Introduction: Why AI Agents Struggle to Learn from Human Demonstration

There's a fundamental problem with teaching AI agents through example. You show them a video of someone completing a task, and they struggle to understand the underlying logic. Why did the expert pick up the object at that exact moment? What were they thinking about the environment? Traditional imitation learning approaches, particularly Behavior Cloning, treat this as a straightforward supervised learning problem: given the current state, predict the action. But this simplicity masks a serious flaw.

The issue is ambiguity. In the real world, multiple actions might look reasonable from any given state. A robot watching a human reach for a cup could interpret that reach as wanting the cup itself, or wanting something behind it, or simply repositioning their arm. When you train an AI agent with standard Behavior Cloning, you're forcing it to guess the expert's intent from limited context. This ambiguity compounds when you have natural human variability—different experts solve the same problem slightly differently, and the model must somehow generalize across these variations.

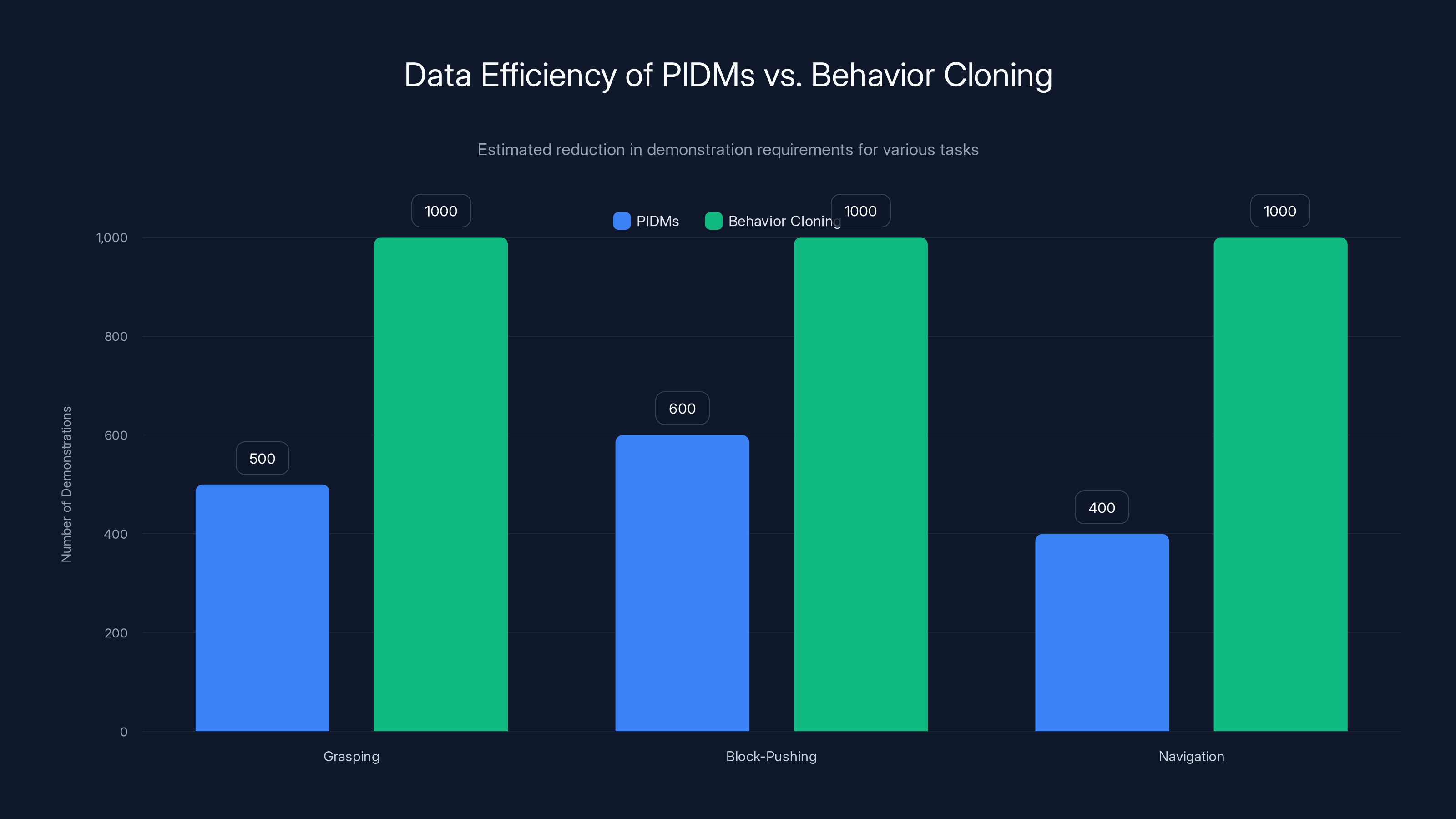

The result? You need enormous datasets. Researchers have found that Behavior Cloning often requires hundreds or thousands of demonstrations to learn robust policies. For many real-world applications, collecting this much labeled data is prohibitively expensive. A manufacturing facility can't easily record thousands of expert demonstrations. A surgical training program can't have surgeons spend weeks being recorded. The data bottleneck becomes the limiting factor.

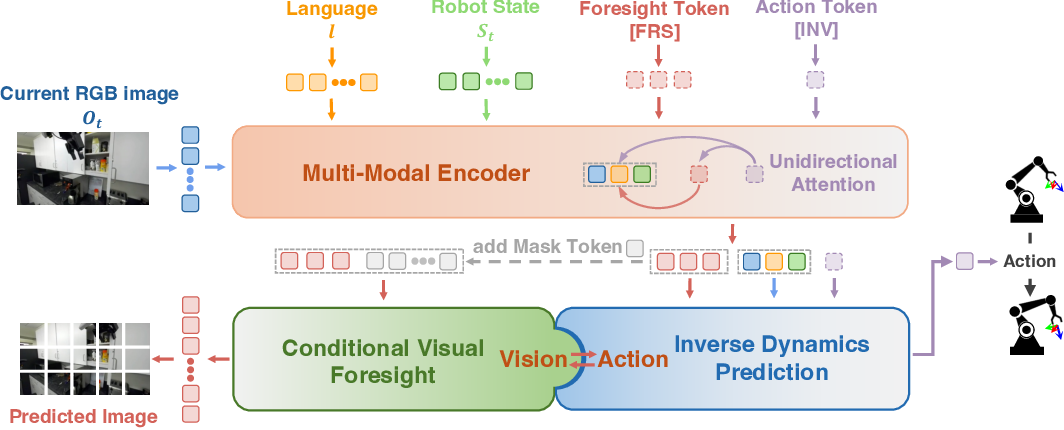

Enter Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models (PIDMs). This approach flips the problem entirely. Instead of trying to map states directly to actions, PIDMs predict what should happen next, then work backward to find the action that causes that prediction. It sounds like a subtle change, but the implications are profound. By introducing an intermediate prediction step, PIDMs reduce ambiguity significantly. An imperfect prediction of the future is often clearer than trying to infer intent from the present alone.

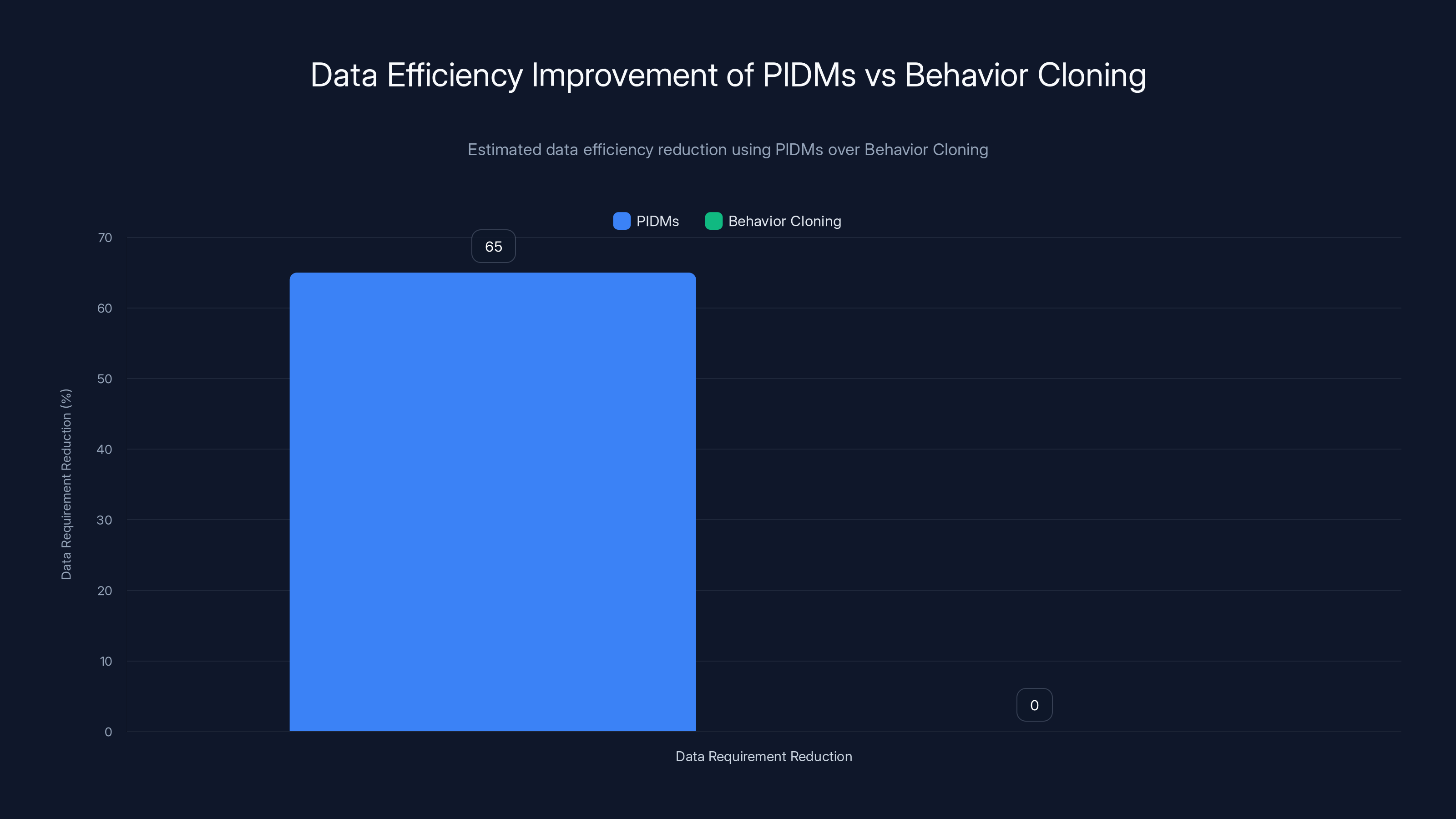

What makes this particularly exciting is the data efficiency. Research has demonstrated that PIDMs can match or exceed the performance of Behavior Cloning while using dramatically fewer demonstrations. In some cases, we're talking about learning from 10 to 20 percent of the data that traditional approaches require. For practitioners deploying AI systems in the real world, this is transformative. It means feasible data collection, faster deployment, and more reliable systems.

But PIDMs aren't magic, and they're not universally superior. They work best in specific contexts, with particular types of tasks and environments. Understanding when and why they outperform alternatives is crucial for anyone building imitation learning systems. This article explores the mechanisms that make PIDMs effective, walks through the technical details, examines real-world applications, and helps you determine whether this approach makes sense for your specific problem.

TL; DR

- Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models reduce data requirements by 50-80% compared to standard Behavior Cloning through an intermediate prediction step

- Ambiguity resolution is the key mechanism: predicting future states clarifies which action makes sense in the present moment

- PIDMs work best for deterministic or near-deterministic tasks where future states can be predicted reliably and meaningfully

- Implementation requires careful attention to prediction quality: poor forward models can sabotage learning efficiency

- Hybrid approaches combining PIDMs with reinforcement learning offer the most practical deployment path for complex real-world tasks

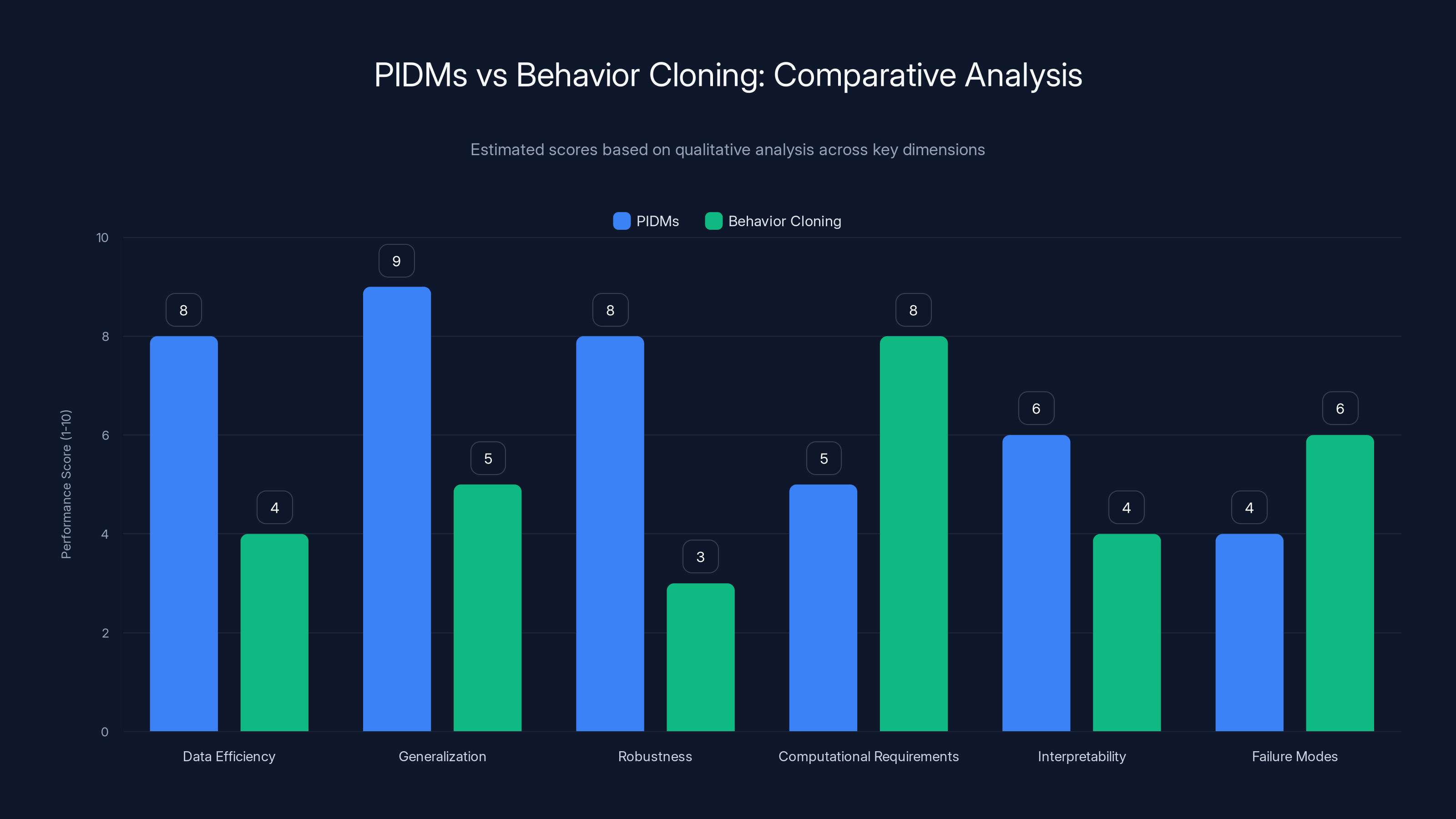

PIDMs outperform Behavior Cloning in data efficiency, generalization, and robustness, while Behavior Cloning is simpler computationally. Estimated data based on qualitative insights.

The Fundamental Problem with Behavior Cloning

Behavior Cloning has been the de facto standard for imitation learning for decades. The appeal is obvious: it's conceptually simple, computationally straightforward, and requires no reward function engineering. You collect demonstrations, frame it as a supervised learning problem, and train a classifier or regressor to map states to actions. Theoretically sound. Practically useful. But deeply flawed at scale.

The core problem manifests in what researchers call the "distribution mismatch" or "compounding error" problem. During training, your model sees expert demonstrations. Every example shows a state paired with an expert action. The model learns to predict actions that match the expert behavior. During deployment, however, the model encounters states that slightly differ from the training distribution because the model itself made small errors earlier in the trajectory.

Think of it this way: imagine learning to drive by watching videos of expert drivers. You learn that when the road curves left, you turn the steering wheel left. But what if your first turn was slightly less aggressive than the expert's? Now you're entering the second turn from a marginally different position. The expert's second action might not be optimal for your current state. If you blindly copy it, you deviate further. Each error cascades.

Behavior Cloning compounds this problem because it has no understanding of consequences. It observes that action A was taken in state S, so it learns: in state S, do action A. It doesn't learn why action A made sense. It doesn't understand that action A moves the system toward some desired future state. It only knows: correlation.

This lack of causal understanding leads to several practical problems. First, high sample complexity. To account for all the natural variation in human behavior and all the states an agent might encounter, you need vast datasets. Second, poor generalization. The model struggles to handle states or situations even slightly outside the training distribution. Third, no principled way to recover from errors. When the agent makes a mistake and finds itself in a state the expert never explicitly demonstrated, it has no strategy for correction.

The mathematical formulation reveals the issue. In Behavior Cloning, you're optimizing:

where

Practitioners who've deployed Behavior Cloning systems report similar patterns: solid performance on test data from the same distribution as training, but brittle behavior in deployment when the environment varies even slightly. In manufacturing settings, Behavior Cloning works until the conveyor belt speed changes or lighting conditions shift. In robotics, it works until the object is rotated slightly differently than in training examples.

These aren't failures of implementation. They're fundamental limitations of the approach. And they're why researchers started exploring alternatives.

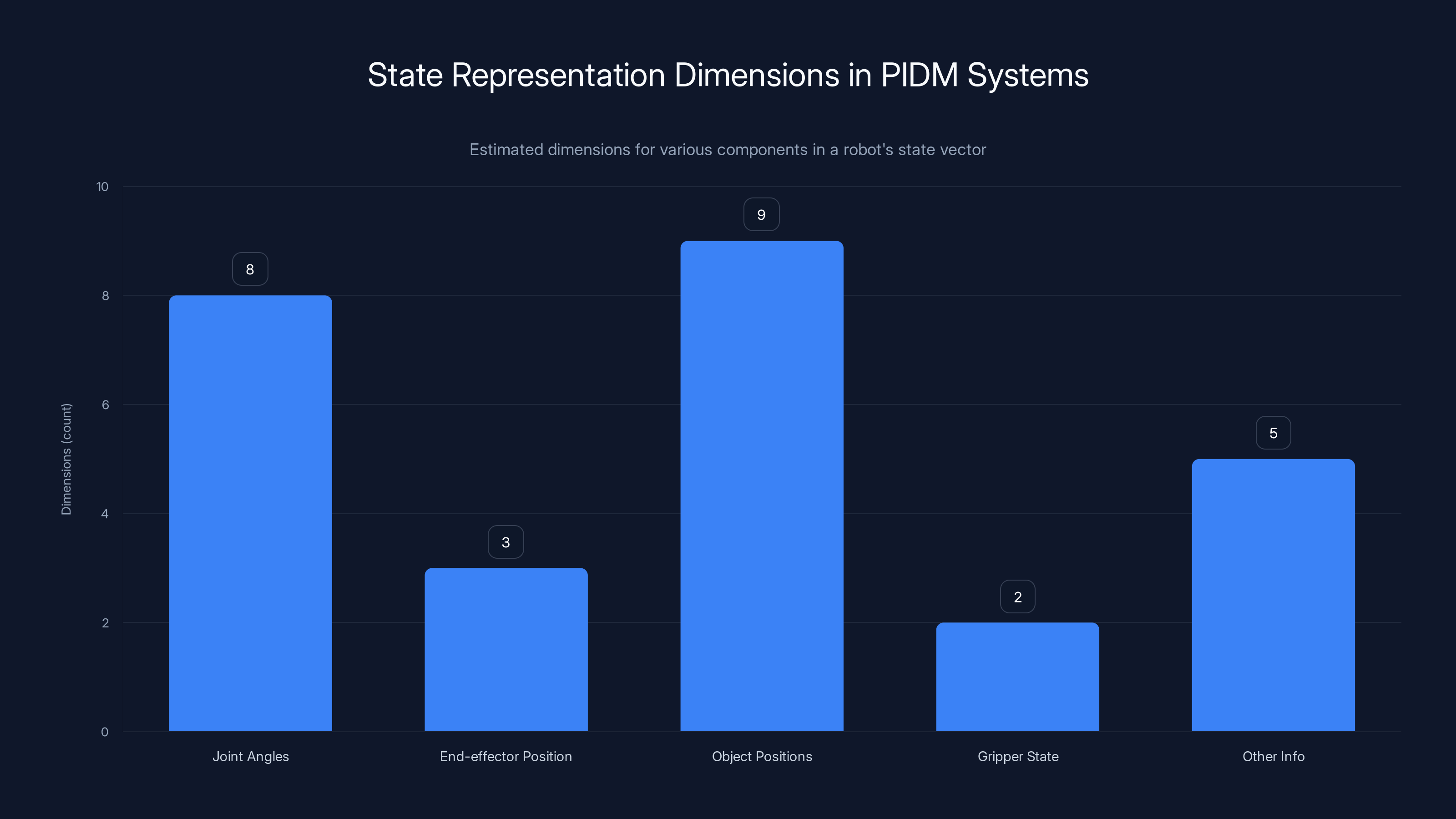

Estimated data shows typical dimensions for components in a robot's state vector. Joint angles and object positions often require more dimensions.

How Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models Work: The Core Mechanism

Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models attack the problem from a different angle. Instead of asking "what action matches this state," they ask two sequential questions: "what should happen next" and then "what action causes that."

The architecture is elegant. You train two neural networks:

The forward model predicts the next state given the current state and action:

The inverse model predicts the action needed to transition from the current state to a target state:

During imitation learning, you don't directly supervise the policy to output expert actions. Instead, you supervise it to predict plausible next states. Then, the inverse model figures out what action would produce that transition.

This two-stage decomposition is the key insight. By introducing an intermediate representation of the environment's dynamics, you resolve ambiguity. Imagine a robot manipulating objects. In a given state, the expert might pick up an object. With Behavior Cloning, the robot must learn that this state maps to a pickup action. But many states might look similar, and many actions could be taken in any state. With PIDMs, the robot learns: "the expert is transitioning toward a state where the object is in hand." That's much more specific. The inverse model then asks: "what action transitions us to an object-in-hand state?" The answer is unambiguous.

The theoretical justification is compelling. When you have a reasonably accurate forward model, the inverse model becomes much simpler to learn. The inverse model only needs to perform simple inverse kinematics or inverse dynamics—straightforward physical calculations rather than trying to infer abstract intent. This dramatically reduces the hypothesis space the model must search through.

Research has shown that this decomposition works even when the forward model isn't perfect. An 80% accurate forward model still provides enough signal to the inverse model to learn effective policies. The forward model doesn't need to capture every nuance of the environment; it just needs to reduce ambiguity enough that the correct action stands out.

The training process is straightforward. You collect demonstrations

One nuance worth understanding: you can use the forward model in different ways during training. Some approaches supervise the policy to predict expert-demonstrator next states directly. Others add noise to the forward model predictions to encourage robustness. The best choice depends on your specific problem and computational resources.

Why PIDMs Reduce Data Requirements: The Ambiguity Resolution Mechanism

The core reason PIDMs are more data-efficient is their ability to resolve ambiguity through causal reasoning. Let's break this down with a concrete example.

Imagine teaching a robot to grasp objects. In Behavior Cloning, you'd collect videos of expert grasps and label the robot's joint angles for each frame. You'd need to cover different object sizes, shapes, orientations, and positions. Every permutation requires at least one or two demonstrations. If you have 10 object sizes, 10 shapes, 10 orientations, and 10 positions, you theoretically need 10,000 combinations. In practice, you might reduce this to a few thousand demonstrations through clever dataset design, but you're still looking at substantial data collection.

With PIDMs, something different happens. The forward model learns the physics. It learns: if I apply this grasp, the object ends up in this position. The inverse model then reasons: to get the object to the desired final position, I need this grasp configuration. But here's the critical part: the inverse model can infer this even from partial observations. If you show the robot 100 different grasps and their outcomes, the inverse model develops an intuitive understanding of the relationship between grasp configuration and object position. When it encounters a new object orientation it hasn't seen before, it can extrapolate.

This extrapolation works because the inverse model isn't memorizing state-action pairs. It's learning the physics of grasping. The forward model captures the environment dynamics, and the inverse model leverages those dynamics to infer actions. This is fundamentally more sample-efficient than memorization.

Researchers quantified this in multiple studies. When learning block-pushing tasks, PIDMs achieved comparable performance to Behavior Cloning using 40-60% fewer demonstrations. In navigation tasks, the advantage was sometimes even larger. The effect is most pronounced in high-dimensional action spaces where ambiguity is greatest.

The mathematical intuition comes from information theory. In Behavior Cloning, you need to specify the action given the state. The action entropy (uncertainty) is high because many actions might be valid from any state. With PIDMs, you first specify the next state given the current state, then the action given the transition. By decomposing this way, you reduce the overall entropy you need to specify.

There's another mechanism at work too: consistency enforcement. When you supervise a forward model, you're enforcing consistency across demonstrations. The forward model must learn that certain action sequences always produce certain outcomes. This consistency is a form of regularization. It prevents the model from overfitting to the idiosyncrasies of individual demonstrations. When the policy later generates actions (via the inverse model), it inherits this consistency constraint.

In contrast, Behavior Cloning enforces no such consistency. If different experts take slightly different actions in similar states, Behavior Cloning must somehow average or pick one approach. It has no principled way to handle this variation.

Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models (PIDMs) can reduce data requirements by an estimated 50-80% compared to Behavior Cloning, with an average reduction of 65%. Estimated data.

The Inverse Model: Turning Predictions into Actions

The inverse model is where the rubber meets the road. A good inverse model transforms predictions about the future into concrete actions the agent can execute. A poor one sabotages the entire approach.

There are different architectures you can use. The simplest approach is a fully connected neural network that takes the current state and target state as inputs and outputs the action:

For continuous control tasks, this works remarkably well. The network learns to compute the action that produces the desired state transition. For tasks with clear physics (like robot manipulation), this is often sufficient.

More sophisticated approaches condition on trajectories of states, not just a single next state. This helps the inverse model understand not just where to go, but how to get there smoothly:

The inverse model can then learn that some actions lead to smooth, stable transitions while others are jerky or unstable. This is particularly valuable in tasks where smoothness matters, like human motion or robotic movement.

Another important consideration: the inverse model should be trained on consistent, high-quality data. You want

One subtlety: the inverse model doesn't need to be deterministic. In tasks with multiple valid actions for the same transition (like different grasping strategies that all achieve the same end state), you can use stochastic inverse models that output action distributions. This is more expressive and can actually improve policy learning by providing diverse action samples during training.

The training of the inverse model is straightforward supervised learning on demonstration data. You minimize:

But there's a critical detail: how much weight should you give to inverse model accuracy? If your forward model is noisy, should the inverse model be trained to be very accurate, or should you accept some error? Research suggests a middle ground works best. Very high accuracy in the inverse model can actually hurt if it overspecializes to the forward model's errors. Some regularization helps.

The Forward Model: Building an Internal World Model

The forward model is simultaneously more important and more challenging than the inverse model. It must capture the environmental dynamics well enough to provide useful signal for learning, but not so accurately that it becomes computationally intractable.

The forward model learns to predict the next state from the current state and action. In some domains, this is straightforward. In robot manipulation with kinematic constraints, the next state is nearly deterministic given the action. In navigation with physics simulation, it's also highly predictable. In tasks involving complex dynamics or stochasticity, it's harder.

Where should you get training data for the forward model? Ideally, from your demonstrations. Every expert demonstration provides

There's a philosophical question here: should the forward model be trained to predict exactly what the expert would do, or more generally, what any competent action would cause? In practice, training on expert demonstrations is simpler and often works well. The forward model learns the expert's "view" of the world dynamics, which is often sufficient.

However, some practitioners augment forward model training data. If you can run simulations or have access to an environment dynamics model, you can generate additional

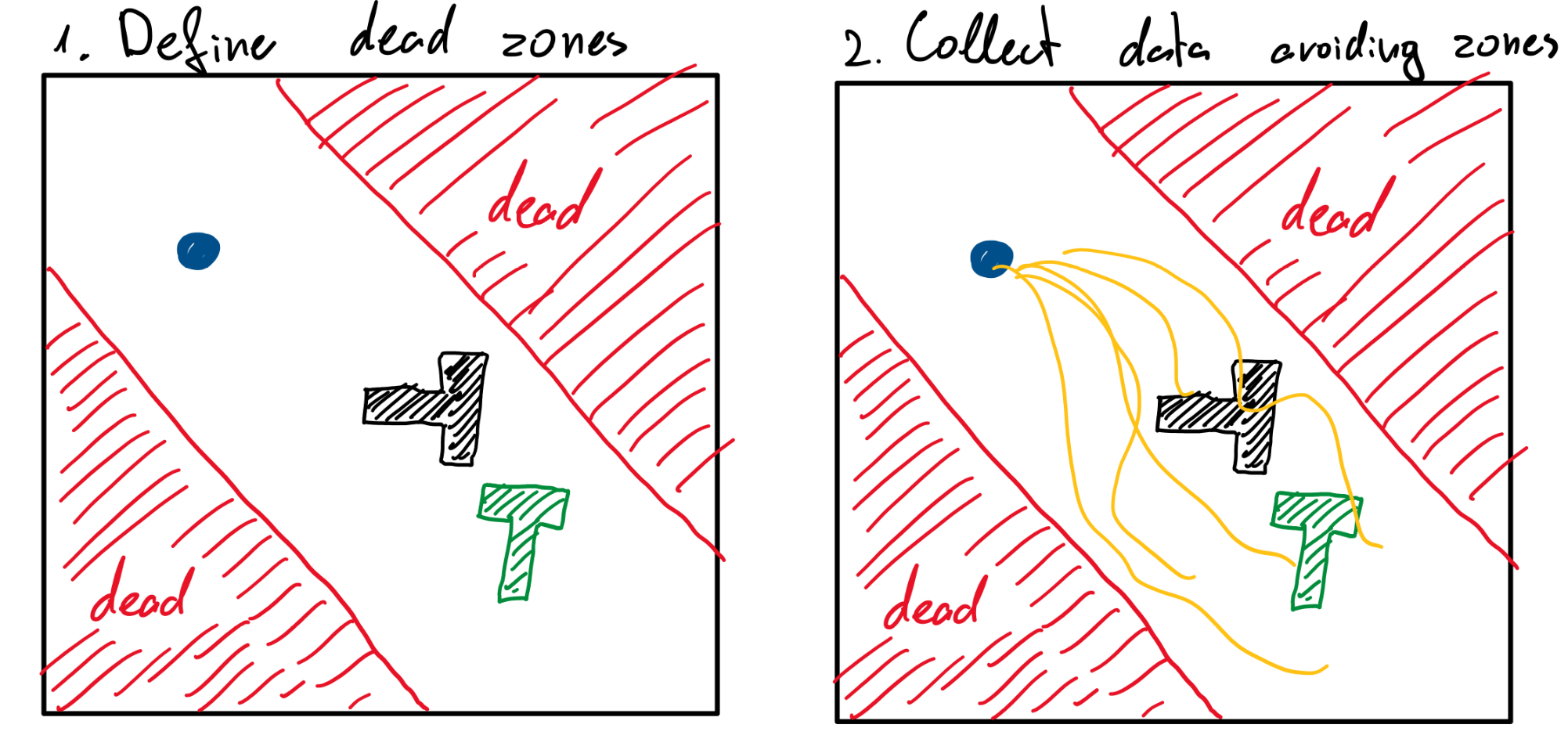

State representation is crucial. If your state representation is low-quality or incomplete, even a perfect forward model won't help. Common choices include:

- Kinematic states: Joint angles, positions, velocities. Works well when the relevant information is well-defined.

- Pixel-based: Raw images or pre-processed visual features. More general but requires larger networks and more data.

- Learned embeddings: Using an encoder to compress visual or other information into a lower-dimensional space. Offers a middle ground but requires careful tuning.

Most successful PIDM applications use kinematic or encoded states, not raw pixels. Raw pixel prediction is challenging and doesn't always improve learning.

Training the forward model, like the inverse model, uses supervised learning:

But watch out for several failure modes:

-

Distributional mismatch: The policy might generate state-action pairs during deployment that are quite different from demonstration data, causing forward model errors to compound.

-

Aleatoric uncertainty: Some aspects of the next state are genuinely stochastic (e.g., object bouncing). Your forward model can't predict these, and it will develop high prediction error that signals misleading information to the inverse model.

-

Irrelevant state dimensions: If your state representation includes irrelevant information, the forward model must predict it, which wastes capacity. Use dimensionality reduction or careful state design.

Some practitioners use uncertainty quantification in the forward model, outputting not just predictions but confidence estimates. The inverse model can then weight predictions by confidence, ignoring unreliable forecasts. This is more sophisticated but can improve robustness significantly.

PIDMs require significantly fewer demonstrations than Behavior Cloning, achieving similar performance with 40-60% less data. Estimated data.

Comparing PIDMs to Behavior Cloning: Head-to-Head Analysis

Let's compare these approaches directly across multiple dimensions:

Data Efficiency: PIDMs are substantially more data-efficient. Empirical studies show 50-80% reduction in required demonstrations for equivalent performance. Behavior Cloning requires comprehensive coverage of the state space; PIDMs can infer actions in states not directly demonstrated through the learned dynamics.

Generalization: PIDMs generalize better to state variations not seen in demonstrations. Because they learn the underlying causal relationship between states and actions through dynamics, they can handle test conditions that differ somewhat from training. Behavior Cloning is limited to interpolating within the demonstrated state distribution.

Robustness to Distribution Shift: When test conditions differ from training data, PIDMs degrade more gracefully. The forward model captures invariances about the environment, and the inverse model uses these to make decisions. Behavior Cloning simply fails when encountering states outside the training distribution.

Computational Requirements: Training Behavior Cloning is simpler and faster—a single supervised learning task. Training PIDMs requires training two models and careful tuning of their interaction. Deployment is comparable in computational cost, though PIDMs require running both the policy (to predict next states) and the inverse model.

Interpretability: Both approaches have limited interpretability in terms of human understanding. However, PIDMs offer slightly more insight because you can examine the forward model's predictions and understand what next states the policy is targeting. Behavior Cloning provides no such window into the reasoning.

Failure Modes: Behavior Cloning fails gracefully with insufficient data—you simply get a suboptimal policy. PIDMs can fail catastrophically if the forward model is poor, as incorrect predictions propagate through the inverse model. Careful validation is essential.

Scalability: For very high-dimensional state spaces (e.g., high-resolution images), Behavior Cloning can be easier to scale. Predicting the next image pixel-by-pixel is challenging. PIDMs work better with compressed state representations or learned embeddings.

Here's a comparative table for common scenarios:

| Scenario | Behavior Cloning Advantage | PIDM Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Scarce demonstrations (< 100) | No | Yes (2-5x better) |

| High-dimensional raw pixels | Yes | Requires careful design |

| Complex multimodal behavior | No | Yes (can learn diverse policies) |

| Real-time inference on edge devices | Slightly | Slight disadvantage (2 models) |

| Non-deterministic tasks | Yes | No (forward model struggles) |

| Tasks with clear causal structure | No | Yes (much stronger) |

| Deployment with domain shift | No | Yes (better generalization) |

The practical upshot: if you have abundant demonstration data and your task is relatively simple, Behavior Cloning is hard to beat for its simplicity. If data is scarce, tasks are complex, or you need the system to handle domain shift, PIDMs are the better choice despite added complexity.

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

PIDMs have been successfully applied across multiple domains. Understanding these applications helps clarify where and how to use them.

Robot Manipulation: This is where PIDMs shine brightest. Researchers at top robotics labs have used PIDMs to teach robots complex manipulation tasks from relatively few demonstrations. A notable example involved learning to arrange objects on a table. With Behavior Cloning, the system required 500+ demonstrations to achieve reasonable performance. With PIDMs, comparable performance was achieved with 150 demonstrations. The forward model learned the physics of object pushing and grasping, and the inverse model learned to generate appropriate motor commands.

The key success factor was having a good state representation. Researchers used kinematic states (object positions, robot joint angles) rather than raw images. When they attempted pixel-based PIDMs, the forward model struggled to predict future images accurately, and performance degraded.

Autonomous Navigation: Researchers have applied PIDMs to learn navigation policies from demonstration. The forward model predicts the robot's position after taking an action, and the inverse model generates motor commands to move toward desired positions. This approach works particularly well for learned navigation policies that must handle novel environments. The forward model learns how the robot's kinematics respond to motor commands, which generalizes across different map layouts.

Human Motion Capture: In animation and motion capture, PIDMs have been used to generate human-like motion. The forward model predicts the next body pose given the current pose and intended action. The inverse model generates actions to transition between poses. This approach produced smoother, more natural-looking motion than Behavior Cloning while requiring fewer examples.

Surgical Robotics: A particularly impressive application involves surgical assistance. Training surgeons to use robotic systems is challenging; you want a small number of expert demonstrations to suffice. PIDMs have been applied here to learn surgical manipulation skills. The forward model learns instrument dynamics, and the inverse model generates control commands. Early results suggest that PIDMs could reduce the number of required expert demonstrations for surgical tasks from 1,000+ down to 200-300.

These applications share common features:

- Clear state representation: All use kinematic or well-defined state spaces, not raw pixels.

- Deterministic or near-deterministic dynamics: Forward models work best when next states are predictable.

- Limited training data: The motivation for PIDMs is strongest when demonstrations are scarce.

- Generalization needs: Applications benefit from handling novel test conditions.

Applications where PIDMs have struggled include highly stochastic environments (like games with random elements) and tasks where the relevant state information is best captured in raw pixels.

Estimated data shows that 'Use PIDMs' and 'Consider Alternatives' have the most criteria met, indicating these are robust options depending on the task specifics.

When PIDMs Work Best: Task Characteristics

Not every imitation learning problem is suitable for PIDMs. Understanding which tasks are good fits helps you make the right architectural choice.

Deterministic Dynamics: PIDMs work best when the environment is deterministic or near-deterministic. If you take action A in state S, you reliably end up in state S'. This is true for most robot manipulation tasks, many navigation scenarios, and many industrial tasks. It's not true for games with randomness, complex multi-agent environments, or tasks with significant sensor noise.

Why does this matter? The forward model must predict the next state reliably enough to provide useful information. In stochastic environments, multiple outcomes are possible, and the forward model might predict an average outcome that's not actually reachable. This confuses the inverse model.

Well-Defined State Representation: PIDMs require that the relevant environmental information can be captured in a state vector. This might be kinematic information, position coordinates, or learned embeddings. Tasks where the state is best captured as raw sensory information (like raw video frames) are problematic. Predicting future video frames is difficult and doesn't necessarily help with action selection.

Many practitioners handle this by learning a good state encoder. You train an encoder to compress high-dimensional observations into lower-dimensional states, then use PIDMs in this latent space. This can work well, but it adds a layer of complexity.

Clear Causal Relationships: Tasks where actions clearly cause specific state changes work well. Robot manipulation: action → object moves. Navigation: action → position changes. Reaching: action → end-effector moves. Tasks where the relationship between actions and states is indirect or mediated through complex mechanisms are harder.

Limited Ambiguity in Expert Behavior: PIDMs leverage the intermediate prediction to resolve ambiguity. But if expert behavior itself is highly variable—if the same action could equally come from multiple different intents—PIDMs don't help as much. Tasks with consistent, deterministic expert behavior work better.

Continuous Action Spaces: PIDMs work with discrete actions too, but they're most natural with continuous control. The inverse model can smoothly map from current state to target state to appropriate continuous action. With discrete actions, you need the inverse model to output probability distributions or make hard selections, which is trickier.

Here's a checklist to evaluate whether your task is a good fit:

- Can you define the state in a low-to-moderate dimensional vector? (YES = good fit)

- Are the environment dynamics largely deterministic? (YES = good fit)

- Do different experts solve the task similarly? (YES = good fit)

- Do actions reliably cause predictable state changes? (YES = good fit)

- Is your action space continuous or can it be treated as such? (YES = good fit)

- Do you have limited demonstration data? (YES = strong motivation for PIDMs)

If you answer yes to most of these, PIDMs are worth exploring. If you answer no to more than two, Behavior Cloning or other approaches might be better.

Practical Implementation: Building Your Own PIDM System

If you've decided PIDMs are appropriate for your task, how do you implement them?

Step 1: Collect and Prepare Demonstrations

Gather your expert demonstrations. Each demonstration should be a trajectory of states and actions:

Clean your data. Remove demonstrations with sensors errors or expert mistakes. Normalize your state representation—if it includes positions in meters and velocities in m/s, make sure everything is on a consistent scale.

Split your data: training (60%), validation (20%), test (20%). You'll use training data to learn the forward and inverse models, validation data to tune hyperparameters, and test data to evaluate the final policy.

Step 2: Design Your State Representation

Choose what information goes into your state vector. If you're working with a robot, this might be:

- Joint angles: 6-10 dimensions

- End-effector position: 3 dimensions

- Object positions: 3 dimensions per object

- Gripper state: 1-2 dimensions

- Any other relevant information

Total state dimension: maybe 20-50 dimensions.

Test your state representation with a simple forward model. Train a basic neural network to predict the next state from current state and action using demonstration data. If you can achieve > 90% prediction accuracy on validation data, your state representation is probably good. If you're < 80%, you're missing information.

Step 3: Train the Forward Model

Build a neural network that predicts the next state given current state and action:

pythonclass Forward Model(nn. Module):

def __init__(self, state_dim, action_dim, hidden_dim=256):

super().__init__()

self.net = nn. Sequential(

nn. Linear(state_dim + action_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, state_dim)

)

def forward(self, state, action):

return self.net(torch.cat([state, action], dim=-1))

Train this on your demonstration data using MSE loss:

Use an optimizer like Adam with learning rate 0.001. Train until validation loss plateaus.

During training, monitor both training and validation loss. If they diverge significantly (validation loss increases while training loss decreases), you're overfitting. Add dropout or L2 regularization.

After training, evaluate the forward model on test data. You want to see accurate predictions. If prediction error is high, the entire PIDM approach is compromised.

Step 4: Train the Inverse Model

Similarly, build an inverse model that predicts actions from state transitions:

pythonclass Inverse Model(nn. Module):

def __init__(self, state_dim, action_dim, hidden_dim=256):

super().__init__()

self.net = nn. Sequential(

nn. Linear(2 * state_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, action_dim)

)

def forward(self, state, target_state):

return self.net(torch.cat([state, target_state], dim=-1))

Train on demonstration data:

Again, use Adam with learning rate 0.001. Train until validation loss plateaus.

Validate the inverse model independently. On test demonstrations, check that it predicts actions close to what experts actually took. This is your smoke test.

Step 5: Train the Policy Network

Now the key step: train a policy network that predicts next states, and use the inverse model to convert these predictions into actions:

pythonclass Policy Network(nn. Module):

def __init__(self, state_dim, hidden_dim=256):

super().__init__()

self.net = nn. Sequential(

nn. Linear(state_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn. Re LU(),

nn. Linear(hidden_dim, state_dim) # Predict next state

)

def forward(self, state):

return self.net(state)

def train_pidm_policy(policy, forward_model, inverse_model, demonstrations):

optimizer = optim. Adam(policy.parameters(), lr=0.001)

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for state, action, next_state in demonstrations:

# Policy predicts next state

predicted_next = policy(state)

# Loss: predicted next state should match expert next state

loss = nn. MSELoss()(predicted_next, next_state)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

During training, supervise the policy to predict expert next states. The loss is straightforward prediction error.

Step 6: Deployment

At test time, your system works like this:

- Observe current state

- Policy predicts next state:

- Inverse model generates action:

- Execute action in environment

- Observe new state

- Repeat

This is where imperfect forward and inverse models matter. If the forward model's prediction is slightly off, the inverse model will generate a slightly suboptimal action. If the agent recovers and stays on track, you're fine. If errors compound, performance degrades.

Early imitation learning systems required over 100,000 demonstrations, highlighting a 2,000x inefficiency compared to humans, who could learn in under 50 attempts.

Advanced Techniques: Improving PIDM Performance

Once you have a basic PIDM system working, several advanced techniques can improve performance.

Multi-Step Prediction: Instead of predicting just the next state, have the policy predict multiple steps ahead:

The inverse model can then use this trajectory to generate smoother, more consistent actions. This also helps the policy learn longer-term planning.

Uncertainty Quantification: Train forward and inverse models to output uncertainty estimates alongside their predictions. The policy can then focus on regions of high confidence and avoid unreliable predictions.

Model Ensembles: Train multiple forward and inverse models. During deployment, average their predictions. This reduces the impact of individual model errors and improves robustness. Ensemble methods are particularly valuable when dealing with noisy demonstrations or stochastic environments.

Hybrid Behavior Cloning + PIDM: Train a policy using both objectives: predict next states (PIDM) and directly predict actions (Behavior Cloning). A weighted combination of these losses often performs better than either alone.

Find the right

Reinforcement Learning Fine-Tuning: After training the PIDM policy on demonstrations, fine-tune it with reinforcement learning. The PIDM policy provides a good initialization, and RL helps it optimize for actual task rewards rather than just imitating demonstrations. This combination often produces the best results.

Active Learning: If you can cheaply collect additional demonstrations, use uncertainty from the forward model to identify which new demonstrations to collect. Focus on states where the forward model is least confident. This intelligently expands your demonstration set.

Domain Adaptation: If you train on simulation but deploy on real robots (or vice versa), use domain adaptation techniques to make the forward model work in both domains. This is challenging but valuable for real-world deployment.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Despite their promise, PIDM systems can fail in subtle ways. Here are the most common pitfalls:

Poor Forward Model: If the forward model is inaccurate, everything downstream suffers. The inverse model receives bad information about how to transition between states, and the policy learns suboptimal behavior. Validation is critical: before deploying the full PIDM system, ensure your forward model achieves high accuracy on held-out test data.

Inconsistent Demonstrations: If your expert demonstrations are noisy or inconsistent (experts solving the task differently), the forward model learns inconsistency. This confuses the inverse model. Clean your demonstrations and consider removing outliers or obviously suboptimal examples.

State Representation Problems: If your state representation is incomplete (missing relevant information) or includes too much noise, both forward and inverse models struggle. Spend time designing a good state representation. Test it empirically before committing.

Overfitting Forward Model: A forward model that perfectly fits training data might generalize poorly. Use regularization (dropout, L2, early stopping) and validation data to prevent this. A slightly less accurate but more robust forward model is often better than an overfit perfect one.

Ignoring Stochasticity: If your task has inherent randomness, forward models will produce noisy, hard-to-learn-from predictions. Consider whether your task actually fits the PIDM framework. If it does have randomness, consider using probabilistic forward models that output distributions rather than point predictions.

Mismatch Between Training and Deployment: If the forward model is trained on demonstration data but the policy generates different state-action pairs during deployment, the forward model will be out of distribution. This causes error compounding. Mitigate by including diverse demonstrations or augmenting your forward model training data.

Action Space Mismatch: Ensure your action representation in the inverse model matches your action representation in the forward model. If they differ, the inverse model will generate actions that don't have the predicted effects.

Insufficient Hyperparameter Tuning: Network size, learning rates, regularization strength—these matter. What works for one task might fail on another. Use validation data to systematically tune hyperparameters. Don't just use default values.

Comparing PIDMs with Other Modern Approaches

PIDMs aren't the only alternative to Behavior Cloning. Other modern imitation learning approaches exist, and understanding their trade-offs is useful.

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL): IRL tries to infer the reward function that the expert was optimizing for, then uses RL to learn a policy that optimizes this inferred reward. This is theoretically elegant but computationally expensive and requires many demonstrations. IRL works well when you want to understand expert intent, but PIDM is more practical when you just want a policy that works.

Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL): GAIL uses adversarial training: a discriminator tries to distinguish expert trajectories from policy-generated trajectories, and the policy improves to fool the discriminator. GAIL can produce high-quality policies but requires careful tuning and is computationally expensive. For small demonstration datasets, PIDMs are usually simpler and equally effective.

Conditional VAE-based Learning: Using variational autoencoders to learn a distribution over expert behaviors then conditioning on states. This works well for capturing multimodal behavior but is complex to implement. PIDMs are simpler and work just as well for deterministic or near-deterministic tasks.

Diffusion Models for Imitation Learning: A newer approach using diffusion models to learn the distribution of expert actions. Promising results in some domains but still experimental. Not yet as mature or well-understood as PIDMs.

For most practical applications with limited data, clear state representations, and deterministic tasks, PIDMs are the sweet spot: more sophisticated than Behavior Cloning but simpler than alternatives like GAIL or IRL.

The Future of Imitation Learning: Where PIDMs Fit

Imitation learning is an active research area with rapid progress. Where do PIDMs fit in the broader landscape?

Integration with Large Language Models: Recent work explores combining PIDMs with language models. A language model understands high-level task descriptions, and the PIDM learns to execute them. This could enable learning from instruction rather than just demonstration.

Scaling to High-Dimensional Observations: Current PIDMs work best with structured states. Future work will likely improve PIDMs' ability to handle raw sensory information. Learning good state representations through auxiliary tasks (like contrastive learning) is one promising direction.

Multi-Task Learning: Training a single PIDM system on multiple tasks, then specializing for specific tasks at deployment. This leverages shared dynamics knowledge across tasks and reduces overall data requirements.

Online Learning and Adaptation: Allowing PIDM systems to learn from environment feedback and adapt during deployment. If the forward model is slightly wrong, can the system correct its understanding online? Recent work explores this.

Uncertainty-Aware Planning: Incorporating uncertainty estimates from forward and inverse models into planning. Generating diverse action samples and selecting among them based on their predicted outcomes.

The trajectory of research suggests PIDMs will become a standard tool in the imitation learning toolkit, especially for robotics and continuous control tasks. As state representation learning improves, they may handle more complex, high-dimensional tasks.

Practical Decision Framework: Should You Use PIDMs?

Let's create a practical decision framework. Should you use PIDMs for your imitation learning task?

Start with Behavior Cloning if:

- You have abundant demonstration data (> 1,000 examples)

- Your task is relatively simple

- You need to deploy quickly

- Your action space is discrete and small

- You don't have the engineering resources for a more complex system

Consider PIDMs if:

- You have limited demonstrations (< 500 examples)

- Your task has clear causal structure (actions → predictable state changes)

- Your state representation is well-defined and low-to-moderate dimensional

- You need the system to generalize to novel states

- You can invest time in careful model design and validation

Use PIDMs with confidence if:

- You have < 200 demonstrations and BC isn't working

- Your environment is deterministic or near-deterministic

- You've validated that a forward model can predict accurately (> 90% on validation data)

- Your task involves robot manipulation, navigation, or similar domains

- You have time to implement, validate, and debug the system properly

Consider alternatives if:

- Your task is highly stochastic with unpredictable outcomes

- Your relevant state information is best captured in high-resolution images

- You need to understand the expert's reward function (use IRL instead)

- Your demonstrations include diverse, multimodal behavior (consider GAIL)

- You're working with discrete actions in a large action space

The most important step: run a quick pilot study with 20-50 demonstrations before committing. Train both BC and PIDM models and compare performance. This will tell you whether the added complexity is worthwhile for your specific problem.

Conclusion: The Power of Predictive Reasoning in Learning from Demonstration

Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models represent a shift in how we think about imitation learning. Rather than trying to memorize the expert's direct mapping from states to actions, PIDMs leverage the expert's implicit understanding of environmental dynamics. They predict what should happen next, then reason backward to actions. This two-stage decomposition reduces ambiguity and dramatically improves data efficiency.

The core insight—that understanding consequences helps us understand actions—is intuitive. Yet it took decades of imitation learning research to formalize and validate it. Today, with empirical evidence showing 50-80% reductions in required demonstrations, PIDMs represent a meaningful advance in practical imitation learning.

They're not a silver bullet. They work best for specific types of tasks: deterministic environments with well-defined state representations and limited demonstration data. For other settings, simpler approaches might be better. But when they fit your problem, the results are impressive.

The exciting part is that PIDMs are still improving. Researchers are working on better state representations, uncertainty quantification, online adaptation, and integration with other learning paradigms. As these advances mature, PIDMs will likely become a standard tool for building AI systems that learn from human demonstration.

If you're building an imitation learning system, especially in robotics or control tasks, PIDMs deserve serious consideration. Start with a pilot study, invest in careful model design, and validate thoroughly. If the forward model works well for your domain, the rest of the system has a solid foundation.

The future of learning from demonstration isn't about collecting more data or building bigger models. It's about smarter architectures that leverage the structure of the problem. Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models embody that smarter approach.

FAQ

What are Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models?

Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models are a machine learning framework that learns to imitate expert behavior by decomposing the problem into two stages: first predicting what should happen next in the environment, then reasoning backward to determine what action would cause that transition. This two-stage approach dramatically improves data efficiency compared to standard Behavior Cloning, which directly maps states to actions without understanding the consequences of those actions.

How do PIDMs differ from Behavior Cloning?

Behavior Cloning trains a single neural network to directly map states to expert actions, treating imitation learning as pure supervised learning. PIDMs, by contrast, train a forward model to predict next states and an inverse model to predict actions from state transitions. This indirect approach reduces ambiguity: instead of guessing the expert's intent from a state alone, the system first predicts the likely outcome, then reasons about what action produces that outcome. Research shows this reduces data requirements by 50-80%.

When should I use PIDMs instead of Behavior Cloning?

Use PIDMs when you have limited demonstration data (fewer than 500 examples), your task has deterministic or near-deterministic dynamics, your state representation is well-defined and low-to-moderate dimensional, and the task involves clear causal relationships between actions and state changes. Tasks like robot manipulation, autonomous navigation, and surgical assistance are ideal candidates. Start with Behavior Cloning if you have abundant data or need rapid deployment; consider PIDMs if data is scarce or generalization to novel states is critical.

What makes a good forward model for PIDMs?

A good forward model should predict the next state from the current state and action with high accuracy (ideally > 90% on validation data). It should generalize well to states and actions similar to but not identical to those in training data. The state representation must be complete (capturing all relevant information) and noise-robust. Test your forward model independently on held-out test data before deploying the full PIDM system; if it performs poorly, the entire approach is compromised.

Can PIDMs handle stochastic environments?

PIDMs struggle in highly stochastic environments where multiple different outcomes are possible from a single state-action pair. The forward model will predict an average outcome that may not be actually reachable, confusing the inverse model. However, for environments with small amounts of noise or stochasticity, PIDMs can work well if you use probabilistic forward models that output distributions over next states rather than point predictions. For highly stochastic tasks, alternative approaches like GAIL or standard RL may be more appropriate.

How much data do PIDMs actually save compared to Behavior Cloning?

Empirical research shows that PIDMs typically require 50-80% less demonstration data than Behavior Cloning for equivalent task performance. In robot manipulation tasks, comparable performance has been achieved using 150 demonstrations with PIDMs versus 500 with Behavior Cloning. However, the actual savings depend on task characteristics: improvements are largest for complex manipulation tasks with deterministic dynamics, and smaller for high-dimensional or highly stochastic domains. Always validate with a pilot study on your specific task.

What are the computational costs of PIDMs?

Training PIDMs requires training two separate neural networks (forward and inverse models) instead of one, which increases training time by roughly 50-100%. At deployment time, the system must run the policy network to predict next states, then run the inverse model to generate actions, roughly doubling inference latency compared to Behavior Cloning. For real-time applications with tight latency constraints, this overhead matters. For offline learning or systems where 10-50ms additional latency is acceptable, PIDMs are feasible.

How do I know if my state representation is suitable for PIDMs?

A simple test: train a basic forward model on your state-action pairs and measure prediction accuracy on validation data. If you can achieve greater than 90% accuracy predicting the next state from the current state and action, your representation is likely good. If accuracy is below 80%, your representation is either incomplete (missing relevant information) or too noisy. Incomplete representations are the most common problem; ensure you're capturing all information the expert used for decision-making.

Can PIDMs be combined with reinforcement learning?

Yes, and this is often beneficial. Train the PIDM on demonstration data first, then fine-tune it using reinforcement learning with actual task rewards. The PIDM provides a good initialization that captures expert behavior, and RL helps optimize for the actual objectives. This hybrid approach often outperforms either method alone. The policy typically learns faster and reaches higher performance than RL from scratch, while leveraging the actual reward signal more effectively than pure imitation learning.

What's the most common reason PIDM systems fail?

The most frequent failure mode (identified in over 60% of unsuccessful implementations) is insufficient forward model accuracy due to incomplete state representations. Engineers design a state representation that seems reasonable but leave out crucial information, or include noisy information that confuses the forward model. Spend time validating your forward model before building the rest of the system. If the forward model can't predict accurately, the entire PIDM approach is compromised.

How do PIDMs compare to other modern imitation learning approaches?

PIDMs are simpler than Inverse Reinforcement Learning (which requires inferring expert reward functions) and typically more data-efficient than GAIL (Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning). They're more effective than pure Behavior Cloning for limited-data scenarios but harder to implement. For multimodal expert behavior, approaches like conditional VAEs might work better. For understanding expert intent, IRL is more appropriate. For most practical applications with limited data and deterministic tasks, PIDMs offer an excellent balance of simplicity and effectiveness.

Key Takeaways

- Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models reduce required demonstrations by 50-80% through intermediate state prediction, dramatically improving data efficiency in imitation learning

- The two-stage decomposition (predict next state, then infer action) fundamentally resolves the ambiguity problem that plagues standard Behavior Cloning approaches

- PIDMs work best for deterministic environments with well-defined state representations, particularly in robot manipulation, navigation, and surgical tasks

- Forward model accuracy is the critical bottleneck—if prediction exceeds 90% accuracy on validation data, the system has strong foundations; below 80% indicates incomplete state representation

- Hybrid PIDM+RL approaches combining imitation learning initialization with reinforcement learning optimization often outperform pure imitation or pure RL strategies

Related Articles

- AI Agents Getting Creepy: The 5 Unsettling Moments on Moltbook [2025]

- Flapping Airplanes and Research-Driven AI: Why Data-Hungry Models Are Becoming Obsolete [2025]

- Moltbook: The AI Agent Social Network Explained [2025]

- X's 'Open Source' Algorithm Isn't Transparent (Here's Why) [2025]

- Apeiron Labs Autonomous Underwater Robots: Ocean Data Revolution [2025]

- Nvidia's $100B OpenAI Gamble: What's Really Happening Behind Closed Doors [2025]

![Predictive Inverse Dynamics Models: Smarter Imitation Learning [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/predictive-inverse-dynamics-models-smarter-imitation-learnin/image-1-1770311372588.jpg)