Microsoft's Unexpected Network Mishap: The Example.com Routing Anomaly

Something deeply weird happened inside Microsoft's infrastructure, and it went largely unnoticed for years. The company's internal network was routing traffic destined for example.com—a domain explicitly reserved by international standards for testing purposes only—to servers belonging to a Japanese electronics manufacturer. Not just any manufacturer, but Sumitomo Electric, a major industrial equipment maker based in Osaka.

Here's the thing: This wasn't malicious. It wasn't even intentional. But it represented a significant operational failure that exposed test credentials, created a security gray zone, and raised uncomfortable questions about what other misconfigurations might be lurking inside one of the world's largest software companies' network infrastructure.

The discovery came through routine testing. When security researchers queried Microsoft's autodiscover service—the system that automatically configures email clients like Outlook—with fictional test accounts using the example.com domain, something unexpected happened. Instead of failing gracefully or returning a standard error, the service provided detailed configuration instructions. But those instructions weren't pointing users toward legitimate Microsoft servers. They were redirecting email traffic to Sumitomo Electric's subdomains: imapgms.jnet.sei.co.jp and smtpgms.jnet.sei.co.jp.

This is where security gets messy. Nobody's suggesting that Sumitomo Electric did anything wrong or that they were aware test credentials were being routed to their servers. The problem wasn't malice. It was negligence multiplied by years of system complexity, automation, and the kind of configuration debt that accumulates when large organizations grow faster than their infrastructure oversight processes.

The implications deserved serious attention. Test accounts using example.com should never, under any circumstances, generate legitimate routing information. They should fail. They should return errors. They should disappear into the void. That's literally the purpose of reserved domains under international standards. But instead, Microsoft's system was treating them as real accounts deserving of complete email configuration.

Understanding Reserved Domains and Why They Matter

Before diving into what went wrong, you need to understand what example.com actually is and why it exists.

RFC 2606, published by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), established three domains specifically for testing, documentation, and educational purposes: example.com, example.net, and example.org. These aren't arbitrary choices. The IETF designation means these domains are guaranteed never to be registered to anyone. They're permanent placeholders in the internet's namespace, set aside deliberately so developers, penetration testers, security researchers, and documentation writers could use them without risk.

The logic is straightforward but crucial. When you're testing an email client, building sample applications, or demonstrating a concept, you don't want to accidentally send real traffic to a production server. You don't want your demonstration code to contact real people or real systems. Reserved domains solve this problem entirely. You can confidently use example.com in your tests knowing that even if configuration breaks down, no legitimate organization owns that domain and no traffic will actually route anywhere unexpected.

But that guarantee only holds if systems treat these domains specially. Once organizations start registering reserved domains in their internal DNS systems, configuring routing rules for them, or including them in authentication flows, the protection collapses. The domain remains reserved in the global internet's namespace, but inside your network, it becomes a live configuration point. That's where Microsoft's misconfiguration created vulnerability.

Think of reserved domains as safety zones. They're like ghost addresses used in fire drills. Everyone knows they're fake. The moment you start routing real mail to them, you've broken the fire drill protocol. Now actual fire equipment arrives at addresses that don't exist, or worse, arrives at the wrong place entirely.

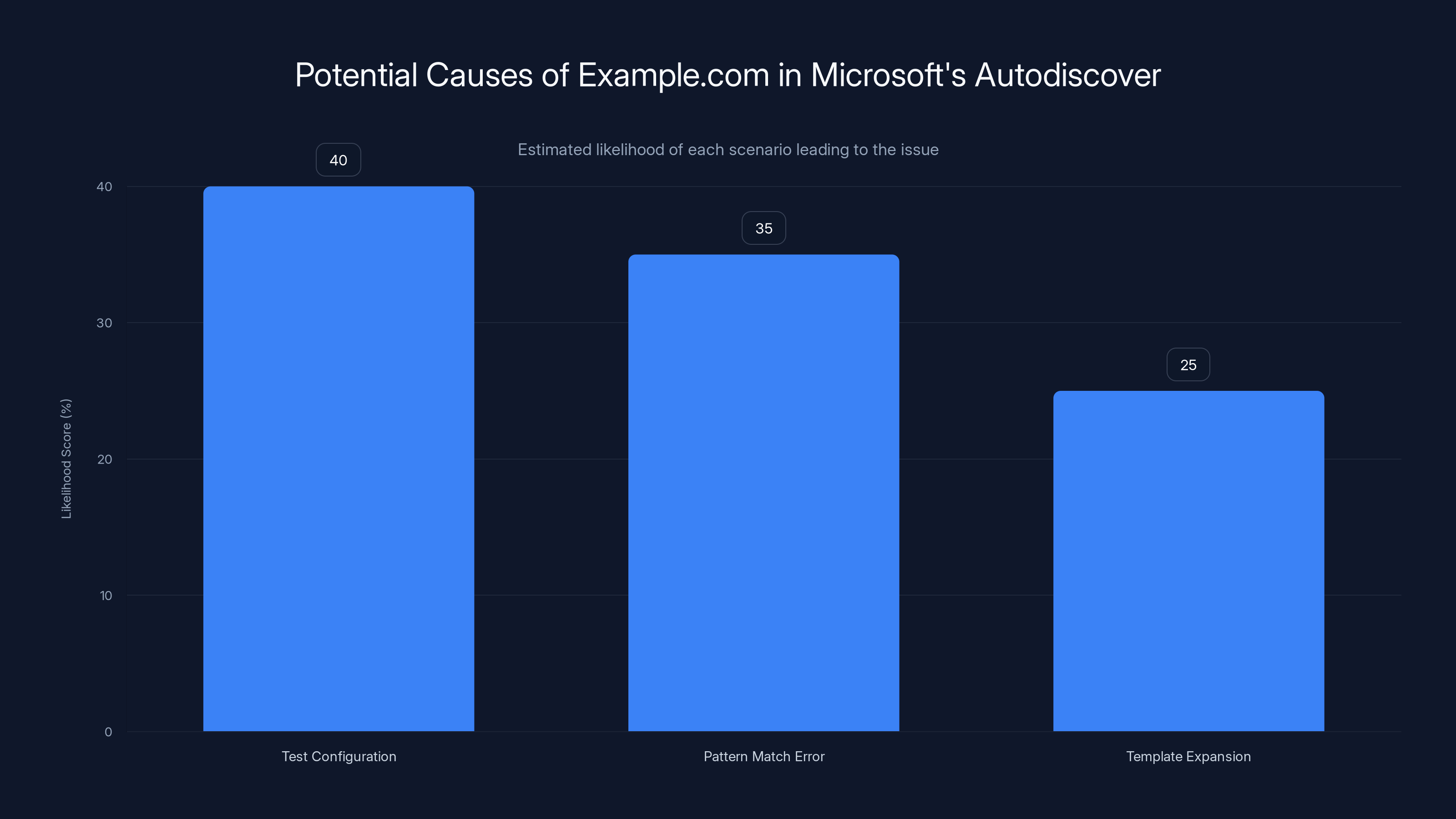

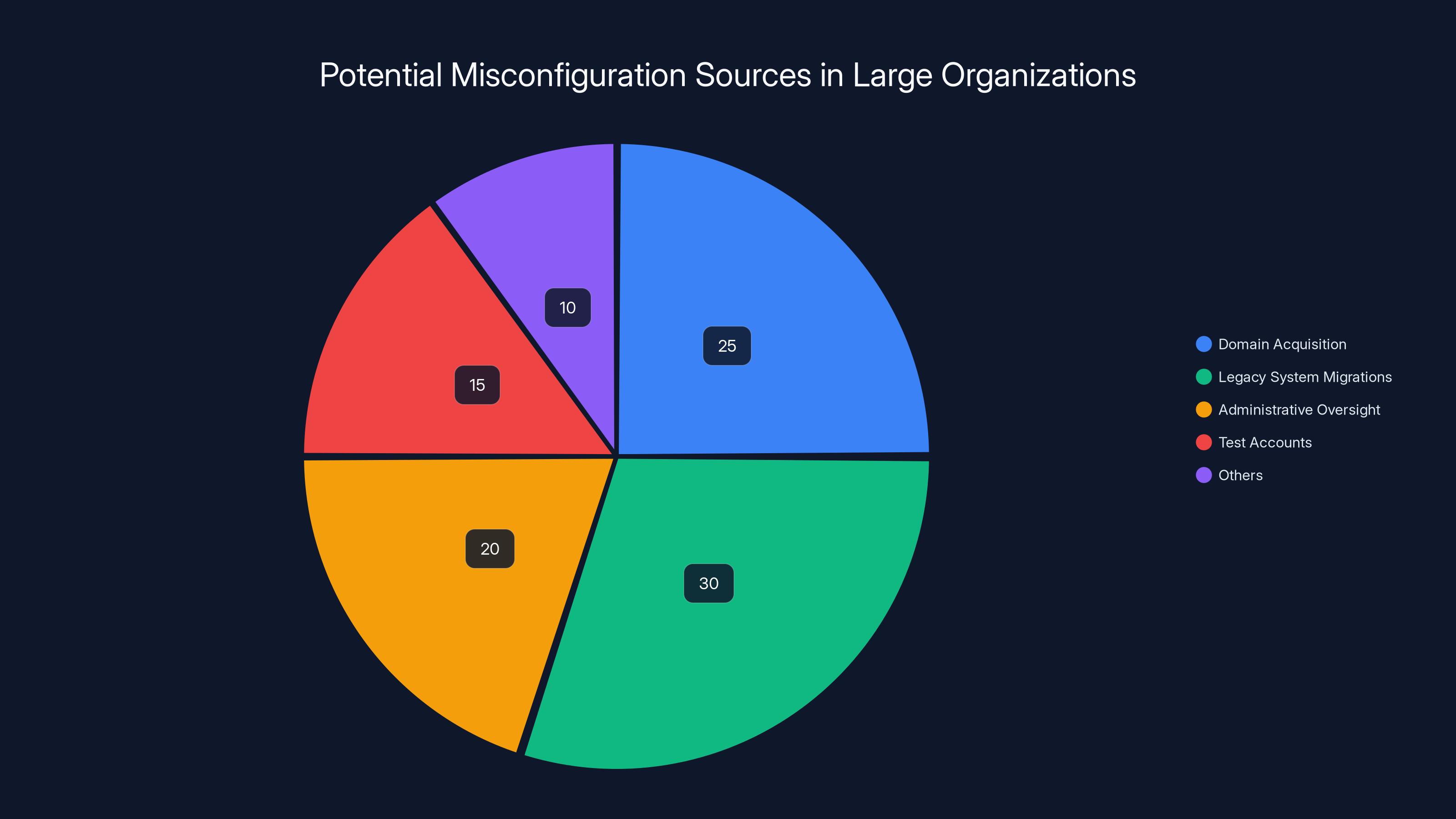

Estimated data suggests test configuration errors are the most likely cause of the issue, followed by pattern match errors and template expansion problems.

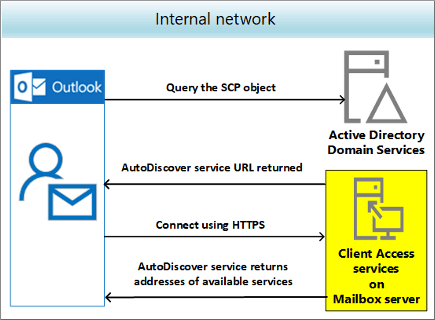

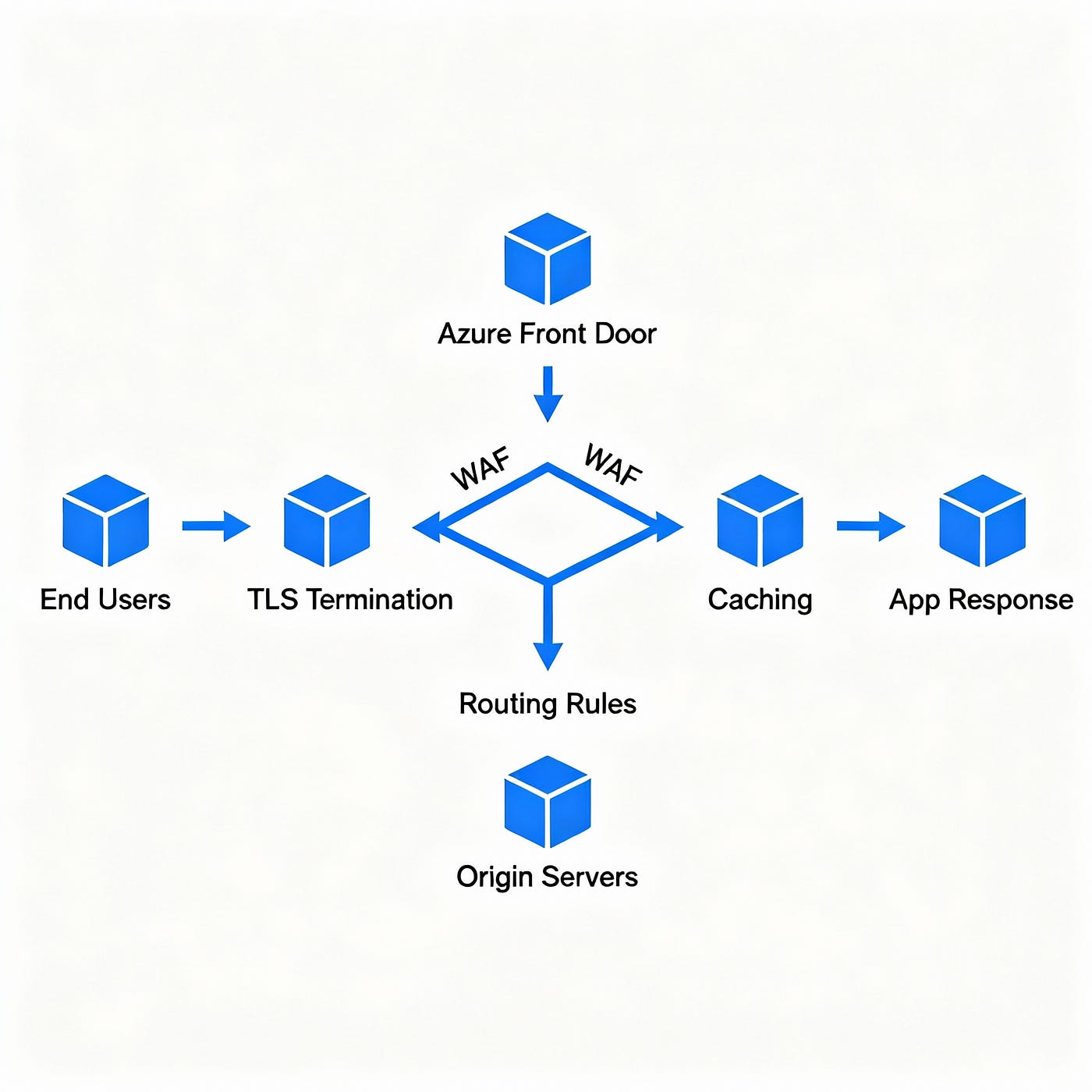

How Microsoft's Autodiscover Service Works

Microsoft's autodiscover infrastructure is designed to simplify one of the most frustrating parts of email setup. When you first add an email account to Outlook or another email client, the client needs to know several pieces of information: which server handles incoming mail (IMAP or POP3), which server handles outgoing mail (SMTP), what ports to use, what encryption protocol is required, and what authentication method to employ. Getting all these details wrong means your email doesn't work. Getting some of them wrong means it partially works—maybe you can receive but not send, or maybe it works on Wi-Fi but fails on cellular.

Historically, users had to know all these technical specifications or call their IT department. Autodiscover changed that. When you enter your email address and password, the client reaches out to autodiscover endpoints operated by your email provider. These endpoints look up your domain and return a configuration file (usually in XML format) containing everything the client needs to properly configure itself.

For Microsoft, this system runs across a global infrastructure of servers coordinating with internal databases that map domains to configuration rules. It's a legitimate optimization that improves user experience significantly. But like all automation systems at scale, it requires meticulous configuration management.

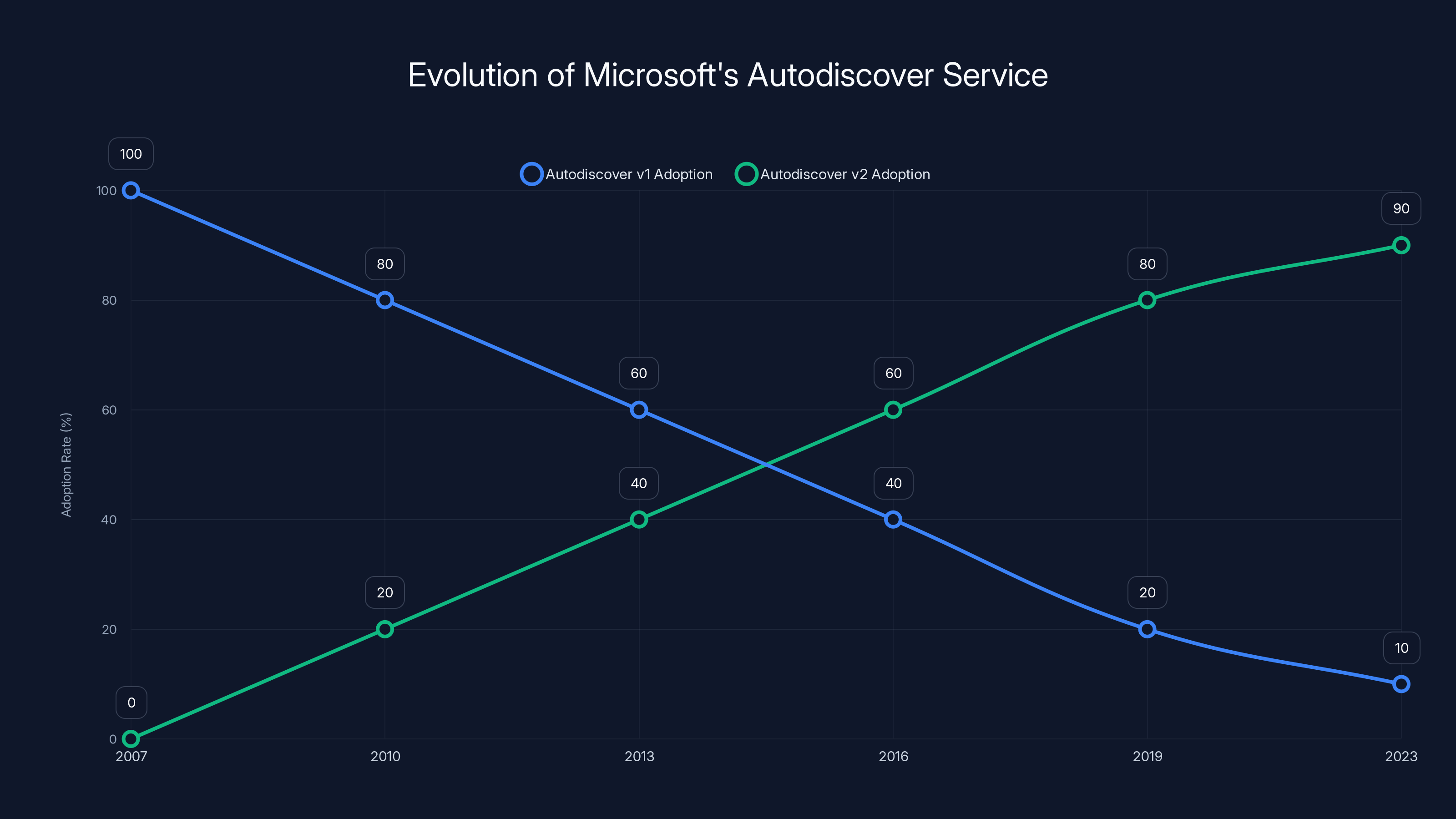

Microsoft's autodiscover service has evolved considerably over the years. The company offers both older protocols and newer versions. When a client makes an autodiscover request, the service goes through a decision tree. It first tries newer methods (autodiscover v2), then falls back to older approaches (autodiscover v1), then checks fixed databases, then checks provider-specific databases, then checks domain-specific configurations. Each of these layers is a potential configuration point where misconfiguration can creep in.

Here's the critical part: None of these layers should return configuration information for reserved domains. A proper autodiscover system should recognize example.com and immediately return an error or reject the request. Instead, somewhere in this layered decision tree, a configuration entry existed that associated example.com with routing information pointing to Sumitomo Electric's servers.

The Detection: How the Misconfiguration Was Discovered

Microsoft didn't announce this problem. Researchers found it through systematic testing. The methodology was straightforward but revealing: query the autodiscover endpoint with various test domains and observe what comes back.

When researchers sent autodiscover requests for example.com accounts, they received JSON-formatted responses instead of errors. That's immediately suspicious. Reserved domains shouldn't trigger valid responses. But the responses weren't just odd—they contained detailed configuration information. The JSON included IMAP server addresses, SMTP server addresses, port numbers, encryption types, and username fields. All pointing to Sumitomo Electric's infrastructure.

A sample response looked like this:

json{

"email": "email@example.com",

"services": [],

"protocols": [

{

"protocol": "imap",

"hostname": "imapgms.jnet.sei.co.jp",

"port": 993,

"encryption": "ssl",

"username": "email@example.com",

"validated": false

},

{

"protocol": "smtp",

"hostname": "smtpgms.jnet.sei.co.jp",

"port": 465,

"encryption": "ssl",

"username": "email@example.com",

"validated": false

}

]

}

This is the smoking gun. This response tells an email client exactly how to route traffic. The hostname fields explicitly point to external domains. The port numbers (993 for IMAP, 465 for SMTP) are standard encryption ports. The validation field even shows "false," which is honest—these servers wouldn't actually validate test credentials because they're expecting real Sumitomo Electric employees' mail, not Microsoft test traffic.

What's particularly concerning is that if someone were actually using these details to configure an email client, they would attempt to authenticate with test credentials against a foreign server. The credentials wouldn't authenticate (obviously), but the attempt would travel across the internet to Japan, logged on Sumitomo Electric's servers, for a domain that should never route anywhere.

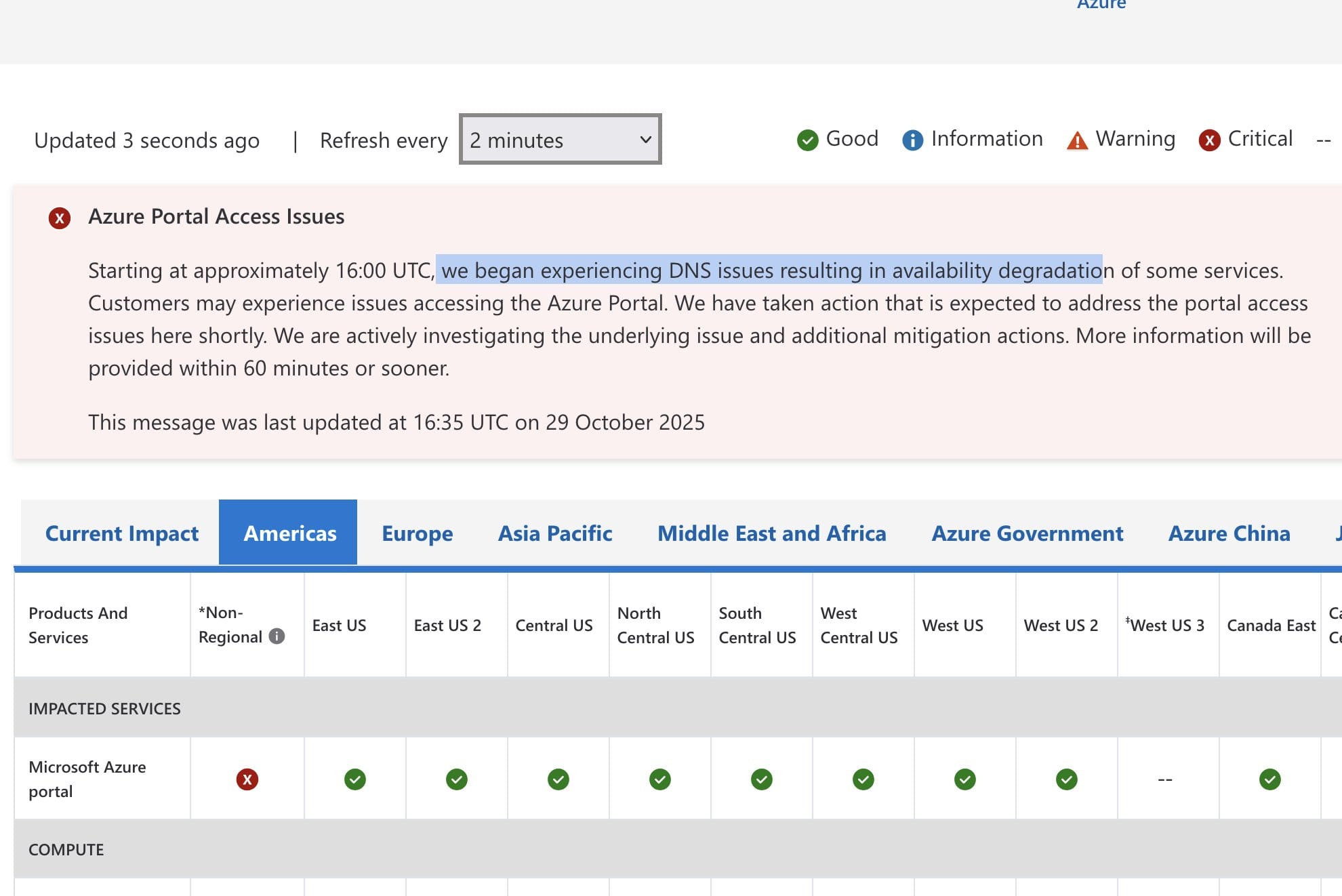

When reporters at Ars Technica approached Microsoft with these findings on a Friday afternoon, the company initially had no explanation. By Monday morning, something had changed. The misconfiguration was no longer returning detailed JSON responses. Instead, queries simply timed out with a 204 response code and an ENOTFOUND error.

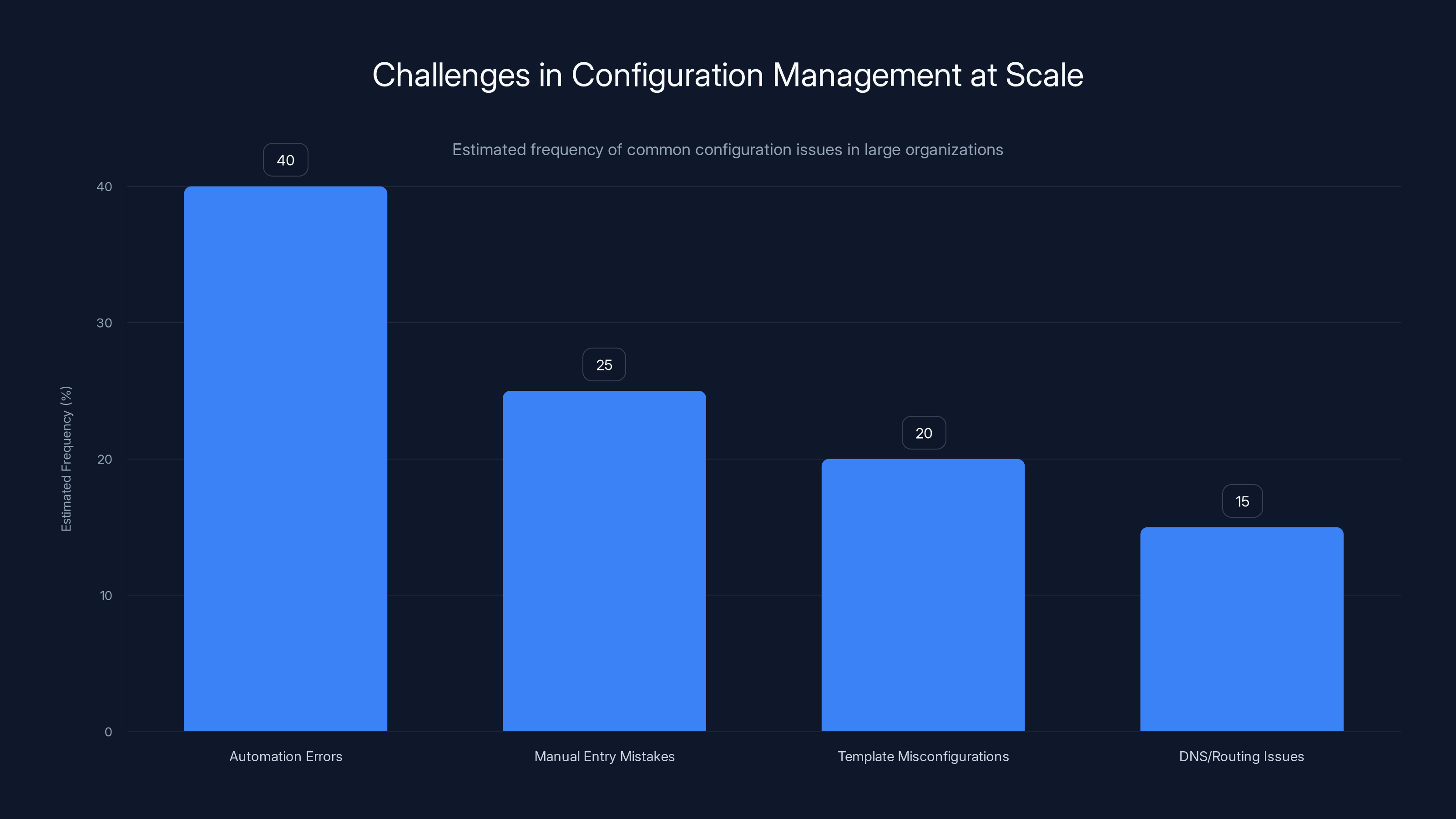

Automation errors are the most common issue in configuration management at scale, followed by manual entry mistakes and template misconfigurations. Estimated data.

The Root Cause: Configuration Management at Scale

Microsoft never publicly detailed exactly how example.com ended up in their autodiscover configuration. But from the available evidence, the most likely explanation involves how large organizations manage their internal DNS and routing systems.

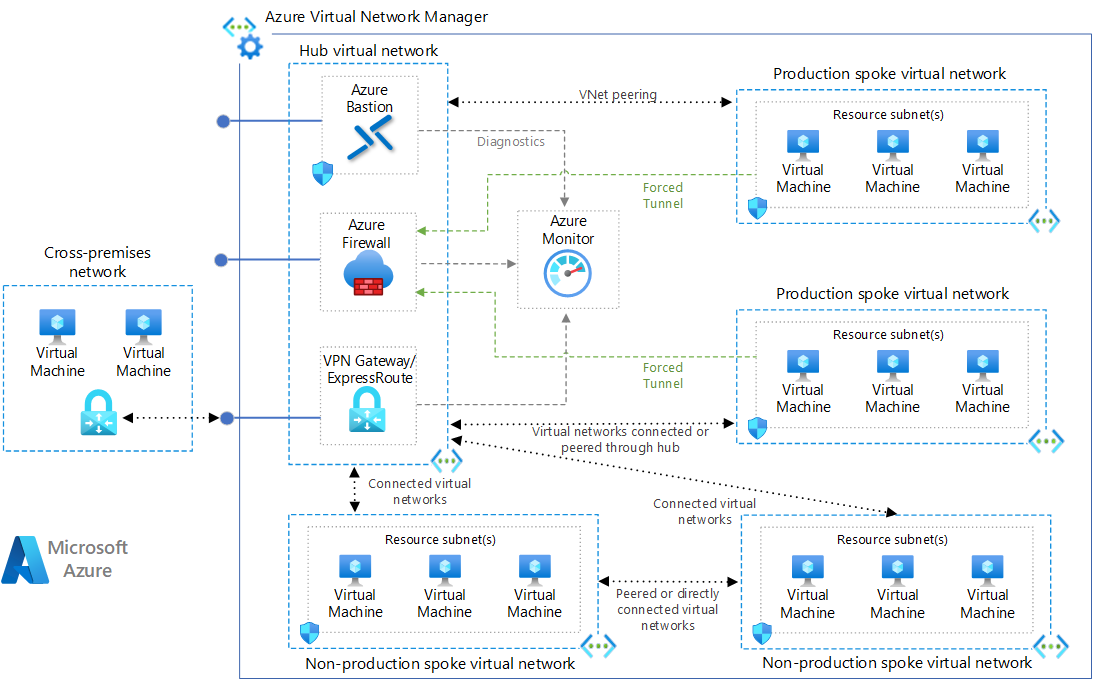

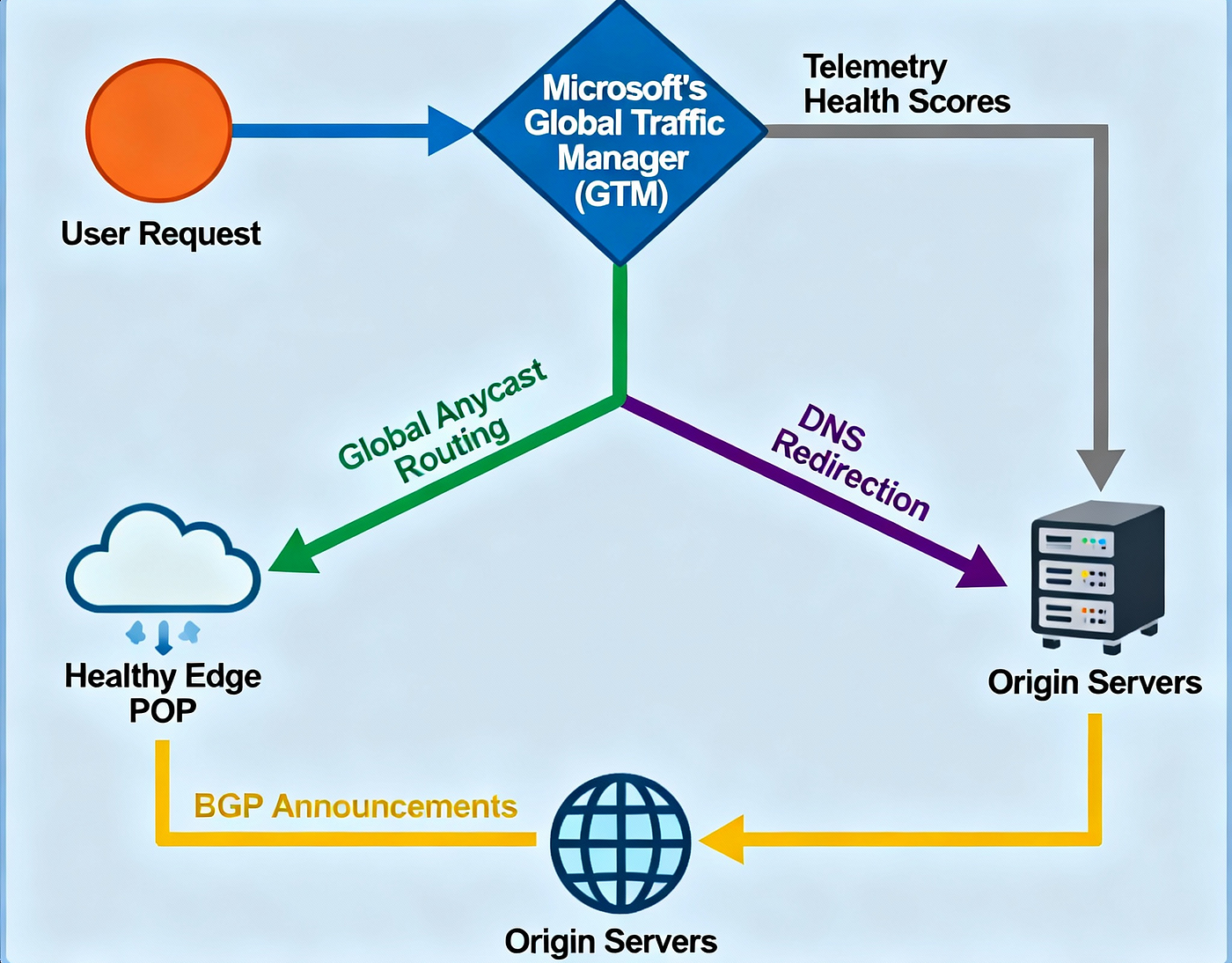

Microsoft's infrastructure operates at extraordinary scale. The company maintains thousands of servers, processes billions of email messages daily, and manages configurations across dozens of products and services. In environments like this, configuration management becomes incredibly complex. Organizations typically use automation to manage configurations because manual management would be impossible at scale.

One likely scenario: A database entry for sei.co.jp (Sumitomo Electric's domain) existed in Microsoft's system, probably legitimately created when the company began deploying Microsoft 365 to Sumitomo Electric or its subsidiaries. During some automated configuration update, domain matching logic went wrong. Instead of applying the sei.co.jp configuration only to actual sei.co.jp addresses, the automation wildcard-matched or pattern-matched in a way that accidentally included example.com.

Another possibility: Someone manually added example.com to a configuration database for testing purposes and forgot to remove it. This happens in large organizations more often than it should. Configuration entries accumulate over years, and the original reason for their existence becomes lost to time.

A third scenario involves template expansion or variable substitution errors. If autodiscover configurations use template systems where variables get replaced, a misconfigured template could cause generic domain matchers to apply to reserved domains they shouldn't touch.

The core issue isn't Microsoft-specific. It's a fundamental challenge of infrastructure automation: the more rules and exceptions you create, the higher the probability that those rules eventually conflict or misconfigure in unexpected ways. Security researchers call this "configuration complexity debt." Every new exception, every new domain mapping, every new routing rule increases the chance that future configuration changes will create unintended interactions.

Microsoft's senior leadership actually confirmed a related problem in 2024. The company revealed that a test account had been granted administrative privileges and then forgotten for months. This account sat dormant until Russian state-sponsored hackers discovered it and used it to gain initial access to Microsoft's network. They subsequently spent two months monitoring executive emails before detection. That incident demonstrates the same underlying problem: configuration sprawl, inadequate tracking of special-case entries, and insufficient automated auditing of who has what permissions.

When you look at both incidents together—the test account with admin privileges that nobody remembered, and the example.com domain routing to Japan—a pattern emerges. Microsoft's configuration management has become too complex to audit manually, automation isn't catching edge cases, and the company lacks sufficient automated systems to detect when test resources escape their intended boundaries.

The Security Implications: What Could Have Gone Wrong

Here's the critical question: How dangerous was this misconfiguration really?

On the surface, the risk seems limited. Nobody had actually created a real example.com account. The only credentials being sent would be test credentials. And Sumitomo Electric's servers, receiving authentication attempts for users that don't exist, would simply reject them.

But this analysis misses several important threat vectors.

First, test credentials sometimes aren't entirely fictional. Developers often use placeholder credentials that are variations on real credentials. A developer might use "testadmin@example.com" with password "Test Password 123" during development. If that developer reuses patterns between test and production—which happens frequently despite being bad practice—the test credentials could reveal information about the pattern used for real credentials.

Second, the mere fact that Microsoft was routing to external servers meant external servers could observe that routing. Sumitomo Electric's IT team might eventually notice unexpected authentication attempts from Microsoft's network. A sophisticated attacker could potentially intercept that traffic or modify responses, though this becomes harder with modern encryption.

Third, this misconfiguration proved that Microsoft's autodiscover system could be tricked into revealing routing information for domains it shouldn't service. If example.com could be hijacked in the configuration, so could other test domains, or potentially even legitimate domains through similar misconfiguration patterns.

Fourth, consider the attack surface this creates for insider threats. An employee of Sumitomo Electric who gained access to the email systems receiving this misdirected traffic could observe authentication attempts from Microsoft employees and systems. They'd see usernames, email addresses, and potentially other metadata that could be useful for social engineering or further attacks against Microsoft.

Fifth, from a compliance perspective, this created a problem. Many regulated industries require that test data never leave your organization. If you're a healthcare company using Microsoft 365, and your test credentials are being routed to external servers (even legitimately external servers), you might be in violation of regulatory requirements around data handling.

Security researcher Michael Taggart from UCLA Health told reporters that the configuration meant "anyone who tries to set up an Outlook account on an example.com domain might accidentally send test credentials to those sei.co.jp subdomains." That phrasing is important: "accidentally send." This wasn't about unauthorized access to credentials. It was about credentials being sent to a destination they absolutely should not reach, even if those credentials are nominally test-only.

How Microsoft "Fixed" It: The Incomplete Solution

When Microsoft responded, they didn't announce what happened or explain how it happened. They just made the problem stop appearing.

The behavior changed between Friday and Monday morning. Queries that previously returned detailed JSON configuration information now returned 204 No Content responses followed by timeout errors. The ENOTFOUND error indicated that the endpoint wasn't finding the configuration anymore.

But here's where this gets interesting: The error response suggests Microsoft didn't fix the root cause. They just disabled the endpoint. Instead of correcting the misconfiguration, they appear to have removed the entire code path or database lookup that was returning example.com entries.

This is a common triage response in incident management. When you need to stop a problem immediately and don't have time to diagnose root cause, you disable whatever system is misbehaving. It's emergency medicine, not a cure. It stops the bleeding but doesn't heal the wound.

The technical response headers revealed what happened: The endpoint returned an x-debug-support header containing encoded diagnostic information. Decoded, it showed the autodiscover system's decision tree. The later response indicated that the entire validation chain had returned null—meaning the configuration lookup system had been disabled or blocked for example.com queries.

Microsoft never publicly confirmed this, but the behavior strongly suggests they:

- Identified which database or configuration file contained the erroneous sei.co.jp entries

- Added an emergency block or exception to prevent those entries from being returned

- Did not remove or correct the underlying misconfiguration

This means the bad configuration likely still exists in Microsoft's systems. It's just been blocked from being used. If the emergency block is ever removed or modified, the old behavior could return.

A proper fix would involve:

- Finding every instance of example.com in Microsoft's configuration databases

- Removing all of them

- Auditing the configuration management process to understand how they got there

- Implementing automated checks to prevent reserved domains from being added to routing configurations

- Running full regression tests to ensure no other reserved domains are misconfigured

- Reviewing all sei.co.jp entries to verify they're intentional and correct

- Implementing ongoing monitoring to catch similar issues early

There's no evidence Microsoft did any of this. They just made the problem stop appearing.

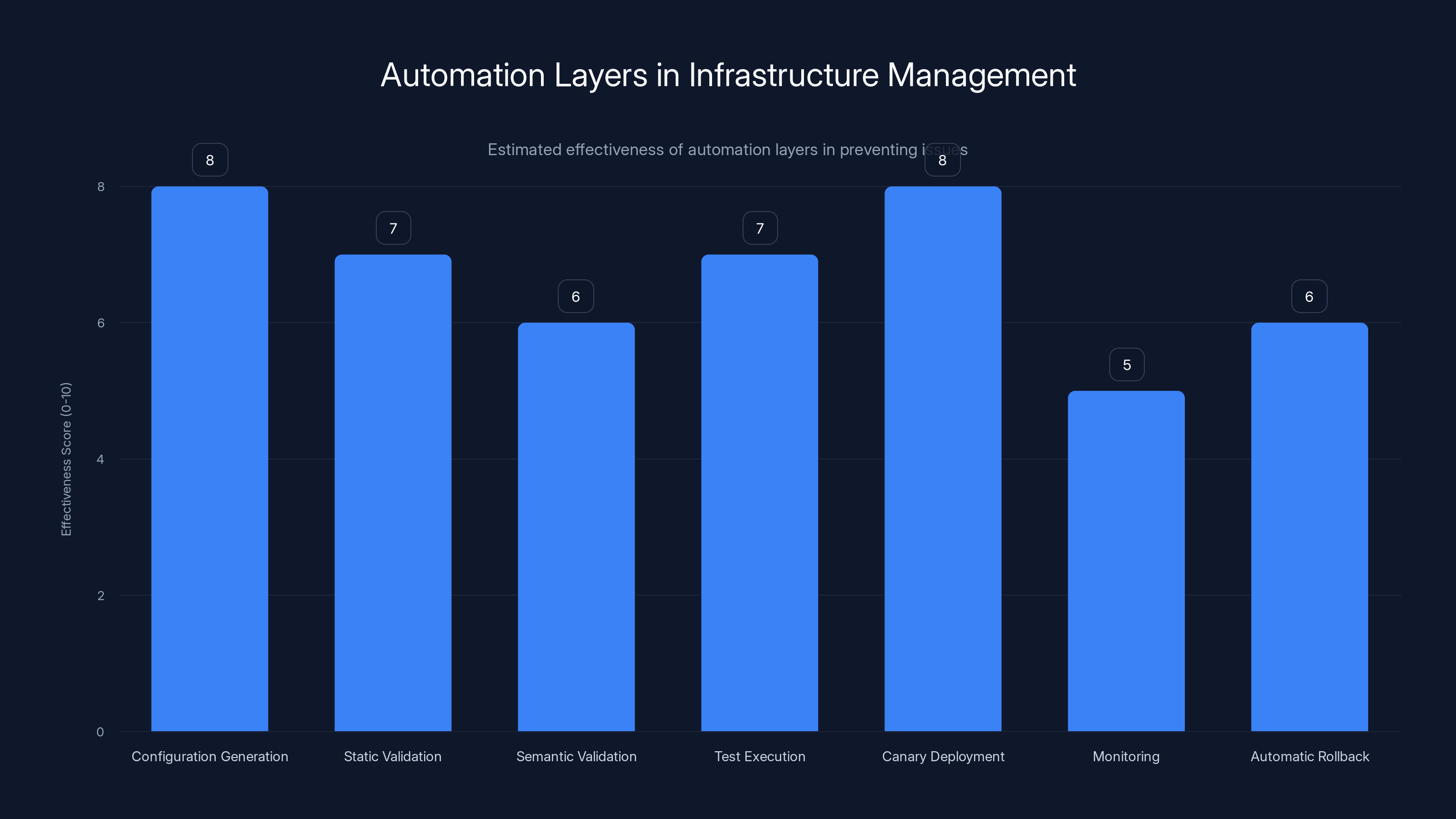

Monitoring is identified as the weakest link in the automation chain, with a lower effectiveness score, suggesting it may have contributed to prolonged misconfigurations. Estimated data based on typical infrastructure automation processes.

The Broader Concern: What Other Misconfigurations Exist?

Here's what keeps security researchers up at night: If example.com was misconfigured, what else is?

Microsoft's infrastructure is large enough that it contains dozens or hundreds of similar edge cases. The company manages email for millions of businesses. It operates cloud infrastructure serving billions of users. Configuration complexity at that scale means there are almost certainly other misconfigurations lurking in various systems.

The 2024 incident involving a test account with administrative privileges proved this point dramatically. Someone created that account for legitimate testing purposes, granted it full administrative access—reasonable in a test environment—and then forgot about it. The account sat dormant for months until Russian hackers discovered it and used it to access Microsoft's production network. They maintained access for two months, monitoring executive email, before being detected.

That incident cost Microsoft credibility, required explaining to customers that their infrastructure had been compromised, and led to significant internal restructuring. The company increased scrutiny on administrative access, improved audit logging, and made public statements about improving security practices.

But that incident also demonstrated a fundamental truth: Even with that heightened scrutiny and public commitment, the example.com misconfiguration still existed and went undetected for years. If they can miss an obviously wrong configuration (test domain routing to external servers), they might miss other configurations that aren't quite so obvious.

Consider what happens in large organizations:

-

Domain acquisition and integration: When Microsoft acquires companies, they integrate those companies' infrastructure. New domain entries get added to various systems. Years later, divisions get reorganized or divested. Domain entries don't always get cleaned up.

-

Legacy system migrations: When services migrate from one infrastructure to another, temporary configurations sometimes become permanent. A routing rule meant to be temporary during a migration might stay in place for years.

-

Partner integrations: When Microsoft works with partners (like Sumitomo Electric), they create various integration points. If those integrations aren't properly isolated from test systems, they create contamination risk.

-

Automated configuration updates: The more automation you use to manage configurations, the more automated mistakes can propagate. A single error in configuration generation can create thousands of erroneous entries across the network.

-

Configuration sprawl: Over decades, organizations accumulate thousands of configuration rules, exceptions, and special cases. Tracking all of them becomes impossible without sophisticated tooling.

Microsoft isn't alone in this problem. Every major technology company faces similar challenges. AWS, Google Cloud, IBM, and others have all experienced incidents where configurations went wrong in unexpected ways. The difference is usually in detection and remediation speed.

Sumitomo Electric's Role: Probably Innocent

One question people asked: How did Sumitomo Electric's domain end up in Microsoft's configuration?

Sumitomo Electric is a massive industrial manufacturer. They're probably not hackers or malicious actors. They most likely didn't intentionally inject their domains into Microsoft's autodiscover system. The connection is almost certainly legitimate.

Microsoft previously announced that Sumitomo Electric's parent company, Sumitomo Corp., was implementing Microsoft 365 Copilot. That means integration work, potentially involving various subdomains and email system modifications. It's entirely plausible that during this integration work, configuration entries for Sumitomo Electric's subdomains were created in Microsoft's systems.

The real question is: Why did those entries cross contaminate with test domain configurations? Why wasn't there proper isolation between production integrations and test systems?

Sumitomo Electric probably never knew their servers were receiving misdirected traffic from Microsoft's autodiscover service. Their IT team might have noticed unusual authentication attempts in their email logs, but they likely attributed them to the normal integration work Microsoft was doing.

This points to another broader problem: When large organizations integrate with each other, configuration isolation becomes critical. The two organizations need firm boundaries that prevent test configurations from one company affecting production systems of another, and vice versa. Microsoft's autodiscover system apparently lacked these boundaries.

Industry Standards and Why They Matter

The reason RFC 2606 exists is that the internet community learned hard lessons about what happens when you don't have reserved space for testing.

Before RFC 2606, developers and testers used whatever domains they wanted for testing. Some used random made-up domains. Some used placeholder domains they thought nobody would ever register. Some used competitor domains because they seemed obviously unavailable. The result was chaos.

Someone would set up test infrastructure using "walmart.com" as a placeholder domain (assuming Walmart would never let that domain resolve to their test servers). But then their test configuration would leak into production. Or a developer's test data would accidentally touch real walmart.com users. Or Walmart's infrastructure would be confused by unexpected configuration directives.

Other developers used domains that actually existed but seemed obscure. Those obscure domains sometimes became popular, got registered legitimately, and suddenly received traffic from thousands of test systems around the internet. The legitimate owner would be confused and angry.

RFC 2606 solved this by saying: Here are three domains nobody will ever own or operate. Use these for all your testing. The IETF guarantees they'll never be allocated to anyone. This creates a permanent safe zone for test traffic.

The protocol is elegant because it's mandatory. Because the domains are reserved globally, you can use them confidently in any context. Your test email won't accidentally reach real people. Your test API calls won't accidentally modify production data. Your test configuration won't accidentally route to live systems. Everyone can safely assume that example.com is a safe testing ground.

But that elegance only works if systems respect the reservation. The moment Microsoft started treating example.com as a routeable domain requiring configuration, they broke the contract that RFC 2606 established.

The chart illustrates the shift from Autodiscover v1 to v2 over time, with v2 becoming the dominant protocol by 2023. Estimated data based on typical adoption trends.

Lessons for Infrastructure Teams

If you run infrastructure—whether you work for a cloud provider, a large enterprise, or even a mid-sized tech company—this incident offers several critical lessons.

First: Automate your configuration audits. You cannot manually review thousands of configuration entries. You need automated systems that regularly scan your configurations looking for patterns that should never occur. Specifically, you need alerts for:

- Reserved domains (example.com, example.net, example.org, localhost, 127.0.0.1) appearing in routing or DNS configurations

- Test domain prefixes (test-, staging-, dev-, demo-) in production configurations

- Configuration entries pointing to external domains from test systems

- Database fields containing default or placeholder values that should have been updated

- Permissions or access rules with "temporary" or "until [date]" in comments where the date has passed

Second: Implement configuration change verification. Before configuration changes propagate to production, they should pass through verification gates that catch anomalies. That verification should check:

- Is this domain supposed to be routable? (Compare against whitelist)

- Are test domains being used? (Flag them)

- Are credentials going to unexpected destinations? (Detect and flag)

- Is this a configuration pattern that's consistent with past approved changes? (Compare against historical data)

Third: Separate test and production configurations at the database level. If your infrastructure uses the same configuration databases for both test and production, you've created exactly the conditions where test misconfigurations leak into production. Ideally, test and production should use completely separate configuration stores, accessed through different authentication paths, with explicit migration gates between them.

Fourth: Implement configuration expiration. Many organizations have rules like "test accounts must be deleted after 90 days" or "temporary configurations must be reviewed after 30 days." But these rules rarely get enforced automatically. Build systems that automatically disable or flag any configuration that's past its expiration date without explicit renewal.

Fifth: Document the reason for every configuration entry. Every domain routing, every permission assignment, every integration point should have associated documentation explaining why it exists, who created it, when it was created, and what its expiration date is (if applicable). When infrastructure gets reviewed later, you can immediately identify entries that have lost their justification.

The Role of Automation in Modern Infrastructure

Microsoft's problem is fundamentally about automation gone wrong. But the solution isn't less automation—it's smarter automation.

Modern infrastructure is too complex for humans to manage manually. When Microsoft wants to add support for a new domain in their autodiscover system, they don't want to manually edit configuration files on thousands of servers. They use automation to generate, validate, and distribute configurations. That automation makes operations possible at scale.

But automation is only as good as the logic that drives it. If the automation logic has a bug, that bug propagates to thousands of servers instantly. If the automation is missing a validation check, that missing check affects millions of users.

The best organizations implement this layer:

- Configuration generation: Automation creates configurations based on input data

- Static validation: Automated checks verify configurations meet basic requirements

- Semantic validation: Automated checks verify configurations make logical sense

- Test execution: Configurations are tested against test data before deployment

- Canary deployment: Configurations deploy to a small set of servers first

- Monitoring: After deployment, systems monitor for anomalies

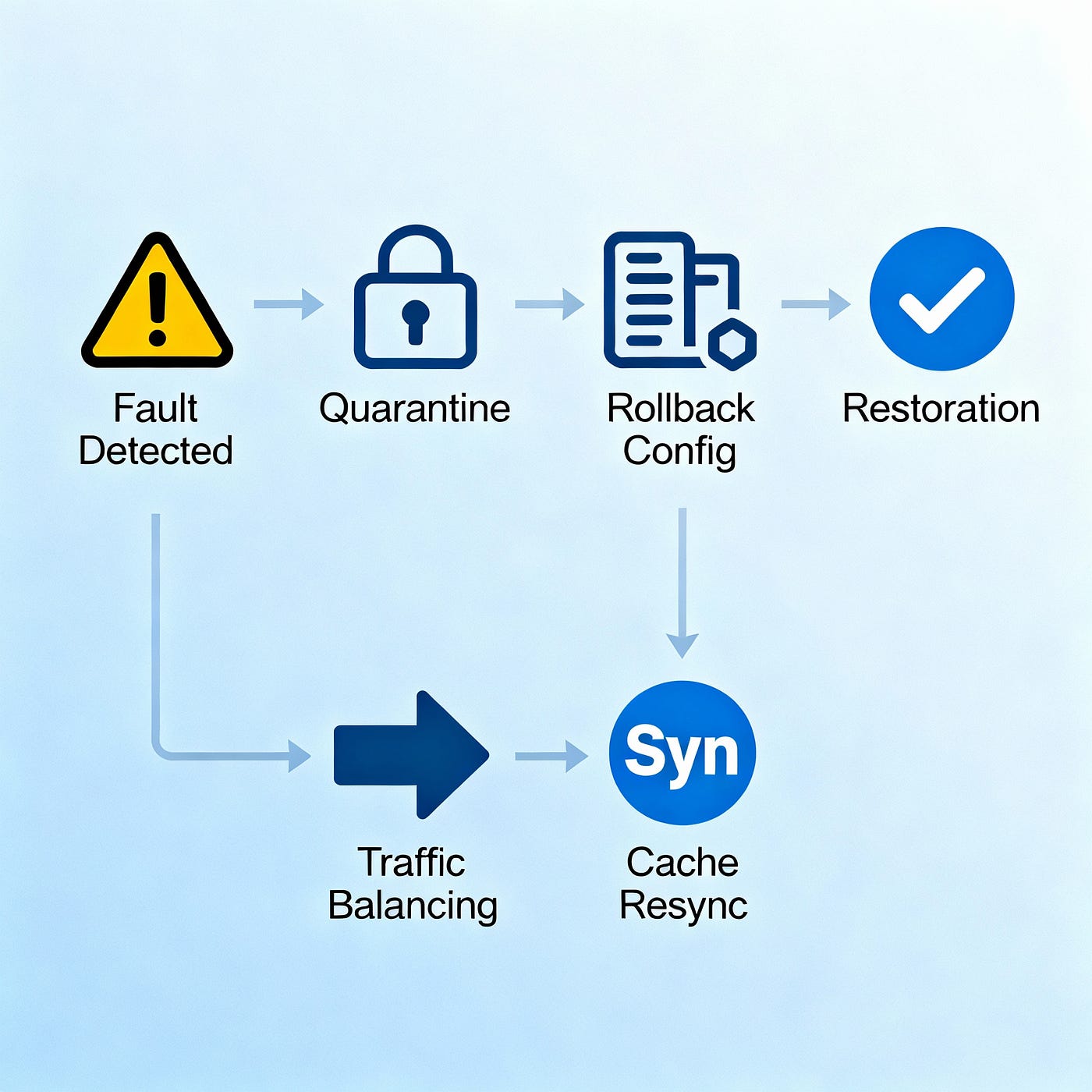

- Automatic rollback: If anomalies are detected, configurations automatically roll back

Microsoft likely has most of these layers. But something in the chain failed. Either:

- The validation didn't catch the problem (which means validation logic was incomplete)

- The testing didn't catch the problem (which means test cases weren't comprehensive)

- The monitoring didn't catch the problem (which means monitoring wasn't sensitive enough to detect routing to external domains)

- The rollback didn't happen (which means the anomaly detection failed to trigger it)

Based on the fact that the misconfiguration lasted years without detection, the most likely culprit is monitoring. Either the monitoring system didn't check for reserved domains in routing configurations, or it didn't alert when they were detected, or alerts were generated but nobody responded to them.

This is actually more common than people realize. Large organizations generate thousands of alerts daily. If alert sensitivity isn't calibrated properly, critical alerts get buried in noise. Or alerts go to teams that don't have time to investigate them. Or alerts use terminology that alerts team doesn't understand, leading to dismissal as false positives.

What This Says About Cloud Infrastructure

Microsoft isn't running small infrastructure. The company operates some of the largest networks in the world. Azure hosts millions of virtual machines. Exchange Online processes billions of emails daily. The configuration complexity is staggering.

When complexity reaches that level, you accept certain truths:

- You will have misconfigurations you don't know about

- You will have security issues you haven't discovered yet

- Your monitoring systems will have blindspots

- Your documentation will be incomplete or outdated

- You will sometimes make mistakes that take years to find

This isn't specific to Microsoft. It's true for AWS, Google Cloud, and every other cloud provider operating at massive scale.

The difference between companies is how they respond. Do they:

- Investigate root causes thoroughly, or just patch symptoms?

- Communicate transparently with users, or hide problems?

- Implement systemic fixes, or local fixes?

- Invest in better tooling to prevent recurrence, or treat each incident as isolated?

Microsoft's response to the example.com misconfiguration—fixing it silently, without detailed explanation—suggests they treated it as an isolated incident that needed immediate patching rather than a systemic problem requiring deep investigation and infrastructure changes.

That approach might be pragmatic in the short term. But it leaves you vulnerable to similar misconfiguration patterns recurring. The underlying problem—insufficient auditing of configuration databases—remains unfixed. When the next misconfiguration happens, there's no guarantee it'll be caught quickly (or at all).

Estimated data showing that legacy system migrations and domain acquisitions are major sources of misconfigurations in large organizations, accounting for over half of the issues.

Practical Steps for Protecting Your Infrastructure

If you operate infrastructure that integrates with external systems or processes sensitive data, here's how to protect yourself:

1. Audit configuration databases quarterly. Set aside time each quarter to manually review configuration entries looking for:

- Entries you don't recognize

- Entries with vague documentation

- Entries pointing to unexpected destinations

- Entries created longer ago than your retention policy allows

2. Implement configuration validation gating. Before any configuration deploys to production, it should pass through verification steps that check for:

- Reserved domains being treated as routable

- Test configurations affecting production systems

- Credentials being routed outside your organization

- Configuration changes that conflict with policy

3. Separate test and production at the system level. Use different authentication, different databases, different networks for test versus production. Make it technically difficult to accidentally mix them.

4. Monitor for configuration anomalies in real-time. Implement systems that continuously monitor for:

- Unexpected routing changes

- New configurations being deployed

- Reserved domains appearing in unexpected places

- Credentials being transmitted to unexpected destinations

5. Implement automatic configuration expiration. Create policies where configurations automatically expire after a certain period unless explicitly renewed. This forces regular review of why configurations exist.

6. Document everything obsessively. Every configuration entry should have a linked justification document explaining:

- What it does

- Why it's needed

- Who approved it

- When it expires (if applicable)

- Who can approve renewal

7. Build configuration rollback capability. If something goes wrong with a configuration deployment, you need to be able to instantly roll back to the previous version. This capability shouldn't exist just for emergencies—it should be part of the normal deployment flow.

The Supply Chain Trust Problem

The example.com misconfiguration highlights a subtle but important supply chain trust issue. When Microsoft integrated with Sumitomo Electric, they created configuration entries for Sumitomo Electric's domains. Those entries then bled into Microsoft's test environments.

This pattern appears repeatedly in modern infrastructure:

- Company A integrates with Company B

- Configuration entries get created for Company B's systems

- Test configurations in Company A's environment reference Company B's domains

- If test and production configurations aren't properly isolated, test traffic can escape to Company B's systems

- Company B's infrastructure now has unexpected traffic arriving from Company A

- Both companies' security teams are confused and suspicious

This is why zero-trust architecture has become popular. Zero-trust means every communication requires explicit verification, even between systems that should trust each other. Instead of assuming that traffic coming from Microsoft's network is legitimate, Sumitomo Electric should verify the source, the credentials, and the authorization for every request.

But zero-trust requires more infrastructure, more monitoring, and more complexity. It's not a panacea. In this case, zero-trust wouldn't have prevented test credentials from being sent to Sumitomo Electric's servers. It would just make those communications require additional verification.

The real solution is the separation problem: test and production traffic should never be allowed to mix. Not just at the application level, but at the infrastructure level. Different networks, different credentials, different routing rules.

Organizational and Technical Debt Connection

There's a fascinating connection between technical debt and configuration mismanagement. Technical debt refers to accumulated shortcuts and workarounds that make future changes harder. Configuration debt follows the same pattern.

When Microsoft first created configurations for Sumitomo Electric's domains, they probably did it quickly to meet an integration deadline. They created the minimum necessary configuration entries to make the integration work. Years later, organizational restructuring happened. Divisions changed. People left. The original rationale for those configuration entries became lost.

Meanwhile, in the test environment, someone might have created example.com entries during some development project. That project shipped, but the test configuration entries weren't cleaned up. Five years later, nobody remembers that example.com entries exist in the test database.

Then an automated configuration synchronization process copies test configurations into production configuration databases (or vice versa). Or someone notices sei.co.jp entries in production and copies them to test without verifying what they do. Or a wildcard pattern in a database query accidentally matches both sei.co.jp and example.com.

Each of these seems like a minor issue individually. Cumulatively, they created a situation where a reserved domain was routing to an external company's servers.

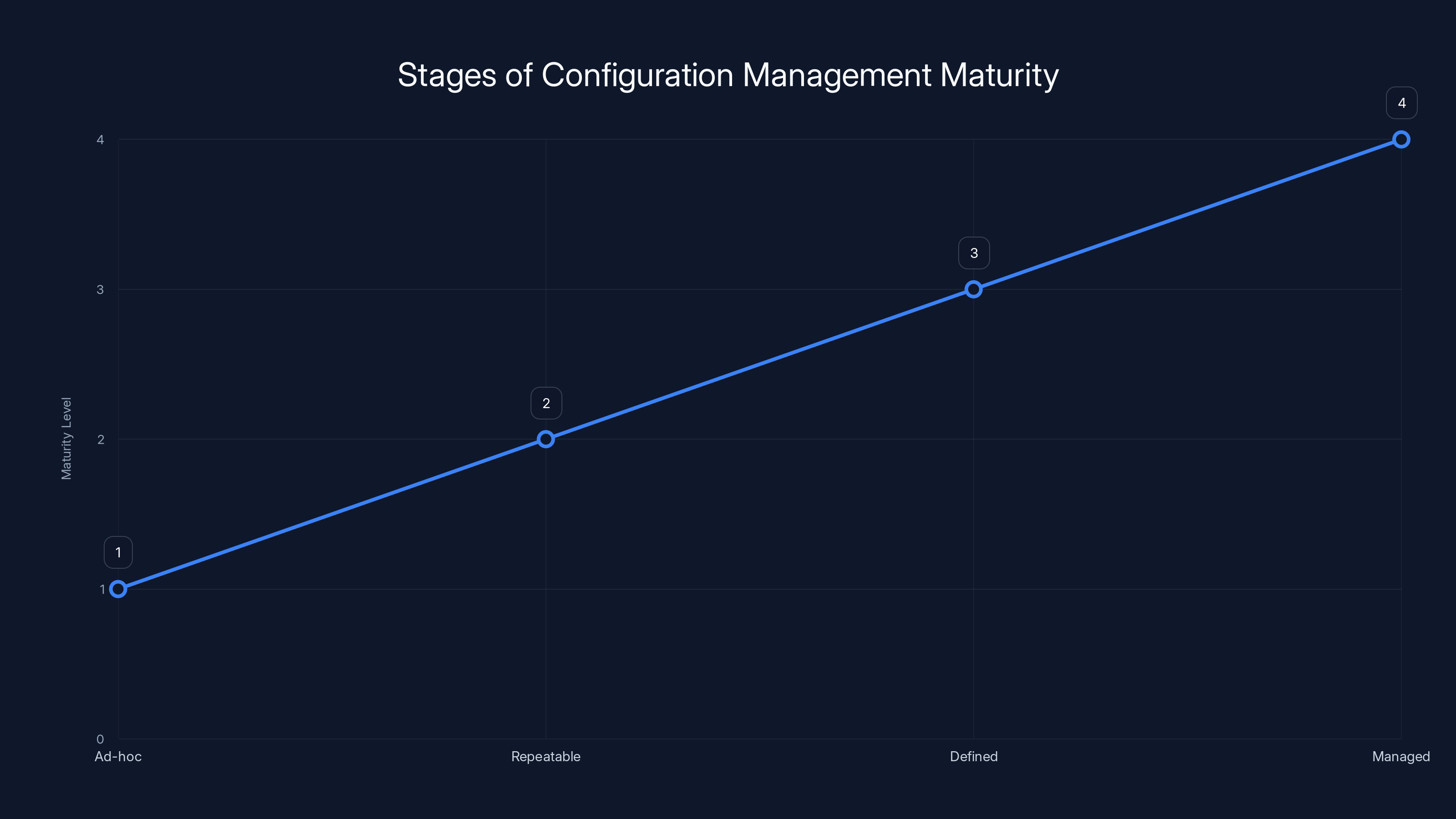

This is why infrastructure teams increasingly focus on configuration management maturity. It's not sexy. It doesn't get press coverage when done right. But it prevents situations like this from occurring.

Configuration management maturity typically follows stages:

- Ad-hoc: Configurations are changed manually by whoever needs them

- Repeatable: Standard processes exist for common configuration changes

- Defined: Processes are documented and consistently followed

- Managed: Configuration changes are tracked, reviewed, and validated

- Optimized: Configuration management is fully automated with human oversight

Microsoft is probably operating at level 3 or 4 in most systems. But the example.com incident suggests some configuration paths are still stuck at levels 2 or 3, where change management is inconsistent.

Configuration management maturity progresses from ad-hoc to managed, reducing risks of technical debt. Estimated data.

The Detection Problem: Why It Took Years

According to reports, this misconfiguration lasted five years. Five years is a long time for an obvious problem to remain undetected.

Several factors probably contributed:

First, reserved domains are rarely tested. Most testing uses fictional domains (asdf.test, foobar.local) or domains the company owns. Few organizations regularly test with RFC 2606 reserved domains because those domains should never be routeable. Testing them feels like it shouldn't matter.

Second, monitoring typically focuses on known issues. Infrastructure teams create alerts for problems they've seen before or problems they're specifically looking for. Misconfigured routing to external domains for reserved domains is unusual enough that it might not be on anyone's monitoring checklist.

Third, the misconfiguration only appeared if you asked for it. The problematic behavior wasn't broadcasting test traffic to external servers automatically. It only returned configuration information when someone specifically queried the autodiscover endpoint for an example.com address. Unless your testing specifically included that scenario, you wouldn't notice it.

Fourth, test data doesn't always look suspicious. If test credentials showed up in Sumitomo Electric's email logs, the IT team there would just see authentication attempts for example.com addresses. They might attribute those to Microsoft's test environment contacting them for integration testing, which would be expected during integration work.

Fifth, large organizations have too much data to analyze. Sumitomo Electric probably generates millions of log entries daily. A handful of authentication attempts from test addresses would be lost in the noise.

The person or team that discovered this—presumably someone systematically testing Microsoft's autodiscover endpoints—specifically looked for this scenario. They didn't find it by accident. They were testing reserved domains deliberately, which is excellent security practice but not common.

This points to a broader security lesson: The kinds of tests you do determine the kinds of vulnerabilities you find. If your testing is focused on "normal" operations, you'll find vulnerabilities in normal operations. If you specifically test edge cases and reserved domains and unusual configurations, you'll find those kinds of vulnerabilities instead.

Future Prevention: Building Systems That Don't Make This Mistake

If you were designing Microsoft's autodiscover system knowing this vulnerability existed, how would you prevent it?

The cleanest solution at the application layer would be explicit allowlisting. Before the autodiscover service returns configuration for any domain, it should check:

if domain in RESERVED_DOMAINS:

return error("Reserved domain not allowed")

if domain not in APPROVED_DOMAINS:

return error("Domain not configured")

return configuration_for(domain)

This way, example.com would be explicitly rejected at the application level. No database lookup needed. No routing rule matters. The application simply refuses to return configuration for reserved domains.

At the database layer, you'd want constraints that prevent reserved domains from ever being added to configuration tables:

sqlALTER TABLE autodiscover_config

ADD CONSTRAINT no_reserved_domains

CHECK (domain NOT IN ('example.com', 'example.net', 'example.org', ...));

At the infrastructure layer, you'd want automated scans that regularly check for reserved domains:

bashSELECT * FROM autodiscover_config

WHERE domain IN ('example.com', 'example.net', 'example.org')

OR domain LIKE 'test.%'

OR domain LIKE 'staging.%'

OR domain LIKE 'dev.%';

And you'd want alerts that fire whenever such a query returns any results:

IF (reserved_domain_found):

ALERT(critical)

PAGE_ONCALL(immediately)

AUTO_TICKET(security_team)

Implementing even two of these three layers would have prevented this incident from lasting five years. Implementing all three would make it nearly impossible.

But here's the thing: Microsoft probably already has systems similar to all three. The fact that this incident lasted five years anyway suggests that:

- These systems exist but aren't being run regularly

- They exist but their output isn't being monitored

- They exist but they're ineffective at catching this specific pattern

- They don't exist, which suggests gap in infrastructure governance

Any of these explanations points to organizational issues rather than technical issues. The technology to prevent this exists. The organization isn't using it effectively.

Comparing to Historical Infrastructure Incidents

This incident isn't unique. Major technology companies have experienced similar configuration mismanagement problems.

The Google Phishing Incident (2013): A security researcher discovered that Google's own employees were vulnerable to phishing attacks because Google's internal authentication system could be confused about which version of Gmail was legitimate. The issue wasn't a specific configuration mistake but a design flaw that made configuration mistakes possible.

The AWS Route 53 Misconfiguration (2021): Organizations using AWS's Route 53 DNS service sometimes misconfigured their domain settings, accidentally pointing their domains to AWS placeholder IP addresses instead of their actual web servers. This affected numerous companies and websites briefly.

The Facebook BGP Hijack (2014): Someone misconfigured Facebook's border gateway protocol (BGP) announcements, causing the company's traffic to route through a different provider briefly. This was caught quickly by internal monitoring, but it demonstrated how routing configuration mistakes can happen even at companies with sophisticated infrastructure.

The Microsoft Test Account Admin Privilege Incident (2024): As mentioned earlier, a test account had administrative privileges granted and forgotten. This is pure configuration management failure—someone created an entry in the admin accounts database and failed to remove it when the account was no longer needed.

Comparing these incidents:

- All involved configurations that should have been caught by automated systems

- All took longer to discover than necessary

- All were fixed through emergency patching rather than root cause correction

- All revealed gaps in infrastructure governance and monitoring

The pattern suggests this is endemic to very large organizations operating at massive scale. When you manage configurations for millions of resources across thousands of servers, some misconfigurations will slip through. The question becomes how quickly you detect them and how thoroughly you investigate.

The Broader Implications for Cloud Users

If you're a customer of Microsoft 365, Azure, or any Microsoft cloud service, what should you take from this?

First, understand that cloud providers operate infrastructure too large to be flawless. Misconfigurations will happen. The question isn't whether they'll happen—it's how quickly they'll be discovered and fixed.

Second, don't assume that test domains are actually safe from routing. Test domains should be safe according to standards, but if a cloud provider misconfigures its system, test domains might route unexpectedly. Don't send real credentials through test domains, even in theory.

Third, consider the trust model carefully. When you use a cloud provider's email service, you're trusting that provider to correctly route your email. A misconfiguration could theoretically cause your email to be misdirected (though Microsoft's situation involved test email, not production email).

Fourth, understand that "fixed" by a cloud provider doesn't always mean thoroughly investigated and systematically prevented. It might just mean the symptom was made to stop appearing.

Microsoft has a reputation as one of the more professionally-run cloud providers, with strong security practices. But even they have configuration management gaps and incident response that prioritizes symptom relief over root cause investigation.

If you're evaluating cloud providers, configuration management practices are worth asking about:

- Do they regularly audit configuration databases?

- Do they have automated checks for reserved domains?

- Do they test using RFC 2606 reserved domains as part of security testing?

- How long does it typically take them to discover misconfigurations?

- What's their typical incident response process—emergency fix or thorough investigation?

- Do they publish postmortems on major incidents?

Looking Forward: The Complexity Cost

As cloud infrastructure becomes more complex, configuration management becomes harder. This is a fundamental scaling problem without perfect solutions.

The tools are getting better. Infrastructure as code (Ia C) helps by making configurations version-controlled and testable. Continuous deployment systems can validate configurations before they go live. Automated scanning can look for obvious mistakes. But none of these solve the fundamental problem: complexity grows faster than our ability to manage it.

At some point, organizations hit a complexity ceiling. They have so many configuration dependencies, so many edge cases, so many integration points that they can't possibly audit everything manually or even automatically. The configuration surface area becomes too large.

Microsoft is probably approaching or at that ceiling. The company operates more infrastructure than most countries. Managing it involves layers and layers of abstraction, automation, and integration points. Mistakes are statistically inevitable.

The best organizations can do is:

- Implement multiple layers of detection (so if one layer misses something, another catches it)

- Detect problems as quickly as possible (5 years is too long)

- Investigate thoroughly rather than patching symptoms

- Share lessons learned with the industry

- Continuously invest in better tooling and processes

Microsoft seems to be doing 1, 3, and 5 in various forms. But the 5-year detection time suggests room for improvement on 2. And the emergency patch without published postmortem suggests they might not be doing 4.

FAQ

What is RFC 2606 and why does it matter?

RFC 2606 is an internet standard that reserves three domains—example.com, example.net, and example.org—for testing and documentation purposes. The IETF guarantees these domains will never be registered to anyone, so they're safe for developers and testers to use without risk of accidentally contacting real systems or real people.

How did example.com end up in Microsoft's autodiscover configuration?

Microsoft never publicly explained the root cause, but the most likely scenarios involve: a test configuration entry that wasn't cleaned up, a misconfigured pattern match that accidentally included reserved domains, or template expansion logic that produced incorrect results. Given that Sumitomo Electric was integrating Microsoft 365, domain entries for their servers may have been created and then inadvertently included test domain entries through automated processes.

What credentials were actually exposed?

Officially, only test credentials were exposed—fictional email addresses using example.com. However, the incident revealed that Microsoft's autodiscover system could be tricked into routing test domain queries to external servers, which could potentially be exploited to discover routing patterns or observe authentication attempts. Since test credentials are sometimes variations of real credentials, the exposure was concerning even if the credentials themselves were nominally "test-only."

Did Sumitomo Electric do anything wrong?

No. Sumitomo Electric was legitimately integrating Microsoft 365 for their operations. The misconfiguration was entirely Microsoft's problem—their autodiscover system routed to Sumitomo Electric's servers without Sumitomo Electric's knowledge or intention. Sumitomo Electric was an innocent third party in this incident.

How long did the misconfiguration last?

According to reports from security researchers, the misconfiguration lasted approximately five years before being discovered and corrected. This represents a significant gap in Microsoft's detection and monitoring systems, as the problem was observable through simple testing of the autodiscover endpoint with reserved domains.

Is my email safe with Microsoft 365 after this incident?

Production email routing wasn't affected—only test domain configurations were misconfigured. However, the incident demonstrates that configuration management gaps exist in Microsoft's infrastructure, which should motivate the company to improve auditing, monitoring, and testing practices. For most users, Microsoft's email service remains secure and reliable, but the incident is a reminder that even major providers have configuration management vulnerabilities.

What would a proper fix have looked like?

A thorough fix would have involved: auditing all configuration databases for other instances of reserved domains, implementing automated checks to prevent reserved domains from being added to routing configurations, running regression tests across all autodiscover configurations, reviewing all sei.co.jp entries to verify they're legitimate, and implementing continuous monitoring to detect similar issues early. Microsoft's actual fix appears to have been an emergency block that prevented the endpoint from returning configuration information, which stops the immediate problem but doesn't address underlying configuration database issues.

How can my organization prevent similar misconfigurations?

Implement multiple layers: explicit allowlisting of permitted domains in application code, database constraints that prevent reserved domains from being added, automated scans for anomalies, comprehensive documentation of why each configuration entry exists, separation of test and production configurations at the system level, and regular manual audits of configuration databases. Focus especially on reserved domains, test domain prefixes, and external routing destinations.

Does this indicate Microsoft has poor security practices?

Not necessarily. Configuration management at scale is extremely challenging for all large organizations. AWS, Google Cloud, and other major providers have experienced similar incidents. What matters is how thoroughly companies investigate root causes and how seriously they take systemic improvements. Microsoft's emergency patching approach rather than published postmortem suggests the incident wasn't treated as seriously as it warranted.

What does this mean for my choice of email provider?

This incident doesn't suggest Microsoft's email service is unsafe—production email routing wasn't affected. However, it does suggest configuration management is an area where even major providers have gaps. When evaluating any cloud provider, ask specifically about their configuration management practices, incident detection processes, and how they share lessons learned from incidents.

Key Takeaways

Microsoft's example.com routing misconfiguration represents a valuable case study in how configuration management breaks down in massive-scale infrastructure environments. The incident demonstrates several critical lessons:

The complexity ceiling: Infrastructure becomes so complex that manual auditing becomes impossible, and automated systems develop blindspots that even well-resourced organizations miss.

Test/production contamination: When test and production configurations share systems or databases, test misconfiguration can leak into production. Physical separation is essential.

Monitoring maturity: Detection took five years, suggesting monitoring systems either weren't specifically checking for reserved domains in routing configurations, or alerts weren't being acted upon.

Reserve domains matter: RFC 2606 reserved domains (example.com, example.net, example.org) are safety tools. Systems that violate these reservations create risk, even if the risk seems theoretical.

Emergency patches aren't fixes: Microsoft's quick patch made the problem stop appearing, but didn't address underlying configuration database issues. Root cause investigation is crucial.

Supply chain trust boundaries: When integrating with external partners, maintain strict boundaries between their production systems and your test environments. Misconfiguration should not leak across organizational boundaries.

Configuration debt accumulates: Old entries, forgotten purposes, and unclear documentation about why configurations exist create perfect conditions for misconfigurations to persist undetected.

For infrastructure teams, this incident underscores the importance of treating configuration management as a first-class security concern. The organizations that excel at preventing configuration misconfigurations do so through intentional systems, not through hoping human review will catch problems. Given the complexity of modern infrastructure, hope isn't a strategy.

Related Articles

- FortiGate Under Siege: Automated Attacks Exploit SSO Bug [2025]

- TikTok Data Center Outage: Inside the Power Failure Crisis [2025]

- TikTok's US Data Center Outage: What Really Happened [2025]

- OpenAI Scam Emails & Vishing Attacks: How to Protect Your Business [2025]

- Gmail Inbox Filtering Crisis: What's Breaking and How to Fix It [2025]

- AMD vs Intel: Market Share Shift in Servers & Desktops [2025]

![Microsoft's Example.com Routing Anomaly: What Went Wrong [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-example-com-routing-anomaly-what-went-wrong-2025/image-1-1769463736502.jpg)