The Problem We've Been Ignoring

Here's something that keeps data scientists up at night: everything we store today might be unreadable in 50 years. Your hard drive will fail. Magnetic tape degrades. Even the servers that could read your format might not exist anymore. We're creating massive amounts of data—estimates suggest the world generates 120 zettabytes annually—but we haven't solved the fundamental problem of keeping it safe for centuries.

Archival storage is genuinely hard. You need a medium that's physically durable, chemically stable, and resistant to temperature swings, moisture, and electromagnetic interference. You need it to be dense enough that you're not storing petabytes across basketball courts. You need it to be readable without consuming power just sitting on a shelf. And ideally, you'd like it to last long enough that nobody alive will see it degrade.

Several ideas have floated around scientific circles for years. DNA storage is elegant in theory—it's been around for 3.8 billion years, so stability seems guaranteed. But reading and writing DNA remains slow and expensive. Some researchers proposed quantum storage, others suggested exotic crystalline structures. But one of the simplest ideas kept resurfacing: etch data into glass.

The appeal is obvious when you think about it. Glass surrounds us. It's stable—the oldest known glass objects are thousands of years old and show minimal deterioration. It doesn't require electricity to preserve data. It's not subject to magnetic decay or bit rot. A variety of different chemical compositions can form glass, meaning researchers could optimize for stability rather than accepting whatever properties a hard drive manufacturer happened to use.

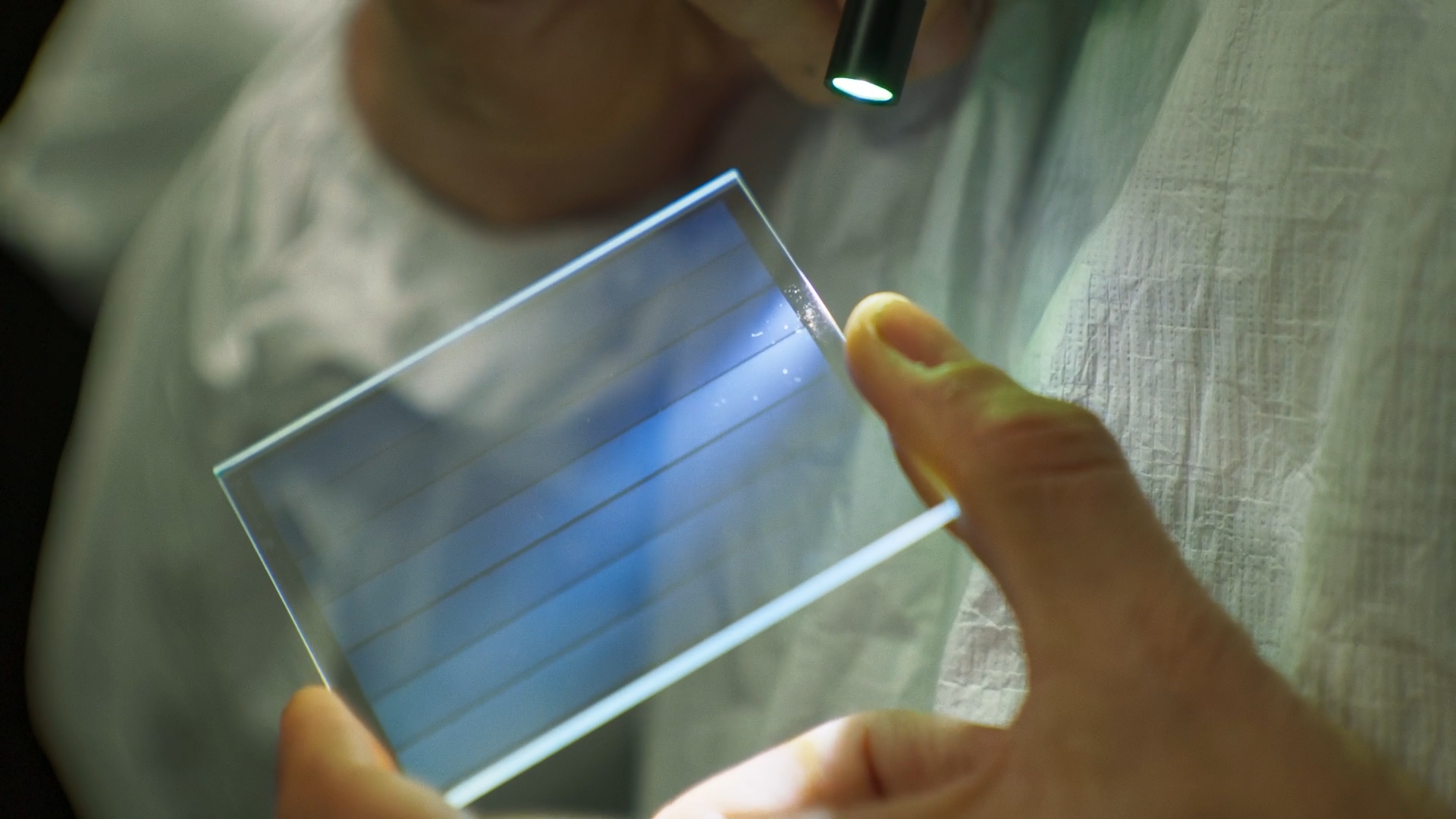

The challenge was always the same: how do you actually put data into glass quickly enough to make it practical, and then read it back reliably? For years, this remained mostly theoretical. But in February 2026, Microsoft Research announced Project Silica, and they didn't just propose the idea. They built a working system that actually works.

Why Glass Makes Sense

When most people think about glass, they think about something fragile. Windows break. Glasses shatter. There's this old myth that glass flows over centuries, which isn't true, but it captures a sense that glass is somehow unstable.

Reality is more nuanced. Glass isn't a single material. It's a category of materials—amorphous solids formed by rapidly cooling molten material. Depending on what chemicals you start with, you can create glasses with radically different properties. Some glasses are soft and melt easily. Others are extremely hard and chemically inert.

The researchers working on Project Silica chose their materials specifically for archival stability. They created a glass composition that's thermally stable (won't expand or contract dramatically with temperature changes), chemically resistant (won't react with water vapor or oxygen), and physically durable (resists mechanical stress). This isn't some exotic new material—it's based on well-understood chemistry, but optimized ruthlessly for the specific problem of long-term data storage.

The stability is almost freakish. Glass doesn't develop bit rot. It doesn't require occasional "refreshing" like tape or magnetic media. A piece of glass sitting in a vault will remain readable for millennia as long as you don't physically shatter it. This addresses one of the deepest problems in digital archival: the problem of "format obsolescence." Right now, we store data on devices that become unreadable when the hardware fails. Glass eliminates this problem entirely. If you have the right reader technology, the data will still be there.

There's another advantage that often gets overlooked: glass doesn't need active cooling or environmental control to maintain data integrity. A hard drive requires climate control, electricity, and active error correction. A piece of glass just sits there. This matters when you're thinking about truly long-term storage. Over centuries, maintaining infrastructure becomes impossibly expensive. With glass, you're betting that the infrastructure will be replaced, but the data itself requires nothing.

Manufacturing challenges and write speed are the most significant hurdles for Project Silica, with high impact scores of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data.

Femtosecond Lasers: Making It Actually Work

Okay, so glass is stable. Great. But how do you actually write data into it?

Traditional laser etching works, but it's slow. You focus a laser beam and let it burn or vaporize material. The problem is that it's hard to focus tightly enough, and it's slow enough that you couldn't hope to write terabytes of data in reasonable time. The theoretical limit is something like gigabits per second with conventional approaches, which sounds fast until you realize you're trying to store terabytes.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected direction: femtosecond lasers. These aren't new technology—they've existed for decades—but they're expensive and had mostly been confined to scientific research. A femtosecond is 10^-15 seconds, which is an absurdly short timespan. These lasers emit pulses of light lasting less than a billionth of a second, and they can fire millions of these pulses per second.

Why does this matter? When light hits matter for such an incredibly short period, something interesting happens. The energy density becomes so high that it creates effects you don't see with continuous or longer-pulse lasers. You can create incredibly precise structures. You can focus the laser's energy in a very small volume without heating the surrounding material excessively. And you can make features that are smaller than the diffraction limit of light.

For data storage specifically, femtosecond lasers enable you to create three-dimensional structures within the glass. You're not limited to etching the surface. You can create layers of data separated by enough distance that they don't interfere with each other optically. The Microsoft team created systems with multiple layers of data within a single piece of glass, stacked at distances where each layer would appear in focus during microscopy without the neighboring layers interfering.

The write speed they achieved was 66 megabits per second per laser. That sounds reasonable, except remember that they're writing 4.84 terabytes into a single glass slab. Do the math: that's 150 hours to fully write a slab. For comparison, writing the same amount of data to a conventional hard drive would take maybe 10 hours. So glass is slower to write, but the researchers showed it's possible to use multiple lasers simultaneously—they used four in their demonstration, and the team believes you could use up to 16 lasers writing to the same slab without generating too much heat.

Femtosecond lasers significantly outperform traditional lasers in data writing speed, achieving 66 megabits per second compared to just 1 megabit per second with traditional methods. Estimated data.

How Data Actually Gets Encoded

The clever part of Project Silica isn't just writing data into glass. It's how they encode the data so that it can be read reliably despite the inherent challenges of optical storage in three dimensions.

They developed two different approaches, and both are interesting in their own ways.

The first approach uses something called birefringence. This is a property where a material refracts light differently depending on the polarization of the light. Imagine shining polarized light through the glass. If there's birefringence, different polarizations will refract at different angles. The researchers use this effect to create tiny, oriented void structures in the glass. A single femtosecond laser pulse creates an oval-shaped void, and then a second, polarized laser pulse induces birefringence in that void. The orientation of that oval encodes data. Because they can resolve multiple different orientations, they can store more than just a binary 0 or 1 in each voxel (a voxel being the smallest unit of storage).

The second approach is simpler from a physics perspective. Instead of varying the orientation of structures, it varies the magnitude of the refractive effect by adjusting the energy in the laser pulse. A bigger pulse creates a stronger refractive effect, a smaller pulse creates a weaker effect. By carefully controlling the laser power, you can create multiple distinguishable states. Again, this means you can store multiple bits per voxel.

Each approach has tradeoffs. The birefringence method is denser—it can pack more data into the same volume—but it requires higher-quality glass and more sophisticated optical hardware. The energy variation method works on any transparent material and uses simpler hardware, but stores roughly half the data (just over 2 terabytes instead of 4.84 terabytes per slab).

Once the voxels are created, the data needs error correction. The researchers used something called low-density parity-check codes, which are the same error correction codes used in 5G networks. This is important because reading data from glass isn't perfect. There's noise, there's optical interference between layers, there's imperfection in how the voxels were created. The error correction allows the system to read the data reliably despite these imperfections.

Finally, neighboring bits are combined to create symbols that take advantage of each voxel's ability to store multiple bits. This optimization layer makes sure you're using the storage capacity efficiently. The whole bitstream gets encoded, error correction applied, symbols created, and only then is it ready to be written to glass.

Reading Data Back Out

Writing data into glass is only half the problem. You need to read it back out reliably.

The reading system uses phase contrast microscopy, which is a well-established optical technique. Phase contrast microscopy doesn't require staining or other modifications to the sample—it just uses differences in optical properties (refractive index) to create contrast. Since each voxel was created to have a different refractive index than the surrounding glass, you can see them under phase contrast microscopy.

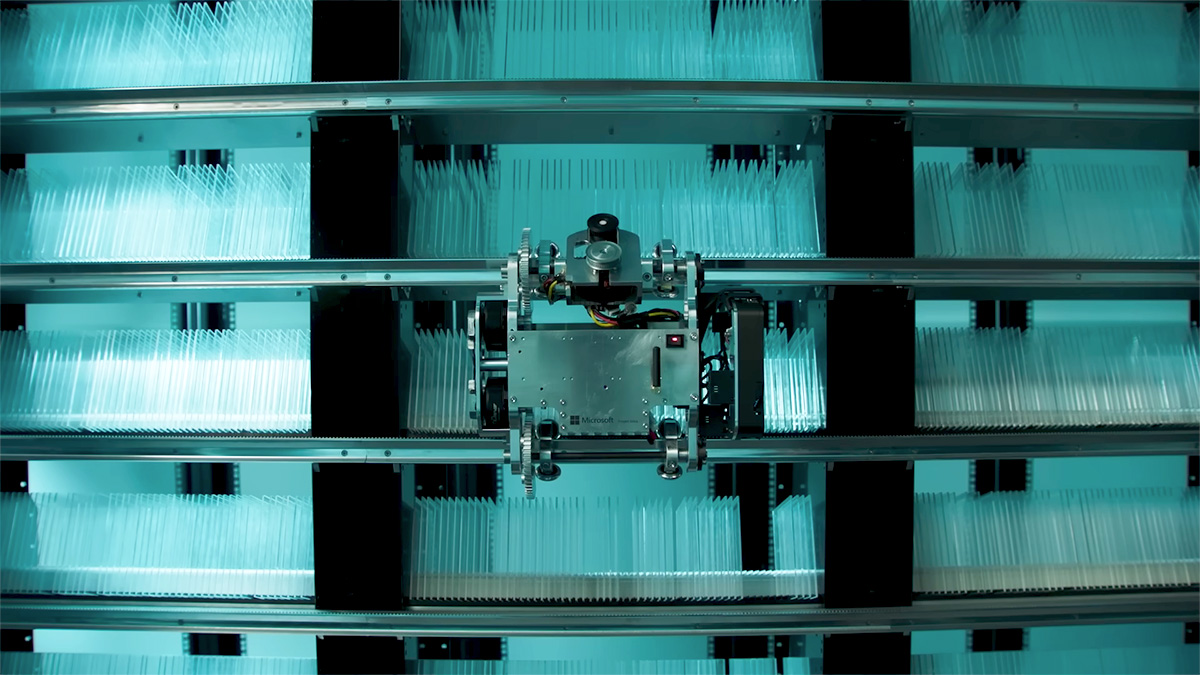

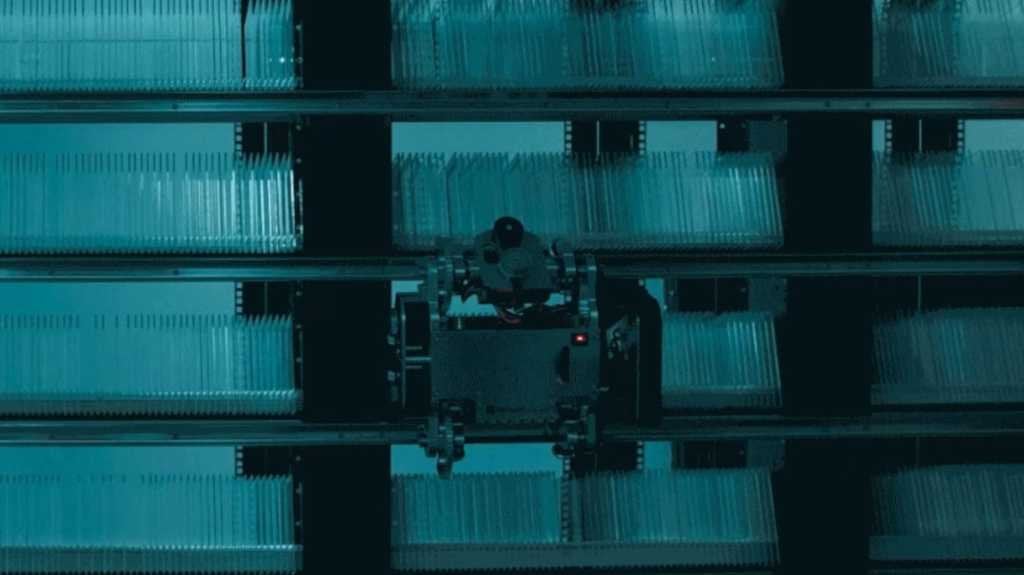

The automated system positions the microscope lens above specific points on the glass slab using alignment markers that were etched during the writing process. It then slowly changes its focal plane, moving through the stack of layers and capturing images of different layers. Here's where it gets clever: the system uses a convolutional neural network to interpret these microscope images.

Why use AI? Because optical microscopy, even phase contrast microscopy, isn't perfect. Voxels that are in the plane of focus appear clear, but voxels in nearby layers still appear as subtle optical artifacts. A human trying to interpret these images would have a hard time distinguishing signal from noise. A neural network trained on thousands of microscope images can do it effectively. The AI learns to recognize how neighboring voxels affect the appearance of a given voxel, and it uses that information to read the data accurately.

This is a beautiful example of how modern data storage combines classical physics (femtosecond lasers, phase contrast microscopy) with modern machine learning to solve a problem that wouldn't be solvable any other way.

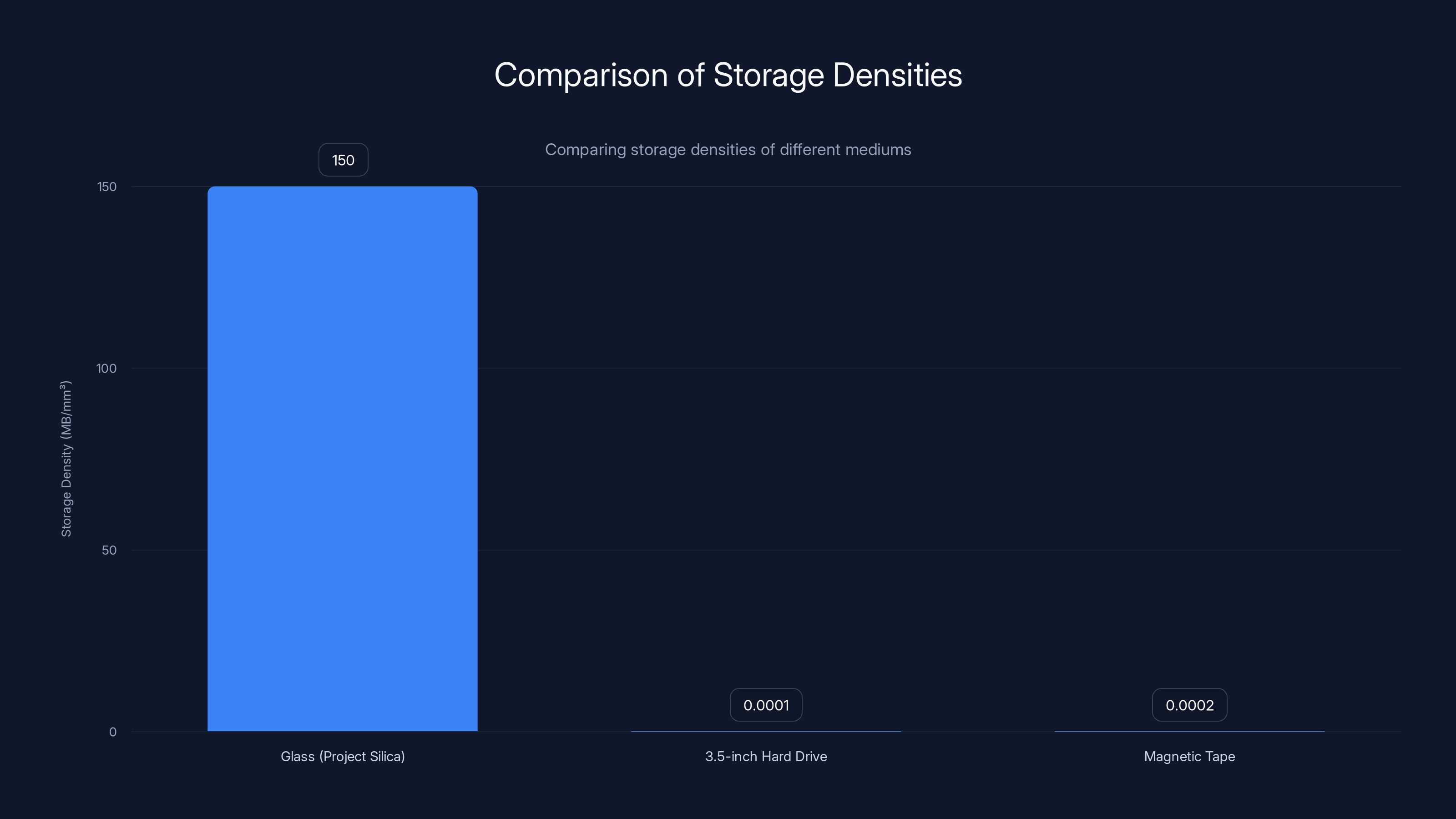

Glass used in Project Silica achieves a remarkable storage density of 150 MB/mm³, vastly outperforming traditional hard drives and magnetic tapes. Estimated data for comparison.

Storage Density That Breaks Your Brain

Let's talk about the actual numbers, because they're genuinely impressive.

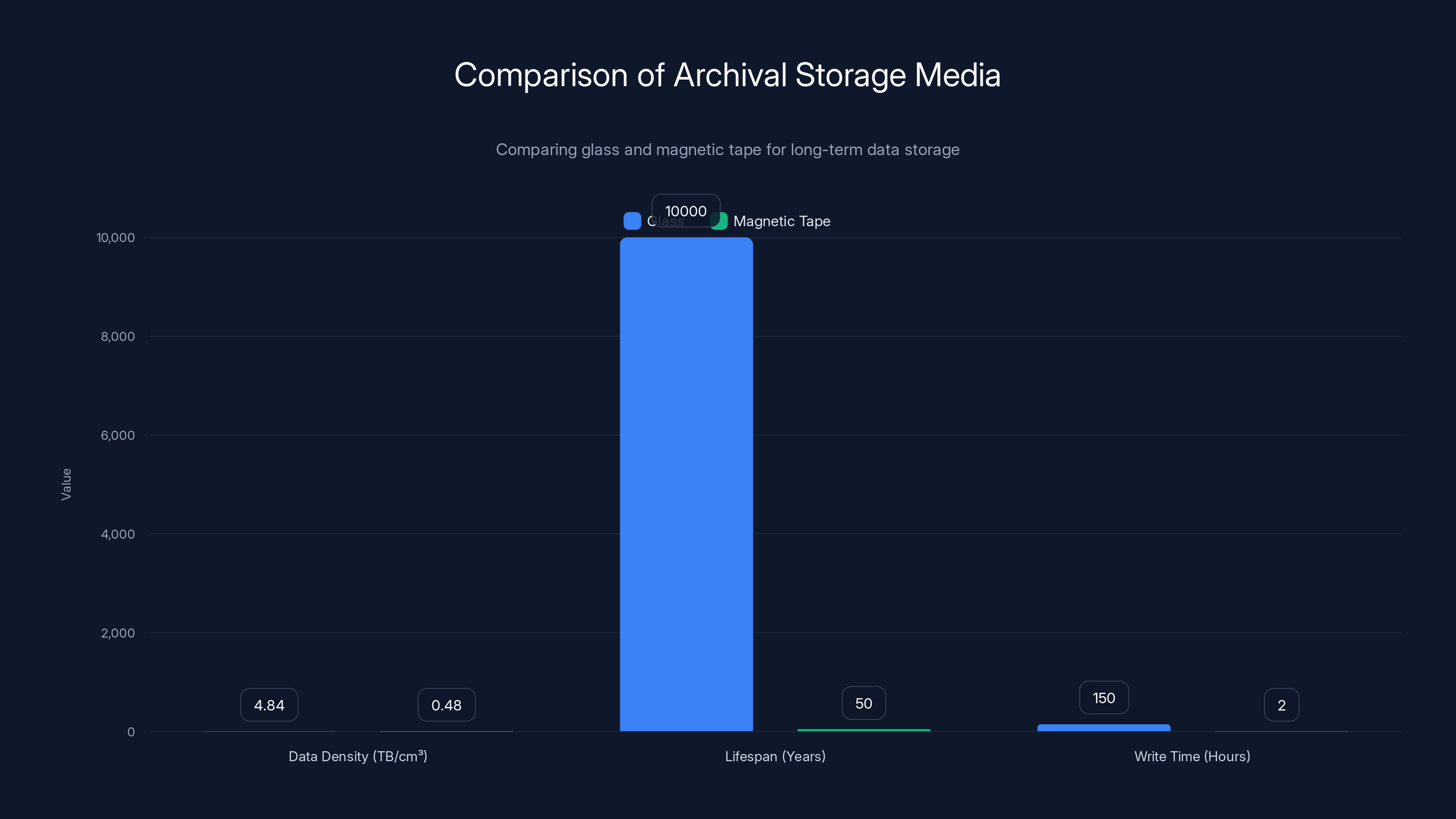

A single slab of glass used in Project Silica is 12 centimeters by 12 centimeters and just 2 millimeters thick. That's not a large piece of glass. You could hold it in your palm. Yet it can store up to 4.84 terabytes of data, possibly going higher with further optimization.

To put that in perspective, consider the storage density. The researchers achieved over 150 megabytes per cubic millimeter. A cubic millimeter is genuinely tiny—about the size of a grain of salt. If you could somehow fill a shoe box with this glass storage medium, you'd have nearly 4 petabytes of data.

For comparison, a standard 3.5-inch hard drive stores roughly 12 terabytes and is physically much larger. Magnetic tape, which is what large enterprises actually use for long-term archival, stores maybe 15-20 terabytes per cartridge and takes up significantly more space. Glass is in another category entirely.

This density matters for more than just the "wow factor." Density affects cost per gigabyte. It affects how much you can transport or store. It affects whether long-term archival becomes economically practical at scale. Right now, archival storage for scientific data, government records, and digital libraries is expensive and requires active management. If you can increase density by an order of magnitude, you fundamentally change the economics of the problem.

But there's a tradeoff: write speed. The 66 megabits per second write rate means that filling a 4.84-terabyte slab takes about 150 hours. That's six days of continuous writing. For many use cases, this is fine—you're writing archival data infrequently, and you don't need it to be written instantaneously. But for real-time data ingestion or live backup scenarios, this would be too slow.

The Microsoft team acknowledged this and showed that scaling to 16 simultaneous lasers would be technically feasible. That would increase write speed proportionally, bringing full-slab write times down to around 24 hours. Still not fast by modern standards, but acceptable for archival scenarios where you're writing massive datasets once or infrequently.

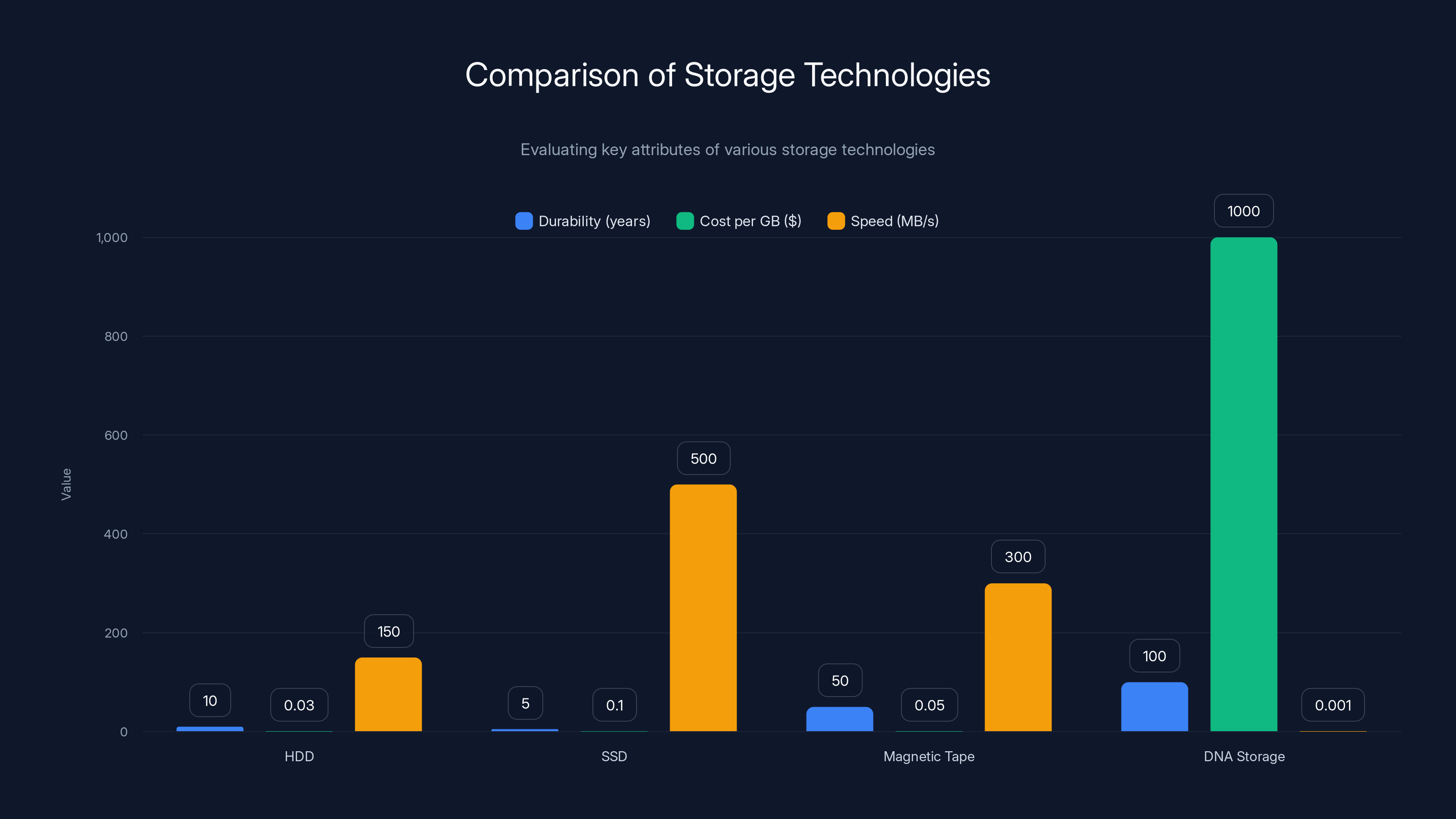

Comparing Storage Technologies

It's useful to step back and think about how glass storage fits into the broader landscape of data storage technologies.

Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) remain the workhorse of data centers. They're fast, relatively cheap, and well-understood. But they're mechanical, which means they fail. A typical HDD has a Mean Time Between Failures of 5 to 10 years in consumer use, maybe longer in data center conditions with proper cooling and humidity control. They require active power consumption to maintain. They're terrible for long-term archival because the media degrades and the hardware becomes obsolete.

Solid-State Drives (SSDs) are faster than HDDs and have no moving parts, but they have their own reliability problems. Flash memory cells degrade with each write cycle. The controller chips can fail. And they still require occasional power to maintain data integrity. For truly long-term storage, SSDs are even worse than hard drives because flash memory degrades faster in some scenarios.

Magnetic Tape is what enterprises actually use for archival. A tape cartridge can store 15-20 terabytes and might cost $500-1000 per cartridge. Tape is surprisingly durable and can last 30-50 years if stored properly. The big problem is that you need to actively maintain the infrastructure. Tape drives break. Format support disappears. You need climate-controlled vaults. It's a solution that works, but it's expensive and requires constant infrastructure investment.

DNA Storage is another theoretical approach that's received a lot of research funding. DNA is incredibly stable and incredibly dense. Theoretically, you could fit the entire Library of Congress into a gram of DNA. But reading and writing DNA remains slow and expensive. Current DNA storage costs thousands of dollars per gigabyte, and speeds are measured in kilobits per second. For archival, this might eventually make sense, but the technology isn't ready for practical deployment.

Glass Storage sits in an interesting middle ground. It's denser than tape. It's more stable than any electronic storage media. It requires minimal infrastructure to maintain. It doesn't have the high read/write costs of DNA. The main limitation is write speed—it's slower than tape to initially write data. But for the specific use case of long-term archival storage where you write once and read rarely, it might be ideal.

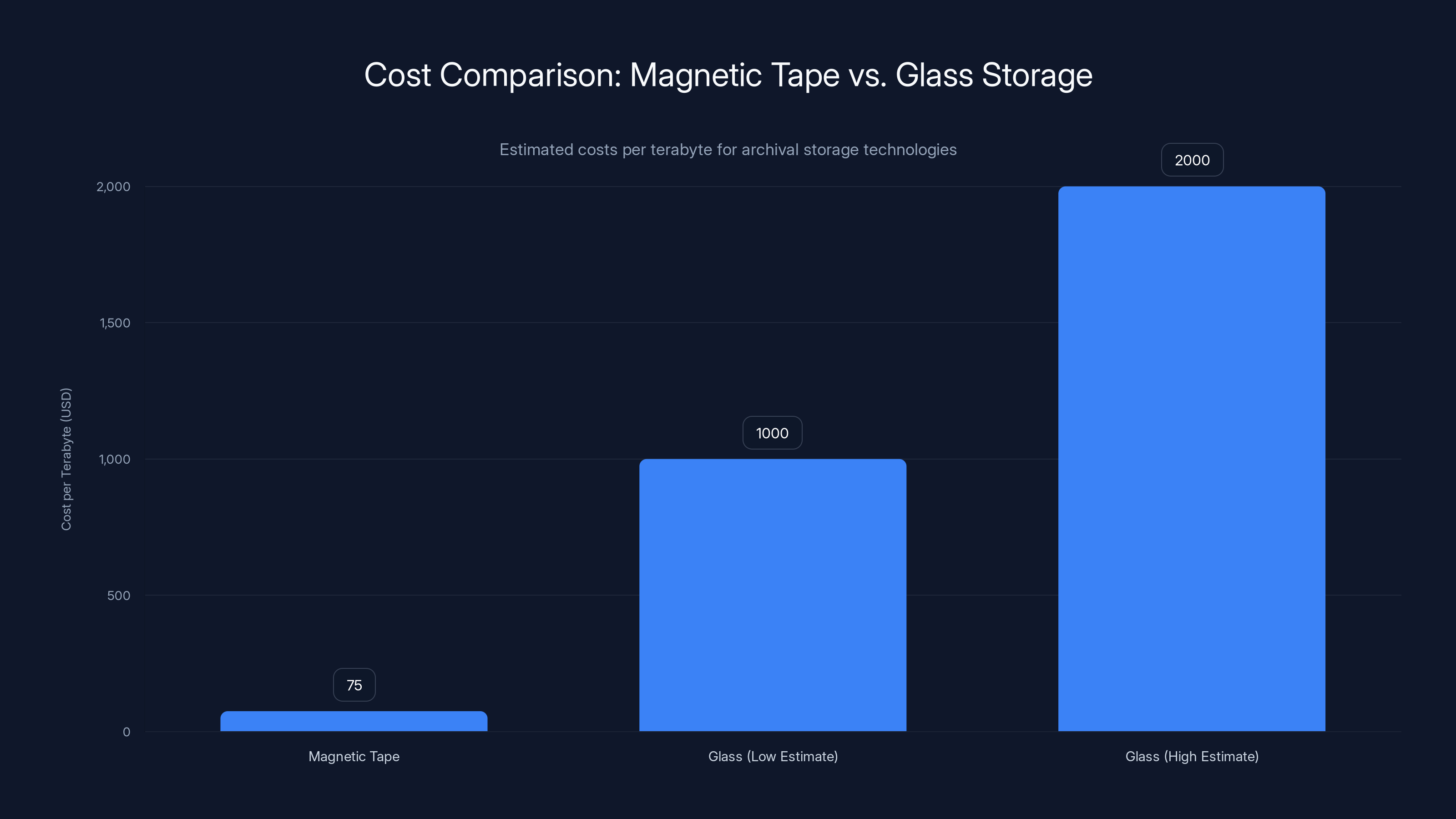

Estimated data shows glass storage is currently 20-40 times more expensive per terabyte than magnetic tape, but could become cost-competitive as manufacturing scales.

Real-World Applications Starting Now

The fascinating thing about Project Silica is that it's not some far-off theoretical research. Microsoft demonstrated it working with real data. They etched map data from Microsoft Flight Simulator onto glass and successfully read it back.

This matters because it means the technology is moving from "interesting research" to "potentially practical." Let's think about where glass storage could actually be deployed starting today or in the next few years.

Government and Legal Records: Governments maintain enormous archives of documents that need to be preserved for centuries. Court records, legislative history, tax documents—all of this currently lives on magnetic tape or in climate-controlled data centers. Glass storage could reduce the infrastructure burden significantly. A single compact box of glass slabs could store the equivalent of multiple tape libraries.

Scientific Data: Research institutions generate massive amounts of data—genomic sequences, astronomical observations, climate measurements. This data needs to be archived and potentially revisited decades later. Glass offers incredible stability for this use case.

Digital Preservation: Libraries and archives are grappling with the problem of preserving digital cultural heritage. Books can last centuries if stored properly, but digital documents on HDDs or SSDs will be corrupted within decades. Glass offers a path to true digital preservation on the scale of centuries.

Corporate Data Retention: Large corporations with regulatory requirements need to retain data for 7 to 10 years or longer. For cold storage—data you write once and rarely access—glass could be cost-effective.

The constraint is clear: glass works best for write-once, read-rarely scenarios. It doesn't make sense for your work computer's primary storage or for your company's daily backups. But for the specific problem of "how do we keep important data safe for 100+ years," glass is genuinely transformative.

The Technical Innovations You Should Know About

Project Silica combines several technical innovations, and understanding them gives you insight into why this approach works better than previous attempts.

Femtosecond Laser Optimization: The researchers didn't just buy off-the-shelf femtosecond lasers. They optimized how they're used. The dual-pulse approach for creating birefringent voxels is clever—the first pulse creates the structure, the second pulse introduces the alignment. This allows extremely precise control over what's being written.

Three-Dimensional Storage Architecture: Most previous attempts at optical storage focused on two-dimensional surfaces. Project Silica enables true three-dimensional storage with multiple layers. This is huge for density. You're using all the volume of the glass, not just the surface.

AI-Driven Reading: Using convolutional neural networks to interpret microscope images is elegant. Rather than fighting optical imperfections, you're embracing them and using machine learning to extract signal from noise. This makes the system more robust to variations in glass quality and microscope imperfections.

Error Correction Implementation: Using low-density parity-check codes isn't new—they're well-established in communications. But applying them thoughtfully to glass storage, where the noise characteristics are different from radio communication, required careful engineering.

Symbol Encoding: The approach of combining neighboring bits into symbols that match each voxel's information capacity is a nice optimization. It ensures you're not wasting any potential storage by trying to store too many bits per voxel or underutilizing capacity by storing too few.

Each of these innovations individually is interesting. Together, they create a system that works better than the sum of its parts.

Glass offers significantly higher data density and lifespan compared to magnetic tape, though it requires more time to write data. Estimated data for magnetic tape density.

Challenges That Remain

Project Silica is a breakthrough, but it's not a complete solution to long-term storage. There are real challenges that remain.

Write Speed Remains a Bottleneck: Even with multiple lasers, glass storage is significantly slower to write than magnetic tape or hard drives. For applications where you're continuously ingesting data, this could be a problem. The 150-hour write time for a full slab seems acceptable for archival, but imagine needing to write 100 slabs of critical data. That's 6,250 hours of laser time. You'd need many laser systems working in parallel, which increases cost.

Reading is Also Slow: The microscope-based reading system is slower than reading magnetic tape or hard drives. Reading the entire 4.84-terabyte slab would take hours. If you need to frequently access specific pieces of data, glass becomes impractical. This limits its application to true archival scenarios where full-slab recovery is acceptable.

Manufacturing Challenges: Project Silica demonstrated that the technology works, but scaling it to industrial production is another question. Femtosecond lasers are expensive. Precision microscopes are expensive. The glass manufacturing process needs to be consistent enough that all slabs have similar optical properties. These are solvable problems, but they're not trivial.

Reader Hardware Availability: Glass storage creates a new dependency: you need access to the right microscope and laser reading system. For truly long-term storage lasting centuries, you're betting that reading hardware will still be available or could be reconstructed. This is less of a problem than format obsolescence for magnetic media, but it's not zero risk.

Cost Analysis: While glass is denser than tape, the cost comparison is unclear. The researchers didn't publish pricing, and the system is still research-grade hardware. For glass to become widely adopted, it needs to achieve cost-per-gigabyte parity with magnetic tape, probably while being better on total cost of ownership when you factor in infrastructure, climate control, and the lower failure rate.

The Future: Where This Technology Is Going

Assuming Project Silica moves from research demonstration to commercial deployment, how might the technology evolve?

Faster Write Times: The team acknowledged that using up to 16 lasers instead of 4 is technically feasible. Beyond that, you could potentially use arrays of hundreds of laser systems writing to different parts of the same slab simultaneously. This could bring write times down from 150 hours to hours or even less.

Higher Density: The current 4.84 terabyte per slab is impressive, but there's room for improvement. Tighter spacing between layers, smaller voxels, more bits per voxel through more sophisticated encoding—all of these could push density higher.

Multiple Reading Methods: Phase contrast microscopy works, but it's not the only option. You could potentially read glass using other techniques like confocal microscopy or even spectroscopic methods. Faster reading technology would make glass more practical for real-time data recovery scenarios.

Easier Instrumentation: As the technology matures, the lasers and microscopes will likely become simpler, cheaper, and more reliable. Rather than requiring laboratory-grade equipment, reading systems might become compact and more like how we've miniaturized other technologies.

Hybrid Approaches: You might see glass used as one layer in a hybrid storage system. Write data quickly to a regular hard drive or SSD, then migrate cold data to glass for long-term archival. This combines the speed of conventional storage with the longevity of glass.

Material Optimization: The researchers showed it works with borosilicate glass, but custom glass formulations could be developed for even better stability or easier reading. You might see glasses optimized for specific temperatures or humidity conditions.

The most likely near-term scenario is that Project Silica becomes a commercial product aimed at the high-end archival market. Large enterprises, governments, and research institutions with massive data preservation needs would be early adopters. As costs decrease and infrastructure matures, it might eventually become the default solution for long-term storage.

This chart compares storage technologies across durability, cost, and speed. HDDs and SSDs offer faster speeds but have shorter lifespans compared to magnetic tape. DNA storage, while durable, is currently impractical due to high costs and slow speeds. Estimated data.

Implications for Data Preservation Philosophy

Project Silica represents something deeper than just a new storage technology. It's a shift in how we think about data preservation.

For decades, the dominant model has been "active preservation." You stored data and actively managed it—regularly copying it to new media, updating file formats, maintaining hardware, replacing drives as they failed. This is expensive and requires constant attention, but it was necessary because storage media degraded.

Glass storage enables a different model: "passive preservation." You write data once and let it sit. No power consumption, no active management, no regular migrations. As long as you store it in decent conditions and don't physically damage it, the data remains readable for centuries.

This is philosophically significant. It means we can think about digital preservation the way we think about physical archives. Archivists store documents in acid-free paper in climate-controlled vaults because they expect them to last centuries with minimal intervention. Glass storage enables the same mindset for digital data.

There are implications for data policy and information governance. If data truly lasts forever and doesn't degrade, questions about how long to retain data become even more important. Privacy advocates worry about digital data being preserved indefinitely. Copyright holders worry about data being preserved longer than copyright terms. These aren't new concerns, but glass storage makes them more acute because the default is now "data lasts forever," not "data lasts until the hardware fails."

Economic Considerations

For any new storage technology to achieve widespread adoption, the economics have to work.

Magnetic tape, currently the standard for archival, costs roughly $50-100 per terabyte once you factor in the cost of the media, the drive hardware, and the infrastructure. But glass hasn't been manufactured at scale yet, so it's hard to know what the true cost would be.

Let's do some rough estimates. If a glass slab can store 4.84 terabytes and costs

The break-even point depends on the actual manufacturing cost and the operational costs of tape-based archival. If glass can be manufactured for $5,000-10,000 per slab, it could be cost-competitive with tape within a few years. If manufacturing costs are much higher, adoption will be slower.

What's clear is that this is a premium product for organizations that can afford it. The National Archives, major research universities, large corporations with regulatory requirements, tech companies with massive data preservation needs—these are the early adopters. Eventually, as manufacturing scales and costs decrease, it might become mainstream.

Comparing to Other Emerging Storage Technologies

Glass isn't the only technology being explored for long-term storage. It's useful to understand how it compares to alternatives.

DNA Storage: As mentioned earlier, DNA has incredible density and stability, but the technology is expensive and slow. Microsoft itself has invested in DNA storage research. In the long term, DNA might be complementary to glass—you might use glass for terabyte-scale data and DNA for petabyte-scale storage. But DNA isn't ready for practical deployment yet.

Holographic Storage: Holographic storage uses three-dimensional holograms to store data. The technology can theoretically store terabytes on a disc, but it's had persistent challenges with read/write reliability and hasn't achieved commercial viability despite 20+ years of research.

Molecular Tape: Some researchers are exploring molecular-level encoding, but this remains speculative and far from practical.

Atomic-Scale Storage: IBM has demonstrated single-atom storage using scanning tunneling microscopes, but again, this is many years away from practical application.

Glass storage is interesting because it's based on well-understood physics and materials science. It's not waiting for breakthroughs in exotic materials or techniques. The innovation is in combining existing techniques—femtosecond lasers, phase contrast microscopy, error correction codes, neural networks—in a novel way. This makes it more likely to transition from research to commercial reality.

Implementation Considerations for Organizations

If you're an organization considering glass storage, here are the key questions to ask.

Do you have data that truly needs to be preserved for centuries? If your retention requirements are 7-10 years, glass is overkill. Magnetic tape is fine. But if you have cultural heritage data, scientific datasets, or regulatory records that need multi-century preservation, glass makes sense.

Can you afford the upfront cost? Glass storage will be expensive initially. Early adopters will pay a premium. If you're price-sensitive, wait a few years for costs to come down.

Do you need frequent access to the data? If your archival data needs to be accessed regularly or quickly, glass is not ideal. You'd want to use glass for cold storage—data that's accessed rarely if ever.

Can you manage the infrastructure? Even though glass is passive, you still need to store it properly, maintain an inventory, and have a plan for how to read it in the future. This isn't zero infrastructure cost.

What's your read-access pattern? If you need specific files from a large archive, having to read an entire 4.84-terabyte slab is inconvenient. If you typically access data in bulk ("recover the entire 2023 dataset"), glass works better.

The Path to Commercialization

Project Silica is currently a research project at Microsoft Research. The question everyone in the archival and data management space is asking is: when does this become a commercial product?

Based on the maturity level of the research, a realistic timeline might look like this.

2025-2026: Initial demonstrations and publications continue. Early interest from enterprises. Microsoft likely partners with vendors to commercialize components (especially the laser and microscopy systems).

2027-2028: Beta access for early adopters. First commercial glass-based archival products appear. Pricing is high, but early data on cost-per-gigabyte and reliability accumulates.

2029-2030: Broader commercial availability. Manufacturing scales. Prices decrease. Second-wave adoption by large enterprises and research institutions.

2031+: Glass storage becomes standard for long-term archival. Prices reach competitive parity with magnetic tape. Becomes the default choice for any organization needing multi-decade or multi-century preservation.

This is speculative, but it's based on how other storage technologies have typically been commercialized. Research to product usually takes 3-7 years once the core technology works, which Project Silica clearly does.

Lessons for Long-Term Data Strategy

Whether or not you adopt glass storage specifically, Project Silica teaches important lessons about how to think about long-term data preservation.

Stability matters more than speed: In archival contexts, the properties that matter are durability, longevity, and reliability. Speed is secondary. This is opposite to how we usually design storage systems.

Format independence is critical: Any truly long-term storage system needs to be format-independent. Whatever hardware reads the data, it should be independent of specific proprietary formats. Glass's use of standard optical microscopy (rather than proprietary hardware) is important for this reason.

Density enables economics: Higher storage density reduces space and infrastructure costs. This matters over decades because your storage facility costs scale with how much stuff you're storing.

Plan for infrastructure evolution: No matter what technology you choose, assume that the infrastructure supporting it will need to be rebuilt every 20-30 years. Build systems with this in mind.

Redundancy is still important: Even with glass storage's incredible stability, redundancy across multiple slabs and possibly multiple locations is wise.

These principles apply whether you use glass, tape, DNA, or something else entirely. They're fundamentals of good data preservation strategy.

The Bottom Line

Project Silica is genuinely significant. It's not revolutionary in the sense that it invents entirely new physics. Instead, it takes well-understood technologies—femtosecond lasers, optical microscopy, error correction codes, neural networks—and combines them in a smart way to solve a real problem.

The problem it solves is real and growing. We're creating more data than ever, and we need ways to preserve the important stuff for centuries. Existing solutions (tape, hard drives, SSDs) all have limitations. Glass storage offers something genuinely different: high density, incredible stability, and no ongoing power or maintenance requirements.

Will glass storage become ubiquitous? Probably not for every use case. It's too slow to write for real-time applications, and the infrastructure isn't yet mature. But for the specific problem of long-term archival storage, it's a game-changer.

In 50 years, when we look back at 2026, Project Silica might be remembered as a watershed moment in how we think about data preservation. It's the point where we stopped depending on actively managed hardware and started building systems for true digital permanence.

FAQ

What exactly is Project Silica?

Project Silica is Microsoft Research's working demonstration of a data storage system that uses femtosecond lasers to etch data into small slabs of glass. The system can write and read data at a density of over 150 megabytes per cubic millimeter, allowing a single 12x 12-centimeter glass slab to store up to 4.84 terabytes of data. It's designed for long-term archival storage, with the glass remaining readable for 10,000+ years without active maintenance or power consumption.

How does the laser write data into glass?

Femtosecond lasers emit extremely short pulses of light lasting 10^-15 seconds. These pulses focus energy into tiny volumes within the glass, creating structural changes at scales smaller than the diffraction limit of visible light. The researchers use two different encoding methods: one creates oriented void structures with birefringence (polarization-dependent refraction), while the other varies the magnitude of refractive effects by adjusting laser power. Both approaches allow multiple bits of data to be stored in each voxel (three-dimensional storage unit).

What makes glass better than magnetic tape for archival storage?

Glass is chemically and thermally stable for thousands of years without degradation, while magnetic tape typically lasts 30-50 years. Glass requires no active maintenance, electricity, or climate control to preserve data indefinitely. It's also denser than tape by an order of magnitude. The main trade-offs are that glass is slower to write (150 hours for a full slab) and slower to read, but for archival scenarios where data is written once and accessed rarely, these trade-offs are acceptable.

How does the system read data back from glass?

The system uses phase contrast microscopy, an optical technique that reveals differences in refractive index. The microscope automatically positions itself at specific points on the glass using alignment markers that were etched during writing. It then moves through layers of data, capturing microscope images. A convolutional neural network interprets these images, using information about how neighboring voxels affect the appearance of each voxel to accurately extract the stored data despite optical imperfections.

When will glass storage be commercially available?

Project Silica is currently a research demonstration announced in February 2026. Based on typical technology commercialization timelines, beta products might appear in 2027-2028, with broader commercial availability by 2029-2030. Initial pricing will be high, targeting large enterprises and research institutions with long-term archival needs. Costs will likely decrease significantly as manufacturing scales, potentially achieving price parity with magnetic tape by the early 2030s.

What organizations would benefit most from glass storage?

Organizations with long-term data preservation needs are ideal early adopters: government institutions (National Archives, legislative records), scientific research facilities (genomic databases, astronomical data), cultural heritage organizations (digital libraries, museums), large corporations with regulatory requirements (financial institutions, healthcare systems), and major technology companies with massive data archival responsibilities. The technology is best suited for write-once, read-rarely scenarios rather than frequently accessed data.

How do the two different encoding methods compare?

The birefringence-based method creates oriented void structures and requires polarized laser pulses. It achieves higher density (4.84 terabytes per slab) but requires higher-quality glass and more sophisticated optical hardware. The energy-variation method adjusts laser power to create different refractive magnitudes, works with any transparent material including standard borosilicate glass, and uses simpler hardware. However, it stores roughly half the data (just over 2 terabytes per slab). The choice depends on whether you prioritize maximum density or hardware simplicity.

What are the main limitations of glass storage?

Write speeds remain slow at 66 megabits per second even with multiple lasers, meaning it takes 150 hours to fully populate a slab. Reading is also slow, requiring microscopic scanning through multiple layers. The technology requires expensive femtosecond laser and precision microscopy equipment, which must be maintained and eventually replaced. Glass storage is impractical for frequently accessed data or real-time backups. Finally, manufacturing at commercial scale hasn't been proven yet, and costs remain unknown.

How dense is glass storage compared to alternatives?

Glass storage achieves over 150 megabytes per cubic millimeter, which is roughly 10-20 times denser than magnetic tape (which stores about 10-15 megabytes per cubic millimeter). In practical terms, a glass slab the size of your palm can store what would require multiple tape libraries to preserve. This density advantage is crucial for the economics of long-term archival, as it reduces physical storage space, facility costs, and infrastructure overhead across the decades or centuries of preservation.

What error correction approach does Project Silica use?

The system uses low-density parity-check codes, the same error correction technology used in 5G networks. This is necessary because reading data from glass involves inherent optical noise, interference between layers, and imperfections in the voxel creation process. The error correction codes allow the system to reliably recover data despite these imperfections. Additionally, neighboring bits are combined into symbols that match each voxel's information capacity, optimizing data density while maintaining reliability.

Could glass storage replace hard drives or SSDs for regular computing?

No. Glass storage's slow write speeds (150+ hours for a full slab) and slow read times (hours to access an entire slab) make it impractical for any application requiring regular or quick access to data. It's specifically designed for archival scenarios where data is preserved long-term without frequent use. For everyday computing, hard drives and SSDs remain the appropriate technologies. Glass storage is complementary to existing storage technologies, not a replacement.

Key Takeaways

-

Microsoft's Project Silica uses femtosecond lasers to etch data into glass at unprecedented density (150+ megabytes per cubic millimeter), enabling a single 12x 12-centimeter slab to store up to 4.84 terabytes of data.

-

Glass storage solves the archival problem by offering 10,000+ year lifespan without power, maintenance, or active infrastructure, fundamentally shifting data preservation from an expensive active-management problem to a passive-storage solution.

-

The technology combines established techniques in novel ways: femtosecond laser writing, phase contrast microscopy for reading, low-density parity-check error correction, and neural networks to interpret microscope images through optical noise.

-

Write speeds remain slow (150 hours per full slab), making glass impractical for real-time data or frequently accessed information, but acceptable for archival scenarios where data is stored once and accessed rarely.

-

Commercial availability likely within 3-5 years, with early adoption by large enterprises, government institutions, and research facilities with long-term archival needs, followed by broader adoption as manufacturing scales and costs decrease.

Related Articles

- Project Silica: Glass Data Storage for 10,000 Years [2025]

- Holographic Tape Storage Finally Meets Real-World Deployments in 2025 [2025]

- Metal Gear Solid 4 Leaves PS3: Console Exclusivity Death [2025]

- Paza: Speech Recognition for Low-Resource Languages [2025]

- Wayback Machine Link Fixer Plugin: Fixing Internet's Broken Links [2025]

- Adobe Reverses Animate Discontinuation: What It Means [2025]

![Microsoft's Revolutionary 10,000-Year Glass Data Storage [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-revolutionary-10-000-year-glass-data-storage-202/image-1-1771443607590.jpg)