Netflix vs. Paramount: The $108B Streaming War Reshaping Hollywood [2025]

Hollywood is experiencing its most chaotic moment in decades. Not because of strikes, not because of production delays, but because the entire business model is shifting beneath everyone's feet.

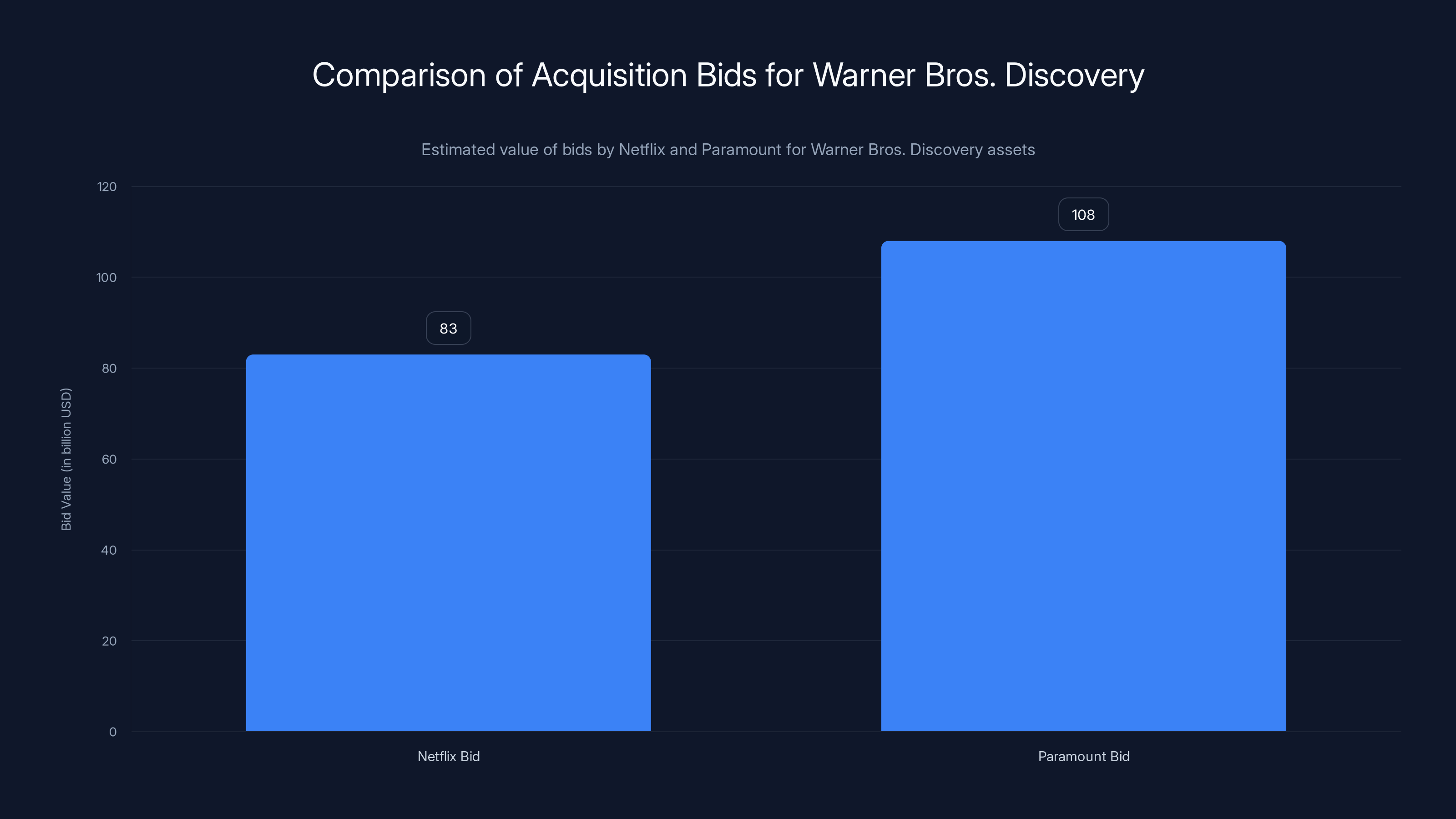

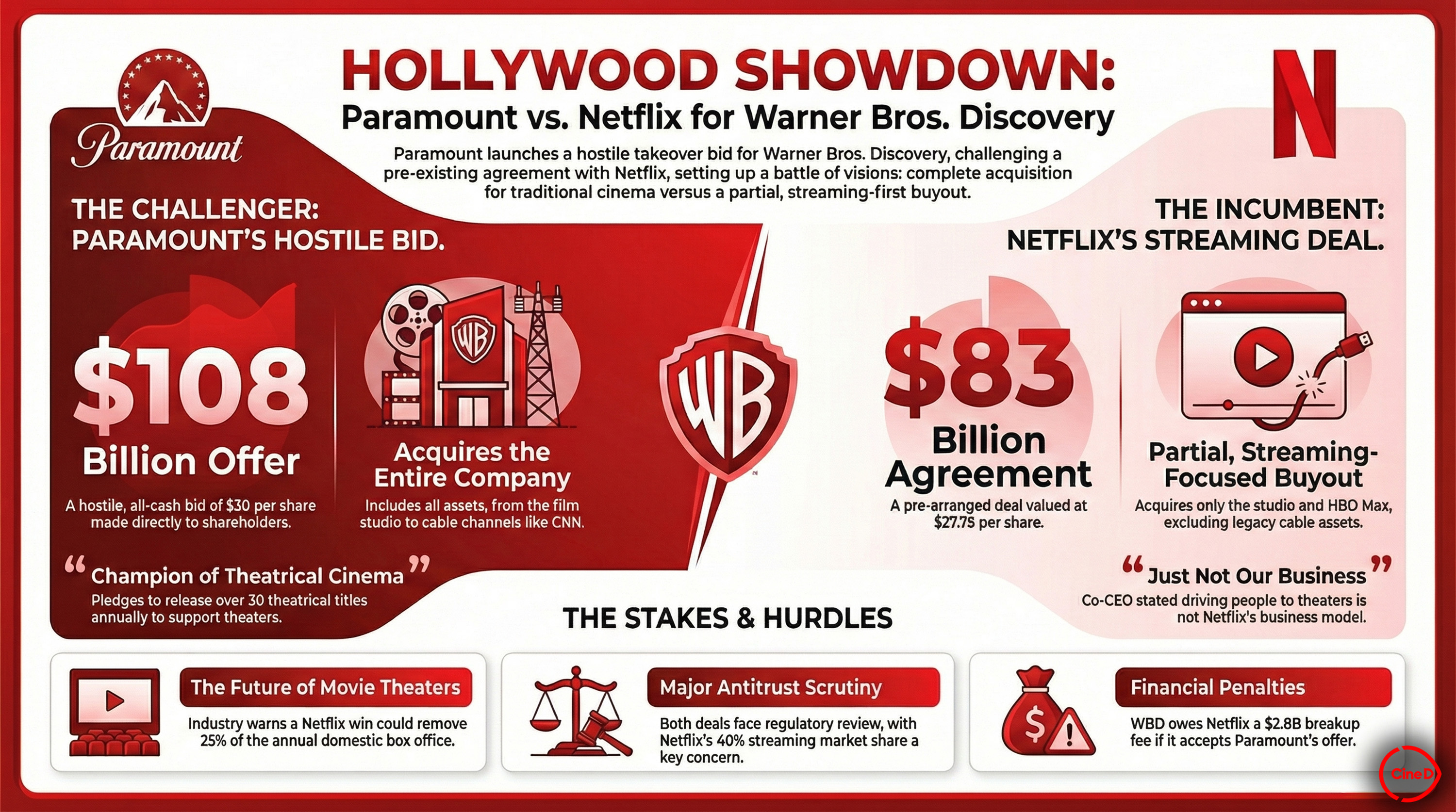

Right now, streaming giants are locked in a bidding war that feels ripped from Succession. Netflix offered

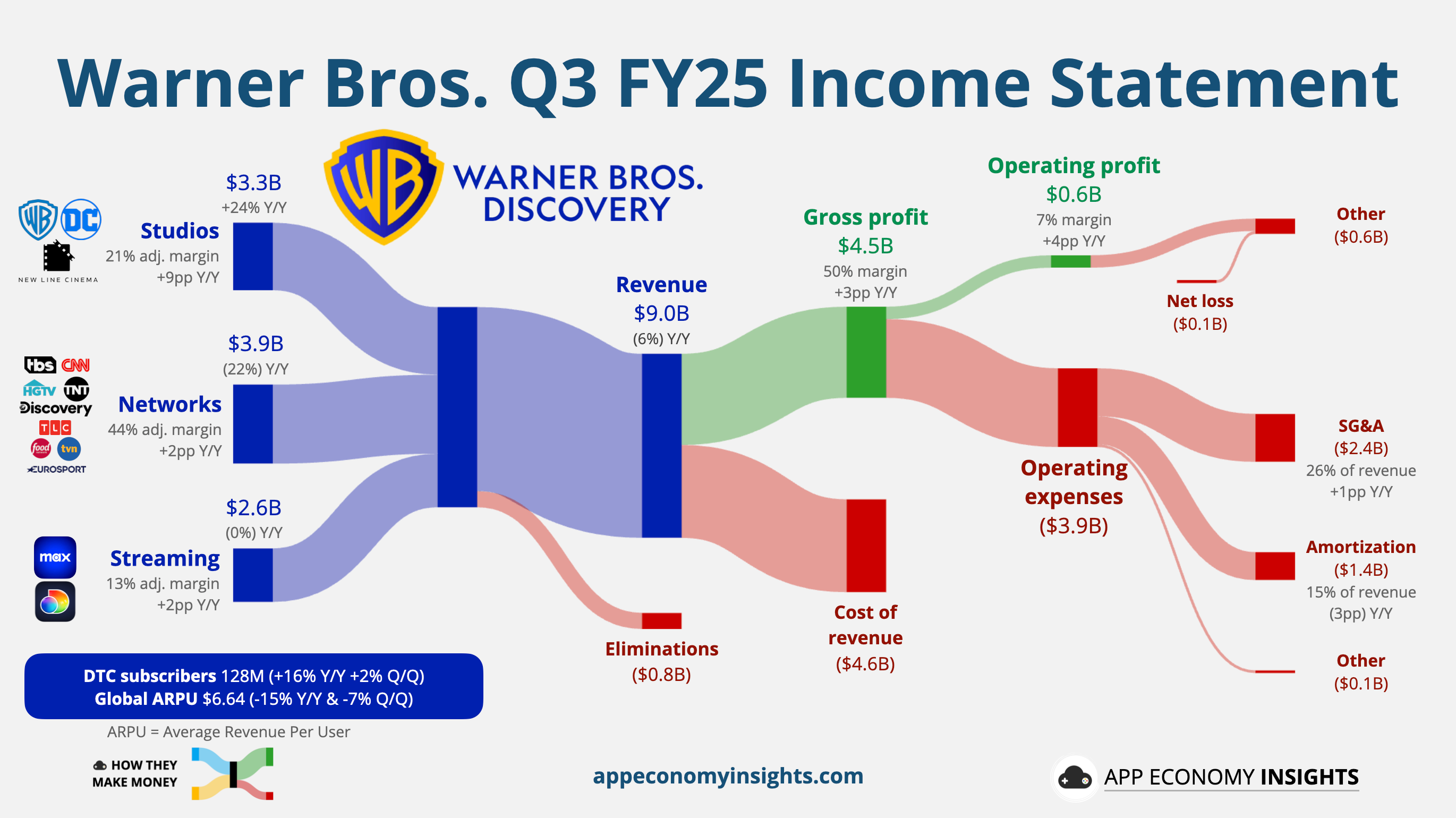

Here's what's actually happening: these companies aren't fighting over content libraries anymore. They're fighting over survival. The attention economy has fundamentally changed. Viewers now choose between Netflix, Disney+, Tik Tok, YouTube, gaming platforms, and AI-generated content. Traditional TV is collapsing. Linear advertising is evaporating. Profit margins that once seemed permanent are disappearing.

Streaming platforms built themselves on the promise of disrupting Hollywood. Now they're consuming Hollywood because they have to. Let me explain why this matters, how we got here, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- Netflix's $83B Warner Bros. bid positions the platform to own legendary franchises (DC Universe, Harry Potter, Game of Thrones) while controlling production and distribution. According to Reuters, Netflix is defending its bid amidst tepid market reactions.

- Paramount's hostile $108B counter-offer reflects desperation: David Ellison's company can't compete with Netflix's subscriber base and needs HBO's prestigious content immediately. Business Insider reports on the rejection of Paramount's bid by Warner Bros. Discovery.

- The real problem is that streaming itself is broken: Netflix burns cash on content while trying to maintain pricing power against price-sensitive consumers worldwide. Variety highlights Netflix's financial challenges despite its subscriber base.

- Cable channels are now liabilities, not assets, because cord-cutting continues accelerating and advertising revenue is collapsing across the industry. Yahoo Finance discusses the decline in traditional TV advertising.

- The merger trend is inevitable because scale matters now more than ever—only large, vertically-integrated companies can survive the shift to AI-generated content and micro-budget productions.

Paramount's bid of

Why Netflix Wants Warner Bros. Discovery (And Why It Might Fail)

Netflix's $83 billion bid for Warner Bros.' movie studios isn't about content nostalgia. It's about owning the factory.

Warner Bros. Pictures generates roughly $5-6 billion in annual revenue across theatrical releases, streaming rights, and international distribution. More importantly, it owns intellectual property that prints money: DC Universe, Harry Potter, the Wizarding World, Lord of the Rings, and Dune franchises. These aren't just content; they're multi-billion-dollar universes that span films, TV shows, merchandise, and theme parks.

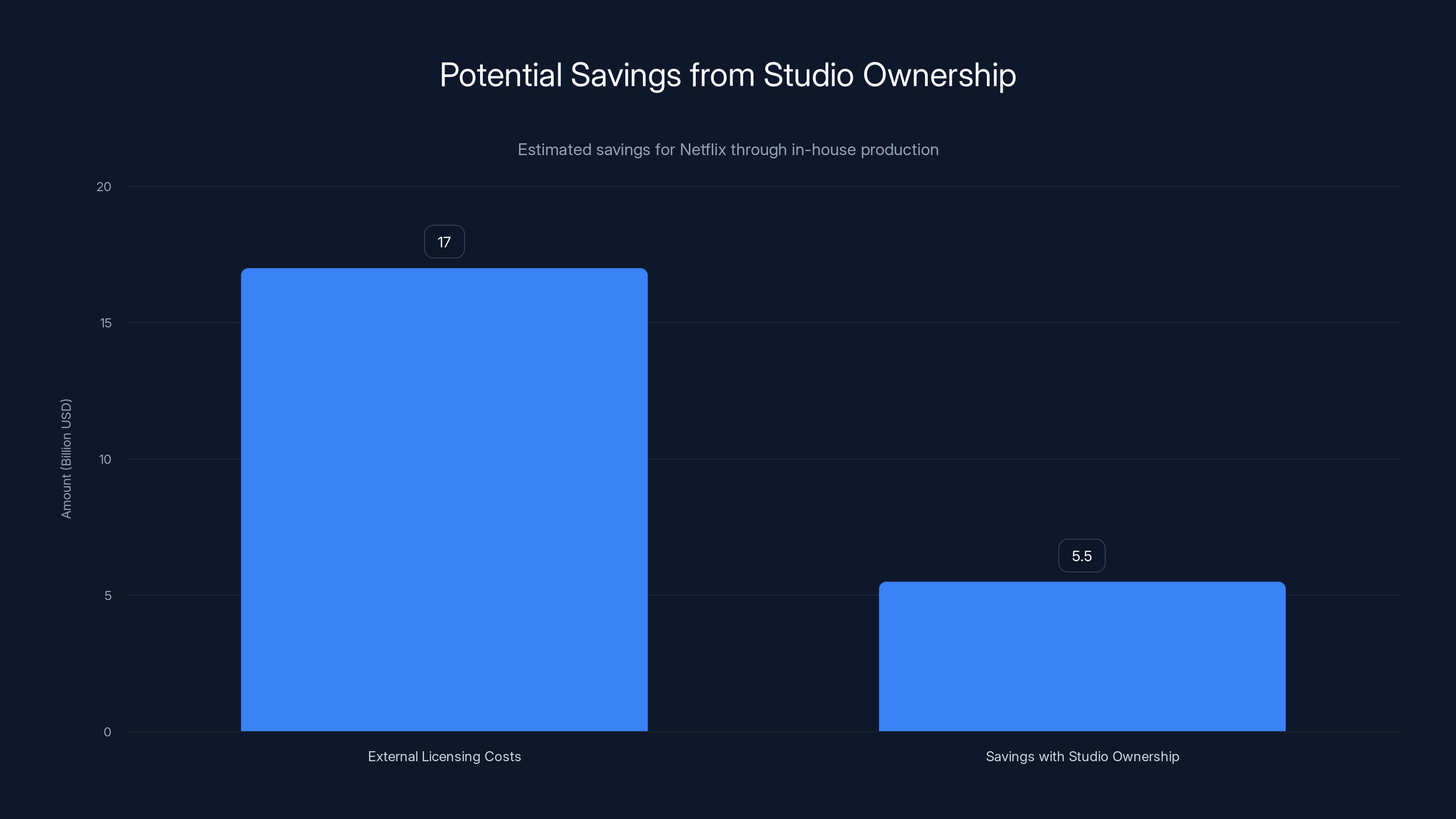

For Netflix, owning the production studio solves a brutal problem. The platform currently spends

If Netflix owns Warner Bros. Pictures, it controls the entire supply chain. No more licensing deals with studios that demand half the revenue. No more competing with theatrical releases that cannibalize streaming viewers. Warner Bros. can produce expensive tentpole films specifically designed for Netflix exclusivity, then windfall those franchises across merchandise, games, and international theatrical releases in markets where Netflix is weakest.

But here's the brutal catch: Netflix doesn't want HBO's cable channels. That's revealing. The platform looked at CNN, HBO Max's linear channel, and the sprawling cable portfolio and said, "No thanks." Why? Because cable is dying. Cord-cutting accelerated to 10.5 million subscribers lost in 2024 alone, according to industry estimates. Linear television advertising—which funds cable channels—has collapsed. Advertisers are fleeing to digital platforms that offer better targeting and measurable ROI.

Netflix recognizes that owning HBO's cable channels would be buying liabilities wrapped in nostalgia. The brand is legendary. The content is prestigious. But the economics are toxic.

Paramount's Desperation Play: Why Ellison Wants It All

David Ellison's hostile bid tells a completely different story. At $108 billion for the entire package, Paramount is betting everything on a strategy that might not work.

Paramount Pictures and Paramount Global (the parent company owning cable channels CBS, MTV, Comedy Central, BET, and Nickelodeon) is drowning. The company's streaming platform, Paramount+, has roughly 60 million subscribers compared to Netflix's 232 million. More critically, Paramount's cable channels are hemorrhaging subscribers and advertising revenue. Revenue from the company's TV media segment fell 13% year-over-year, with advertising down even more steeply.

Ellison's logic is simple, even if brutal: if Paramount can't beat Netflix at streaming, it needs to own HBO and use that prestige content to compete. HBO Max has 57 million subscribers and maintains higher-quality content perception than Paramount+. Adding HBO's franchises (Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon, The Last of Us) to Paramount's existing properties (Star Trek, Yellowstone, Avatar) would create a content powerhouse theoretically capable of challenging Netflix's dominance.

But Ellison is also buying the cable channels. Why? Because he believes in vertical integration and synergy—a strategy that's worked in tech but has repeatedly failed in media. He thinks owning cable channels gives him leverage with traditional distributors, international markets, and advertisers who still value traditional TV.

Here's the reality: Ellison inherited Oracle wealth and tech credibility but lacks deep media expertise. His vision feels like applying Silicon Valley playbooks to an industry where those playbooks have failed repeatedly. The Venn diagram of "tech billionaires who understand media" and "tech billionaires who actually executed media strategy successfully" is a single dot, and that dot is probably Elon Musk with X, which is its own kind of disaster.

Paramount also has the Trump administration's goodwill, which might matter for regulatory approval. But goodwill doesn't solve the core problem: even if Paramount buys Warner Bros., it still can't match Netflix's subscriber economics or production efficiency.

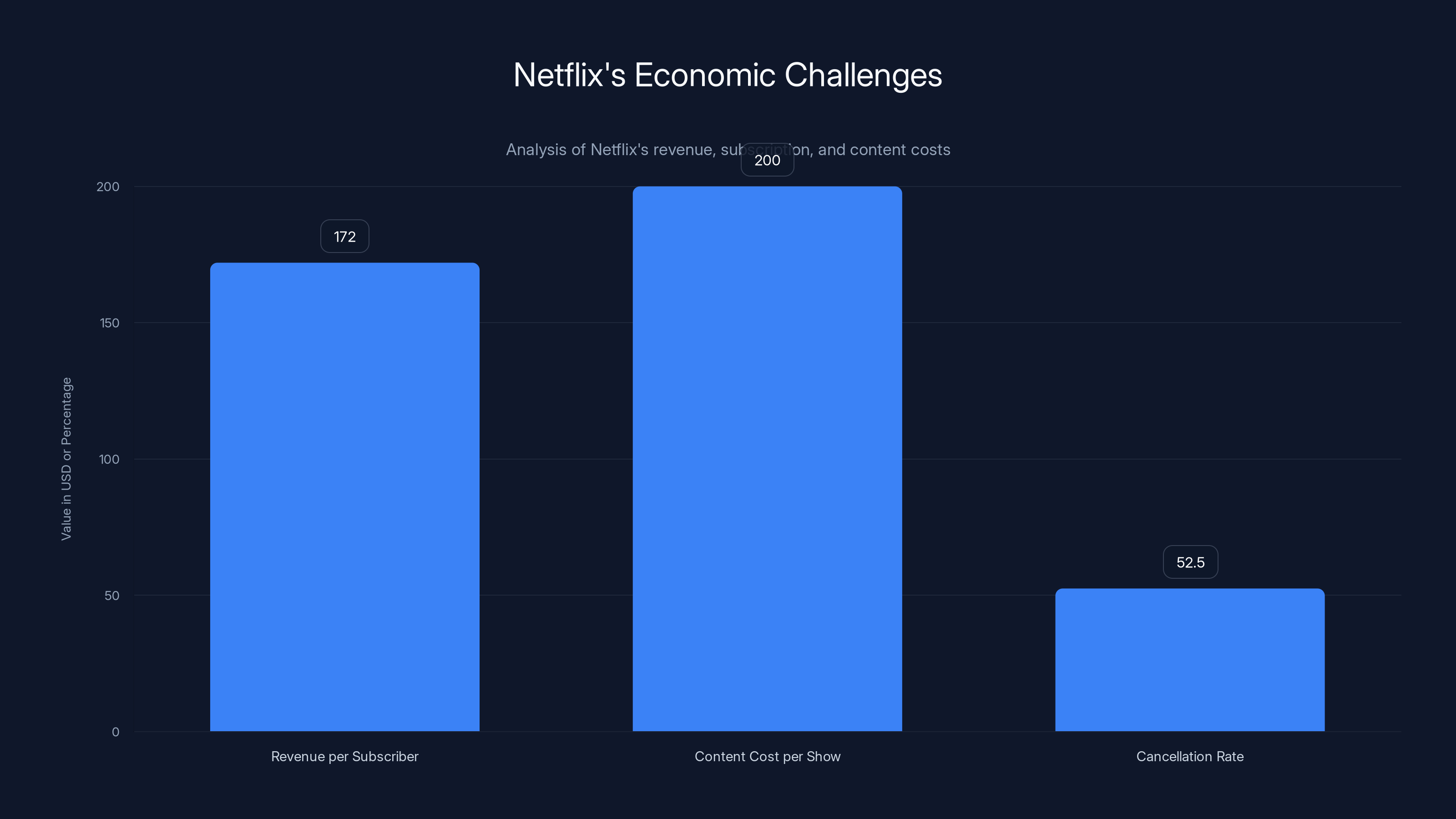

Netflix earns

The Real Problem: Streaming Economics Are Broken

Both bids—Netflix's

They assume that owning more content franchises will generate enough value to justify the acquisition cost. But the streaming economics story is far grimmer than either company publicly admits.

Netflix has built a

Meanwhile, content costs don't scale linearly with subscribers. Netflix's top shows cost $200 million per season or more. A show needs to entertain millions of people to justify that spend, and most shows don't. Netflix's cancellation rate hovers around 50-55% for new shows. That means the platform is betting half its content budget on shows that get cancelled before a second season.

This is why consolidation looks attractive. If Netflix owns Warner Bros. Pictures, it doesn't need to license The Batman or The Penguin from a studio that demands revenue-sharing. It makes the film in-house, releases it theatrically for brand prestige and international revenue, then releases it on Netflix after the theatrical window. That's vertical integration.

But even vertical integration doesn't solve the fundamental problem: there's only so much content people can watch. You can't force 232 million subscribers to suddenly consume 50% more entertainment. You can move them from watching other platforms' content to your own, but you can't expand the total attention pie.

Streaming was supposed to be more profitable than cable. The math seemed simple: cable TV had 50-100 channels, and viewers paid

Why Cable Channels Are Liabilities in 2025

Paramount's insistence on acquiring cable channels reveals the generational disconnect between old Hollywood and the reality of media consumption.

Linear television is not just declining—it's collapsing. Cable TV viewership fell 26% year-over-year in 2024, according to Nielsen data. That's not a slowdown. That's a cliff. The channels that made cable providers billions are now worth less every single year.

Advertising revenue follows viewership. Major advertisers have shifted budgets from traditional TV to YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and other digital platforms where they can target specific demographics and measure engagement directly. A 60-second TV commercial during a sitcom might reach 2 million viewers. A TikTok video might reach 500 million.

Cable companies historically bundled channels together and forced consumers to pay for the whole package. MTV was valuable because you had to buy it as part of the cable bundle to get HBO and ESPN. Now consumers can pick individual services. Who chooses MTV? Nickelodeon without the bundling leverage? They're fighting for relevance in a world where kids watch YouTube and TikTok.

Ellison's strategy assumes he can revive these channels or repurpose them. Maybe he'd shift them to adult-oriented content to compete with streaming. Maybe he'd use them for advertising-supported tiers. But he's fundamentally betting against demographic trends and consumer behavior that have been accelerating for a decade.

Netflix's refusal to acquire cable channels is the smartest part of its bid. The company looked at CNN, HBO's linear channel, and the cable portfolio and calculated: "These are money-losers with shrinking audiences. We'd rather own the movies and shows." That's accurate.

The Intellectual Property Goldmine (And Why It Matters Less Than You Think)

Both Netflix and Paramount are bidding this much money primarily for intellectual property: DC Universe, Harry Potter, Dune, Game of Thrones, Star Trek, Avatar.

These franchises have generated $30+ billion in global box office revenue across theatrical releases, merchandise, and related media over the past 15 years. They're crown jewels. A film or show with established intellectual property has a higher success probability and lower marketing cost than original content.

But IP value is collapsing in streaming economics. Here's why:

Theatrical vs. Streaming: A DC Universe film cost $200-250 million to produce and market. It generates theatrical revenue plus home video, then eventually streams on HBO. Theatrical releases build global brand awareness and cultural relevance that streaming releases struggle to replicate. But theatrical is declining. Fewer people go to theaters. Competition for screens is brutal. A streaming-exclusive release of the same film? It reaches 30% of the global audience versus theatrical's 70%.

Franchise Fatigue: Audiences have been swimming in DC and Marvel content for 15 years. Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman—these characters are oversaturated. Yes, The Penguin and The Last of Us generated critical acclaim, but they still underperformed commercial expectations. Franchises don't guarantee success anymore. They guarantee cost.

AI-Generated Content: This is the real wildcard. As AI video generation improves, the value of owning legacy IP diminishes. Studios won't be able to generate new Batman films with AI (yet), but they'll be able to generate 90% of mid-budget content. That commoditizes the creative process and makes established franchises relatively more valuable because they differentiate from AI-spam. But for how long?

By owning a major studio, Netflix could save an estimated $5-7 billion annually, reducing external licensing costs by 30-40%. Estimated data.

The Consolidation Wave: Why Streaming Giants Must Merge or Die

Netflix's bid and Paramount's counter-offer aren't unique. They're symptoms of a consolidation wave that's reshaping the entire entertainment industry.

Disney owns Marvel, Pixar, National Geographic, ESPN, and ABC. Amazon owns MGM Studios and has a massive streaming platform. Apple is building a prestige content library. Warner Bros. Discovery owns everything except now potentially being acquired by Netflix. Paramount is desperately consolidating. Sony is the only major studio trying to remain independent, and it's facing enormous pressure.

Why is consolidation inevitable? Scale. Streaming requires spending billions annually on content to maintain subscriber growth. Only companies with diversified revenue streams can sustain that spending. Netflix can't cut content budgets without subscriber churn. But Netflix also can't raise prices without hitting elasticity limits. Owning production studios lets Netflix control input costs and reduce dependency on external studios.

Think about it mathematically. Netflix has 232 million subscribers at an average revenue of

At scale, that's an extra

Paramount's $108 billion bid is less justified. The company has fewer subscribers, lower margins, and less pricing power. The math works only if Ellison can dramatically improve Paramount+'s subscriber acquisition or successfully package HBO + Paramount + cable channels into a bundled product that commands premium pricing. That hasn't worked for any media company in history.

The Trump Administration and Regulatory Approval

Both bids require regulatory approval, which is suddenly complicated by politics.

The Trump administration has expressed skepticism of mega-mergers and consolidation, particularly in media. However, it's also expressed friendliness toward Paramount's Ellison specifically, who has cultivated relationships with Trump and his advisors.

This is relevant because antitrust enforcement could block either deal. The Federal Trade Commission (under Biden administration appointees) had been aggressive on tech mergers. The new administration might be more permissive for deals that appear pro-competitive (Netflix gaining more leverage against cable companies) and less permissive for deals that consolidate media in ways that reduce viewpoint diversity.

Paramount's bid might have a regulatory advantage: Ellison's political connections could smooth approval. But Netflix's bid might be safer from an antitrust perspective because breaking apart Warner Bros. Discovery rather than consolidating it further looks less anticompetitive.

However, here's the dark horse scenario: the government might approve Netflix's bid to keep Paramount weaker, or it might block Netflix's bid to prevent the company from becoming too dominant. Regulatory logic in media is opaque and often contradictory.

Both companies are likely lobbying heavily, hiring DC firms, and leveraging political connections. The winning bid might be determined not by superior business strategy but by superior political access.

Why Content Consolidation Alone Won't Save Streaming

Both Netflix and Paramount are assuming that the core problem with streaming is insufficient content quality or insufficient franchise value. But that's not the problem.

The problem is that streaming subscription prices are reaching equilibrium at lower prices than cable, while content production costs are identical or higher. You can't solve math.

Imagine Netflix successfully acquires Warner Bros. In-house production costs decrease. Margins improve. But what then? Netflix can't raise subscription prices to $25/month without losing 20-30% of subscribers in developed markets. It can't bundle content with other services without cannibalizing core streaming margins. It can't force password-sharing users to pay without driving them to piracy or competitors.

The streaming industry is discovering what every disruptive technology learns: disruption is profitable in the growth phase but becomes brutal in the mature phase. Netflix disrupted cable TV and achieved massive subscriber growth. But now Netflix is mature. The company has added 140 million subscribers since 2015 but faces slowing growth because it's approached market saturation in high-income countries.

Content consolidation helps, but it doesn't solve the fundamental problem: streaming margins are permanently lower than cable TV margins, and there's no way to change that.

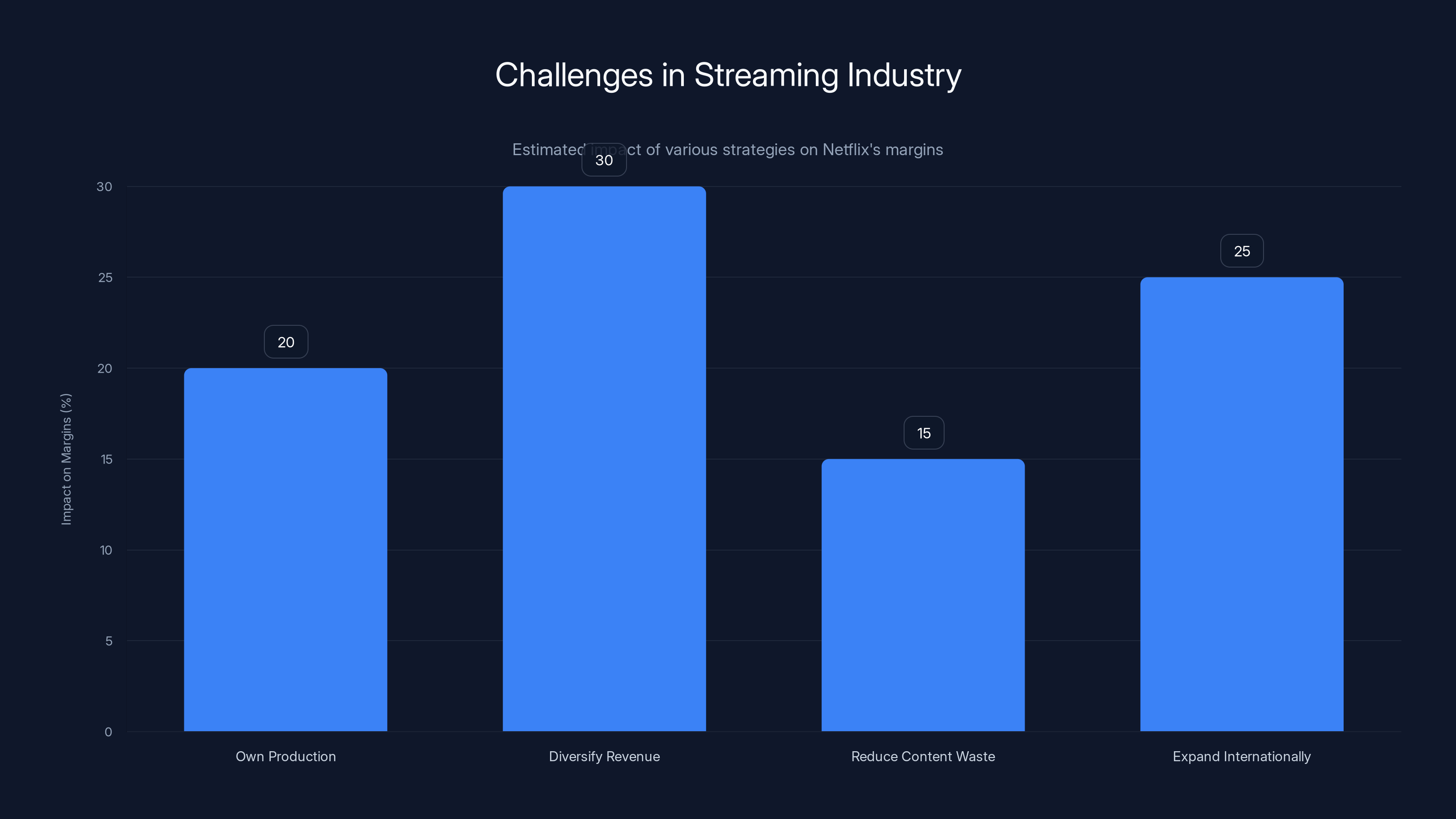

What actually matters is differentiation and efficiency. Netflix needs to:

- Own production to reduce licensing costs and increase margins (hence the Warner Bros. bid)

- Diversify revenue beyond subscriptions to include advertising, gaming, and merchandise

- Reduce content waste by improving show cancellation predictability and avoiding expensive flops

- Expand internationally where price elasticity is higher and subscriber growth is still possible

Owning Warner Bros. helps with #1 and partially with #3. It doesn't help with #2, #3, or #4 as much as investors hope.

Estimated data suggests that diversifying revenue could have the highest impact on improving Netflix's margins, followed by international expansion and owning production.

The Cable Channel Problem: Why Paramount Is Fighting to Acquire Liabilities

Paramount's insistence on acquiring cable channels reveals why the company is desperate and why its bid is probably doomed.

Cable channels were valuable as bundled leverage. Cable TV providers forced consumers to buy 100-channel packages to get HBO and ESPN. Paramount owned MTV, BET, Comedy Central, and Nickelodeon—channels that millions of people watched. That leverage generated billions in advertising revenue.

But bundling is dead. Consumers now pick individual services. They don't want MTV. They want TikTok. They don't want Nickelodeon. They want YouTube Kids. The channels still exist, but they're losing relevance and profitability every single year.

Paramount wants to acquire these channels as part of the Warner Bros. deal because Ellison believes in vertical integration and bundling. His theory: own HBO, own Paramount+, own cable channels, bundle them together, and create a mega-service that competes with Netflix across multiple demographics (ads, prestige content, family content, niche channels).

But bundling only works if you have leverage. Netflix has leverage because it's the market leader. Disney has leverage because it owns ESPN (which people actually pay for). Paramount has leverage only if it can convince consumers that MTV + Nickelodeon + Paramount+ + HBO + cable channels justifies a $25-30/month price point. That's not happening.

Ellison's cable channel acquisition is the deal's biggest red flag. He's paying for legacy assets that are worth less every single year. It's like paying premium prices for a newspaper empire in 2010—historically prestigious but economically doomed.

How AI Video Will Reshape the Entire Deal

Neither Netflix nor Paramount is publicly discussing the elephant in the room: AI-generated video is coming, and it will destroy the economics of both bids.

As of early 2025, AI video generation is still in early stages. Open AI's Sora, Anthropic's initiatives, and various open-source models can generate short video clips, but not full-length narratives with consistent characters, coherent plotting, and emotional impact.

But the trajectory is clear. Within 3-5 years, AI video generation will be capable of producing:

- Secondary content: Spinoffs, side stories, prequels, and sequels within established franchises at a fraction of traditional production cost

- Localized content: Dubbing and re-editing content for different markets without reshooting expensive scenes

- Derivative content: Infinite variations of stories, characters, and scenarios for different demographics

When that happens, the value of legacy franchises changes dramatically. You don't need to pay $200 million for a Batman sequel if you can generate 100 Batman-adjacent stories with AI at a fraction of the cost. The franchise IP becomes more valuable (as differentiation against AI-spam) but also less defensible (because AI can create infinite variations).

This is probably why Netflix is moving cautiously on the Warner Bros. deal. The company likely understands that in a 5-10 year timeframe, the economics of owning expensive production studios might become unfavorable. Better to lock in a good price now and figure out the AI strategy later.

Paramount doesn't seem to be thinking about this at all. Ellison's bet assumes traditional media economics persist for another 10-15 years. That's a gamble that might look very foolish by 2030.

The Alternative: What If Neither Deal Closes?

There's a real possibility that both bids fail.

Warner Bros.' current leadership, under David Zaslav, might refuse both offers. The company could split into separate streaming and studio entities. Paramount could remain independent, continue bleeding subscribers, and eventually find a buyer at a much lower price (or merge with a tech company desperate for content assets).

If Netflix's bid fails, the company could pivot to organic studio growth or smaller acquisitions. It's working fine at 232 million subscribers. Margins are expanding. The company doesn't need Warner Bros. to be successful; it needs Warner Bros. to maintain margins in a competitive landscape. That's different.

If Paramount's bid fails, Ellison could double down on streaming-only consolidation, jettisoning cable channels and focusing on building a Netflix competitor with HBO + Paramount + new investment. That's actually a more defensible strategy than bundling cable channels.

Or both companies fail to acquire Warner Bros., and someone else swoops in: Apple, Amazon, or a private equity consortium willing to bet on media consolidation.

The most likely scenario remains that Netflix wins the Warner Bros. bid, but the deal faces regulatory delays and ultimately costs more than $83 billion when everything is done. Paramount's hostile offer will be rejected, and Ellison will refocus on organic streaming growth or pursue smaller bolt-on acquisitions.

But here's the thing: even if Netflix wins and the deal closes, the company still faces the same fundamental challenge—streaming margins are permanently lower than cable TV, and content consolidation is a marginal improvement, not a solution.

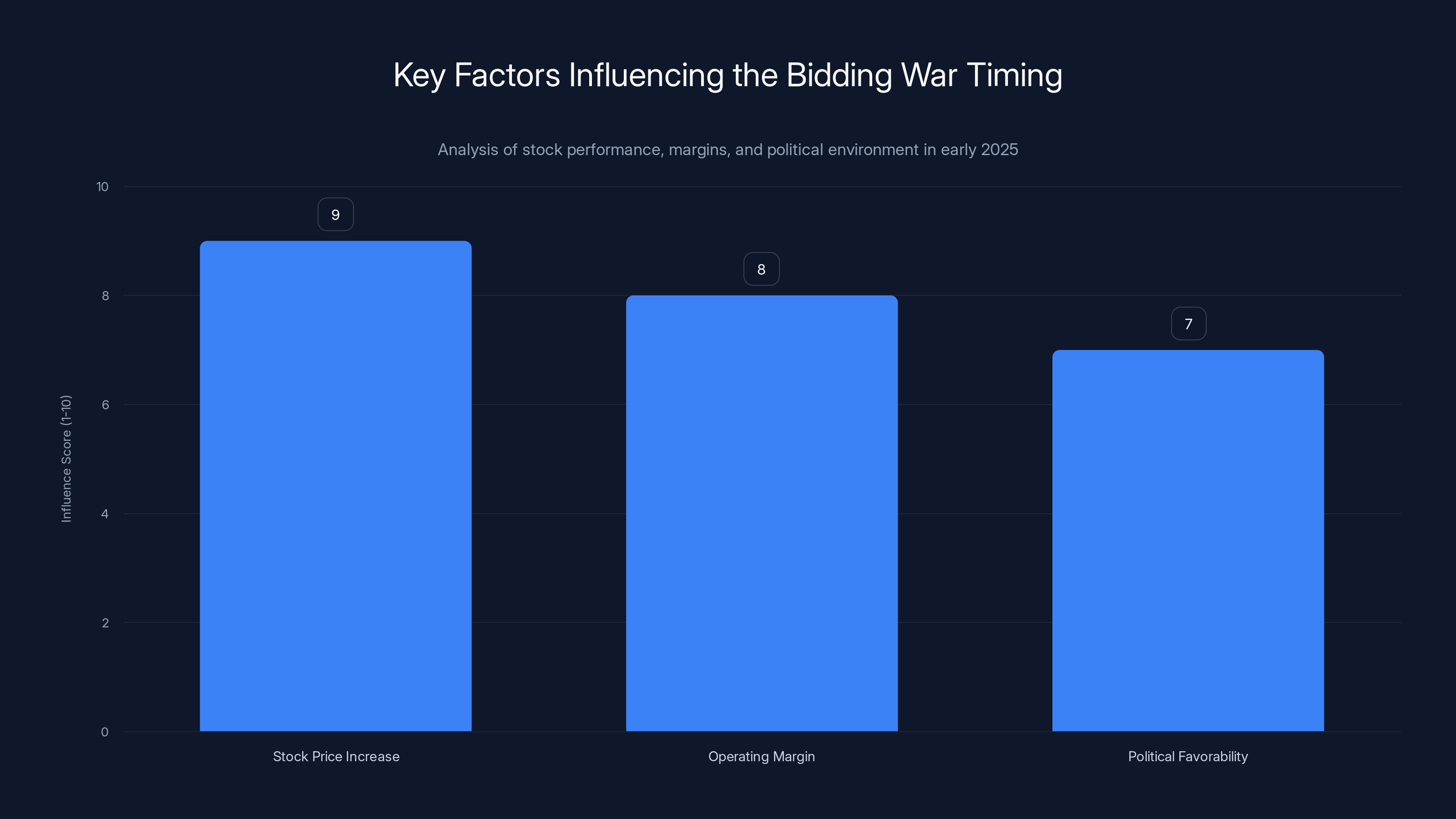

Stock price increase has the highest influence on the timing of the bidding war, followed by operating margin improvements and political favorability. Estimated data based on described factors.

What This Means for Consumers

If Netflix acquires Warner Bros., expect these changes within 2-3 years:

-

Fewer Warner Bros. films on other platforms: NBC, Amazon Prime Video, and other competitors will lose access to new Warner Bros. theatrical releases. These will stream exclusively on Netflix, faster than current release windows.

-

Higher Netflix prices: The company will raise subscription tiers, bundle services, and push ads to maintain margins. Expect a $25-30/month premium tier with no ads and exclusive content.

-

More DC Universe content: Netflix will rapidly expand DC Studios output, launching spinoffs, limited series, and animated content. Some will be excellent. Most will be forgotten.

-

International differentiation: Netflix will localize Warner Bros. franchises aggressively for markets where it's weak, producing local-language films and shows within established IP universes.

-

Slower theatrical releases: Warner Bros. will shift to shorter theatrical windows (10-14 days) before Netflix drops films. This hurts theater chains and changes consumer behavior around theatrical viewing.

If Paramount somehow wins, expect chaos: overlapping streaming services, confused branding, delayed content, and massive layoffs as Paramount consolidates duplicate functions across Paramount+, HBO Max, and cable channels. Paramount would probably rebrand everything under a single umbrella (likely HBO+) within 3 years and gradually sunset cable channels.

For consumers, more consolidation means fewer choices for streaming services but potentially better content quality as companies invest in flagship franchises. It also means higher subscription costs as companies face margin pressure.

The Bigger Picture: Hollywood's Structural Crisis

The Netflix-Paramount bidding war is just the visible symptom of a much deeper crisis.

Traditional media economics are broken. Cable TV is dying. Theatrical is declining. Streaming is mature and less profitable than expected. Traditional advertising is shifting to digital. Consumers are fatigued by subscription costs and fragmentation.

Hollywood is trying to solve these problems through consolidation, but consolidation can't change the fundamental math: there's only so much entertainment people can consume, and only so much they're willing to pay for it.

The real innovation isn't happening in boardrooms where executives bid billions for legacy assets. It's happening on TikTok, YouTube, Twitch, and Discord where creators reach audiences directly without studios, without TV deals, without theatrical releases.

It's happening in indie game studios making narrative-driven games that compete for attention with films and TV. It's happening in AI companies building tools that let one person create what used to require a 200-person production team.

Netflix and Paramount are fighting for control of the past. The future is being built somewhere else.

Paramount's

Historical Context: How We Got Here

Understanding today's consolidation requires understanding the last 25 years of media mismanagement.

In 2000, AOL merged with Time Warner in what's now widely regarded as one of history's worst deals. The combined company owned everything: cable networks (HBO, CNN), movie studios (Warner Bros., New Line), music labels (Warner Music Group), and the fastest-growing internet company on Earth (AOL). Theoretically, vertical integration would create unprecedented synergies.

Instead, the deal destroyed shareholder value. AOL's dial-up model was obsolete within 5 years. Time Warner's culture couldn't absorb an internet company. The combined company spent the next decade fighting internal turf wars while Netflix, Google, and Amazon ate their lunch.

In 2009, AT&T acquired T-Mobile... no wait, AT&T's failed T-Mobile acquisition was 2011. Let me reset: in 2015, AT&T acquired Direc TV for $49 billion. The pitch was simple: own the pipes and the content. Bundle them. Control the customer relationship. Maximize profit.

Instead, cord-cutting accelerated. Direc TV's subscriber base collapsed. AT&T spent the next decade trying to fix the failed acquisition, eventually spinning it off at a massive loss. The company destroyed $50+ billion in shareholder value on a deal that was supposed to create synergies.

Then there was the Warner Media era under Jeff Bewkes and his successor Jason Kilar. After AT&T bought Time Warner in 2016, they rebranded it Warner Media and tried to build a streaming service to compete with Netflix. The service launched in 2020 with massive investment and aggressive content spending. But AT&T was fundamentally a telecom company trying to compete in media. Decision-making was slow. Priorities conflicted. Content strategy was inconsistent.

By 2022, AT&T spun off Warner Media and merged it with Discovery. The new company, Warner Bros. Discovery, immediately raised prices, cut content budgets, and made controversial decisions like removing Batgirl and Scooby Doo from the platform to save money on taxes. Subscriber growth stalled. The stock price fell.

Now the company is being sold (or possibly acquired) because the experiment failed. That's the context for today's deals. Every major media company has tried consolidation. Most deals have failed or underperformed. But the alternative—remaining independent—looks even more difficult. So consolidation continues, even though history suggests it usually fails.

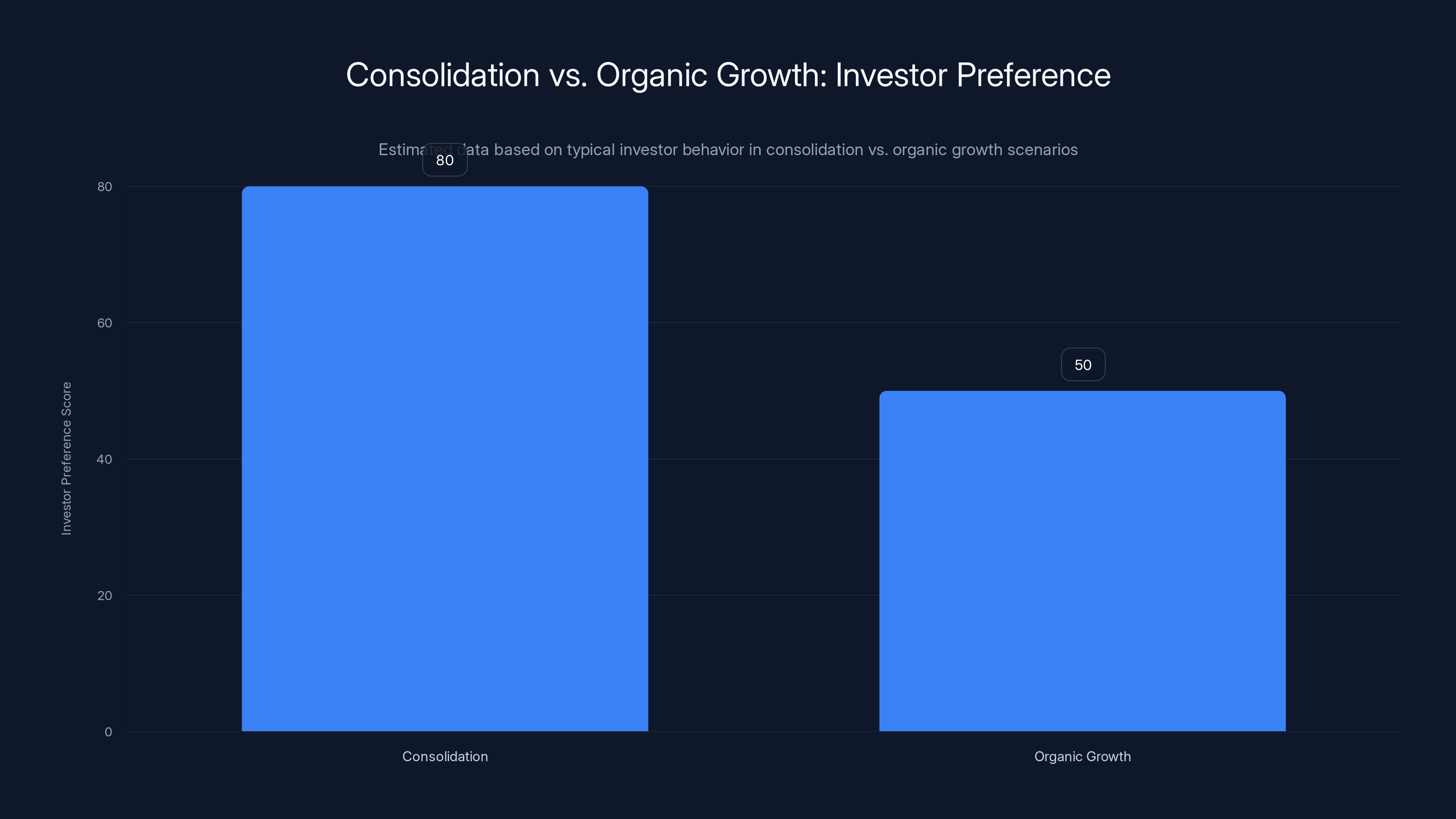

Investors show a higher preference for consolidation (score: 80) due to clear, immediate value creation, compared to organic growth (score: 50), which is slower and uncertain. Estimated data.

Why Wall Street Loves Consolidation (Even Though It Usually Fails)

Wall Street analysts and investors love consolidation because it's clean, measurable, and offers clear value creation narratives.

Consolidation story: Netflix buys Warner Bros. → Cost synergies of $5 billion annually → Price target increases 20% → Investors buy. It's easy to model, easy to present to board members, easy to justify in shareholder meetings.

Organic growth story: Netflix invests in original content, improves production efficiency, expands internationally → Margins improve 2-3% annually → Investors... get bored. It's slow. It's uncertain. It requires execution over 5-10 years.

Investors would rather have a clear 20% value creation story from consolidation than a 30% value creation story from organic growth that takes a decade and depends on execution. Consolidation is a one-time event. Organic growth is ongoing business operations.

But this bias toward consolidation is exactly why previous deals have failed. They sound better in finance models than they work in reality. Integration is harder than predicted. Synergies don't materialize. Corporate cultures clash. Customers leave.

Netflix is probably aware of this from Netflix's perspective because the company has acquired smaller studios and gaming companies in the past. But acquiring a studio of Warner Bros.' size is different. The integration complexity is exponentially higher.

Paramount is probably not aware of this because Ellison hasn't integrated major media companies before. His Oracle background is tech, where consolidation is more successful because software companies are easier to integrate than creative organizations.

The Real Reason Studios Keep Getting Sold

Why do media companies keep getting sold at premium prices even though the acquirers consistently fail to improve performance?

Part of the answer is CEO incentives. When a CEO receives a bid for their company, they have a fiduciary duty to shareholders to consider it seriously. If the bid is significantly above the current stock price, rejecting it can trigger shareholder lawsuits. That's why CEOs often accept bids that look bad from a strategic perspective—they're protecting themselves legally and personally (via severance packages and employment deals).

Part of the answer is distressed asset pricing. Warner Bros. Discovery's stock has been beaten down because investors have lost confidence in the company's ability to compete with Netflix and stabilize its business. When investors lose confidence, stock prices fall. When stock prices fall, the company becomes an attractive acquisition target. The acquirer (Netflix, Paramount) believes they can succeed where current management failed, even though history suggests otherwise.

Part of the answer is strategic optionality. Netflix doesn't strictly need Warner Bros. to remain competitive. But owning Warner Bros. gives Netflix strategic options: better margins through vertical integration, control over release windows, international distribution advantages, and IP assets that competitors can't access. These options have value, even if they're not guaranteed.

Part of the answer is desperation. Paramount is bidding so aggressively because the company is desperate. Ellison sees Paramount+ failing to compete, streaming economics deteriorating, and cable collapsing. The company's stock price reflects this desperation. A major acquisition is a Hail Mary pass—it won't necessarily work, but the alternative (slow decline) looks worse to a board of directors and shareholders.

So studios keep getting sold because CEOs have incentives to sell, investors lose confidence and push down stock prices, and acquirers believe they'll succeed where current management failed. That creates a cycle of consolidation even though most deals underperform.

The Timing: Why Now?

Why is the bidding war happening now, in January 2025, rather than a year ago or a year from now?

Three factors:

1. Stock prices: Tech stocks have rallied sharply in late 2024 and early 2025. Netflix's stock price is up 45% in the past 12 months. That increases Netflix's ability to do deals (it can use stock as currency) and increases shareholders' willingness to accept complex deals in exchange for the upside.

2. Margin improvement: Netflix has been improving margins through price increases and advertising. The company posted **

3. Political environment: The Trump administration has been friendly toward Ellison and skeptical of large tech platforms like Netflix. That creates a brief window where Paramount's hostile bid might receive favorable regulatory treatment (or Netflix's bid might face delays). Smart executives move quickly when political winds change.

But the deeper reason is that streaming has matured. Netflix, Disney+, and other platforms are approaching saturation in developed markets. Growth is slowing. Margins are lower than expected. Investors want consolidation because organic growth looks insufficiently exciting. That creates a window where acquisitions seem attractive.

What Netflix Is Really Buying

On the surface, Netflix is buying Warner Bros.' production studios and franchises.

But what Netflix is really buying is optionality in a disruptive landscape.

Here's the deeper logic: Netflix doesn't know if streaming will remain the dominant form of entertainment in 10 years. Maybe AI video replaces traditional production. Maybe gaming and interactive content dominate. Maybe some new platform disrupts Netflix the way Netflix disrupted cable.

Netflix can't predict the future, but it can increase its odds by owning more assets. Owning Warner Bros. gives Netflix:

- Production capability to make content regardless of distribution format (theatrical, streaming, games, VR, etc.)

- IP assets that remain valuable under multiple scenarios

- Talent relationships with the best directors, writers, and producers in the world

- International distribution advantages that help Netflix grow in regions where it's weak

- Margin expansion through vertical integration, which buys time to figure out the future

It's not a perfect strategy, but it's a reasonable hedge against uncertainty.

Paramount's bid is different. Paramount is buying because it's desperate, not because it's strategically confident. That's a red flag. Desperate acquisitions usually fail because desperation clouds judgment.

The International Angle: Why Global Scale Matters

One detail that's often overlooked: Netflix's $83 billion bid makes more sense when you account for international expansion.

Netflix generates roughly 50% of revenue from the US and Canada and 50% from international markets. But international margins are lower because pricing is lower (consumers in India and Brazil won't pay $15/month for Netflix).

Warner Bros. has massive international production and distribution infrastructure. The company owns production facilities on multiple continents. It has relationships with international theaters, distributors, and broadcasters. It produces content in local languages and understands regional tastes.

For Netflix, acquiring Warner Bros. means dramatically improving international competitiveness. Netflix can use Warner Bros.' production facilities and distribution networks to expand in Latin America, Europe, and Asia. That's worth billions in discounted future revenue.

Paramount doesn't have this advantage. The company's international presence is weaker. Even if Paramount acquired Warner Bros., it would struggle to leverage the international assets because Paramount+ hasn't successfully penetrated international markets the way Netflix has.

This is probably a significant factor in why Netflix is more confident about the deal. The company can extract value from Warner Bros. internationally in ways Paramount can't. That justifies higher acquisition price.

Regulatory Hurdles: The Real Wildcard

Both deals face regulatory scrutiny. But the nature of the scrutiny differs.

For Netflix's deal: Antitrust regulators will ask whether combining Netflix (dominant streaming platform) with Warner Bros. (major studio) reduces competition or creates unfair advantages. Netflix's argument: the deal creates a more formidable competitor against Disney and Amazon, which is pro-competitive. The government's concern: Netflix becomes too large and uses its market power to exclude competitors from content.

For Paramount's deal: Antitrust regulators will ask similar questions, but Paramount is the weaker player, so the deal faces different scrutiny. Paramount would argue the deal helps it compete with Netflix. The government might agree, or it might block the deal to prevent unnecessary consolidation.

However, there's a political angle. The Trump administration might be more permissive of consolidation (pro-business stance) or more restrictive (nationalist concerns about tech monopolies). Elon Musk's influence on the administration and his various conflicts with Netflix and other tech companies might affect regulatory treatment.

My bet: Netflix's deal faces regulatory delays and possibly higher conditions for approval, but ultimately closes in modified form (Netflix might divest some assets to satisfy regulators). Paramount's deal faces more skepticism and has a lower probability of approval, though Ellison's political connections might push it through.

The Streaming Wars' Ultimate Winner

Assuming Netflix closes the deal and Paramount doesn't, what does that mean for the streaming wars?

Winner: Netflix. The company expands from 232 million subscribers to potentially 300+ million (if it leverages Warner Bros. content). It improves margins through vertical integration. It dominates prestige content, blockbuster franchises, and international expansion. Within 5 years, Netflix's market cap could approach $400+ billion, making it bigger than Disney by market cap.

Loser: Paramount. Without the deal, Paramount faces slow decline. Paramount+ growth stalls. Cable channels continue losing relevance. The company either finds a buyer at a lower price, remains independent and shrinks, or gets broken apart. Shareholders lose significant value.

Secondary impact: Disney and Amazon. Both companies have invested heavily in streaming and studio assets. Netflix's acquisition of Warner Bros. doesn't directly threaten them (they're not acquiring the same assets), but it does signal that scale and consolidation matter. Both companies will likely accelerate streaming investment and possibly pursue their own acquisitions.

Biggest loser: Traditional theaters. Warner Bros. will shift to faster Netflix release windows (10-14 days of theatrical exclusivity instead of 45 days). That hurts theater chains, especially for mid-budget films that rely on extended theatrical runs. Expect continued theater consolidation and eventual closure of smaller chains.

FAQ

Why does Netflix want to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery for $83 billion?

Netflix is bidding $83 billion for Warner Bros.' production studios to gain vertical integration benefits: controlling content production costs, owning valuable IP franchises (DC Universe, Harry Potter, Dune), accessing international production infrastructure, and expanding margins through in-house production rather than external licensing. The company believes owning the creative assets that generate subscriber value will improve profitability and competitive positioning as streaming matures.

What makes Paramount's $108 billion hostile bid different from Netflix's offer?

Paramount's bid of

Why does owning cable channels matter for these acquisitions when cable TV is declining?

Cable channels were historically valuable because of bundling leverage—cable providers forced consumers to buy 100-channel packages to access premium channels. But bundling power has evaporated as consumers now pick individual services. Paramount wants cable channels assuming it can revive them or repackage them, but Netflix correctly identified that cable channels are now liabilities, not assets. This reveals a fundamental disagreement about the future of media between Netflix (dismissing cable) and Paramount (doubling down on bundling).

How do streaming economics explain these enormous acquisition prices?

Streaming generates lower margins than cable TV because subscription prices max out around

What would happen to consumers if Netflix acquires Warner Bros.?

Consumers would likely see higher Netflix subscription prices (expect $25-30/month premium tiers), faster Netflix release windows for Warner Bros. films (reducing theatrical exclusivity from 45 days to 10-14 days), and more DC Universe and Harry Potter content on Netflix exclusively. The short-term experience improves—more content tailored to Netflix. The long-term experience might worsen as competition consolidates and pricing power increases. Consumers might pay more for fewer service choices.

Why do media consolidation deals usually fail despite optimistic financial projections?

Media consolidation fails because integration complexity is underestimated, synergies don't materialize as predicted, corporate cultures clash, and fixed costs don't scale down proportionally. AOL's merger with Time Warner, AT&T's acquisition of Direc TV, and countless other deals started with confident projections of cost savings and revenue synergies. But creative organizations are harder to integrate than software companies, and media markets are more cyclical. Most consolidation deals destroy shareholder value within 5-10 years as the acquirer realizes the business model doesn't work as expected.

Could AI-generated video undermine the value of these acquisitions?

Possibly, yes. If AI video generation becomes capable enough to produce franchise spinoffs and secondary content at a fraction of traditional production cost within 5 years, then the value of owning expensive production studios and legacy IP decreases. The franchises become more valuable as differentiation against AI-generated content but potentially less valuable if AI can create infinite variations that cannibalize demand for legitimate sequels. This is a wildcard that neither Netflix nor Paramount is publicly discussing but should consider.

What are the regulatory hurdles for these deals to close?

Both deals require approval from the Federal Trade Commission and potentially international regulators. Netflix's deal faces antitrust scrutiny because combining the dominant streaming platform with a major studio might reduce competition. Paramount's deal faces skepticism because it consolidates struggling assets rather than creating clear competitive benefits. Political factors matter: Paramount might have approval advantages due to Ellison's Trump administration connections, while Netflix might face delays due to tech platform skepticism. Approval timelines likely extend 18-24 months.

Is the streaming consolidation trend inevitable, and what does it mean for the industry?

Consolidation appears inevitable because streaming economics force companies to choose between scale (through consolidation) or niche focus (remaining independent). Scale provides bargaining power with distributors, reduces per-unit content costs, and creates synergies. However, consolidation doesn't solve the fundamental problem: streaming margins are permanently lower than cable TV, and subscription saturation is approaching in developed markets. Expect continued consolidation followed by a shakeout in 5-10 years when survivors prove unprofitable and underperforming deals require restructuring. The industry will eventually stabilize with 3-4 dominant platforms plus numerous niche services.

The Unstoppable Consolidation Wave

The Netflix vs. Paramount bidding war isn't the beginning of consolidation. It's the middle. The wave will continue.

Within 5 years, expect Amazon to acquire major assets (possibly Paramount if Ellison's bid fails). Expect Apple to accelerate content spending and consider studio acquisitions. Expect Roku or other distribution platforms to consolidate production assets. Expect private equity to swoop in and acquire distressed media properties at discounts.

The entertainment industry is consolidating not because consolidation is strategically brilliant but because the alternative—remaining independent with declining margins—is worse.

This process will be messy. There will be failed deals, disappointed shareholders, and corporate restructurings. Some consolidation will work (Netflix is positioned well). Most won't (Paramount's bid is probably doomed). But the trend continues because the math is relentless.

The companies that survive will be those that consolidate early, improve margins efficiently, and figure out how to differentiate in an increasingly commoditized attention economy. Whether that's Netflix, Paramount, Disney, Amazon, or someone new remains uncertain. But consolidation is coming regardless.

That's not good news or bad news for the entertainment industry. It's just news—the market working itself out through consolidation, disruption, and eventual stabilization. The consumers, creators, and companies caught in the transition experience plenty of turbulence. But that's how industries transform.

Key Takeaways

- Netflix bid $83 billion for Warner Bros. production studios to improve margins through vertical integration, excluding cable channels it views as liabilities

- Paramount's hostile $108 billion counter-offer for the entire package including CNN and cable reflects desperation to compete with Netflix's 232 million subscribers

- Cable channels are now liabilities, not assets, due to cord-cutting acceleration (26% subscriber losses in 2024) and collapsing advertising revenue

- Streaming margins are permanently lower than cable TV (100+ for cable), making consolidation a survival strategy

- AI-generated video within 3-5 years could fundamentally alter the value of legacy IP, representing an unpriced risk for both deals

- Regulatory approval timelines extend 18-24 months, with political factors favoring Paramount's Ellison but Netflix's bid being more strategically sound

- Media consolidation historically fails: AOL-Time Warner and AT&T-DirecTV destroyed billions in shareholder value, suggesting these deals carry significant execution risk

- The consolidation wave is inevitable as streaming matures and scale becomes essential for survival, but it won't solve the core economic problem of lower subscription margins

Related Articles

- Netflix's $82.7B Warner Bros Deal: The Streaming Wars Heat Up [2025]

- Netflix's $82.7B Warner Bros. Acquisition: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Paramount vs. WBD Netflix Deal: The Hostile Takeover Battle Explained [2025]

- Netflix's $72B Warner Bros. Deal: How All-Cash Strategy Defeats Paramount [2025]

- Streaming in 2026: What Subscribers Should Expect [2025]

![Netflix vs. Paramount: The $108B Streaming War Reshaping Hollywood [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/netflix-vs-paramount-the-108b-streaming-war-reshaping-hollyw/image-1-1769701570242.jpg)