Measles Brain Swelling: South Carolina Outbreak and Encephalitis Risk [2025]

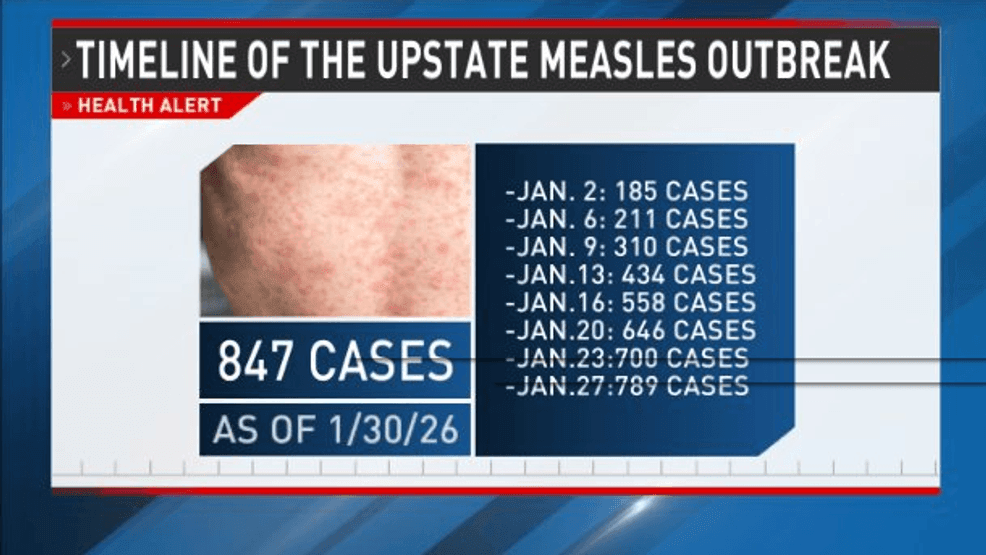

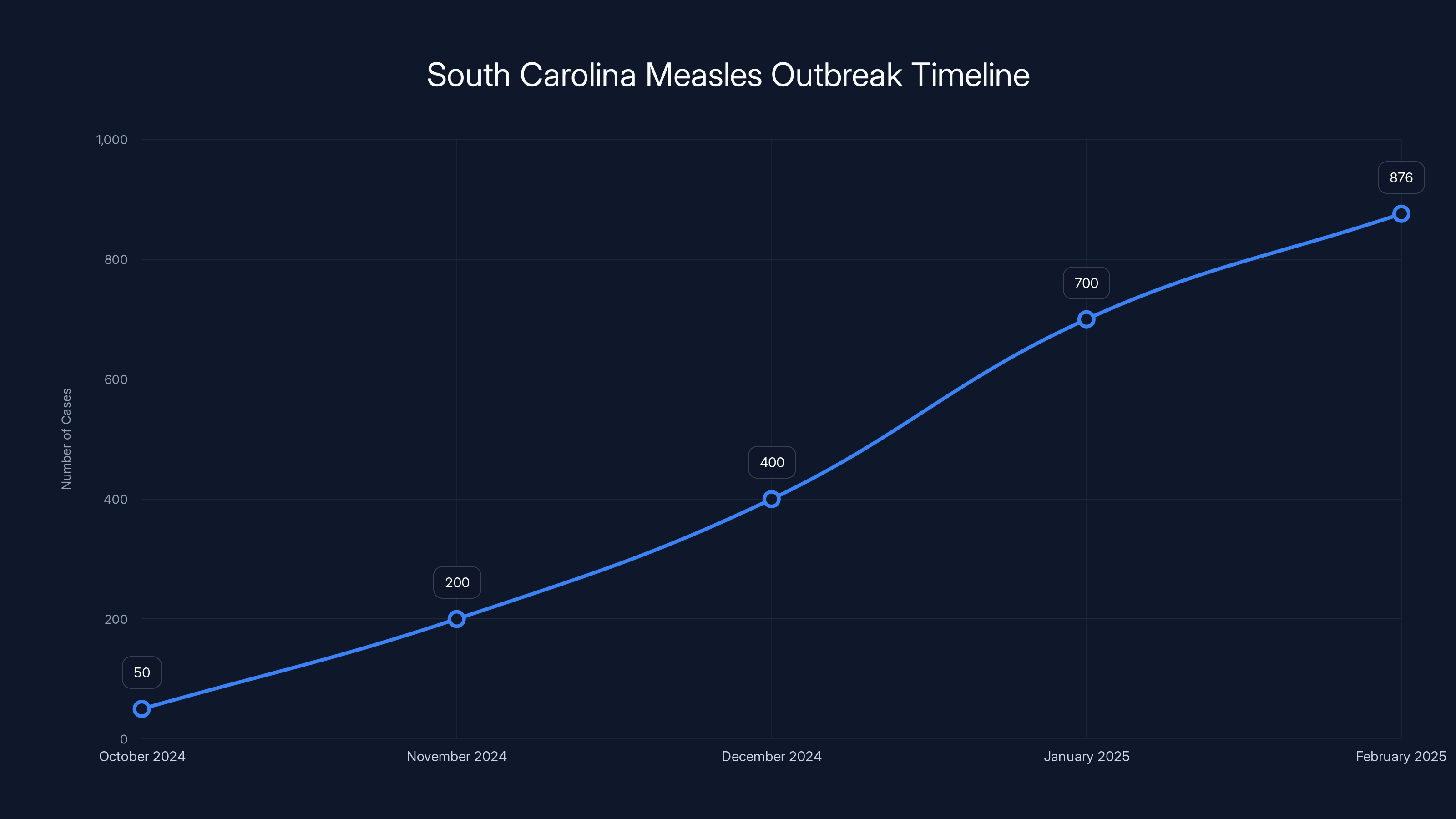

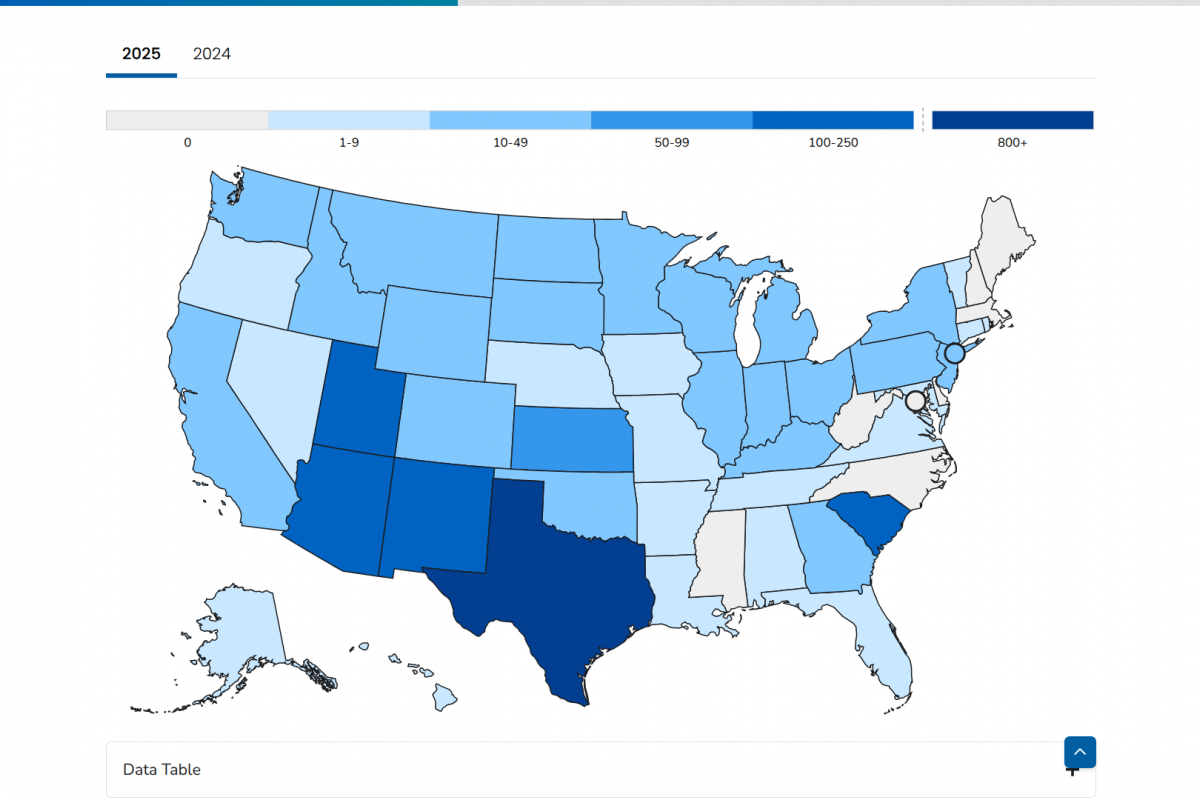

It started quietly in October. A handful of measles cases in Spartanburg County, South Carolina. Nothing alarming—at first. But by February, the numbers had exploded to 876 confirmed cases, with 700 arriving since January alone. That's not a coincidence. That's a public health crisis unfolding in real time.

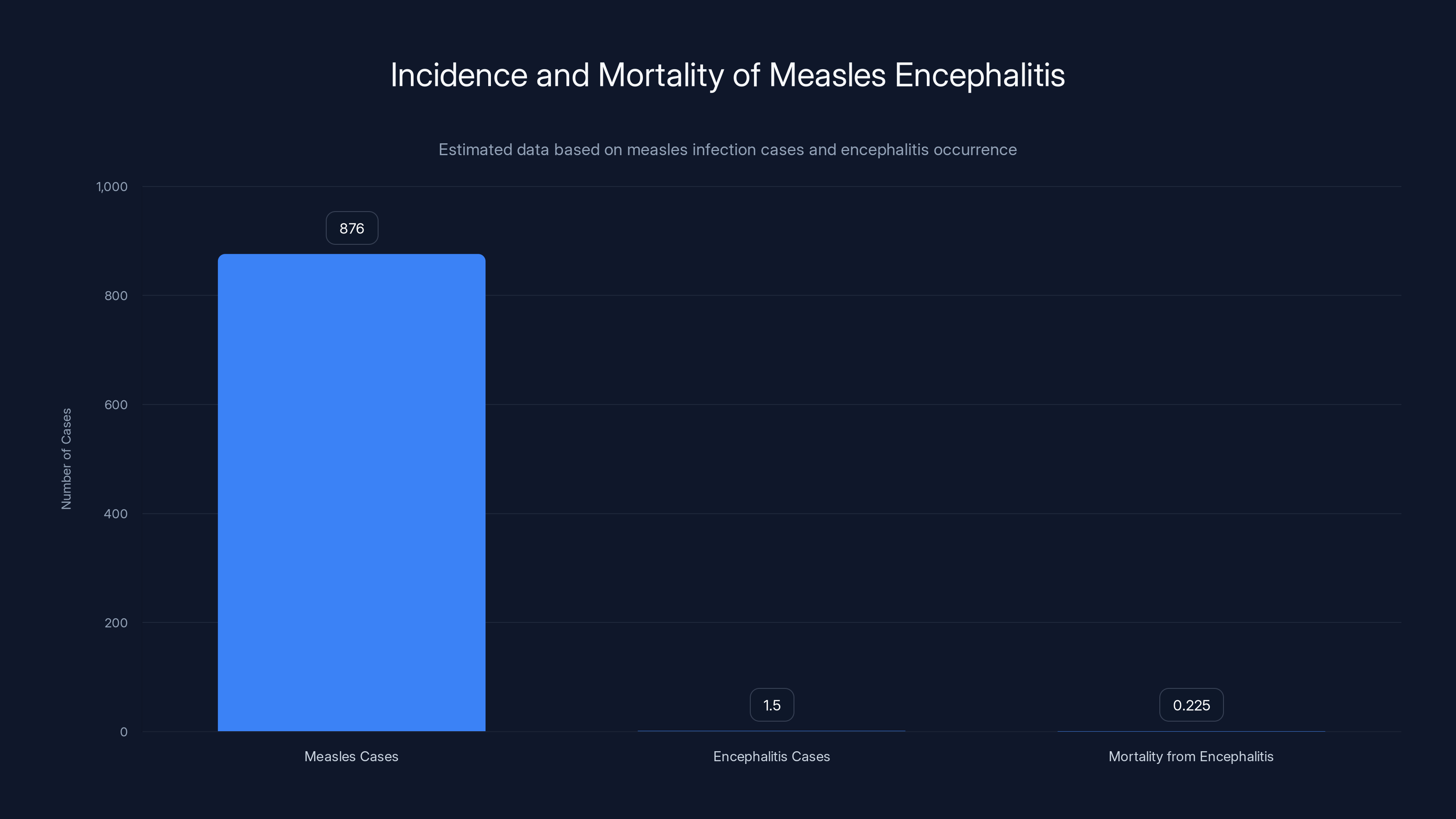

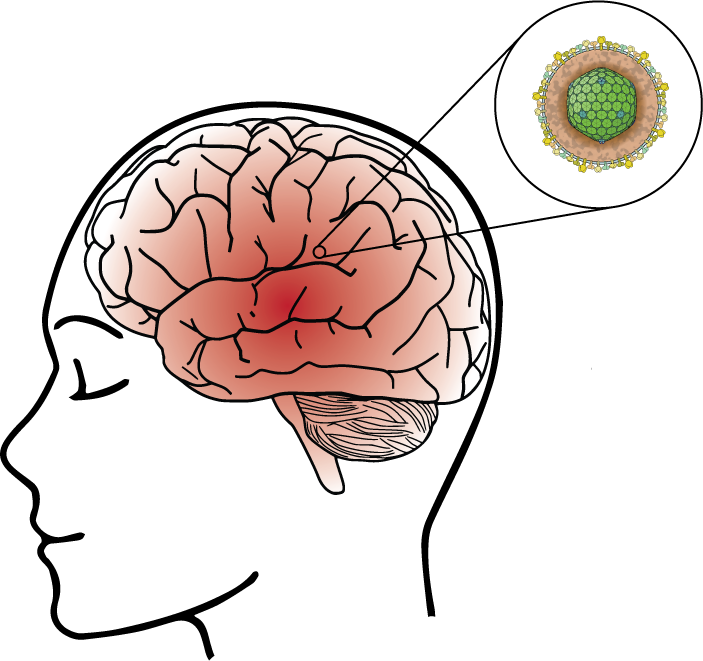

But the raw infection count doesn't tell the whole story. Some children aren't just getting sick with measles. They're experiencing something far worse: encephalitis, which is brain swelling caused by the virus itself or by the immune system's inflammatory response. State epidemiologist Linda Bell confirmed this during a media briefing, noting that inflammation of the brain carries risks of "developmental delay and impacts on the neurologic system that can be irreversible."

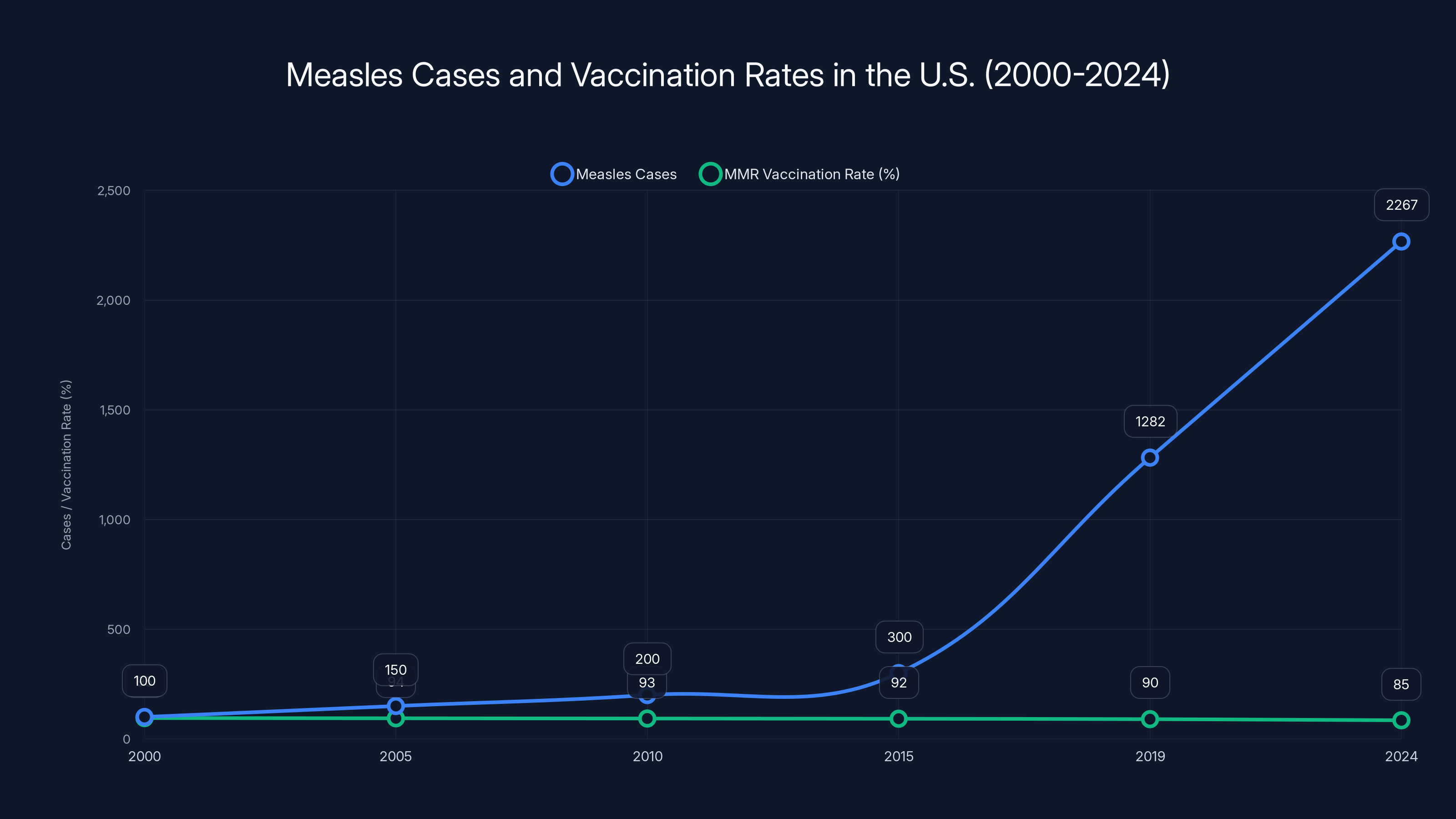

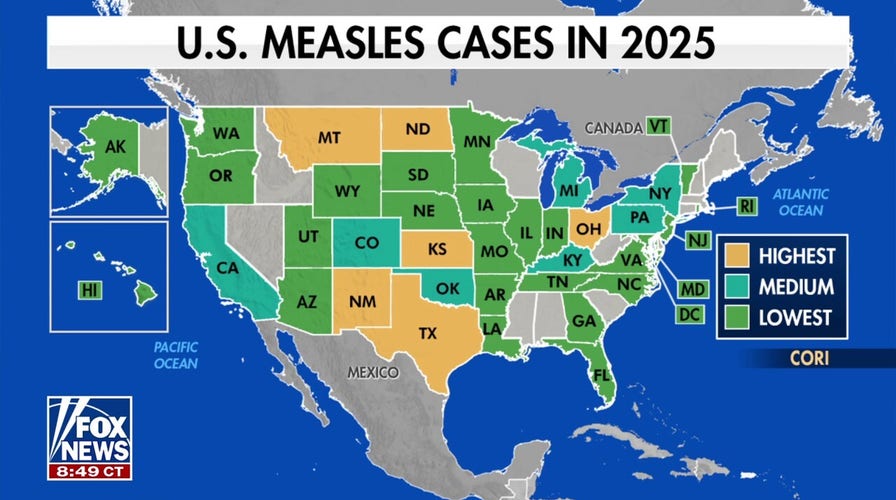

This outbreak reflects a troubling national trend. The United States recorded 2,267 measles cases in 2024—the highest number in 30 years. The reason? Declining vaccination rates across the country, driven by misinformation, access barriers, and what health officials describe as vaccine hesitancy at historically unprecedented levels.

The question isn't whether measles is returning. It's already here. The real question is whether we understand the true danger of what measles can do to a child's brain.

TL; DR

- South Carolina's measles outbreak has infected 876+ people as of February, with most cases arriving since January

- Encephalitis, or brain swelling, is a rare but severe measles complication affecting some children, with 10-15% mortality rates among those infected

- Declining vaccination rates are driving the resurgence, with 2024 seeing the highest US measles cases in 30 years

- Long-term neurological consequences of encephalitis can include seizures, hearing loss, intellectual disability, and developmental delays

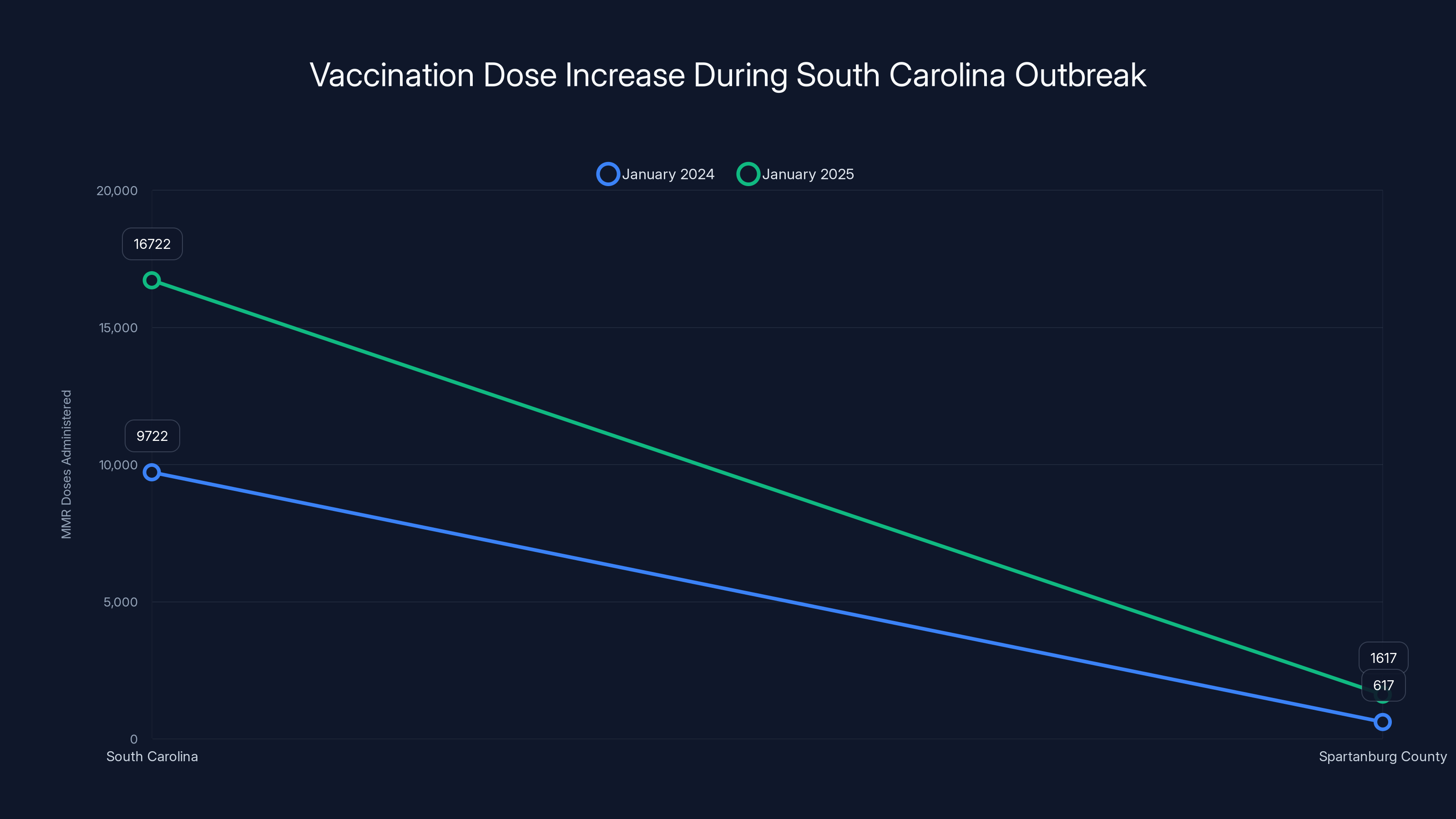

- The MMR vaccine remains the most effective prevention, with vaccinations in South Carolina jumping 72% in January 2024 compared to the previous year

The measles outbreak in South Carolina showed exponential growth, with cases rising from 50 in October 2024 to 876 by February 2025. Estimated data based on outbreak description.

Understanding the South Carolina Measles Outbreak

Measles doesn't spread like a rumor. It spreads like wildfire. The virus travels through respiratory droplets—when an infected person coughs or sneezes, it can hang in the air and infect anyone nearby within two hours after the person leaves the room. One infected person will infect 12-18 unvaccinated people in a population with no immunity. That's not typical contagion. That's exponential growth.

The South Carolina outbreak began modestly in October, but the trajectory accelerated sharply. By January 2025, cases were arriving faster than contact tracing could contain them. Healthcare workers were overwhelmed. Schools were dealing with closures or sending letters home warning parents about exposures. Communities were fractured into the vaccinated and the vulnerable.

Spartanburg County became the epicenter. This isn't random geography. Spartanburg has experienced documented clusters of vaccine-hesitant communities. Educational outreach efforts have struggled to reach resistant populations. Public health officials noted that vaccination rates in certain pockets of the county lag significantly behind state and national averages.

What makes this outbreak particularly concerning is that it's not isolated to one demographic or age group. Cases span infants too young to be vaccinated, children in schools, teenagers, and adults. Some cases emerged in healthcare settings where medical workers interacted with infected patients. This broad distribution means the outbreak has penetrated multiple community layers simultaneously.

The timeline matters. February's case count of 876 represents explosive growth in just a few months. Compare that to typical measles outbreaks in recent US history, which averaged dozens or low hundreds of cases before vaccination campaigns halted transmission. The speed and scale here suggest underlying population-level immunity gaps that haven't existed in decades.

Out of 876 measles cases, approximately 1.5 cases result in encephalitis, with a mortality rate of 10-15%, leading to around 0.225 deaths. Estimated data based on provided statistics.

What Is Encephalitis and Why Does It Matter

Encephalitis sounds medical. Abstract. But what it really means is that the brain is swelling from inflammation. Picture your brain inside your skull with nowhere to expand. When the tissue inflames, pressure builds. The consequences cascade from there.

Measles encephalitis occurs in roughly one to two per thousand measles cases. That might sound rare, but when you're dealing with 876 infections, even a small percentage becomes dozens of children hospitalized with brain inflammation. And it's not a statistic to the parents sitting in a pediatric ICU watching their child seize.

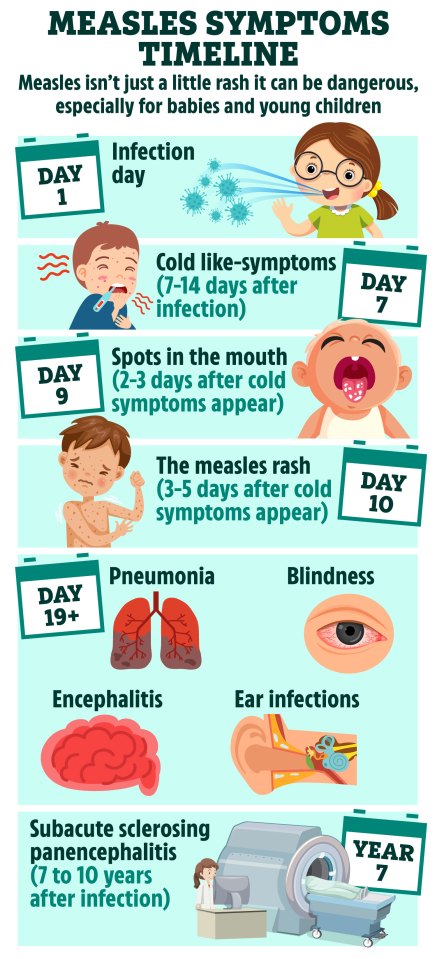

There are actually two mechanisms by which measles causes encephalitis. The first is acute encephalitis, which happens when the measles virus directly invades brain tissue and triggers inflammation. This typically occurs within 7-10 days of the measles rash appearing. The second is post-infectious encephalitis, which develops when the immune system overreacts to the virus, causing inflammatory damage to the brain. This usually emerges within 30 days of initial infection.

The symptoms are unmistakable once they arrive. Children experience seizures, high fever, severe headache, confusion, lethargy, or loss of consciousness. Some develop stiffness in the neck. Others become irritable or suffer photophobia (extreme light sensitivity). A parent notices their child isn't responding normally, or they wake to find their child convulsing, and they rush to the emergency department.

The mortality rate among children who develop measles encephalitis is 10-15%. That means one in six to one in ten children diagnosed with this complication will die from it, despite modern intensive care. Those who survive often face permanent consequences. The inflammation damages neural tissue in ways that don't always repair.

Long-term sequelae include intellectual disability, developmental delays, learning disabilities, behavioral problems, and seizure disorders that persist for years. Some children regain full neurological function. Others don't. The outcome depends on severity of inflammation, how quickly treatment begins, and individual variation in how each child's brain heals.

State officials confirmed that several children in South Carolina have developed encephalitis, though the exact number hasn't been publicly disclosed. This lack of transparency reflects a limitation in public health data collection. Measles cases must be reported to the South Carolina Department of Public Health, but hospitalizations and specific complications like encephalitis aren't mandated for reporting. So the true prevalence remains unknown.

The Acute Phase: Recognition and Symptoms

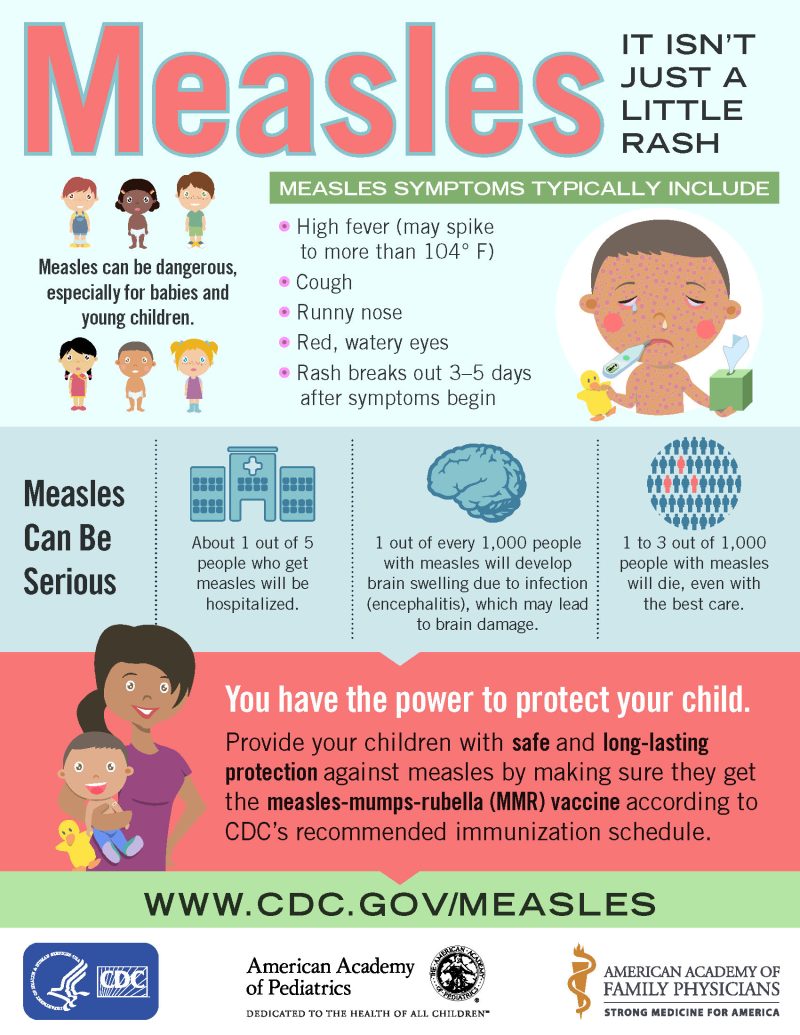

Measles itself has distinctive presentation. Children develop fever, cough, runny nose, and conjunctivitis (red, watery eyes) days before the characteristic rash appears. When the rash does arrive, it starts on the face and hairline, then spreads downward across the body over several days. The rash consists of small red bumps that blanch when pressed.

But before the rash or concurrent with it, some children take a turn for the worse. Instead of gradual recovery, they spike fever. They become lethargic. They stop responding normally to their parents. They develop headache severe enough to make them cry. These are warning signs that encephalitis is developing.

Recognition matters urgently. The earlier treatment begins, the better the neurological outcomes. Parents who notice these symptoms need to seek immediate medical evaluation. Pediatricians need to maintain a high index of suspicion during measles outbreaks. Emergency departments need protocols in place to rapidly assess altered mental status or seizure activity in children with confirmed or suspected measles.

Diagnosis typically involves lumbar puncture, where cerebrospinal fluid is sampled and tested for inflammatory markers and viral RNA. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows brain swelling and inflammation patterns. Electroencephalography (EEG) detects seizure activity. These tests confirm inflammation and guide treatment decisions.

Treatment is largely supportive. There's no specific antiviral that eliminates measles virus from the brain. Instead, management focuses on managing seizures, maintaining airway and oxygenation, controlling fever, and supporting the child through the inflammatory phase while their immune system fights the infection. Some severe cases require immunoglobulin therapy or other interventions to modulate inflammation, but evidence for these approaches is limited.

The intensive care setting becomes home for weeks. Children require mechanical ventilation if they're unable to protect their airway. They need continuous seizure monitoring. Medications to prevent seizures. Careful fluid management. Physical therapy as they recover. The emotional toll on families is immense.

Measles cases in the U.S. have increased significantly since 2000, correlating with a decline in MMR vaccination rates. Estimated data shows a concerning trend of rising cases as vaccination rates fall.

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis: The Delayed Threat

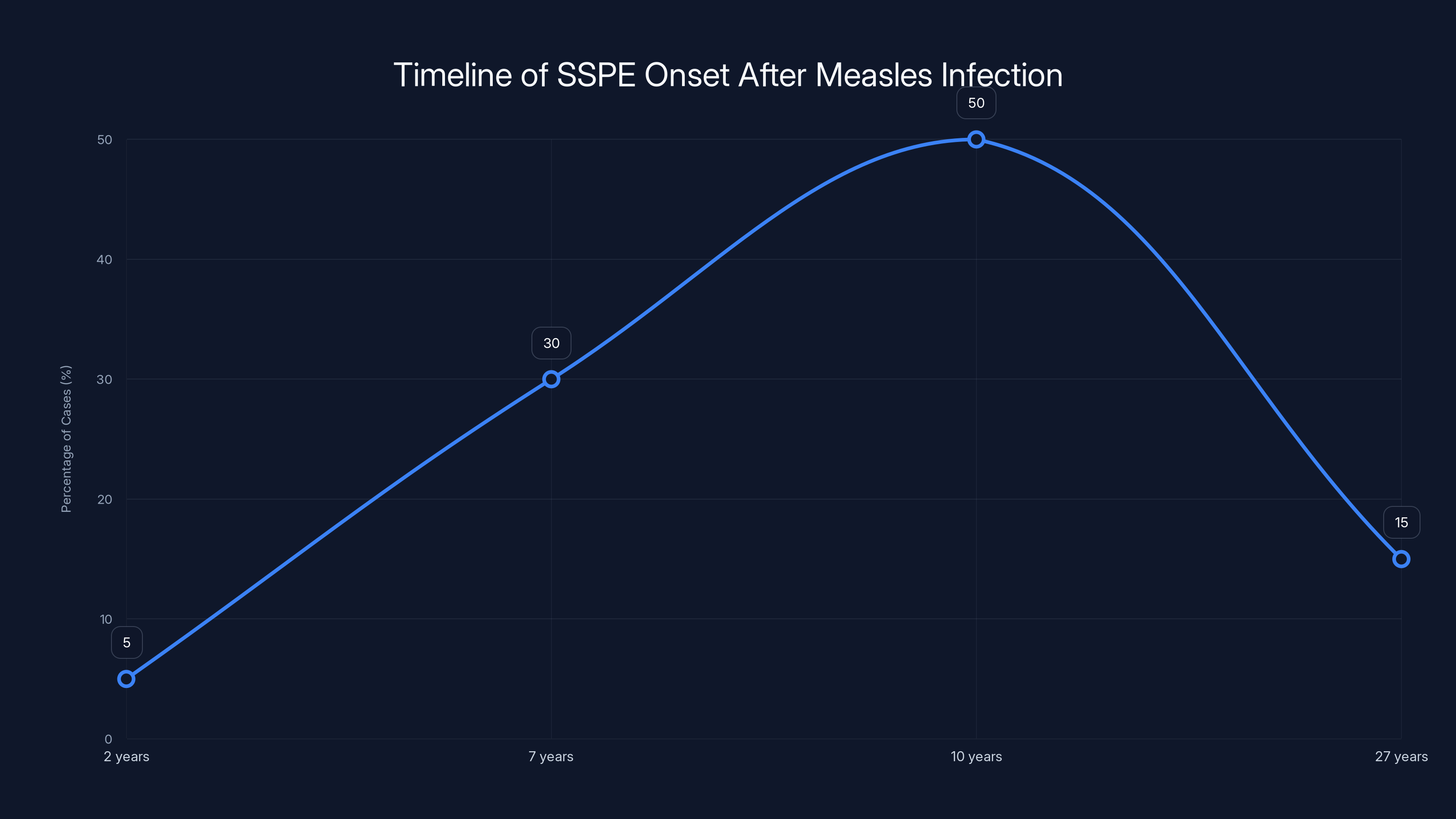

If acute encephalitis is the immediate crisis, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is the delayed nightmare that can emerge years after initial recovery.

SSPE is a progressive, degenerative brain disease caused by persistent measles virus in the central nervous system. After a child appears to recover from measles completely, the virus remains dormant in brain tissue. Then, sometimes years later, the virus mutates or the immune system's control weakens, and the virus reactivates. When it does, it triggers a cascade of inflammation that gradually destroys brain tissue.

The condition typically appears 7-10 years after initial measles infection, though cases have emerged as early as two years and as late as 27 years after infection. Early symptoms are subtle: personality changes, declining school performance, irritability, poor concentration. Parents notice their child isn't quite themselves, but assume it's adolescence or a phase.

Then the disease progresses. Seizures emerge. Myoclonic jerks (involuntary muscle movements) become frequent. Movement becomes uncoordinated. Cognition deteriorates. Eventually, the child enters a vegetative state. SSPE is progressive, relentless, and fatal. Most children die within months to years of symptom onset.

Incidence of SSPE is estimated at two per 10,000 people who acquire measles. That sounds low until you realize that one person developing SSPE is one too many. In September 2024, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health reported the death of a school-age child due to SSPE. This child was infected with measles as an infant, before they were old enough for MMR vaccination. For years, they seemed fine. Then SSPE emerged and killed them.

This case illustrates a critical point: measles isn't a one-time infection with one-time consequences. The virus establishes a relationship with the nervous system that can last a lifetime.

The mechanism of SSPE involves altered measles virus that persists in neurons. The immune system can't clear it completely. Gradual accumulation of viral replication within brain tissue causes inflammation and neurodegeneration. Some hypotheses suggest that immune pressure selects for defective viruses that escape recognition but still cause damage. Others propose that the virus integrates into the neuronal genome itself.

Risk factors for SSPE include infection before age two and possibly immunocompromised individuals. Children infected in infancy have higher SSPE risk than those infected after age five. This reflects the developing brain's unique vulnerability to persistent viral infection.

No treatment exists for SSPE. Antivirals have been tried without success. Immunomodulatory therapies have been explored. Some experimental approaches using interferon showed marginal effects in individual cases, but no standardized, effective therapy exists. Prevention through vaccination is the only approach that works.

The tragedy of SSPE in the modern era is that it's completely preventable. The child in Los Angeles who died would be alive if they'd been vaccinated after 12 months of age. The cases that will inevitably emerge from the South Carolina outbreak could all be prevented.

National Measles Trends and Vaccination Decline

Measles elimination in the United States felt like a public health victory. The disease was declared eliminated in 2000 after decades of vaccination campaigns. For years, cases remained sporadic and mostly imported from other countries. Americans could breathe easy. Measles belonged to history.

Then everything changed. Case numbers began creeping upward. 2019 saw 1,282 cases. That seemed alarming at the time. By 2024, we'd surpassed that with 2,267 cases—the highest total in 30 years. The trajectory is climbing. The trend is unmistakable. Measles is returning to America.

The cause is clear: declining vaccination rates. The MMR vaccine provides 95-98% protection against measles when both doses are administered. It's been available since 1971. Yet vaccination coverage has fallen in pockets across the country. Some communities have MMR vaccination rates below 85%. Others below 80%. In clusters, rates drop to 50% or lower.

Why? The causes are complex. Some vaccination hesitancy stems from misinformation about vaccine safety, particularly the thoroughly debunked and retracted Wakefield study from 1998, which falsely linked MMR to autism. That study was fraudulent. The data was fabricated. The author lost his medical license. Yet the damage persists in cultural memory. Some communities remain convinced vaccines cause autism despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Other barriers are more practical. Rural communities may lack easy access to vaccination services. Uninsured or underinsured families may struggle to afford vaccines, even though they're federally recommended for free. Distrust of medical institutions runs deep in some communities, reflecting historical trauma from medical racism and unethical research practices. These barriers are real and require genuine solutions.

Philosophical and religious objections to vaccination also contribute. Some religious traditions practice limited medical intervention. Some families hold libertarian views opposing government health mandates. These beliefs are sincere, even if the public health consequences are severe.

What's accelerated the decline is social media. Vaccine hesitancy groups have organized online, creating echo chambers where misinformation spreads unchallenged. Stories of supposed vaccine injuries circulate without medical context or verification. Conspiracy theories flourish. Algorithm-driven social platforms amplify polarizing content over accurate information. The result is a population increasingly skeptical of vaccination despite historical evidence of vaccine safety and effectiveness.

The outbreak in South Carolina reflects these broader dynamics. The region has communities with concentrated vaccine hesitancy. Public health messaging hasn't penetrated effectively. Trust in health institutions is low. Meanwhile, an index case arrived and sparked rapid transmission through the vulnerable population.

SSPE typically appears 7-10 years after measles infection, with some cases as early as 2 years and as late as 27 years. Estimated data.

Hospitalization Patterns and Healthcare Impact

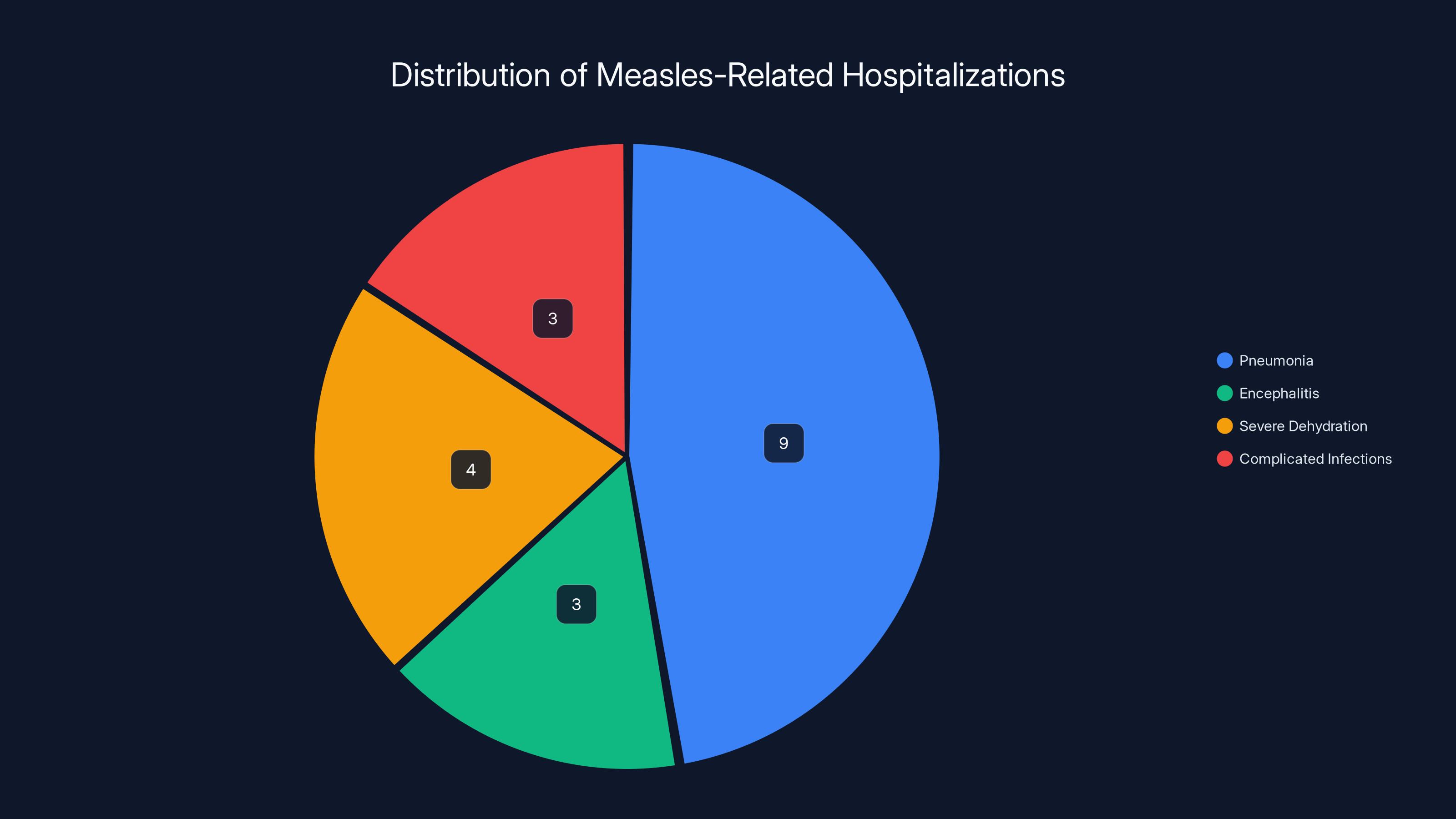

Measles hospitalizations are increasing alongside case counts. South Carolina officials confirmed 19 measles-related hospitalizations, including cases with secondary pneumonia. This might sound low relative to 876 cases, but it reflects severe disease. Not every child with measles requires hospitalization. Only the most seriously ill do.

Pneumonia is the leading cause of death in children with measles, occurring in approximately one in 20 infected children. When measles damages the respiratory tract's lining, secondary bacterial infection often follows. Children develop worsening respiratory symptoms, hypoxemia, and respiratory failure requiring ICU care.

Other children require hospitalization for encephalitis management, severe dehydration, or complicated secondary infections. The hospitalization infrastructure in a region experiences strain. Pediatric beds fill. ICU capacity becomes constrained. Staff resources are stretched. This affects not just measles patients but the entire hospital's capacity to care for other emergencies.

Healthcare workers face occupational exposure risk. Measles is highly infectious in healthcare settings. Even brief exposure to an infected patient can transmit the virus. Healthcare workers must be fully vaccinated against measles to be protected. Some older healthcare workers received only one dose of MMR decades ago. They may require revaccination. Unvaccinated healthcare workers potentially expose vulnerable hospital patients to measles. This creates a secondary outbreak risk within hospitals themselves.

The economic burden extends beyond hospitalization costs. Outpatient visits increase for diagnosis, follow-up, and complications. Antibiotics and supportive medications increase. Imaging and laboratory testing multiply costs. Then there's the indirect cost: lost work by parents caring for sick children, reduced productivity during recovery periods, and potential permanent disability costs if encephalitis leaves a child with lasting neurological damage.

A single case of measles with encephalitis and permanent neurological sequelae can cost $1-2 million or more across the child's lifetime when accounting for special education, ongoing medical care, and lost earning potential. Multiply that across dozens of cases from this outbreak, and the economic burden becomes staggering.

Healthcare systems in affected regions are responding. Hospital protocols for measles isolation have been activated. PPE supplies for respiratory protection are being allocated. Staff have received education on recognizing measles complications. But reactive response is always more expensive and disruptive than prevention through vaccination.

Vulnerable Populations and Risk Stratification

Not every child faces equal risk from measles. Several factors influence who's most likely to develop severe disease and complications like encephalitis.

Infants under 12 months of age face the highest hospitalization risk. Their immune systems are immature. They haven't completed primary vaccination schedules yet. MMR vaccine isn't given until 12-15 months. If they're exposed before that age, they lack vaccine protection and their natural immunity is insufficient. Severe measles in infants can lead to pneumonia, encephalitis, and death.

Children under five years old more frequently develop respiratory complications. Their smaller airways are more vulnerable to inflammation. Secondary bacterial pneumonia affects them more commonly. Encephalitis rates are higher in younger children.

Immunocompromised children face severe risk. These include children with leukemia or other cancers, HIV-infected children with low CD4 counts, children on immunosuppressive medications for organ transplants, and children with primary immunodeficiencies. Their immune systems can't effectively control measles virus replication. These children can develop progressive giant cell pneumonia, a severe and often fatal complication where infected cells fuse and create multi-nucleated giant cells that cause massive inflammation in the lungs.

Pregnant women exposed to measles face risks of preterm labor, miscarriage, and vertical transmission to the fetus. Infant infection in utero can lead to congenital measles or congenital rubella-like syndrome if rubella co-infection occurs. Several South Carolina pregnant women exposed to the outbreak required immune globulin administration, a concentrated antibody product that provides temporary passive immunity. This prevented measles infection but also meant they couldn't receive MMR vaccine during pregnancy (live vaccine is contraindicated in pregnancy).

Vitamin A deficiency is a significant risk factor in developing countries. While less common in the United States, it still affects some populations with malnutrition. Vitamin A supplementation reduces measles severity and complications. Public health authorities recommend vitamin A supplementation for all hospitalized children with measles regardless of nutritional status, given the protective benefit.

Risk stratification helps target interventions. Children in high-risk groups should be prioritized for vaccination before outbreak exposure. Those exposed in high-risk categories should be considered for immune globulin to prevent infection. Close monitoring for complications should be established for high-risk children who do develop measles.

The outbreak's impact on these vulnerable populations compounds existing health disparities. Uninsured children face barriers to vaccination and follow-up care. Rural children have limited access to pediatric specialists for managing complications. Children from low-income families are more likely to have nutritional deficiencies that increase measles severity. The outbreak doesn't affect all communities equally.

Pneumonia accounts for nearly half of measles-related hospitalizations in South Carolina, highlighting its severity as a complication. Estimated data based on typical distribution.

Vaccination Response and Public Health Intervention

When the South Carolina outbreak accelerated, public health responded. Vaccination campaigns were mobilized. Healthcare providers were engaged. Community outreach expanded.

The results are measurable. In January 2025, South Carolina administered over 7,000 additional MMR doses compared to January 2024. That's a 72% increase. In Spartanburg County specifically, the epicenter, over 1,000 additional doses were given, representing a 162% increase. These numbers reflect genuine public health effort to rapidly raise population immunity.

This is exactly what should happen during an outbreak. Public health moves into crisis mode. Vaccination becomes accessible. Community partners distribute information. Healthcare providers strongly recommend vaccination. Parents see cases in their community and recognize the threat. Vaccination numbers spike.

But here's the fundamental problem: it shouldn't require an outbreak and dozens of hospitalized children to achieve these vaccination rates. These rates should be baseline, sustained across time through routine practice and consistent messaging.

After-the-fact vaccination campaigns are valuable but limited. They reach populations already convinced enough to seek vaccination. They don't reach the most resistant communities. They don't address underlying hesitancy. Once the outbreak wanes and media attention fades, vaccination rates typically drop again. The window of opportunity closes. Communities return to baseline vaccination coverage.

Sustained prevention requires different approaches. Building trust in medical institutions. Community education programs. Healthcare provider relationships with families. Addressing misinformation through trusted community leaders, not government mandates. Removing access barriers. Making vaccination convenient and accessible.

Some regions have successfully maintained high vaccination coverage. Vermont, Massachusetts, and other states with strong vaccination cultures have sustained MMR coverage above 95% despite national trends. These regions accomplished this through dedicated effort over years. Public health investment. Healthcare provider engagement. Community relationships.

School immunization requirements have historically been one of the most effective vaccination levers. States with strong school immunization laws achieve higher coverage. But several states have weakened these requirements, allowing broader philosophical exemptions. Without enforcement mechanisms, requirements become suggestions.

Public health agencies are deploying multiple strategies. Providing free vaccines at mobile clinics. Engaging pediatricians and family medicine physicians. Working with maternal-child health programs. Distributing materials through schools and community organizations. Hosting town halls to address concerns and share accurate information.

These efforts take time to scale. They require resources. They require coordination across agencies. But they're essential for breaking the cycle where outbreaks spike vaccination rates, then complacency returns and coverage drops until the next outbreak arrives.

Neurological Complications Beyond Encephalitis

Brain swelling captures attention, but measles causes other neurological complications. Febrile seizures are common with high measles fever. These seizures are frightening for parents but typically don't cause permanent harm. Non-febrile seizures can also occur, reflecting the virus's direct effects on the nervous system.

Transverse myelitis occasionally develops, causing inflammation of the spinal cord and resulting in weakness or paralysis. Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported post-measles, an autoimmune condition causing ascending paralysis that can require mechanical ventilation.

Measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE) is a rare but severe complication in immunocompromised patients. It involves persistent measles virus infection of the brain with progressive neurological deterioration. Unlike typical measles encephalitis which is inflammation-driven, MIBE is driven by ongoing viral replication. It's usually fatal.

These complications extend beyond the brain itself. The neurological system's complexity means viral infection can affect multiple structures. Hearing loss occurs in some measles cases, ranging from temporary to permanent. Blindness from corneal scarring occurred historically in vitamin A-deficient populations.

The respiratory system faces direct viral injury. Measles causes laryngotracheobronchitis, inflammation of the airways. In severe cases, the airway swells enough to compromise breathing. Croup symptoms develop: barky cough and stridor.

Immune suppression following measles can last weeks. Children develop temporary reduced immunity to other infections. This is called immune amnesia or immune system reset. Prior immunity to other vaccines may be temporarily reduced. Children become vulnerable to superinfection with other viruses and bacteria.

Gastrointestinal complications include severe diarrhea and abdominal pain, occasionally with appendicitis or bowel obstruction. Hepatitis with elevated liver enzymes occurs in some cases. These complications usually resolve without specific treatment but can cause severe dehydration requiring IV fluids.

The multi-system nature of measles explains why it's not a benign childhood disease. It's a systemic viral infection that can damage nearly every organ. Modern supportive care has reduced mortality compared to the pre-vaccine era, but complications remain serious and sometimes permanent.

During the South Carolina outbreak, MMR vaccinations increased by 72% statewide and 162% in Spartanburg County, highlighting effective public health intervention.

Pregnancy and Vertical Transmission Risks

Measles in pregnancy carries specific hazards that require careful management. Pregnant women exposed to measles face several risks: increased severity of measles disease itself, premature labor, spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), and potential fetal infection.

Measles severity increases in pregnant women. Pregnancy-related immunological changes (immune tolerance necessary to accept the fetus) paradoxically increase susceptibility to certain infections. Respiratory complications are more frequent. Pneumonia occurs more commonly than in non-pregnant infected women. Hospitalization rates are higher.

Measles in the first trimester carries particular risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. The developing fetus is vulnerable to direct viral infection. If fetal infection occurs, particularly in early pregnancy, congenital anomalies may result. Fetal loss is a documented risk.

Infants born to mothers with active measles around delivery are at risk of neonatal measles. The infant acquires infection either in utero or through respiratory exposure at birth. Neonatal measles can be severe, occurring in a newborn whose immune system is completely immature.

This is why several South Carolina pregnant women who were exposed to measles received immune globulin (IG). This is a concentrated preparation of antibodies from plasma donors. When given within 72 hours of exposure to an unvaccinated or not-fully-vaccinated pregnant woman, IG can prevent measles infection. It's a temporary, passive immunity solution.

The complication is that pregnant women can't receive MMR vaccine because it's a live vaccine and carries a theoretical (never documented) risk of fetal infection. So if they're exposed during pregnancy and not previously vaccinated, they're stuck. They can take IG for prevention if exposed. They can accept measles infection and endure it. But they can't be vaccinated during pregnancy.

The solution is preconception vaccination. Women of childbearing age should ensure they have two MMR doses before pregnancy. If they're unsure of prior vaccination, serologic testing can confirm immunity. If non-immune, vaccination before pregnancy offers full protection during pregnancy and any subsequent pregnancies.

Healthcare providers should proactively counsel patients about measles vaccination during preconception care. This prevents exposure and complications during pregnancy.

Immunity, Vaccination Schedules, and Protection

The MMR vaccine has one of the highest efficacy rates of any vaccine. A single dose is 93% effective at preventing measles. Two doses are 97% effective. This means that even in outbreak situations with many infected people, vaccinated individuals have very high probability of avoiding infection.

The vaccine schedule recommends the first dose at 12-15 months of age and the second dose at 4-6 years of age. This timing allows adequate immune response to develop while vaccinating before school entry and major outbreak risk.

For outbreak situations or high-risk exposures, accelerated schedules are possible. The second dose can be given as soon as 28 days after the first dose if rapid protection is needed. Healthcare providers can adjust scheduling based on outbreak epidemiology.

Some people born before 1957 have lifelong immunity from natural measles infection, which was nearly universal before vaccination. People born from 1957 onward typically need vaccine-based immunity. People born before 1968 who received live measles vaccine (monovalent vaccine before MMR) need verification of immune status, as efficacy of these earlier vaccines varied.

Immunity wanes very rarely with MMR. Once vaccinated with two doses, protection is long-lasting, sometimes lifelong. Breakthrough cases in vaccinated people are extremely rare. When they do occur, disease is usually milder and complications are less common.

During outbreaks, healthcare providers use different approaches for different populations. Unvaccinated people should be vaccinated urgently. Under-vaccinated people (one dose) should receive the second dose. Recently exposed people may receive vaccine immediately or immune globulin depending on timing and vaccination status.

Close contacts of measles cases are considered exposed. Exposed unvaccinated or single-dose vaccinated individuals should receive vaccine or immune globulin within 72 hours if possible, ideally within 24 hours. Immune globulin provides temporary protection; vaccine provides lasting immunity.

Herd immunity thresholds for measles are high. Because measles spreads so effectively from person to person, approximately 90-95% population immunity is needed to prevent widespread transmission. Below that threshold, outbreaks can spread through the unvaccinated population. The more under-vaccinated pockets exist, the more outbreaks can propagate.

Some people can't receive MMR vaccine. Severely immunocompromised individuals can't receive a live vaccine. Pregnant women can't receive it. Children with certain allergies (specifically egg allergy or gelatin allergy if severe) may not be able to receive it. These groups depend on high vaccination rates in the surrounding population for herd immunity protection.

When vaccination rates drop below threshold levels in any geographic area or institution, measles can establish transmission within the unvaccinated group. It then can spill over to vulnerable unvaccinated individuals who can't be vaccinated. This is the situation driving the current outbreak.

Long-Term Sequelae and Disability

Families dealing with measles encephalitis face not just the acute crisis but potential long-term consequences. Among children who survive measles encephalitis, approximately one-third develop permanent neurological damage. Some experience complete recovery. Others face lasting disability.

Developmental delays are common. Children who had measles encephalitis often show delayed motor milestones, delayed language development, and delayed cognitive development. They may require special education services, speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy. School districts become involved. Educational plans are developed.

Intellectual disability ranges from mild to severe. Some children have minor learning difficulties. Others have profound intellectual disability affecting all aspects of functioning. The degree of brain inflammation, the regions affected, and the individual child's recovery capacity all influence outcomes.

Seizure disorders develop in a significant proportion. Children require ongoing antiepileptic medication. They face risks of breakthrough seizures. Some eventually become seizure-free; others manage chronic epilepsy for life. Each medication has potential side effects. Drug interactions complicate any other medical conditions.

Behavioral problems emerge in some children. Changes in personality, emotional regulation difficulties, attention problems, and hyperactivity can follow encephalitis. These behavioral changes complicate the child's social development and family relationships.

Hearing loss from measles can occur through direct viral damage to the cochlea or through complications like meningitis. Some cases are temporary. Others are permanent. Hearing aids or cochlear implants may be necessary. Speech and language development are affected if hearing loss occurs during critical developmental periods.

Physical disability can result from severe encephalitis. Weakness, spasticity, movement disorders, and loss of fine motor coordination can impair a child's ability to perform activities of daily living. Wheelchair dependence can develop. These children face ongoing medical needs.

The family burden extends far beyond the medical issues. Parents face emotional trauma from watching their child critically ill. Siblings experience reduced parental attention during hospitalization and recovery. Financial burden from medical bills, lost work, and potential need for full-time caregiving affects family stability. Relationships strain under the stress.

These aren't abstract statistics. They're real children whose futures were altered by a preventable disease. They're families whose lives changed overnight. Multiply this across dozens of cases from the current outbreak, and the accumulated human cost becomes clear.

Prevention Strategies and Community Approaches

Preventing measles outbreaks requires multiple strategies working in concert.

Vaccination remains the cornerstone. Getting vaccination rates above 95% in every community creates herd immunity that prevents transmission. This requires reliable vaccine access, trusted healthcare providers recommending vaccination, accurate information about vaccine safety, and addressing underlying barriers.

Addressing hesitancy requires relationship-building. Studies show that hesitant parents are more likely to accept vaccination recommendations from their trusted healthcare provider than from public health agencies or social media. If a parent has trusted their pediatrician with their child's health, they're more likely to trust the pediatrician's vaccination recommendation.

Community partnerships increase reach. Working with churches, community centers, schools, and cultural organizations helps reach populations that might be skeptical of government health messages. These trusted community institutions can provide accurate information about vaccination.

Addressing misinformation requires countering it effectively. Simply stating facts doesn't overcome false beliefs. Research on effective communication shows that corrections must provide an alternative explanation for the misunderstanding. Explaining why people believe the false information helps.

Removing access barriers matters. Making vaccines free, easily accessible, offered during convenient hours, and provided without extensive paperwork increases vaccination rates. Mobile clinics reach rural populations. Workplace vaccination programs reach working adults. School-based clinics reach students.

School immunization requirements with minimal exemptions drive high coverage. States with strong requirements and limited exemptions have sustained high vaccination rates. Conversely, states with broad philosophical exemptions see increasing under-vaccination.

Healthcare provider education ensures strong recommendations. Physicians and nurses need to be trained in vaccine communication, understand the evidence base, and be supported in providing strong recommendations to patients.

Outbreak response measures provide additional protection. Once outbreak is detected, rapid case identification, isolation of confirmed cases, quarantine of exposed individuals, and rapid vaccination of high-risk contacts can slow transmission while vaccination campaigns increase population immunity.

Global vaccination efforts reduce importation risk. Measles elimination in other countries reduces the likelihood of importation into the US. Supporting global immunization programs through international health organizations reduces transmission reservoirs.

The most effective approach combines sustained prevention during non-outbreak times (maintaining high vaccination coverage through routine practice and trust-building) with rapid response when outbreaks occur. Waiting for an outbreak to mobilize resources is inefficient. The outbreak itself is evidence of failure of sustained prevention efforts.

Future Outlook and Policy Considerations

The trajectory suggests measles cases will continue increasing in the absence of sustained vaccination efforts. Each outbreak demonstrates vulnerability. Each outbreak reveals population pockets with insufficient immunity. Without addressing the underlying causes of vaccine hesitancy and access barriers, the pattern will repeat.

Policymakers face choices. Strengthen school immunization requirements by limiting exemptions. Invest in public health infrastructure for outreach and vaccination. Support healthcare providers in vaccine advocacy. Fund research into effective vaccine communication strategies. These investments cost far less than managing measles outbreaks.

Challenges remain. Polarization around health issues makes straightforward public health messaging difficult. Misinformation spreads faster than corrections. Balancing respect for individual choice with protection of vulnerable populations creates tension.

Technological approaches are being explored. New vaccine formulations. Combination vaccines reducing needle sticks. Needle-free administration methods. These innovations may improve uptake, but they're not sufficient without addressing hesitancy and access.

The South Carolina outbreak will eventually be controlled. Cases will peak, then decline as vaccination rates rise and susceptible populations are exhausted. Public health will declare the outbreak over. But the underlying conditions that enabled it will remain unless addressed.

The next outbreak is almost inevitable without systemic change. The question is when it will occur and how severe it will be. Will we learn from this crisis, or will we wait for the next one?

FAQ

What is measles and how is it transmitted?

Measles is a highly contagious viral infection spread through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes. The virus can remain in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves. One infected person will infect 12-18 unvaccinated people in an unimmunized population, making it one of the most contagious viruses known.

What is encephalitis and how does it develop with measles?

Encephalitis is inflammation and swelling of the brain. With measles, it develops either when the virus directly invades brain tissue or when the immune system overreacts to the viral infection, causing inflammatory damage. It typically occurs within 7-30 days of initial measles infection and affects approximately one to two per thousand measles cases, though this represents dozens of children during large outbreaks.

What are the symptoms of measles encephalitis?

Symptoms include seizures, severe headache, high fever, confusion, lethargy, loss of consciousness, stiffness in the neck, irritability, and extreme light sensitivity. These symptoms constitute a medical emergency requiring immediate hospitalization and intensive care.

What is SSPE and how does it differ from acute encephalitis?

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive, degenerative brain disease caused by persistent measles virus in the brain that reactivates years after initial infection. Unlike acute encephalitis which develops within weeks, SSPE typically emerges 7-10 years after measles infection and is progressive and fatal, with no effective treatment.

What is the mortality rate of measles encephalitis?

Among children who develop measles encephalitis, 10-15 percent die. Among survivors, approximately one-third develop permanent neurological damage including developmental delays, intellectual disability, seizure disorders, behavioral problems, or hearing loss.

How effective is the MMR vaccine at preventing measles?

One dose of MMR vaccine is 93% effective at preventing measles. Two doses are 97% effective. Protection is long-lasting and typically lifelong. Breakthrough infections in vaccinated people are extremely rare.

Why are measles cases increasing if we had a vaccine for decades?

Measles cases are increasing due to declining vaccination rates driven by misinformation about vaccine safety (particularly the debunked autism-vaccine link), access barriers, philosophical and religious objections, and distrust of medical institutions. Social media has amplified misinformation, creating echo chambers of vaccine hesitancy.

What is immune globulin and when is it used?

Immune globulin is a concentrated preparation of antibodies from donated plasma. When given within 72 hours of measles exposure, it prevents infection by providing temporary passive immunity. It's used for exposed unvaccinated individuals who cannot receive vaccine, including pregnant women and severely immunocompromised people.

Can pregnant women receive the MMR vaccine?

No, pregnant women cannot receive MMR vaccine because it's a live vaccine. Pregnant women who are not immune should be vaccinated before pregnancy to ensure protection during pregnancy and future pregnancies.

What population groups face highest risk from measles?

Highest-risk groups include infants under 12 months of age, children under five years, immunocompromised children, pregnant women, and people with vitamin A deficiency. These groups face higher rates of severe disease, complications, and death from measles.

What herd immunity threshold is needed to prevent measles transmission?

Approximately 90-95% population immunity through vaccination is needed to prevent measles transmission. Below this threshold, the virus can spread through unvaccinated populations. When under-vaccinated pockets exist in communities, localized outbreaks can occur.

Conclusion: The Choice Before Us

The South Carolina measles outbreak represents a crossroads. It's a demonstration of what happens when vaccination coverage drops below protective thresholds. It's a reminder that measles never left; it simply retreated when vaccination rates were high. It's evidence of what we risk losing if we allow vaccine hesitancy and access barriers to persist.

More immediately, it's personal. Behind each case count is a child, a family, a community affected by a preventable disease. The children developing encephalitis have futures altered by brain inflammation that vaccination could have prevented. The parents sitting in pediatric ICU units are living nightmares they didn't expect in 2024.

Public health responses are appropriate but insufficient. Vaccination campaigns after an outbreak begins are valuable but they're treating the symptom rather than the disease. True prevention requires sustained effort during peacetime, not just crisis response.

For individuals, the path forward is clear. Verify your vaccination status. Ensure you have two MMR doses. If uncertain, check with your healthcare provider or get an antibody titer test. Recommend vaccination to friends and family. Counter misinformation with accurate information when you encounter it.

For healthcare providers, the challenge is more nuanced. Strong vaccine recommendations to hesitant patients require skill and relationship. Understanding why someone is hesitant, addressing specific concerns with evidence, and maintaining trust even when recommending something the patient is reluctant about requires expertise. Professional organizations should support providers with training and resources.

For policymakers, the choices are harder because they involve balancing values. Strengthening school immunization requirements protects public health but raises concerns about parental autonomy. Mandates work but erode trust if perceived as heavy-handed. Voluntary approaches respect choice but leave vulnerable populations at risk. The difficult middle path involves finding ways to make vaccination the obviously smart choice through availability and trust-building rather than coercion.

For public health agencies, the imperative is to learn from this outbreak. Document what worked, what didn't, and why. Design systems that maintain high vaccination coverage during non-crisis times. Build relationships with communities before crises arrive. Address misinformation before it becomes deeply rooted. Invest in infrastructure that makes outbreak response rapid and effective.

The immediate crisis will pass. Cases will decline. Hospitalizations will decrease. The media will move on to the next story. But the question of what we learned and whether we're prepared for the next outbreak will linger. South Carolina's experience is a gift of information, albeit a painful one. The question is whether we'll use it wisely.

Measles is a preventable disease. We have proven tools: a vaccine that's 97% effective, infrastructure to deliver it, and knowledge about what works in prevention. What we lack is consistent application of what we know. We have the ability to prevent the next outbreak. We have the ability to eliminate brain inflammation in children. The only question is whether we have the will.

Key Takeaways

- South Carolina's measles outbreak infected 876+ people by February 2025, with 700 cases arriving since January—demonstrating explosive growth of a preventable disease

- Encephalitis (brain swelling) is affecting outbreak children, carrying 10-15% mortality rate and leaving one-third of survivors with permanent neurological damage including seizures, hearing loss, and intellectual disability

- Declining vaccination rates drive the resurgence—2024 saw the highest US measles cases in 30 years at 2,267, reflecting misinformation, access barriers, and vaccine hesitancy

- SSPE (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) is a progressive, fatal brain disease that emerges years after measles infection with no cure, affecting approximately 2 in 10,000 measles cases

- MMR vaccine provides 97% protection with two doses and remains the most effective prevention strategy—South Carolina achieved 72% increase in vaccinations during outbreak response

![Measles Brain Swelling: South Carolina Outbreak and Encephalitis Risk [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/measles-brain-swelling-south-carolina-outbreak-and-encephali/image-1-1770241089436.jpg)