Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]

When Attorney General Raúl Torrez filed suit against Meta in December 2023, he wasn't making headlines for the typical antitrust angle everyone's used to hearing. This was different. He alleged that Meta didn't just fail to protect minors on Facebook and Instagram — he claimed the company actively served explicit content to kids, enabled predators to hunt on its platform, and made it trivially easy to find child sexual abuse material.

Now, that case is in a Santa Fe courtroom. And it's happening at exactly the moment when social media companies are facing their most serious legal reckoning in years.

Here's the thing: this isn't theoretical debate anymore. A jury is hearing evidence. Lawyers are cross-examining witnesses. And Meta, for the first time in a major standalone state case, is actually going to trial instead of settling.

The New Mexico trial matters because it's the first shot. It's the first state-led child safety case against Meta to actually reach a jury. Before this, you had scattered settlements, regulatory actions, and the FTC's monopoly case that focused on business practices, not child harm. But this trial is asking a completely different question: Did Meta knowingly create conditions that allowed children to be sexually exploited on its platforms?

The stakes are enormous, not just for Meta, but for how regulators and courts think about social media design, algorithmic amplification, and corporate responsibility. A loss here could reshape how platforms approach child safety. A win for Meta could signal that tech companies have significant legal cover under existing laws.

Let's break down what's actually happening, what the allegations look like, and why this moment matters so much.

TL; DR

- The Case: New Mexico is suing Meta for allegedly failing to protect minors from sexual exploitation on Facebook and Instagram, claiming the company violated state consumer protection laws.

- Key Allegations: Meta allegedly served explicit content to underage users, enabled predators to identify and exploit children, and made it easy to find child sexual abuse material on its platforms.

- Legal Significance: This is the first standalone, state-led child safety case against Meta to reach trial in the United States, setting a precedent for future litigation.

- What's at Stake: A ruling against Meta could force dramatic changes to algorithmic design, content moderation, and how platforms prioritize child safety over engagement metrics.

- Timing: The trial coincides with a landmark addiction case in California, creating what observers call "the trial of a generation" for tech accountability.

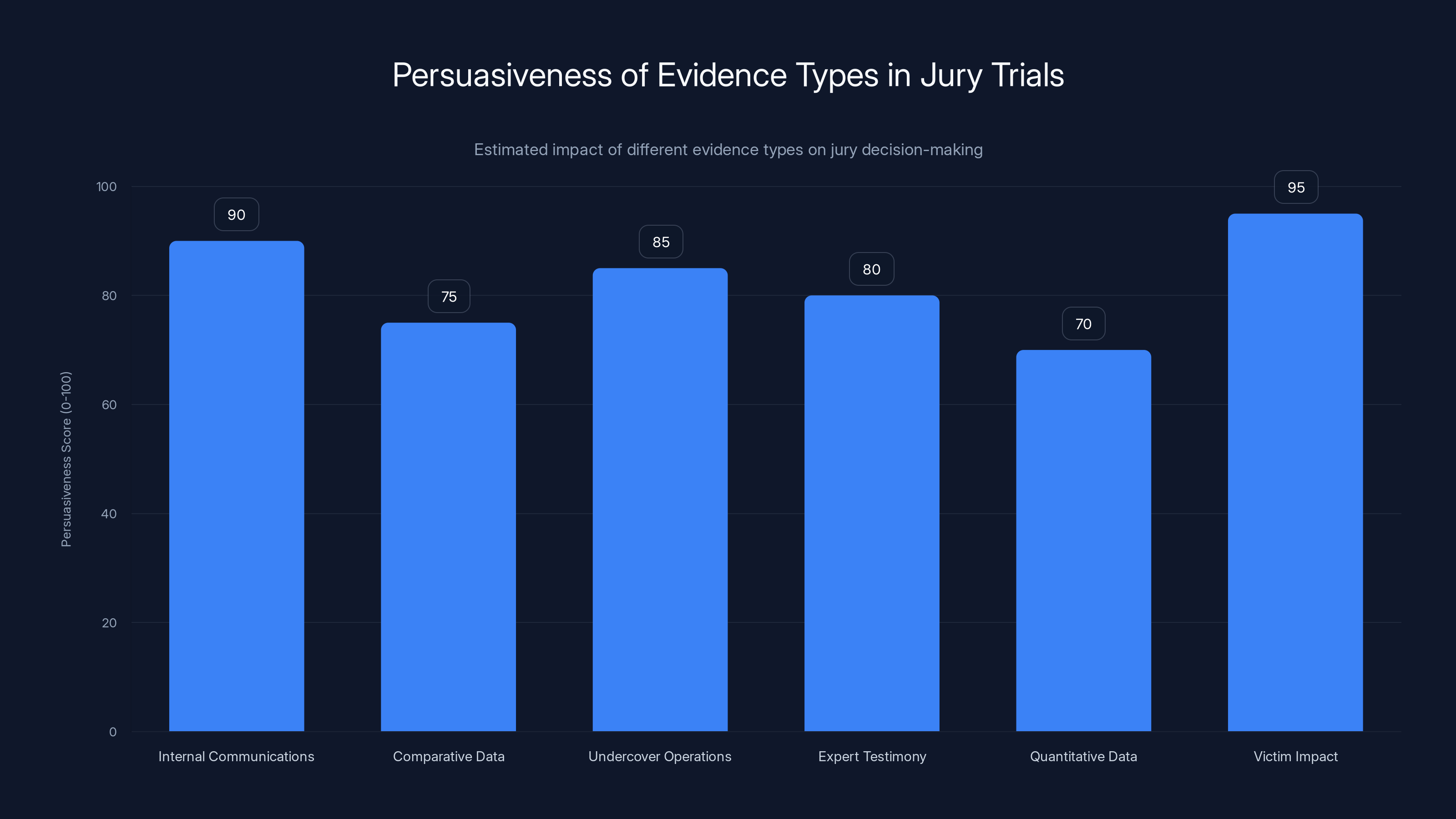

Victim impact and internal communications are estimated to be the most persuasive evidence types for juries, highlighting emotional and knowledge-based arguments. Estimated data.

The New Mexico Lawsuit: What Exactly Is Meta Being Accused Of?

Let's get specific about what New Mexico's complaint actually alleges. This isn't vague language. The filings detail concrete behaviors.

Torrez claims that Meta engaged in unfair and deceptive practices that violated New Mexico's Unfair Practices Act. But unfair practices in the context of a social media platform means something very particular: the company allegedly designed its systems to create exploitable conditions for minors.

The complaint alleges that Meta:

- Proactively served explicit content to underage users without meaningful age verification or content filtering

- Enabled adults to identify and target minors through features that made it easy to discover children and establish contact

- Allowed users to easily locate child sexual abuse material on both Facebook and Instagram

- Failed to respond adequately to complaints from users and third parties who reported abuse and exploitation

- Prioritized engagement metrics over safety, designing algorithms that amplified harmful content because it drove user interaction

One specific allegation is particularly striking. An investigator who posed as a mother was able to offer her purported underage daughter to sex traffickers on Meta's platform without the company taking meaningful action. The complaint describes this as evidence that Meta's safety mechanisms were either non-functional or deliberately under-resourced.

This framing is crucial. New Mexico isn't just saying Meta failed to catch some bad actors. The allegation is that the design of Meta's platforms — the features, the algorithms, the moderation systems — created the conditions where exploitation could happen at scale.

Why This Case Is Different From Previous Meta Litigation

Meta's faced lawsuits before. Lots of them. Antitrust cases, privacy cases, cases alleging monopolistic behavior. The FTC's case against the company, arguing it should divest Instagram and WhatsApp, was considered the most existential threat in years. But Meta won that one.

So what makes New Mexico different?

First, it's a standalone case focused entirely on child safety, not competition or monopoly behavior. The FTC cases and previous state actions have typically focused on business practices: market dominance, acquisitions, data practices. New Mexico is focused on direct harm to consumers.

Second, it's actually going to trial. Settlement is the norm in these cases. Companies pay fines, agree to policy changes, move on. But Meta hasn't settled New Mexico. The company is fighting this one completely.

Third, the evidentiary focus is unusual. Previous cases involving social media and minors typically centered on mental health harms — depression, anxiety, eating disorders, body image issues. The New Mexico case has mental health concerns in the background, but the primary focus is exploitation. Physical safety. Predation. These are allegations that resonate differently with juries than abstract concerns about algorithmic effects on teenage self-esteem.

Fourth, the legal theory leans heavily on unfair and deceptive practices laws that have been around for decades. This isn't new legal territory like some AI regulation attempts. Unfair practices acts exist specifically to protect consumers from being misled by businesses. The question is whether Meta's representations about safety stand up when confronted with evidence of how the platform actually functions.

The Trial Structure and Key Players

The trial is expected to run for seven weeks. That's substantial. Complex antitrust cases sometimes take longer, but seven weeks for a single state case signals that both sides are preparing for a genuine fight.

Judge Bryan Biedscheid of the New Mexico First Judicial District is presiding. The jury consists of ten women and eight men (twelve jurors plus six alternates). The gender composition might matter here. Research consistently shows that juries with women tend to take child safety allegations more seriously, and women are statistically more likely to rule in favor of plaintiffs in cases involving exploitation and harm to children.

Meta brought in outside counsel from Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick, a Washington DC litigation firm with serious credentials. This same firm successfully defended Meta against the FTC's antitrust case. So Meta's betting on the team that's already beaten the government's best shot.

On New Mexico's side, Attorney General Torrez is leading the case. Torrez has been relatively aggressive on tech regulation issues, which is notable because many state attorneys general treat tech litigation as lower priority than other enforcement actions.

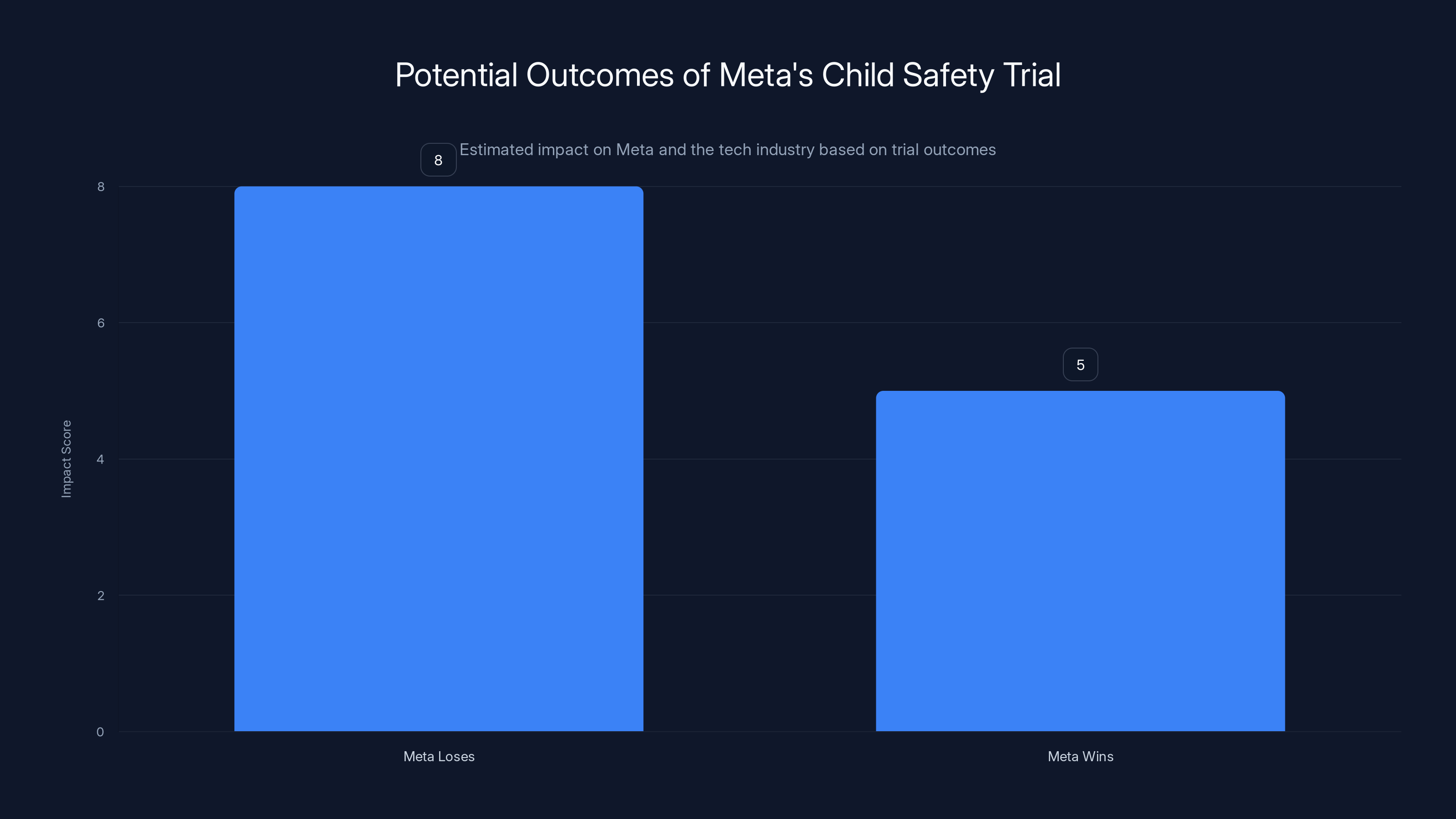

Estimated data suggests that a loss for Meta could have a significant impact on the company and the tech industry, potentially leading to rapid regulatory changes and other lawsuits.

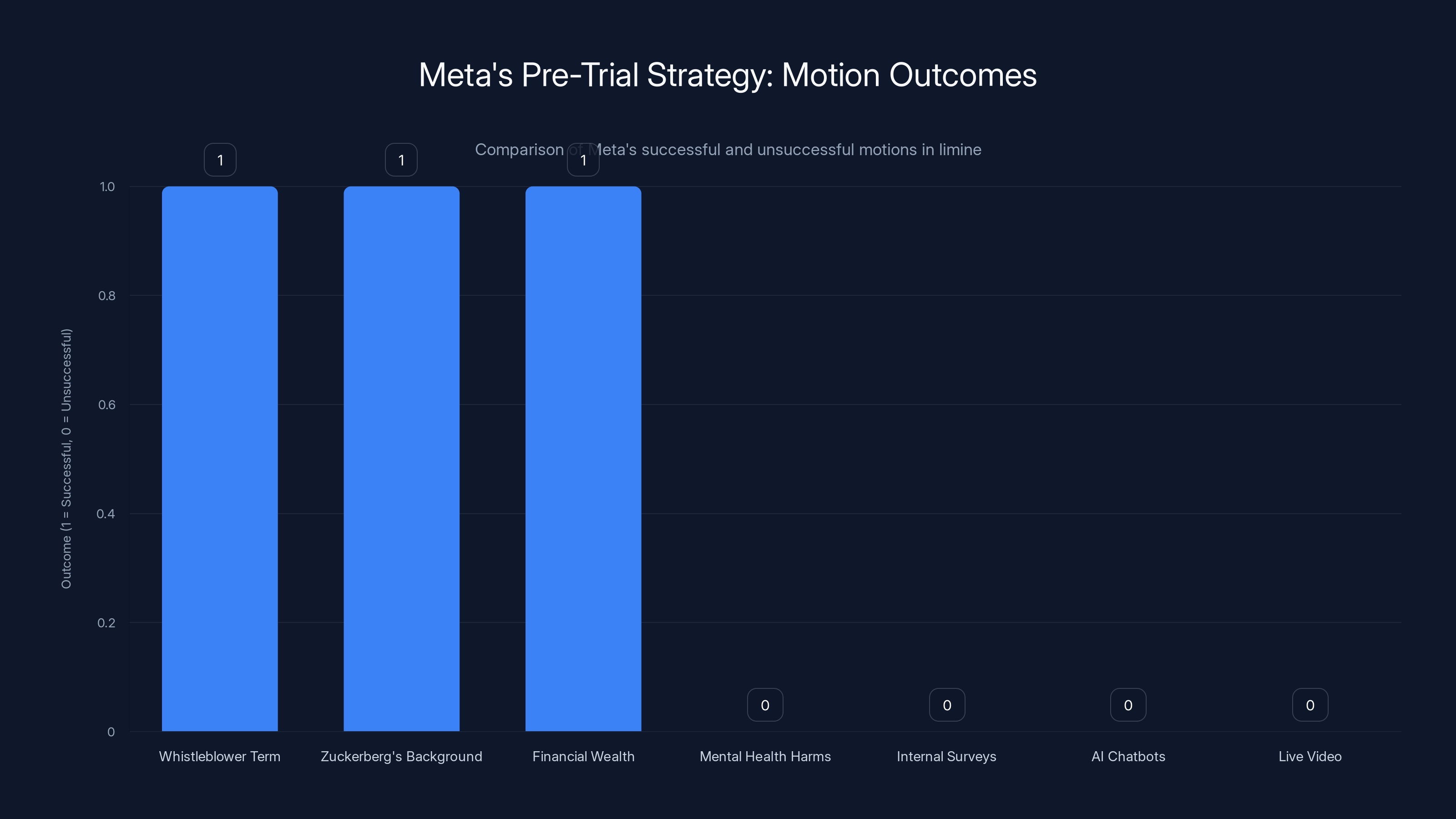

Meta's Pre-Trial Strategy: What Evidence Won't the Jury See?

Meta's motions in limine tell you a lot about which facts the company finds most dangerous.

Meta successfully requested that the judge ban the courtroom from discussing several topics:

- The word "whistleblower": Meta didn't want the jury hearing that term, presumably because it carries connotations of courageous truth-telling. Instead, the plaintiff used phrases like "prior employees with expertise." It's a small change that telegraphs Meta's concern about emotional framing.

- Mark Zuckerberg's Harvard background: Why would that matter? Meta was apparently concerned that it might make Zuckerberg seem either trustworthy or elitist, depending on how it was deployed. Either way, the company wanted it out.

- Meta's financial wealth: This one's interesting. Meta probably didn't want a jury thinking about the company's substantial resources when considering whether it could have afforded better safety systems.

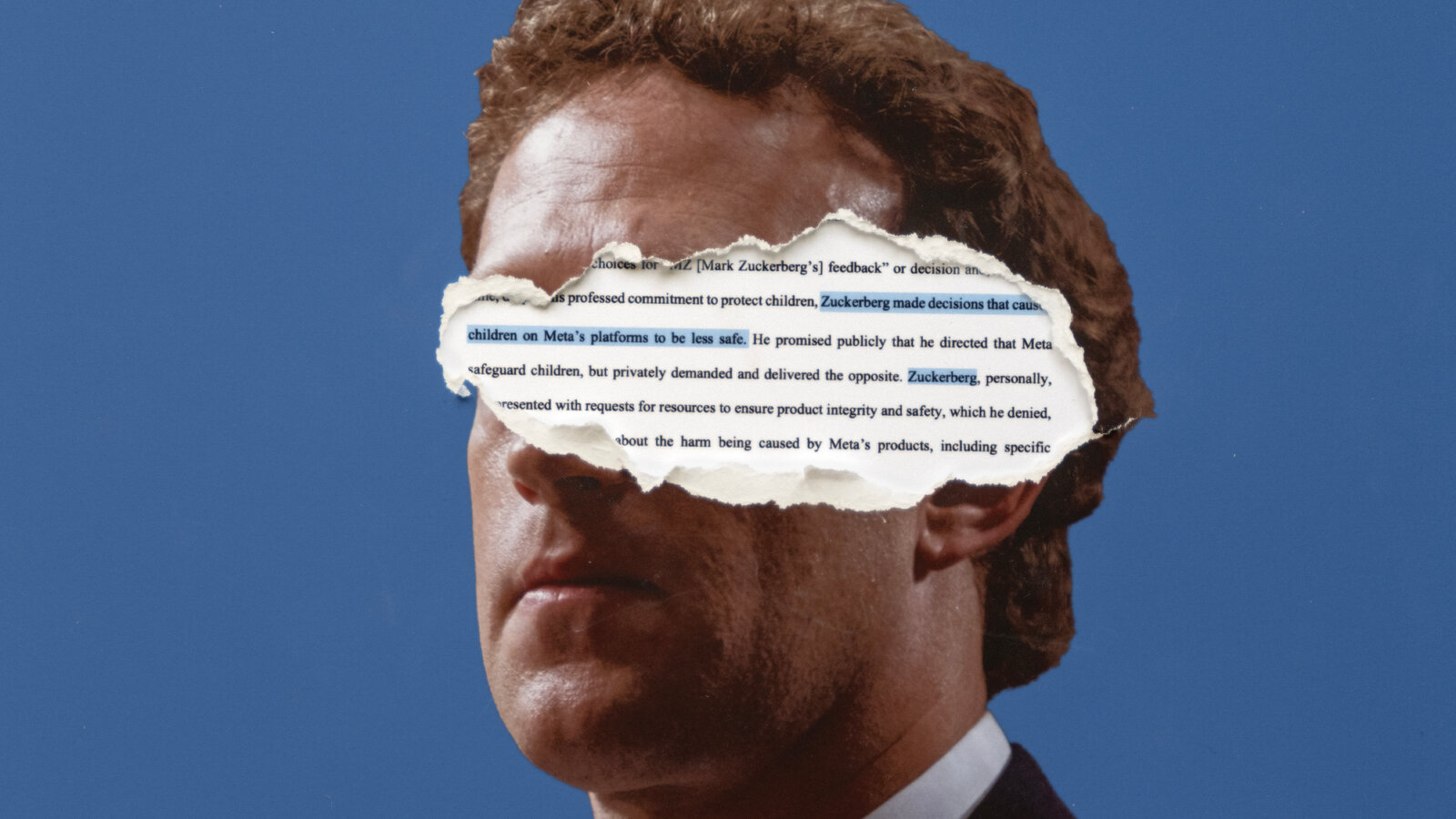

But Meta lost on some critical motions:

- Mental health harms: The court allowed references to the former U. S. Surgeon General's statements about social media's mental health impacts. This matters because it establishes a context where Meta's platforms are understood to pose documented risks.

- Internal surveys showing inappropriate content: The court ruled that surveys indicating high levels of harmful content on Meta's platforms are admissible. This is huge. If Meta's own internal data shows the company knew about widespread exploitation, that's devastating evidence.

- AI chatbots: Meta wanted to keep AI out of the trial, but the court allowed it. This probably relates to Meta's role in content moderation and the company's claims about how it addresses harmful content.

- Live video livestream: Meta asked to block video of the trial being available online. The court said no. Everything is going to be visible and discussable in real-time.

Each of these denials is a win for New Mexico's narrative. The jury gets to see a fuller picture of what Meta knew and when it knew it.

The Section 230 Problem: Tech's Legal Shield and Its Limits

Meta's defense almost certainly hinges on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This is the provision that shields internet platforms from liability for user-generated content. A user posts something illegal or harmful, the platform isn't responsible for that user's speech.

But here's where it gets complicated. Section 230 doesn't shield platforms from liability for their own actions. If Meta is accused of actively promoting or amplifying harmful content through its algorithms, that's different from just hosting user speech. If Meta's design features enable exploitation by making it easy to find minors or child abuse material, that's arguably Meta's conduct, not the user's.

New Mexico's legal theory relies on this distinction. Meta didn't just fail to remove content fast enough. The allegation is that Meta's design actively created conditions for exploitation.

Meta's lawyers will counter that algorithmic recommendations are protected speech. That the company is just presenting content created by users. That Section 230's protections apply even when algorithms amplify that content. This is genuinely unsettled law. Courts have gone both directions on whether algorithmic amplification receives Section 230 protection.

Algorithmic Amplification: The Technical Heart of the Case

Underlying all of this is a question that's surprisingly hard to answer: How much responsibility does Meta bear for what its algorithms promote?

Facebook's algorithm doesn't just show you posts randomly. It prioritizes certain content over other content based on predicted engagement. If content depicting minors or facilitating exploitation gets high engagement, the algorithm can amplify it. Meta's own researchers have documented this. Engagement-driven recommendation systems inevitably surface sensational, provocative, and sometimes harmful content because that's what drives user interaction.

New Mexico's case will likely include expert testimony on how these algorithms work. The testimony will probably establish that:

- Meta knows which content drives engagement

- Meta's algorithm explicitly prioritizes engaging content

- Some exploitative content drives high engagement

- Therefore, Meta's algorithm predictably amplifies exploitative content

- Meta could modify these algorithms to deprioritize such content but chooses not to because it would reduce engagement

Meta will counter with arguments about the technical complexity of content moderation at scale. Facebook and Instagram combined have billions of pieces of content uploaded daily. Nuanced moderation is genuinely difficult. Meta has hired thousands of content moderators. The company uses AI to flag problematic content. Some bad content gets through anyway, but that's the nature of operating at this scale, not evidence of intentional enablement.

Both sides have legitimate points. But a jury doesn't need to believe Meta is malicious. They just need to believe Meta knowingly created conditions where exploitation could happen and didn't do enough to prevent it. That's a lower bar than proving intentional wrongdoing.

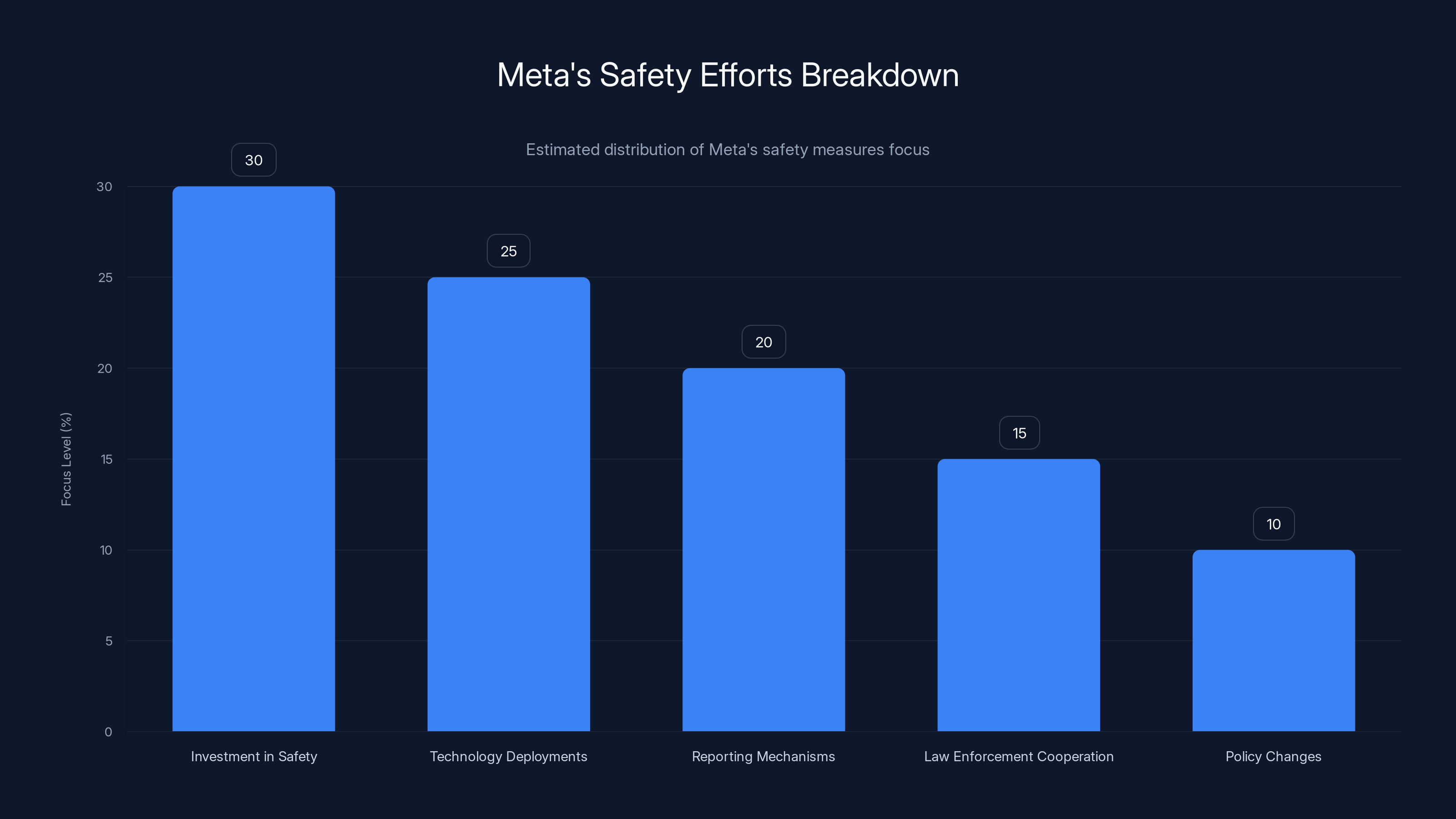

What Meta Claims About Its Safety Efforts

Meta's defense centers on demonstrating proactive safety measures. The company will likely present evidence showing:

- Investment in safety infrastructure: Meta employs thousands of people in safety, trust, and security roles.

- Technology deployments: The company uses machine learning to detect and remove exploitative content before humans even see it.

- Reporting mechanisms: Both Facebook and Instagram have multiple ways for users to report exploitative content.

- Cooperation with law enforcement: Meta shares information about suspected child exploitation with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children and law enforcement agencies.

- Policy changes: Meta has updated its policies regarding interactions between adults and minors, implemented age-verification efforts, and restricted certain features for younger users.

Meta's representative, Aaron Simpson, previously stated: "We're focused on demonstrating our longstanding commitment to supporting young people. We're proud of the progress we've made, and we're always working to do better."

But here's the tension. Even if all of this is true — even if Meta is genuinely trying hard — it doesn't necessarily answer the core question: Did Meta do enough? Or did the company make conscious choices to prioritize engagement over safety?

The case will turn on whether a jury believes Meta's efforts were reasonable given the scale of the problem, or whether those efforts were insufficient given what the company knew about the prevalence of exploitation on its platforms.

Estimated data shows Meta's focus on safety efforts, with significant investment in safety infrastructure and technology deployments. Estimated data.

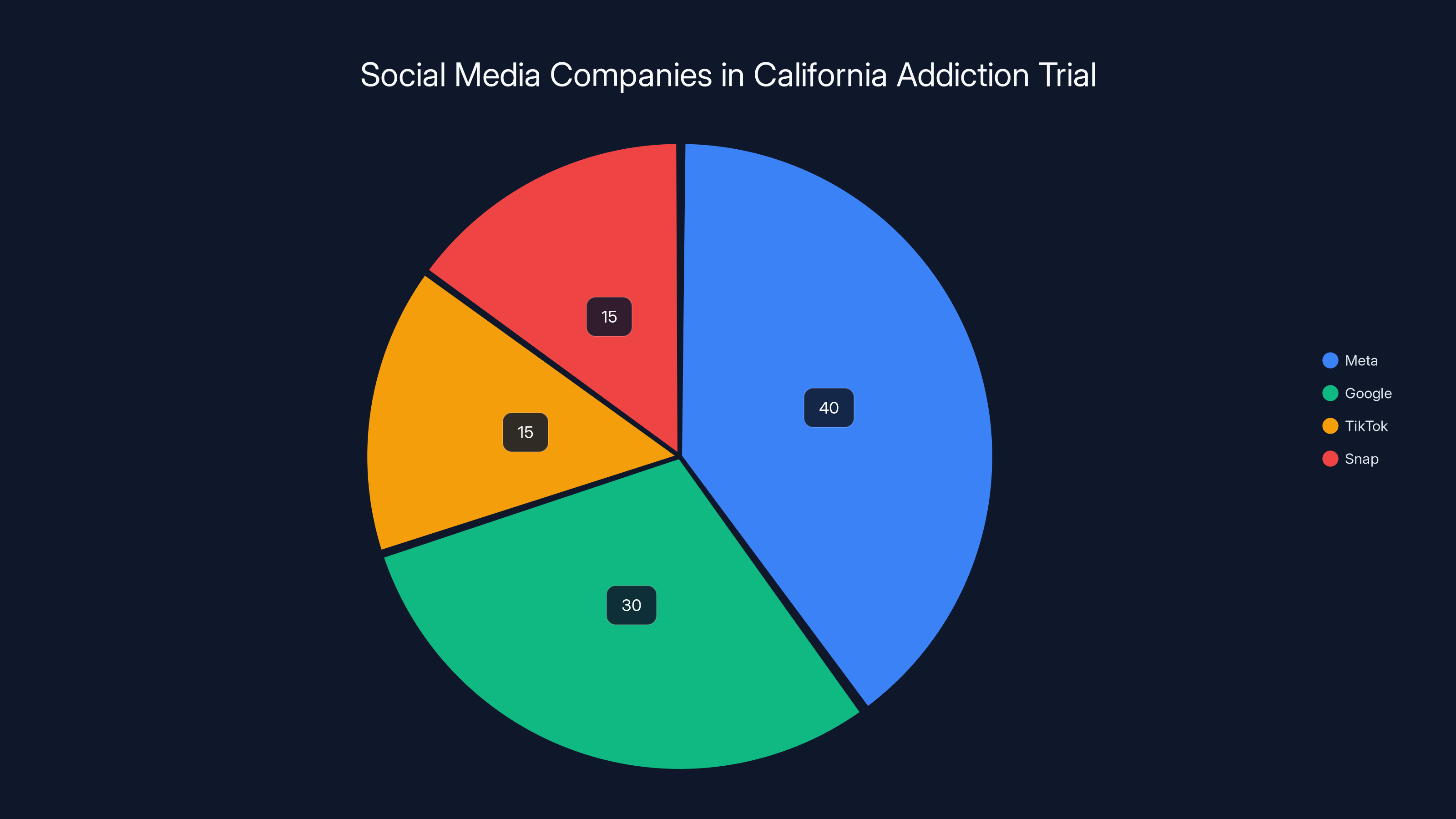

The California Addiction Trial and the Larger Reckoning

Timing matters. The New Mexico trial is happening simultaneously with a landmark case in California — the first major judicial coordinated proceeding (JCCP) involving social media addiction.

That California case, which just started, names Meta, Google, Tik Tok, and Snap as defendants. It consolidates hundreds of individual lawsuits alleging that social media companies deliberately designed addictive products that harmed minors. Snap and Tik Tok settled. Meta and Google are fighting.

That case focuses on addiction, mental health, and product design intended to maximize engagement. This New Mexico case focuses on exploitation, predation, and failures to protect children. They're different lawsuits, but they share a common accusation: that Meta and other platforms made conscious choices favoring engagement and growth over user safety and wellbeing.

Sacha Haworth, executive director of the Tech Oversight Project watchdog organization, framed it this way: These trials represent "the split screen of Mark Zuckerberg's nightmares: a landmark trial in Los Angeles over addicting children to Facebook and Instagram, and a trial in New Mexico exposing how Meta enabled predators to use social media to exploit and abuse kids."

Haworth called them "the trials of a generation," comparing the moment to when courts held Big Tobacco and Big Pharma accountable. The analogy is provocative but not without merit. These are the first major trials where tech platform design choices are being scrutinized by juries in a context of documented harm to children.

What Evidence Will Actually Matter to a Jury?

Juries are unpredictable, but certain evidence categories will almost certainly be persuasive:

Internal Communications: If Meta employees wrote emails or messages expressing concern about child exploitation on the platform, those documents are gold for New Mexico. They establish knowledge. They suggest Meta understood the problem and didn't act decisively. Internal documents have destroyed corporate defendants before.

Comparative Data: Evidence showing that Meta's safety performance lags behind competitors, or that other platforms have lower rates of exploitation content, suggests that better practices exist and Meta chose not to implement them.

Undercover Operations: The investigator posing as a mother and successfully connecting with presumed child traffickers is devastating evidence. It demonstrates that the platform can facilitate exploitation in real time, despite Meta's stated safety systems.

Expert Testimony: Technical experts explaining how algorithms work, how engagement metrics influence content amplification, and how other companies have solved similar problems will be crucial. If experts testify that Meta's system design was foreseeable to enable exploitation, that's powerful.

Quantitative Data: Statistics about how much exploitative content Meta detects and removes, how quickly the company responds to reports, and how many reports are duplicates (suggesting the same content isn't being caught) all paint a picture of scale and systemic problems.

Victim Impact: If the trial includes testimony from people harmed through exploitation on Meta's platforms, that will be deeply affecting. Juries respond to human stories.

Meta will counter with its own evidence: the scale of content moderation, the sophistication of detection systems, the millions of pieces of content removed daily. But these arguments are harder to make emotionally compelling.

The Financial Stakes for Meta

Meta's financial position is strong. The company has tens of billions in cash and generates substantial quarterly profits. A financial penalty, even a large one, won't threaten the company's survival.

But there are other stakes. If Meta loses, the loss creates a precedent. Other states will likely file similar cases. The California addiction trial could go against Meta as well. Multiple losses create momentum for federal regulation and legislation.

Furthermore, a significant loss changes the narrative. Meta's been positioned as the company that solves regulatory challenges through litigation. A major jury verdict against the company suggests that approach has limits.

Meta might face requirements to redesign certain features, implement specific safety measures, or submit to ongoing monitoring. These structural changes could reduce engagement metrics if they make the platform less addictive or less effective at connecting users.

There's also the question of punitive damages. If a jury finds that Meta's conduct was egregious enough to warrant punishment rather than just compensation, damages could exceed what might otherwise be expected.

How Content Moderation Failures Happened at Scale

Understanding how exploitation could be widespread enough to sustain New Mexico's allegations requires understanding content moderation at Meta's scale.

Facebook and Instagram combined have roughly 3.2 billion monthly active users. Every day, users upload roughly 350 million photos and over 500 hours of video. No human team can review all of this content. Even with machine learning assistance, some harmful content reaches users.

Content moderation is also genuinely hard. Context matters. A photo that's innocuous to one person might look suspicious to another. Young people sometimes post provocative content for legitimate reasons. Predators deliberately disguise exploitative content using codes, encrypted communication, and private messages.

But Meta had specific choices about how to allocate resources. The company could have invested more heavily in safety teams. It could have implemented more restrictive defaults for younger users. It could have modified algorithms to deprioritize content from users flagged for suspicious behavior. It could have restricted direct messaging between adults and minors. It could have required more robust age verification.

The question isn't whether Meta's moderation is perfect. It's whether Meta chose, at various decision points, to prioritize engagement over additional safety measures.

Estimated data showing the distribution of major social media companies involved in the California addiction trial. Meta and Google are the primary defendants, while TikTok and Snap have settled.

Section 230 Reform and the Broader Debate

Beyond this specific trial, the case reflects broader debates about whether Section 230 needs reform.

Section 230 was passed in 1996, before social media existed. The law was designed to enable platforms to moderate content without becoming publishers themselves. It's been crucial to the internet as we know it. Without it, every platform would face massive liability for user-generated content.

But Congress has been increasingly critical of Section 230. Bipartisan coalitions have called for reforms that would:

- Hold platforms responsible for algorithmic amplification

- Create exceptions for child exploitation material

- Require platforms to prove they're making good-faith moderation efforts

- Establish standards for what "reasonable" content moderation looks like

If Meta loses the New Mexico case, it strengthens arguments for Section 230 reform. If Meta wins, it suggests that existing law provides sufficient protection and that states can't unilaterally hold platforms responsible for user-generated content, no matter how it's amplified.

Either way, the trial is informing a much larger policy conversation.

Comparable Cases and Historical Precedent

While this is the first standalone state child safety case against Meta to reach trial, there are related precedents that offer some guidance.

The tobacco and opioid litigation waves created frameworks for holding corporations responsible for products and practices that caused widespread harm. Those settlements involved proving that companies knew about harms, concealed information about those harms, and continued engaging in profitable practices despite known risks.

Similarly, early internet cases like CDA 230 litigation and Doe v. AOL established that platforms can sometimes be held responsible for failing to remove known harmful content, particularly when that content violates criminal law.

Meta's own settlements with the FTC on privacy violations show that tech companies can be held accountable even for practices that seem technically legal. Those settlements required Meta to change business practices and submit to monitoring.

But child exploitation cases have always been treated more seriously by juries and judges than privacy or monopoly cases. The moral clarity is stronger. The victim sympathy is greater. It's harder to make technical arguments about business models when children's safety is at stake.

The Expert Witnesses and What They'll Testify

Both sides will bring expert witnesses. These experts can make or break a case.

New Mexico will likely call experts on:

- Algorithmic systems: Technical experts who can explain how Facebook's recommendation algorithm works and how it predictably amplifies engaging content

- Child development: Experts who can testify about minors' vulnerability to exploitation and their limited ability to protect themselves online

- Predator behavior: Experts who can explain grooming tactics and how social media platforms facilitate predatory behavior

- Comparative company practices: Industry experts who can testify about how other companies have implemented stronger child protection measures

- Content moderation standards: Experts who can define what reasonable, industry-standard content moderation looks like

Meta will counter with experts on:

- Technical limitations: Experts who can explain why perfect content moderation is technically infeasible at scale

- AI capabilities and limitations: Experts who can testify about what machine learning can and cannot reliably detect

- Industry standards: Experts who can argue that Meta's safety practices meet or exceed industry norms

- Statistical realities: Experts who can put exploitation statistics in context, arguing that the rate is actually lower than one might assume given the platform's size

Expert testimony often becomes the battle within the larger trial. Juries have to assess conflicting expert opinions, which creates uncertainty that can favor defendants.

Public Perception and the Reputational Dimension

Regardless of the trial's legal outcome, Meta's brand reputation is at stake.

Metaverse investments haven't captured public imagination. Meta's AI efforts, while technically impressive, haven't achieved the visibility of Open AI's Chat GPT or Anthropic's Claude. The company's core business — selling advertising on Facebook and Instagram — remains profitable but is no longer seen as innovative or forward-looking.

A trial with daily coverage of child exploitation allegations, even if Meta ultimately prevails, contributes to a narrative that the company prioritizes profits over safety. Parents already express concern about whether their teenagers should use Instagram. A trial highlighting exploitation vulnerabilities intensifies those concerns.

Advertisers might also face pressure to reconsider their spending on Meta platforms if child safety becomes a persistent public concern.

Meta's pre-trial strategy saw mixed results, with successful motions to exclude topics like 'whistleblower' and Zuckerberg's background, but failures on key issues like mental health impacts and internal surveys.

What a Meta Loss Would Actually Mean

If the jury returns a verdict in favor of New Mexico, what happens next?

First, there would almost certainly be an appeal. Meta would argue that the verdict was inappropriate, that the law doesn't support the verdict, or that new evidence should be considered. Appeals in cases like this can take years.

Second, damages could be substantial. If the jury awards significant compensatory damages, they might also award punitive damages if they find Meta's conduct egregious. Punitive damages are meant to punish and deter, not just compensate victims.

Third, the court might impose structural reforms. Rather than just paying money, Meta might be required to implement specific child safety measures, submit to auditing, or restrict certain features.

Fourth, other states would immediately file similar cases. A New Mexico win creates a roadmap. Other states' attorneys general would argue that if Meta violated New Mexico's unfair practices act, it violated theirs too.

Fifth, the verdict would strengthen arguments for federal legislation. Congress has been looking for reasons to act on tech regulation. A jury verdict providing evidence that major platforms harm children gives lawmakers political cover for regulation.

What a Meta Victory Would Mean

If the jury returns a verdict in Meta's favor, that outcome also has significant implications.

It would suggest that Section 230 provides meaningful protection even for algorithmic amplification of user content. That would dampen enthusiasm for Section 230 reform focused on platform design rather than specific illegal content.

It would validate Meta's legal strategy of defending through litigation rather than settling. That might embolden other tech companies facing similar suits.

It would suggest that proving Meta knowingly created exploitative conditions is a higher bar than some reformers believed. That could make future plaintiff-side cases more difficult.

But even a Meta victory wouldn't end the conversation about child safety. Public concern would remain. Other litigation would continue. Federal legislation might still pass.

The significance of a Meta victory would be primarily legal — establishing what claims can and can't be brought under state consumer protection law — rather than settling the broader policy questions about whether social media design adequately prioritizes child safety.

The Intersection of Design, Profit, and Safety

Underlying all of this is a fundamental tension in how social media platforms operate.

Facebook and Instagram are free to users. They generate revenue by selling advertising. Advertisers pay for access to user attention. Therefore, maximizing user engagement — the amount of time and attention users devote to the platform — directly translates to revenue.

This creates algorithmic incentives that aren't always aligned with user safety. Exploitative content, while representing a tiny fraction of overall content, can drive engagement. Restricting engagement-driving content reduces revenue.

Meta could make different choices. The company could cap engagement to reduce addictiveness and incidentally reduce the visibility of exploitative content. It could implement more restrictive defaults for younger users. It could limit algorithmic amplification of content from accounts with histories of suspicious behavior.

But these changes would reduce engagement. They might reduce advertising revenue.

The New Mexico trial is ultimately asking: Can we force companies to make those choices? Can we hold them legally responsible when they don't? Or does Section 230 protect companies that make business decisions prioritizing profit over safety?

Those are the actual questions being litigated, hidden beneath the specific allegations about child exploitation.

The Seven-Week Timeline and What to Watch

The trial is expected to run seven weeks. That's long for a civil case but reasonable given the complexity.

Early weeks will likely focus on opening arguments and establishing the facts of the case — what Meta knew, when it knew it, what efforts it made to address exploitation. This is when the most damaging evidence against Meta will likely emerge.

Middle weeks will involve expert testimony from both sides. This is where the technical arguments about algorithms, content moderation, and industry standards get complicated and contentious.

Later weeks will focus on damages arguments if the jury has found in favor of New Mexico, or on Meta's defense and arguments that even if the facts are as alleged, they don't constitute a legal violation.

Watching for key moments:

- Deposition excerpts or testimony from Meta executives: Will any Meta leaders be called to testify? Their testimony under oath could be more revealing than prepared statements.

- Internal document releases: What do Meta's own researchers, product managers, and lawyers say about child safety in private communications?

- Expert testimony on algorithmic design: How clearly can experts explain the connection between Meta's engagement-driven algorithm and the visibility of exploitative content?

- Comparative industry practices: Will experts testify that Meta lags competitors in child protection?

- Statistical evidence: What do Meta's own safety metrics show about the prevalence and detection of exploitative content?

The trial will also reveal new information about how Meta actually works internally. That information will likely become public and contribute to broader debates about whether social media platforms should be regulated differently.

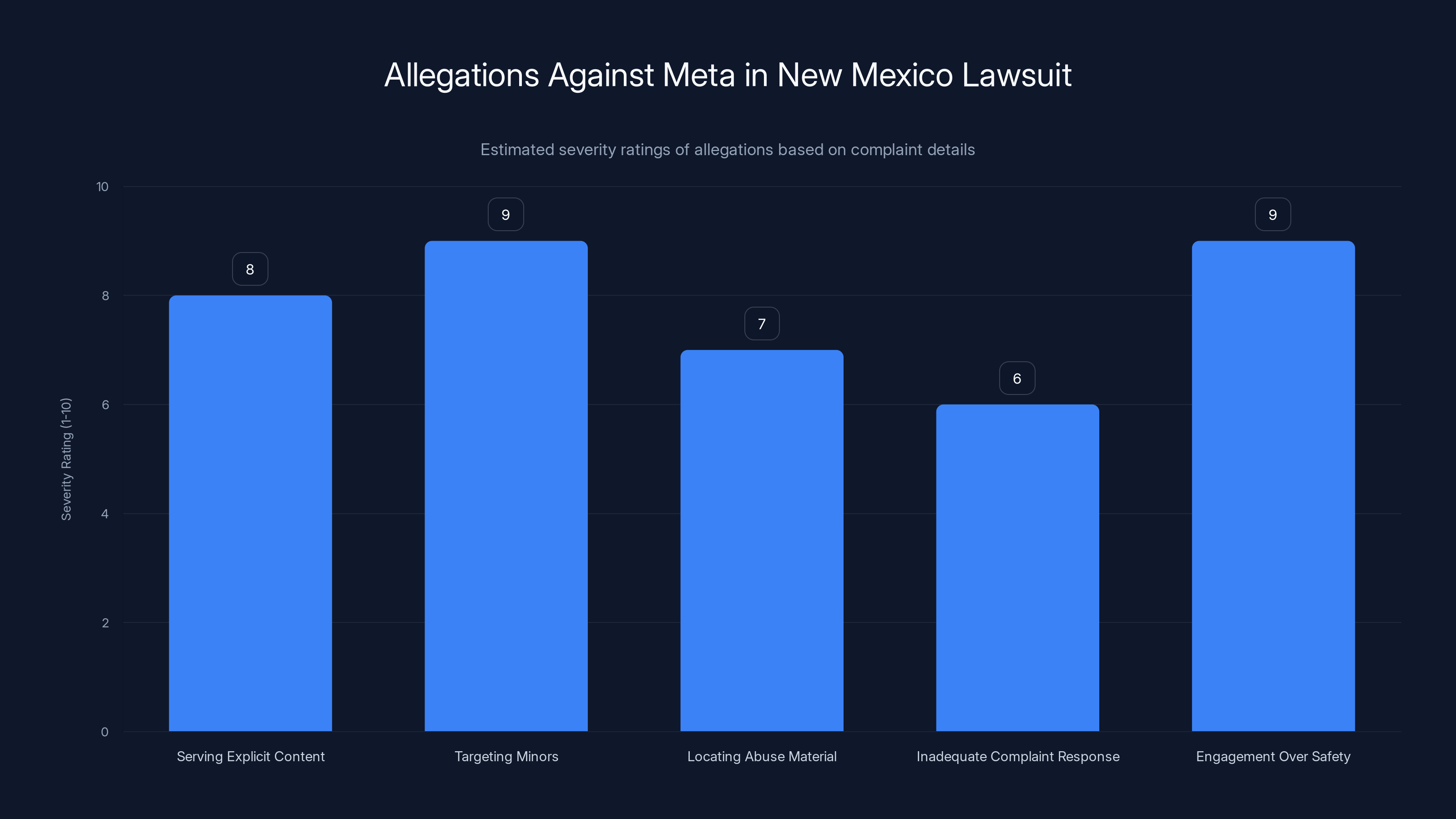

Estimated data: The chart visualizes the severity of allegations against Meta, with 'Targeting Minors' and 'Engagement Over Safety' rated highest.

Broader Implications for the Tech Industry

This trial matters beyond Meta. It affects how the entire tech industry thinks about child safety and legal liability.

Google, Amazon, Tik Tok, Snap, and other platforms all operate under similar business models with similar algorithmic structures. If Meta loses in New Mexico, every platform faces increased legal risk. Every platform will face pressure to implement stronger child safety measures.

If Meta wins, it's a signal that state-level litigation against tech companies is limited in scope. Federal legislative action might become more urgent.

Either way, we're witnessing a shift in how child safety is framed. It's no longer just a corporate responsibility or ethics issue. It's becoming a legal liability issue. That changes incentives.

Forward-looking platforms might already be asking: What do we change about our algorithms and features to reduce legal exposure? How do we implement better age verification? How do we restrict data collection from minors? How do we limit algorithmic amplification to younger users?

Those questions suggest that even without a verdict in Meta's favor, the trial is already shifting how the industry thinks about child protection.

The Regulatory and Legislative Context

The New Mexico trial doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's part of a broader regulatory and legislative environment becoming increasingly hostile to tech companies.

The European Union has already passed the Digital Services Act, which imposes requirements on platform governance and content moderation. Platforms operating in Europe must demonstrate compliance with these standards.

The U. S. Congress has proposed multiple bills targeting social media companies' practices. Some focus on Section 230 reform. Others target algorithmic recommendation systems. Still others specifically address child safety online.

Many of these proposals have bipartisan support, which is unusual in the current political environment. Child safety is one of the few tech policy issues that can unite Republicans and Democrats.

If federal legislation passes, it might preempt some of what New Mexico is trying to accomplish through litigation. Or it might reinforce the legal obligations that the trial establishes.

Either way, the combination of litigation and legislative pressure is creating a moment where tech companies' child safety practices are under unprecedented scrutiny.

Meta's Pivot to AI and What It Means for This Case

There's an interesting subtext to this trial. Meta is investing heavily in artificial intelligence and less interested in social media dominance than it has been in previous years.

The metaverse didn't work out. AI is now Meta's primary bet for future growth.

But AI doesn't generate revenue the way social media does. There's no equivalent to advertising on AI assistants. Meta's investing in AI partly as a defensive move (to compete with Chat GPT) and partly as a speculative bet on where computing goes in the next decade.

This creates an interesting dynamic. Meta might actually prefer to reduce engagement on Facebook and Instagram to deal with child safety liability. Lower engagement on social media frees up resources for AI investment. If child safety regulations reduce social media engagement, Meta could reposition that as accepting the new market reality rather than having its hand forced.

In other words, Meta might not fight this case with the same intensity that it would have five years ago, when social media was the company's primary growth engine.

That doesn't mean Meta will lose intentionally. But it might mean the company is more willing to settle or accept adverse verdicts if the outcomes don't directly threaten its core business.

The International Dimension and Global Standards

Child safety online isn't just a U. S. problem. The EU has already imposed stricter requirements on platforms regarding child protection. The UK is developing online safety legislation. Australia, Canada, and other countries are moving toward stronger regulations.

Meta already operates under different rules in different jurisdictions. The company likely assumes that a loss in New Mexico would eventually lead to federal U. S. legislation and that federal legislation would be less strict than international standards like the EU's approach.

From Meta's perspective, a New Mexico verdict might be preferable to the regulatory path Europe is taking. Federal legislation in the U. S., while potentially costly, might offer more clarity and uniformity than a patchwork of state and international rules.

This international context might affect how aggressively Meta fights the case. The company needs to maintain relationships with regulators globally. Appearing as a company that fights child safety allegations might create diplomatic problems in other markets.

The Emotional and Moral Dimensions

Beyond the legal and business arguments, there's a fundamental emotional dimension to this case that shouldn't be underestimated.

Parents are afraid for their children. The internet is a real place where real bad things happen. Child exploitation is real. When parents learn that social media platforms they assumed had basic safety protections might actually be enabling exploitation, they feel betrayed and angry.

Juries are made up of parents. They have kids. They use social media. They understand, at a visceral level, what child exploitation means.

This emotional dimension favors New Mexico. Meta can present technical arguments, but those arguments feel abstract next to the reality of a child being harmed.

Meta's best strategy is probably to acknowledge the seriousness of the problem, emphasize what the company is doing about it, and argue that the company is trying harder than is sometimes realized. But that argument is difficult when the core allegation is that Meta chose engagement over safety.

What Success Looks Like for Each Side

For New Mexico, success doesn't necessarily mean getting the largest possible judgment. Success means establishing that:

- Social media platforms can be held responsible for failing to protect minors

- Algorithmic amplification counts as the platform's conduct, not just user speech

- Companies must do more than Meta currently does to protect children

- State consumer protection laws apply to social media platforms

Even if the ultimate judgment is moderate, those legal findings would be victories.

For Meta, success means establishing that:

- Section 230 provides protection for algorithmic amplification

- Platforms aren't liable for user conduct even when algorithms amplify that conduct

- Current safety practices, while imperfect, represent reasonable efforts at scale

- State attorneys general can't use consumer protection laws to impose platform-specific design requirements

Meta could achieve those victories even if it's found to have been negligent in some respects. The goal is establishing favorable legal precedent.

FAQ

What specifically is Meta being accused of in the New Mexico case?

New Mexico alleges that Meta violated state consumer protection laws by implementing design features and algorithms that created dangerous conditions for minors. Specifically, the state claims Meta proactively served explicit content to underage users, enabled adults to identify and target children, made it easy to locate child sexual abuse material, and failed to respond adequately to reports of exploitation. The core allegation is that these weren't failures to prevent harm but rather choices in how to design the platform that prioritized engagement over child safety.

How is the New Mexico trial different from other Meta litigation?

This is the first standalone, state-led child safety case against Meta to reach trial in the U. S. Previous cases have focused on antitrust issues, privacy concerns, or monopolistic behavior. The New Mexico case is unique because it focuses on direct harm to consumers (child exploitation) rather than competition or data practices. Additionally, Meta hasn't settled this case as it has with many others, making it an actual jury trial rather than a settlement. The legal theory uses decades-old consumer protection law rather than novel legal frameworks.

What does Section 230 have to do with this case?

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act shields internet platforms from liability for user-generated content. However, the law doesn't protect platforms from liability for their own conduct. New Mexico's case argues that Meta's algorithmic amplification constitutes Meta's conduct, not just hosting of user speech. If the court agrees that algorithms are conduct rather than speech, Section 230's protections might not apply. This distinction is crucial because it determines whether Meta can be held responsible for harm facilitated by its algorithms.

Why might this trial set a precedent for other states and companies?

If New Mexico prevails, it establishes that state consumer protection laws can be applied to social media platforms regarding child safety. It would show that platforms can be held liable not just for failing to remove content, but for designing systems that enable exploitation. This would immediately encourage other states to file similar cases against Meta and potentially other tech companies. Even if Meta wins, the trial will clarify what legal theories can and cannot be pursued against platforms, informing future litigation strategy.

How long is the trial expected to last and what evidence will be presented?

The trial is expected to run seven weeks. Both sides will present evidence including Meta's internal communications and documents, expert testimony about algorithmic design and content moderation, statistical evidence about exploitative content on the platform, undercover operations showing how easily the platform can be used to exploit minors, and testimony from industry experts about comparative safety practices. Meta will present evidence of its safety investments and moderation efforts, while New Mexico will focus on showing Meta's knowledge of problems and insufficient response.

What is the significance of the jury composition in this case?

The jury consists of ten women and eight men (twelve jurors plus six alternates). Research indicates that juries with women tend to take child safety allegations more seriously than juries without women, and female jurors statistically are more likely to rule in favor of plaintiffs in cases involving exploitation and harm to children. This jury composition potentially favors New Mexico's case, though jury behavior is ultimately unpredictable.

How does Meta's business model relate to the allegations in this case?

Facebook and Instagram are free to users and generate revenue through advertising. Advertisers pay for access to user attention, creating incentives for Meta to maximize user engagement. Content that exploits minors, while representing a small fraction of overall content, can drive high engagement. Algorithms designed to maximize engagement predictably amplify such content. The case essentially questions whether Meta made conscious choices to prioritize engagement and advertising revenue over protecting minors from exploitation, despite knowing the consequences.

What could happen if Meta loses the trial?

If the jury returns a verdict in favor of New Mexico, Meta would likely appeal, which could take years. The company might face substantial compensatory damages and potentially punitive damages if the jury finds the conduct egregious. The court might impose structural reforms requiring Meta to implement specific child safety measures or submit to auditing. Other states would almost certainly file similar cases using New Mexico's precedent. The verdict would strengthen arguments for federal legislation on tech regulation and Section 230 reform.

How does this trial relate to the California social media addiction case?

Both trials involve Meta and represent unprecedented judicial scrutiny of the company's practices. The California case focuses on whether Meta deliberately designed addictive products that harmed minors' mental health. The New Mexico case focuses on whether Meta's design enabled child sexual exploitation. While different, both cases argue that Meta made conscious design choices prioritizing engagement and profit over user wellbeing. Having both trials proceed simultaneously intensifies pressure on Meta and public attention to the company's role in child harm.

Why haven't Meta executives like Mark Zuckerberg testified in this case?

While executive depositions exist and may be presented as testimony, Meta executives are unlikely to testify live in the New Mexico trial. This is partly because the company can present its case through other witnesses and partly because it's generally riskier to put top executives on the stand in hostile litigation. However, executive depositions will still be presented, potentially revealing the company's internal decision-making around child safety policies and responses to known problems. The California trial might see more executive testimony since Meta is not settling that case either.

Automating Your Response to Tech Litigation Concerns

If you're responsible for managing brand reputation or stakeholder communications during legal proceedings like this, consider how platforms like Runable can help you create professional reports, presentations, and documents that communicate complex issues clearly. When litigation involves technical arguments about algorithmic design, having tools to visualize those arguments and explain them to non-technical stakeholders becomes crucial.

Use Case: Create executive briefings and visual explanations of complex algorithmic systems and regulatory requirements without requiring extensive technical documentation.

Try Runable For FreeLooking Forward: What Happens After the Verdict

Regardless of how the jury rules, this trial represents a turning point in how courts and regulators think about social media platform responsibility.

For years, tech companies operated under the assumption that Section 230 provided broad protection and that regulation would be slow and incremental. This trial, combined with the California addiction case and international regulatory developments, suggests that assumption is no longer valid.

Platforms are being forced to defend their design choices in court. That's a new reality. Companies that had focused on scale and engagement are now having to answer questions about whether those priorities were appropriate given what they knew about harms to children.

The verdict in Santa Fe won't settle all these questions. But it will provide clarity on at least some of them. And that clarity will shape how the tech industry operates for years to come.

Parents should watch this trial not because the outcome will immediately change what their kids experience on social media, but because the questions being asked about Meta will eventually apply to every platform their kids use. If this trial establishes that platforms can be held responsible for enabling exploitation through algorithmic design, that changes the incentive structure across the entire industry.

Investors should watch because a Meta loss reshapes the regulatory risk profile for any platform relying on engagement-driven algorithms. Advertisers should watch because child safety becomes a brand risk that affects where companies place marketing dollars. Policymakers should watch because the trial will clarify which legal theories work against platforms and which don't, informing future legislation.

This is genuinely one of those moments where a single trial has implications far beyond the specific parties involved.

Conclusion

Meta's child safety trial in New Mexico represents the most serious judicial challenge the company has faced since its inception. It's not about market dominance or data collection. It's about whether social media platforms have legal responsibility when their design choices enable exploitation of minors.

The case is complex, involving technical arguments about algorithms, legal questions about Section 230, and fundamental questions about how companies should balance profit and safety. But underneath all that complexity is a straightforward question: Did Meta do enough to protect children from exploitation on its platforms, or did the company make conscious choices prioritizing engagement over safety despite knowing the consequences?

The trial's outcome will affect Meta directly through potential damages, required changes to platform design, or settlements with regulators. But it will affect the entire tech industry indirectly by establishing legal precedent about what companies can be held responsible for.

If Meta loses, expect rapid regulatory action, other state lawsuits, and potential federal legislation. If Meta wins, expect continued pressure from international regulators, continued litigation focused on different legal theories, and growing public skepticism about whether the company takes child safety seriously.

Either way, the era when tech companies could design for engagement without serious legal consequences appears to be ending. This trial is the beginning of the reckoning.

For organizations navigating complex regulatory landscapes and needing to communicate technical concepts clearly, tools like Runable become increasingly valuable. The ability to create clear, professional presentations and reports about complex issues can mean the difference between stakeholders understanding your position and remaining confused. When legal stakes are high, clarity matters.

Use Case: Generate comprehensive reports and presentations about regulatory compliance, litigation strategy, and stakeholder communication in minutes instead of hours.

Try Runable For FreeThe Meta trial won't end the debate about social media's role in child safety. But it will provide the first major jury verdict on whether platforms bear legal responsibility for that safety. That verdict will reverberate through the tech industry and inform policy debates for years to come. Watch closely.

Key Takeaways

- Meta faces its first standalone state-led child safety trial in New Mexico, with allegations it enabled child exploitation through design choices and algorithmic amplification rather than just failing to prevent it

- The trial's legal outcome could reshape Section 230 interpretation and establish whether platforms bear responsibility for how algorithms amplify user-generated content

- Seven-week trial includes evidence on Meta's internal knowledge of exploitation, algorithmic design choices, and comparative industry safety practices that could inform future regulation

- Meta's simultaneous California addiction trial creates parallel pressure on the company regarding how engagement-driven design affects minors' wellbeing

- A verdict either way establishes legal precedent that will influence state-level litigation, federal legislation, and platform design practices across the entire tech industry

Related Articles

- Section 230 at 30: The Law Reshaping Internet Freedom [2025]

- How Roblox's Age Verification System Works [2025]

- Tech Politics in Washington DC: Crypto, AI, and Regulatory Chaos [2025]

- Discord Age Verification Global Rollout: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Uber's $8.5M Settlement: What the Legal Victory Means for Rideshare Safety [2024]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

![Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-child-safety-trial-what-the-new-mexico-case-means-202/image-1-1770682060477.jpg)