The Layoff Reality That Nobody Wants to Discuss

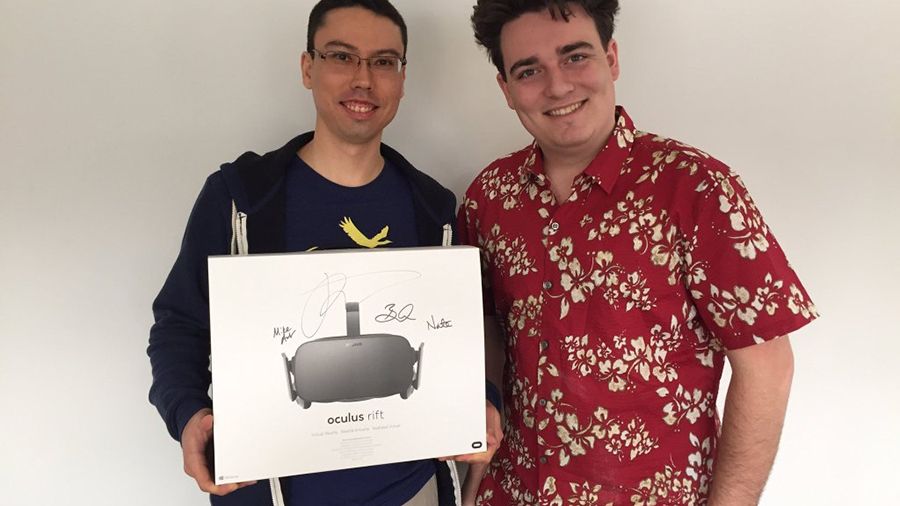

Palmer Luckey, the founder of Oculus, recently made headlines by claiming that Meta's significant VR layoffs shouldn't be viewed as a disaster. On the surface, that sounds like the kind of measured take you'd expect from someone who's deeply invested in the VR space. But here's the thing: when you actually dig into what's happening at Meta's Reality Labs division, it's hard not to see these cuts as anything other than a symptom of something much deeper.

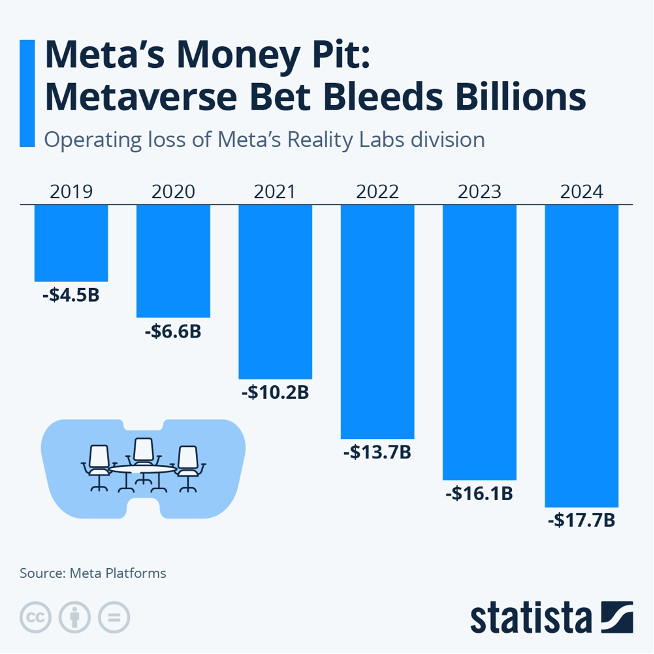

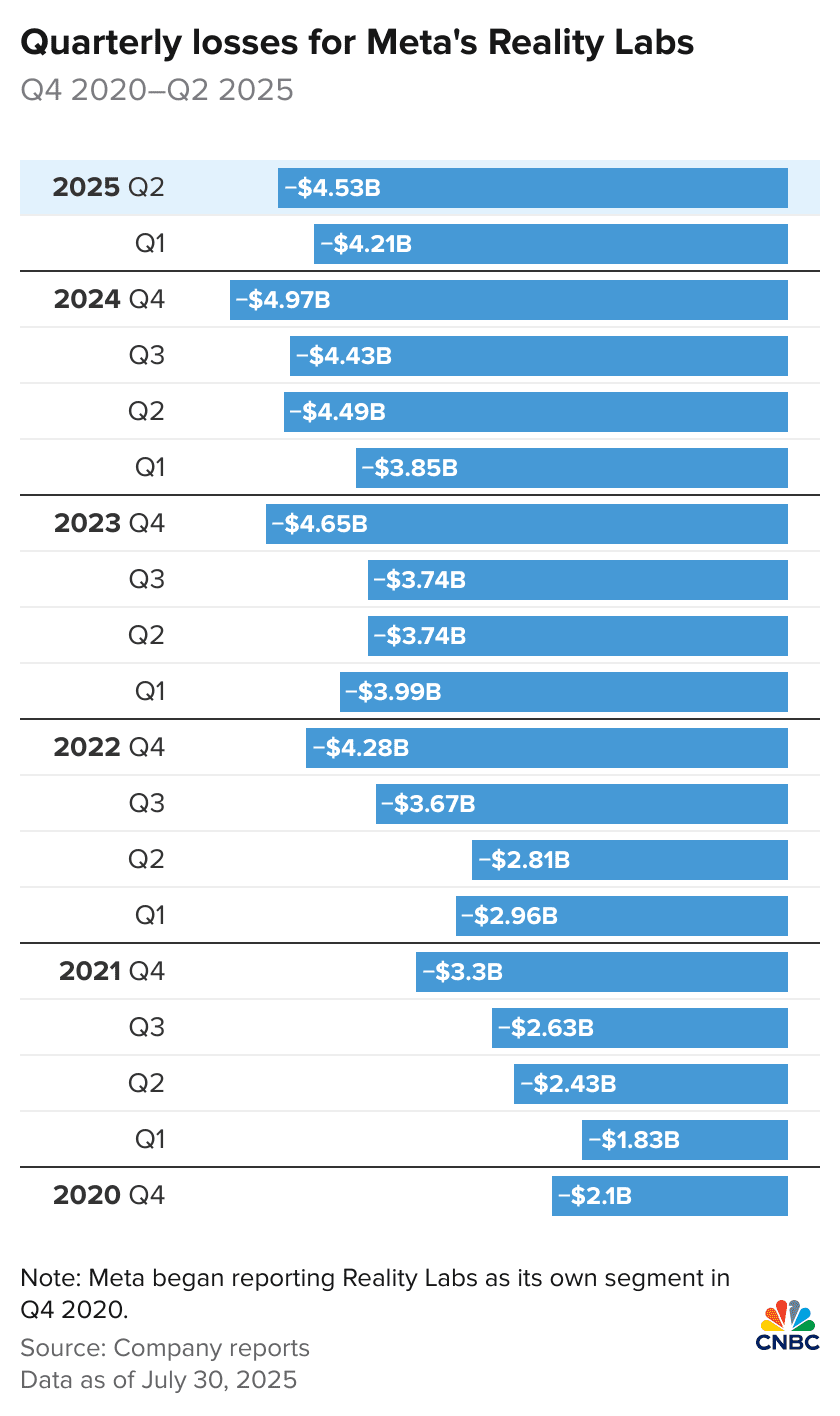

Meta's Reality Labs has been bleeding money for years. The division lost over $16 billion between 2020 and 2023, and those losses have continued into 2024. These aren't small, manageable numbers. These are the kind of figures that force companies to make hard decisions. When you're losing that much cash annually, layoffs aren't a sign of optimization—they're a sign of a fundamental misalignment between investment and return.

The VR industry promised us something incredible. It promised immersive experiences that would reshape how we work, play, and connect. A decade after the Oculus Rift's first consumer release, we're still waiting for that promise to materialize. Sure, we've got better headsets. Quest 3 is genuinely impressive hardware. But the applications that justify the expense? Those remain elusive.

Luckey's optimism makes sense from one perspective: he's been right about the long-term potential of VR before. He saw something in virtual reality when most people dismissed it as a gaming gimmick. But there's a difference between being right about a technology's eventual importance and being right about the timeline for profitability. The latter is where things get tricky for Meta.

Meta's Reality Labs: A Cautionary Tale of Ambition Without ROI

Let's talk numbers, because numbers don't lie and they certainly don't care about optimism. Meta's Reality Labs division represents one of the largest financial bets any company has made on an unproven technology. When Mark Zuckerberg announced the pivot toward the "metaverse" in late 2021, he was putting serious money behind it.

The layoffs we're discussing weren't small adjustments. Meta cut thousands of positions across the company, and Reality Labs felt the impact particularly hard. The question everyone's asking is: would Luckey be making these same optimistic statements if he were directly responsible for justifying these losses to shareholders?

Here's what makes this situation different from other major tech pivots. When companies like Google invested heavily in experimental projects, they had multiple cash cows generating revenue at scale. Google's search business and advertising networks could bankroll moonshots. Microsoft took decades to make Xbox profitable. But Meta's situation is different because its core advertising business has been under pressure from Apple's privacy changes and increased competition from Tik Tok.

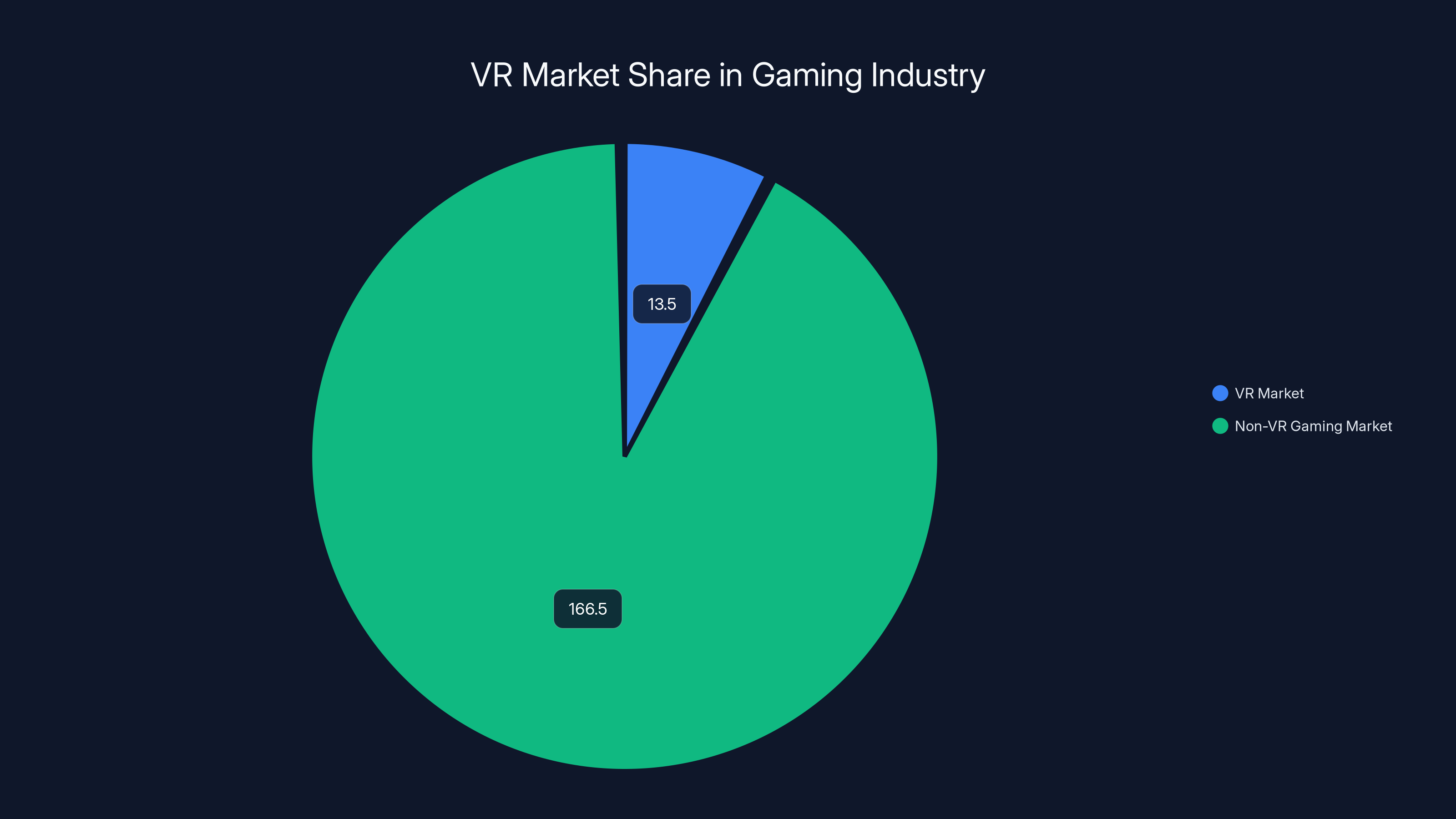

The VR industry has spent fifteen years proving that adoption curves don't follow the patterns that early enthusiasts predicted. Remember when everyone thought VR arcades would explode into the mainstream? Or when VR social platforms would replace social media? These predictions were made by smart people with genuine expertise. Yet here we are, with VR still occupying a niche market despite massive investment.

Meta's problem isn't that the company lacks capability. Meta can build hardware. Meta understands software. Meta has the resources to throw at problems that most companies couldn't touch. The problem is that Meta has been trying to force a market that clearly isn't ready to adopt VR at scale. The company created hardware solutions searching for killer applications instead of the other way around.

Meta's VR division has consistently lost billions annually, totaling an estimated $16 billion over four years. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

The Developer Exodus: Where the Real Damage Lies

When companies lay off employees, the immediate financial impact is real. But the long-term damage often comes from something harder to quantify: the loss of expertise, momentum, and institutional knowledge. For VR, this is particularly damaging.

VR development requires specialized skills. You can't just hire any software engineer and have them become a VR expert overnight. The people who've spent years building immersive experiences, optimizing for motion sickness, creating compelling spatial interfaces—these are rare talents. When Meta lays off VR developers, those people scatter to other industries or other companies. Some go to AI. Some go back to traditional gaming. Some leave tech entirely.

The problem compounds because VR development is already a challenging field. You're building for multiple hardware platforms. You're pushing the boundaries of what's technically possible. You're working on problems that most other software engineers haven't encountered. The people who stick with it are passionate about the technology itself, not just the paycheck.

When Meta signals through layoffs that it's no longer as committed to VR as it once was, it changes the narrative. Why would a young developer choose to specialize in VR development when the person who literally invented the modern VR headset is saying layoffs aren't a big deal? They wouldn't.

This is the exodus that worries people who actually understand the industry. It's not about this quarter's budget numbers. It's about whether the infrastructure for VR development will still exist five years from now when Meta might actually have figured out what people want.

Meta's Reality Labs division has consistently lost billions annually, with estimated losses peaking in 2022. Estimated data.

Why Consumer Adoption Remains the Core Problem

Let's look at the fundamental issue that no amount of optimism can wish away: consumers still don't want VR the way Meta hoped they would. This isn't a failure of marketing or a matter of patience. This is a failure of the product-market fit equation.

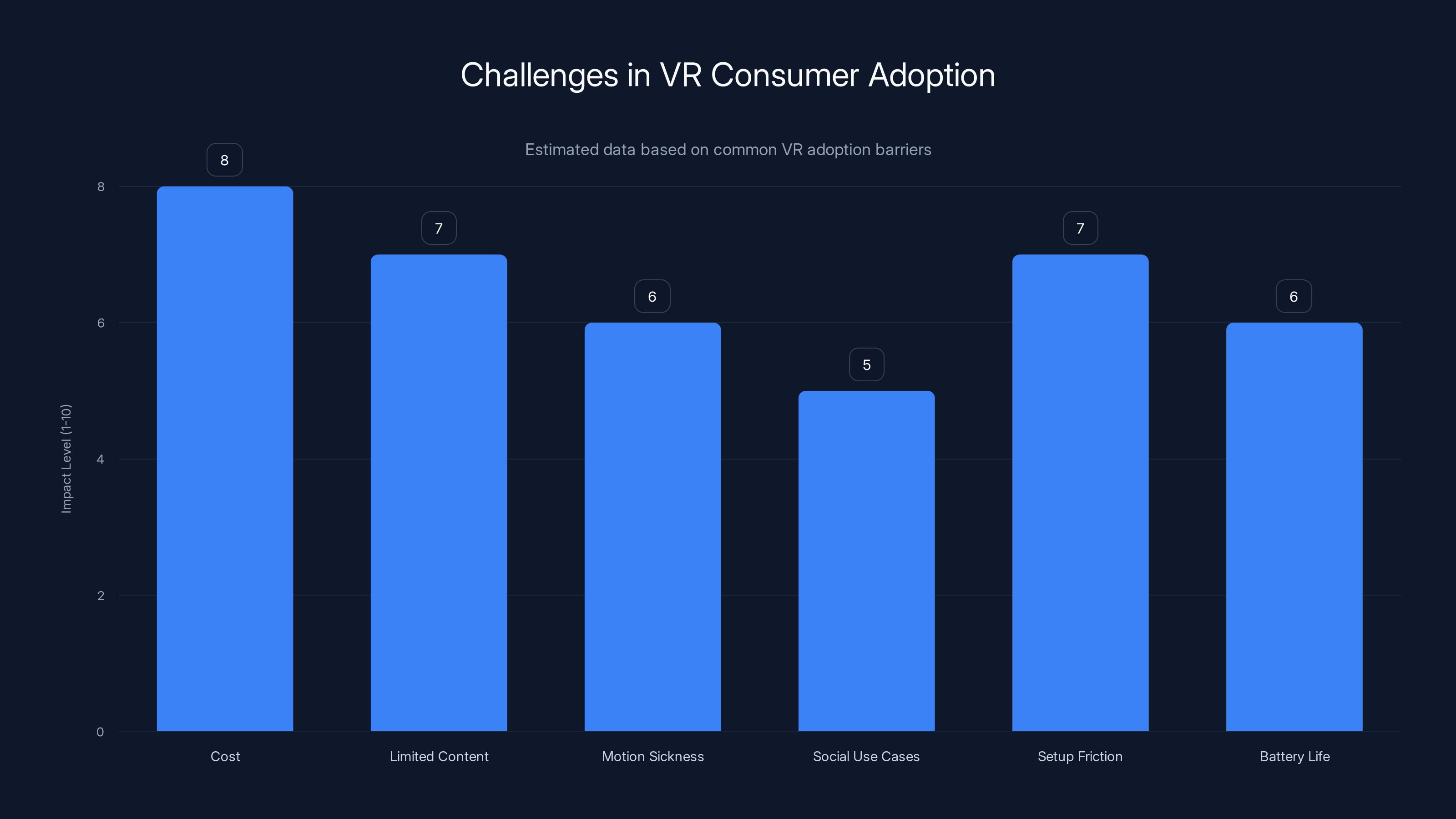

VR headsets are expensive. Quest 3 starts at $500, which is a reasonable price point for tech enthusiasts but represents a serious financial commitment for casual consumers. VR games are expensive. VR content is still limited compared to traditional gaming. And perhaps most importantly, the social use case for VR—the metaverse dream that drove all of this—remains fundamentally unconvincing to most people.

We've had a decade of VR development. We've had smart people building amazing experiences. We've had mainstream companies investing billions. Yet most people who try VR don't become VR enthusiasts. They try it, they're impressed for a few minutes, and then they don't use it again.

This isn't because VR technology isn't good enough. Modern VR hardware is genuinely impressive. The resolution is high. The tracking is accurate. The controllers are responsive. The problem is that VR, as currently implemented, has some fundamental limitations that no amount of development can overcome in the near term.

Motion sickness remains an issue for a significant portion of the population. Social VR experiences are awkward because you can't see people's hands well enough. The requirement to clear a play space and wear a headset creates friction for casual use. Battery life on wireless headsets is limited. The heat from wearing a headset for extended periods is uncomfortable.

None of these are insurmountable problems. But they're also not problems that you solve by laying off developers and cutting budgets. You solve them by doubling down on research. Yet Meta is moving in the opposite direction.

The Competitive Landscape: Where Meta Stands

Meta isn't the only company betting big on VR. Apple entered the market with Vision Pro, a $3,500 headset that positions itself as a premium spatial computing device rather than a VR headset. Microsoft is pursuing augmented reality with Holo Lens. Sony released Play Station VR2. Valve is continuing to support their Index headset. HTC Vive maintains its presence in enterprise VR.

But here's what's interesting: most of these companies are moving away from the "VR for everyone" narrative that Meta was pushing. They're either positioning VR as enterprise infrastructure, gaming hardware, or premium consumer devices. Meta was the one betting that VR would become as ubiquitous as smartphones.

Apple's approach is instructive. Apple didn't try to make VR cheap and accessible. Apple made VR expensive and exclusive, positioning it as the next computing platform for people who can afford premium devices. Early sales data suggests this is a much more honest framing of where VR sits in the market.

Meanwhile, Meta is cutting back on the very investments that might have justified the original bet. This creates a weird situation where Meta is simultaneously saying that VR is important long-term while also acknowledging that it needs to reduce spending in the space. These two things are hard to reconcile.

Cost and limited content are the top barriers to VR adoption, with setup friction and motion sickness also significantly impacting consumer interest. Estimated data.

The Metaverse Dream: Where Reality Diverged from Vision

Two years ago, Mark Zuckerberg was talking about the metaverse as the inevitable future of the internet. Every earnings call included references to building the metaverse. Every strategic decision was justified through the lens of metaverse infrastructure. Yet here we are, and the metaverse narrative has almost completely disappeared from Meta's official communications.

This is significant. When companies quietly stop talking about something they were obsessed with, it usually means one of two things: either they've made progress and don't need to talk about it anymore, or they've failed and want to move on. In this case, it's clearly the latter.

The metaverse failed not because the technology wasn't good enough, but because the fundamental premise was wrong. People don't want to hang out with cartoon avatars in empty virtual spaces. People don't want to attend meetings in virtual offices that are less functional than Zoom. People don't want to buy virtual real estate with real money.

Meta bet the company on this vision. Zuckerberg was so convinced that he literally renamed the company from Facebook to Meta to signal his commitment. He went on record saying that the metaverse was more important than current products. He invested tens of billions in the bet.

And it didn't work.

The layoffs are what happens when you finally admit that your bet didn't pay off. The numbers don't lie. Reality Labs losses are documented in SEC filings. The user numbers for Meta's VR platforms aren't anywhere near what would justify the investment. The enterprise applications haven't materialized the way executives hoped.

Why Luckey's Optimism Might Be Misplaced

Palmer Luckey is an intelligent person with genuine vision. His track record of correctly identifying VR's potential is impressive. But there's a difference between being right about the long-term importance of a technology and being right about the timeline for mainstream adoption.

Luckey's optimism seems to rest on the assumption that VR is inevitably going to become mainstream once the technology improves enough. But this ignores a crucial point: the technology is already quite good. Quest 3 is a genuinely capable device. The problem isn't technology maturity. The problem is consumer demand.

When your core issue is demand-side, not supply-side, throwing more engineering resources at the problem doesn't help. Meta doesn't need better VR hardware. Meta needs a reason why normal people would want to use VR headsets.

Luckey might be right that VR has a future. But he might be wrong about the timeline. He might be wrong about the form factor. He might be wrong about the killer application. And he might be wrong about who should be leading the space if VR does finally break through to mainstream adoption.

Consider that many of the most important computing shifts didn't happen on the timeline that early advocates predicted. The internet took longer to become mainstream than 1990s pundits expected. Mobile computing took longer than 2000s predictions suggested. Artificial intelligence is taking longer to deliver on its most ambitious promises.

Being right about a technology's eventual importance is different from being right about when it matters. The layoffs suggest that Meta's leadership has internally decided that the VR timeline is longer than the company's financial situation can support. That's a damning assessment from the largest investor in VR technology.

Despite decades of development, the VR market represents less than 10% of the overall gaming industry, highlighting its niche status.

The Enterprise VR Question: A Bright Spot That Still Needs Work

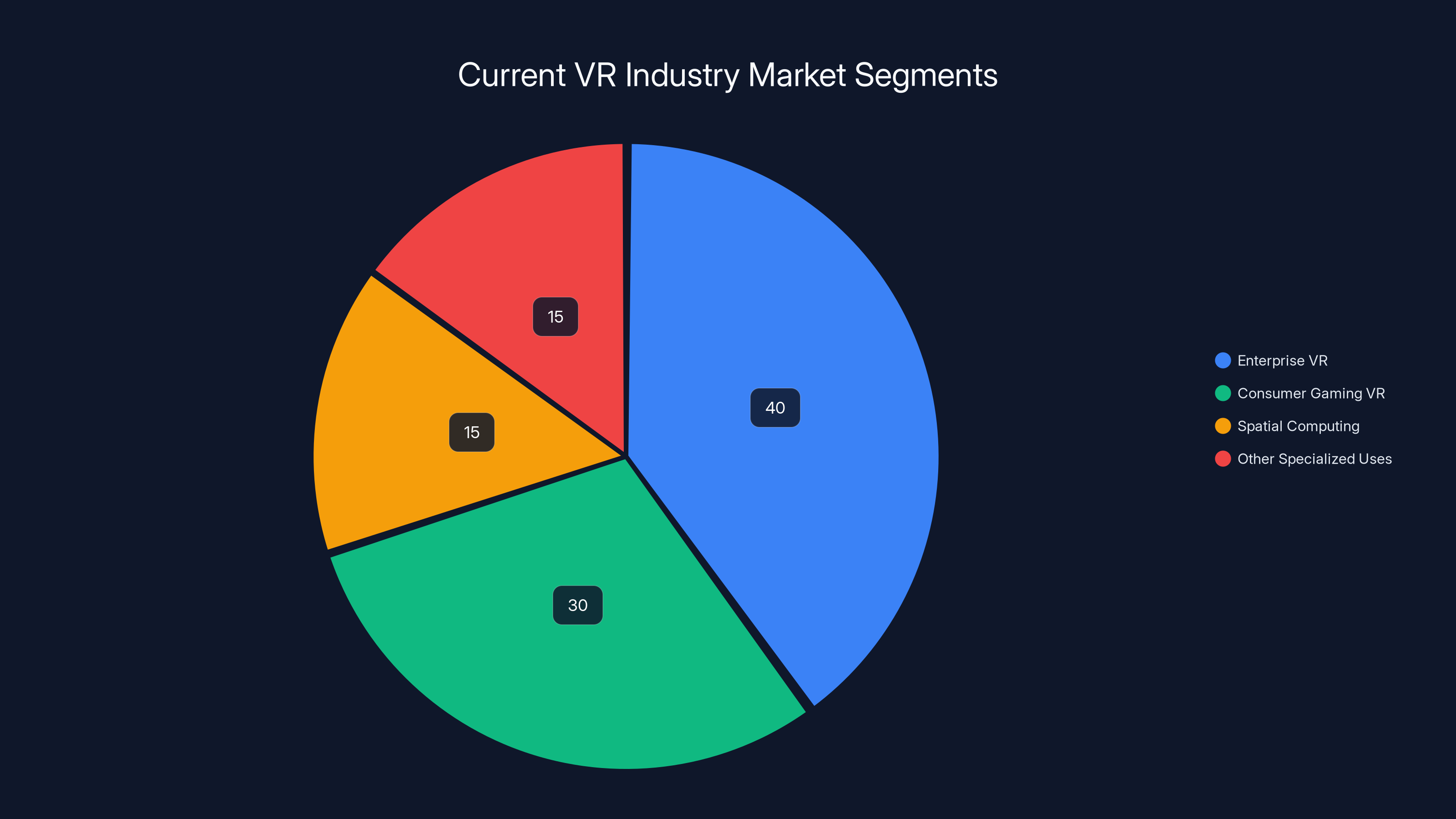

If there's a silver lining to the VR situation, it's in enterprise applications. Industrial VR, medical VR, architectural visualization, and training simulations all have clear use cases and demonstrable ROI.

Companies are using VR for training pilots, soldiers, and surgeons. Architects are using VR to visualize building designs before construction. Engineers are using VR to collaborate on complex projects. These are real applications with real value propositions.

Meta's layoffs didn't spare enterprise VR. In fact, enterprise teams felt the cuts pretty deeply. This is where Meta's strategy becomes questionable. If consumer VR has failed to justify the investment, the logical move would be to double down on enterprise VR, where there's clear demand and clear ROI.

Instead, Meta is cutting across the board. This suggests that Meta's leadership has decided to de-emphasize VR more broadly, whether consumer or enterprise. That's a strategic choice, but it's hard to characterize it as anything other than a pullback.

Enterprise VR will continue to develop and improve. But it will do so at a slower pace if Meta, the largest private investor in VR technology, is no longer funding the space aggressively. The developer talent that would have built the next generation of enterprise VR tools will scatter to other industries.

Hardware vs. Software: Where Meta's Strategy Falls Apart

Meta's VR strategy has been primarily hardware-focused. The company builds Quest headsets and invests in improving the hardware. But hardware alone doesn't create a thriving ecosystem.

Think about gaming consoles. Play Station and Xbox succeed not because they have the best hardware, but because they have the best games. The software drives hardware adoption, not the other way around.

Meta never solved the software problem for VR. The company created hardware searching for killer apps instead of investing in developers who could create those apps. Meta's approach was to build the headset and hope that independent developers would fill the gap with compelling experiences.

But independent developers won't invest time in a platform with questionable long-term viability. If Meta is laying off thousands of VR employees, why would an indie developer bet their career on building VR games?

This is where the strategy breaks down. Meta needed a portfolio of software experiences compelling enough to drive hardware adoption. Instead, Meta built headsets and hoped the software ecosystem would spontaneously emerge. When it didn't, Meta decided the problem was with the consumers, not the strategy.

Apple's approach with Vision Pro is instructive again. Apple is working with major development studios to ensure that compelling software exists before full market launch. Apple is also using Apple's own software—improvements to OS-level features, integration with Mac and i Pad—to create reasons to use the device.

Meta's Quest software ecosystem still feels like a collection of tech demos rather than genuinely useful or compelling applications. After a decade of development, that shouldn't be the case.

Enterprise VR leads the market focus with 40%, followed by consumer gaming VR at 30%. Spatial computing and other specialized uses each hold 15%. (Estimated data)

The Financial Pressure: What the Numbers Really Tell Us

Meta's decision to lay off VR employees isn't driven by philosophical arguments about the future of technology. It's driven by financial pressure. Meta faces several challenges that make the massive VR losses harder to justify.

Apple's dominance in the smartphone market means Meta's most valuable revenue stream—mobile advertising—faces pressure as Apple's privacy changes limit Meta's ability to target users. Tik Tok's growth has created a new competitor for user attention and advertising dollars. The AI arms race requires massive capital investment.

In this context, losing $16 billion over four years on a division with no clear path to profitability becomes harder to justify. Shareholders are asking questions. Investors are demanding returns. The financial markets are scrutinizing Meta's spending.

Luckey's optimism sounds nice, but it doesn't show up on balance sheets. It doesn't satisfy shareholders. It doesn't justify the continued allocation of capital to a money-losing division.

This is where Luckey's perspective breaks down. He can be optimistic about VR's eventual importance because his track record and credibility give him the privilege of believing in long-term bets. But Meta's CFO can't. Meta's board can't. Shareholders demand that companies generate returns.

Meta is a public company with a responsibility to generate profits for shareholders. The company has decided, implicitly if not explicitly, that VR won't generate meaningful returns in a timeline that matters to today's shareholders.

That decision might be wrong. VR might break through five years from now. But from a financial perspective, it's completely rational. You don't keep investing heavily in a division that's losing $16 billion over four years when you have more promising opportunities.

Comparing VR to Other Failed Tech Bets

History gives us perspective on what happens when major tech companies make billion-dollar bets on unproven technologies. Google Glass. Second Life. 3D televisions. Kinect. Each of these seemed promising to people deeply invested in the technology. Each received significant capital investment. Each ultimately failed to justify the expense.

Google Glass seemed like a logical progression from smartphones. Augmented reality, wearable computing, always-on connectivity—these are all things that eventually will matter. But Glass failed because the execution didn't match the vision. Privacy concerns. The devices looked ridiculous. The battery life was terrible. The software ecosystem was nonexistent.

Second Life attracted millions of users and massive investment. People built businesses inside the virtual world. Major companies opened virtual stores. But it peaked and then declined because people realized that virtual worlds without a specific purpose weren't that interesting.

3D televisions seemed like the inevitable future of television. Manufacturers invested billions in developing the technology. Broadcasters created content. And then consumers collectively decided they didn't want to wear glasses to watch TV. The technology was fine. The consumer demand simply wasn't there.

Kinect for Xbox was an impressive piece of motion sensing technology. It sold millions of units. But it failed as a gaming input device because controllers are actually better for gaming. The technology was good. The use case was wrong.

VR might follow a similar pattern. The technology is good. The use cases are just not there at scale. Palmer Luckey believes VR will eventually matter. He's probably right. But that doesn't mean Meta was right to invest $16 billion in proving that point.

What Comes Next: The VR Industry's Path Forward

The VR industry isn't dead. But it's being redefined. After Meta's layoffs, the industry is likely to consolidate around a few specific use cases rather than pursuing the "VR for everyone" vision that Luckey and Zuckerberg were selling.

Enterprise VR will continue to develop. Companies like Varjo, which makes high-end VR systems for professional use, will continue to find customers. Medical training, industrial simulation, and architectural visualization will remain viable markets.

Consumer VR will likely continue as a gaming niche. Play Station VR2 will serve console gamers who want immersive gaming. PC VR will serve hardcore gamers. Standalone headsets like Quest will serve people who specifically want portable VR experiences.

Apple's Vision Pro will explore the space of spatial computing devices, though early sales data suggests the market for $3,500+ devices is tiny.

But the grand vision of VR as the next computing platform? That's gone. That vision required massive investment from major technology companies. Meta's layoffs signal that at least one major player is no longer funding that vision.

Will VR eventually become important? Probably. But maybe not for another 10-15 years. Maybe not in the form factor we're currently building. Maybe in ways that current companies aren't anticipating. In the meantime, VR will exist as a specialized tool for specific purposes, not as a revolutionary new computing paradigm.

Luckey's optimism about VR's long-term future is probably justified. But optimism about long-term potential is cold comfort to developers losing their jobs, startups losing their market direction, and companies that bet billions on a timeline that turned out to be wrong.

The Credibility Problem: Why Trust Matters More Than Technology

Here's something that often gets overlooked in the VR discussion: credibility. Palmer Luckey has tremendous credibility as a VR expert. He literally invented the modern VR headset. His opinions matter because his track record has been good.

But saying layoffs aren't a disaster while those same layoffs are happening is a credibility issue. It's hard to believe that someone thinks a situation isn't a disaster when they're not working to prevent the disaster. If layoffs truly aren't a disaster, why didn't Luckey offer to fund additional VR development? Why didn't he move to a more prominent role in the VR ecosystem? Why did he largely fade from public commentary?

Instead, Luckey's optimism about VR's future comes with a subtext: "I still think VR is important, but I'm not willing to bet my current resources on it." That's a credibility problem.

When experts start qualifying their enthusiasm, when they offer optimistic statements while their actions suggest caution, it's a red flag. The market eventually notices these signals.

Meta's layoffs were justified by leadership as strategic efficiency improvements. But the optics matter. The message being sent to the VR industry is that Meta is retreating. That might not be the intended message, but it's the message being received.

Where We Stand: An Honest Assessment

Palmer Luckey is right that VR has long-term potential. VR technology will eventually be important. Immersive experiences will eventually be a significant part of how humans interact with information and with each other.

But Luckey is also wrong about something crucial: the timing and the path. The layoffs do indicate something negative. They indicate that Meta's leadership has decided that the consumer VR timeline is longer than the company's financial situation can support. They indicate that the metaverse bet failed. They indicate that VR won't be the next computing platform in a way that matters to today's investors and consumers.

These aren't minor points. These are foundational issues that the VR industry needs to grapple with. The largest private investor in VR technology has decided to significantly reduce its commitment. That's not a disaster in the sense that it marks the end of VR technology. But it is a disaster in the sense that it signals a fundamental reassessment of VR's near-term viability.

The question going forward is whether VR can develop meaningful use cases and markets without the kind of massive capital investment that Meta was providing. Some analysts think yes. Others are less sure.

What's certain is that the narrative around VR has changed. The industry is no longer riding the wave of "VR is the inevitable future." The industry is now in the position of having to justify its existence through concrete use cases and sustainable business models. That's a harder path, but it might ultimately be a healthier one.

FAQ

What exactly caused Meta's Quest VR layoffs?

Meta's Reality Labs division has lost over $16 billion between 2020 and 2023, with continued losses through 2024. The company faced increased financial pressure from stagnating mobile advertising revenue, competition from Tik Tok, and the failure of its metaverse vision to gain consumer traction. The layoffs were a strategic response to unsustainable losses in a division with no clear path to profitability.

Is Palmer Luckey still involved with Meta's VR efforts?

No. Palmer Luckey left Meta in 2017 following a period of reduced involvement. His recent statements about the layoffs being "not a disaster" were commentary from outside the company, not statements as a current employee. Luckey founded Anduril Industries, a defense technology company, and has not been directly involved with Meta's VR strategy in years.

How many employees did Meta lay off from Reality Labs?

Meta's total company layoffs in late 2024 affected approximately 10% of its workforce, which amounts to thousands of employees across divisions including Reality Labs. The VR division experienced particularly deep cuts, though Meta did not release specific numbers exclusively for Reality Labs.

What does Palmer Luckey mean when he says the layoffs aren't a disaster?

Luckey's statement suggests that while the layoffs are painful and represent a strategic pullback, they shouldn't be viewed as evidence that VR technology is fundamentally flawed or that VR will never be important. His argument seems to be that VR's long-term potential remains intact even if Meta's short-term commitment is reduced. However, this optimism is difficult to reconcile with Meta's actions.

Could VR still become mainstream after Meta's reduced investment?

It's possible, but less likely. Meta was the primary private sector driver of consumer VR development. With Meta reducing investment, VR development will slow significantly unless other companies (Apple, Sony, etc.) dramatically increase their commitment. The technology has potential, but the path to mainstream adoption is now much less certain.

Why is Meta cutting VR budgets if the company believes in long-term potential?

Meta faces competing financial pressures. The company must invest in artificial intelligence, maintain its core advertising business against competition, and generate returns for shareholders. When a division loses $16 billion over four years with no clear profitability timeline, continuing to fund it becomes increasingly difficult to justify. The layoffs represent a choice to allocate resources differently rather than a complete abandonment of VR.

What are the remaining VR use cases that still matter?

Enterprise VR remains viable for training simulations, medical applications, and professional visualization. Gaming VR continues to serve enthusiasts through Play Station VR2 and PC-based systems. However, the grand vision of VR as a replacement for personal computing or as a social platform has been significantly scaled back.

How does Apple's Vision Pro strategy differ from Meta's approach?

Apple positioned Vision Pro as a premium spatial computing device starting at

Will VR headset companies survive without Meta's investment?

Some will. Companies focused on high-end professional VR (Varjo, HTC Vive Enterprise) have sustainable business models. Gaming-focused VR will continue through Sony and enthusiast PC gamers. However, consumer VR development and innovation will likely slow considerably without Meta's massive R&D investment and market development efforts.

What would need to happen for VR to achieve mainstream adoption?

A killer application that makes VR indispensable for non-gaming purposes. Better form factors that don't require headsets. Significant improvements in comfort and social usability. Or a shift in consumer preferences toward immersive experiences. None of these seem imminent despite years of development. The technology is ready; consumer demand is the actual constraint.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's Reality Labs division has lost over $16 billion since 2020 with no clear profitability timeline

- Consumer VR adoption has remained stagnant despite massive investment, concentrated mainly in gaming enthusiasts

- The metaverse vision that drove Meta's pivot failed to generate meaningful user engagement or economic value

- VR development will likely consolidate around enterprise use cases rather than achieving mainstream consumer adoption

- Palmer Luckey's optimism about VR's future doesn't align with Meta's actions, signaling internal doubt about near-term viability

Related Articles

- Meta's Reality Labs Layoffs: What It Means for VR and the Metaverse [2025]

- Meta Kills Workrooms VR Meetings: What It Means for Remote Work [2025]

- Meta's VR Studio Shutdowns: What Happened to Reality Labs [2025]

- Meta's Horizon Workrooms Shutdown: Why VR Meeting Rooms Failed [2025]

- LEGO Smart Brick: Inside the Best-in-Show Demo at CES 2026 [2025]

- Meta's VR Fitness Collapse: What Supernatural Users Lost [2025]