The Brain-Computer Interface Revolution Is Getting Its Most Ambitious Bet Yet

When Sam Altman left his role as CEO of OpenAI to focus on other ventures, the tech world watched carefully. But here's what most people missed: he wasn't stepping away from AI—he was betting on something potentially bigger. In early 2025, his neurotechnology startup Merge Labs emerged from stealth mode with a stunning $252 million in funding, backed by OpenAI itself, billionaire investor Gabe Newell, and Bain Capital.

This isn't just another neurotechnology company. Merge Labs is attempting to solve one of humanity's oldest dreams: direct communication between the human brain and artificial intelligence, without surgery, without implants, without permanent alteration of brain tissue.

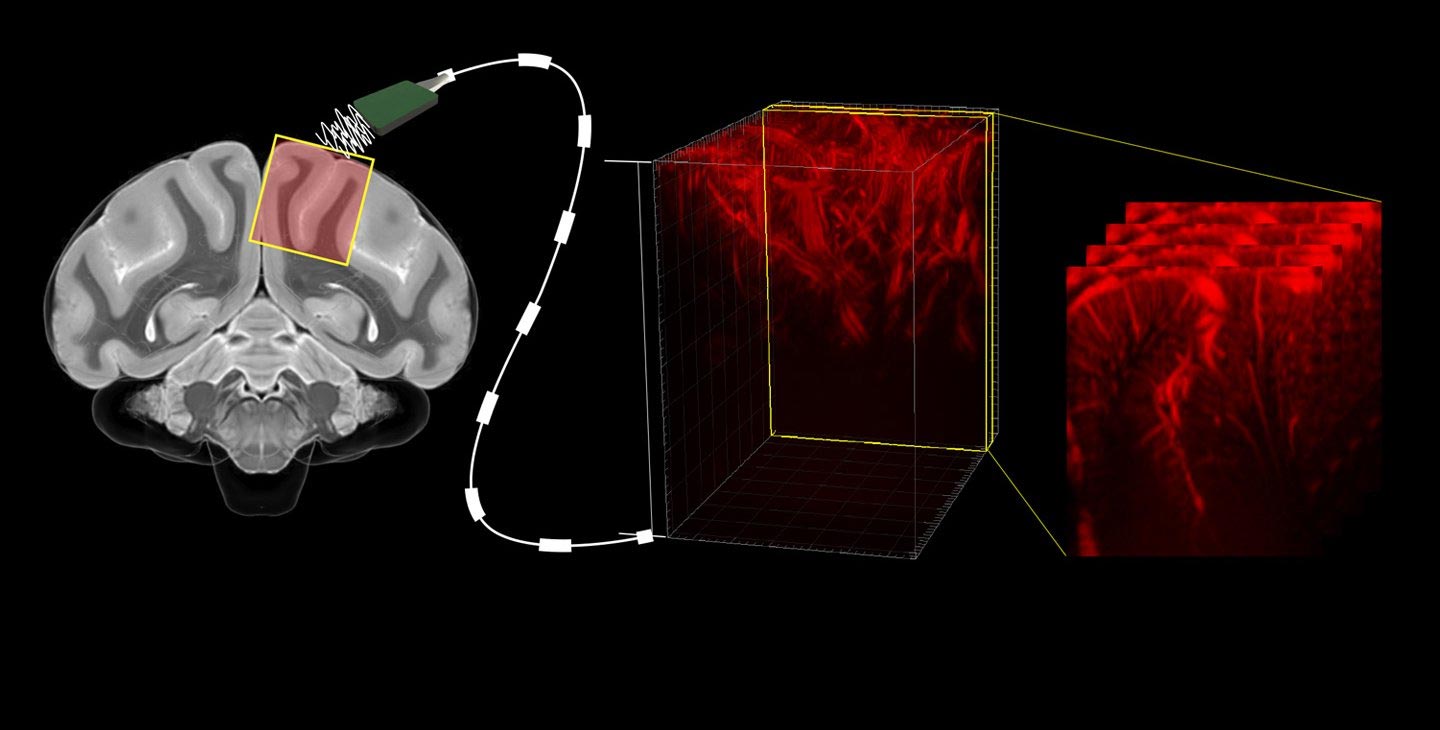

Instead of drilling into skulls like Neuralink does, Merge Labs uses something almost mundane: ultrasound. The same technology that lets doctors see fetuses in the womb and surgeons repair soft tissue damage. But Merge's application is radically different. They're using ultrasound waves to read neural activity, understand what your brain is trying to do, and potentially write information back in.

The implications are staggering. Imagine restoring sight to the blind, movement to the paralyzed, or giving people with locked-in syndrome the ability to communicate again. Now imagine doing it without brain surgery. This is the problem Merge Labs is trying to solve.

Why This Moment Matters: The Convergence of AI, Neuroscience, and Accessibility

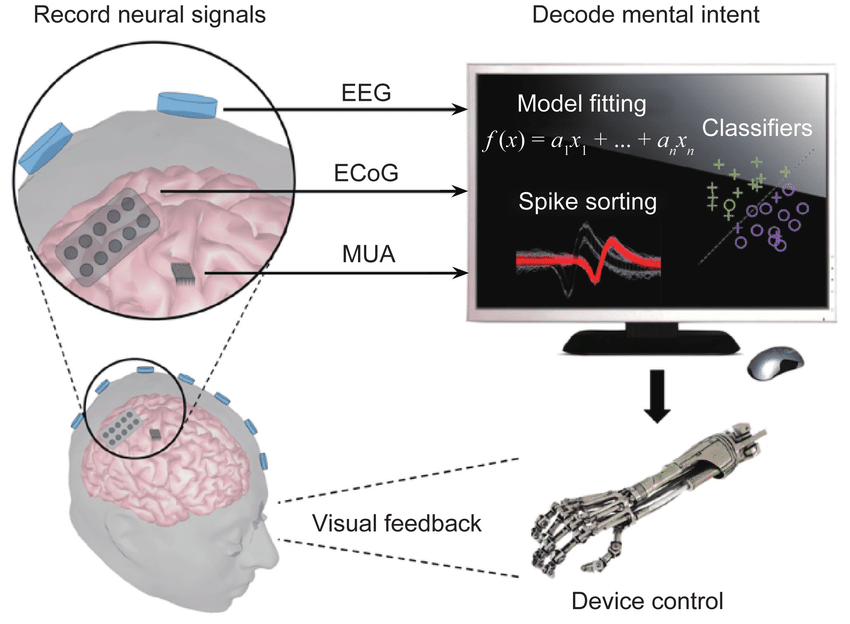

Brain-computer interfaces aren't new. Scientists have been exploring neural decoding since the 1960s. But they've always faced the same brutal tradeoff: more detailed information requires more invasive implants. You want high-resolution signal? You need electrodes pressed against brain tissue, which causes inflammation, requires surgery, and carries infection risk.

Merge Labs is betting on a different premise: what if you don't need high-resolution electrodes? What if AI models sophisticated enough to interpret fuzzy, incomplete signals could work with lower-bandwidth inputs?

This is where the timing becomes critical. OpenAI's foundation models have shown remarkable ability to work with noisy, incomplete, or ambiguous data. They can infer intent. They can handle uncertainty. They learn from context.

Merge Labs is explicitly building on this insight. According to their announcement, they're developing "scientific foundation models" specifically trained on brain data. These aren't general-purpose language models. They're neural interpreters—AI systems that learn to understand what a brain is trying to do, even when the signals are faint, delayed, or scrambled by biological noise.

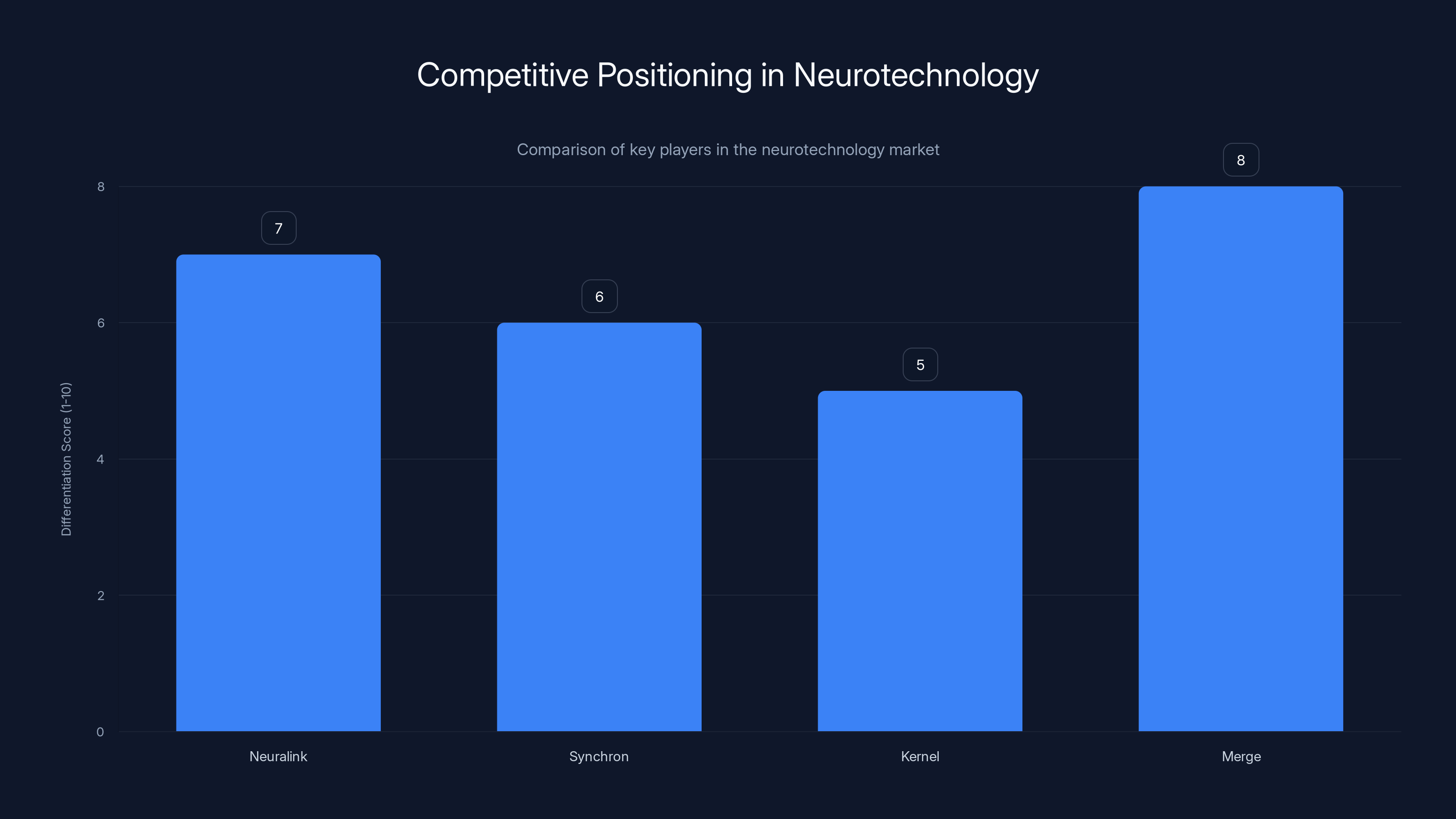

The competitive landscape here is fierce but fragmented. Synchron, another major player, has raised

Imagine a world where, instead of waiting years for surgical opportunities, someone paralyzed by ALS or stroke could wear a device on their head that gradually learns their neural patterns. No surgery. No recovery. No permanent scarring.

That's the future Merge is building toward.

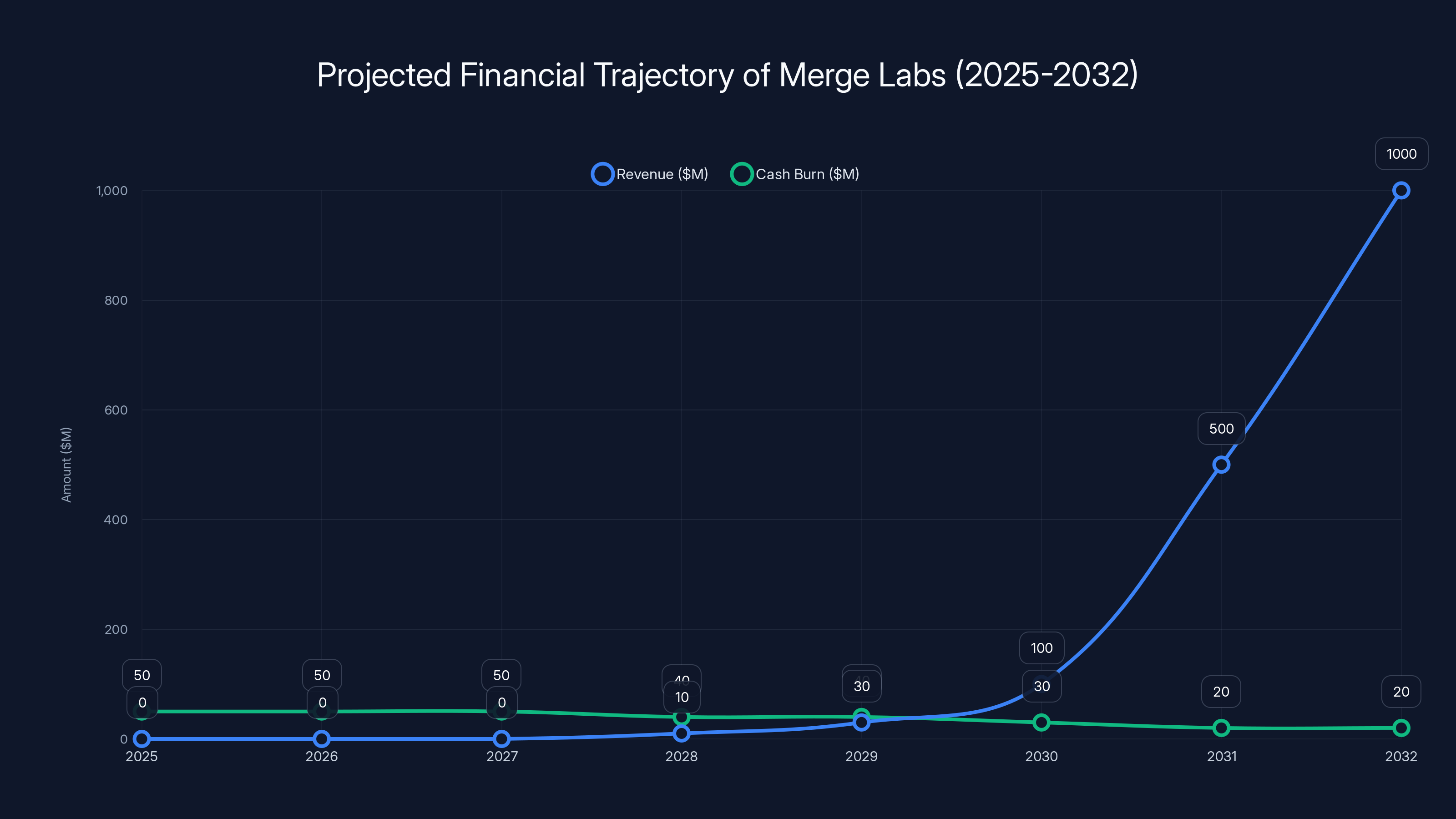

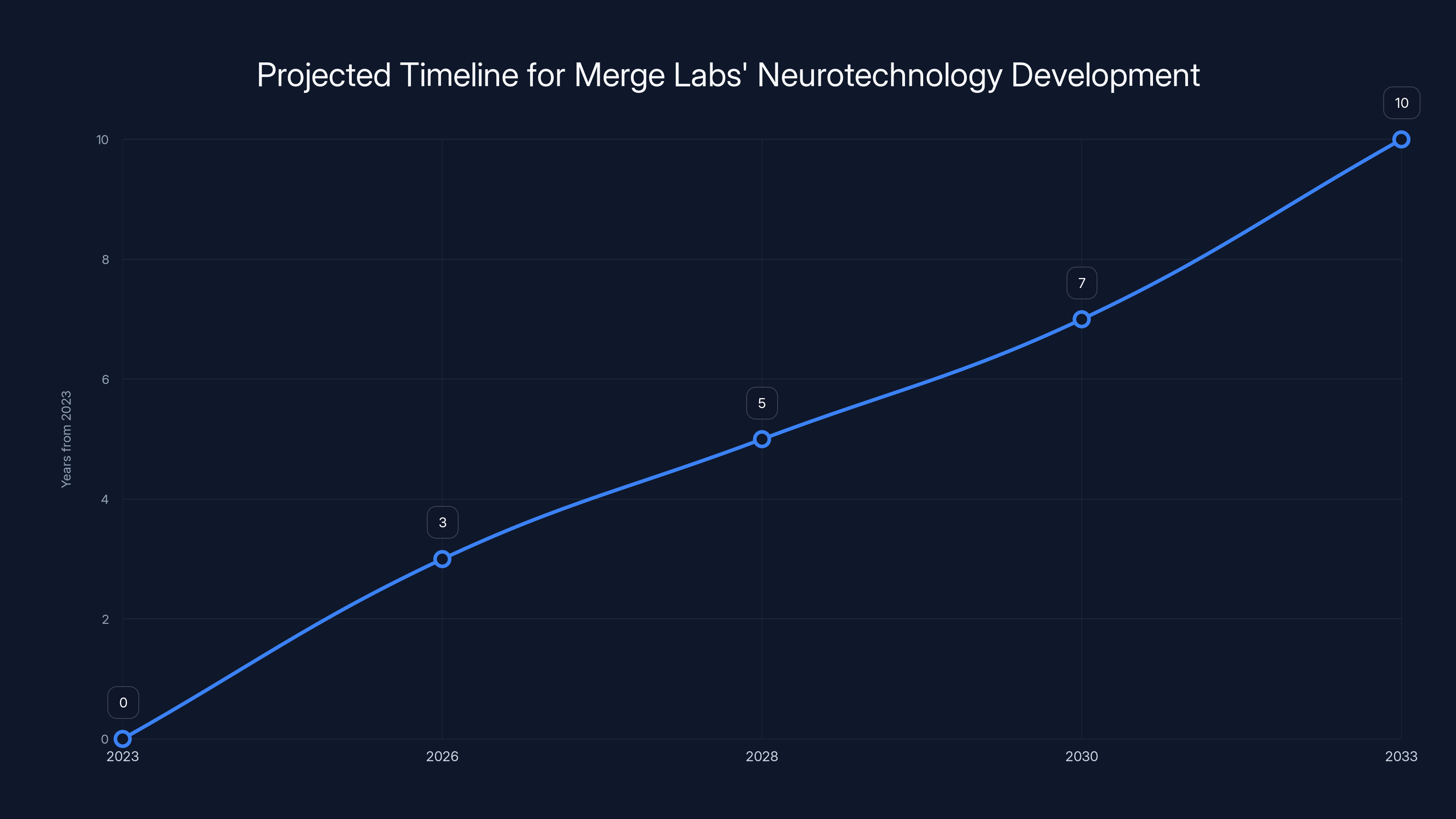

Merge Labs is projected to start generating significant revenue by 2030, potentially reaching $1 billion by 2032 if milestones are met. Estimated data.

The Ultrasound Breakthrough: How It Works Without Drilling Into Your Brain

Here's the key technical distinction that separates Merge from Neuralink and Synchron. Most brain-computer interfaces measure electrical activity directly. Electrodes sit on or in neural tissue, detecting the tiny electrical pulses that fire when neurons communicate. It's like listening to a conversation by holding a microphone to someone's ear.

Ultrasound-based interfaces work completely differently. They don't measure electrical signals at all. Instead, they detect blood flow changes in the brain.

This might sound less direct, but there's elegant physics behind it. When neurons fire, they consume glucose and oxygen. Blood rushes to those areas to meet the metabolic demand. Ultrasound waves can detect these minute changes in blood velocity and volume. It's indirect, but it's real-time and non-invasive.

Why is this better? Several reasons:

Non-invasive by design. Ultrasound waves pass through the skull without damage. No implants needed. No surgical recovery. No risk of electrode rejection or scar tissue formation.

Reversible. You can put the device on and take it off. If something goes wrong, you stop using it. Compare that to a surgical implant that requires brain surgery to remove.

Broad coverage. An electrode picks up signals from a few dozen neurons in its immediate vicinity. Ultrasound can interrogate larger brain regions, potentially capturing more complex patterns of activity.

Faster scaling. Clinical trials for implantable devices take years. Regulatory approval is glacial. A non-invasive device could move through trials and FDA clearance much faster.

But here's the catch—and it's important: ultrasound signals are noisier than direct electrode recordings. The relationship between blood flow changes and neural intent is probabilistic, not deterministic. You're making inferences, not reading raw data.

This is exactly where the AI component becomes essential. A classical algorithm trying to decode ultrasound signals would fail. But a foundation model trained on thousands of hours of ultrasound recordings paired with ground truth data (what the person was actually trying to do)? That can learn to recognize patterns humans never would.

Forest Neurotech, the nonprofit research organization that Merge Labs spun out from, has already demonstrated this works in humans. A miniaturized ultrasound device developed by Forest is currently in clinical trials in the UK. At least one participant has shown ability to control external devices using ultrasound-based decoding.

That single data point is enormous. It proves the concept isn't theoretical. It works.

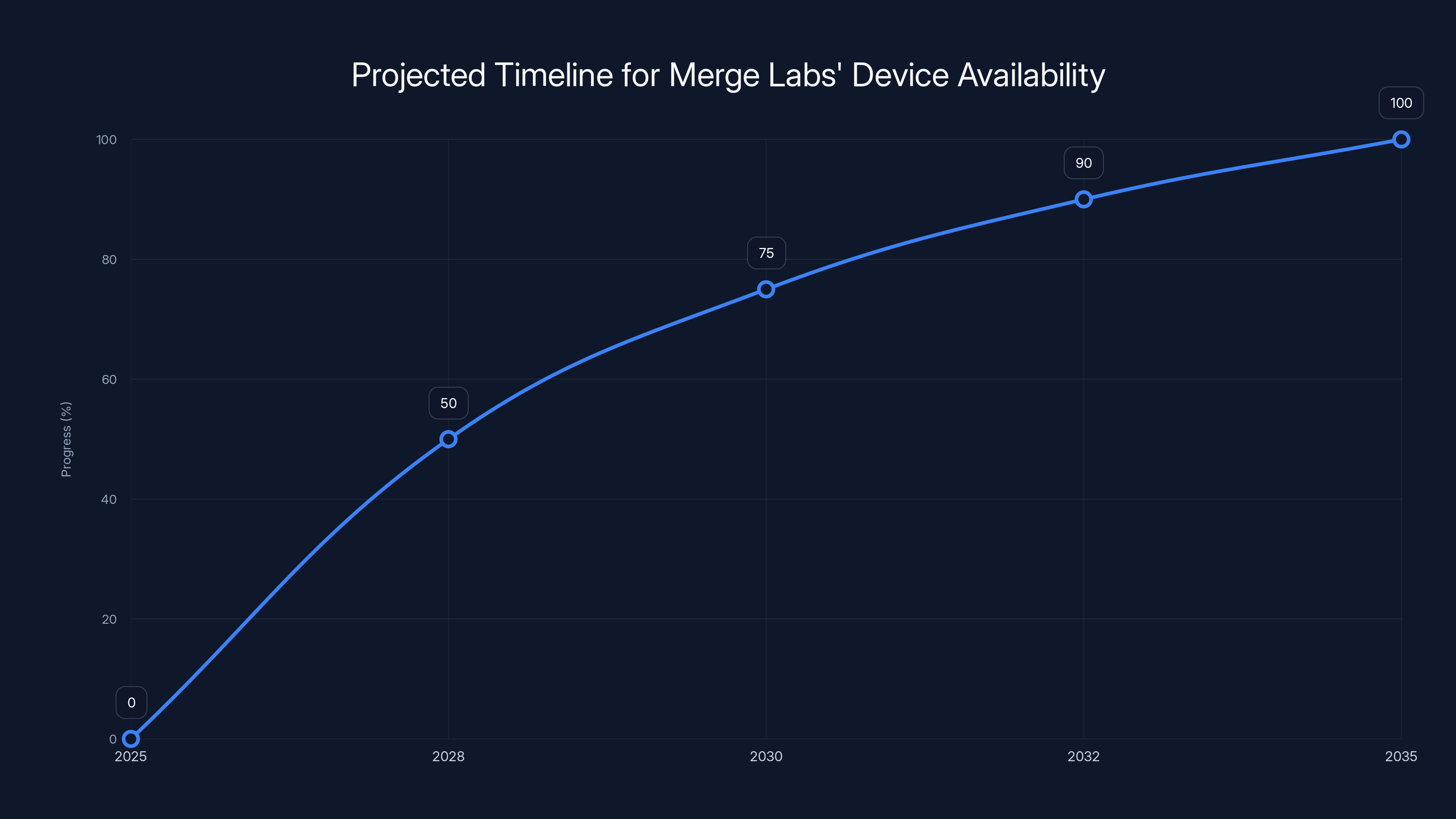

Estimated data shows clinical trials starting in 2025, with FDA approval around 2030 and commercial availability by 2032. Consumer versions may follow by 2035.

The Team Behind the Vision: Academic Rigor Meets Silicon Valley Ambition

Merge Labs isn't a group of entrepreneurs who happened to read a neuroscience paper. The founding team bridges the gap between cutting-edge research and commercial viability in a way that's rare.

Mikhail Shapiro, one of the cofounders, is a researcher at Caltech specializing in biomedical ultrasound. He literally invented much of the underlying technology. Tyson Aflalo comes from research on brain-computer interfaces for rehabilitation. Sumner Norman brings neuroscience expertise and clinical experience.

Then there's the business side. Alex Blania and Sandro Herbig are seasoned entrepreneurs who've navigated the complexity of deep-tech commercialization before. And of course, Sam Altman brings capital, credibility, and years of thinking about the "merge" between human and machine intelligence.

This matters because brain-computer interface startups are notoriously capital intensive, technically complex, and regulatory-heavy. You need scientists who understand the limits of the technology. You need entrepreneurs who can execute at scale. And you need capital from people who aren't going to panic when FDA approval takes longer than expected.

The fact that OpenAI is collaborating directly on foundation models is also significant. This isn't just a financial investment. OpenAI is committing engineering resources and research talent to the project. They're betting their reputation and resources on Merge.

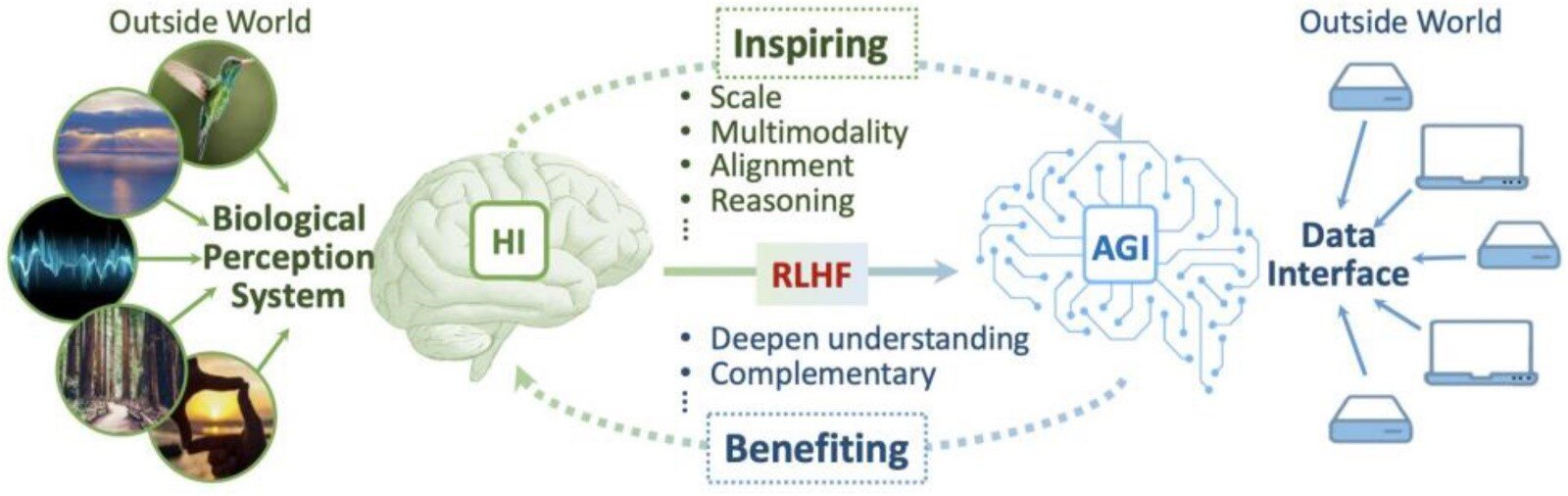

How AI Foundation Models Change the Game for Neural Decoding

Let's dig into why OpenAI's involvement is so crucial here. Most neurotechnology companies treat AI as a tool. They use machine learning algorithms to decode signals. Useful, but limited.

Merge and OpenAI are thinking bigger. They're building foundation models for the brain. These are deep learning systems trained on massive amounts of brain activity data, designed to develop general-purpose understanding of neural patterns.

Here's the concrete difference:

Old approach: Train a neural network to map specific signals to specific behaviors ("when we see pattern X, the person wants to move the cursor right"). Works for that specific task, but doesn't generalize.

Foundation model approach: Train on diverse brain activity from many people, many tasks, many states of consciousness. The model develops rich representations of what different neural patterns mean. Then fine-tune for specific applications with minimal additional data.

This changes several things:

Sample efficiency. Right now, getting a brain-computer interface working for one person requires hours of calibration. They have to repeatedly perform actions while the system learns their neural signatures. Foundation models could reduce this to minutes. The model already understands the general principles of human neural organization.

Personalization at scale. Each brain is different. Each person's neural patterns are unique. A foundation model can learn these individual variations much faster than training from scratch.

Transfer learning. Skills learned from one task could transfer to others. If someone learns to control a cursor, could they control a robotic arm more quickly using the same underlying neural patterns? Foundation models make this possible.

Robustness and adaptation. Neural activity changes over time. Inflammation, scar tissue, electrode drift—all degrade signal quality. Foundation models can learn to adapt to these changes, potentially extending device life by years.

Synchron, working with Nvidia on similar foundation models, has recognized this too. The entire industry is converging on the same insight: raw AI capability applied to noisy neural data can unlock capabilities we haven't achieved before.

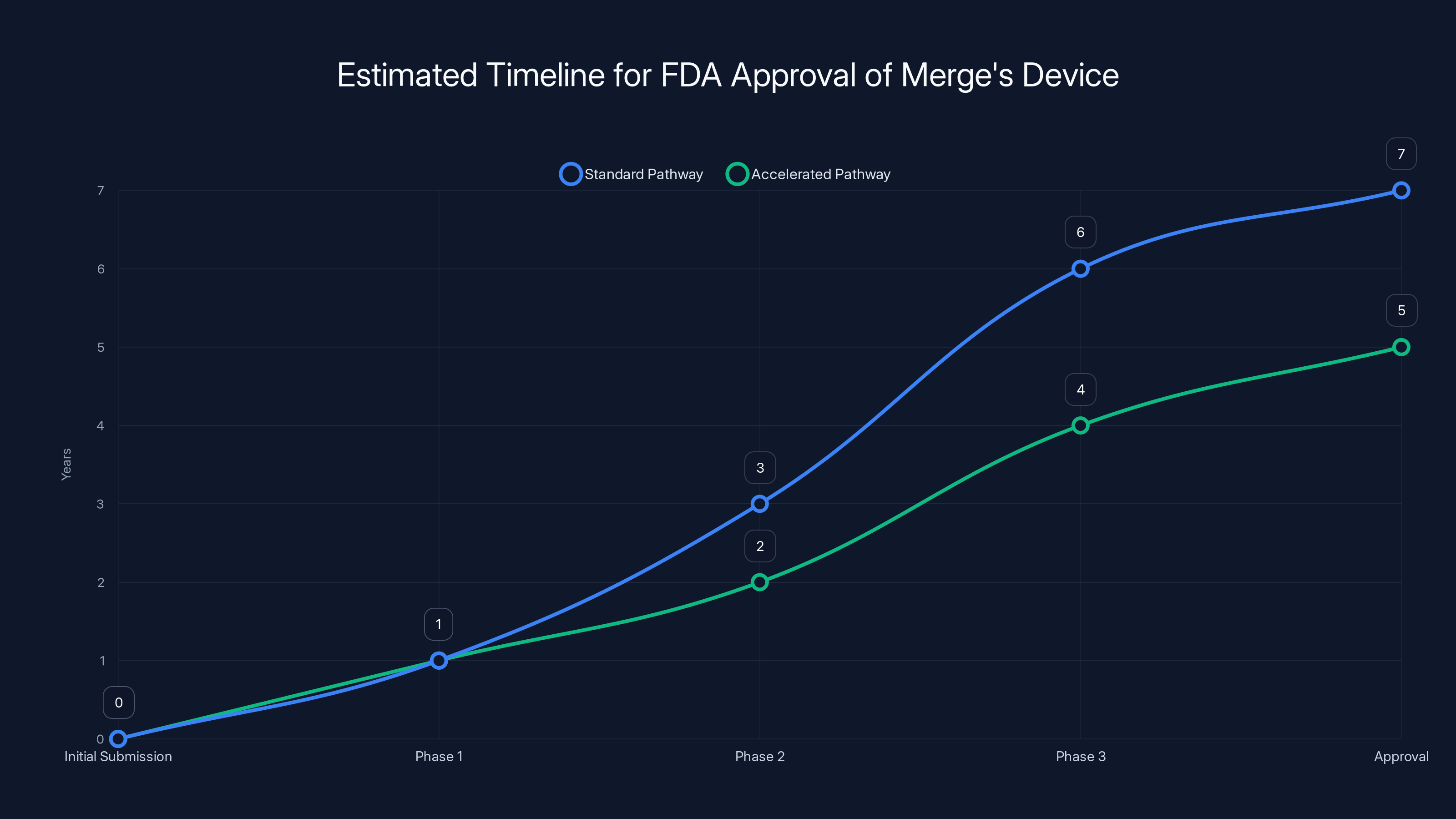

The standard FDA approval process for Merge's device could take 7 years, but using the Breakthrough Device Program could reduce this to 5 years. Estimated data based on typical timelines.

The Current State of Brain-Computer Interfaces: Where Everyone Stands

To understand what Merge Labs is attempting, you need context on the existing landscape. This space has exploded in the past two years.

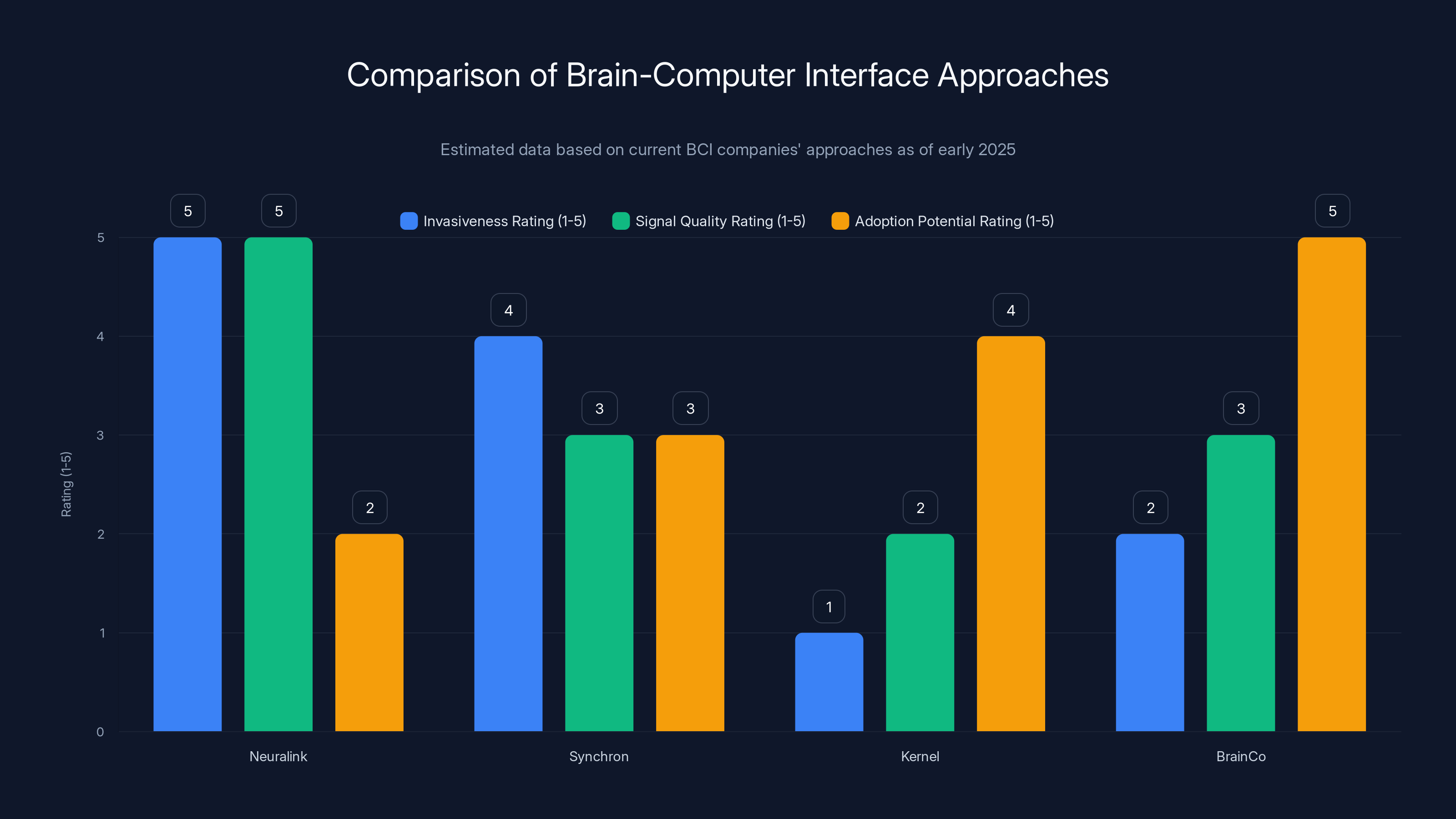

Neuralink has received the most media attention. Elon Musk's company has implanted devices in at least 12 humans as of early 2025. The approach is high-bandwidth and invasive. They surgically implant an array of electrodes directly into brain tissue (the N1 implant has 1,024 electrodes). The signal quality is exceptional. But the entry barrier is surgery.

Neuralink has demonstrated genuinely impressive capabilities. One patient, a 29-year-old quadriplegic named Noland Arbaugh, can control a computer cursor, play video games, and even use AI to design 3D printed objects—all through thought alone. It's remarkable progress.

But there's a limit to how many people can get brain surgery. There are infection risks, neuroinflammation risks, and the permanent alteration of brain tissue. Neuralink will serve patients with severe paralysis or locked-in syndrome. For everyone else, it's not viable.

Synchron is taking a different invasive approach. Instead of penetrating brain tissue, they implant a device inside a blood vessel next to the brain. It's less invasive than Neuralink but still requires surgery and carries vascular risks. About 10 people have received Synchron devices as of early 2025. The signal quality is lower than Neuralink, but the procedure is less risky.

Kernel, a neurotechnology company focused on brain imaging, is pursuing non-invasive approaches using optical sensors. They measure light absorption changes in the brain, which correlate with neural activity. It's completely non-invasive but has lower spatial resolution and slower temporal response.

Brain Co, a Chinese company, is working on consumer-grade EEG-based interfaces. Electrodes on the scalp measure electrical activity, completely non-invasive but with very poor signal quality. It works for basic applications but not for real-time control tasks.

Merge's positioning is fascinating. They're aiming for something between Synchron's invasiveness and Kernel's signal quality. Non-invasive enough for routine clinical adoption. Good enough signal quality for meaningful control tasks. The sweet spot that could scale to millions of patients.

The Applications: Medical, Consumer, and the Boundaries Between Them

Merge hasn't publicly specified which applications they'll pursue first, but the clues are obvious. Forest Neurotech, their nonprofit parent, has focused on mental health disorders and brain injuries. That's almost certainly where Merge will start.

Paralysis and motor dysfunction is the obvious first application. ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) patients gradually lose motor control. Stroke survivors often experience lasting paralysis. Spinal cord injury patients are locked in immobile bodies while their minds remain sharp. A brain-computer interface could restore communication, mobility through robotic devices, or even direct neural stimulation of remaining intact motor pathways.

The timeline for impact here is real. Merge could have meaningful clinical results within 3-5 years, regulatory approval within 5-7 years, and commercial availability by 2030.

Mental health is more speculative but potentially enormous. If you can read neural activity associated with depression, anxiety, or PTSD, can you intervene? Can you provide targeted neural stimulation that alleviates symptoms? This is exactly where Forest has been researching. It's risky territory (how do you even define "therapeutic" neural modulation?), but the potential is huge.

Sensory restoration comes next. Blindness, deafness, loss of touch—if you can decode what the brain expects to experience and feed that information through alternative pathways, you could restore function. This is harder than motor control because sensory perception involves massive cortical areas. But it's not impossible.

Then there's the consumer angle, which Sam Altman has hinted at. What if healthy people wanted brain-computer interfaces? What if you could think faster, access information without typing, or directly interface with AI?

This is where ethics gets complicated. Merge has framed it as "broadly accessible," suggesting they want this to be consumer-grade, not just for patients. That's ambitious and potentially controversial.

Neuralink offers the highest signal quality but is the most invasive, while Kernel provides a non-invasive approach with lower signal quality. BrainCo shows high adoption potential due to consumer-grade focus. Estimated data.

The Funding Moment: Why $252 Million Now?

That quarter-billion-dollar funding number isn't arbitrary. It reflects several converging factors.

First, venture capital has gotten comfortable with deep tech. A decade ago, a neurotechnology startup would have struggled to raise even $50 million. The entire biotech funding environment has shifted. Investors now understand that technical risk is worth taking if the market opportunity is large enough.

Second, the AI moment is undeniable. Foundation models have made it clear that large-scale training on diverse data can create general-purpose intelligence. This principle applies to neural decoding. Investors see this connection and are funding accordingly.

Third, Neuralink has proven the market exists. Their rapid human trials, media coverage, and demonstration of working implants in humans has validated the entire category. It's shown that brain-computer interfaces aren't science fiction—they're engineering.

Fourth, Sam Altman's credibility is enormous. He founded and ran OpenAI through its explosive growth from nonprofit research lab to commercially dominant AI company. When he cofounds a company, serious investors pay attention. Bain Capital and Gabe Newell aren't betting on the technology alone—they're betting on the team's execution ability.

But here's what's really interesting: OpenAI's investment signals they believe this technology matters for their future. Why would the leading AI company invest in neurotechnology? Because they think the future of human-AI interaction involves neural interfaces. Because they want to be positioned at that intersection. Because brain-computer interfaces represent an entirely new modality for training and deploying AI systems.

The Technical Challenges Merge Still Needs to Solve

Let's be honest about the hard problems. Merge has a compelling vision, but the technical execution is brutally difficult.

Signal interpretation at scale. Ultrasound provides lower-bandwidth, noisier signals than direct electrode recording. Getting from "noisy blood flow measurements" to "clear commands" requires AI models that work exceptionally well with imperfect data. This is solvable, but it's not simple.

Individual variability. Every brain is different. Every person's ultrasound imaging is unique based on skull thickness, brain shape, and individual anatomy. A device that works perfectly for one person might fail for another. The personalization problem is real.

Temporal dynamics. Neural activity changes. Inflammation from the ultrasound device itself could change signal quality over time. Neuroplasticity means the brain adapts and changes as people learn to use the interface. Merge's systems need to adapt faster than the biology changes.

Regulatory pathway. The FDA has never approved an ultrasound-based brain-computer interface. There's no regulatory playbook. Merge will need to establish safety standards, efficacy metrics, and approval processes from scratch. This could add years to their timeline.

Scalable manufacturing. Clinical prototypes are one thing. Mass manufacturing reliable devices for thousands of patients is entirely different. Ultrasound transducers need precision fabrication. The associated AI hardware needs to work reliably in the field.

Real-world robustness. In a clinical lab, everything is controlled. Temperature is stable. Power supply is reliable. But in actual use? People sweat. They move their heads. They go about their daily lives. The device needs to work through all of that.

These are hard problems. But they're engineering hard, not physics hard. They're solvable with enough time, money, and talent. And Merge seems to have all three.

Merge stands out with a high differentiation score due to its non-invasive approach and AI collaboration, despite being later to market. (Estimated data)

The "Merge" Concept: From Silicon Valley Philosophy to Practical Reality

The company's name references a concept Sam Altman has written about extensively: the idea of a "merge" between human and machine intelligence.

It's a Silicon Valley concept with deep roots. Ray Kurzweil wrote about human-machine merger in the context of the technological singularity. Elon Musk talks about neural lace as necessary for humanity to keep pace with AI. Altman has argued that human-AI merger might be inevitable for humanity to remain relevant.

But here's the key point: Merge Labs is taking this philosophical concept and making it concrete. They're not claiming to merge consciousness. They're not suggesting some mystical blending of human and machine minds.

What they're actually doing is far more practical: enabling direct information exchange between the human brain and AI systems. It's like connecting a new sense organ—instead of learning about the world only through eyes, ears, and touch, humans could access information from computers directly. Instead of typing or speaking to control systems, humans could simply think.

This has profound implications even before you get to the sci-fi stuff.

Information access. Right now, getting information requires going through a keyboard, voice interface, or screen. What if you could ask your AI assistant a question and experience the answer directly in consciousness? Not reading text, but knowing. Not watching a video, but understanding. This could fundamentally change human-computer interaction.

Motor restoration. This is already proven. If someone's paralyzed, you can decode their motor intention and execute it through a robot or functional electrical stimulation. This isn't sci-fi—Neuralink is doing this right now.

Cognitive augmentation. This is speculative but intriguing. What if you could offload certain cognitive tasks to an AI that's running on your neural interface? What if your AI could suggest ideas, connect concepts, or warn you of cognitive biases—all in real-time, integrated into your conscious experience?

Medical intervention. If you can read and write to the brain with high enough fidelity, you could potentially treat mental illness directly. Depression involves specific neural patterns. Anxiety involves recognizable activity. OCD involves repetitive neural loops. What if you could identify these patterns and directly modulate the neural activity?

Merge isn't claiming to solve all of this overnight. But the vision is clear: reduce the friction between human cognition and computational systems to the point where they're effectively merged. Not metaphorically. Literally in the brain, using ultrasound, in a form factor you'd want to wear regularly.

How This Relates to AI's Evolution and Future

Step back for a moment. Why is OpenAI investing in neurotechnology at all?

The answer goes to the heart of where AI is heading.

Current AI systems (like GPT-4) are trained on text, images, and other digital data. They optimize for token prediction, image classification, or other discrete tasks. They're powerful, but they're fundamentally extracting patterns from human-generated digital information.

What if you could train AI systems directly on human neural activity? What if you could build models that understand human intention at the neural level, not just inferred from text or behavior?

This is a different kind of training signal. It's closer to raw human cognition. An AI trained on direct neural data would potentially develop capabilities that purely digital AI can't.

Second, brain-computer interfaces represent a new interface for AI deployment. Instead of chatbots, you have neural-integrated AI. Instead of asking a question and waiting for an answer, you think and get results. This changes how people interact with AI, which changes what AI can do.

Third, there's a defensive aspect. Musk has argued that brain-computer interfaces are necessary to prevent AI from making humans obsolete. That's probably oversimplified, but the logic isn't crazy. If AI systems become dramatically more capable than unaugmented humans, human relevance decreases. Brain-computer interfaces could keep humans in the loop, collaborating with AI rather than being replaced by it.

From OpenAI's perspective, being positioned at the intersection of AI and neurotechnology is strategically valuable across multiple dimensions.

Estimated data shows that Merge Labs' neurotechnology could take 7-10 years for full commercial deployment, highlighting the long-term nature of their investment.

Regulatory Pathways: What Will It Actually Take to Get Approval?

Merge Labs will need FDA approval to sell their devices in the US. This is the hidden timeline in their growth story.

For invasive devices, there's a precedent. Neuralink went through the FDA's Breakthrough Device Program and received authorization for human trials. Synchron did the same.

But Merge's non-invasive device is in a different category. There's no existing pathway specifically for ultrasound-based brain-computer interfaces. The FDA will likely classify it as a Class II or III medical device, requiring either 510(k) clearance (comparison to existing devices) or Premarket Approval (PMA), which involves clinical trials.

The clinical trial requirements are the real bottleneck. For a device intended to restore motor function to paralyzed patients:

Phase 1 trials (safety and tolerability): Maybe 20-30 subjects, 6-12 months. Not super difficult.

Phase 2 trials (efficacy signals): 50-100 subjects, 12-24 months. Here's where you prove the device actually works.

Phase 3 trials (confirmation of efficacy): 100+ subjects, comparing against control or standard care, 24-36 months. This is where most devices fail or take forever.

Optimistically, Merge might have FDA approval within 5-7 years. In practice, it could easily be longer.

But there's an accelerated path. If Merge can show compelling benefits to severely paralyzed patients who have no other options, they might get expedited review. FDA's Breakthrough Device Program could shorten timelines by 1-2 years.

Regulatory approval is the unglamorous part of medtech that separates bold visions from actual products. Merge's team clearly understands this (they have experienced medtech people), but it's still the most likely source of delays.

The Competitive Dynamics: Where Merge Fits in a Crowded Landscape

Merge isn't entering a market alone. The neurotechnology space has exploded with funding and interest.

Neuralink has first-mover advantage in human implants. They've demonstrated working systems in humans. They have brand recognition. They have Elon Musk's marketing machine behind them. But they're locked into the surgical implant approach, which limits their addressable market.

Synchron is less invasive than Neuralink but still requires surgery. They've partnered with Nvidia on foundation models and raised significant capital. They're well-positioned but not significantly differentiated from Neuralink in terms of market approach (both invasive, both surgical).

Kernel is pursuing non-invasive optical approaches but is further behind in clinical validation and has lower signal quality than Merge's approach.

Merge's advantages:

Non-invasive. No surgery. No implants. No permanent alteration. This is a massive market differentiator.

Foundation models from OpenAI. Having the leading AI company collaborating on your neural decoding AI is a huge advantage.

Proven underlying tech. Forest Neurotech has already demonstrated ultrasound-based decoding in humans. It works.

Team credibility. The combination of academic neuroscientists and experienced entrepreneurs is rare and valuable.

Merge's disadvantages:

Unproven at scale. We have one success story from Forest. We don't know if it generalizes.

Later to market. Neuralink already has implants in humans. Merge is still in early clinical trials.

Regulatory uncertainty. New technology, new approval pathway. Unexpected delays are possible.

Signal quality tradeoffs. Ultrasound might never match the bandwidth of direct electrode recording. This could limit some applications.

The competitive landscape is likely to have multiple winners. Neuralink will dominate the ultra-high-performance, surgical implant space for patients with severe paralysis. Merge could own the broader market of patients with milder dysfunction, people wanting non-invasive augmentation, and consumer applications. Synchron might end up as the middle option.

This isn't winner-take-all. The total addressable market for brain-computer interfaces is huge (hundreds of millions of people with neurological conditions), so there's room for multiple players.

Financial Projections: When Could This Actually Return Value?

Merge Labs raised $252 million. That's enough runway for maybe 5-7 years of R&D and early commercialization. After that, they'll need to show clear path to profitability or raise more capital.

Let's think through the timeline:

Years 1-3 (2025-2028): Clinical trials, FDA submissions, some early commercial devices to specialized centers.

Revenue: Near zero. Maybe some research partnerships or grants.

Cash burn: High, probably $40-60M annually for clinical trials and R&D.

Years 3-5 (2028-2030): FDA approvals likely happening. Clinical adoption ramping. Direct-to-patient sales potentially beginning.

Revenue: $10-50M from clinical devices and institutional partnerships.

Cash burn: Still high, maybe $30-50M annually.

Years 5-7 (2030-2032): Consumer versions of devices coming to market. Regulatory approvals in other countries. Insurance coverage potentially starting.

Revenue: $100M-1B if things go well.

Cash burn: Potentially lower as revenue ramps.

For investors to see returns, Merge needs to hit multiple of these milestones. If clinical trials fail, if FDA approval doesn't come through, if the technology doesn't work as well in practice as in theory, the investment loses value.

But if everything works? If Merge develops a non-invasive brain-computer interface that's safe, effective, and scalable? The market opportunity could be enormous.

Estimates suggest there are:

- 5-6 million people in the US with severe motor paralysis (locked-in syndrome, ALS, complete spinal cord injury)

- 50+ million people with less severe motor dysfunction (stroke, partial paralysis, tremors)

- 100+ million people with mental health conditions that might benefit from neural intervention

Even penetrating just 1% of the severe market would be 50,000-60,000 devices. At

Penetrating broader markets could easily put the total addressable market in the $20-50 billion range.

The Ethical Questions Nobody's Talking About Yet

Here's what needs to be said clearly: brain-computer interfaces raise profound ethical questions that the industry hasn't fully addressed.

Access and equity. If these devices cost $50,000-100,000, who gets them? The wealthy? People with good insurance? This could deepen healthcare inequality. Merge's framing of wanting "broadly accessible" technology is good, but the economic reality is that medtech is expensive.

Privacy and mental security. If you can read someone's brain activity, what stops people from reading their thoughts? Privacy in the brain is a new kind of privacy we don't have legal frameworks for yet. What if an employer demands the device show your neural activity? What if law enforcement wants access?

Cognitive enhancement and fairness. If some people have AI-enhanced cognition and others don't, what does that mean for competition, education, employment? We're entering territory where cognitive ability becomes something you can buy.

Psychological dependence. If you use a brain-computer interface daily and it malfunctions, how much does that degrade your own cognitive abilities? If the AI starts predicting your thoughts and suggesting actions, how much agency are you actually exercising?

Long-term neural effects. We don't know if prolonged ultrasound exposure to brain tissue is completely safe. We don't know if the presence of a device causes inflammation or changes long-term neural function. These effects might take years or decades to appear.

Personhood and identity. If you can modify neural activity to treat depression or augment cognition, where's the line between treatment and enhancement? Between fixing problems and changing who you are?

Merge Labs will need to address these questions, not just technically but philosophically and ethically. The companies that handle this well will build trust. The ones that ignore it will face backlash.

Looking Forward: What Comes After Merge

Assuming Merge Labs succeeds—achieves FDA approval, scales manufacturing, and becomes the leading non-invasive brain-computer interface provider—what happens next?

The technology will probably follow the usual arc: expensive and specialized initially, becoming cheaper and more accessible over time.

First applications will be medical. Paralyzed patients. People with severe tremors. Locked-in syndrome patients. These have clear clinical justifications and regulatory pathways.

Then therapeutic applications. Mental health treatment. Addiction recovery. Cognitive rehabilitation after brain injury. Again, clear medical need.

Then enhancement. This is where it gets interesting and controversial. People without medical need choosing to augment their cognition. Athletes enhancing reaction time. Students improving memory. Workers increasing focus.

Eventually, if the technology becomes ubiquitous enough, there could be pressure for everyone to have one. Not because it's required, but because everyone else does. Social and professional pressure creating de facto mandates.

This progression isn't inevitable. Regulation could prevent some steps. Public resistance could slow adoption. But historically, technology follows this trajectory: medicine first, enhancement later, ubiquity eventually.

The devices will probably get smaller, more comfortable, and more naturalized. Maybe eventually an implant becomes preferable to ultrasound (ironically returning to surgery as the preferred option). Maybe integration with AR/VR glasses gives you brain interface + visual interface in one device. Maybe direct neural input becomes how most people interact with digital systems.

We might be looking at a world (50 years out, speculating wildly) where direct neural interfacing is as common as smartphones are now. Where asking someone "do you have a neural interface?" is like asking "do you have a phone?" Everyone says yes, or at least most people do.

Merge Labs is trying to build the infrastructure for that world. They might not be the final winner in the market, but they're positioned to be a major player.

The Bottom Line: Investment, Vision, and Reality

Merge Labs' $252 million funding, OpenAI partnership, and non-invasive ultrasound approach represent a genuine inflection point in neurotechnology.

They're not the only player pursuing brain-computer interfaces. Neuralink is further ahead with human implants. Synchron is well-funded and progressing methodically. But Merge has something potentially more valuable than speed: a different approach.

Non-invasive wins on accessibility. If it also works, if the AI-powered signal interpretation actually delivers on its promise, Merge could define the future of how humans interact with technology.

The timeline is measured in years, not months. Clinical trials will take 3-5 years minimum. FDA approval could take 5-7. Real scalable commercial deployment might be 7-10 years away. This isn't a quick win.

But the vision is clear, the team is credible, the capital is committed, and the market opportunity is enormous.

Merge Labs isn't just another startup raising venture capital. It's a bet that the future of human-AI interaction runs through the brain. That direct neural interfaces will become commonplace. That the merge between human and machine intelligence isn't a philosophical idea but an engineering problem waiting to be solved.

Whether they succeed or not, they've positioned themselves at exactly the right intersection of neuroscience, AI, and medicine at exactly the right moment. That alone makes them worth watching closely.

FAQ

What is Merge Labs?

Sam Altman's neurotechnology startup aims to develop non-invasive brain-computer interfaces using ultrasound technology. The company raised $252 million in funding from OpenAI, Bain Capital, and other investors to commercialize neural interfacing technology that doesn't require surgical implants.

How does Merge Labs' ultrasound technology work differently from Neuralink?

Merge uses ultrasound to detect blood flow changes in the brain rather than implanting electrodes. Neuralink's approach involves surgical implantation of electrode arrays directly into brain tissue. Ultrasound-based interfaces are non-invasive, reversible, and faster to deploy clinically, while electrode arrays offer higher signal quality but require surgery and carry infection risks.

What role does AI play in Merge's brain-computer interface?

OpenAI is collaborating with Merge to develop foundation models specifically trained on brain activity data. These AI systems learn to interpret noisy ultrasound signals from the brain and understand neural intent, enabling more intuitive and effective communication between the brain and computers or external devices.

When will Merge Labs' devices become available to the public?

Based on typical medical device timelines, clinical trials would occur 2025-2028, FDA approval 2028-2030, and commercial availability to patients 2030-2032. Consumer versions would likely follow several years later. The exact timeline depends on clinical trial results and regulatory processes.

What are the main applications Merge Labs is targeting?

Initial applications will likely focus on medical uses: restoring motor function in paralyzed patients (spinal cord injury, stroke, ALS), enabling communication for locked-in syndrome patients, and treating mental health disorders. Consumer applications for cognitive enhancement would follow once clinical success is proven.

How does Merge Labs' funding of $252 million compare to other brain-computer interface companies?

Neuralink has raised

What are the safety concerns with non-invasive ultrasound brain interfaces?

Long-term safety of sustained ultrasound exposure to brain tissue requires further study. Other considerations include ensuring devices don't cause unintended neural stimulation, preventing electromagnetic interference with the brain, and establishing proper calibration to avoid misinterpreting neural signals. These will be key focuses of clinical trials before FDA approval.

Could Merge's technology eventually replace keyboards and voice commands for computer interaction?

That's theoretically possible long-term, but practically unlikely in the near decade. Direct neural input has significant advantages for communication-limited patients (paralysis, locked-in syndrome) but would need dramatic improvements in safety, usability, and cost to replace conventional interfaces for able-bodied users. The first applications will be medical, with consumer enhancement applications coming much later.

How is Merge Labs addressing the ethical concerns around brain privacy?

Merge hasn't extensively published ethical frameworks yet, but the technology itself reduces some privacy risks compared to invasive implants (the device can be removed). Critical issues remain around data security, unauthorized neural data access, and fairness in access to cognitive enhancement. These will likely be addressed as the company scales and engages regulatory agencies.

What is "the merge" that gives Merge Labs its name?

"The merge" references Sam Altman's concept of human-machine intelligence integration, particularly his essays on the hypothetical point where humans and artificial intelligence become deeply integrated. Merge Labs aims to make this concept practical through non-invasive neural interfaces that enable direct communication between human brains and AI systems.

Key Takeaways

- Merge Labs raised $252M to develop non-invasive ultrasound brain-computer interfaces without surgical implants, differentiating from Neuralink's invasive approach

- OpenAI's direct partnership on foundation models signals major AI company commitment to neural interfaces as future of human-computer interaction

- Clinical trials likely 2025-2028, FDA approval 2028-2030, with commercial availability to patients by 2032 if everything proceeds on schedule

- Addressable market includes 5+ million severely paralyzed patients, 50M+ with motor dysfunction, and 100M+ with mental health conditions benefiting from neural intervention

- Non-invasive ultrasound approach trades slightly lower signal quality for dramatically better accessibility, reversibility, and faster regulatory pathway than implantable competitors

Related Articles

- OpenAI's $250M Merge Labs Investment: The Future of Brain-Computer Interfaces [2025]

- NAOX EEG Wireless Earbuds: Brain Monitoring Technology [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness Role: What It Means and Why It Matters [2025]

- OpenAI's New Head of Preparedness Role: AI Safety & Emerging Risks [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness Role: AI Safety Strategy [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness: Why AI Safety Matters Now [2025]

![Merge Labs: How Ultrasound Brain Tech Could Redefine Human-AI Integration [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/merge-labs-how-ultrasound-brain-tech-could-redefine-human-ai/image-1-1768502314313.jpg)