Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

When you think about space exploration, smartphones probably aren't the first thing that comes to mind. For decades, NASA has relied on specialized cameras and equipment designed specifically for the harsh environment beyond Earth's atmosphere. But something fundamental just shifted. In early 2026, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman announced a decision that sounds simple on the surface but represents something far more profound: Artemis II astronauts will be allowed to bring iPhones—regular, off-the-shelf iPhones—to the Moon, as reported by Ars Technica.

This isn't just about getting better photos of the lunar surface, though those will undoubtedly be spectacular. This decision represents a watershed moment in how NASA approaches technology qualification, operational efficiency, and crew capability. It's a direct challenge to decades of bureaucratic bloat, and it signals a fundamental rethinking of what it means to equip astronauts for modern space missions.

The story of how we got here reveals something important about large institutions, the cost of excessive caution, and why sometimes you need someone willing to ask the uncomfortable question: "Do we actually need this requirement anymore?"

The Smartphone Revolution Meets Space Bureaucracy

Smartphones have become so integral to our daily lives that it's almost impossible to imagine conducting serious work without one. They're cameras, communication devices, computation engines, and sensors all rolled into one. Yet NASA has been conspicuously absent from this revolution.

For the better part of the past decade, astronauts aboard the International Space Station have relied on tablets for internet communication and connection with family members. These devices, while capable, lack the processing power, camera quality, and versatility that modern smartphones provide. It's like having a team of engineers equipped with slide rules while their colleagues on Earth have access to supercomputers.

The irony is stark. The space agency responsible for the Apollo missions—which pushed the boundaries of technology and human capability—had become the organization saying "no" to the devices that everyone else on the planet uses daily. The most advanced explorers in human history were being asked to document their work with cameras that were already obsolete by terrestrial standards.

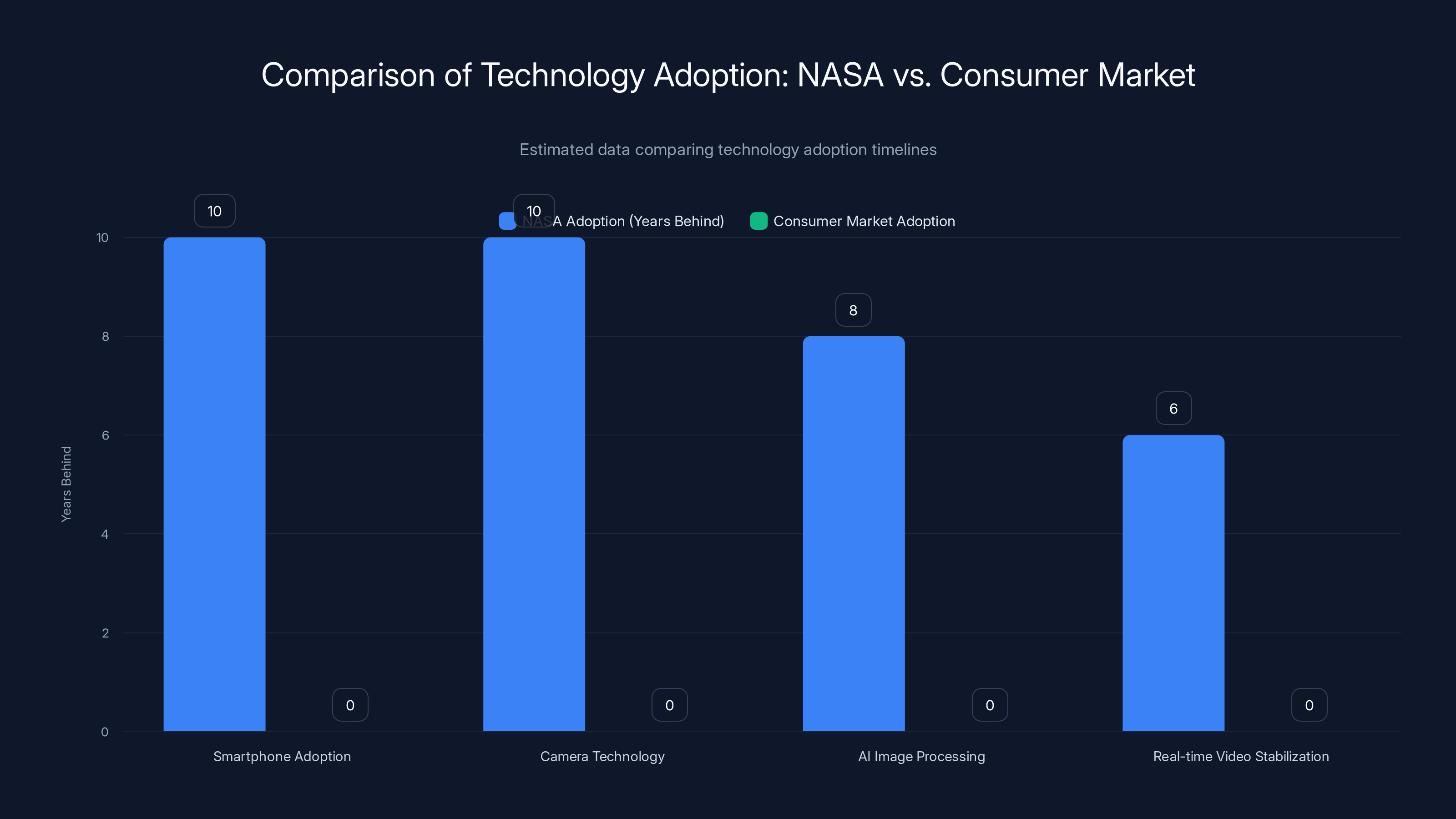

Before this change, the newest camera approved for the historic Artemis II mission was a Nikon DSLR from 2016. Think about that for a second. By 2026, a 2016 camera is a decade old in technology terms. The smartphone in your pocket today is more computationally powerful than the cameras NASA was allowing its astronauts to use on humanity's return to the Moon.

GoPro cameras, also roughly a decade outdated, rounded out the imaging arsenal. These are decent devices, but they represent technological conservatism bordering on absurdity. While the world has moved to computational photography, AI-assisted image processing, and real-time video stabilization, NASA's astronauts have been stuck in the past.

The question isn't really "Why didn't NASA allow iPhones sooner?" The real question is "Why did it take this long?" And the answer to that question reveals something important about how massive organizations make decisions and what happens when bureaucratic processes ossify over time.

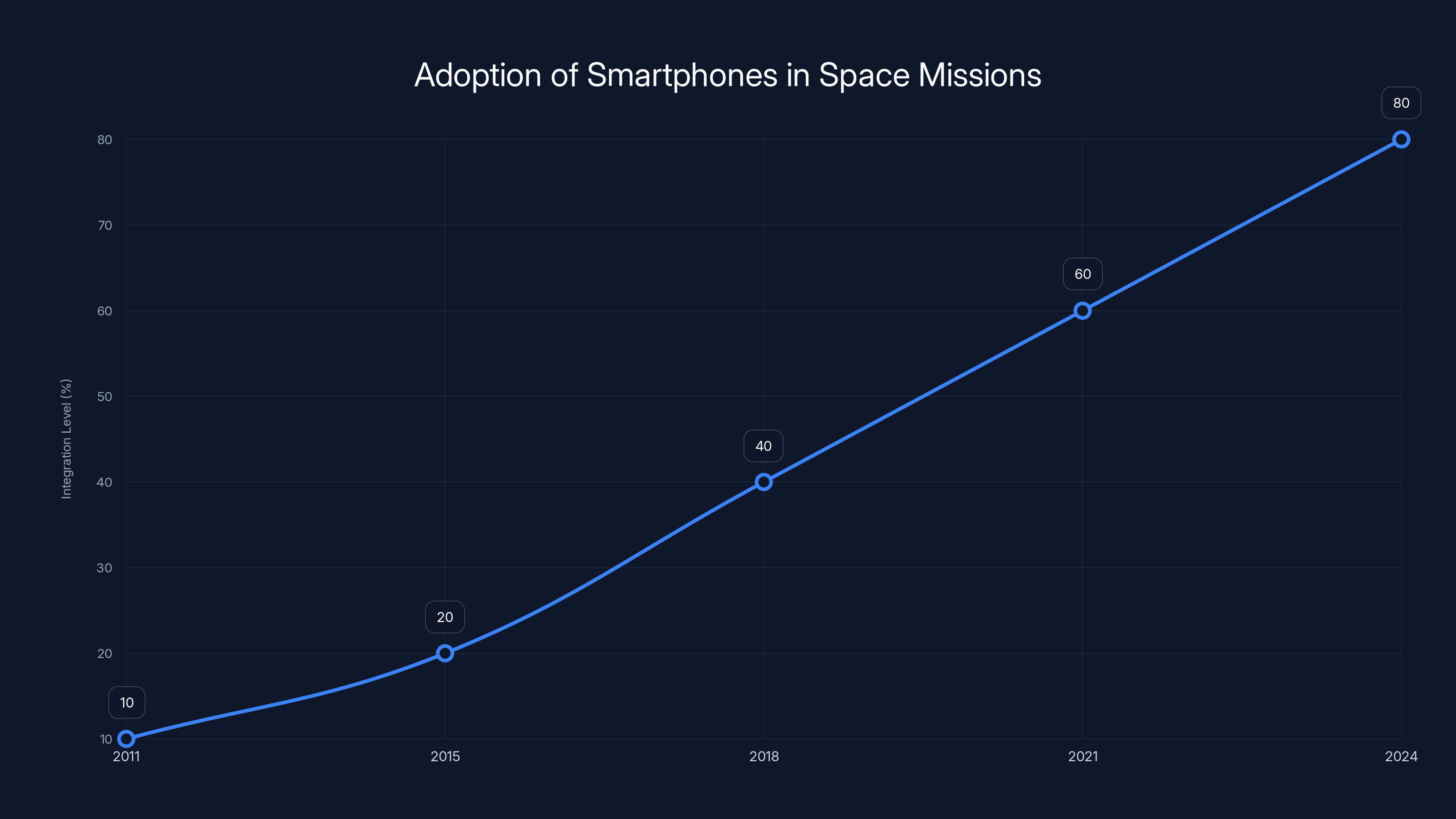

The integration of smartphones in space missions has increased significantly from 2011 to 2024, with private spaceflight companies leading the way. (Estimated data)

Understanding the Qualification Gauntlet

Before you dismiss NASA's cautiousness as simple institutional inertia, you need to understand what actually goes into qualifying a piece of technology for spaceflight. This isn't just about checking a box on a form. It's a legitimate engineering challenge with real safety implications.

Space is hostile. Really hostile. The radiation environment in orbit and beyond Earth's protective magnetic field can damage semiconductor components in ways that don't happen on the ground. A single energetic particle can flip a bit in your device's memory, causing unexpected behavior. Sometimes this is benign. Sometimes it's catastrophic.

Then there's thermal stress. Spacecraft experience extreme temperature swings. Components must be tested to ensure they function properly across temperature ranges that would destroy consumer electronics. Battery thermal management is particularly critical. You don't want a lithium battery failing in an uncontrolled way 250 miles above the Earth.

Outgassing is another consideration that most people have never heard of. When materials are exposed to vacuum, volatile compounds can evaporate from them. These compounds can then condense on optical surfaces, reducing visibility. This is why NASA qualifies materials so carefully. A layer of outgassed polymer on a camera lens isn't just annoying. It's a mission failure.

Vibration testing ensures that components can withstand the launch environment. The acceleration forces during launch can exceed 3 Gs. If a component can't handle that, it fails. Electromagnetic compatibility testing verifies that your device won't interfere with critical spacecraft systems or be damaged by the electromagnetic environment of the spacecraft.

Then there's the issue of software. Space-rated computer systems often run on processors from years ago because the software has been validated and thoroughly tested. Modern processors are constantly updating, and that constant change creates uncertainty. If an iPhone receives a software update in orbit, does that affect its behavior? These are the kinds of questions that keep engineers awake at night.

All of these requirements exist for a reason. Space exploration is expensive. Losing a mission because of a simple component failure is not just wasteful. It's tragic. The conservative approach makes sense.

But there's a flip side to this coin.

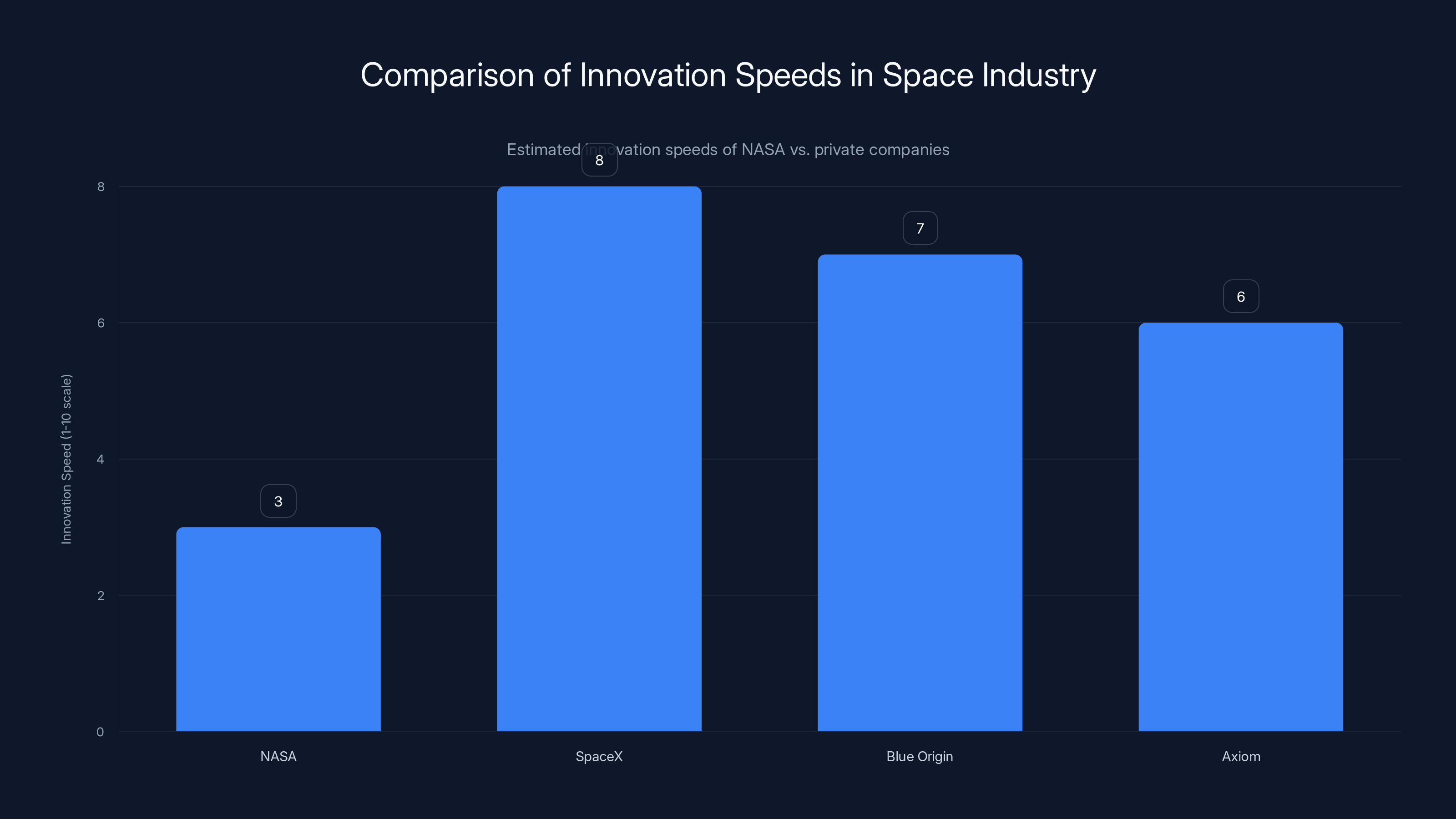

Private companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Axiom are estimated to have higher innovation speeds compared to NASA, highlighting the competitive pressure on NASA to modernize. Estimated data.

The Hidden Cost of Excessive Requirements

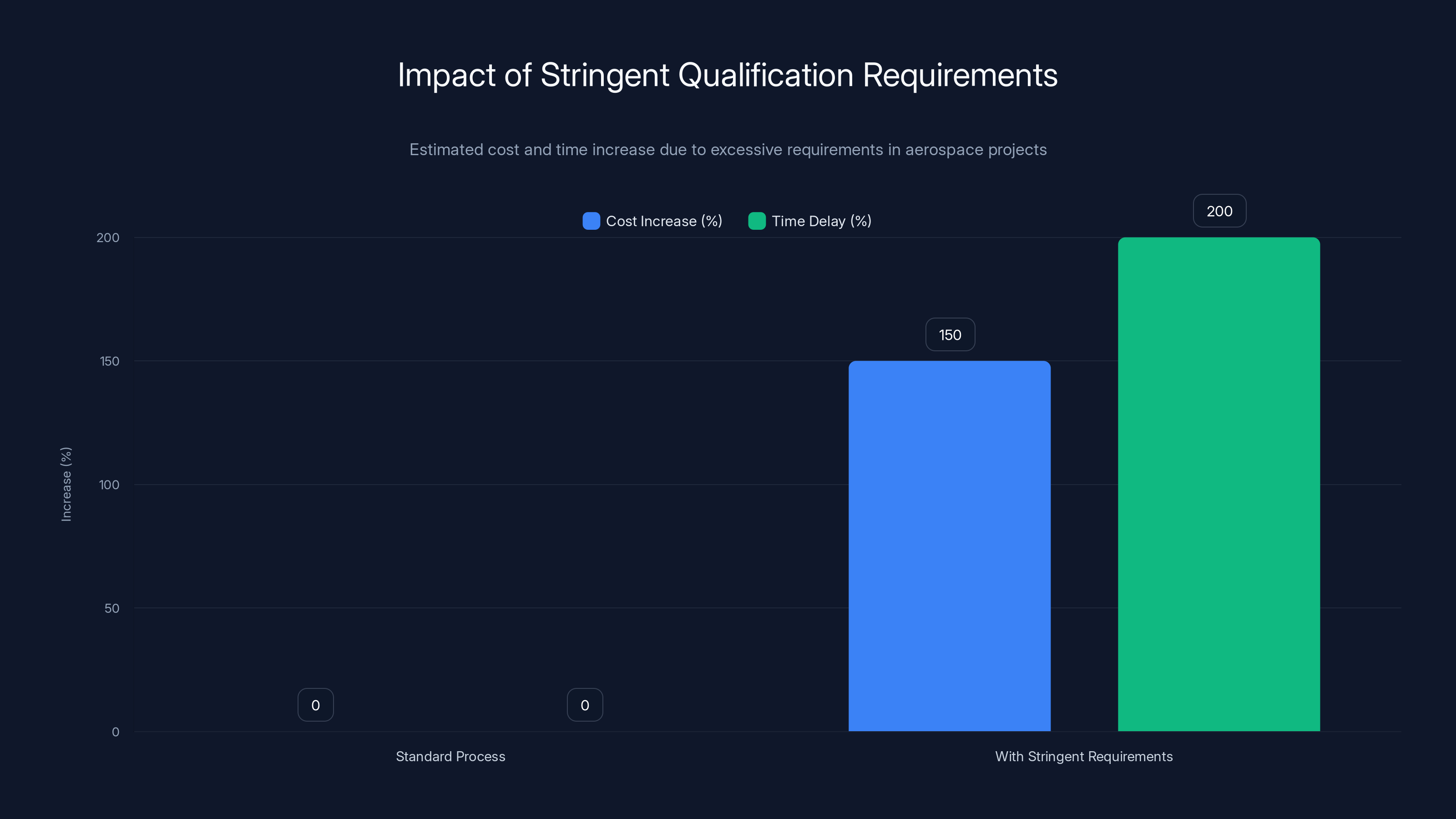

Here's what happens when you overlay extremely stringent qualification requirements on top of existing design processes: things slow down. A lot. And they get expensive. Very expensive.

When NASA says a component must be qualified for spaceflight, that qualification process involves extensive testing, documentation, and verification. A commercial smartphone manufacturer never has to think about half the failure modes that NASA engineers must consider. They never test their devices in vacuum chambers. They never check for outgassing compliance. They certainly don't conduct radiation characterization.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. If you want to fly a camera on NASA spacecraft, you essentially have to conduct your own parallel development program. You test it to spaceflight standards. You document everything. You undergo independent reviews. The cost can be substantial.

Now multiply that across an organization the size of NASA. Every piece of equipment. Every subsystem. Every component. The bureaucratic weight becomes immense. Contractor organizations maintain entire teams dedicated to compliance with these requirements. And somewhere, a decision maker asks: "Is this requirement actually necessary?" And more often than not, nobody has a good answer, so it stays on the books.

This is what Isaacman meant when he talked about "challenging long-standing processes and requirements." He wasn't saying that safety requirements are bad. He was saying that organizations accumulate requirements over time like sediment in a river. Some are essential. Some are historical artifacts. Some made sense in 1997 and haven't been revisited since.

The decision to allow iPhones represents a deliberate choice to do something radical: evaluate whether existing requirements are still necessary for the specific mission at hand. For Crew-12 and Artemis II, carrying a smartphone doesn't present the same risks as, say, carrying a new experimental life support system. iPhones are well-understood technology. They're used by billions of people. The failure modes are known.

Okay, so they might lose signal in orbit. The camera app might crash. These aren't mission-ending failures. They're inconveniences that people deal with every single day on Earth.

The Real Motivation: Operational Urgency

Isaacman framed this decision as being about "operational urgency." That's the key phrase here, and it reveals something important about where NASA is heading.

The space agency faces a different competitive landscape than it did a decade ago. Private spaceflight companies are operating at cadences that NASA can't match. SpaceX launches multiple Crew Dragon missions per year. Blue Origin is developing commercial spaceflight vehicles. Axiom Space is building commercial space stations. These companies move fast.

NASA, being a government agency with all the associated bureaucratic frameworks, moves slower. That's not a moral judgment. It's simply the nature of government procurement and oversight. But it does create a problem: how do you maintain technical superiority and operational relevance when you move slower than competitors?

One answer is to challenge your own processes. Force your organization to justify every requirement. Ask the hard question: "Does this slow us down more than it protects us?" For a smartphone, the answer is increasingly: "Yes, the safety benefit is marginal compared to the operational cost."

This decision also reflects a shift in thinking about crew autonomy and capability. Modern astronauts are highly trained professionals operating in a complex environment. They understand risk. They understand their equipment. Giving them modern tools that they already know how to use—because they use them on Earth every single day—makes operational sense.

An astronaut doesn't need specialized training to use an iPhone. They already know how to take photos, record video, and manage settings. Compare that to specialized space cameras where astronauts must learn unique interfaces and workflows. The operational advantage of familiar technology is substantial.

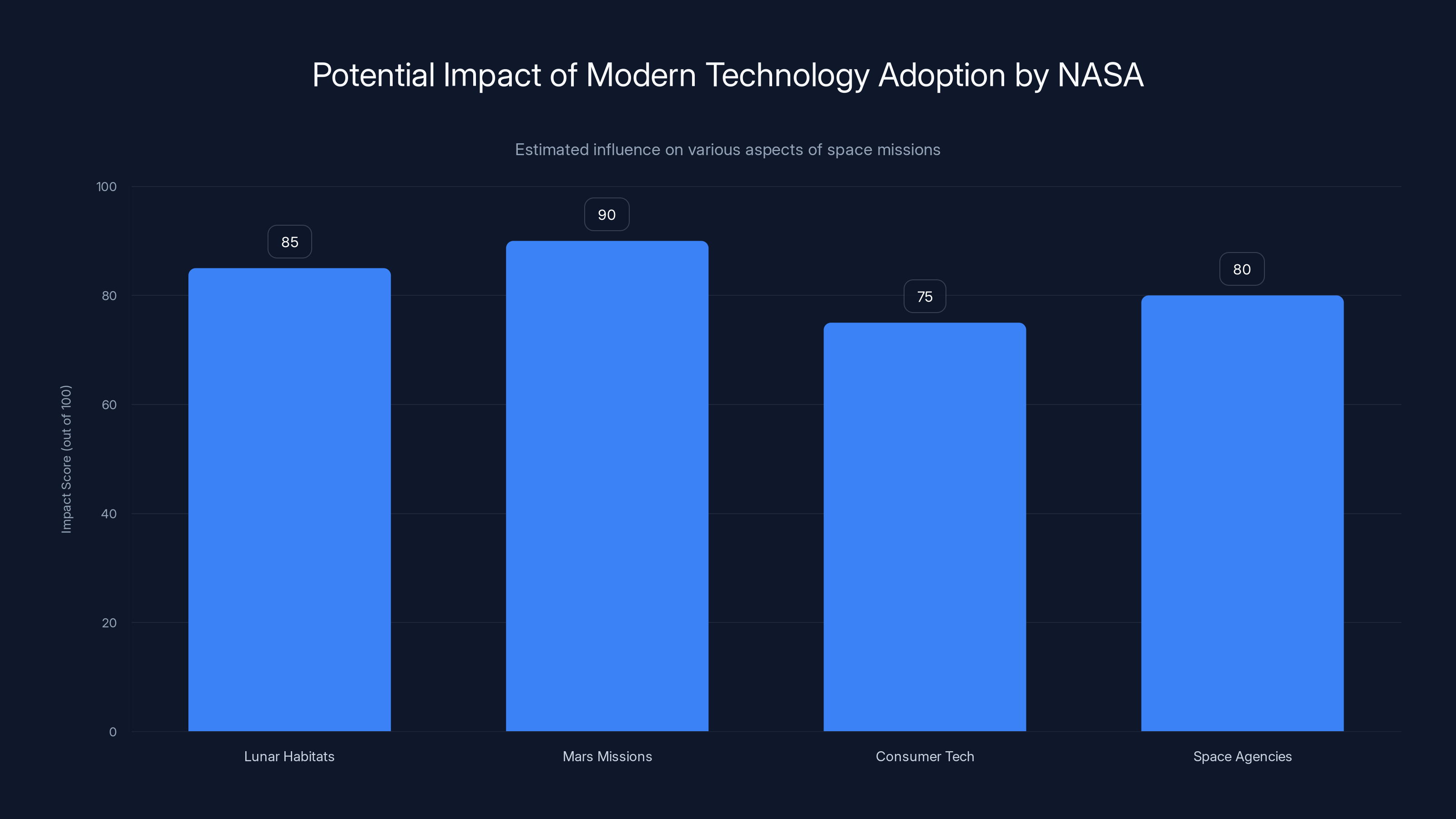

Adopting modern technology could significantly enhance space mission efficiency and influence consumer tech development. (Estimated data)

Smartphones in Space: A Brief History

People often assume that bringing smartphones to space is entirely new territory. It's not. There's actually a small but growing history of smartphones operating in orbit.

During the final space shuttle mission in 2011, two iPhone 4s flew aboard. But here's the catch: it's unclear whether the crew ever actually used them. They were essentially passengers, brought along to demonstrate that the technology could function in space, but not integrated into any meaningful way into crew operations.

That's the difference between bringing something to space and actually using it for its intended purpose. The iPhone 4s flight was more of a proof of concept than operational integration.

Private spaceflight has been more aggressive about smartphone adoption. During the Polaris missions—Isaacman's own series of commercial spaceflights—crew members brought and used smartphones. The difference is profound. Polaris astronauts weren't just carrying phones. They were taking photos, recording video, and transmitting content back to Earth. They integrated smartphones into their operational workflows.

Similarly, astronauts on commercial missions to the International Space Station, including Axiom Space missions, have brought smartphones. There's a complication here: astronauts were technically not supposed to bring phones from the Dragon spacecraft onto the International Space Station itself. But during Axiom-1 in 2024, astronaut Michael Lopez-Alegria reportedly brought his smartphone on board. The rule existed, but operational reality suggested it was unnecessarily restrictive.

This pattern reveals something important: private spaceflight companies were ahead of NASA in recognizing the value of modern communication and documentation tools. The commercial space sector said, "Let's use the tools we have rather than insist on specialized hardware." NASA eventually came to the same conclusion, but it took longer.

The Implications for Lunar Exploration

When Artemis II astronauts step onto the lunar surface, they'll do something that hasn't been possible since 1972: document humanity's return to the Moon with modern technology. This isn't trivial.

The Apollo astronauts took extraordinary photographs from the Moon. Those images captivated the world and remain stunning today. But imagine if they'd had access to modern smartphone cameras with their computational photography capabilities. Imagine night mode for capturing the lunar night. Imagine video stabilization for smooth footage as they traverse the surface. Imagine the ability to immediately share unprocessed images with mission control, allowing for real-time adjustments to the photography plan.

Smartphone cameras also introduce possibilities that traditional space cameras don't easily accommodate. An astronaut can snap a quick photo of an interesting rock formation without planning ahead. With specialized cameras, documentation tends to be more formal and less spontaneous. The informal observation often reveals unexpected scientific insights.

There's also the documentation of experiments and procedures. When an astronaut is working with scientific equipment and needs to document what they're doing, having a phone in their pocket means they can quickly capture a photo or video without needing to stage the camera. This kind of real-time documentation can be incredibly valuable for scientific analysis.

Beyond the technical benefits, there's something important about human connection. Isaacman specifically mentioned allowing crews to "capture special moments for their families and share inspiring images and video with the world." This is about more than documentation. It's about maintaining the human element of space exploration.

Astronauts are away from their families for extended periods. Having a modern communication device that allows them to take a selfie in front of the Earth or record a personal message has genuine psychological value. It helps maintain the human connection that makes space exploration meaningful to the broader public.

When an astronaut can instantly share an image of Earth from lunar orbit with their family, it creates a moment of connection that transcends the technical achievement. This is something that Isaacman clearly understands and values.

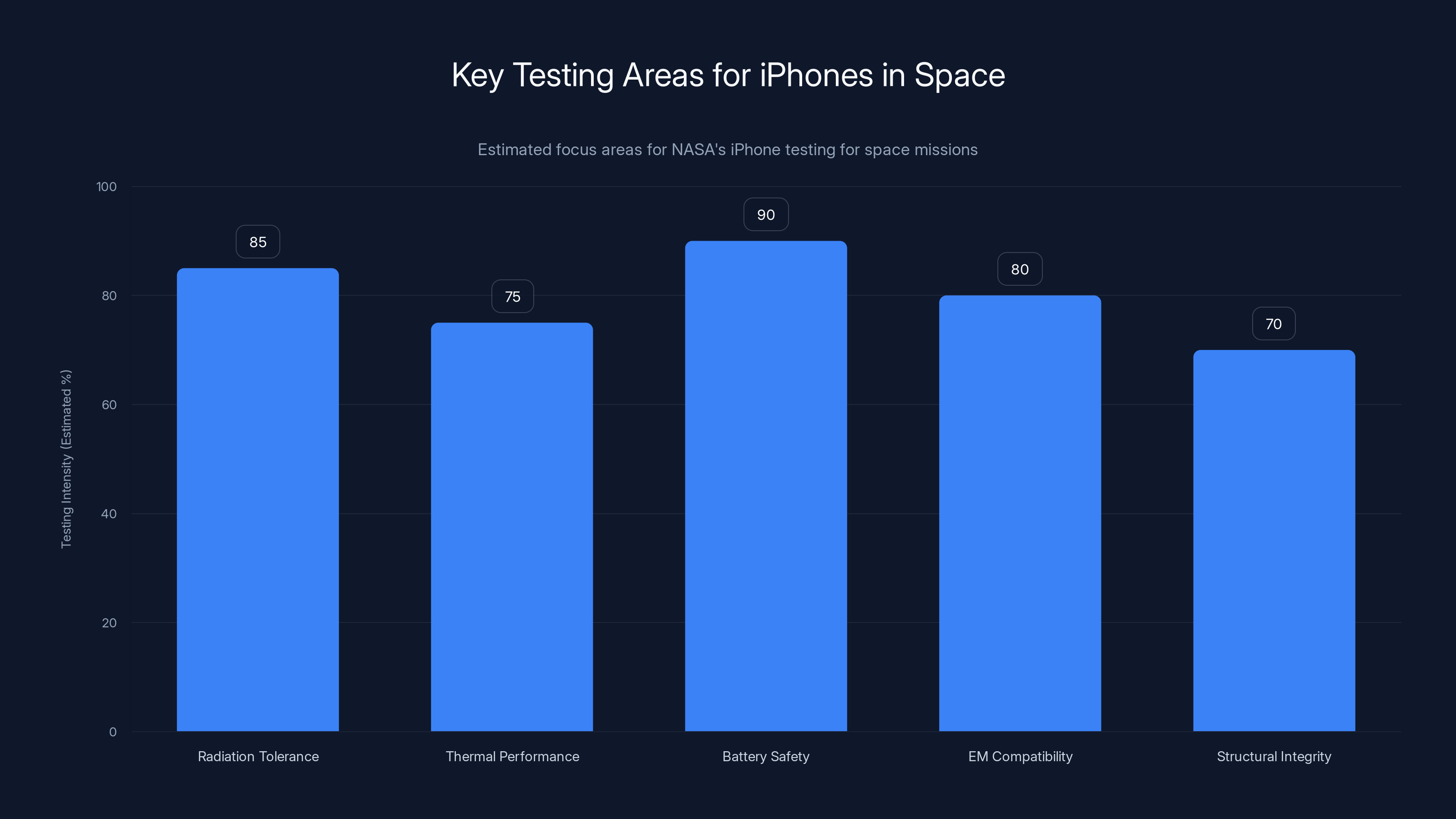

NASA's testing of iPhones for space missions likely focused on radiation tolerance and battery safety, with an estimated intensity of 85% and 90% respectively, reflecting critical mission requirements. Estimated data.

The Qualification Process: Accelerated and Pragmatic

One of the most significant aspects of this decision is how the qualification process itself changed. Isaacman didn't just say "iPhones are now allowed." He specifically mentioned challenging processes and qualifying the hardware on an "expedited timeline."

This is code for: we're not running a standard multi-year qualification program. We're being pragmatic. We're asking what actually needs to be tested and what doesn't. We're moving as fast as safety permits.

For a smartphone, this pragmatism makes sense. iPhones are radiation-tolerant enough for the environments they'll experience on Artemis II. They've been tested in vacuum by researchers. Apple's battery technology is well-understood. The failure modes are known.

What NASA likely didn't do is subject iPhones to the complete qualification gauntlet. They didn't need to. They performed targeted testing of the specific failure modes that matter for this mission, approved the integration approach, and moved forward.

This represents a subtle but important shift in NASA's philosophy. Rather than asking "What does our standard qualification process require?" they're asking "What specific threats exist for this mission, and how do we mitigate them?" That's a more efficient approach.

It's also an approach that will likely accelerate NASA's ability to adopt new technologies in the future. If the agency can develop a flexible qualification framework that doesn't impose unnecessary requirements while maintaining actual safety, it opens the door to rapid technology adoption.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite the obvious benefits, there are legitimate challenges with flying smartphones in space that shouldn't be glossed over.

The radiation environment in Earth orbit and beyond is genuinely harsh. While smartphones can function in these environments, there is accumulated damage over time. A smartphone taken on a year-long mission might experience thousands of radiation hits that flip bits in memory or damage semiconductors. For short-duration missions like Artemis II, this is manageable. But as missions extend, radiation becomes increasingly problematic.

Battery management is also challenging. Lithium batteries in spacecraft require careful monitoring. They can overheat. They can suffer unexpected failures. NASA has strict protocols for battery management in spacecraft. An iPhone's battery management system works fine on Earth, but in the thermal environment of a spacecraft, additional monitoring is necessary.

Software updates are another complication. Apple continuously updates iOS with security patches and new features. NASA will almost certainly disable wireless connectivity on the iPhones, meaning they can't receive updates automatically. But this creates a different problem: the iPhones will be running older versions of iOS that might have known vulnerabilities or bugs. This is a manageable problem, but it's not zero-risk.

Electromagnetic interference is a concern. Modern smartphones have complex antenna arrays and wireless systems. They emit electromagnetic energy. In a sensitive spacecraft environment, this could theoretically interfere with other systems. NASA likely tested this extensively, but it remains a consideration.

There's also the question of what happens if an iPhone fails catastrophically. It probably won't, but if it does, what's the failure mode? Does the battery catch fire? Does the screen shatter? Does liquid damage risk contaminating other spacecraft systems? These are edge cases, but spaceflight is a domain where you have to think through edge cases.

The most practical limitation is connectivity. In orbit, iPhones won't have cellular service. They might connect via spacecraft WiFi to communicate with mission control or transmit to Earth, but they won't have the full functionality they have on the ground. Cloud services are constrained. Real-time communication is through spacecraft infrastructure, not cellular networks.

Despite these challenges, they're all manageable problems. None of them are show-stoppers. They're just the kind of engineering constraints that make space exploration complex.

NASA's technology adoption in areas like smartphones and cameras has lagged behind the consumer market by several years, highlighting a significant gap in leveraging modern tech advancements. Estimated data.

Why This Matters Beyond Technology

The decision to allow iPhones aboard Artemis II is ultimately about something bigger than cameras. It's about how NASA makes decisions and what that says about the agency's future direction.

For an organization of NASA's scale and responsibility, there's always tension between caution and progress. Excessive caution leads to stagnation. Insufficient caution leads to catastrophe. The trick is finding the balance.

For decades, NASA erred on the side of caution in ways that accumulated into genuine inefficiency. Each requirement made sense in isolation. But together, they created a system so burdensome that the agency struggled to adopt modern technology at anything resembling the pace of the commercial sector.

Isaacman's emphasis on challenging requirements is a direct challenge to this accumulated inertia. It's a message to NASA's bureaucracy: prove that every requirement is still necessary. Don't just assume it is.

This has implications far beyond smartphones. If NASA can develop processes for pragmatically evaluating requirements, that same approach can apply to other technologies. Why are some spacecraft components using processors from 2010? If there's a good reason, fine. But if it's just "that's what we've always done," that's a problem.

The decision also signals something to private space companies. NASA is willing to learn from the commercial sector. When Axiom and other companies demonstrated that smartphones could be used productively in space, NASA was paying attention. The agency isn't so rigidly committed to its own processes that it can't adopt better approaches developed elsewhere.

Perhaps most importantly, this decision is about crew capability and autonomy. Modern astronauts are highly trained professionals. Giving them modern tools that they already know how to use is respectful of their expertise and practical from an operational standpoint. It's a recognition that the best way to accomplish complex objectives in challenging environments is to empower your people with the best tools available.

The Competitive Landscape: Why Timing Matters

There's a reason this decision came now, and not five or ten years ago. The competitive landscape in space has changed dramatically.

When NASA was the only game in town for human spaceflight, the agency could move at its own pace. There was no competition. Now there is. SpaceX, Blue Origin, Axiom, and others are operating at cadences and with innovation speeds that NASA can't match if it insists on traditional processes.

Astronauts who work with private space companies are using modern equipment and modern workflows. When they come back to work with NASA, they're comparing experiences. They're asking why NASA is slower. Why is NASA more bureaucratic. Why does NASA insist on older technology.

This puts pressure on NASA to modernize, not just technology but processes. Isaacman's decision to allow iPhones is partly about maintaining competitiveness in the market for astronaut talent and crew capability.

It's also about public perception. When private space missions look more modern and more accessible than government space missions, that sends a message. By allowing Artemis II astronauts to use iPhones and share modern photography, NASA is sending a message that the agency is current, forward-thinking, and leveraging the best technology.

The psychological impact of imagery matters. The Apollo astronauts' photographs of Earth from the Moon captivated the world partly because the images were good, but also because of what they represented: humanity at the cutting edge of technology. If Artemis II returns images captured on 2016 cameras, it sends a subtle message: we're behind the times. If it returns images captured on 2026 iPhones, it sends a different message: we're current and capable.

Stringent qualification requirements can increase project costs by 150% and delay timelines by 200%. Estimated data.

Training and Integration Challenges

You might assume that because astronauts are already familiar with iPhones on Earth, no training is needed. You'd be wrong. Training for space is always more complex than it seems.

First, there are mission-specific protocols. Where will the iPhones be stored? How do they interface with power systems? What's the charging procedure? How do crews avoid damaging them in the spacecraft environment? Will they be tethered to prevent them from floating away? All of these questions have operational implications.

Second, there are emergency procedures. What happens if an iPhone fails during critical operations? What's the backup plan? Are there other cameras available? Astronauts need to be trained on contingencies.

Third, there's the question of workflow integration. Astronauts will have limited time during their missions. Every activity is scheduled and optimized. Where does smartphone photography fit into the timeline? How does this integrate with existing documentation procedures? This requires careful planning.

NASA has extensive experience training astronauts with various equipment. The good news is that unlike specialized space cameras, astronauts already know how to use iPhones. The training burden is manageable.

But it's not negligible. Every piece of equipment that flies to space requires integration and training. iPhones are no exception.

The Future: Where This Leads

If this decision proves successful—and given the relatively low risk, it almost certainly will—it opens the door to further modernization of NASA's equipment philosophy.

Why not modern laptops instead of tablets? Why not modern wireless systems instead of legacy communications infrastructure? Why not modern sensors instead of older specialized equipment? Each of these questions might have good answers, but they should be deliberate answers, not reflexive adherence to tradition.

The iPhone decision might seem incremental, but it represents a fundamental shift in how NASA thinks about technology procurement and integration. It's a vote for pragmatism over excessive caution.

This could accelerate development of future lunar habitats, Mars missions, and other exploration objectives. Modern tools enable faster decision-making and more effective operations. An astronaut with a modern smartphone and modern computing equipment is more productive than one working with outdated technology.

It's also possible that successful smartphone integration in space will drive improvements in consumer technology. Manufacturers could optimize devices for space environments. We might eventually see phones specifically designed with the constraints of spaceflight in mind. That's an intriguing prospect.

Moreover, this decision sets a precedent for other space agencies and private companies. If NASA is comfortable with modern consumer electronics in space, others will likely follow. It normalizes the idea that space exploration doesn't require completely custom technology. Sometimes the best tool is the one that billions of people already use and understand.

The Human Element: Why This Matters

At its core, this decision is about recognizing the human element of space exploration. Astronauts aren't robots executing predetermined programs. They're human beings performing one of the most challenging and meaningful work any human can do.

Giving them modern tools that they choose to use, that they're familiar with, and that help them communicate with their families and share their experiences matters. It's respectful of their humanity.

The photographs that astronauts take are valuable scientifically. But they're also valuable culturally. They inspire people on Earth. They create connection. An astronaut's selfie with Earth in the background, transmitted almost instantly to the internet, creates a moment of shared human experience that's powerful and meaningful.

Isaacman explicitly framed this as being about "capturing special moments for families and sharing inspiring images and video with the world." This isn't incidental. It's central to the decision.

When you understand that space exploration ultimately serves human purposes—scientific discovery, yes, but also inspiration, exploration, and connection—then equipping crews with tools that facilitate those purposes makes complete sense.

NASA has always been about the frontier. About pushing boundaries. About doing things that haven't been done before. That mandate applies not just to where we go, but how we go. Using modern smartphones instead of obsolete cameras is a small but meaningful part of that.

Regulatory and Safety Implications

From a regulatory perspective, NASA's approval of iPhones for Artemis II sends signals through the entire aerospace and space industry. Other agencies watch NASA's decisions closely. If NASA is comfortable with modern consumer electronics, that provides cover for others to adopt similar approaches.

International space agencies, commercial operators, and even military space programs will likely point to NASA's approval as justification for their own decisions to use modern technology. The first mover in approving major changes often faces more scrutiny, but once approved, the path is established for others.

From a safety perspective, the approval process likely included thorough testing and validation. NASA wouldn't approve iPhones if there were genuine safety risks. But the fact that they approved them also means they concluded that the risks are acceptable and manageable.

This sets a precedent for risk-based decision making rather than requirement-based decision making. Instead of asking "Does this meet our standard requirements?" NASA asked "What are the actual risks, and are they acceptable?" This is a more sophisticated approach to engineering safety.

The Bottom Line: A Small Decision With Big Implications

Bringing iPhones to space might seem like a small decision. It's not. It represents a fundamental shift in how a major government space agency approaches technology adoption and crew capability.

For decades, NASA's approach to spaceflight equipment could be summarized as "space is different, so we need custom equipment designed from scratch." That made sense in many contexts. It still makes sense for critical life support, propulsion, and navigation systems.

But for documentation, communication, and crew capability, the new approach seems to be "if consumer technology is good enough, we should use it." This is pragmatic, efficient, and ultimately more effective.

The iPhones aboard Artemis II will enable better documentation of humanity's return to the Moon. They'll help astronauts capture moments that inspire the world. They'll demonstrate that NASA can balance caution with innovation, and that the agency can learn from others and adopt best practices.

And they'll probably take some absolutely stunning photographs.

FAQ

Why did NASA take so long to approve smartphones for space missions?

NASA's stringent approval processes for spaceflight hardware reflect the extremely challenging environment of space, where radiation, vacuum, thermal extremes, and vibration pose real engineering challenges. Historically, the agency preferred specialized, tested equipment over consumer devices. However, as Isaacman noted, these requirements accumulated over decades and sometimes became excessive relative to actual mission risks. The decision to allow iPhones represents a pragmatic reassessment of which requirements still serve their original purpose and which have become bureaucratic artifacts.

What specific testing did NASA conduct on iPhones for spaceflight?

While the exact testing parameters haven't been fully detailed publicly, NASA likely conducted targeted testing on radiation tolerance, thermal performance in vacuum conditions, battery safety, electromagnetic compatibility, and structural integrity during launch acceleration. Rather than running the complete qualification gauntlet for every component, NASA appears to have taken a mission-specific risk-based approach, focusing on failure modes relevant to the Artemis II environment. This accelerated timeline reflects Isaacman's emphasis on operational urgency and pragmatic engineering decisions.

Will astronauts receive cellular service with iPhones in space?

No. iPhones won't have cellular service in orbit or on the Moon because there's no cellular infrastructure in space. However, iPhones can connect to spacecraft WiFi systems, allowing communication through ground stations and mission control. The phones will be essentially offline from the broader internet but can function as cameras, video recorders, and local communication devices within the spacecraft. This is sufficient for the primary mission objectives of documentation and crew communication.

How will iPhone batteries be managed in the space environment?

Lithium batteries in spacecraft require careful monitoring and management because the space environment creates different thermal and electrical stresses than Earth conditions. NASA will implement specific battery management protocols, likely including temperature monitoring, charge cycling procedures, and isolation procedures in case of malfunction. While standard iPhone battery management systems work fine in normal operations, spaceflight requires additional safeguards and monitoring to prevent failures that could damage spacecraft systems.

Could other consumer electronics be approved for future space missions following this decision?

Very likely. The iPhone approval establishes a precedent for pragmatic evaluation of consumer technology based on mission-specific risk rather than blanket adherence to traditional aerospace qualification standards. This approach could extend to modern laptops, wireless systems, sensors, and other equipment where commercial technology meets or exceeds specialized aerospace alternatives. However, critical systems like life support, propulsion, and navigation will continue to use specialized, thoroughly validated hardware regardless of consumer alternatives.

What happens if an iPhone malfunctions during an Artemis mission?

Astronauts will have contingency procedures and backup documentation equipment available. A failed iPhone would be an inconvenience affecting photography and video capability, but not a mission-critical failure. Mission-essential documentation will continue through established procedures and equipment. This is fundamentally different from failures of critical systems like power, thermal control, or life support, which would trigger emergency protocols. Smartphones are tools for documentation and crew communication, not mission-essential infrastructure.

How does this decision compare to other space agencies' approaches?

Some private spaceflight companies and international space agencies have been using consumer electronics more liberally than NASA for several years. Axiom Space missions and SpaceX Crew Dragon operations have accommodated personal devices. This decision brings NASA's approach more in line with commercial spaceflight practices, recognizing that consumer technology has become reliable enough for spaceflight applications in non-critical roles. It also reflects NASA learning from competitors and adopting practices that have proven effective in the private sector.

Will iPhones be the only smartphones allowed on future NASA missions?

The decision specifically mentions iPhones for Crew-12 and Artemis II, but it's reasonable to expect that other modern smartphones with equivalent capabilities might eventually be approved through similar pragmatic qualification processes. The principle established isn't "only iPhones are allowed" but rather "we'll evaluate modern consumer technology based on actual mission requirements rather than automatic rejection." Future decisions will likely depend on technical capabilities, availability, and mission-specific requirements.

How will crew training incorporate smartphone usage in space?

While astronauts are already familiar with iPhones on Earth, spaceflight integration requires specific training on procedures, storage, power management, and emergency protocols. Training will address how to safely handle iPhones in the spacecraft environment, where to store them to prevent damage or loss in microgravity, charging procedures, backup procedures if devices fail, and integration with existing documentation workflows. The training burden is significantly less than for specialized space cameras, but it's not negligible.

What are the implications of this decision for NASA's organizational culture?

Isaacman's emphasis on "challenging long-standing requirements" signals a cultural shift toward questioning unnecessary bureaucracy and embracing pragmatic modernization. This decision puts pressure on NASA's engineering and procurement organizations to justify every requirement, not assume it's still necessary. Over time, this could accelerate technology adoption across the agency and create more responsive, efficient operations. However, it also requires institutional commitment to maintaining safety while becoming more agile—a balance that's always challenging for large organizations.

Conclusion

When NASA announced that Artemis II astronauts would be allowed to carry iPhones to the Moon, it might have sounded like a footnote to a much larger story. But it's not. It's a watershed moment that reveals something fundamental about how space agencies make decisions, what they value, and where the future of space exploration is heading.

For fifty years, NASA has relied on specialized, custom-built equipment designed from the ground up for spaceflight. That approach made sense and continues to make sense for critical systems where lives depend on absolute reliability. But somewhere along the way, the principle extended to all equipment, creating a bloated, expensive, and slow approval process for everything from cameras to communication devices.

Isaacman's decision to allow iPhones represents a recognition that modern consumer technology has become so reliable, so capable, and so universal that rejecting it in favor of obsolete alternatives is indefensible. It's a pragmatic embrace of reality.

The astronauts who walk on the Moon in the coming years will have the tools to document that extraordinary moment in ways that captivate the world. Their families will be able to see their experiences in real-time. The broader public will connect with space exploration in immediate, human ways. All because NASA decided to use the cameras that billions of people use every day.

Beyond the photographs, this decision matters because it signals a fundamental shift. NASA is willing to challenge its own assumptions. The agency can be conservative about safety while being progressive about processes and technology. Government space exploration can move faster and smarter without sacrificing safety or mission success.

As space exploration enters a new era with renewed focus on the Moon and eventual Mars missions, the ability to adopt modern technology rapidly and pragmatically will become increasingly important. NASA has taken a first step. How the agency follows through on this principle will determine whether space exploration can keep pace with the rapid technological change that defines our era.

The iPhone decision is small. But it opens doors. And sometimes, opening doors is the most important thing an organization can do.

Key Takeaways

- NASA approved iPhones for Artemis II astronauts, replacing outdated 2016 cameras with modern smartphone technology.

- This decision represents a pragmatic challenge to decades of accumulated bureaucratic requirements, prioritizing operational urgency over excessive caution.

- Smartphone cameras offer superior computational photography, video stabilization, and processing power compared to previously approved space cameras.

- The approval process was accelerated using mission-specific risk assessment rather than standard multi-year qualification gauntlet.

- This decision signals NASA's willingness to learn from private space companies and modernize its technology adoption approach.

Related Articles

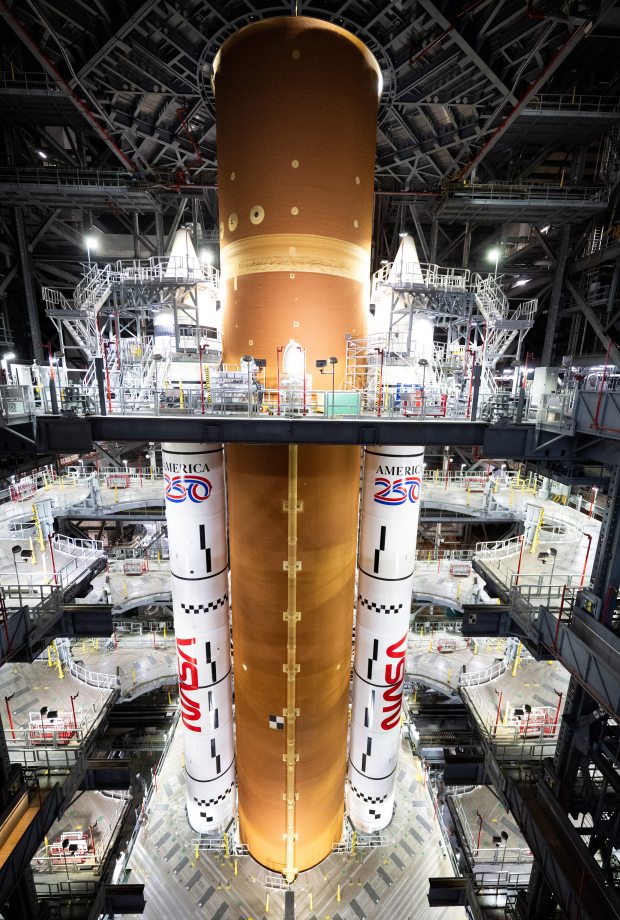

- NASA's SLS Rocket Problem: Why the Costliest Booster Flies So Slowly [2025]

- Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]

- Space-Based AI Compute: Why Musk's 3-Year Timeline is Unrealistic [2025]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: Inside Musk's $1.25 Trillion Data Center Gamble [2025]

- NASA Artemis 2 Launch Delayed to March: What the Hydrogen Leak Means [2025]

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: The 1 Million Satellite Gambit for AI Compute [2025]

![Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-nasa-finally-allows-astronauts-to-bring-iphones-to-space/image-1-1770307902050.jpg)