The Great Sensor Shakedown: Why Ouster Is Buying Stereo Labs Right Now

There's something happening in the robotics and autonomous systems world that nobody's talking about loudly enough. The sensor makers are eating each other.

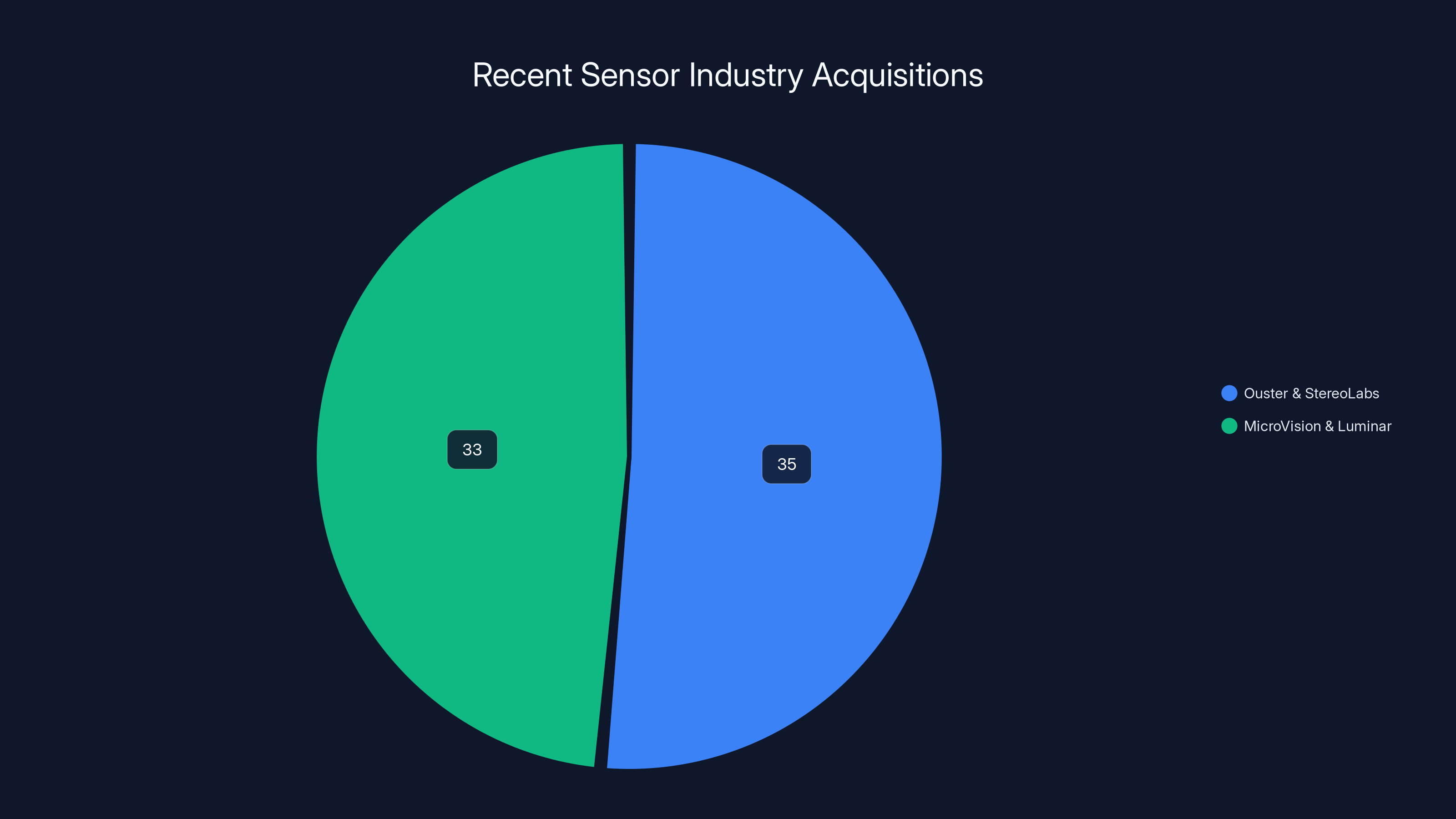

In early 2026, Ouster—the lidar company that went public and then merged with Velodyne—announced it was dropping $35 million plus 1.8 million shares to acquire Stereo Labs, a 15-year-old company that makes stereo vision systems. On the surface, it looks like a normal tech M&A play. Dig deeper, and you're looking at something more fundamental: the entire perception sensor industry is reorganizing itself around a single bet on "physical AI."

Just a month before Ouster's move, Micro Vision picked up Luminar's lidar assets for $33 million. Before that, there were smaller acquisitions, smaller consolidation plays. But here's what makes this different. These aren't struggling startups getting rescued by bigger fish. These are established sensor companies—companies with real revenue, real customers—merging because the market has fundamentally changed.

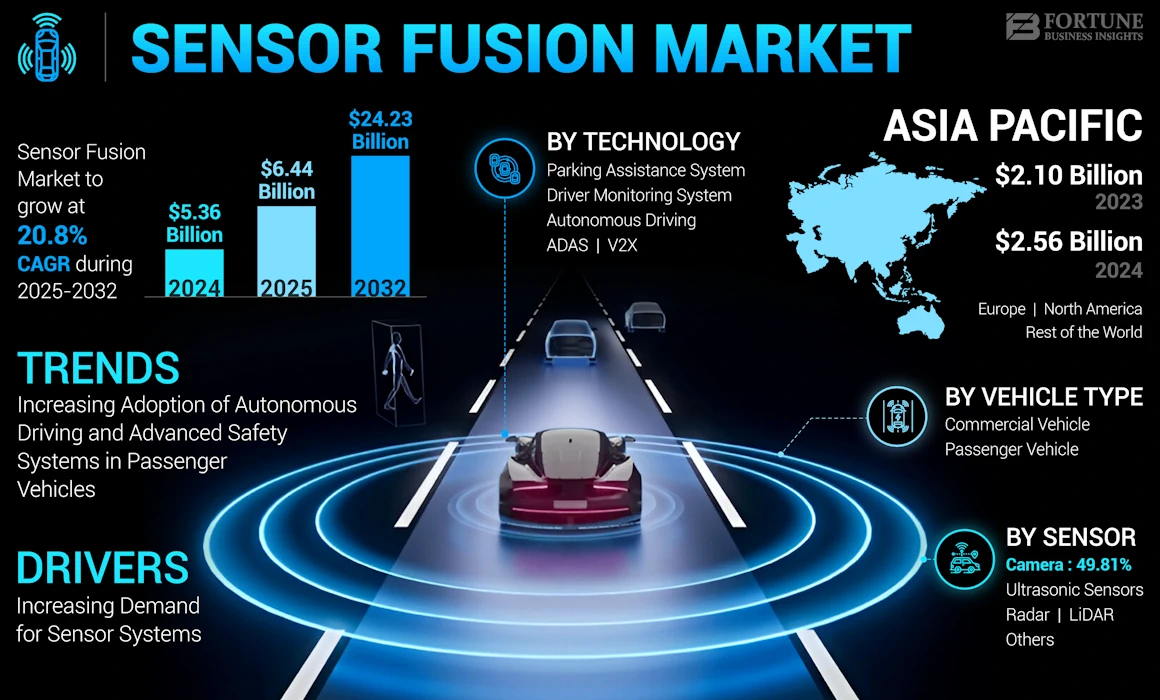

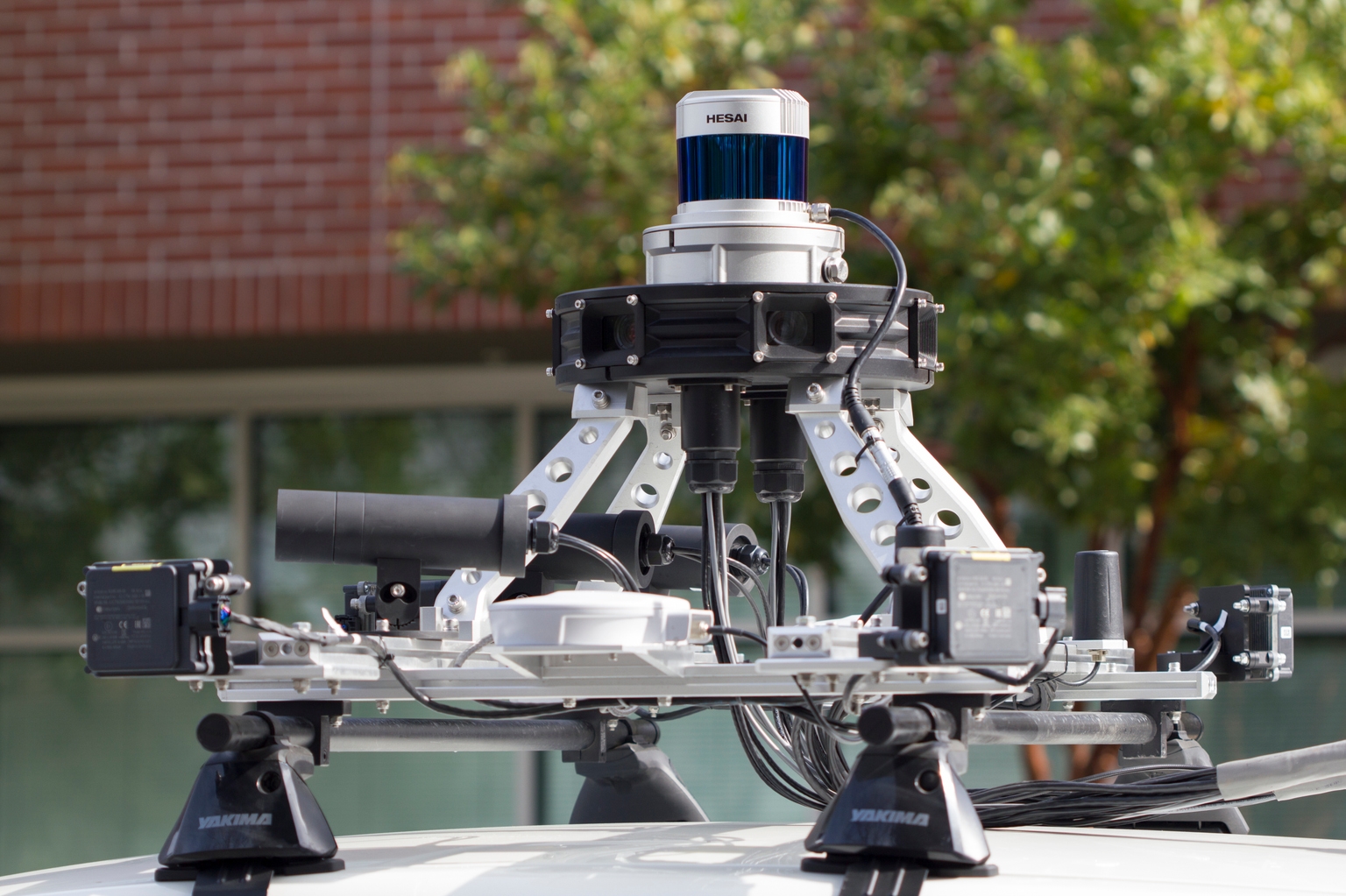

The bet these companies are making is huge. They're betting that the future of robotics, autonomous vehicles, drones, and warehouse automation depends on integrated perception systems. Not just lidar. Not just cameras. Not just thermal. All of it together, processed intelligently, with edge AI doing the heavy lifting.

This article breaks down what's actually happening in the sensor consolidation wave, why it matters, and what it means for companies building physical AI systems. Because if you're working in robotics or autonomous systems, you need to understand this shift. The sensor layer is becoming a competitive advantage. And the companies that own the most of the stack are going to win.

TL; DR

- Sensor consolidation is accelerating: Ouster bought Stereo Labs for 33M in the same timeframe

- Physical AI is the driver: Companies need integrated perception systems combining lidar, cameras, thermal, and edge AI to build working autonomous systems

- The stack matters more than components: Success requires unified hardware and software, not best-of-breed point solutions

- Market pressure is real: Revenue isn't enough to support all current competitors; consolidation or exit is the likely path for most sensor startups

- Safety and certification are the moat: Building trustworthy, certified systems takes years; hype cycles won't deliver working products quickly

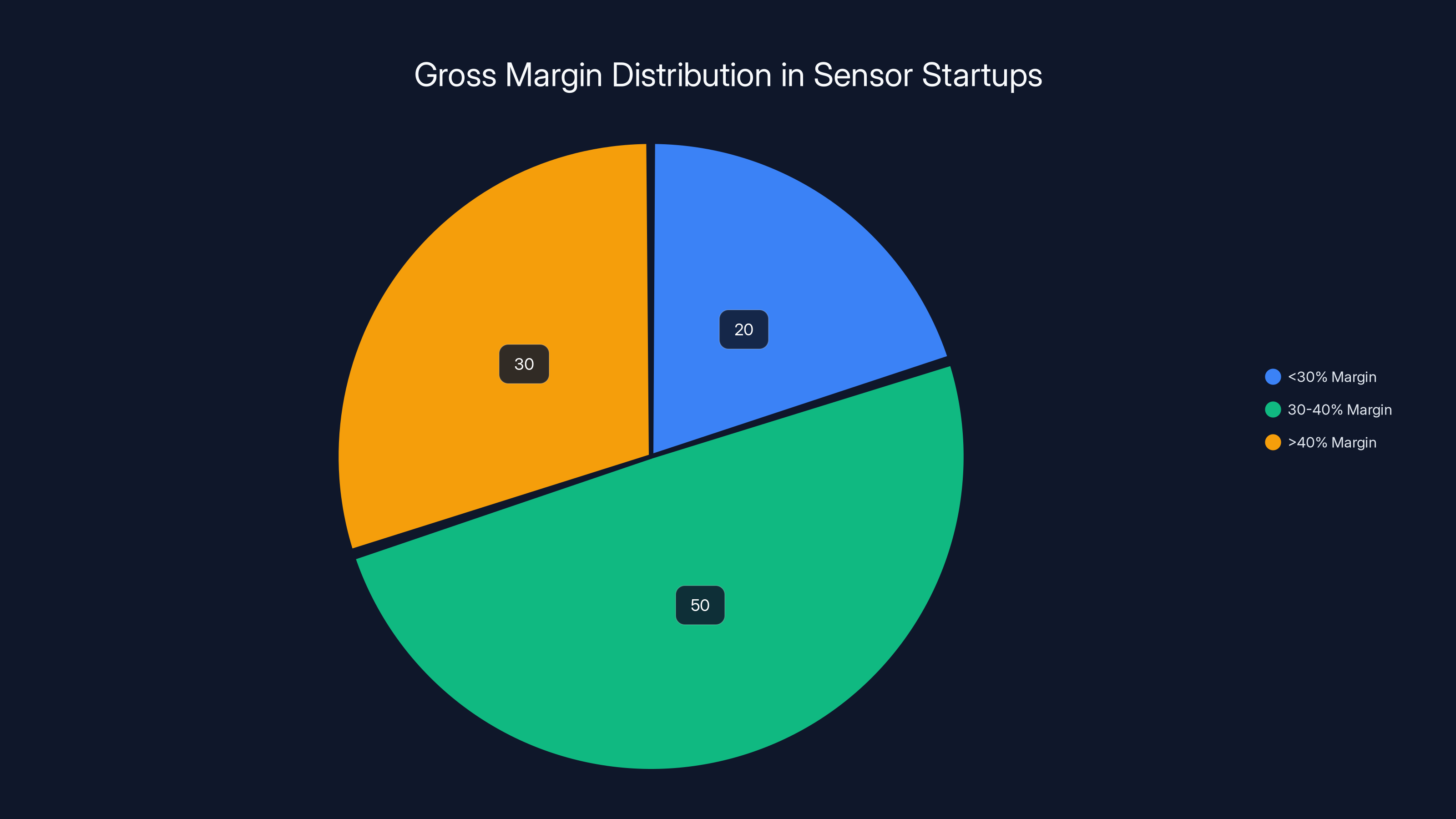

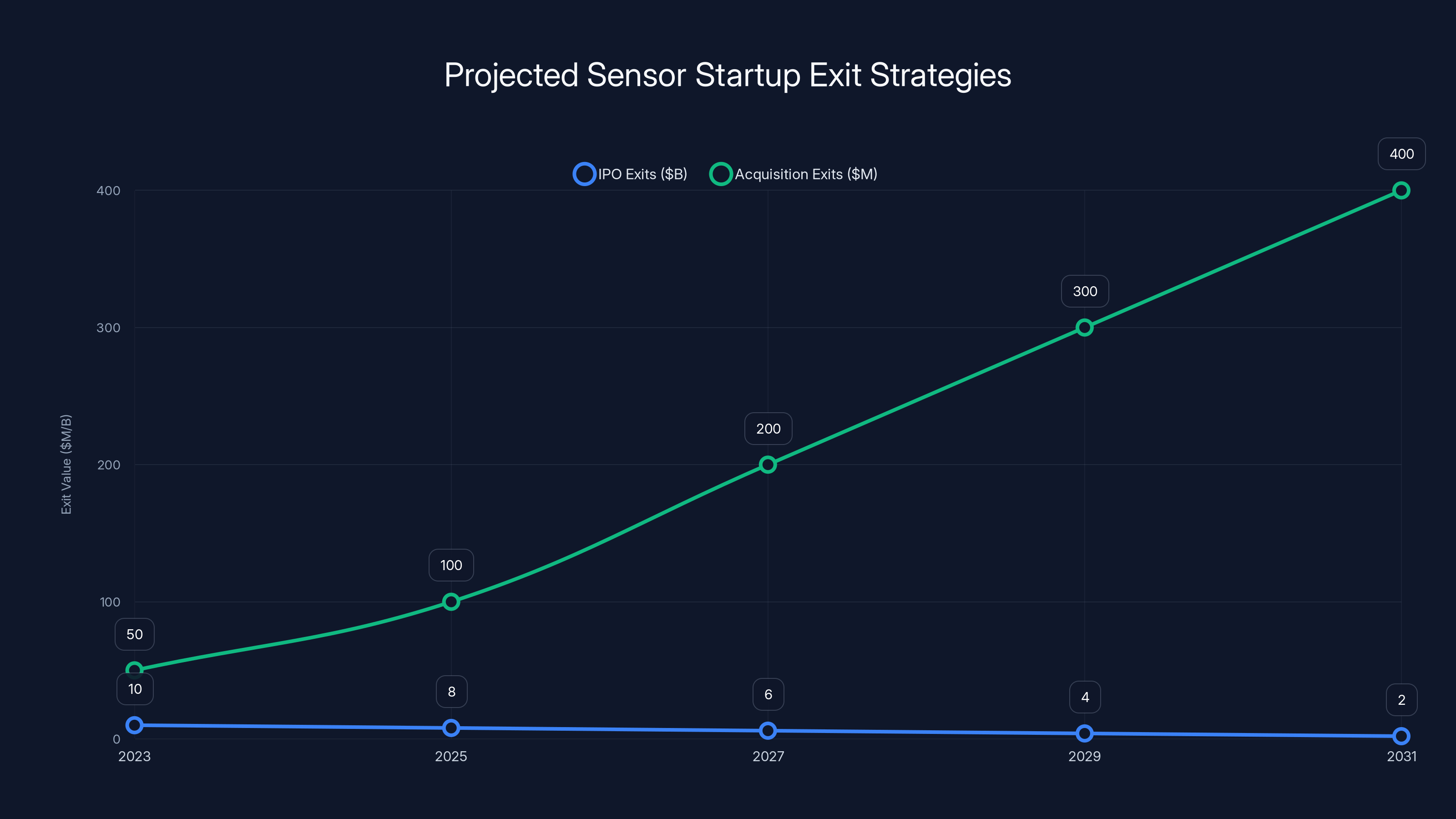

Estimated data shows that around 50% of sensor startups operate within a 30-40% gross margin range, highlighting the financial pressure to achieve profitability.

Understanding the Sensor Consolidation Wave

Consolidation in hardware is different from consolidation in software. When software companies merge, it's often about talent, technology, and market position. Hardware consolidation is messier. You're dealing with supply chains, manufacturing capacity, customer relationships, and the unglamorous reality of actually building things at scale.

Ouster's acquisition of Stereo Labs isn't a talent grab or an acqui-hire play. Stereo Labs has 100+ employees. They have real products that real companies use. Ouster isn't buying them to shut them down or absorb their tech into a black box. Ouster is buying them because the company's CEO, Angus Pacala, has looked at the robotics market and concluded something fundamental: the winner in autonomous systems won't be the company with the best lidar or the best cameras. The winner will be the company with the best integrated perception stack.

This is a shift in thinking that has profound implications. For the last decade, robotics companies treated sensors as interchangeable commodities. You'd spec a lidar unit, a camera, maybe a thermal sensor, and integrate them yourself. The sensor makers competed on specs: resolution, field of view, latency, price. Pure engineering metrics.

But something changed. Maybe it was the rise of AI models that actually work. Maybe it was the realization that self-driving cars aren't shipping anytime soon, so companies had to pivot to shorter-term robotics applications. Maybe it was the maturation of edge computing hardware that made local processing feasible. Whatever the reason, the industry woke up to an uncomfortable truth: sensor data is only valuable if you can fuse it intelligently.

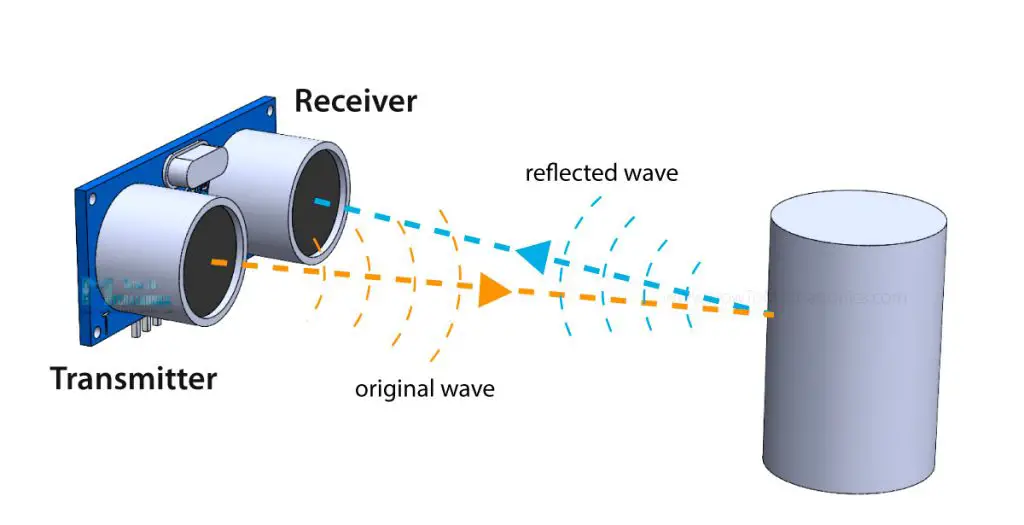

Stereoscopic vision—the ability to determine depth from two offset camera images—is one approach to depth sensing. Lidar is another. Thermal imaging adds another dimension. Time-of-flight sensors add another. The magic isn't in any single modality. The magic is in knowing which one to trust in which situation, and doing that fusion in real-time on edge hardware.

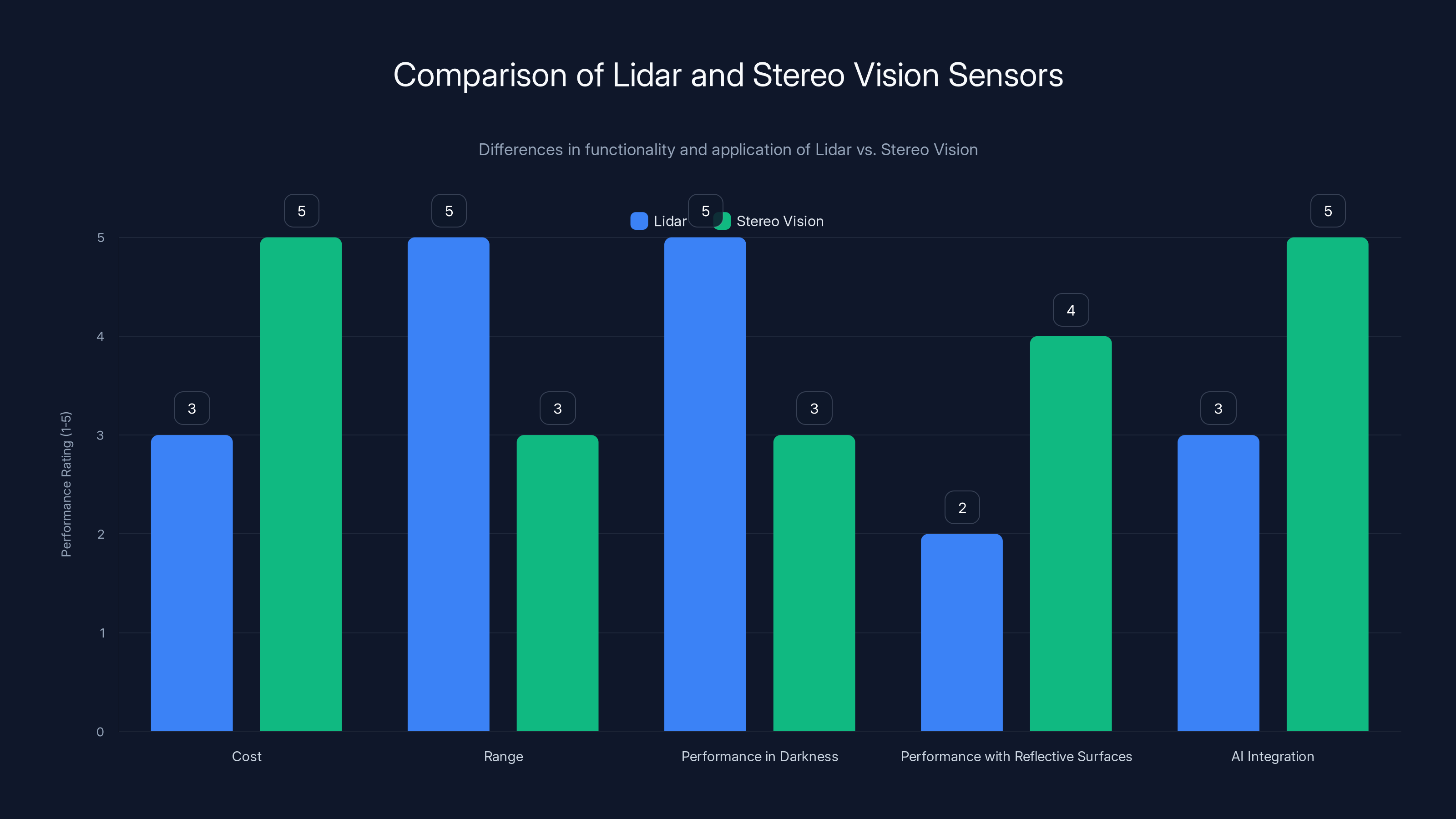

Stereo Labs has spent 15 years building expertise in exactly this. They developed ZED cameras and a software platform around them. More recently, they created foundational AI models that can determine depth from stereo images with remarkable accuracy. This technology is directly complementary to lidar. Where lidar struggles (reflective surfaces, certain weather conditions, objects that are too close), stereo vision excels. Where stereo vision struggles (low-light conditions, very distant objects), lidar takes over.

From Ouster's perspective, buying Stereo Labs isn't about getting another product line. It's about becoming a "tier one" supplier—the kind of company that can sell integrated perception platforms to major OEMs. It's about being able to say, "We'll handle your entire perception problem. One contract. One integration. One company responsible for the whole stack working together."

The Business Model Behind Sensor Consolidation

Let's talk about the economics, because the business model matters more than the hype. Robotics is expensive. Autonomous systems are expensive. And they require certainty. You can't ship a robot to a warehouse and have its perception system fail unexpectedly. You can't deploy an autonomous delivery vehicle and have its lidar cut out in heavy rain. These systems need to be certified, validated, and backed by companies that will still be around in five years.

The sensor industry, as it existed five years ago, couldn't deliver this. You had dozens of lidar companies. Dozens of camera manufacturers. Dozens of perception software startups. None of them had enough scale to invest in safety certifications. None of them had the manufacturing capacity to support major OEM customers. And none of them were integrated enough to guarantee their systems would work together.

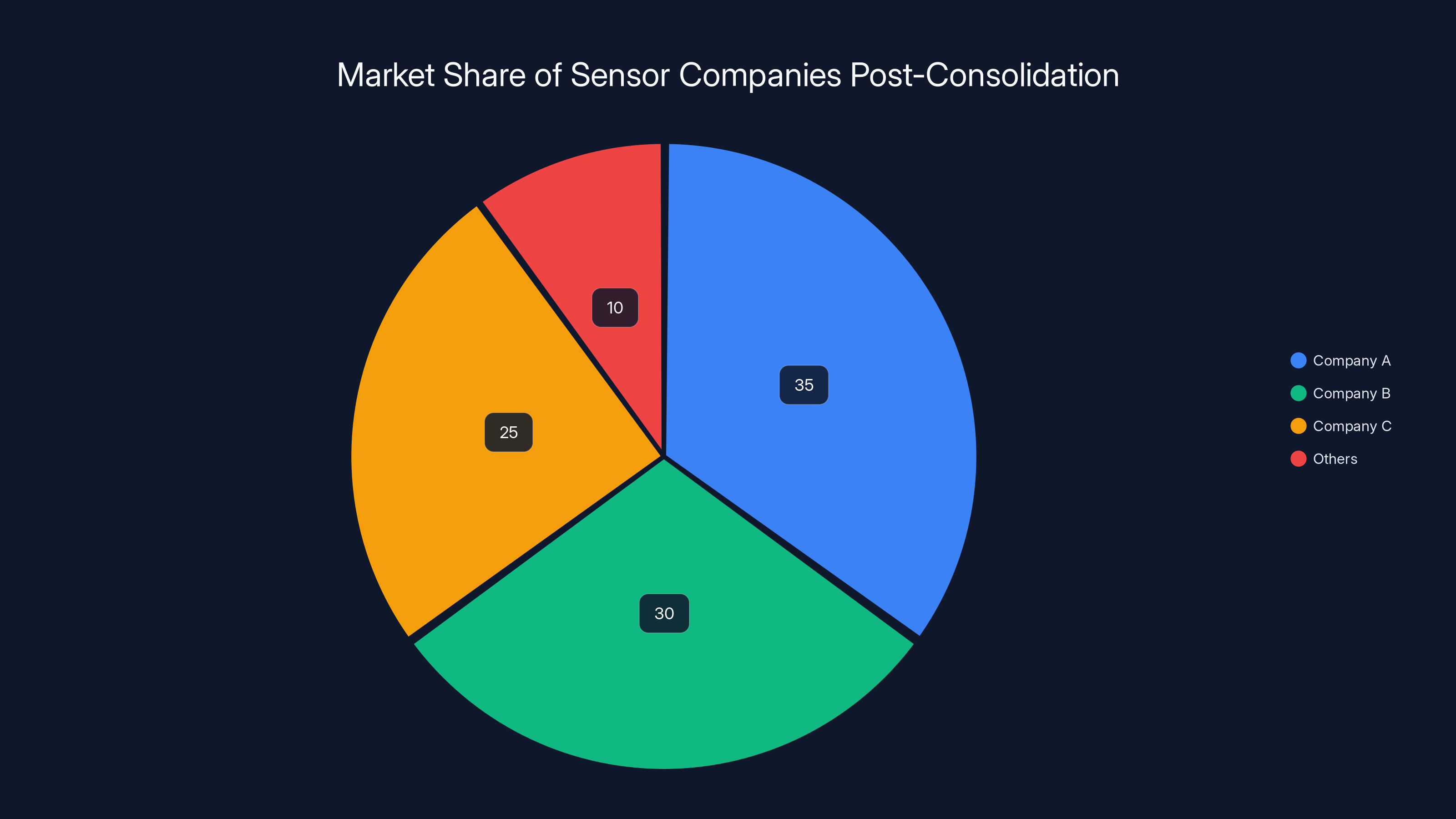

Glen De Vos, CEO of Micro Vision, laid this out bluntly after acquiring Luminar's lidar assets: "You're going to get consolidation, or you're going to get kind of a weeding out of the industry as people fall to the wayside." His reasoning was straightforward. There isn't enough revenue to support all the current competition. Sensor companies are operating on razor-thin margins. The winners will be companies that own multiple modalities and can build integrated systems. Everyone else is just roadkill.

This economic reality is driving the consolidation. It's not glamorous. It's not a story about innovation or breakthrough technology. It's a story about which companies can survive long enough to serve the actual market that's emerging.

Consider the pathway to revenue for a sensor startup. You build a cool new sensor. You get it to market. You're competing on specs and price. But then you realize that most customers don't actually care about the spec. They care about integration. They care about how easily your sensor works with their other systems. They care about whether you'll still be around in five years. They care about certifications and safety documentation.

All of that costs money that a startup doesn't have. So the startup gets acquired by a larger player that has the scale to handle those requirements. Or it fails.

Ouster's strategy is to be the company that wins at this. By acquiring Stereo Labs, they're signaling to major OEMs: "We can be your one perception supplier. We handle lidar, we handle stereo vision, we handle the software fusion layer, and we're big enough and stable enough that you can depend on us."

That's a valuable pitch. And it's worth $35 million to Ouster because it opens up entire customer relationships that would otherwise be out of reach.

Ouster's acquisition of StereoLabs and MicroVision's acquisition of Luminar lidar assets are nearly equal in value, indicating a competitive landscape in sensor consolidation. Estimated data.

Lidar vs. Stereo Vision: Why Ouster Needs Both

To understand why this acquisition makes sense, you need to understand the fundamental differences between lidar and stereo vision, and why neither is a complete solution.

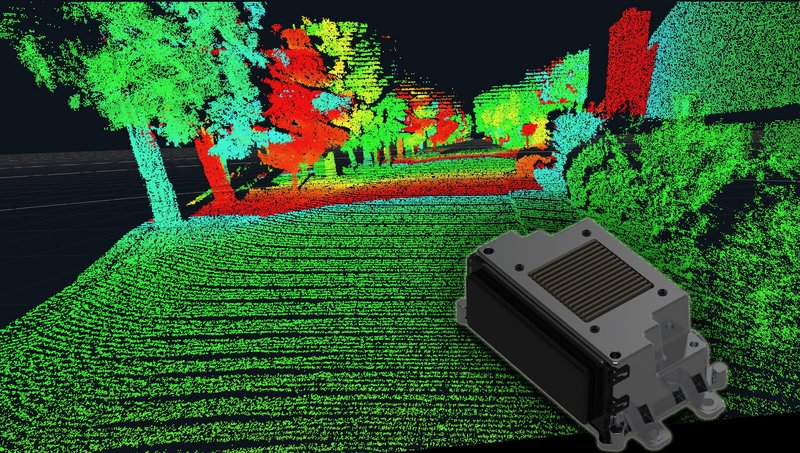

Lidar works by emitting light (usually infrared) and measuring how long it takes to bounce back. It creates a point cloud—essentially a 3D map of everything around it. The advantages are obvious: it works in darkness, it has excellent range, it's relatively immune to lighting conditions. The disadvantages are less obvious but equally real.

Lidar struggles with reflective surfaces. A mirror or a wet road can confuse a lidar system. It struggles with certain materials—glass, for example, can be nearly invisible to lidar. It struggles with very close objects where the reflections overlap. And it's expensive. A decent automotive-grade lidar still costs thousands of dollars. That matters when you're building a robot that needs to be cost-competitive.

Stereoscopic vision works entirely differently. It uses two cameras separated by a baseline distance. The software looks at the same object in both images and uses the disparity between the two views to calculate depth. It's the same mechanism humans use to see in 3D. The advantages are that it's cheap (just cameras and a processor) and it leverages the enormous progress in AI image understanding. The disadvantages are that it struggles in low light, it has limited range, and it can struggle with textureless surfaces (a blank wall, for example, looks the same from both cameras).

Here's the thing: these are almost perfectly complementary weaknesses. Lidar's weaknesses are stereo vision's strengths, and vice versa. A system that could fuse both would be genuinely better than either alone.

This is why Pacala emphasized that Stereo Labs is "best in class" on the hardware side but especially valuable for their AI expertise. Stereo Labs spent years developing models that squeeze every drop of depth information out of stereo cameras. They built inference engines that run on edge hardware. They have a decade-and-a-half of experience making stereo vision actually work in real-world applications.

Ouster spent years building the best lidar hardware they could, with excellent point cloud quality and range. Now they're acquiring the stereo vision expertise to build a complete perception platform.

The software layer is where the real value will come from. Taking a lidar point cloud and a stereo depth map and a regular camera image and fusing them into a single, coherent 3D scene understanding—that's hard. It requires algorithms that understand when to trust each sensor, how to fill in gaps where one sensor is blind, and how to do all of this in real-time on edge hardware. This is where Ouster's investment in Stereo Labs will pay off.

The Rise of Physical AI and What It Actually Requires

Physical AI is the buzzword du jour. Every robotics company uses it. Every investor mentions it. Nobody quite agrees on what it means, which is always a bad sign.

Physical AI generally refers to AI systems that perceive and act in the physical world. This includes humanoid robots, autonomous drones, self-driving vehicles, robotic warehouse systems, and a thousand other applications. The term is deliberately broad because the underlying requirement is the same: you need perception, reasoning, and control working together in real-time.

The perception layer is where the sensor consolidation is happening. Because here's what people sometimes miss: physical AI systems don't need general-purpose intelligence. They need domain-specific intelligence applied to highly constrained problems.

A warehouse robot doesn't need to understand the human condition. It needs to accurately detect boxes, pallets, obstacles, and personnel in a specific environment. A delivery drone doesn't need to chat with you. It needs to know where it is, where it's going, and what obstacles are in the way. A humanoid robot doesn't need to pass the Turing test. It needs to perform specific tasks reliably.

This means the perception requirements are actually quite different from general-purpose computer vision. A warehouse robot can assume there's good lighting (it works indoors), a controlled environment (no weather variations), and a relatively simple visual scene (boxes and pallets). A delivery drone has the opposite constraints: uncontrolled lighting, variable weather, and complex outdoor scenes.

Each application needs a sensor suite tailored to its constraints. And each application needs someone responsible for making sure that sensor suite actually works and continues to work.

This is why consolidation is inevitable. The sensor companies that survive are going to be the ones that can offer integrated solutions for specific applications. Ouster/Stereo Labs can offer a warehouse robotics perception stack. Someone else might offer a delivery drone perception stack. Someone else might focus on autonomous vehicles.

The point is that the companies that try to be everything to everyone—that try to build the world's best sensor without considering how it integrates with other sensors and software—are going to die. There's no market for that. There's only a market for solutions.

Market Pressure: Why Revenue Isn't Enough

One of the clearest statements in Pacala's interview was this: "The business model here is not to just sell the fervor, it's to actually make working systems that are certified, that are safe, that are really solving customer problems."

This is him saying, directly, that the hype cycle is over. Companies that were banking on the "physical AI" trend to carry them are going to be disappointed.

Here's the hard truth about hardware startups: revenue is necessary but not sufficient. A company can have millions in annual revenue and still not be viable, because the margins on hardware are brutal. If you're selling a sensor for

Sensor startups typically operate on 30-40% gross margins if they're doing well. That leaves very little room for R&D, customer support, manufacturing overhead, and everything else. The only way to be profitable is to achieve significant scale.

But the market doesn't want dozens of sensor companies at scale. The market wants a few trusted suppliers. So the math is simple: most of the current sensor companies won't achieve scale, which means they won't be profitable, which means they'll eventually run out of money. The only way to avoid that fate is to be acquired by a larger company that already has scale in adjacent areas.

This is what Pacala meant when he said, "There's going to be a little bit of disillusionment in physical AI." He's not saying the market won't grow. He's saying the hype will exceed reality for a few years, during which a lot of companies will burn through their cash, and the industry will consolidate around the players who were willing to build real products instead of chasing hype.

Ouster's strategy is explicitly to be one of those remaining players. By acquiring Stereo Labs, they're consolidating capacity, spreading R&D costs over more products, and building a more defensible market position. They're betting that in five years, there will be maybe three or four sensor companies left, and Ouster will be one of them.

This chart compares Lidar and Stereo Vision sensors across various characteristics. Lidar excels in range and darkness, while Stereo Vision is more cost-effective and integrates AI better. Estimated data.

Ouster's Acquisition History and M&A Strategy

Ouster has been on a consolidation spree for years. To understand where the company is going, you need to understand where it's been.

In 2022, Ouster merged with Velodyne, another major lidar manufacturer. This was a critical move. Velodyne was the lidar incumbent—the company that basically invented the category. Ouster was the young upstart with better technology and lower costs. The merger combined Ouster's engineering talent and cost structure with Velodyne's customer relationships and market position.

Before the Velodyne merger, Ouster acquired Sense Photonics, a company working on solid-state lidar. Sense Photonics had been struggling to bring their technology to market, but their core technology was valuable. By acquiring them, Ouster gained expertise in solid-state design and a portfolio of valuable patents.

Now with Stereo Labs, Ouster is moving into vision systems. The pattern is clear: Ouster is building a perception company, not a lidar company. The lidar business was the entry point, but the end goal is to be the company that can supply an entire perception stack to major OEMs.

This is a smart strategy for Ouster specifically because they already have:

- Manufacturing infrastructure (inherited from Velodyne)

- Customer relationships with major automotive and robotics companies

- A publicly traded status and the currency to make acquisitions

- Brand recognition in the autonomous systems space

Stereo Labs is the ideal next acquisition because it gives them the vision layer they needed, plus a company with a different customer base and distribution model. Ouster's customers are automotive and robotics OEMs. Stereo Labs' customers are more diverse—everything from drone manufacturers to industrial inspection systems to academic research.

When you put those customer bases together, you have a much stronger market position. You can now go to a major OEM and say, "We can supply your entire perception system. Lidar, cameras, software fusion, edge processing, the works."

That's worth far more than the sum of the parts.

Stereo Labs: The Acquisition Target

Why Stereo Labs specifically? Why not acquire some other vision company?

Pacala mentioned that he'd "been eyeing Stereo Labs for years." That's the kind of thing executives say when they mean they've had the company on their radar for a long time, watching how they operate, how they execute, whether they're the kind of company they'd want to work with.

Stereo Labs is a relatively unusual company in the robotics ecosystem. Most vision companies either go high-end (expensive, specialized, niche) or low-end (cheap, general-purpose, commodity). Stereo Labs tried to stake out the middle ground. Their ZED cameras weren't the absolute cheapest, but they weren't expensive either. They came with a software stack that made them useful for robotics applications.

More importantly, Stereo Labs has always been serious about the perception problem. While other vision companies were trying to sell hardware or sell software licensing, Stereo Labs was trying to solve the actual problem of giving robots and drones effective depth sensing. They invested in understanding the specific challenges that roboticists face. They built a developer community. They worked with customers to understand what actually works in the real world.

That's harder than it sounds. It requires patience, technical depth, and a willingness to admit when your first approach doesn't work. Stereo Labs did all of that.

Pacala specifically highlighted Stereo Labs' work on foundational AI models for depth estimation. This is their recent pivot: instead of just providing hardware and tools, they're building the AI models that actually extract useful information from stereo images. This puts them at the forefront of the convergence between classical computer vision and deep learning—the exact place where the most valuable technology is being developed.

For Ouster, this is exactly what they need. Ouster can contribute the lidar expertise, the manufacturing scale, and the customer relationships. Stereo Labs can contribute the stereo vision expertise, the perception algorithms, and the AI models. Together, they have much more firepower than either one alone.

The

The Competitive Response: Micro Vision and Others

Ouster isn't alone in this consolidation play. Micro Vision's acquisition of Luminar's lidar assets is the mirror-image move in the market.

Luminar was one of the more interesting lidar startups. They had great technology, significant funding, and an impressive team. But they hit the wall that all sensor startups eventually hit: building great hardware isn't enough. You need a path to profitability, which requires either enormous scale or a strategic acquirer.

Luminar chose to divest its lidar business to Micro Vision and refocus on automotive software and perception integration. This makes sense for Luminar because they were trying to serve the autonomous vehicle market, which has been moving slower than anyone expected. By divesting the expensive lidar business and focusing on software, they can be more capital-efficient.

For Micro Vision, buying Luminar's lidar assets is a way to fill a gap in their portfolio. Micro Vision's core business is in MEMS (micro-electromechanical systems) technology, which is useful for solid-state perception systems. By acquiring Luminar's lidar IP and team, they can accelerate their move into the lidar market.

These two acquisitions—Ouster buying Stereo Labs and Micro Vision buying Luminar's lidar assets—are part of a broader pattern of consolidation in the perception sensor space. The companies that are consolidating are trying to build integrated platforms. The companies that are being acquired are either struggling to achieve scale or pivoting to where they think the real value is.

This pattern is likely to continue. Expect to see more consolidation, more M&A activity, and more companies either being acquired or failing. The winners will be the companies that understood early that sensor hardware is becoming commoditized, and that the real value is in the software, the integration, and the customer relationships.

Estimated data shows that post-consolidation, a few key players dominate the sensor market, with Company A leading at 35% market share.

The Role of Edge Computing and Inference

One of the most important but least-discussed aspects of the perception consolidation is edge computing. Because here's the thing: collecting sensor data is easy. The hard part is processing it in real-time on the robot itself, not sending it to the cloud.

For many robotics applications, you can't afford to send video data to the cloud and wait for a response. A warehouse robot needs to know right now what's in front of it. A delivery drone needs to know right now how to navigate around obstacles. That means all the processing has to happen on the device, with only a tiny amount of compute resources.

Edge AI inference is still relatively new. The models need to be small (maybe 1-10 gigabytes, not 100+ gigabytes). They need to be fast (inference in milliseconds, not seconds). And they need to be accurate enough for the specific application.

This is where Stereo Labs' expertise becomes valuable. They've spent years optimizing stereo depth models to run on edge hardware. They know how to squeeze maximum performance out of resource-constrained devices. When you combine that with Ouster's experience in real-time lidar processing, you have a team that can build a truly integrated perception pipeline that runs locally.

The industry trend is clear: as edge AI gets better, the amount of data that needs to be sent to the cloud decreases. This means robots become more autonomous and require less cloud connectivity. This changes the business model—you're no longer selling a robot that depends on cloud services. You're selling a truly autonomous robot.

Ouster's acquisition of Stereo Labs is partly about positioning themselves at the center of this shift. They want to be the company that supplies the perception hardware and software that makes effective edge AI possible.

Manufacturing and Supply Chain Considerations

When a hardware company acquires another hardware company, manufacturing and supply chain are critical. You can't just merge the technology and call it done. You need to actually manufacture the products, which means dealing with suppliers, managing inventory, ensuring quality control, and handling logistics.

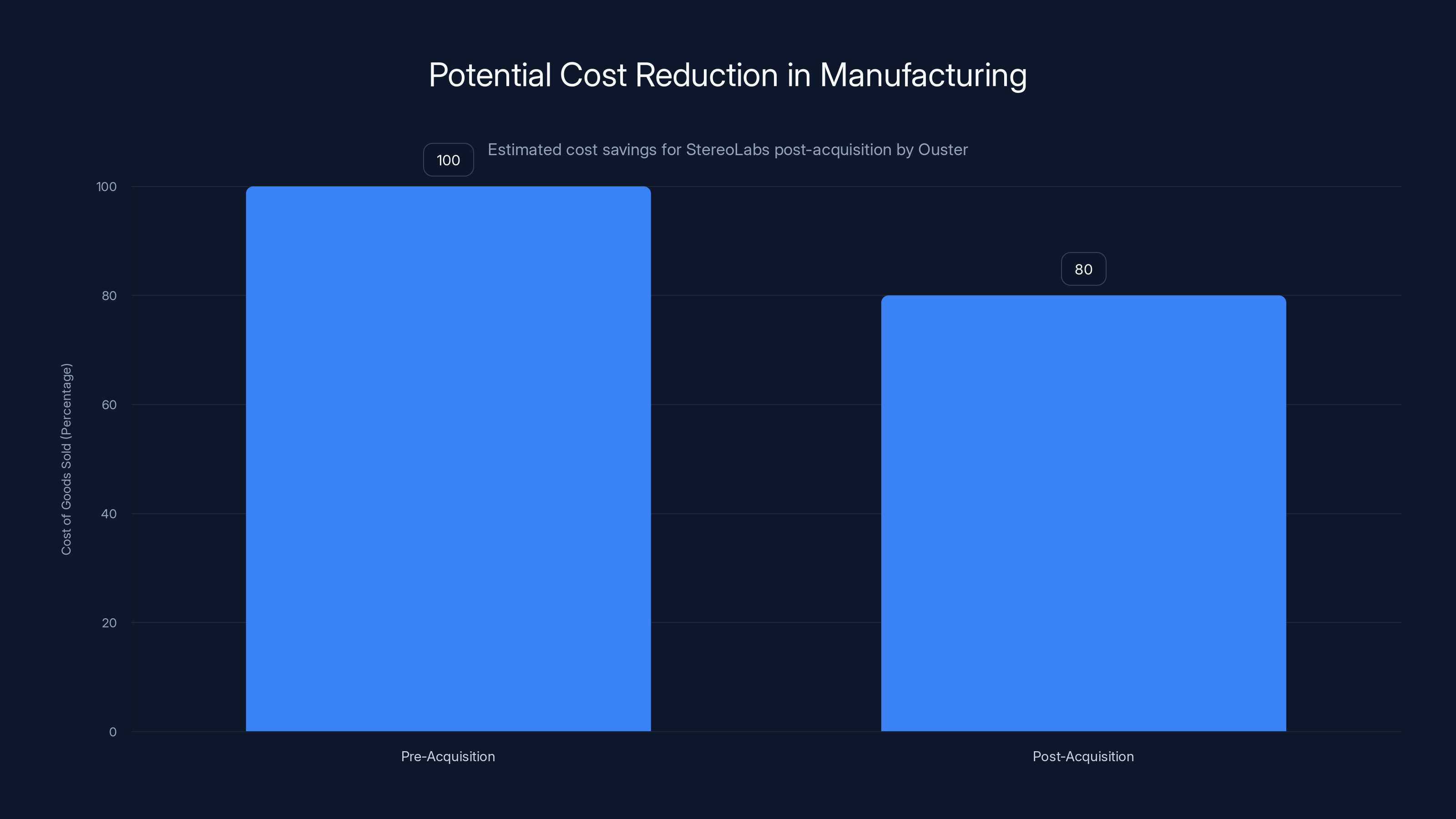

Ouster already has significant manufacturing infrastructure from the Velodyne merger. They have relationships with component suppliers. They have manufacturing partners in multiple countries. This is valuable because it means they can scale Stereo Labs' production without starting from scratch.

Stereo Labs will likely operate as a subsidiary, which makes sense from a manufacturing perspective. They keep their own supply chain, their own manufacturing partners, their own quality control processes. But they can leverage Ouster's scale to negotiate better component pricing and coordinate supply chain activities.

This is one of the less-sexy reasons for the acquisition, but it's genuinely important. Manufacturing efficiency is often the difference between a company that's profitable and one that isn't. Ouster can probably reduce Stereo Labs' cost of goods sold by 10-20% just by leveraging their scale and supplier relationships.

Over time, as the two companies integrate their product lines, you'd expect to see more consolidation of manufacturing. But that takes time and carries risk—you don't want to disrupt Stereo Labs' operations in the critical early period after acquisition.

Product Integration: The Next Challenge

Here's where things get tricky. Ouster and Stereo Labs have different product lines, different customers, and different distribution channels. The acquisition makes strategic sense, but the actual product integration is going to be messy.

In the near term, Ouster is likely to leave Stereo Labs largely unchanged. They'll keep the ZED cameras on the market, keep supporting their current customers, and keep their own software stack alive. But over time, they'll start to look at how they can integrate.

Maybe ZED cameras will get built-in support for Ouster lidar fusion. Maybe there will be a unified SDK that makes it easy to use both Ouster and Stereo Labs sensors together. Maybe there will be reference implementations for specific robotics applications.

This kind of integration takes time. You need to build the software, test it with real customers, iterate based on feedback, and make sure you don't break anything. Customers have existing code that depends on Stereo Labs' APIs. You can't just break that for the sake of integration.

But the goal is clear: over the next few years, Ouster and Stereo Labs will become progressively more integrated. They'll move from being two separate companies that share an owner to being one integrated perception platform that happens to be sold under two brand names (at least initially).

This is a multi-year project. But it's the kind of project that $35 million buys you the option to pursue. You're not acquiring Stereo Labs for what they are. You're acquiring them for what they could become once they're integrated with Ouster's capabilities.

Estimated data: Ouster's acquisition could reduce StereoLabs' cost of goods sold by 10-20% through improved supplier negotiations and manufacturing efficiencies.

The Hype vs. Reality Problem

Pacala made a point of tempering expectations about physical AI, and it's worth dwelling on because it cuts to the heart of why consolidation is happening.

Physical AI is hot. Humanoid robots are hot. Autonomous systems are hot. There's a lot of venture capital chasing these opportunities. But capital and market reality are two different things.

The reality is that deploying autonomous systems at scale is hard. Really hard. A warehouse robot needs to work reliably for years. A delivery drone needs to navigate in weather and traffic. A humanoid robot needs to handle task variation and unexpected situations.

All of this requires not just cool technology, but boring stuff: testing, validation, certification, safety documentation, customer support, etc. The companies that survive in this space are the ones that are willing to do the boring stuff.

Startups are generally bad at boring stuff. They want to move fast and break things. But when you're dealing with physical systems that interact with the real world, you can't afford to break things. A failed warehouse deployment means the customer's operation goes down. A failed drone means you lose expensive equipment and potentially hurt someone.

This is why consolidation favors large companies. Ouster has the resources to do all the boring stuff. They can invest in safety certifications. They can maintain multiple product lines. They can support customers with 24/7 technical support. They can operate at breakeven for years if necessary to achieve scale.

Startups generally can't do any of that. So they either get acquired or they fail.

Pacala's comment about disillusionment in physical AI is him saying: we're in the hype phase now, but reality is coming. Companies that have bet on hype are going to be disappointed. Companies that have bet on building real solutions are going to do well.

Safety, Certification, and Regulatory Requirements

One of the things that gets glossed over in discussions of autonomous systems is that they're increasingly regulated. You can't just ship a robot and hope it works. You need to demonstrate that it's safe.

This is especially true in areas like autonomous vehicles, where there's significant regulatory scrutiny. But it's also true for industrial robots, delivery drones, and any system that operates in spaces where humans are present.

Safety certification takes years and costs millions. You need to test your system under a wide range of conditions. You need to document all your testing. You need to demonstrate that you've thought through failure modes. You need to get independent audits. You need to carry liability insurance.

This is exactly the kind of thing that large, established companies can do but startups struggle with. Ouster has already gone through much of this process. By acquiring Stereo Labs and integrating their technology, Ouster can extend their certifications and regulatory approvals to cover the new integrated system.

This is worth a significant amount of money. If you're a robotics company choosing between integrating five different sensor providers (each with their own certification status) or buying from Ouster (one certified provider with an integrated stack), you're going to choose Ouster. It's less work, less risk, and you have one company to sue if something goes wrong.

Safety and certification are likely to be a major moat for the companies that survive consolidation. By the time the next wave of startups emerge, the regulatory bar will be even higher, and it will be even harder for them to compete with established players that already have certifications in place.

What Happens to Stereo Labs as a Subsidiary?

Ouster said Stereo Labs will operate as a wholly-owned subsidiary. This is important because it signals that Ouster isn't planning to immediately merge the operations.

In practice, this usually means:

- Stereo Labs keeps its own management structure and brand

- Stereo Labs continues to serve its existing customers under the ZED brand

- Stereo Labs' product roadmap gets aligned with Ouster's overall strategy, but they maintain some autonomy

- Over time, there's increasing integration at the technical level

- Eventually, the subsidiary structure becomes less meaningful as the companies become more tightly integrated

This approach is actually smart. It allows Ouster to avoid disrupting Stereo Labs' existing business while they figure out how to integrate the two companies. If Ouster came in immediately and tried to consolidate everything, they'd risk losing Stereo Labs' key talent and damaging relationships with customers who are wary of being acquired.

By keeping Stereo Labs as a subsidiary, Ouster is buying time to do the integration properly. It also gives Stereo Labs some protection from Ouster's corporate culture, which is important for a company that has built its reputation on close relationships with customers and developers.

Over the next 2-3 years, you should expect to see:

- Joint customer engagements where Ouster and Stereo Labs work together

- Technical collaboration on sensor fusion and perception algorithms

- Potential co-marketing to new customer segments

- Gradual rationalization of product lines as duplicative functionality is removed

- Eventual integration of sales and support functions

But these changes will happen gradually, not overnight. That's how successful acquisitions are managed in hardware.

As sensor consolidation progresses, IPO exits are projected to decrease, while acquisition exits are expected to grow, reflecting a shift in VC strategies. Estimated data.

The Sensor Consolidation Endgame

If you step back and look at the pattern, it's clear where this is heading. In five years, there will be maybe 5-10 major sensor companies left in the perception space. The rest will either be acquired or bankrupt.

Ouster and Micro Vision are positioning themselves to be among the survivors. They're consolidating capacity, acquiring expertise, and building integrated platforms. Other companies like Intel/Real Sense, Sony, and the Chinese camera companies will continue to be players based on their scale and existing customer bases.

But the pure-play sensor startups? Most of them won't make it. They'll run out of capital, fail to achieve meaningful scale, or get acquired at distressed valuations.

The winners will be companies that:

- Achieved early scale and used it to build sustainable unit economics

- Integrated multiple modalities into a cohesive platform

- Invested in the boring stuff: certification, support, documentation

- Built relationships with major OEMs that give them strategic importance

- Have the financial resources to invest in the next generation of technology

Ouster is betting that they're one of those winners. The Stereo Labs acquisition is a move in that direction. But the game isn't over. There are still a lot of moves left to be made.

Implications for Robotics Companies Building Physical AI

If you're a robotics company building autonomous systems, this consolidation matters to you. A lot.

Five years ago, you could spec out sensors from five different vendors, integrate them yourself, and build a working perception system. It was a lot of work, but it was possible. Today, that approach is increasingly untenable. It's too much work, too much risk, and you're managing too many vendor relationships.

In the future, you'll probably want to buy from one or two sensor providers that can give you an integrated stack. Ouster is positioning itself to be one of those providers.

This is good news and bad news. The good news is that sensor integration becomes someone else's problem. You can focus on your robot's actual task, not on fusing lidar and camera data. The bad news is that you're increasingly dependent on a handful of vendors for critical infrastructure.

For companies choosing sensor providers, the consolidation means:

- Fewer options, but each option is stronger

- Better integration and support from your chosen vendor

- Risk of vendor lock-in if you heavily integrate with a proprietary platform

- Need to move earlier if you want to avoid being dependent on a dominant vendor

If you're starting a robotics company today, you're probably going to use either Ouster or Micro Vision (or one of the Chinese alternatives) for your perception system. You're not going to integrate five different point solutions.

This is a major shift from the startup mentality of 5 years ago. But it's the direction the industry is moving.

Future Consolidation: Where Does It Go From Here?

If Ouster and Micro Vision are consolidating around integrated perception platforms, what's next?

Likely scenarios:

Thermal imaging integration: So far, the consolidation has focused on lidar and visible light cameras. But thermal imaging is valuable for certain applications (night vision for drones, heat leak detection for industrial systems). One of the big consolidation plays will probably involve thermal sensors.

Radar integration: Radar is underutilized in robotics but valuable for long-range detection and velocity measurement. A company that figures out how to fuse radar with lidar and cameras will have a significant advantage.

AI software platforms: So far, the focus has been on hardware and sensor fusion. But the next wave of consolidation might be about AI models and reasoning engines. A company that can supply both perception hardware and AI reasoning software will be very defensible.

Vertical integration: The companies that survive might integrate upward into robotics applications, or downward into component manufacturing. Ouster could eventually own the entire stack from component manufacturing to finished robotic systems.

China plays: Chinese sensor manufacturers are investing heavily in autonomous systems. It's possible that the endgame consolidation happens at the China/West division—Chinese companies consolidating around their own sensor and AI platforms, Western companies consolidating around theirs.

Any or all of these could happen over the next 5-10 years. The key point is that the consolidation we're seeing with Ouster and Micro Vision is just the beginning. More moves are coming.

The Economics of Scale in Hardware

One reason hardware consolidation is inevitable is that hardware economics are fundamentally different from software economics.

Software scales nicely. If you build great software, you can sell it to a million customers with almost no incremental cost. The first customer might cost you

Hardware is the opposite. Every unit you manufacture has a cost. If you have

This is why sensor companies need scale. Without scale, they can't achieve the unit economics they need to be profitable. The companies that achieve scale can then invest in the next generation of technology and pull ahead of the competition.

Consolidation accelerates scale. By combining two companies with

This is the story of hardware consolidation across industries. In memory chips, we went from dozens of manufacturers to a handful of giants. In hard drives, the same thing. In sensors, we're in the middle of that consolidation right now.

Ouster's acquisition of Stereo Labs is a move in the direction of scale. It's not a revolutionary move, but it's a sensible one given the economics of the hardware business.

Investor Perspective: Why This Matters to VCs

From an investor perspective, the consolidation in sensors changes the venture capital game.

Five years ago, VCs could invest in a sensor startup, hope they achieved scale quickly, and either take them public or sell them to a larger company. The returns could be very large if the startup happened to be the one winner in the space.

But the odds were terrible. For every sensor startup that succeeded, dozens failed. The ones that succeeded often did so because they got lucky—they happened to pick a sensor modality that turned out to matter, at exactly the time when the market was ready for it.

Sensor consolidation reduces the size of the prize but also reduces the variance. Instead of betting on a winner-take-all dynamic, investors should be thinking about whether a sensor startup can be acquired at a reasonable valuation by one of the consolidating giants.

This changes the exit strategy for sensor startups. Instead of aiming for a

For investors, this means the venture sensor space will probably shrink over the next few years. The majors (Ouster, Micro Vision, etc.) will do a handful of strategic acquisitions. But the gold-rush mentality of investing in any sensor startup will fade as reality sets in.

The next generation of venture capital in the autonomous systems space is probably going to focus on applications (robots, drones, vehicles) rather than sensors. The sensor layer is becoming more of a commodity, supplied by larger, more established companies.

Conclusion: The Inevitable Consolidation

Ouster's acquisition of Stereo Labs for $35 million isn't a one-off event. It's part of a fundamental shift in how the perception sensor industry is organizing itself.

The physical AI boom is real, but it's not as simple as the hype cycle suggests. Building working autonomous systems requires integrated perception platforms, not point solutions. It requires companies with the scale to invest in safety and certification. It requires software expertise, not just hardware engineering.

The sensor companies that survive are the ones that understand this. Ouster clearly understands it. Micro Vision understands it. The sensor companies that think they can win by just building the best individual sensors are going to find themselves increasingly marginalized.

For robotics companies building physical AI systems, this consolidation is actually good news. You're no longer forced to manage relationships with five different sensor vendors. You can buy an integrated perception platform from one vendor and focus on your core value proposition.

But it's also a reminder that in hardware, there's no such thing as a temporary winner. The companies that achieve scale early and use that scale to integrate and improve will likely be the ones that are around in ten years. Everyone else is just renting their market position until someone bigger comes along and consolidates the sector.

Ouster is making a bet that they're going to be one of the survivors. The Stereo Labs acquisition is part of that bet. It's a smart move, and it probably won't be the last move in a rapidly consolidating market.

FAQ

What is Ouster's business model after the Stereo Labs acquisition?

Ouster is transitioning from being primarily a lidar company to becoming an integrated perception platform supplier. After acquiring Stereo Labs, Ouster now supplies lidar sensors, stereo vision cameras, edge processing software, and AI fusion algorithms. The goal is to be a "tier one" supplier that can provide an entire perception stack to major OEMs and robotics companies, rather than just individual sensors.

How does sensor consolidation benefit robotics companies building autonomous systems?

Sensor consolidation benefits robotics companies by reducing complexity and risk. Instead of integrating five different sensor vendors with separate APIs, documentation, and support channels, robotics companies can now buy an integrated perception platform from one supplier. This reduces engineering effort, improves reliability, and ensures that the entire perception system is certified and supported by a single company.

Why is Stereo Labs valuable to Ouster beyond just acquiring another camera product?

Stereo Labs is valuable to Ouster primarily because of their expertise in edge AI inference and depth estimation algorithms. Stereo Labs spent 15 years optimizing stereo vision to run efficiently on resource-constrained devices. They built foundational AI models that can extract depth information from stereo images with high accuracy. This expertise is directly complementary to Ouster's lidar hardware and will enable Ouster to build sensor fusion pipelines that run locally on robots rather than relying on cloud processing.

What's the difference between lidar and stereo vision sensors and why does a company need both?

Lidar works by emitting infrared light and measuring reflections, which works well in darkness and has good range but struggles with reflective surfaces and glass. Stereo vision uses two cameras and AI to determine depth, which is cheap, leverages AI progress, and works well indoors but struggles in low light and has limited range. The two sensors have almost perfectly complementary weaknesses, so combining them creates a more robust perception system than either alone.

Is the sensor consolidation trend likely to continue?

Yes, consolidation in the perception sensor space is likely to accelerate. As Ouster's CEO acknowledged, there isn't enough revenue to support all the current sensor companies. Over the next 5-10 years, the industry will consolidate from dozens of companies to perhaps 5-10 major players. Companies will either achieve scale and consolidate around integrated platforms, or they'll run out of capital and fail. Smaller sensor startups will either be acquired at reasonable valuations or struggle to survive.

How does edge AI influence the sensor consolidation strategy?

Edge AI is a key driver of consolidation because autonomous systems increasingly need to process sensor data locally on the device rather than sending it to the cloud. This requires optimized inference engines, model compression techniques, and deep expertise in running AI on resource-constrained hardware. Stereo Labs' expertise in edge inference, combined with Ouster's real-time lidar processing, enables the development of sensor fusion pipelines that run entirely locally on robots, making them truly autonomous and reducing cloud dependency.

What happens to customers who currently use Stereo Labs products after the acquisition?

Ouster has committed to operating Stereo Labs as a wholly-owned subsidiary, which means existing ZED camera products and their software platforms will continue to be supported. In the short term, nothing changes for current Stereo Labs customers. Over time, Ouster will likely integrate Stereo Labs' technology with their lidar offerings, but this will be done gradually to avoid disrupting existing customer relationships.

How does this acquisition compare to Micro Vision's acquisition of Luminar's lidar assets?

Both acquisitions represent different consolidation strategies. Ouster is consolidating by adding vision capabilities to their lidar platform, creating a more complete perception solution. Micro Vision is consolidating by acquiring lidar IP and talent to complement their existing MEMS technology. Both companies are attempting to build integrated perception platforms, but approaching it from different starting points. Together, these acquisitions signal that the industry is moving toward integrated platform suppliers rather than point solution manufacturers.

Why does physical AI require consolidated sensor suppliers instead of best-of-breed point solutions?

Physical AI systems need reliable, certified, integrated perception to operate autonomously in the real world. Integrating multiple independent sensor vendors is complex, adds points of failure, and makes it difficult to achieve the certifications required for safety-critical applications. A consolidated supplier can guarantee that all sensors work together reliably, provide unified documentation and support, and stand behind the entire system's safety and performance. This reduces risk and engineering burden for companies building robots and autonomous systems.

What is the timeline for realizing value from the Ouster-Stereo Labs integration?

Ouster indicated that Stereo Labs will initially operate as a separate subsidiary while integration happens gradually. The immediate benefits come from cost synergies in manufacturing and supply chain. Technical integration—building unified sensor fusion software and co-developed products—will likely take 2-3 years. Full product integration and customer relationship consolidation will probably take 3-5 years. The long-term strategic value comes from having an integrated perception platform that can compete effectively for tier-one OEM contracts.

Moving Forward

The sensor consolidation trend we're seeing with Ouster, Micro Vision, and others is fundamentally reshaping the robotics and autonomous systems landscape. If you're building physical AI systems, you need to understand that the sensor layer is becoming increasingly consolidated. The companies providing sensors are becoming platform providers rather than component suppliers.

For developers and companies choosing perception solutions, this means paying close attention to which companies are building true integrated platforms versus which ones are just bolting together point solutions. The winners will be those who think about perception as a complete stack—hardware, software, edge processing, and AI—rather than individual components.

Key Takeaways

- Ouster acquired StereoLabs for $35M plus 1.8M shares to build an integrated perception platform combining lidar and stereo vision technology

- Sensor consolidation is accelerating because hardware companies can't support diverse point solutions; integrated platforms are becoming industry standard

- Lidar and stereo vision have complementary weaknesses, making sensor fusion architectures fundamentally more capable than either modality alone

- Edge AI inference enables robots to process sensor data locally, and this technology complexity is driving consolidation around companies with deep expertise

- Industry will likely consolidate from 20+ competitors to 5-10 major sensor suppliers within 5 years based on capital requirements and scale economics

- Physical AI applications require certified, integrated systems—not hype-driven point solutions—favoring large, established companies over startups

- Robotics companies building autonomous systems should expect to choose from consolidated sensor suppliers rather than integrating multiple vendors

Related Articles

- Tesla is No Longer an EV Company: Elon Musk's Pivot to Robotics [2025]

- Robot Mowers & AI: From Cordless to "Senseless Intelligence" [2025]

- How Digital Technology Solves UK Manufacturing's Workforce Crisis [2025]

- Network Modernization for AI & Quantum Success [2025]

- How 16 Claude AI Agents Built a C Compiler Together [2025]

- Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models: Smarter Imitation Learning [2025]

![Lidar & Vision Sensor Consolidation Boom [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/lidar-vision-sensor-consolidation-boom-2025/image-1-1770669537036.jpg)