New York's Data Center Moratorium: What the 3-Year Pause Means [2025]

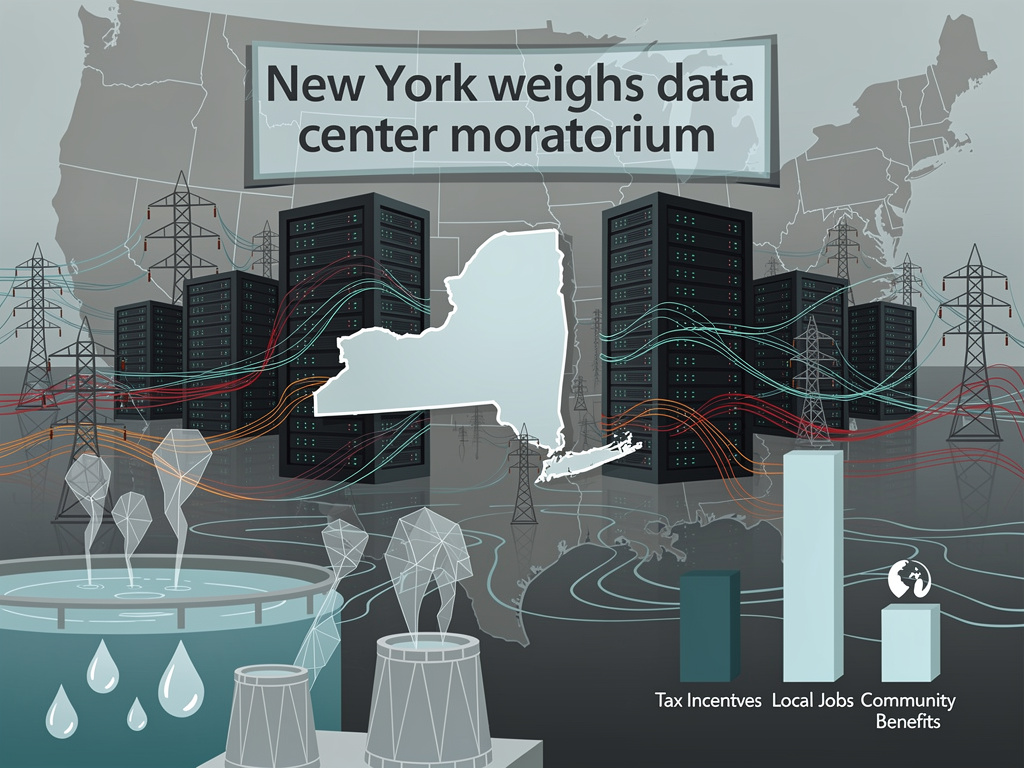

In January 2025, New York State Senators Liz Krueger and Kristen Gonzales introduced legislation that would fundamentally reshape how the state approaches data center development. The proposal, which aims to halt new data center permits for at least three years and ninety days, represents one of the most aggressive regulatory moves against AI infrastructure expansion in the nation. But this isn't just about New York—it's part of a broader wave of state-level pushback against the explosive growth of data centers that's consuming enormous amounts of electricity, water, and generating unforeseen environmental costs.

The timing feels critical. Across the country, data centers are multiplying faster than anyone anticipated. Companies building AI models, training large language models, and hosting cloud services are locked in an infrastructure arms race. Every new AI startup needs compute. Every established tech giant is expanding capacity. The result? States are waking up to find their power grids strained, their water supplies stressed, and their electricity rates climbing. New York's bill is essentially saying: "Hold on. Let's figure out what this actually costs before we allow more."

This is genuinely consequential. If passed, New York's moratorium would prevent companies from breaking ground on new data centers for three years while state agencies conduct comprehensive impact assessments. The bill isn't anti-technology—it's pro-planning. It requires the Department of Environmental Conservation and Public Service Commission to examine water usage, electricity demand, gas consumption, and the impact on utility rates. They'd also need to recommend updated regulations to minimize environmental impacts and protect consumers.

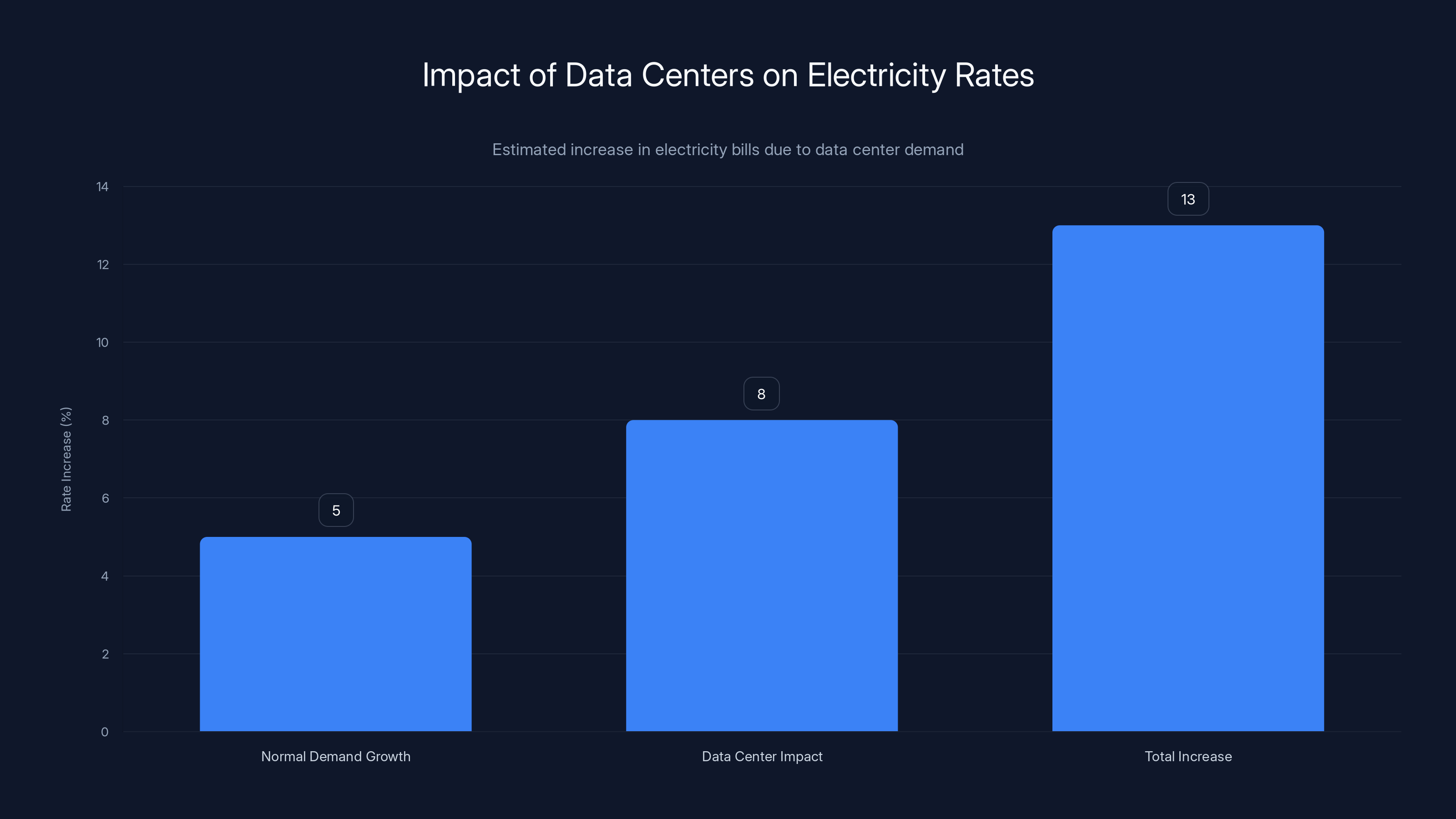

What makes this fascinating is that New York isn't alone. Georgia, Maryland, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Virginia have all introduced similar bills in recent months. This suggests something bigger is happening: states are realizing that unfettered data center growth has real costs that nobody's been paying attention to. One statistic from the bill itself should alarm anyone paying attention to infrastructure: household electricity rates nationally increased 13 percent in 2025, largely driven by data center development.

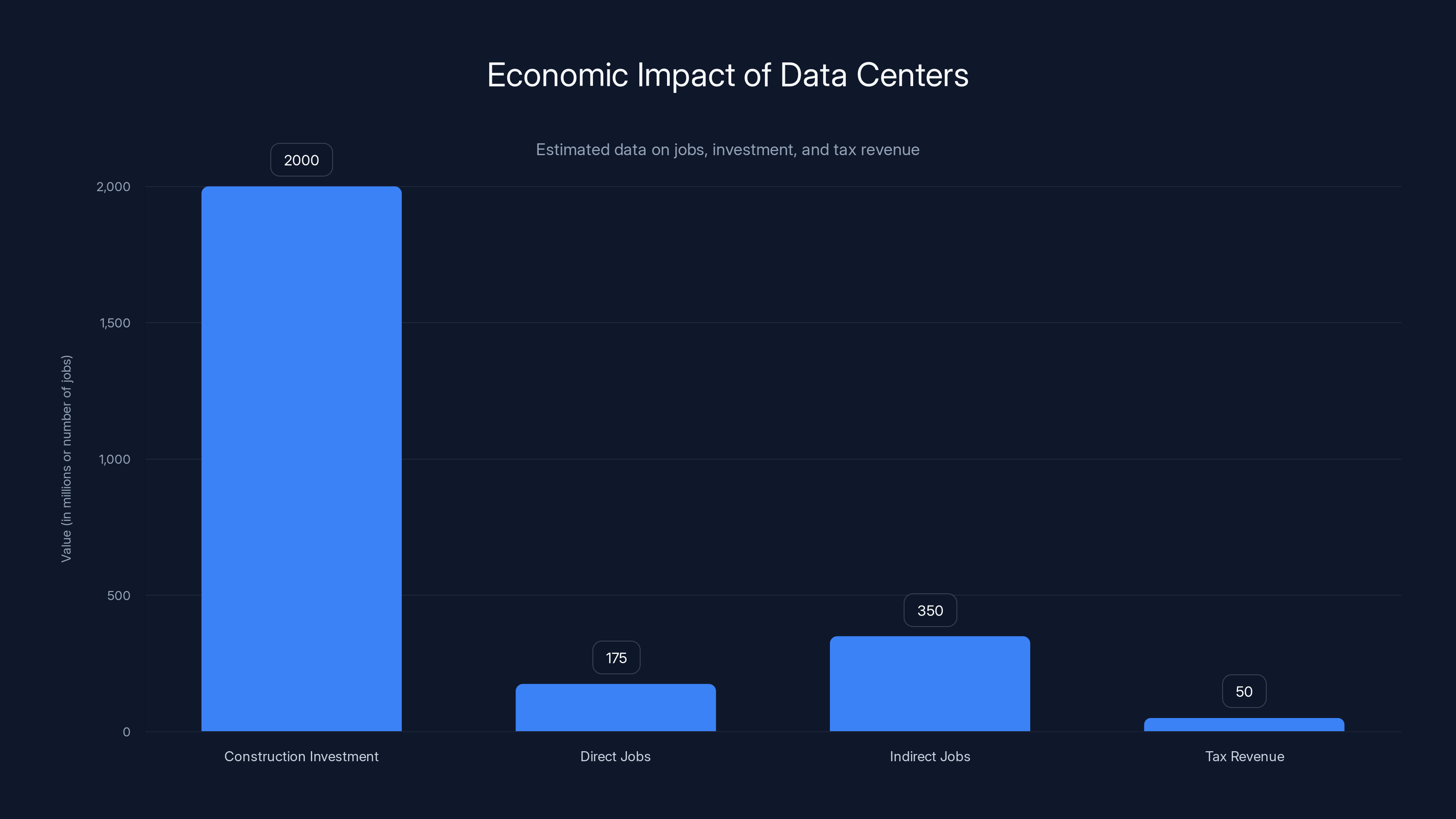

But here's the complexity. Data centers also represent massive economic opportunity. They create jobs, generate tax revenue, and are essential infrastructure for the modern internet. Stopping them completely would be short-sighted. The question is whether New York's measured approach—a pause for study rather than an outright ban—offers the right balance. This article explores what the bill actually does, why it matters, what it means for the AI industry, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- The Bill: New York lawmakers introduced legislation halting new data center permits for 3 years and 90 days pending environmental impact studies

- The Reason: Data center growth is driving electricity rate increases (13% nationally in 2025) and straining resources

- The Scope: Requires assessments of water, electricity, and gas usage impacts on consumer rates

- The Precedent: Six states have now introduced similar moratorium bills, showing coordinated state-level concern

- The Implication: Could significantly slow AI infrastructure expansion if other major states follow suit

Data centers contribute significantly to electricity rate increases, estimated at 8% of the total 13% rise projected for 2025. Estimated data.

Understanding the Legislation: What Exactly Does the Bill Do?

The bill introduced by Senators Krueger and Gonzales is elegantly simple in concept but complex in execution. At its core, it imposes a temporary halt on permit issuance for new data center construction. But it's much more than a simple "no." The legislation is structured as a regulatory study period—a time-out designed to gather crucial information that's currently missing from policy decisions.

Here's what the bill actually requires. First, it freezes new data center permits for at least three years and ninety days. This isn't a permanent ban. It's specifically a pause. The distinction matters because it frames this as a deliberate policy decision to slow down and assess, not as ideological opposition to data centers themselves. During this period, two state agencies are required to conduct comprehensive studies.

The Department of Environmental Conservation bears responsibility for examining the environmental footprint of existing data centers and projecting the impacts of continued growth. They're tasked with analyzing water consumption patterns, which is critical in regions where data centers compete with agriculture and municipal water supplies for limited resources. They also must study electricity demand and how data center growth affects grid stability and overall power consumption. Gas usage comes into the equation too, since many data centers use natural gas for backup generators and climate control.

The Public Service Commission, meanwhile, focuses specifically on consumer impact. They must analyze how data center development affects utility rates for ordinary New Yorkers. This is the angle that often gets overlooked in debates about infrastructure—the person paying the electric bill. When data centers drive up demand for electricity, everyone's rates go up. The commission would determine whether current regulatory frameworks adequately protect consumers from these cost increases.

Beyond the studies themselves, the bill requires both agencies to develop new regulations if they determine current rules are insufficient. This is forward-looking governance. Rather than waiting for problems to emerge and then reacting, the legislation creates space for proactive regulatory development. The agencies can recommend order changes that would minimize data center impacts on both the environment and consumer costs.

What's notable about this approach is that it doesn't preclude data center development entirely—it just makes it deliberate and informed. Once the study period ends, permits could resume, but presumably under updated regulatory frameworks that account for the impacts identified during the pause.

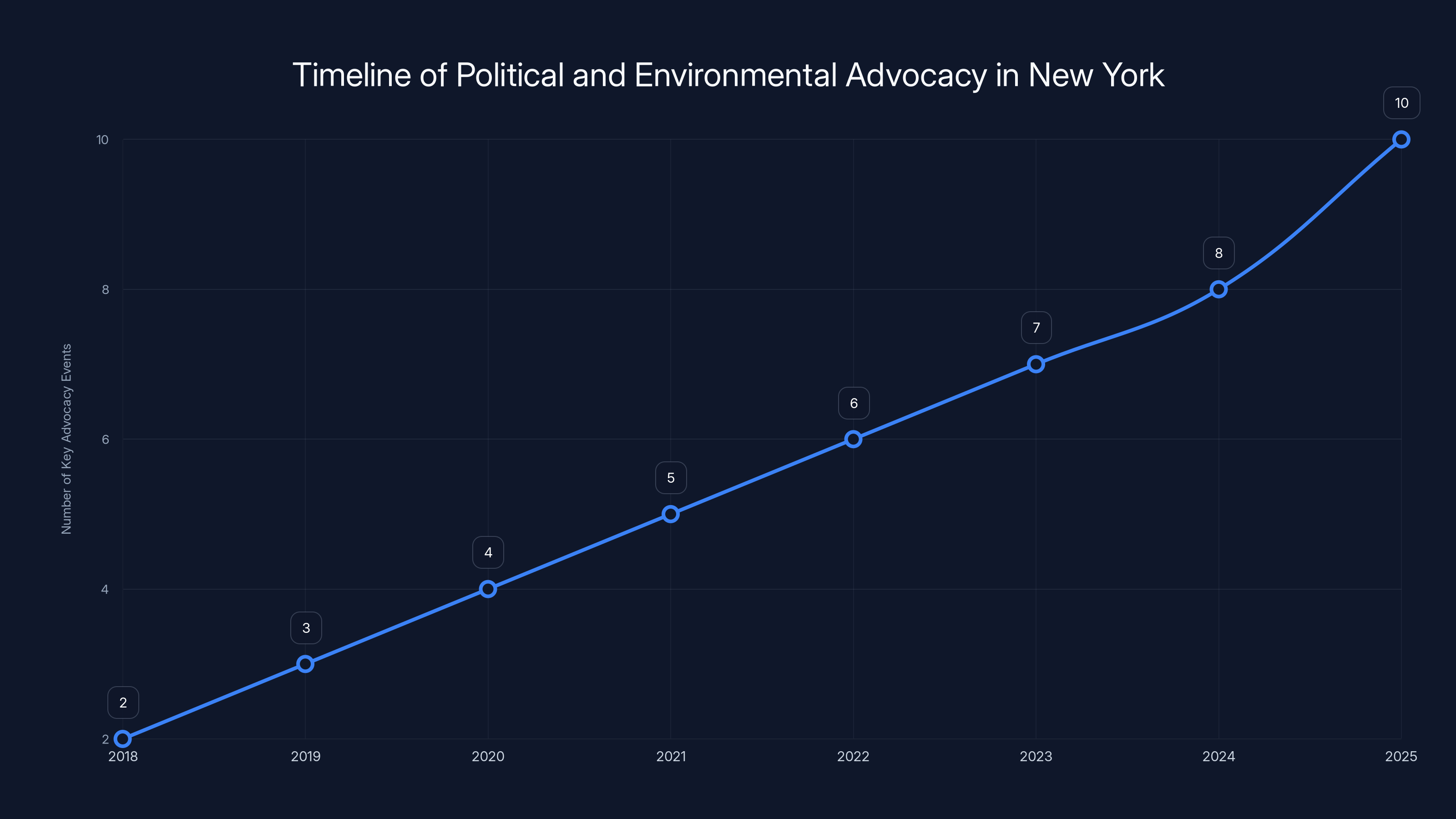

The timeline shows a steady increase in political and environmental advocacy events in New York, culminating in the 2025 moratorium proposal. Estimated data based on narrative context.

The Environmental Case: Why Water and Power Matter

Data centers consume staggering amounts of resources, and the environmental impact extends far beyond the physical footprint of the buildings themselves. Understanding this requires getting specific about the actual numbers, because the scale is genuinely difficult to comprehend.

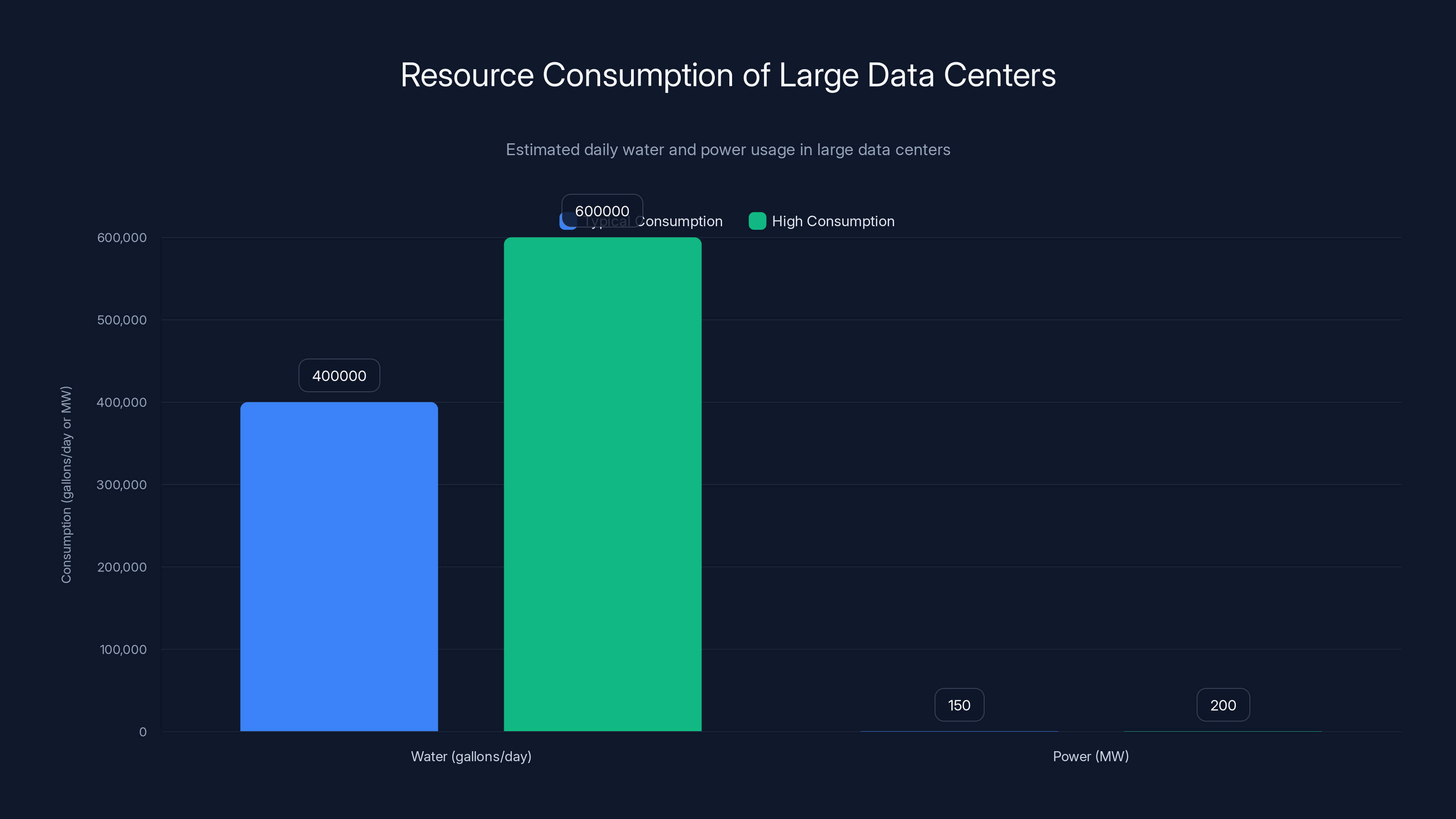

Water consumption is perhaps the most visceral concern. Modern data centers are incredibly thirsty operations. A typical large data center can consume between 300,000 and 500,000 gallons of water per day, depending on cooling methods and climate. Some facilities use even more. This water serves two purposes: evaporative cooling systems and cooling tower makeup water. In hot climates or during summer months, this consumption spikes dramatically.

Consider the implications for a water-stressed region. The American Southwest faces persistent drought conditions. If you're Arizona or parts of Nevada, building data centers that guzzle millions of gallons daily while also servicing a growing human population creates genuine resource conflict. But the issue extends beyond purely arid regions. Even in temperate climates like upstate New York, data centers can stress local water systems, particularly if multiple facilities cluster in the same region.

Electricity consumption is equally significant. A single large data center can consume 100 to 200 megawatts of power continuously—equivalent to powering 75,000 to 150,000 homes. When you have multiple data centers operating in the same power grid region, you're essentially adding a small city's worth of electrical demand. This doesn't just stress the grid; it affects everyone connected to that grid.

The electricity impact manifests in two ways. First, there's immediate grid strain. Power plants must generate more electricity, transmission lines must carry higher loads, and infrastructure that wasn't designed for this demand profile gets taxed. Engineers call this "peak demand management," and it's genuinely complicated. Second, there's the rate impact. When demand increases faster than supply, electricity prices go up. The bill cites data showing that national household electricity rates increased 13 percent in 2025, with data center development identified as a major driver.

Climate control represents another environmental consideration. Data centers generate enormous amounts of heat. Servers running at high utilization produce heat equivalent to running dozens of ovens simultaneously in the same building. Removing this heat requires sophisticated cooling infrastructure—cooling towers, water systems, and often significant natural gas usage for backup systems. The energy required for cooling can represent 30 to 50 percent of a data center's total power consumption, depending on design and location.

There's also the grid resilience question. Electricity grids are designed with capacity margins for safety. When data center growth consumes that margin faster than grid infrastructure can expand, you create vulnerability. A particularly hot day, unexpected power plant maintenance, or other disruptions that the grid would normally handle smoothly suddenly become more problematic. New York's power grid, particularly upstate, has already experienced strain during peak demand periods.

The Economic Argument: Jobs, Taxes, and Infrastructure Investment

Before discussing the counterarguments to the moratorium, it's essential to understand why data centers are so attractive to states and communities in the first place. The economic case for data center development isn't some corporate fiction—it's real, and ignoring it would be intellectually dishonest.

Data center construction projects represent massive capital investments. A hyperscale facility can cost

Once operational, data centers create permanent jobs. Not just the highly paid software engineers—though those positions exist too—but also facility managers, technicians, security personnel, administrative staff, and maintenance workers. A large data center typically employs between 50 and 300 people directly, with additional indirect employment through vendors and service providers. These are generally well-paying jobs with benefits, not minimum-wage positions.

Tax revenue represents another significant draw. States and municipalities negotiate tax incentive packages with data center operators, but even with substantial breaks, the ongoing property taxes, sales taxes on equipment, and corporate taxes add meaningful revenue to local budgets. For rural counties or small cities, this can represent a meaningful percentage of total tax revenue.

Beyond the direct economic impacts, data centers serve a crucial infrastructure function. They're essential to modern digital life. Cloud services that run enterprise software, AI training facilities that support next-generation applications, and content delivery networks that make streaming services possible all depend on data center infrastructure. Without adequate capacity, the entire digital economy suffers.

The talent and innovation angle matters too. Companies building cutting-edge technology clusters locate near data centers and computing resources. AWS regions attract startups and innovation hubs. Microsoft's data center investments support Azure ecosystem growth. Google's facilities enable their AI research to translate into products. For states and regions seeking to attract technology talent and industry, data center infrastructure serves as a magnet.

This is why states compete fiercely for data center projects. When a developer considers where to build a $2 billion facility, states offer tax breaks, expedited permitting, and utility rate concessions. It's effectively an economic development arms race. If New York imposes a three-year moratorium while neighboring states welcome development, those projects simply relocate. The jobs, investment, and tax revenue move to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, or Massachusetts instead.

Data centers significantly boost local economies through large capital investments, job creation, and tax revenues. Estimated data reflects typical impacts.

The AI Acceleration Problem: Why This Matters Right Now

The moratorium's timing is not coincidental. It arrives precisely when AI infrastructure demand is accelerating exponentially. Understanding this context is crucial for appreciating why regulators suddenly feel urgent about data center growth.

Training large language models requires staggering computational resources. Open AI's GPT-4 training consumed estimated 1,300 peta FLOPS-days of computing—roughly equivalent to running a trillion calculations per second for days on end. Doing this requires data centers. Not just any data centers, but specialized facilities with advanced cooling, high-reliability power, and cutting-edge GPU infrastructure. The energy consumption for such training runs can reach tens of megawatts for weeks or months.

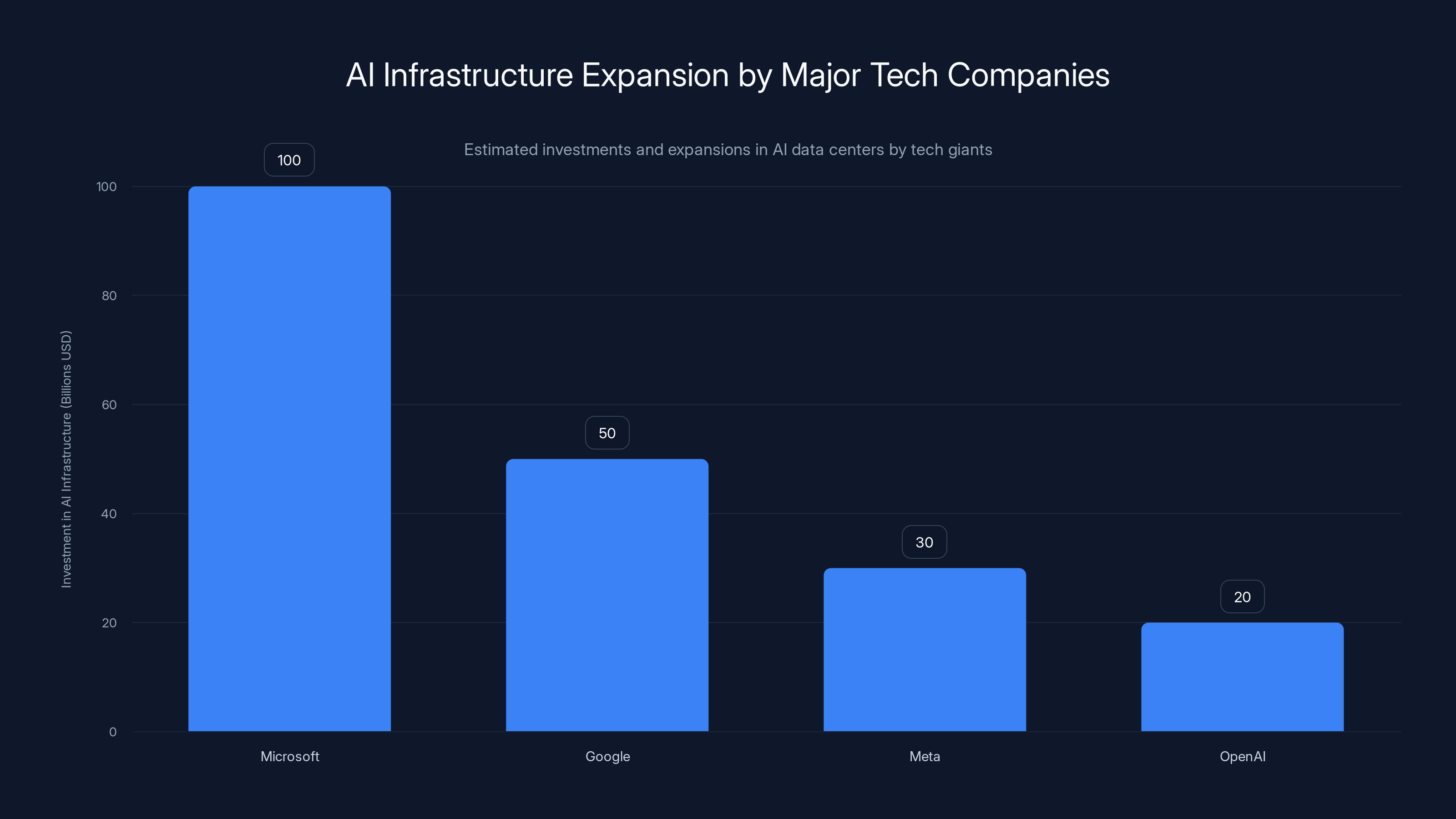

Meta, Google, Microsoft, and other major cloud companies are all expanding data center capacity specifically to support AI workloads. Microsoft announced plans to invest hundreds of billions in AI infrastructure. Google is building new data centers specifically designed for AI. Meta is constructing next-generation facilities to support their AI research. These aren't marginal increases—they represent fundamental expansion of computing infrastructure.

The problem compounds because AI isn't just one-time training. Once models are deployed, they require ongoing inference compute. Every Chat GPT response, every Claude analysis, every Gemini query runs on data center infrastructure. Multiply that across millions of users, and you're talking about steady-state power consumption that grows daily.

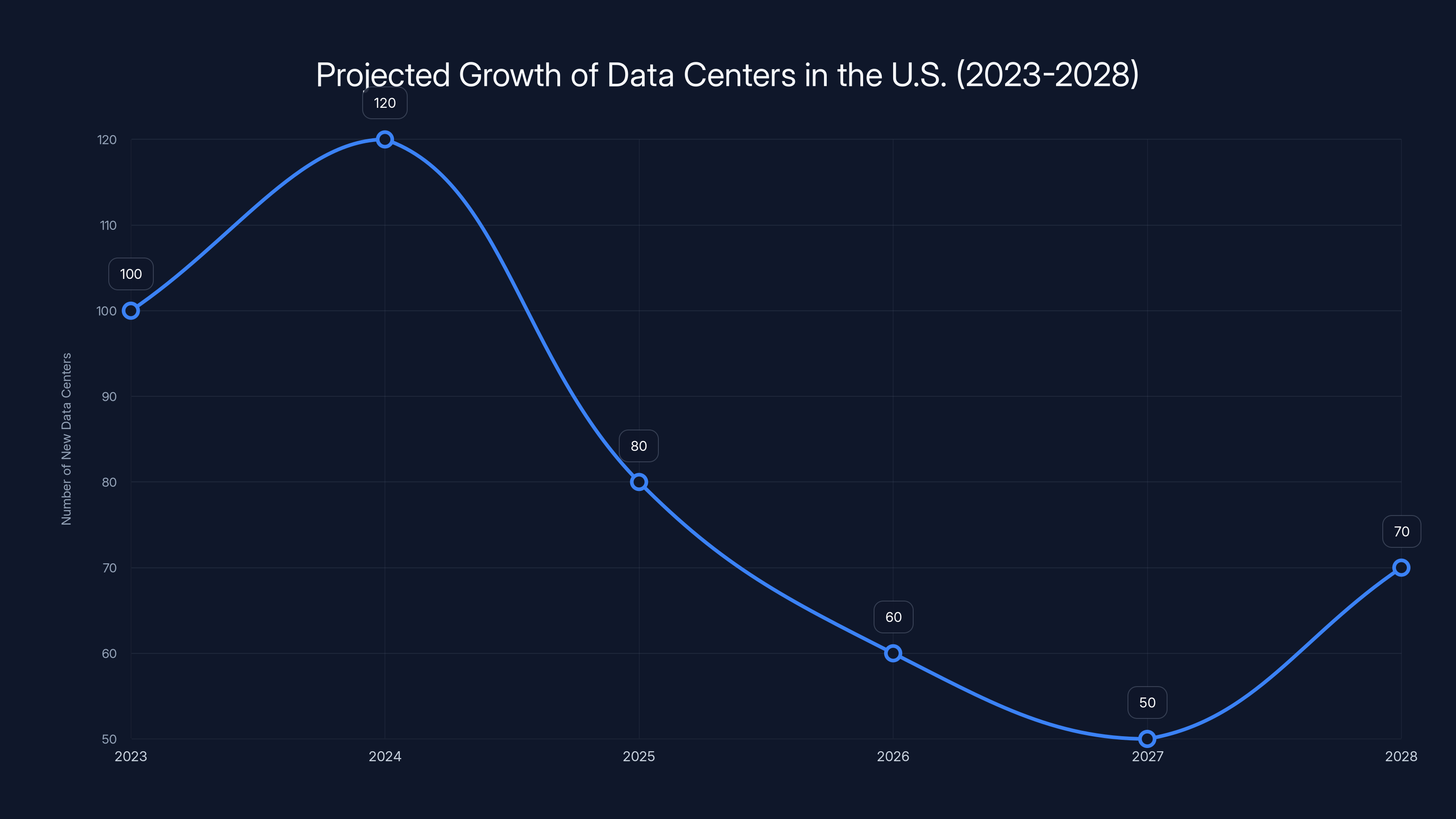

Regulators recognized this acceleration and realized that without intervention, data center development would continue accelerating on its current trajectory. A three-year pause creates a window to assess impacts and adjust regulations before the next wave of AI infrastructure development begins.

There's also a fairness question embedded here. Existing electricity customers—residents and small businesses—have already experienced rate increases due to data center growth. Without regulatory intervention, these increases would compound. The moratorium essentially says: "Before we authorize more of this, let's understand the full cost and ensure that growth doesn't unfairly burden ratepayers."

The National Movement: Six States, One Concern

New York isn't unique in this concern. By early 2025, six states had introduced similar moratorium or regulatory bills targeting data center development. Understanding this broader movement reveals that this isn't a New York-specific issue—it's a coordinated national response to perceived infrastructure strain.

Georgia introduced its own moratorium bill around the same time. Given Georgia's significant data center presence, including Meta's major facility in Newton County, this represents a dramatic policy shift. Maryland followed with legislation addressing data center energy consumption. Oklahoma, typically pro-development, introduced regulatory bills. Vermont, despite its much smaller scale, joined the movement. Virginia, another state with substantial data center presence, began examining regulatory frameworks.

What's significant about this coordinated action is that it suggests information-sharing among state legislators. When multiple states independently propose similar legislation within weeks of each other, it indicates that the concern about data center impacts has reached critical mass among state policymakers. Legislative research organizations, environmental groups, and industry observers likely facilitated this information transfer.

The specific language across these bills shows coordination too. Multiple states adopted similar frameworks: temporary moratoriums (rather than permanent bans), requirements for comprehensive impact studies, and provisions for updated regulations. This suggests that a model is emerging—a regulatory approach that states are adopting and adapting to their specific contexts.

What's particularly interesting is which states didn't introduce moratorium bills but might still be vulnerable to them. States like Texas, which host enormous data center clusters, haven't yet proposed moratoriums, but that could change if environmental concerns intensify or if electricity costs become politically salient. California, despite its technology sector prominence, hasn't introduced such bills, potentially because it already has more stringent energy regulations.

The regional pattern matters too. Northeastern states (New York, Massachusetts, Vermont) appear more aligned on this issue, suggesting that regional power grids and environmental constituencies might coordinate advocacy. Meanwhile, Southern and Mountain states show more variation, reflecting different political contexts and water availability concerns.

If the New York moratorium passes and is implemented successfully, other states may follow more aggressively. Conversely, if it imposes significant economic harm without meaningful environmental benefit, other states might abandon their own proposals. The next two years will essentially determine whether this becomes a national trend or remains a regional regulatory experiment.

Large data centers typically consume 300,000-500,000 gallons of water and 100-200 MW of power daily. Estimated data highlights potential resource strain.

Environmental Impact Assessment: What Gets Studied?

The bill specifies that environmental impact assessments should examine multiple dimensions of data center operations. Understanding what agencies are supposed to evaluate helps clarify what current regulations miss.

Water impact assessments begin with current consumption patterns. The Department of Environmental Conservation would document how much water existing data centers consume, broken down by region and facility type. They'd analyze water sources—are these facilities drawing from aquifers, rivers, reservoirs, or municipal systems? What happens during drought conditions? Do facilities have contingency plans for water restrictions?

The assessment would project future water demand based on current growth trajectories. If data center growth continues at current rates, how much additional water consumption should regulators expect by 2030? What would that mean for regional water availability? In agricultural regions, this could translate to reduced water availability for farming. In urban areas, it might impact municipal water supplies or require competing water demand management.

Wastewater disposal also falls under environmental assessment. Data center cooling systems generate significant wastewater. Where does this water go? Does it strain municipal treatment capacity? Could thermal pollution impact local waterways? These questions rarely get addressed in permitting processes currently, but the bill requires them.

Electricity impact assessment focuses on both supply and demand. How much power do existing data centers consume? What does this represent as a percentage of regional grid capacity? If current development continues, when will the grid reach capacity constraints? What infrastructure upgrades would be required? Who pays for those upgrades—the data center operators or ratepayers generally?

The assessment explicitly requires analysis of consumer impact. How have electricity rates changed in regions with substantial data center development? Is there a measurable correlation? Do rate increases fall disproportionately on certain customer segments? Are small businesses or low-income households particularly burdened by increases driven by data center demand?

Natural gas consumption comes into focus because data centers use natural gas for backup generators and sometimes for direct heating or cooling. The assessment examines whether data center growth strains regional natural gas supply or infrastructure. Do facilities compete with residential heating for limited gas resources during winter months?

Emissions considerations extend the analysis. While data centers themselves produce emissions primarily through energy consumption, the assessment should quantify this. If electricity comes from natural gas plants, what are the associated greenhouse gas emissions? If it comes from renewable sources, are new renewable installations being built specifically to serve data center demand, or are existing renewable capacity being diverted from other users?

Biodiversity and land use impacts round out the environmental assessment. Data centers require significant land. What natural habitats are lost? Could facilities be built on already-developed land instead of greenfields? Are there cumulative impacts from multiple facilities clustering in the same region?

The Rate Impact Analysis: Consumer Cost Reality

The bill's focus on consumer impacts through utility rate analysis addresses something that often gets overlooked in data center discussions: who actually pays the cost? The answer, broadly, is everyone paying electricity bills.

When data centers increase demand on a regional power grid, electricity prices rise. This isn't necessarily because of data center operators paying higher rates—though that happens too. Rather, higher overall demand increases the wholesale price that all generation capacity commands. If a power grid that was operating at 60% capacity suddenly jumps to 80% capacity due to new data center demand, the marginal cost of electricity increases for everyone.

Economists have documented this phenomenon in detail. Regions with substantial data center growth show measurable electricity rate increases beyond what would occur from normal demand growth. The bill cites a Bloomberg analysis showing that national electricity rate increases of 13 percent in 2025 were "largely driven by" data center development. While "largely" is somewhat ambiguous, it indicates that data centers accounted for multiple percentage points of that increase.

Breaking this down: if the average household electricity bill is

The situation is complicated because benefits from data center operations also flow to consumers. Lower cloud computing costs, more reliable internet services, and improved digital services partly result from data center infrastructure investments. So the complete cost-benefit analysis isn't simply "data centers are bad because they raise rates." Rather, it's "data centers have benefits AND costs, and we should ensure that costs are distributed fairly rather than concentrated on electricity ratepayers."

The Public Service Commission analysis would ideally quantify this. How much cost do consumers bear for data center infrastructure? How much value do they receive through lower IT service costs? Is the distribution equitable, or do some customer segments bear disproportionate cost?

Regulatory solutions might include special rate structures for data centers that more accurately reflect their infrastructure impacts. Rather than all consumers paying for grid expansion that serves data center demand, rate structures could charge data centers more explicitly for the infrastructure they necessitate. This wouldn't eliminate rate increases, but it could prevent them from being distributed across all electricity consumers.

Alternatively, data center operators could be required to invest in renewable generation or demand-response infrastructure. If a new data center will increase regional electricity demand by 50 megawatts, requiring the operator to develop 50 megawatts of new renewable capacity keeps overall grid demand in balance.

Major tech companies are investing heavily in AI infrastructure, with Microsoft leading at an estimated $100 billion. Estimated data.

Precedents and Regulatory Models: What Other States Have Done

While New York's moratorium approach is relatively novel at the state level, precedent exists from other contexts. Examining how other jurisdictions have addressed rapid infrastructure growth provides insight into how moratoriums might function and what challenges might emerge.

California's approach to data center regulation differs fundamentally—rather than implementing a development pause, California has focused on energy efficiency standards. The state requires data centers to meet specific power usage effectiveness (PUE) ratios, essentially mandating that operators minimize energy waste. This approach encourages continued development while improving environmental outcomes. The downside is that efficiency standards alone don't prevent the overall consumption increase that comes with more facilities.

The European Union's approach combines multiple regulatory tools: efficiency standards like California's, but also requirements for waste heat recovery. EU regulations increasingly require data centers to capture waste heat for district heating systems or other productive uses. This transforms data centers from pure energy consumers into potential energy resources. The disadvantage is that this requires more complex infrastructure and planning.

Some cities have implemented development moratoriums on other infrastructure types. Google's expansion in San Francisco faced permitting challenges, partly reflecting neighborhood concerns about growth. Cloud computing facilities proposed in dense urban areas sometimes encounter local opposition that effectively creates de facto moratoriums. New York's approach differs by creating an explicit, time-limited pause rather than letting opposition create indefinite uncertainty.

Singapore, despite being an extremely space-constrained city-state, has permitted significant data center development by implementing strict environmental standards and requiring operators to prioritize efficiency. This suggests that development and environmental protection aren't necessarily incompatible—the question is whether regulations effectively enforce environmental responsibility.

The precautionary principle underlying New York's moratorium appears in environmental policy more broadly. When technologies or activities pose uncertain but potentially significant risks, precaution suggests pausing until impacts are better understood. This approach motivated restrictions on other activities—CFCs and ozone layer damage, industrial discharge and water quality, coal burning and air quality—before impacts became catastrophic.

Applied to data centers, the precautionary principle suggests: we don't fully understand the cumulative environmental and economic impacts of massive data center growth; therefore, we should pause and study before authorizing more. This is philosophically defensible, though it does prioritize caution over economic growth.

Industry Response: Tech Companies and Data Center Operators React

The proposed moratorium has generated predictable industry response. Tech companies and data center operators argue that the pause will harm innovation, slow AI progress, and damage economic opportunity. Understanding their arguments provides necessary counterbalance to the environmental and consumer protection rationale.

Major cloud providers argue that AI infrastructure development is genuinely important for competitive positioning and that any pause advantages competitors in states without moratoriums. If Microsoft can build new capacity in Pennsylvania while New York restricts development, Microsoft's competitors lose out. This is genuinely true—regulatory arbitrage is real. Companies will locate infrastructure where permitting is easiest and regulations least burdensome.

Industry advocates point out that their companies are already investing in renewable energy and efficiency. Microsoft has committed to making their data centers net-positive for water usage, meaning they'll return more water to local systems than they consume. Google regularly publishes energy efficiency metrics and invests heavily in renewable energy. From their perspective, restrictions feel unfair because they've already demonstrated responsibility beyond regulatory requirements.

There's also an innovation argument. AI is developing rapidly, and computational infrastructure is necessary for this development. A three-year pause might not seem long, but in AI timescales, three years represents enormous opportunity cost. New models, new techniques, new applications might not develop on the same timeline if infrastructure constraints appear. Countries investing in AI infrastructure without moratoriums might advance faster.

Data center construction and equipment companies argue that moratoriums hurt workers and suppliers. The engineers, construction workers, equipment manufacturers, and service providers who depend on data center projects face uncertain future demand. Skilled workers might relocate to other states, creating brain drain.

Yet the industry perspective misses something important: environmental and consumer protections also serve legitimate interests. If data center growth genuinely strains water systems or raises electricity costs disproportionately, that's a real problem that shouldn't simply be ignored in pursuit of economic growth. The question isn't whether data center growth matters—it does. The question is whether the benefits justify the costs and whether those costs are distributed fairly.

Some industry voices acknowledge this. Progressive data center companies have indicated support for more robust environmental standards, at least rhetorically. The argument becomes: let's implement strong environmental regulations and proceed with development, rather than imposing a moratorium. This is a reasonable compromise position, though whether regulators and environmental advocates find it sufficient remains unclear.

The projected number of new data centers in the U.S. shows a decline from 2025 to 2027 due to moratoriums like New York's, with a slight recovery expected by 2028. Estimated data.

Political Considerations: Why Now? Why New York?

Understanding the political context for the moratorium reveals why this proposal emerged in January 2025 and why New York specifically became the flashpoint for this regulatory movement.

Senator Liz Krueger has a long history of environmental advocacy and regulation of tech companies. Her previous work includes pushing back on Amazon's HQ2 expansion in Long Island City—a development that was proposed with substantial tax incentives but faced local opposition. Krueger's consistent theme involves scrutinizing whether big tech expansion actually benefits local communities or primarily enriches corporations at taxpayer expense. The data center moratorium reflects this analytical framework applied to infrastructure development.

Senator Kristen Gonzales represents a district in the Bronx that includes constituencies concerned about environmental justice. New York's environmental movement, particularly in communities of color, has consistently raised concerns about unequal distribution of environmental burdens. If data centers drive electricity cost increases, low-income communities bear disproportionate burden because energy represents a larger percentage of household expenses. From a progressive environmental justice perspective, the moratorium protects vulnerable populations from bearing the costs of infrastructure serving wealthy tech companies.

New York specifically became the focus partly because of upstream electricity generation in the state. Data center growth in upstate New York impacts power generation in that region, affecting residents and regional power availability. The state legislature has also become increasingly focused on climate and environmental issues, particularly under Governor Kathy Hochul's administration, which committed to a transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy.

Timing reflects growing awareness of data center impacts. Media coverage throughout 2024 highlighted electricity rate increases, water consumption concerns, and environmental impacts of data center expansion. By January 2025, these concerns had penetrated public consciousness enough that introducing moratorium legislation appeared politically viable.

There's also precedent in New York for technology regulation. The state has historically been willing to regulate tech companies more aggressively than many states—from early internet regulation to data privacy measures. This regulatory inclination makes data center moratorium legislation fit within established political patterns.

The political calculation appears to be that the benefits of demonstrating environmental responsibility and protecting ratepayers outweigh the costs of potentially losing some data center development to other states. Whether this calculation is correct will become apparent as the moratorium progresses.

Likely Amendments and Political Viability: Will This Actually Pass?

The bill as introduced represents an opening position in legislative negotiation, not necessarily its final form. Predicting the likelihood of passage requires understanding potential amendments and political dynamics.

Developers and industry groups will likely push for exemptions or shortened timeframes. Language might be added exempting data centers below certain size thresholds, allowing projects already in permitting pipelines to proceed, or shortening the moratorium to two years rather than three. These amendments would serve as compromise positions—maintaining the principle of a pause while reducing economic impact.

Environmental groups will likely push in the opposite direction, seeking permanence or indefinite extension, stronger environmental study requirements, or explicit language preventing permit issuance even if impact studies complete before the three-year deadline. They might also seek binding requirements that updated regulations actually restrict development, rather than simply allowing regulators to recommend restrictions without enforcement.

The Public Service Commission's role introduces another variable. If the commission determines that data center regulation requires substantial rate increases for operators to protect consumers, that creates political pressure to water down requirements. Conversely, if studies show minimal options for mitigating rate impacts, political pressure might shift toward supporting the moratorium to protect ratepayers.

Geographic divisions matter politically. Upstate New York, where some data center development and power generation occur, might oppose moratoriums differently than downstate. Upstate communities might welcome data center jobs and tax revenue. Downstate consumers might care more about electricity rate impacts. These regional tensions will play out during legislative debate.

Industry lobbying will be substantial. Tech companies, data center operators, and equipment manufacturers have significant political resources. Their advocacy will emphasize economic costs of the moratorium and argue for alternative regulatory approaches. This advocacy often influences legislative outcomes, though it doesn't determine them—it creates political pressure that legislators must navigate.

The moratorium's fate also depends on whether it becomes a partisan issue or remains relatively bipartisan. Currently, environmental concerns about data center development cross party lines. Republicans in some states have introduced similar bills, suggesting this isn't purely a progressive issue. If the moratorium remains bipartisan, passage becomes more likely. If it becomes labeled as anti-business or anti-growth, Republican opposition might intensify.

Comparable precedents suggest moderate likelihood of passage with amendments. When New York has pursued technology regulation previously—data privacy, algorithmic transparency, AI regulations—bills have usually advanced but often with modifications that represent compromises between environmental and business concerns.

Potential Loopholes and Unintended Consequences: The Regulatory Challenges

Even if the moratorium passes, implementation will reveal challenges and potential loopholes that legislators didn't anticipate. Understanding these likely complications prepares observers for the next regulatory battles.

The definition of "data center" becomes crucial. The bill presumably applies to commercial data center facilities operated by cloud providers and colocation companies. But what about edge computing facilities, smaller distributed data centers, or data centers operated by enterprises for their own use? If the definition is narrow, companies could circumvent the moratorium by building multiple smaller facilities instead of one large one. If the definition is broad, it might inadvertently capture research computing facilities or other infrastructure that legislators didn't intend to restrict.

Permit-in-pipeline issues will likely emerge. Companies with data center projects already in regulatory review when the moratorium becomes effective will argue that their projects should be exempt. The bill will probably require language addressing this, but what constitutes sufficient progress through permitting? If a company submits preliminary plans, do they get grandfather protection? The bill's implementation will generate disputes about what exactly qualifies.

Interstate competition problems will inevitably appear. If New York restricts development while Pennsylvania doesn't, companies simply build in Pennsylvania and serve New York customers from outside the state. Economists call this "regulatory leakage." The moratorium shifts environmental and infrastructure burdens elsewhere rather than reducing overall development. This is particularly problematic if Pennsylvania has weaker environmental standards, meaning the net environmental effect could be negative.

The study period's effectiveness depends on researcher competence and political will. If the Department of Environmental Conservation and Public Service Commission produce studies showing minimal impacts, they might recommend allowing development to resume largely unrestricted. This would effectively render the moratorium a minor delay rather than meaningful environmental protection. Alternatively, if studies conclude that significant restrictions are necessary, implementing them will generate political backlash from industry.

Timing creates another complication. The bill requires studies to complete during the moratorium period, but comprehensive studies of complex infrastructure impacts require significant research. Three years might not be adequate time for definitive answers about long-term environmental impacts. The pause might conclude with conclusions remaining uncertain, forcing policy decisions without complete information—which actually undermines the moratorium's rationale.

Regulatory capture represents a more cynical risk. If industries being regulated have sufficient political influence, they might shape the study process and recommendations to minimize restrictions. Environmental groups worry that commissioners appointed by industry-friendly politicians will conduct studies designed to justify continued development rather than genuinely investigating impacts.

International Implications: Global Data Center Development and Competition

While the moratorium is a New York state issue, its implications ripple globally. Understanding international dimensions helps contextualize what the regulation might mean for the global data center industry and infrastructure competition.

Europe faces similar data center pressures and has responded with different regulatory approaches. The EU's Digital Infrastructure Strategy emphasizes developing sovereign data center capacity within Europe rather than depending on American cloud providers. Simultaneously, European environmental regulations (CJEU standards, water framework directives) impose stricter controls than most American states. The result is that data center development in Europe is more restricted and more expensive than in America, which actually advantages American companies globally.

If America adopts more restrictive data center regulations through state-level moratoriums that spread nationally, American data center operators lose their regulatory advantage relative to European competitors. This is a subtle but real implication: New York's moratorium might actually help European tech companies compete against American cloud providers by leveling the regulatory playing field.

China has taken a completely different approach, implementing nationwide planning for data center development. China designates specific regions for data center concentration and requires operators to use renewable energy in certain provinces. This centralized planning approach permits rapid scaling while theoretically preventing uncontrolled environmental impact. Whether this actually protects the environment or simply displaces impacts to regions with less political voice remains debatable.

India is rapidly becoming a data center hub, partly because regulatory oversight is lighter than in America or Europe. Companies building large facilities in India face less environmental scrutiny and lower costs. If America restricts data center development, Indian facilities become relatively more attractive for infrastructure investment, potentially shifting technological development away from America.

The global implication is subtle: if New York's moratorium represents the beginning of more restrictive American data center regulation, it could have geopolitical consequences. Data center location influences where technology innovation happens, where talent clusters, and where value creation occurs. Driving data center development to other countries might ultimately disadvantage American technology competitiveness.

This doesn't necessarily argue against the moratorium—it simply acknowledges that environmental and social responsibility have costs that extend beyond direct economic impacts. The question becomes whether policymakers accept these global competitive costs in exchange for environmental and consumer protections.

Long-term Regulatory Trends: Where Might This Lead?

The moratorium represents part of a broader trajectory in technology regulation. Understanding this longer trend provides perspective on what the moratorium might become and how regulation of data centers might evolve.

Technology regulation has generally moved from minimal intervention toward increasingly active management. The internet was largely unregulated through the 1990s and early 2000s. Gradually, regulations emerged around data privacy (GDPR, CCPA), algorithmic transparency, AI safety, and environmental impacts. This trajectory suggests that data center regulation will likely intensify, not ease.

The pattern is relatively predictable. First, an activity or technology expands rapidly with minimal oversight. Then, negative impacts become apparent and generate public concern. Subsequently, regulations emerge—sometimes incrementally, sometimes dramatically. Finally, mature regulatory frameworks balance economic benefits against social and environmental costs.

Data centers appear to be transitioning from phase one (rapid expansion with minimal oversight) toward phase two (impact awareness and concern). New York's moratorium represents early-stage phase three (initial regulation). Over the next decade, expect continued development of data center regulatory frameworks.

Likely developments include: national-level energy efficiency standards for data centers, water consumption limits in water-stressed regions, requirements for waste heat utilization, renewable energy offset mandates, and possibly limits on the concentration of facilities in single regions. Some of these might emerge through federal legislation, others through state coordination.

There's also the possibility of market-driven solutions. Companies might voluntarily adopt stricter environmental standards if they believe this provides competitive advantages. Consumers increasingly care about corporate environmental responsibility. Cloud customers might prefer providers with superior environmental records. If sufficient market pressure accumulates, companies might exceed regulatory minimums voluntarily.

The evolution of data center policy will also interact with climate policy. As decarbonization becomes a more salient political priority and climate impacts become more apparent, regulations on data center electricity consumption and associated emissions will likely become stricter. A data center powered entirely by renewable energy might be acceptable in 2035, even if a moratorium appeared justified in 2025.

Long-term, the trajectory appears to point toward sustainable data center development—facilities that operate within environmental limits, power themselves with renewable energy, recover waste heat productively, and manage water consumption. Getting from current practice to sustainable practice requires both technological improvement and regulatory incentives. The moratorium contributes to these incentives by creating regulatory pressure.

The Bottom Line: Why This Matters and What Comes Next

New York's proposed data center moratorium, while seemingly a narrow regulatory action, reflects broader tensions in modern technology development. Society benefits enormously from data centers—cloud computing, AI services, and internet infrastructure they enable improve billions of lives. Simultaneously, unfettered expansion of data center development creates real environmental and consumer costs that deserve regulatory attention.

The bill's three-year pause represents a specific policy choice: slow down development temporarily, study impacts carefully, and create space for regulatory updates that might better balance economic and environmental concerns. Whether this approach ultimately proves wise depends on whether the study period generates genuinely useful information and whether resulting regulations actually improve outcomes.

What's certain is that New York's moratorium won't be the last such policy. Other states will face similar pressures and likely adopt similar approaches. The question isn't whether data center regulation will increase—it will. The question is what form that regulation takes and whether it effectively addresses legitimate concerns without unnecessarily harming economic growth.

For companies building infrastructure, for policymakers designing regulations, and for communities hosting data centers, the next three years will be consequential. The studies conducted, regulations developed, and precedents set during this period will likely shape data center policy nationally for a decade. Getting this balance right matters—not just for New York, but for the entire technology industry and the environmental sustainability of our digital infrastructure.

The technology industry will continue advancing, AI will continue developing, and computational infrastructure will continue being necessary. The real challenge is ensuring that this development happens sustainably, equitably, and with appropriate oversight of impacts on communities and environments. New York's moratorium is an attempt to institutionalize that oversight. Whether it succeeds will provide lessons for policymakers nationwide.

FAQ

What is a data center moratorium?

A data center moratorium is a temporary halt on issuing new permits for data center construction. New York's proposed moratorium would pause new permits for three years and ninety days while state agencies study environmental and consumer impacts. During this period, new facilities cannot begin construction, though the ban is explicitly temporary rather than permanent.

How does the New York data center moratorium work?

The bill requires two state agencies to conduct comprehensive studies during the moratorium period. The Department of Environmental Conservation examines water, electricity, and gas consumption impacts, while the Public Service Commission analyzes impacts on consumer utility rates. Based on these studies, agencies can recommend updated regulations to minimize environmental impacts before the moratorium ends and permitting resumes.

What are the environmental impacts of data centers that justify a moratorium?

Data centers consume enormous amounts of water for cooling systems, electricity for operations and cooling, and natural gas for backup generators, creating environmental burdens. Water consumption can stress local supplies in water-scarce regions. Electricity demand increases grid strain and drives up rates for all consumers. The cumulative environmental impact of unregulated expansion justified regulators' concern about studying these impacts before authorizing additional development.

Which other states have introduced similar data center moratorium bills?

As of early 2025, five other states had introduced comparable moratorium or restrictive data center regulations: Georgia, Maryland, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Virginia. This coordinated state-level action indicates that concerns about data center impacts have achieved sufficient prominence that multiple state legislatures are independently proposing solutions.

How does data center development affect electricity rates for consumers?

Data center expansion increases overall electrical demand on regional power grids. When demand increases faster than generation capacity, electricity prices rise for all consumers, not just data center operators. National electricity rates increased 13 percent in 2025, with data center development cited as a major driver. This cost falls on residential and commercial electricity customers generally, creating equity concerns about whether individuals should bear costs for infrastructure serving corporate operations.

Could the moratorium harm economic development and job creation?

Potentially yes. Data center projects represent substantial capital investment and create both construction jobs and permanent operational employment. A three-year moratorium could shift these projects to other states without moratoriums, meaning New York loses investment and employment opportunities that relocate to Pennsylvania, New Jersey, or other neighboring states. This regulatory arbitrage is a genuine economic trade-off that policymakers must consider.

What happens to data center development when the moratorium ends?

The moratorium is explicitly temporary. After three years and ninety days, permit issuance can resume, presumably under updated regulatory frameworks developed during the study period. If the studies justify stricter environmental or consumer protection regulations, these would apply to post-moratorium development. The moratorium is designed to enable informed regulatory development rather than permanently restricting data center growth.

How does this affect AI infrastructure development and innovation?

Data center availability directly impacts AI infrastructure expansion. If New York restricts development while other states permit it freely, AI companies might locate new computing capacity elsewhere, potentially shifting some innovation and development away from New York. This could impact New York's position as a technology hub, though companies can continue serving New York customers from data centers located in other states, which creates the regulatory leakage problem.

What role does renewable energy play in data center regulation discussions?

Renewable energy addresses some but not all data center environmental concerns. Even if a data center operates on renewable power, it still consumes significant water for cooling and requires substantial infrastructure expansion. Additionally, renewable energy capacity is finite—if data centers consume renewable generation that might otherwise serve residential or commercial electricity users, that represents a trade-off rather than a solution. Comprehensive solutions likely require both renewable power and efficiency improvements.

Could other states or the federal government follow New York's precedent?

Quite possibly. If New York's moratorium and subsequent regulatory updates are perceived as successful, other states will likely adopt similar approaches. Federal legislation imposing data center standards nationally is also possible, though less likely given American federalism. The precedent New York sets during the next three years will likely influence regulatory approaches across multiple states and potentially at the federal level.

Key Takeaways

- Legislative Action: New York Senators Krueger and Gonzales introduced a bill halting data center permits for 3 years and 90 days pending environmental studies

- Environmental Drivers: Data centers consume vast quantities of water and electricity, with electricity rate increases of 13% nationally in 2025 partly attributed to data center growth

- Regulatory Trend: Six states have now introduced similar moratorium bills, indicating coordinated state-level response to data center development concerns

- Study Requirements: Legislation mandates comprehensive assessments of water, electricity, and gas impacts, plus consumer rate effects

- Economic Trade-offs: The pause protects consumers and environment but risks shifting investment and jobs to states without moratoriums

- Implementation Challenges: Defining data centers, exempting projects in-pipeline, and preventing regulatory leakage represent significant implementation difficulties

- Long-term Trajectory: Expect continued evolution of data center regulations nationally toward sustainability standards and environmental oversight

Supporting Data & Industry Context

According to industry analysis, data centers represent one of the fastest-growing infrastructure categories in America. Computing power demand doubles approximately every 18 months, driven by cloud computing expansion and artificial intelligence development. This growth trajectory means that moratorium discussions will intensify over the next decade rather than dissipate.

Water consumption concerns are particularly acute in regions already facing water stress. In Arizona and Nevada, where Google, Facebook, and other companies operate major facilities, water availability increasingly constrains expansion. Northern states with more abundant water—like New York, Washington, and Minnesota—have become more attractive for new data center development, shifting environmental burdens from water-scarce to water-abundant regions.

Electricity grid impact varies by region. States with aging power infrastructure face greater challenges accommodating data center demand than states with recently upgraded systems. New York's electrical grid, particularly upstate, has experienced reliability concerns during peak demand periods, making rate and grid stability concerns particularly salient.

The artificial intelligence acceleration timeline creates genuine urgency. Large model training requires extraordinary computational resources. As AI development accelerates, infrastructure demands will multiply. Waiting three years to study impacts might seem reasonable until you realize that in AI timescales, three years represents two full generations of model advancement. Infrastructure constraints could become a genuine bottleneck for innovation if development pauses extend across multiple states.

Related Articles

- New York Data Center Moratorium: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Why States Are Pausing Data Centers: The AI Infrastructure Crisis [2025]

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- Benchmark's $225M Cerebras Bet: Inside the AI Chip Revolution [2025]

- AI Agent Social Networks: The Rise of Moltbook and OpenClaw [2025]

- Valve's Steam Machine & Frame Delayed by RAM Shortage [2026]

![New York's Data Center Moratorium: What the 3-Year Pause Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/new-york-s-data-center-moratorium-what-the-3-year-pause-mean/image-1-1770505606154.jpg)