The Irony Nobody Expected: Robots Needing Humans to Close Doors

Imagine building the most sophisticated autonomous vehicle on the planet. You've invested billions. Your engineers have perfected lidar, radar, and camera systems that can detect objects in darkness and heavy rain. Your AI can navigate complex intersections, read traffic signals, and respond to emergency vehicles. Then a passenger leaves the door open, and your entire vehicle grinds to a halt.

This isn't a science fiction scenario. It's happening right now on the streets of San Francisco and Los Angeles.

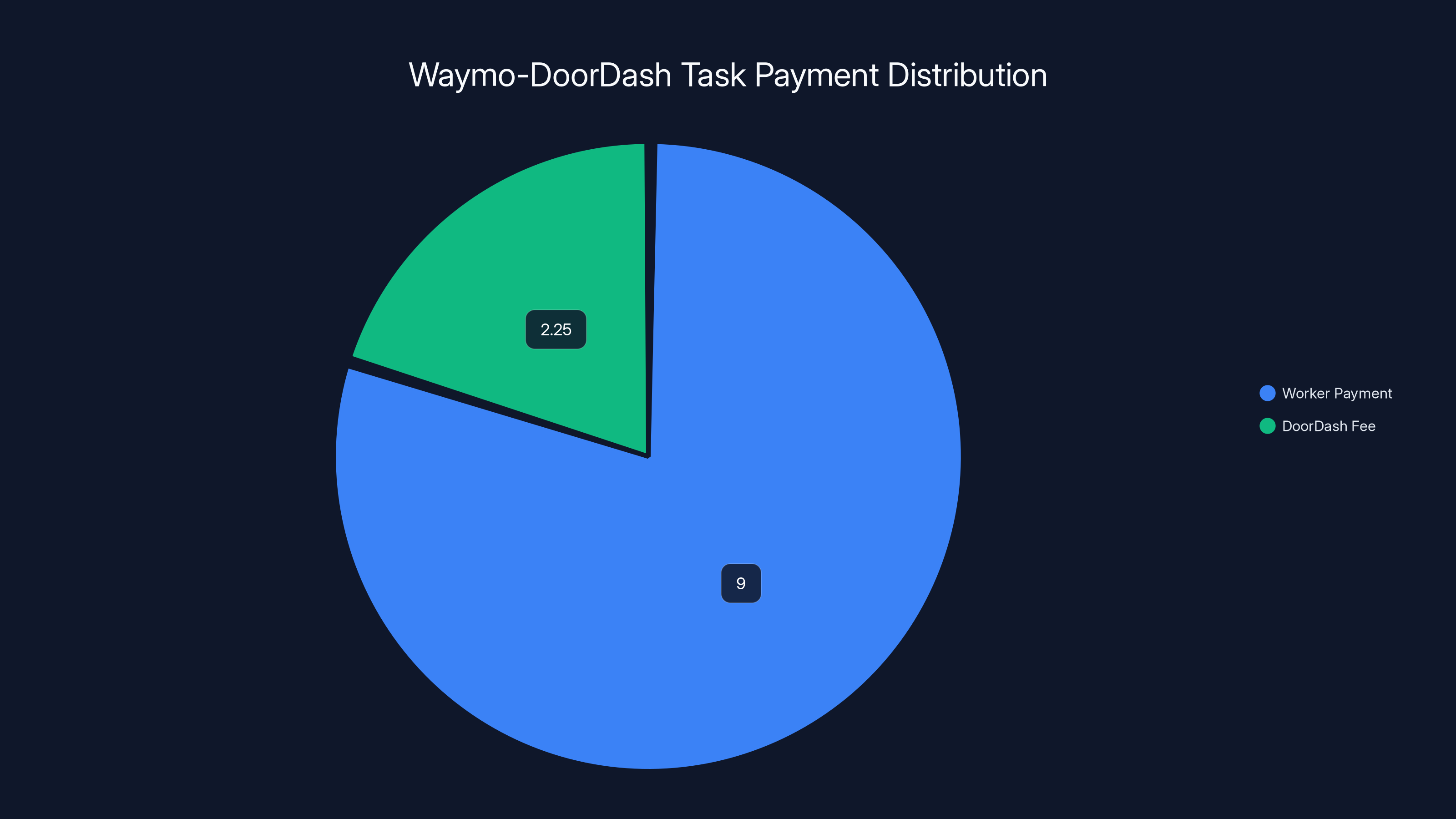

Waymo, the autonomous vehicle division of Alphabet, has encountered a problem so frustratingly human that it required an equally human solution: hiring gig workers from DoorDash to physically close doors that passengers leave ajar. For $11.25 per task, DoorDash workers are receiving notifications when a Waymo vehicle can't proceed because its door remains open, pulling them away from food deliveries to become the unexpected maintenance crew for self-driving cars.

It's the kind of problem that exposes something uncomfortable about the future of autonomous vehicles. For all the hype about fully automated transportation, these sophisticated machines still depend on humans for tasks that are trivial to biological beings but impossible for silicon and steel. And if Waymo—the clear leader in the autonomous vehicle space—can't solve this, what does that tell us about the timeline for fully autonomous fleets?

This situation reveals something deeper than just a design flaw. It's a preview of how the autonomous vehicle industry might actually look when it scales: a hybrid system where cutting-edge technology is bolstered by flexible human labor. It's not robots replacing workers. It's robots creating entirely new types of work that didn't exist five years ago.

The Waymo-DoorDash partnership, initially discovered when a DoorDasher posted their $11.25 door-closing offer on Reddit, started as a pilot program just a few weeks before the discovery went public. The companies claim this is a rare event, but the fact that they've formalized it into a notification system suggests otherwise. And as Waymo's sixth-generation vehicles—the new Zeekr Ojai minivans—enter service, this situation will become even more prevalent, simply because there will be more vehicles on the road encountering more passengers.

What started as a fringe engineering challenge has become a case study in why the autonomous vehicle timeline keeps extending. The technology works. The safety records prove it. But the real-world deployment of autonomous fleets requires solving hundreds of edge cases, many of which can't be solved with better AI or more sensors. They need human judgment, dexterity, and presence.

Understanding Waymo's Autonomous Vehicle Hierarchy

Before diving into the door-closing problem, it's essential to understand what Waymo actually is and why it's the gold standard in the robotaxi space. Waymo started as Google's self-driving car project back in 2009. For years, it was the laughingstock of the internet. People made jokes about Google cars crashing into statues and getting confused by cyclists. But something changed around 2018: Waymo actually started working.

The company spun off from Google and became its own entity under Alphabet's umbrella, with significant backing but also pressure to actually operate as a business rather than a research project. By 2023, Waymo had begun commercial operations in Phoenix, Arizona. By 2024, it expanded to San Francisco and Los Angeles. Today, you can legitimately order a Waymo robotaxi in six different cities, and the company has publicly committed to launching in a dozen more, plus London, making it a genuinely global operation.

What distinguishes Waymo from competitors like Tesla's Full Self-Driving or Aurora's autonomous trucks is that Waymo isn't trying to retrofit autonomous driving onto existing vehicle designs. Instead, the company works with manufacturers like Jaguar, Hyundai, and now Zeekr (a Chinese EV maker) to build vehicles from the ground up as autonomous platforms.

The current primary vehicle is the Jaguar I-PACE, an electric vehicle that Waymo has heavily modified. You'll see these distinctive black and white EVs all over San Francisco's streets. They have an unusual look because Waymo has removed the steering wheel, pedals, and most human controls. The entire vehicle is controlled by artificial intelligence. Passengers enter through doors that open and close via button presses, sit in a spacious interior without a driver's seat, and communicate with the vehicle through a phone app and an in-car interface.

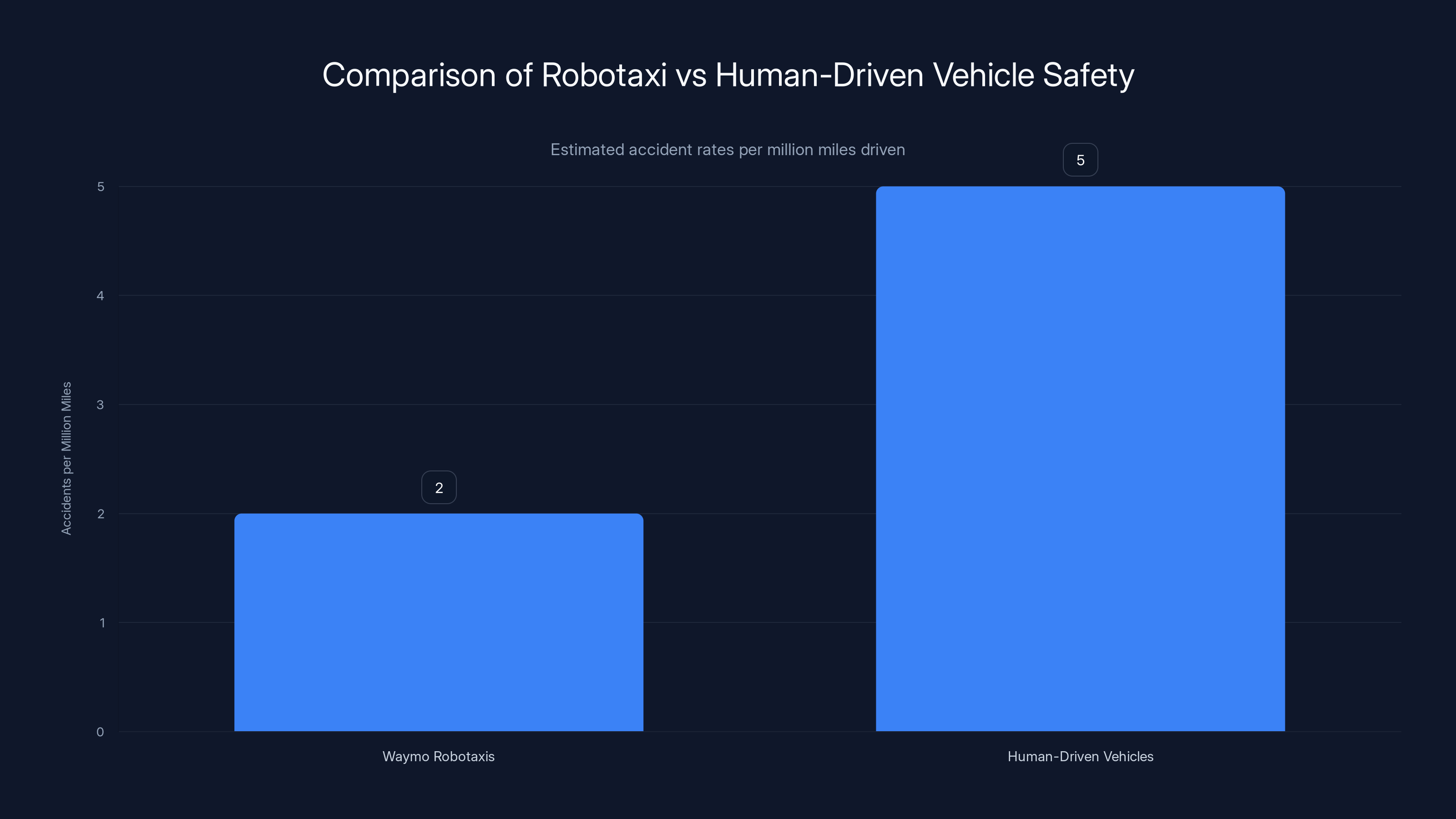

These vehicles work remarkably well for their intended purpose. Waymo's safety data shows that their robotaxis have accident rates far lower than human-driven vehicles. They don't speed, don't drive recklessly, and don't have road rage incidents. They're programmed to follow every traffic law. They can even pick up passengers at airport terminals, something that was considered laughably impossible just five years ago.

But here's where the gap emerges between "works well in trials" and "fully autonomous operation": the vehicles are controlled by camera systems, lidar (light detection and ranging), radar, and ultrasonic sensors, all feeding into a central AI that makes navigation decisions. These systems are extraordinary, but they have specific limitations.

A Waymo vehicle can detect that a door is open (the sensors see a physical obstruction or a gap in the vehicle's expected profile). But detecting a door is open and deciding what to do about it are completely different problems. The vehicle's AI cannot physically close the door. Autonomous vehicles have robotic arms or door actuators in some experimental prototypes, but Waymo's current fleet doesn't include them. The vehicles also can't diagnose why the door is open. Is it a malfunction? Did a passenger leave it open intentionally? Is there an object jamming it? Should the vehicle contact support, or should it just... wait?

This is where human intelligence becomes necessary. A human can immediately understand that a passenger didn't close the door fully, that it's a trivial problem, and that the solution is straightforward. To an autonomous vehicle's decision tree, the situation is ambiguous without human context.

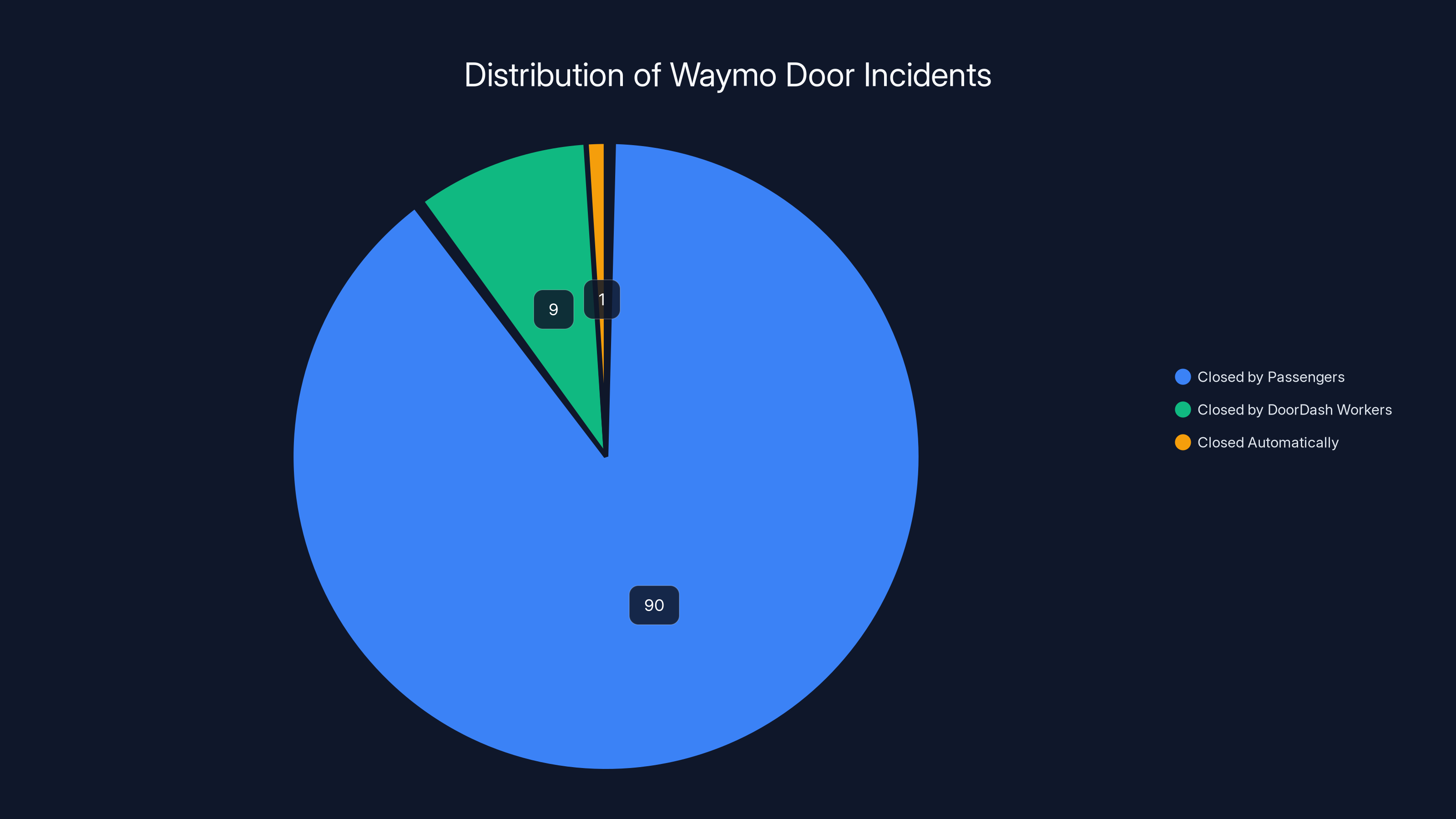

Estimated data suggests most doors are closed by passengers, with a small percentage requiring DoorDash workers or automatic systems.

The Door Problem: A Symptom of Larger Edge Cases

The door situation isn't really about doors. It's a symptom of a much larger challenge in autonomous vehicle deployment: edge cases.

In machine learning and autonomous systems, an edge case is a situation that falls outside the normal range of expected inputs. For self-driving cars, edge cases include things like:

- A child running into the street

- A cyclist riding in an unpredictable pattern

- A traffic signal that's broken or being manually directed by a police officer

- A passenger having a medical emergency

- A vehicle malfunction that requires human decision-making

- Doors left open

Waymo's AI is trained on millions of miles of driving data. It can handle thousands of edge cases that would challenge a human driver. But the long tail of possible situations—especially ones involving human behavior—is nearly infinite.

A passenger leaving a door open falls into a specific category of edge case: human error at the service interface level. It's not a dangerous situation. It's not a threat to safety. It's just... inconvenient. The vehicle can't proceed, but the reason why is something a five-year-old could understand and fix instantly.

Here's the mathematical problem Waymo faces:

Waymo has driven billions of miles (both real and simulated), but the denominator is essentially infinite. You can never collect enough data to train an AI system that handles every possible edge case. Eventually, you hit a wall where the remaining issues are too rare or too specific to solve through more AI development.

That wall is where humans come in.

The DoorDash solution is, in a weird way, brilliant. Rather than engineer a mechanical system to close doors, monitor it for failures, integrate it with the vehicle's AI decision-making system, test it exhaustively, and deploy it across thousands of vehicles, Waymo simply created a notification system that says "we have a vehicle with an open door nearby." Human workers—already distributed across cities doing gig work—can respond to these notifications for a small fee.

It's not elegant. It's not what you'd see in a promotional video. But it works, and it scales with minimal engineering overhead.

The door problem is just the first of what will be many such hybrid solutions. Other obvious candidates include:

- Vehicles blocked by obstacles the AI can't navigate around

- Broken or ambiguous traffic signals that require human judgment

- Requested detours or changes that the passenger communicates verbally

- Vehicle malfunctions that need human diagnostics

- Parking situations that don't match any trained scenario

- Passenger assistance needs (elderly passengers, people with mobility issues)

Each of these could theoretically be solved with more AI or better sensors. But each one adds complexity, cost, and risk of failure. Using humans as the fallback for rare situations becomes increasingly attractive as fleets scale.

Over five years, using human gig workers for door-closing tasks is estimated to be cheaper (

How the Waymo-DoorDash Partnership Actually Works

Understanding the mechanics of the Waymo-DoorDash arrangement requires looking at how both services operate and how they've integrated their systems.

When a Waymo vehicle encounters a situation it can't resolve—like a door that won't close—the vehicle doesn't just sit there silently. Instead, it's part of a fleet management system that continuously communicates with Waymo's operations center. The vehicle sends a notification that it has an open door and requests assistance.

Waymo's systems then check whether a DoorDash worker is nearby. The DoorDash app, which millions of people use daily for food delivery, is a perfect platform for distributing these notification requests. Workers who opt into the program receive a notification on their phones saying something like "Close a nearby Waymo door for $11.25." The location is transmitted, and if they accept, they head to the vehicle.

When the worker arrives, they close the door, confirm completion through the app, and the Waymo vehicle receives clearance to proceed. The worker gets paid instantly through DoorDash's payment system. It's a simple system, but it represents a fascinating integration of two very different technologies and business models.

Waymo and DoorDash haven't released specifics about how workers are incentivized or how much Waymo pays DoorDash for the privilege of using their network, but the $11.25 per task payment to workers suggests that Waymo's actual cost is higher (DoorDash takes a cut). The companies claim this is a "pilot program," suggesting it's experimental and not yet permanently integrated into Waymo's operations.

But here's what's important: the fact that this system exists at all reveals that Waymo anticipated this problem. Companies don't create notification systems, integrate them with third-party gig work platforms, and establish payment mechanisms for situations they think are impossible. The fact that this is formalized suggests that open doors happen regularly enough to justify the infrastructure.

The partnership also reveals something about where Waymo sees the immediate future of autonomous vehicles: not fully autonomous systems that need zero human intervention, but rather human-in-the-loop systems where AI handles 99% of scenarios and humans handle the remaining 1%.

This isn't a failure of autonomous vehicle technology. It's actually the pragmatic acknowledgment that perfect autonomy is a harder problem than near-perfect autonomy plus human backup. The economics favor using humans for rare edge cases rather than engineering perfect solutions for every possible situation.

Waymo's Hardware Evolution: From the Chauffeur to the Ojai

To understand why Waymo is even dealing with door issues, you need to look at the evolution of their vehicle hardware. The Waymo robotaxi isn't a single vehicle design; it's a platform that evolves over time.

Waymo's first autonomous vehicle designs were something called the "pod"—small, bubble-like two-seaters that looked like golf carts. These vehicles were purpose-built for autonomous operation but lacked practicality for real-world deployment. They couldn't fit passengers with luggage. They couldn't accommodate wheelchairs. They were hard to manufacture at scale.

Waymo learned from this and shifted to partnering with established automakers. The current primary vehicle is the Jaguar I-PACE, a luxury electric vehicle that Waymo has modified extensively. It's a good middle ground: it's a real car that people recognize, it has enough space for actual passengers, and it's built by a major manufacturer who can support production at scale.

But Jaguar's I-PACE wasn't designed to be a robotaxi. Its doors are traditional hinged doors that Waymo has modified to open and close via software commands. This is where the door-closing problem originated. Traditional hinged doors can get stuck, can be left partially open, and require precise mechanical operation.

Enter the Zeekr Ojai, the new sixth-generation Waymo vehicle unveiled at CES 2026.

The Ojai is a purpose-built autonomous minivan designed specifically for Waymo's robotaxi fleet. Unlike the I-PACE, the Ojai features motorized sliding doors—the kind you see on Honda Odysseys and Toyota Siennas. Sliding doors are inherently more reliable for automated operation. They either fully close or they fully open; there's less ambiguity. A motor can reliably close them. They don't jam in intermediate positions as easily.

Waymo is starting to deploy the Ojai for employee rides in Los Angeles and San Francisco, with broader public rollout coming soon. Once the Ojai becomes the primary vehicle in the fleet, the door-closing problem should largely disappear. The new vehicle addresses the underlying design limitation that created the problem in the first place.

This is actually telling. It reveals that Waymo recognized the door issue wasn't a software problem; it was a hardware problem. You can't fix it with better AI or more sensors. You fix it with better vehicle design.

The Ojai also includes other upgrades that address real-world operational challenges. The sixth-generation Waymo Driver includes:

- Improved camera systems with better low-light performance

- Enhanced lidar arrays that work better in rain and fog

- Upgraded radar for detecting small objects at distance

- Microphones that can pick up emergency vehicle sirens, allowing the vehicle to predict where emergency vehicles are coming from before they're visible

- Better thermal imaging for detecting pedestrians in darkness

These upgrades aren't theoretical improvements. They address real operational challenges that emerged from deploying robotaxis in actual cities. You can't predict all these issues from simulation. You have to deploy vehicles, watch them fail, analyze the failures, and then update the hardware.

Waymo's strategic milestones are expected to have varying impacts, with operating cost reduction and 24/7 service likely to be most transformative. (Estimated data)

The Gig Economy's Unexpected Pivot into Robotaxi Support

The DoorDash component of this story is equally interesting because it reveals how gig work is evolving in response to automation.

Gig work has a reputation as precarious, low-wage labor. Food delivery drivers make minimal money after accounting for vehicle wear and tear and gas costs. But gig platforms like DoorDash have infrastructure that makes them valuable for purposes beyond their original design: a distributed network of workers, payment systems, routing algorithms, real-time notifications, and performance tracking.

Once you have all these components built for food delivery, you can repurpose them for other tasks. Waymo's door-closing requests are essentially just another type of task that can be distributed through the DoorDash platform. From DoorDash's perspective, it's additional work they can offer their drivers. From Waymo's perspective, it's access to a distributed labor force already optimized for logistics and real-time task allocation.

This is actually a sophisticated integration of two very different businesses. Waymo brings autonomous vehicle technology and a fleet of robotaxis. DoorDash brings a logistics network and worker management infrastructure. Neither company needs to build the other's capability; they just integrate their existing systems.

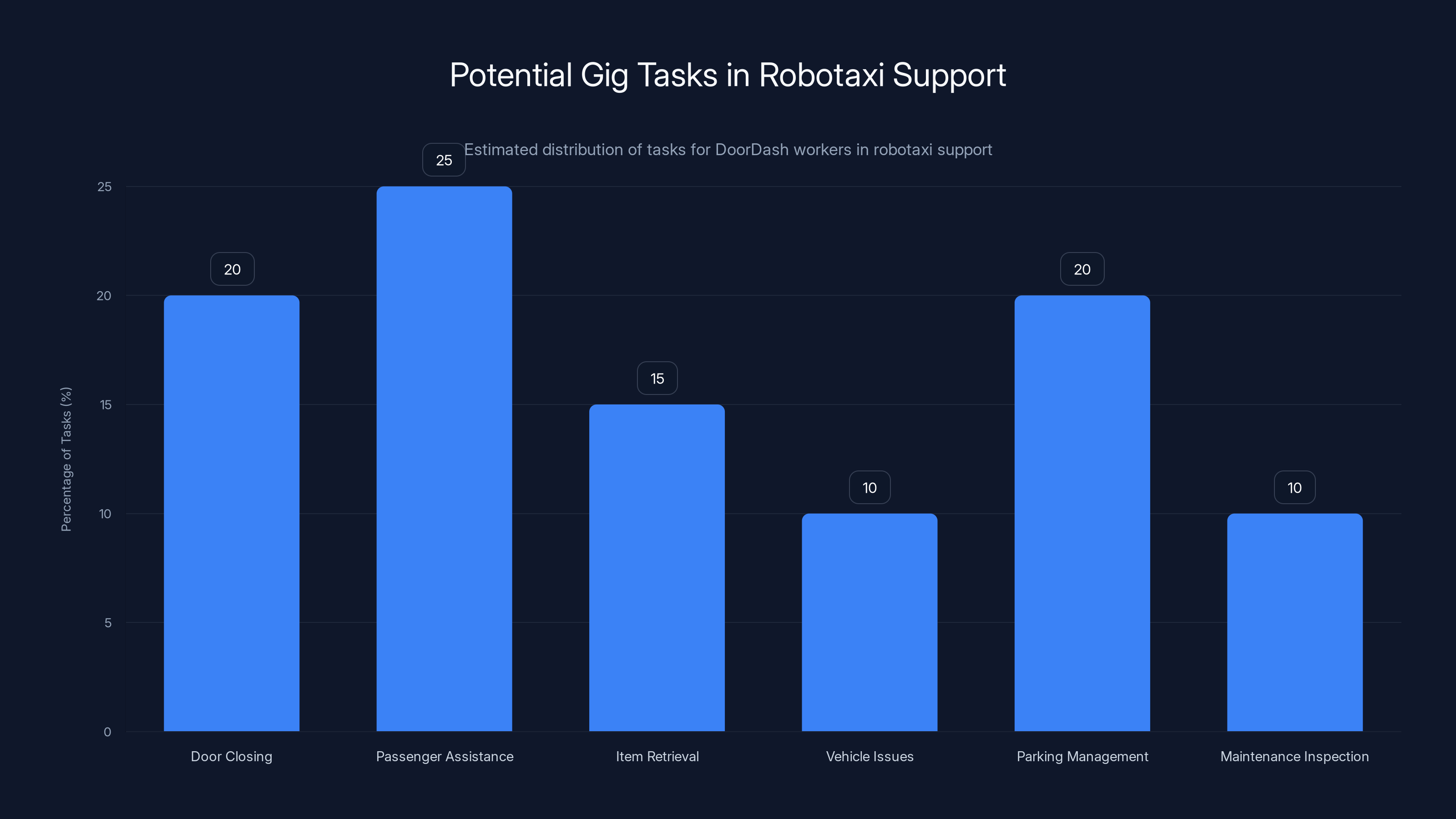

The implications are broader than just closing doors. This model could extend to other tasks that autonomous vehicles can't perform:

- Assisting elderly or disabled passengers who need help

- Retrieving items left in vehicles

- Assisting with vehicle issues that require judgment

- Managing vehicle parking in situations where autonomous parking fails

- Inspecting vehicles for maintenance issues

All of these tasks could theoretically be handled by Waymo's own employees, but using the DoorDash network is more flexible and scales better. Waymo doesn't need to hire people full-time; they just pay for tasks as needed.

For DoorDash workers, this represents a diversification of potential income. A driver waiting between food delivery requests could pick up a quick $11.25 task to close a door. The task takes maybe five minutes, including walking to the vehicle. That's higher per-minute pay than most food delivery.

But there's an underlying truth here that's less glossy: this is gig work replacing better jobs. Waymo used to have to employ service technicians to handle various vehicle issues. Now some of that work is being distributed to gig workers making $11.25 per task. It's more flexible, cheaper for Waymo, but also less stable for workers.

This is the uncomfortable reality of the robotaxi future. Autonomous vehicles aren't replacing all jobs. They're creating new types of jobs, but often at worse pay and conditions than the jobs they displace. And those new jobs themselves might eventually be automated away once the economics make sense.

Solving Edge Cases: The Real Challenge of Autonomous Vehicles

The door-closing problem is just one example of what's called the "last mile problem" in autonomous vehicles. The last mile—or more accurately, the last 1% of edge cases—is where most of the engineering effort actually goes.

Waymo's vehicles can handle 99% of driving situations better than humans. They navigate complex intersections. They respond to traffic signals. They detect pedestrians and cyclists. They adjust for weather conditions. They make reasonable decisions in most scenarios.

But that final 1% of edge cases is enormous. It includes:

- Ambiguous traffic situations where it's not clear what the legal action is

- Vehicle malfunctions that require human diagnosis

- Passenger behavior issues where someone is sick, aggressive, or having an emergency

- Environmental factors that confuse sensors (extreme weather, unusual lighting)

- Traffic conditions caused by accidents, protests, or unusual events

- Interactions with special vehicles (emergency vehicles, construction equipment)

- Parking situations that don't match any training scenario

- Physical interference (doors left open, objects blocking wheels)

- System ambiguities where the AI can't confidently choose between options

- Novel situations that have never been encountered in training data

Each of these requires human judgment. You can't write an algorithm that covers all of them because you can't predict all possible scenarios. That's why all autonomous vehicle companies have remote human operators who can take over vehicles when needed.

Waymo isn't publicly disclosing how often remote operators need to intervene, but industry estimates suggest that current autonomous vehicles require human intervention in somewhere between 0.1% and 1% of rides, depending on conditions and location.

The door problem sits at this intersection of edge cases and service issues. It's not a safety threat, but it's an operational blocker. A door left open prevents the vehicle from moving, which disrupts the service. And because it's a service issue rather than a safety issue, the economically rational solution is to use humans for the quick fix rather than engineer a perfect automated solution.

Waymo's approach is actually more scalable than you might think. As the fleet grows from hundreds to thousands to hundreds of thousands of vehicles, having a small percentage requiring human intervention becomes manageable. If 0.5% of your vehicles need intervention at any given time, and you have 100,000 vehicles deployed, you'd need remote operators or on-site workers to handle 500 vehicles simultaneously.

Using the DoorDash network scales this better than any internal operation could. Waymo doesn't need to hire 500 full-time employees. It just needs to offer enough work through the DoorDash platform that workers are willing to take tasks. The supply and demand balance themselves.

Waymo robotaxis have a lower accident rate compared to human-driven vehicles, demonstrating superior safety performance (Estimated data).

Real-World Robotaxi Operations: What Actually Happens When Vehicles Hit the Street

Theory is one thing. Actually operating robotaxis in real cities is something else entirely.

Waymo has been operating in Phoenix for over a year now. The company has published limited data about their operational experience, but some insights have emerged through accident reports, news coverage, and worker anecdotes.

First, the safety record is genuinely impressive. Waymo vehicles have been in fewer accidents (adjusted for miles driven) than human-driven vehicles. The insurance data backs this up. The vehicles don't get road rage. They don't drive drunk. They follow traffic laws. From a pure safety perspective, they're demonstrably better than human drivers.

Second, the operational challenges are different from safety challenges. While Waymo's vehicles are safe, they sometimes fail to accomplish their mission because of edge cases. A vehicle might refuse to proceed through an intersection because the AI isn't confident in the traffic situation. A vehicle might get stuck in a parking lot because the available spaces don't match any trained scenario. A vehicle might request human intervention because something is ambiguous.

These operational challenges don't show up in safety statistics. They show up in reliability metrics, customer satisfaction, and operational costs.

Third, the regulatory and social environment matters more than the technology sometimes. San Francisco and Los Angeles have specific regulations about how autonomous vehicles can operate. Different cities have different rules about autonomous taxi services. Some cities have been hostile to the technology. Others are supportive. The political environment can change quickly—a single accident, even a minor one, can trigger backlash that slows regulatory approval.

Waymo has been careful about public relations, limiting service to geographies where they have good regulatory standing and working closely with local authorities. This caution might seem like it's slowing deployment, but it's actually risk management. Rapid expansion into hostile regulatory environments would be disastrous.

The door problem is part of this operational reality. It's not a critical failure, but it's a failure nonetheless. A passenger can't reliably use the service if there's any chance the door won't open properly or will get stuck. Solving this—either through hardware improvements (the Ojai with motorized sliding doors) or operational procedures (the DoorDash integration) is essential for scaling.

What This Means for the Autonomous Vehicle Timeline

One of the most controversial aspects of autonomous vehicle development has been timeline predictions. For decades, experts have predicted that fully autonomous vehicles were "five years away." Every few years, the timeline resets. It's always five years away.

The door problem, and the DoorDash solution, offers insight into why timelines keep extending. It's not that autonomous vehicle technology isn't advancing. It is. Waymo's vehicles are genuinely impressive pieces of engineering. The issue is that moving from "works well on a supervised route in good weather" to "reliable service in any city, any weather, any time, any situation" involves solving thousands of edge cases.

Each edge case seems small. Doors left open. Parking lot confusion. Ambiguous traffic signals. But each one requires either engineering effort or operational workarounds. The cumulative effect is that scaling from pilot programs to truly ubiquitous service takes longer than people expect.

Waymo's timeline is now: Phoenix (operational), San Francisco and Los Angeles (expanding), a dozen more U.S. cities (coming soon), London (coming soon). That's faster expansion than it was five years ago. But it's still conservative, measured, and focused on geographies where regulatory and operational conditions are favorable.

Full autonomy—a fleet of vehicles that requires zero human intervention for any reason—might be decades away, or it might never happen. Instead, what we're likely to see is persistent human-in-the-loop autonomy: AI systems that handle the vast majority of tasks and human workers who handle the edge cases.

This isn't a failure of the technology. It's the realistic endpoint where the economics favor human-plus-robot solutions over pure robots.

For passengers and consumers, this matters because it means autonomous vehicles aren't going to suddenly appear everywhere and replace all taxis overnight. Instead, they'll gradually expand to more cities, more times of day, and more conditions as Waymo solves edge cases and demonstrates reliability.

For labor, this matters because it means autonomous vehicles aren't going to eliminate jobs wholesale. Instead, they'll transform jobs. Taxi drivers might become support workers for autonomous fleets. Delivery drivers might pick up tasks like closing doors on robotaxis. The job market will shift, but it won't disappear.

Estimated data suggests that workers receive

The Economics of Hybrid Human-Robot Systems

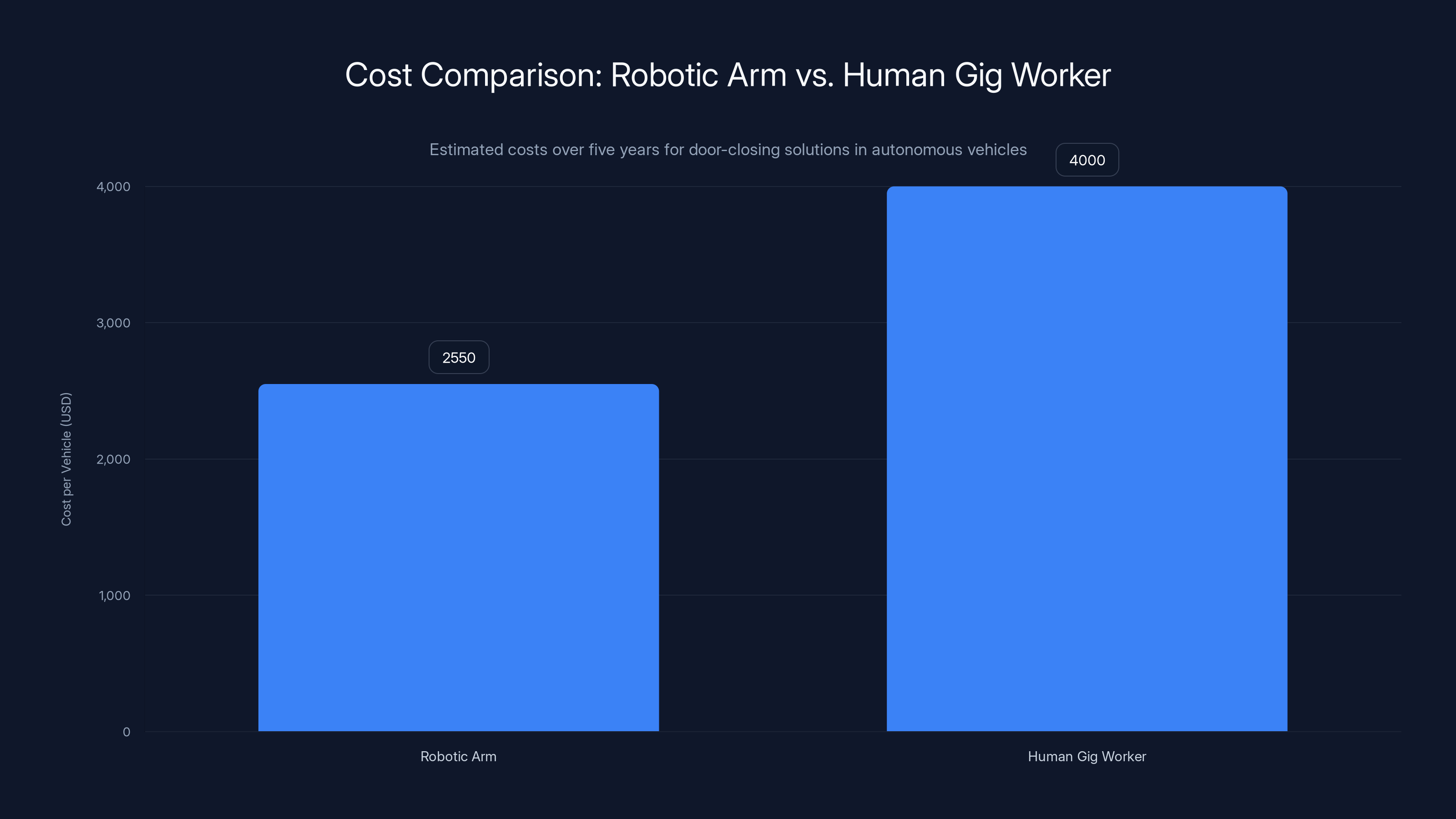

Why doesn't Waymo just build a robotic arm to close doors? Or engineer a door mechanism that can't fail? The answer is economics.

Adding a robotic arm to every vehicle increases manufacturing cost, complexity, and failure modes. Robotic arms are expensive. They require maintenance. They have failure rates. You'd need to engineer integration with the vehicle's power and control systems. You'd need failsafes. You'd need testing. You'd need backup systems in case the arm breaks.

Estimate: $2,000-5,000 additional cost per vehicle, plus ongoing maintenance costs.

Pay a gig worker $11.25 to close a door maybe once every thousand rides.

The math is straightforward. If a vehicle completes 30 rides per day, and doors get left open in 0.1% of rides, that's about one door-closing incident per 334 days. Over a year, that's about one incident per vehicle. Cost: $11.25.

So the choice is:

- Option A: Add 50/year maintenance = $2,550 per vehicle over five years

- Option B: Pay 4,000 per vehicle

Actually, if you're Waymo with thousands of vehicles, and some vehicles have more incidents than others (maybe some passengers are more forgetful), the average might be higher. But it's still cheaper than building robotics into every vehicle.

This is the economic reality of the autonomous vehicle market. Waymo isn't trying to build the perfect vehicle. It's trying to build a vehicle system that works well enough, often enough, cheaply enough to be commercially viable.

The same economic logic applies to other edge cases. A remote human operator can handle ambiguous traffic situations, vehicle malfunctions, and passenger emergencies remotely, without needing expensive on-board robotics or more sophisticated AI.

This creates a weird inversion of expectations. People think automation means removing all humans. But actually, optimal automation often means inserting humans at specific points where human judgment or presence is cheaper than engineering perfection.

It's like airline operations. Planes are incredibly automated. Modern aircraft can take off, fly, and land with minimal human input. But airlines still require pilots in every plane, costing them hundreds of thousands of dollars per aircraft. Why? Because a pilot is cheaper insurance against the unexpected than engineering every possible contingency into the aircraft.

Waymo is learning the same lesson. Autonomous vehicles are remarkably capable, but they benefit from human oversight and intervention for edge cases.

How Passenger Behavior Creates Autonomous Vehicle Challenges

The door problem is fundamentally a passenger behavior problem. Humans are forgetful, distracted, and sometimes deliberately inconsiderate. Autonomous vehicle systems can't account for all human behavior.

This is one of the hardest challenges in autonomous vehicle design: the interface between human users and autonomous systems.

Consider the variety of ways passengers interact with Waymo vehicles:

- Some passengers carefully follow all instructions and close doors gently

- Some passengers are rushed and don't fully close doors

- Some passengers don't understand the vehicle's interface

- Some passengers are elderly and have mobility limitations

- Some passengers are intoxicated or impaired

- Some passengers are intentionally difficult

- Some passengers have medical emergencies

- Some passengers have language barriers

A human taxi driver adapts to all these variations instinctively. They might remind a distracted passenger to close their door. They might assist an elderly passenger. They might recognize someone who's having an emergency and call for help.

An autonomous vehicle can't do any of this. It can detect that a door is open. It can play a recorded message reminding people to close doors. But it can't physically intervene if the passenger doesn't comply.

Waymo has experimented with different approaches:

- Automatic door closing: Motorized doors that close themselves (solved in the new Ojai)

- Warnings and reminders: Audio and visual cues that remind passengers

- Lock-down procedures: Refusing to move until doors are closed (which is what's happening now)

- Manual intervention: Using human workers (the DoorDash solution)

Each approach has trade-offs. Automatic doors are more expensive but more reliable. Warnings might be ignored. Lock-down procedures create delays and frustration. Manual intervention is flexible but costly.

This is why the Ojai's motorized sliding doors are important. They're not just an engineering improvement. They're an attempt to solve the passenger behavior problem by making the correct behavior (fully closed doors) automatic rather than requiring manual compliance.

Estimated data suggests that passenger assistance and door closing are the most common tasks for DoorDash workers in robotaxi support, highlighting the evolving role of gig workers in the automation era.

Comparing Waymo's Approach with Competitors

Waymo isn't the only company deploying autonomous vehicles. Cruise (backed by General Motors), Aurora, and Chinese companies like Pony.ai and WeRide are also developing robotaxi services.

Waymo's advantage is that it's the furthest along. They're actually operating commercially, actually making money, and actually dealing with real-world problems. Their competitors are still mostly in trial phases.

Cruise was operating in San Francisco but hit a setback after a collision incident and scaled back operations. This is instructive because it shows how quickly regulatory and public sentiment can shift. One incident, even a minor one, can trigger backlash that slows expansion.

Waymo's caution in expansion—focusing on Phoenix, San Francisco, and Los Angeles before expanding to new cities—is risk management. By establishing a strong track record in these cities, Waymo builds credibility and political support that makes expansion to new cities easier.

Uber and Lyft aren't seriously developing autonomous vehicles anymore, which is remarkable given that autonomous vehicles are supposed to be the future of ride-hailing. Why? Probably because the engineering is harder than expected, the regulatory environment is uncertain, and the near-term business case doesn't justify the R&D spending. Waymo has Google's (well, Alphabet's) resources to sustain long-term R&D without needing near-term profitability. Ride-hailing companies don't have that luxury.

Tesla makes claims about full self-driving, but Tesla's approach is very different from Waymo's. Tesla is attempting to build autonomy into consumer vehicles, using data from millions of consumer cars. Waymo is building purpose-designed robotaxis with extensive sensor arrays. The Tesla approach might eventually scale better, or it might fail because consumer cars don't have the sensors needed. It's still too early to say.

The international landscape is also important. Chinese autonomous vehicle companies have less regulatory friction and are willing to deploy at scale more quickly. Companies like Baidu and WeRide are operating robotaxi services in Chinese cities with thousands of vehicles. They might leapfrog Western companies in scale, even if the technology isn't quite as mature.

Waymo's London expansion is interesting because it signals intention to compete globally. Autonomous vehicle deployment in London requires navigating UK regulations, right-hand traffic, and different driving cultures. It's a challenging expansion that shows confidence in the technology's maturity.

The Sixth-Generation Driver and Hardware Evolution

The shift from the Jaguar I-PACE to the Zeekr Ojai represents a major evolution in Waymo's hardware approach. Understanding this shift is key to understanding where the technology is heading.

The I-PACE was a compromise vehicle. Jaguar designed it as a premium electric vehicle for consumers. Waymo modified it for autonomous operation. It works, but it's suboptimal in various ways. The doors are one example: traditional hinged doors require precise mechanical operation and can get stuck.

The Ojai is purpose-built for autonomous operation. It's a minivan with:

- Motorized sliding doors that are easier to automate

- A spacious interior optimized for autonomous taxi use, not consumer commuting

- Better sensor mounts designed for Waymo's sensor suite from the beginning

- Optimized weight distribution for autonomous operation characteristics

- Designed-in redundancy for safety-critical systems

Waymo's sixth-generation driver includes:

This means better environmental sensing, especially at night and in poor weather—two conditions where the previous generation struggled.

The Ojai isn't just an incremental improvement. It signals that Waymo has moved beyond "retrofit autonomy onto existing vehicles" and is now saying "design vehicles specifically for autonomous operation." This is a more mature approach that should result in more reliable vehicles.

Implications for the Future of Work

The DoorDash integration reveals something important about how automation is actually shaping labor markets: it's not destroying all jobs, but it's creating new types of jobs and destroying old ones.

Taxi drivers have been declining as a profession since Uber and Lyft disrupted the market. Autonomous vehicles will continue this trend. But Waymo needs workers for:

- Remote operation of vehicles in edge cases

- Closing doors and handling physical issues

- Maintenance and cleaning

- Customer support

- Safety monitoring

These are different jobs from traditional taxi driving, and they typically pay less. A gig worker making

But here's what's important: these gig roles also have flexibility that traditional taxi driving didn't have. A DoorDash driver can pick up door-closing tasks between food deliveries. Someone looking for occasional income can take a few tasks per week. This creates a labor market that's more fragmented but also more accessible to people who can't commit to full-time work.

From a labor perspective, the Waymo-DoorDash arrangement is telling because it shows that even the robotaxi companies think human involvement will be necessary for a long time. If they believed full autonomy was imminent, they wouldn't be building out these human support systems.

The Regulatory and Legal Implications

Autonomous vehicles operate in a regulatory environment that varies by jurisdiction, and this creates complications for scaling.

Waymo operates under California regulations for San Francisco and Los Angeles, Arizona regulations for Phoenix, and various other state rules. Each jurisdiction has different requirements for autonomous vehicle testing, commercial operation, data reporting, and insurance liability.

When Waymo has to use humans to close doors, a question emerges: is the DoorDash worker acting as an employee of Waymo, making Waymo liable for injuries? Or are they an independent contractor, with DoorDash responsible? The legal status matters for liability and insurance purposes.

Regulators are still figuring this out. There's no established legal framework for "humans supporting autonomous vehicles." Is a DoorDash worker maintaining a vehicle? Repairing it? Providing a service? Each classification has different legal implications.

Liability is the biggest question. If a DoorDash worker gets injured closing a door, who's liable? If they damage the vehicle, who pays? If they close a door incorrectly and the vehicle subsequently has an accident, is DoorDash or Waymo responsible?

These questions will likely need to be resolved through litigation and regulatory guidance. For now, companies like Waymo and DoorDash are probably operating under ambiguous legal terms, relying on their platforms' terms of service and insurance policies to allocate liability.

Psychological and Cultural Perspectives

There's also a psychological dimension to the DoorDash-Waymo arrangement that's worth considering.

From a consumer perspective, ordering a robotaxi and having it work perfectly is the dream scenario. But if the experience involves waiting for a human to come close a door, the illusion of full automation breaks down. Consumers are reminded that humans are still required.

This might not matter for the long-term viability of the service, but it affects perception. People have been promised fully autonomous vehicles for so long that anything less feels like a compromise or failure.

From a philosophical perspective, the Waymo-DoorDash arrangement raises questions about what "autonomous" actually means. Is a vehicle truly autonomous if it requires human intervention for specific tasks? Or is it just "highly automated with human backup"?

This matters because it affects how people evaluate the technology and whether it meets their expectations. If people expect full autonomy and get 99% autonomy with human backup for 1%, they might see it as a failure even if it's actually quite impressive.

The Scaling Challenge: From Pilot Programs to Ubiquity

Waymo operating in six cities is impressive, but it's still a pilot program at massive scale. True ubiquity would mean autonomous vehicles in every city, available 24/7, handling every possible traffic condition.

The scaling challenge is geometric. As Waymo expands to new cities, they encounter new edge cases. San Francisco driving is different from Phoenix driving. Los Angeles driving is different from Chicago driving. Weather, traffic patterns, pedestrian behavior, regulatory environment—everything varies.

Each new city likely requires weeks or months of additional testing and calibration. For every city Waymo enters, they probably double or triple their edge case catalog. Eventually, they might have enough data to deploy to new cities more quickly, but we're probably years away from that.

The human support model actually helps with this. Humans can handle novel edge cases that the AI hasn't seen before. Remote human operators can get experience with novel situations in new cities, while the AI gradually learns. This hybrid approach might actually be faster than trying to achieve full autonomy before expanding.

Waymo's expansion timeline—six cities now, a dozen more "coming soon," London "coming soon"—suggests the company believes they can scale faster than competitors. But "soon" in autonomous vehicle timelines means somewhere between one and five years. It's not overnight.

Learning from the Door Problem: Lessons for Other Industries

The Waymo-DoorDash arrangement isn't just about robotaxis. It's a template that could apply to other automation scenarios.

Whenever you deploy autonomous systems in the real world, you encounter edge cases that the system can't handle. These include:

Logistics and Delivery

Robotic delivery vehicles can navigate streets but struggle with stairs, locked gates, and communication with recipients. Human support for these scenarios makes systems more capable without requiring perfect automation.

Manufacturing

Robotic assembly lines handle standard operations but struggle with novel products, design changes, or unexpected equipment issues. Humans in the loop are standard practice.

Customer Service

Chatbots handle standard inquiries but struggle with complex or unusual requests. Escalation to human agents is expected.

Medical Diagnostics

AI can screen imaging for common conditions but struggles with rare conditions or ambiguous cases. Human radiologists review borderline cases.

In every domain, the pattern is similar: AI handles the common cases well, humans handle the edge cases, and the combination is more capable than either alone.

Waymo isn't acknowledging this explicitly, but the DoorDash arrangement is an implicit acceptance of this pattern. The robotaxi industry will mature to the extent that it embraces hybrid human-AI operations rather than trying to achieve perfect autonomy.

The Path Forward: What's Next for Waymo

Waymo's roadmap includes several major milestones:

- Continued expansion to the dozen-plus cities already announced

- Ojai rollout making motorized doors standard across the fleet

- Operating cost reduction as fleet size increases and operational efficiency improves

- Overnight service expanding from daytime-only to 24/7 operation

- Weather capability improving performance in rain, snow, and heavy fog

- International growth with the London expansion and potentially other markets

Each milestone will be complicated by edge cases and unexpected operational challenges. But Waymo's track record suggests they're willing to be pragmatic. If human support improves the service, they'll use it. If motorized doors solve design problems better than software can, they'll implement them.

The company's strategy isn't to prove that robots can replace all humans. It's to prove that autonomous vehicles can operate safely and reliably at a commercial scale, even if that requires human support for edge cases.

From a business perspective, this is actually a strong strategy. It allows Waymo to deploy faster, scale more reliably, and improve profitability without needing to wait for perfect autonomy technology that might never arrive.

Conclusion: The Uncomfortable Reality of Automation

The image of a DoorDash worker showing up to close a Waymo door is uncomfortable to many people. It seems to undermine the promise of autonomous vehicles. It suggests that the technology isn't as mature as promised. It reveals that robots still need humans.

But this might actually be the future of automation, not a failure case. Perfect automation—systems that require zero human intervention—might not be economically optimal or achievable. Instead, the future might be pragmatic automation: systems that use technology for what it does well and humans for what humans do well.

Waymo has deployed robotaxis in six cities. They're profitable or approaching profitability. They have good safety records. They're expanding to a dozen more cities. By any realistic measure, autonomous vehicles are working, even if they're not perfect.

The door-closing problem is a humbling reminder that engineering sophistication isn't enough. Real-world systems need to handle the messy reality of human behavior, unexpected situations, and edge cases that you can't predict. Waymo's solution—using human workers to close doors—is pragmatic, scalable, and probably better than waiting for perfect autonomous door-closing technology.

As autonomous vehicles mature and expand, we'll see more of these hybrid human-robot arrangements. Maybe other gig platforms will integrate with autonomous vehicle fleets. Maybe autonomous vehicle companies will develop their own labor marketplaces. Maybe entire industries will emerge around supporting autonomous systems.

The robotaxi of the future probably won't be fully autonomous. It will be highly autonomous, with human support available for edge cases. And that's not a failure of the technology. It's the realistic endpoint where engineering meets economics and pragmatism wins out over perfection.

For consumers, this means robotaxis are coming sooner than you might think, even if they're not as magical as the hype suggested. For workers, it means new opportunities and challenges as the labor market adapts to hybrid human-robot systems. For companies like Waymo, it means a clearer path to profitability and global expansion.

The door is open. A human needs to close it. And that's probably fine.

FAQ

What happens if a passenger leaves a Waymo door open?

Waymo's vehicle AI detects the open door and is unable to proceed. The vehicle sends a notification through its fleet management system. If the Waymo-DoorDash pilot is active in that area, nearby DoorDash workers are notified and can accept a task to close the door for $11.25, allowing the vehicle to resume operation.

Why can't Waymo vehicles close their own doors?

Waymo's current fleet, primarily consisting of modified Jaguar I-PACE vehicles, uses traditional hinged doors that require powered door closers. While the technology could include robotic door-closing mechanisms, the economics favor using human workers for the rare occurrences of this problem rather than adding expensive hardware and maintenance to every vehicle. This changes with the new Ojai minivans, which feature motorized sliding doors that can be automatically closed.

How often do passengers actually leave Waymo doors open?

Waymo and DoorDash haven't disclosed specific incident rates, but the existence of a formalized notification system and payment structure suggests it's common enough to justify dedicated infrastructure. With hundreds of thousands of daily rides, even a 0.1% incident rate would result in hundreds of door-closing incidents per week.

Is the Waymo-DoorDash arrangement permanent?

Both companies describe this as a pilot program, suggesting it may be temporary or location-specific. Once the Zeekr Ojai minivans with motorized sliding doors become the primary vehicle in Waymo's fleet, the door-closing problem should largely disappear, making the DoorDash integration unnecessary.

Will autonomous vehicles create new jobs or just eliminate existing ones?

Autonomous vehicles will likely transform the job market rather than eliminate all jobs. Traditional taxi driving will decline, but new roles will emerge: remote vehicle operators, maintenance workers, customer support specialists, and gig workers for specific support tasks. However, these new roles typically pay less than the jobs they replace, representing a shift in labor market composition rather than net job creation.

How does Waymo's approach compare to Tesla's autonomous vehicle strategy?

Waymo builds purpose-designed robotaxis with extensive sensor arrays for commercial deployment. Tesla adds autonomy features to consumer vehicles using data from millions of cars. Waymo's approach gives more control and optimization but is slower to scale. Tesla's approach scales faster but might struggle with complex urban environments. Both approaches have merit, and the winner will likely depend on regulatory adoption and technological breakthroughs.

What does the Zeekr Ojai represent for Waymo's future?

The Ojai represents a shift from retrofitting autonomy onto existing vehicle designs to building vehicles specifically for autonomous operation. This purpose-built approach allows solving problems like door closing through better hardware design rather than software workarounds. The Ojai signals that Waymo believes it has sufficient technical maturity to justify developing new vehicle platforms, a sign of confidence in the technology.

Are there other edge cases autonomous vehicles can't handle?

Yes, many. Autonomous vehicles struggle with ambiguous traffic situations, passenger emergencies, novel parking scenarios, debris in the road, communication with construction workers, and countless edge cases that humans navigate intuitively. As fleets scale, Waymo will likely develop additional human support systems for these scenarios, similar to the door-closing solution.

Key Takeaways

- Waymo's deployment of DoorDash workers to close doors reveals that perfectly autonomous vehicles require human support for edge cases

- The economics of automation favor using humans for rare incidents ($11.25 per task) rather than engineering expensive hardware solutions for every vehicle

- Motorized sliding doors in the new Zeekr Ojai minivan represent a shift from retrofitting autonomy onto existing vehicles to designing vehicles for autonomous operation

- Autonomous vehicles aren't eliminating all jobs; they're creating new types of work while destroying traditional ones, transforming rather than eliminating the labor market

- The door-closing problem is symptomatic of a larger challenge: the 1% of edge cases that require human judgment, preventing truly perfect autonomous operation

Related Articles

- Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors [2025]

- Waymo's Sixth-Generation Robotaxi: The Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- Waymo's DC Robotaxi Campaign: How AI Companies Are Reshaping City Regulation [2025]

- Waymo's Nashville Robotaxis: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- RentAHuman Review: The Reality of AI Gig Work in 2025

![Robotaxis Meet Gig Economy: How Waymo Uses DoorDash to Close Doors [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/robotaxis-meet-gig-economy-how-waymo-uses-doordash-to-close-/image-1-1770999353120.jpg)