Light-Controlled Magnetism at Room Temperature: The Breakthrough [2025]

Introduction: When Light Bends Magnetism

Imagine storing data on a hard drive that could rewrite information using nothing but a laser pulse lasting one billionth of a second. Sound like science fiction? It's not anymore.

For decades, magnetic storage has been the backbone of computing. From the spinning platters in your laptop's hard drive to the magnetic tape in enterprise data centers, we've relied on magnetism to hold onto our digital lives. But here's the problem: controlling magnetism has traditionally required either extreme cold, massive electrical currents, or specialized equipment that costs a fortune to build and maintain.

Then came the breakthrough that changes everything.

In 2024, researchers from Germany, Switzerland, and Italy published findings in Nature Communications that demonstrated something previously thought impractical: they controlled magnetic behavior in ultrathin materials using ordinary visible light at room temperature. No cryogenic cooling. No specialized mid-infrared lasers. Just regular light pulses doing the work.

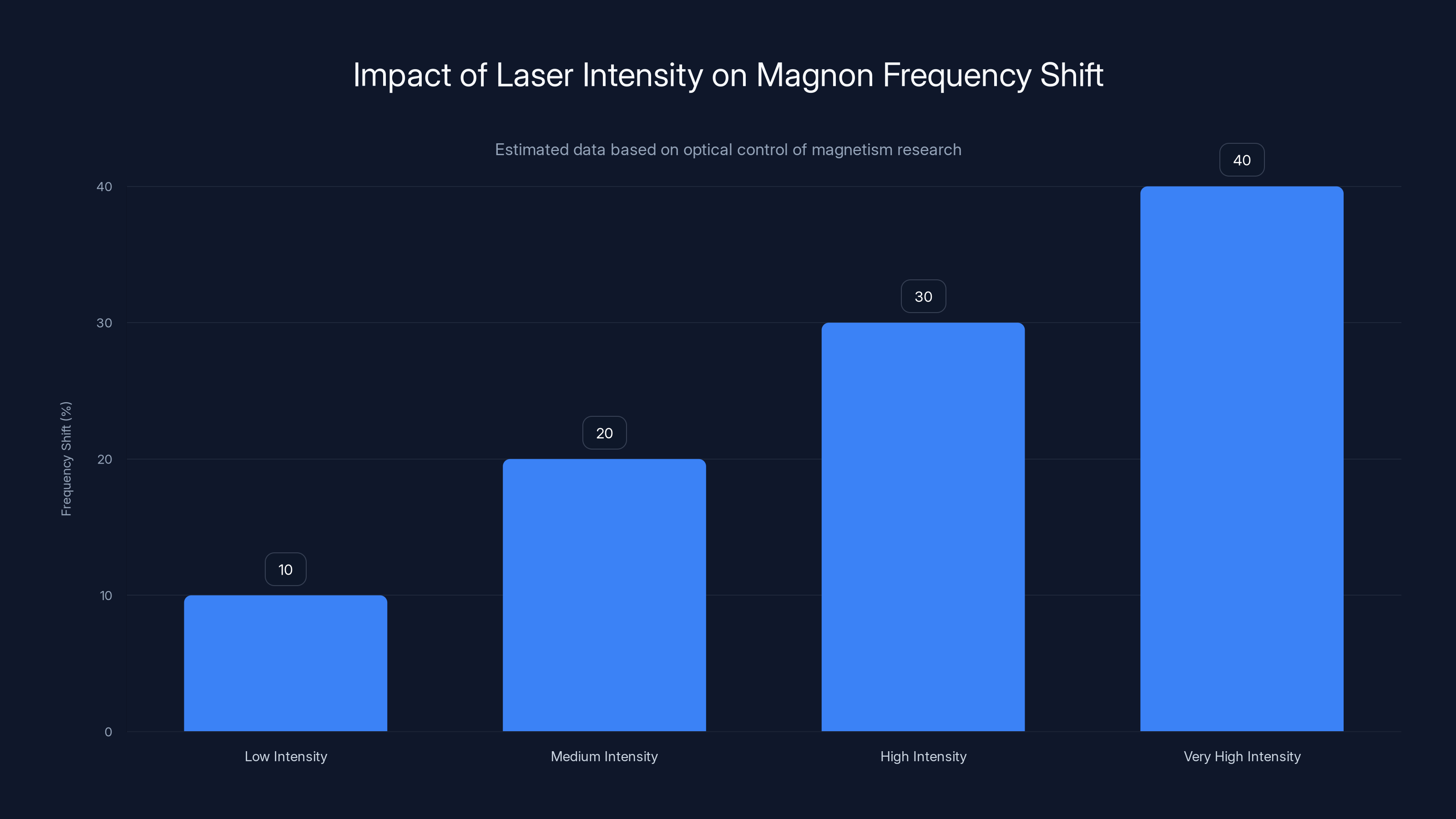

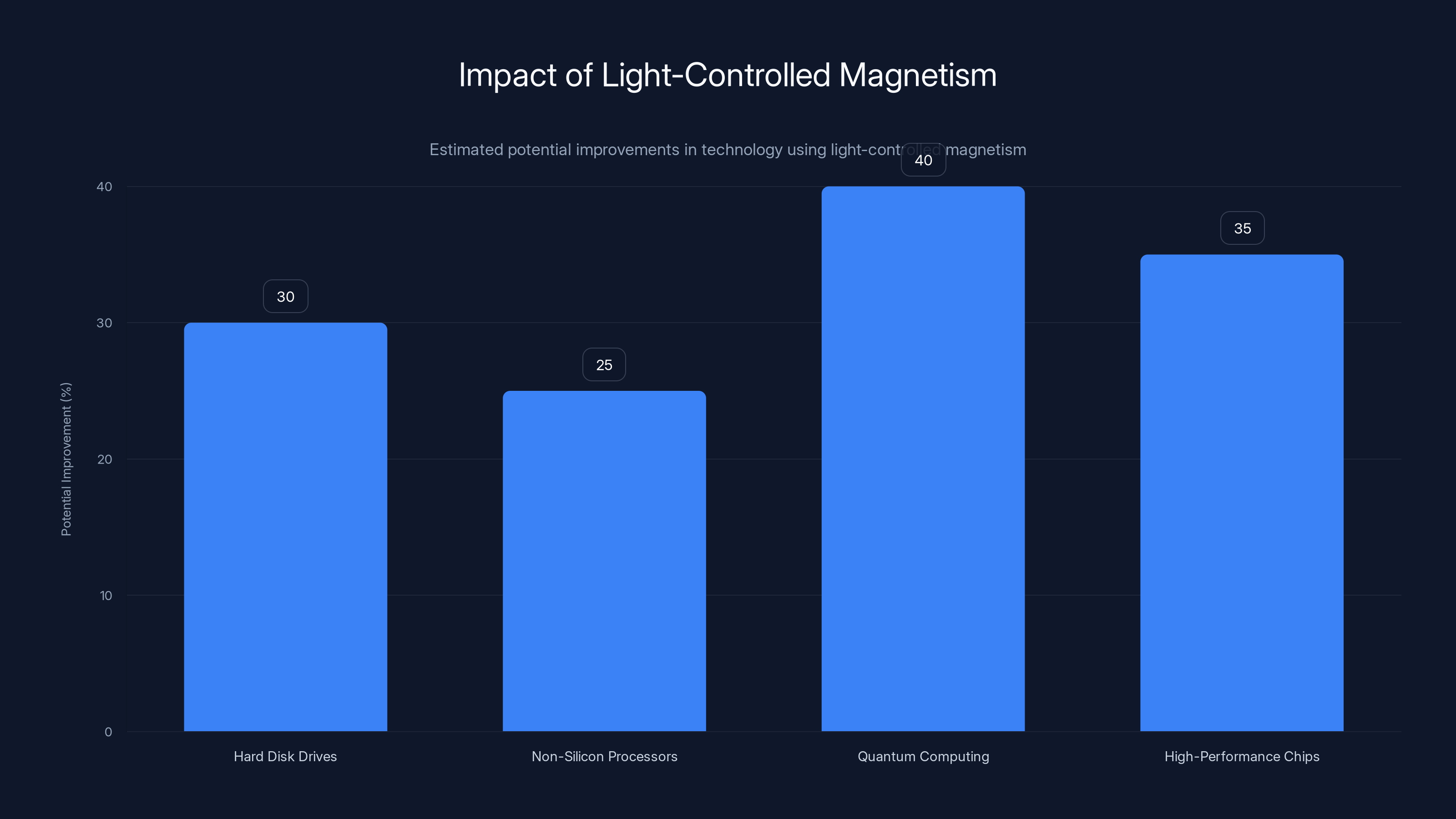

The results? Magnetic properties shifted by up to 40% using femtosecond laser pulses—flashes lasting less than a trillionth of a second. The material they used was only 20 nanometers thick, thinner than a human hair is wide. And it worked at room temperature, under modest magnetic fields, in conditions that could actually translate to real devices.

This isn't just another incremental lab result that disappears into academic journals. This opens doors to faster hard disk drives, speedier non-silicon processors, and magnetic components that respond to light instead of heat. For quantum computing, data storage, and high-performance chips, this fundamentally changes what's possible.

But here's what makes this moment interesting: the science behind it involves physics that's been studied for years, yet nobody had quite put the pieces together in this specific way. The team didn't use exotic materials or impossible conditions. They took known physics and applied it creatively to a problem that seemed stuck.

In this deep dive, we'll explore exactly what they discovered, how it works, why it matters, and where this technology is heading. We'll break down the physics without requiring a Ph D, look at real-world applications, and consider what happens when scientists realize their limitations are actually just assumptions they've been making too long.

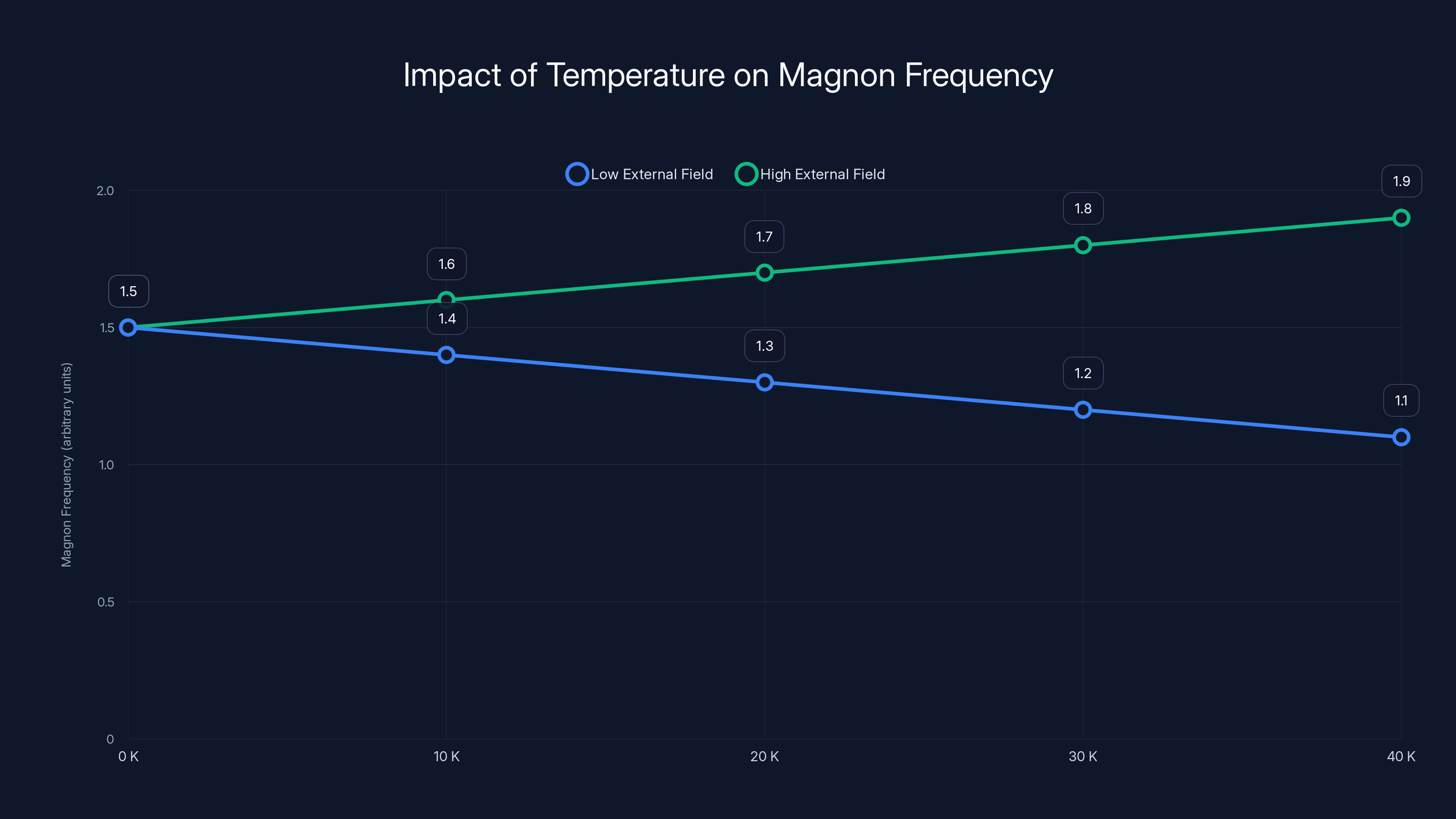

The chart illustrates the estimated impact of varying laser intensities on the frequency shift of magnons, with shifts up to 40% at very high intensities. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- Visible light pulses now control magnetism in nanometer-thick materials at room temperature, not requiring extreme conditions or specialized lasers

- Magnetic frequency shifts up to 40% achieved through optical heating that temporarily alters the balance between magnetic anisotropy and external fields

- Femtosecond pump-probe techniques monitor magnon behavior in real time, revealing how light-induced heating tunes coherent spin oscillations

- 20-nanometer thin films of bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet demonstrate practical scalability for integration into storage devices and processors

- Applications span HDDs, quantum computing, AI chip cooling, and next-generation non-silicon processors with potential energy efficiency gains over traditional electrical control methods

The Traditional Problem: Why Magnetism Has Been Stuck

Magnetism makes the modern world work. Every hard drive spinning in a data center, every SSD storing cloud backups, every magnetic stripe on a credit card—they all rely on one fundamental property: aligned atomic spins that create measurable magnetic fields.

But controlling those spins has always been a compromise.

Traditionally, there are two main ways to adjust magnetic behavior. The first is electrical: you push current through a wire, create a magnetic field, and align spins that way. It works, but it's power-hungry. Imagine needing to run current through every tiny magnet every time you want to change its state. On a modern processor with billions of transistors, that adds up fast. Heat generation becomes the limiting factor.

The second method is thermal. You heat the material above its Curie temperature—the point where magnetism breaks down—and then cool it back down in a new magnetic state. This is how old magnetic storage worked, and why it's slow. Heating and cooling take time, consume energy, and limit how fast you can write data.

For quantum computers and emerging technologies, these limitations become showstoppers. Quantum systems need magnetic control that's both fast and precise, without introducing thermal noise that ruins quantum states. Classical approaches can't deliver both.

Then there's the materials problem. Many promising magnetic materials only work at extremely low temperatures. Yttrium iron garnet, a material scientists have studied for decades, exhibits excellent magnetic properties. But in thin film form—the shape you'd actually use in devices—it was thought to require either extreme cold or impractical laser systems to control optically.

This wasn't a fundamental physics limitation. It was an engineering assumption. Nobody had figured out the right approach.

The real breakthrough moment came when researchers realized they didn't need to use specialized mid-infrared lasers tuned to specific magnetic resonances. They could use regular visible light, let it heat the material slightly, and exploit the natural physics that emerges from that heating. Simple. Elegant. The kind of insight that makes you wonder why nobody thought of it sooner.

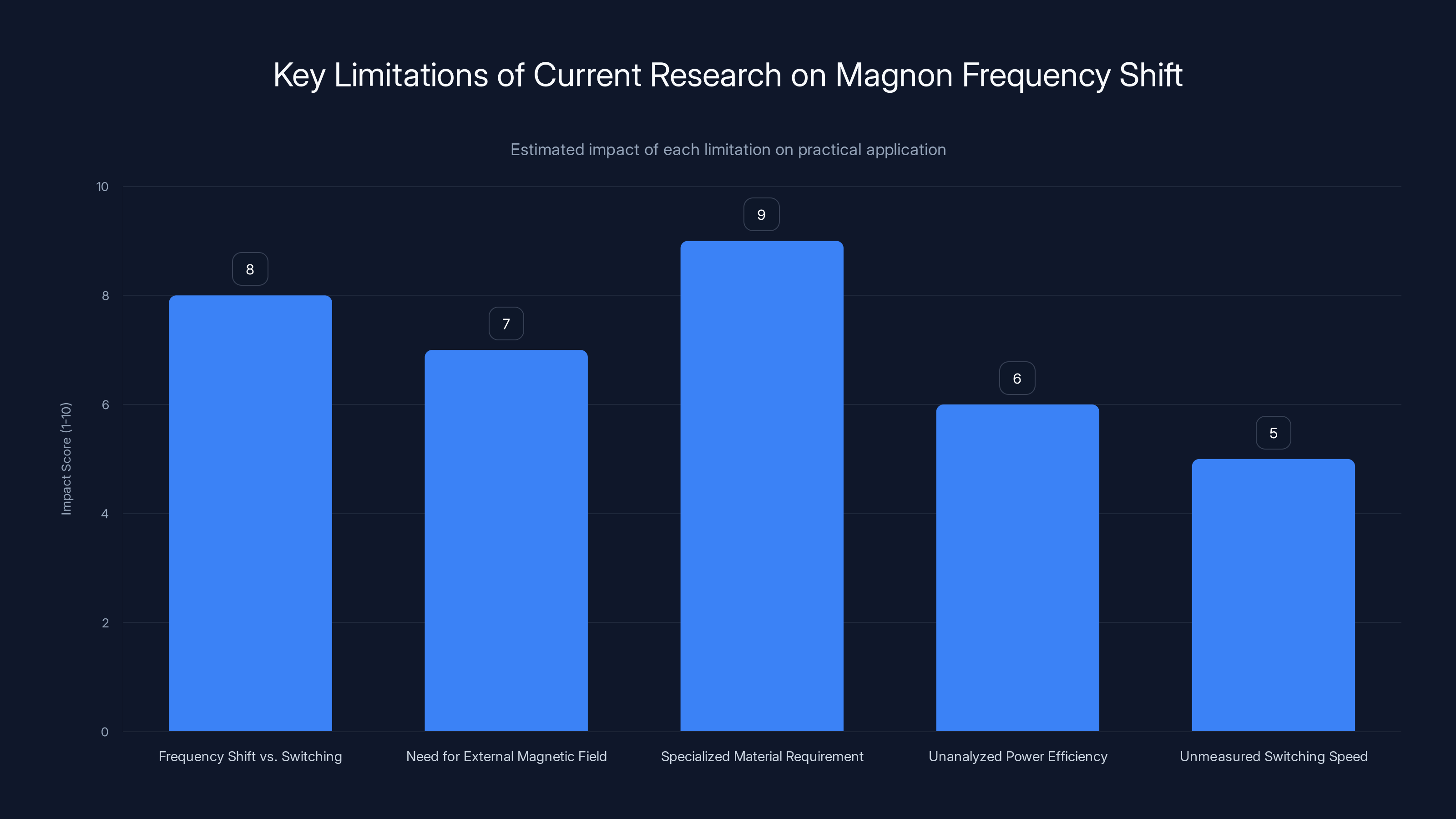

The chart estimates the impact of each limitation on the practical application of the research. The need for specialized materials and the lack of switching capability are the most significant hurdles. Estimated data.

How the Experiment Actually Worked: The Setup

Let's get into the specifics, because the details matter. This wasn't some rough proof-of-concept. The experimental design was precise, controlled, and reproducible.

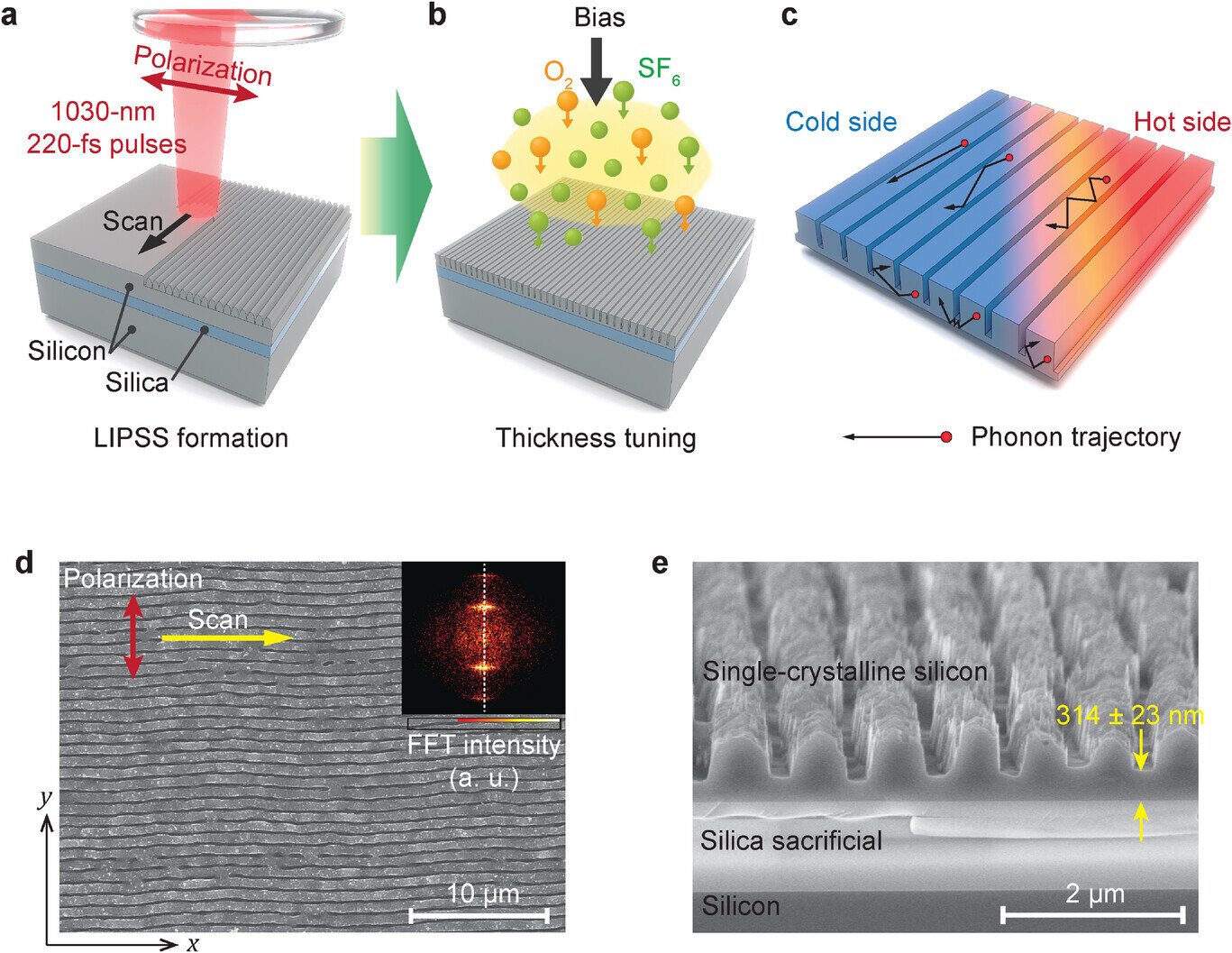

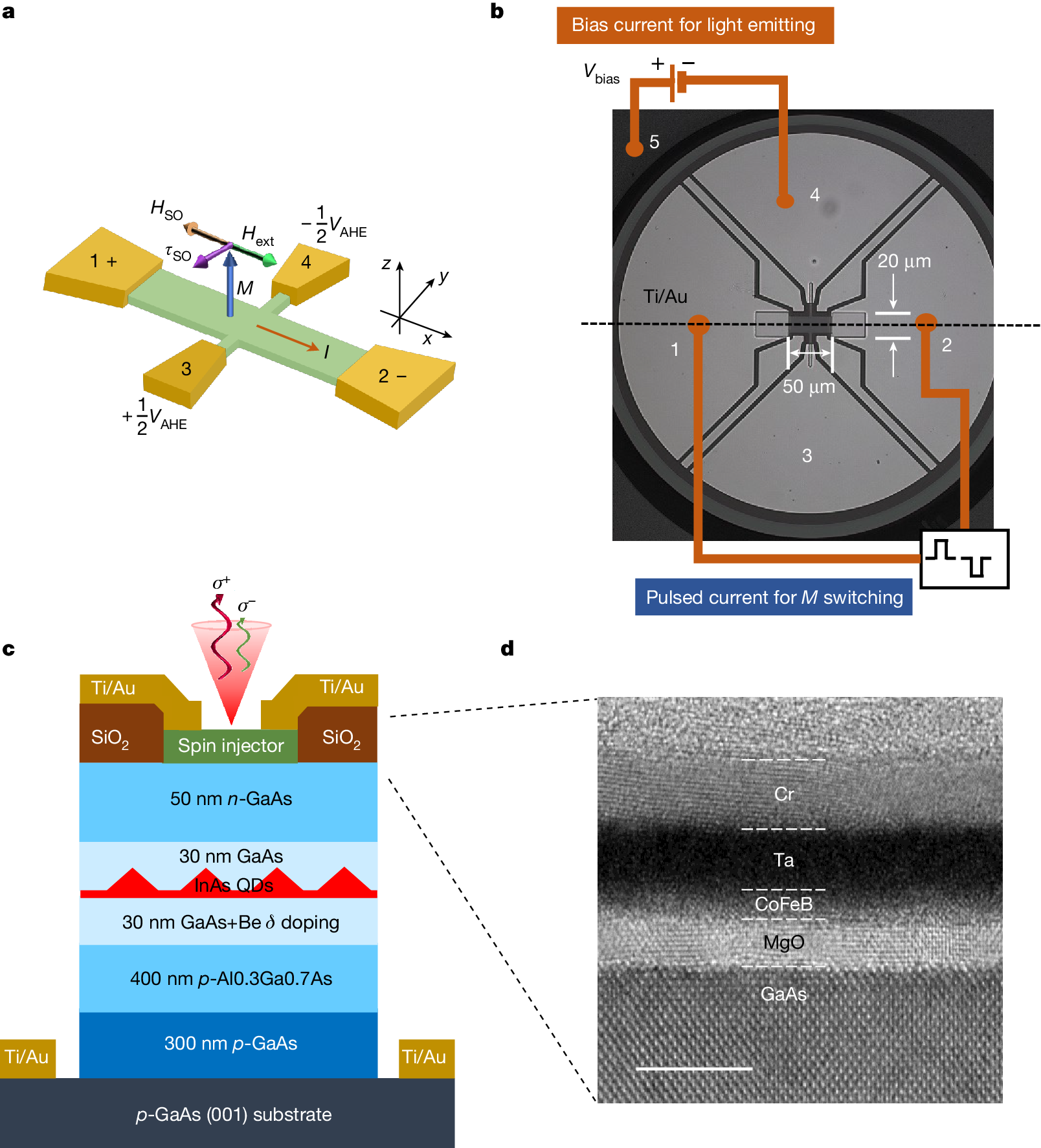

The researchers started with a substrate—basically a platform—made of gallium gadolinium garnet. On top of that, they grew an ultrathin film of bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet, often called YIG. This material is a ferrimagnetic compound, meaning it has magnetic properties similar to ferromagnets but with a more complex internal structure.

The thickness? Just 20 nanometers. To give you perspective, the best resolution of an optical microscope is around 200 nanometers. This film was about one-tenth that thickness. You couldn't see it with conventional microscopes, yet the researchers could control its magnetic properties with light.

Here's where the substrate matters. The gadolinium gadolinium garnet underneath is slightly different in crystal structure than the yttrium iron garnet film on top. This mismatch—called lattice strain—forces the magnetic moments in the thin film to point perpendicular to the film's surface. This out-of-plane orientation is crucial. It creates a well-defined, stable magnetic state that the researchers can then measure and modulate.

They applied an external magnetic field below 200 millitesla to set the initial magnetic configuration. For context, the Earth's magnetic field is about 50 microtesla. This lab field was 4,000 times stronger, but still modest by laboratory standards. Not extreme. Reproducible in any decent physics lab.

Then came the light. They used femtosecond laser pulses—pulses lasting 10 to 100 femtoseconds, which is about 10 to 100 quadrillionths of a second. These pulses were visible light, specifically green and near-infrared wavelengths. Nothing exotic. Equipment like this exists in thousands of research institutions worldwide.

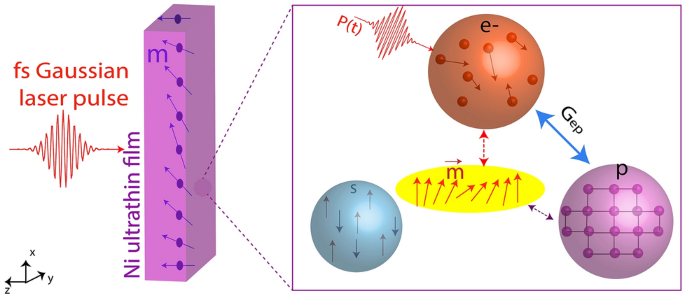

When these pulses hit the material, something interesting happened. The photon energy exceeded the material's bandgap energy, which means the light got absorbed by exciting electrons rather than creating resonant magnetic excitations. The material warmed up slightly—though we're talking picoseconds of time, not sustained heating.

The team used what's called a pump-probe technique to measure what happened. A pump pulse excited the material. Then, at carefully controlled time intervals, a probe pulse checked the state of the system. By adjusting the delay between pump and probe, they could create a frame-by-frame picture of how the magnons responded over femtoseconds and picoseconds.

The results showed coherent magnon oscillations—waves of magnetic energy rippling through the material. The frequency of these oscillations changed in response to the pump laser pulse. That frequency shift could go either direction: up or down, depending on the magnetic field strength and laser intensity.

The Physics: What's Actually Happening Inside

Here's where most explanations get fuzzy. Everyone talks about the results, but they skip the mechanism. Let's fix that.

When the visible light pulse hits the yttrium iron garnet film, electrons in the material absorb photons. Since the photon energy exceeds the bandgap, electrons jump to higher energy states. This excitation isn't random—it redistributes electron energy across the material in microseconds.

But here's the key: this excitation is thermal in nature. The energy becomes heat, spreading through electron-phonon interactions. The lattice—the crystal structure itself—warms up, but only slightly, and only briefly. We're talking about temperature increases of tens of kelvin, not hundreds, and only for picoseconds.

This slight warming matters because magnetism depends critically on anisotropy energy. Anisotropy is the fancy physics term for "magnetism prefers to point in certain directions." In this yttrium iron garnet film, the lattice strain and crystal structure create strong out-of-plane anisotropy.

Temperature changes the strength of that anisotropy. As the material warms, anisotropy weakens slightly. Meanwhile, the external magnetic field remains constant. The interplay between these two competing forces—anisotropy pointing perpendicular to the film and the external field pulling at an angle—determines the magnon frequency.

When anisotropy weakens (warm state), the external field has more influence, which can either increase or decrease magnon frequency depending on the field direction and magnitude. The researchers observed both: at lower fields, they saw frequency decreases; at higher fields, frequency increases. The behavior depended on the balance between these forces.

Mathematically, the magnon frequency for this system follows:

Where:

- is the magnetic anisotropy field

- is the exchange field (internal magnetic interactions)

- is the external applied field

When the laser pulse increases temperature, it effectively reduces

The effect was non-trivial. Magnon frequency shifted by up to 40% under moderate laser fluence. That's huge. It means you could use light pulses to significantly change how fast magnetic information propagates through a material.

What's remarkable is that this isn't based on some exotic quantum effect or resonance condition. It's straightforward thermodynamics and electromagnetism: light heats material, heating changes anisotropy, anisotropy change alters magnon dynamics. Understood for years. Applied in a new way.

Simulations confirmed this mechanism. The researchers modeled the material assuming only thermal heating from the laser, without invoking any resonant magnon excitation. The simulations matched the experiments. That's the signature of good science: when your explanation matches reality without needing extra assumptions.

Why Room Temperature Matters: The Practical Revolution

Stop and think about why room temperature seems like such a small detail to emphasize. In materials science, it's everything.

For the past two decades, most optical control of magnetism demonstrations required cryogenic cooling. We're talking liquid nitrogen (77 Kelvin), liquid helium (4 Kelvin), or even millikelvin temperatures. That means the experimental setup costs hundreds of thousands of dollars. Maintenance is specialized. Scaling to any real device becomes impractical.

Why? Because at room temperature, thermal fluctuations destroy the magnetic states that scientists were trying to control. At ultra-cold temperatures, those fluctuations freeze out. The magnetic system becomes stable, measurable, controllable.

But this discovery works at 300 Kelvin—room temperature. 298 Kelvin if you're being pedantic. The temperature at which you'd sit in a lab without special equipment.

This changes everything about what's possible. You don't need cryogenic infrastructure. You don't need to cool devices before they work. You don't need specialized facilities. Any well-equipped physics lab, any semiconductor manufacturer with laser equipment, could reproduce this work.

Consider the energy implications. Cooling systems for experimental apparatus consume serious power. Liquid helium costs thousands of dollars per liter. In quantum computing facilities, cryogenic systems are often the limiting factor—they're expensive, they break down, they require expertise to maintain. If you could do some operations at room temperature instead, suddenly the economics improve dramatically.

For practical devices—hard drives, memory, processors—room temperature operation is non-negotiable. You can't ship a product that requires it to be refrigerated. You can't build data centers that keep everything below freezing. The thermal footprint would destroy any energy efficiency gains.

This experiment proves the concept works in practical conditions. Not extreme conditions. Not laboratory curiosities. Conditions where actual devices could operate.

Estimated data shows potential improvements in various technologies due to light-controlled magnetism, with quantum computing seeing up to a 40% enhancement.

Magnons: The Quantum Waves That Make This Possible

Understanding magnons is crucial because they're the actual thing being controlled here, not individual electron spins.

Imagine a perfect crystal lattice where electrons are arranged with aligned spins, all pointing the same direction. That's the ground state of a ferromagnet. Now imagine one electron's spin flips to point the opposite direction. You've created a magnon—technically, a spin-wave excitation, the quantum of magnetic wave oscillation.

But here's the key insight: magnons don't exist in isolation. When you excite a magnetic material, you don't get one flipped spin. You get a coherent collective pattern where many spins oscillate together in a coordinated wave. The whole material ripples with magnetic energy, like a pond's surface when you drop a stone.

This collective behavior matters enormously. A single flipped spin would be chaotic and disordered. A coherent magnon pattern is ordered, predictable, usable. In this experiment, the researchers detected coherent magnons—pristine, regular oscillations in the magnetic system.

The magnon frequency determines the time scale for magnetic dynamics. High frequency means rapid changes. Low frequency means slower changes. By shifting the frequency, you change how fast information can propagate through the magnetic material.

In traditional magnetic storage, information is written by generating large magnetic fields that flip the material's magnetization direction. This happens relatively slowly—nanoseconds or slower. If you could use light to speed up magnon dynamics, you could potentially write information faster, with less energy.

Quantum computing applications are even more intriguing. Magnons can interact with qubits (quantum bits). Controlling magnon frequency with light could provide a new mechanism for quantum control without introducing the electrical noise and heating that current methods generate.

Comparison to Previous Approaches: Why This Actually Breaks Through

Let's be honest about something: scientists have been trying to use light to control magnetism for decades. So why did all those previous attempts fail to translate into practical technology?

The earliest approaches used magnetic resonance. You'd tune a laser to match the energy difference between spin states, resonantly excite the spins, and flip their direction. Elegant in theory. Terrible in practice. It required extremely monochromatic light—lasers with precise wavelengths. More importantly, it only worked at specific temperatures and magnetic field strengths. Scale the device, change conditions slightly, and it stopped working.

Later work showed that ultrafast optical excitation could influence magnetism through different mechanisms. But most demonstrations still required either:

- Cryogenic cooling (as mentioned, impractical)

- Mid-infrared lasers (expensive, not standard lab equipment)

- Bulk materials (not thin enough for modern devices)

- Extreme magnetic fields (impractical for actual devices)

Often, experiments needed multiple conditions simultaneously. This new work eliminated those constraints.

The key difference? Thermal modulation instead of resonant excitation. Rather than trying to precisely match laser energy to spin transitions, the researchers simply let the light heat the material and exploited the resulting shift in anisotropy. No resonance matching required. No ultra-cold temperatures needed. No exotic lasers.

The technical beauty is that thermal heating is robust. It works across a range of laser wavelengths (visible to near-infrared all worked). It works across a range of temperatures (tested at room temperature, but the principle works more broadly). It works with relatively modest external field strengths. Change any of these parameters somewhat, and the effect persists.

Compare this to mid-infrared resonant approaches, where changing wavelength by just a few nanometers kills the effect. Or cryogenic techniques, where warming by a few kelvin ruins everything. The robustness is transformative.

Applications in Hard Disk Drives: Data Storage Gets Faster

Let's ground this in something tangible: your data.

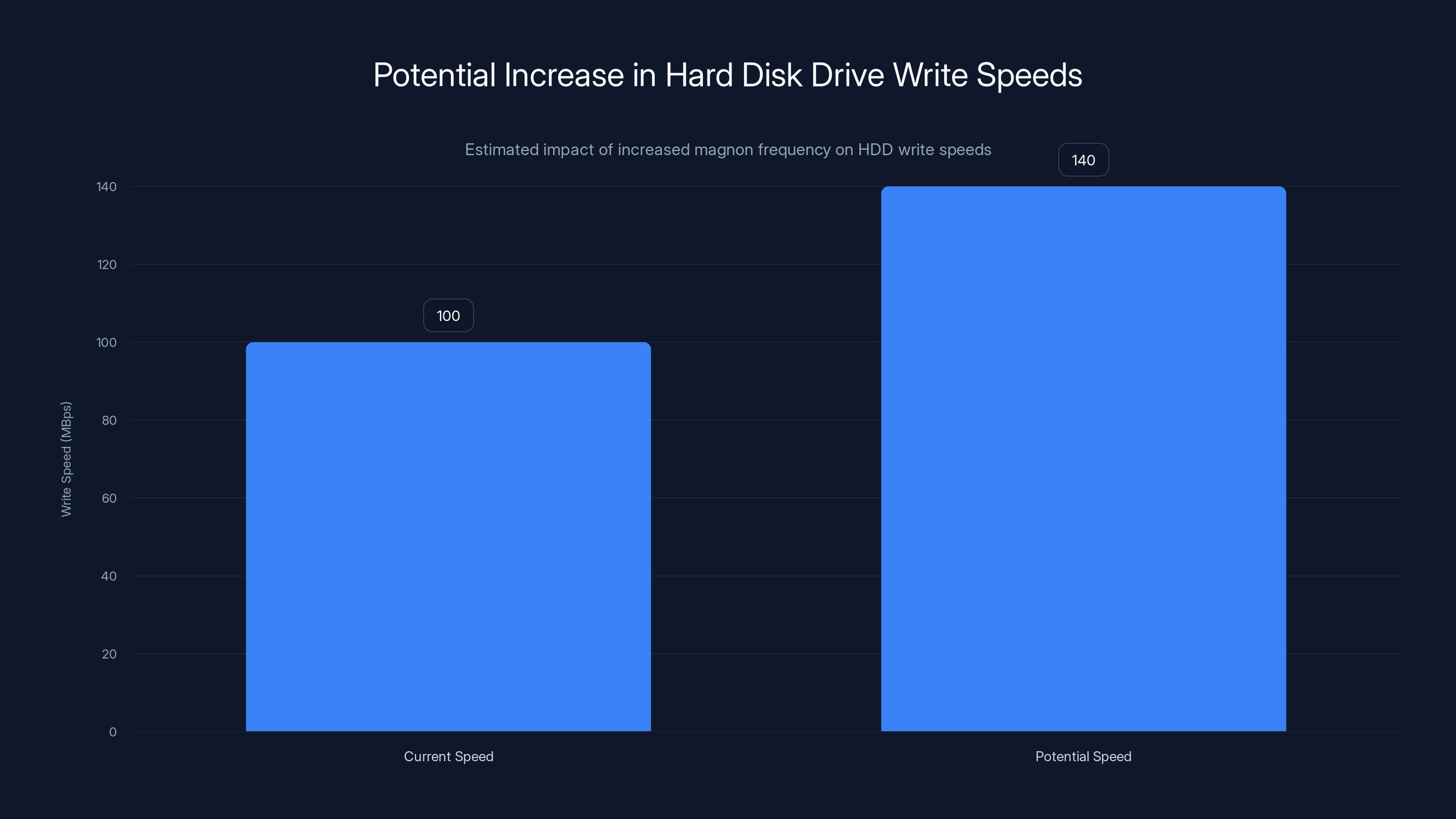

Hard disk drives store information in magnetic domains—regions of material pointing magnetization in one direction represent a "1" bit, opposite directions represent "0." Writing data requires flipping these domains quickly and reliably. Modern drives write at speeds around 60-100 megabits per second, not because of physics limitations but because of how fast magnetic switching can occur without introducing errors.

The fundamental issue is something called thermal stability. The magnetic domain wants to stay in its current state. To flip it to a new state requires either a large magnetic field applied for a long time, or a smaller field applied with tremendous precision. The faster you try to flip the domain, the more likely you'll fail.

What if light pulses could speed up the magnon oscillations that facilitate domain switching? You could potentially flip domains faster without increasing energy input. The magnon frequency shift demonstrated in this research—40% is not trivial—directly translates to faster potential domain dynamics.

Theoretically, increasing magnon frequency by 40% could allow 40% faster write speeds. In practical terms, that might push hard drives from 100 MBps to 140 MBps. On a 1 terabyte drive, that's maybe 20 seconds faster for a full backup. Not revolutionary. But multiplied across data centers with millions of drives, those seconds add up.

The real benefit comes from energy efficiency. If you can achieve the same switching speed with light instead of large electrical currents, you reduce power consumption. Hard drives are already power-efficient compared to solid-state drives in bulk storage scenarios. Making them more efficient tips the scales even further.

And there's another advantage: precision. Optical pulses can be extraordinarily precise—femtosecond timing means microsecond-level control over magnetic switching. Electrical currents involve more noise and distributed heating. Light provides better spatial and temporal control.

The 20-nanometer thin film thickness is also important for drives. Modern hard drives use perpendicular magnetic recording, where magnetization points perpendicular to the disk surface rather than parallel. Thinner magnetic layers for perpendicular recording have advantages: higher density potential, easier switching dynamics, and reduced current requirements. This research shows thin films can be optically controlled, which is exactly the geometry that drives need.

Increasing magnon frequency by 40% could potentially boost hard disk drive write speeds from 100 MBps to 140 MBps, enhancing efficiency and precision. (Estimated data)

Quantum Computing Applications: A New Control Mechanism

Quantum computing has a problem: control and decoherence.

Qubits are fragile. Environmental noise causes them to lose their quantum properties—to decohere—in microseconds or milliseconds. Current quantum computers need elaborate isolation systems: cryogenic cooling, electromagnetic shielding, vibration isolation. Despite these precautions, decoherence limits how long you can run calculations.

One approach to building better qubits involves magnons. You can encode quantum information in magnon states, creating magnonic qubits. These have potential advantages: magnons are collective excitations, so they're somewhat protected against individual particle noise. They can interact with other quantum systems like superconducting qubits or photons.

But controlling magnonic qubits requires manipulating magnon states with precision. Traditional methods use microwave radiation at high power levels, generating noise and heating that causes decoherence. What if you could use optical control instead?

Light interacts with matter differently than microwaves. In the near-infrared and visible spectrum, photon energies are much higher, which could enable more selective manipulation. The femtosecond-scale precision demonstrated in this research is also relevant: quantum operations often need picosecond-scale timing.

Moreover, optical systems might decohere magnonic qubits less than microwave approaches. The mechanism is different. You're not applying gigahertz-frequency electromagnetic fields that couple to unwanted degrees of freedom. You're using light absorption and thermal effects that might couple more selectively.

Researchers haven't yet demonstrated qubits based on this mechanism, but the foundational control demonstrated in the Nature Communications paper is a prerequisite. The paper proves you can manipulate magnons precisely with light in a material at room temperature. That's the first step toward magnonic qubits that might operate in practical devices.

One intriguing possibility: hybrid systems. You could couple magnonic qubits to superconducting qubits using light as the mediator. Light can transmit over distance through waveguides, potentially connecting different parts of a quantum processor. This is speculative—but it's the kind of possibility that opens when you can optically control magnetic systems.

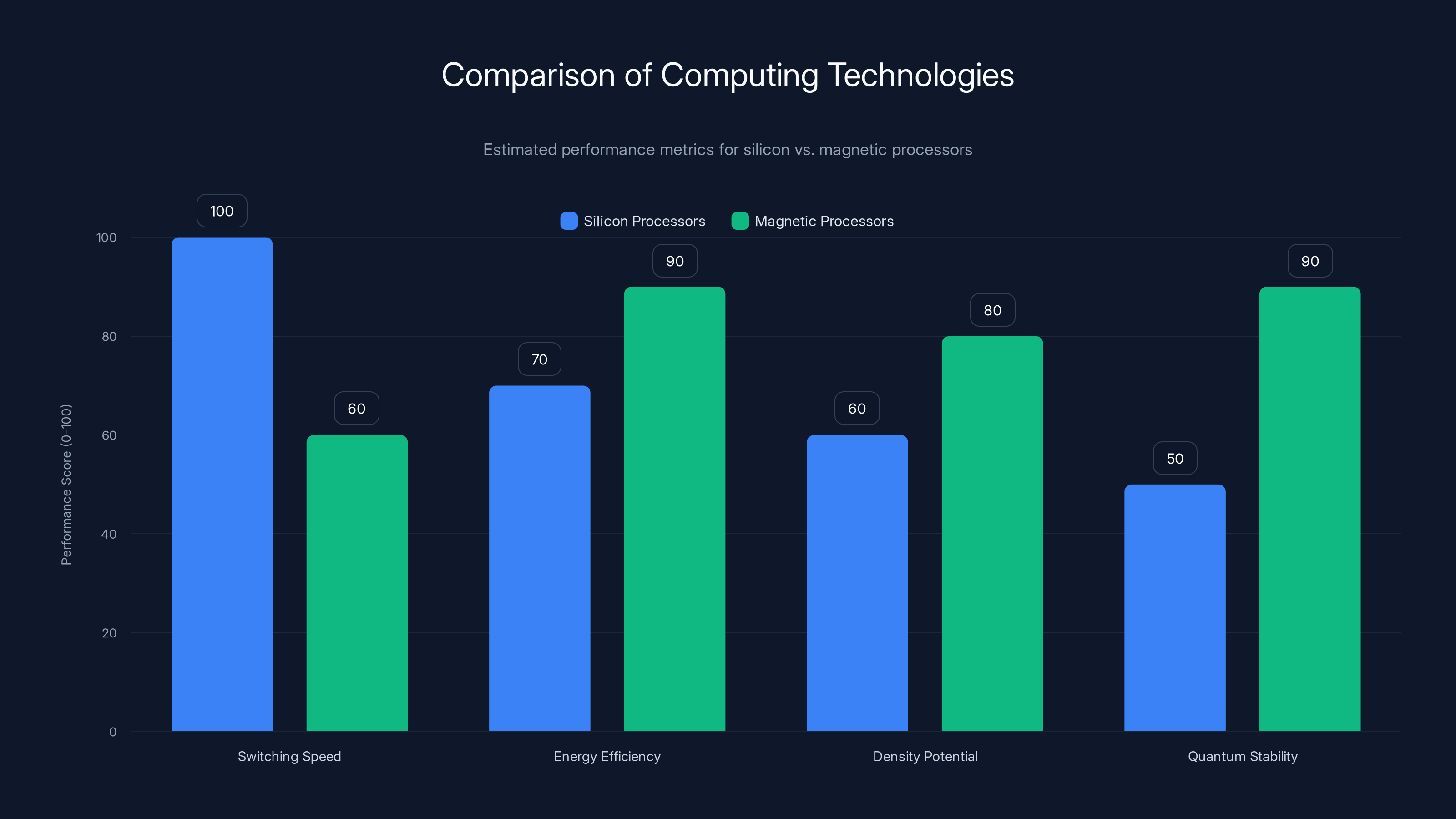

Non-Silicon Processors: Magnetism-Based Computing

Silicon processors have dominated computing for 60 years. But silicon is hitting physical limits. At 2-3 nanometers feature size—where we are in 2024-2025—quantum effects make transistors behave unpredictably. Heat generation becomes catastrophic. Power efficiency plateaus.

The semiconductor industry is exploring alternatives. Magnetic computing is one avenue.

The idea is simple in principle: use magnetic states to represent information rather than electron charge. A magnetic domain pointing up represents "1", down represents "0". Replace transistors with magnetic memory or logic elements.

Why might this be better than silicon? Magnetic states don't suffer from quantum tunneling—electrons can't just quantum tunnel across magnetic domains. Magnetic bits retain their state without constant power, unlike transistors which need power to maintain logic states. Magnetic systems might be inherently more energy-efficient.

The challenge has always been speed. Magnetic switching is slow compared to electron movement in transistors. A transistor can switch nanoseconds or faster. Traditional magnetic switching takes microseconds. You'd lose all speed benefits by switching to magnetism.

Enter optical control. If light pulses can speed up magnon dynamics—or even directly manipulate magnetic states through non-thermal mechanisms still being researched—suddenly magnetic computing becomes faster. The 40% magnon frequency shift in this research translates directly to potentially 40% faster magnetic switching.

Is this enough to make magnetic computing competitive with silicon? Probably not yet. You'd need more than 40% to overcome silicon's speed advantage. But it's movement in the right direction. Combine this with magnetic materials' superior density potential and inherent energy efficiency, and you have an interesting prospect.

Researchers at universities like UC San Diego and companies like Intel have been exploring spin-based logic for years. Most of this work uses electrical or thermal control. Optical control adds another tool to the arsenal.

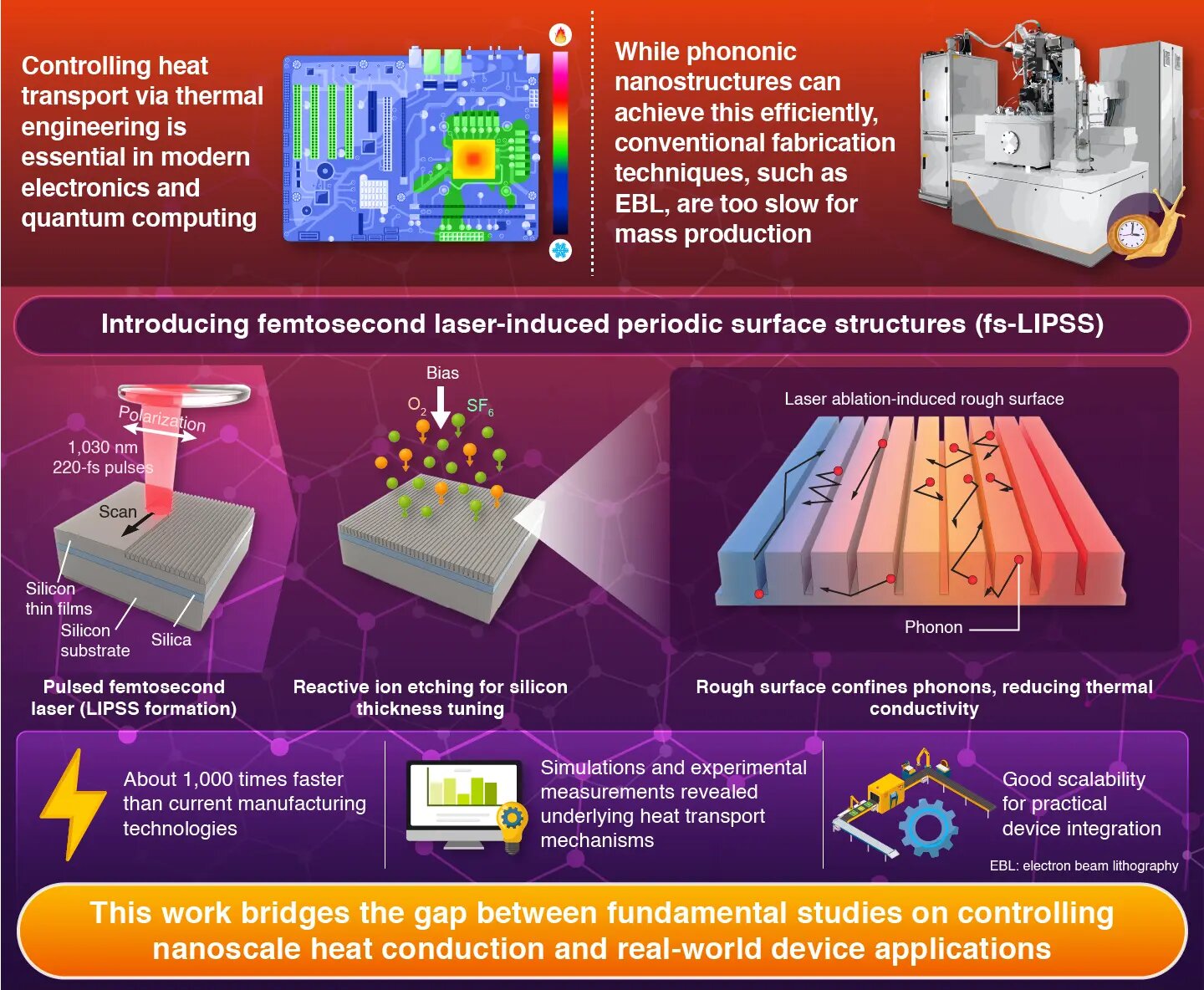

AI Chip Cooling: A Thermal Angle

Artificial intelligence processing generates enormous heat.

A single modern AI accelerator—think NVIDIA H100 GPU—dissipates hundreds of watts. In data centers running large language models, you have hundreds or thousands of these chips. The cooling bills alone become staggering. In some cases, data center cooling costs exceed electricity for the chips themselves.

Most AI chip cooling uses traditional methods: copper heatspreaders, thermal pastes, fans or liquid cooling loops. These are passive solutions that dissipate heat after it's generated. But what if you could prevent some of that heat generation in the first place?

Magnetic computing approaches, if they could achieve practical efficiency, would generate less heat than silicon processors. The optical control demonstrated in this research could be part of making magnetic AI accelerators practical.

But there's another angle. Magnon control itself could be used in thermal management. When you control magnons with light, you're manipulating the flow of energy at the quantum level. In principle, you could create devices that direct thermal energy rather than just dissipating it.

This is speculative territory—we're talking about potential physics, not demonstrated technology. But the principle is sound. Magnons are energy carriers. If you can control them precisely, you control energy flow. Eventually, that might lead to more sophisticated thermal engineering at the nanoscale.

For immediate practical impact, the most relevant application is probably indirect: enabling next-generation processors (magnetic or hybrid) that inherently consume less power than silicon chips, thus generating less heat to cool.

Magnetic processors show promise in energy efficiency, density potential, and quantum stability, but lag behind silicon in switching speed. Estimated data based on current research trends.

The Materials Challenge: Why Bismuth-Substituted Yttrium Iron Garnet?

You might wonder why the researchers chose this specific material. The answer reveals how materials science limits or enables applications.

Yttrium iron garnet (YIG) is a ferrimagnetic compound—Fe 3O12 with yttrium replacing some iron atoms. It's been studied since the 1950s because it has exceptional magnetic properties: high saturation magnetization (the maximum magnetic moment the material can achieve), low damping (magnetic energy dissipates slowly), and high Curie temperature (magnetism persists to high temperatures).

YIG is the industry standard for microwave applications, magnetic resonance work, and magnonic devices. If you wanted to study magnons, YIG is the obvious choice.

But pure YIG has a problem: isotropic magnetization. The magnetic moments don't prefer any particular direction. The material is equally easy to magnetize in any direction. For practical devices, you want anisotropy—preferred magnetization directions. You want the material to resist being magnetized perpendicular to the disk surface (in hard drives) or in certain orientations (in quantum devices).

Enter bismuth substitution. When you replace some yttrium atoms with bismuth, the material develops strong uniaxial anisotropy. The magnetization now prefers to point in specific directions due to the crystal symmetry created by bismuth's particular electron configuration.

Furthermore, the bismuth-doped material developed by growing it on a lattice-mismatched substrate creates strain-induced anisotropy. The gadolinium gadolinium garnet substrate is slightly different size than YIG. When you grow YIG on it, the lattice mismatch creates internal stress—strain—in the YIG film. This strain further enforces out-of-plane anisotropy.

Combining chemical substitution (bismuth) with strain engineering (substrate mismatch) gives you total control over anisotropy strength and direction. This is how materials scientists design properties. Not by luck. By deliberate engineering.

The thickness—20 nanometers—is also deliberate. Thinner materials magnetically couple to surfaces and interfaces differently. At 20 nanometers, you get strong effects from the substrate interaction without the material becoming so thin that imperfections dominate behavior. It's a sweet spot.

Experimental Techniques: Pump-Probe Spectroscopy Revealed

The measurement technique matters as much as the material. The researchers used time-resolved pump-probe magneto-optics. Sound complex? Let's break it down.

"Pump" refers to the first laser pulse that excites the system. This pulse hits the material and disturbs it, creating the magnon oscillations the researchers want to study.

"Probe" refers to the second laser pulse, coming at a controlled time delay after the pump. The probe measures the material's state at that specific moment. By varying the time delay between pump and probe, you build up a picture of how the material evolves in time.

"Time-resolved" means you're taking measurements at femtosecond-scale time intervals—essentially taking ultra-high-speed movies of what happens inside the material.

"Magneto-optics" refers to techniques where light's polarization changes when passing through magnetic materials. As magnons oscillate, the magnetic moment oscillates, which changes how the probe light gets polarized. By analyzing the probe light's polarization, you infer the magnetic state.

Specifically, the team measured Kerr rotation—a subtle rotation of the probe light's polarization due to interaction with the material's magnetization. The amount of rotation directly correlates to the magnetic state. Changes in rotation over time reveal oscillations.

This technique is extraordinarily sensitive. You can detect oscillations with amplitudes of just a few degrees of magnetization change. And you can timestamp these oscillations to femtosecond precision.

The experimental apparatus included:

- A femtosecond laser source (probably a Ti: sapphire laser, the industry standard)

- Optical elements to split the beam into pump and probe paths

- Delay lines to control the time between pump and probe pulses

- Magnetic field coils to apply the external magnetic field

- Sensitive optics and detectors to measure Kerr rotation

- Cryogenic sample holders (for temperature control—though this experiment didn't require extreme cold, it needed precise temperature stabilization at room temperature)

The actual measurements involved scanning the pump-probe delay over a range of picoseconds, measuring magnon oscillation amplitude at each delay. The resulting data—Kerr rotation versus time—reveals the magnon dynamics clearly.

Data Analysis: How Researchers Separated Signal from Noise

Working with femtosecond-scale phenomena is a study in detecting tiny signals.

The magnon oscillations create minuscule changes in optical properties. The Kerr rotation signal might be only millidegrees—thousandths of a degree. Environmental vibrations, thermal drift, laser power fluctuations can all create noise at similar or larger levels.

Researchers overcome this through lock-in detection. The pump laser operates at a specific repetition rate (often kilohertz to megahertz). The detected signal is modulated at this repetition rate. Electronics can then amplify only the signal at that frequency, rejecting noise at other frequencies.

Additionally, measurements are averaged. The experiment is repeated hundreds or thousands of times, and results are averaged. Since random noise has zero average, averaging suppresses noise while preserving the real signal.

The researchers also performed multiple measurements at different pump fluences (laser intensities) and external magnetic fields. This generated a dataset showing how the effect varies with conditions. Consistent, reproducible changes with predictable dependencies on parameters strongly suggest a real effect, not noise.

Finally, they performed simulations based on the theoretical understanding and compared simulations to measurements. When simulation and experiment match quantitatively—not just qualitatively—you have confirmation that the underlying physics is correctly understood.

This multi-pronged validation approach is standard in good physics research. No single measurement proves anything. Multiple independent confirmations build confidence.

Estimated data shows that at low external fields, magnon frequency decreases with temperature, while at high fields, it increases. This illustrates the complex interplay between anisotropy and external magnetic fields.

Limitations and Caveats: What This Research Doesn't Do (Yet)

Let's be clear about the limitations. This is fundamentally important research, but it's not a finished technology.

First, the magnon frequency shift is modulation, not switching. The researchers shifted frequency by 40%, but they didn't demonstrate switching magnetization direction entirely using light. That's a different challenge. Frequency shifts are useful for some applications, but direct switching would be more immediately practical.

Second, the effect requires external magnetic field. You can't create magnetism from nothing using light. You need a background field (they used 200 millitesla) to set up the conditions where magnons exist and can be modulated. This complicates device design. You'd need permanent magnets or electromagnets generating the background field.

Third, the material used is a specialized research compound. Bismuth-doped yttrium iron garnet grown on gadolinium gadolinium garnet substrate with specific strain engineering is not something you'll find in off-the-shelf materials. Researchers chose it because it has optimal properties for this demonstration. Generalizing to other materials, or to practical device materials, requires more work.

Fourth, power efficiency hasn't been analyzed in detail. The research shows you can control magnetism with light, but it doesn't prove this is more efficient than traditional electrical control. The laser itself consumes power. Those femtosecond pulses require high peak power, though the average power might be modest. Real efficiency comparison requires careful energy accounting.

Fifth, the switching speed hasn't been conclusively measured. The magnon frequency increased by 40%, which suggests faster dynamics, but actual magnetic switching timescales depend on several factors. You can't simply assume frequency increase translates to 40% faster switching without detailed dynamical simulations and experiments.

Sixth, this is a single-shot demonstration. The researchers showed it works. They haven't demonstrated repeated, reliable switching of individual bits millions of times. For storage applications, reliability and reproducibility over billions of write cycles matters.

These aren't critiques of the research quality. The work is meticulous and well-executed. These are acknowledgments that there's distance between "fundamental physics demonstration" and "practical technology." That's always true in research. This paper proves a possibility. Turning that possibility into products takes years of additional work.

Future Directions: Where Researchers Are Heading

With this foundation, what comes next?

The most immediate next step is exploring the effect in different materials. Researchers need to understand how broadly this magnon modulation works. Does it work in ferromagnetic materials like iron or cobalt, not just ferrimagnets like YIG? Does it work in magnetic semiconductors? What about synthetic antiferromagnets?

The answer determines practical relevance. YIG is primarily useful for specialized applications. If the effect generalizes to iron or nickel—materials used in actual hard drives and devices—suddenly the technology becomes more relevant.

Second, researchers will investigate scaling this to room temperature operation more completely. The paper demonstrates it works at room temperature, but under modest external fields and in a lab environment. Can you miniaturize the laser systems? Can you create integrated lasers on a chip that sits on top of the magnetic material? That's the engineering challenge.

Third is the speed and efficiency question. Detailed measurements of actual switching times and careful energy accounting will show whether this approach offers real advantages over electrical switching. If it's faster but requires more power, it might not be an improvement.

Fourth, researchers are likely exploring nonlinear effects. So far, the response is fundamentally linear or modestly nonlinear. What if you applied stronger laser pulses? Could you achieve regime where dynamics become qualitatively different? This is where breakthroughs sometimes hide.

Fifth is coupling to other quantum systems. For quantum computing applications, the crucial question is whether you can couple magnonic states to superconducting qubits or photonic qubits. Can you create entanglement between magnons and other quantum systems using optical control? That would be transformative for quantum technology.

Sixth, researchers will work on real-world device integration. This means developing fabrication processes that can create the thin films reliably, integrating optical elements into chip packages, designing control electronics. This work is often unglamorous compared to the physics, but it's essential for practical impact.

Market Implications and Industry Interest

Large technology companies are watching this space.

For data storage companies like Western Digital and Seagate, faster write speeds with lower energy consumption directly impact bottom lines. Hard drive capacity has plateaued around 18-24 terabytes for consumer drives. Write speed and power consumption are the remaining competitive frontiers. If optical control can improve either, it's relevant.

For processor manufacturers like Intel and AMD, exploring alternatives to silicon is existential. Silicon scaling is ending. If magnetic computing or hybrid magnetic-silicon approaches could extend Moore's Law, they're interested.

For quantum computing companies like IBM, Google, and Ion Q, any mechanism to improve qubit control or reduce decoherence is valuable. Magnonic qubits using optical control could be a lever for that.

For material science and laser companies, the market is more indirect but still present. Companies producing thin-film deposition equipment, laser systems, and optical measurement tools see growing demand if these research directions advance.

Nobody's rushing to build products yet. The technology is too immature. But the investment landscape is shifting. VCs and corporate venture arms are increasingly backing optomagnetic research. Universities are recruiting faculty in this area. Conferences are expanding sessions on magnon physics and optical control of magnetism.

The timeline is probably 5-15 years before you see commercial applications. Quantum computing impact might come faster (3-7 years) since quantum systems already operate in specialized environments where optical integration is plausible. Hard drive applications would take longer, given the conservative nature of the storage industry and need for bulletproof reliability.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond the Technology

There's a meta-lesson here worth considering.

Scientists have been studying yttrium iron garnet since the 1950s. Magnons have been theoretically understood since the 1960s. Femtosecond lasers have been available commercially since the 1990s. Strain engineering of thin films is routine in modern materials science. The building blocks for this research existed. What was missing wasn't new physics or new tools. It was the insight to combine them in this specific way.

That pattern repeats constantly in science. Revolutionary breakthroughs often aren't fundamentally new discoveries. They're clever combinations of known ingredients. Someone realizes that Method A (femtosecond laser excitation) can be applied to Problem B (magnetic control) in Scenario C (room temperature) in a way nobody had thought to try.

This has implications for how research is funded and prioritized. Sometimes progress requires long-term, patient investment in fundamental understanding even when immediate applications aren't obvious. The foundational work on YIG and magnons over 70 years enabled this current breakthrough. If that earlier work had been defunded as "impractical," this moment wouldn't exist.

Conversely, it suggests that truly novel breakthroughs might not require dramatically new physics. They require clever insights and willingness to challenge assumptions. In this case, the assumption being challenged was "you need resonant excitation to control magnetism optically." Turns out thermal modulation works fine.

It's a reminder that the boundary between "fundamental research" and "applied research" is blurry. This work is at the intersection. It advances basic understanding of magnon physics while having direct relevance to practical devices.

Conclusion: Light as the New Tool for Magnetism

We've traveled from the problem—that controlling magnetism traditionally required extreme conditions—to the solution: using light to modulate magnetic properties in practical materials at room temperature.

The core insight is elegant. Laser pulses deliver concentrated energy over femtoseconds. That energy warms the material slightly. The warming changes magnetic anisotropy. The anisotropy change alters magnon frequencies. Observable, measurable, controllable.

What makes this breakthrough important isn't one single application. It's the opening of new possibilities across multiple fields. Hard drives could get faster and more efficient. Quantum computers might gain a new control mechanism. Non-silicon processors might become viable. Energy efficiency in computing could improve.

But perhaps most importantly, it demonstrates a principle: sometimes the best solutions hide in plain sight, waiting for someone to see the problem from a different angle.

The 20-nanometer thin film of bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet bathed in light pulses isn't just demonstrating physics. It's demonstrating possibility. It's showing that the assumptions limiting a field might not be fundamental. They might just be how people have always done things.

In technology, breakthroughs often come from realizing that a constraint you thought was mandatory was actually optional. This research does exactly that. It shows that extreme cold, specialized lasers, and specialized conditions aren't necessary to control magnetism optically. Room temperature, visible light, modest magnetic fields are sufficient.

Five years from now, this might lead to commercial technology. Or it might take fifteen years. Or the immediate applications might come in a direction nobody anticipated yet. That's how research works. You publish fundamental discoveries. Others build on them. The market shifts.

What's certain is that this paper moved the needle. It proved something previously considered impractical actually works under practical conditions. That's how progress happens—one impossible thing at a time, until someone makes it possible.

FAQ

What is optical control of magnetism?

Optical control of magnetism refers to using light—usually laser pulses—to directly manipulate magnetic properties in materials without relying on electrical currents or extreme temperatures. In this research, femtosecond laser pulses alter how magnetic excitations (magnons) behave in ultrathin materials by temporarily changing the balance between magnetic anisotropy and external fields through optical heating.

How does light actually change magnetic behavior?

When visible light hits the bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet material in this research, photons are absorbed and create thermal excitation—essentially brief heating at the nanoscale. This temporary temperature increase weakens the material's magnetic anisotropy (the preference for magnetization to point in certain directions). Since magnetic excitation frequencies depend on the balance between anisotropy and external fields, weakening anisotropy shifts the frequencies of coherent magnons by up to 40%, depending on field strength and laser intensity.

Why is room temperature operation important for this technology?

Room temperature operation is crucial because it makes the technology practical. Previous demonstrations of optical magnetism control required liquid helium cooling (below 4 Kelvin) or liquid nitrogen (77 Kelvin), making experiments expensive and equipment cumbersome. Working at room temperature means any lab with standard laser equipment can reproduce the results, and devices could theoretically operate without cryogenic systems, dramatically improving energy efficiency and reducing infrastructure costs for real-world applications.

What are magnons and why do they matter?

Magnons are quantized collective oscillations of electron spins in magnetic materials—essentially waves of magnetic energy that propagate through the material with specific frequencies. Their importance lies in controlling how fast magnetic information can propagate and change. By modulating magnon frequencies with light, researchers can potentially speed up magnetic switching, enable new quantum control mechanisms, and improve magnetic computing speeds without generating excessive heat or requiring large electrical currents.

Could this technology lead to faster hard drives?

Potentially, yes. Hard drives write information by flipping magnetic domains, and switching speed depends partly on magnon dynamics. If optical control can increase magnon frequencies by 40% as this research demonstrates, theoretical write speeds could increase proportionally. However, the technology would need integration into actual hard drive designs, which requires years of engineering. The real advantage might be energy efficiency—achieving current speeds with lower power consumption—rather than raw speed increases, given hard drives already write at practical speeds.

How does this apply to quantum computers?

Quantum computers could use magnonic qubits—quantum bits encoded in magnon states. Controlling magnonic qubits traditionally requires high-power microwave radiation that generates noise and causes decoherence. Optical control using light might offer better selectivity and reduced noise. This research proves you can manipulate magnons precisely with light at room temperature, a prerequisite for developing practical magnonic qubits that could supplement superconducting qubits or create hybrid quantum systems.

What materials does this work with beyond yttrium iron garnet?

That's an open question driving future research. This demonstration used bismuth-substituted yttrium iron garnet specifically because it has ideal properties for this experiment. Whether the effect generalizes to iron, nickel, or other magnetic materials used in practical devices remains to be determined. If researchers prove the effect works broadly, applications become more immediately relevant. If it's limited to specialized research materials, applications remain more distant.

How much power does this optical control actually consume?

That hasn't been comprehensively analyzed yet. The femtosecond laser pulses themselves require significant power to generate, though the average power might be modest. A full efficiency comparison with electrical magnetic switching requires detailed energy accounting including laser system losses, optical components, and detection electronics. This measurement is crucial for determining whether optical control offers genuine advantages for practical applications versus just being scientifically interesting.

Why didn't researchers achieve this breakthrough earlier if all the components existed?

The building blocks—yttrium iron garnet, femtosecond lasers, strain engineering, magnon theory—were available for decades. The breakthrough required the insight that you don't need resonant laser frequencies specifically matched to magnetic transitions. Simply using visible light and exploiting thermal modulation of anisotropy works. This demonstrates how scientific breakthroughs often aren't about new physics but about clever combinations of existing knowledge and willingness to challenge assumptions about how things must work.

What's the timeline for commercialization of this technology?

Realistic timelines probably extend 5-15 years for most applications. Quantum computing applications might emerge faster (3-7 years) since quantum systems already operate in specialized environments suitable for optical integration. Hard drive applications would take longer due to the storage industry's need for proven reliability over billions of write cycles. Processor applications would require successful integration with semiconductor manufacturing, another long development process.

Key Takeaways

- Visible light pulses now control magnetism in nanometer-thick materials at room temperature, eliminating need for cryogenic cooling or specialized lasers

- Magnon frequencies shift up to 40% through optical heating that modulates magnetic anisotropy, with direction of shift dependent on external field strength

- Femtosecond pump-probe spectroscopy reveals real-time magnon oscillations at picosecond timescales, enabling precise measurement of optical magnetism effects

- Room temperature operation makes technology scalable and practical for hard drives, quantum computers, and non-silicon processor development

- Breakthrough combines known physics in novel way, demonstrating how scientific advances often come from creative application of existing knowledge rather than entirely new discoveries

Related Articles

- Laser-Tuned Magnets at Room Temperature: The Future of Storage & Chips [2025]

- Ultrafast Laser Nanoscale Chip Cooling: Revolutionary Heat Management [2025]

- The 11 Biggest Tech Trends of 2026: What CES Revealed [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

- [2025] Unlocking Quantum Potential: Google's Quest with UK Experts

![Light-Controlled Magnetism at Room Temperature: The Breakthrough [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/light-controlled-magnetism-at-room-temperature-the-breakthro/image-1-1768862244798.jpg)