Robot Swarms That Bloom: The Future of Adaptive Architecture

Imagine walking into an office building where the walls come alive. Not in a creepy sci-fi way, but elegantly. Thousands of tiny robotic modules sense the sunlight streaming through the windows and gradually extend plastic sheets to create shade. A few hours later, as the sun moves and dims, they retract. It's not magic—it's biology meeting engineering.

This isn't theoretical anymore. Researchers at Princeton University built exactly this. They created something called the Swarm Garden, an array of interconnected mini-robots that respond to their environment like flowers following the sun. Each robot can extend or retract a thin plastic sheet, and when they work together, they create something that looks organic, feels intelligent, and actually solves real problems.

Here's why this matters: Most buildings are dumb. They were smart once—maybe they had a window you could open—but modern architecture is rigid, inflexible, and wasteful. Buildings don't adapt to how we use them. They heat and cool the same way whether it's 8 AM or 8 PM, whether there are ten people inside or a thousand. We pump energy into making buildings comfortable, and most of that energy gets wasted on spaces we're not even using.

Swarm robotics changes that. Instead of fixed walls and windows, imagine facades that breathe. Panels that open when it's hot and close when it's cold. Structures that adjust based on who's using them and what they're doing. This isn't just more efficient—it's a fundamentally different way of thinking about buildings.

The Princeton team didn't invent swarm robotics. But they did something important: they proved that swarm principles—the same ones that make ant colonies work—could be applied to architecture in practical ways. They built robots that cooperate without central command. Each bot has sensors and local knowledge. They communicate with neighbors. Together, they create something smarter than any individual robot could.

What's fascinating is where the inspiration comes from. Not from computers or algorithms, but from nature. Ants. Flocking birds. Honeycomb cells. Plants optimizing their shape to catch sunlight. For millions of years, biology solved the exact problems we're trying to solve: how to create structures that adapt, how to coordinate behavior without central control, how to use minimal energy to do maximum work.

This article dives deep into what swarm robotics actually is, how the Princeton team pulled it off, what the applications really are (beyond the hype), and what needs to happen before your office building becomes a garden of responsive robots. We'll look at the science of collective behavior, the engineering challenges, and the economic questions: Is this worth doing? When will it actually show up in buildings you'll work in?

Let's start with the basics and work our way up to the future.

TL; DR

- Swarm robotics at scale: Princeton's Swarm Garden uses 40 modular robots with light sensors and proximity detection to create adaptive building facades that respond to environmental changes in real time

- Nature-inspired design: The robots mimic collective behavior found in ant colonies, bird flocks, and plant growth patterns, achieving coordination without central control

- Real-world applications: Adaptive shading reduces energy waste, dynamic facades enable creative interior design, and swarm systems can be deployed horizontally or vertically across buildings

- Technical challenges remain: Current prototypes use plastic sheets prone to stress and buckling; future versions need sustainable materials, lower power consumption, and kirigami-inspired engineering optimizations

- Timeline to deployment: Real-world integration depends on architect collaboration, cost reduction, durability testing, and scaling from 40-unit prototypes to building-wide installations with thousands of modules

Deploying 40 SGbots could cost

What Is Swarm Robotics, Actually?

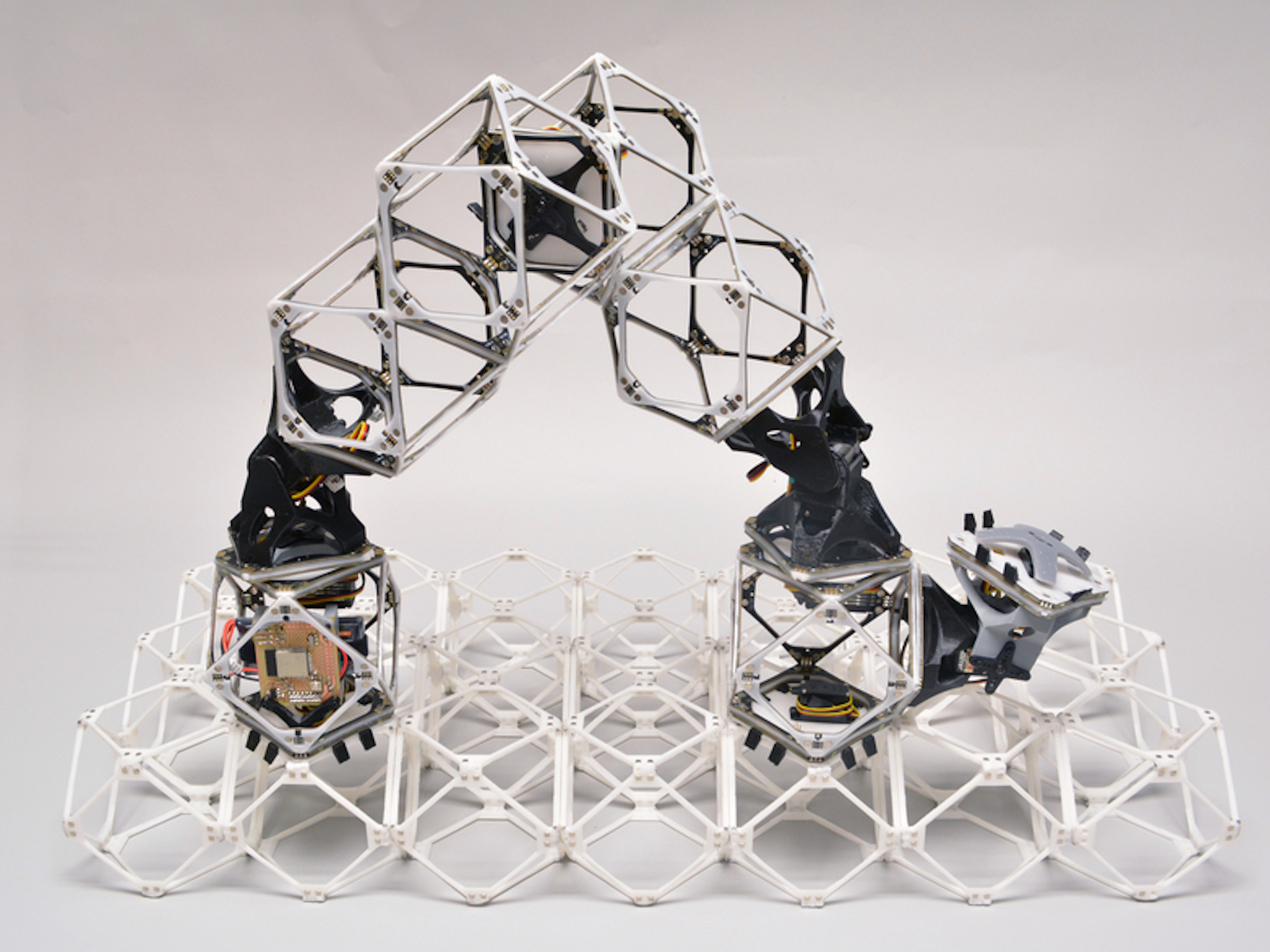

Swarm robotics is a field of study that sounds fancy but is fundamentally about one thing: getting lots of simple robots to cooperate and solve problems without anyone telling them what to do individually.

Think about an ant colony. No ant has a blueprint of the colony. No ant is in charge. Yet somehow, thousands of ants coordinate to build tunnels, find food, care for eggs, and defend against threats. They do this through simple local rules. An ant detects a pheromone trail and follows it. Another ant finds food and lays down a chemical signal. Chemical signals spread. More ants follow. Suddenly, a thousand ants are moving food across the colony floor in an organized line. No central authority. No board meetings.

That's the insight that drives swarm robotics: you don't need central planning if you design good local rules.

Each robot in a swarm is relatively simple. It has sensors. It has actuators. It has enough processing power to follow a few rules. The magic happens when you get hundreds or thousands of these simple robots in the same space, all following the same rules, all talking to their neighbors. Suddenly, you get emergent behavior. The swarm acts like a single intelligent agent, even though no individual robot is intelligent.

This has been proven in labs for years. In 2018, Georgia Tech researchers built robots that look like ants and can dig through simulated soil. Unlike single robots that get stuck and jam, these swarms adapt to the environment. When one robot hits an obstacle, nearby robots adjust their behavior. The swarm keeps moving. No bottlenecks.

The reason this works is elegant: complex behavior doesn't require complex instructions. You don't need a robot that "understands" digging. You need a robot that follows simple rules about how to move forward, how to detect resistance, and how to communicate with neighbors when stuck. Multiply that across a thousand robots, and you get digging behavior that's actually more efficient and robust than any single intelligent robot.

Biology has been running this experiment for millions of years. Fire ants create living bridges and towers. Honeybees coordinate hive construction with incredible precision. Starlings perform aerial dances with thousands of birds adjusting in real time. None of these creatures are "intelligent" individually. But collectively, they solve problems that require intelligence.

Swarm robotics transfers these principles to machines. Instead of pheromones, robots use Wi-Fi. Instead of genetic programming, they follow algorithms. Instead of evolution selecting the best strategies over millennia, engineers design the rules from scratch.

What's remarkable is that relatively simple rules produce surprisingly sophisticated behavior. Change one parameter in the algorithm—say, how far a robot communicates to neighbors—and the entire swarm behavior changes. Too short a communication range, and the swarm fragments into isolated clusters. Too long, and you get bottlenecks where robots clog up around central decision points. There's a sweet spot, and finding it is part of the engineering challenge.

For the Princeton Swarm Garden, the rules are simple: sense the light, communicate with neighbors, adjust your position. That's it. But applied across 40 robots with coordinated timing, you get something that looks alive.

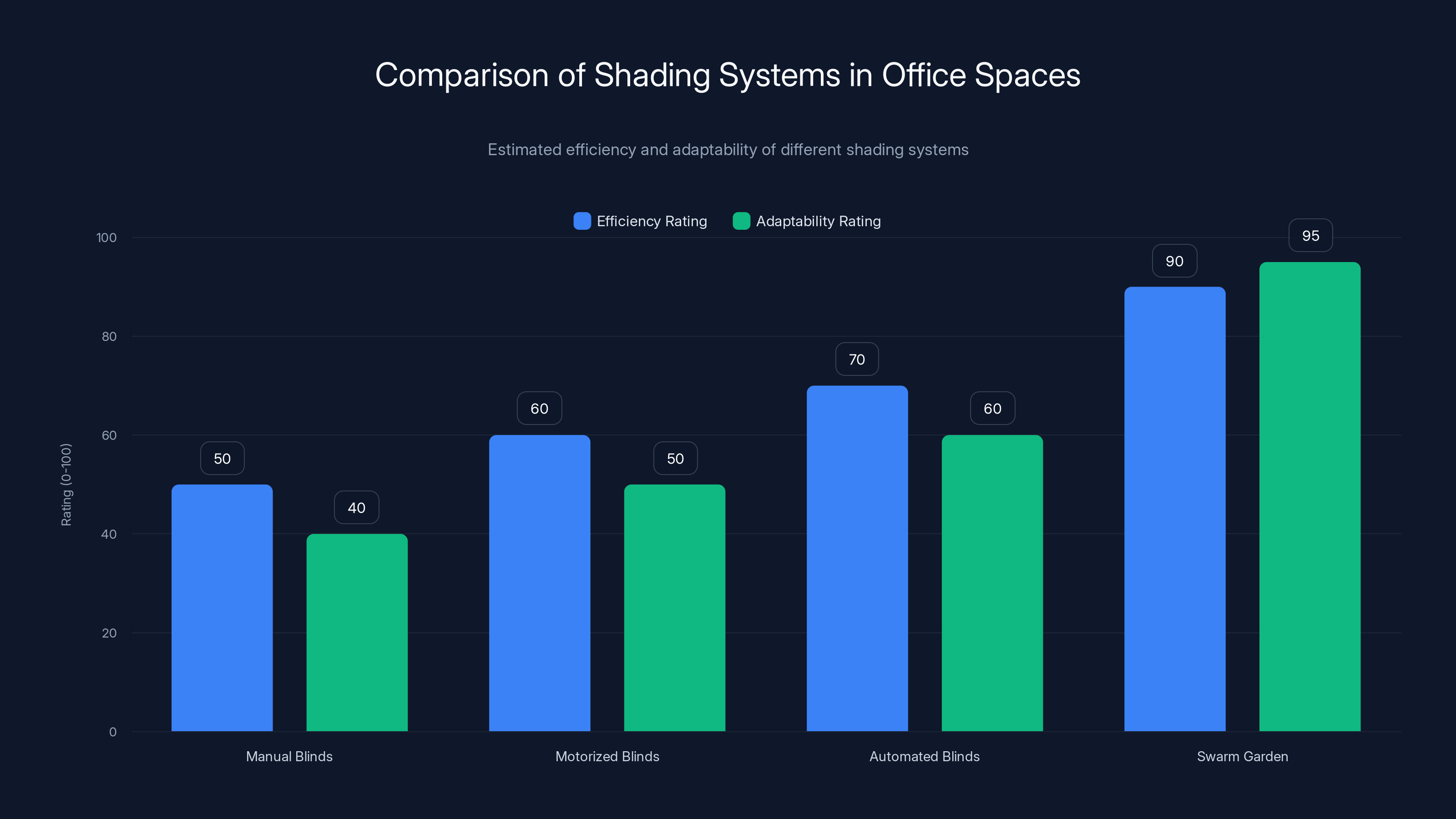

The Swarm Garden system shows the highest efficiency and adaptability ratings due to its independent and gradual shading capabilities. Estimated data based on system characteristics.

How Fire Ants Inspired the Swarm Garden

Fire ants are basically tiny hydraulic robots. They're flexible, they can change their behavior dramatically based on density, and they solve problems that seem to require centralized planning without any leadership structure.

When fire ants are spread out, each ant behaves like an individual. They forage, they explore, they move around. But when you get a few hundred ants in a confined space, something changes. They start linking to each other. They form chains, bridges, even floating rafts that can survive hours in water. During flooding, a fire ant colony will form a ball—a living raft—with ants on the outside sacrificing comfort to keep the ball waterproof. The ants on the inside? Safe and protected. No ant made that decision. No ant knows the strategy. It emerges from individual ants responding to pressure and proximity.

This phenomenon is called the phase transition. Below a certain ant density, you get individual behavior. Above it, you get collective behavior. It's like watching ice melt into water. The molecules haven't changed, but their interactions produce completely different properties.

Laboratory studies by researchers studying ant biomechanics have shown that this transition happens at about 4 to 5 ants per square centimeter. Below that, ants move independently. Above it, they lock together in tight groups and exhibit fluid-like properties. You can literally pour them like ants (one researcher actually did this in a famous viral video).

The Princeton team looked at fire ant behavior and asked: what if we designed robots that could exhibit similar phase transitions? Not by mimicking ants exactly, but by implementing the same principles: simple local rules, density-dependent behavior, and neighbor communication.

Fire ants also excel at traffic optimization. Ant trails are remarkably jam-free. When one ant encounters another, they don't collide. They somehow coordinate movement without any ant knowing the overall traffic pattern. They use chemical signals and local sensing. If an ant detects high traffic in one direction, it's more likely to explore an alternative path. This produces trails that are self-optimizing. Overloaded paths become less attractive. Underutilized paths become more attractive. The system balances itself.

That principle applied to buildings could mean hallways and rooms that reconfigure based on how they're being used. Traffic sensors could trigger structural changes. Crowded spaces could physically open up. Underutilized spaces could close down. Not through human decision-making, but through local algorithms running on each swarm module.

The other critical insight from fire ants: redundancy and resilience. An ant colony doesn't have a queen that controls everything (despite the name). The queen produces eggs. Workers do everything else. If you remove the queen, workers can't reproduce, but the colony still functions. If you destroy 10% of the colony, the remaining ants reorganize and keep going. There's no single point of failure.

Applied to building architecture, this means a dynamic facade doesn't depend on a central computer. If one robot fails, the others compensate. If communication goes down locally, robots still have sensors and can operate based on light levels and proximity. The system is graceful degradation—it keeps working even when parts fail.

Firefly synchronization offers another biological parallel. Fireflies in Southeast Asian forests produce synchronized flashing—thousands of insects lighting up in perfect unison. No firefly receives instructions. Each firefly has an internal rhythm. When a firefly sees nearby flashes, it adjusts its rhythm slightly. These local adjustments, repeated across thousands of fireflies, produce synchronized behavior.

This inspired algorithms called distributed synchronization. Applied to the Swarm Garden, it means each robot can synchronize with neighbors without central coordination. If you want all robots to "bloom" at once, you don't need to send a broadcast signal. Each robot sees its neighbors blooming and adjusts its own timing. The wave spreads organically.

The Princeton Swarm Garden: Technical Deep Dive

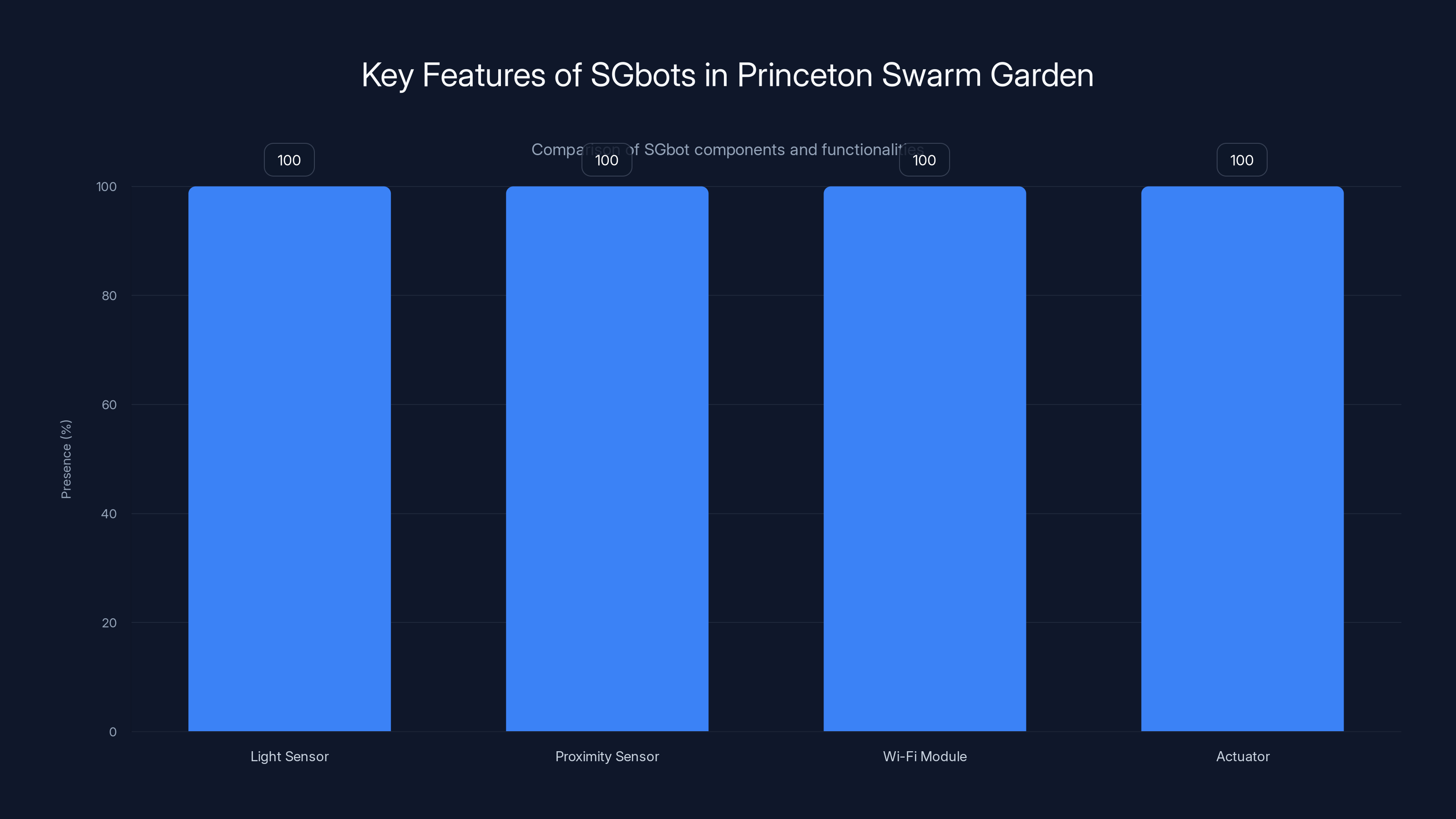

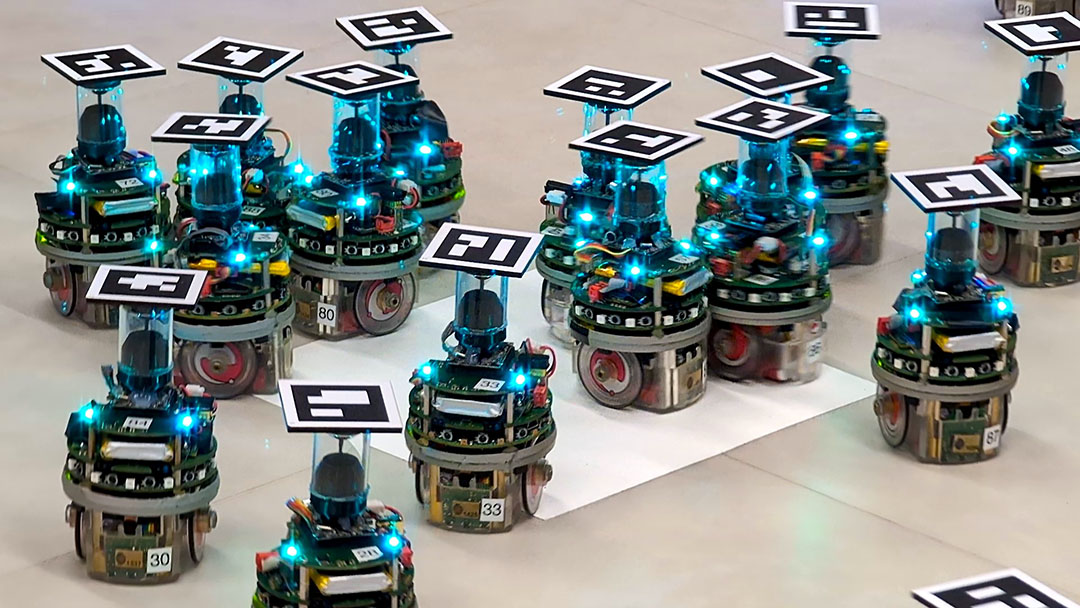

Now let's talk about what the Princeton team actually built. The Swarm Garden isn't a theoretical concept. It's 40 physical robots, called SGbots, with real sensors, real actuators, and real constraints.

Each SGbot is roughly the size of a smartphone standing upright. It has a back-facing light sensor to detect ambient lighting. It has a front-facing proximity sensor to detect neighbors. It has a Wi-Fi module to communicate with other robots and a central server. It has an actuator—basically a motorized mechanism—that can extend or retract a thin plastic sheet through a slot.

When the light sensor detects bright light (indicating strong sunlight), the robot extends the plastic sheet. When light dims, the sheet retracts. Multiple sheets working together create adaptive shading. In a bright office window, a wall of extended sheets blocks sunlight. As the sun moves and light decreases, sheets gradually retract, creating a gradient of shading.

The proximity sensor is critical for local decision-making. Each robot only knows about robots that are physically close. It doesn't know the state of distant robots. This keeps the computation local and the communication bandwidth reasonable.

The Wi-Fi network enables a shared communication protocol. This is important: it's not a centralized server telling robots what to do. It's more like a town square where robots can announce their state and listen to neighbors' announcements. Based on these announcements and local sensor data, each robot makes independent decisions.

The plastic sheets are the interface between digital behavior and physical reality. When a robot extends its sheet, it blocks light. When it retracts, light passes through. The sheets are thin enough to be lightweight but rigid enough to provide functional shading.

Here's where the engineering gets interesting: the sheets don't just slide in and out. They buckle. When extended, the sheet curves and folds in specific ways. This buckling is actually advantageous. It increases surface area. It creates interesting visual patterns. It distributes mechanical stress. But it also makes the system more complex. The team had to solve problems around mechanical resonance, stress concentration, and material fatigue.

The team ran two major case studies. First, they installed 16 SGbots on an office window and let them operate continuously for three days. The robots tracked light levels throughout the day. When morning sunlight was strong, sheets fully extended. As the sun climbed higher and light angles changed, sheets adjusted. By afternoon, as clouds moved in or the sun moved westward, sheets gradually retracted. The system maintained consistent interior light levels without human intervention.

Data from this trial showed that the swarm system tracked light changes more responsively than fixed blinds. Manual blinds require human adjustment. Motorized blinds with preset schedules adjust on time, not light levels. The swarm system adjusted in near-real-time, responding to actual conditions. This could reduce energy consumption significantly, though the team hasn't published final energy calculations.

The second case study was more creative. During a public exhibition at Princeton's Lewis Center for the Arts in April 2024, the team deployed 36 SGbots and added interactive features. Visitors could gesture to make robots bloom and retract. The team added wearable devices with accelerometers. Visitors wearing these devices could perform movements, and the robots would respond with synchronized blooming patterns and LED color changes.

One of the researchers even performed a live dance while wearing a wearable device, with the robot array blooming and retracting in sync with arm movements. This demonstrated that swarm robotics isn't just environmental adaptation—it's also a medium for creative expression and human interaction.

The exhibition was crucial because it moved swarm robotics from the lab into public space. People could see the robots. They could interact with them. They could feel the responsiveness. This kind of experience is hard to convey in a paper or video.

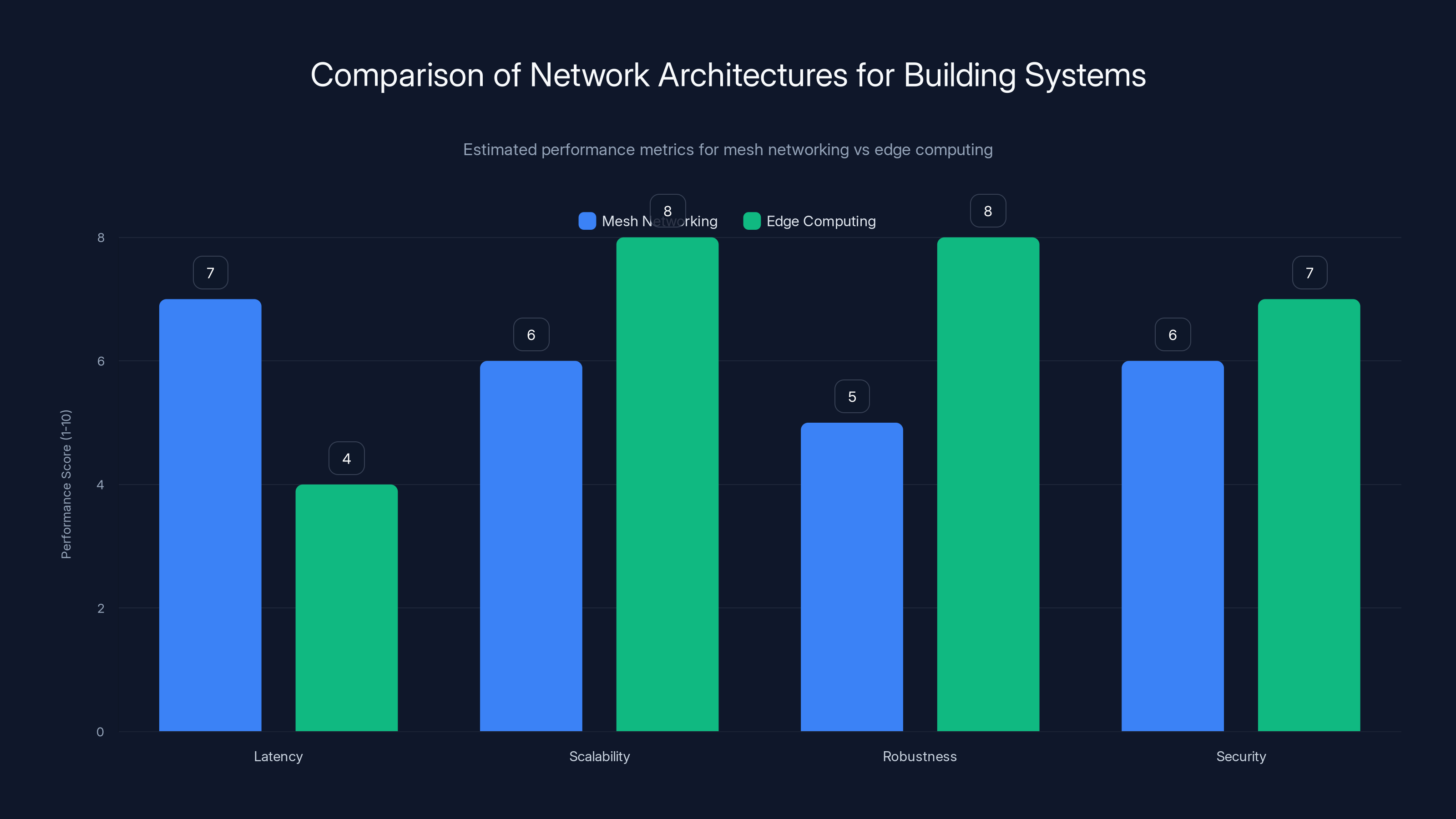

Edge computing generally offers lower latency and higher robustness compared to mesh networking, making it more suitable for large-scale distributed systems in buildings. Estimated data.

Environmental Sensing: How Robots Know What to Do

The core of the Swarm Garden is sensing. Without good sensors, robots are blind and can't make intelligent decisions.

Each SGbot has a light sensor on its back. This sensor measures ambient light intensity. It's a relatively simple sensor—it doesn't produce an image, it doesn't detect light color, it just measures brightness. But that's sufficient for this application.

Light sensors have a range of sensitivity. Too sensitive, and they respond to every flicker. Too insensitive, and they miss gradual changes. The Princeton team had to calibrate the sensor response to track natural daylight changes without oscillating constantly. If a robot blooms and unblocks light, the sensor detects increased brightness and retracts, which blocks light again, which makes it bloom... you get the idea. Feedback loops can cause oscillation.

The solution involves hysteresis. This is a fancy word for "don't switch immediately." Instead of blooming when light exceeds a threshold, the robot blooms when light exceeds threshold and stays bloomed until light drops below a lower threshold. This prevents rapid switching and creates stable behavior.

The proximity sensor is equally important. Modern proximity sensors use infrared or ultrasound to detect nearby objects. The SGbots can sense neighbors within roughly 30 centimeters. This is the "local neighborhood" mentioned in swarm robotics literature.

With proximity sensing, the robot knows: "Are there robots to my left and right? Above and below?" This information enables coordination. If a robot's neighbor is extended, it might extend to match. If a neighbor is retracting, it might follow suit. The result is waves of blooming and retracting that spread across the array.

The Wi-Fi network adds longer-range communication. Robots can share state information: "I'm blooming because I'm in bright light." "I'm retracting because I haven't sensed light for 30 seconds." This information spreads through the network, helping distant robots make informed decisions.

The combination of three layers—local light sensing, local proximity sensing, and network communication—creates a system that's robust and responsive. If one layer fails, the others continue functioning.

The Mechanics: Making Plastic Dance

Here's where physics meets engineering: how do you take a simple motor and a plastic sheet and create graceful blooming and retracting?

The actuators in the SGbots are powered by small electric motors. These motors have limited power—this is intentional. More powerful motors mean more weight, more battery consumption, and more noise. The team was designing for buildings, so quiet, efficient operation is essential.

The motor drives a mechanism that pulls or releases the plastic sheet. The sheet slides through a slot, extending forward when pulled, retracting when released. The motion is controlled, not jerky. The sheet moves at a pace that feels natural—not too fast, not too slow.

The interesting part is what happens to the sheet as it extends. Because the sheet is thin and flexible, it doesn't stay flat. It buckles. This buckling is determined by physics—specifically, by how the material deforms under stress. The team didn't have to program the buckling pattern. Physics handles it.

Buckled shapes are actually beautiful. They're organic, cellular. They look like origami or flower petals. This aesthetic quality is important for building integration. People want to see technology that looks intentional and beautiful, not like the robot malfunctioned.

But buckling creates stresses. The material has to flex repeatedly, millions of times. Plastic fatigues. Cracks develop. The original plastic sheets worked, but they weren't durable long-term.

This is one of the technical challenges the team identified for future work: finding materials that can buckle elegantly without fatiguing. Natural materials like bamboo or cellulose fibers might work better than plastic. Materials science is still advancing in this area.

Another mechanical consideration: alignment. If all robots are supposed to bloom simultaneously, they need to move at similar speeds. But motor speeds vary. Manufacturing tolerances mean no two motors are identical. The team had to implement software-level synchronization. Robots compare their extension rates and adjust. A robot moving faster than its neighbors slows down. A robot moving slower speeds up. This is another example of distributed control—no central system correcting individual robots, just local feedback keeping things synchronized.

Power consumption is another constraint. Each robot has a battery. Motors consume significant power. Motors running all day drain batteries. The team explored kirigami-inspired design—using strategic cuts in the plastic to reduce the force needed to deform it. Kirigami (Japanese paper cutting) uses cuts to enable complex folding from simple flat sheets. Applied to SGbot sheets, carefully placed cuts could make the material fold with less force, requiring smaller motors and lower power.

Here's a mechanical trade-off the team encountered: more robots mean more options for creative expression but also more power needed. A single robot extending a sheet uses maybe a watt of power. Forty robots blooming simultaneously might draw 40 watts just for actuators, plus power for sensors and communication. Over a full day, that's significant. Scale this to a building facade with thousands of robots, and you're talking about substantial power demand.

Solving this requires multiple approaches: more efficient actuators, better materials (kirigami), distributed scheduling (not all robots bloom simultaneously), and renewable energy integration (solar panels on the robots themselves, thermal harvesting from the building).

The team's paper acknowledges these challenges but positions them as solvable engineering problems, not fundamental obstacles.

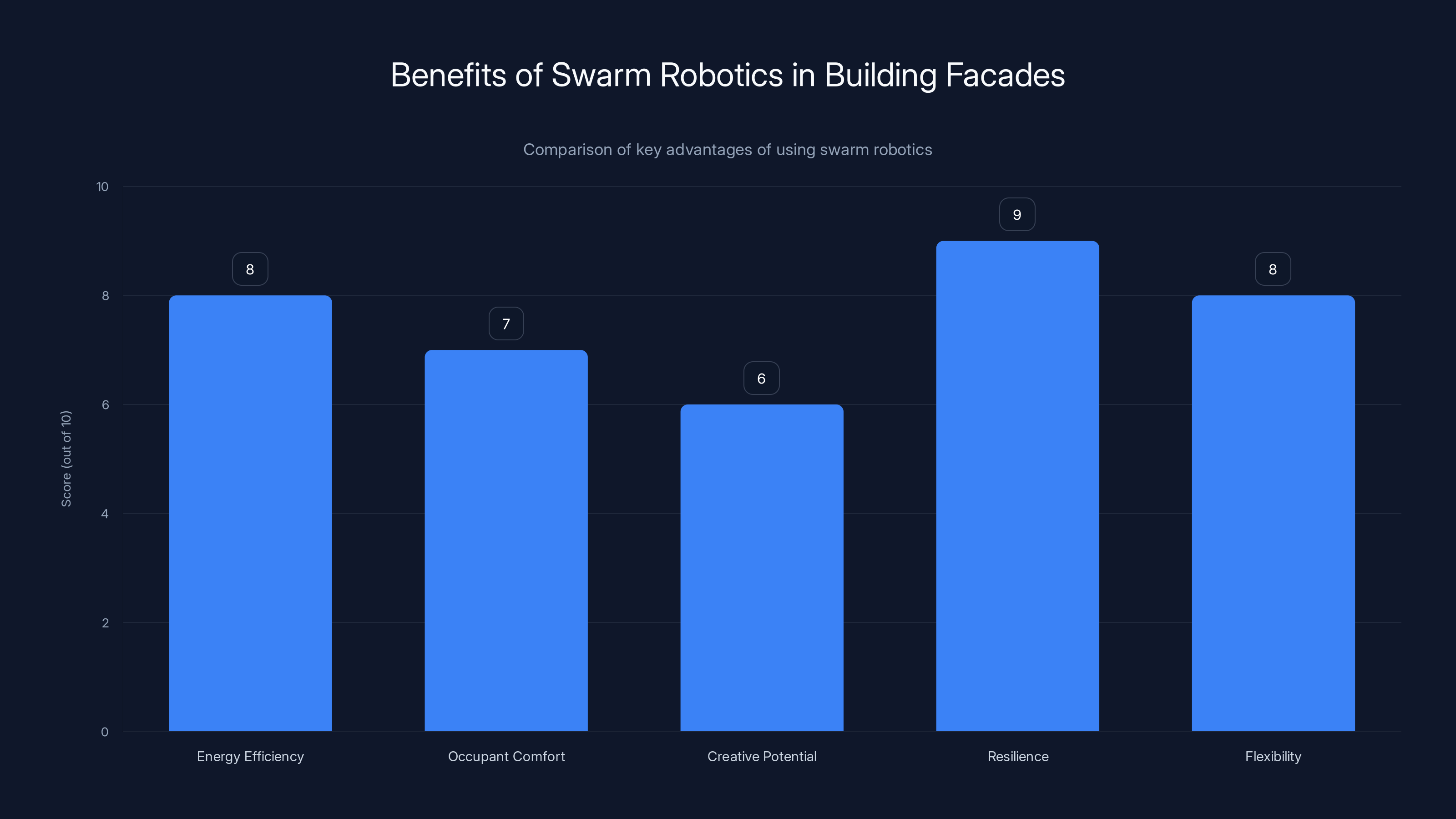

Swarm robotics in building facades offer significant benefits, particularly in resilience and energy efficiency, with scores of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data.

Collective Behavior Algorithms: The Brain of the Swarm

The real intelligence in swarm robotics lives in algorithms. Each robot runs software that interprets sensor data and decides what to do.

The algorithm is surprisingly simple. Here's a simplified version:

IF light_intensity > THRESHOLD_HIGH

THEN extend_sheet()

ELSE IF light_intensity < THRESHOLD_LOW

THEN retract_sheet()

ELSE

MAINTAIN_CURRENT_STATE()

FOR each neighbor_robot:

IF neighbor_is_extended

THEN increase_extension_probability()

ELSE

DECREASE_extension_probability()

This isn't complex mathematics. There's no machine learning. There's no artificial intelligence (despite what marketing might suggest). It's rule-based decision-making. But apply it across 40 robots with hysteresis, communication delays, and sensor noise, and you get behavior that's hard to predict without simulation.

The team uses agent-based modeling to understand how the algorithm behaves at scale. They simulate the swarm in software, testing different parameter values, seeing how behavior emerges. This lets them predict failures and optimize behavior before building physical robots.

One critical parameter: communication delay. Real-world networks have latency. Information doesn't spread instantly. A robot blooming at point A takes time to communicate that state to robots at point B. This delay affects synchronization. Too much delay, and robots oscillate. Too little, and you need expensive, low-latency networks.

The Princeton team had to calibrate delays to be realistic. They probably ran tests like: "What happens if one robot doesn't get a message?" or "What if the message arrives two seconds late?" These edge cases determine robustness.

Another algorithmic consideration: how far should influence spread? Should a robot consider only immediate neighbors, or should information from distant robots affect its decision? Close neighbors are more reliable and create local coherence. Distant robots provide global awareness. There's a trade-off.

The team likely implemented something like a "diffusion" algorithm—information spreads gradually from local neighborhoods outward, like ripples in a pond. A robot senses local light. Its neighbors sense this and adjust. Their neighbors see the adjustment and adjust further. Over time, information propagates through the network.

This is actually how real ants work, by the way. A foraging ant finds food and lays a pheromone trail. Nearby ants sense the pheromone and follow. They also reinforce the trail. The signal spreads gradually through the colony. Central processing? Zero. Emergent behavior? Sophisticated.

Deployment Scenario 1: Adaptive Shading in Office Spaces

Let's talk about practical application. The Princeton team tested adaptive shading in a real office window over three days. What did they learn?

Office buildings spend enormous energy on climate control. Heating, cooling, and lighting account for about 40% of building energy consumption in developed countries. Sunlight is a double-edged sword. In winter, you want solar heat gain—let sunlight warm the building. In summer, you want to block it—let sunlight overheat and you're fighting an uphill battle with air conditioning.

Traditional approaches:

-

Manual blinds: Occupants open and close blinds. Effective but inconsistent. People forget. People prefer privacy over efficiency.

-

Motorized blinds with schedules: Blinds adjust on a preset schedule. 8 AM, open. 6 PM, close. But the schedule doesn't account for clouds, weather, or actual sun position on any given day.

-

Automated blinds with light sensors: Blinds adjust based on light level. Better than schedules. But they're binary—open or closed. No gradations.

The Swarm Garden is different. Each robot independently senses light. When light is bright, it extends. When light is dim, it retracts. Across 16 robots covering a window, you get gradual, analog shading. Some robots extended, some retracted, creating a gradient.

This gradient is important. It blocks the harshest direct sunlight while allowing diffuse light through. It creates visual interest. And it enables more refined light control than binary on/off systems.

Over three days, the team measured interior light levels. The swarm maintained fairly consistent illumination despite changing sun angles. Morning brightness didn't flood the office. Afternoon dimness didn't require artificial lighting. The system self-regulated.

Energy implications are significant. If you can reduce HVAC demand through better solar control, you're saving energy. If you can reduce artificial lighting through better daylighting, you're saving more. The team hasn't published final numbers, but studies of conventional smart shading systems show 15–30% energy reduction for heating and cooling.

For the Swarm Garden, the energy calculation is more complex. You're adding robot systems, motors, sensors, and Wi-Fi infrastructure. That consumes power. You need to compare robot power consumption against energy savings from reduced HVAC and lighting. If the robots consume 100 watts but save 500 watts through better thermal and light management, you win. If robots consume 500 watts and save 100 watts, you lose.

The team's estimates (based on scaling) suggest the break-even point is reasonable. But this needs real-world validation. A building-scale deployment would generate data for actual energy calculations.

There's also human factors to consider. People in buildings with responsive architecture report higher satisfaction. A window that adjusts itself feels intelligent and responsive. Occupants feel the building is working for them, not against them. Studies on biophilic design—integrating natural elements into built environments—show improved mood, reduced stress, and higher productivity.

The Swarm Garden's blooming and retracting behavior has a biophilic quality. It mimics plant growth. It looks alive. Occupants notice. Some might find it distracting initially, but research suggests novelty wears off and people integrate it into their environmental awareness.

For commercial real estate, this is valuable. Buildings that reduce operating costs and improve occupant satisfaction command higher rents and attract better tenants. A 15–30% reduction in energy bills translates directly to NOI (net operating income) improvement. For a large office building, that could be millions of dollars annually.

This economic incentive is actually critical for real-world adoption. Technology that's only theoretically good doesn't get deployed. Technology that saves money and improves conditions gets deployed everywhere.

Each SGbot is equipped with essential components: light and proximity sensors, a Wi-Fi module, and an actuator, all contributing to its autonomous functionality.

Deployment Scenario 2: Creative Interior Design and Human Interaction

The second case study moved from functional shading to creative expression. Thirty-six robots at a public exhibition. Visitors could interact with them.

One mode used gesture recognition. Simple hand movements—waving, pointing, sweeping—triggered robot responses. A wave made robots bloom. A sweep made robots retract in sequence. Visitors quickly learned the interaction model and started experimenting with different gestures.

This is important because it bridges technology and human intuition. Visitors didn't need a manual. They didn't need instructions. They saw robots, made gestures, and things happened. The interaction felt natural.

Why does this matter for real buildings? Because it enables occupants to interact with the built environment in new ways. Imagine walking through a hallway where rooms bloom as you approach. Imagine a conference room where the walls respond to gestures during a presentation. Imagine a retail space where displays physically react to customer proximity and movement.

This creates a sense of agency. You're not just inhabiting a static building. You're in a responsive environment that acknowledges your presence. Psychologically, this is powerful.

The wearable device demonstration added another layer. Visitors wore accelerometer-equipped wristbands. Arm movements triggered synchronized robot patterns and LED color changes. The relationship between arm motion and robot response was clear and immediate. Visitors could choreograph the robots through movement.

One of the researchers performed a live dance with the robot array responding in real-time. This was crucial: it demonstrated that swarm systems can move beyond individual, discrete actions into continuous, coordinated performance.

Think about architectural implications. Dynamic facades in concert with music. Responsive interior walls that emphasize acoustics or visual focus. Partitions that reconfigure based on meeting dynamics. Buildings that aren't static containers but active participants in human activity.

This is harder to quantify economically than energy savings. How do you value employee satisfaction? Visitor experience? The intangible sense of being in a responsive, intelligent space? Some companies would pay premium prices for this. Others might see it as frivolous.

But consider hospitality, retail, or cultural venues. Hotels that feature interactive robotic architecture become attractions. Retail spaces with responsive displays attract visitors. Museums that integrate responsive technology create memorable experiences. These applications have clearer ROI.

Material Science Challenges: Beyond Plastic

Here's a problem the Princeton team identified but didn't fully solve: the plastic sheets fatigue.

Plastic deforms when stressed. If you deform it once, it recovers (mostly). If you deform it a million times, cracks develop. Material fatigue is well-understood for metals—engineers have stress-life curves that predict failure—but plastics are trickier. They're viscoelastic, meaning they have time-dependent behavior. Stress that's fine for short-term loading might cause failure with repeated cycling.

The SGbots extend and retract sheets thousands of times during deployment. Over months or years, the plastic fatigues and eventually fails. Replacement would be necessary. Frequent replacement isn't economically viable for large-scale deployment.

What alternatives exist?

Natural fibers: Cellulose, chitosan, or plant-based materials can offer better durability and biodegradability. But they have different mechanical properties. They might not buckle the same way. Material characterization would be needed.

Metals: Thin aluminum sheets could replace plastic. More durable. But heavier, requiring stronger actuators and more power. Also, metals don't have the aesthetic quality of the current system.

Smart materials: Shape memory alloys or electroactive polymers could deform on command without mechanical actuators. No motors needed. Lower power. But cost is currently prohibitive, and the technology is still being refined.

Composite materials: Layering different materials—plastic with reinforcement fibers, for instance—could improve durability while maintaining light weight. But manufacturing complexity increases.

Kirigami-inspired design: Strategic cuts in the material can concentrate deformation in controlled areas, reducing stress elsewhere. This extends material life. It's probably the most promising near-term solution.

The Princeton team suggested kirigami as a path forward. Instead of a continuous plastic sheet, you'd use a sheet with precisely designed cuts. These cuts allow the material to deform with less force and less total stress. Lower stress means longer material life.

Kirigami is an ancient art, but engineers have recently developed computational tools for designing optimal cut patterns. You specify the desired deformation, and algorithms calculate the cuts needed. The result is a sheet that seems to fold impossibly, despite being a single piece of material.

Applied to SGbots, kirigami could enable:

- Lower actuator power (smaller motors, less electrical demand)

- Longer material life (less stress concentration)

- More interesting aesthetic patterns (cuts create visual complexity)

The downside: manufacturing kirigami-designed sheets at scale is more complex than cutting simple rectangles of plastic. You need precision cutting equipment. You need quality control to ensure every sheet has cuts in the right places.

But this is solvable. Laser cutting can handle kirigami-level precision. Robotic fabrication can handle volume. It's not a fundamental barrier, just an engineering challenge.

Another material consideration: environmental impact. If SGbot sheets need replacement annually, you're generating plastic waste. For a building-scale deployment with thousands of robots, that's significant. Sustainable materials—biodegradable plastics, plant-based polymers, or fully recyclable metals—would be important.

The team's paper positions material science as an open research area. They've validated the concept. Material improvements are engineering optimization, not fundamental barriers.

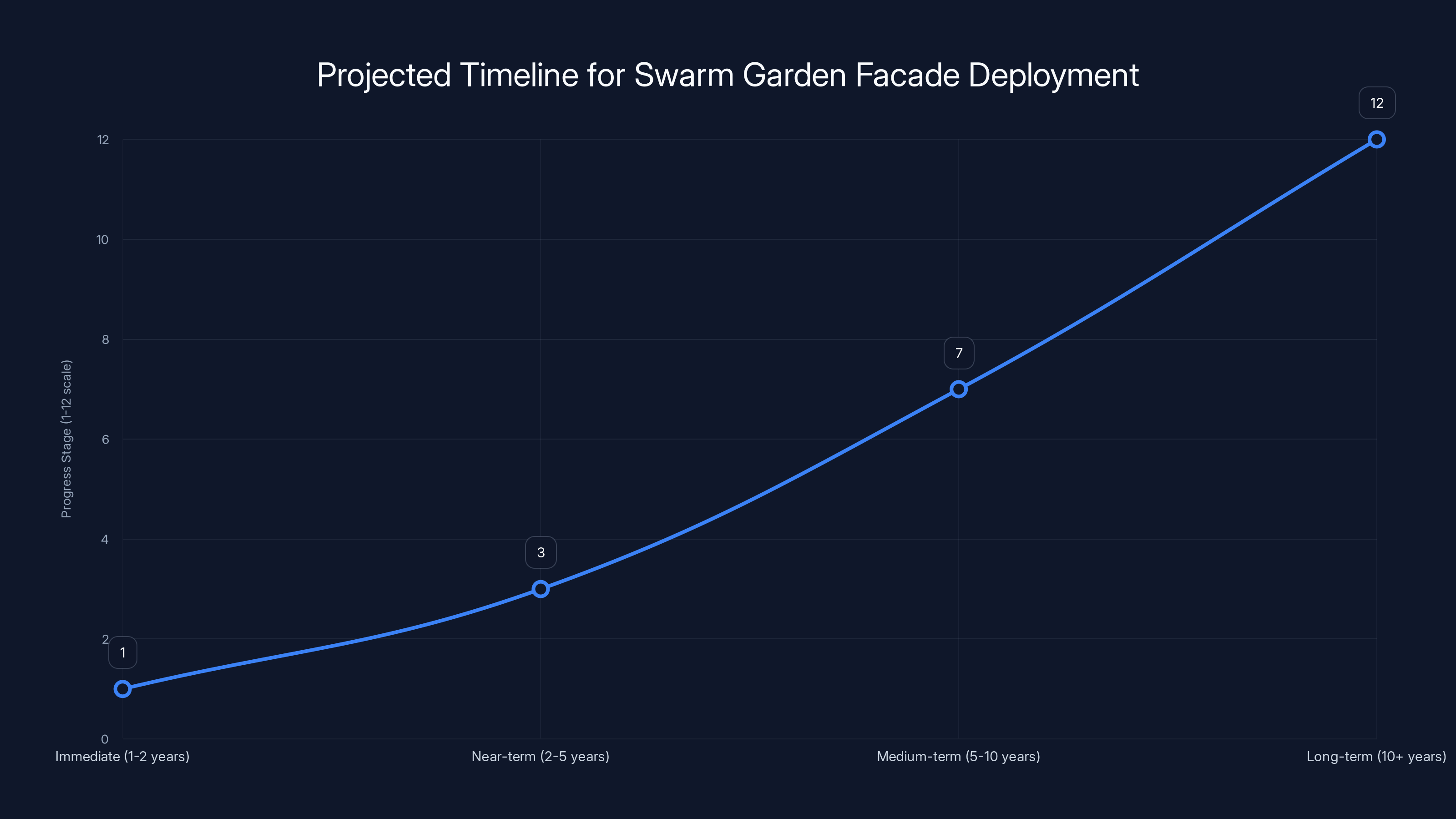

The timeline for deploying Swarm Garden facades is projected over several years, with significant progress expected in the medium to long term. Estimated data.

Power and Energy: The Economics of Actuation

Let's do some math. A single SGbot motor might consume 1–2 watts while extending a sheet. Forty robots operating simultaneously could draw 40–80 watts. Over 24 hours, that's roughly 1–2 kilowatt-hours per day.

In the US, average electricity costs about

Now compare to HVAC savings. A typical office building spends roughly

For a system costing maybe

But here's the catch: the cost estimates are rough. We don't know the actual manufacturing cost of an SGbot. We don't know the actual installation cost. We don't know the real energy savings in a variety of building types. These details matter for business case development.

For scaling to building-sized deployments, power distribution becomes critical. You can't run individual power cables to thousands of robots. You need power infrastructure—rails, busses, or wireless power transmission. These add cost and complexity.

Wireless power is interesting because it's rapidly improving. Microwave or infrared power transmission can charge robots over distance. No cables needed. But efficiency is currently 50–70%, meaning you lose significant power. Researchers are working on efficiency improvements.

Alternatively, each robot could have solar cells on top. In daylight, robots partially power themselves. In darkness or indoor deployments, they draw from wired infrastructure. This hybrid approach could reduce power demand by 20–40% depending on light availability.

For buildings with heavy use of artificial lighting (like warehouses or conference centers), solar doesn't help. You need wired power. For buildings with abundant natural light, solar could substantially reduce infrastructure costs.

Another power consideration: battery backup. If the building loses power, do the robots fail? For adaptive shading, loss of power isn't catastrophic—sheets just stay in their current position. But for buildings in areas with frequent outages, battery backup might be valuable.

This could be another role for kirigami-inspired design and material improvements. With lower actuation power, smaller batteries could provide meaningful backup capacity. A few hours of battery power might be sufficient to handle most outages.

The energy economics fundamentally favor swarm robotics in buildings. The operating cost is low. The energy savings potential is high. The primary barrier is upfront capital cost and proving real-world performance.

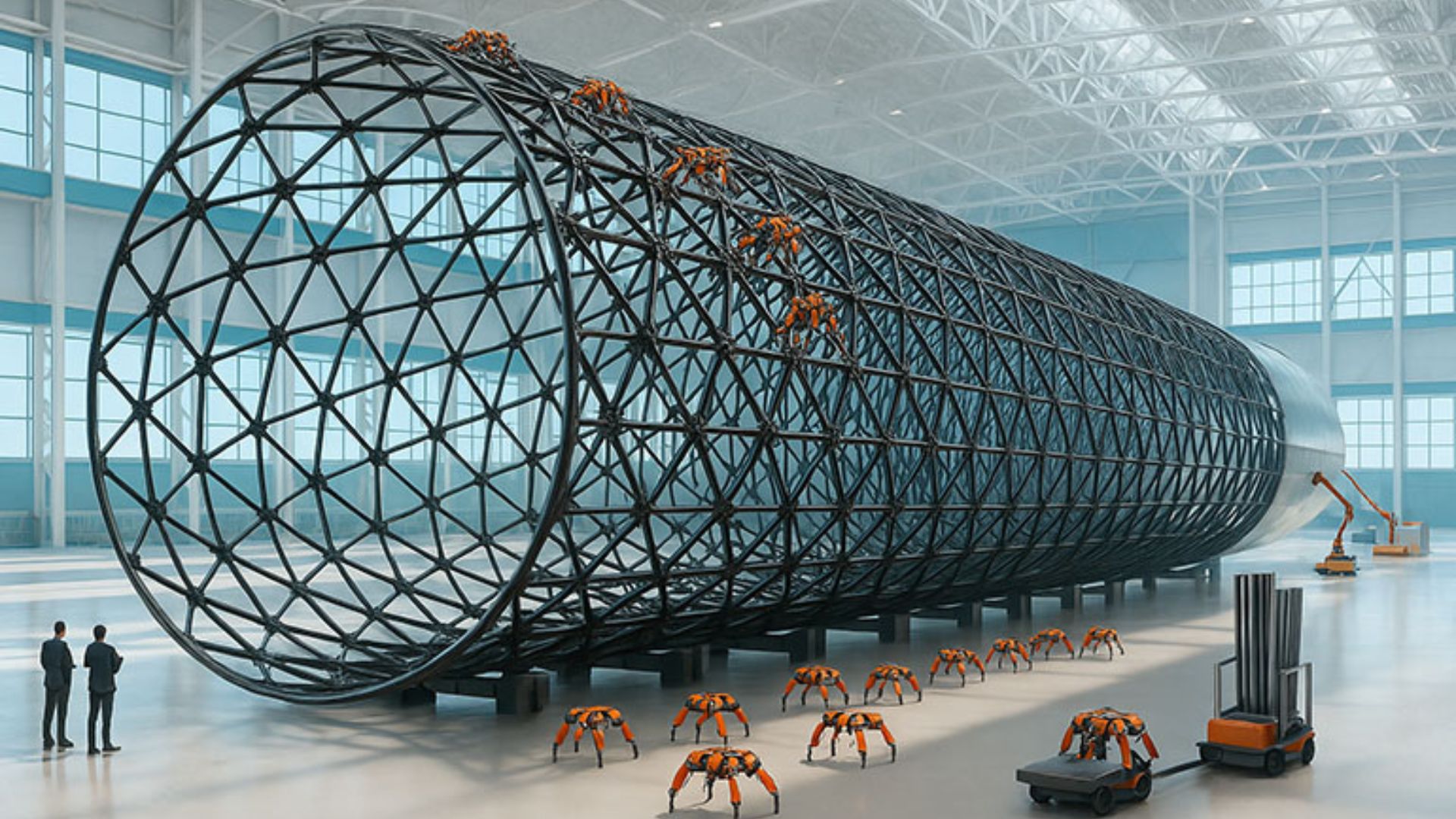

Scaling Challenges: From 40 to 4,000 Robots

The Princeton prototype uses 40 robots. A real building facade might use 4,000 or more. What changes when you scale up?

First, manufacturing. Forty robots can be built partially by hand. Forty thousand need factories. You need consistent quality, low defect rates, and economies of scale. Manufacturing processes matter.

Second, installation. Forty robots on a window take a day or two to install. Four thousand robots on a large building facade might require weeks. You need installation protocols, scaffolding, quality control checkpoints. It becomes a complex construction project.

Third, communication. Forty robots on a single Wi-Fi network—no problem. Four thousand robots need distributed network architecture. You probably need local Wi-Fi hubs, mesh networking, or some hybrid approach. Network latency and reliability become critical.

Fourth, power distribution. As discussed, forty robots at 50–80 watts is manageable. Four thousand robots at 5–8 kilowatts requires infrastructure planning. You need electrical engineering design, conduit routing, circuit protection, and probably power management systems that regulate load.

Fifth, redundancy. With forty robots, if one fails, the system continues with 39. With four thousand, failures are more frequent. You need to design systems where individual robot failures don't disrupt the whole facade. This might mean modularity—each section operates independently, with local decision-making that survives network partitions.

Sixth, maintenance. Forty robots can be serviced relatively easily. Four thousand robots need a maintenance strategy. Can you service individual robots without affecting others? Do you need predictive maintenance algorithms that anticipate failures?

Seventh, cost. Manufacturing cost per robot drops with scale due to economies of scale. But infrastructure costs—power, networking, installation—grow dramatically. There's probably an optimal sweet spot in terms of robot density and system design.

The Princeton team acknowledges these scaling challenges but frames them as engineering problems with known solutions. Other large-scale systems—data centers with millions of servers, cities with millions of devices—have solved analogous problems. The approach would be similar: modularity, distributed control, redundancy, and robust monitoring.

Network Architecture: Distributed Systems in Buildings

The Swarm Garden uses Wi-Fi for communication. Each robot connects to a local network. This works fine for 40 robots. For thousands, you need a more sophisticated architecture.

Mesh networking is one approach. Imagine Wi-Fi repeaters distributed throughout the building. Each robot connects to the nearest repeater. If a repeater fails, robots reroute through alternate paths. The network self-heals.

But mesh networks have limitations. Adding nodes increases latency. Every message might hop through multiple repeaters, introducing delay. For a swarm system where timing matters, latency can disrupt synchronization.

An alternative: edge computing. Instead of a central server, deploy small computers distributed throughout the building. Each computer manages robots in its local area. These local controllers communicate with each other. This distributes processing and reduces latency.

For example: the west facade has 800 robots managed by a local controller. The east facade has 800 robots managed by another local controller. The two controllers communicate periodically to share state information. Each controller handles real-time decisions for its robots.

This architecture is more robust. If the west controller fails, west facade robots still operate based on local sensors. They don't need central command to adjust to light changes.

Network security is another consideration. A building's control systems are increasingly targeted by hackers. If the swarm network is compromised, an attacker could make robots malfunction. They could open facades at the wrong time, expose the building interior, or simply create chaos.

Security measures would include:

- Authentication (only authorized controllers can issue commands)

- Encryption (communication is protected)

- Rate limiting (prevent floods of commands)

- Fallback modes (if security is compromised, robots default to safe behavior)

For a facade system, "safe behavior" might mean retracting all sheets to a closed position. Inconvenient, but the building remains secure and functional.

Bandwidth is another constraint. If 4,000 robots are continuously updating their state—"I'm at 60% extension, light level is 800 lux, I have 3 neighbors nearby"—that's significant data. Even with efficient encoding, you might have megabytes per minute of network traffic.

Wi-Fi typically offers 50–100 Mbps throughput. That's plenty for swarm networks operating at reasonable update frequencies. But you need to be thoughtful about how frequently robots update state. More frequent updates enable tighter coordination but consume more bandwidth.

The Princeton team would likely recommend a hybrid approach: robots primarily use local sensors and communicate with immediate neighbors. Periodically (maybe every 10–30 seconds), robots update a shared network state with the central system. This balances responsiveness (local control) with global awareness (network communication).

Environmental Integration: Building Biology

One of the original inspirations for the Swarm Garden was "living architecture"—the idea of integrating biological systems into buildings.

The Al Bahr Towers in Abu Dhabi, completed in 2012, feature motorized shading that responds to sun position. It's beautiful and functional. But it's rigid mechanical architecture. The system doesn't adapt beyond what was programmed.

Living architecture goes further. Imagine a building facade that actually grows. Algae panels that photosynthesize and generate energy. Moss walls that filter air. Fungal networks that decompose waste. Living systems are more efficient, more self-repairing, and more resilient than mechanical systems.

Swarm robotics doesn't replace living architecture—it complements it. Robotic modules could support biological growth. They could adjust conditions for optimal plant growth. They could even harvest energy from biomass.

For instance, imagine SGbots supporting climbing vines. As robots adjust position, the vines naturally grow to fill gaps. The result is a living, responsive facade. Biological growth handles part of the adaptation. Robots handle the rest.

The carbon impact would be positive. Plants absorb CO2. They provide insulation. They reduce urban heat island effect. Combined with energy savings from smart shading, the building becomes a net carbon sink.

This is speculative, but it's the direction the Princeton team is pointing. Not pure robotics, not pure biology, but integrated biotech-robotics systems.

Other living architecture concepts:

- Mycelial networks (fungal filaments) for structural integrity

- Bacterial cellulose for organic material

- Algae bioreactors for carbon sequestration and energy generation

- Engineered microbes that produce pigments or structural proteins

Swarm robotics enables precise control over conditions for these biological systems. Temperature, humidity, nutrient delivery—all could be adjusted by robot positioning.

For long-term sustainability, biointegrated architecture is more promising than pure robotics. Living systems self-repair, reproduce, and adapt. They improve over time as they interact with the environment. Pure robotics is static—robots age, fail, and need replacement.

The best approach probably combines both. Robots provide the initial responsive structure and conditions. Biological systems integrate and enhance. Over years, the building becomes increasingly alive and self-sufficient.

Timeline to Real-World Deployment

When will actual buildings have Swarm Garden facades? The honest answer: unclear.

The Princeton team is being realistic. They've proven the concept works. They've demonstrated it at a public exhibition. But there's a long road from proof-of-concept to widespread building integration.

Immediate next steps (next 1–2 years):

- Material science work on kirigami-inspired designs

- Energy measurements from controlled installations

- Cost analysis and manufacturing optimization

- Collaboration with architects to understand integration challenges

Near-term (2–5 years):

- Prototype deployment in actual buildings

- Real-world performance data collection

- Cost reduction through manufacturing scale-up

- Development of standards and installation protocols

Medium-term (5–10 years):

- Adoption by some forward-thinking building designers

- Integration with smart building systems

- Refinement based on real-world feedback

- Development of secondary applications (retail displays, exhibitions, creative installations)

Long-term (10+ years):

- Widespread adoption in new construction

- Retrofit applications in existing buildings

- Integration with biological systems

- Emergence of autonomous building systems that adapt without human intervention

This timeline is optimistic. Other technologies have moved faster (solar panels, LED lighting). Others have moved slower (hydrogen energy, fusion power). For swarm robotics, there are no fundamental barriers, just engineering challenges and economic questions.

The biggest unknown is cost. If swarm robotics costs 10x more than conventional shading, adoption will be slow. If it costs comparable or less, it could proliferate rapidly.

Another unknown is maintenance. If swarm systems require frequent servicing, long-term adoption will suffer. If they're reliable and low-maintenance, adoption accelerates.

These unknowns can only be resolved through real-world deployment. The technology is ready. The business case is promising. What's needed now is investment and experimentation.

Broader Implications: Beyond Architecture

The Swarm Garden is a proof-of-concept for swarm robotics in the built environment. But the implications extend far beyond building facades.

Disaster response: Swarm robots can search collapsed buildings, detect survivors, and deliver supplies. They're resilient—if one robot fails, others continue. No central command necessary. Useful in earthquakes, floods, or other disasters where infrastructure is damaged.

Mining and excavation: Robotic swarms can dig underground cooperatively, as the Georgia Tech experiment demonstrated. No jamming, efficient material removal, and safer than human workers in hazardous conditions.

Agriculture: Swarms of micro-robots could monitor crop health, apply targeted pesticides or nutrients, and even perform pollination tasks. Precision agriculture at scale.

Urban planning: Swarm robotics could inform how cities are designed. Understanding how systems self-organize at scale provides insights for traffic flow, crowd management, and urban design.

Even medicine: Nanorobotic swarms could target cancer cells, deliver medication, and perform minimally invasive surgery. Still theoretical, but the principles are the same.

The common theme: swarms are resilient, adaptive, and efficient. They solve problems that would be difficult with single large robots or centralized control. As technology advances and costs decrease, we'll see swarms applied to more and more domains.

The Swarm Garden is an early example of this broader trend. It's architecture, but it's also a demonstration of swarm principles. Success here opens doors for other applications.

FAQ

What is a swarm robot, and how is it different from a traditional robot?

A swarm robot is a relatively simple autonomous unit designed to work cooperatively with many other similar units. Unlike traditional robots, which are often expensive, complex systems that operate independently or under centralized control, swarm robots are simpler, cheaper, and designed from the ground up for collective behavior. They follow local rules based on nearby sensors and neighbor communication, creating emergent intelligent behavior without central command. This approach is more flexible and resilient—if individual robots fail, the swarm adapts and continues functioning.

How does the Swarm Garden actually sense light and adjust its behavior?

Each SGbot has a light sensor on its back that measures ambient light intensity. When light exceeds a threshold, the robot extends its plastic sheet. When light drops, it retracts. The robot uses hysteresis (different thresholds for extending vs. retracting) to prevent oscillation. Additionally, proximity sensors help robots detect neighbors, and Wi-Fi communication enables robots to share state information. By combining these three layers of sensing, the swarm can respond both to immediate environmental conditions and to the behavior of neighboring robots, creating coordinated adaptation across the entire array.

What are the main benefits of using swarm robotics in building facades?

Swarm robotics enables dynamic, adaptive building facades that provide multiple benefits: (1) Energy efficiency through responsive shading that reduces HVAC and lighting loads by 15–30%, (2) Improved occupant comfort through better light and thermal control, (3) Creative potential—facades can respond to human movement and gestures, creating interactive experiences, (4) Resilience—if individual robots fail, the system continues functioning, (5) Flexibility—the same hardware can be reprogrammed for different behaviors. Compared to static architecture or basic motorized blinds, swarm systems offer intelligence and adaptability without requiring complex central control.

What are the technical challenges preventing widespread deployment of Swarm Gardens?

Several challenges remain: (1) Material durability—plastic sheets fatigue after repeated buckling and need replacement, (2) Power consumption—scaling to thousands of robots requires substantial electrical infrastructure, (3) Manufacturing cost—current prototypes are expensive; volume manufacturing would reduce this but requires investment, (4) Network complexity—coordinating thousands of robots requires sophisticated distributed networking and edge computing, (5) Integration with existing buildings—retrofitting swarm systems into older buildings is complex, and new buildings need design modifications. None of these are fundamental barriers, but they require engineering solutions before widespread deployment.

How does the Swarm Garden handle failure of individual robots?

The system is designed for graceful degradation. If one robot fails, its neighbors detect the failure through missing communication or unchanged sensor readings. Remaining robots adjust their behavior and continue functioning. The gap left by a failed robot might create asymmetry in the facade, but overall system performance continues. For critical applications, you'd want some redundancy—perhaps 10–15% extra robots for replacement. For less critical applications, accepting occasional failures might be acceptable. The distributed architecture means there's no single point of failure that would shut down the entire system.

What does "kirigami-inspired design" mean, and why is it important for Swarm Gardens?

Kirigami is a Japanese art form that uses strategic cuts and folds to transform flat material into complex three-dimensional shapes. Applied to SGbot sheets, kirigami-inspired cuts would reduce the force needed to deform the material, requiring smaller, lower-power motors. This has multiple benefits: lower energy consumption, extended material life (less stress), more interesting aesthetic patterns, and potentially faster response times. The challenge is that manufacturing kirigami-designed sheets requires precision cutting equipment, but this is solvable through laser or robotic fabrication. Kirigami represents a near-term path to improving the fundamental design.

Could Swarm Gardens be powered by renewable energy like solar?

Yes, and it's probably part of the long-term solution. Each robot could have small solar cells on top, providing partial power during daylight hours. For indoor applications or buildings in areas with limited sunlight, solar alone isn't sufficient. But a hybrid approach—solar power supplemented by wired infrastructure—could reduce overall electrical demand by 20–40%. For buildings with high natural light availability, solar-powered swarms could be largely self-sufficient. Additionally, thermal harvesting (using temperature differences) and kinetic harvesting (capturing energy from robot movement) are emerging technologies that could further reduce external power needs.

How would a building integrate thousands of Swarm Garden robots?

Integration would likely be modular. The building would be divided into zones, each with its own local controller and set of robots. Local controllers would handle real-time decision-making for their zone, while a central building management system coordinates across zones. Power distribution would use rails or busses rather than individual cables. Communication would use mesh networking with local hubs. Installation would be phased—perhaps different facades completed over time. The robots would integrate with other building systems: HVAC would receive setpoint recommendations from the shading system, lighting would adjust based on available daylight, and so on. It would be complex, but similar to how other large building systems (electrical, plumbing, HVAC) are integrated.

What's the timeline for seeing Swarm Gardens in real buildings?

Early prototypes in real buildings could appear within 2–5 years, likely in forward-thinking projects or research institutions. Wider adoption might take 5–10 years. Several factors affect timeline: cost reduction through manufacturing scale-up, demonstrated energy savings from real-world deployments, development of standards and installation protocols, and accumulation of sufficient real-world performance data to convince architects and building owners. There are no fundamental barriers, just engineering and economic questions. If costs drop and performance is proven, adoption could accelerate. If costs remain high or failures occur, adoption will be slower.

Could Swarm Gardens eventually replace all building shading systems?

Possibly, but probably not immediately. Swarm Gardens excel at responsive, dynamic shading. For buildings that need flexibility and control, they're superior. But for buildings with stable, predictable conditions—a warehouse with minimal occupancy changes, for instance—conventional fixed shading might be sufficient and cheaper. Cost-benefit analysis matters. Also, Swarm Gardens work best on new construction where designers can plan for them. Retrofitting into existing buildings is more complex. Over time, as costs decline and performance improves, swarm systems could become the default for building facades. But it will likely be a gradual transition, with conventional systems and swarm systems coexisting for decades.

How does swarm robotics apply to other domains beyond architecture?

Swarm principles are useful wherever you need distributed, resilient systems: disaster response (robots searching collapsed structures), mining (cooperative excavation), agriculture (precision application of inputs), space exploration (satellite swarms), and medicine (potential nanorobotic applications). Any application where central control is impractical or where resilience is critical benefits from swarm approaches. The Swarm Garden demonstrates that swarm robotics isn't just theoretical—it works in practical applications. Success here could accelerate adoption in other domains.

Final Thoughts: The Future of Responsive Architecture

The Swarm Garden represents more than just a clever engineering project. It's a philosophical shift in how we think about buildings.

For centuries, architecture has been about static structures. You design a building, build it, and it stays that way for decades. You adapt to the building. The building doesn't adapt to you.

Modern buildings are slightly more flexible. Motorized systems can adjust blinds or HVAC setpoints. But these are add-ons, not integrated into the fundamental design. The core is still static.

Swarm robotics enables something different: buildings that are fundamentally responsive. Not just smart in terms of control systems, but intelligent in terms of adaptation. A building that learns how you use it. That adjusts proactively. That collaborates with you rather than serving you.

This requires a mindset shift from architects and engineers. It requires investment from building owners. It requires standardization and scale from manufacturers. But the underlying technology works. The Princeton team proved it.

When you watch the video of 36 robots blooming in response to hand gestures—that's the moment it clicks. That's when you realize: this isn't just a shading system. It's the beginning of buildings that are alive.

Not alive in a biological sense (though future biointegrated versions might be). But alive in terms of responsiveness, adaptation, and interaction. Buildings that see you. That react to you. That make spaces more comfortable and more beautiful through intelligence rather than control.

The economics make sense. The engineering works. The applications are clear. What's needed now is investment and scale. A few pioneering buildings. Real-world performance data. Cost reduction through manufacturing improvements.

Given the scale of the construction industry, even small percentage adoption would mean thousands of buildings with swarm facades. Millions of robots. Exajoules of energy saved. Experiences enhanced. Cities transformed.

The Swarm Garden isn't the future. It's the present. The question is how quickly it scales. And that depends on the next steps: collaborations with architects, real-world deployments, and a commitment from the industry to try something different.

The robots are ready. The question is whether we are.

Key Takeaways

- Swarm robotics enables buildings to adapt dynamically to environmental conditions through simple local rules and neighbor communication without central control

- The Princeton Swarm Garden demonstrates 15–30% potential energy savings through responsive shading while improving occupant comfort and enabling creative interaction

- Scaling from 40 to 4,000+ robots requires engineering advances in materials (kirigami design), power distribution, network architecture, and manufacturing cost reduction

- Kirigami-inspired cuts can reduce actuator power by 20–40% while extending material durability—a near-term optimization path for real-world deployment

- Real-world building integration depends on architect collaboration, cost-competitive manufacturing, proven performance data, and integration with existing building management systems

Related Articles

- Best Winter Tech for 2026: Must-Have Gear to Beat the Cold [2026]

- AI Data Centers & Carbon Emissions: Why Policy Matters Now [2025]

- Ocean Robots in Category 5 Hurricanes: Oshen's Breakthrough [2025]

- X Outage Recovery: What Happened & Why Social Platforms Fail [2025]

- X Platform Outages: What Happened and Why It Matters [2025]

- Honeywell Home X2S Smart Thermostat Review [2025]

![Robot Swarms That Bloom: The Future of Adaptive Architecture [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/robot-swarms-that-bloom-the-future-of-adaptive-architecture-/image-1-1769026142641.jpg)