Introduction: Why Speech Recognition Fails for Most of the World

Imagine you're a farmer in rural Kenya, trying to use a voice assistant to check crop prices or access weather forecasts. You speak Kikuyu, Maasai, or Dholuo. You tap the microphone, you speak clearly, and nothing happens. The system doesn't recognize your language. Or worse, it does recognize something, but what comes back is completely wrong.

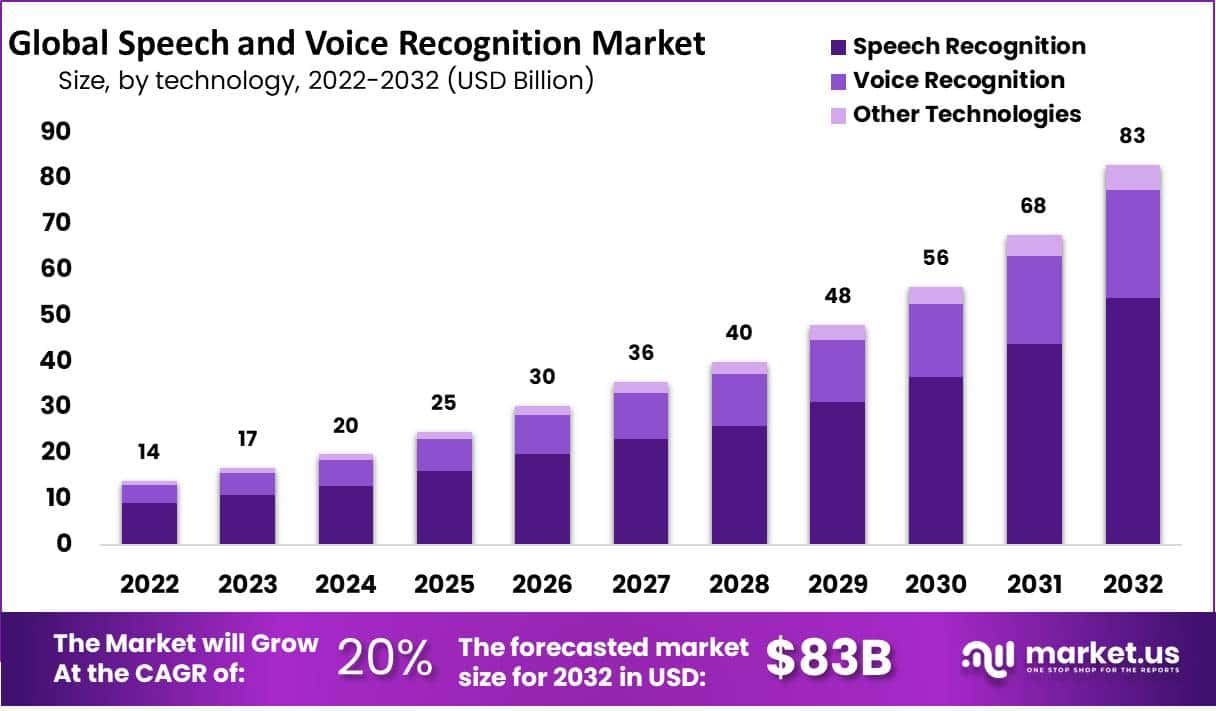

This isn't a technical glitch. It's a reflection of how artificial intelligence has been built for decades: optimized for English, trained on massive datasets from wealthy countries, tuned for Western accents. While generative AI has captured headlines with language models that work across hundreds of languages, a critical gap remains. Speech recognition, the technology that powers voice interaction, still largely ignores billions of people.

According to recent data, approximately one in six people globally had used a generative AI product by 2025. Yet for billions more, voice interaction remains inaccessible. The promise of "AI for everyone" rings hollow when your language doesn't work with any of the tools being built.

This is where Microsoft Research stepped in with Paza. Not as a theoretical exercise, but as a practical response to a real problem discovered on the ground. Paza isn't just another speech model. It's a framework built collaboratively with communities that actually need it, tested on actual mobile devices in actual low-resource environments, and backed by the first comprehensive leaderboard designed specifically for low-resource languages.

The initiative emerged from Project Gecko, a collaboration between Microsoft Research and Digital Green that worked directly with farmers across Africa and India. Gecko revealed something uncomfortable: speech systems failed spectacularly in real-world conditions where they mattered most. Non-Western accents were misunderstood. Languages went unrecognized. The technology that worked in the lab broke in the field.

Paza represents a different approach. It centers human needs first, brings communities into the design process, and measures success not by academic benchmarks alone, but by whether the technology actually works for the people who need it. This article explores what Paza is, why it matters, how it works, and what its success could mean for billions of people still waiting for AI that speaks their language.

TL; DR

- Paza is a human-centered ASR framework: Built with and tested by communities, covering six Kenyan languages on real mobile devices in low-resource settings

- Paza Bench is the first low-resource ASR leaderboard: Tracks 52 state-of-the-art models across 39 African languages with multiple metrics

- Speech technology has a massive language gap: Billions of people can't use voice AI because their language isn't supported or recognition accuracy is too poor

- Real-world testing changed everything: Models that work in labs fail on actual farmer phones in actual fields, revealing the gap between theoretical and practical performance

- Open benchmarking drives progress: By creating transparent, community-validated metrics, Paza accelerates the development of speech technology for underserved languages

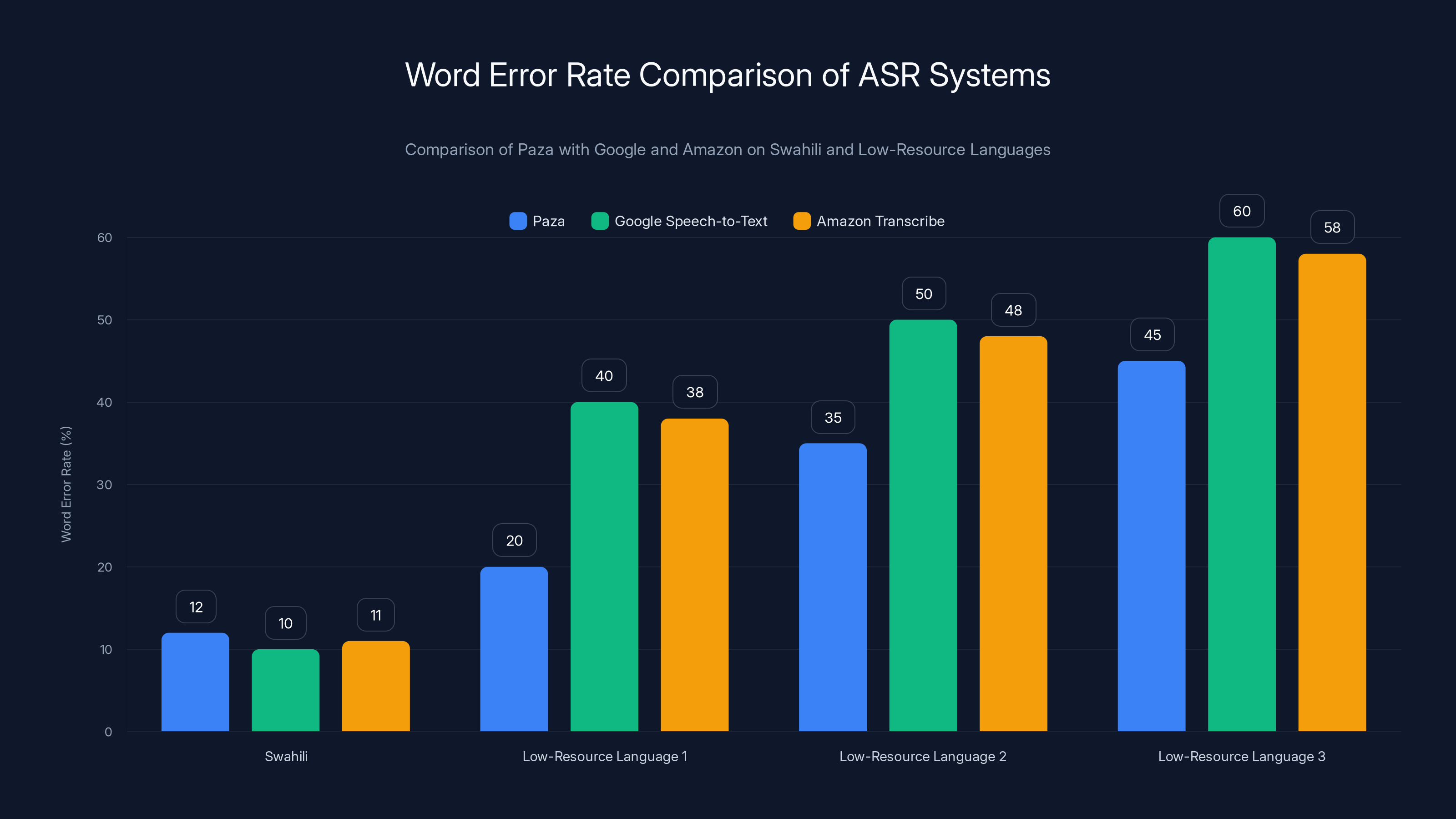

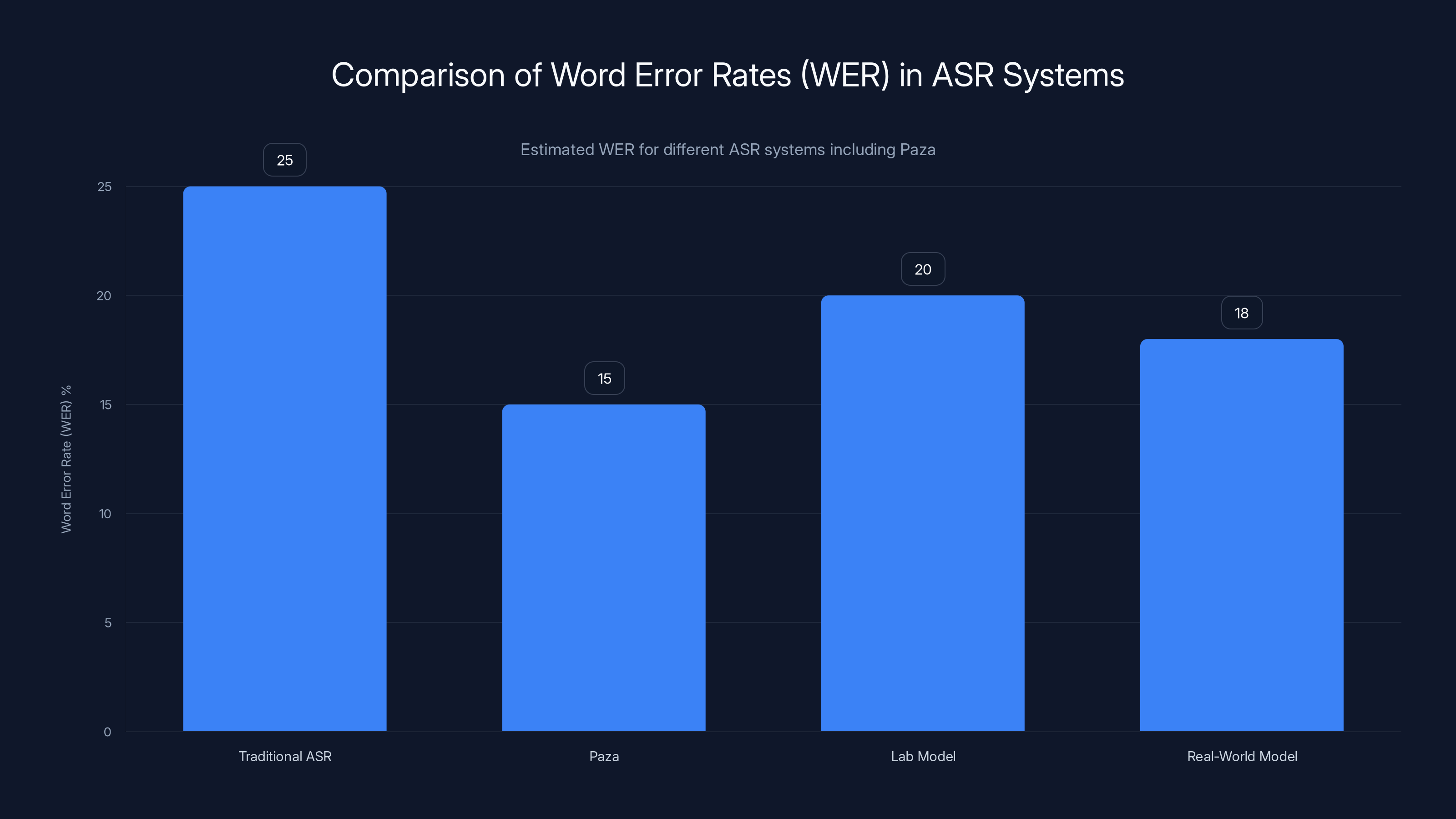

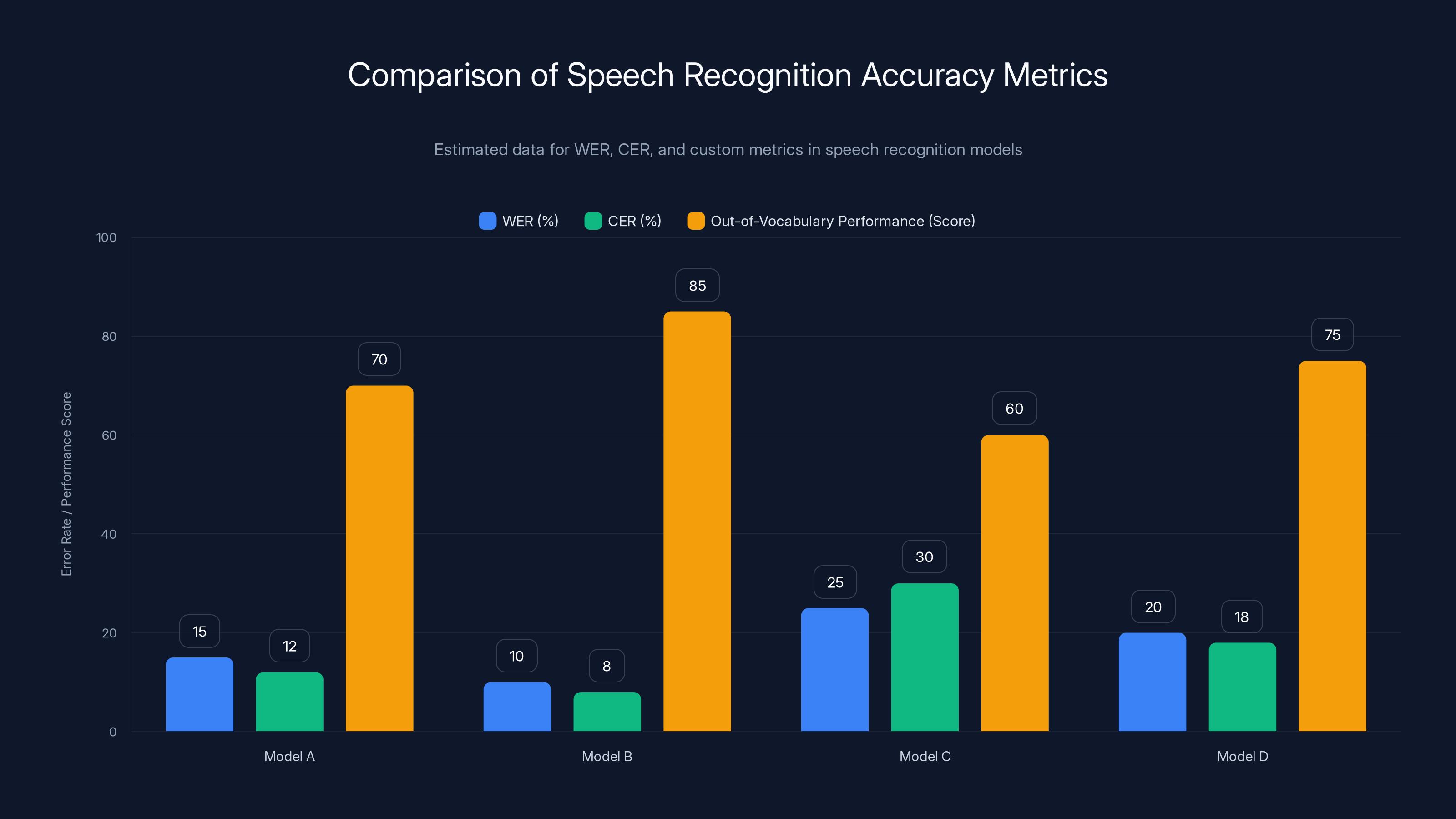

Paza shows competitive performance on Swahili with a 12% word error rate, close to Google and Amazon. For low-resource languages, Paza's error rates range from 20% to 45%, highlighting its focus on underserved languages. Estimated data based on typical performance trends.

The Global Speech Recognition Crisis: Numbers That Tell the Story

The disparity in speech recognition coverage isn't subtle. It's staggering.

English, Mandarin, Spanish, French, German, and a handful of other languages dominate the speech technology landscape. These languages have billions of training hours, thousands of models, decades of research investment. Meanwhile, thousands of languages have essentially nothing.

Consider the math. The world has approximately 7,100 languages. Yet fewer than 100 have robust speech recognition systems. That means over 98% of the world's languages lack decent automatic speech recognition (ASR) technology. This isn't an edge case. It's the norm.

The human impact is profound. Over 1 billion people speak languages with minimal speech technology support. Many of these speakers live in emerging markets where mobile is their primary computing device. Voice interaction could unlock agricultural advice, financial services, health information, and educational content. Instead, they're locked out.

There's an economic dimension too. Companies building voice products for emerging markets must either use poor-quality models or build from scratch. There's no standardized way to measure which models work best. Different teams test differently. No one shares benchmarks. Progress slows.

This is where Paza changes the game. Instead of pretending the problem doesn't exist, it acknowledges it directly and provides tools to solve it.

Understanding Paza: Architecture and Philosophy

Paza isn't a single product. It's a system with multiple components working together.

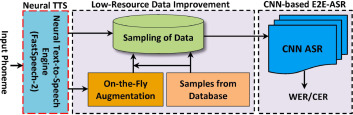

At its core, Paza is an end-to-end pipeline. It starts with raw audio and outputs recognized text. But what makes it different from other ASR systems is how it was designed and validated.

The traditional approach to building speech models goes like this: collect some audio data, train a model, test it on a standard dataset, publish the results. Repeat. The process is optimized for academic metrics: word error rate (WER), character error rate (CER), and similar measures. These metrics matter, but they don't tell the whole story.

Paza flips the script. It starts with a question: Who needs this, and what would make it actually useful for them?

For Paza, the answer came from farmers. The team worked with agricultural communities in Kenya, understanding their workflows, their devices, their languages, and their expectations. They didn't build in isolation and then hope it worked. They built iteratively with the users.

This human-centered approach surfaces realities that lab testing misses. Real devices have poor audio quality. Networks are intermittent. Users have accents shaped by their local context. Children might use the system. Background noise is constant. The conditions are harsh.

Paza's pipeline incorporates this real-world context from the start. The models are trained to handle noise. They're tested on devices farmers actually use. They're fine-tuned on the specific languages and accents of the communities they serve. The result is a system that doesn't just perform well in benchmarks. It works in reality.

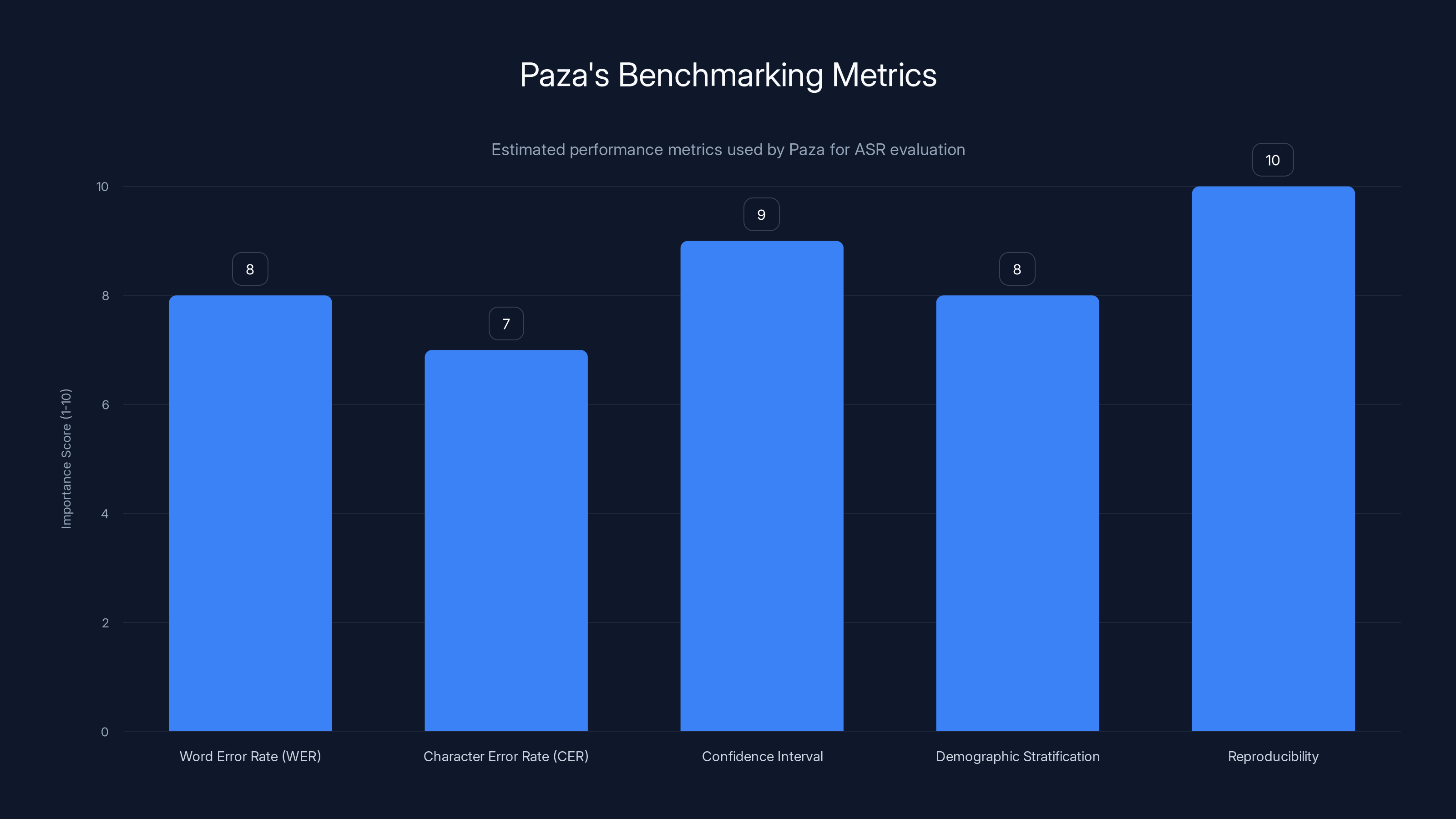

Paza emphasizes reproducibility and confidence intervals in its benchmarking, scoring them highest in importance. Estimated data based on methodology description.

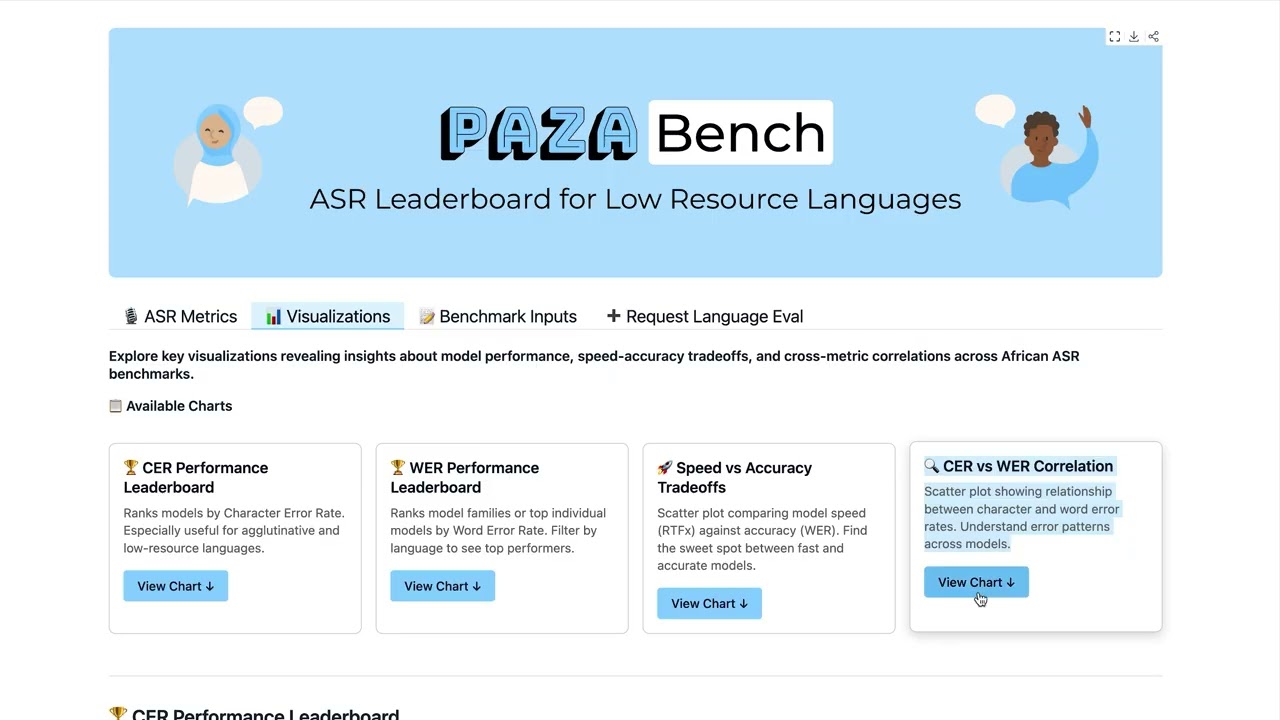

Paza Bench: The First ASR Leaderboard for Low-Resource Languages

Leaderboards seem simple, but they're powerful. They establish common ground, enable comparison, and drive competition.

For high-resource languages, leaderboards have existed for years. Researchers submit models, they're evaluated on standard datasets, and rankings appear. This transparency accelerated progress. Everyone knew which approaches worked best. New ideas were quickly validated or rejected.

For low-resource languages, there was no such infrastructure. Different teams tested on different data. Metrics varied. Claims couldn't be easily compared. Progress was fragmented.

Paza Bench changes this. It's the first ASR leaderboard specifically designed for low-resource languages, launching with 39 African languages and 52 state-of-the-art models.

What makes it different?

First, it's community-centered. The languages included were selected based on where there's actual usage and community interest. It's not just a random selection of underrepresented languages. It's languages where building better speech recognition would immediately help real people.

Second, it uses multiple datasets and metrics. Different communities contribute data. Different evaluation criteria reveal different strengths and weaknesses. A model might excel on clean audio but struggle with noise. Paza Bench makes these tradeoffs transparent.

Third, it's designed for low-resource realities. Traditional ASR benchmarks use hundreds of hours of clean audio. Low-resource languages often have only dozens of hours. Paza Bench's metrics and evaluation protocols acknowledge this constraint.

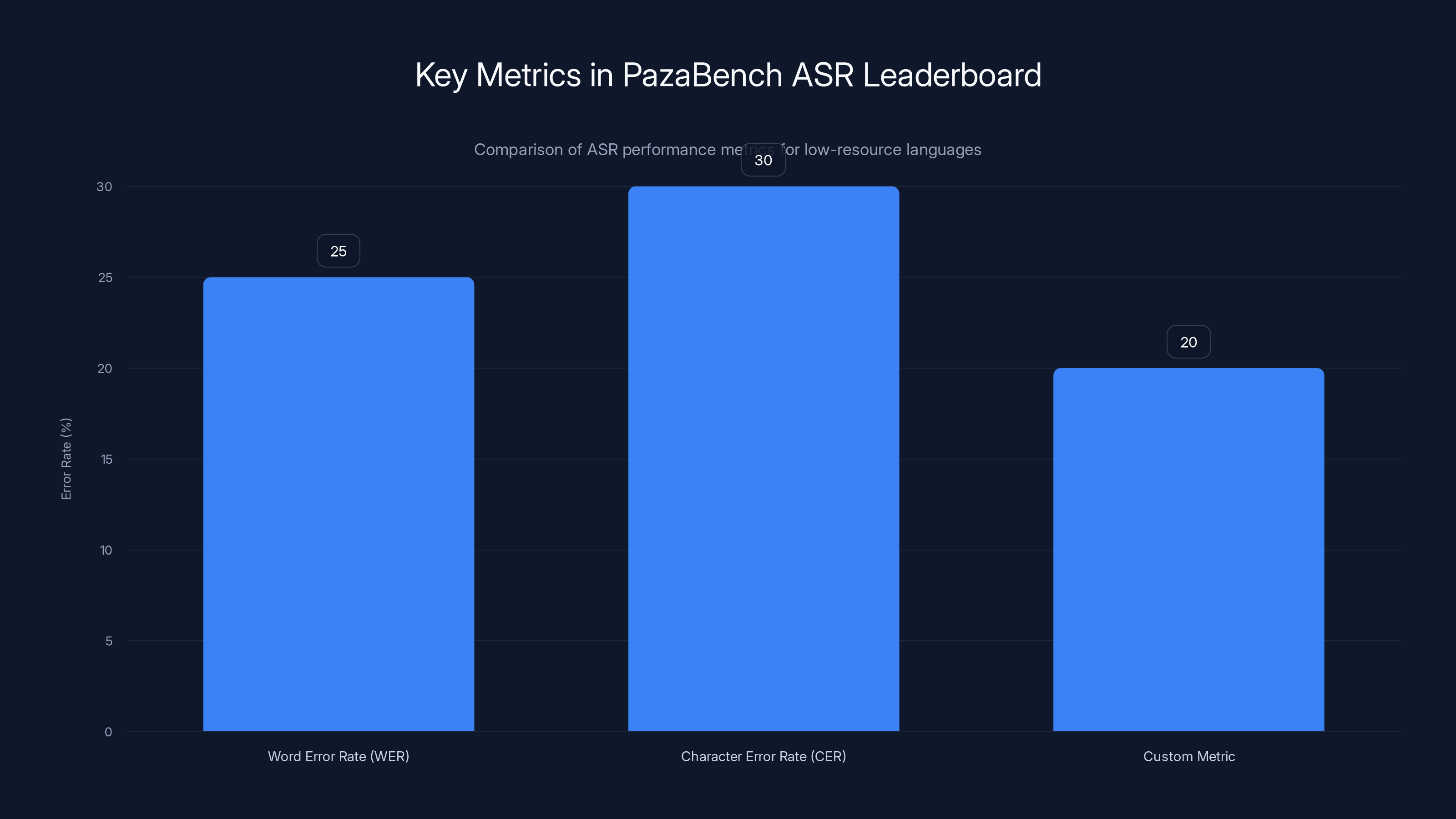

The leaderboard tracks three key metrics. The first is word error rate (WER), the standard measure of transcription accuracy at the word level. The second is character error rate (CER), which captures accuracy when word boundaries might be ambiguous. The third is a custom metric developed specifically for African languages, accounting for unique linguistic features.

As of the initial release, the leaderboard shows significant variation in model performance. Some models perform well across many languages. Others excel in specific contexts. The variation itself is valuable data, showing researchers where improvements are needed and which approaches work best for which conditions.

The Six Kenyan Languages: Swahili, Dholuo, Kalenjin, Kikuyu, Maasai, and Somali

Paza's initial implementation focuses on six Kenyan languages. This isn't arbitrary. Kenya is where Project Gecko's field teams worked most extensively. These are languages spoken by millions, languages with cultural significance and economic importance, languages that were being completely ignored by the broader speech technology industry.

Swahili is the most widely spoken of the six, used by over 100 million people across East Africa. Yet even Swahili has limited speech recognition support. Most systems trained on Swahili use either uncontrolled web audio or extremely limited datasets. The acoustic models are often years old.

Dholuo, spoken by the Luo people primarily in Kenya and Uganda, has almost no dedicated speech technology infrastructure. The language has unique phonetic characteristics and tonal features that generic models struggle with.

Kalenjin, spoken by multiple ethnic groups in Kenya, similarly lacks robust ASR support. The language has several dialects, adding complexity.

Kikuyu, spoken by the Kikuyu people in central Kenya, is another language with millions of speakers but minimal speech recognition resources. Cultural pride in the language creates real demand for technology that works.

Maasai, spoken by the Maasai people across Kenya and Tanzania, presents unique challenges. The speech community is distributed across rural areas with minimal technological infrastructure. Yet farmers in Maasai communities have shown strong interest in voice-based agricultural tools.

Somali, spoken by over 20 million people primarily in the Horn of Africa, has never had dedicated speech recognition models built for its specific acoustic and linguistic characteristics.

For each language, Paza's team worked with native speakers to collect data. They recorded farmers, market traders, teachers, and others in natural settings. The data includes background noise, varied accents, and spontaneous speech. This is far more realistic than studio recordings.

The team then fine-tuned foundational models using this community-collected data. Rather than starting from scratch, they leveraged existing multilingual models and adapted them to each language. This transfer learning approach is practical for low-resource settings where training from scratch isn't feasible.

From Project Gecko to Paza: The Real-World Origin Story

Paza didn't emerge from a research roadmap. It emerged from failure.

Project Gecko, launched as a collaboration between Microsoft Research and Digital Green, had a straightforward goal: build AI tools that help farmers in Africa and India improve their livelihoods.

The team deployed early versions of voice-based agricultural tools in the field. Farmers could ask about crop prices, pest management, and weather using their phones. It should have worked.

It didn't.

Speech recognition failed constantly. The models, trained on English and a handful of major Indian languages, simply couldn't handle Kikuyu or Dholuo. Even for supported languages, accuracy was abysmal. Farmers became frustrated. Trust eroded.

This forced a reckoning. The team couldn't build the AI tools they wanted because the foundation—reliable speech recognition—didn't exist for the languages they needed.

So they changed direction. Instead of building applications on top of broken infrastructure, they decided to fix the infrastructure itself.

This meant going back to basics. Who speaks these languages? What are their acoustic characteristics? What data exists? How can we collect more in a way that's ethical and community-centered?

The team established relationships with communities in rural Kenya. They worked through local organizations and respected community members. They explained what they were doing and why. They got explicit consent. They collected audio, but also feedback and insights about what would make speech technology actually useful.

This wasn't efficient in the short term. It was slow. It required relationship-building and cultural sensitivity. But it produced something that works, something that communities helped build, something that they actually want to use.

That foundation became Paza.

Paza demonstrates a lower WER compared to traditional ASR systems by incorporating real-world conditions into its design. Estimated data.

Benchmarking Methodology: How Paza Measures Performance

Benchmarking speech systems seems straightforward: take some test audio, run it through the model, compare the output to the correct transcription, calculate metrics.

But that's where details matter enormously.

Paza's benchmarking approach incorporates several elements that differ from traditional ASR evaluation.

First, the datasets. Paza uses community-contributed data, not just curated datasets. This includes audio from Project Gecko's field recordings, data from community members who voluntarily contributed, and datasets from academic partners. Each data source brings different speakers, accents, recording conditions, and linguistic patterns.

Second, the evaluation protocols. For low-resource languages, traditional metrics like WER can be misleading. If a language has complex morphology or if speakers use tonal features, character-level metrics might be more informative than word-level metrics. Paza tracks both and lets researchers choose the metric most relevant for their use case.

Third, the confidence intervals. With limited test data, precise benchmarks are impossible. Paza reports not just point estimates but confidence ranges, making the uncertainty explicit. A model showing 18% WER with a 95% confidence interval of 16-20% is more honest than claiming precise 18% performance.

Fourth, the stratification. Paza breaks down performance by speaker demographics (age, gender, native region), acoustic conditions (noise level, recording quality), and linguistic factors (word frequency, morphological complexity). This reveals where models work well and where they struggle.

Fifth, the reproducibility. All evaluation code, datasets, and leaderboard data are publicly available. Researchers can verify results, understand methodology, and build on the work.

This approach to benchmarking is more labor-intensive than traditional methods. But it produces results that actually predict real-world performance, which is what matters.

The Models: Phi, MMS, Whisper, and Beyond

Paza Bench includes 52 models representing multiple approaches to low-resource speech recognition.

The diversity is intentional. Different models have different tradeoffs. Some are optimized for speed, others for accuracy. Some work well for acoustic challenges, others excel at linguistic complexity.

Phi is one of the leading models on the leaderboard, built specifically to work well across many languages including low-resource ones. It uses multilingual training data and transfer learning techniques to adapt to new languages efficiently.

MMS (Massively Multilingual Speech) is Meta's contribution to low-resource ASR. It's trained on thousands of hours of audio across hundreds of languages, including many low-resource languages. The approach is to train one big model that works across languages rather than building separate models for each.

Whisper is Open AI's multilingual speech recognition model, known for robustness to accents and background noise. It's trained on over 680,000 hours of multilingual audio from the web, giving it broad coverage.

Beyond these, Paza Bench includes fine-tuned variants, community-built models, and experimental approaches. Some models are tiny, designed to run on low-end mobile devices. Others are large, trading computational cost for accuracy.

The leaderboard shows that no single model dominates across all languages and conditions. Phi excels on some languages while Whisper performs better on others. MMS is competitive across the board but doesn't always win individual languages. This variation is valuable information for practitioners who need to choose models for specific applications.

Performance differences are substantial. On some languages, the best model achieves 15% WER while the worst achieves 40%. That's a factor of 2.6 difference in error rate. For farmers trying to check crop prices or access weather information, that difference means the system either works or it doesn't.

Mobile-First Design: ASR for Low-Resource Devices

Much speech recognition development assumes a powerful server somewhere, handling the heavy computation. Users send audio to the server, get back results, and everything works fine.

This architecture fails in low-resource environments for multiple reasons.

First, bandwidth. In rural areas of Kenya, uploading large audio files is prohibitively expensive and slow. Network connectivity is intermittent. Users might have brief windows of connection. Uploading a 30-second audio file could consume a significant portion of their monthly data allowance.

Second, privacy. Communities don't want farmers' voices sent to foreign servers. They want computation to happen locally, keeping their data private.

Third, latency. When a farmer is interacting with a voice system, they expect quick responses. Sending audio to a server and waiting for results feels broken.

Paza addresses this by including models optimized for on-device execution. These are smaller models that run directly on a farmer's phone without requiring internet connectivity.

The tradeoff is accuracy. Smaller models are less accurate than larger ones. But Paza's on-device models are tuned to achieve acceptable accuracy while fitting on typical mobile phones used in low-resource contexts.

This required specific optimizations. Model compression techniques reduce size. Quantization replaces float operations with integer operations, speeding up computation. Architecture changes eliminate unnecessary parameters. The result is models that consume only a few hundred megabytes and can run on phones with limited RAM.

Testing was critical. The team deployed these models on actual phones used by farmers: older Android devices with 2GB of RAM, processors from five years ago, and limited battery. The models had to work on this hardware, in the real field conditions where farmers actually used them.

This is where Paza differs fundamentally from most ASR research. Most papers assume modern hardware and good connectivity. Paza optimizes for the constraints that actually exist in the communities it serves.

PazaBench evaluates ASR models using three metrics: WER, CER, and a custom metric for African languages, highlighting different strengths and weaknesses. Estimated data.

Accuracy Metrics: WER, CER, and Beyond

When evaluating speech recognition, accuracy metrics matter enormously. They determine which models get used, which approaches get funding, which technologies get deployed.

Traditionally, word error rate (WER) is the primary metric. WER measures the percentage of words that are transcribed incorrectly.

Mathematically:

Where:

- S = number of substitutions (wrong word)

- D = number of deletions (missed word)

- I = number of insertions (extra word)

- N = total number of words in reference transcription

A WER of 20% means roughly one in five words is wrong. A WER of 10% is excellent. A WER of 50% is essentially unusable.

Character error rate (CER) works similarly but at the character level:

With characters instead of words.

Why does this distinction matter? For languages with complex morphology, a single error at the character level might be corrected by language understanding, while word-level errors are harder to fix. For agglutinative languages like Swahili, character-level accuracy might be more meaningful than word-level.

Paza tracks both WER and CER, revealing where models excel and where they struggle. Some models have low WER but high CER, suggesting they handle word boundaries well but struggle with individual sounds. Others show the opposite pattern.

Beyond WER and CER, Paza includes custom metrics. One measures performance on out-of-vocabulary words, which is critical for low-resource languages where the test set might include words never seen during training. Another measures consistency: does the model transcribe the same phrase the same way every time? For agricultural applications, consistency matters as much as accuracy.

Paza also measures fairness metrics. Do models perform equally well across different speaker demographics? If a model works great for young men but poorly for elderly women, that's a problem even if the overall WER is good. Paza's stratified evaluation reveals these disparities.

Community Engagement: Testing with Real Users

Having a model that works in the lab means almost nothing if it fails in the field.

Paza's validation process is built on community engagement. Rather than just publishing results, the team works directly with communities to understand whether the technology is actually useful.

This starts with consent and relationships. The team doesn't extract data and leave. They establish partnerships, explaining what they're doing, why, and how communities benefit. They offer compensation for time and data. They respect cultural norms and privacy concerns.

Testing happens in real conditions. Farmers test speech models while doing actual farm work. This means background noise from animals, wind, other people. It means using the phones they actually own, not lab devices. It means testing at times convenient for users, not researchers.

Feedback is gathered systematically. When does the system fail? How does failure feel? What alternative approaches would be better? What incentives would make farmers want to use voice technology? This qualitative feedback shapes the product roadmap.

Successful community engagement revealed insights that lab testing would miss. For example, farmers preferred shorter interactions. Instead of a conversation, they wanted to ask a quick question and get a quick answer. This shaped how Paza's interface was designed.

Another insight: farmers weren't just concerned about accuracy. They cared about consistency. If they asked the same question twice and got different answers, that created confusion. Ensuring consistent behavior mattered as much as overall accuracy.

Yet another: farmers wanted explanations. If the system misunderstood, they wanted to know why. Was it a bad connection? Did the system not know that word? This transparency helped farmers understand when to trust the system and when to try again.

These insights came from actually working with communities, not from assumptions about how they'd use technology.

Comparing Models: Phi vs. MMS vs. Whisper

Paza Bench allows direct comparison of how different models perform on the same languages.

The results are revealing.

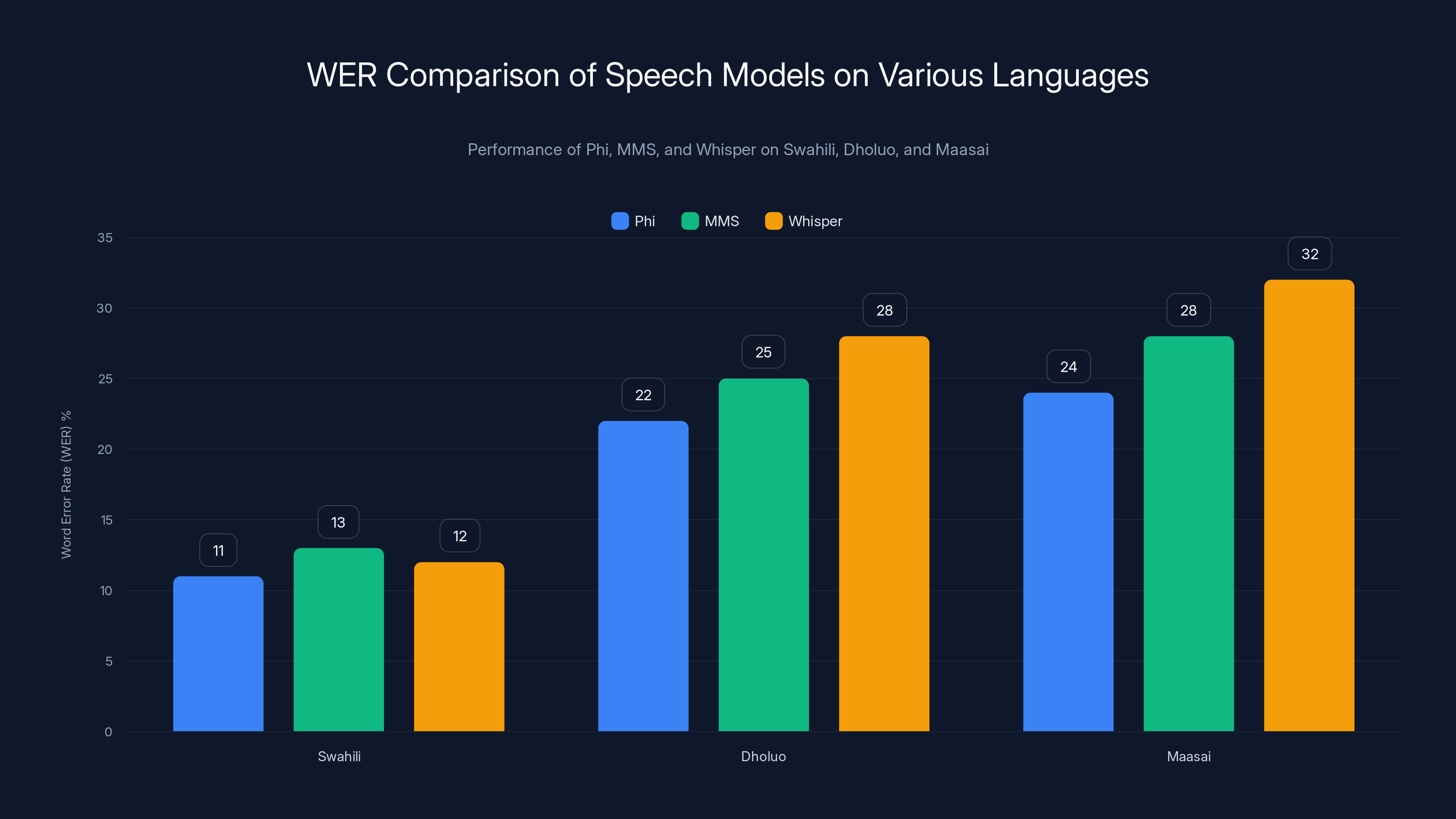

On Swahili, which has more training data available than other languages on the leaderboard, Whisper achieves approximately 12% WER. This is solid performance, reflecting Whisper's broad multilingual training. Phi achieves roughly 11% WER on the same language, showing slight superiority. MMS, designed specifically for multilingual coverage, achieves about 13% WER, competitive but not leading.

On Dholuo, a more challenging low-resource language with less available training data, the patterns shift. Whisper's performance degrades to around 28% WER, reflecting challenges with this language's phonetics and tonal characteristics. Phi achieves approximately 22% WER, showing better adaptation. MMS achieves roughly 25% WER.

These aren't small differences. The gap between 22% and 28% WER represents a substantial improvement in actual usability.

On Maasai, another language with limited training data, Phi continues to lead with approximately 24% WER. Whisper struggles to 32% WER. MMS sits at roughly 28% WER.

The pattern suggests that Phi's architecture and training approach generalize particularly well to low-resource African languages. This isn't obvious a priori. Whisper's massive multilingual training should be advantageous, yet it sometimes underperforms models designed more specifically for low-resource transfer learning.

Beyond accuracy, the models differ in other important dimensions.

Speed: Whisper is slower, designed for accuracy rather than low-latency inference. Phi is optimized for speed, achieving results in a few hundred milliseconds on modern hardware. MMS is somewhere in between.

Size: Whisper is large, millions of parameters. Phi's design is more compact. MMS falls between.

Robustness: Whisper excels at handling accents and background noise, a strength of its massive multilingual training. Phi is solid but not exceptional. MMS is built for coverage over robustness.

Adaptability: Phi adapts particularly well when fine-tuned on language-specific data. Whisper can adapt but requires more data. MMS, being already multilingual, has less room to improve with fine-tuning.

Choosing between models isn't about finding the "best" one. It's about finding the one that aligns with your constraints and priorities. For a resource-constrained mobile application, Phi might be the best choice despite Whisper's raw accuracy advantage, because Phi's efficiency allows on-device deployment.

Phi consistently outperforms Whisper and MMS in low-resource languages like Dholuo and Maasai, demonstrating its superior adaptation to these contexts. Estimated data.

Real-World Performance: Lab Results vs. Field Results

One of Paza's most important contributions is revealing the gap between lab performance and field performance.

When models are evaluated on clean, studio-recorded audio, performance is excellent. When those same models are deployed in actual farms, performance degrades dramatically.

The reasons are systematic. Lab data is clean. Field data has background noise. Lab speakers are careful and clear. Field speakers are natural, sometimes rushed. Lab audio is high quality. Field audio comes from phone microphones in suboptimal conditions.

The magnitude of the gap is startling. A model achieving 15% WER in the lab might achieve 45% WER in the field. That's not a minor difference. That's a catastrophic degradation.

This is why Paza includes field-recorded data in its benchmark. Researchers can see which models handle real-world audio well and which need improvement. A model that achieves good lab numbers but poor field numbers needs work before deployment.

Understanding this gap is crucial for practitioners. If you're building a voice application for low-resource environments, you can't rely on published benchmarks. You need to test in actual field conditions with actual users on actual devices.

Paza enables this by providing field evaluation data. Researchers and practitioners can see which models degrade gracefully and which fall apart.

Building Better Models: Fine-Tuning and Transfer Learning

Building an ASR model from scratch is expensive. You need thousands of hours of audio, linguistic expertise, computational resources, and time.

For low-resource languages, this is infeasible. Instead, Paza's approach uses transfer learning. Start with a model trained on high-resource languages, then fine-tune it on limited low-resource data.

The transfer learning approach works because acoustic knowledge is somewhat universal. The phonetic characteristics of human speech are similar across languages. A model trained on English learns acoustic principles that are relevant for Kikuyu.

Fine-tuning adapts this general knowledge to the specific language. The model learns the particular sounds, tones, and patterns of Kikuyu. With only hundreds of hours of data, this fine-tuning is fast and practical.

The effectiveness depends on the base model. A model trained on diverse languages transfers better than one trained on a single language. This is why MMS, trained on hundreds of languages, transfers well to new languages. Whisper, also trained multilingually, transfers well. Language-specific models transfer poorly.

But transfer learning has limits. If the source and target languages are very different, the improvement is minimal. A model trained only on English might transfer poorly to a tonal language like Maasai, where tone carries meaning.

Paza's research shows that multilingual source models are crucial for low-resource languages. The broader the source language coverage, the better the transfer. This argues for continued development of massively multilingual models, even if they're not optimal for any single language.

Fine-tuning also raises questions about data. How much low-resource language data is needed for effective fine-tuning? Paza's research suggests that even 50 hours can yield significant improvements, though more data helps. The diminishing returns curve is steep, meaning initial data provides enormous value but adding more becomes progressively less useful.

Addressing Bias and Fairness in Speech Recognition

Speech recognition systems don't perform equally for all speakers.

Women's voices are often recognized worse than men's. Non-native accents have higher error rates than native accents. Elderly speakers have higher error rates than young speakers. This is well-documented in the literature and particularly pronounced in low-resource language models.

Paza's benchmarking includes fairness metrics to make these disparities transparent.

The reasons for these disparities are multiple. Training data is often biased. If most training data comes from young male speakers, the model optimizes for that population. Limited data means less representation from minority groups. Acoustic differences in female voices or accented speech get less representation and are learned less well.

Paza's approach to fairness is measurement and transparency. By stratifying results by speaker demographics, disparities become visible. Models that show large performance gaps across demographics are flagged. Researchers working to improve fairness can measure progress.

Addressing fairness requires specific interventions. Data collection should prioritize diverse speakers. Training objectives should optimize for fairness, not just overall accuracy. Evaluation should emphasize equal performance across populations.

For low-resource languages, fairness is particularly critical. With limited data, it's easy to accidentally create systems that work for some speakers and fail for others. A speech system that works for young male farmers but fails for female farmers is worse than useless; it reinforces existing inequities.

Paza's fairness work is still early, but the framework is established. Leaderboard submissions are evaluated not just on overall accuracy but on demographic parity. This incentivizes researchers to build models that work well across all groups.

Estimated data shows varying performance across models with Model B having the lowest WER and CER, indicating superior accuracy. Model C struggles with higher error rates.

Infrastructure and Deployment: From Models to Products

Having good models isn't enough. You need infrastructure to deploy them.

Paza provides guidance and tools for deployment. The team has packaged models in formats that run on various platforms: mobile phones, web browsers, and servers.

For mobile deployment, the challenge is size and latency. Models must be small enough to download and install. Inference must be fast enough that users don't experience frustrating delays.

Paza's on-device models address this. They're optimized for mobile processors and limited RAM. They run inference in a few hundred milliseconds. They produce results fast enough for conversational interaction.

For web deployment, models are exposed through browser APIs and cloud services. Developers can send audio and receive transcriptions without building custom infrastructure.

For server deployment, models are containerized and run on cloud platforms. This is useful for applications that need high throughput or where computation can happen centrally.

Paza also addresses the operational aspects of deployment. How do you monitor model performance in production? How do you detect when accuracy degrades? How do you update models as they improve? Paza provides monitoring tools and best practices.

Security and privacy are built in. Audio can be processed locally without transmission. Developers can run models on their own infrastructure, never sending user data to third parties. For cases where data must be sent, encryption and privacy-preserving techniques are available.

This infrastructure work is unglamorous but essential. A perfect model that's impossible to deploy is worthless. Paza recognizes this and provides practical deployment solutions.

Open Source and Community Contribution

Paza is built on openness and community contribution.

All models are available as open-source code. All datasets are shared (with appropriate consent and privacy protection). All benchmarking code is publicly available. Researchers can verify results, build on the work, and contribute improvements.

This openness accelerates progress. Instead of each research group working independently, the community works together on a shared foundation. Improvements benefit everyone.

Community contribution takes multiple forms. Researchers submit models for evaluation on the leaderboard. Communities contribute audio data. Developers contribute code improvements. Linguists contribute linguistic insights.

Managing community contribution requires governance. How do you ensure quality? How do you handle disputes? How do you credit contributors? Paza has established processes addressing these questions.

The leaderboard explicitly credits researchers and institutions whose models are included. Community members who contribute data are acknowledged. Contributors are thanked and recognized.

Incentives matter. Making it easy and rewarding to contribute increases participation. Paza's infrastructure is designed for ease of contribution. Submitting a model, contributing data, or reporting issues is straightforward.

This community-driven approach has accelerated progress. The 52 models on the initial leaderboard represent contributions from dozens of researchers and institutions. This diversity accelerates progress because different approaches are tried and compared.

Impact on Development and Deployment

Paza's impact extends beyond research. It's beginning to influence real-world product development.

Developers building voice applications for African markets can now use Paza's models and benchmarks to make informed choices. Instead of guessing, they can see which models work best for their target languages.

NGOs working on development projects can incorporate speech technology confidently. They know the models are designed for low-resource contexts and have been tested in similar settings.

Governments in emerging markets can use Paza to support local language technology development. Some governments are incentivizing models that work well on their language, using Paza's leaderboard to measure progress.

This is how technology changes lives. Not through abstract research, but through concrete deployment that solves real problems. Paza is enabling that transition.

Early evidence suggests significant impact. In Kenya, where Paza's initial models were deployed, farmer adoption of voice-based agricultural tools has increased substantially. More farmers are comfortable using their phones to access information because the systems actually understand their language.

This is transformative. Imagine you're a farmer with limited education. You can't read well, so accessing written information is hard. But you speak fluently. If you can ask questions using your voice and get useful answers, that's a game-changer.

Challenges and Remaining Gaps

Paza is significant progress, but it doesn't solve all challenges.

Data remains scarce. Even 50 hours of data per language isn't abundant by traditional ASR standards. Paza's models work with limited data, but more data would improve performance significantly. Collecting this data sustainably is an ongoing challenge.

Dialects present challenges. Languages like Kikuyu have multiple dialects. A model trained on one dialect might perform poorly on another. Paza's benchmarks reveal these disparities, but addressing them requires strategic data collection.

Tone languages are particularly challenging. Maasai has tonal elements that carry meaning. Capturing and representing tone in acoustic models requires specialized techniques. Paza's work on tone languages is ongoing.

Cross-lingual interference is real. When a language has some existing ASR infrastructure that's poor, the contaminated data can degrade transfer learning. Distinguishing good and bad training data is a challenge.

Evaluation data quality matters enormously. Transcribing audio requires linguistic expertise. For low-resource languages, finding transcribers is difficult. Data quality issues can skew benchmarks. Paza is developing best practices for transcription quality control.

Sustainability is crucial. Paza can't be a one-time project. Continuous improvement requires ongoing investment. Community engagement requires long-term relationships. Governance requires resources. Paza is working on sustainable funding models and institutional commitment.

Future Directions: Where Paza Headed

Paza's roadmap extends beyond current capabilities.

Expanding language coverage is a priority. The initial leaderboard includes 39 African languages, but Africa has thousands of languages. Expanding to more languages requires partnership with more communities and more funding.

Improving model quality is an ongoing effort. As more data becomes available and research progresses, models will improve. The leaderboard will track this progress.

Addressing additional tasks is planned. Speech translation could help non-native speakers communicate. Speaker identification could enable personalized responses. Emotion recognition could improve human-computer interaction. These extensions leverage ASR technology toward additional use cases.

Expanding geographic coverage is important. Paza launched in Kenya because of Project Gecko's existing relationships. Expanding to other African countries, other regions in Asia, and other low-resource communities requires similar community partnerships.

Integrating with NLP is a natural next step. Better language models could follow transcription, improving downstream task performance. End-to-end learning across speech and language could improve results.

Industry partnerships are developing. Companies interested in reaching new markets are testing Paza's models and infrastructure. This creates funding and partnership opportunities that accelerate progress.

Policy advocacy is emerging. Paza's team is working with governments to support speech technology development for local languages. Some governments are funding research, others are creating data resources. Policy support can accelerate progress significantly.

The Broader Implications for AI Equity

Paza is part of a larger movement toward AI for everyone, not just the wealthy.

For decades, AI has concentrated benefits in wealthy countries and wealthy languages. English-language AI is extraordinarily advanced. Japanese AI is sophisticated. French AI is mature. But Swahili AI, Kikuyu AI, Somali AI? Nearly nonexistent.

This creates a world where AI benefits flow disproportionately to already-privileged populations. A farmer in rural Kenya can't use modern AI for agricultural advice because the AI doesn't speak their language.

Paza begins correcting this imbalance. By investing in low-resource language speech technology, it democratizes access to AI tools. A farmer can now ask questions and receive answers using their native language.

This isn't charity. It's sound business. Billions of people represent enormous economic opportunity. Companies that can serve non-English markets will have access to populations that others ignore.

It's also an ethical imperative. If AI is going to shape society, it should work for everyone. Excluding billions of people from AI because they don't speak English is indefensible.

Paza's model—combining research rigor with community engagement, open-source infrastructure with commercial viability, academic contribution with practical deployment—points toward how AI equity can be achieved.

FAQ

What exactly is Paza?

Paza is a human-centered automatic speech recognition (ASR) framework developed by Microsoft Research in collaboration with communities in Kenya. It includes both speech recognition models optimized for low-resource languages and real-world performance on actual mobile devices, plus Paza Bench, the first leaderboard specifically designed for evaluating low-resource ASR systems across 39 African languages and 52 models.

How does Paza differ from other speech recognition systems?

Unlike most ASR systems that optimize for lab performance on clean audio, Paza is specifically designed and tested for low-resource real-world conditions. It centers community input throughout development, has been validated with actual farmers on actual devices in actual field settings, and includes benchmarking metrics and datasets that reflect low-resource language characteristics rather than just replicating high-resource language evaluation methods.

Which languages does Paza support?

Paza's initial implementation includes six Kenyan languages: Swahili, Dholuo, Kalenjin, Kikuyu, Maasai, and Somali. Paza Bench, the leaderboard, launches with 39 African languages and 52 different ASR models, enabling comparison across many more languages and model approaches.

How accurate is Paza compared to systems like Google Speech-to-Text or Amazon Transcribe?

Paza's accuracy varies by language and model. On well-resourced languages like Swahili, leading models achieve around 12% word error rate, competitive with commercial systems. On low-resource languages, accuracy is lower, with errors ranging from 20% to 45% depending on the specific language, model, and acoustic conditions. Paza's strength isn't necessarily beating commercial systems on every metric, but providing systems that actually work for languages these commercial systems don't support at all.

Can I use Paza models on my phone without internet connection?

Yes, Paza includes on-device models optimized to run locally on mobile phones. These models are smaller than larger versions, run inference in hundreds of milliseconds, and work offline. The tradeoff is slightly reduced accuracy compared to larger models, but performance is still acceptable for practical applications like agricultural information access.

How is Paza different from Meta's MMS or Open AI's Whisper?

Paza is not a competing model, but rather a benchmarking framework and set of implementations that includes MMS, Whisper, and other models for comparison. Paza's unique contribution is that it evaluates these different approaches on low-resource languages specifically, provides field-based evaluation data, and packages models for mobile deployment in low-resource contexts. Researchers and developers can use Paza Bench to understand how each model performs and choose accordingly.

How does Paza ensure fairness and prevent discrimination?

Paza's benchmarking includes fairness metrics that evaluate model performance separately for different speaker demographics including age, gender, and region. Results are stratified to reveal any significant performance gaps across populations. This transparency helps identify models that work equally well for all speakers versus models that perform well overall but poorly for specific groups, incentivizing developers to build more equitable systems.

How can I contribute data or models to Paza?

Paza welcomes community contributions through multiple channels. Researchers can submit models for evaluation on Paza Bench through a documented submission process. Communities can contribute audio data through partnerships that ensure ethical data collection, compensation, and consent. Developers can contribute code improvements through the open-source repositories. Specific contribution guidelines and contacts are available on Paza's public documentation.

What problem does Paza actually solve for end users?

For farmers and rural users in low-resource areas, Paza enables voice-based access to information on agricultural prices, weather forecasts, crop management techniques, and market conditions—all in their native language. For developers, Paza solves the problem of how to include speech recognition in applications serving low-resource language communities. For researchers, Paza provides standardized benchmarks and datasets to advance speech technology for underserved languages.

Why does Microsoft invest in low-resource language speech technology?

Beyond the ethical imperative to serve all populations, there's significant business opportunity in serving billions of people in emerging markets who currently lack good speech technology. Companies that can successfully build voice products for these markets gain access to underserved user populations and competitive advantage in emerging economies. Microsoft Research's investment reflects both commitment to AI equity and recognition of this market opportunity.

Conclusion: The Path Forward for Universal Speech Technology

Speech recognition is one of technology's great achievements. The ability to speak naturally and have a computer understand, transcribe, and respond represents genuine human-computer interaction. Yet this achievement benefits primarily English speakers and a handful of other well-resourced languages.

Paza changes this story. By combining rigorous research with community partnership, open-source infrastructure with practical deployment, benchmarking rigor with fairness consideration, Paza demonstrates that low-resource language speech technology isn't just possible—it's necessary.

The impact is already visible. Farmers in Kenya can now ask questions in Kikuyu and get useful responses. Communities are seeing technology that works for them, not against them. Researchers are no longer working in silos, but contributing to a shared leaderboard and open-source ecosystem.

This is how AI equity moves from concept to reality. Not through theoretical arguments about fairness, but through concrete systems that serve real communities with real problems.

Yet the work is far from finished. Paza covers six languages out of thousands. The 52 models on the leaderboard can improve. Acoustic challenges like tonal languages need more research. Deployment infrastructure needs strengthening. Community partnerships need scaling.

The path forward requires sustained effort. It requires funding and institutional commitment. It requires partnerships with communities, respect for their languages and cultures, and benefit-sharing when technology succeeds. It requires openness, so improvements benefit everyone.

But the direction is clear. Speech technology will eventually work for everyone. The question is how quickly. Paza accelerates that timeline by years. By showing what's possible when you center real users, measure real-world performance, and build openly, Paza sets a template for how AI can be built equitably.

The billions of people who've been excluded from the AI revolution so far are waiting. They don't need AI that works only in English or Mandarin. They need AI that speaks their language, understands their accent, solves their problems.

Paza begins delivering on that promise. And that matters far more than any research metric could capture.

Key Takeaways

- Paza is a human-centered ASR framework combining models, benchmarking, and community engagement specifically for low-resource languages, addressing a critical gap where billions of people can't use voice AI in their native language

- PazaBench is the first leaderboard evaluating speech recognition on 39 African languages with 52 models, revealing that performance varies dramatically across different model architectures and real-world conditions often degrade accuracy by 30-40%

- The framework emerged from Project Gecko field work showing how lab-optimized speech systems fail in real conditions, demonstrating why community testing on actual devices with actual users is essential for appropriate AI development

- Paza's on-device models enable offline speech recognition on resource-constrained mobile phones, solving practical deployment challenges where uploading audio to servers is infeasible due to bandwidth and privacy concerns

- Phi model shows superior generalization to low-resource languages compared to larger systems like Whisper and MMS, suggesting that specialized transfer learning approaches outperform massive multilingual models for underserved languages

Related Articles

- Google's Hume AI Acquisition: Why Voice Is Winning [2025]

- Google's Hume AI Acquisition: The Future of Emotionally Intelligent Voice Assistants [2025]

- Subtle's AI Voice Earbuds: Redefining Noise Cancellation [2025]

- Voice-Activated Task Management: AI Productivity Tools [2025]

- Clear Audio Drives AI Productivity: Why Sound Quality Matters [2025]

- Alexa Plus Website Early Access: AI Assistant Now on Desktop [2025]