Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors: The Uncomfortable Truth About Autonomous Vehicle Rollouts

Imagine building a car that can navigate city streets without a human at the wheel. That's supposed to be the future. A marvel of engineering. A technological breakthrough that solves urban transportation forever. Waymo, owned by Alphabet, has raised billions to make this happen. They've deployed cars across six cities and are expanding internationally. The self-driving revolution is here.

Except sometimes, a passenger forgets to close the door. And when that happens, the entire car shuts down.

Not metaphorically. Literally immobilized. Can't drive. Can't complete rides. Can't make money. It just sits there, dead weight on the road.

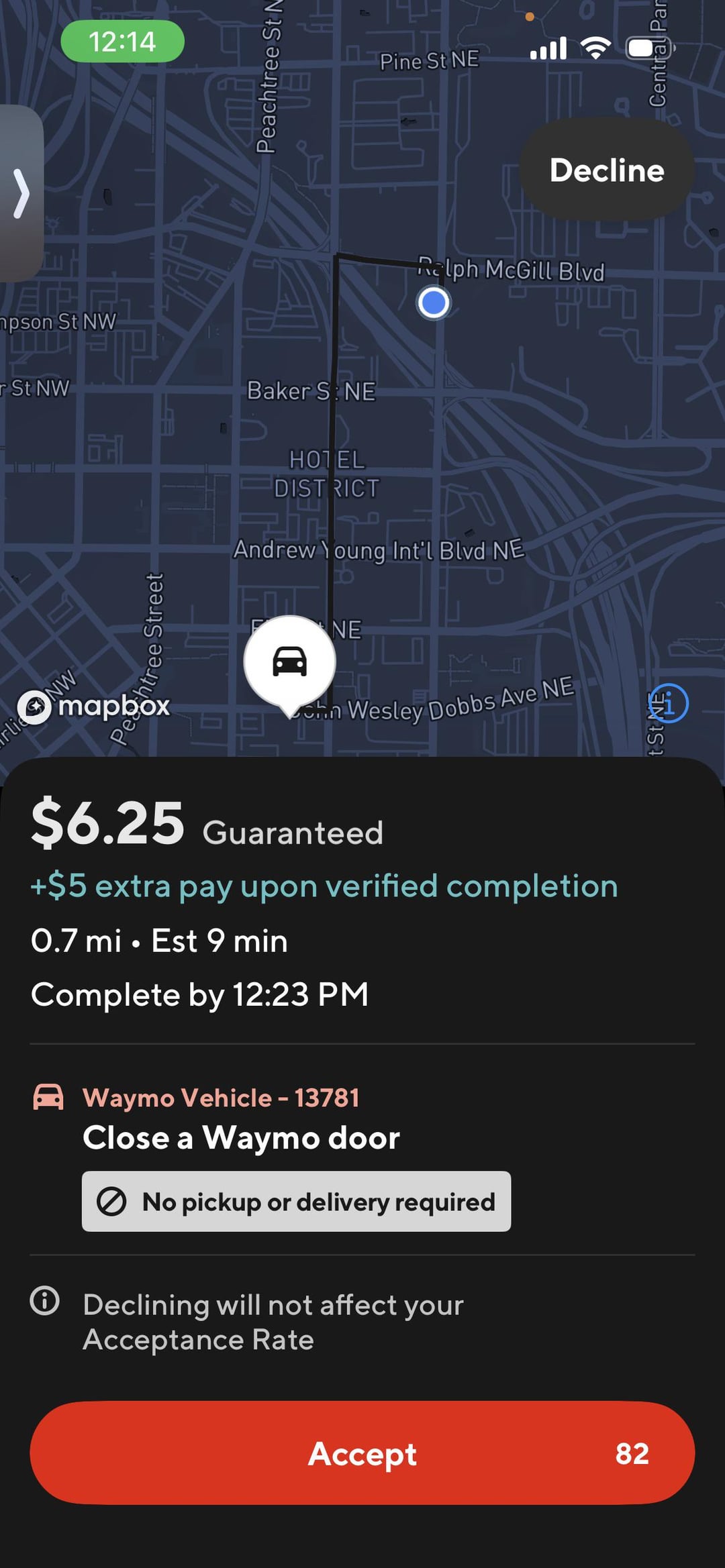

So Waymo did what any company would do: they started paying people to close the doors for them. In Atlanta, they offer DoorDash drivers

What's happening here is more interesting than a funny Reddit story. This reveals something fundamental about where we actually are with self-driving technology in 2025. We're not in the future yet. We're in the awkward middle, where the technology is real enough to work but not robust enough to handle edge cases that a five-year-old understands. And that gap between perception and reality is costing Waymo real money.

This article breaks down what's actually happening with Waymo's autonomous vehicles, why door-closing is such a problem, what it says about the state of self-driving technology, and where autonomous transportation is actually heading. Because if we're going to understand the future of mobility, we need to understand why multi-billion dollar companies are paying gig workers to close car doors.

TL; DR

- The Problem: Waymo vehicles become completely immobilized if a passenger leaves the door open, requiring manual intervention

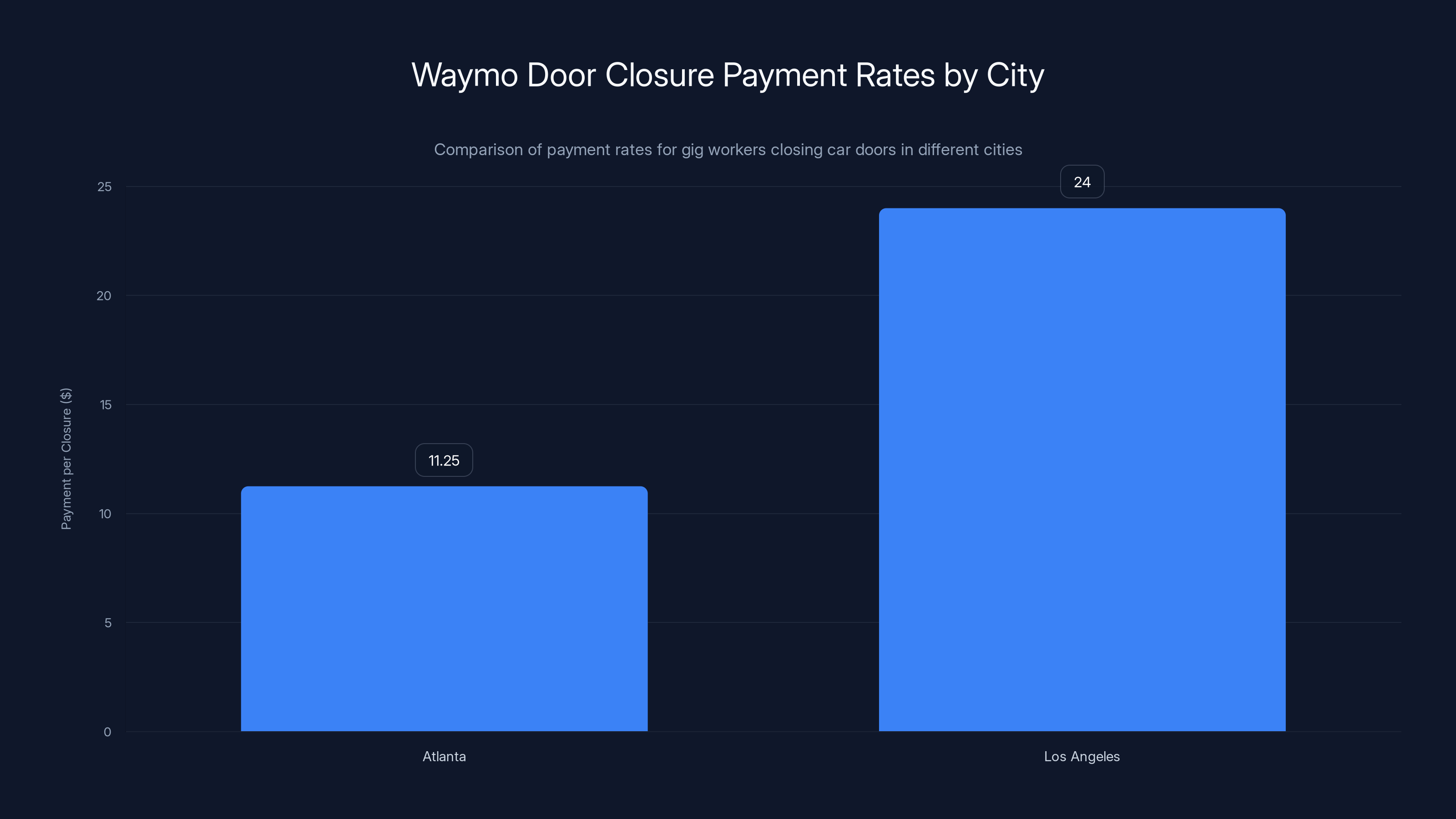

- The Solution: Waymo pays DoorDash drivers 11.25 in Atlanta and up to $24 in Los Angeles to physically close doors

- The Reality: This pilot program reveals gaps in autonomous vehicle design and safety systems that aren't yet mature enough for widespread deployment

- The Implication: Self-driving cars in 2025 still require human workers to solve basic operational problems, contradicting the "fully autonomous" narrative

- The Timeline: Waymo says future vehicles will have automated door closure, but current fleets rely on gig workers as a workaround

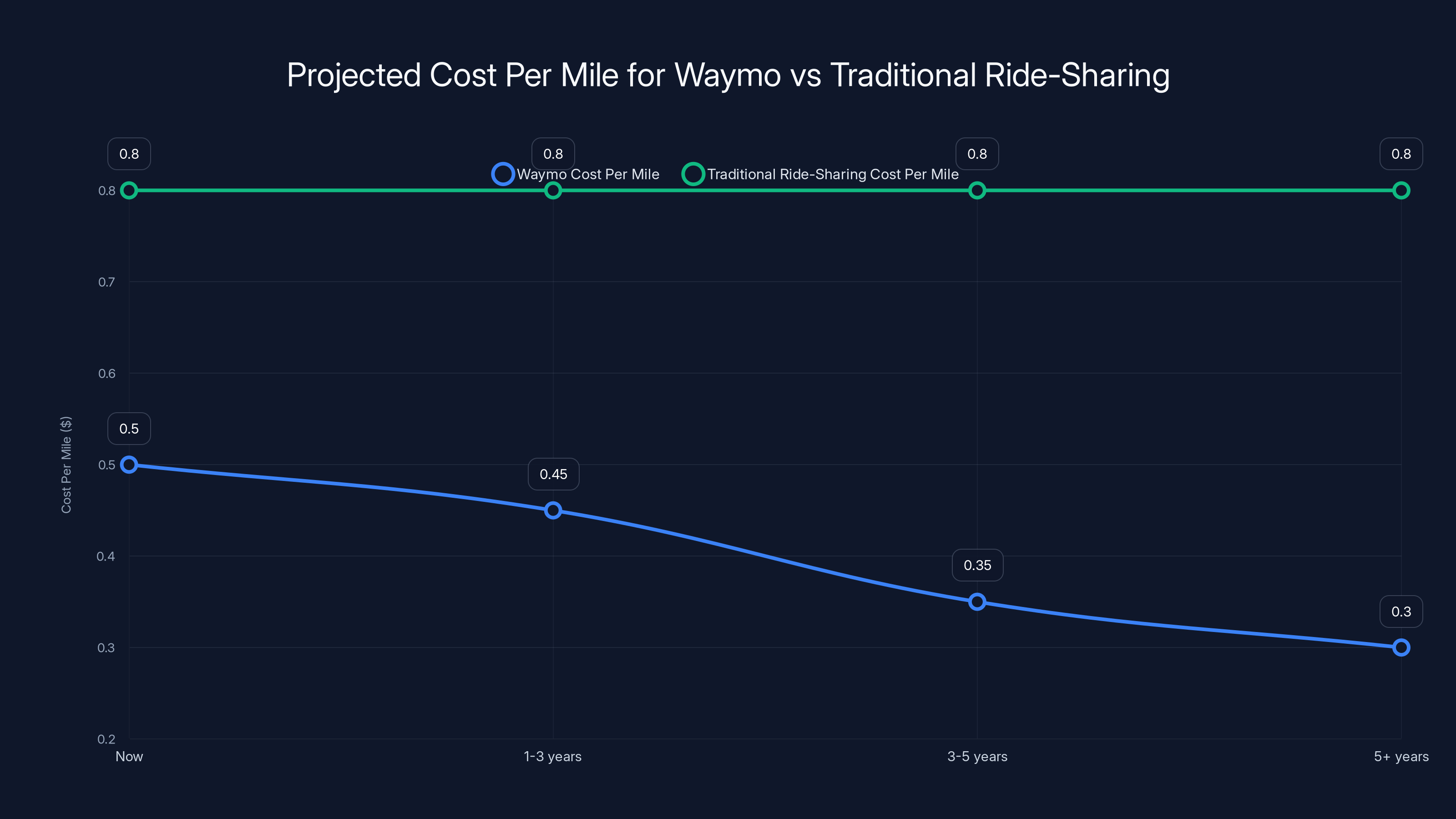

Waymo's cost per mile is projected to decrease over time as technology improves, potentially reaching

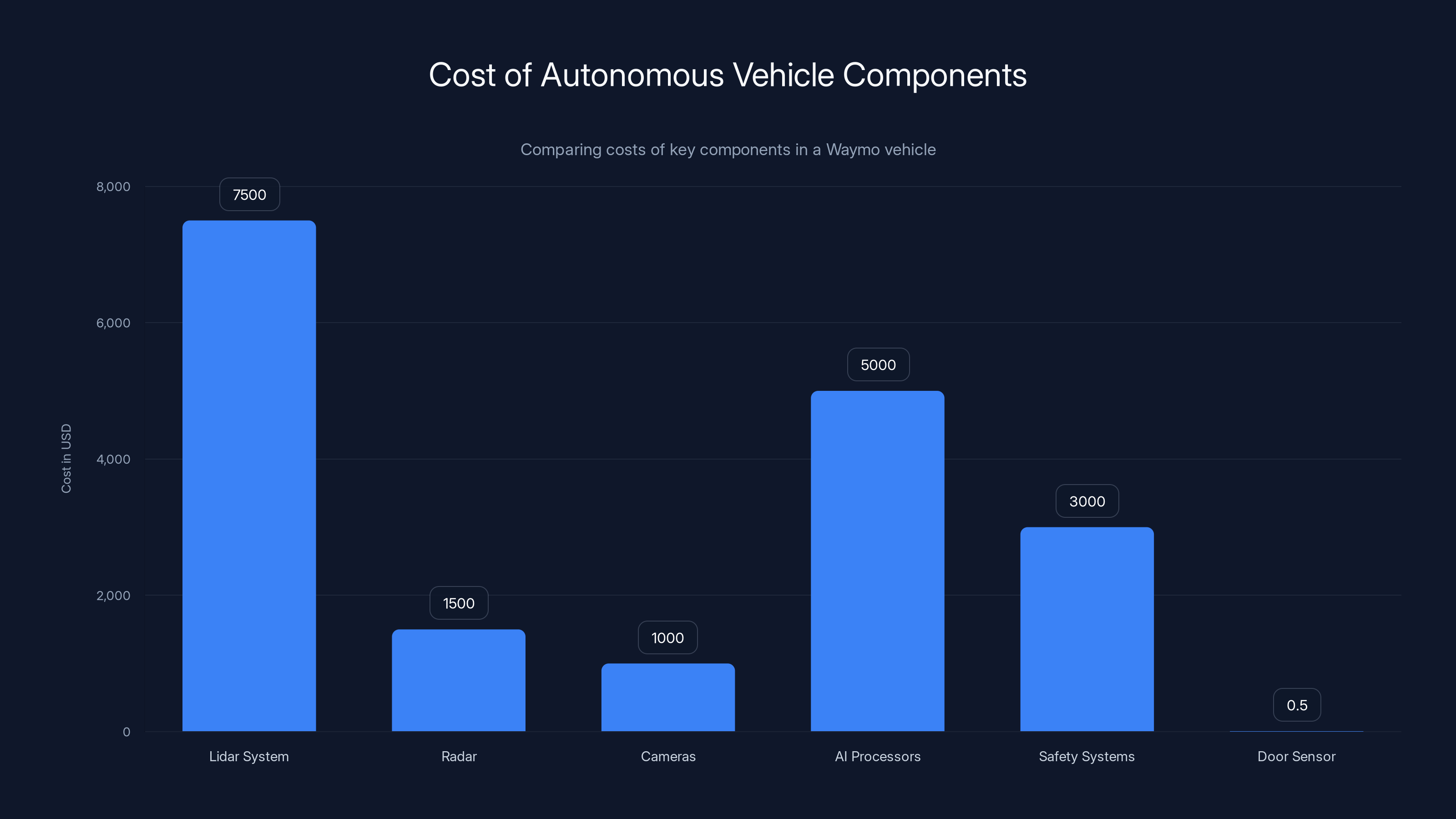

The Door Problem: How a 0.50 Component

A Waymo autonomous vehicle costs somewhere between

But if the door is open, it won't move.

This seems like something that should have been solved. And technically, it could have been. Waymo could have installed automatic door closures years ago. Modern vehicles often have power-assisted door mechanisms. Some luxury cars even have hands-free closing features. For a company that raised $16 billion and operates in six major metropolitan areas, the hardware cost of adding automated door closure would be trivial.

Instead, Waymo's current approach is this: when a door sensor detects an open door, the vehicle enters a safety lockdown. It won't drive. It won't attempt any ride. It won't move forward or backward. The vehicle essentially declares itself non-operational and waits for human intervention.

The design logic makes sense at first glance. Safety first. Don't move if the door is open. It's the same principle that stops a traditional car from starting if the door isn't fully latched. But there's a critical difference: traditional cars have a driver who can immediately close the door. Waymo vehicles don't have anyone inside.

So the company created a system where passengers could, through negligence or accident, completely disable the vehicle. And they did this at scale, across six cities, for thousands of trips daily.

Now, to be fair, Waymo isn't unique in this problem. Tesla's Full Self-Driving beta has faced similar door-latch issues. Cruise (now majority-owned by General Motors) dealt with door problems in its San Francisco operations. This is an industry-wide growing pain. But Waymo's solution reveals something about how autonomous vehicle companies prioritize problems: when faced with a hardware fix or a gig-work workaround, they chose gig work.

Let's think about what this actually costs Waymo. Every door-closure job takes maybe two minutes of DoorDash driver time, plus travel time to the vehicle. That's probably 8-15 minutes total per incident. At

Meanwhile, an automated door-closure system would cost maybe

Waymo's approach suggests they're betting on something else: that the negative press from paying workers to close doors is worth less than the engineering effort to fix it now. Or perhaps they're already planning replacements and don't want to retrofit current vehicles.

The cost of a door sensor is negligible compared to other components like lidar systems, yet it can halt the operation of a $100K vehicle.

Why This Happened: The Gap Between Perception and Product

Waymo spent over a decade building autonomous driving technology. They've accumulated more miles on public roads than competitors could dream of. They have real revenue (though limited). They have partnerships with Uber and now DoorDash. The narrative around Waymo is: this company is ahead, this technology is mature, this is the future arriving now.

But the door-closing program reveals something different. It reveals that Waymo's engineers didn't fully anticipate human behavior at scale.

Or maybe they did anticipate it, but decided it wasn't worth solving in the current generation of vehicles.

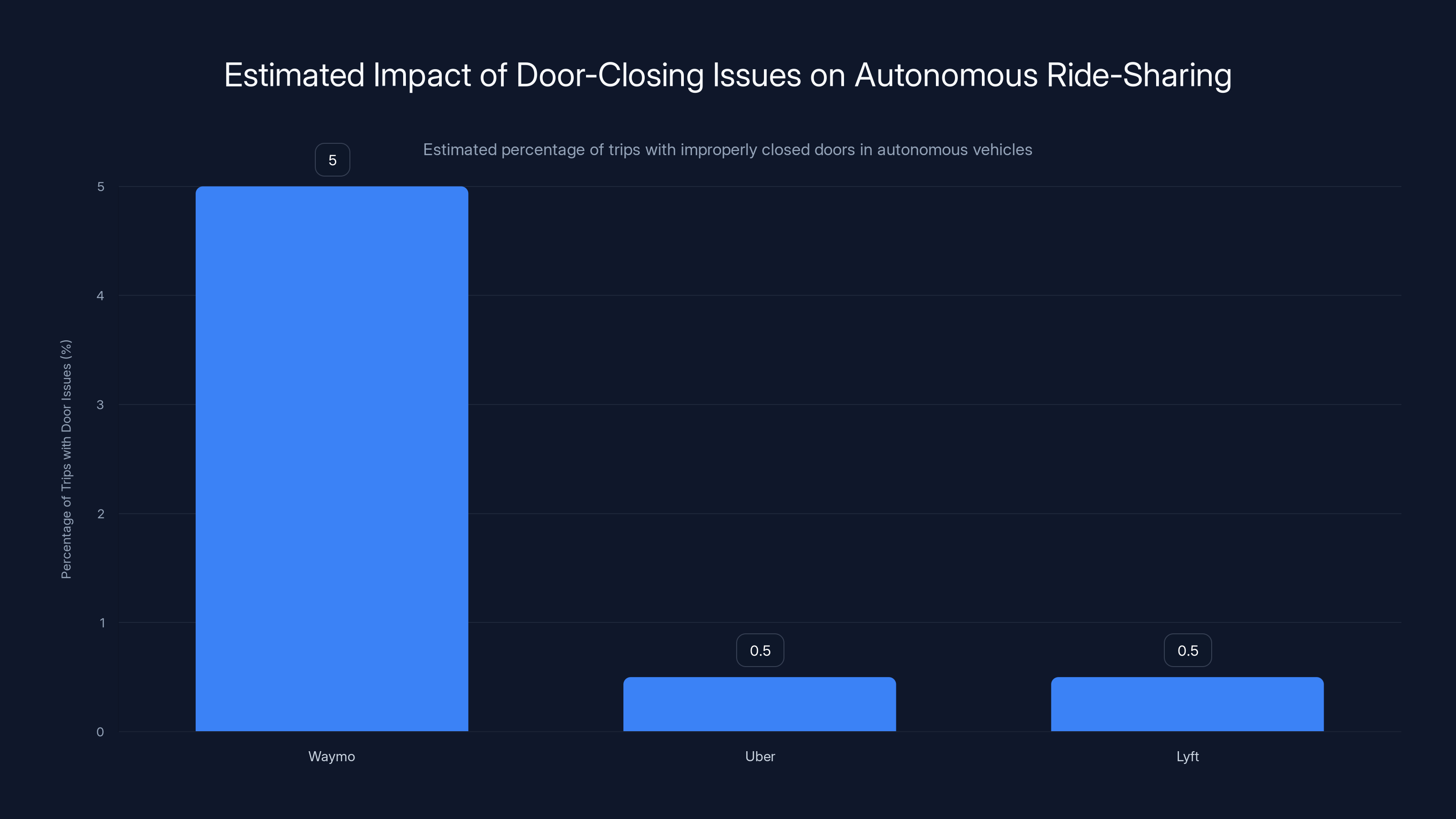

Let's consider what we know: passengers leave doors open sometimes. This isn't rare. Humans are imperfect. They're distracted. They might be on their phone, talking to someone, thinking about their day. Closing the door properly requires explicit intention and attention. For a ride-sharing service, the percentage of trips with improperly closed doors might be 2-5%. Could be higher, could be lower, but it's non-zero.

Waymo's engineers would have estimated this during development. They would have run the numbers. Five percent of 10,000 daily trips means 500 immobilized vehicles per day. That's not manageable without intervention. So the question becomes: how much engineering effort do you invest in solving this versus accepting it as an operational cost?

Traditional ride-sharing (Uber, Lyft) solved this with a driver. The driver closes their own door. Problem solved, no additional cost. Waymo removed the driver to save operational costs, but didn't fully account for what the driver was doing beyond steering the wheel.

Drivers are more than just steering wheels. They're quality control systems. They're problem solvers. They're the exception handler when something unexpected happens. And when you remove them, you have to build exception handlers into the system. Automated systems, processes, or failsafes.

Waymo didn't build a robust exception handler for open doors. They built a temporary workaround using gig workers. It's not fundamentally different from hiring drivers; it's just less transparent and technically less efficient.

The broader context is important here. Waymo is operating under significant competitive pressure. Tesla is making noise about Full Self-Driving. Cruise, despite recent setbacks, is still in the race. Smaller companies like Nuro and Mobileye are making progress in specific niches. The autonomous vehicle market feels like it's at an inflection point, where the company that gets to full autonomy first wins. This creates urgency to deploy, to get vehicles on the road, to show passengers and regulators that it works.

When you're under that kind of pressure, you make trade-offs. You accept technical debt. You use workarounds instead of solving root causes. You pay workers to close doors instead of engineering automatic closure. None of these decisions are irrational individually, but together they create a picture of a technology that's not as mature as the marketing suggests.

The Economics of the Door Workaround: Is This Sustainable?

Let's do the math on Waymo's door-closing program more precisely, because the economics are interesting.

In Atlanta, Waymo initially offered

In Los Angeles, working through the Honk app (a service that's sometimes described as "Uber for towing," but handles any roadside service), payment goes up to $24 per closure. That's more than double the Atlanta rate.

Why the difference?

One possibility is that Atlanta is newer, and Waymo is still optimizing the payment to attract drivers. Another possibility is that LA has higher labor costs and competition. Or perhaps the LA problem is more severe (more open doors, or doors that are harder to close for some reason).

Regardless, the payment structure reveals Waymo's strategy: set the price high enough that it's attractive to available workers, but low enough that it's still cheaper than fixing the problem permanently. This is a classic economic trade-off.

Now, consider what happens as Waymo's fleet grows. If they scale from 1,000 vehicles to 10,000 vehicles, and the door-closure incident rate stays constant, the payment burden scales linearly.

But there's another factor: drivers might not always be available. If DoorDash drivers in a city are busy with actual deliveries, they might not respond quickly to a "close this door" task. Waymo's vehicle sits immobilized, not generating revenue, while a customer waits for a ride that can't happen. From a customer perspective, this is terrible. The ride is cancelled, or delayed, or never happens. That creates negative reputation.

So the true cost of the workaround isn't just the $11.25 payment. It's also the lost revenue from the delayed or cancelled ride, the negative customer experience, and the reputational cost of "even Waymo can't handle this."

Once you factor in all those costs, the economics become less favorable. It might actually be cheaper to just fix it in the hardware.

Let's also consider the precedent. By establishing that gig workers can close doors, Waymo has created an expectation. What happens when they deploy in a new city? Do they offer door-closing tasks to DoorDash drivers there? What if DoorDash isn't available in that city? Do they create an entirely new gig-work category?

This is a system that works at small scale but doesn't obviously scale to a global autonomous vehicle network. And that matters, because Waymo's pitch includes international expansion. They're not building a solution for Atlanta. They're building a solution for the world. A solution that relies on DoorDash drivers in specific cities isn't a global solution.

Waymo faces an estimated 5% of trips with improperly closed doors due to the absence of a driver, compared to traditional services like Uber and Lyft where drivers handle such issues. (Estimated data)

What This Reveals About Autonomous Vehicle Development

The door-closing program is a window into how autonomous vehicle companies make decisions. And it's not a flattering window.

It suggests that Waymo's engineering teams either:

- Didn't anticipate the problem. Which is concerning given the scale of R&D investment.

- Anticipated it but underestimated the frequency. Which is also concerning—how do you miss edge cases this obvious?

- Decided it wasn't worth solving in the current generation. Which is pragmatic but reveals that the vehicles aren't actually finished.

- Solved it but the solution is fragile. Which suggests the workaround is temporary, and permanent fixes are coming.

All four scenarios are problematic in different ways. But they all point to the same underlying issue: autonomous vehicles in 2025 are not ready for the narrative their companies are selling.

The narrative is: "Self-driving cars are here, and they work, and they're safe, and they're the future." The reality revealed by the door program is: "Self-driving cars are partially operational in limited geographies, require human intervention for edge cases, and are still being debugged at scale."

This is normal for any new technology. Aircraft had similar teething problems. Smartphones did. Early cars definitely did. But the autonomous vehicle industry has been selling a specific promise: that the technology is mature enough to remove human drivers. And programs like Waymo's door-closure task reveal that the industry isn't being entirely honest about what "mature" means.

Full autonomy—the ability to operate safely and reliably without any human intervention—requires solving not just the main problem (navigation, collision avoidance, traffic law compliance) but also every edge case that could occur. Door-closure isn't a main problem. It's an edge case. Yet here's Waymo, unable to solve it in a fleet of thousands of vehicles, needing to outsource the solution to gig workers.

What other edge cases haven't been solved? What other problems require hidden human intervention to maintain the illusion of full autonomy?

Consider also that this is happening with Waymo, which is arguably the most mature autonomous vehicle company in the world. If Waymo can't get door-closure right at scale, what does that say about companies further behind in development?

It says they're going to have even more edge cases. Even more problems that require human intervention. Even more workarounds masquerading as solutions.

The autonomous vehicle industry has made real progress. The technology works better than it did five years ago. Waymo's vehicles genuinely can navigate cities more safely than many human drivers. But there's a chasm between "works better than most drivers" and "fully autonomous, no human intervention required." That chasm is wider than most companies are willing to admit.

Comparison: How Other Companies Handle Similar Problems

Waymo isn't alone in facing operational challenges with autonomous vehicles. Let's look at how competitors are handling similar problems.

Tesla's Full Self-Driving has faced numerous reported incidents involving doors, parking, and edge cases. Tesla's approach is typically to push updates through over-the-air software and assume the car's intelligence can learn from problems. The issue is that learning doesn't fix physical problems (like a door latch that doesn't close properly). Tesla hasn't publicly announced a door-closure workaround program, but that's partly because Tesla is still in beta testing rather than commercial deployment.

Cruise, General Motors' autonomous vehicle subsidiary, faced significant regulatory setbacks after a pedestrian incident in 2023. Rather than dealing with edge cases at scale, Cruise has pulled back operations in some markets. When you don't have large fleets operating commercially, door-closure isn't your problem. But it will be if and when Cruise resumes operations at scale.

Nuro, which focuses on autonomous delivery, operates purpose-built vehicles designed specifically for goods delivery (not passengers). These vehicles don't have passenger doors that humans interact with, so the problem doesn't exist. This is clever design—eliminate the variable.

Mobileye (Intel's autonomous driving unit) is focusing on Level 3 and Level 4 autonomy with safety drivers still present in early deployments. With a human in the car, the door-closure problem is trivial. The strategy here is to de-risk by keeping humans in the loop longer.

None of these approaches are wrong, exactly. They're different bets on how to solve the problem of moving from partial to full autonomy. But Waymo's approach—paying gig workers to close doors—is the most explicit admission that the vehicles aren't fully self-sufficient yet.

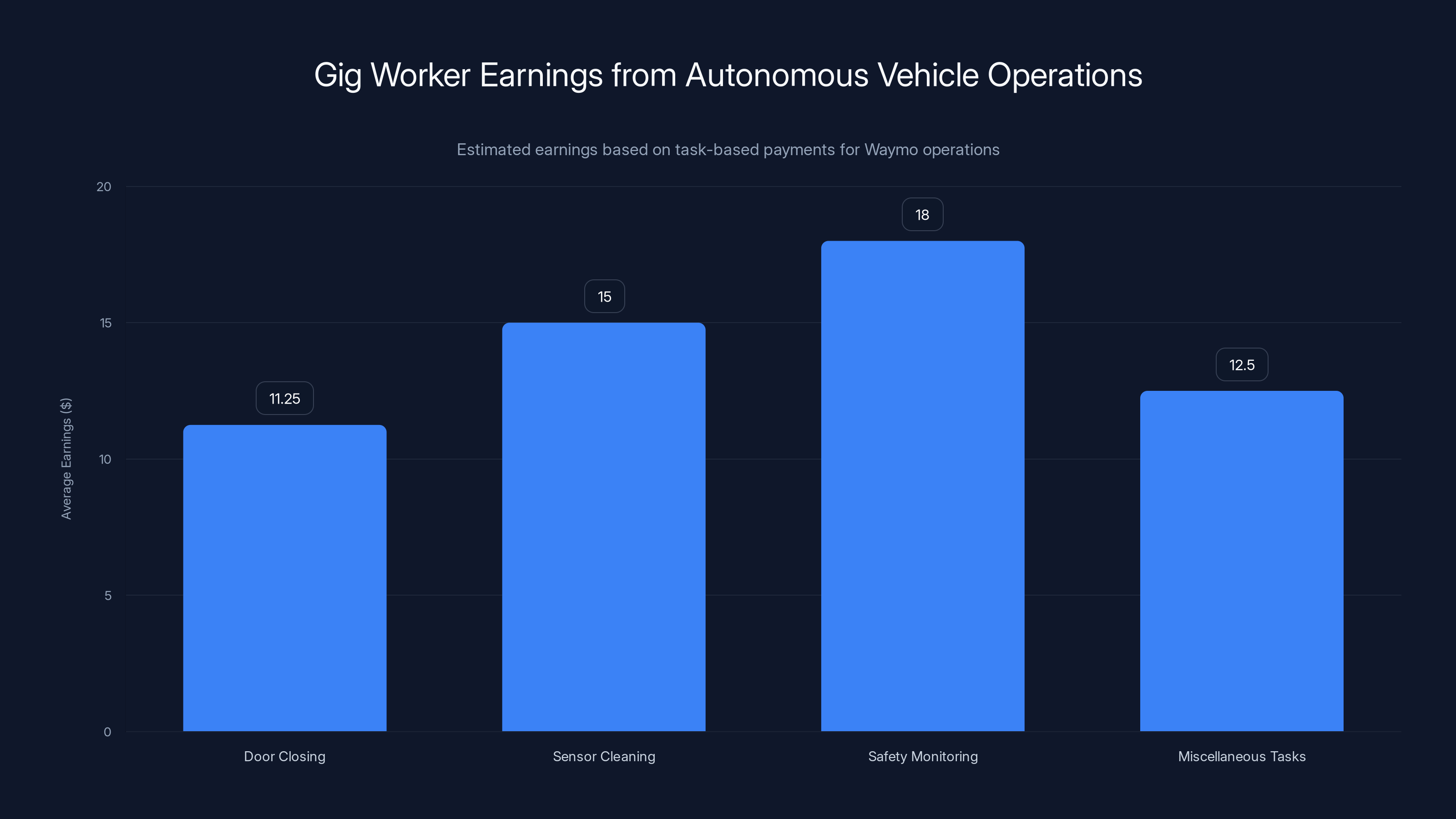

Estimated data shows gig workers earn between

The Broader Pattern: What Else Are We Not Seeing?

The door-closure program raises a larger question: if this is the problem we're seeing, what problems are we not seeing?

Autonomous vehicle companies are notoriously opaque about their operations. They release impressive video clips of their cars navigating traffic. They announce partnerships and funding rounds. They give interviews about the future. But they don't publish detailed reports on: how many times their vehicles fail to operate as expected, what proportion of trips require human intervention, what categories of problems they're still working through, or what they're paying to work around.

Waymo and DoorDash confirmed the door-closure program to TechCrunch because it was already public knowledge via Reddit. They didn't volunteer this information. And only Reddit's documentation made it impossible to keep quiet.

What about the problems that haven't leaked to Reddit? What about the edge cases that are being handled quietly, without public visibility?

For instance:

-

Weather problems. Heavy rain, snow, or fog could confuse sensor systems. Do Waymo vehicles operate normally in these conditions, or do they require human intervention to safely navigate?

-

Construction and road changes. If roads are suddenly blocked or rerouted, can the vehicles adapt, or do they need human help to understand the new geography?

-

Unusual passenger behavior. What if a passenger tries to physically interact with the vehicle in an unexpected way? What if they attempt to influence the driving?

-

System failures. What happens when sensors fail, AI systems produce uncertain outputs, or communication systems are degraded?

-

Legal edge cases. When a vehicle is legally uncertain about something (should I run this light or not, is this pedestrian actually crossing, is this parking legal), what does it do?

For some of these, Waymo probably has good solutions. For others, they might be using hidden human intervention, paying for specialized services, or simply avoiding problematic scenarios.

The autonomous vehicle industry has been optimizing for public-facing metrics: miles driven, number of cities, safety records relative to human drivers. But these metrics don't tell you whether full autonomy is actually achieved. They tell you whether the vehicles are working well enough in their current, constrained deployment scenarios.

There's a difference between "works well enough in six cities under optimized conditions" and "fully autonomous, ready for global deployment without human oversight." That difference is what the door-closure program reveals.

The Role of Mapping, AI, and Real-World Complexity

Understanding why Waymo's door-closure problem exists requires understanding how autonomous vehicles actually work.

Modern autonomous vehicles combine multiple systems: lidar (laser sensors that create 3D maps), radar (for detecting moving objects), cameras (for reading signs and traffic lights), GPS (for knowing where the vehicle is), and AI systems that process all this data to make decisions.

Waymo's approach emphasizes detailed, high-definition mapping. Before Waymo vehicles drive on a road, Waymo has typically already mapped that road exhaustively. They know where every pothole is, where trees block certain sightlines, where traffic patterns tend to slow down. This pre-mapping reduces uncertainty and makes the AI's job easier.

But this approach creates a hidden dependency: Waymo's system is optimized for known, pre-mapped environments. Add a variable (like a passenger leaving the door open, or construction blocking a familiar route), and the system can struggle.

The door-closure problem is actually a symptom of this broader architectural choice. Waymo designed a system that works brilliantly in controlled conditions (known roads, known environments, optimized routes) but doesn't gracefully handle variables that weren't anticipated.

Compare this to human drivers, who handle unexpected situations by... actually thinking about them. A human driver sees an open door and closes it. They don't need to consult a pre-made database of how to close doors. They just do it. The human system is robust to novel situations because humans are general-purpose problem solvers.

Autonomous vehicles are not general-purpose. They're specialists. They're brilliant at doing exactly what they've been trained to do, but struggling with anything outside that domain.

Waymo's solution—paying people to close doors—is actually a pretty honest acknowledgment of this limitation. Instead of pretending the vehicles are fully autonomous, Waymo is essentially saying: "Our vehicles handle 99% of the problem autonomously, but we need humans for the 1%." The door-closure program is a way of managing that 1%.

The question is whether that 1% will continue to shrink, or whether it will stay at 1% as new edge cases emerge. Based on historical patterns with complex systems, it probably stays at some irreducible minimum. There will always be situations where human judgment is needed.

The real question isn't whether Waymo can eventually make vehicles that never need human help. The real question is: at what point is the human intervention rate low enough that autonomous vehicles are economically viable?

For ride-sharing, that might be 2% of trips requiring intervention. For highway trucking, it might be 0.5%. For city delivery in ideal conditions, it might be 5%. Once you're below that threshold for your specific use case, the business model works, even if the vehicles aren't perfectly autonomous.

Waymo is apparently still above the threshold for ride-sharing in some cases (door closures, and presumably other issues we haven't seen), but maybe not above the threshold for delivery (the DoorDash partnership for autonomous delivery may be working better).

Waymo pays gig workers different rates for door closures:

The Labor Angle: Gig Workers and Autonomous Vehicle Operations

Let's look at this from another angle: the labor perspective.

Waymo is paying gig workers to close doors. This is not employment. These are task-based payments through gig platforms. No benefits, no employment contract, no worker protections. It's basically a "microtask" economy application.

From Waymo's perspective, this is efficient. They're not creating permanent jobs or taking on employment liability. They're just paying for discrete services as needed. It's scalable and flexible.

From the gig workers' perspective, it's supplemental income. A DoorDash driver doing deliveries can pick up a door-closing task for $11.25 if they're in the area and have time. It's not a primary income source.

But there's a pattern here that's worth noticing. Autonomous vehicles, which are supposedly replacing human workers, are actually creating new categories of human work. Instead of drivers, we have door-closers. Instead of maintenance technicians, we might have sensor-cleaners or safety-monitors.

This isn't necessarily bad. It's just... ironic. The autonomous vehicle revolution is supposed to eliminate jobs, but it seems to be creating different jobs instead.

Consider the long-term picture. If Waymo scales to 100,000 vehicles globally, and 2% of trips require human intervention of some kind, that's 2,000 interventions per day assuming 100,000 trips per day. If each intervention is paid to a gig worker at an average of

For a company with billions in funding, that's manageable. But it also creates an economics problem: at what point is paying humans cheaper than solving the problem technically?

Waymo says future vehicles will have automated door closures. That's the right answer. But they're not there yet. And meanwhile, they've created a system that depends on human labor to function.

There's also a worker-protection angle. DoorDash drivers closing Waymo doors are doing work for Waymo, but they're not employees of Waymo. They're contractors working through DoorDash or Honk. If they get injured (maybe they get hit by a car while approaching the parked Waymo vehicle), there's ambiguity about who's responsible.

This is a classic gig-economy risk: workers bear the risk, while companies avoid it by classifying people as contractors.

Waymo will eventually solve the door-closure problem in hardware. But the pattern of outsourcing operational problems to gig workers will probably continue. As autonomous vehicles scale, there will always be edge cases, exceptions, and situations that require human judgment. And the easiest way to handle that is to pay humans to deal with it.

Regulatory Implications: What Agencies Are Watching

Autonomous vehicle regulation is still developing. There's no federal standard for what "fully autonomous" means. Different states and municipalities have different requirements.

But Waymo's door-closure program has potential regulatory implications.

If regulators decide that vehicles requiring human intervention don't count as fully autonomous, then every door-closure task is evidence that Waymo's vehicles aren't fully autonomous. That could complicate licensing in jurisdictions that have specific autonomy requirements.

On the other hand, regulators might decide that as long as the system is safe overall, it doesn't matter if some edge cases require human help. In that case, Waymo's approach is fine.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles, which oversees autonomous vehicle deployment in California, has been relatively permissive so far. Waymo operates under a commercial deployment permit that allows ride-sharing and delivery. The permit was granted based on Waymo's safety record and technical capabilities.

But if regulators become aware of significant operational issues requiring human intervention, they might impose new requirements. For instance, regulators could require that companies disclose their intervention rates, or prove that they've exhausted reasonable options for solving problems before turning to human workarounds.

Waymo isn't breaking any rules by paying workers to close doors. But the practice might prompt future rules that require companies to solve such problems in the technology rather than outsourcing them.

There's also a liability angle. If a customer is injured while a Waymo vehicle is immobilized with an open door (maybe they get hit by another car, or they try to close the door and get hit), Waymo could face liability. The company might argue that the customer caused the problem by not closing the door. But courts might decide that Waymo bears responsibility for designing a system that fails safely when customers behave like customers (imperfectly).

From a regulatory perspective, the door-closure issue might actually be seen as a safety feature. A car that refuses to drive when a door is open is a car that can't cause an accident because of an open door. That's not a flaw; that's redundancy. The problem is the operational inconvenience, not the safety flaw.

But if the operational inconvenience forces Waymo to depend on gig workers to keep vehicles operational, that introduces new risks. What if a gig worker closes a door incorrectly? What if they get hit while standing near the vehicle? What if they damage the door mechanism?

These are second-order problems, but they're real.

Waymo pays significantly more for door closures in Los Angeles (

Looking Ahead: When Will Doors Close Automatically?

Waymo has said that future vehicles will have automated door closures. What does that mean, and when might we see it?

Technologically, the solution is straightforward. Modern vehicles already have power windows and locks controlled by computer systems. Adding a power-assisted door closure is just one more component. The challenge isn't the hardware; it's the integration, the cost, and the reliability.

Waymo could retrofit existing vehicles with door-closure actuators. That would cost maybe

Alternatively, Waymo could phase automated door closure into new vehicles as they're manufactured. That's the approach most companies take—solve new problems in future designs rather than retrofitting old ones.

Waymo's next-generation vehicles are probably already in development or at least in planning stages. It would make sense to include automated door closure in those designs. So we might see this solved in 2-4 years, when the new generation of Waymo vehicles enters service.

But here's what's interesting: Waymo probably knew about this problem years ago. Why didn't they include it in earlier designs? Presumably because:

- They underestimated the frequency

- They had other priorities for engineering resources

- They were building on a timeline and couldn't delay for non-critical features

- The gig-worker workaround was cheaper than solving it in hardware

All reasonable tradeoffs, but they say something about how Waymo prioritizes problems. And they suggest that other problems might have been deprioritized the same way.

When Waymo does introduce automated door closure, the company will probably frame it as a routine improvement, not as a fix for a major problem. The narrative will be: "We're continuously enhancing our vehicles." The reality will be: "We couldn't solve door closure without significant operational costs, so we built it into new vehicles."

That's not a criticism exactly—it's how all engineering works. But it's worth acknowledging when the narrative doesn't match the reality.

The Bigger Picture: Autonomy as a Spectrum, Not a Binary

The door-closure program is important because it illustrates something fundamental about autonomy: it's not a binary state. You don't have autonomous vehicles or you don't. Instead, you have vehicles that are autonomous to varying degrees in varying conditions.

Waymo's vehicles are probably:

- Highly autonomous in navigation, collision avoidance, traffic law compliance, and route planning

- Moderately autonomous in handling unusual situations, weather changes, or unexpected obstacles

- Dependent on human workers for edge cases, exceptions, and operational problems

This is normal. This is fine. But it's different from the narrative of "fully autonomous vehicles."

The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has a rating scale from 0 to 5:

- Level 0: No automation

- Level 1: Driver assistance (cruise control, lane-keeping)

- Level 2: Partial automation (most modern cars)

- Level 3: Conditional automation (can drive itself in specific conditions)

- Level 4: High automation (can drive itself in most conditions, but may require human takeover)

- Level 5: Full automation (no human needed, can drive anywhere)

Waymo's vehicles are probably Level 4 in the cities where they operate. They can drive themselves in most conditions but may require human intervention in some cases. They're not Level 5 because they still depend on human help for certain situations.

There's nothing wrong with Level 4. Level 4 is genuinely impressive. But it's not the same as Level 5, and companies sometimes blur the distinction in their marketing.

Understanding where vehicles actually fall on this spectrum is important for customers, regulators, and investors. The door-closure program is evidence that Waymo's current vehicles are solidly Level 4, possibly trending toward Level 5 in future generations, but not quite there yet.

For ride-sharing in limited geographies, Level 4 might be enough. For trucking on highways, Level 4 is probably sufficient. For general-purpose autonomous vehicles that can operate anywhere without any human intervention, we're probably still years away.

Economic Viability: When Does Autonomous Make Sense?

Let's return to the pure economics of Waymo's business model.

Waymo is competing against Uber and Lyft, which use human drivers. The economic advantage of autonomous vehicles is supposed to be lower per-ride costs. Human drivers take a cut (currently around 75% of Uber's revenue), and that's the biggest expense in ride-sharing.

If Waymo can remove drivers and replace them with vehicle costs, they should be dramatically cheaper per ride. A vehicle that costs

Autonomous vehicles should be cheaper.

But if Waymo needs to pay gig workers to solve edge cases, those costs add up. If 2% of rides require human intervention, and each intervention costs

For Waymo, this is acceptable because it's still cheaper than a traditional driver. A 10-mile trip with a traditional driver might cost

So Waymo still wins on economics. But the win margin is smaller than it would be if they didn't need gig workers at all.

This suggests Waymo's path forward:

- Now: Use gig workers for edge cases while continuing to improve the technology

- 1-3 years: Reduce edge cases through better AI, better sensors, or better integration

- 3-5 years: Mostly eliminate the need for gig workers, with only rare exceptions

- 5+ years: Potentially reach genuine Level 5, with no human intervention

If they follow this path, Waymo's business becomes more economically attractive over time. The gig-worker costs are a temporary bridge, not a permanent feature.

The question is whether they can actually follow this path or whether they'll hit a plateau where there's an irreducible minimum of human-required intervention.

Based on historical patterns with complex systems (aircraft, medical devices, finance software), most systems never reach perfect automation. There's always some human judgment required for unusual cases. For Waymo, that might mean they eventually eliminate door-closure issues but still need human intervention for 0.5-1% of trips.

If that's the case, gig-worker costs will be permanent. And Waymo's economic advantage over human drivers will be real but limited.

Waymo is betting that they can get close enough to full autonomy that it's economically viable. The door-closure program is evidence that they're not there yet, but it doesn't mean they won't get there.

The Customer Experience: What It's Like to Ride in a Waymo

Let's zoom out from the technical and economic analysis and think about what the door-closure issue means for customers.

If you're a Waymo customer in Atlanta or Phoenix, you summon a car through the app. A driverless Waymo shows up. You get in, close the door (hopefully properly), and the car drives you to your destination. From a customer perspective, it's kind of magical. No driver. Just a car that knows where you want to go and takes you there.

But behind the scenes, if your door isn't fully closed, Waymo might need to dispatch a gig worker to close it. This is hidden from you. You never know it happened. The experience from your end is probably one of these:

- The car drives normally and you get to your destination (best case)

- The car doesn't move and you're confused (bad case, you're stuck in the car wondering why it's not going)

- Your ride is cancelled and you get an explanation (worst case, but at least transparent)

Waymo's system is probably optimized for handling this so the customer doesn't notice. But the fact that it's possible reveals a gap between the customer experience and the reality of the technology.

For future customers, when Waymo has automated door closures, they won't even think about this issue. It will be a solved problem. But for current customers, the door-closure risk is a reminder that autonomous vehicles are still works in progress.

There's also a trust angle. If customers knew that their Waymo ride might be interrupted because of a door closure, or that gig workers are sometimes dispatched to fix issues with their ride, would they still be as enthusiastic about the technology?

Probably yes—it's still better than a human driver in many ways. But transparency about these issues might actually help with trust. Right now, many people don't know that Waymo needs operational support. If Waymo was more transparent about where they need human help, customers could make more informed decisions.

What Competitors Can Learn

Waymo's door-closure issue is a gift to competitors. It reveals a blind spot, a design flaw that others can learn from.

Cruise has learned from Waymo's experiences and is probably designing their vehicles to avoid similar problems. Tesla is getting similar feedback from Full Self-Driving beta users. Nuro has designed around the problem by using delivery vehicles without passenger doors.

Every competitor now knows: autonomous vehicles need robust handling for passenger behavior. Doors need to close themselves. Seatbelts might need to fasten automatically. Emergency systems need to be idiot-proof (or at least, person-proof).

Waymo paid for this lesson with engineering time, operational costs, and public embarrassment. Competitors get it for free by observing.

This is how technology development works. Early movers hit problems first. Later movers learn from their mistakes. By the time autonomous vehicles are fully mature, we'll have seen and solved hundreds of door-closure-equivalent issues.

But there's a cost to being first. Waymo is bearing it now.

The Path Forward: What Comes Next

Waymo's immediate future probably looks like this:

- Continued operations in current markets (Phoenix, Atlanta, San Francisco, Los Angeles)

- Expansion to new cities, hopefully with fewer operational issues

- Hardware updates that address known issues, including door closure

- Software improvements that reduce the need for human intervention

- Cost reduction as scale increases and operational efficiency improves

Medium-term (2-5 years):

- Potential profitability as operational costs decrease

- International expansion with adapted vehicles and procedures

- New use cases beyond ride-sharing (delivery is the obvious one, but also others)

- Regulatory changes that codify what autonomy means and what companies must disclose

- Increasing competition from other autonomous vehicle companies and potentially from Uber and Lyft developing their own autonomous fleets

Long-term (5+ years):

- Potential maturity of Level 4-5 autonomous vehicles

- Market consolidation as weaker competitors are acquired or shut down

- New business models around autonomous transportation (robotaxis, delivery, long-haul trucking, etc.)

- Regulatory frameworks for insurance, liability, and operation of autonomous vehicles

- Societal shifts in how people think about transportation

The door-closure issue probably won't exist in this future. But there will be other edge cases, other problems that we haven't anticipated yet. The autonomous vehicle industry will continue to solve problems incrementally, occasionally getting stuck (literally, in Waymo's case), and finding workarounds until permanent solutions are implemented.

That's not failure. That's the normal process of technology development and deployment. It's just not as exciting as the marketing suggests.

Conclusion: The Reality of Autonomous Vehicles in 2025

Waymo's door-closure program tells us something important about where autonomous vehicle technology actually stands in 2025.

It tells us that the technology works. Waymo's vehicles genuinely can navigate cities, avoid accidents, and transport passengers. That's not in question. The technology is real and functional.

But it also tells us that the technology isn't finished. There are edge cases that can't be solved in the hardware yet. There are situations where human judgment is needed. There are operational dependencies that the perfect autonomous vision doesn't account for.

This is normal. It's expected. It's actually evidence that Waymo is being realistic about their progress rather than overselling it. The company is deploying vehicles that are good enough for limited, controlled use cases, learning from real-world experience, and improving incrementally.

But there's a gap between this reality and the narrative that autonomous vehicles are taking over. The narrative suggests that the future of transportation is here now. The reality suggests that the future of transportation is probably 5-10 years away, with genuine, unresolved challenges still being worked through.

For investors, this is important. Waymo and other autonomous vehicle companies are making progress, but they're not at the finish line. For passengers, it's important to understand that today's autonomous vehicles are good but not flawless. For regulators, it's important to set standards that distinguish between Level 4 (high automation with limitations) and Level 5 (full automation without limitations), rather than treating them as equivalent.

And for the gig workers being paid to close Waymo doors, it's perhaps most important to recognize that the autonomous vehicle revolution is creating new forms of work, even as it promises to eliminate the need for human drivers. The labor that humans do is shifting, not disappearing.

The door-closure program is a small detail. But it reveals the reality of autonomous vehicles in 2025: impressive progress, but still incomplete. Functional, but still learning. Deployed, but still not fully autonomous.

That's not a failure. That's just where we are.

FAQ

What is Waymo and why does it need door-closing services?

Waymo is an autonomous vehicle company owned by Alphabet that operates self-driving cars across six cities. When a passenger fails to fully close the car door, Waymo's safety systems prevent the vehicle from moving to protect against accidents. This immobilizes the vehicle entirely, so Waymo has hired gig workers through DoorDash and other platforms to physically close doors when passengers leave them ajar.

How much does Waymo pay workers to close car doors?

Waymo pays different rates in different markets. In Atlanta, DoorDash drivers receive

Why doesn't Waymo just install automatic door closers?

Automatic door-closing hardware exists and is technologically simple, costing approximately

Is this a sign that autonomous vehicles aren't really autonomous?

Waymo's door-closure workaround reveals that current vehicles are Level 4 autonomous (high automation with specific limitations) rather than Level 5 (fully autonomous in all conditions). Waymo can navigate traffic, avoid accidents, and make complex driving decisions, but some edge cases still require human intervention. This is normal for emerging technology and doesn't mean autonomous vehicles are failures, just that they're incomplete.

How often does the door problem actually occur in practice?

Waymo hasn't officially disclosed the frequency of door-closure incidents, but Waymo confirmed the program is real, suggesting it happens regularly enough to justify the operational cost. Industry estimates suggest 2-5% of ride-sharing trips might involve passengers not fully closing doors, though Waymo's actual rate could be higher or lower depending on customer education and door design.

Will this problem eventually be solved permanently?

Yes. Waymo has stated that future generations of vehicles will include automated door-closing mechanisms. As new vehicles enter the fleet over the next 2-4 years, this issue should disappear. The current reliance on gig workers appears to be a temporary operational bridge until hardware improvements are rolled out at scale.

What does this mean for the future of autonomous vehicles and employment?

Waymo's approach suggests that autonomous vehicle adoption will create new categories of work rather than eliminating all human labor. Instead of professional drivers, we might see gig workers handling edge cases, maintenance tasks, or operational exceptions. This represents a shift in labor patterns rather than complete automation of transportation.

How do other autonomous vehicle companies handle similar problems?

Competitors like Tesla, Cruise, and Nuro have different approaches. Tesla continues improving Full Self-Driving through software updates but hasn't announced similar workaround programs. Cruise has reduced operations in some markets rather than scaling edge-case solutions. Nuro designed purpose-built vehicles without passenger doors, eliminating the problem entirely. Each approach reflects different philosophies about when technology is ready for deployment.

Key Takeaways

- Waymo pays DoorDash drivers 11.25 in Atlanta and up to $24 in Los Angeles to physically close vehicle doors left open by passengers

- When doors are left open, Waymo vehicles become completely immobilized—they enter a safety lockdown and can't complete any rides

- This reveals that current Waymo vehicles are Level 4 autonomous (high automation with limitations) rather than truly Level 5 (fully autonomous)

- Waymo likely determined it's cheaper to pay gig workers for edge cases than to retrofit existing vehicles with automated door-closing hardware

- The program demonstrates how autonomous vehicle companies depend on hidden human labor to maintain the appearance of full autonomy

- Future Waymo vehicles will include automated door closures, but current fleets use gig workers as a temporary operational workaround

- Different markets show different payment rates, suggesting Waymo is optimizing costs and labor availability by region

- This edge case reflects a broader pattern: autonomous vehicles can handle 95-98% of situations autonomously but still need humans for unexpected scenarios

Related Articles

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- Waymo's DC Robotaxi Campaign: How AI Companies Are Reshaping City Regulation [2025]

- Waymo's Sixth-Generation Robotaxi: The Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Waymo's Nashville Robotaxis: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

- How Waymo Uses AI Simulation to Handle Tornadoes, Elephants, and Edge Cases [2025]

![Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-waymo-pays-doordash-drivers-to-close-car-doors-2025/image-1-1770959302201.jpg)