Understanding Project Silica: The Glass Revolution in Data Storage

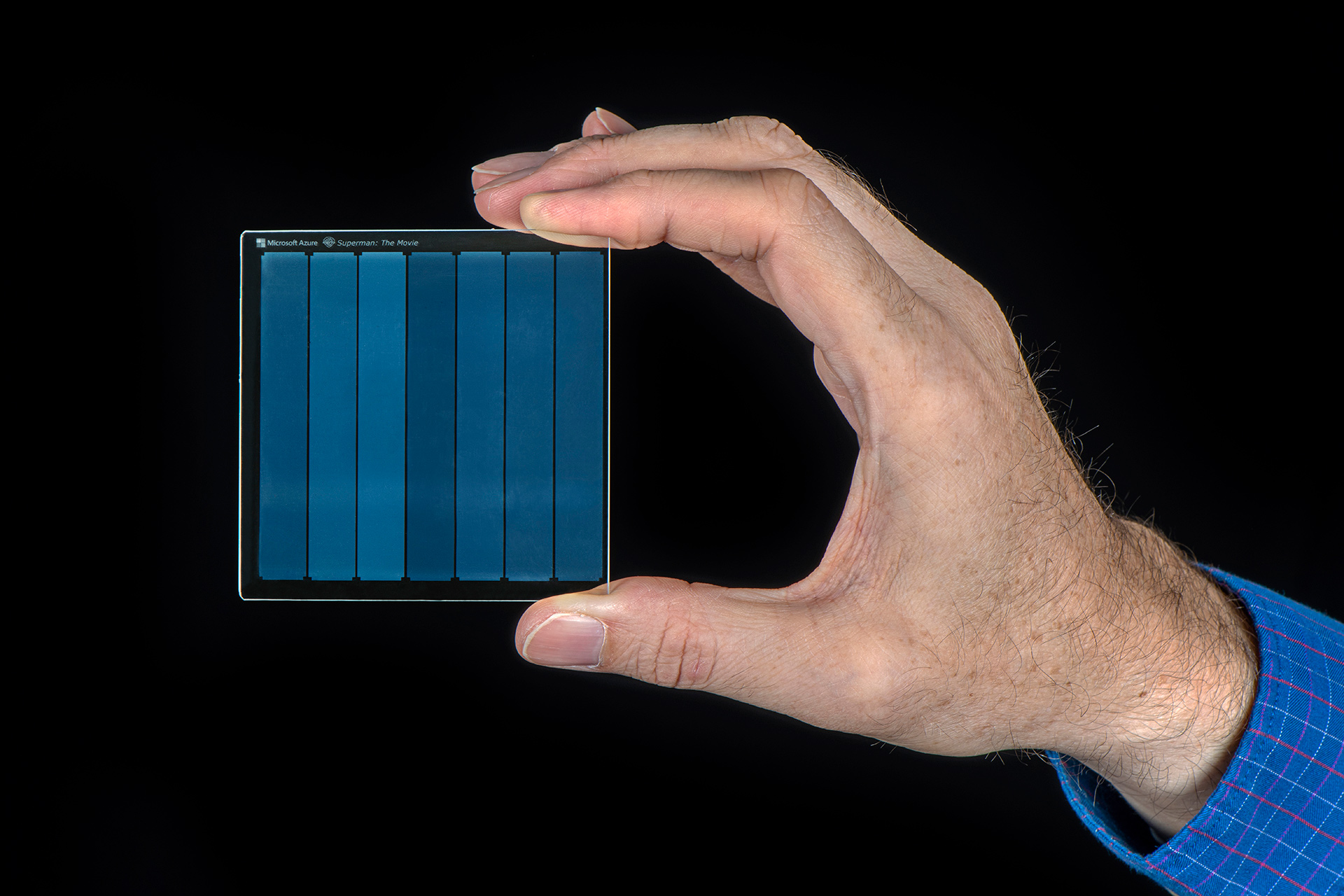

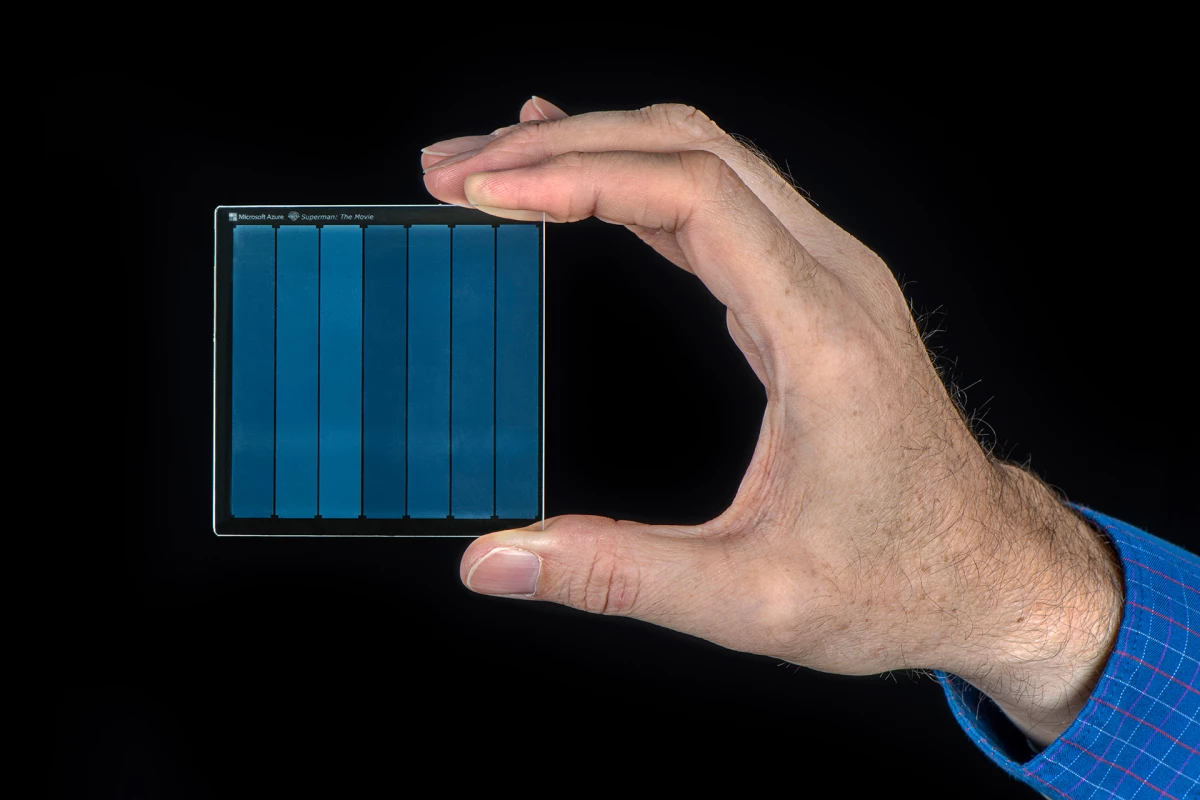

Imagine data that outlasts civilizations. Not degrading, not corrupted, not forgotten. That's the promise of Project Silica, Microsoft Research's audacious effort to encode digital information into glass using femtosecond lasers. We're talking about a storage medium that could preserve your entire digital life for 10,000 years without needing electricity, maintenance, or replacement.

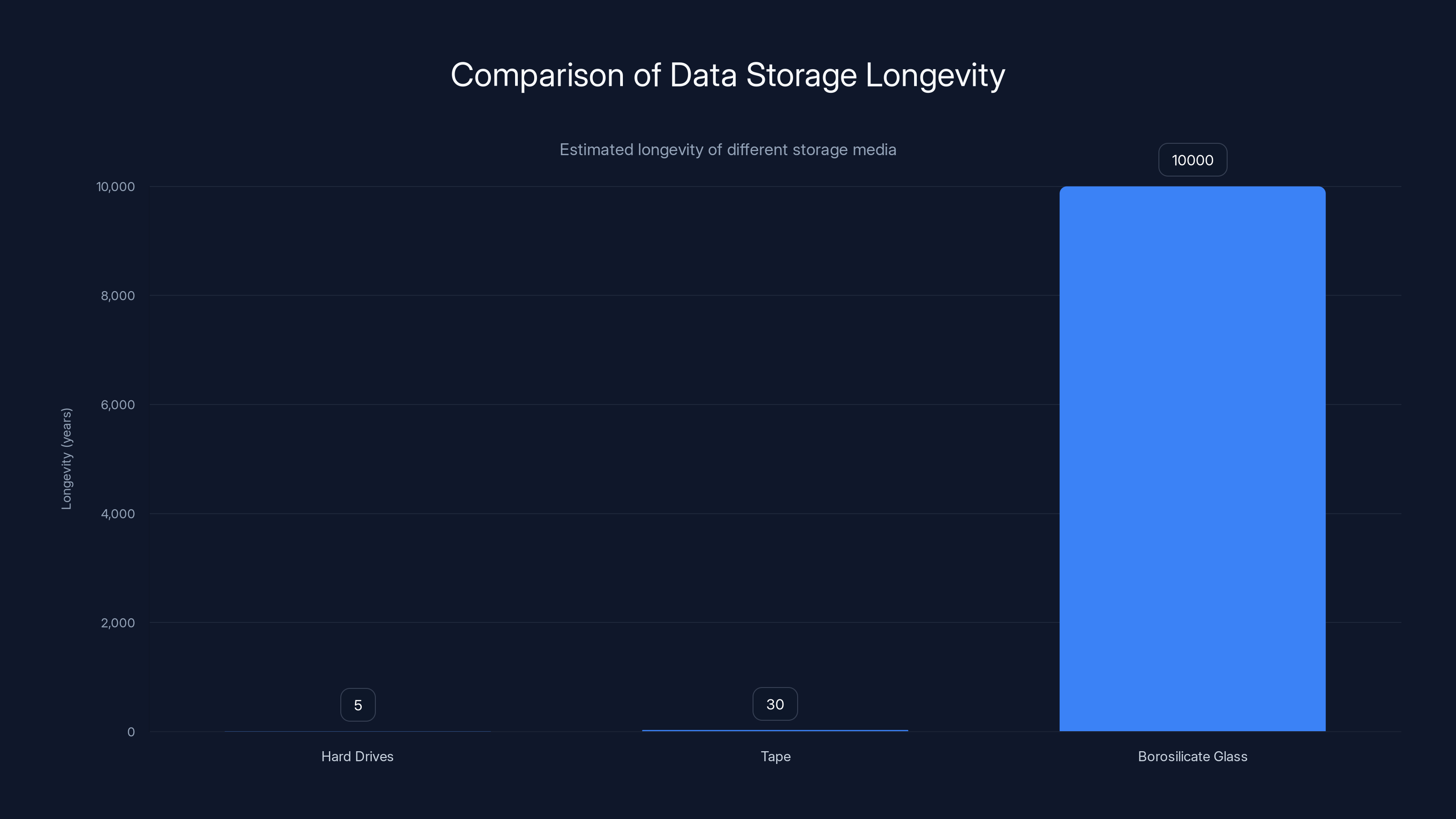

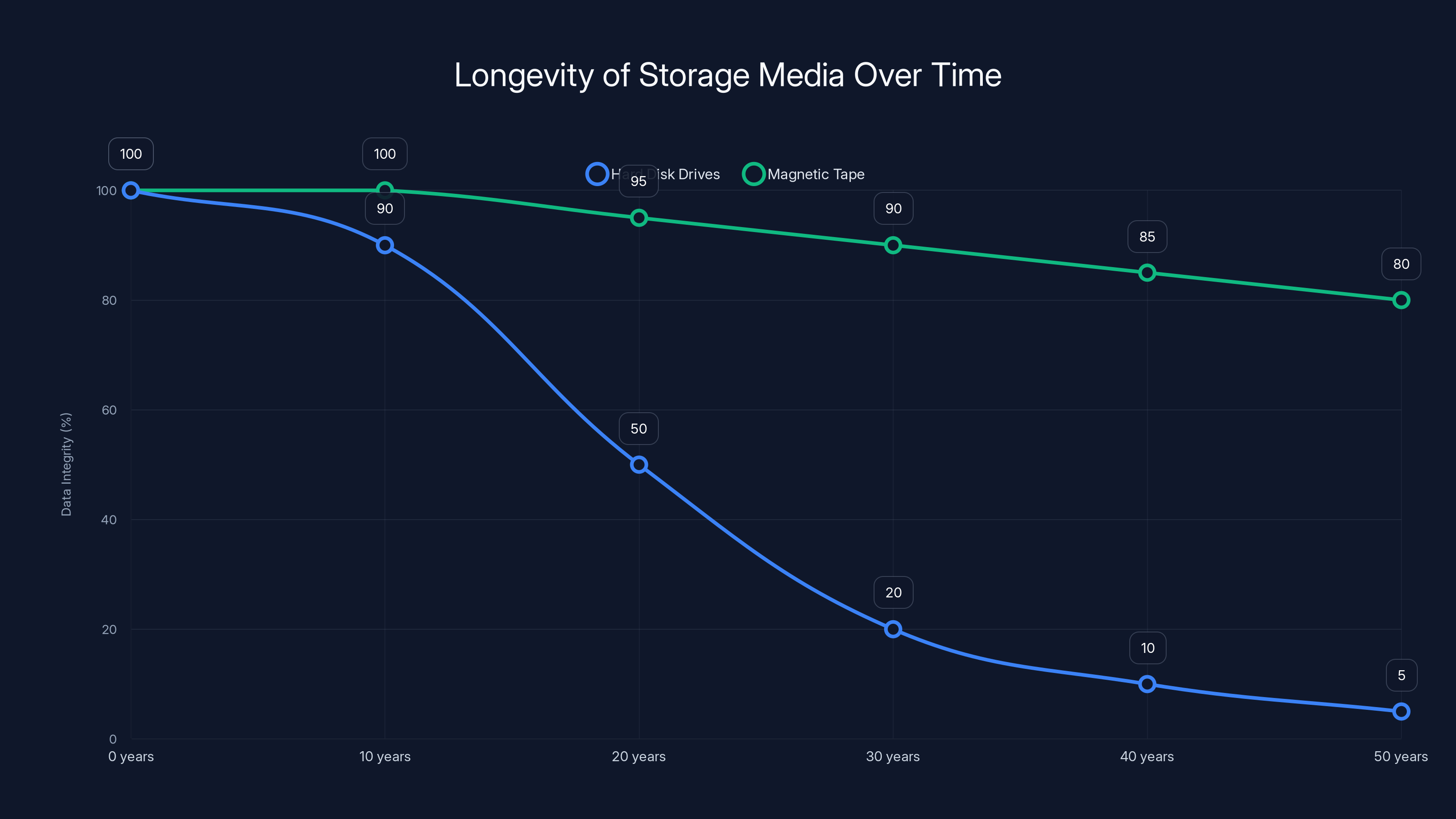

For decades, data preservation has been the tech industry's dirty secret. Hard drives fail within 5-10 years. Magnetic tape, the industry workhorse for archival, degrades after 30 years at best. Cloud storage depends on companies that might not exist in 50 years. Meanwhile, institutions like the Library of Congress, national governments, and major corporations face an existential problem: how do you preserve digital information for future generations?

Project Silica emerges as something genuinely different. It's not a faster hard drive or a smarter database. It's a fundamental rethinking of what storage means. Instead of magnetic particles or silicon wafers, data gets written directly into the atomic structure of glass. The material is as permanent as the physical world allows. No electricity needed. No moving parts. Just glass, sitting in a vault, holding information in three dimensions.

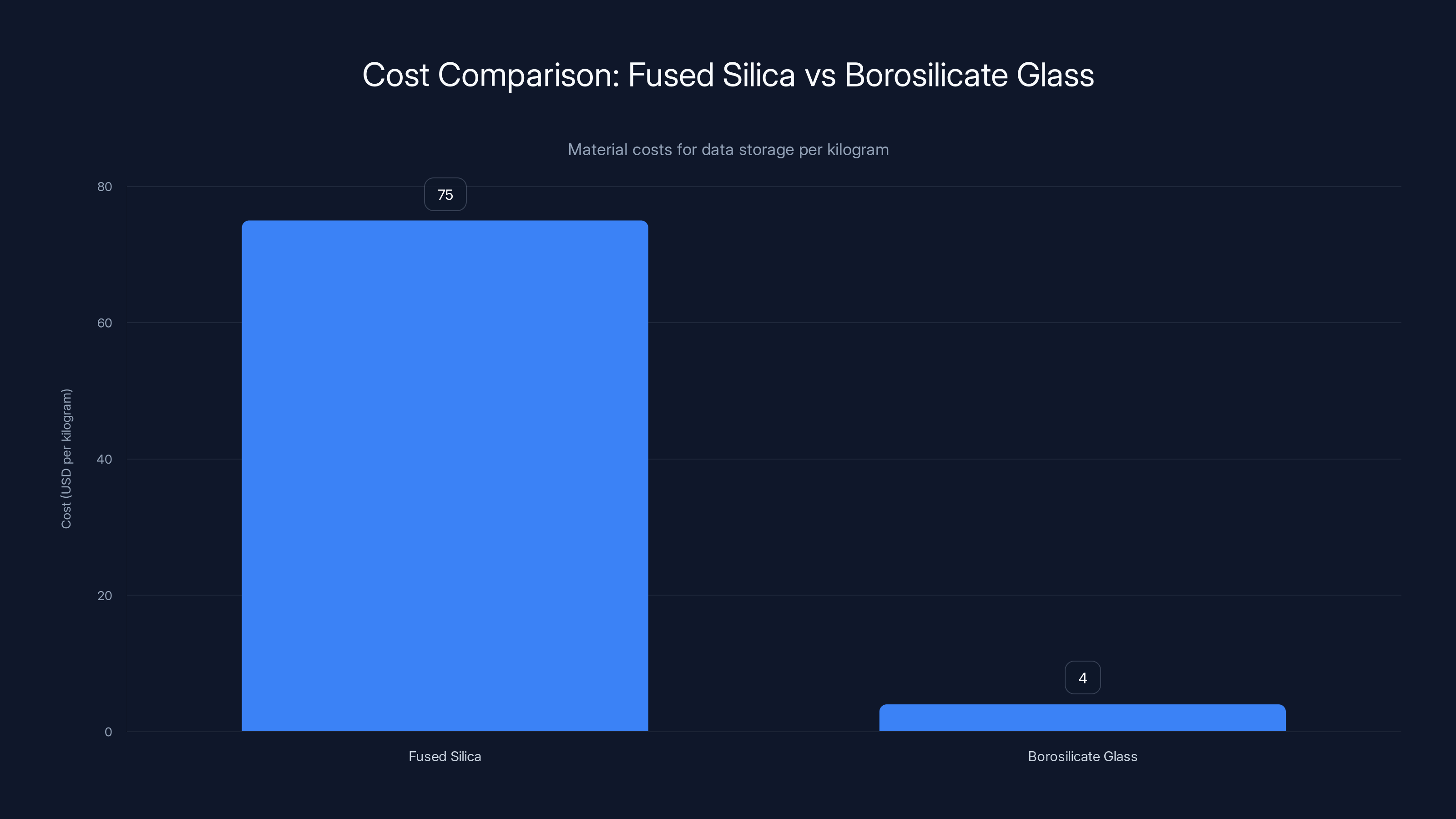

The breakthrough published in Nature in early 2026 represents a watershed moment. The research team moved beyond expensive fused silica (the kind used in laboratory optics) to ordinary borosilicate glass, the same material in your kitchen oven door. This shift matters more than it might sound. It transforms glass storage from a theoretical curiosity into something economically viable. Cost matters. Availability matters. A technology only changes the world if it can actually be manufactured at scale.

Here's what's actually remarkable about this work: it solves multiple hard problems simultaneously. The femtosecond laser writing process now works in parallel, meaning faster encoding. The reading system simplified from three cameras to one. The manufacturing process became less complex. And the data? The evidence suggests it persists for at least 10,000 years, verified through accelerated aging tests. Each improvement addresses a real barrier to commercialization. This isn't elegant research sitting in a lab. This is engineering that works.

The implications ripple outward. Archives won't need to refresh their storage media every three decades. Government records could actually outlive the governments that created them. Scientific datasets won't disappear when funding runs out. Cultural heritage institutions get a genuine solution to digital preservation. Even for companies, the economics shift. A one-time write cost to glass potentially beats paying for storage infrastructure, power, and maintenance across decades.

But technology adoption rarely follows pure logic. We'll explore how Project Silica works, why it matters, what barriers remain, and where this path might lead.

TL; DR

- Glass as permanent storage: Project Silica encodes data into borosilicate glass using femtosecond lasers, creating a storage medium that lasts 10,000+ years without degradation

- Cost breakthrough: New techniques work with ordinary kitchen-grade borosilicate glass instead of expensive fused silica, reducing material costs and improving availability

- Simplified systems: Parallel writing, single-camera reading, and streamlined manufacturing make the technology more practical and closer to commercialization

- Phase voxel method: A single laser pulse creates data structures requiring less complexity than previous approaches, reducing both cost and technical burden

- Real preservation problem solved: Traditional storage (hard drives, tape) degrades in 5-30 years, while glass storage addresses archival needs for institutions, governments, and enterprises

Borosilicate glass offers an estimated data longevity of up to 10,000 years, far surpassing traditional storage media like hard drives and tape. Estimated data.

The Data Preservation Crisis Nobody Talks About

Walk into any major organization's data center, and you'll see something contradictory. Enormous budgets spent on redundancy, backup, disaster recovery, and failover systems. Yet simultaneously, almost every organization's older data becomes inaccessible or lost. The reason isn't technical incompetence. It's physical reality meeting economic pressure.

Hard disk drives, the workhorses of storage, have mechanical components. Spindle motors, read-write heads, magnetic platters. These parts wear out. The most reliable enterprise drives last around 8-10 years before failure rates climb sharply. Some last longer. Some fail faster. But there's a hard ceiling. Physics wins.

Magnetic tape, the archival standard since the 1990s, performs better. Much better, actually. Properly stored tape can survive 30-50 years. But "properly stored" means climate-controlled vaults, no physical handling, careful media rotation. And even in ideal conditions, bit rot happens. Magnetic particles gradually lose their charge. The stored data becomes unreadable.

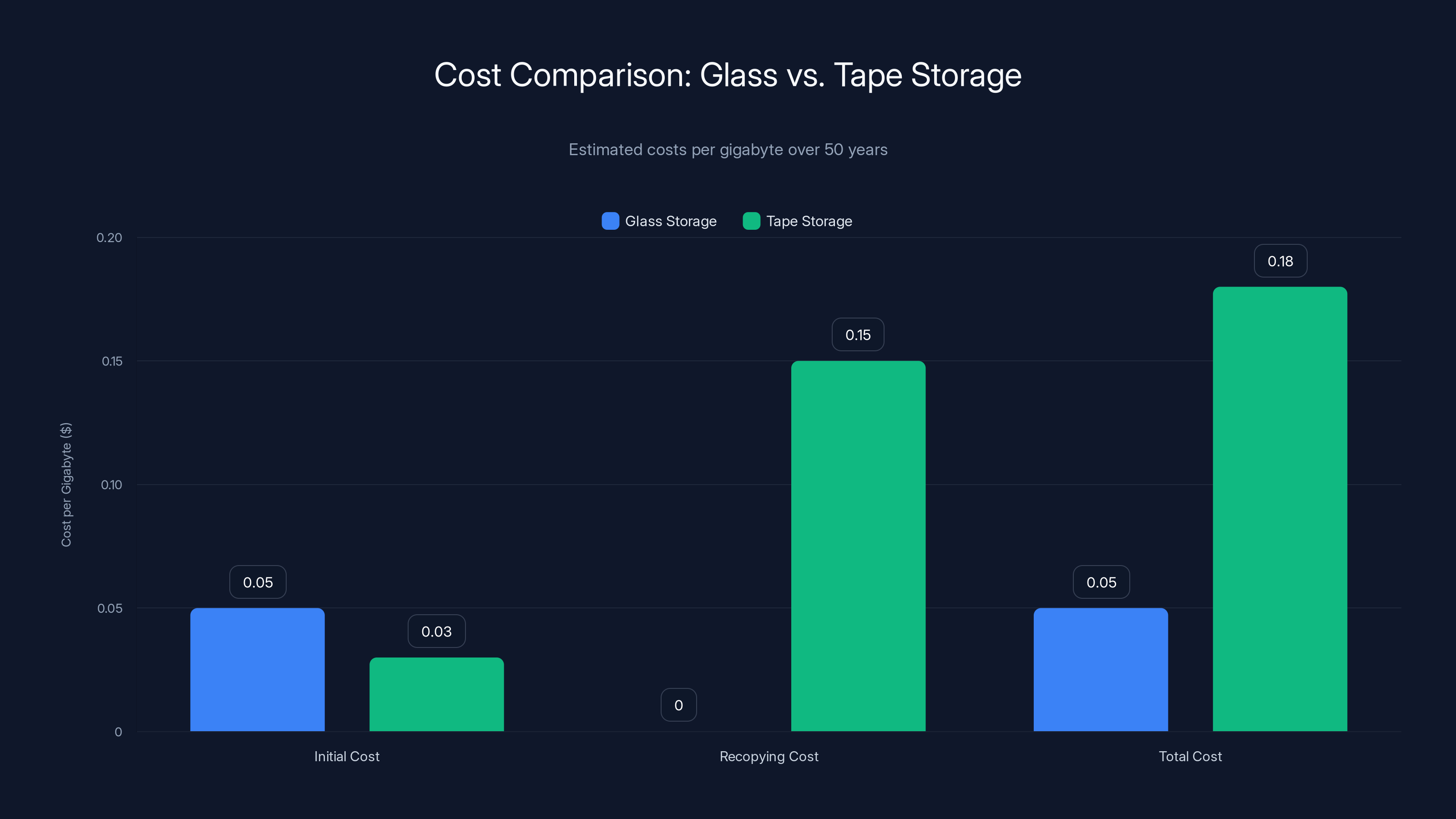

This creates a strange economic situation. You spend millions to store data you might never access again, hoping it stays readable. Then at some point (often arbitrarily around 5-10 years), you copy everything to new media because the old storage is becoming risky. Now you've spent twice. Copy again in another five years, and you've tripled the cost. Over a century, the same data gets recopied multiple times, each generation introducing risk of corruption or loss.

Governments face this acutely. A law passed today might need to be referenced in 100 years. Digital signatures, legislative records, court documents—these things need to exist in readable form across centuries. Yet every technology you store them on becomes obsolete. Floppy disks? Dead. Zip drives? Gone. USB formats? Already being phased out. The average enterprise data format has a lifespan of maybe 15 years before the software that reads it disappears.

Scientific institutions have similar problems. A climate dataset from 1975 is extremely valuable. But the tape it was recorded on, the file format, the metadata—some of it's probably lost. You have the physical data but can't extract the information anymore. Centuries of scientific progress gets locked away in dead formats.

Companies rarely discuss this publicly. It's embarrassing. You imagine yourself protecting data forever, but the practical reality is that you're cycling media constantly, hoping nothing gets corrupted in the transition. The risk accumulates. The cost compounds.

This is the genuine problem Project Silica addresses. Not faster storage. Not cheaper storage per gigabyte in the short term. But storage that actually stays readable without intervention. Storage that lets institutions stop the constant migration cycle.

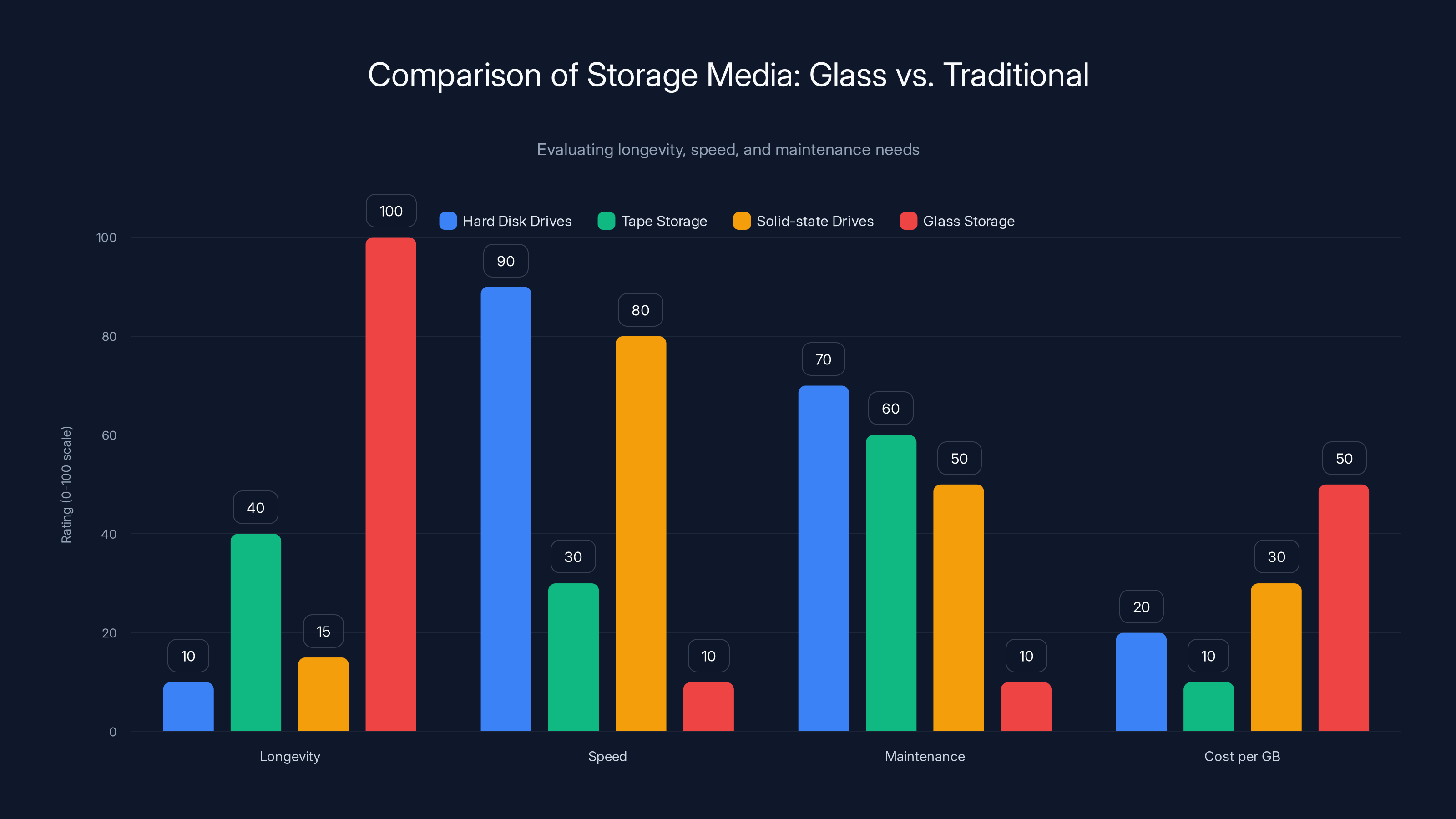

Glass storage excels in longevity and low maintenance, making it ideal for archival purposes, while traditional media like HDDs and SSDs offer speed and cost benefits. Estimated data.

How Femtosecond Lasers Write Data Into Glass

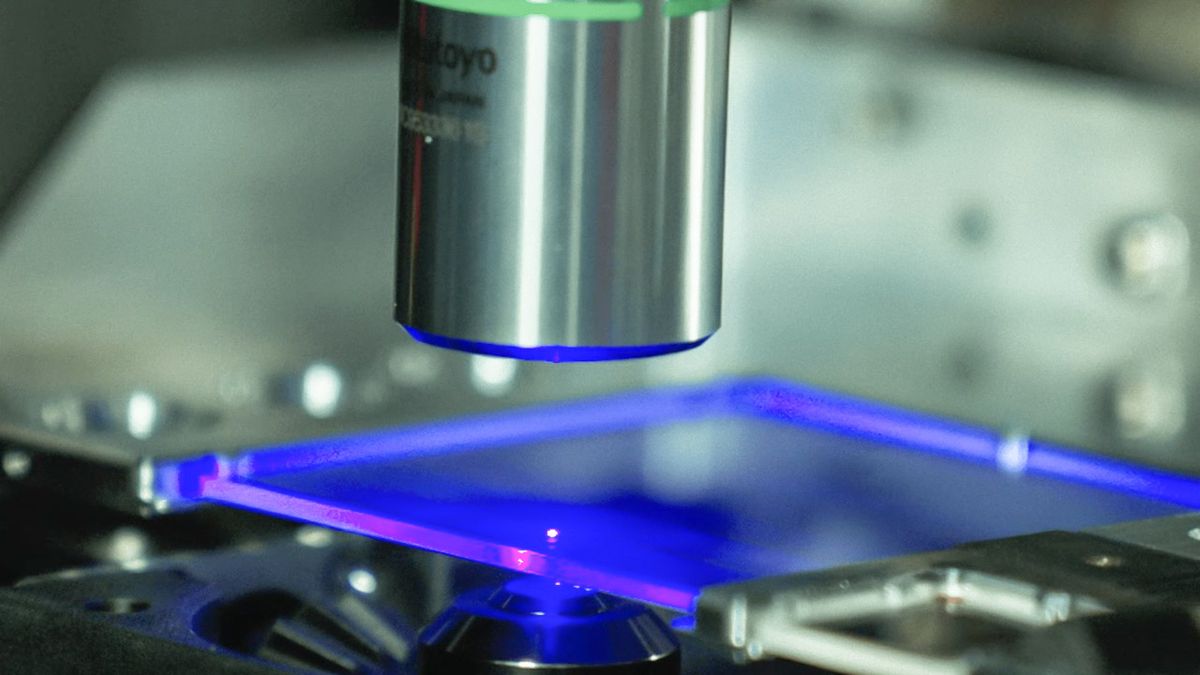

The mechanism seems almost supernatural until you understand the physics. A femtosecond laser fires an incredibly brief pulse at the glass. The pulse lasts less than a trillionth of a second. In that impossibly short timeframe, the laser energy is so concentrated that it causes a localized change in the glass structure.

Here's the key insight: the glass doesn't melt. Doesn't crack. Doesn't visibly change. Instead, the laser creates microscopic zones of altered glass density and crystal structure. These modified zones have different optical properties than surrounding glass. A camera can detect these differences by measuring how light passes through the glass. Where the laser fired, the glass structure changed slightly. Where it didn't fire, the glass remains unmodified. Binary: one or zero.

The laser can fire thousands of times per second, each pulse creating a voxel (a three-dimensional pixel) of data. Stack these voxels in three dimensions, and you can store an enormous amount of information in a tiny volume. A piece of glass the size of a sugar cube can hold gigabytes of data, all encoded in the physical structure.

What makes this fundamentally different from traditional storage? Those bits aren't volatile. They're not magnetic particles that can lose their charge. They're not electrical charges that need constant power to maintain. They're physical structure. The glass is the data. You can't corrupt what's already written into atomic arrangement.

This permanence comes with trade-offs. Writing is slow compared to hard drives. Reading requires a camera and optical equipment. The process can't be easily erased or overwritten. You write once, read many times. This architectural pattern, called "WORM" (Write Once, Read Many), is perfect for archives. Terrible for databases. That's the boundary of where this technology makes sense.

The practical process works like this: A femtosecond laser focuses on a specific point inside the glass. The laser fires, creating a voxel. A micrometre at a time, the laser moves to the next location. The system writes data in layers, building three-dimensional structures. Modern systems can create arrays of these voxels in parallel, writing multiple bits simultaneously.

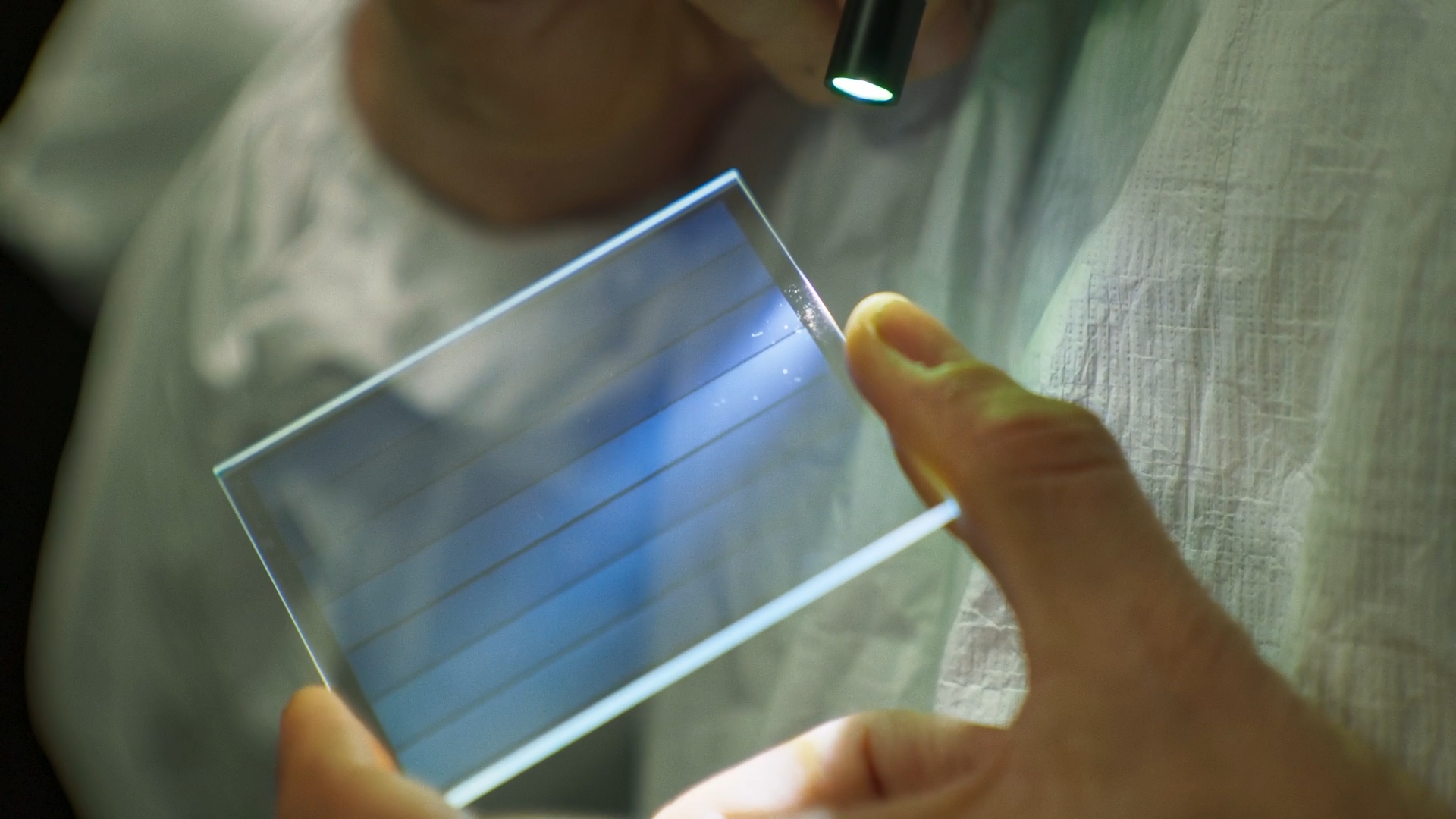

Reading requires different equipment. Light passes through the glass in specific patterns. Cameras capture how the light scatters and bends. Software analyzes these patterns to determine which voxels were written and which were left untouched. From this, the original binary data reconstructs. The process takes longer than hard drive reading, but it's reliable and requires no power to maintain the stored data.

Previous versions of this technology used fused silica, an expensive, high-purity glass made for laboratory optics. It worked well because the pure material has consistent properties, making the laser writing predictable. But fused silica costs hundreds of dollars per kilogram. Only institutions with serious budgets could experiment with it.

The Breakthrough: From Expensive Fused Silica to Kitchen-Grade Borosilicate Glass

The 2026 Nature publication details something simple in concept but extremely difficult in execution: making femtosecond laser writing work in ordinary borosilicate glass. Why was this hard? Because borosilicate glass is fundamentally different at the microscopic level.

Fused silica is nearly pure silicon dioxide. The atomic structure is predictable and uniform. When a femtosecond laser pulse modifies this structure, the effect is consistent and repeatable. Borosilicate glass, by contrast, contains other elements (boron, sodium, calcium). These components affect how the laser interacts with the material. The same laser pulse that creates a clean voxel in fused silica might create irregular structures in borosilicate glass. Reading those structures becomes unreliable.

The research team developed new encoding techniques specifically optimized for borosilicate glass properties. They developed what the research calls the "phase voxel method," which requires only a single laser pulse per voxel instead of multiple pulses. This simplification matters enormously. Fewer pulses mean faster writing, less heat buildup in the glass, and lower system cost.

Consider the economics shift. Fused silica at ~

But there's another advantage hidden in this shift. Borosilicate glass is everywhere. It's the material in laboratory beakers, kitchen cookware, industrial applications. Supply chains exist. Manufacturing capacity is available. You don't need to build entirely new industrial infrastructure. You can leverage existing production.

The research validated that data written into borosilicate glass using the new phase voxel method persists beyond 10,000 years through accelerated aging tests. These tests don't wait 10,000 years (obviously). Instead, they expose samples to temperature and humidity extremes to simulate centuries of aging in accelerated time. The data remained readable after equivalent aging that would age ordinary glass thousands of years.

The speed improvement is substantial. Previous systems required multiple sequential laser pulses to build up the data structure. The phase voxel method does it in one pulse. This enables true parallel writing, where multiple lasers hit different parts of the glass simultaneously, dramatically increasing throughput.

Simultaneously, the reading system simplified. Earlier glass storage systems required three cameras positioned around the glass to capture different optical signatures. The new approach works with a single camera, reducing the complexity of the reading device and the processing power required.

These aren't cosmetic improvements. Each one removes a barrier to commercialization. Slower writing? Get faster systems using parallelization. Complex reading? Use a simple camera. Expensive material? Use kitchen glass. Manufacturing expertise? Already exists in the supply chain.

Magnetic tape maintains data integrity significantly longer than hard disk drives, with tapes still retaining 80% integrity after 50 years compared to 5% for hard drives. Estimated data based on typical lifespan.

Technical Architecture: How Data Actually Gets Stored and Retrieved

The technical system breaks into three components: the writing apparatus, the glass medium, and the reading system. Understanding how each works clarifies why this approach is both powerful and limited.

The Writing System

A femtosecond laser, typically a 1030-nanometre wavelength fiber laser, fires pulses toward a focusing lens. The lens concentrates the beam to a diffraction-limited spot, roughly one micrometre in diameter. This spot is positioned inside the glass using motorized stages with nanometre precision.

The laser fires at a repetition rate (typically 100 kilohertz to a few megahertz), creating one voxel per pulse. The motorized stages move the focus point to the next location. This happens layer by layer, depth by depth, creating a three-dimensional lattice of modified glass.

Earlier systems required complex pulse shaping and multiple sequential pulses to build adequate voxel structure. The phase voxel method changed this. It creates the necessary phase transition (the change in optical properties) with a single pulse. The physics of how borosilicate glass responds allows this simpler approach, but only after careful optimization of laser wavelength, pulse energy, and timing.

Parallelization recently became possible. Instead of one laser writing sequentially, multiple lasers can fire into the same glass simultaneously, each writing to different regions. This enables far higher throughput. A system with ten parallel laser channels could theoretically write ten times faster than a sequential system. Real systems achieve somewhat less than this theoretical limit, but parallel writing still dramatically accelerates the process.

The Glass Medium

Borosilicate glass has a few critical properties for this application. It must be optically transparent (obviously, or lasers can't write into it and light can't read it). It must be chemically stable. It must not undergo unwanted aging or crystallization over millennia.

Borosilicate glass meets all these requirements. It's been used in scientific equipment for over a century. Historical samples from the 1800s are still perfectly clear. This proven stability gives confidence that new glass storage will endure.

The glass pieces in research demonstrations are typically several millimetres thick. Data is written throughout the volume. A single glass tablet could theoretically hold terabytes of data, depending on voxel size and density.

One interesting aspect: the data doesn't degrade if the glass breaks. If a glass tablet shatters, the voxels within the fragments remain intact. You could theoretically recover most or all of the data from the pieces. This is completely unlike hard drives, where mechanical damage usually means total failure.

The Reading System

Reading requires optical equipment but nothing exotic. Light from a microscope illuminates the glass. The modified voxels created by the laser have different optical properties—different refractive index, different birefringence, different light scattering. A camera captures these optical signatures.

The light propagating through the glass is modified by each voxel it passes through. By scanning through different planes of the glass and analyzing how the light is altered, the reading system can determine the three-dimensional structure of voxels. Software reconstructs the original data from these optical patterns.

The process is slower than reading a hard drive. A hard drive might read hundreds of megabytes per second. Glass storage reading speeds are currently measured in kilobytes to perhaps a few megabytes per second for optimized systems. For an archive you access once per decade, this is irrelevant. For an active database you query constantly, this is fatal.

But the reading system is simple. No complex electronics needed inside the glass. No wear from repeated access. An archival vault could have a handful of optical readers serving thousands of glass tablets. The per-device cost is low.

Comparison: Glass Storage vs. Traditional Media

When is glass storage the right choice? When is it overkill? Understanding the tradeoffs clarifies where this technology belongs in the storage hierarchy.

Hard Disk Drives dominate active data storage. They're fast, random-access, and cheap per gigabyte. Reading and writing happens in milliseconds. But drives fail. Mechanical parts wear out. After 8-10 years, failure rates climb. For data you access constantly, hard drives are correct. For data you hope never to use, they're a trap.

Tape storage is the current archival standard. LTO (Linear Tape Open) tape can theoretically store data for 30-50 years. Cost per gigabyte is extremely low. But you need climate-controlled storage, regular verification, media migration every 5-10 years, and equipment to read the tape. Tape works because it's good enough for current requirements. Glass storage is overengineering for someone who's fine recopying data every decade.

Solid-state drives use flash memory. No mechanical parts means higher reliability than hard drives. But flash gradually loses charge over time, especially in unpowered states. Even in the best case, you need to power and rewrite data every few years to maintain it. SSDs excel for portable, powered applications. For long-term storage without power, they're less suited.

Glass storage sacrifices speed and rewritability for permanence. You write data once, then access it through optical reading, which is slow. You can't update what's stored without essentially rewriting the entire piece. But you get 10,000 years of data life without intervention. No maintenance. No power. No migration. Write it, seal it, forget it.

The right choice depends on the use case:

- Government archives, legal records, compliance data: Glass wins. You need this data to persist for decades or centuries, unchanged and immutable.

- Scientific datasets, cultural heritage: Glass makes sense. Data value increases over time as you can compare it to future observations.

- Active business databases: Hard drives. You need fast access and the ability to update constantly.

- Medium-term backups: Tape. Proven technology, good enough economics, acceptable maintenance burden.

- Portable computing: SSDs. No choice here really; tape and glass aren't portable.

What's interesting is where these boundaries blur. Some organizations might value glass storage for their most critical, rarely-accessed data. Government agencies definitely fall here. Research institutions possibly. But for most businesses, the economics and access patterns favour traditional media.

Borosilicate glass significantly reduces material costs for data storage, from ~

Parallel Writing: The Speed Breakthrough Nobody Expected

One bottleneck that seemed fundamental to glass storage was write speed. Sequential writing through glass volumes just isn't fast. You can only fire the laser so many times per second. To write a terabyte sequentially would take months or years.

Parallel writing changes the equation completely. If you have ten laser channels operating simultaneously, you write ten voxels at the same time. If you have a hundred channels (theoretically possible with current technology), you write a hundred voxels simultaneously. Suddenly, write speed becomes practical.

The challenge is coordinating multiple lasers, each with its own focusing optics and positional control, all writing into the same piece of glass without interference. The lasers can't interfere with each other. The focus points must be precisely controlled. The pulses must be timed correctly so they don't cause cumulative heating.

Research groups have demonstrated systems with multiple parallel channels. The bottleneck shifts from raw write speed to beam delivery and focus control. As these technologies mature, write speeds approach practical timescales. Where sequential writing might take a year for a terabyte, parallel systems could do it in days or hours.

This matters for commercialization more than you might expect. If writing is too slow, the service cost becomes prohibitive. You need to amortize the laser system, operator time, and facility cost over the data written. If you write one terabyte per month, costs are high per gigabyte. If you write one terabyte per day, costs per gigabyte drop dramatically.

Parallel writing is also where economies of scale kick in. Mass production of glass storage systems means designing them with many parallel channels from the start. Industrial laser systems can be manufactured cheaply at scale. The capital cost per unit of data written drops as throughput increases.

The Nature publication describes these parallel writing advances in detail. The optical design, the thermal management (multiple lasers create heat that must be managed so the glass doesn't crack), the synchronization challenges—all of it represents genuine engineering innovation, not theoretical physics.

Reading System Simplification: From Three Cameras to One

Earlier research prototypes needed three cameras positioned around the glass medium. Each camera captured a different optical view of the voxels, providing redundant information that helped the reading system figure out which voxels were written.

The new design works with a single camera. This seems like a small improvement until you think about the practical implications. One camera instead of three means the reading device is simpler, cheaper, and faster. You don't need to capture three separate images and correlate them. One pass captures sufficient information.

How does this work? The advancement relates directly to the phase voxel method used in borosilicate glass. The phase transition created by the single-pulse laser method creates distinct enough optical signatures that one camera, using different wavelengths or angles of illumination, captures sufficient information to read the data.

This might seem like an obvious engineering improvement, but it's significant. Reading devices get deployed in archives where they might sit for decades. Simpler systems are more reliable. Fewer optical components means fewer potential failure points. The maintenance burden drops.

Cost also decreases. An optical reading system with three cameras, three sensors, three sets of optics, costs substantially more than a single-camera system. For archival facilities serving many customers, this cost reduction matters.

There's a subtler advantage. Three cameras require careful calibration and alignment. Any misalignment reduces reading accuracy. One camera still needs alignment, but misalignment affects only one measurement axis, making it more forgiving. The reading system becomes more robust.

Glass storage becomes more economical than tape over long durations due to the elimination of recopying costs. Estimated data.

Manufacturing Implications: From Laboratory Curiosity to Industrial Process

Moving from fused silica to borosilicate glass has profound manufacturing implications. Fused silica production is specialized. Only a handful of manufacturers produce it, mostly for scientific and optics applications. Creating a new technology dependent on fused silica means either dealing with limited suppliers or building new production capacity.

Borosilicate glass is ubiquitous. Thousands of manufacturers produce it globally. The supply chain is mature. The manufacturing process is well-understood and optimized. This means new glass storage facilities could source their raw material through existing industrial channels.

The laser systems required for writing could be partially borrowed from laser manufacturing. Femtosecond lasers exist in industrial settings for precision cutting and welding. New glass storage devices would need specialized versions, but the core technology isn't exotic.

The environmental angle is interesting too. Borosilicate glass is recyclable. If a glass tablet breaks or reaches end-of-life (in a few thousand years?), it could theoretically be melted and reformed into new blanks. This creates a potential closed-loop system where storage doesn't generate electronic waste.

The practical manufacturing process for a glass storage factory would look something like this:

-

Glass preparation: Borosilicate glass blanks are produced through standard glass manufacturing or sourced from suppliers. Blanks are cut to specified dimensions and polished to optical clarity.

-

Data writing: Blanks are loaded into the writing system. Femtosecond lasers fire according to data patterns, creating voxels throughout the glass volume. The system uses parallel laser channels for speed.

-

Quality verification: Optical inspection confirms that voxels were created properly. Statistical samples are read back to ensure data integrity.

-

Packaging: Written glass is sealed in protective packaging (likely inert containers to prevent moisture or dust contamination) and labeled with metadata about what data is stored.

-

Storage and retrieval: Customers receive sealed tablets. When they need to access data, they use provided reading equipment or send tablets to reading facilities.

This is substantially simpler than traditional data center manufacturing. No complex electronics, no mechanical assembly, no sophisticated power distribution. Just lasers, glass, and optics.

The cost structure is interesting. The capital cost of a glass storage facility is dominated by the laser systems and optical equipment. The ongoing cost is mostly electricity and facility maintenance. The per-gigabyte cost depends heavily on throughput. Fast parallel writing drives the cost down.

Validation Through Accelerated Aging Tests

The claim that data lasts 10,000 years is bold. How do you validate this? You can't actually wait 10,000 years. The research uses accelerated aging tests, a technique well-established in materials science.

The principle is straightforward: expose samples to environmental extremes that simulate long-term degradation in accelerated time. Glass is primarily degraded by two factors: temperature and humidity. Increase these, and you can approximate centuries of natural aging in weeks or months.

The research team wrote glass samples and then subjected them to extreme temperature and humidity cycling. Temperature cycles ranged from below freezing to high heat. Humidity was pushed to saturation levels. The samples experienced conditions far harsher than they'd encounter in a normal vault.

After cycles equivalent to thousands of years of normal aging, samples were read to see if the data remained intact. The results showed negligible data loss. Some voxels might have degraded slightly, but error-correction coding (similar to what hard drives use) easily compensated. The data remained fully readable and intact.

This doesn't prove 10,000-year survival with absolute certainty. No accelerated aging test truly proves millennial durability. But it provides strong evidence that the glass is extremely stable. Historical comparisons are reassuring: borosilicate glass from laboratory equipment made in the 1800s is still optically perfect. If glass hasn't visibly changed in 150 years, the odds of dramatic change over the next 10,000 years are low.

There's theoretical support too. Glass is just disordered silica. The atomic bonds are strong. There's no oxidation (glass doesn't rust like metal). No electrical charge to lose (unlike flash memory). No mechanical wear (unlike hard drives). The material is chemically stable across geological timescales.

One caveat worth noting: the data longevity depends on the reading system existing to access it. If the technology was forgotten and no one had reading equipment, the data would still be intact in the glass, but inaccessible. This is why archival institutions are thinking about preserving documentation and open-source reading software alongside the physical media.

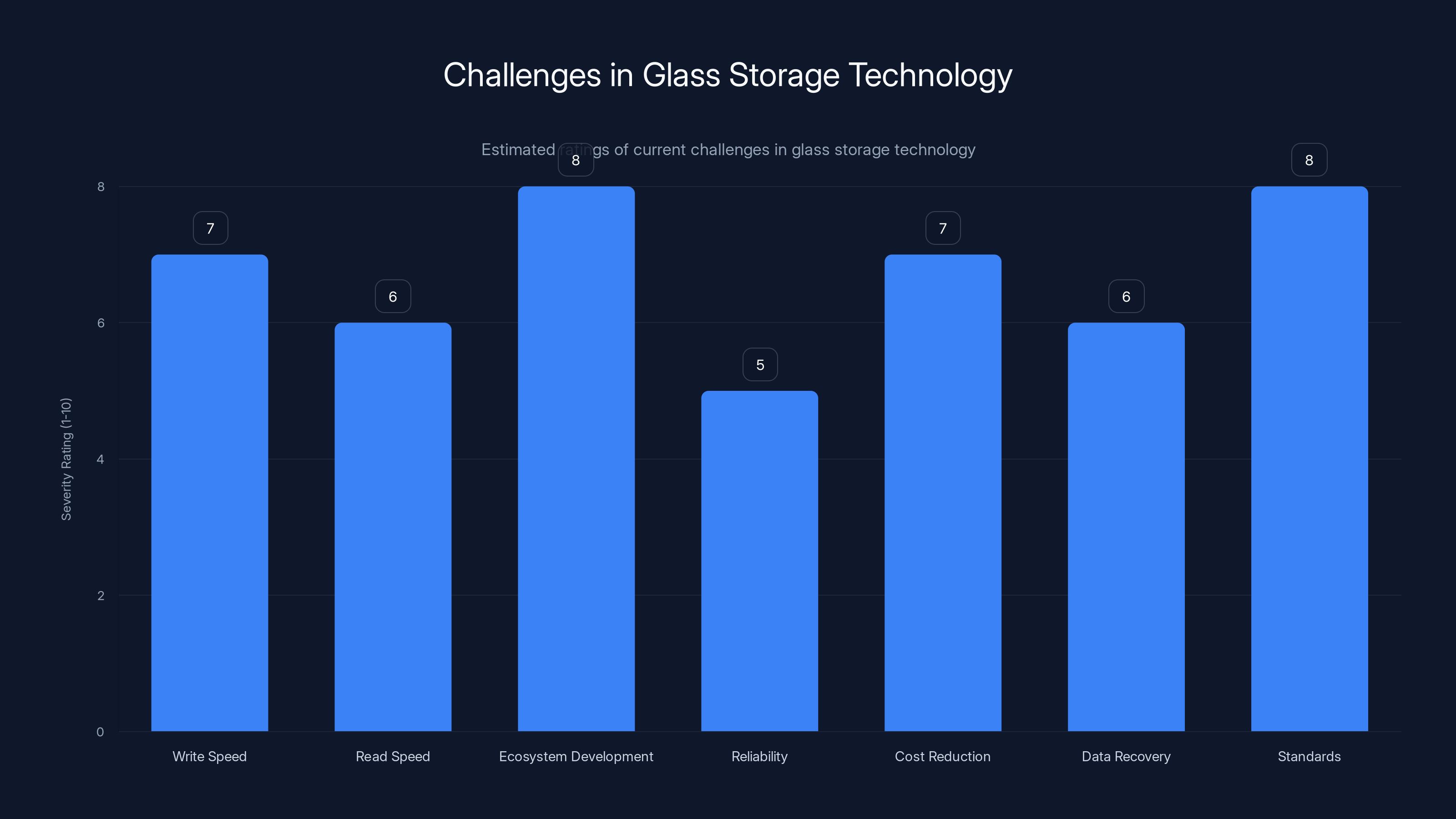

Ecosystem development and lack of standards are the most significant challenges in advancing glass storage technology. Estimated data.

Cost Analysis: When Does Glass Storage Become Economical?

The economic case for glass storage depends on several variables: the cost of writing equipment, the cost of the glass medium, the speed of parallel writing, and the value of data longevity.

Let's think through some numbers. A femtosecond laser system costs roughly

Glass blank cost is minimal. Borosilicate glass in bulk costs a few dollars per kilogram. A kilogram might hold hundreds of gigabytes of data (depending on voxel density). The material cost per gigabyte is fractions of a cent.

Now consider the write time. With sequential writing, a terabyte might take months. With parallel systems writing at high speed, a terabyte might take days. If you're writing one terabyte per day at

Compare this to tape storage, which runs roughly

Glass storage at $0.05 per gigabyte written once becomes competitive with tape when you factor in the elimination of future recopying. For data lasting centuries, glass becomes cheaper than tape.

But there's a catch. The initial write cost matters only if you're writing the data. The true economic advantage emerges for institutions preserving data for millennia. For most businesses, tape is still cheaper.

However, for certain applications—government archives, national treasures, scientific legacy data—the economics shift strongly toward glass. An institution preserving a petabyte of data for a thousand years probably spends less total money on glass storage than on tape migrations and management over that timeframe.

Another factor: immutability. Once data is written to glass, it cannot be modified or deleted. This is sometimes a bug (you can't fix mistakes). But it's often a feature (compliance, legal hold, preventing accidental data loss). Some organizations would pay a premium for this guarantee.

Real-World Applications: Where Glass Storage Is Already Relevant

Which institutions are actually exploring this? Who benefits first?

Government and regulatory bodies are obvious candidates. A nation's laws need to be preserved for future generations. Digital signatures, legislation, court records, census data—these are legally required to persist. Glass storage eliminates the archival burden. Write once, preserve forever.

The U. S. National Archives, the UK National Archives, similar institutions worldwide face this exact problem. Their digital collections are growing exponentially, but the preservation methods remain outdated. Glass storage is genuinely relevant to their mission.

Scientific institutions benefit enormously. Climate data from the 1970s is invaluable for understanding long-term climate trends. But the tapes are degrading and the equipment to read them barely exists. New climate data being generated now should be preserved so researchers 200 years from now can analyze it.

The same applies to genomic data, astronomical observations, physics experiments. Science builds on preserved data. Glass storage ensures that future scientists can access current observations without loss.

Cultural heritage is another compelling application. Museums, libraries, and archives hold humanity's accumulated knowledge. Much of this is being digitized. But where's it stored? On hard drives in climate-controlled rooms, praying nothing fails for the next 30 years. Glass storage would let museums preserve digital assets for the centuries that their physical artifacts have already survived.

Large enterprises with long operational histories might find value. A bank that's been operating for 200 years has historical records valuable beyond just business reasons. Archiving them to glass ensures they're preserved through whatever technological changes the next century brings.

Space exploration organizations see potential. NASA has talked about glass storage for backup copies of missions, historical data, and backup systems. The extreme radiation and temperature cycling in space would destroy traditional storage, but glass would survive.

The common thread: these applications prioritize preservation and immutability over access speed. They write data once and hope never to update it. They value certainty that data persists unchanged. These are exactly the conditions where glass storage shines.

The Remaining Challenges: What Still Needs Solving

Glass storage isn't market-ready today. Several challenges remain before this moves beyond research into deployment.

Write speed is improving but still slower than hard drives. Even with parallel channels, writing a large dataset takes meaningful time. This is acceptable for archives (which don't mind waiting weeks) but impractical for operational systems.

Read speed similarly lags. Optical reading through glass is slower than electronic reading from drives. For archive access (once per year, maybe), this is fine. For frequent queries, it's painful.

Ecosystem development hasn't happened yet. Where are the companies building commercial glass storage systems? Where are the standardized reading devices? The technology exists, but the industry hasn't formed. This is a chicken-and-egg problem: companies won't build products until demand exists, and demand won't exist until products exist.

Long-term reliability under real conditions still needs more evidence. Accelerated aging tests are strong, but the oldest glass storage samples are just a few years old. We have no real-world evidence of century-scale durability yet. This will come with time, but it's a genuine uncertainty.

Cost reduction through manufacturing optimization will happen, but we don't know the final price point. Will glass storage eventually cost

Data recovery from damaged glass needs refinement. If a tablet cracks, can you recover the data from fragments? In principle yes, but in practice, this needs tools and procedures that don't yet exist.

Standards don't exist. What's the standard size of a glass tablet? What's the standard voxel density? How is metadata encoded? What's the standard for error correction? Before widespread adoption, industry-wide standards are necessary.

Reading system availability is a future problem. If glass storage becomes widespread, future generations need to maintain reading systems. This requires preserving not just the glass, but the optical equipment and documentation. Libraries will need to maintain working optical readers and keep replacement parts available for decades or centuries.

These aren't fundamental physics problems. They're engineering and commercialization challenges. They're hard, but solvable.

Comparison to Other Experimental Storage Technologies

Glass isn't the only experimental storage approach being researched. How does it compare to alternatives?

DNA storage is another long-term preservation approach. DNA can store information extremely densely. A gram of DNA could theoretically store exabytes of data. And DNA is genuinely stable across millennia (fossilized DNA is still readable). The advantages are real.

But DNA storage faces challenges. Writing requires complex biochemistry. Reading requires sequencing, which is expensive and slow. Error rates are higher than glass. The technology is furthest from commercialization.

Molecular storage explores similar ideas: encoding data in molecules or atomic arrangements. Similar advantages and challenges to DNA.

Holographic storage writes data in three-dimensional patterns using coherent light. It offers high density and potential longevity. But it also requires complex optical systems and hasn't achieved clear advantages over simpler approaches.

Compare these to glass storage: glass is simpler than DNA, more mature than holographic storage, more practical than molecular approaches. It also uses existing materials and leverages existing laser technology. This makes glass storage the most likely to achieve practical deployment in the next 5-10 years.

Glass probably isn't the ultimate long-term storage technology. Something more exotic might emerge. But it's the best option available now with a clear path to commercialization.

Timeline: When Could Glass Storage Become Available?

If the research is complete, how long until you can actually use this technology?

Historically, it takes 3-7 years for lab research to become a commercial product. Sometimes faster for hype technologies, sometimes slower for specialized equipment.

For glass storage, the timeline likely looks like:

2026-2027: Universities and research groups develop specialized glass storage services for academic and scientific customers. This would be early-adopter territory: expensive, limited capacity, but available for researchers with critical data.

2027-2029: Companies begin commercialization. Likely this starts with archival service providers: companies that already manage archives add glass storage as a premium option. Building the equipment becomes someone's business.

2029-2032: Standardization efforts begin. Industry groups attempt to establish standards for glass storage format, voxel density, metadata encoding, and reading system specifications. This is crucial for interoperability and prevents vendor lock-in.

2032+: Wide availability. By this point, glass storage is available from multiple vendors at competitive prices. Government agencies, museums, and large enterprises can access it routinely.

This timeline assumes successful commercialization with no major obstacles. Delays are easily possible if technical challenges emerge or if demand fails to materialize.

One wildcard: Microsoft's role. As the research originator, Microsoft might commercialize this itself (through Azure or a new division) or license it to established archival companies. The path they choose significantly affects timeline and availability.

Strategic Implications for Data Centers and Archives

If glass storage becomes practical and affordable, it reshapes data center strategy. What does this mean for organizations managing critical data?

Tiered storage becomes more explicit. Currently, tiered storage means: hot storage (fast, expensive, frequently accessed) on SSDs, warm storage (medium speed, cost, occasional access) on hard drives, cold storage (slow, cheap, rarely accessed) on tape. Glass storage becomes the ultimate cold storage tier: write once, never touch again, 10,000 years preservation.

Compliance becomes simpler. Regulations often require data preservation for defined periods. Glass storage enables perfect compliance: write data, seal it, forget it. No refreshing, no migrations, no "what if a drive fails?" anxiety.

Strategic preservation shifts. Institutions move from defensive archival (preserve what we have and hope it survives) to proactive preservation (intentionally write critical data to glass for certain survival).

Data governance changes. The inability to modify or delete glass-stored data forces explicit decisions about what to preserve. You can't write everything to glass—it's for conscious archival decisions. This clarity is healthy.

Future-proofing becomes realizable. Currently, long-term data preservation is always a bet. You preserve it on what you think is permanent media, hoping future generations care enough to keep it readable. Glass storage actually achieves permanence.

For institutions whose mission includes preservation—government, science, culture—these implications are profound.

The Broader Context: Why Preservation Matters

Why should anyone care about data lasting 10,000 years? That's absurdly far in the future. What use is data that far away?

The question is fair, but it misses the context. Institutions that preserve knowledge do so not for their own convenience, but as a service to future generations. The Library of Congress isn't just for today's researchers. It's for researchers in 2125, 2225, and beyond.

Consider what we'd know about ancient Rome if they had preserved more data. How much medieval knowledge was lost when libraries burned? How much scientific progress was delayed by missing historical observations?

Present knowledge serves future knowledge. Climate science requires data from decades past to establish trends. Genomics requires preserved samples from previous generations. Physics builds on previous experiments. Every field of knowledge depends on historical data.

Digital information is particularly fragile. We're creating more data than ever before, but storing it more precariously. Hard drives fail. Companies shut down. File formats become obsolete. Within 50 years, much of what we create digitally today will be inaccessible or lost.

Glass storage addresses this at a fundamental level. It's not about storing video files or music. It's about cultural continuity. It's about ensuring that what matters today remains understandable tomorrow.

This is why government agencies and scientific institutions care about 10,000-year preservation. They're thinking in terms of civilizational timescales, not quarterly earnings.

Future Directions: Beyond Glass Storage

If glass storage succeeds, what comes next?

One possibility: integration with other technologies. Imagine glass storage coupled with standardized metadata and indexing. Organizations could write entire datasets to glass with searchable indexes. The reading system could become specialized and optimized rather than general-purpose.

Another: extreme environments. Space applications would benefit enormously. Mars colonies, deep space probes, off-world bases—these environments are harsh to traditional electronics but benign for glass. Sealed glass tablets could preserve data for centuries in the harshest conditions.

Multi-modal archival: glass storage for critical data, combined with redundant paper documentation (yes, paper still lasts centuries) and open-source software for reading. This creates multiple paths to future recovery even if glass reading technology were somehow lost.

Quantum storage: though purely speculative, glass might someday support quantum data storage, offering both preservation and quantum computational benefits.

The broader question: could this approach be applied to other permanent-record needs? Could crucial software be preserved in glass? Could architectural designs for critical infrastructure be stored for future reconstruction? The principle applies far beyond numeric data.

FAQ

What is Project Silica and how does it work?

Project Silica is Microsoft Research's technology for encoding digital data into borosilicate glass using femtosecond lasers. The system fires extremely brief laser pulses to create microscopic zones of modified glass (called voxels) that have different optical properties than surrounding glass. These voxels represent binary data. A camera detects the differences in how light passes through the glass to read the encoded information back. The data is written into the three-dimensional structure of the glass itself, making it extremely permanent and requiring no power to maintain.

How long can data actually last in glass storage?

Accelerated aging tests suggest data remains intact after aging equivalent to at least 10,000 years under natural conditions. The research exposed glass samples to temperature and humidity extremes that simulate centuries of degradation in just weeks. After this accelerated aging, data remained fully readable. Borosilicate glass has been used in laboratory equipment since the 1800s with no visible degradation, supporting confidence in millennial-scale preservation. However, absolute proof of 10,000-year durability will only come with actual passage of time.

Why did Microsoft move from fused silica to borosilicate glass?

Fused silica, the original material, is expensive (hundreds of dollars per kilogram) and available only from specialized suppliers. Borosilicate glass costs roughly 10-20 times less and is produced globally for countless applications. This shift moved the technology from laboratory curiosity to economically viable. Additionally, breakthrough research developed the "phase voxel method" that works specifically with borosilicate glass properties, enabling faster writing with a single laser pulse instead of multiple pulses, further improving practical feasibility.

What are the advantages of glass storage compared to hard drives or tape?

Glass storage offers extreme permanence (10,000+ years without degradation), no maintenance requirements, no power consumption for preservation, immunity to water and dust, and immutability (data cannot be accidentally modified). Hard drives fail within 8-10 years and require maintenance. Tape survives 30-50 years but requires climate control and periodic media refreshing. Glass storage sacrifices write and read speed compared to both alternatives but eliminates the ongoing burden of data migration that makes long-term tape storage expensive.

Can glass storage data be erased or modified?

No. The technology is Write Once, Read Many (WORM). Data written to glass cannot be modified or erased without destroying the entire tablet. This is a limitation for operational systems but a feature for archival and compliance applications where immutability is valuable. If mistakes are discovered after writing, they're permanent—so careful validation before writing is essential.

What is a femtosecond laser and why is it necessary?

A femtosecond laser fires pulses lasting just one quadrillionth of a second. This extreme brevity allows the laser to concentrate enormous energy in a tiny spot and brief moment, creating microscopic structural changes in glass without melting or damaging the material. Longer laser pulses would heat the glass excessively; femtosecond pulses allow precise, localized changes at the microscopic level needed for data storage.

When will glass storage be commercially available?

Research suggests commercial glass storage services could emerge from universities and specialized companies by 2027-2029, with broader availability by 2032+. Initial costs will be high, targeting institutions that can afford premium pricing for perfect preservation. As manufacturing scales and competition increases, costs will decline. However, timeline estimates are speculative; technical obstacles or lack of market demand could delay commercialization significantly.

How is data actually written and read from glass storage?

Writing involves a femtosecond laser firing thousands of times per second, each pulse creating a voxel at a specific location in three-dimensional space. Motorized stages position the laser focus to build up a lattice of voxels throughout the glass volume. Reading requires optical equipment that illuminates the glass and captures how light is modified by the voxels. A camera records these patterns, and software analyzes them to reconstruct the original data. Parallel laser systems enable faster writing by simultaneously writing multiple voxels in different regions of the glass.

What organizations would benefit most from glass storage?

Government agencies preserving legal records and legislative documents, scientific institutions archiving research data and observations, cultural heritage organizations preserving digital museum collections, national libraries and archives, space agencies preserving mission data, and companies with century-scale operational histories. Any organization whose data must remain readable and unchanged for decades to centuries benefits from glass storage's permanence and lack of maintenance burden.

What challenges remain before glass storage becomes widespread?

Key challenges include write speed improvement, standardization of formats and reading systems, cost reduction through manufacturing optimization, ecosystem development (companies building products and services), establishment of industry standards, preservation of reading technology documentation for future generations, and accumulation of real-world evidence beyond laboratory tests. Additionally, reading systems remain slower than traditional media, which is acceptable for archives but impractical for frequently accessed data.

How does glass storage compare to other experimental preservation technologies like DNA storage?

Glass storage is further along toward commercialization than competing approaches. DNA storage offers extreme density but requires complex biochemistry for writing and expensive sequencing for reading. Holographic storage requires complex optical systems. Molecular storage is still largely theoretical. Glass storage uses existing laser technology, common materials, and relatively straightforward optical reading. This makes glass the most likely to become practically available within 5-10 years, though other technologies might eventually prove superior for specific applications.

The Path Forward

Project Silica represents something rare in technology: a genuine solution to a real, long-standing problem. Digital preservation has challenged institutions for decades. Hard drives fail. Tape degrades. File formats become obsolete. Data loss is nearly inevitable over centuries.

Glass storage changes the equation. It doesn't require electricity. It doesn't degrade. It doesn't need refreshing. Write it and seal it. Centuries later, if someone wants to know what you preserved, they'll be able to find out.

The breakthrough from fused silica to borosilicate glass is crucial because it makes the technology economically viable. Parallel writing improvements make write times practical. Reading system simplification reduces cost and complexity. The phase voxel method enables all of this with a single laser pulse instead of multiple pulses.

We're approaching a moment where glass storage transitions from research curiosity to practical tool. The timeline is uncertain—commercialization could take 3 years or 15 years—but the direction is clear.

For institutions whose mission includes preservation, Project Silica deserves attention. The technology works. The materials are available. The physics is sound. What remains is engineering, standardization, and commercialization.

Ten thousand years is longer than human civilization has existed. We don't know what knowledge our descendants will need. But we can ensure they have access to what we think matters. Glass storage makes that possible.

Key Takeaways

- Glass storage preserves data for 10,000+ years without degradation, addressing the long-standing crisis of digital archival and information loss

- The breakthrough from expensive fused silica to ordinary borosilicate glass makes the technology economically viable and scalable

- Parallel laser writing and single-camera reading systems dramatically simplify the technology and reduce manufacturing complexity

- Write-once, read-many architecture makes glass storage ideal for archives, compliance, and cultural preservation but impractical for active databases

- Commercialization timeline suggests glass storage services emerging by 2027-2029, with broader availability following standardization by 2032+

Related Articles

- Metal Gear Solid 4 Leaves PS3: Console Exclusivity Death [2025]

- Wayback Machine Link Fixer Plugin: Fixing Internet's Broken Links [2025]

- Adobe Reverses Animate Discontinuation: What It Means [2025]

- Why Publishers Are Blocking the Internet Archive From AI Scrapers [2025]

- Reviving Anthem After Server Shutdown: Why EA's Frostbite Engine Makes It So Hard [2025]

- Spotify's Secret Court Order Against Anna's Archive [2025]

![Project Silica: Glass Data Storage for 10,000 Years [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/project-silica-glass-data-storage-for-10-000-years-2025/image-1-1771432757762.jpg)