NASA Astronauts Can Now Take Smartphones to Space: A Game-Changer for Orbital Imaging [2025]

Introduction: When Personal Devices Meet Orbital Exploration

For decades, astronauts have been the ultimate digital minimalists. While the rest of us obsess over leaving our smartphones behind for even a few hours, space explorers have had no choice but to launch into the cosmos without their most trusted devices. That era just ended.

In a groundbreaking policy shift, NASA announced that astronauts aboard the upcoming Crew-12 and Artemis II missions will be allowed to bring personal smartphones into space. This isn't just about keeping in touch with family from 250 miles above Earth. It's a fundamental reimagining of how we document humanity's greatest frontier.

For context, astronauts have traditionally relied on specialized, ruggedized cameras designed to withstand the extreme conditions of spaceflight. These devices are expensive, bulky, and require training to operate effectively. They're also singular in purpose. A smartphone, by contrast, is a Swiss Army knife of documentation. It can capture photos, record videos, adjust lighting on the fly, and instantly process images using computational photography techniques that professional cameras from even five years ago couldn't match.

The decision reflects a broader truth about modern technology: consumer devices have become so sophisticated that they rival or exceed specialized equipment in many scenarios. When you're orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour, spontaneity matters. The smartphone in your pocket can capture that perfect shot of your home continent in ways that a pre-planned camera setup simply cannot.

NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman framed the policy in terms of human connection. "We are giving our crews the tools to capture special moments for their families and share inspiring images and video with the world," he said. This simple statement masks a profound shift in how space agencies think about their missions. Space exploration is no longer just about scientific data collection and mission objectives. It's about storytelling, inspiration, and bridging the gap between Earth and the cosmos.

But this decision didn't emerge from nowhere. It's the culmination of years of innovation, testing, and a growing recognition that smartphones have become legitimate instruments of space documentation. Understanding how we arrived at this moment, what it means for future missions, and how technology will evolve in this new era requires a deep dive into the history, implications, and future of smartphones in space.

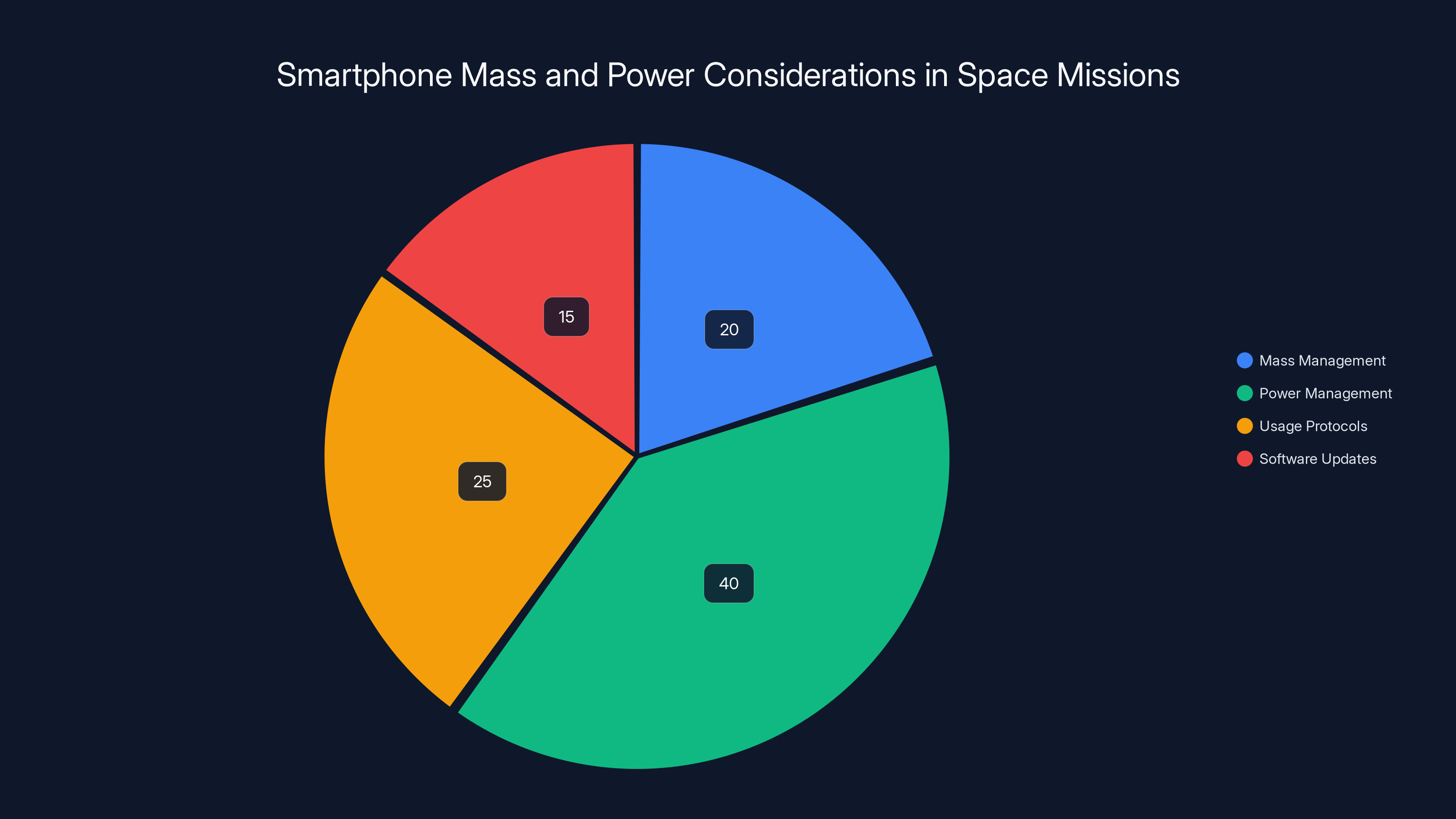

Power management is the most significant constraint for smartphone usage in space, accounting for 40% of the considerations, followed by usage protocols and mass management. Estimated data.

TL; DR

- Policy Shift: NASA now allows astronauts on Crew-12 and Artemis II to bring personal smartphones to space for personal documentation

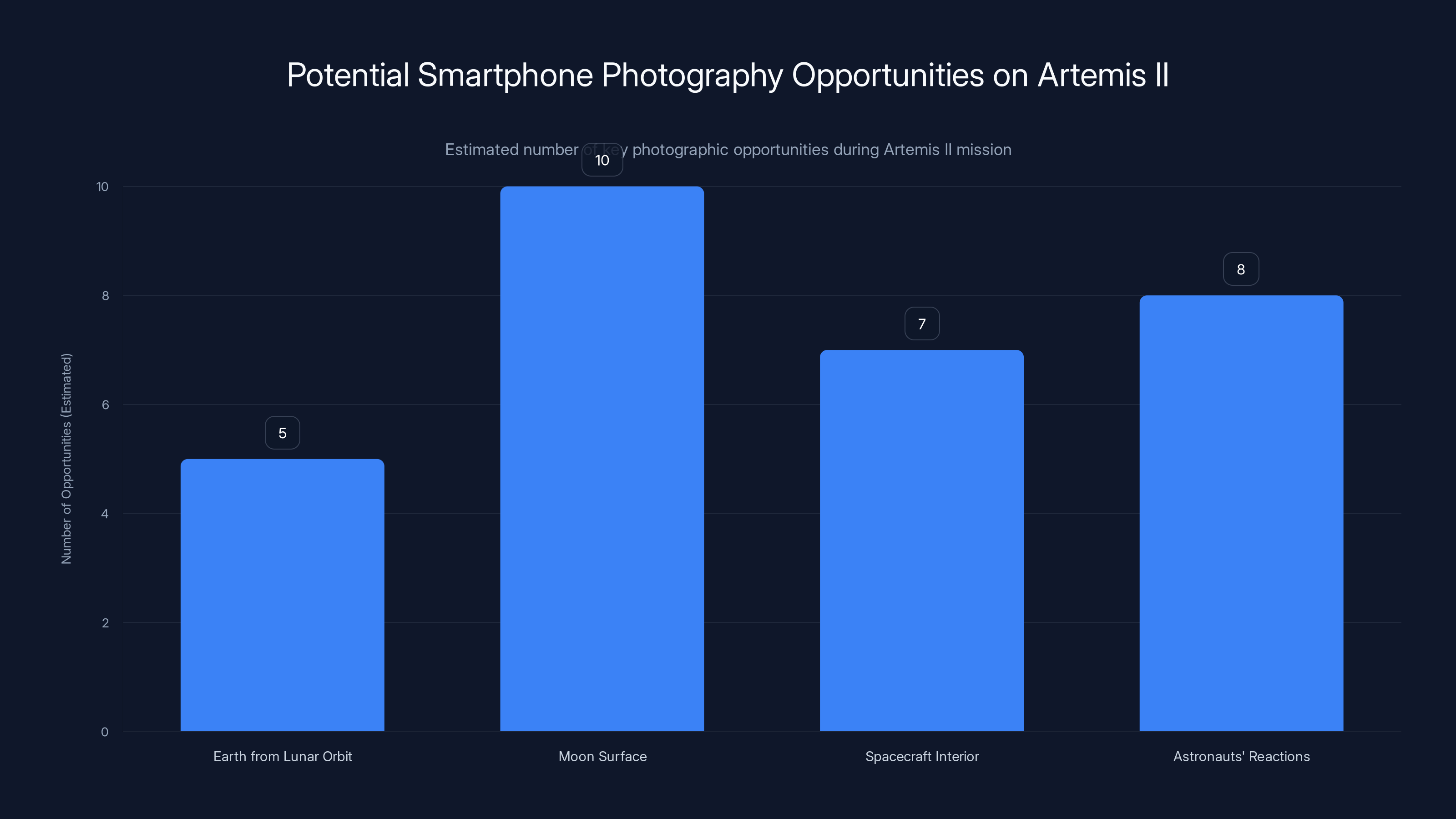

- First Moon Images: Artemis II will produce the first smartphone images from lunar orbit, marking a historic milestone in space photography

- Practical Advantages: Modern smartphones offer superior computational photography, portability, and spontaneous capture compared to traditional space cameras

- Family Connection: The policy prioritizes astronaut experiences and allows real-time sharing of cosmic imagery with loved ones

- Future Implications: This decision could influence how subsequent missions, private space ventures, and international space programs approach documentation

Why NASA Finally Made This Call: The History of Space Photography

To understand why this policy matters, you need to know what astronauts have been working with. Since the beginning of human spaceflight, space agencies have approached photography with the same meticulous precision they apply to every other aspect of missions.

During the Apollo program, astronauts carried Hasselblad cameras, mechanical devices that could survive the vacuum of space without electronic complications. These cameras were legendary in their simplicity and durability. Buzz Aldrin's iconic photos of Neil Armstrong on the lunar surface? Shot with a Hasselblad 500EL. For decades, these became the gold standard for space photography.

But film-based cameras present obvious limitations. You can't review your shots. You can't delete bad takes. You can't adjust exposure on the fly. You're essentially flying blind, hoping that your pre-planned compositions and exposure calculations work out. And yet, the quality of those images was extraordinary, partly because photographers were forced to be intentional and methodical.

The shift to digital came gradually. Agencies like NASA developed specialized digital cameras that could withstand radiation, extreme temperatures, and vacuum conditions. These weren't consumer devices. They were engineered from the ground up for space, often costing hundreds of thousands of dollars each.

Here's the thing though: modern smartphones have computational photography built in. They use multiple sensors, advanced algorithms, and artificial intelligence to correct exposure, enhance detail, and produce results that would require a professional photographer with decades of experience just twenty years ago. An iPhone 15 or Samsung Galaxy S24 can rival or exceed equipment that cost fifty times as much a decade ago.

The turning point came from unexpected sources. In 2013, three experimental small satellites based on smartphone components were launched into Earth orbit. These miniaturized phone-based satellites, part of the Phonesat 2.5 program, proved that smartphone technology could not only survive in space but could produce surprisingly good images. This wasn't entirely new ground—the British STRaND-1 had attempted something similar earlier, but that project encountered technical difficulties.

These successful demonstrations planted a seed. If smartphone components could function in space, why not the devices themselves? NASA engineers began testing personal smartphones under simulated space conditions: vacuum chambers, radiation exposure, extreme temperature fluctuations. The results showed that while smartphones aren't specifically hardened for space, they could function reliably on relatively short missions, particularly in the relatively protected environment of a spacecraft or station interior.

By the time Jared Isaacman took over as NASA Administrator in 2024, the technology had advanced enough and the case was compelling enough. Astronauts wanted better documentation tools. Families wanted to see real, unfiltered images from space. The public wanted more authentic cosmic imagery. And the technology was finally ready.

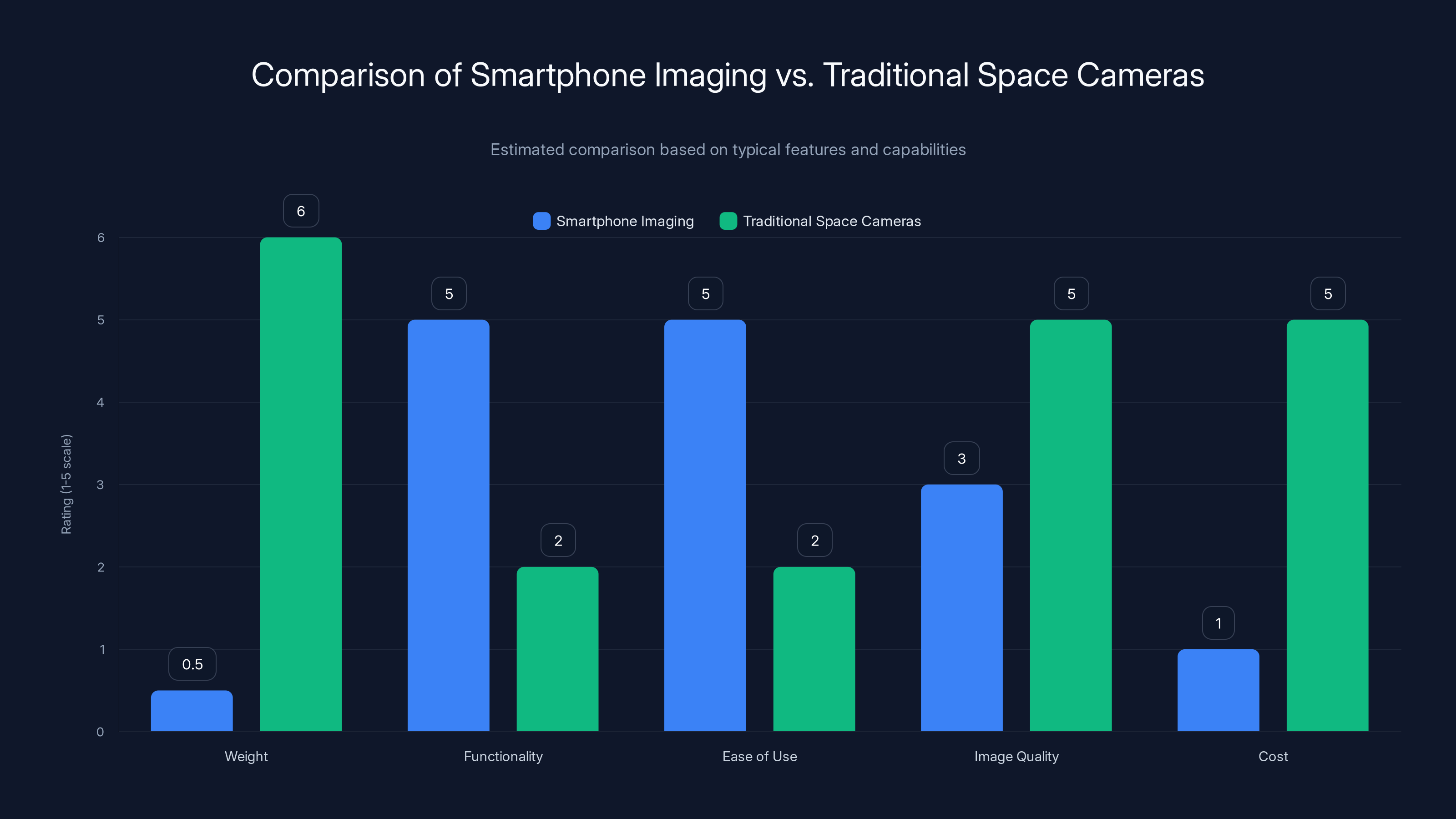

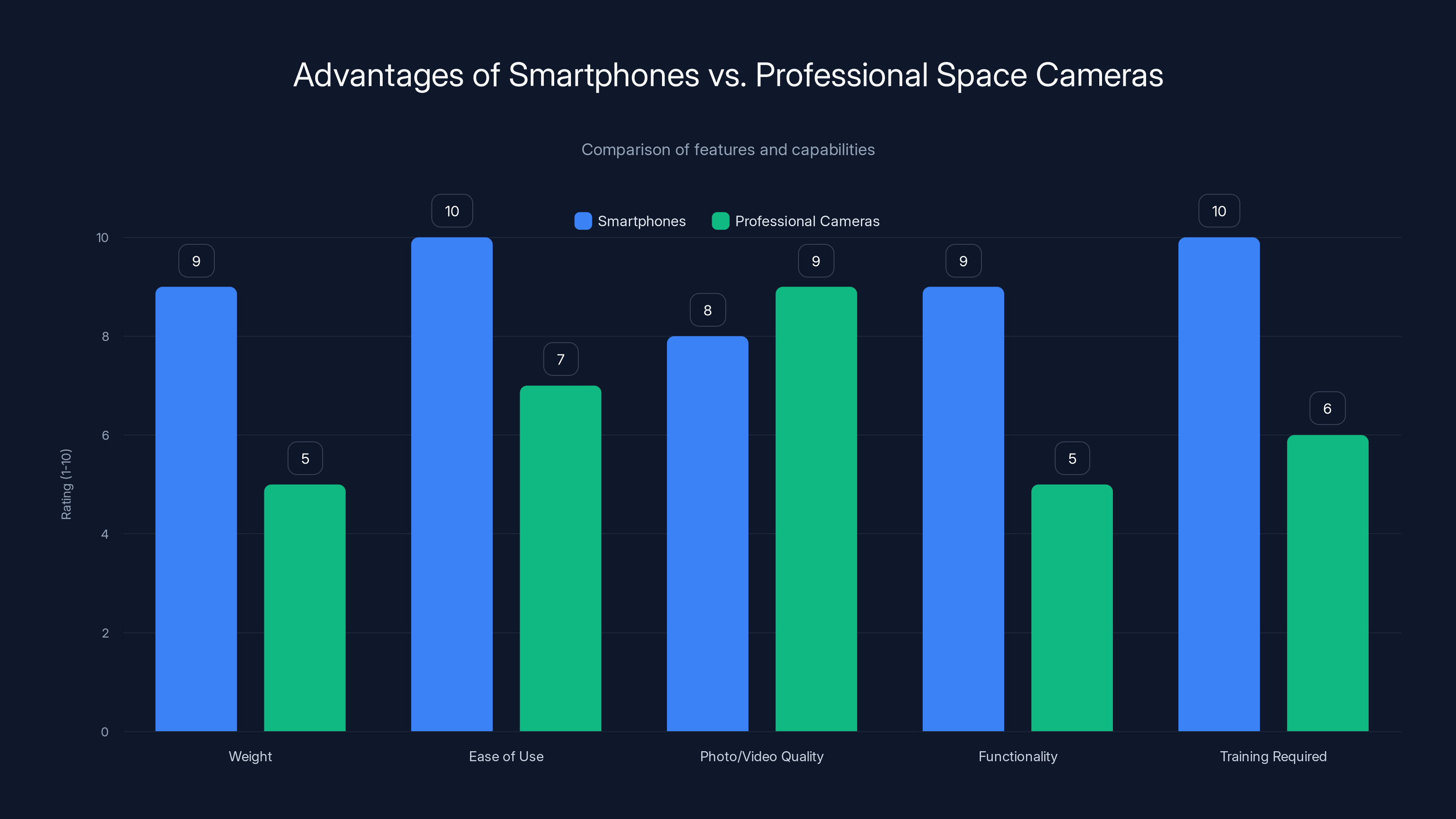

Smartphones excel in multifunctionality and ease of use, while traditional space cameras offer superior image quality and control. Estimated data.

Understanding the Technical Challenges: How Smartphones Will Actually Work in Space

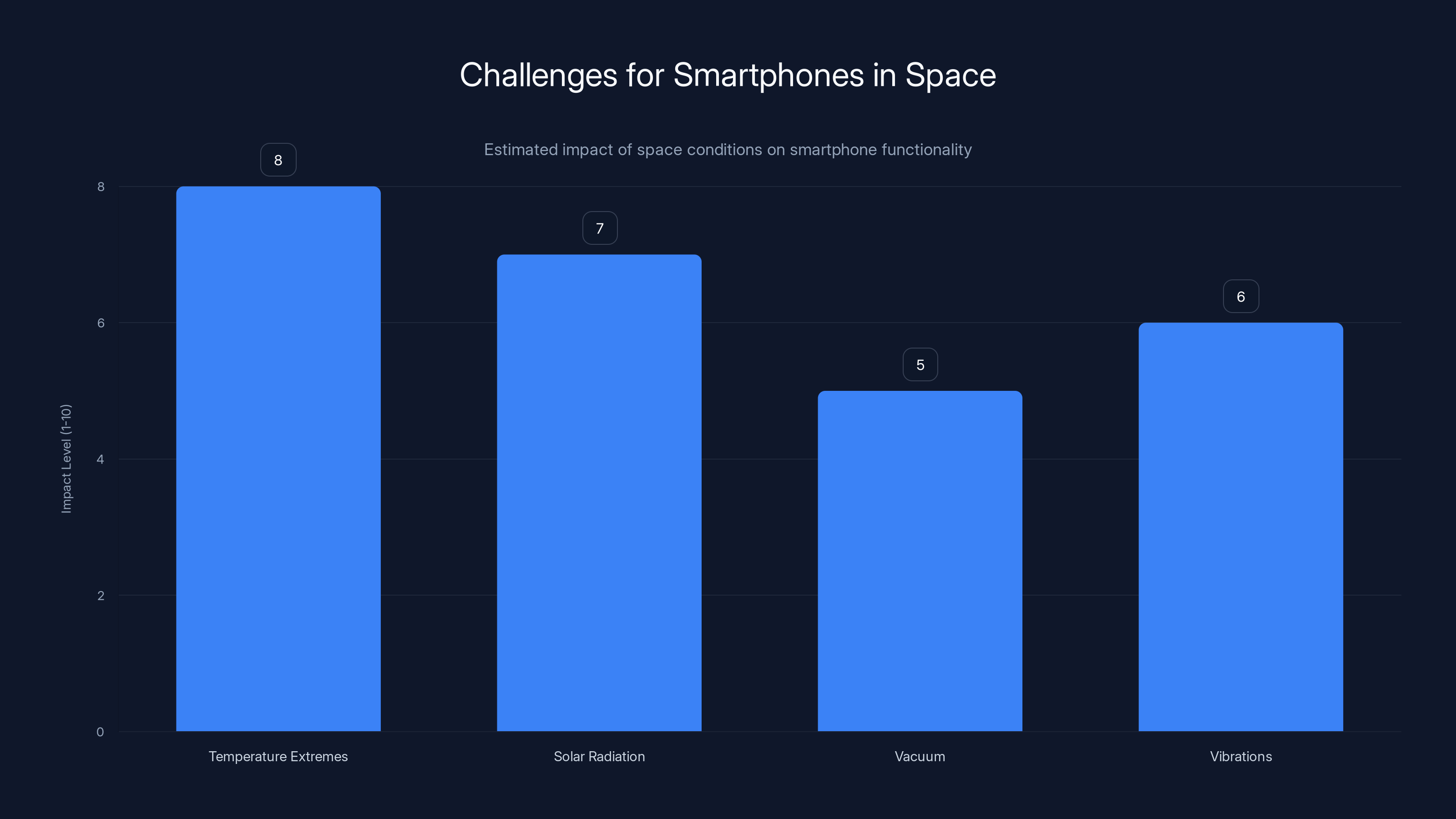

Bringing a smartphone to space seems straightforward until you think about what space actually does to electronics. The environment 250 miles above Earth is catastrophically hostile to most human technology. Temperatures swing from 250 degrees Fahrenheit in direct sunlight to 250 degrees below zero in shade. Solar radiation, unfiltered by an atmosphere, bombards everything. The vacuum means no convective cooling, no air pressure to help components function normally.

Here's where mission planning becomes crucial. Astronauts won't just throw their iPhones into a locker and hope for the best. The phones will remain inside the spacecraft, where environmental controls maintain reasonable conditions. Inside the International Space Station or a crew module, temperatures stay around 70 degrees Fahrenheit, pressure remains at Earth-normal levels, and radiation exposure is significantly reduced compared to open space.

This is the key insight: NASA isn't asking smartphones to survive in the vacuum. It's asking them to survive in an environment that, while different from Earth, isn't fundamentally incompatible with consumer electronics. The spacecraft essentially creates a protective bubble that allows consumer devices to function.

But there are still challenges. Solar radiation is higher in space than on Earth's surface, even with atmospheric shielding. High-energy particles can cause bit errors in memory systems. Repeated radiation exposure can degrade semiconductor performance over time. For short missions, these effects are negligible. For longer-duration stays, they become more significant.

This is why the initial rollout focuses on specific missions. Crew-12, launching from Earth, will have relatively short transit times and relatively benign radiation environments. Astronauts will have their phones in protective cases during launch and reentry, when vibrations and accelerations could damage delicate components. Once in orbit, phones can be used more freely.

Artemis II presents more interesting challenges. The spacecraft will travel beyond Earth's protective magnetosphere toward the Moon. Radiation exposure will be higher. Transit times will be longer. The lunar environment outside the spacecraft is even more hostile than Earth orbit. But again, astronauts will remain inside a protected capsule during most of the mission. The brief periods when they might use phones outside would be limited or nonexistent on this particular mission.

Modern smartphones are also more robust than many people realize. They're already designed to withstand significant radiation exposure—the chips inside phones are manufactured at scales small enough that radiation hardening becomes important. The cameras in phones use CMOS sensors, which are actually more radiation-tolerant than some other sensor types. Battery management systems have redundancy built in to prevent catastrophic failures from single-point radiation events.

NASA's testing probably included placing phones in vacuum chambers, exposing them to cosmic radiation simulation, subjecting them to temperature extremes, and verifying that sensors and cameras still function correctly afterward. If that testing confirmed basic reliability, then the environmental controls inside a spacecraft can handle the rest.

The Crew-12 Mission: First Smartphones in Orbit

The Crew-12 mission represents the initial test case for NASA's new smartphone policy. While specific launch dates shift, this mission would represent the first time that personal devices accompany astronauts into orbit as primary documentation tools.

Crew-12 is a relatively standard orbital mission. A SpaceX Dragon spacecraft will carry four astronauts from Earth to the International Space Station, where they'll spend approximately six months conducting experiments, maintaining station hardware, and performing various scientific tasks. During that six-month period, they'll have access to smartphones for personal use.

This creates interesting precedent questions. Will the phones be used during official experiments? Probably not initially. Will there be restrictions on what astronauts can photograph? Likely some guidelines around sensitive facilities or classified work. Will the phones be connected to internet? That's complex—the ISS has communication systems, but bandwidth is limited and prioritized for scientific and mission-critical uses.

What's particularly interesting is the documentation this opens up. Imagine astronauts capturing candid photos during their personal time: sunrise over Earth, colleagues working together in microgravity, the view from the cupola—the observation window that provides unparalleled views of our planet. These aren't official mission photographs. They're personal documentation that captures the human experience of spaceflight.

From a practical standpoint, Crew-12 astronauts will probably follow guidelines about when and where they can use phones. During critical operations, phones will be secured. During private time, they'll have more freedom. The phones will remain powered by the station's electrical systems—or more likely, by specially-equipped battery packs that don't rely on full Earth gravity to function normally.

The data from Crew-12 missions will be invaluable. NASA will document which phone models survived the most telemetry errors, which cameras performed best, what kinds of images were actually captured, and whether any unforeseen issues emerged. This real-world testing will inform policies for subsequent missions.

One practical consideration: phones will need to be secured during launch and reentry. The vibration and acceleration during these phases could damage delicate components. They'll probably remain in protective cases stored securely until the spacecraft reaches orbit and settles into microgravity. Similarly, phones will need to be stowed and secured before reentry procedures begin.

Battery management becomes more complex in microgravity. Batteries are designed to function in Earth's gravity, where convection helps manage heat dissipation. In orbit, passive heat management becomes more important. Phones may charge more slowly or dissipate heat less efficiently. NASA's testing probably included thermal monitoring of phones charging in simulated microgravity conditions.

Artemis II and the Historic Moon Images: Smartphones at 238,900 Miles

But here's where the policy gets truly transformative: Artemis II. This mission will be the first crewed lunar voyage since Apollo 17 in 1972. It will carry astronauts beyond Earth orbit, to the Moon, and back—without landing this time, but orbiting close enough to photograph the lunar surface in detail. And it will be the first time smartphones accompany humans to the Moon.

Let that sink in for a moment. We're potentially looking at the first smartphone images of Earth from lunar orbit. The first photographs of the Moon's surface captured by an iPhone or Samsung Galaxy. The first candid, spontaneous documentation of the human experience of leaving Earth's neighborhood and traveling to another world.

Artemis II's schedule has shifted multiple times, but the mission profile is clear. A Space Launch System rocket, one of the most powerful launch vehicles ever built, will send a crew of four astronauts in an Orion spacecraft on a multi-day journey to lunar orbit. They'll spend several days in orbit, performing scientific observations and testing various systems. Then they'll return to Earth, splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.

This mission involves greater challenges than Earth orbit operations. The transit itself exposes astronauts to higher radiation levels as they move beyond Earth's magnetosphere. The spacecraft is smaller and more confined than the International Space Station. Life support must be completely self-contained—there's no opportunity to dock at a station and resupply.

But the photographic opportunities are extraordinary. Astronauts will see Earth from distances humans rarely experience. They'll photograph the Moon in detail, seeing features and landscapes that only Apollo astronauts have seen in person. They'll capture the black sky of space, unfiltered by atmospheric scattering. They'll document their reactions and emotions as they become some of the first humans to return to lunar space in over fifty years.

From a technical standpoint, smartphone cameras are particularly well-suited to lunar imaging. Moon photographs require significant contrast management—the Moon is simultaneously very bright and very dark, with extreme shadows. Modern smartphones have computational photography systems that can handle these extreme contrasts far better than traditional cameras. Multi-frame exposure blending, tone mapping, and AI-based detail recovery can produce stunning lunar images from relatively simple smartphone sensors.

The photographs from Artemis II will almost certainly be different in character from Apollo-era photography. Apollo photographs were often meticulously planned, taken by trained photographers with specific objectives. Artemis II smartphone images will be more immediate, more human, more emotionally resonant. They might capture astronaut surprise, joy, or awe in ways that formal mission photography cannot.

There's also an interesting question about resolution and quality. Modern smartphone cameras have optical zoom capabilities and computational zoom techniques that can produce surprisingly detailed images. A high-end smartphone from 2025 could potentially capture lunar surface details that would have required specialized equipment a few years ago. The image processing that happens automatically in a smartphone—noise reduction, sharpening, color correction—produces images that are immediately usable without post-processing, unlike raw photos from professional cameras.

Archival is another important consideration. These images will be historic records of the Artemis II mission. Likely, NASA will have protocols for downloading and archiving all smartphone photographs taken during the mission. Those images will become part of humanity's official space exploration archive, sitting alongside the Hasselblad photographs from Apollo and the professional images from decades of shuttle and station operations.

Estimated data shows temperature extremes and solar radiation as the most significant challenges for smartphones in space, while vacuum and vibrations also pose notable risks.

The Smartphone Camera Revolution: Why They're Ready for Space

Understanding why NASA felt confident allowing smartphones in space requires understanding how dramatically smartphone camera technology has evolved. This isn't about putting consumer devices into inappropriate environments. It's about recognizing that consumer devices have become sophisticated enough to compete with specialized equipment.

In 2015, smartphone camera resolution plateaued around 12 megapixels. Manufacturers realized that more megapixels don't automatically mean better photographs. Instead, they began investing in computational photography—the use of algorithms to combine multiple exposures, denoise images, and artificially enhance detail and color.

Today's flagship smartphones have multiple camera systems: ultra-wide cameras for expansive landscapes, telephoto cameras for distant objects, macro cameras for close-up work, and specialized depth sensors for bokeh effects. Each camera has its own optical advantages. The software that manages these cameras can switch between them automatically based on what it detects in the scene.

But more importantly, smartphone cameras now use machine learning to improve results in real-time. When you take a photo in low light, your phone probably uses computational night mode—it captures multiple frames and intelligently combines them, essentially seeing in the dark better than human eyes can. When you photograph a person, it applies computational portrait mode, intelligently detecting the background and blurring it while keeping the subject sharp.

For space photography, these computational systems are tremendously valuable. The extreme contrast of space—brilliant sun-lit objects against the absolute black of space—creates challenges that computational photography is specifically designed to handle. A smartphone can take multiple exposures and blend them, handling both highlights and shadows in ways that would require professional post-processing on traditional cameras.

The zoom capabilities of modern smartphones are also more capable than people realize. While optical zoom is limited by physical lens size, digital zoom combined with computational techniques can often produce surprisingly good results. Some flagship phones use periscope-style zoom systems that provide true multi-megapixel zoom capabilities.

Video is another dimension where smartphones have become remarkably capable. Professional video production has shifted partly toward smartphone-based workflows because the video quality is so good. The stabilization, color science, and dynamic range management in smartphone video rivals professional cinema cameras from ten years ago. For documenting the Artemis II mission, video from astronauts will be able to capture experiences in ways that still photography cannot.

Battery capacity is probably the most limiting factor for space use. Smartphones are designed for all-day use on Earth, with typical battery life measured in hours. In space, astronauts will need to manage battery carefully, charging phones whenever possible. But this isn't a fundamental limitation—it's just a resource management challenge. And space missions are built around resource management. Astronauts already carefully manage water, oxygen, food, and other consumables. Managing smartphone battery life will integrate into existing life support and resource planning procedures.

Thermal management is another consideration. Smartphone processors and cameras generate heat, which dissipates more slowly in microgravity. But spacecraft have active cooling systems, and astronauts can manage phone usage to prevent thermal problems. This is more of an operational constraint than a fundamental technical limitation.

Comparing Smartphone Imaging to Traditional Space Cameras

To appreciate why NASA felt confident with this policy shift, it's useful to compare smartphone capabilities directly with the specialized cameras that astronauts have traditionally used.

Traditional space cameras are designed with specific priorities: durability, radiation resistance, and output quality. They're often variants of high-end professional cameras, with modifications to survive the space environment. These cameras typically weigh between 3 and 8 pounds fully equipped, require training to operate, and feature manual controls that allow photographers to adjust exposure and focus deliberately.

The advantages of traditional space cameras are significant. They produce extremely high-resolution raw image data that can be post-processed extensively. They have excellent color science calibrated for space photography. They offer full manual control, which is valuable when you're in an environment where automatic systems might malfunction.

But there are trade-offs. Traditional space cameras are singular in function—they're designed only for photography or video, not both simultaneously. They require active management by trained operators. They're expensive to develop, test, and maintain. They take up significant mass budget on spacecraft, which matters when every kilogram counts.

Smartphones bring different strengths. They're multifunctional—photograph, video, audio, communication, and computation all in one device. They're lightweight—typically under half a pound. They're immediately familiar to users, requiring minimal training. The computational photography systems work automatically, producing good results without technical expertise. They integrate with modern communication systems, allowing astronauts to share images wirelessly with Earth, assuming communication bandwidth is available.

Where traditional cameras shine is in extreme control and predictability. When you need absolutely perfect exposure and focus with no margin for error, manual control and raw image processing are valuable. For spontaneous, personal documentation where "good enough" is actually excellent, smartphones win.

Consider a specific example: photographing Earth from the ISS. With a traditional professional camera, an astronaut needs to manually set exposure, anticipating whether the Earth will be bright or shadowed. They might need to bracket exposures—take multiple photos at different settings—to ensure at least one is correct. The process is deliberate and time-consuming.

With a smartphone, the camera instantly adapts exposure as it analyzes the scene. It takes advantage of the latest computational photography techniques to capture detail in both the bright daytime side of Earth and the dark night side simultaneously. Within seconds, the astronaut has a perfect image without any technical decision-making.

For Artemis II lunar imaging, this difference becomes even more pronounced. The Moon presents extreme photographic challenges—bright sunlit areas and deep shadows requiring different exposures. Modern smartphone exposure blending would handle this challenge automatically, producing balanced lunar images without manual intervention.

Resolution and Quality Considerations

One might assume that taking away professional cameras would reduce image quality. But modern smartphone sensors and computational photography systems can actually rival or exceed professional cameras in many scenarios. A flagship smartphone from 2025 probably has a 48-megapixel sensor or larger, exceeding the 24-36 megapixel range common in professional DSLRs from just a few years ago.

But megapixels are only one aspect of image quality. Sensor size, lens quality, computational processing, and color science all matter. Smartphone sensors are physically smaller than professional camera sensors, which traditionally meant worse low-light performance and less dynamic range. However, computational techniques have effectively overcome these limitations. A well-optimized smartphone can often match or exceed a larger professional sensor when you factor in the computational advantages.

For space photography, where lighting is often extreme and unusual, computational photography advantages might actually make smartphones superior to professional cameras. The ability to automatically detect and handle extreme contrast, the built-in image stabilization that works without mechanical shutters, the real-time histogram and focus confirmation that helps astronauts compose immediately—these are tremendous advantages in a high-stakes environment where you might only get one chance at a particular shot.

Portability and Practicality

Smartphones offer significant practical advantages in space. They're compact enough to carry in a spacesuit pocket, if necessary. They don't require dedicated storage or specialized care. They can power multiple functions from a single battery, whereas a professional camera kit might require separate batteries for the camera, flash, and other components.

For astronauts conducting multiple tasks, the versatility of a smartphone is valuable. You might use it to photograph an experiment, then instantly communicate about what you photographed, then use the computational tools to analyze what you saw. A professional camera can photograph, but the next steps require separate devices.

Speed and Spontaneity

One factor that's difficult to quantify but valuable in practice: smartphones enable spontaneous photography in ways professional equipment cannot. Opening your phone, pointing at an extraordinary view, and capturing it in seconds is fundamentally different from preparing a professional camera with proper settings. This spontaneity captures authentic human moments.

This matters for space exploration's future. High-quality, emotionally resonant images of space experiences inspire public support. Professional mission photography is important, but personal, spontaneous imagery might actually be more powerful for inspiring the next generation of space explorers.

Mission Planning and Operational Constraints: How Astronauts Will Actually Use Phones

Bringing smartphones to space doesn't mean astronauts will have completely free rein. Space missions are meticulously planned, with every kilogram of mass accounted for and every second of time allocated. Integrating personal devices into this framework requires careful planning.

Mass budgets are the first consideration. A smartphone adds roughly half a pound of mass. For Earth orbit missions like Crew-12, this is trivial—the spacecraft has significant margins. For Artemis II, every ounce matters, as the spacecraft is traveling beyond Earth orbit where mass directly impacts trajectory and fuel consumption. However, half a pound for each astronaut, multiplied by four crew members, is roughly two pounds total. For a spacecraft with careful mass management, this is manageable but worth planning for.

Power management is more significant. Smartphones drain batteries constantly, even when you're not actively using them. In space, power comes from limited sources: solar panels for the ISS, or battery packs for spacecraft like Orion. Charging a smartphone requires power infrastructure. The ISS has electrical systems designed to support all mission equipment, so adding phone charging is straightforward. A spacecraft like Orion needs more careful power planning—every watt of charging power comes from batteries that are also powering life support, avionics, and other critical systems.

NASA will likely establish protocols around phone usage. Phones might be charged during specific periods when power is plentiful. Astronauts might be advised to use battery-saving modes during periods when power is limited. Phones might be turned off entirely during critical mission operations like launches, reentries, or docking procedures.

Software updates are another consideration. Modern phones constantly receive security updates and patches. In space, internet connectivity is limited. Astronauts will probably operate phones in fairly complete offline mode, relying only on local functionality. NASA will likely advise astronauts to ensure phones are fully updated before launch, and probably won't allow updates during missions. This creates a tension with security best practices—operating outdated software is less secure—but mission safety takes priority.

Radiation damage and bit errors are subtle concerns. In space, cosmic rays can flip bits in memory chips, occasionally causing errors or crashes. For Earth orbit, this is manageable. For Artemis II, beyond Earth's magnetosphere, radiation exposure is higher and bit error rates increase. NASA's testing probably included checking whether phones recover gracefully from radiation-induced errors. But astronauts should expect occasional glitches—frozen apps, unexpected reboots—more frequently than they experience on Earth.

Communications are complex. The ISS has high-bandwidth communication links with Earth. Astronauts can theoretically upload photographs in real-time. But bandwidth is shared among all ISS operations—science experiments, life support monitoring, communication with mission control, Earth observation satellites, and countless other uses. A 50-megabyte photograph upload might seem trivial on Earth but could occupy significant bandwidth in space. NASA will likely establish protocols about when and how astronauts can transfer data from phones.

For Artemis II, communication is even more constrained. The spacecraft has communication links with Earth, but they're designed for mission-critical data, not media uploads. Astronauts will probably be able to take unlimited photographs and videos, but uploading them might have to wait until the spacecraft returns to Earth.

This raises interesting questions about data storage. Phones have limited storage—typically 256 gigabytes maximum. High-quality video can consume gigabytes of storage per hour. For a six-month ISS mission or multi-day Artemis II journey, astronauts could easily fill phone storage. NASA will probably provide external storage devices or arrange regular uploads to free up space.

Software applications are another consideration. Astronauts will probably be able to use most consumer apps—maps, messaging, productivity tools—but will be offline, so cloud-connected features won't work. NASA might recommend specific apps for space photography, or astronauts might use general photography apps like Snapseed or Lightroom mobile for light editing.

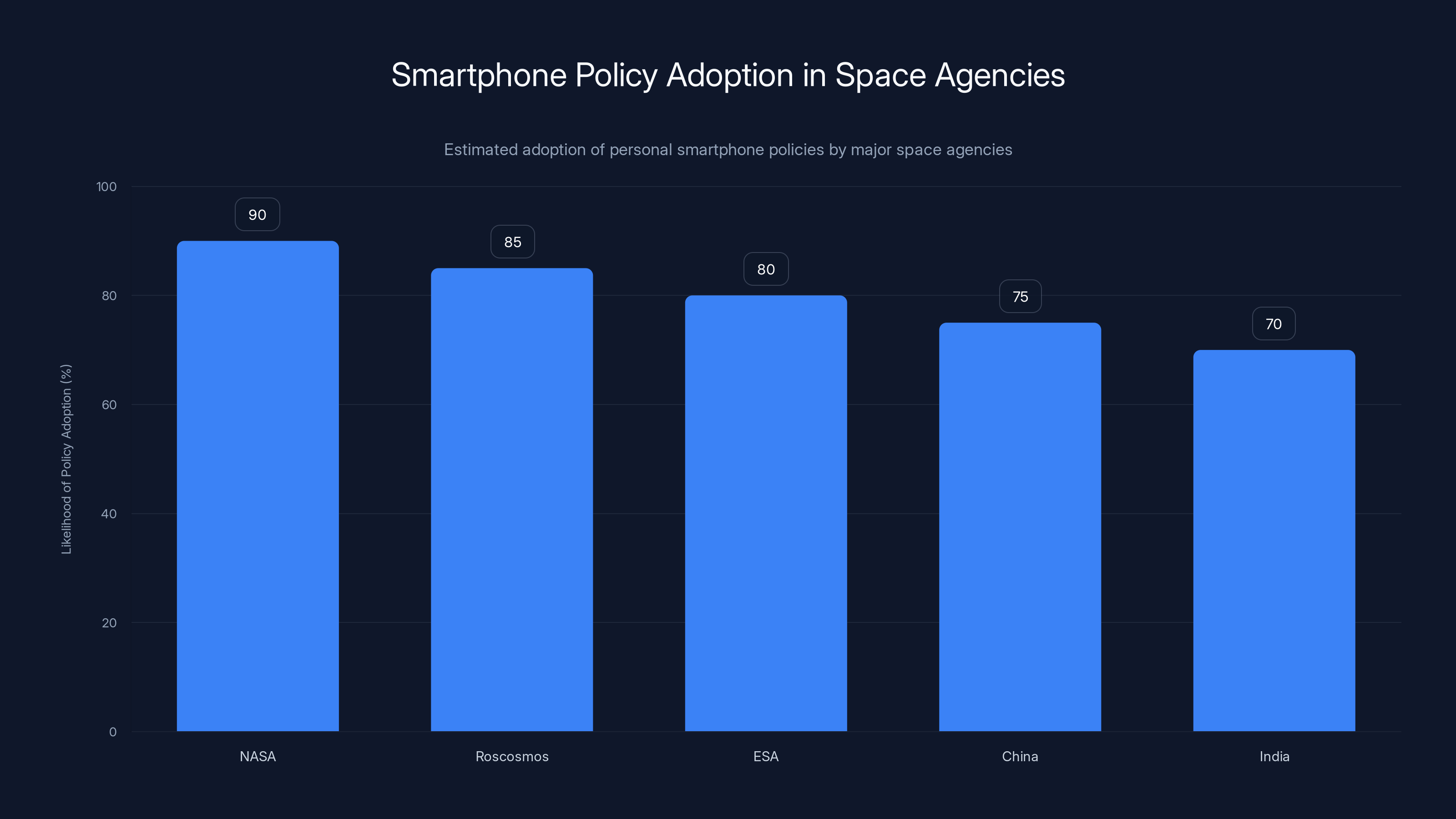

Estimated data suggests that NASA is most likely to adopt personal smartphone policies, closely followed by Roscosmos and ESA. China and India are also expected to develop similar policies as their programs evolve.

Privacy, Security, and What Astronauts Can Actually Photograph

Let's address the elephant in the room: security and privacy. Astronauts will have phones with cameras, internet connectivity when available, and the ability to photograph their surroundings. This opens several concerns.

First, classified information. The ISS and spacecraft contain sensitive research, proprietary technology from international partners, and systems that are genuinely confidential for national security reasons. NASA will almost certainly establish clear guidelines about what can and cannot be photographed. Sensitive equipment areas will be off-limits. Classified research will require explicit approval to photograph. These guidelines are probably not dramatically different from existing photo policies for ISS tours and television broadcasts—ISS imagery is regularly shared publicly, but certain areas and facilities are always excluded.

Second, personal privacy. Astronauts are people. They change clothes, exercise, use bathrooms, and have private moments. With smartphones, the potential for accidentally capturing compromising images increases. NASA will probably establish clear cultural norms around phone use—perhaps keeping phones in certain areas, or establishing photo-free zones and times. Existing spacecraft culture already emphasizes mutual respect and privacy, so this might not require dramatic new policies.

Third, data security. Smartphones are frequent targets for hackers because they contain valuable data. A smartphone belonging to an astronaut, particularly one who uses it to photograph sensitive installations and communicate with mission control, could be extremely valuable to malicious actors. NASA will probably implement security protocols: phones will be wiped of all sensitive data before the mission, encrypted communication will be used for any sensitive transmissions, and phones will probably be secured in controlled areas when not in active use.

International considerations add complexity. The ISS is a partnership involving NASA, Russia's Roscosmos, Europe's ESA, Japan's JAXA, and Canada's CSA. If astronauts from multiple nations are photographing shared facilities, there might be disagreements about what can be publicized. Artemis II involves even more international considerations, as multiple countries have contributed to the program and will have interests in what imagery is released.

From a practical standpoint, NASA has decades of experience managing ISS photography. The publicly released photos from ISS are curated, but relatively open. More sensitive imagery is restricted, but not dramatically so. Extending this system to astronaut smartphones probably doesn't represent a major security change—it's just bringing formal photo policies into the smartphone era.

One interesting consideration: phones will probably be secured with passwords and encryption. If a phone is lost or damaged during a mission, can data be recovered? This probably matters less for personal photos but becomes important if phones are used for any official purposes. NASA will likely have procedures for phone inventory management, similar to how they currently track cameras and other equipment.

Managing Expectations: What Photos Will Actually Look Like

There's something important to understand about space photography: it rarely looks like we expect. Photographs of Earth from orbit don't have the vivid colors of Earth observation satellite imagery. Earth looks, frankly, blue and brown and white. Without clouds, continents are harder to distinguish than you'd think. The horizon is darker than many people expect. There's no visible atmosphere from orbit—you don't see a thick blue line or colored sky, just the hard edge where atmosphere becomes space and then blackness.

Smartphone photos will probably make this even more apparent. Professional space photographers often apply significant post-processing and color correction to space images. Smartphones will capture what's actually there, with computational processing that aims for realistic but pleasing colors. This might be more visually accurate but less dramatic than some space imagery people are accustomed to.

Lunar photography has opposite challenges. The Moon looks smaller from lunar orbit than many people expect. It's bright but also clearly alien—gray, cratered, lifeless. Smartphone photography will capture this authentically, perhaps more effectively than professional imagery because the computational processing won't over-saturate or artificially enhance colors.

What will probably be most striking are photographs showing scale and human perspective. Pictures of astronauts working in microgravity with Earth in the window behind them. Video showing the perspective as the spacecraft orbits Earth—the rotation, the terminator line, the transition from day to night. These spontaneous, personal perspective images might be more powerful for public engagement than traditionally composed professional photography.

The Broader Implications for Private Space and International Space Exploration

When a government space agency like NASA changes policy, private space companies and international partners are watching closely. This smartphone decision will likely ripple across the entire space industry.

Private space companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and emerging companies are already thinking about passenger experiences. Allowing passengers to document their journeys with smartphones is a commercial advantage. Companies will see this NASA decision as validation for their plans. Within a few years, you'll probably see commercial space flights explicitly advertising smartphone photography capabilities.

International space agencies will adopt similar policies. If astronauts from Russia, Europe, or other nations can bring smartphones to orbit, it would be strange to exclude them. Space agencies tend to harmonize procedures where possible. This policy will likely become the global standard for human spaceflight relatively quickly.

There's also an interesting question about tourism and space hotels. Companies developing orbital hotels and research stations will want guests to bring smartphones. Guests expect to document their experiences. Allowing—or even encouraging—smartphone photography will be standard practice in private space facilities.

The decision also affects how we think about future space exploration. The Moon is going to have a permanent human presence eventually. The first lunar bases will probably include procedures for scientific documentation and personal photography. Those procedures will probably follow the patterns established by this Crew-12 and Artemis II decision.

Mars exploration introduces new complications. Communication delays mean astronauts won't be able to share images in real-time with Earth. Storing months of high-resolution photography will require massive data storage. Astronauts will probably be selective about what they photograph, or they'll use compression and automated culling techniques to manage data. But the basic principle—allowing personal documentation with smartphones—will probably extend to Mars missions.

Public Engagement and Inspiration

There's a deeper implication here about how space exploration connects with the public. For decades, space agency imagery has been filtered through official channels. Mission photographers carefully compose shots with educational and inspirational value. Mission statements emphasize scientific achievement.

But human beings respond emotionally to images that feel personal and authentic. A photograph of an astronaut's face reflecting wonder as they see Earth from space for the first time is more powerful than any scientifically composed photograph of Earth can be. That kind of authentic emotional documentation is what smartphones enable.

Government space agencies recognize this. Public support for space exploration is ultimately driven by inspiration and wonder. Allowing astronauts to share personal perspectives and spontaneous documentation is a strategic investment in public engagement and support.

Looking Forward: Smartphones as Standard Equipment

Within a few years, the idea that astronauts couldn't bring smartphones to space will seem as quaint as the idea that they couldn't bring video cameras. This policy represents a transition point where consumer technology becomes so capable that it's the right tool for the job, even for something as extreme as spaceflight.

But smartphone technology itself will continue evolving. The phones that astronauts bring on Crew-12 and Artemis II in 2025 will be outdated by the standards of 2030. Foldable phones might become standard by then. New sensor technologies could provide capabilities we haven't imagined. AI-powered image enhancement will become more sophisticated. Camera systems will probably get better at handling extreme contrast and unusual lighting.

As technology improves, the confidence in using smartphones in space will increase. Eventually, smartphones might not just supplement professional space cameras—they might replace them for many applications. Why carry heavy professional equipment when a smartphone can do the same job, weighs less, and offers more functionality?

There's also an interesting question about what happens to all these photographs. ISS astronauts have been taking thousands of photographs with professional cameras for twenty years. Most of those photographs are archived but rarely seen by the public. When astronauts are taking photographs with personal phones and sharing them directly, the volume and reach might increase dramatically. NASA will probably need to establish policies about image sharing, copyright, and archival. This could become genuinely complex—if an astronaut takes a personal photograph that later becomes historically significant, who owns it? Who can use it for commercial purposes? Who controls its distribution?

These are details that will need to be worked out over the coming years. But the fundamental decision has been made. Astronauts will bring smartphones to space. And that decision, in its quiet way, represents significant progress in how humanity explores the cosmos.

Smartphones score higher in weight, ease of use, and functionality compared to professional space cameras, making them advantageous for astronauts. Estimated data.

The Technical Future of Space Smartphones

If NASA is confident enough to allow smartphones in space now, what does that say about future technology? Probably that phones will become even more capable and even more important for space operations.

Harder radiation resistance is likely. Manufacturers working with military and aerospace applications are developing smartphones with enhanced radiation tolerance. The commercial space industry will probably drive demand for space-rated consumer devices—phones that are certified for space use but otherwise identical to consumer versions. These might feature radiation-hardened memory systems, enhanced thermal management, and software optimizations for space environments.

Better optical systems are coming. Manufacturers are experimenting with larger sensors, better zoom systems, and completely new sensor technologies. By 2030, smartphone zoom might rival telescope-like capabilities. The periscope zoom systems developed for flagship phones could eventually include multiple magnifications with extremely long focal lengths, enabling photography that today would require specialized equipment.

Improved computational photography is inevitable. The algorithms powering smartphone cameras are powered by machine learning, and machine learning improves constantly. Within a few years, smartphones might be able to do intelligent scene analysis that current systems only dream about. Imagine a phone that automatically detects and corrects for the extreme contrast of space photography, or that intelligently composes photographs based on detected astronomical features.

Battery technology improvements matter tremendously. If smartphone battery life improves from today's all-day endurance to multi-day endurance, space operations become easier. Fewer charging cycles means simpler power management. Phones that can operate for a week on a single charge would be dramatically more useful on spacecraft where power management is critical.

AI integration will probably increase. Future smartphones might include on-device AI systems that can analyze photographs immediately—identifying features of interest, flagging photos that require specific attention, even suggesting compositions for upcoming photography opportunities. Imagine an astronaut on Artemis II getting real-time AI suggestions for lunar features to photograph based on current spacecraft position and orientation.

The Cultural Significance of Smartphones in Space

Beyond the technical and practical dimensions, this policy shift represents something culturally significant. For decades, space exploration has been defined by professional expertise, specialized equipment, and formal procedures. Professional astronauts, professional cameras, professional scientific instruments. Everything meticulously planned and executed.

Allowing personal smartphones represents a democratization of space documentation. Not every astronaut needs to be a trained photographer. Not every image needs to be professionally composed. Personal, spontaneous, authentic documentation becomes valuable because it's personal and spontaneous.

This probably reflects broader changes in how humanity thinks about expertise and authority. Information sharing has been democratized by smartphones and social media. Expert gatekeeping of information is increasingly questioned. Allowing astronauts to capture and potentially share direct perspectives from space without filtering through official channels is consistent with this broader cultural shift.

It also humanizes space exploration in important ways. Space travel can seem distant and abstract. Seeing a professional photograph of the ISS is interesting. But seeing a photograph of an astronaut's hand holding a phone out the window, with Earth in the background? That's human. That's relatable. That makes space accessible in ways that formal imagery cannot.

This matters for the future of space exploration. Public support matters. Funding matters. Enthusiasm from the next generation matters. Personal, authentic imagery from space probably generates more enthusiasm than any official mission photograph could.

Challenges and Limitations: The Honest Assessment

All of this enthusiasm for smartphones in space comes with caveats. There are genuine limitations and challenges that shouldn't be glossed over.

First, reliability. Smartphones crash. They freeze. Apps fail. In mission-critical environments, reliability is paramount. NASA has tested phones extensively, but in-flight failures will probably happen eventually. An astronaut with a frozen phone loses the photography opportunity in that moment. For most situations, this is merely annoying. But what if a critical moment—a spacecraft emergency, a significant scientific observation—happens when someone's phone is malfunctioning? This is probably low risk, but non-zero.

Second, performance degradation. The radiation and thermal environment of space does impact electronics. Over time, phones might become slightly less reliable. Battery capacity might degrade faster than on Earth. Radiation-induced bit errors might become more frequent. For short missions like Crew-12 (six months) or Artemis II (about a week), this is manageable. For longer missions or repeated space flights, degradation becomes more significant.

Third, scope limitations. Smartphones are designed for casual consumer use, not professional photography or scientific documentation. The color science, dynamic range, and customization available in professional cameras exceed what smartphones offer. For formal scientific purposes, professional equipment is still superior. This policy enables personal documentation; it doesn't replace professional mission photography.

Fourth, data management challenges. Massive quantities of high-resolution photograph and video data will be generated. Managing, storing, and archiving this data is non-trivial. Selecting which photos are historically significant and worth preserving long-term is subjective. The sheer volume might make archival impractical.

Fifth, training and procedure development. Astronauts and ground teams will need to develop new procedures and norms around smartphone use. This requires time and experience. The first few missions will probably be learning experiences where unexpected issues emerge and procedures are refined.

Sixth, international coordination. With multiple nations' astronauts and multiple space agencies involved, coordinating policies becomes complex. Different countries might have different security concerns or privacy standards. Establishing globally-acceptable guidelines takes time.

These limitations don't invalidate the decision. They just mean that the implementation will be iterative and that expectations should be calibrated realistically. This policy represents progress, but not a complete solution to all space documentation challenges.

Estimated data suggests that Artemis II could provide numerous unique photographic opportunities, including capturing Earth from lunar orbit and detailed images of the Moon's surface.

The Role of Jared Isaacman and NASA Leadership

It's worth noting that this policy announcement came from Jared Isaacman, NASA Administrator. Isaacman's background is particularly relevant to this decision. Before becoming NASA Administrator, Isaacman was a successful businessman and space enthusiast. He paid for the Inspiration 4 mission—a private spaceflight funded entirely by Isaacman that flew four non-professional astronauts, including himself, to Earth orbit.

During Inspiration 4, Isaacman spent several days in space. He photographed Earth extensively. He understood firsthand the power of space imagery and the desire to document the experience. His perspective as someone who had actually flown to space and dealt with the limitations of formal space procedures probably influenced this smartphone policy.

This represents leadership that draws from personal experience. Isaacman didn't just analyze NASA requirements; he lived them. He understood that astronauts want better documentation tools, that the public craves authentic space imagery, and that consumer smartphones had become capable enough to meet these needs.

This leadership approach—bringing real-world experience to policy making—might become more common as the commercial space industry grows. Space agencies will increasingly include personnel with actual spaceflight experience who can draw from that experience when making decisions.

Comparing International Space Program Approaches

Different space agencies approach human spaceflight differently. Understanding these differences provides context for why NASA's decision matters.

Roscosmos, Russia's space agency, operates Soyuz vehicles and maintains a major presence on the ISS. Russian cosmonauts have less stringent equipment restrictions than NASA astronauts in some areas. They might be among the first to bring personal smartphones to space, particularly if Russian cosmonauts are included on shared missions.

The European Space Agency (ESA) tends to follow NASA's lead on operational procedures while maintaining its own unique policies. European astronauts will probably adopt smartphone policies similar to what NASA establishes.

China's space program, operating independently, will probably develop its own smartphone policies for its spacecraft. The taikonauts aboard China's space station will likely have smartphone access, though policies might emphasize official purposes more than personal documentation.

India, with a growing human spaceflight program, will probably adopt smartphone policies as it develops its own crewed spacecraft.

The trend across all agencies is likely toward permitting personal smartphones, driven by the same logic that motivated NASA: consumer devices have become capable, astronauts want better tools, and public engagement benefits from authentic documentation.

Data, Archival, and Historical Significance

Here's something important that hasn't been discussed much: what happens to all these photographs and videos long-term? When astronauts document everything with smartphones, the historical record becomes vastly larger.

ISS astronauts have taken tens of thousands of photographs with professional cameras over twenty years. Most are archived with NASA, some are publicly available. The volume is manageable. When every astronaut is taking personal photographs with smartphones, the volume could increase by orders of magnitude. Managing and archiving this data becomes genuinely challenging.

NASA will need to develop policies around:

- Data retention: Which photos are worth keeping permanently?

- Metadata: How do we catalog and describe millions of photos?

- Access: Who can see which photos? Are personal photos private or public records?

- Preservation: What formats should we use to ensure data survives 50+ years?

- Copyright: When an astronaut takes a personal photo, who owns the rights?

Historically, mission photographs have been carefully curated official records. Smartphone photographs are casual personal documentation. They're different beasts entirely, requiring different management approaches.

But they might be more historically valuable precisely because they're authentic. The personal perspective of someone living through historic moments is often more significant than formally composed professional imagery. In a hundred years, the casual smartphone photos from Artemis II might be treasured as irreplaceable windows into the lived experience of returning to the Moon, while professional photos might be considered dated and artistic rather than documentary.

NASA will probably develop frameworks for this over coming years. Mission documentation specialists will probably sort through smartphone photos after missions, selecting significant images for long-term archival while discarding duplicates and technical failures. This seems labor-intensive but necessary.

Future Missions and Technological Roadmap

Looking forward, how will space agencies evolve smartphone use as they gain experience?

Crewcraft will probably integrate better charging and storage infrastructure. Current spacecraft have power outlets and USB charging—the same technology available on Earth. But spacecraft designers might develop purpose-built smartphone docking stations that provide power, data connectivity, and secure storage simultaneously.

Data transmission will likely improve. Establishing high-bandwidth communication between orbiting astronauts and Earth is technically challenging but important if we want to share images in real-time. Future missions might include dedicated communication systems for transferring media from astronaut phones to Earth.

Phone software will probably become more space-optimized. Custom firmware might be developed that disables unnecessary background processes, improves battery management, and adds space-specific features like radiation damage detection or orbital mechanics visualization.

Multi-phone systems might emerge. Astronauts might carry dedicated phones for photography, others for communication, others for mission documentation. Each could be optimized for its specific purpose.

Integration with spacecraft systems is possible. Future spacecraft might allow phones to interface with navigation systems, sensors, and communication equipment. Astronauts could access spacecraft data through their phones, or phones could transmit data to spacecraft systems.

The trajectory is clear: consumer smartphones will become more tightly integrated into space operations, more optimized for space environments, and more central to how humans experience and document spaceflight. Within a decade, saying "astronauts didn't have smartphones in space" will sound like ancient history.

FAQ

What is NASA's new smartphone policy for astronauts?

NASA now permits astronauts on missions like Crew-12 and Artemis II to bring personal smartphones into space for documentation, personal use, and photography. These phones will remain inside spacecraft where environmental controls protect them from extreme conditions, enabling astronauts to capture images and videos of their experiences without relying solely on traditional professional space cameras.

Why is NASA allowing smartphones in space only now?

Smartphone technology has evolved to become significantly more capable and reliable. Modern computational photography, radiation tolerance improvements, and proven testing in space-like conditions demonstrated that consumer devices could function reliably in orbiting spacecraft. Additionally, NASA leadership recognized that astronauts want better personal documentation tools and that authentic smartphone imagery could increase public engagement with space exploration.

How will smartphones survive the harsh space environment?

Smartphones will remain inside pressurized spacecraft where environmental controls maintain reasonable temperatures and protect from vacuum. The ISS maintains about 70 degrees Fahrenheit and Earth-normal atmospheric pressure inside. Astronauts will secure phones during launch and reentry when vibration could damage them. For deep space missions like Artemis II, spacecraft environmental controls protect phones from extreme radiation and temperature fluctuations that exist outside the vehicle.

What are the advantages of smartphones over professional space cameras?

Smartphones offer computational photography that automatically optimizes for challenging lighting conditions, weigh significantly less, require minimal training, can capture both photos and videos instantly, and provide multiple functions beyond photography. Modern smartphone sensors rival professional cameras in resolution and capability, while the built-in image processing produces immediately usable images without requiring technical expertise. This spontaneity and versatility make smartphones ideal for personal documentation, though professional cameras remain superior for specialized scientific imaging.

Will astronauts be able to share photos from space in real-time?

On the ISS, astronauts potentially could share images if NASA allocates communication bandwidth for personal data transfers. For Artemis II, communication capacity is limited by mission requirements, so astronauts will likely store photos and videos during the mission with uploads happening after returning to Earth. Future missions may develop better communication systems allowing real-time media sharing from space.

What security concerns exist with smartphones in space?

NASA will establish guidelines preventing photography of classified research, sensitive spacecraft systems, and international partner facilities. Personal privacy protocols will be established to protect astronaut dignity. Data security measures will include phone encryption and access controls. Pre-mission wiping of unnecessary data and post-mission security reviews will address cybersecurity concerns. These policies extend existing ISS photography guidelines into the smartphone era.

Will Artemis II produce the first smartphone images from the Moon?

Artemis II will likely produce the first smartphone images from lunar orbit, though the spacecraft will orbit the Moon rather than land on the surface. These images will represent historic first photographs of lunar features captured with consumer smartphone technology, potentially offering different perspectives than professional Apollo-era photography due to modern computational photography capabilities.

How will smartphone data be stored and archived?

NASA will likely download smartphone photos and videos after missions for archival. The massive volume of potential data will require careful curation to determine which images have historical significance and should be preserved long-term. Metadata cataloging and preservation formats will need to be established to ensure data survives decades while remaining accessible to future researchers and the public.

Could other space agencies adopt similar smartphone policies?

International space agencies and private space companies will almost certainly adopt similar or identical smartphone policies. Space agencies typically harmonize procedures where possible, and commercial space companies see allowing passenger smartphone documentation as a competitive advantage. Within several years, smartphone access will probably become standard across human spaceflight programs.

What does this policy mean for future space tourism and private spaceflight?

Private space companies will use NASA's policy as validation for allowing passengers to bring smartphones. Commercial space stations and tourism spacecraft will almost certainly permit smartphone use, as passengers expect to document their experiences. This decision effectively sets the standard for how consumer electronics will be integrated into all future human spaceflight operations, whether government or commercial.

The Bottom Line: A New Era of Space Documentation

NASA's decision to allow astronauts to bring smartphones to space represents more than just a policy update. It's an acknowledgment that consumer technology has become sophisticated enough to compete with specialized equipment, even in the most extreme environments humans have created.

It's a recognition that authenticity and personal perspective matter for public engagement with space exploration. A photograph taken by an astronaut for personal reasons, shared directly from orbit, might inspire more people than a professionally composed scientific image ever could.

It's an evolution in how we think about expertise and specialization. Not every space photograph needs to be taken by a trained professional using expensive specialized equipment. Sometimes the best documentation comes from spontaneous, personal perspectives captured by the people actually living the experience.

Most importantly, it opens new possibilities for how humanity documents its expansion into space. The Crew-12 and Artemis II missions will produce photographs and videos that look different from anything captured in space before. Not necessarily better, not necessarily worse, but authentically different because they'll be captured with different equipment, different intentions, and different perspectives.

Within a few years, this policy will seem obvious in retrospect. Of course astronauts have smartphones in space. Everyone has smartphones everywhere. But right now, in 2025, it represents genuine progress in how we approach human spaceflight.

The first smartphone images from lunar orbit will be historic. They'll be preserved alongside Apollo-era photographs and ISS imagery as part of humanity's visual record of space exploration. They'll demonstrate that consumer technology has reached a maturity where it's appropriate for humanity's greatest adventures.

And that's genuinely remarkable.

Key Takeaways

- NASA now permits astronauts on Crew-12 and Artemis II to bring personal smartphones to space for personal documentation and photography

- Modern smartphone computational photography capabilities rival or exceed specialized space cameras in many scenarios, justifying the policy shift

- Artemis II will produce the first smartphone images from lunar orbit, marking a historic milestone in space documentation

- Smartphones will remain protected inside pressurized spacecraft where environmental controls maintain safe operating conditions

- This policy will likely become standard across international space agencies and private space companies within coming years

Related Articles

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- NASA's Fraggle Rock Space Adventure: Muppets Meet Moon Exploration [2025]

- Artemis II Crew Quarantine: Why Astronauts Must Isolate Before Moon [2025]

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- Google Pixel 10A Launch: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

![NASA Astronauts Can Now Take Smartphones to Space [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-astronauts-can-now-take-smartphones-to-space-2025/image-1-1770392258025.jpg)