Introduction: The Hidden Surveillance Infrastructure

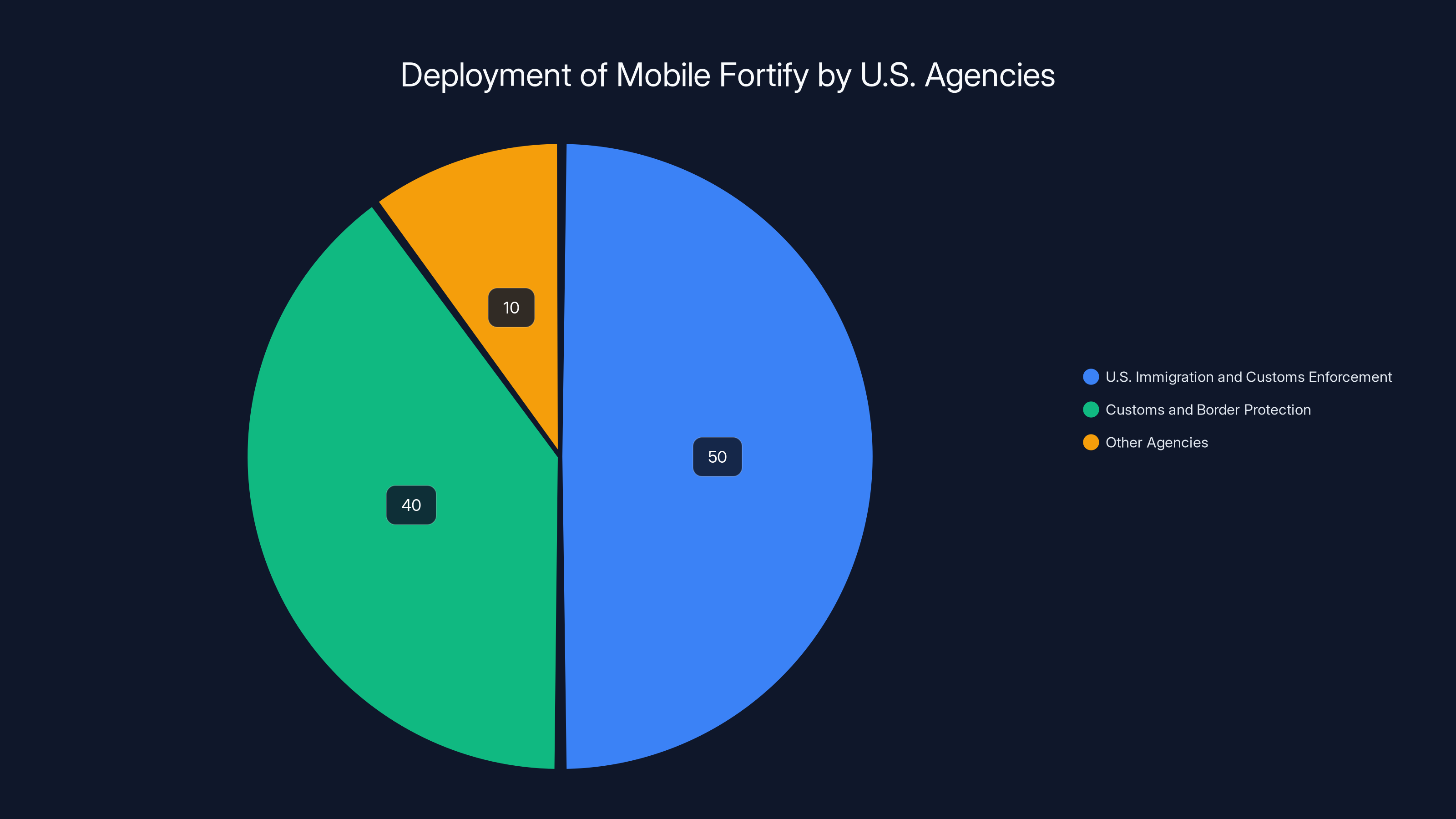

Imagine walking through an airport, entering a federal courthouse, or standing in a line at a border crossing. You probably assume your face is just another one in the crowd. But for the last two years, federal immigration agents have been scanning faces using a tool most Americans didn't know existed. That tool is called Mobile Fortify, and it's built into handheld devices used by agents from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) every single day.

The story of Mobile Fortify isn't new. What changed in early 2025 was transparency. When the Department of Homeland Security released its AI Use Case Inventory, bureaucrats were forced to publicly acknowledge what they'd kept quiet: the vendor behind the app, the deployment dates, the scale of operations, and the fact that an AI impact assessment was still "in progress" despite the system being in "deployment" phase.

The vendor? A Japanese technology company called NEC that had been working with DHS since 2020 under a $23.9 million contract. The app itself? Designed to match faces, fingerprints, and identity documents in real-time, using databases that include TSA Pre Check and Global Entry records. The impact? Thousands of citizens and non-citizens have been identified—sometimes correctly, sometimes catastrophically wrong.

This isn't a theoretical problem buried in policy documents. Real people have been detained based on misidentifications. Appeals processes are still being built. Privacy safeguards are "in progress." Meanwhile, the system keeps running, scanning faces, making matches, and feeding data into government databases that influence everything from border crossing privileges to Global Entry status.

What makes Mobile Fortify significant isn't just what it does. It's what it represents: a government-wide shift toward field-level surveillance automation, powered by AI vendors with minimal public oversight. It's efficient, it's expanding, and it's operating in a regulatory gray zone where civil liberties protections lag far behind deployment realities.

Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what the documented problems tell us about facial recognition at scale in American law enforcement.

TL; DR

- Mobile Fortify is deployed: CBP activated it May 2024, ICE followed May 2025—both before completing required AI impact assessments

- NEC built it: The $23.9 million DHS contract reveals the vendor and scope of facial matching at "unlimited locations"

- It matches faces against government databases: TSA Pre Check, Global Entry, and other biometric records feed the system

- Accuracy problems are documented: At least one woman was detained based on two consecutive misidentifications

- Oversight is incomplete: Appeals processes, monitoring protocols, and civil rights impact assessments remain "in progress"

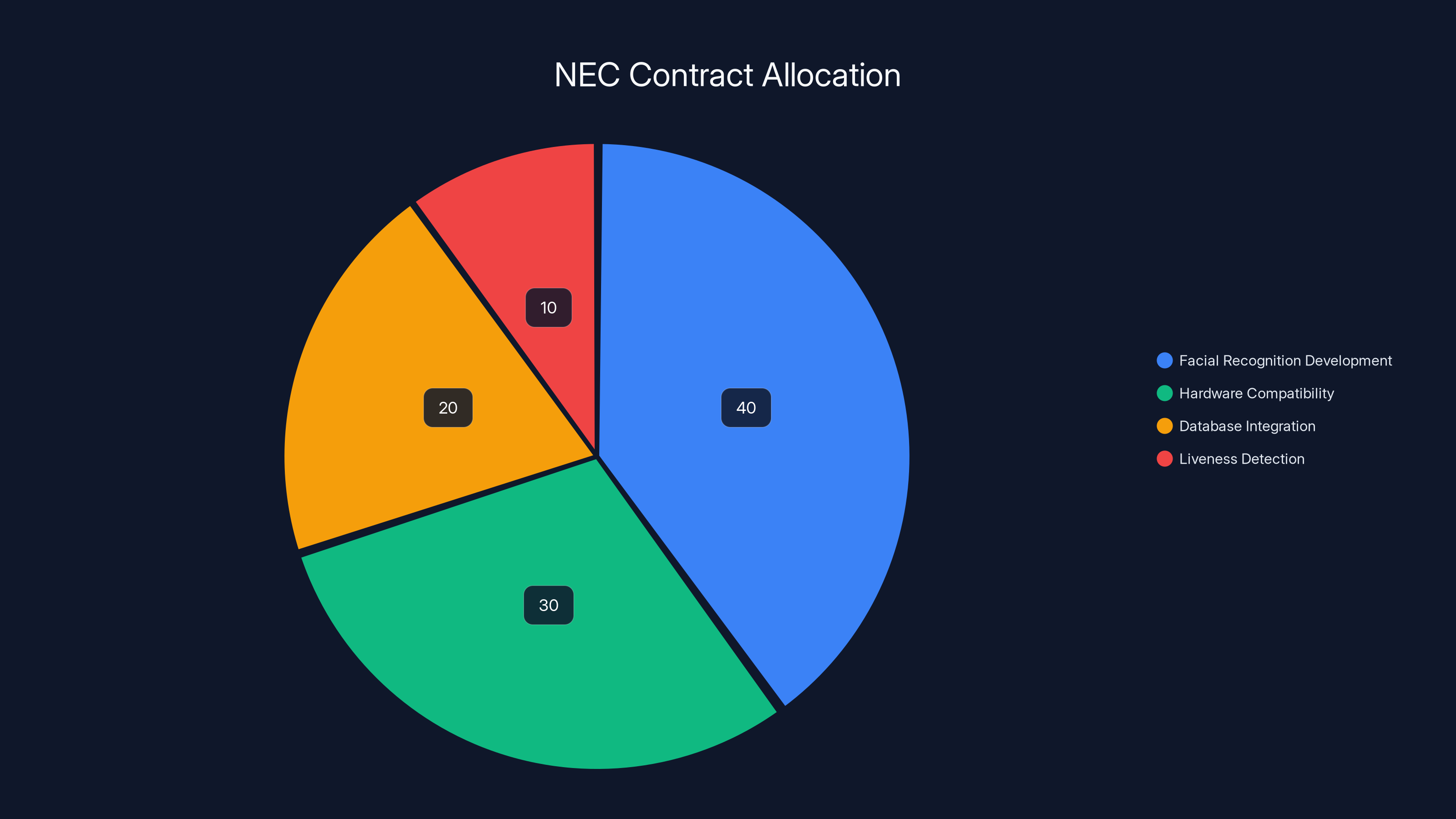

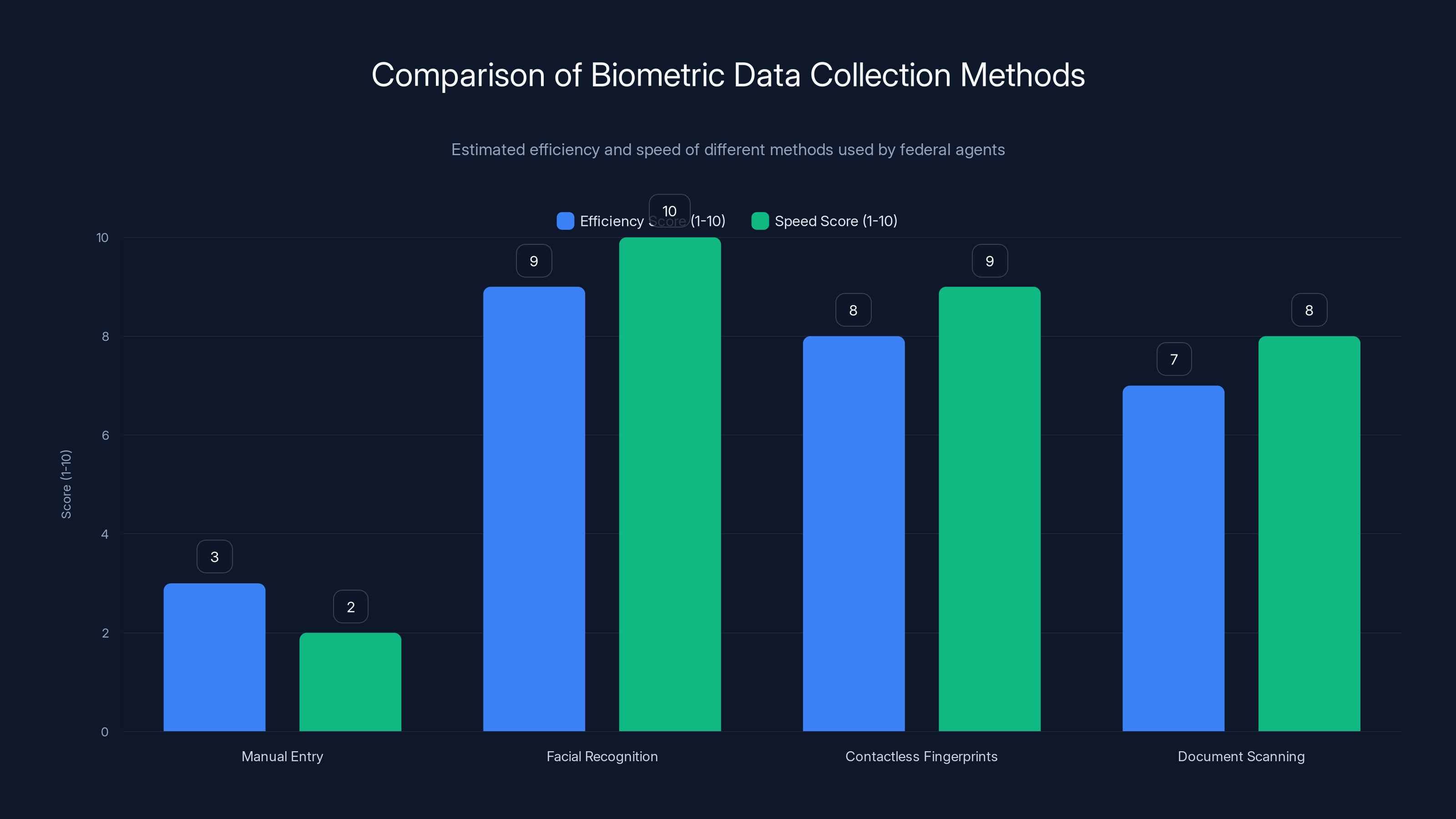

Estimated data shows the $23.9 million contract likely focused on facial recognition development (40%) and hardware compatibility (30%), with lesser emphasis on database integration and liveness detection.

What Mobile Fortify Actually Does

Mobile Fortify exists in the hands of federal agents because facial recognition at the border sounds efficient in theory. An agent encounters someone, runs their face through a database of millions of photos, and gets back a match—plus background information. No waiting for overnight database queries. No calling headquarters. No guesswork.

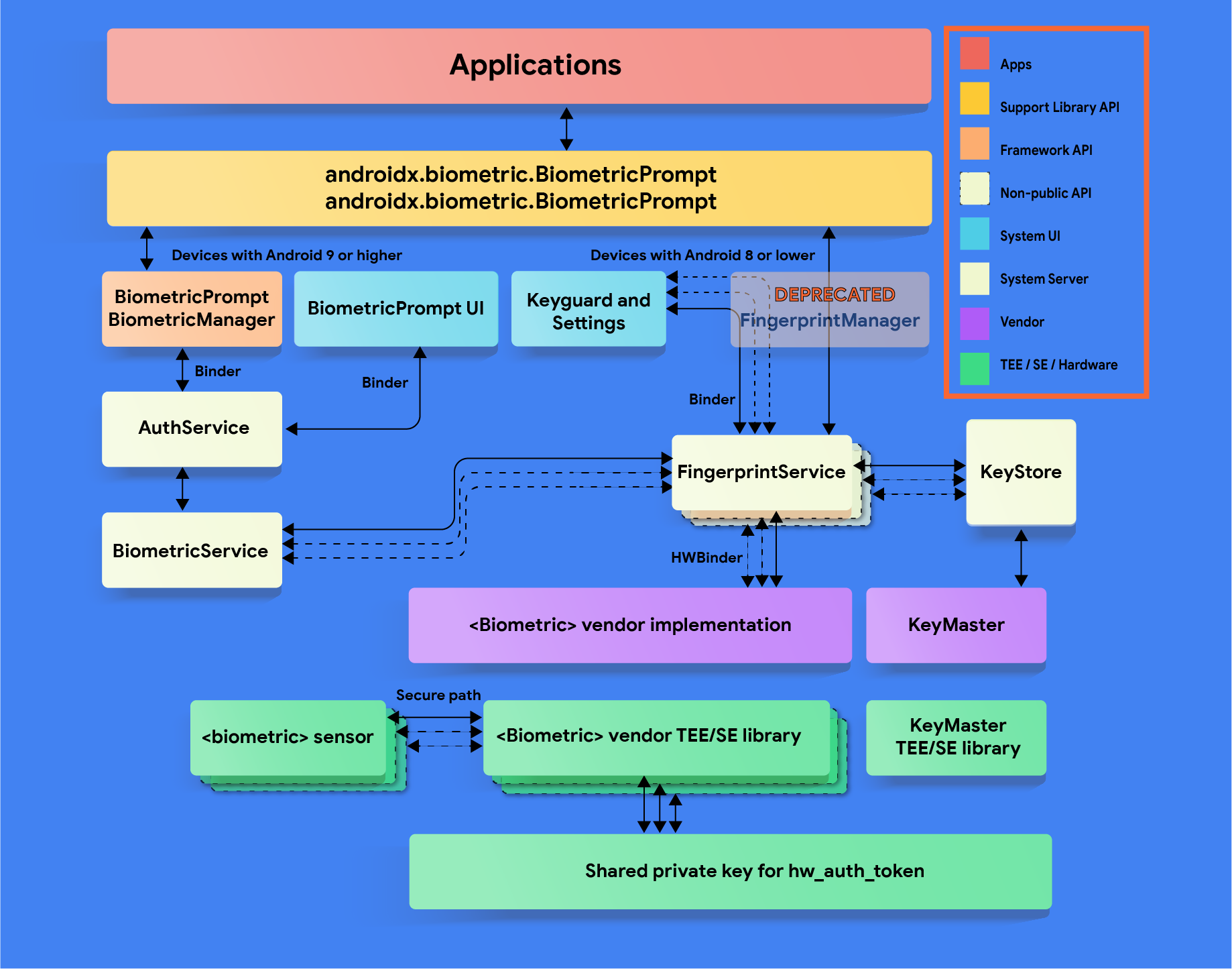

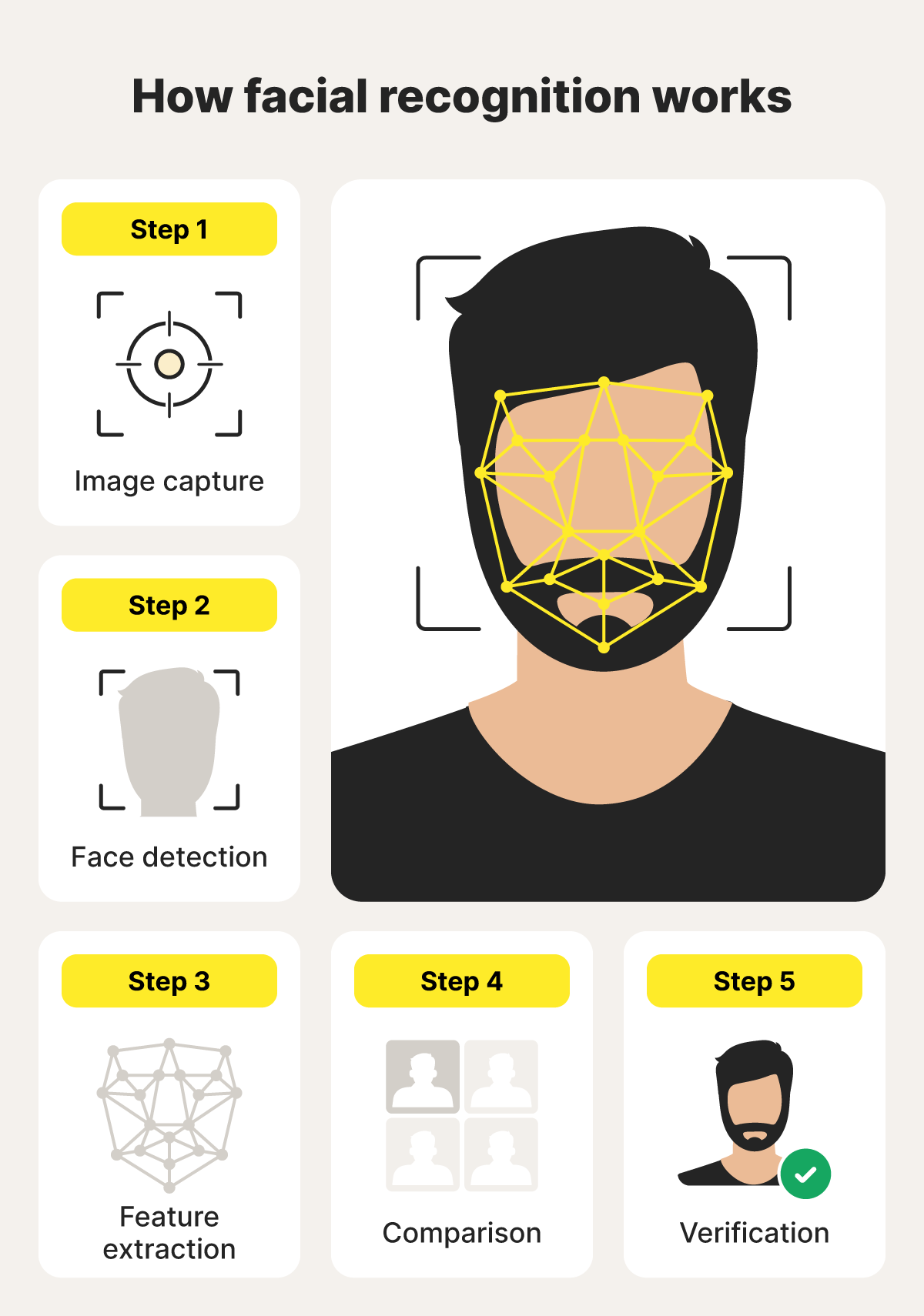

The technical capability is straightforward. The app captures three types of biometric data: facial images, contactless fingerprints, and photographs of identity documents like passports or state IDs. Once captured, that data transmits to CBP systems for matching against existing databases. The AI matches the submitted face against thousands or millions of reference photos, returns possible matches with confidence scores, and attaches biographic information to each potential hit.

ICE clarified in its inventory submission that the agency "does not own or interact directly with the AI models." Those models belong to CBP. What ICE controls is the app interface and the intake process—the moment where a detained person's face gets captured and sent upstream. ICE also uses the app to extract text from identity documents, enabling additional verification checks that bypass manual data entry.

The scale matters here. CBP's contract language specified that NEC's facial matching solutions would work on "unlimited facial quantities, on unlimited hardware platforms, and at unlimited locations." That's not hyperbole. It means the system wasn't designed for a single border crossing or a specific database. It was architected to work wherever CBP and ICE needed it, matching against however many faces they needed to match, without technical constraints.

What makes this different from older identification methods:

Previously, agents had to manually enter suspect information into government systems and wait for results. Facial recognition collapses that timeline to seconds. Previously, databases were siloed—border crossing records separate from immigration records separate from trusted traveler programs. Mobile Fortify federates those silos. Previously, a misidentification required someone noticing the error in a report. Now it's instantaneous feedback that often feels authoritative because it comes from a computer.

The app also captures context that traditional records lack. ICE noted it's particularly useful "when officers and agents must work with limited information and access multiple disparate systems." Translation: when a suspect has provided minimal documentation, when identity is unclear, or when someone crosses agency jurisdictions. Mobile Fortify fills gaps.

That efficiency creates a powerful incentive structure. Agents who can resolve a case in seconds instead of hours look more productive. Databases that match faster enable faster processing. Systems that reduce paperwork get endorsed by supervisors. Nobody wakes up wanting facial recognition to fail. They want it to work. And when it's convenient, when it's fast, when it solves problems, that momentum carries forward even when accuracy questions emerge.

The Vendor: NEC and the $23.9 Million Contract

NEC isn't a household name in the United States, but it's been operating in biometric technology for decades. The company offers a suite of facial recognition products under the brand name Reveal. On NEC's website, Reveal is marketed as capable of one-to-many searches against databases of any size, one-to-one verification, and liveness detection to prevent spoofing attacks.

The DHS relationship began formally in 2020, when NEC secured a contract valued at $23.9 million running through 2023. That contract covered "biometric matching products" that would function on "unlimited hardware platforms." The contract was extended and expanded from there. By the time Mobile Fortify went operational in May 2024 for CBP, the NEC relationship had evolved into a core infrastructure component rather than a one-off vendor engagement.

What's significant about the NEC contract isn't just the dollar amount. It's the scope language. Contracts written with specific technical constraints often fail in practice. "Limited locations," "specific database sizes," "named hardware platforms"—those create friction. Instead, DHS negotiated away those constraints entirely. The system could be deployed everywhere. It could match unlimited quantities of faces. It could run on any hardware CBP decided to use.

That's economically efficient for government. But it's also how surveillance infrastructure scales quietly. Nobody submitted an emergency expansion request. Nobody announced a jurisdiction change. The contract language was written broadly enough that deployment felt inevitable rather than exceptional.

NEC's existing facial recognition technology made it an obvious choice for this work. The company has decades of biometric systems experience and operates in multiple countries. For CBP and ICE, selecting an established vendor with proven capabilities meant lower development risk. They didn't need to build facial recognition from scratch. They could license proven technology and integrate it into Mobile Fortify.

What's notable is how long NEC's involvement remained unknown. The source WIRED story indicated that the vendor identity wasn't public until the AI Use Case Inventory disclosure. DHS had been operating the system for months before transparency requirements forced the company name into official documents. That's not unusual for government contracts, but it's worth noting: the surveillance infrastructure was functional and deployed while vendors remained anonymous to the public.

NEC declined to comment when asked about Mobile Fortify specifically. That's their prerogative, but it meant that the company's technical perspective on accuracy, limitations, or ethical concerns never entered public discourse. The narrative came entirely from government agencies, which have obvious incentives to minimize problems.

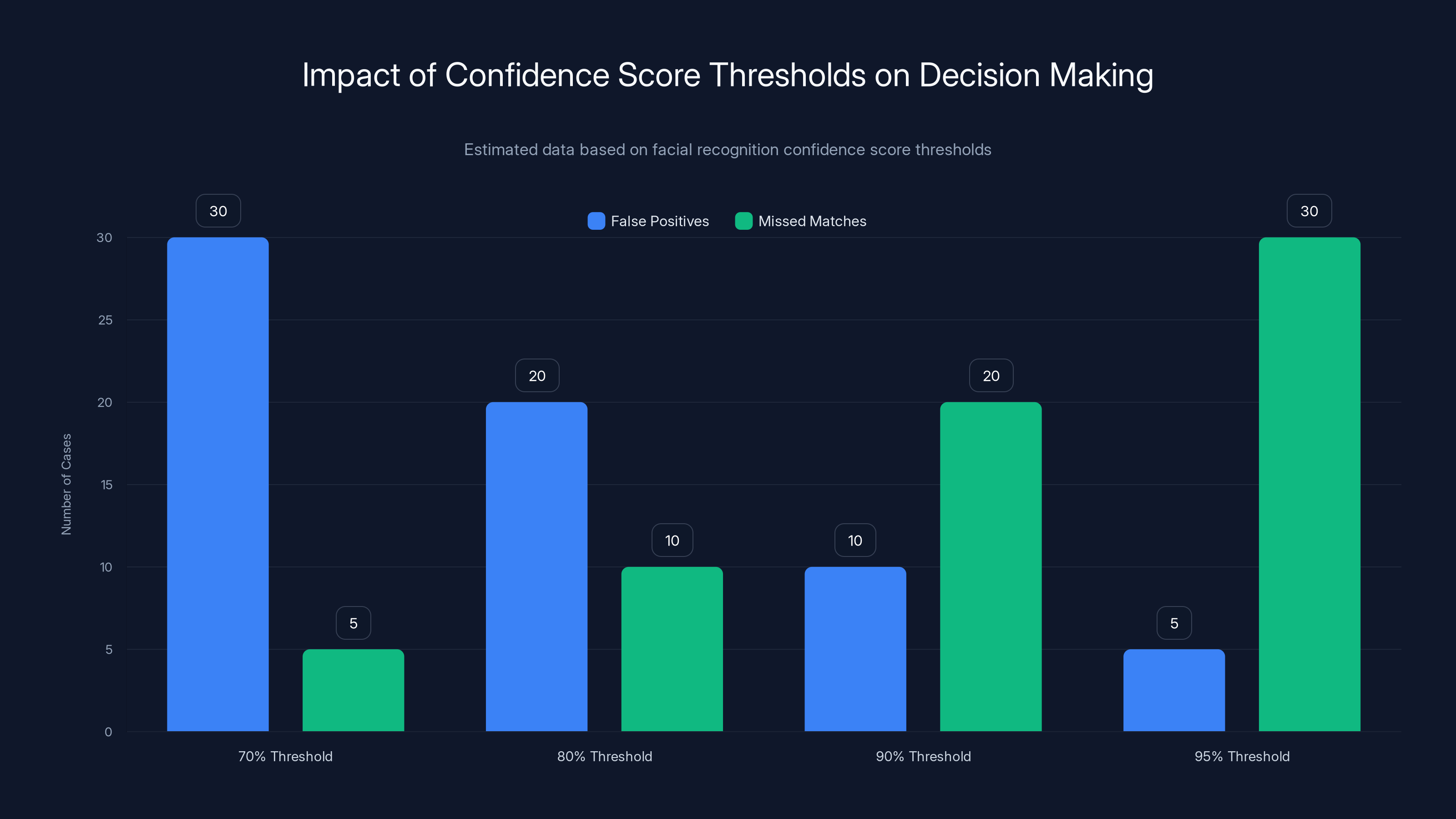

Estimated data shows that lower thresholds increase false positives, while higher thresholds increase missed matches. Balancing the threshold is crucial for accuracy.

Database Integration: Where the Faces Come From

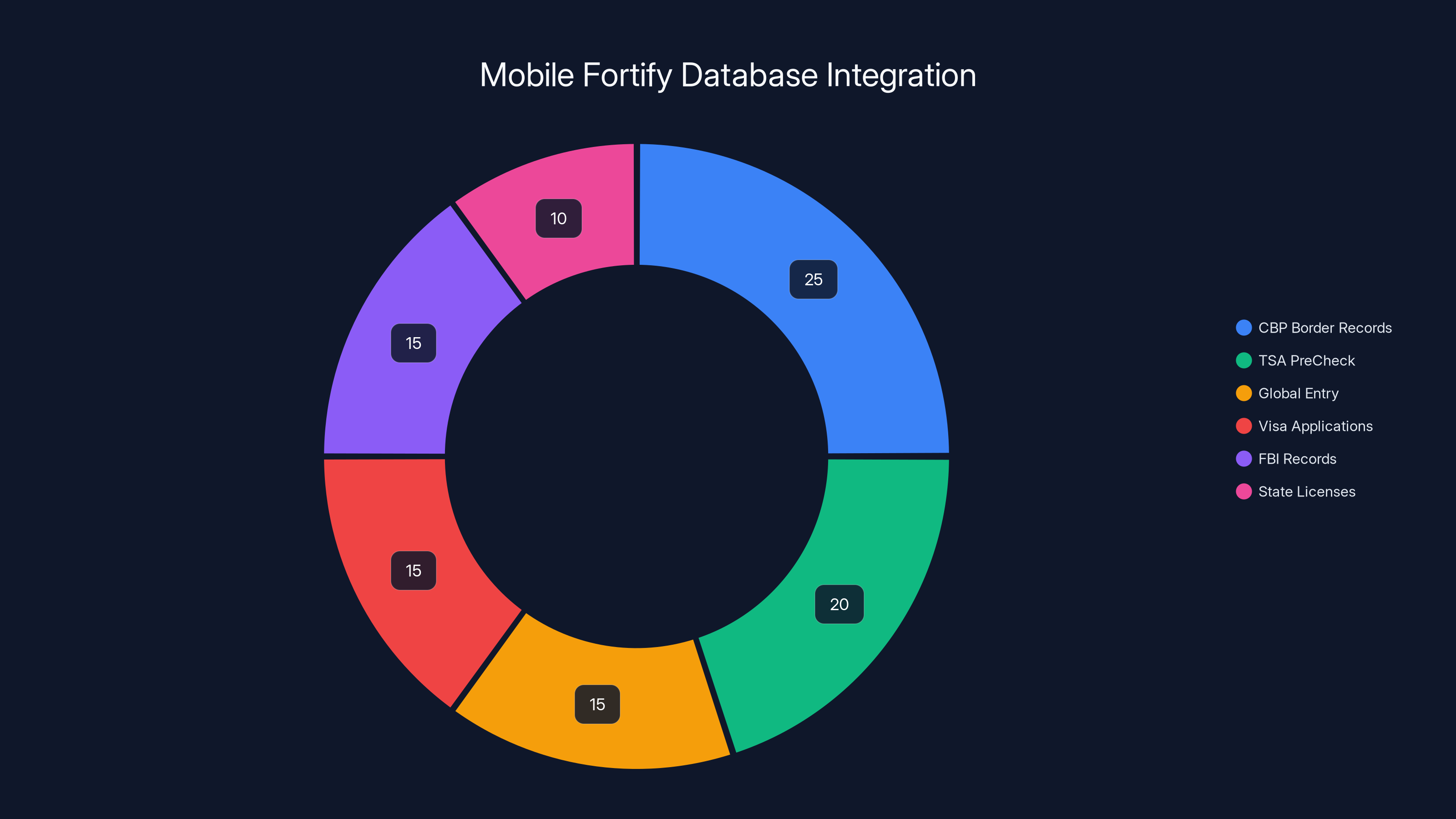

Mobile Fortify doesn't work in isolation. Its power comes from the databases it matches against. The DHS inventory revealed something important: CBP uses data from its Vetting/Border Crossing Information and Trusted Traveler Programs to "train, fine-tune, or evaluate the performance" of Mobile Fortify's AI models.

Trusted Traveler Programs sound innocuous. They're voluntary. You apply, pay a fee, get expedited screening. Most people think of them as conveniences—TSA Pre Check speeds up airport security, Global Entry speeds up customs. The programs do that. But they also create databases. Every trusted traveler applicant submits photos, fingerprints, background information, and travel history. Those databases are enormous and highly populated with people who have no reason to expect their photos would be used for field-level facial recognition by immigration agents.

The inventory didn't specify whether these databases were used for training the AI models, fine-tuning them, or evaluating performance. That distinction matters. Training means the model learned to identify faces using trusted traveler data. Fine-tuning means the model was adapted to work better with trusted traveler-style images. Evaluating performance means the system was tested using trusted traveler records.

All three are problematic for different reasons. If the model was trained on trusted traveler data, then it's optimized to match people who look like trusted travelers—which skews toward certain demographics, income levels, and travel patterns. If fine-tuned on that data, the system might perform better for frequent international travelers and worse for others. If evaluated on that data, accuracy metrics would be artificially high because the test set matches the training distribution.

CBP didn't clarify. When asked to specify which of the three (training, fine-tuning, or evaluation) applied to Mobile Fortify, the agency didn't respond.

The broader database integration includes:

Databases span multiple government agencies and contain overlapping information. A face that's in TSA Pre Check might also be in the FBI database, state driver's license databases, immigration records, and visa application archives. Mobile Fortify can theoretically match against all of them—if those databases are connected to the matching system. The integration happens at CBP's backend. When an agent submits a face through Mobile Fortify, the system checks multiple databases sequentially or in parallel, depending on integration architecture.

That creates an identity inference problem. If you've ever enrolled in TSA Pre Check, submitted a visa application, renewed a passport, or obtained a state ID, your face is likely in multiple government databases. Mobile Fortify can match you across all of them. You probably consented to one or two of those databases, but you didn't consent to them being linked for field-level immigration enforcement.

Citizens and non-citizens are in these databases without knowing they'll be subject to real-time facial matching by armed agents. That's not malice. It's how large systems work when transparency lags behind capability. You submit photos for a trusted traveler program expecting they'll be used for trusted traveler purposes. You don't expect them to be matched against every face an immigration agent photographs.

The inventory also mentions that ICE uses Mobile Fortify to extract text from identity documents. That means the system isn't just matching faces. It's reading documents and potentially cross-referencing that information. Document fraud detection is a legitimate security function, but coupling it with facial matching creates a comprehensive identification attack. An agent can capture a photo of a document and a face simultaneously, and the system can verify whether they match, all in seconds.

The Accuracy Problem: Misidentifications and Real Consequences

Facial recognition works differently than fingerprints or DNA. Those biometrics are binary—either the prints match or they don't. Facial recognition is probabilistic. The system returns possible matches with confidence scores, typically expressed as percentages or probability values. A 95% match might mean the system is very confident it found the same person. A 65% match means it's somewhat confident.

The problem is human behavior around those scores. An agent sees a 90% match and treats it as near-certain identification. They might not look further. They might not consider that the 90% score was generated by an AI trained on trusted traveler photos, tested on limited datasets, and deployed to matching faces of people in completely different contexts.

The documented cases reveal how this plays out. A Minnesota woman was detained after Mobile Fortify identified her—incorrectly—as matching someone in a government database. The system then apparently misidentified her again. Two consecutive false matches from the same system. She was detained based on this algorithmic error, released, and then had her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check revoked without clear explanation.

In another case documented in court filings, a person stopped by federal agents says an officer told them: "Whoever is the registered owner of this vehicle is going to have a fun time trying to travel after this." That officer apparently used facial recognition to identify them. Whether the identification was correct, we don't know from the filing. But the threat was made with the implicit authority of facial recognition matching.

These aren't edge cases if they're happening repeatedly. If one woman was misidentified twice, how many other misidentifications happened and were never caught? How many people were detained, questioned, or added to watchlists based on incorrect Mobile Fortify matches?

The technical accuracy problem:

Facial recognition accuracy varies significantly across demographic groups. This is well-documented in academic research and government audits. Systems trained on predominantly white faces often perform worse on Black and Asian faces. Systems trained on young faces often perform worse on elderly faces. Systems trained on frontal photos often perform worse on profile angles.

Mobile Fortify's training data source was trusted traveler databases and border crossing records. Those populations skew in particular directions demographically and spatially. An ICE agent using the app to identify someone encountered during a routine stop in Texas is matching that person against databases built from people who voluntarily applied for trusted traveler programs or crossed borders frequently. That's not a representative sample.

NEC's technology documentation indicates the system can be tuned for different accuracy thresholds. High sensitivity catches more potential matches but generates more false positives. High specificity reduces false positives but misses some real matches. Somewhere in that tradeoff, DHS set the threshold. We don't know where or why or whether it was optimized for civil rights or convenience.

The appeals process that's supposed to catch errors? It was "in progress" as of the inventory submission. That means people were being identified and detained under Mobile Fortify while the mechanism to appeal misidentifications was still being designed. That's backwards. You don't deploy a system that can restrict someone's movement and then build the appeals process later.

Deployment Timeline: When It Happened and Why It Matters

CBP went live with Mobile Fortify on May 1, 2024. ICE followed on May 20, 2024. Both agencies had been using it for months by the time the public even knew the system existed. The first reporting on Mobile Fortify appeared about a month after ICE deployment, in June 2024, from 404 Media. Until that story, there was no public knowledge that facial recognition in this form was being used by immigration agents in the field.

The timeline matters because it reveals the deployment priority. The Office of Management and Budget issued guidance before Mobile Fortify's deployment, stating that agencies should complete an AI impact assessment before deploying any "high-impact" AI use case. Both CBP and ICE flagged Mobile Fortify as high-impact in their inventory submissions. Both noted the system was already in "deployment" stage.

So they deployed first and assessed later. That's not how the bureaucratic process is supposed to work. The assessment is supposed to precede deployment. You identify risks, design safeguards, and build the systems before you start using the technology on actual people. Instead, Mobile Fortify went operational, and then the agencies started planning how to assess the impact.

ICE was particularly behind schedule. As of the inventory submission, ICE noted that "development of monitoring protocols" was "in progress," that an "AI impact assessment" was pending, and that an "appeals process" was still being designed. The agency had been using the system for nearly a year, and these basic safeguards hadn't been implemented.

CBP claimed to have "sufficient monitoring protocols" in place, which sounds better but came with no detail. What makes a monitoring protocol sufficient? Who reviews the monitoring data? What happens when monitoring reveals problems? Those questions didn't have answers in the public inventory.

Why the rush to deploy?

Border security isn't static. Migration patterns change, staffing fluctuates, political pressure intensifies. Once a system is available and functional, the incentive to use it immediately is enormous. Every day of delay feels like a security gap. Every agent without facial recognition capability feels like inefficiency.

CBP and ICE likely believed Mobile Fortify was necessary. Whether it actually improved security outcomes wasn't questioned because the system was already operational. The assessment phase became a box-checking exercise rather than a genuine evaluation of whether deployment made sense.

That rush also meant that early problems—like the consecutive misidentifications that led to detention—weren't caught during a controlled pilot phase. They were discovered during full-scale deployment, when agents were already using the system on thousands of people every day.

Estimated data shows varying confidence levels in facial recognition, with a notable percentage of misidentifications. This highlights the potential for errors in high-stakes situations.

The Database Sprawl: Connecting Systems That Weren't Meant to Be Connected

What makes Mobile Fortify powerful is the databases behind it. An older facial recognition system limited to one agency's records would be useful. Mobile Fortify's utility comes from federating databases across government.

Start with the obvious: border crossing records. CBP maintains photos and biometric data for everyone who crosses a U.S. border. That's millions of faces, including millions of American citizens who've traveled internationally. That database is the primary source for facial matches.

Add trusted traveler programs. TSA Pre Check applicants submit photos. Global Entry applicants submit photos. Each program has its own database, but CBP can apparently query both when Mobile Fortify makes a match request. That adds millions more faces to the searchable universe.

Now expand to visa applications. State Department maintains visa application photos for every non-citizen who's applied for a visa. That database is separate from CBP and ICE records, but if Mobile Fortify has integration agreements with State Department systems, it can search there too.

Add driver's licenses. Some states have integrated their DMV databases into federal systems. A photo in a state driver's license database becomes a potential match source for Mobile Fortify.

Add FBI records. The FBI maintains photos from arrests, mugshots, and other criminal justice interactions. If Mobile Fortify has access to FBI databases, it can match against criminal history photos.

Each connection is presumably authorized by some agreement between agencies. But the cumulative effect—where a single facial photograph can be matched against border crossing records, trusted traveler databases, visa applications, state IDs, and criminal history—creates a comprehensive identification system that no individual consented to.

The integration also creates governance nightmares. If a photo is incorrect in one database, that error cascades through Mobile Fortify. If someone's photo was misidentified in a state database, that mistake becomes Mobile Fortify's ground truth. If a visa application photo is outdated and no longer resembles the person, Mobile Fortify will try to match it anyway.

None of these problems are unsolvable. But they require deliberate design choices. Mobile Fortify was apparently designed for convenience first and accuracy second.

Civil Rights Implications: Who Gets Scanned and Why

Facial recognition is theoretically neutral. It doesn't inherently target specific demographics. But the way systems are deployed, trained, and used carries human choices that absolutely can discriminate.

Mobile Fortify is deployed almost exclusively by ICE and CBP, both primarily focused on immigration enforcement. That means the system's primary subjects are non-citizens, people suspected of immigration violations, and individuals in border areas. But facial recognition in law enforcement contexts affects everyone because you don't have to do anything wrong to be scanned.

An ICE agent can photograph anyone they encounter during a checkpoint, a transportation stop, or a community patrol. That photograph goes into Mobile Fortify. The system tries to identify the person, returns possible matches, and provides biographic information. The person who was photographed might not even know it happened.

That's functionally equivalent to being placed into a photo lineup without consent or knowledge. And unlike traditional lineups where someone reviews possible matches and makes a deliberate decision, Mobile Fortify returns algorithmic suggestions that often get treated as near-certain identification.

The impact falls disproportionately on certain communities. Border areas are subject to more enforcement. Communities with larger immigrant populations see more ICE operations. The people most likely to be subject to Mobile Fortify scanning are people who already have minimal trust in federal authority—often for good historical reasons.

There's also the database bias problem. If Mobile Fortify was trained or fine-tuned on trusted traveler data, then the system is biased toward people who can afford trusted traveler fees, who frequently travel internationally, and who have the resources and documentation to apply. That's a relatively privileged subset of the U.S. population. The system might work brilliantly for matching Global Entry members but perform significantly worse for people with less frequent travel histories.

When a system that's biased against a population is used to identify and detain members of that population, the injustice is compounded. The people least likely to have accurate facial recognition matches are the people most likely to be subjected to field identification by the system.

Regulatory Gaps: Why Oversight Is Behind Deployment

Mobile Fortify exposed a fundamental regulatory timing problem. Facial recognition technology moves faster than government oversight can process. By the time agencies are required to disclose the system, it's operational. By the time impact assessments are mandated, thousands of people have already been scanned.

The OMB guidance that required AI impact assessments before deployment came out before Mobile Fortify was operational, but it didn't have enforcement teeth. There was no penalty specified for deploying before completing the assessment. There was no requirement to halt operations if problems were discovered. The assessment became a compliance checkbox rather than a genuine gating mechanism.

ICE's response reveals the problem. The agency noted that appeals process development was "in progress." That means people were being identified and detained while the system to appeal identification was still being designed. If you were misidentified by Mobile Fortify in June 2024, you wouldn't have an appeals process yet. You'd have detention and no mechanism to contest the identification that caused it.

Congress hasn't passed specific legislation governing facial recognition in immigration enforcement. There are broader surveillance bills, privacy bills, and algorithmic accountability proposals, but nothing specifically addressing facial identification by ICE or CBP. That leaves the agencies to write their own rules under general OMB guidance.

When agencies set their own rules, the rules tend to prioritize agency interests. CBP determined that its monitoring protocols were "sufficient." Nobody else evaluated that sufficiency. No external body audited whether sufficient meant actually sufficient or merely procedurally defensible.

The Federal Trade Commission has jurisdiction over algorithm accuracy for consumer products, but government agencies are exempt from most FTC authority. The Department of Justice could potentially investigate civil rights violations, but that requires victims to come forward and prove harm—difficult when misidentifications happen in low-visibility immigration enforcement.

What legitimate oversight would look like:

Before deployment, an independent audit of Mobile Fortify's accuracy across demographic groups. Testing on representative populations, not just trusted traveler data. Clear documentation of confidence thresholds and what they mean.

Before deployment, transparent criteria for when officers use Mobile Fortify and when they don't. Some identifications are appropriate to verify with technology. Others might raise civil rights concerns. Clear guidance prevents discriminatory deployment.

Before deployment, an appeals process where misidentified individuals can challenge matches, access their file, and correct errors. That should exist from day one, not as an "in progress" item months after the system goes live.

During operation, regular audits by external parties. Not self-assessments by the agency using the system, but genuine independent evaluation of whether accuracy is holding up and whether civil rights protections are working.

None of this happened with Mobile Fortify. The system went operational with minimal oversight, documented misidentifications followed, and the regulatory infrastructure is still being built retroactively.

Estimated data shows CBP border records and TSA PreCheck as the most integrated databases in Mobile Fortify's facial recognition system.

The Confidence Score Problem: Why Percentages Feel Like Certainty

When facial recognition returns a match with an 87% confidence score, what does that actually mean? Most people intuitively understand it as "87% probability this is the same person." But that's not quite right. It's more complicated and potentially misleading.

Confidence scores in facial recognition come from the neural network's mathematical output. The network processes the input face and produces a score reflecting how similar it is to possible matches in the database. Higher scores mean higher similarity. A 95% score indicates greater similarity than a 75% score.

But that score doesn't directly translate to identification accuracy. It doesn't mean there's a 95% probability it's the same person. It means the neural network calculated a 95% similarity value. Those are different things, and the distinction matters when decisions depend on the score.

Consider the practical scenario: An ICE agent encounters someone, photographs them with Mobile Fortify, and the system returns a match with 88% confidence against a database photo. The agent has a few seconds to decide what to do. Do they detain the person? Do they ask for identification? Do they do deeper investigation?

The confidence score influences that decision. An 88% match feels authoritative. It sounds like the system is quite confident. But that 88% was generated by an AI trained on specific datasets, tested on specific conditions, and deployed in completely different conditions.

Mobile Fortify apparently allows threshold adjustment. An ICE supervisor could theoretically set the system to return matches only above 90% confidence to be more selective, or below 70% to be more inclusive. There's no public documentation of what threshold is actually set or who decides it.

If the threshold is set too high, the system misses real matches. If it's set too low, the system generates false positives that lead to detention of innocent people. The consecutive misidentifications of the Minnesota woman suggest the threshold is probably set too low—the system would rather err toward more matches than fewer.

Why this matters at scale:

When a confidence score is used by a single officer in a single case, the consequences are limited. If the match is wrong, one person might be detained for a few hours until identity is verified through other means.

When the same system is used by thousands of officers across thousands of cases, confidence score errors compound. If the system has a 5% false positive rate on its reported matches, and agents are using Mobile Fortify for thousands of field identifications monthly, then hundreds of detentions might be based on incorrect identifications every month.

The system feedback loop can also reinforce errors. If an agent trusts Mobile Fortify's match and conducts a more aggressive interview based on that trust, they might uncover unrelated issues—outstanding warrants, immigration violations—that have nothing to do with the original (incorrect) identification. The person gets detained not because of the facial match but because of what the aggressive interview discovered. The false facial match led to consequences, but those consequences appear to be about the unrelated issues, not the bad identification.

Over time, that feedback loop makes it harder to audit whether facial recognition is accurate, because the cases where it mattered get tangled with other enforcement actions.

The Case Study: From Misidentification to Travel Ban

The Minnesota woman's case illustrates how this works in practice. She was identified by Mobile Fortify during a federal agent interaction. The identification was wrong. The system apparently misidentified her again—two consecutive false matches from the same system.

She was detained based on these algorithmic errors. She was released after the misidentification was discovered, but then her Global Entry and TSA Pre Check were revoked. The revocation happened without clear explanation and without an appeals process, because no formal appeals process existed yet.

Her travel was restricted based on facial recognition errors made by an AI system she didn't consent to be scanned by, using databases she didn't know she was in. The errors were made during field enforcement, not border crossing or trusted traveler interactions. Yet they cascaded into consequences for her trusted traveler status.

This case has at least two implications. First, it demonstrates that Mobile Fortify misidentifications do happen and do lead to real consequences. Second, it shows how the system operates without adequate appeals mechanisms. A person who's misidentified has to discover the error, report it, find someone willing to correct the database, and get their status restored. That's a burden that shouldn't exist in a functioning system.

The officer who told another detained person "Whoever is the registered owner of this vehicle is going to have a fun time trying to travel after this" was apparently making a threat based on facial recognition technology. Whether that identification was correct is unknown, but the implication was clear: facial recognition was used as a basis for threatening someone's future travel.

That's how surveillance technology gets normalized. Each individual use seems defensible. Officer makes an identification, confirms it's correct, detains the person for legitimate reasons. But when you zoom out and look at the system in aggregate—facial recognition used to scan thousands of people, make matches that carry weight in officers' minds, threaten travel privileges based on those matches—it becomes a comprehensive surveillance infrastructure.

Consent and Knowledge: What People Don't Know

Most Americans have no idea Mobile Fortify exists. They don't know their faces might be scanned by it. They don't know the app can match their photos across multiple government databases. They don't know facial recognition identification can affect their travel privileges.

Consent is theoretically involved at the database level. You voluntarily apply for Global Entry, so you consented to Global Entry's photo collection. You voluntarily traveled across a border, so your photo was collected by CBP at the border. You voluntarily obtained a state driver's license, so your photo was taken at the DMV.

But that's consent for those specific purposes. You didn't consent to your TSA Pre Check photo being used for real-time immigration enforcement facial matching by ICE agents in the field. You didn't consent to your border crossing photo being matched against other databases you've never heard of. You consented to discrete functions, not to system integration.

Mobile Fortify represents a type of consent problem that's increasingly common in large systems: function creep. You consent to A, but your data gets used for A, B, and C. Each individual use might be technically consistent with the original consent, but the aggregate use is something you never agreed to.

Privacy law hasn't caught up to this. The Privacy Act theoretically restricts how government agencies use personal data, but it has broad exceptions and weak enforcement. Agencies can cite national security to justify information sharing. They can claim efficiency to justify system integration. Mobile Fortify probably complies with the Privacy Act as written, but that tells you more about the Privacy Act's limitations than about whether the system respects privacy.

If Mobile Fortify users were required to inform people that their photos are being scanned and used for identification, that would at least be transparent. An ICE agent would tell a person: "I'm going to take your photo and run it through facial recognition to verify your identity." That would enable the person to assert privacy interests, decline if possible, or at least know what's happening.

There's no indication that happens. Facial recognition is apparently used without informing the person being scanned. They find out later if they're misidentified and detained.

Estimated data shows that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection are the primary users of Mobile Fortify, accounting for 90% of its deployment. Estimated data.

Technological Limitations and Future Risk

Facial recognition technology is improving, but it remains imperfect and potentially dangerous. Understanding its real limitations is important context for how Mobile Fortify should be deployed—if at all.

Liveness detection limitations: The inventory mentions that Mobile Fortify can detect liveness, meaning it can theoretically distinguish between a real face and a photo or video. That's useful for preventing spoofing attacks. But liveness detection can be fooled. Sophisticated attackers can create silicone masks or 3D-printed heads that fool some liveness detection systems. As the technology improves, so do the attacks.

Aging and appearance changes: Facial recognition works best when the probe image and the database image were taken under similar conditions, at similar ages, and with similar lighting and angles. A 20-year-old's face in a database might not match their face at 35, especially if they've experienced significant life changes. Mobile Fortify matches against databases that include photos taken years apart. A trusted traveler photo from 2015 might not match the same person in 2024 because people age.

Demographic performance variance: This is the well-documented problem. Facial recognition accuracy varies significantly across demographic groups. Systems trained on predominantly light-skinned faces perform worse on darker-skinned faces. Systems trained on particular age ranges perform worse outside those ranges. Mobile Fortify was apparently trained on trusted traveler data, which has particular demographic characteristics. Performance on people outside that demographic distribution is likely worse.

Environmental factors: Outdoor lighting, angles, weather, and distance all affect facial recognition. Mobile Fortify is used by ICE agents in the field, often under non-ideal conditions. A nighttime arrest, a photo taken at a distance, harsh outdoor lighting—all of these degrade accuracy compared to the controlled conditions where the system was tested.

Database quality issues: Facial recognition is only as good as the database it's matching against. If database photos are outdated, low-quality, or incorrectly labeled, matches will be wrong. We don't know the database maintenance practices at CBP. Are outdated photos removed? Are mislabeled photos corrected? Probably not at the scale and speed that would maintain high accuracy.

As Mobile Fortify continues operating, each of these limitations remains a source of error. Some will cause false negatives—real criminals aren't identified. Others will cause false positives—innocent people are misidentified. The documented cases suggest false positives are the current problem.

Policy Solutions: What Could Actually Fix This

If facial recognition in immigration enforcement is going to exist, what policies would make it less dangerous?

Transparency first: Publish accuracy metrics by demographic group. Make the confidence scores meaningful by explaining what they actually represent. Disclose the training data sources and database composition. Let people know when facial recognition is being used on them.

Threshold adjustment: Allow jurisdiction-specific threshold changes based on local needs and context. Border crossings might use different thresholds than interior enforcement. The confidence threshold should be set to prioritize avoiding false positives, not maximizing convenience.

Appeals process from day one: Before facial recognition is deployed on anyone, build the appeals mechanism. Not as an "in progress" item, but as a functional system from the first day. Misidentified people should have a clear, simple way to challenge their identification and correct their record.

Regular external audits: Not self-assessment. Independent evaluation of whether accuracy is holding up, whether false positives are being caught, whether systems are being used appropriately. Publish results, including failures and problems.

Training and accountability: Officers using Mobile Fortify should be trained on its limitations, confidence scores, and how to handle uncertain matches. They should be accountable for using the technology appropriately—which means not detaining people based solely on facial recognition without corroboration.

Consent and notice: People being scanned should be informed of it and told that their photo is being used for identification. They should have a right to decline if legally possible, or at least to know it's happening.

Data minimization: Only use facial recognition when necessary for security purposes. Not for every encounter, not as a routine part of all interactions, but specifically when legitimate identification is needed and other methods aren't available.

Sunset clauses: Facial recognition technology is evolving rapidly. Systems deployed in 2024 might be obsolete or dangerous in 2029. Periodic reauthorization requirements would force agencies to justify continued use based on current evidence.

None of these are implemented with Mobile Fortify currently. Most weren't contemplated in the design phase. Several are still "in progress" years after deployment.

Precedent and Trajectory: Where This Goes From Here

Mobile Fortify is not the first facial recognition system deployed by federal law enforcement. It's one of many. The FBI has been using facial recognition for years through its integrated automated fingerprint identification system. Facial recognition at airports is expanding. State and local police departments use it for investigations.

What Mobile Fortify represents is the normalization of field-level facial recognition. Not as an investigative tool for after-the-fact identification, but as a real-time identification mechanism in the hands of officers during routine enforcement. That's a meaningful difference and a dangerous precedent.

Once one agency deploys field-level facial recognition successfully, others want to adopt it. Border patrol sees the efficiency gains, so interior enforcement gets the same technology. Interior enforcement proves useful, so local law enforcement starts requesting it. Each jurisdiction sees efficiency and requests an expanded system.

The regulatory environment lags behind this trajectory. By the time Congress considers facial recognition legislation, a dozen agencies are already using it in dozens of ways. By the time civil rights organizations challenge deployments in court, thousands of people have already been affected.

The trajectory suggests that without deliberate intervention, facial recognition in law enforcement will become routine, normalized, and extensive. It will become the default identification method rather than the exception. And the evidence we have so far—documented misidentifications, incomplete appeals processes, insufficient oversight—suggests it will do so with significant civil rights costs.

What happens depends partly on government action. If OMB guidance is strengthened to actually prevent deployment before assessment, if Congress passes specific facial recognition regulations, if courts rule that certain deployments violate civil rights, then the trajectory can be altered.

But the default trajectory, without intervention, is toward more facial recognition, deployed more broadly, with civil rights protections playing catch-up.

Facial recognition offers the highest efficiency and speed compared to other biometric data collection methods, significantly reducing processing time at border crossings. Estimated data.

International Context: How the U.S. Compares

The United States isn't unique in deploying facial recognition for immigration enforcement. But the approach differs by country in ways that matter.

China has been a leader in facial recognition deployment, using it extensively for public security, border control, and surveillance of minority populations. The Chinese system is more extensive and more surveillance-focused than Mobile Fortify, but it also operates with less legal restraint.

Europe has generally taken a more restrictive approach. The GDPR limits biometric data processing, including facial recognition, and requires compelling justification for law enforcement uses. Several European countries have restricted police use of facial recognition or implemented strict accuracy standards and oversight requirements.

Canada and Australia have deployed facial recognition at borders but with different legal frameworks and oversight mechanisms than the U.S.

What's notable about Mobile Fortify is that it operates with minimal legal constraint and minimal transparency—more like early Chinese systems than like systems in countries with stronger privacy protections.

The international trajectory suggests that countries with stronger regulatory environments are moving toward tighter restrictions on facial recognition, especially for law enforcement. The U.S. is moving in the opposite direction, deploying systems with minimal upfront assessment and building oversight structures afterward.

That's not a sustainable long-term approach. Either Mobile Fortify-style systems will face increasing legal challenges and constraints, or the regulatory environment will shift to accommodate them. What won't happen is the current situation persisting indefinitely—operational facial recognition systems with incomplete oversight and documented problems.

The Human Cost: Real People in Real Situations

Behind the policy debates and technology discussions are actual people experiencing consequences. The Minnesota woman who was misidentified twice by Mobile Fortify, detained based on algorithmic errors, and then had her trusted traveler status revoked without clear process. The person told by an ICE officer that they'd "have a fun time trying to travel" based on facial recognition. Every person photographed by Mobile Fortify without knowing it, their face matched against databases they never agreed to be in, potential matches returned to officers who might not understand the system's limitations.

These aren't abstract harms. They're disruptions to people's lives, restrictions on their movement, and uncertainty about their legal status. For some, it's the difference between coming home to family or being detained. For others, it's the difference between working or losing work authorization. For still others, it's simply the indignity of being identified by a system that often gets it wrong.

The people most likely to be affected are those with the fewest resources to fight back. Non-citizens subject to immigration enforcement have limited legal rights to challenge identification. People who've been detained are less likely to have the resources to pursue appeals or legal action. Communities with high ICE presence experience Mobile Fortify as an intrusion and a threat.

When facial recognition is deployed in this context, with this population, and with this level of accountability, it becomes a tool of power imbalance. The government gets perfect information, or what it believes is perfect information from technology. The person being identified gets uncertainty and potential consequences.

The question isn't whether facial recognition can work technically. It clearly can match faces under many conditions. The question is whether it should be deployed in ways that create such power asymmetry, such potential for harm, and such minimal recourse for people who are wrongly identified.

Looking Forward: What Changes Are Possible

Mobile Fortify is operational now. The system is deployed, agents are using it, and people are being identified by it. But that doesn't mean the current situation is inevitable or permanent.

Congressional action is possible. Congress could pass specific legislation governing facial recognition in immigration enforcement. That could require completed assessments before deployment, mandatory appeals processes, accuracy standards, transparency requirements, and external audits. Other countries have done this. The U.S. could too.

Litigation could force change. Civil rights organizations are already documenting cases. If litigation establishes that facial recognition deployments violate constitutional rights or statutes like the Privacy Act, agencies would be forced to modify systems or halt deployment. That's how many privacy protections work—not proactively, but through legal challenge.

Executive action could tighten standards. OMB could strengthen its AI guidance to actually prevent deployment before assessment. The agency could require facial recognition to meet specific accuracy standards before deployment. The agency could mandate appeals processes and external audits. The next administration could take a different approach than the current one.

State action could restrict federal use. Some states are restricting local police use of facial recognition. States could also restrict ICE and CBP access to state databases, limiting the information available for facial matching. That would reduce the system's effectiveness and potentially lead to redesign.

Technology change could improve accuracy. Better facial recognition systems, trained on more diverse data, tested on more realistic conditions, could reduce false positives. That wouldn't solve the policy problems, but it would reduce the harm from errors.

None of these changes are guaranteed. The current trajectory is toward more deployment and more normalization. But the precedent of other technologies is that public pressure, litigation, and legislative action can alter that trajectory.

Mobile Fortify is a forcing function. The system is visible now, documented, and linked to real harms. That visibility creates pressure for change. Whether that pressure results in meaningful reform depends on action taken over the next few years.

Conclusion: The Surveillance Infrastructure We Get Without Asking

Mobile Fortify represents something important about modern surveillance: it doesn't arrive announced. There's no press conference declaring that facial recognition is now being deployed. No vote, no legislation, no public debate. One agency develops a system, another agency adopts it, and months later the public learns it exists only because transparency requirements force disclosure.

By that point, thousands of people have already been scanned. Misidentifications have already happened. Consequences have already been imposed. The system is operational, functioning, and embedded in law enforcement practice. At that point, shutting it down is difficult. Agencies have invested in the technology, trained on it, built processes around it. The system becomes path-dependent.

That's how surveillance infrastructure scales. Not through dramatic expansion, but through quiet deployment and normalization. Each system seems reasonable in isolation. Real-time identification seems useful. Automated matching seems efficient. Database integration seems sensible. But the aggregate—comprehensive facial recognition matched across government databases, deployed without completed assessments, used without clear oversight, subject to documented errors with minimal recourse—that aggregate becomes something different.

The choice ahead isn't whether to allow facial recognition generally. That choice is already made. Agencies are using it now. The choice is what kind of facial recognition system we accept. Do we require assessments before deployment, or afterward? Do we demand accuracy standards and demographic testing, or accept whatever the vendor built? Do we provide appeals mechanisms, or force people to sue for redress? Do we mandate transparency about when people are scanned, or do we allow covert identification?

Mobile Fortify's failures—the documented misidentifications, the incomplete oversight, the incomplete appeals process—suggest that without deliberate intervention, the default choice is to accept surveillance systems with minimal constraint and maximum convenience for government. That's not inevitable. It's a choice we make through action or inaction.

What happens next depends on whether the visibility of Mobile Fortify, the documented problems, and the clear risks create enough pressure for change. It depends on whether Congress, courts, or agencies decide that the current approach is unacceptable. It depends on whether civil rights advocates, technologists, and affected communities push hard enough to alter the trajectory.

The system is deployed now. But systems can be modified, constrained, or halted. The question is whether we act before facial recognition surveillance becomes so normalized that changing it seems impossible. That window is probably measured in years, not decades. Once the infrastructure scales further, intervention becomes harder. The time to ask whether we want this system, and in what form, is now.

FAQ

What is Mobile Fortify?

Mobile Fortify is a facial recognition application deployed by the Department of Homeland Security, specifically U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The app captures facial images, fingerprints, and identity documents from people in the field, then matches them against government databases including border crossing records, TSA Pre Check, and Global Entry databases to identify individuals in real-time.

How does Mobile Fortify work technically?

The system operates on handheld devices used by federal agents. An agent captures three types of biometric data: facial photographs, contactless fingerprints, and images of identity documents. This data transmits to CBP's backend systems, where artificial intelligence models perform one-to-many facial matching against multiple government databases. The system returns potential matches with confidence scores and associated biographic information within seconds, enabling field-level identification without waiting for manual database queries.

Who built Mobile Fortify and deployed it?

The application was built by NEC, a Japanese technology company, under a $23.9 million contract with the Department of Homeland Security that ran from 2020 to 2023. CBP deployed Mobile Fortify operationally on May 1, 2024, followed by ICE on May 20, 2024. The vendor's involvement wasn't publicly known until the DHS 2025 AI Use Case Inventory was released, which identified NEC as the system vendor.

What databases does Mobile Fortify search?

Mobile Fortify can match against CBP border crossing records, TSA Pre Check enrollment photos, Global Entry photos, visa application databases, and FBI criminal records—potentially state driver's license records depending on integration agreements. The system federates these previously separate databases into a single matching system, enabling facial recognition across databases that people never expected would be connected for immigration enforcement purposes.

What are the documented problems with Mobile Fortify?

At least one Minnesota woman was detained after being consecutively misidentified by Mobile Fortify, suggesting the system produces false positives that lead to real consequences. ICE noted that appeals processes for misidentifications are still "in progress" despite the system being operational for over a year. Monitoring protocols are incomplete, and an AI impact assessment was never completed before deployment, violating guidance from the Office of Management and Budget.

Why does accuracy matter for facial recognition in immigration enforcement?

Facial recognition returns probabilistic matches with confidence scores, not certain identifications. Errors occur systematically, varying significantly across demographic groups, environmental conditions, and age ranges. When ICE agents use facial recognition in field enforcement, they treat algorithmically generated matches as authoritative, leading to detention, questioning, and other consequences based on potentially incorrect identifications. Without strong appeals processes and careful threshold-setting, the system can devastate innocent people.

What oversight exists for Mobile Fortify?

Oversight is minimal and incomplete. CBP claims "sufficient monitoring protocols" without specifying what that means or what happens when problems are detected. ICE stated that monitoring protocols, appeals processes, and AI impact assessments are still "in progress" as of the 2025 inventory submission. No external agency audits the system's accuracy or civil rights impact. The only documented oversight comes from civil rights litigation by affected individuals.

Can people refuse to have their faces scanned by Mobile Fortify?

No clear mechanism exists for people to refuse facial recognition scanning by immigration agents. Agents can photograph faces during routine enforcement encounters without informing the person being scanned or obtaining explicit consent. People don't know Mobile Fortify exists, how it works, or that they might be identified by it. The system operates largely invisible to the public.

What should change about how facial recognition is used in immigration enforcement?

Effective reforms would require completed AI impact assessments before deployment, transparent accuracy testing across demographic groups, mandatory appeals processes for misidentifications, regular external audits, training for officers on system limitations, and informed consent or at minimum notice when facial recognition is being used on someone. Policy should also require specific justification for each facial recognition use rather than treating it as routine procedure.

Key Takeaways

- Mobile Fortify represents field-level facial recognition deployment without completed safety assessments, operating with documented misidentifications and incomplete appeals processes

- The system matches faces against multiple government databases including border records, trusted traveler programs, and criminal history, connecting previously separate biometric systems

- NEC, a Japanese technology company, built the system under a broad contract permitting deployment on unlimited platforms in unlimited locations with unlimited database quantities

- At least one person was consecutively misidentified by the system and wrongly detained, with their trusted traveler privileges revoked without clear appeals process

- Oversight is incomplete: monitoring protocols, appeals processes, and required AI impact assessments remain "in progress" despite over a year of operational deployment

- The system creates civil rights risks through demographic accuracy variance, bias in training data, deployment without informed consent, and minimal recourse for misidentified individuals

- Without deliberate intervention through legislation, litigation, or agency action, facial recognition in immigration enforcement will likely expand and normalize further

Related Articles

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

- How Reddit's Communities Became a Force Against ICE [2025]

- Big Tech's $7.8B Fine Problem: How Much They Actually Care [2025]

- Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]

- TikTok Censorship Fears & Algorithm Bias: What Experts Say [2025]

![Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/face-recognition-surveillance-how-ice-deploys-facial-id-tech/image-1-1769632688320.jpg)