Introduction: The Metaverse Dream Hits Reality

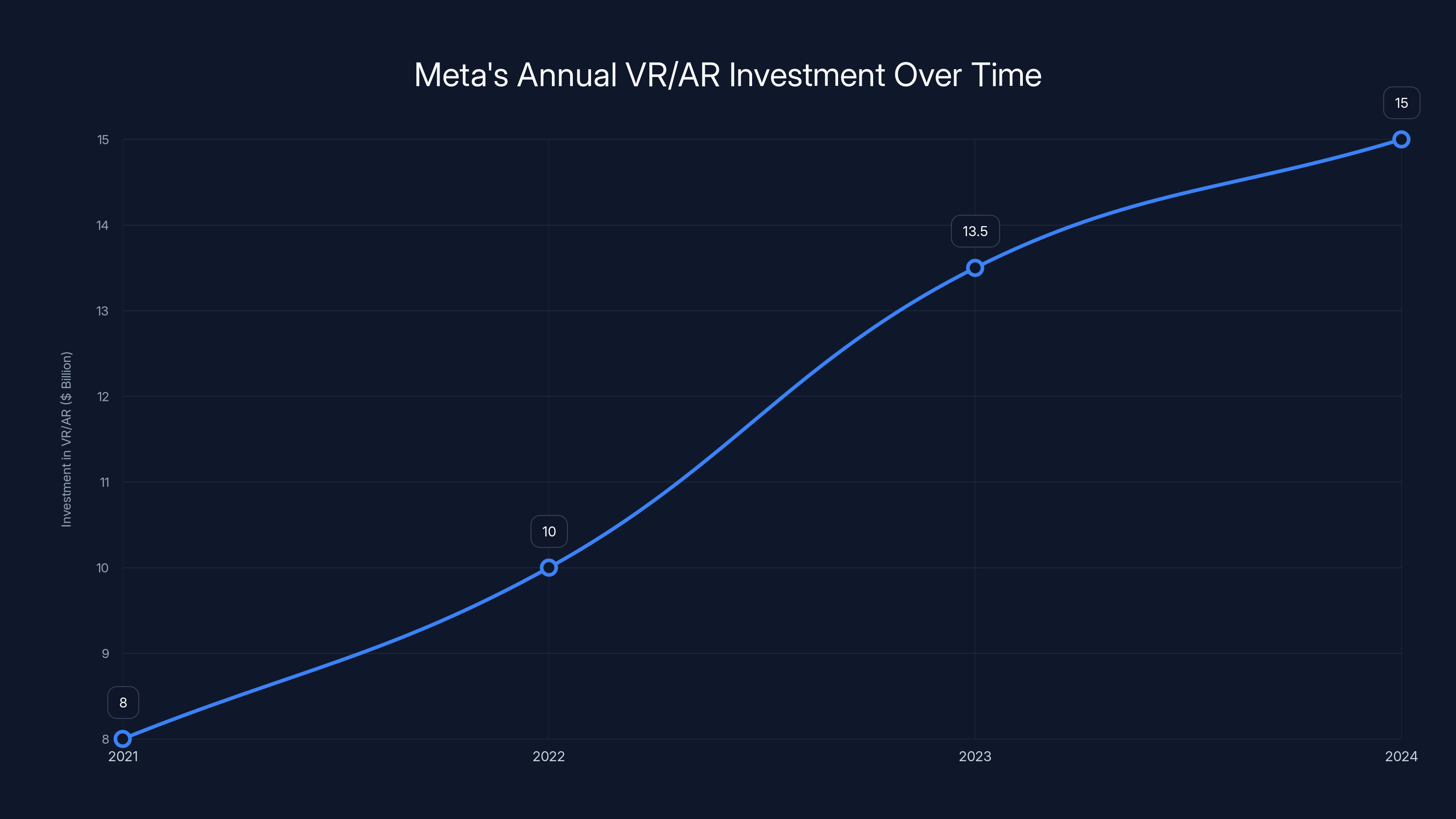

Remember when the metaverse was supposed to be the future? When Meta was betting billions on virtual worlds, spending upwards of $13.5 billion annually on Reality Labs? When Mark Zuckerberg talked about the metaverse like it was inevitable, the next frontier of human connection?

That story just changed dramatically. And honestly, it's a lot more interesting than the original hype.

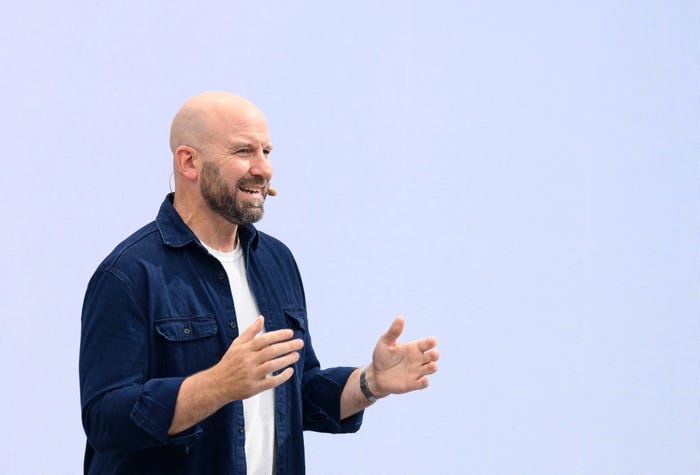

In late 2024 and early 2025, Meta's Chief Technology Officer Andrew Bosworth made headlines with a refreshingly honest take: "We're going to let VR be what it is." Translation? Stop forcing everyone into virtual worlds. Stop building the "metaverse" as if it's destiny. Instead, focus on what VR actually does well.

This isn't just corporate spin. It represents a fundamental shift in how the tech industry's largest bets are being reassessed. The company laid off thousands of employees from its VR division, cut budgets, and essentially admitted the metaverse vision—at least as originally conceived—wasn't working.

But here's the plot twist: this retreat isn't a failure. It's actually a maturation. It's Meta finally accepting what the market has been telling it for years: VR is powerful, but it's not everything. And the sooner they build for actual use cases instead of sci-fi fantasies, the sooner VR becomes genuinely useful.

Let's dig into what's really happening with Meta's VR division, why the layoffs happened, what Bosworth actually means by "letting VR be what it is," and where the company is headed next.

TL; DR

- The Layoffs: Meta cut thousands of employees from its Reality Labs division as VR adoption stalled and spending exceeded $13.5B annually with minimal ROI

- The Problem: The original metaverse vision was too ambitious, expensive, and solved problems nobody had while ignoring what VR actually does well

- Bosworth's Statement: "Let VR be what it is" means focusing on practical applications instead of forcing a sci-fi worldview that users didn't want

- The New Direction: Meta is shifting toward AI agents, productivity tools, and real-world applications that leverage VR's genuine strengths

- The Industry Impact: This signals a broader reset across tech companies that overspent on metaverse visions without user demand

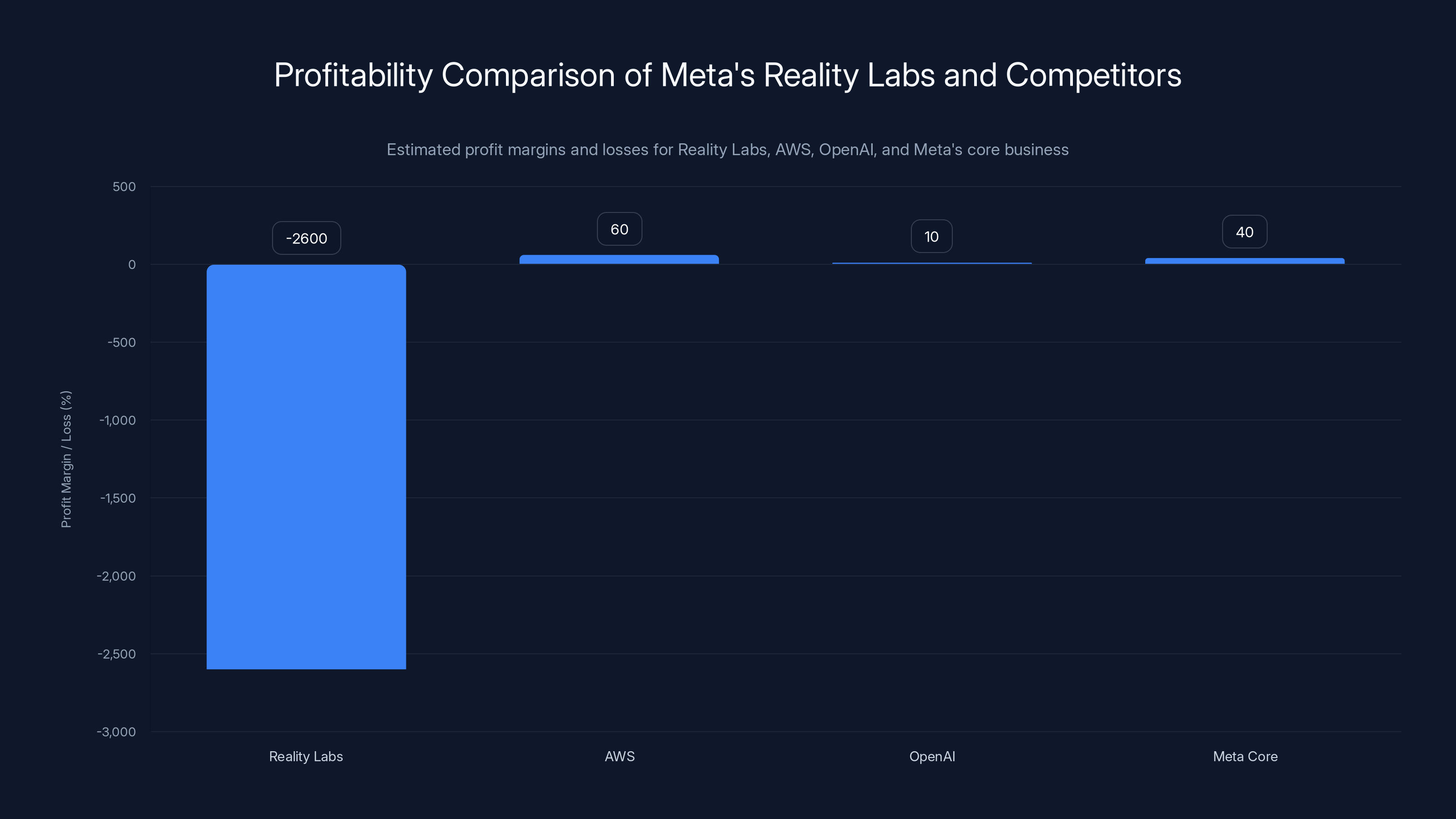

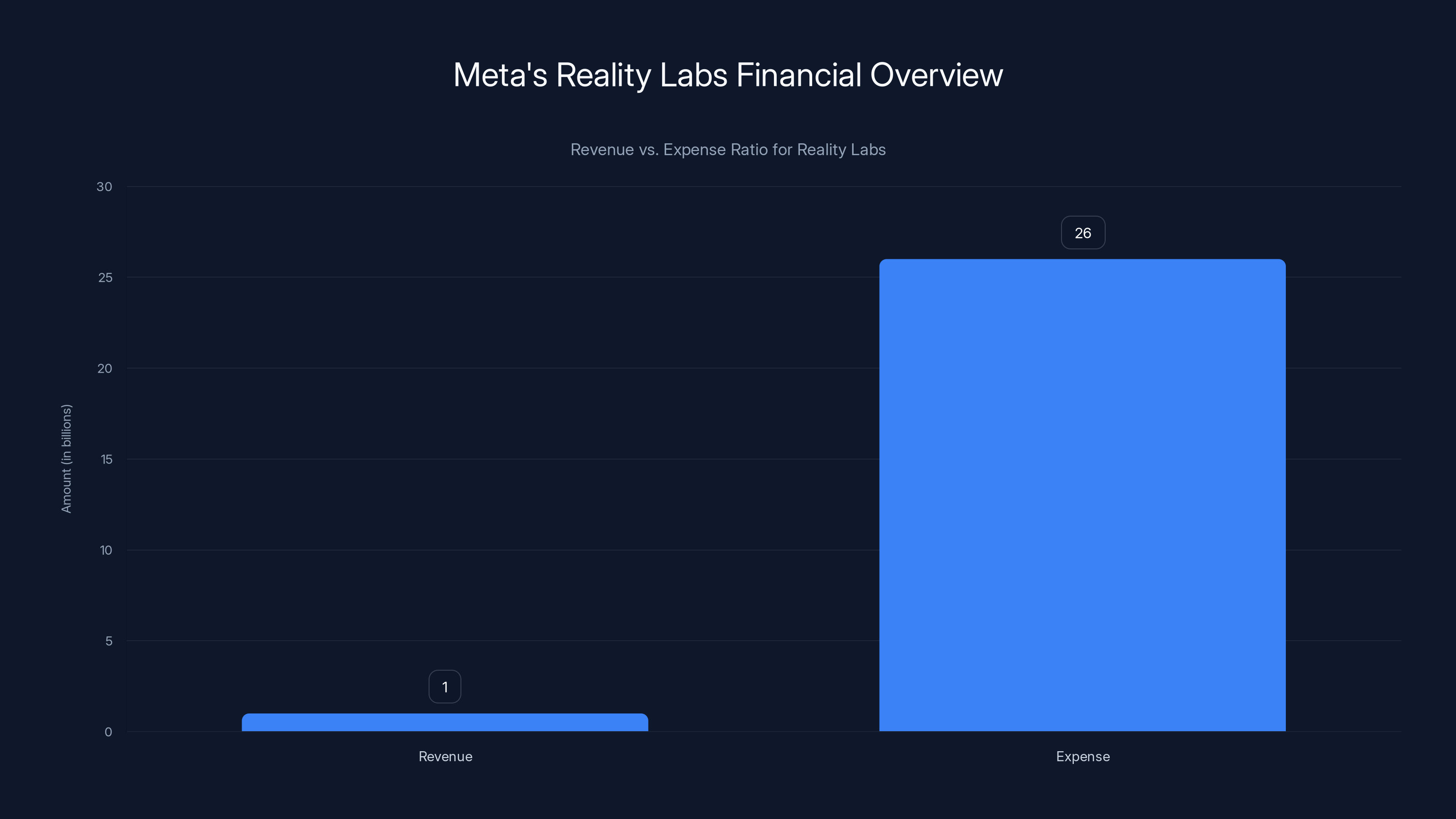

Reality Labs operates at a loss of 2600% per revenue dollar, starkly contrasting with AWS's 60% and Meta's core 40% profit margins. Estimated data.

Why Meta Spent Billions on VR (And What Went Wrong)

Understanding Meta's VR collapse requires understanding how it started. The company didn't just wake up one day and decide to build a metaverse. The logic was actually compelling at first.

Meta spent decades building the world's largest social network. But by 2020, mobile had plateaued. Everyone had a smartphone. User growth was slowing. The only direction left was to evolve the platform itself—to create the next medium of human connection.

Enter the metaverse pitch: a persistent, 3D virtual space where billions of people could work, socialize, shop, and exist digitally. Not gaming—this was positioned as the future of computing itself. Like how the web replaced bulletin board systems, and mobile replaced the web, the metaverse would replace both.

The investment strategy was clear: dominate the hardware (VR headsets), control the platform (metaverse infrastructure), and capture the network effects. Meta bought Oculus in 2014 for

That's roughly the GDP of some countries. All aimed at a world that, it turned out, most people didn't actually want to live in.

Several factors collided to create the current crisis:

The Adoption Problem: VR headset sales never approached smartphone levels. In 2024, the global VR headset market shipped roughly 12 million units—compared to 1.2 billion smartphones. The installed base of VR users remained tiny. Games performed better than expected, but mainstream adoption? It didn't happen.

The Content Problem: Unlike smartphones, which had apps for literally everything, VR lacked a killer application beyond gaming. There was no VR Tik Tok. No VR Slack. No "must have" social network that justified the hardware investment. People wore VR headsets for 20 minutes at a time, then took them off.

The Comfort Problem: Headsets were heavy, uncomfortable, and caused motion sickness. They required enough physical space that most people couldn't use them in apartments. They made social interaction awkward—your face was hidden, your body was absent, and you looked ridiculous.

The Fundamental Mismatch Problem: Most of what humans do online doesn't require immersion. Checking Slack? Reading news? Watching videos? Video calls? All of these work better on 2D screens. Trying to force 3D spatial environments onto these use cases was like forcing everyone to view websites through a virtual reality headset. Sure, you could do it. But why would you?

Meanwhile, the company's AI strategy—led by Yann Le Cun—was producing better results with significantly less investment. Large language models, image generation, and other AI applications had clear use cases and real user adoption. The ROI was obvious. VR? Not so much.

By 2024, even inside Meta, the question became impossible to ignore: why are we spending $13.5 billion annually on a technology that 99% of people don't use, to build a world that users explicitly don't want?

Meta's investment in VR and AR technologies increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, reaching $15 billion annually by 2024. Estimated data.

The Reality Labs Reckoning: What the Numbers Actually Say

Meta doesn't break out exact profitability data for Reality Labs, but the financial picture is grim enough that analysts have pieced it together from earnings calls and public statements.

Since 2021, Meta has disclosed cumulative losses from Reality Labs of over

That's a revenue-to-expense ratio of approximately 1:26. For every dollar in revenue, Meta spent $26.

For comparison, Amazon Web Services—Meta's AI competitors like Open AI, and even Meta's core advertising business all operate at positive unit economics. AWS has 60% margins. Open AI is profitable. Meta's core social media business generates 40%+ profit margins.

Reality Labs wasn't just unprofitable. It was catastrophically unprofitable at a scale that made even patient investors uncomfortable.

Here's the brutal logic that finally forced Meta's hand:

Hardware Sales Flatlined: Meta Quest headsets sold well compared to competitors, but the total addressable market was constrained. Most VR headsets go to gamers and enthusiasts—the same 30-40 million people worldwide who were already interested in VR. Mainstream adoption meant selling to people who didn't want VR, and no amount of marketing budget could change that.

Enterprise Never Materialized: Meta bet big on enterprise use cases—virtual offices, training simulations, design collaboration. But actual enterprise adoption was minimal. Companies like Microsoft with Holo Lens focused on AR (less immersive, more practical). Virtual meeting rooms never caught on because video calls worked better. Training VR was niche and expensive. The enterprise metaverse? It existed mostly in pitch decks.

The Attention Economy Stayed 2D: Tik Tok became the fastest-growing platform not by inventing new media, but by perfecting the consumption of short-form video. You Tube remained the dominant video platform using flat screens. Twitter/X never needed 3D spaces to engage billions. The attention economy had zero demand for immersion. Users wanted content they could consume while scrolling on the toilet, not content that required 10 pounds of hardware strapped to their head.

Competing VR Headsets Gained Market Share: Instead of Meta achieving monopoly dominance, competitors like Apple Vision Pro ($3,500), Play Station VR2, and Chinese manufacturers offered alternatives. Apple's expensive, technically superior headset proved there was no mass market—it sold in tens of thousands, not millions. This validated what the data was saying: VR remained a niche product.

By late 2024, Meta's board essentially told Bosworth and Zuckerberg: the metaverse gamble has failed. We can't justify $13+ billion annual spending on a vision that consumers have rejected. What do we actually do?

Andrew Bosworth's Pivot: "Let VR Be What It Is"

This is where Andrew Bosworth's honest assessment becomes important. Bosworth is one of Meta's oldest employees and strongest believers in VR. If anyone had incentive to keep defending the metaverse vision, it was him. Instead, he did something rarer in tech leadership: he admitted the strategy was wrong.

"We're going to let VR be what it is," he essentially said. Not what we want it to be. Not what the roadmap says. Not what the sci-fi movies promised. What it actually is and what people actually want to use it for.

This statement is doing a lot of work. Let's decode it:

"Let VR be what it is" = VR is a gaming and entertainment platform first. It's really good at that. But it's not the future of all computing.

"Stop forcing everything into 3D" = The metaverse vision tried to make every application work in VR. VR offices. VR shopping. VR social networks. VR everything. But most of these use cases suck in VR and work better on flat screens. Accept this reality instead of fighting it.

"Focus on genuine strengths" = VR excels at immersive gaming, simulation, training, and entertainment. Build on these strengths instead of trying to solve problems that users never asked VR to solve.

"Stop the money hemorrhaging" = Shut down projects with no realistic path to profitability. Stop funding R&D on technologies (like neural interfaces) that are 20+ years from consumer viability. Invest in what users actually want today.

The immediate consequence: Meta laid off thousands of Reality Labs employees. The company cut budgets across the division. Projects were cancelled. The moonshot mentality—spending billions to achieve sci-fi visions—ended.

What's interesting is that this pivot doesn't mean Meta is abandoning VR entirely. It means the company is being strategic about where VR makes sense.

Reality Labs had a revenue-to-expense ratio of 1:26, indicating significant financial losses in pursuit of the metaverse vision. Estimated data.

The New VR Reality: Gaming, Not the Metaverse

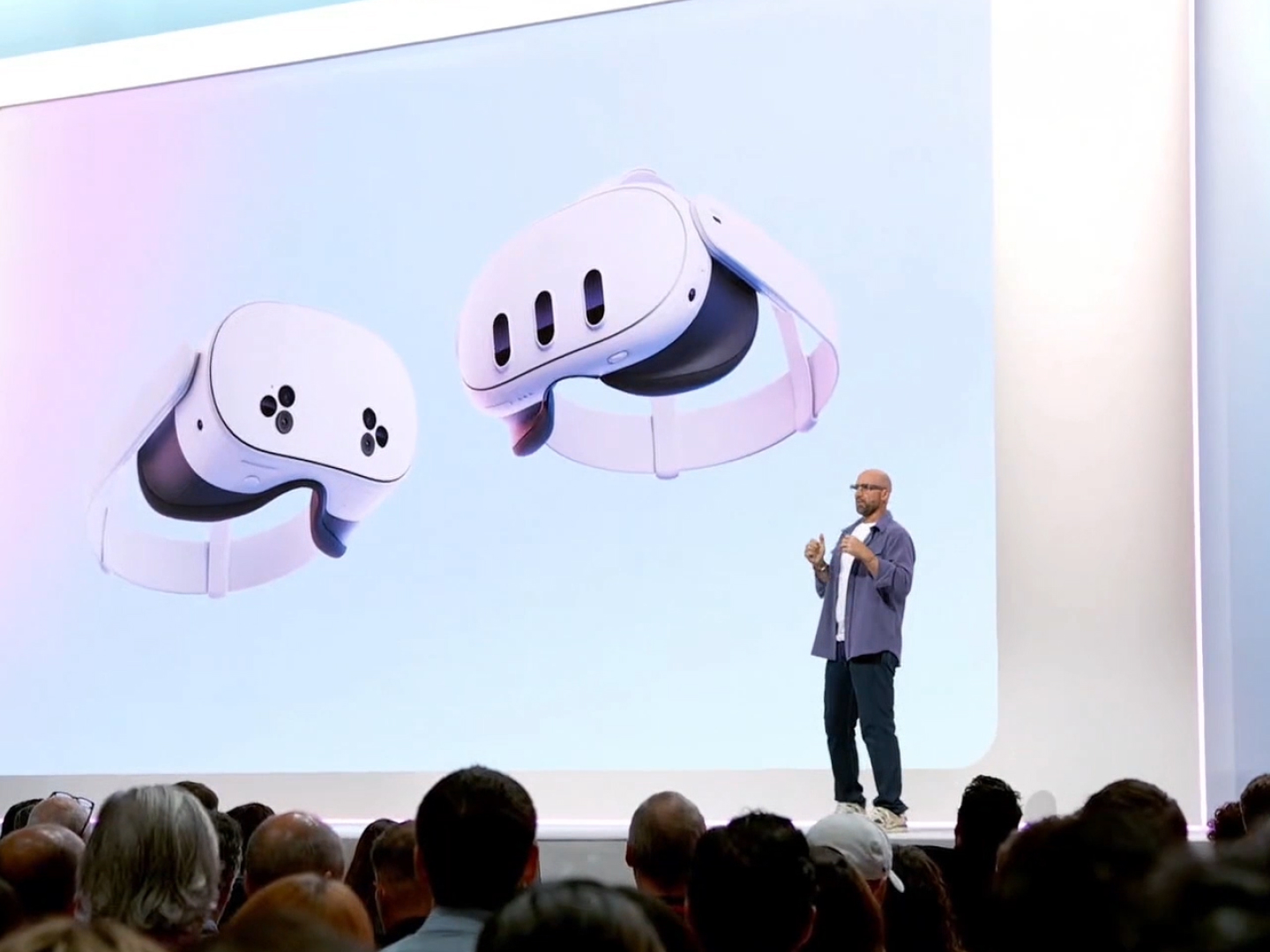

After years of "metaverse this" and "spatial computing that," Meta's actual VR strategy is far more pragmatic: double down on what already works—gaming.

The Meta Quest headset ecosystem has achieved something genuinely impressive within its niche. Games like Beat Saber, Half-Life: Alyx, and Resident Evil 4 VR are legitimately excellent. They make people buy headsets. They keep people engaged. The economics on gaming actually work.

So Meta's new strategy: be the Play Station of VR. Own the gaming platform. Build developer relationships. Fund games that drive hardware sales. Take a percent of software revenue. This is a proven business model that actually generates positive unit economics.

It's a massive strategic retreat from metaverse ambitions to, essentially, "we're a gaming company." But it's also honest. It acknowledges what actually drives VR adoption.

Under Bosworth's leadership, Meta is also exploring more practical VR applications:

Fitness and Health: VR workouts became genuinely popular during lockdowns. Games like Fit XR and Beat Saber doubled as exercise. Building on this trend costs less than building a metaverse and has real users.

Content and Entertainment: VR concerts, experiences, and entertainment content have an audience. Meta is investing here, but on a realistic scale—not betting the company.

Enterprise Training: Certain use cases—medical simulation, military training, industrial safety—genuinely benefit from VR. Meta is targeting these high-value, specialized applications instead of trying to replace office work.

Social Gaming: Asymmetric VR experiences—where VR players interact with flat-screen players—are emerging. This expands the addressable market without requiring everyone to buy headsets.

None of these are the trillion-dollar metaverse fantasy. But they're all sustainable businesses with real users and positive economics.

The Broader Reckoning: Why the Entire Industry Got VR Wrong

Meta's metaverse collapse isn't just a Meta problem. It's revealing something deeper about how the tech industry evaluates emerging technologies.

The playbook goes like this:

- New technology emerges (VR, AR, blockchain, AI, etc.)

- Tech industry gets excited about potential

- Industry leaders make massive bets based on vision, not evidence

- Marketing teams hype the vision to justify investments

- Users, however, adopt the technology for actual use cases, not imagined ones

- If actual use cases don't exist or are smaller than projected, investors eventually realize they've bet billions on a technology that doesn't solve real problems

- Strategy changes (usually painfully)

VR followed this script exactly. In 2020-2021, the tech industry convinced itself that immersive 3D virtual worlds were inevitable. The vision was so compelling that companies like Meta, Microsoft, and others committed massive resources to it.

But here's what the industry got wrong: innovation doesn't follow vision. It follows user behavior.

Users didn't ask for metaverse offices. They asked for better video conferencing, which is why Zoom won during the pandemic. Users didn't want to socialize in VR. They wanted to communicate efficiently, which is why Slack and Discord thrived. Users didn't need to visit virtual stores. They wanted faster checkout and better recommendations, which is why Amazon dominates.

Whenever a company invests based on what the future should be instead of what users actually want now, there's a mismatch. And that mismatch eventually resolves, usually via layoffs and strategy reversals.

This has massive implications for how we think about emerging technologies. When you see companies making billion-dollar bets on AI agents, autonomous everything, or the next big thing, the question to ask isn't "is this the future?" It's "are users actually adopting this for real problems?"

Open AI didn't have to imagine demand for Chat GPT. Millions of users signed up on day one because it solved a genuine problem: people wanted to interact with AI in natural language. That's different from the metaverse, where demand had to be created through marketing and vision, rather than discovered through actual user behavior.

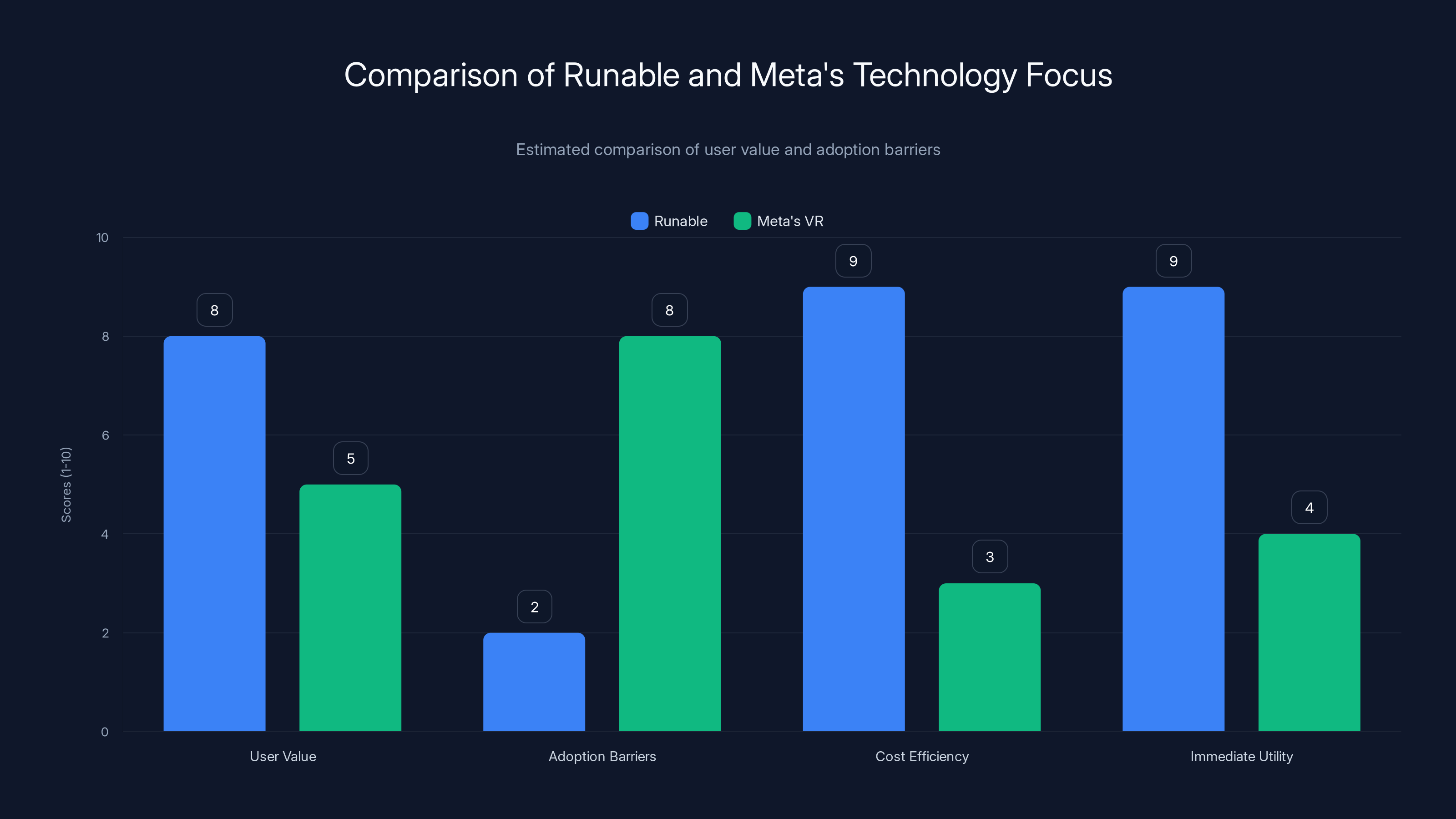

Runable scores higher in user value, cost efficiency, and immediate utility compared to Meta's VR, which faces higher adoption barriers. (Estimated data)

AI: The Direction Meta Actually Pursued Instead

While VR consumed all the attention and most of the budget, something more important was happening inside Meta: AI advanced dramatically, almost under the radar.

When Bosworth was overseeing Reality Labs, Yann Le Cun, Meta's Chief AI Officer, was quietly building some of the world's best AI models. Llama models, open-source AI infrastructure, AI chips, and research that rivaled Open AI and Google.

The contrast is striking: every dollar Meta spent on metaverse research produced nothing of value to users. Every dollar Le Cun spent on AI research produced models that companies worldwide now use and build on.

Meta's 2025 strategy makes this shift explicit. The company is pivoting toward AI agents—AI systems that can take actions, interface with applications, and help users work more effectively. This is far more practical than asking everyone to strap on a headset and live in a digital world.

AI agents can work on any platform. A smartphone. A computer. A headset. A watch. They don't require new hardware adoption to be valuable. They solve problems users already have. And they generate value that companies will pay for.

The Human Cost: Thousands of Layoffs

It's easy to discuss strategy at 30,000 feet. It's harder to acknowledge that Meta's metaverse pivot meant thousands of people lost their jobs.

In 2023 and 2024, Meta laid off approximately 10,000 people from Reality Labs and related divisions as the company restructured. These weren't abstract budget cuts. They were engineers, designers, researchers, and executives who had devoted years to the metaverse vision, who believed in it, who had moved their families to support it.

Many of these people had no responsibility for the strategic failure. They were executing leadership's vision. Then that vision changed, and they were laid off.

This is the hidden cost of betting billions on a technology roadmap that doesn't have user demand behind it. It's not just wasted money. It's human careers disrupted, years of work rendered irrelevant, and a massive loss of institutional knowledge.

For people building careers in tech, Meta's VR layoffs offer an important lesson: the most compelling vision isn't always the right bet. User adoption matters more than leadership enthusiasm. Technology that solves real problems for millions of people (like AI) tends to create more sustainable jobs than technology built to match a sci-fi fantasy.

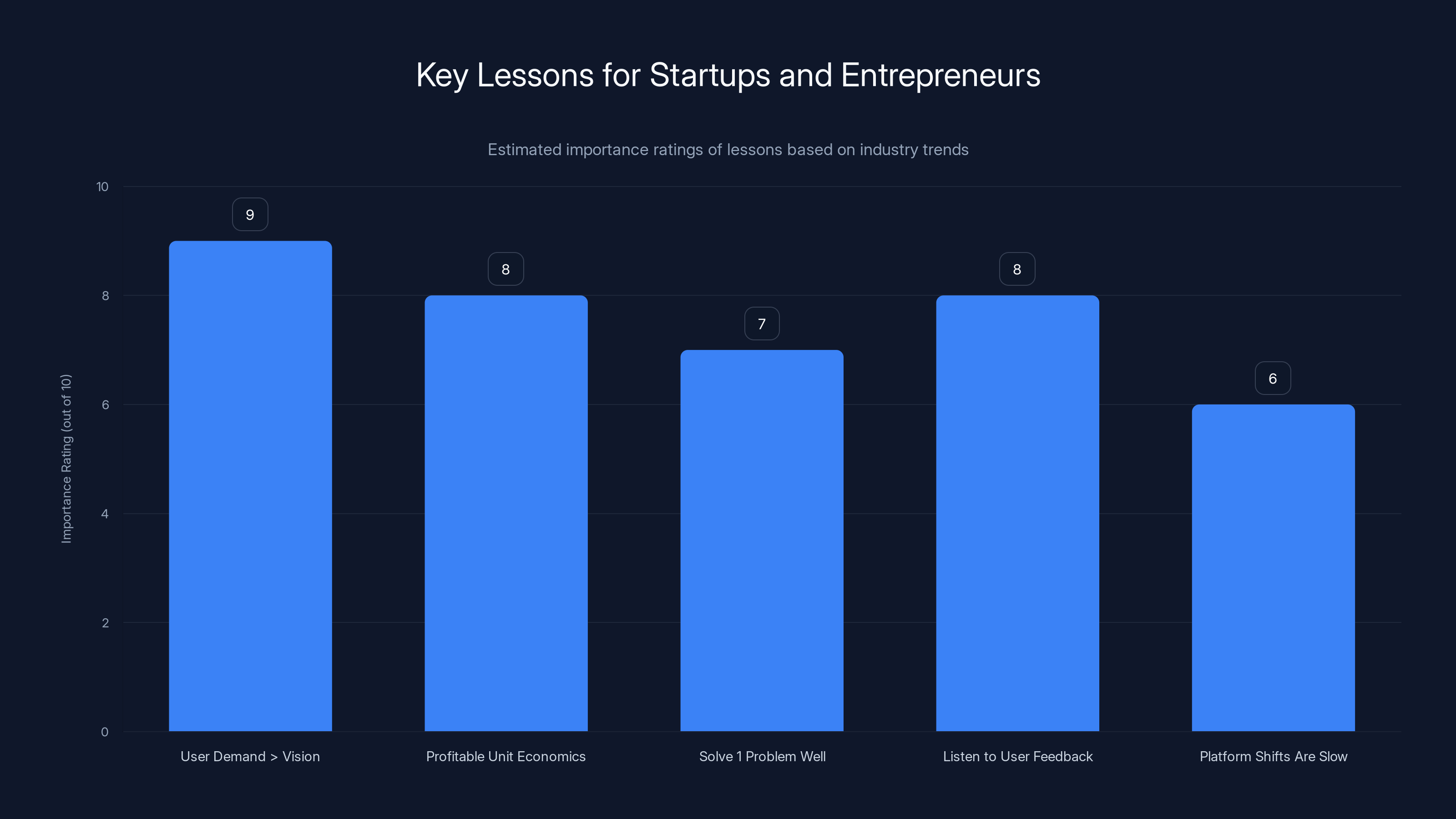

User demand and profitable unit economics are critical lessons for startups, with high importance ratings. Estimated data based on industry insights.

What This Means for VR's Future (The Realistic One)

Here's an important distinction: Meta's metaverse collapse doesn't mean VR is dead. It means VR is becoming normal.

VR will continue to be used for gaming, entertainment, training, and specialized applications. It's genuinely useful in those spaces. But it won't be the "next computing platform" that replaces smartphones or the internet. It will be another tool in the toolkit—valuable in specific contexts, not universal.

This is actually healthier for VR long-term. Technologies grow fastest when they find their niche and serve it extremely well, rather than trying to be everything.

Consider the smartphone: it didn't kill computers. Computers are still used more than ever, just differently. VR will follow a similar trajectory. It won't replace flat screens. It will coexist with them, useful for specific applications where immersion adds value.

The question for VR companies going forward:

What does VR actually do better than existing technologies?

For gaming and entertainment: immersion creates emotional engagement that flat screens can't match. That's a huge advantage.

For training: VR allows practice of dangerous or expensive scenarios. A pilot can crash a virtual plane a thousand times. A surgeon can practice rare procedures. A soldier can train for combat. These use cases are genuinely valuable.

For design and spatial understanding: some work—architecture, engineering, interior design—benefits from 3D visualization. This is real.

For socializing and working: not really. Video calls work fine. Flat screens are better for reading and typing. Office work in VR is worse, not better.

Meta's new strategy essentially says: pursue the applications where VR wins. Abandon the ones where it loses. This is harder than chasing a grand vision, but it's more honest and ultimately more sustainable.

The Apple Vision Pro: A Different Bet

While Meta was retreating, Apple was making its own VR bet—the Vision Pro, a $3,500 spatial computing device released in early 2024.

Apple's strategy is instructive because it's different from Meta's metaverse vision. Apple isn't trying to replace your i Phone or computer. It's positioning Vision Pro as a new medium alongside existing platforms. Use it for specific applications—movies, 3D content, productivity tools. Don't live in it.

Early sales suggest this positioning is smarter than Meta's metaverse vision. Vision Pro isn't a mass-market device, but it's also not failing—it's succeeding within its niche. Apple manages expectations. It prices for exclusivity. It focuses on what the device does well rather than trying to do everything.

The contrast is revealing: Meta's "metaverse for everyone" vision failed. Apple's "spatial computing for specific applications" vision is succeeding, albeit at a much smaller scale and higher price point.

This suggests that VR's long-term value is in specialized applications for people who need them, not in a universal platform for everyone.

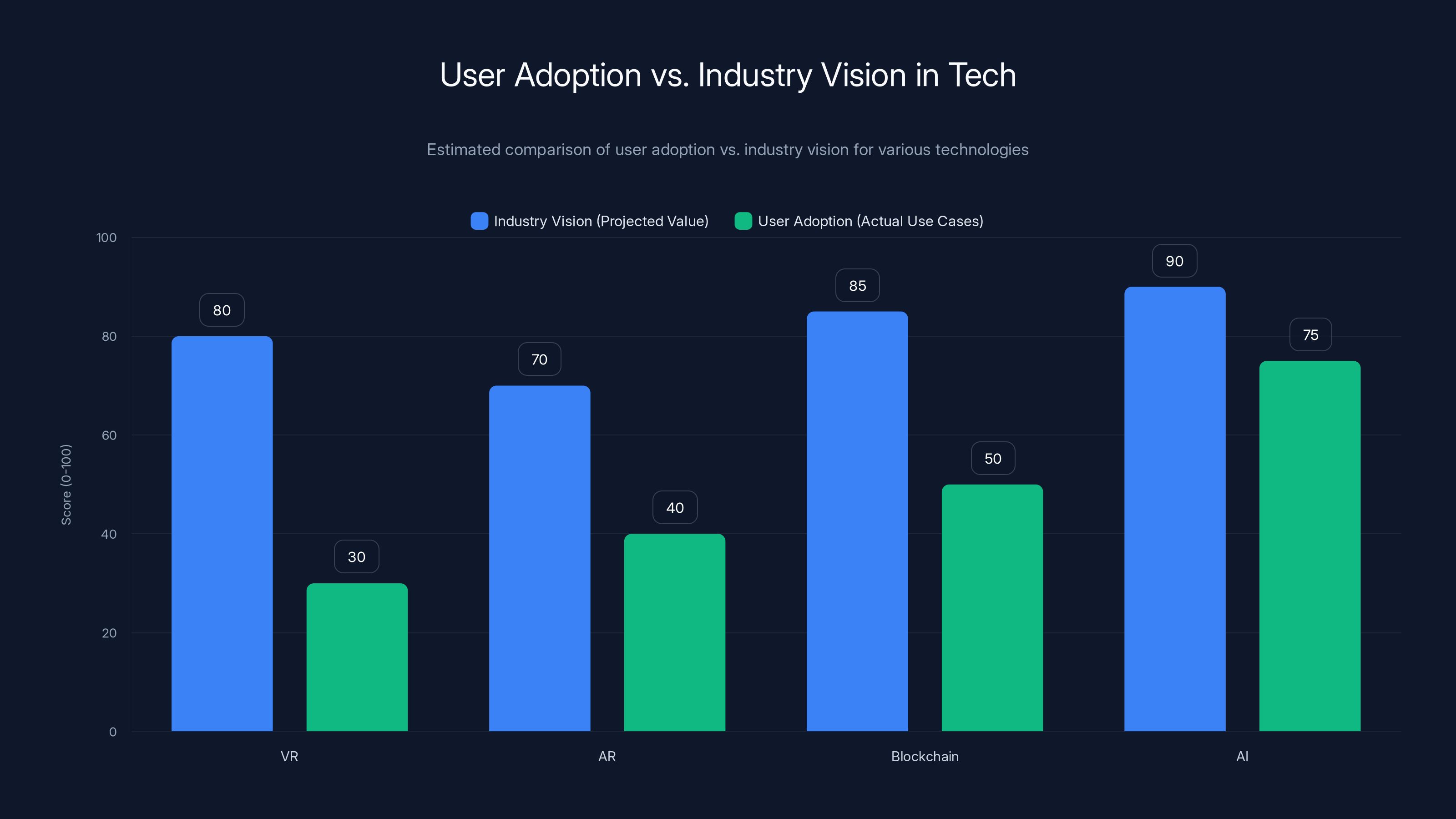

Estimated data shows a significant gap between industry vision and user adoption for emerging technologies. VR and blockchain have the largest discrepancies.

Industry Implications: The End of Moonshot Investing (Maybe)

Meta's VR pivot has ripple effects across tech. It signals that even the biggest companies with the deepest pockets can't force technological adoption if users don't want it.

This challenges the tech industry's favorite narrative: "if we build it big enough, spend enough money on it, and have visionary leaders behind it, we can make any technology succeed."

Turns out, no. You can't.

That doesn't mean moonshot thinking is over. But it means companies are (or should be) more careful about which moonshots to pursue. Projects should have a path to user adoption. They should solve genuine problems. They should have evidence of market demand, not just vision.

The best tech companies—Apple, Amazon, Open AI—tend to do this. They release products that solve real problems and let users decide if they want them. They don't bet billions on a vision and then try to convince users they want it.

What's Next: Meta's Actual VR Roadmap

So what is Meta actually building now that the metaverse vision is shelved?

Bosworth and the Reality Labs team are focused on:

AI-Powered Assistants: Imagine putting on a VR headset and having an AI assistant that understands context, can help you work, can interface with applications. This is more practical than a metaverse and actually leverages VR's unique capabilities.

Better Hardware at Lower Costs: Instead of building expensive flagship headsets, Meta is focusing on making VR hardware cheaper and more comfortable. Reduced cost means higher adoption in the gaming market.

Cross-Platform Interoperability: Rather than forcing everything into Meta's metaverse walled garden, Meta is exploring how VR experiences can interoperate with flat-screen platforms and other ecosystems.

Specialized Applications: Healthcare VR, education VR, professional training VR. These markets exist and have real customers willing to pay.

Peripheral Technologies: Hand tracking, eye tracking, haptic feedback. These make VR more intuitive and useful for specific applications.

None of this is revolutionary. None of it matches the metaverse hype. But all of it has realistic potential because it solves problems users actually have.

Lessons for Startups and Entrepreneurs

Meta's VR lesson is worth $50+ billion to learn from anyone else's perspective. Here are the key takeaways for anyone building or investing in emerging technologies:

1. User Demand > Vision: If users aren't asking for your technology, no amount of marketing will create demand at scale. Open AI didn't have to convince people to try Chat GPT. It was immediate, organic demand. If your technology requires massive education and adoption campaigns, it's a sign users might not want it.

2. Profitable Unit Economics Matter Early: Meta could afford to lose billions because of its advertising business. Most companies can't. If you're building a technology company, you need a path to positive unit economics within a reasonable timeframe. Infinite losses on infinite growth isn't sustainable.

3. Technology That Solves 100 Problems Badly Loses to Technology That Solves 1 Problem Well: The metaverse tried to do everything. AI agents try to do everything. Tech that actually succeeds does something extremely well for a specific use case.

4. Listen When Users Reject Your Vision: If people aren't adopting your technology despite massive marketing and investment, the problem might not be execution. The problem might be the vision itself.

5. Platform Shifts Are Slower Than Predicted: Everyone expected VR to follow the same adoption curve as smartphones. It didn't. Platform shifts take longer and involve more friction than tech leaders predict. Don't underestimate the stickiness of existing platforms.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Meta's VR pivot represents a broader maturation in how the tech industry thinks about technology adoption and product strategy.

For decades, tech companies have operated on a narrative of "build the future." A visionary leader sees what's possible, commits massive resources, and makes the future inevitable through sheer will and capital.

Sometimes this works. But sometimes—increasingly often—it doesn't.

The future isn't built top-down by vision and funding. It's built bottom-up by actual user adoption. Technologies that create value first tend to attract adoption. Adoption creates infrastructure. Infrastructure creates ecosystems. Ecosystems create the "future" that visionary leaders predicted.

But you can't shortcut this process by spending enough money. You can't force adoption. You can't will a metaverse into existence.

What you can do is build products that solve real problems, let users decide if they want them, and scale based on actual demand rather than projected vision.

Meta finally learned this lesson. It only cost $50+ billion and thousands of jobs to do it. That's an expensive way to learn something that the market was trying to teach all along.

The Role of Runable in Modern Automation

As companies like Meta refocus their technology strategies on what actually drives user value, tools like Runable are gaining traction for a different reason: they solve practical problems today.

Where Meta spent billions on the metaverse, platforms like Runable focus on AI-powered automation for documents, presentations, reports, and workflows—the boring infrastructure that actually keeps companies functioning. Runable's approach at $9/month demonstrates that not every tech innovation needs to be a billion-dollar moonshot. Sometimes the most valuable tools are the ones that solve immediate problems efficiently.

The contrast is instructive: Meta's VR ambitions required hardware adoption, ecosystem building, and consumer behavior change. Runable's value proposition works today, with existing tools and workflows. Users sign up not because of vision, but because it saves them hours on repetitive tasks.

This is why Runable represents the future that Meta is only now moving toward: practical AI that integrates with how people actually work, not technology that asks people to change their behavior.

Use Case: Generate automated reports and presentations in minutes instead of hours, letting your team focus on strategy instead of formatting.

Try Runable For Free

How Meta's Shift Impacts the Broader Tech Landscape

Meta's pivot from metaverse to practical AI applications has broader implications for the entire tech industry.

When the world's most valuable social media company—with a market cap over $1 trillion—signals that it's shifting investment from a moonshot vision to practical AI tools, other companies take notice. This isn't just a Meta correction. It's a signal about where real value lies.

We're seeing this play out: tech companies are increasingly funding AI agents, automation tools, and productivity solutions rather than building new platforms from scratch. These are tools that integrate with existing workflows rather than asking users to adopt entirely new mediums.

This is the opposite of what Meta was trying to do with the metaverse. Instead of asking everyone to move to a new platform, companies are building tools that work within the platforms people already use.

The Future of Virtual Reality (Without the Metaverse)

So where does VR go from here?

The technology itself hasn't changed. VR is still immersive, still powerful for certain applications. But the narrative has changed. VR isn't the future of all computing. VR is a tool that's useful for specific problems.

Over the next 5-10 years, expect VR to mature into:

Niche Professional Markets: Surgery, architecture, engineering, military training. Places where VR's immersion and safety create genuine value. These markets are small but lucrative.

Gaming and Entertainment: This was always VR's strongest market. As hardware improves and costs decrease, gaming VR will grow. But it won't be half the internet living in virtual worlds—it will be gamers enjoying immersive experiences.

Hybrid Experiences: Content that works on both VR and flat screens. As creators learn to build for both mediums, VR becomes an option rather than the primary platform.

Hardware Innovation: Better displays, lighter weight, more comfortable. The hardware that works in 2025 will look primitive by 2035. But the innovations will be incremental, not revolutionary.

Integration With AI: VR paired with AI agents could create useful applications. Imagine a VR interface where an AI assistant understands context and can help you work. This is more practical than a metaverse.

None of this is the "future of humanity" narrative that dominated 2020-2023. But it's honest. It's sustainable. And it's probably worth investing in because it's based on real demand rather than vision.

Conclusion: From Vision to Reality

Andrew Bosworth's statement—"we're going to let VR be what it is"—will probably be remembered as the moment when tech's "metaverse craze" ended. Not because VR failed, but because the industry finally accepted what users had been telling it all along: VR is a powerful tool for specific applications, not a universal platform that should replace everything.

Meta's $50+ billion investment in the metaverse produced nothing of lasting value for users. But it did produce something valuable for the tech industry: a expensive, public reminder that vision alone can't overcome market reality.

The companies that will thrive in the next decade won't be the ones chasing the biggest visions. They'll be the ones solving the most practical problems. They'll be building tools that work today for real use cases. They'll be listening to users instead of telling users what they should want.

This is what Meta is finally doing with AI. This is what companies like Runable have been doing all along. And this is where the real value in technology actually lies.

The metaverse was a beautiful vision. It just wasn't what people wanted. Now that Meta has accepted this reality, the company can focus on what actually matters: building technology that solves real problems, creates real value, and has real users.

That's a lesson worth $50 billion to learn.

FAQ

What is the metaverse and why did Meta invest so heavily in it?

The metaverse was Meta's vision of a persistent 3D virtual world where billions of people could work, socialize, shop, and live digitally. Meta invested $13.5+ billion annually because executives believed it represented the next evolution of computing, similar to how the internet replaced traditional media or how mobile replaced desktop computing. However, actual user adoption remained minimal, and the company eventually acknowledged that this vision didn't align with what users actually wanted or needed.

Why did Meta lay off thousands of VR employees?

Meta laid off approximately 10,000 people from Reality Labs and related divisions because the metaverse vision was losing billions annually—Reality Labs had a revenue-to-expense ratio of roughly 1:26, meaning the division spent $26 for every dollar in revenue. With mounting losses and stalled user adoption, Meta's leadership decided to restructure and refocus on more practical applications of VR rather than continuing to fund an unprofitable moonshot. The layoffs represented a painful but necessary correction from an unproven business model.

What does "let VR be what it is" actually mean?

Bosworth's statement means accepting VR for its actual strengths—gaming, entertainment, training, and specialized professional applications—rather than forcing it to become the universal computing platform that the metaverse vision promised. Instead of trying to replace all computing through immersive 3D environments, Meta is now focusing on building VR applications where immersion genuinely adds value and users actually want to use the technology.

Is VR still valuable despite the metaverse failure?

Yes. VR remains genuinely valuable for specific applications: gaming provides immersive entertainment that flat screens can't match; medical and military training save lives and reduce errors; certain professional applications benefit from 3D visualization. The failure wasn't VR technology itself—it was the belief that VR would eventually replace all computing. VR is useful, but it's one tool among many, not the future of everything.

How does Meta's VR pivot compare to Apple's Vision Pro strategy?

Meta tried to build an all-encompassing metaverse that would replace traditional computing. Apple positioned Vision Pro as a specialized device for specific applications (3D content, movies, productivity tools) without expecting it to replace i Phones or computers. Apple's approach manages expectations better—Vision Pro has succeeded within its niche without becoming a mass-market platform, which is more sustainable than Meta's "universal adoption" vision that failed to materialize.

What is Meta investing in instead of the metaverse?

Meta is now prioritizing AI agents, AI-powered assistants, and practical tools that integrate with existing workflows rather than requiring new platforms. Under Yann Le Cun's leadership, the company has built competitive AI models like Llama and is focusing on how AI can improve productivity and user experience on existing platforms. This represents a shift from building new computing mediums to optimizing existing ones with AI.

What lessons does Meta's VR collapse teach about emerging technologies?

The key lesson is that user adoption matters more than visionary promises. Technologies succeed when they solve real problems for users right now, not when they promise future value. Before betting billions on a technology, companies should ask: are users asking for this? Do they adopt it willingly? Does it solve genuine problems? Technologies like Chat GPT demonstrated immediate organic adoption because users actually wanted them, unlike the metaverse, which required marketing to create demand.

Could the metaverse eventually succeed with different approaches?

Possibly, but probably not as Meta originally envisioned it. The metaverse might find success as a specialized tool for specific communities (gamers, professionals in certain fields, social groups) rather than as a universal platform for everyone. Alternatively, the integration of VR with AI agents might create more practical applications that eventually drive adoption. But the vision of most people spending most of their time in a virtual world? That's likely not happening, regardless of technological advancement.

How much money did Meta lose on the metaverse?

Meta has disclosed cumulative losses from Reality Labs exceeding

What should companies learn from Meta's VR experience?

Companies should invest in technologies based on demonstrated user demand rather than visionary narratives. They should monitor unit economics and profitability early. They should accept when markets reject their vision and pivot accordingly. They should build tools that solve immediate problems rather than trying to force adoption of new computing paradigms. The most successful tech companies build on actual user behavior, not predictions about how behavior should change.

Related Topics You Might Explore:

- The Rise and Fall of Corporate Moonshots: Why Most Fail

- AI's Practical Success vs. VR's Failed Promise: A Comparison

- How Companies Recover From Failed Tech Bets

- The Future of Spatial Computing Without the Metaverse

- Why User Adoption Matters More Than Technology

- Meta's AI Strategy: The Pivot That Should Have Happened Sooner

Key Takeaways

- Meta lost $50+ billion betting on a metaverse vision that users never wanted or adopted

- CTO Andrew Bosworth's admission to 'let VR be what it is' marks the end of the metaverse era

- VR remains valuable for gaming, training, and specialized professional applications—just not as a universal computing platform

- Technology adoption follows user demand, not visionary promises; this lesson applies across emerging tech investments

- Meta now focuses on practical AI instead of the unprofitable metaverse, signaling broader industry correction

Related Articles

- Meta Quest Layoffs and VR's Future: Why Palmer Luckey's Optimism Might Be Misplaced [2025]

- Meta's Horizon Workrooms Shutdown: Why VR Meeting Rooms Failed [2025]

- Meta's VR Studio Shutdowns: What Happened to Reality Labs [2025]

- Meta's Quest 3 Horizon Integration Removal: What It Means [2025]

- Meta's VR Fitness Collapse: What Supernatural Users Lost [2025]

- Meta Kills Workrooms VR Meetings: What It Means for Remote Work [2025]

![Meta's VR Pivot: Why Andrew Bosworth Is Redefining The Metaverse [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-vr-pivot-why-andrew-bosworth-is-redefining-the-metave/image-1-1769200863115.jpg)