Introduction: When Government Meets Decentralized Social Media

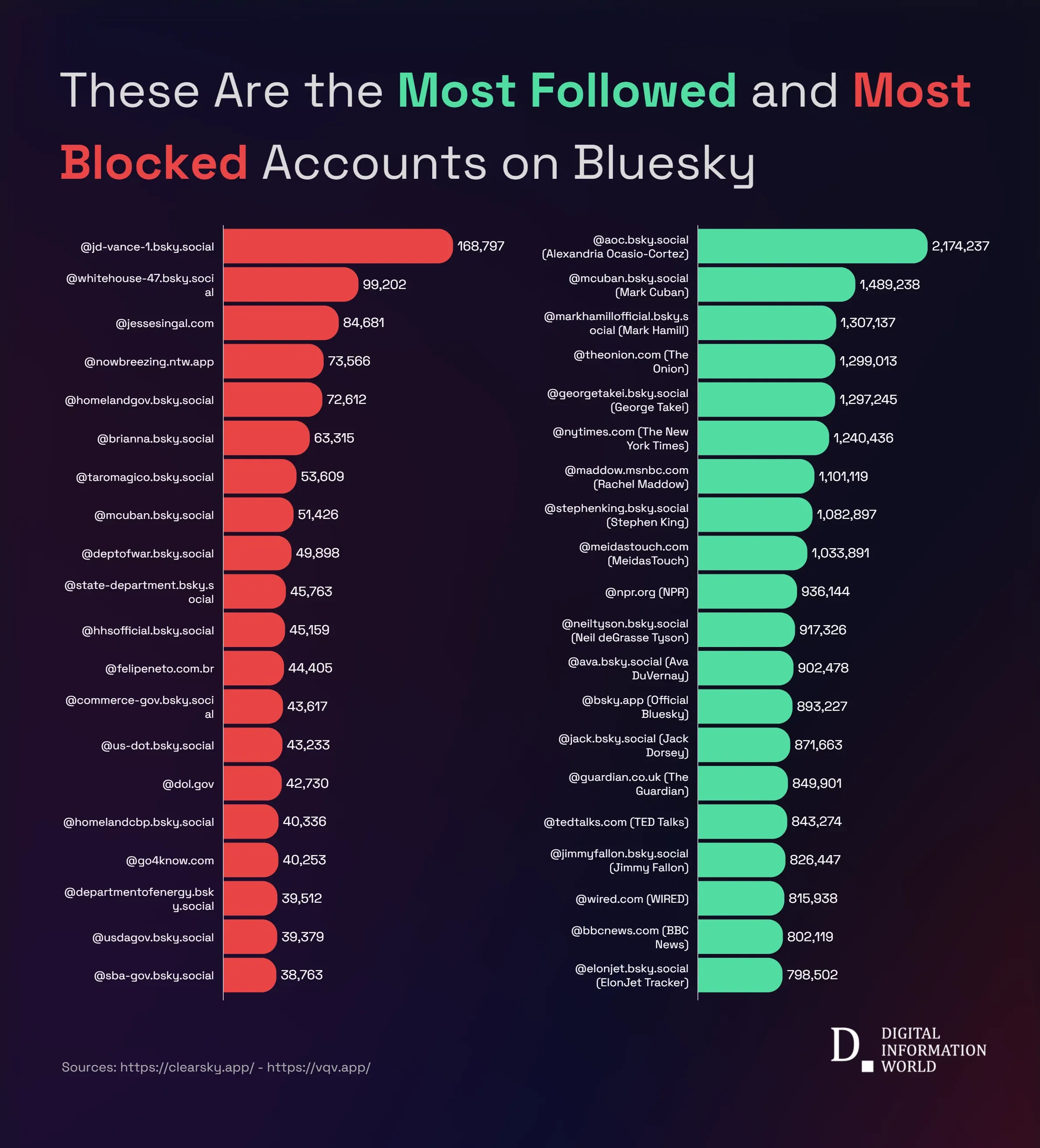

In late January 2025, something unusual happened on Bluesky, the decentralized social network that's been growing rapidly as an alternative to X (formerly Twitter). The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, better known as ICE, received official verification on the platform. What followed was unprecedented: the account rapidly climbed toward the top of Bluesky's most-blocked accounts list, trailing only Vice President J. D. Vance in blocking activity.

This moment crystallizes a fundamental tension in social media that we haven't fully reckoned with yet. We've built these massive platforms based on the assumption that verification, reach, and mainstream legitimacy are inherently good things. But Bluesky's rapid blocking response to ICE's verification reveals something deeper about how users actually want to interact with controversial institutions online.

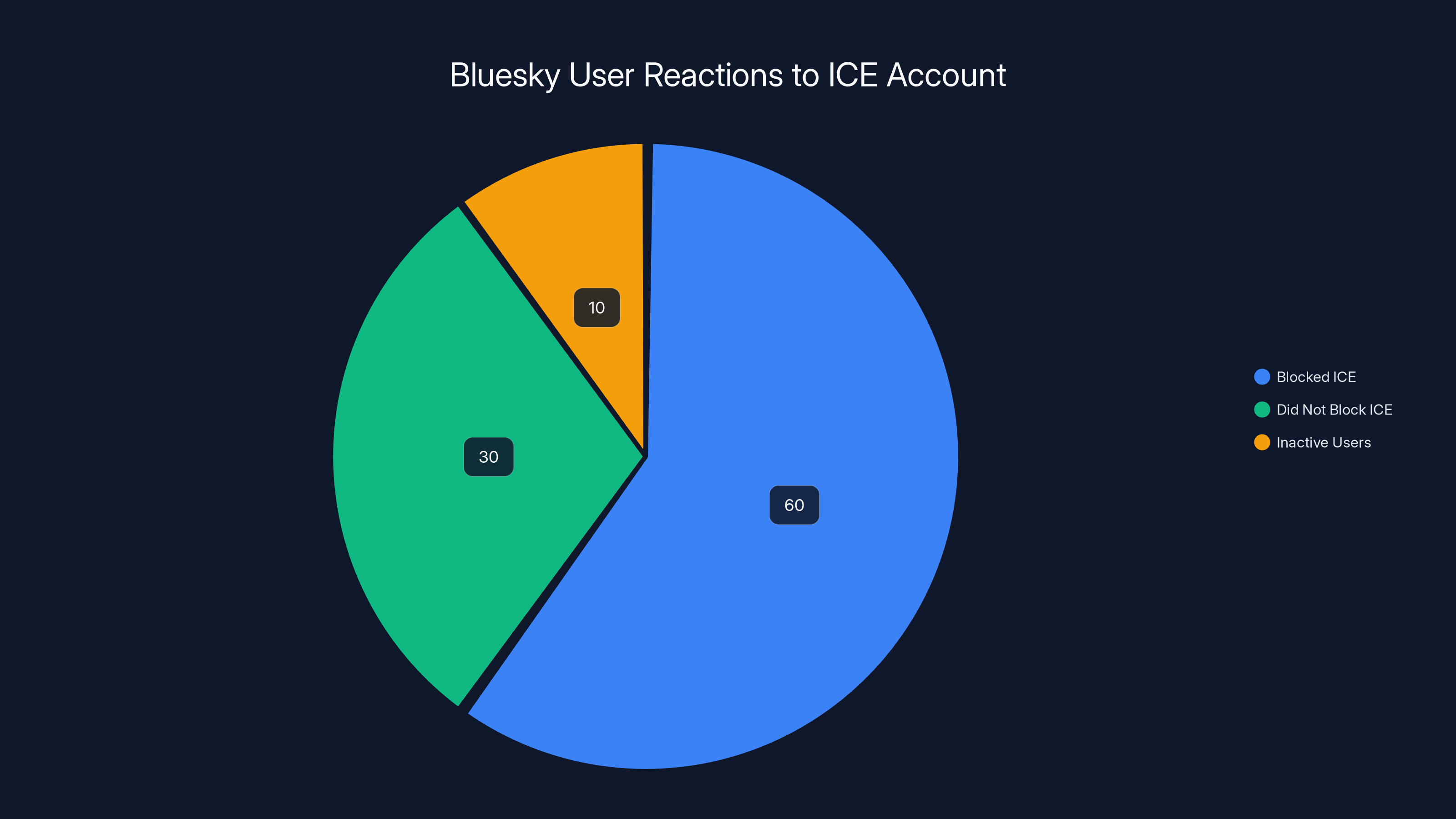

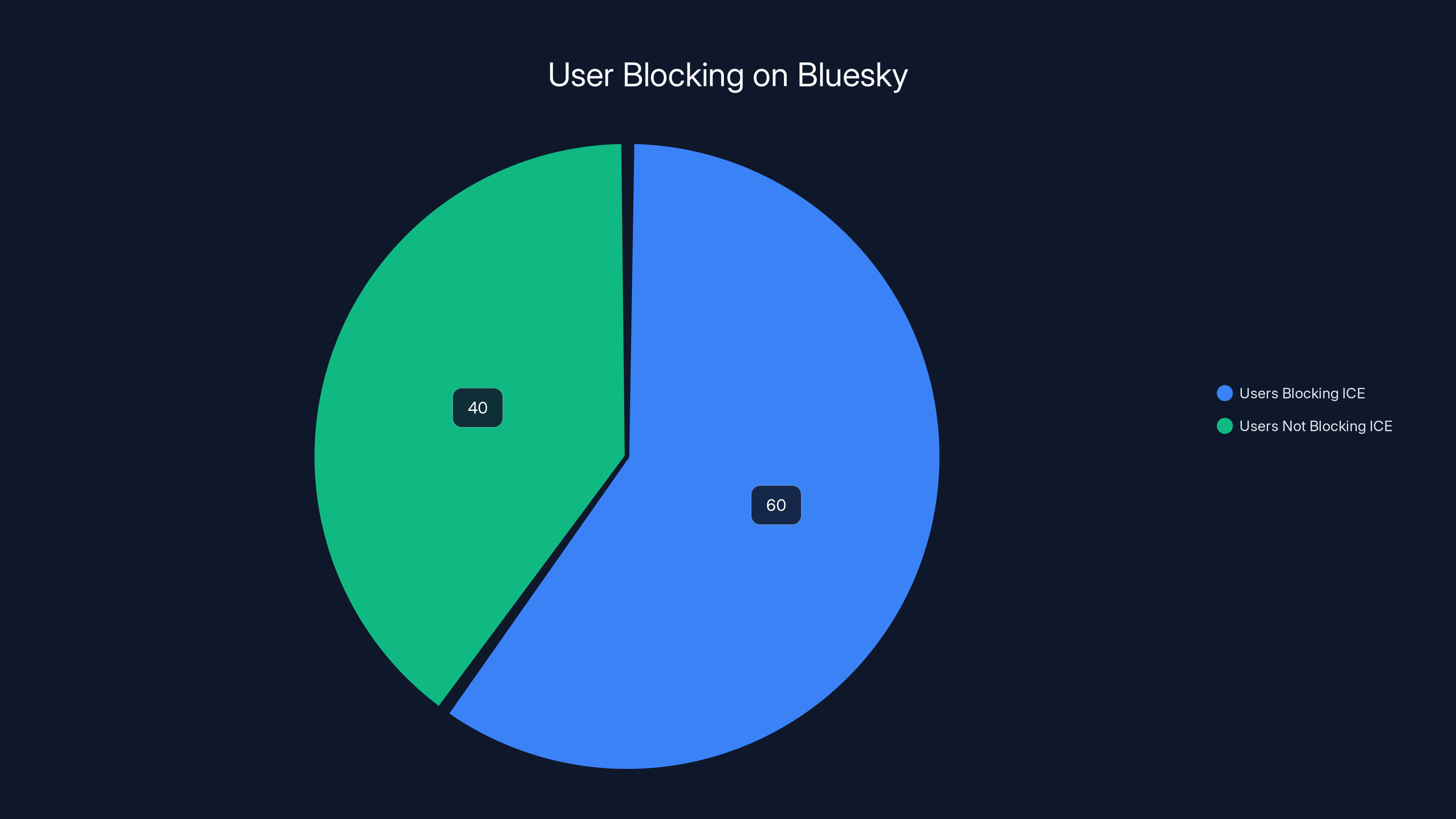

The blocking phenomenon isn't random outrage. It's a deliberate choice by users to exercise control over their feed, their information ecosystem, and their online community. On decentralized platforms, blocking functions as a form of collective curation. When over 60% of Bluesky's user base blocks a single account, it's not just personal preference—it's a statement about platform values.

What makes this story particularly interesting is the timing and the platform. Bluesky was supposed to be different from traditional social networks. Built on the AT Protocol, it promises decentralization, user control, and a break from the algorithm-driven filter bubbles of mainstream platforms. Yet here it is, hosting and verifying government accounts, facing the exact same friction that traditional platforms handle with their moderation teams and corporate policies.

This article explores what happened when ICE joined Bluesky, why the blocking response was so swift and overwhelming, what this reveals about user expectations for decentralized platforms, and how this moment might reshape conversations about government institutional presence in digital spaces. We'll look at the broader context of government accounts on social media, the role of verification in shaping user perception, and what happens when user autonomy and institutional legitimacy collide head-on.

TL; DR

- ICE joined Bluesky in November 2025 and was verified a few days before the account became one of the platform's most-blocked accounts

- Over 60% of Bluesky's active users blocked the account within days, making it rival Vice President J. D. Vance in blocking activity

- Verification became controversial because Bluesky's team appeared unprepared for hosting contentious government agencies

- The fediverse vs. traditional platforms divide was exposed, with Mastodon's founder deliberately disconnecting from Bluesky over the issue

- This reveals the core tension between institutional legitimacy and user autonomy on decentralized platforms

Estimated data shows that government agencies have the strongest presence on X (formerly Twitter) and the weakest on Mastodon. User interaction is highest on X, reflecting its role as a traditional platform for institutional accounts.

Understanding ICE's Digital Footprint and Institutional Presence

Before diving into the Bluesky controversy, it's important to understand what ICE actually is and why its presence online matters so much. ICE operates under the Department of Homeland Security and is responsible for immigration enforcement across the United States. The agency has become increasingly controversial over the past decade, particularly regarding immigration detention practices, family separations, and enforcement methods that civil rights organizations have criticized as inhumane.

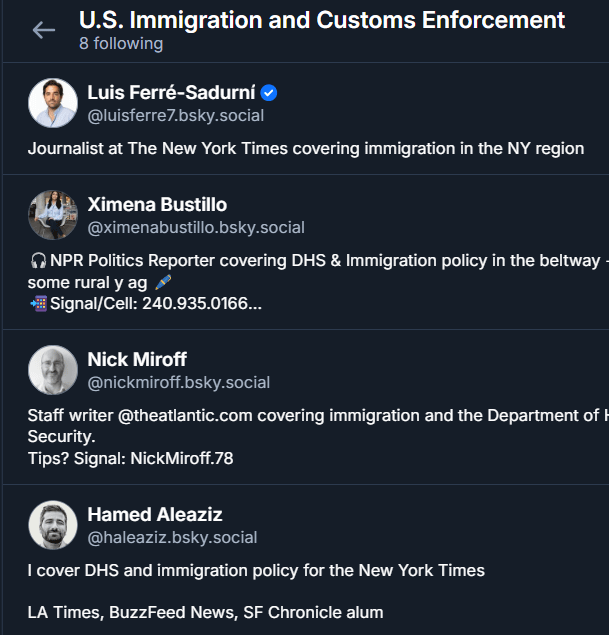

ICE's institutional presence on social media predates Bluesky by years. The agency maintains verified accounts across major platforms: X, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn. These accounts typically share information about enforcement operations, immigration policy updates, and agency announcements. On platforms like YouTube, ICE publishes its own content directly. On Instagram, the account shares photos from enforcement operations. These accounts exist in a particular context: they're official government communication channels, and they operate under the assumption that institutional legitimacy, combined with platform verification, grants them credibility and reach.

What's important to understand is that ICE's social media strategy isn't unique. Federal agencies across the U.S. government maintain similar presences. The Department of Defense, the Department of State, the Social Security Administration, and dozens of other agencies use social media to reach citizens, explain policy, and provide services. This is generally accepted as part of normal government operations in the digital age.

However, ICE occupies a particular position in the American political conversation. The agency has become a lightning rod for both immigration reform advocates and immigration restrictionists. This polarization means that ICE's institutional presence on social platforms carries significant political weight. Users don't see ICE's posts the way they might see posts from the National Weather Service or the CDC. They see them through the lens of ongoing political conflict about immigration enforcement.

This context matters enormously for understanding what happened on Bluesky. The blocking response wasn't just about a government account joining a new platform. It was about users discovering that a controversial government institution had secured institutional legitimacy on a platform they thought was supposed to be different from the corporate-controlled alternatives.

The October Government Account Wave: Setting the Stage

The story of ICE on Bluesky doesn't actually begin with ICE. It begins in October 2025, when the Trump administration signed up for Bluesky in significant numbers. This was a calculated move—the White House and multiple federal agencies opened accounts simultaneously to use the platform for political messaging.

The specific context was the government shutdown. The White House and other agencies used their new Bluesky accounts to blame Democrats for the shutdown, seizing on the platform as a way to amplify messaging to a new audience. At that time, the accounts that joined included the Departments of Homeland Security, Commerce, Transportation, Interior, Health and Human Services, State, and Defense. This was a coordinated effort, signaling that the Trump administration saw Bluesky as a legitimate channel for government communication.

What happened immediately was striking: the White House account became one of the most-blocked accounts on Bluesky. According to Clearsky, a tracking tool that uses Bluesky's API to monitor blocking activity, the White House account settled into the number 2 position on Bluesky's most-blocked accounts list. Only Vice President J. D. Vance had more blocks.

This was a significant moment that was largely overlooked at the time, but it revealed something crucial about Bluesky's user base. Despite the platform's growth and increasing mainstream adoption, its user community was fundamentally different from X's user base. On X, government accounts, even controversial ones, are typically followed and engaged with as part of the normal information ecosystem. Users might argue with them, criticize them, or disagree with their messaging, but blocking is relatively uncommon.

On Bluesky, blocking appeared to be a default response to government accounts perceived as ideologically opposed to the platform's user base. This wasn't random—Bluesky's early adopters were heavily skewed toward people who left X because of Elon Musk's leadership and the platform's perceived rightward shift. This created a user demographic that was hostile to the Trump administration's messaging from the moment those accounts arrived.

The October wave established a pattern, but it didn't fully answer the question of what would happen with agencies like ICE, which didn't join at that time and which carry particular political weight beyond standard partisan division.

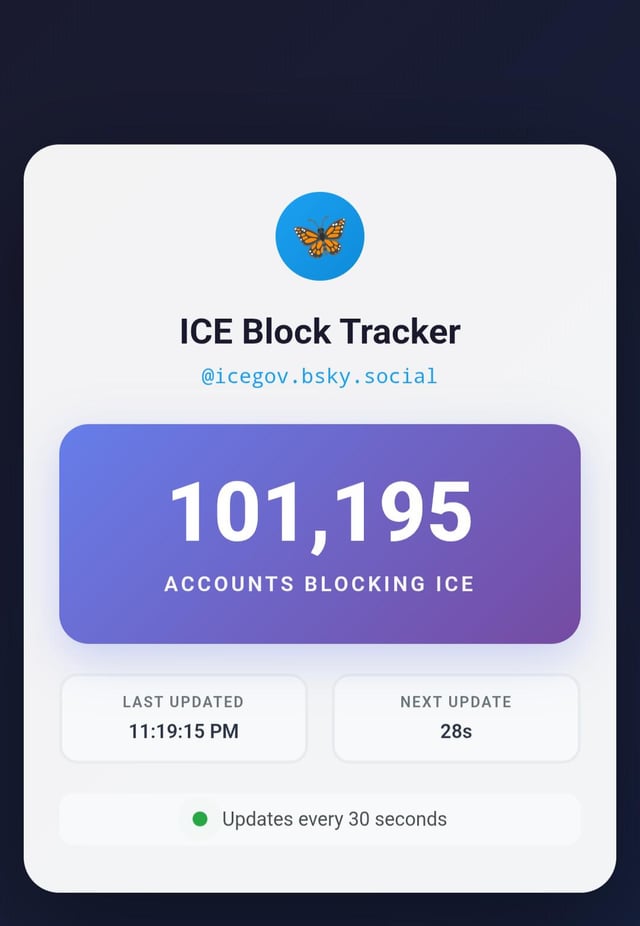

Over 60% of Bluesky's active users blocked the ICE account shortly after its verification, indicating significant user opposition. (Estimated data)

ICE's November Arrival and the Verification Question

ICE didn't join the October wave. According to Bluecrawler's Join Date Checker, the account @icegov.bsky.social joined Bluesky on November 26, 2025. This is a significant detail because it suggests the account joined weeks after the coordinated government sign-up, possibly indicating either delayed implementation of a broader strategy or a separate decision to establish Bluesky presence.

The account remained relatively quiet on the platform through December and into January. Then, a few days before the blocking phenomenon reached its peak, ICE's account was verified. This is where the story becomes interesting. According to the independently-run Verified Account Tracker, the verification happened, but the timing and reasoning remain unclear.

Bluesky, as a decentralized platform, has different verification mechanisms than traditional social networks. The platform implemented verification to help users identify authentic accounts, but the process and criteria aren't always transparent. The fact that Bluesky's team verified ICE's account suggests that either the team didn't have enough information to understand the political implications, was somehow unaware of the account's existence (which seems unlikely given ICE's previous social media presence), or was debating how to handle the issue.

This lack of transparency around the verification decision is crucial. On X, verification decisions are also sometimes controversial, but Meta, Google, and other large platforms have dedicated teams and policies for handling sensitive accounts. Bluesky appears to have been unprepared for the decision's implications. The platform hadn't publicly articulated clear policies for verifying government agencies that are politically controversial. This created a vacuum that users filled with blocking.

The verification itself likely triggered the rapid blocking response. Users discovered that ICE had an official, verified presence on Bluesky, and many interpreted this as Bluesky legitimizing the agency. Verification on social platforms carries symbolic weight—it signals authenticity, credibility, and platform endorsement. By verifying ICE, Bluesky appeared to be taking a position that this agency deserved institutional legitimacy, regardless of the political controversy surrounding it.

The Unprecedented Blocking Response

What happened next was remarkable in scale. Within days of verification, ICE's account was tracking toward the number one position on Bluesky's most-blocked accounts list. One tracker showed the account as over 60% of the way to being the most-blocked account on the platform. This statistic deserves emphasis: on a platform with hundreds of thousands of active users, over 60% of the user base chose to block a single account.

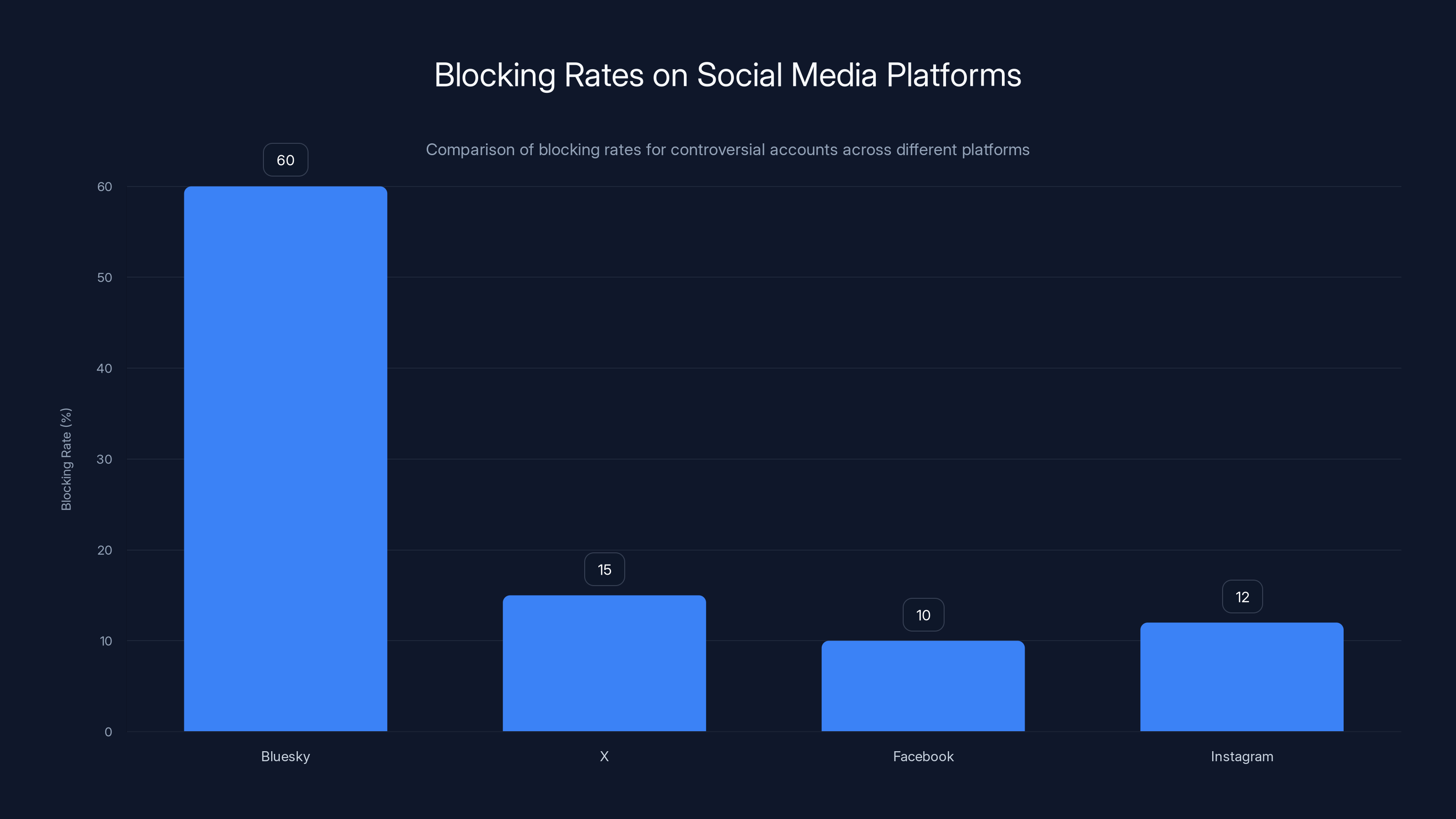

To understand how extraordinary this is, consider blocking behavior on other platforms. On X, even accounts associated with controversial figures rarely exceed blocking rates above 10-15% of the user base. Blocking behavior on traditional social networks is typically reserved for spam, harassment, explicit hate speech, or accounts that have violated terms of service. On Bluesky, the blocking of ICE represented something different: a mass, coordinated decision to remove a verified government account from the user's information ecosystem.

The blocking wasn't random or spontaneous. Posts documenting the blocking phenomenon circulated on Bluesky, creating a social dynamic where blocking ICE became a visible, community-recognized action. Users weren't just silencing an account they disagreed with—they were participating in a collective statement about what accounts belonged on the platform.

This behavior suggests something important about how decentralized platforms differ from traditional social networks. On X or Facebook, users are typically isolated in their filtering decisions. My blocking doesn't affect your feed. On Bluesky, blocking is more visible, and user behavior patterns are tracked and publicized through tools like Clearsky. This creates a feedback loop where users see blocking activity, understand it as a community norm, and choose to participate in it themselves.

The 60% blocking rate also suggests something about platform demographics and user expectations. Bluesky's user base, particularly the early adopters who make up the most active part of the community, appears to have expected the platform to maintain different content moderation and verification policies than traditional social networks. When ICE was verified, it violated those implicit expectations.

The White House Precedent: Why ICE Was Treated Differently

An important question emerges here: if the White House account became the second-most blocked account in October, why was ICE's verification more controversial? The answer reveals important distinctions about how users perceive different government agencies.

The White House is a general government account associated with whoever holds the presidency. Yes, users disagree with presidential policies, but the White House as an institution doesn't carry the same specific, focused opposition that ICE does. Users critical of Trump's policies might still view White House updates as important information about what the government is doing. ICE, by contrast, is an enforcement agency that many users view as fundamentally illegitimate.

This distinction matters because it shows that blocking behavior on Bluesky isn't just partisan. It's also issue-based and values-based. Users are making judgments about which institutions deserve platform presence, and those judgments are influenced by what those institutions actually do. The White House posts about policy; ICE posts about enforcement operations that many users see as inherently problematic.

There's also a numbers question. The White House received heavy blocking, but perhaps not as heavy as ICE did. The comparison suggests that blocking intensity might correlate with how specific and controversial an institution's function is. Broad government presence gets blocked. Enforcement agencies that people view as specifically harming their communities get blocked more intensely.

The timing also matters. By the time ICE's account was verified, Bluesky users had already experienced the White House blocking phenomenon. They had seen that the platform was willing to verify government accounts. They had established blocking as a response. So when ICE showed up, the infrastructure for rapid, coordinated blocking already existed.

Bluesky shows an unprecedented 60% blocking rate for a single account, significantly higher than typical rates on platforms like X and Facebook, which range from 10-15%. Estimated data.

Verification as a Symbol: What Does Bluesky Endorsement Mean?

At the heart of this controversy is a question about what verification actually means. On traditional social platforms, verification primarily serves authentication purposes—it tells users that the account is actually who it claims to be. But verification also carries implicit endorsement. When Facebook or Instagram verifies an account, they're making a judgment that this account is worth highlighting, important enough to distinguish from unverified accounts.

On Bluesky, verification became more politically charged. The platform positioned itself as an alternative to X, building a user base that explicitly rejected Musk's leadership and the platform's perceived rightward drift. This positioning created expectations that Bluesky would be more aligned with its user base's values. When the platform verified government accounts, particularly controversial ones, it appeared to be violating those expectations.

The question users asked, implicitly, was: if Bluesky is supposed to be different from X, why are we seeing the same institutional presence and verification? What's the point of migrating to a new platform if the power structures and institutional legitimacy remain the same?

This gets at a fundamental problem with decentralized platforms. They promise user autonomy and control, but they also need to function as public forums where information is accessible and discoverable. These goals are in tension. If Bluesky refuses to verify government accounts, it's limiting institutional access to the platform and potentially suppressing important information. If it does verify government accounts, it's granting institutional legitimacy to agencies that many users oppose.

Bluesky didn't have a clear answer to this question, and the platform's lack of transparency around the ICE verification suggested that the team hadn't thought through the implications carefully. The blocking response was, in many ways, users making the decision that Bluesky's team hadn't made: that certain institutions shouldn't have the same legitimacy on decentralized platforms as they do on corporate-controlled networks.

The Fediverse Alternative: Why Mastodon Did It Differently

The ICE verification incident exposed a deeper divide in the decentralized social media landscape. Mastodon, another decentralized platform that predates Bluesky and is built on the Activity Pub protocol, faced the same question about government accounts but reached a different conclusion.

The U.S. government doesn't have official Mastodon accounts. While individual government employees can create accounts on any Mastodon instance, there's no centralized government presence the way there is on Bluesky or X. This is partly because Mastodon is smaller and the government may not view it as worth the effort. But it's also because Mastodon's architecture gives individual server operators significant power to determine which accounts are federated with their instance.

On a Mastodon instance, a server operator can prevent federation with another server, effectively blocking all accounts from that server from interacting with their users. This means that if a controversial government account tried to set up shop on Mastodon, individual communities could refuse to federate with it. This power is baked into Mastodon's design philosophy: users and communities control which institutions and accounts they interact with.

This design choice has implications. It means government agencies face barriers to building presence on Mastodon that don't exist on Bluesky or X. But it also means that the fediverse as a whole can maintain different values and policies than centralized platforms. A Mastodon server can refuse federation with an ICE account or any other controversial institution.

The distinction between Bluesky and Mastodon became explicit during the ICE controversy. Eugen Rochko, Mastodon's founder who recently stepped down as CEO citing burnout, posted an anti-ICE message on Mastodon, stating that "Abolish ICE" doesn't go nearly far enough to address the problems in the U.S. immigration enforcement system. A day later, he announced he was opting his account out of the bridge that connects Mastodon with Bluesky.

Bridging technology, which includes projects like Bridgy Fed, allows decentralized platforms built on different protocols to interoperate. Bluesky runs on the AT Protocol, while Mastodon runs on Activity Pub, but bridging software can translate between them. This allows Mastodon users to follow Bluesky accounts and vice versa.

Rochko's decision to leave the bridge was significant. When asked if ICE's participation on Bluesky was the reason, he described it as a "personal" decision and didn't confirm or deny the connection. But the timing—announcing the bridge disconnection a day after making an anti-ICE post—suggests that the decision was influenced by concerns about Mastodon's federation with accounts and institutions hosted on Bluesky.

What Rochko's decision revealed is that there's real philosophical disagreement within the decentralized social media community about how much institutional presence these platforms should accommodate. Mastodon's philosophy emphasizes community control and the ability to refuse federation with institutions or accounts that violate community values. Bluesky's philosophy appears to be more aligned with traditional platform approaches: verify accounts, let users choose their own blocking preferences, and don't make political judgments about which institutions deserve presence.

These aren't just technical differences. They're fundamentally different visions of what decentralized social media should be. Mastodon leans toward community-controlled content ecosystems. Bluesky leans toward user-controlled content ecosystems. The ICE verification exposed how these philosophies lead to different outcomes when controversial institutions try to establish presence.

The Broader Context: Government Accounts Across Platforms

Understanding the ICE situation requires stepping back and looking at how government institutions use social media more broadly. Across X, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, and LinkedIn, government agencies maintain verified, official accounts. These accounts are part of the normal social media landscape. Citizens expect government agencies to have some form of digital presence.

ICE's accounts on these platforms typically receive engagement, criticism, and conversation. Users critique the agency's policies in the comments and replies. But users don't block government accounts at rates anywhere close to 60%. This suggests that the blocking phenomenon on Bluesky isn't just about disagreeing with government agencies—it's about a specific platform dynamic or user expectation.

One factor is that traditional social platforms have mechanisms for handling controversial accounts that decentralized platforms like Bluesky lack. X has content moderation policies and teams that make decisions about which accounts can operate on the platform. Facebook enforces community standards. YouTube demonetizes controversial content. These platforms don't remove government accounts, but they do apply various friction mechanisms to reduce visibility.

Bluesky, by contrast, built itself on the premise of minimal intervention and maximum user control. The platform's design philosophy emphasizes that users should have power to curate their own feeds rather than relying on algorithmic or moderation decisions from the platform's team. This sounds good in theory, but it created a scenario where the only tool available for users to express dissatisfaction with ICE's presence was blocking.

Another factor is user demographics. Bluesky's user base skews heavily toward people who are technologically sophisticated, interested in decentralization, and politically engaged. These users are more likely to have strong opinions about government institutions and to use tools like blocking to express those opinions. X's user base is more diffuse, including people who use the platform for work, entertainment, and casual information consumption.

The blocking phenomenon on Bluesky also reflects something about how users perceive decentralized platforms. There's a perception that Bluesky is a space for people who rejected X, that it has different values, that it's community-controlled rather than corporate-controlled. When the platform verified a controversial government agency, it violated that perception. Users responded by using the primary tool available to them—blocking—to reassert control over their platform experience.

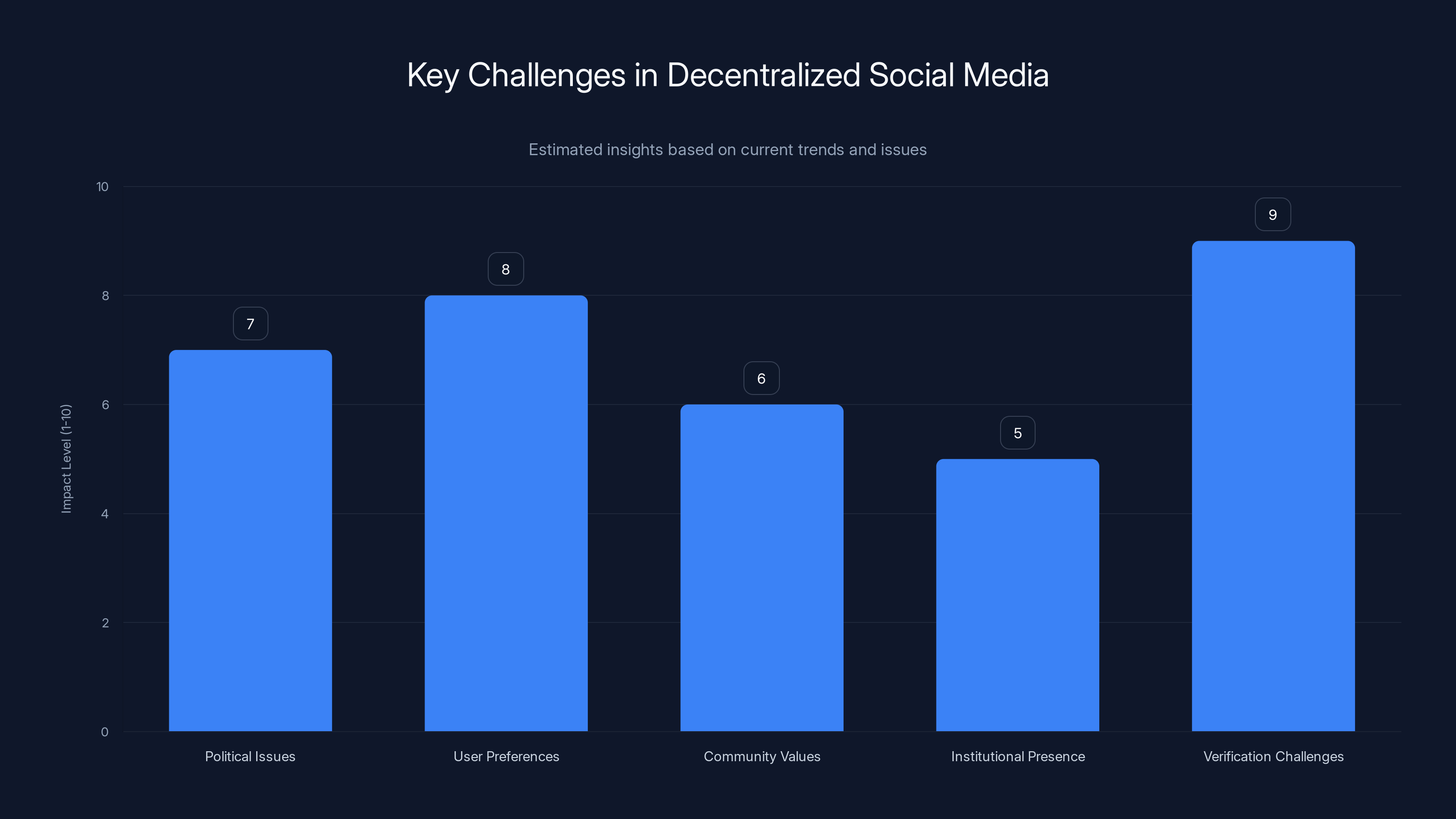

Verification challenges and user preferences are the most impactful issues for decentralized social media platforms. Estimated data based on current discussions.

The Timing: How Verification Triggered the Response

One crucial detail in this story is the precise timing of ICE's verification. The account joined Bluesky in November but wasn't verified immediately. The verification happened a few days before the blocking phenomenon reached its peak, suggesting that verification was the trigger for the rapid blocking response.

Why would verification cause such a dramatic response when the account had been present on the platform for weeks? The answer relates to how users discover accounts and how verification signals importance. An unverified government account on Bluesky is just another account. A verified account is highlighted, distinguished, marked as legitimate.

Bluesky's user interface gives verified accounts visual distinction. They appear with a checkmark, signaling authenticity. When users browse or search for accounts, verified accounts are often prioritized. This means that verifying ICE transformed the account from something most users wouldn't encounter into something that was highlighted on the platform.

More importantly, verification signals institutional legitimacy. Many Bluesky users who might not have known that ICE even had an account on the platform learned about it when the verification happened. The act of verification brought the account to users' attention and communicated that Bluesky's team had made a decision to give ICE official status.

This created a specific moment where users could respond. The accounts and posts documenting the blocking phenomenon circulated quickly on Bluesky. Users who saw these posts learned that others were blocking ICE, and they could choose to participate in that blocking. The coordination wasn't explicit—there was no official campaign to block ICE—but the social dynamics of the platform enabled rapid, distributed blocking behavior.

The timing also matters because it reveals something about how Bluesky's team operates. If the team had thought carefully about the implications of verifying ICE, they might have anticipated the blocking response or prepared some kind of announcement or context. Instead, the verification appears to have been a straightforward administrative decision that wasn't well-thought-through in terms of user expectations and community response.

Platform Design and User Autonomy: The Core Tension

At the root of this story is a design challenge that affects all social platforms but is particularly acute for decentralized ones. How do you balance institutional legitimacy with user autonomy? How do you create spaces where important information is accessible while respecting users' right to curate their own experiences?

Traditional platforms like X, Facebook, and Instagram solve this problem through a combination of moderation, algorithmic promotion, and design choices. They have policies that determine which accounts can be verified. They have algorithms that decide what appears in feeds. They have design choices that make blocking less visible and prominent.

Bluesky tried to solve it differently. The platform is built on the premise that users should have maximum control over their feeds. The algorithm is theoretically open—users can choose which algorithm governs their feed. Verification is supposed to be straightforward and transparent. Blocking is a user tool, not a moderation tool.

But this design creates a scenario where when users disagree with a platform decision (like verifying ICE), they can only express that disagreement through user tools (like blocking). They can't appeal to a moderation team because there is no moderation team making content decisions. They can't expect algorithmic demotion because the algorithm is transparent and user-controlled.

The ICE blocking phenomenon is, in a sense, users finding a workaround to the lack of moderation. If the platform won't remove or demote ICE, users will block it. Sixty percent blocking might not remove the account, but it effectively removes it from most users' feeds.

This raises a question about platform design philosophy. Is it better to have centralized moderation decisions that some users disagree with, or to let users make distributed decisions through blocking that effectively segregate controversial accounts? The answer probably depends on what you value: institutional legitimacy, community control, or user experience.

Institutional Legitimacy vs. Community Values

The ICE blocking phenomenon also reflects a broader question about what institutions deserve presence on digital platforms. There's an implicit assumption in our current media environment that government agencies, especially federal agencies, have a right to digital presence. They use social media to communicate policy, provide services, and reach citizens.

But Bluesky's user base seems to have rejected that assumption, at least for ICE. Users made a collective decision that this particular institution shouldn't have the same legitimacy on Bluesky that it does on other platforms. This wasn't organized from above—there was no platform policy preventing ICE from having an account. It was a bottom-up decision by users to exclude the agency from their information ecosystem.

This raises the question: should platforms respect these user decisions, or should they maintain institutional access regardless? There's no obvious answer. One perspective is that government agencies need digital presence to communicate with citizens, and platforms shouldn't allow user preferences to prevent that communication. Another perspective is that if the majority of a platform's users don't want to hear from an institution, the platform should respect that preference.

Decentralized platforms like Bluesky are particularly interesting in this context because they're supposed to give users power. But when users collectively exercise that power against institutional presence, it reveals that decentralization doesn't automatically align platform values with user preferences. Bluesky's team still made the decision to verify ICE, and users still had to work around that decision through blocking.

The ideal outcome might be one where platforms are more transparent about their policies and reasoning. If Bluesky's team had publicly articulated why they were verifying ICE, and what criteria they use for verifying controversial government accounts, users would have a clearer understanding of platform values. Instead, the verification appeared arbitrary, which likely amplified the blocking response.

Estimated data shows that traditional platforms like X and Facebook receive the majority of government engagement, while newer platforms like Bluesky see less interaction. Estimated data.

The Role of Bridging: Connecting Decentralized Platforms

One technical detail that became important in this controversy is bridging technology, which allows decentralized platforms built on different protocols to interoperate. Specifically, Bridgy Fed is a project that bridges Mastodon (built on Activity Pub) with Bluesky (built on AT Protocol).

Bridging technology is meant to solve the fragmentation problem in decentralized social media. Without bridges, different decentralized platforms would operate in isolation, each building their own user base and content ecosystem. With bridges, users on one platform can follow and interact with users on another, creating a more unified decentralized social web.

But bridging also creates federation challenges, particularly around content moderation and community standards. When Mastodon and Bluesky are bridged, Mastodon instances are essentially federated with Bluesky accounts. This means that content and accounts from Bluesky are accessible on Mastodon, and Mastodon communities have to make decisions about whether to accept that content.

Conventionally, bridging technology for decentralized platforms works through a concept called defederation. Mastodon instances can choose not to federate with other instances that don't meet their community standards. But bridging between different protocols is more complex. Bridgy Fed creates a bridge, and individual Mastodon instance operators can theoretically configure their own interactions, but it's not as straightforward as refusing to federate with another Mastodon instance.

Eugen Rochko's decision to opt out of the bridge is significant in this context. By disconnecting his account from the bridge, Rochko prevented his account (and by extension, the Mastodon project) from being connected with Bluesky through Bridgy Fed. This is a way of saying that Mastodon and the broader fediverse don't want to participate in the same ecosystem as Bluesky if that means accepting bridging with accounts like ICE.

The technical timing also matters. Bridgy Fed launched the ability to add domain blocklists to bridged accounts on the same day that ICE's blocking phenomenon was reaching its peak. This would theoretically allow fediverse users to block government agencies on Bluesky without those blocks affecting Mastodon. But Rochko's decision was broader—rather than using technical tools to manage bridging, he simply disconnected.

This reveals the limitations of bridging technology. Building a truly decentralized social web requires that different platforms share some basic values or at least have mechanisms to resolve value conflicts. When Mastodon and Bluesky have fundamentally different approaches to institutional presence and community control, bridging becomes contentious. Rochko's decision essentially rejects the possibility of bridging between the two platforms.

What This Means for the Future of Decentralized Social Media

The ICE verification controversy reveals several important truths about decentralized social media that will shape its future development. First, decentralization doesn't automatically solve the political problems that plague traditional social platforms. The same tensions between institutional presence, user preferences, and community values show up on decentralized platforms—they're just expressed differently.

Second, users will find ways to express their preferences even within constrained design choices. If blocking is the only tool available, users will use blocking intensively. This isn't necessarily a failure of platform design, but it does suggest that platforms need to think carefully about what tools users have and what behavior those tools enable.

Third, decentralized platforms attract users with specific values and expectations. Bluesky's user base arrived with expectations about what the platform would be, and those expectations shaped how they responded to institutional presence. Platforms that want to remain decentralized need to actively maintain alignment with their communities, or users will migrate or organize within the platform in ways that undermine the platform's goals.

Fourth, the broader decentralized social media ecosystem (including Mastodon, Pixelfed, Peer Tube, and others) is still figuring out how to handle institutional presence and federation. Rochko's decision to disconnect from the bridge is one approach, but it's not clear if it's the right long-term solution. There's probably a need for clearer, more explicit policies about how decentralized platforms handle controversial institutions.

Fifth, verification is a more fraught decision on decentralized platforms than on traditional ones. On X or Facebook, verification is relatively uncontroversial because those platforms already make many other decisions about content, reach, and visibility. On decentralized platforms that emphasize user control, verification carries more weight and sends a clearer signal about platform values.

Moving forward, Bluesky and other decentralized platforms will probably need to be more explicit about their verification policies. They might consider separating authentication (proving you are who you claim to be) from verification (signaling that your account is important or worthy of attention). They might also need to consider whether certain categories of accounts should be subject to additional scrutiny before verification.

But there's also a possibility that Bluesky will simply accept that its user base is willing to use blocking as a way to maintain control over the platform's ecosystem. If 60% blocking doesn't violate the platform's terms of service and doesn't prevent ICE from operating, maybe that's just how decentralized platforms work. Users get the final say, not through moderation decisions but through their own choices about which accounts to block.

The Broader Landscape: Other Government Accounts and Platforms

To fully understand the ICE situation, it's worth looking at how government accounts are functioning across the broader social media landscape in early 2025. The Trump administration's use of Bluesky to announce the government shutdown blame was part of a broader strategy of using social media for political messaging.

On X, government accounts are standard. The White House, various cabinet departments, and numerous federal agencies maintain accounts that serve as primary channels for official communication. These accounts have millions of followers, and their posts generate thousands of retweets and replies. Some users criticize the accounts, but blocking is relatively rare.

On Instagram, government accounts are less politically charged. The DHS and other agencies share photos and updates, but the format is less conducive to political argument. Users might scroll past, but they're less likely to engage in blocking behavior.

On Facebook, government accounts operate in a similar space to X, but the platform's algorithmic design and user demographics mean that government content reaches different people. Facebook's older user base is probably more accepting of government institutional presence than Bluesky's younger, more tech-savvy user base.

YouTube is interesting because it's less of a social platform and more of a content platform. Government agencies post official videos, and users can comment, but the dynamic is different from Twitter-like platforms. ICE has a YouTube channel with various videos about the agency, but this doesn't generate the same kind of blocking behavior.

LinkedIn is professional-oriented, so government accounts function as employer accounts, recruiting and sharing workplace information. This is relatively uncontroversial.

The key insight is that Bluesky's blocking phenomenon is unusual. It suggests that either Bluesky's user base is particularly hostile to government institutions, or that the platform's design and values create different incentives around institutional presence.

Probably it's some combination of both. Bluesky's user base self-selected for people interested in decentralization and alternative platforms, which tends to correlate with skepticism of institutional authority. At the same time, Bluesky's design emphasizes user control more explicitly than other platforms, which makes users more comfortable using tools like blocking to exercise that control.

An estimated 60% of Bluesky users block ICE's account, highlighting a significant user-platform disconnect. Estimated data.

Verification and Public Discourse: What Gets Legitimacy?

The ICE verification raises a fundamental question about verification on social platforms and what it signals about institutional legitimacy. When platforms verify accounts, they're making a statement that these accounts are important, authentic, and worthy of distinction. This statement carries weight.

On X, verification has been particularly fraught since Elon Musk's takeover. X introduced paid verification, separating authentication from verification. This meant that people could pay to get a checkmark, which changed what verification signaled. On other platforms, verification is handled by the platform's team and typically requires some kind of prominence or authority.

Bluesky's verification process isn't entirely clear from the available information, but the fact that ICE was verified without obvious public debate suggests that the process is either automated or handled without much deliberation. This is different from X's approach under previous management, where verification decisions were made by a team with some oversight.

The implications are worth thinking through. If Bluesky is going to verify government accounts, it should probably be clear about why. Is it just authentication? Is it signaling that the government account is important? Is it a neutral stance on institutional presence? Without clarity, users have to infer what verification means, and they seem to have inferred that it means Bluesky is endorsing or at least legitimizing ICE.

One possible path forward is for platforms to separate authentication from prominence. An account could be verified as authentic (you are really ICE) without being highlighted, promoted, or distinguished from other accounts. This would preserve authentication while reducing the legitimacy signal.

Another path is for platforms to be explicit about which institutions get verified and why. If Bluesky is going to verify government accounts, maybe it should verify all of them with the same process. Or maybe it should develop specific policies about how verification works for institutions that are politically controversial.

The third path is to accept that user preferences, expressed through blocking and other mechanisms, are sufficient to determine which institutions get prominence on decentralized platforms. This means that ICE might remain on Bluesky, but with most users blocking it, effectively marginalizing the account.

The Information Ecosystem Implications

When 60% of a platform's users block an account, what happens to information access? Users who block ICE won't see its posts, but they also won't be exposed to information that ICE shares. This could be important information about enforcement operations, policy changes, or procedural updates. Blocking ICE means not just avoiding the account's political messaging, but also potentially missing information that might be relevant.

This is the tension between user autonomy and information access. Users want to control their feeds, but they also need access to important information. On traditional platforms, moderation and algorithmic design try to balance these concerns. On Bluesky, the platform is letting users make the balance themselves through blocking.

There's an argument that this is fine. If users don't want to follow ICE, they shouldn't have to. If they want to get information about ICE's policies, they can access it through other channels—news media, policy briefs, advocacy organizations. Blocking ICE on Bluesky doesn't prevent users from accessing information about the agency.

But there's also an argument that platforms have a responsibility to maintain channels for institutional communication, even when users don't want to hear from those institutions. Government agencies need ways to reach citizens, and if platforms let users block those agencies completely, it undermines the institution's ability to communicate.

This probably isn't an easily solvable problem. Different users and platforms will make different choices about how to balance user autonomy with institutional access. What matters is being transparent about those choices and understanding the implications.

For Bluesky specifically, the blocking phenomenon suggests that the platform's user base has different expectations about information access than traditional platform users. Bluesky's users seem more willing to exclude institutional voices from their feeds, and they're willing to do it at scale. This will probably shape how Bluesky develops as a platform.

Comparison: Institutional Presence on Different Platforms

To better understand what's unique about the Bluesky situation, it's useful to compare how ICE and other government agencies function on different platforms.

On X (formerly Twitter), the Department of Homeland Security maintains an account with thousands of followers. The account posts about immigration policy, enforcement operations, and agency initiatives. Users respond with criticism, support, and discussion. But there's no massive blocking phenomenon. Users don't organize to block the account at rates anywhere close to 60%.

Why? Probably because X's user base is more accustomed to institutional presence. X has always hosted government accounts, and users expect them there. There's no surprise or betrayal when the DHS has a verified account.

On Instagram, ICE's presence is less political. The agency's Instagram account (@ice.gov) shares photos and updates, but the format is less conducive to political debate. Users might criticize posts in comments, but blocking is less common.

On Facebook, the dynamics are somewhere between X and Bluesky. Government agencies have a presence, but the platform's algorithm and design mean that content doesn't surface as prominently. Users who don't want to see DHS content can easily avoid it without explicitly blocking.

On Mastodon, there is no government presence. The decentralized platform's design and culture make it difficult for government institutions to establish presence. Server operators can refuse federation with accounts they don't want on their instance. This gives communities more power to exclude institutions.

Bluesky is caught between these approaches. It's designed with user autonomy in mind (like Mastodon), but it's more centralized than the broader fediverse. It allows verified accounts (like X), but its users have stronger expectations about community control. The result is a platform where users will find ways to exercise control when they disagree with institutional presence.

The comparison suggests that Bluesky is probably fine with the blocking phenomenon. The platform is working as designed—users are using available tools to curate their experience. The blocking doesn't violate any policies or remove the account. It just constrains its reach. And that might be exactly what a user-controlled, decentralized platform should do.

What's Next: Policy Evolution and Platform Choices

Looking forward, several questions remain unanswered about how Bluesky will handle institutional presence and verification. Will the platform develop explicit policies about verifying government agencies? Will it separate authentication from verification to reduce legitimacy signals? Will it accept that user blocking is a normal, acceptable mechanism for constraining institutional reach?

These aren't easy questions, but they're important ones. Bluesky's decisions will probably influence how other decentralized platforms handle similar situations. If Bluesky accepts blocking as a mechanism for controlling institutional presence, other platforms might follow suit. If Bluesky develops policies to limit which institutions get verified, other platforms might do the same.

There's also a possibility that Bluesky will decide the status quo is fine. ICE's account exists, it's verified, and 60% of users block it. This isn't a crisis from the platform's perspective. It's just how the platform works. Users have expressed a preference, and they've acted on it. Nothing needs to change.

But it might be worth thinking about the message that massive blocking sends. When 60% of a platform's users decide to completely exclude an account from their feed, it's significant. It suggests that there's a real disconnect between platform decisions and user preferences. That disconnect might be solvable through better communication or policy development.

For government institutions like ICE, the blocking phenomenon raises questions about whether decentralized platforms are effective channels for institutional communication. If the majority of a platform's users don't want to hear from you, is it worth maintaining a presence? This is a judgment call that institutions will have to make for themselves.

It's also possible that this incident will accelerate efforts to develop federation tools and policies that let communities maintain boundaries around institutional presence. If Mastodon's move to disconnect from Bridgy Fed is the first example, we might see more efforts to create alternative decentralized social networks that are explicitly anti-institutional or explicitly different in their values than Bluesky.

The Longer Arc: What This Says About Digital Platforms

Zooming out from the specific incident, the ICE verification and blocking phenomenon tells a larger story about where digital platforms are heading and what role they play in civic life. A few key insights emerge:

First, the proliferation of platforms means that institutions can't rely on any single channel for communication. Government agencies need presence on multiple platforms because users are distributed across them. But users on different platforms have different expectations and values. What works on X might not work on Bluesky.

Second, as platforms multiply and diversify, there's less consensus about what institutional presence should look like. Traditional social networks accepted institutional accounts as normal. Decentralized platforms are still figuring out whether they want that same arrangement. This creates a landscape where institutions have to navigate different rules and norms on different platforms.

Third, user preferences and expectations are becoming more important drivers of platform features than centralized design decisions. On Bluesky, users didn't need moderation teams to constrain institutional reach—they just blocked ICE themselves. This suggests that future platforms might give even more power to users to shape their own information ecosystems.

Fourth, the distinction between different types of institutional presence matters. Users blocked ICE at rates they didn't block the White House. Users are making nuanced judgments about which institutions belong on their platform and which don't. This suggests that blanket policies about institutional presence might be less effective than policies that account for what institutions actually do.

Fifth, transparency about platform values and decision-making is increasingly important. The ICE verification was controversial partly because it wasn't clear why Bluesky made the decision or what criteria were used. If platforms are transparent about how they make these decisions, users can better understand and accept them.

Sixth, there's a real opportunity for platforms to differentiate themselves through their approach to institutional presence and content moderation. Bluesky is already differentiating from X by being more decentralized and user-controlled. Mastodon is differentiating by being anti-institutional. These differences might be features, not bugs.

Conclusion: Control, Legitimacy, and the Future of Digital Space

The ICE verification and blocking phenomenon on Bluesky is significant not because it's the most important thing happening on social media, but because it crystallizes a larger conversation about institutional legitimacy, user autonomy, and platform values in the digital age.

At the most basic level, what happened is straightforward: a government agency was verified on a decentralized platform, and users responded by blocking the account at unprecedented rates. This is a factual, observable phenomenon that tells us something about how Bluesky's user base views institutional presence.

But the deeper significance lies in what this reveals about how users want to engage with institutions online. The blocking phenomenon wasn't just about disagreeing with ICE's policies or opposing its approach to immigration enforcement. It was about asserting control over a digital space that was supposed to be different from X, that was supposed to prioritize user autonomy and community values.

When Bluesky verified ICE, users experienced it as a violation of the platform's promise. They responded by using the tools available to them—in this case, blocking—to reassert control. This created a situation where institutional presence persists, but the institution's reach is dramatically constrained.

For Bluesky as a platform, this incident creates an opportunity to clarify what the platform stands for and what kinds of institutional presence it supports. For the broader decentralized social media ecosystem, it raises questions about how different platforms will handle similar situations. For government institutions, it suggests that decentralized platforms might not be reliable channels for reaching citizens.

But perhaps the most important takeaway is that digital platforms are increasingly shaped by user preferences and collective action, rather than top-down decisions from platform leadership. The blocking of ICE wasn't mandated by Bluesky's team. It was a bottom-up phenomenon where users made independent decisions that, collectively, reshaped the platform's landscape.

This represents a shift toward user-driven platform governance. Whether that's a good thing probably depends on what you think about user preferences and democratic decision-making. But it's clearly the direction that some platforms are heading, and it's worth taking seriously as we think about what role digital platforms will play in civic life and institutional communication going forward.

The ICE account will continue to exist on Bluesky, verified and official. But for most users, it effectively doesn't exist, blocked out of their feeds and their information ecosystem. That's probably not what Bluesky's leadership intended when they verified the account. But it might be exactly what the platform's user-driven design enables and even encourages.

FAQ

What is ICE and why is its Bluesky presence controversial?

ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) is a federal agency under the Department of Homeland Security responsible for immigration enforcement in the United States. Its presence on Bluesky became controversial because the agency has become a focal point in debates about immigration policy and enforcement practices, and many users viewed its verification on Bluesky as institutional legitimation of a politically contentious agency.

How many Bluesky users blocked the ICE account?

According to tracking data, the ICE account was blocked by over 60% of Bluesky's active users within days of verification, making it one of the most-blocked accounts on the platform, second only to Vice President J. D. Vance.

Why did Eugen Rochko disconnect Mastodon from Bluesky?

Rochko, Mastodon's founder, opted his account out of Bridgy Fed, the bridge that connects Mastodon with Bluesky. While he described the decision as personal, it came after he posted an anti-ICE message on Mastodon. The timing suggests concerns about Mastodon's federation with accounts and institutions on Bluesky, particularly controversial government agencies like ICE.

What is the difference between Mastodon and Bluesky's approach to institutional presence?

Mastodon, built on the Activity Pub protocol, gives individual server operators power to refuse federation with instances that don't meet their community standards, effectively blocking institutions from their networks. Bluesky, built on AT Protocol, relies more on user-level blocking and individual preference, allowing institutions to maintain presence even if they're blocked by many users.

Does verification on Bluesky mean endorsement?

Bluesky hasn't clearly articulated what verification means or what criteria are used. While verification technically just confirms account authenticity, it also carries an implicit signal of legitimacy and importance. Many Bluesky users interpreted ICE's verification as platform endorsement, which likely amplified the blocking response.

How does institutional presence on Bluesky compare to X or other platforms?

Government agencies maintain verified accounts on X, Facebook, and Instagram without generating blocking rates anywhere close to what happened with ICE on Bluesky. This suggests that either Bluesky's user base is more hostile to institutional presence, or the platform's design and values create different incentives around blocking and account interaction.

What happens to information access when users block government accounts?

When users block ICE's account, they won't see its posts or updates. This means missing any information the agency shares directly on Bluesky. However, users can still access information about ICE through news media, policy briefs, and advocacy organizations, so blocking doesn't completely eliminate information access.

Will Bluesky develop policies to prevent similar controversies?

Bluesky hasn't publicly announced plans to change its verification policies in response to the ICE blocking phenomenon. The platform might develop clearer verification criteria, separate authentication from prominence signals, or explicitly define how verification works for controversial institutions, but as of now, there's no indication the platform views the blocking as a problem requiring policy change.

What is Bridgy Fed and why does it matter?

Bridgy Fed is a bridging technology that allows Mastodon (built on Activity Pub) to interoperate with Bluesky (built on AT Protocol). This creates federation between different decentralized platforms. Rochko's decision to disconnect Mastodon from the bridge reflected concerns that federation with Bluesky's institutional accounts would contradict Mastodon's community values.

Could the same blocking phenomenon happen on other platforms?

Probably not at the same scale. X's user base is more accustomed to institutional presence. Traditional platforms have built-in mechanisms (algorithms, design choices, moderation) that constrain visibility without requiring users to actively block accounts. Bluesky's emphasis on user control and transparency makes blocking a more visible, coordinated response mechanism.

What does the blocking phenomenon reveal about platform design and user preferences?

The blocking shows that users will find ways to exercise control over their information ecosystem, even within constrained design choices. When blocking is the primary available tool, users will use it intensively. This suggests that platforms emphasizing user autonomy need to think carefully about what tools users have and what behaviors those tools enable.

Key Takeaways

- ICE's verification on Bluesky triggered rapid mass-blocking, with over 60% of users blocking the account within days—unprecedented institutional blocking behavior

- Bluesky's user-controlled design philosophy enables distributed blocking as a form of collective curation that traditional platforms don't experience

- The blocking phenomenon reveals fundamental differences between decentralized platforms and traditional social networks in how they handle institutional presence

- Mastodon's founder disconnected from Bluesky bridging technology in response to institutional accounts, showing real philosophical divides in the fediverse

- Government agencies now face different user expectations and blocking responses depending on which platform they choose for institutional communication

Related Articles

- Bluesky's New Features Drive 49% Install Surge Amid X Crisis [2025]

- Jimmy Wales on Wikipedia Neutrality: The Last Tech Baron's Fight for Facts [2025]

- Meta's Oversight Board and Permanent Bans: What It Means [2025]

- How Grok's Deepfake Crisis Exposed AI Safety's Critical Failure [2025]

- xAI's Grok Deepfake Crisis: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Crisis: The Ashley St. Clair Lawsuit and AI Accountability [2025]

![ICE Verification on Bluesky Sparks Mass Blocking Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ice-verification-on-bluesky-sparks-mass-blocking-crisis-2025/image-1-1768934249777.jpg)