Introduction: The Heat Crisis Nobody Talks About

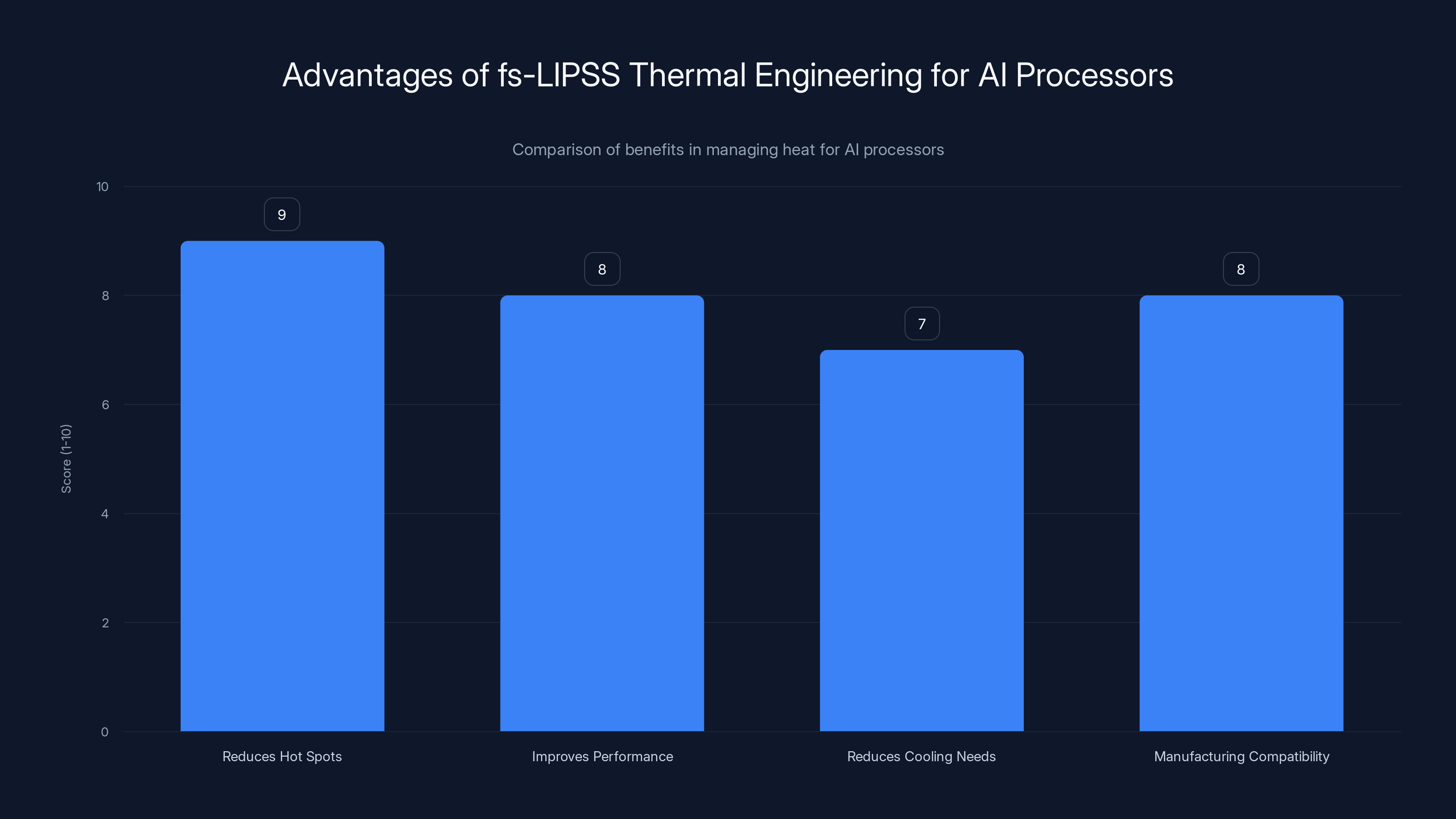

Your GPU is cooking itself. Not in a metaphor kind of way—literally generating enough heat to fry an egg if you weren't already cooling it with fans or liquid loops. This isn't new. Data centers have sweated over thermal management for decades, throwing increasingly expensive cooling solutions at the problem. But here's the thing: the cooling itself is expensive, power-hungry, and frankly, feels like we're treating a symptom instead of the disease.

What if we could make the chips themselves handle heat differently? Not by removing it faster, but by controlling how heat moves through the material in the first place.

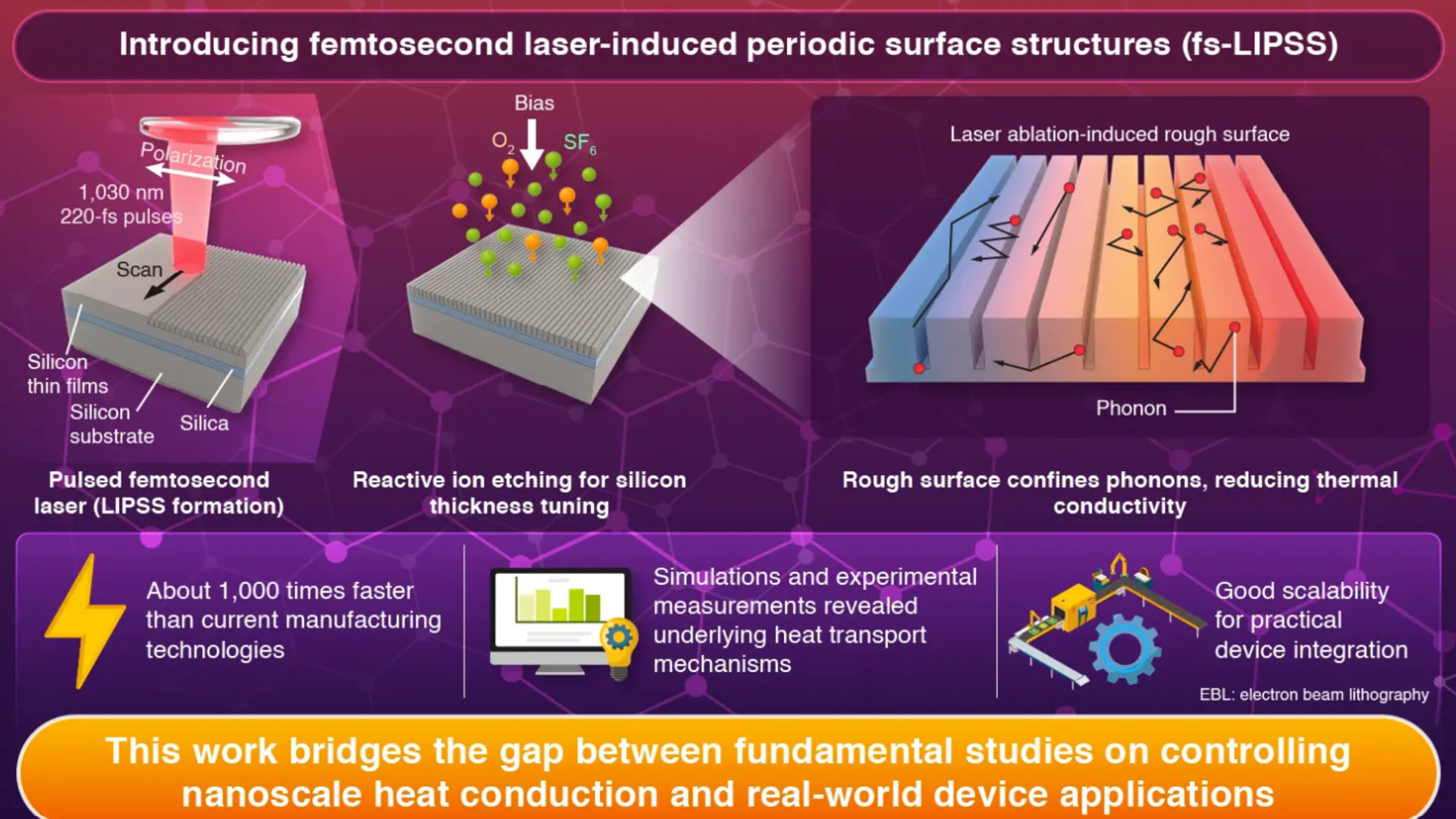

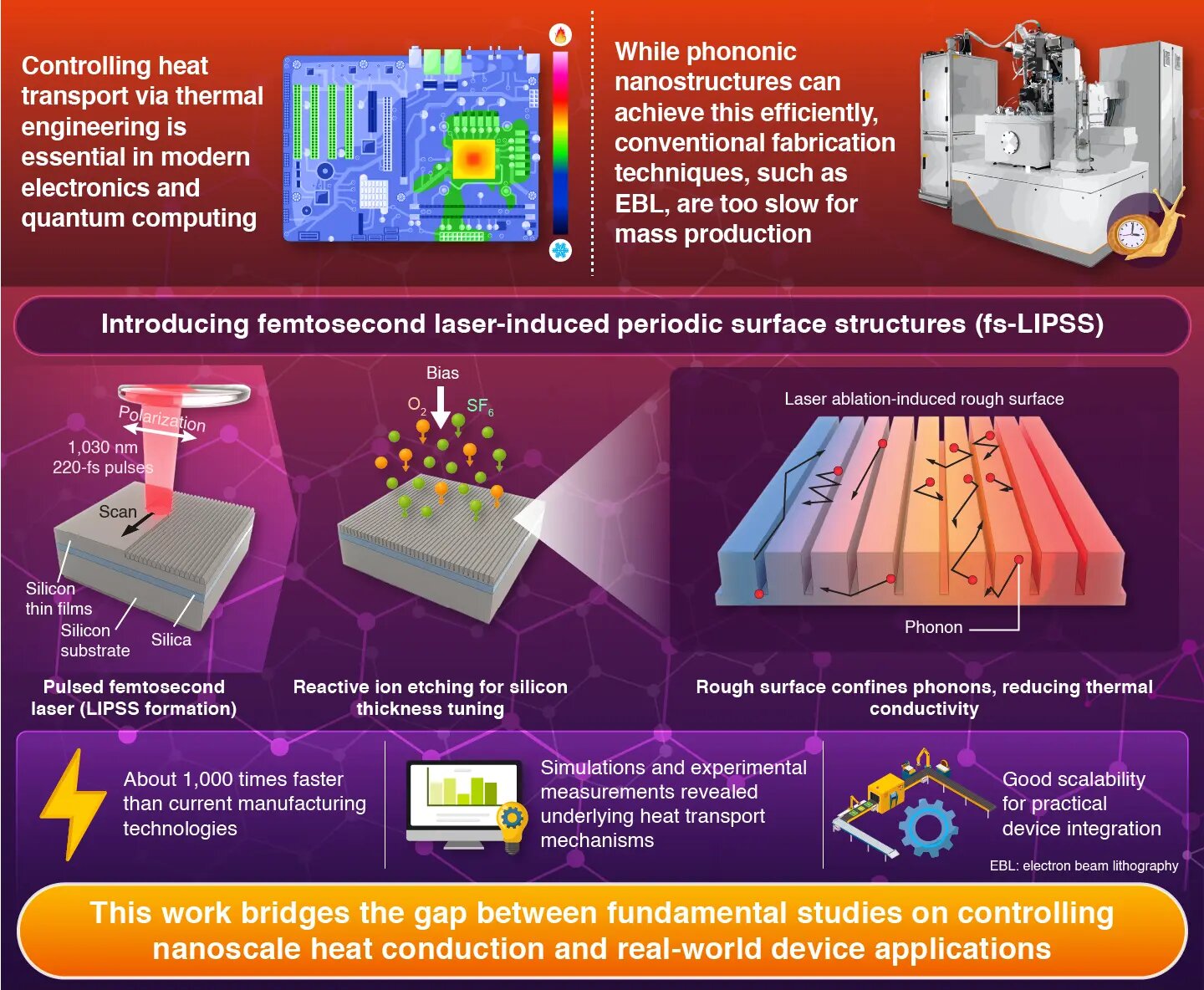

That's exactly what a team of Japanese researchers just demonstrated. They've developed a method using ultrafast lasers to etch nanoscale patterns directly into semiconductor surfaces, fundamentally altering how heat travels through silicon and silica films. The result: thermal conductivity drops dramatically, meaning heat stays localized and doesn't rush through your processor like water through a broken dam.

The technical achievement is stunning—these laser pulses fire light for just one billionth of a second (a femtosecond), precise enough to create structures roughly 1,000 times stronger than conventional nanofabrication methods and 1,000 times faster to produce. But beyond the jaw-dropping specs, this breakthrough has real implications for high-performance computing, quantum devices, and AI accelerators that are consuming more power (and generating more heat) than ever before.

This isn't some theoretical physics paper destined for obscurity. The method is semiconductor-ready, compatible with existing manufacturing workflows, and scalable to wafer-level production. We're looking at a technique that could fundamentally reshape how we cool the next generation of processors—potentially before traditional cooling solutions even enter the picture.

Let's dive into how ultrafast lasers are changing the thermal game, why phonons matter more than you think, and what this means for the future of computing hardware.

TL; DR

- Femtosecond lasers create nanoscale grooves on semiconductor surfaces using pulses lasting one billionth of a second, controlling how heat flows through materials

- Thermal conductivity drops significantly by restricting phonon movement (phonons carry heat), reducing heat buildup before cooling systems even kick in

- 1,000x faster production compared to electron-beam lithography, with 1,000x stronger structures, making the process industrially viable

- Semiconductor manufacturing-compatible with existing CMOS workflows, no exotic equipment or special masks required

- Applications span AI chip cooling, quantum computing, and high-performance processors facing thermal challenges from increasing power density

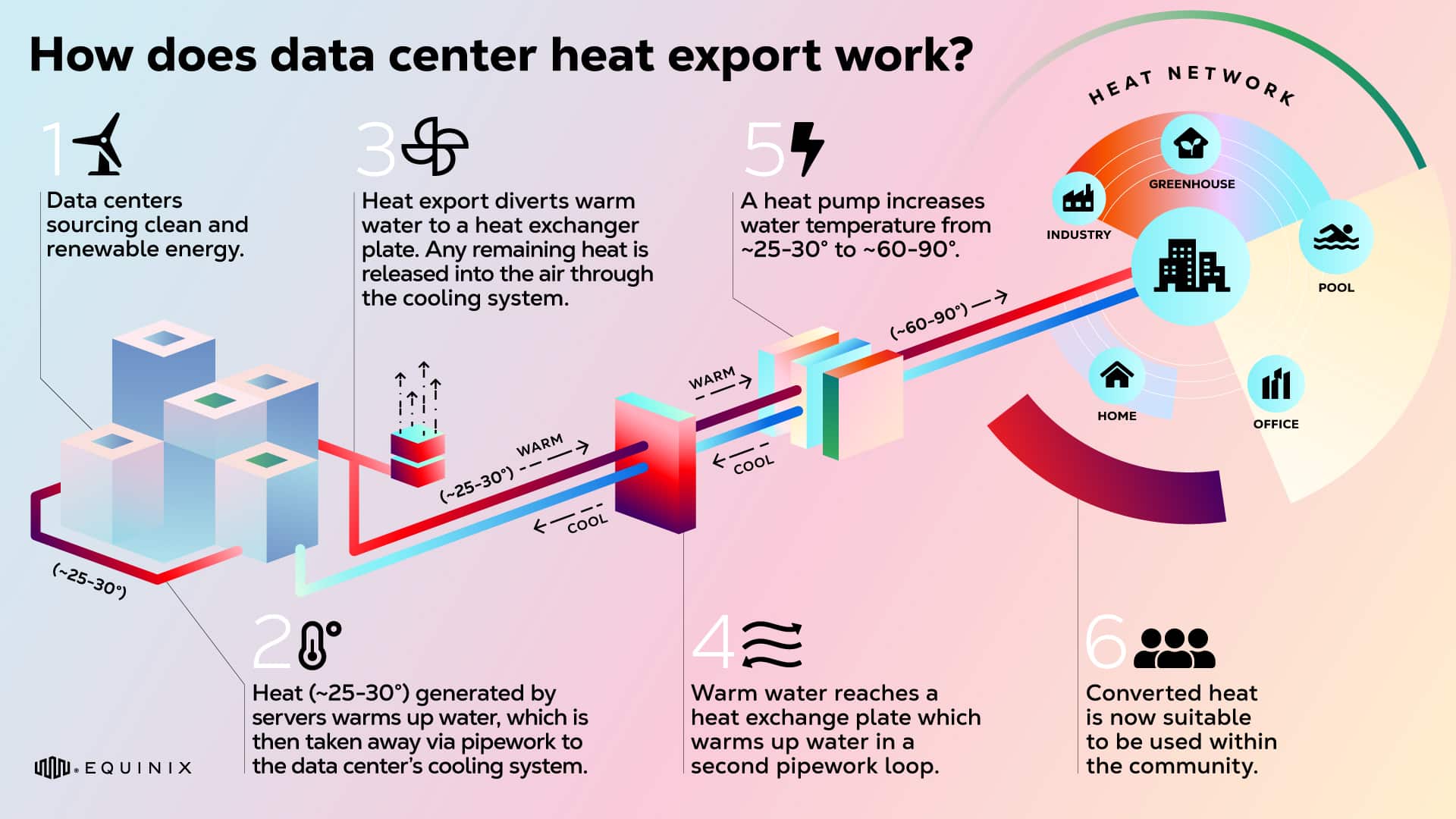

AI accelerators and CPUs consume significant power, with cooling systems adding 5-20% to data center power usage. Estimated data for cooling based on average facility consumption.

Understanding Heat Transport at the Microscopic Level

Why Thermal Conductivity Matters More Than You Think

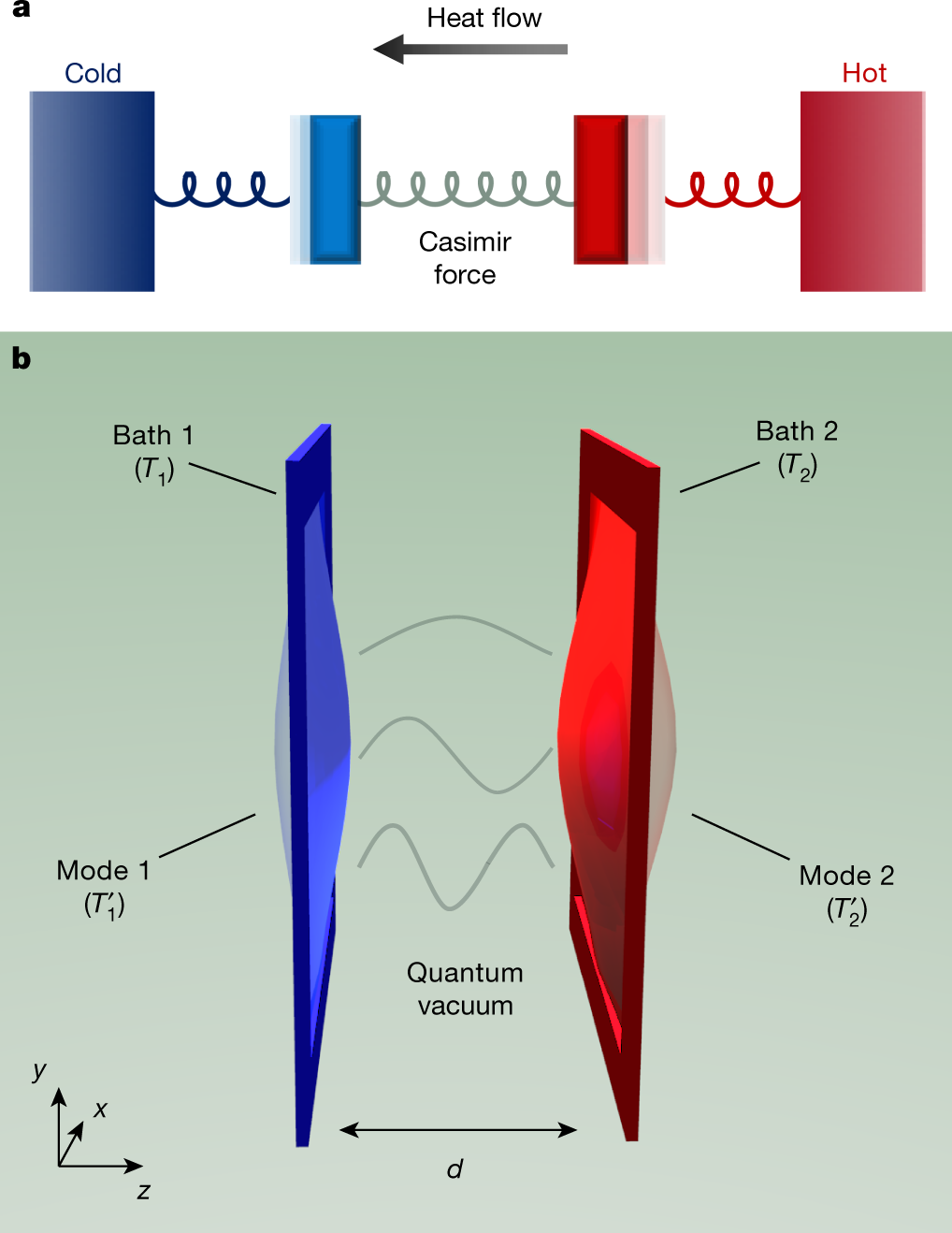

Heat in semiconductors doesn't move the way you'd expect. It's not like thermal energy flowing through a copper pipe at the macro level. Instead, heat in solid materials travels via phonons—quantized vibrations of atoms in the crystal lattice. Think of phonons as tiny acoustic waves bouncing around inside the material, carrying thermal energy from hot regions to cooler ones.

In conventional silicon and silica, phonons travel relatively unobstructed. They bounce around, sure, but they cover significant distances before scattering (losing their thermal energy). This is why silicon conducts heat pretty efficiently by default. It's useful in many contexts, but when you're trying to prevent heat buildup in a chip running at high power, that efficiency becomes a liability.

The key insight from this research is deceptively simple: if you artificially restrict how far phonons can travel before hitting a barrier, you reduce the material's thermal conductivity. Lower conductivity means heat moves more slowly through the material, creating localized thermal zones instead of rapid heat diffusion. Instead of fighting heat after it accumulates, you're preventing the accumulation in the first place.

The Phonon Mean Free Path: A Crucial Measurement

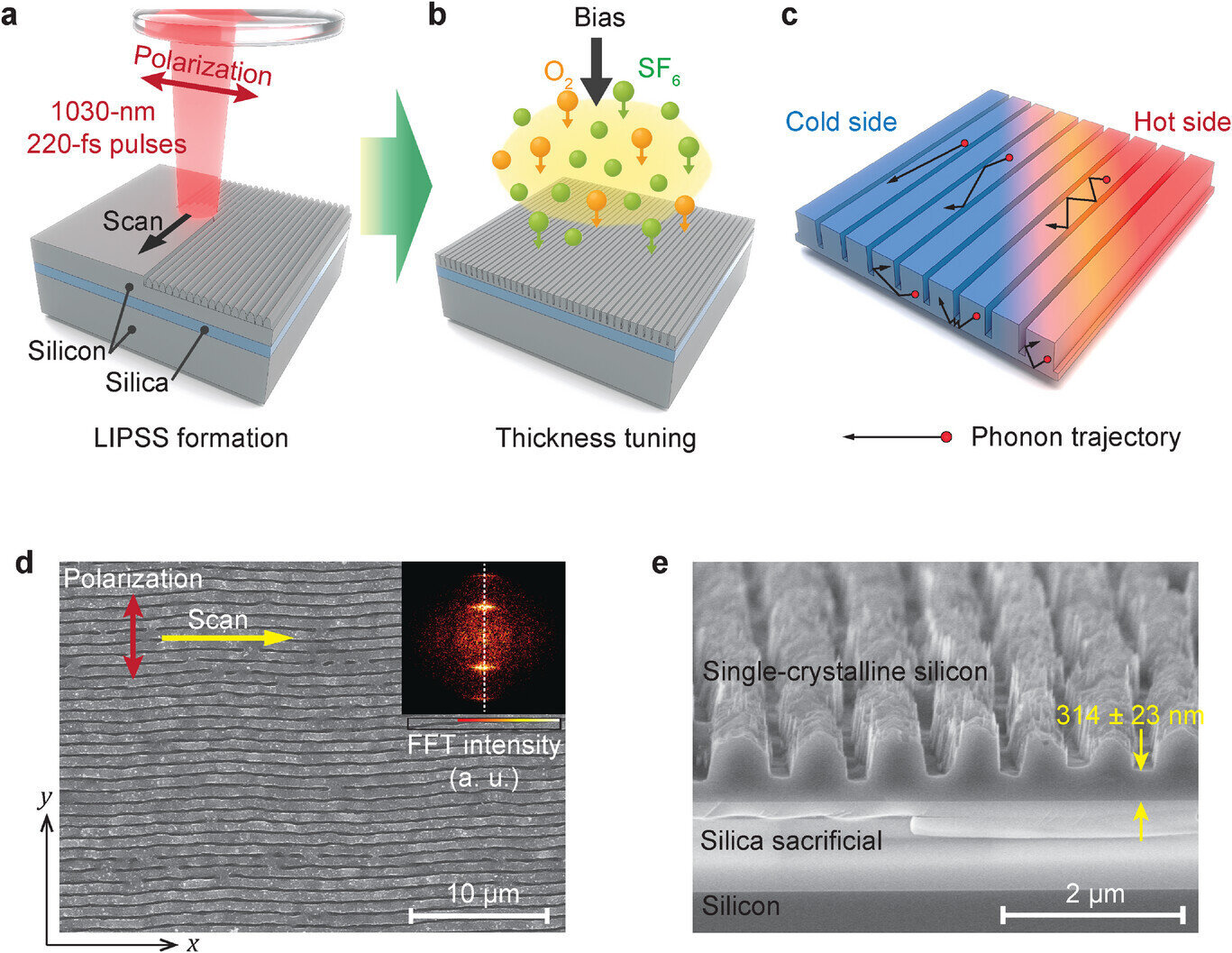

Phonons have something called a mean free path—the average distance they travel before scattering. At room temperature, the phonon mean free path in silicon is roughly 100 to 300 nanometers depending on the type of phonon and crystal orientation. This measurement is central to the entire breakthrough.

The researchers designed their nanoscale grooves with spacing and depth that closely match these natural scattering distances. By doing this, they artificially shortened the effective mean free path, forcing phonons to encounter barriers much more frequently than they would in untreated material. Each barrier interaction interrupts the phonon's journey, dissipating thermal energy more locally.

It's like creating invisible walls in the material that disrupt the phonon flow. The phonons keep moving (they don't disappear), but their thermal transport capability drops significantly because they're constantly colliding with engineered features instead of traveling in relatively straight paths.

From Theory to Measurable Reality

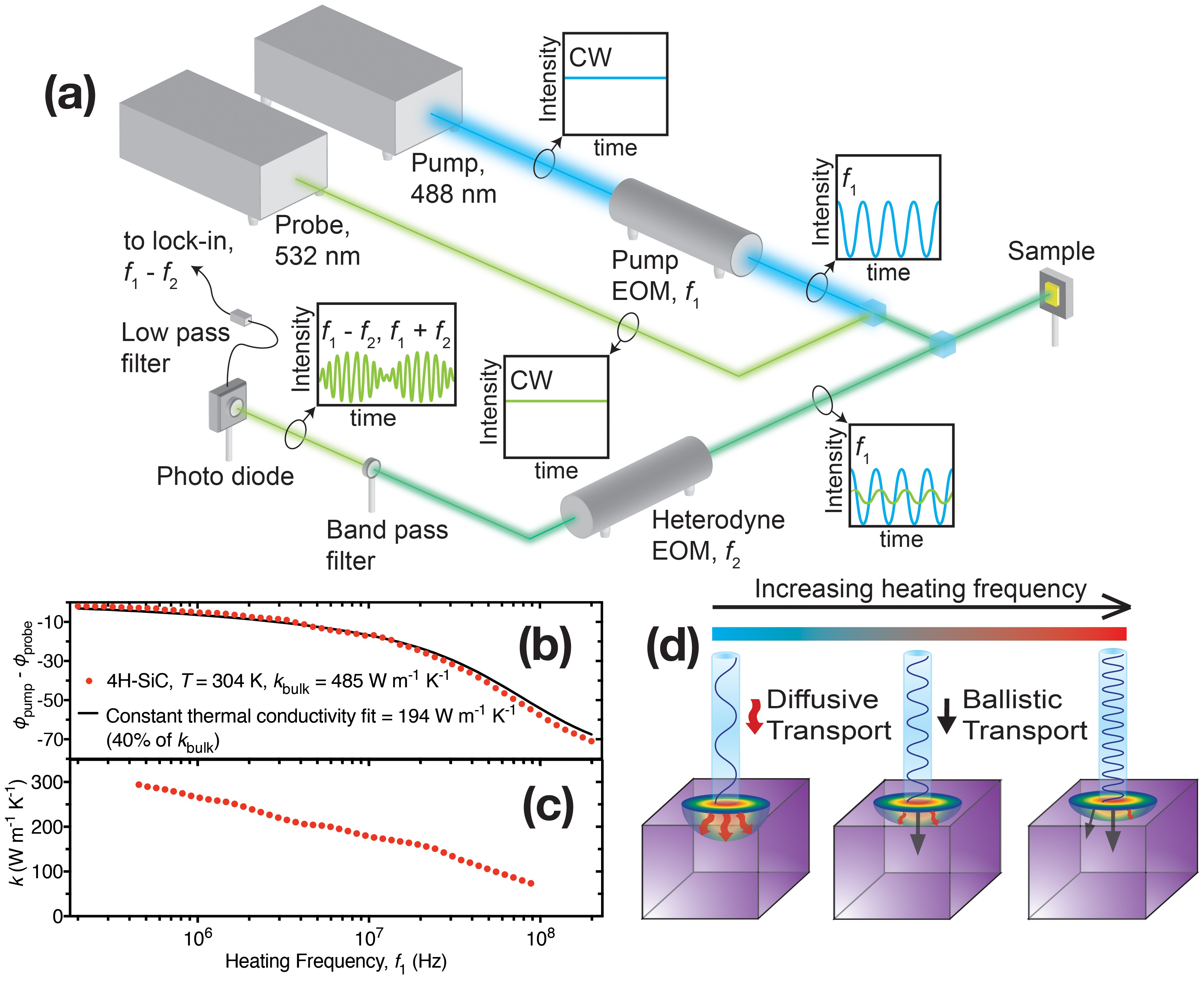

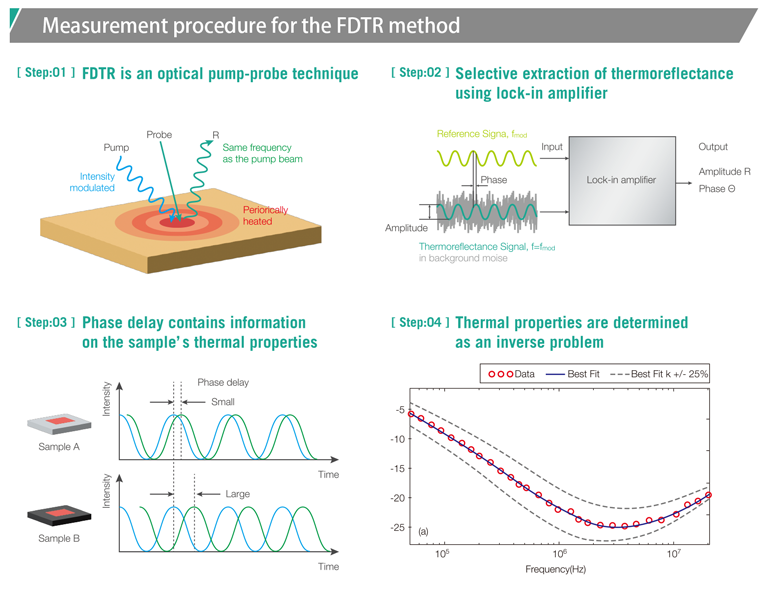

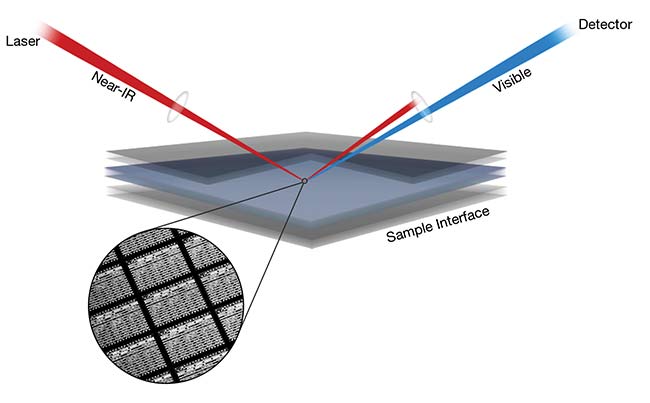

The researchers didn't just rely on theory. They used thermoreflectance measurements to quantify the actual thermal conductivity changes. This technique works by observing how a material's optical reflectivity changes with temperature—essentially using light to measure thermal properties without direct contact.

The data showed real, significant reductions in thermal conductivity compared to untreated control samples. Numerical simulations confirmed that these reductions came primarily from restricted phonon travel, not from chemical composition changes or bulk material property shifts. The grooves physically altered heat transport without degrading the silicon or silica itself.

This distinction is crucial: the material remains chemically unchanged. The silicon is still silicon. But its thermal behavior has been fundamentally reengineered through architecture alone. You're not relying on exotic new materials or rare-earth dopants. You're using geometry to control physics.

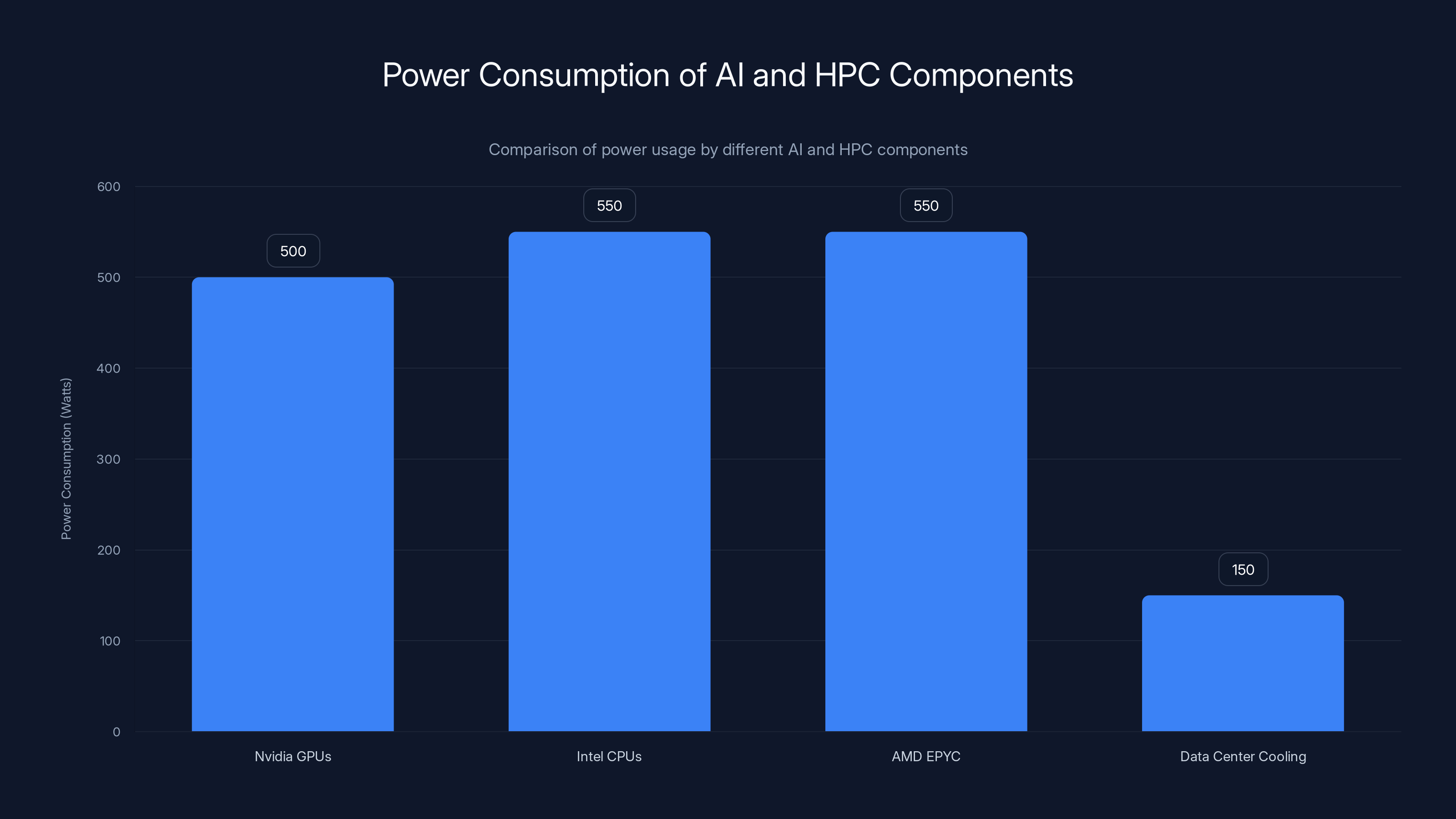

fs-LIPSS thermal engineering significantly reduces hot spots and improves performance in AI processors, making it a valuable technology for managing high heat densities. Estimated data.

The Laser Technology: Femtosecond Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures

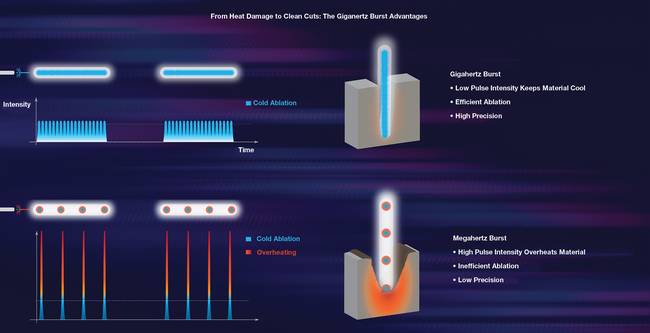

What Makes Femtosecond Lasers Special

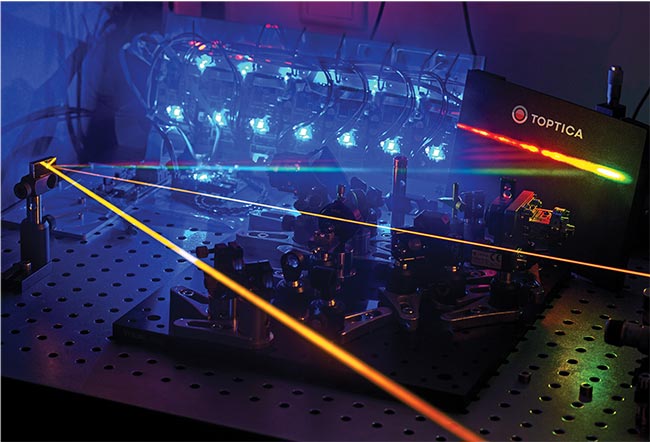

Most industrial lasers operate on timescales of nanoseconds or picoseconds. A femtosecond laser is orders of magnitude faster—firing pulses lasting just one quadrillionth of a second (10^-15 seconds, or one millionth of a nanosecond). To give you perspective: light travels about one micron in a single femtosecond. That's incomprehensibly fast.

Why does this speed matter? At femtosecond timescales, the laser pulse interacts with material in ways that are fundamentally different from longer-pulse lasers. Traditional thermal effects don't have time to develop. Instead, you get non-thermal ablation—the laser essentially rips atoms directly out of the material through photon-matter interaction, without heating the surrounding material excessively.

This precision is the game-changer. Femtosecond lasers can create features with nanometer-scale precision while minimizing collateral damage to the surrounding material. There's no large heat-affected zone, no material degradation from thermal stress, no unwanted phase changes. Just clean, controlled material removal exactly where you want it.

Femtosecond Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures (fs-LIPSS)

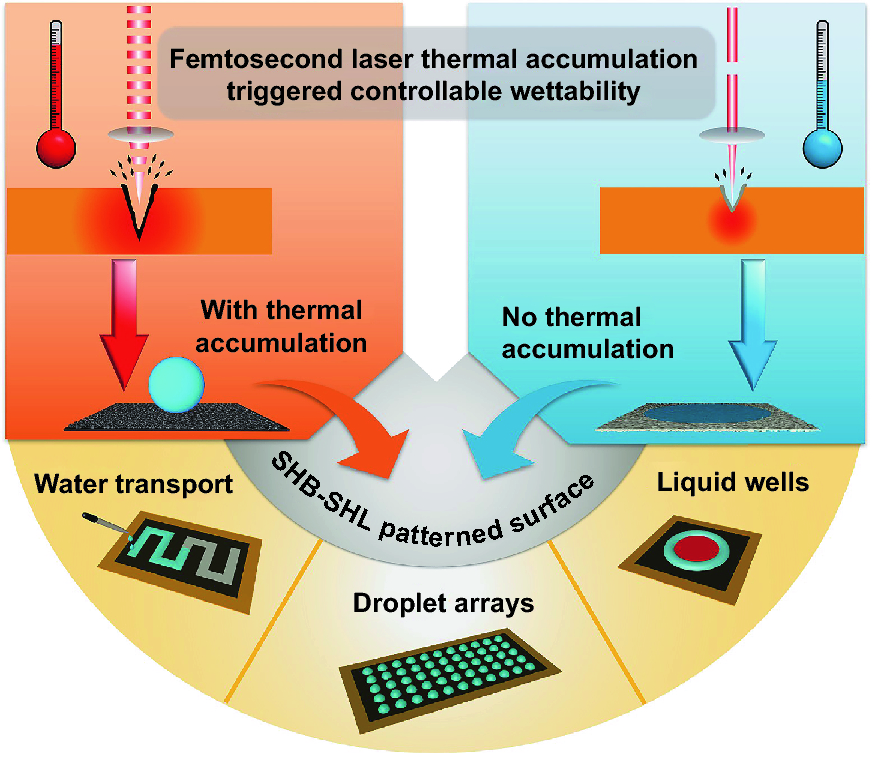

The technique used here is called fs-LIPSS—femtosecond laser-induced periodic surface structures. When a femtosecond laser strikes a material surface with the right parameters (wavelength, fluence, pulse count, etc.), it creates regular, periodic grooves with remarkable uniformity.

The process isn't magic, but it looks like it. The laser pulse ablates material, but interference patterns and non-linear effects create self-organized structures. Tweak the laser parameters—wavelength, power, pulse duration, scan speed—and you can adjust the groove spacing, depth, and width. This programmability is what makes the approach industrially viable.

Here's what happens in practice: the laser scans across the semiconductor surface, firing pulses in a controlled pattern. Each pulse removes a tiny amount of material, creating microscopic grooves. As the laser continues scanning, these grooves form regularly spaced parallel patterns. The result: a textured surface with features around 100-500 nanometers in size, depending on the exact parameters.

Uniformity at Scale: The Manufacturing Challenge

One of the biggest advantages of fs-LIPSS is that it naturally produces high uniformity over relatively large areas. This isn't a process where every feature is slightly different or degrades at the edges. The self-organizing nature of the underlying physics tends to produce consistent structures across centimeter-sized patches—which is exactly what you need for manufacturing semiconductor layers.

Conventional nanofabrication methods struggle with this. Electron-beam lithography, for example, writes patterns one tiny area at a time, pixel by pixel. It's incredibly precise for individual features, but scaling up to large areas becomes a serial, time-consuming process. You can spend hours lithographically patterning a single wafer.

Femtosecond laser patterning, by contrast, creates patterns across entire regions in minutes. The laser scans the surface, and the physics does the heavy lifting. This is why the throughput advantage is so dramatic—the research claims 1,000x faster speeds compared to electron-beam lithography for equivalent feature sizes and surface areas.

Manufacturing Integration: CMOS-Compatible and Scalable

Why CMOS Compatibility Matters

The semiconductor industry has spent decades optimizing manufacturing around CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) technology. Every step of the process—deposition, photolithography, etching, annealing—is tuned to produce chips reliably and economically.

When researchers develop a new fabrication technique, they face a crucial question: does it fit into existing workflows? Or does it require expensive new equipment and completely redesigned processes? The former dramatically increases the likelihood of adoption. The latter often means the technology stays in labs.

The fs-LIPSS technique is maskless and resist-free. It doesn't require photomasks (those expensive template slides used in standard lithography) or resist layers (polymers that protect parts of the surface during etching). This simplification alone makes it compatible with existing manufacturing lines. You're essentially adding a laser patterning step—potentially after conventional processing—without disrupting the established workflow.

Moreover, the technique doesn't introduce new materials or chemical processes that need special handling or environmental controls. It's a pure physical process: laser, material, patterning. The resulting nanoscale grooves are just topography—geometry, not chemistry. Existing inspection and measurement tools can verify the patterns. Existing downstream processes can continue as normal.

Wafer-Scale Implementation Without Additional Steps

The research suggests the technique is suitable for wafer-scale implementation. This means you could pattern entire 300mm wafers (the current industry standard) without introducing additional processing steps or exotic equipment. The laser system would scan the wafer surface, creating the desired thermal management structures across the entire thermal layer or heat-spreading component.

This is a massive advantage. If every chip in a data center processor could benefit from this built-in thermal engineering, and you're not adding significant manufacturing complexity or cost, you've got a technology that could see rapid adoption.

The practical implementation would likely involve:

- Post-lithography integration: After standard chip fabrication, before final assembly

- Selective patterning: Applying the nanostructuring only to thermal management layers or heat-spreading regions

- Quality verification: Using automated optical inspection to confirm pattern uniformity

- Seamless handoff: Sending wafers to standard packaging and testing workflows

No new tools required beyond the femtosecond laser system itself. No new chemical handling. No exotic materials. Just geometry, created by light.

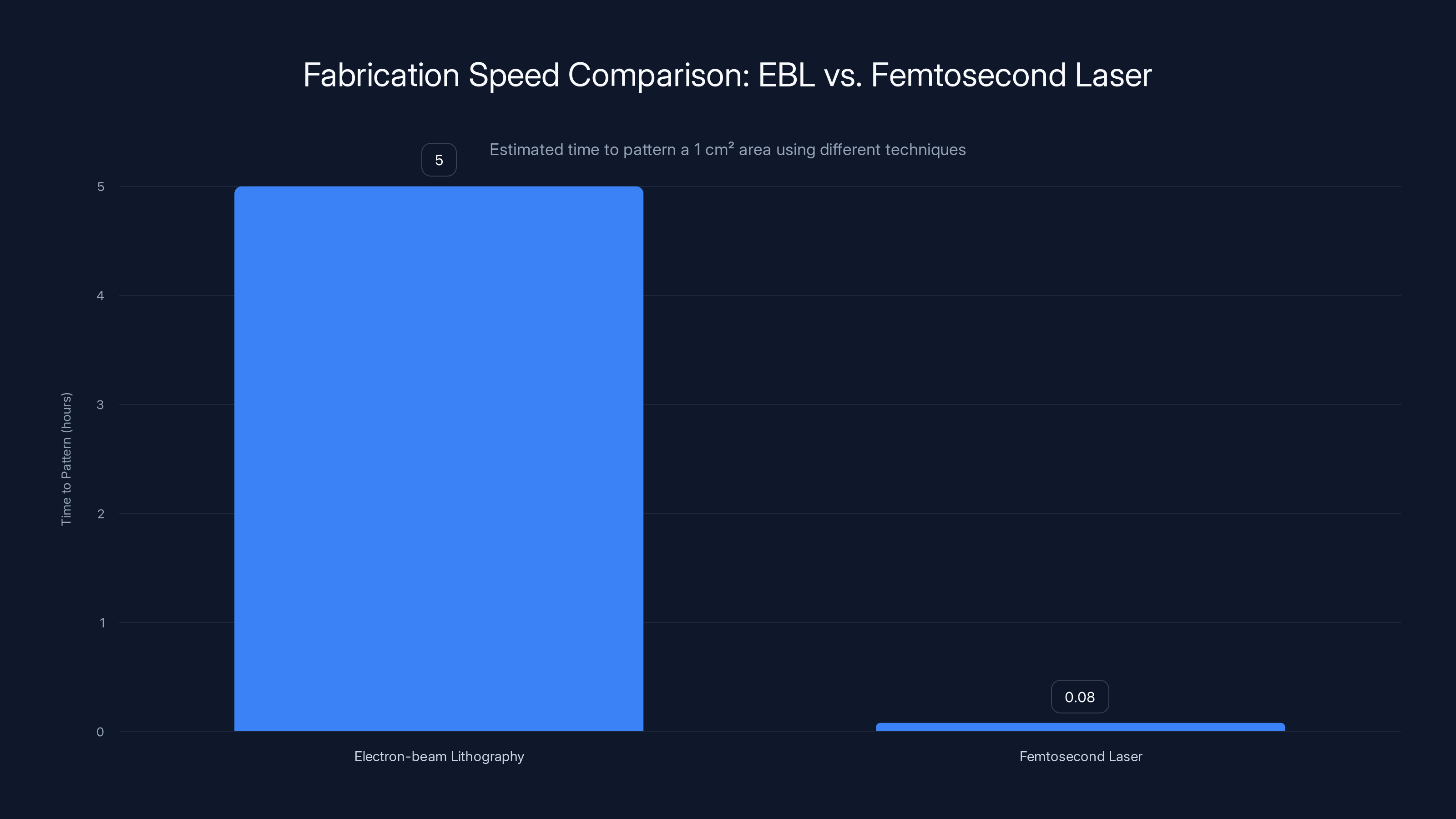

Femtosecond laser patterning is approximately 1,000 times faster than electron-beam lithography, making it a feasible option for production-scale manufacturing. Estimated data.

Thermal Conductivity Reduction: How Much Better?

Quantifying the Performance Improvement

The research shows significant reductions in thermal conductivity, though the exact percentages vary depending on material, groove parameters, and measurement conditions. Thermoreflectance measurements confirmed these reductions experimentally rather than relying on simulations alone.

For context, typical silicon has a thermal conductivity around 150 W/(m·K) at room temperature. Reducing that by even 20-30% drops it to 105-120 W/(m·K)—a noticeable change that would reduce heat flow rates proportionally.

The mechanism is straightforward: restrict phonon movement, reduce thermal transport. The nanogrooves act as scattering centers, breaking up the long, efficient phonon paths into many shorter segments. Each scattering event dissipates energy more locally.

Comparing to Conventional Approaches

Traditional thermal management relies on downstream cooling—removing heat after it's been generated and distributed. This requires:

- Heat sinks with high thermal conductivity (copper, aluminum)

- Thermal interface materials to connect chips to coolers

- Active cooling (fans, liquid loops) consuming additional power

- Complex thermal routing and spreader layers

All of these add cost, complexity, and power consumption. A typical high-end processor might require 5-10 watts just to run the cooling system, which is pure overhead.

The fs-LIPSS approach is different. It's upstream heat management—controlling how heat distributes from the source rather than racing to remove it afterward. Heat still needs to dissipate eventually, but the nanostructured material prevents hot spots from forming in the first place. This means:

- Smaller cooling infrastructure needed

- Lower cooling power consumption

- More uniform thermal distribution

- Reduced thermal stress on components

- Longer component lifespan

The end result is a system that's more efficient overall, not just locally.

Mechanical Properties: Strength and Durability

The 1,000x Stronger Claim

Beyond thermal properties, the research reports that nanostructures created via fs-LIPSS show mechanical strength up to 1,000 times higher than structures produced using some conventional patterning approaches. This claim deserves careful scrutiny—what exactly does "1,000x stronger" mean?

Conventional patterning methods (like deep reactive ion etching or wet etching) can create rough sidewalls and stress concentrations at the nanoscale. These defects act as crack initiation points, reducing structural strength. Femtosecond laser ablation, by contrast, creates relatively smooth structures with minimal defects and stress concentrations.

When you compare smooth, defect-free nanostructures (from fs-LIPSS) to rough, defect-laden structures (from older methods), the strength difference can indeed be dramatic. The 1,000x figure likely represents a favorable comparison, but the exact context matters.

For thermal management applications, this mechanical robustness is valuable. The nanogrooves won't degrade from thermal cycling, vibration, or mechanical stress. They'll maintain their geometry and function for the lifetime of the device. This is critical for data center processors, which operate continuously and endure thousands of thermal cycles over their operational lifetime.

Durability Under Real-World Conditions

One lingering question: how do these structures hold up in practice? The research describes them as "mechanically robust," but limited field data exists yet. However, we can reason through this:

The grooves are created directly in the silicon lattice—they're not coatings or overlays that could flake off. Once patterned, the nanostructure is part of the material itself. It won't degrade from oxidation, moisture, or thermal stress in the way a surface treatment might.

The depth of these grooves (typically 100-500 nanometers) is shallow enough that they don't significantly weaken the bulk material. You're modifying the surface, not compromising structural integrity. Silicon is already tough and chemically stable—adding some surface texture doesn't change that.

For AI chips running at high power, this reliability is crucial. You can't have thermal management structures that degrade over months of operation. The nanogrooves need to maintain their geometry indefinitely.

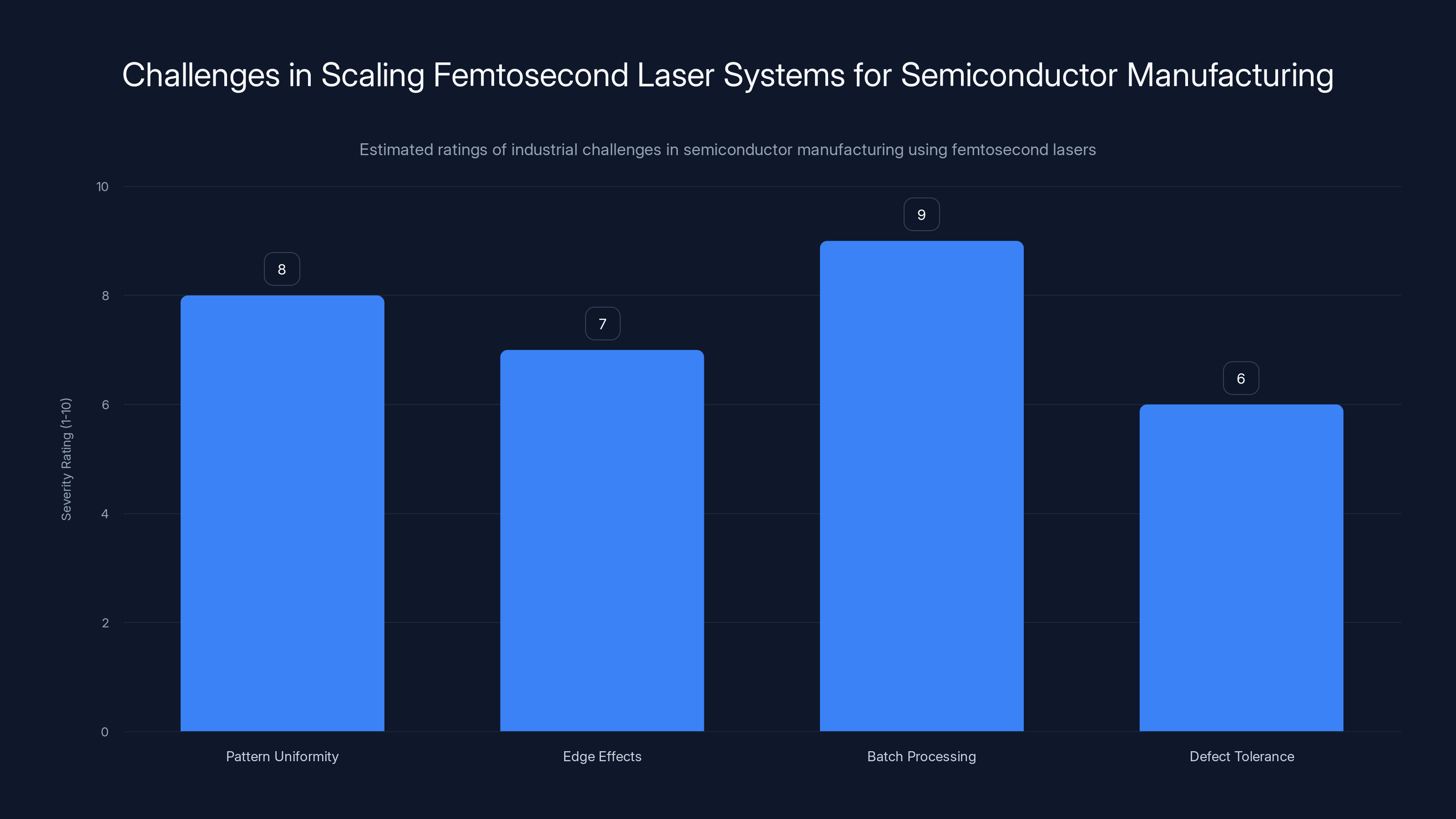

Pattern uniformity and batch processing are the most severe challenges in scaling femtosecond laser systems for semiconductor manufacturing. Estimated data.

Applications in AI and High-Performance Computing

The AI Chip Thermal Crisis

Modern AI accelerators are power hogs. Nvidia's latest flagship GPUs consume 400-600 watts. Intel's server CPUs push 500+ watts. AMD's EPYC processors hit similar numbers. When you pack billions of transistors into a small area and clock them at several gigahertz, the power density becomes extreme—sometimes exceeding 1,000 watts per square centimeter in localized regions.

This heat concentration creates thermal challenges that traditional cooling can barely manage:

- Hot spots form in dense compute regions, limiting clock speeds

- Temperature gradients stress the material, causing warping and reliability issues

- Cooling becomes the limiting factor in processor design, not transistor speed

- Power consumed by cooling systems (fans, pumps, thermal management) grows with the heat

Data center cooling already consumes 5-20% of total facility power depending on climate and cooling approach. For facilities running thousands of high-performance processors, that's an enormous operating cost.

Femtosecond laser thermal engineering could shift this equation. By controlling heat generation at the source—preventing hot spots from forming—you reduce the cooling burden significantly. A processor that generates less localized heat needs less aggressive cooling, which means less power consumption overall.

Quantum Device Thermal Management

Quantum computers face a different thermal challenge. Many quantum processors (superconducting qubits, trapped ions, quantum dots) operate at temperatures near absolute zero—millikelvin or below. At these extreme temperatures, heat becomes the enemy. Even tiny amounts of thermal energy can cause decoherence—loss of quantum information.

Quantum engineers spend enormous effort isolating quantum processors from thermal noise. They use dilution refrigerators consuming kilowatts of cryogenic cooling to maintain millikelvin temperatures. Some of that cooling capacity is wasted on removing heat from classical control electronics, interconnect wiring, and measurement apparatus built around the quantum processor.

If you could use fs-LIPSS to create low-thermal-conductivity structures for these classical components, you could reduce heat flowing into the cryogenic system. This might allow smaller, cheaper quantum computers or improve coherence times—both valuable for quantum computing development.

GPU Cluster Thermal Economics

Consider a large AI training operation: hundreds or thousands of GPUs running 24/7. The power bill is enormous. Thermal management infrastructure—cooling towers, chillers, fans, liquid loops—is expensive to install and maintain.

Suppose fs-LIPSS thermal engineering reduces the effective thermal conductivity of heat-spreading layers by 30%. This means:

- Peak temperatures in the GPU drop by several degrees

- Cooling system efficiency improves (smaller temperature gradients)

- Cooling power consumption drops (less aggressive cooling needed)

- Processor thermal throttling decreases (higher clocks sustained at same temperature)

Even a 5-10% reduction in cooling power across a large cluster translates to millions of dollars annually. The ROI for implementing this technique in leading-edge data centers is compelling.

Fabrication Speed: 1,000x Faster Than Alternatives

The Electron-Beam Lithography Comparison

Electron-beam lithography (EBL) is the gold standard for nanoscale pattern writing. It's incredibly precise—you can create features smaller than 10 nanometers if you're patient and skilled. But "patient" is the operative word.

EBL works by scanning a focused electron beam across a resist-coated surface, one pixel at a time. The electron beam is tightly focused, roughly 10-20 nanometers in diameter. To pattern a 1 cm × 1 cm area at 10 nanometer resolution, you need to address billions of individual pixels. This takes hours. Multiple hours. Sometimes a full day.

For large areas or production quantities, EBL is prohibitively slow. It's a research tool, not a manufacturing process. You can make single prototypes or small samples, but scaling to production volumes doesn't make economic sense.

Femtosecond laser patterning, by contrast, works in parallel. The laser scans across large areas, and the self-organizing physics creates patterns everywhere the laser touches. You can pattern centimeters in minutes, not hours.

The 1,000x speedup claim is based on this comparison:

Time to pattern 1 cm² area:

- Electron-beam lithography: 2-8 hours

- Femtosecond laser patterning: ~1-5 minutes

That's the difference between impractical (for production) and feasible. It's not just faster—it's a different category of manufacturing technique.

Throughput Economics

In semiconductor manufacturing, throughput is everything. Capital equipment is incredibly expensive—a state-of-the-art photolithography tool costs $100+ million. To justify that investment, the equipment must process hundreds or thousands of wafers monthly.

A fabrication technique that requires 8 hours per wafer limits your throughput to roughly 3 wafers per day per system. You'd need dozens of EBL tools running in parallel to achieve production capacity. That's massive capital investment and facility requirements.

Femtosecond laser systems, while not cheap, are more modular and scalable. A single system processing 100+ wafers per day becomes economically reasonable. You might need multiple systems for very large production volumes, but it's a fundamentally different economic proposition.

Scaling to Wafer-Level Production

Here's the beautiful part: the technique scales naturally. A laser that can pattern a 1 cm × 1 cm sample can pattern a 300mm wafer just as easily—you just let it scan longer. There's no fundamental obstacle. The uniformity and repeatability that work at small scales extend to full wafers.

This is radically different from many emerging nanofabrication techniques, which struggle to scale beyond laboratory samples. The fs-LIPSS process is inherently wafer-compatible, which dramatically increases the likelihood of actual production implementation.

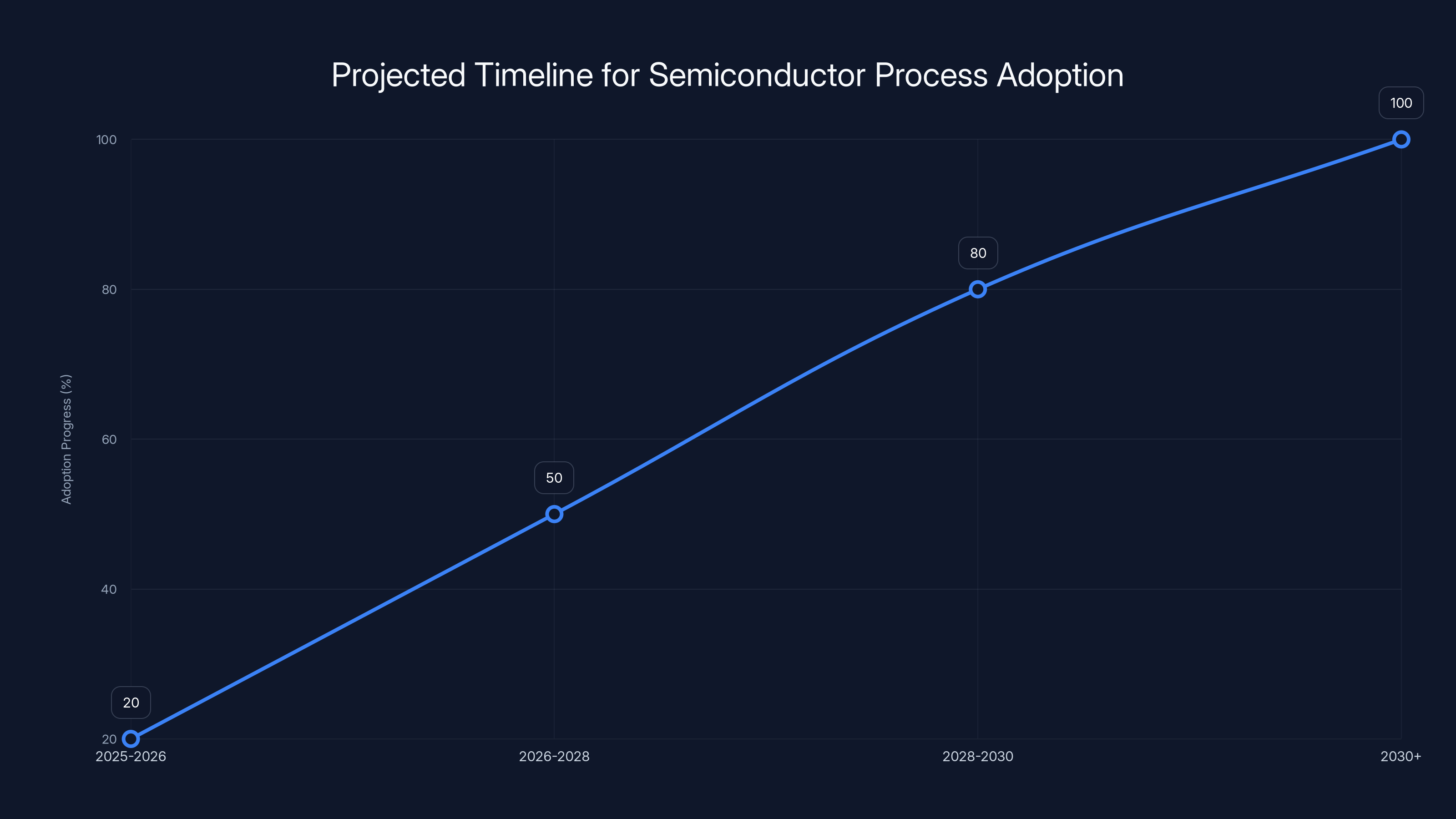

The adoption of new semiconductor processes is projected to progress from development in 2025-2026 to widespread adoption by 2030, following historical patterns. (Estimated data)

Material Science: Silicon, Silica, and Beyond

Why Silicon and Silica?

The research focuses on silicon and silicon dioxide (silica) because these are the dominant materials in semiconductor manufacturing. Silicon is the base material for CMOS chips. Silica appears in oxide layers, insulation, and thermal interface materials throughout chip architecture.

Both materials have well-understood thermal properties. Silicon conducts heat readily (which is useful for heat spreading), while silica conducts heat more slowly (useful for thermal isolation). By using fs-LIPSS to reduce thermal conductivity in selected regions, you can create engineered thermal networks within the chip.

Consider a typical processor:

- Heat is generated in the compute cores (transistor-dense regions)

- Heat spreads through intermediate layers toward the surface

- Heat finally exits to heatsinks and cooling systems

With fs-LIPSS patterning, you could:

- Keep some spreading layers thermally conductive (fast heat movement away from hot spots)

- Add fs-LIPSS patterning to other regions (slower heat movement, local thermal management)

- Create thermally isolated pockets for sensitive analog circuits

The ability to tailor thermal properties regionally opens up architectural possibilities previously impossible.

Extension to Other Materials

While the research focuses on silicon and silica, the physics applies to other semiconducting and dielectric materials:

- Gallium nitride (Ga N): High-power RF and power electronics

- Silicon carbide (Si C): High-temperature and high-power applications

- Gallium arsenide (Ga As): Photonic and RF applications

- Sapphire and other crystals: Various specialized applications

Anyone working with these materials faces the same phonon-limited heat transport. fs-LIPSS could potentially improve thermal management across a wide range of semiconductor technologies.

Thermal Property Tailoring: A New Design Paradigm

Historically, you choose a material and accept its thermal properties. Silicon has ~150 W/(m·K) thermal conductivity, period. You design around that.

fs-LIPSS changes this. Now you can pattern the material to modify its effective thermal conductivity. It's like having a slider: adjust the groove spacing and depth, change the thermal properties. Create regions with different thermal conductivity in the same material.

This opens up new thermal design possibilities:

- Thermal resistors: Nanostructured regions that intentionally slow heat flow

- Thermal conductors: Unpatterned regions or lightly patterned areas that spread heat quickly

- Thermal isolation: Creating pockets of low thermal conductivity around sensitive circuits

- Heat redistribution: Guiding heat flow to preferred dissipation paths

Instead of fighting your material's thermal properties, you engineer them.

Experimental Validation and Measurement Techniques

Thermoreflectance: Measuring Temperature Without Contact

Measuring thermal conductivity directly is tricky. You need to establish known temperature gradients, measure heat flow rate, and account for geometric factors. For nanoscale materials, this becomes especially difficult—contact thermometers add heat and distort measurements.

Thermoreflectance solves this elegantly. The technique exploits the fact that most materials' optical reflectivity changes slightly with temperature. By measuring reflectivity changes, you can infer temperature changes without touching the sample.

The method works like this:

- A laser heats a thin layer (the source)

- A second laser (pump-probe configuration) measures reflectivity of the region

- As heat spreads and dissipates, reflectivity changes temporally

- These changes reveal thermal diffusivity and conductivity

For the fs-LIPSS research, thermoreflectance provided real experimental confirmation that the nanostructured samples genuinely showed reduced thermal conductivity compared to controls. Not simulations, not theory—actual measurements on actual samples.

This experimental rigor is crucial. Any new materials or processes need measured data backing the claims, especially when proposing industrial adoption.

Numerical Simulation Insights

Simulations complement experiments. The research used numerical modeling to understand why thermal conductivity dropped. The simulations showed that the reduction comes primarily from restricted phonon mean free paths, not from chemical composition changes or unexpected side effects.

This is important because it validates the physical mechanism. If thermal conductivity dropped for mysterious reasons, you'd worry about stability or predictability. But if you understand the mechanism (phonon scattering from nanogrooves), you can predict behavior under different conditions and optimize the structure.

Simulations also enabled parameter exploration that would take months experimentally:

- How does groove spacing affect thermal conductivity?

- What depth is optimal for maximum effect?

- How does pattern orientation matter?

- How do edge effects and domain boundaries influence properties?

With computational models, researchers answer these questions before fabricating samples.

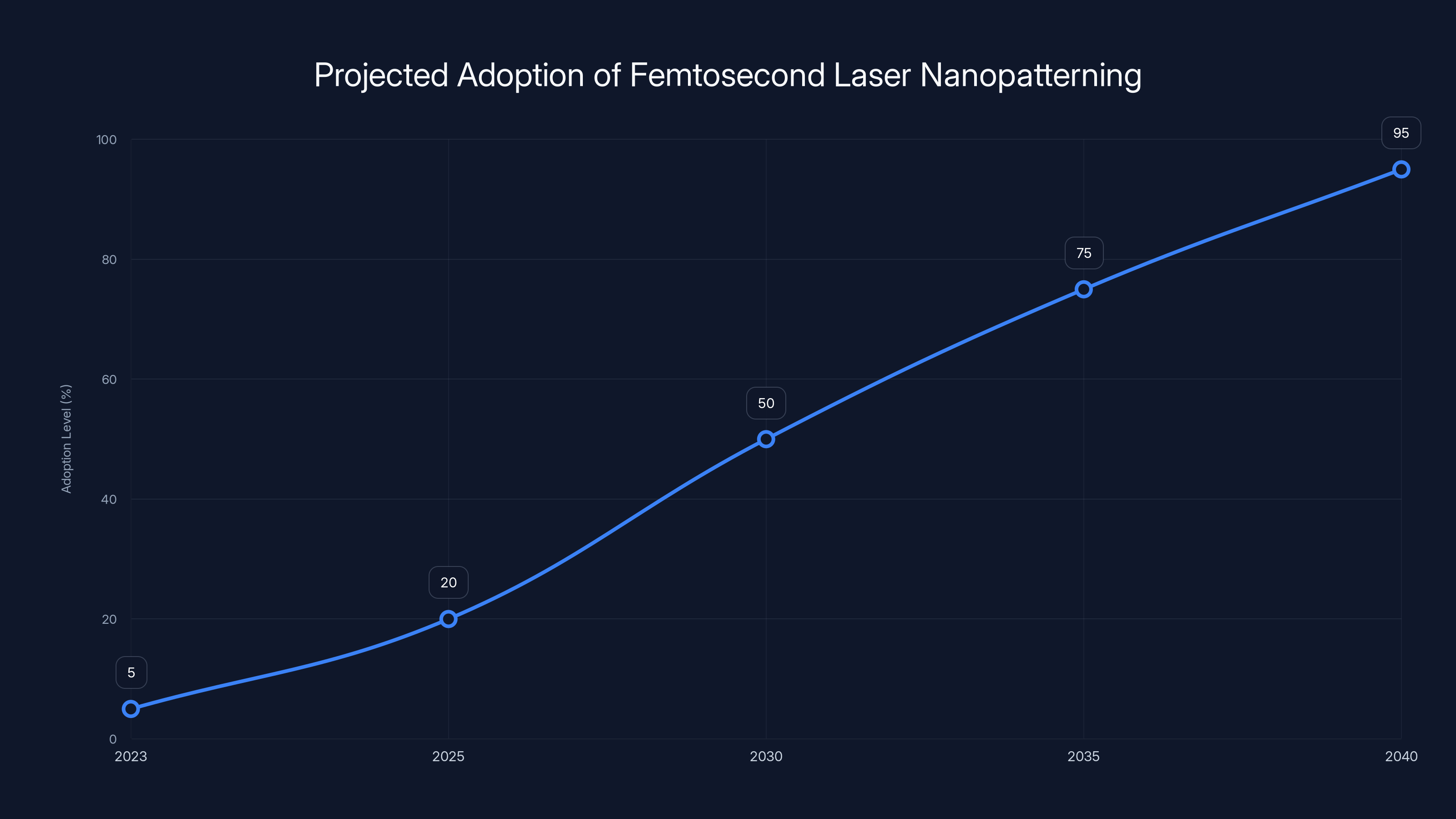

Estimated data suggests a gradual increase in the adoption of femtosecond laser nanopatterning, potentially becoming standard by 2040.

Industrial Challenges and Realistic Limitations

The Scalability Question

The lab demonstration is impressive. The question facing industry is starker: does this work at manufacturing scale, with manufacturing tolerances and yield requirements?

Femtosecond laser systems exist and are used industrially for some applications. But patterning semiconductor wafers at scale introduces challenges:

- Pattern uniformity across full wafers: Femtosecond lasers can create uniform patterns locally, but maintaining uniformity across 300mm wafers while scanning requires precise laser beam control and compensation

- Edge effects: Patterns at wafer edges might differ from center

- Batch vs. single-wafer processing: The research used single samples; production requires processing multiple wafers efficiently

- Defect tolerance: What happens if a small region gets incorrectly patterned? Does it significantly impact thermal performance?

None of these are showstoppers, but they're engineering challenges that require solving.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Adopting any new manufacturing process requires a compelling economic argument. Let's think through the costs:

Costs:

- Capital equipment: Femtosecond laser system with scanner and controls (~$5-15M)

- Maintenance and upgrades: Lasers require careful maintenance

- Integration with existing fabs: Engineering effort to add new process steps

- Training and qualification: Personnel need expertise with new equipment

- Validation and testing: Extensive qualification before production use

Benefits:

- Lower cooling power consumption (operational savings)

- Improved processor performance (higher clocks, higher yields)

- Reduced cooling infrastructure requirements

- Potential for new processor capabilities previously thermally limited

For a large semiconductor manufacturer producing millions of chips annually, the operational savings from reduced cooling power could easily justify the equipment investment. For a startup making thousands of chips, it might not.

This explains why adoption would likely begin with large volume manufacturers (Intel, TSMC, Samsung) before spreading to smaller players.

Reproducibility and Long-Term Stability

One lingering concern: how stable are these nanostructures over time? The research shows mechanical robustness, but do they degrade under real operating conditions?

Factors to investigate:

- Thermal cycling: Repeated heating and cooling from operation might cause crack initiation at groove boundaries

- Oxidation: Silicon can oxidize, potentially filling or modifying grooves

- Defect formation: Long-term operation might cause crystal defects to propagate from groove edges

- Moisture and contamination: Environmental factors that might affect surface structure stability

Answering these questions requires long-term testing—potentially years of operation before sufficient data exists for confident qualification. This testing would happen in parallel with manufacturing development, but it represents a validation hurdle before full-scale adoption.

Future Prospects: From Labs to Data Centers

Timeline to Commercial Deployment

Based on historical adoption patterns for new semiconductor processes, here's a realistic timeline:

2025-2026: Development and Optimization

- Universities and research institutes expand the technique

- Multiple research groups test on different materials and scales

- Industry evaluates applicability to specific chip designs

- Prototype systems built and tested

2026-2028: Integration and Qualification

- Leading semiconductor manufacturers license or develop in-house capability

- Process parameters optimized for production conditions

- Extensive qualification and reliability testing begins

- First pilot production runs on advanced processors

2028-2030: Early Commercial Implementation

- High-end processors (Nvidia's future GPUs, Intel's future CPUs, etc.) incorporate the technology

- Yield and reliability data accumulate

- Cost per unit decreases as manufacturing matures

- Supply chain develops to support equipment and materials

2030+: Widespread Adoption

- Becomes standard in high-performance computing

- Extends to mainstream processors as costs decrease

- Possibly appears in consumer devices handling demanding workloads

- Becomes business-as-usual thermal management, not novel technique

This isn't guaranteed, but it's consistent with how other process innovations have been adopted historically.

Competing and Complementary Technologies

fs-LIPSS isn't the only game in town for advanced thermal management. Other approaches are being pursued:

- Advanced cooling architectures: Direct-to-silicon liquid cooling, microchannel designs

- Thermal interface materials: New TIM compositions with better properties

- System-level thermal design: Chiplet architectures that separate hot and cool regions

- 3D packaging: Vertical stacking with better heat dissipation

These aren't competing—they're complementary. You'd likely see fs-LIPSS combined with advanced cooling architectures for maximum effect. The beauty of fs-LIPSS is that it's not a either/or decision. You use it in combination with other techniques to approach thermal limits more gradually.

Applications Beyond Semiconductors

While semiconductor applications are the focus here, fs-LIPSS thermal engineering could eventually appear in:

- Optics and photonics: Managing heat in high-power laser diodes and components

- Power electronics: Ga N and Si C devices for power conversion

- Thermoelectric devices: Engineering thermal properties in materials designed for energy conversion

- Advanced packaging: Thermal management in 3D heterogeneous integration

The underlying physics applies universally to any crystalline material where phonon scattering controls thermal transport.

Practical Implications for AI Workloads

Solving Real Data Center Problems

Large language models and AI training consume enormous computational resources. A single training run for a state-of-the-art model might involve thousands of GPUs running for weeks. The power consumption is staggering—sometimes megawatts for a single training job.

This power translates to heat. Managing that heat is a primary constraint. Data centers are built around cooling infrastructure. Some of the newest AI training facilities (like hyperscaler data centers in cooler climates) have been specifically located near cheap power and favorable cooling conditions.

fs-LIPSS thermal engineering could change this equation:

- Higher performance at same thermals: Instead of throttling clocks to stay within temperature limits, processors could maintain peak performance longer

- Same performance with less cooling: Alternatively, use reduced cooling infrastructure (lower cost, lower power) to achieve required performance

- Better efficiency: Lower cooling power overhead means better overall power efficiency for equivalent compute

For AI workloads running 24/7, even small efficiency improvements compound dramatically over operational lifetimes.

Quantum Machine Learning Possibilities

Quantum computing and machine learning are increasingly intersecting. Hybrid classical-quantum systems might leverage femtosecond-patterned heat management to reduce cooling burden on the classical infrastructure surrounding quantum processors.

This could enable larger, more practical quantum computers by reducing the cryogenic load. It's speculative, but thermally efficient classical systems supporting quantum processors is a genuine design problem researchers are tackling.

Key Research Insights and Mechanistic Understanding

Phonon Engineering as a Design Principle

At its core, this research demonstrates that phonon transport can be engineered through geometry. This is a paradigm shift. It suggests that materials science isn't just about discovering or synthesizing new materials—it's about architecting existing materials at nanoscales to achieve desired properties.

This principle could extend beyond thermal conductivity:

- Thermal expansion: Could engineered nanoscale structure reduce or control thermal expansion mismatch?

- Optical properties: Could similar structures modify photon transport (refraction, absorption)?

- Mechanical properties: Could groove patterns improve wear resistance or fatigue life?

- Electrical properties: Could nanoscale surface texturing affect carrier transport?

If the answer is yes to any of these, we're looking at a general methodology for property engineering, not just thermal management.

Self-Assembly and Natural Pattern Formation

One fascinating aspect of fs-LIPSS is that the patterns form somewhat spontaneously through physical processes, rather than being written deterministically like electron-beam lithography. The laser provides energy, and the material's own physics determines the final pattern.

This is closer to how nature grows structures—through thermodynamic optimization and self-organization. There might be lessons here for understanding how to design manufacturing processes that produce robust, optimized structures naturally rather than imposing arbitrary designs.

Conclusion: A Quieter, More Efficient Computing Future

The femtosecond laser nanopatterning technique described here addresses a fundamental problem that's only growing more acute: heat management in increasingly powerful computing devices.

Unlike band-aid solutions that cool more aggressively, this approach attacks the root cause. It modifies how heat moves through materials, preventing hot spots from forming in the first place. It's elegant physics, practical engineering, and economically sensible.

The technique checks almost every box for adoption:

✓ CMOS-compatible: Works with existing manufacturing ✓ Wafer-scalable: Extends from lab samples to production ✓ Measurable improvement: Real thermal conductivity reduction confirmed experimentally ✓ Speed advantage: 1,000x faster than alternatives ✓ Robust structures: Mechanically strong, durable ✓ Addressable market: AI, quantum computing, high-performance processors ✓ Cost-justified: Operational savings justify equipment investment

The remaining challenges are engineering in nature (scalability, uniformity, integration) rather than fundamental physics problems. These are exactly the kinds of problems semiconductor manufacturing excels at solving.

Within the next 5-10 years, we'll likely see this technology migrating from research labs to production fabs. By 2030, leading-edge processors might incorporate femtosecond-patterned thermal management as standard practice. By 2040, it could be as ordinary and expected as heat sinks are today.

This won't solve the heat problem entirely—compute density and power will keep growing, always pushing thermal limits. But it buys room. It enables more powerful chips that run more efficiently, consume less cooling power, and handle heat more gracefully.

That's worth paying attention to.

FAQ

What is femtosecond laser patterning and how does it differ from conventional nanofabrication?

Femtosecond laser patterning uses ultrafast light pulses lasting one billionth of a second (a femtosecond) to directly etch nanoscale patterns into material surfaces. Unlike electron-beam lithography, which writes patterns one pixel at a time over hours, femtosecond lasers create regular periodic structures naturally and uniformly across centimeter-sized areas in minutes. The ultrafast timescale enables non-thermal ablation—removing material through direct photon interaction rather than heat—resulting in minimal damage to surrounding material and precise nanometer-scale features.

How do phonons relate to thermal conductivity in semiconductors?

Phonons are quantized vibrations in the crystal lattice that carry thermal energy through solid materials. In semiconductors like silicon, phonons are the primary heat carriers (responsible for roughly 99% of heat transport in non-metallic materials). Thermal conductivity measures how quickly phonons move through the material. By creating nanoscale grooves that restrict how far phonons travel before scattering, you reduce the material's effective thermal conductivity. This prevents heat from spreading rapidly and keeps it more localized, reducing the buildup of hot spots.

What are the main advantages of fs-LIPSS thermal engineering for AI processors?

AI processors generate extreme heat density—500-600 watts concentrated in small areas. fs-LIPSS thermal engineering offers several advantages: it reduces thermal conductivity at the source, preventing hot spots from forming; it enables higher performance at the same temperature by distributing heat more evenly; it reduces cooling power requirements, improving overall system efficiency; and it's compatible with existing manufacturing processes, making adoption economically feasible for large-scale production. For data centers running continuous AI workloads, even small improvements in thermal efficiency translate to millions of dollars in operational savings.

Why is CMOS compatibility important for new semiconductor manufacturing techniques?

The semiconductor industry has spent decades optimizing CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor) manufacturing processes. Any new technique that disrupts this workflow faces significant barriers to adoption because it requires new equipment investment, personnel retraining, and extensive validation. fs-LIPSS is advantageous because it's maskless, resist-free, and compatible with standard CMOS workflows. It can be added as a patterning step without fundamentally redesigning the manufacturing process, dramatically increasing the likelihood of industrial adoption.

Can fs-LIPSS thermal engineering be applied to materials other than silicon and silica?

Yes, the underlying physics applies to any crystalline material where phonon-limited thermal transport dominates. Researchers have demonstrated or proposed applications in gallium nitride (Ga N), silicon carbide (Si C), gallium arsenide (Ga As), and various crystal substrates. Any semiconductor material where controlling heat flow is important—high-power devices, photonic components, quantum processors—could potentially benefit from femtosecond laser nanostructuring to engineer thermal properties.

What is the realistic timeline for commercial deployment of this technology in processors?

Based on historical semiconductor process adoption, expect: 2025-2026 for continued research and prototype development; 2026-2028 for integration and qualification at major semiconductor manufacturers; 2028-2030 for early commercial deployment in high-end processors; and 2030+ for widespread adoption becoming standard practice. The most likely scenario involves leading companies like Nvidia, Intel, and TSMC incorporating the technology first in advanced processors, with broader adoption following as equipment costs decrease and manufacturing matures.

How does femtosecond laser patterning compare to other thermal management approaches?

fs-LIPSS is complementary rather than competitive with other thermal solutions. It works at the material/device level to control fundamental heat transport, while other approaches (advanced cooling, thermal interface materials, system-level thermal design) work at higher levels. The most effective thermal management likely combines multiple approaches: fs-LIPSS to reduce heat generation and spreading, advanced cooling architectures to efficiently remove remaining heat, and intelligent system design to optimize thermal performance overall.

What measurements confirm that fs-LIPSS actually reduces thermal conductivity?

Researchers used thermoreflectance measurements, which work by observing how a material's optical reflectivity changes with temperature. By measuring reflectivity changes as heat spreads through patterned and unpatterned samples, scientists can directly quantify thermal diffusivity and conductivity. The technique provides real experimental data (not just simulation) confirming that nanostructured samples show measurably reduced thermal conductivity compared to controls. Numerical simulations further confirmed that this reduction comes from restricted phonon mean free paths rather than unexpected side effects.

What challenges remain before fs-LIPSS thermal engineering is ready for production?

Key challenges include: maintaining pattern uniformity across full 300mm wafers; understanding long-term stability under thermal cycling and real operating conditions; optimizing the process for integration with existing manufacturing workflows; validating reliability across extended operational lifetimes; and establishing cost-effectiveness at production volumes. These are primarily engineering challenges (materials, manufacturing, validation) rather than fundamental physics problems, suggesting they're solvable with focused development effort.

Could fs-LIPSS thermal engineering eventually appear in consumer devices?

Likely, but on an extended timeline. Initial adoption will focus on high-end devices where thermal limitations are severe and operational budgets are large (data center processors, specialized AI accelerators). As the technology matures and costs decrease, it could eventually extend to mainstream gaming GPUs, high-performance CPUs, and other devices handling demanding workloads. Consumer applications might emerge around 2035-2040 as the technology becomes business-as-usual rather than cutting-edge.

Key Takeaways

- Femtosecond lasers create nanoscale surface patterns that restrict phonon movement, reducing thermal conductivity by controlling heat transport at the source rather than fighting heat after it accumulates

- The technique is 1,000x faster than electron-beam lithography while producing 1,000x stronger structures, making it industrially viable for wafer-scale semiconductor manufacturing

- fs-LIPSS patterning is CMOS-compatible and maskless, integrating seamlessly with existing semiconductor manufacturing workflows without exotic equipment or process redesign

- Realistic commercial deployment timeline spans 2025-2030 for early adoption in high-end AI processors and data center chips, with widespread adoption potentially by 2035-2040

- Data center cooling consumes 5-20% of facility power, creating millions of dollars in annual operational savings for customers who deploy thermal efficiency improvements

Related Articles

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3: The Panther Lake Comeback Explained [2026]

- TSMC's AI Chip Demand 'Endless': What Record Earnings Mean for Tech [2025]

- Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Deal Reshapes Global Supply Chains [2025]

- Micron's AI Memory Pivot: What It Means for Consumers and PC Builders [2025]

- Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Investment: What It Means [2026]

- Best Computing Innovations at CES 2026 [2025]