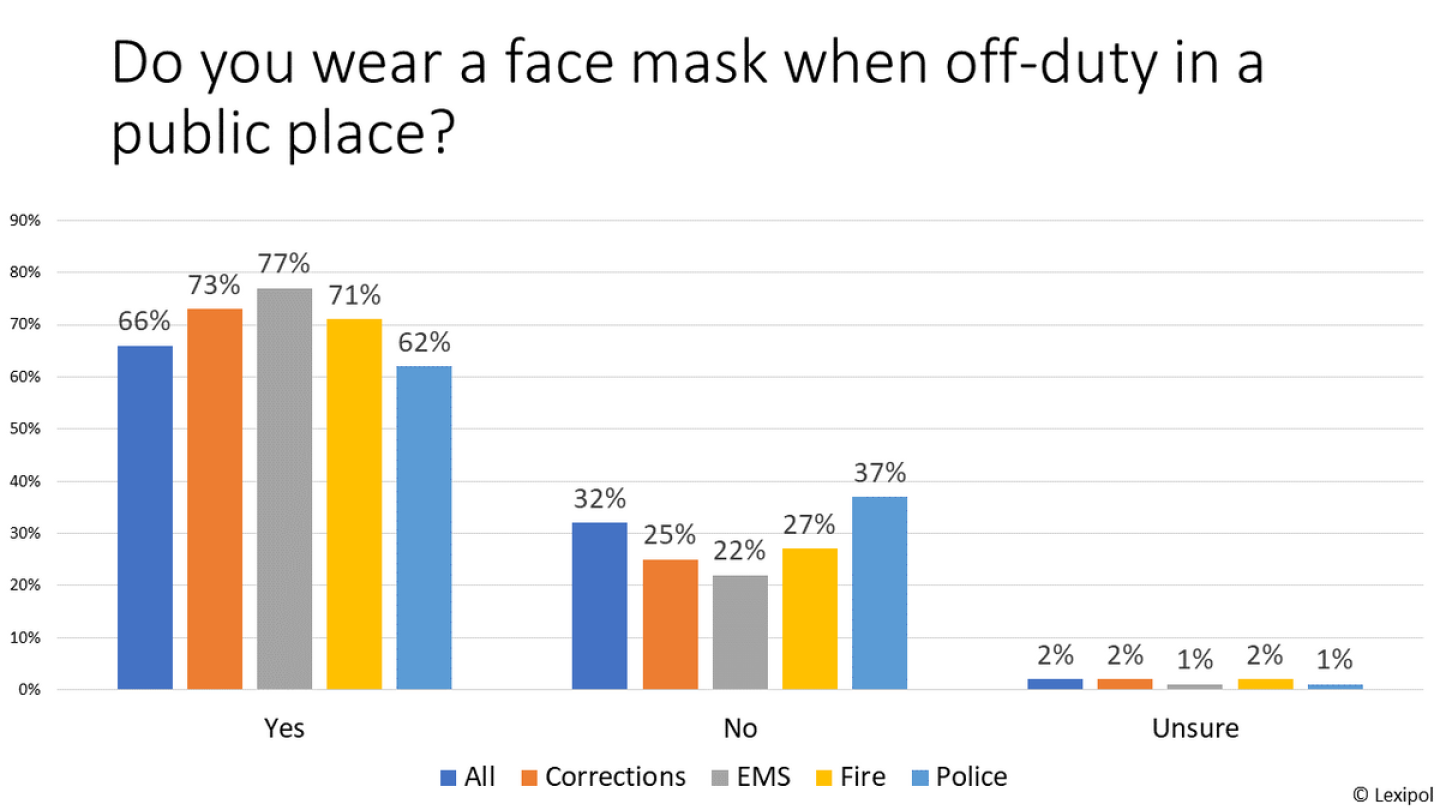

What makes this movement significant is its bipartisan nature. Law-and-order Republicans worried about accountability joined progressive activists concerned about federal overreach. Nobody was arguing in favor of masked police. The only opposition came from DHS itself.

Why the Public Hates Masked Police

The opposition to masked ICE agents isn't ideological theater. It stems from practical, tangible concerns that most Americans share regardless of politics.

Impersonation Risk: An unidentified person in a tactical vest could be anyone. Criminals have impersonated police for centuries. When actual law enforcement obscures their identity, they create the perfect cover for bad actors. The Hortman assassination proved this isn't theoretical anymore.

Zero Accountability: You can't file a complaint against someone you can't identify. You can't testify against them if you don't know their name. You can't verify their employment or training. Accountability requires identification, and identification requires seeing faces.

Trust Erosion: Law enforcement depends on community trust. Masked officers send the message that police don't trust the public, which is reciprocated. Why would you trust an unidentifiable agent entering your home without a warrant?

Danger to Everyone: Masked federal agents entering neighborhoods create confusion. Residents can't tell who's law enforcement and who isn't. This creates dangerous situations for civilians and officers alike.

Polling data consistently shows Americans don't support masked police. The disagreement isn't about whether masking is good policy. The disagreement is purely legal: whether states can ban it.

The Constitutional Problem Nobody Wants to Talk About

Here's where the legal situation gets complicated in ways that frustrate almost everyone involved.

The Department of Homeland Security argues that California's No Secret Police Act violates the Constitution in multiple ways. First, they claim it interferes with federal law enforcement authority. Second, they argue it violates the Supremacy Clause, which makes federal law superior to state law. Third, they contend it infringes on federal officers' rights under the First and Fifth Amendments.

That third argument is the surprising one. Federal attorneys claim officers have a constitutional right not to be identified. This right, they argue, stems from personal safety concerns. Death threats against federal officers have increased, DHS claims. Doxxing is a real phenomenon. Federal agents worry about retaliation against themselves and their families.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem made this argument on national television, accusing a CBS News moderator of "doxxing" an ICE agent by mentioning his name. The agent in question had already been publicly identified in numerous videos of an incident. His name was already public. But Noem's point was broader: even public information shouldn't be repeated because it puts officers at risk.

This constitutional question isn't frivolous. Courts do recognize some privacy interests for law enforcement officers. Some states have laws protecting officer home addresses. The question becomes whether identification while performing official duties receives the same protection.

The Federal Supremacy Argument

The strongest argument DHS makes involves federal supremacy. Immigration enforcement is a federal function. States traditionally cannot interfere with federal law enforcement operations. California cannot tell FBI agents how to conduct investigations. It cannot restrict DEA operations. Can it restrict ICE?

If the answer is yes, DHS argues, then every state could impose different rules on federal agents. Texas could require different equipment. New York could demand different protocols. Federal law enforcement would become a patchwork of 50 different regulatory regimes.

This isn't hypothetical. Federal law enforcement depends on uniform authority. If states can mandate how federal officers dress, what they carry, or how they identify themselves, the entire system becomes unworkable.

The Supremacy Clause typically prevents states from blocking federal operations. But California isn't trying to block ICE. It's imposing an operational requirement. Does that distinction matter legally? The answer determines whether the law survives.

The First Amendment Problem

Federal attorneys argue that requiring officers to show their faces violates the First Amendment because it compels speech. Every visible face is a form of identification, which is a form of expression. Forcing officers to be identifiable, they argue, violates their right to remain silent about their identity.

This argument sounds absurd. The First Amendment typically protects positive speech, not the right to be anonymous while exercising government authority. But the Supreme Court has recognized some First Amendment interests in anonymity. Would those interests protect a federal officer's choice to wear a gaiter?

The honest answer is probably no. Courts have consistently held that the government can require identification from its own employees while they're performing official duties. A police officer can't wear a mask to hide his identity on duty. Federal officers shouldn't be different.

But DHS is betting that some courts might disagree, or that the legal complexity is enough to delay implementation.

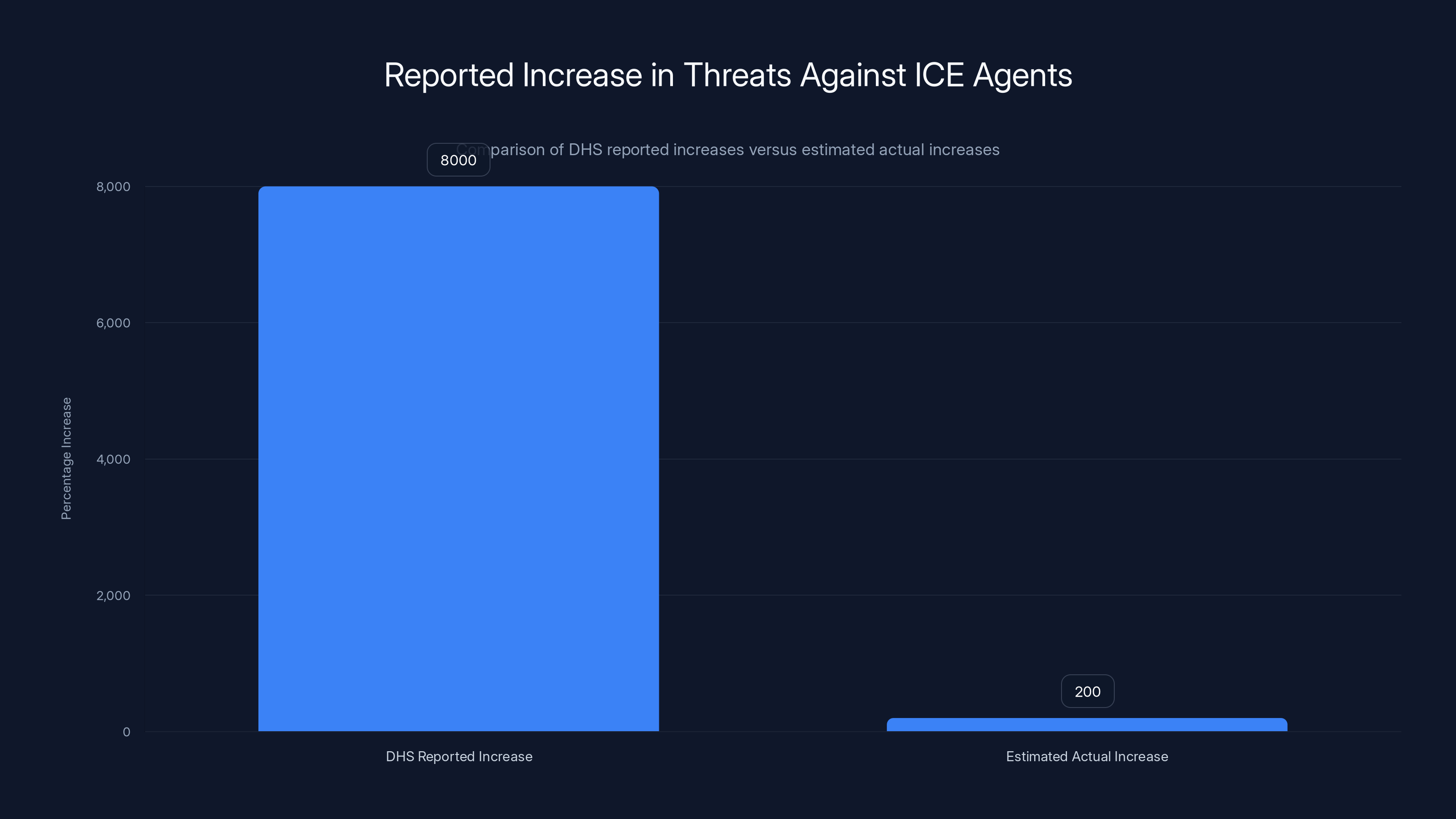

DHS reported an 8,000% increase in threats against ICE agents, but investigations suggest the actual increase is likely much lower, around 200% (Estimated data).

The Doxxing Fear and What's Actually Happening

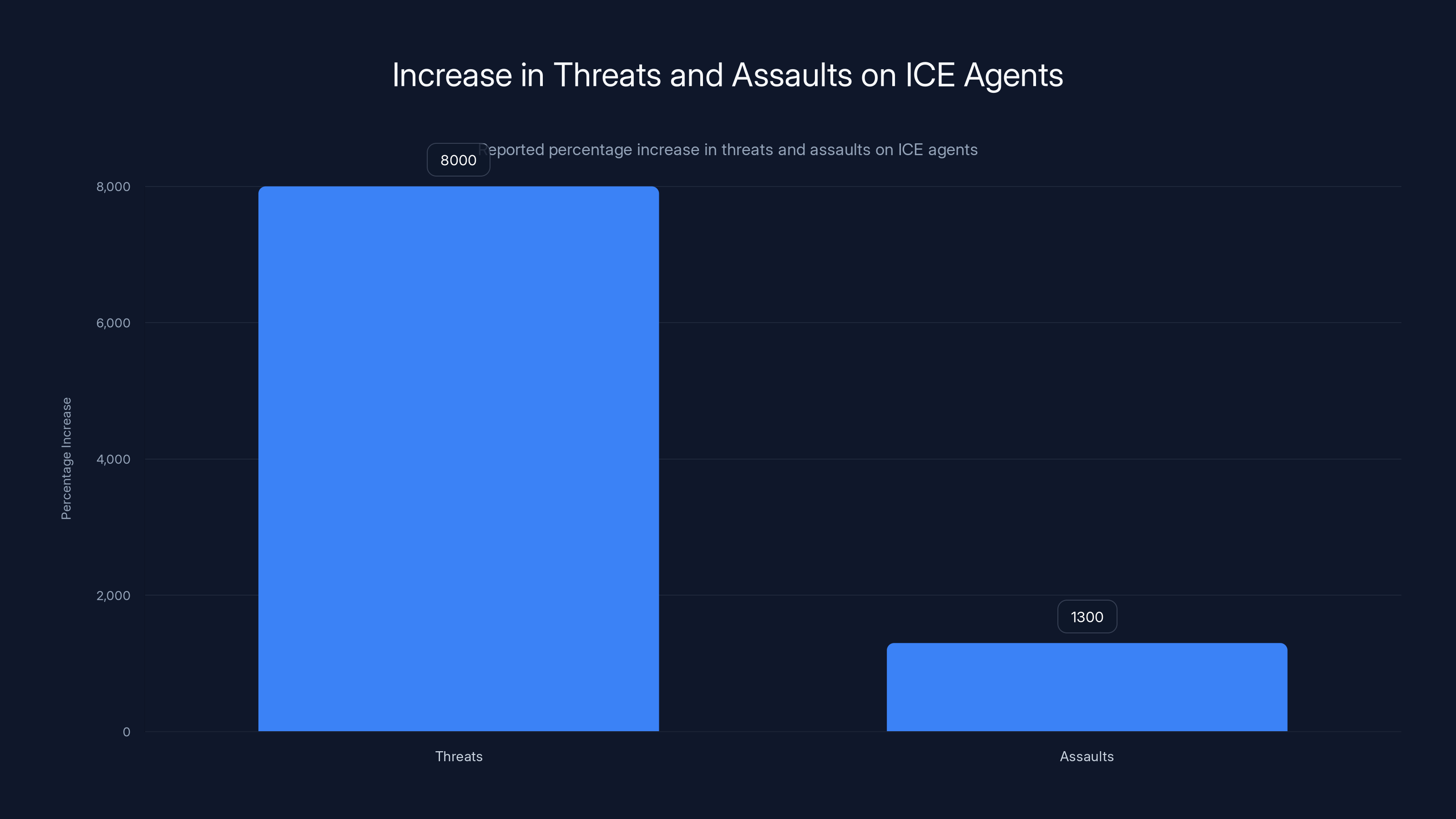

DHS released statistics claiming death threats against ICE agents increased 8,000 percent and assaults increased 1,300 percent. These numbers are staggering. They're also presented with almost no documentation.

The DHS website consists mostly of blurry screenshots of X posts. There are a few photos of alleged threats. But there's no methodology. No baseline year for comparison. No verification. An 8,000 percent increase from what starting point? If there were two threats one year and 160 the next year, that's technically an 8,000 percent increase. It's mathematically true but misleading.

The strategy is clear: use fear to justify the practice. If officers are under attack, keeping their identities secret makes sense. Never mind that ICE operations have become increasingly controversial specifically because of secrecy and lack of accountability.

There's also a circular logic here. ICE argues it needs to wear masks for safety. But the danger stems partly from the agency's controversial practices. Residents are upset about immigration enforcement tactics, not about the agency itself. Making enforcement more accountable might actually reduce hostility.

Instead, DHS doubles down on secrecy, which increases distrust, which increases anger, which supposedly justifies more secrecy. It's a feedback loop that prevents the accountability everyone claims they want.

What the Actual Data Shows

When you dig into threat data from other federal agencies, the picture becomes clearer. FBI agents don't wear masks. They operate without requiring gaiters. Death threats against federal law enforcement officers do occur, but they're not unique to ICE.

The 8,000 percent figure, when scrutinized, collapses. DHS hasn't provided actual threat numbers. News organizations have investigated and found exaggerated claims. Some increase in threats probably occurred, following general polarization trends. But the magnitude claimed by DHS appears inflated.

This matters because it affects how courts evaluate the government's argument. If the threat situation is genuinely serious, courts might give DHS more deference. If the numbers are propaganda, courts should be skeptical.

ICE reports an 8,000% increase in threats and a 1,300% increase in assaults on agents, justifying the need for anonymity protections. Estimated data.

California's Legal Challenge and the Supremacy Question

California's No Secret Police Act was straightforward: federal law enforcement operating in California must display clear identification and cannot wear face-covering masks. The law applies during official duties. It's not about harassing officers. It's about basic accountability.

DHS challenged it immediately on Supremacy Clause grounds. The legal question before the court is whether a state can impose operational requirements on federal law enforcement.

The answer isn't obvious. Some Supreme Court precedent suggests states cannot interfere with core federal functions. But other precedent suggests states can impose generally applicable rules on everyone, including federal officers. If California required all people in the state to wear visible identification during police operations, the requirement applies to everyone, not just federal agents.

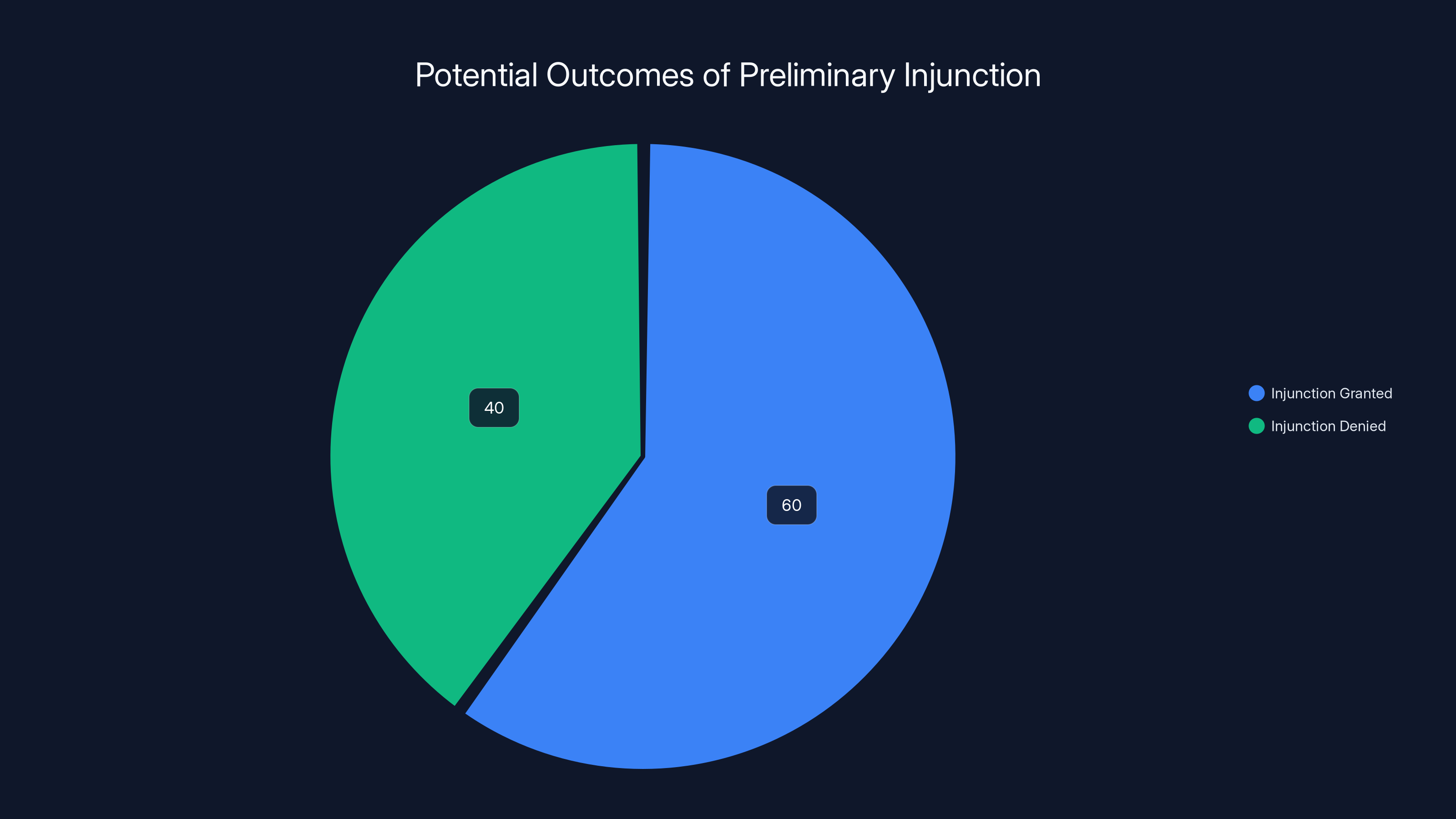

The judge hasn't ruled on DHS's request for a preliminary injunction. This matters because preliminary injunctions determine who operates under what rules while the case proceeds. If the judge blocks the law temporarily, ICE continues masking during the litigation. If the judge lets the law stand, ICE must comply while the case proceeds.

That decision alone could change everything. A preliminary injunction favoring DHS sends a message that the law probably isn't constitutional. It also maintains the status quo, which favors the federal government.

What Other States Are Actually Proposing

Not all state anti-masking bills are identical. The variations reveal different approaches to the constitutional problem.

Minnesota's approach: The legislator who planned to introduce the bill focused on accountability and identification, not on preventing ICE operations. The law would require clear identification but wouldn't necessarily prevent gaiters if the officer's name was visible.

Maryland's approach: The proposed bill required law enforcement to display agency and name, with fines for violations. It's more about documentation than complete unmasking.

Washington's approach: The bill proposed requiring ID cards visible from a distance, allowing some flexibility in how officers dress while ensuring identifiability.

These variations matter legally. A law that simply requires identification is different from a law that bans specific clothing. Courts might view identification requirements as more likely to survive constitutional challenges.

The Congressional Stalemate

Federal anti-masking bills have been introduced in Congress repeatedly. The No Secret Police Act in the House and the VISIBLE Act in the Senate are the most recent versions. Both have gone nowhere.

With Republicans controlling both chambers, these bills face intense headwinds. The Trump administration opposes them. DHS opposes them. Border security hawks argue that any restriction on ICE operations undermines immigration enforcement.

This creates an odd situation where public opinion strongly supports anti-masking laws, but Congress won't pass them. Federal action is blocked. State action faces constitutional challenges. The result is a legal stalemate that benefits the status quo.

ICE continues operating as it has been, with agents wearing gaiters during raids, essentially unidentifiable to the public they're supposed to serve.

Estimated data shows a surge in states introducing anti-masking legislation, with at least 15 states taking action in 2023.

The Tension Between Federal Authority and State Sovereignty

The deeper issue underlying all of this involves fundamental questions about federalism. When do states have authority to regulate activities within their borders? When does federal authority override state authority?

The Supreme Court's approach to these questions has evolved. For decades, the Court assumed federal authority over immigration was absolute and states couldn't interfere. But recent decisions have suggested states can impose certain conditions on operations within their borders.

For example, state environmental laws apply to federal facilities. State labor laws apply to federal contractors. Federal agents operating in a state must follow many state rules. The question becomes whether anti-masking requirements fit that pattern or whether they genuinely interfere with federal functions.

DHS argues they interfere with federal functions. Requiring identification makes undercover operations impossible. It compromises officer safety. It restricts federal authority in ways that violate the Supremacy Clause.

California argues they don't interfere with the core federal function. The core function is immigration enforcement. You can still enforce immigration laws while being identifiable. Many federal law enforcement agencies do exactly that without wearing masks.

The judge will eventually decide which argument prevails. But that decision likely heads to higher courts. The Supreme Court might ultimately settle the question. Until then, California's law remains blocked, and ICE continues masking agents.

Public Safety Concerns Beyond Impersonation

The Hortman assassination was the catalyst for anti-masking legislation, but the concerns extend beyond impersonation risk.

Masked officers create confusion in neighborhoods. Residents see tactical gear and can't immediately tell if it's legitimate law enforcement or a threat. This confusion creates dangerous situations. People might resist out of fear. They might try to protect themselves. A misunderstanding could turn violent.

Documented cases exist where ICE agents entered homes without proper warrants or used excessive force. Without identification, victims can't immediately report specific officers. They can't identify who conducted the raid. They can't pursue accountability.

For immigrant communities, masked ICE agents represent state power exercised without accountability. Immigration enforcement is already controversial. Making enforcement agents unidentifiable amplifies the perception that the government is acting in secret.

The Broader Accountability Framework

Masking prevents accountability at multiple levels. At the individual level, victims can't identify officers. At the agency level, supervisors can't effectively track which officers are involved in controversial incidents. At the systemic level, the public can't evaluate whether enforcement is being conducted fairly.

Accountability is supposedly a core principle of democratic law enforcement. Police answer to the people. Unidentifiable police answer to no one. It's fundamentally undemocratic.

Yet DHS treats masking as essential to operations. The agency has resisted every effort to require identification. It sued to block California's law. It claimed constitutional protections for officer anonymity. The federal government is essentially arguing that accountability is less important than operational flexibility.

Estimated data suggests a 60% probability that the preliminary injunction will be granted, maintaining the status quo favoring federal operations.

The DHS Constitutional Arguments Unpacked

Let's examine each of DHS's constitutional arguments in detail.

The Supremacy Clause argument: This is the strongest argument. The Constitution explicitly states that federal law is supreme. When federal and state law conflict, federal law wins. But courts interpret this narrowly. They don't assume every state law conflicts with federal operations just because federal operations occur in the state.

For example, states can enforce workplace safety rules on federal facilities. States can enforce environmental rules on federal contractors. The key distinction is whether the state law actually prevents the federal function or merely imposes conditions on how the function is performed.

California's law doesn't prevent ICE from enforcing immigration law. It merely requires identification while doing so. That's different from blocking operations entirely.

But DHS could argue that identification compromises operations. If officers must be identifiable, they lose the ability to conduct surveillance without alerting subjects. They lose tactical advantages. They face retaliation risks.

These arguments have some merit. But they don't necessarily override state authority. Most federal law enforcement operates while being identifiable. The FBI, DEA, Secret Service all maintain operational effectiveness while using traditional badges and identification. Why should ICE be different?

The First Amendment argument: This is weaker. The First Amendment protects speech, not silence. It protects the right to express yourself, not the right to keep your identity secret while performing government duties.

Government employees have fewer constitutional rights than ordinary citizens. Courts have consistently held that the government can require employees to wear certain uniforms, display certain identification, and adhere to certain dress codes. An ICE agent doesn't have a First Amendment right to wear whatever they want while on duty.

Applying the same logic, an ICE agent doesn't have a First Amendment right to keep their identity secret while performing official duties. Courts have generally rejected anonymity arguments when applied to government employees exercising authority.

DHS might argue that anonymity is necessary for personal safety. That's a stronger argument. But safety concerns don't typically override constitutional requirements.

The Fifth Amendment argument: DHS's Fifth Amendment claim seems to involve due process rights. But that's also weak. Federal officers don't have a due process right to be anonymous while exercising authority over the public. Due process typically protects the person being acted upon, not the government actor.

Overall, DHS's constitutional arguments are weak. But constitutional weakness doesn't mean they'll lose. Courts defer to federal law enforcement on security matters. A judge might accept DHS's arguments even if they're legally shaky.

Why Federal Courts Might Side With DHS

Despite weak constitutional arguments, DHS has several advantages in court.

First, courts defer to executive branch expertise on security matters. Federal judges rarely second-guess federal law enforcement about operational needs. If DHS says masking is necessary for officer safety, judges might accept that claim without detailed scrutiny.

Second, the burden of proof matters. California has to prove the law is constitutional. DHS has to defend it. But DHS gets deference. California has to overcome that deference. That's a high bar.

Third, preliminary injunctions favor the status quo. If a judge isn't sure who will ultimately win, the preliminary injunction usually maintains the existing situation. ICE currently wears masks. Maintaining that practice is easier than changing it pending litigation.

Fourth, federal courts are generally protective of federal power. Judges appointed by both parties tend to favor broad federal authority over immigration enforcement. State attempts to restrict that authority face skepticism.

These factors combined mean DHS has a decent chance of winning, even with weak legal arguments. That's how law actually works sometimes. Power, deference, and institutional advantages matter as much as legal theory.

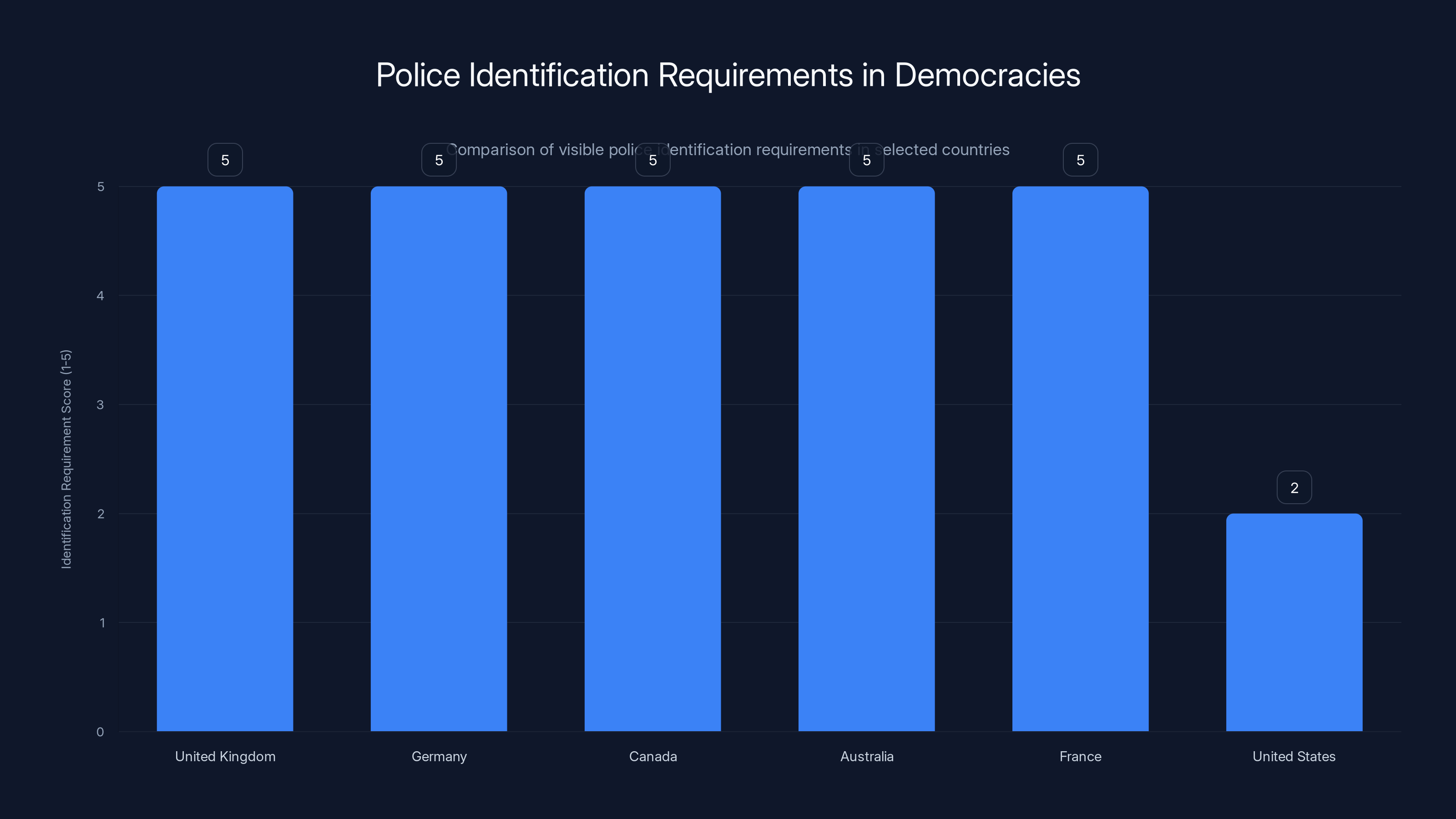

Most democracies require visible police identification, scoring 5 out of 5, while the U.S. scores lower due to less stringent requirements. Estimated data.

What Victory Would Actually Mean

If DHS wins the California case, the implications extend nationwide. Other state laws face similar constitutional challenges. If California's law fails, Maryland's, Washington's, and every other state's law probably fails too.

The ruling would essentially establish that states cannot impose identification requirements on federal law enforcement. That precedent would apply far beyond masking. It could affect state labor laws, environmental laws, and other rules applied to federal operations.

For immigrant communities and civil rights advocates, a DHS victory means continuing unidentifiable federal enforcement. It means the Hortman assassination risk remains. It means accountability remains impossible.

It also means the federal government has essentially declared that secrecy is more important than public trust. The government is saying: we would rather operate without accountability than meet your identification requirements. That's a powerful statement about the relationship between government and citizens.

The Alternative: If California Wins

If California's law survives, it becomes a model for other states. Suddenly, every state can impose identification requirements. Federal law enforcement would have to adapt.

Would adaptation actually happen? Probably yes. Federal agencies adapt to state requirements in many contexts. The TSA works within state airports. The FBI works within state legal frameworks. ICE can work within state identification requirements.

The real question is whether federal enforcement becomes less effective. DHS claims it does. ICE argues unidentifiable officers are essential to operations. But other federal agencies operate effectively while being identifiable. Why should ICE be different?

A California victory wouldn't end immigration enforcement. It would make enforcement more accountable. For most people, that's exactly the point.

The Future of Anti-Masking Laws

Regardless of how California's case resolves, the anti-masking movement isn't disappearing. Too many states are interested. Too much public support exists. The momentum is real.

Even if California loses, other states will try different approaches. They might require agency identification without specifying how it's displayed. They might require name badges without banning gaiters. They might focus on documentation requirements rather than visibility requirements.

Legislators are creative at working around constitutional obstacles. If the courts block one approach, other approaches emerge. The fight for ICE accountability will continue through different mechanisms.

California's defeat wouldn't end the movement. It would redirect it. State legislatures would draft laws more carefully, incorporating lessons from the litigation. They would consult constitutional scholars. They would craft requirements more likely to survive legal challenge.

The underlying issue won't resolve through litigation anyway. It will resolve through politics. Eventually, federal legislation will probably pass, explicitly allowing states to impose identification requirements. Or federal legislation will explicitly protect federal authority, clarifying that states cannot interfere. Either way, Congress will eventually settle the question.

Until then, we're stuck in a constitutional limbo where the public strongly opposes something the government claims is necessary, and lawyers argue about supremacy clauses and preliminary injunctions.

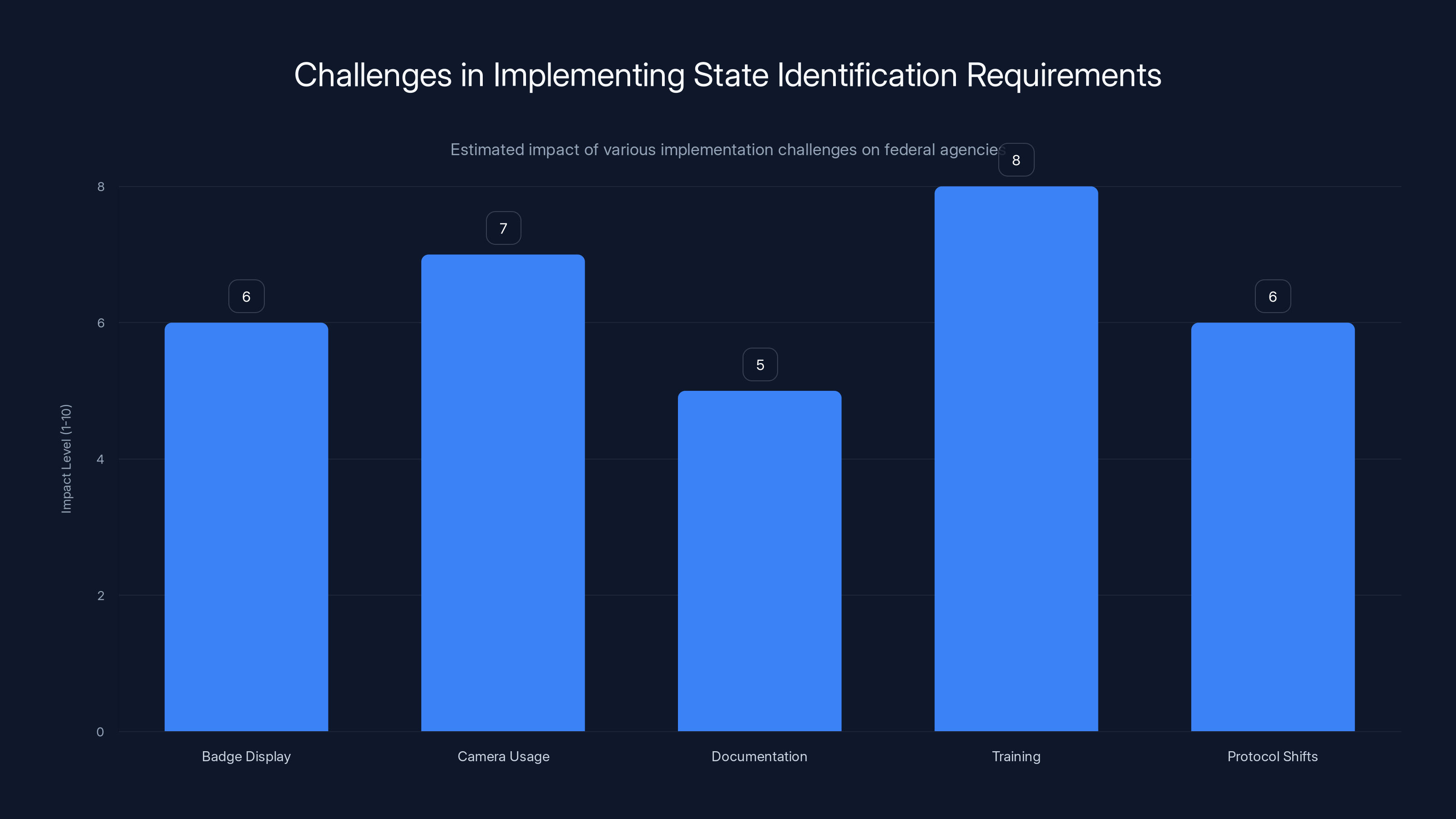

Estimated data shows that training and camera usage pose the highest implementation challenges for federal agencies when adapting to state identification requirements.

International Perspectives on Police Identification

America's struggle with police accountability isn't unique. Other democracies have grappled with similar questions.

Most developed countries require visible police identification. The United Kingdom requires officers to display rank, name, and station number. Germany requires similar identification. Canada requires visible identification. Australia requires it. France requires it.

These democracies have all concluded that accountability is worth potential operational constraints. They've determined that public trust matters more than tactical advantages. They're not suffering from uncontrolled immigration enforcement because their officers are identifiable.

The comparison isn't perfect. American police culture differs from international norms. Immigration enforcement is more controversial in the U.S. than in some other countries. But the international pattern is clear: democracies generally require police identification.

America's hesitation to require ICE identification puts it out of step with peer nations. That's worth noting in debates about what's necessary versus what's simply preferred.

The Role of Technology and Modern Surveillance

One argument DHS makes is that technology has changed law enforcement. Modern surveillance capabilities mean officers don't need to hide their identities to gather intelligence. They can conduct surveillance remotely. They can use databases and facial recognition. Visibility doesn't necessarily compromise operations.

This actually suggests that the masking requirement is outdated. If surveillance and intelligence gathering can happen without requiring unidentifiable officers, then masking isn't essential. It's just convenient.

Modern policing relies on intelligence collection, database queries, and technological surveillance more than traditional undercover operations. Most ICE enforcement happens against people already identified in government systems. The agency isn't typically running undercover operations where officer identity matters tactically.

So the argument that masking is operationally necessary probably overstates its importance. Masking might be convenient. It might feel safer to individual officers. But it's probably not actually essential to immigration enforcement.

That fact should matter in court. If California can demonstrate that ICE doesn't actually need masks to function effectively, the Supremacy Clause argument weakens significantly.

Practical Implementation Challenges

If states successfully impose identification requirements, implementation gets complicated.

Federal officers would need to display badges differently. Some would need cameras to record interactions. Some would need documentation procedures. Training would change. Protocols would shift.

These changes are manageable. Police agencies implement new requirements constantly. But they do require resources and adjustment.

ICE might actually prefer facing court losses to making these operational changes. A court ruling against California is simpler than redesigning agency protocols. So DHS's litigation strategy makes practical sense even if the legal arguments are weak.

From an efficiency standpoint, federal litigation is less disruptive than compliance with 15 different state requirements. One Supreme Court ruling resolves the question nationally. Compliance with state laws requires negotiating with 15 separate legislatures and adapting to 15 separate standards.

So federal resistance to state laws isn't purely about constitutional principle. It's also about bureaucratic efficiency. The federal government prefers its current arrangement to the chaos of 50 different state systems.

The Democratic Deficit Problem

Underlying all of this is a fundamental democratic question: should unelected federal bureaucrats be able to ignore what voters want?

California voters want identified police. Their legislature passed a law reflecting that preference. DHS ignores it because constitutional law might allow federal overrides.

That's the tension. Constitutional law creates space for federal power even when majority preference contradicts federal action. That's intentional. The Constitution limits democracy sometimes. But it shouldn't eliminate it entirely.

The question becomes whether federal law enforcement masking is the type of issue that should be resolved by constitutional limitations on democracy or by ordinary political processes. If it's truly essential to federal authority, maybe constitutional protection is appropriate. But if it's merely convenient or preferred, maybe states should be able to impose requirements that reflect their values.

Courts will have to wrestle with that distinction. It's not purely a legal question. It's a question about what role democratic majorities should play in shaping law enforcement practices.

What Would Actual Compromise Look Like

Instead of litigation, what if DHS and states negotiated?

Maybe officers display names but not faces. Maybe face coverings are allowed in specific dangerous situations but prohibited in standard operations. Maybe officers wear body cameras that record all interactions, compensating for anonymity. Maybe identification can be partially concealed but not completely.

These compromises would satisfy both concerns. States get accountability through identification or recording. Officers get some protection for personal safety. Immigration enforcement continues without major operational changes.

But compromise requires both sides willing to negotiate. DHS seems unwilling. The agency litigates instead. That suggests DHS views masking as genuinely essential, not merely preferred.

Or it suggests DHS prefers to avoid setting a precedent of yielding to state demands. If DHS compromises on masking, what else might states demand? The agency might feel that firmness now prevents bigger concessions later.

Either way, we're stuck with litigation instead of compromise. And litigation favors federal authority in federal courts. So the status quo persists.

The Path Forward

Eventually, courts will rule on California's law. Probably within the next year or two. DHS will almost certainly win the preliminary injunction. Then the case will proceed through the courts. Eventually, either the Ninth Circuit or the Supreme Court will settle the question.

My prediction: DHS wins on Supremacy Clause grounds. Courts will decide that states cannot impose operational requirements on federal law enforcement, especially in areas like immigration where federal authority is traditionally exclusive. The ruling will apply nationally, blocking all state anti-masking laws.

That outcome would be legally defensible. Federal law does trump state law in immigration matters. Courts do defer to federal security expertise. The precedent would be consistent with federal authority over immigration.

But it would be a political defeat for accountability advocates. It would establish that the federal government can operate without the transparency most Americans want. It would prioritize operational convenience over public trust.

The long-term solution probably requires federal legislation, not litigation. Congress will eventually have to decide whether to allow or ban state anti-masking laws. That's a political question, not a constitutional one. And that's where the real answer lies.

FAQ

What is the No Secret Police Act and why was it created?

The No Secret Police Act is a California law that restricts federal law enforcement officers from wearing face-covering masks while performing official duties. It requires clear, visible identification including name and badge. The law was created in response to public concern about unidentifiable federal officers conducting immigration raids, particularly after a legislator was killed by someone impersonating law enforcement.

How does ICE justify masking federal agents?

ICE argues that agent identification creates safety risks through increased death threats and doxxing of officers and their families. The agency claims threats against ICE agents have increased 8,000 percent and assaults have increased 1,300 percent, necessitating anonymity protections. However, these figures are presented with limited documentation and methodology.

What constitutional arguments does the Department of Homeland Security make against state anti-masking laws?

DHS primarily argues that state anti-masking laws violate the Supremacy Clause because immigration enforcement is a federal function that states cannot regulate. The agency also claims officers have First Amendment rights not to be identified and Fifth Amendment due process protections. However, these constitutional arguments are generally considered weaker than the Supremacy Clause claim.

Why haven't federal anti-masking bills passed Congress?

Federal anti-masking bills have been introduced in both the House and Senate, but neither has advanced. Republican majorities in both chambers have blocked these bills, with the Trump administration and DHS opposing them. Border security advocates argue that any restriction on ICE operations undermines immigration enforcement effectiveness.

How many states have introduced anti-masking legislation?

At least 15 state legislatures have introduced anti-masking bills since California's law passed. Recent states introducing legislation include Maryland, Vermont, Washington, and Georgia. Los Angeles passed a city-level ordinance, and St. Paul is considering one. Minnesota has announced plans to introduce legislation in the upcoming legislative session.

What does the preliminary injunction decision mean for implementing anti-masking laws?

A preliminary injunction determines who operates under what rules while a case is being litigated. If a judge grants DHS's request for a preliminary injunction, California's law is blocked while the case proceeds, allowing ICE to continue masking. If the judge denies it, ICE must comply with the law while litigation continues. The preliminary injunction decision significantly shapes the practical impact of anti-masking laws during the legal process.

How do other democracies handle police identification requirements?

Most developed democracies explicitly require visible police identification. The United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, Australia, and France all require officers to display visible identification including name, rank, and agency. These countries have concluded that public accountability through visible identification is more important than operational convenience, and their law enforcement agencies operate effectively with these requirements.

What would happen if California's law is upheld by courts?

If California's law survives legal challenge, it becomes a model for other states to follow. Other state anti-masking laws would likely be upheld under the same legal reasoning. Federal law enforcement would need to adapt operations to display identification, though the core functions of immigration enforcement would continue. However, courts would likely establish that states can impose identification requirements on federal operations, significantly limiting federal authority in this area.

Could federal legislation override state anti-masking laws?

Yes. Congress could pass federal legislation explicitly protecting federal law enforcement authority to mask or explicitly allowing states to impose identification requirements. That federal legislation would supersede all state laws under the Supremacy Clause. However, Congress has not moved on this issue, with Republican majorities opposing anti-masking legislation and Democratic priorities focused elsewhere.

What alternative compromises could resolve this conflict?

Possible compromises include allowing masked officers to display names, requiring body cameras to compensate for anonymity, limiting masking to specific high-risk situations, or requiring identification cards visible from a distance. However, DHS has shown little willingness to negotiate, preferring litigation to maintain the status quo. These compromises would satisfy accountability concerns while addressing officer safety worries, but they would require both sides to negotiate in good faith.

Key Takeaways

- California's No Secret Police Act bans federal officer masking, but DHS sued on constitutional grounds with the case still pending

- At least 15 states have introduced anti-masking legislation since California's law, but Congress has stalled on federal action

- DHS argues masking is necessary due to 8,000% increase in threats against ICE agents, though documentation and verification remain limited

- The Supremacy Clause likely favors DHS in court, potentially blocking state laws and establishing federal authority over immigration operations

- International democracies universally require visible police identification, setting different standards than current American federal law enforcement practices

Related Articles

- How Communities Respond to Immigration Enforcement Crises [2025]

- ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]

- Inside Minneapolis ICE Shooting and Protest Response [2025]

- State Attorneys General Fight Trump: The Last Constitutional Check [2025]

- ICE Agents Doxing Themselves on LinkedIn: Privacy Crisis [2025]

- When Federal Enforcement Changes Everything: How Communities Adapt [2025]

![Why ICE Masking Remains Legal Despite Public Outcry [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-ice-masking-remains-legal-despite-public-outcry-2025/image-1-1769353543571.jpg)