Open AI Loses Major Trademark Battle Over Cameo Naming Rights

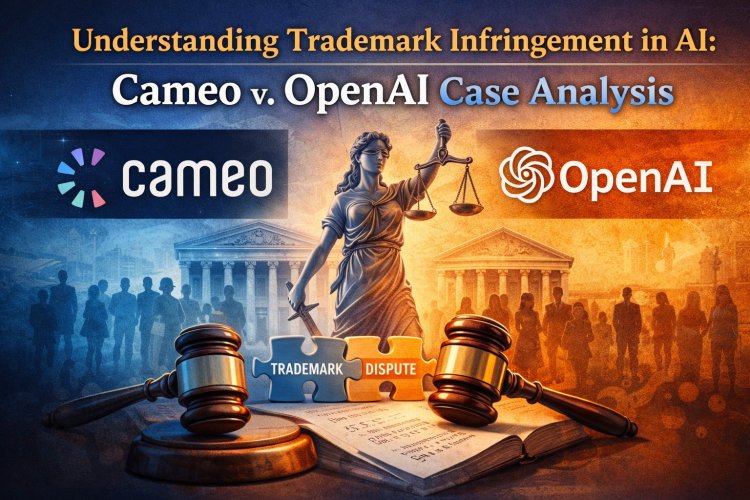

Imagine building a feature you're genuinely proud of, only to get a cease-and-desist letter because the name you chose already belongs to someone else. That's exactly what happened to Open AI when it named a video generation feature in Sora "Cameo." The problem? A celebrity video platform called Cameo had already trademarked the name and spent nearly a decade building brand recognition around it. In February 2025, a federal court in Northern California sided with Cameo, ordering Open AI to stop using the name. This isn't just a naming hiccup. It's a watershed moment for how AI companies approach intellectual property, brand protection, and the risks of moving fast without checking what's already out there.

The ruling reveals something uncomfortable about Silicon Valley's speed-first mentality. Open AI, one of the world's most valuable AI companies, apparently didn't conduct a thorough trademark search before launching a feature with the Cameo name. Or maybe they did and decided the risk was worth it. Either way, the court disagreed. Federal Judge Beth Labson Freeman ruled that "Cameo" was sufficiently similar to Cameo's existing trademark that it created a "likelihood of confusion" among consumers. This wasn't a gray area. This was a clear infringement.

What makes this case particularly interesting isn't just that Open AI lost. It's that the company argued its use of "Cameo" was merely descriptive, suggesting the feature allowed you to appear in videos like a cameo actor in a film. The court rejected this argument outright, finding that the name "suggests rather than describes the feature." Translation: you can't just claim anything is generic when it clearly isn't. The ruling sent a shock through the tech industry because it established that AI companies don't get special exemptions from trademark law, no matter how revolutionary their technology.

Open AI's response was telling. Rather than fight further, the company quickly rebranded the feature to "Characters." This was damage control, but it also raised uncomfortable questions about how thoroughly the company vets product names before launch. For a company valued at over $100 billion, the fact that it didn't catch a potential trademark conflict before rolling out a feature publicly suggests either overconfidence, understaffing in IP review, or a deliberate calculation that the legal risk was acceptable.

The Cameo Platform and Its Brand Identity

Cameo isn't a tech darling in the conventional sense. It's a platform that lets fans book personalized video messages from celebrities for $50 to several hundred dollars depending on the celebrity's status. Think of it as an intermediary that solved a real problem: celebrities couldn't handle thousands of individual video requests, but fans wanted personalized content. Cameo became the marketplace where this exchange happened efficiently.

The platform launched in 2017 and has grown to feature thousands of celebrities, from B-list actors to viral Tik Tok personalities. Cameo's CEO Steven Galanis built the business on a specific brand promise: creating "talent-friendly interactions" and "genuine connection." The word "Cameo" itself became synonymous with personalized celebrity video messages in the cultural consciousness. When people wanted to book a celebrity shout-out, they said "I'm getting a Cameo." That's brand power.

By the time Open AI borrowed the Cameo name, Cameo had already spent nearly a decade building that recognition. The company had millions of transactions, thousands of creators earning money on the platform, and a brand that consumers trusted. Cameo had also invested significantly in protecting its intellectual property through trademark registration. The company owned the trademark "Cameo" in multiple jurisdictions for specific goods and services. When Open AI launched its feature, Cameo saw an immediate competitive and brand threat.

Cameo's legal strategy was aggressive but calculated. The company filed for a temporary restraining order in November 2024, and the court granted it. This meant Open AI had to stop using "Cameo" immediately, even while the broader case proceeded. The company renamed its feature to "Characters" as a workaround. But the damage was already done—Open AI had to invest engineering resources, product communication, and brand management to fix a problem that trademark research should have prevented.

What's particularly notable about Cameo as a plaintiff is that it's not a tech giant with unlimited legal resources. It's a venture-backed startup that had to fight for its intellectual property rights against one of the most powerful AI companies on Earth. The fact that Cameo won this battle despite facing a much larger opponent tells you something important: trademark law doesn't care how big you are or how revolutionary your AI is. If you infringe, you lose.

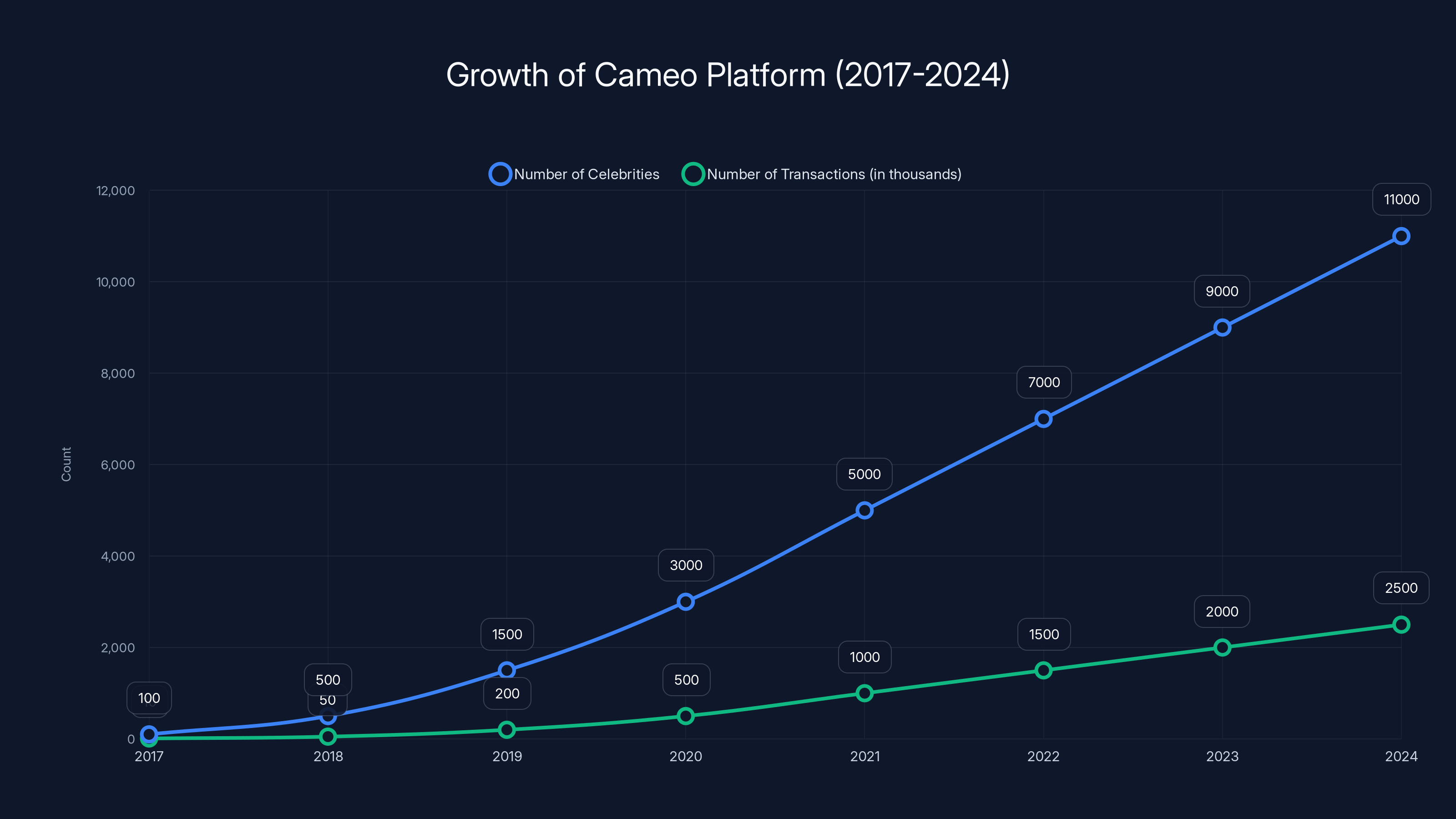

Cameo has seen significant growth in both the number of celebrities and transactions since its launch in 2017. Estimated data shows a steady increase, highlighting its expanding influence in personalized celebrity interactions.

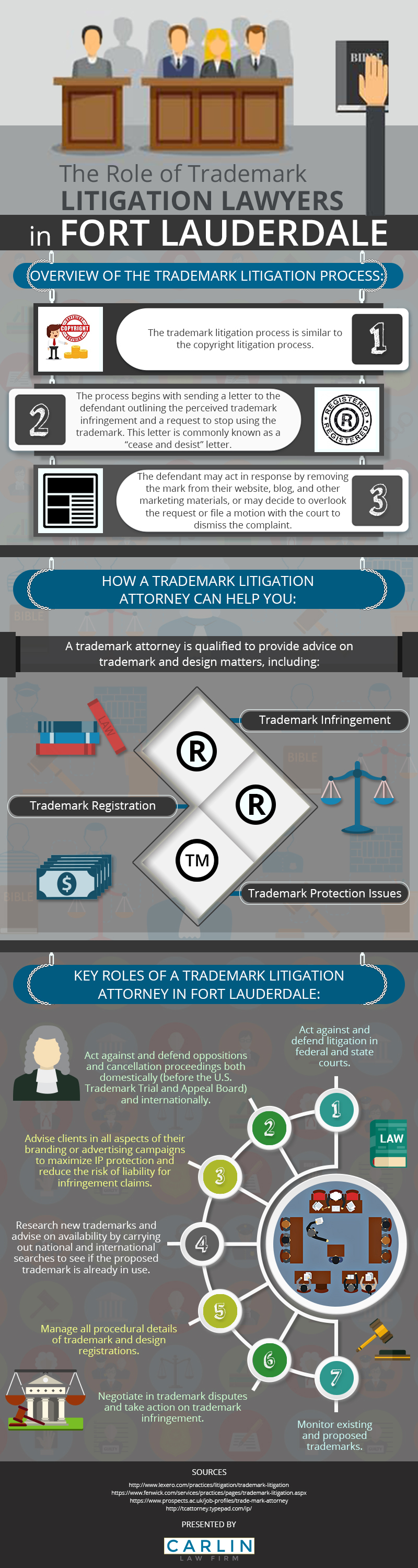

Understanding the Trademark Infringement Ruling

The federal court's decision wasn't ambiguous. Judge Beth Labson Freeman found that there was a "likelihood of confusion" between Open AI's use of "Cameo" and the existing Cameo trademark. This is the legal standard for trademark infringement. The court looks at several factors: the similarity of the marks, the similarity of the goods or services, the strength of the original mark, and the intent of the infringing party.

On similarity of marks, "Cameo" and "Cameo" are identical. Open AI wasn't even trying to modify the name. This made the court's job easy on this factor. On similarity of goods or services, both involve personalized video content. Cameo's service is personalized videos from celebrities. Open AI's feature lets you insert your likeness into AI-generated videos. These aren't identical services, but they're close enough in the video personalization space that confusion is plausible. A consumer could reasonably see "Cameo" in Sora and assume it's affiliated with or licensed from the Cameo platform.

On the strength of the original mark, Cameo had spent nine years building brand recognition. The company had millions of users, thousands of creators, significant media coverage, and clear consumer association with the Cameo name. This isn't a weak trademark. This is a strong one with substantial goodwill behind it. The court recognized this and weighted it heavily.

The most interesting part of the ruling involves Open AI's descriptive use argument. Open AI argued that "Cameo" merely describes the feature's function—inserting your likeness into videos, like a cameo appearance in film. The court rejected this. The opinion states that "Cameo" "suggests rather than describes the feature." In other words, the word choice was branding, not description. If Open AI had called the feature "Video Cameo Insert" or "Likeness Addition," the descriptive use argument might have held water. But naming it "Cameo" alone suggested an association with the existing Cameo platform, whether intentionally or not.

This distinction matters because descriptive marks get less protection. If Open AI had proven the word was purely descriptive, it might have had a defense. But a brand name that suggests rather than describes gets full trademark protection. The ruling effectively said that Open AI crossed the line from fair use into infringement by choosing a name that directly referenced the established brand.

One aspect the court didn't deeply explore is whether Open AI's users actually got confused. There's no evidence that people thought Open AI's Cameo feature was made by the Cameo platform. But trademark law doesn't require actual confusion. It only requires the likelihood of confusion. The court found that likelihood sufficient, even without evidence of real-world consumer confusion. This is an important distinction that affects how companies should approach trademark issues going forward.

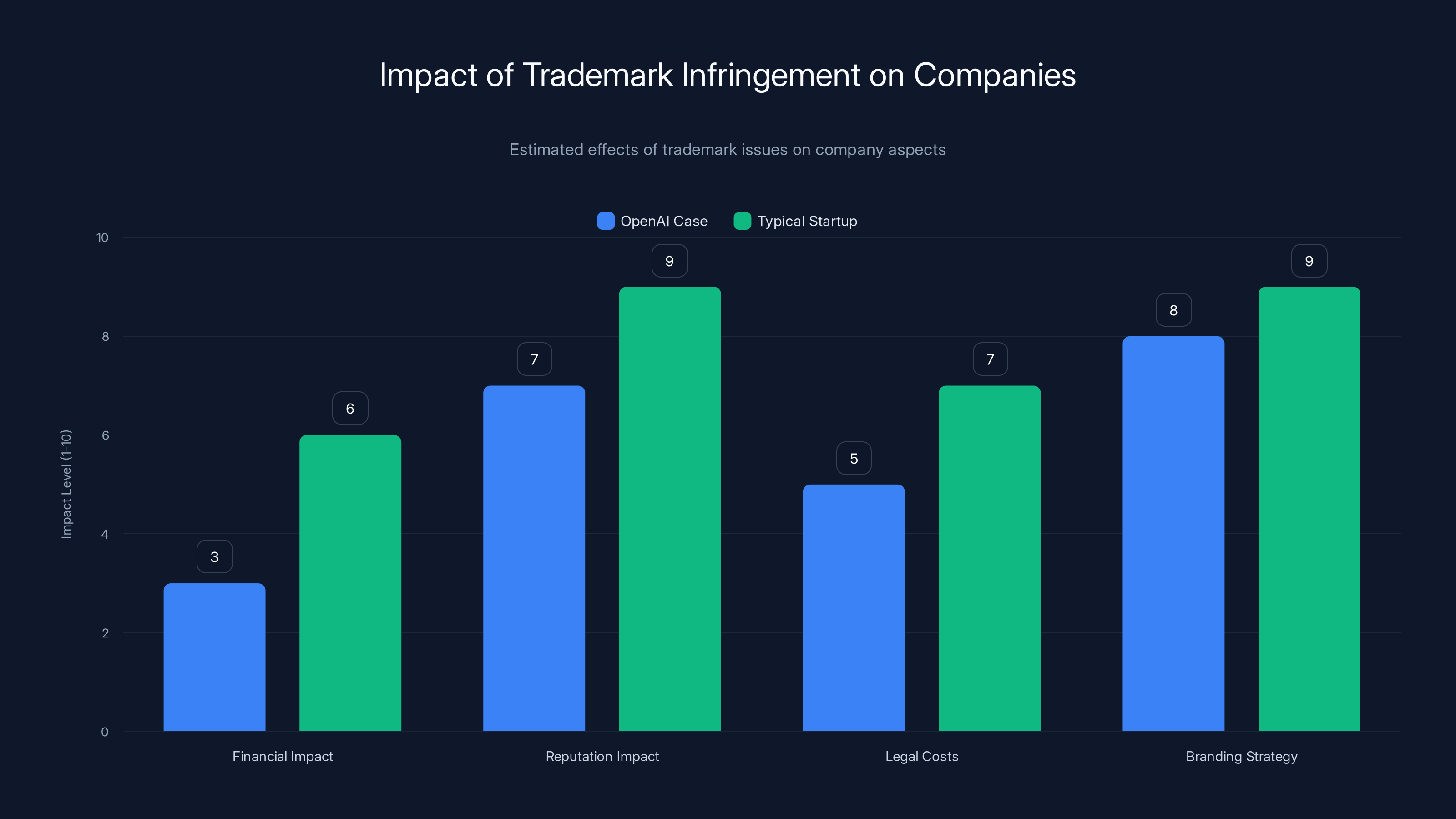

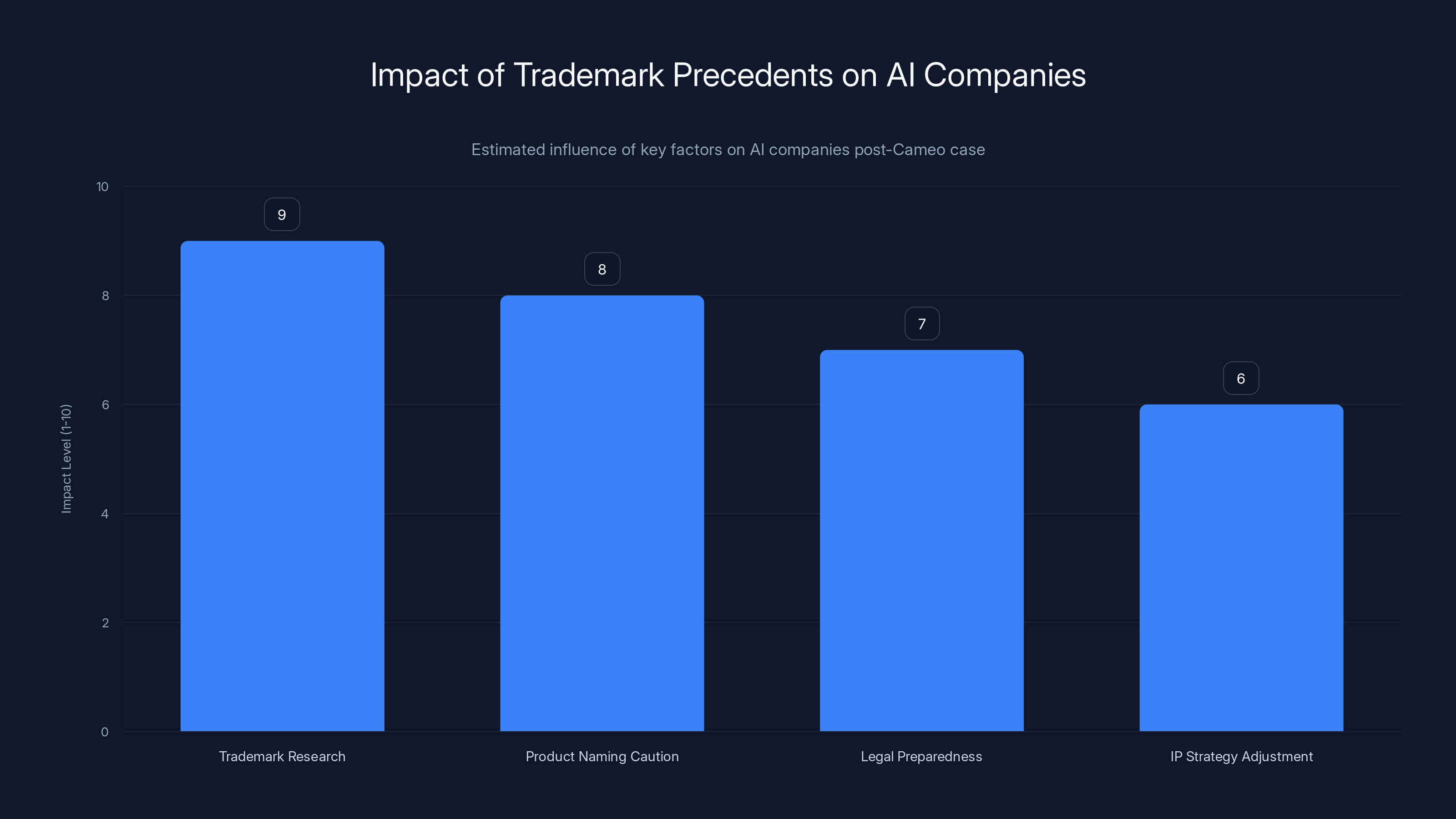

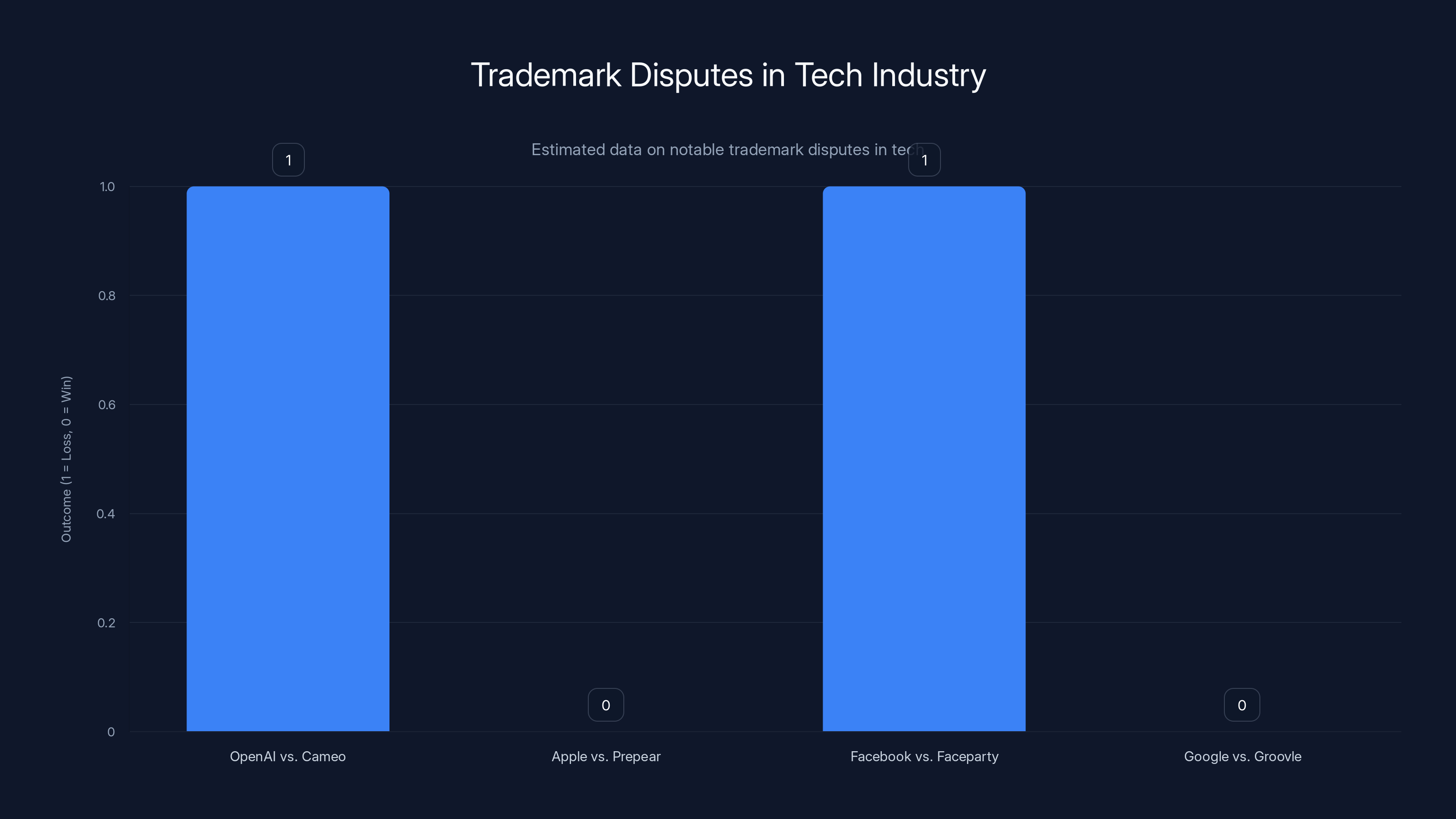

The OpenAI case highlights significant reputation impact and branding strategy adjustments due to trademark issues. Startups face higher financial and legal risks. Estimated data.

Open AI's IP Troubles: A Pattern Emerging

The Cameo case isn't Open AI's only intellectual property battle. In fact, it's part of a growing pattern of trademark and copyright conflicts that suggest the company might need to strengthen its IP review process. Just weeks before the Cameo ruling, Open AI ditched "IO" branding for its upcoming hardware products after facing legal challenges. According to documents obtained by Wired, the company had to walk back the IO naming in response to trademark conflicts.

Then there's the "Sora" situation. Over Drive, a digital library app, actually sued Open AI for using "Sora" as the name for its video generation product. Over Drive didn't win in the courts, but the lawsuit itself indicates that Open AI's naming conventions aren't always clearing the IP landscape before launch. This suggests either a gap in the company's trademark review process or a deliberate strategy of launching first and dealing with legal issues later.

Beyond trademark issues, Open AI is embroiled in multiple copyright disputes with artists, writers, and media organizations. The New York Times sued Open AI for training its language models on copyrighted material without permission. Authors including Sarah Silverman filed similar suits. These cases raise different legal issues than trademark infringement, but they all point to a company expanding rapidly without fully addressing the intellectual property implications of its actions.

The pattern suggests Open AI operates under a "move fast" philosophy where legal and IP review happens after launch, not before. This approach worked when Open AI was smaller and regulatory attention was lower. But as the company gets bigger and more prominent, IP conflicts become more costly and more damaging to reputation. Every trademark battle, every copyright lawsuit, every naming controversy chips away at Open AI's image as a thoughtful, responsible AI developer.

For other AI companies watching this unfold, the message is clear: thorough IP review upfront is cheaper and faster than legal battles after launch. The cost of conducting trademark searches, reviewing copyright implications, and vetting product names is trivial compared to the cost of rebranding, fighting lawsuits, and managing public relations fallout.

The Broader Implications for AI Product Development

The Cameo ruling has implications that extend far beyond Open AI. Every AI company developing new products and features needs to think carefully about how they name and brand their offerings. The court's decision establishes that AI companies don't get special treatment when it comes to trademark law. You can't just borrow a popular name because your technology is cutting-edge.

This creates practical challenges for AI product development. Many AI features are genuinely descriptive—you want the name to convey what the feature does. But the Cameo case shows that if an existing company has already trademarked similar descriptive language, you're in trouble. The solution is thorough research before naming anything. This means hiring IP professionals who understand both technology and trademark law, not treating IP review as an afterthought.

For startups building AI products, the lesson is even more critical. A well-funded startup like Open AI can absorb the cost of a rebranding exercise. But an early-stage AI startup built around a particular product name could face existential risk if it turns out the name is already taken. This argues for aggressive trademark research and clearance before investing in brand building around a particular product name.

The ruling also raises questions about the strength of trademark protection in rapidly evolving technology markets. Cameo's trademark is very specific to its service of connecting fans with celebrities for personalized videos. Open AI's feature was about inserting your likeness into AI videos. These aren't identical services. But they're similar enough in the video personalization space that the court found confusion likely. This creates an interesting tension: should trademark protection be broad enough to prevent any similar use of a name in adjacent fields, or should it be narrower and more specific to the exact market the trademark holder operates in?

The court sided with broader protection, which favors trademark holders over new companies trying to name their products. This could create challenges for innovation if trademark holders can essentially claim exclusive rights to broad categories of names. For example, if Cameo can prevent anyone from using "Cameo" for any video-related feature, does that mean future AI companies can't build features they'd naturally call "cameo" features? The ruling doesn't go that far, but it suggests the courts will protect established brand associations generously.

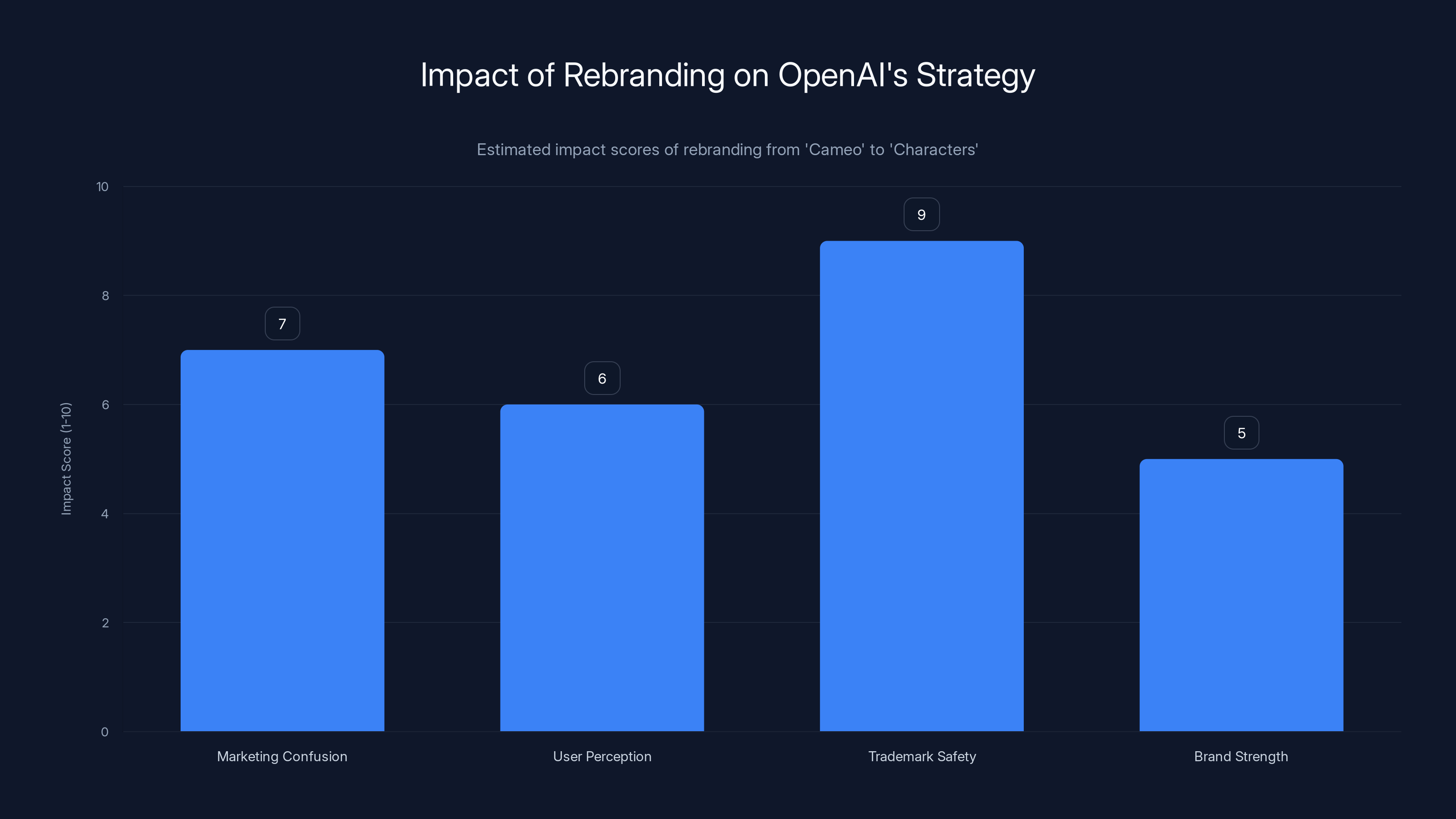

The rebranding to 'Characters' has mixed impacts: it increases trademark safety but causes marketing confusion and weakens brand strength. (Estimated data)

How AI Companies Should Approach Trademark Clearance

Learning from Open AI's mistake, any AI company should implement a rigorous trademark review process before launching new products or features. This isn't complicated, but it does require discipline and resources. The first step is to conduct a comprehensive trademark search. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office maintains a searchable database of registered trademarks. Before naming anything, search this database thoroughly. Look not just for exact matches but for similar marks, phonetic variations, and conceptually related terms.

The search should cover multiple jurisdictions if the product will be used internationally. Trademarks are territorial—a trademark registered in the U.S. doesn't automatically protect the holder in Europe or Asia. But if your product will eventually be used in those regions, you need to know what marks are already protected there. This is especially important for AI companies, which often launch globally or plan to expand globally quickly.

Second, consider working with trademark attorneys, especially for major product launches. A lawyer specializing in trademark law can conduct searches that go beyond simple database queries. They understand nuances of trademark law that non-specialists miss. They can identify potential conflicts that an engineer or product manager might overlook. This is a professional service, but it's considerably cheaper than fighting a trademark infringement lawsuit or rebranding a launched product.

Third, be cautious with names that could have double meanings or secondary associations. "Cameo" seemed like a reasonable name for a feature that inserts you into videos, but it's also the established brand for a specific platform. If a name could reasonably be associated with an existing company or product, be skeptical. Look for alternatives that are more specific or more creative.

Fourth, maintain an IP review checklist for all product launches. Don't let trademark review be optional or conditional on the product's perceived importance. Every feature, every product, every brand should go through the same rigorous process. Open AI is large enough to have systematic processes, but somewhere the Cameo trademark got overlooked. Systematic review catches these issues.

Finally, build in time for IP review in your product development timeline. Don't treat it as something that can be squeezed in at the last minute. If you're planning to launch a feature in Q2, start the trademark review in Q1. This gives time to do thorough research, address any issues, and rebrand if necessary before launch.

The Temporary Restraining Order and Injunctive Relief

One of the most important aspects of the Cameo case is how quickly the court acted. In November 2024, just after Cameo filed its complaint, the court granted a temporary restraining order. This is a powerful tool that stops the alleged infringer from continuing the infringing activity immediately, without waiting for a full trial. For Open AI, this meant the company had to stop using "Cameo" in its products right away.

A temporary restraining order is granted when the plaintiff can show that they're likely to suffer irreparable harm if the defendant continues the infringing activity, and that the plaintiff is likely to win on the merits of the case. The court agreed that Cameo would suffer irreparable harm to its brand if Open AI continued using the Cameo name. Brand damage is inherently difficult to quantify and repair, which is why courts treat it as irreparable.

The temporary restraining order forced Open AI's hand. The company could have fought it, arguing that the harm to Cameo was minimal or that rebranding would be more costly than allowing the continued use. But the company chose to comply and rename the feature to "Characters." This suggests Open AI's legal team advised that fighting the temporary restraining order was unwise, either because they thought they'd lose or because the PR cost of fighting wasn't worth the benefit.

The temporary restraining order then remained in effect while the case proceeded to a full ruling. The court eventually made a permanent judgment, finding that Open AI had indeed infringed on Cameo's trademark. At that point, the restraining order became permanent injunctive relief—a court order requiring Open AI to cease using the infringing name.

For companies facing trademark disputes, understanding the temporary restraining order process is crucial. If you're accused of trademark infringement, the court can order you to stop the infringing activity even before a full trial. This is a nuclear option that can force immediate business changes. Companies need to take trademark conflicts seriously and address them early, before they escalate to temporary restraining orders.

Conversely, if you believe someone is infringing on your trademark, a temporary restraining order can be an effective tool to stop the infringement quickly. You don't have to wait months for a full trial. You can ask the court to stop it immediately. This is exactly what Cameo did, and it worked.

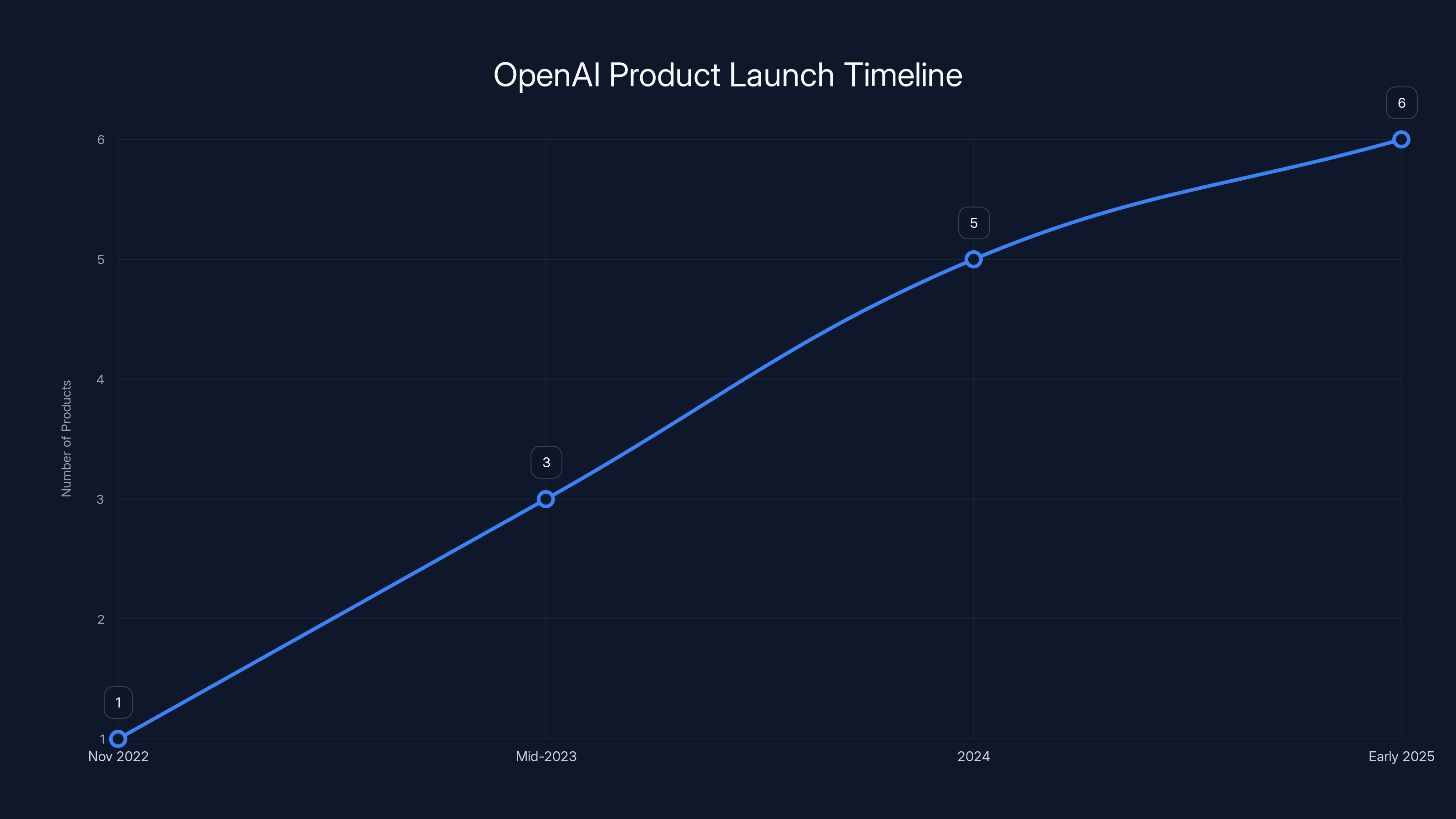

OpenAI's rapid growth is illustrated by the increasing number of product launches from late 2022 to early 2025. Estimated data.

How the Rebranding to "Characters" Affects Open AI's Strategy

Open AI's decision to rebrand from "Cameo" to "Characters" was pragmatic but carried costs. Rebranding is never just about changing a name. It involves updating all marketing materials, documentation, internal systems, customer-facing features, and communications. For a feature that was already in use by people, the rebranding created confusion. Users who had discovered the "Cameo" feature had to learn that it was now called "Characters."

The new name "Characters" is actually more generic and less evocative than "Cameo." It describes the feature without suggesting its purpose. When you hear "Characters," you don't immediately understand that this is about inserting your likeness into videos. You might think it's about generating fictional characters or managing character animations. This is a weaker brand name from a marketing perspective, which is exactly why "Cameo" was a better choice (until it ran into trademark issues).

The rebranding also sends a subtle message to consumers. When a feature gets renamed after legal pressure, some users interpret it as evidence of a conflict or problem. Even if users don't understand the trademark issue, they notice that a feature they knew about has been renamed, and they might wonder why. This isn't catastrophic, but it's a minor reputation cost that Open AI has to bear.

From a product development perspective, the rebranding reveals something about Open AI's development process. If the company had caught the trademark issue during internal review, it never would have launched with the "Cameo" name. The fact that it launched and then had to rebrand suggests that either the trademark review process failed, or it was skipped entirely. This is valuable intelligence for how Open AI operates and what other IP issues might be lurking in its product pipeline.

Interestingly, "Characters" might actually be the better long-term name from a trademark perspective. Generic names are harder to defend as trademarks because they describe the feature rather than brand it. But generic names are also less distinctive in the marketplace. Open AI is essentially using a weaker brand name to avoid future trademark conflicts. This is a tactical win for trademark law but a strategic loss for Open AI's brand.

Trademark Law in the Age of AI and Rapid Development

The Cameo case raises deeper questions about whether traditional trademark law is well-suited to the pace of AI development. AI companies move incredibly fast. New features launch weekly or even daily. Full-scale product reviews for every update might seem impractical. But the alternative is exactly what happened with Open AI and Cameo—companies launch first, check the legal implications later.

Trademark law was developed long before software existed. The assumptions built into trademark law were shaped by physical goods and established markets. You couldn't just launch a new consumer product overnight in the 1970s. You had to manufacture it, distribute it, market it. This gave time for legal review. But with software, especially AI software, you can go from idea to global deployment in days or weeks. This creates an inevitable collision between the pace of development and the pace of legal review.

The question is whether trademark law should evolve to account for this new reality. Should there be a different standard for trademark infringement by AI companies that move quickly? Should courts consider that rapid innovation sometimes means names haven't been thoroughly vetted? The Cameo case suggests the answer is no. Courts apply the same trademark standards regardless of whether the defendant is a traditional company or a fast-moving AI startup.

This doesn't necessarily mean AI companies are at a disadvantage. It means they need to adapt their development processes to account for legal realities. The solution isn't to ask for special treatment. It's to build trademark review directly into the product development pipeline. Thorough trademark research is fast and inexpensive compared to litigation. It should be a standard step in the feature development process, not an afterthought.

Another interesting question is whether trademark protection should be narrower in technology markets given how quickly things change. A trademark holder like Cameo wants broad protection to prevent any similar uses of their brand. But AI companies arguing for narrower interpretation would argue that this stifles innovation. If Cameo can prevent any use of "Cameo" for any video-related feature, doesn't that effectively remove a useful word from the vocabulary of technology developers?

The Cameo case doesn't resolve this tension. It simply applies existing law to a new context. As AI continues to develop and businesses move faster, this tension will likely become more acute. Future cases might refine trademark law to better account for the realities of rapid software development.

The Cameo case is expected to significantly influence AI companies, particularly in trademark research and product naming caution. Estimated data.

The Impact on Celebrity and Creator Economies

The Cameo case also has implications for the creator and celebrity economy that both Cameo and Open AI are tapping into. Cameo's business model depends on celebrities and creators trusting the platform. The company built that trust over nine years. When Open AI launched a feature with the Cameo name, it created potential confusion that could undermine creator trust. Open AI's feature allowed users to generate AI videos with their own likeness, but it didn't involve real celebrities. Cameo's feature does involve real celebrities. Confusing the two could damage both brands and create trust issues for creators.

Cameo's victory in this lawsuit is actually good for the creator economy broadly. It signals that platforms that invest in building trust with creators have legal protection against competitors who might try to piggyback on that reputation. This creates incentives for platforms to invest in creator relationships and brand building, knowing that their investment is legally protected.

For creators using Cameo, the lawsuit outcome is straightforward good news. It means the Cameo brand remains distinctly associated with their work and their platform. Creators who have built audiences on Cameo benefit from the platform's brand protection. It keeps Cameo distinct from competitors and prevents brand dilution.

For creators who might use Open AI's "Characters" feature (previously "Cameo"), the lawsuit has mixed implications. The feature allows creators to generate their own AI-powered video content, which could be valuable. But the trademark issue and subsequent rebranding create some uncertainty about the feature's stability and the company's commitment to it. If Open AI had to change the name after launch, what else might change?

The broader implication is that platforms in the creator economy need to be more careful about IP issues when building features. Open AI's mistake shows what happens when you don't respect existing brands and trademarks. The cost isn't just legal fees and rebranding—it's lost brand value and creator uncertainty.

Precedent and Future Implications for AI Companies

The Cameo case establishes useful precedent for how trademark law applies to AI features and products. Future trademark disputes involving AI companies will likely reference this case. The ruling makes clear that: one, AI companies aren't exempt from trademark law; two, descriptive use arguments don't apply when the name suggests a connection to an existing brand rather than purely describing functionality; and three, trademark holders can get rapid relief through temporary restraining orders if they can show likelihood of confusion and irreparable harm.

This precedent will likely make AI companies more cautious about product naming going forward. When they see that Open AI—one of the most successful and well-resourced AI companies in the world—got caught infringing on a trademark, they'll take the hint. Trademark research will become a standard, non-negotiable part of the product launch process.

The case also matters for trademark holders. It shows that they can successfully defend their marks against well-funded defendants who might have better legal teams and more resources. Cameo, as a venture-backed startup, won against Open AI, a company worth over $100 billion. This proves that trademark law protects trademark holders fairly, regardless of the defendant's size or resources.

Future cases will likely expand on different aspects of this ruling. What happens if an AI company uses a similar but not identical name? What if the goods or services are more distant? What if the defendant can show actual consumer confusion was minimal? These questions will shape how trademark law evolves as AI companies continue to launch new features and products.

The precedent also matters for how other tech companies think about IP strategy. The Cameo case is a high-profile example of a company that did things right—protecting its trademark, enforcing it vigorously, and winning in court. This will likely encourage other brands to be more aggressive about protecting their intellectual property. Companies will invest more in trademark monitoring and enforcement, knowing that courts will back them up.

Estimated data shows that tech companies often face trademark disputes, with outcomes varying. OpenAI's loss to Cameo highlights the importance of thorough trademark checks.

Lessons for Startups and Emerging AI Companies

For early-stage AI companies, the Cameo ruling is a critical lesson in the importance of IP diligence. A startup with limited resources might think trademark research is a luxury it can't afford. The Cameo case shows this is a dangerous perspective. For a startup, a trademark conflict could be existential. A major company like Open AI can rebrand and move on. A startup might not survive the disruption.

The lesson is to treat trademark research as a mandatory part of product planning, not an optional detail. Before you settle on a product name, spend a few hours (or hire someone for a few hours) to research whether that name is already taken. The cost is negligible compared to the cost of building a product around a name you can't use.

Second, early-stage AI companies should think about trademark strategy proactively. If you're building a product you think will be significant, consider registering trademarks for your brand and key product names. This is inexpensive and gives you legal protection if competitors try to copy your branding. It also forces you to think carefully about what your brand is and what it represents.

Third, startups should avoid names that could create confusion with existing brands, even if those brands operate in somewhat different markets. The Cameo case shows that courts will find confusion likely even across somewhat different services (Cameo's personalized celebrity videos vs. Open AI's AI video generation). If there's any risk of confusion, it's usually better to pick a different name than to fight a trademark battle.

Finally, startups should build relationships with IP lawyers who understand technology. Most lawyers specialize in particular areas of law. You want someone who understands both trademark law and the technology industry. These specialists can help you navigate IP issues more effectively than generalists.

The Broader Context: Open AI's Rapid Growth and IP Challenges

Open AI has grown at an extraordinary pace. The company launched Chat GPT in November 2022, and by mid-2023 it was the fastest-growing application in history. By 2024 and early 2025, Open AI had launched or expanded numerous products: Chat GPT Plus, GPT-4, GPT-4V, DALL-E 3, Sora, and a coming hardware platform. This pace of innovation is unprecedented and incredible, but it also creates challenges.

One challenge is that rapid growth sometimes means internal processes don't scale as quickly as product development does. IP review might have been thorough when Open AI was smaller. But as the company scaled to thousands of employees and dozens of products, institutional processes sometimes lag. The Cameo case might be symptomatic of this scaling challenge.

Open AI has also been aggressive in pushing boundaries, both technologically and legally. The company trained its language models on huge amounts of data, including copyrighted content. It launched features and products sometimes without exhaustive legal review. This "ask for forgiveness rather than permission" approach has served the company well in some contexts. You can't innovate at the pace Open AI has if you're overly cautious about every possible legal issue.

But the Cameo case suggests that this approach has limits. At some point, being aggressive about legal boundaries creates liabilities that outweigh the benefits. The company has been sued by the New York Times, by artists, by various creators and media organizations. The Cameo case is relatively minor in the grand scheme of Open AI's legal challenges, but it's emblematic of a pattern.

For Open AI going forward, the challenge is to maintain its innovation pace while also being more deliberate about legal and IP issues. This means investing in IP expertise within the company, building robust review processes, and empowering teams to raise IP concerns during product development. It's not a matter of being less innovative. It's a matter of being smarter about the legal landscape while innovating.

What Happens Next: The Ongoing Impact

The Cameo ruling is final, but its impact will ripple through the tech industry for months and years. First, every AI company and tech company will likely commission internal trademark audits of their existing products and features to make sure they're not infringing on anyone's marks. Second, product naming processes across the industry will become more rigorous. Teams will understand that trademark research is not optional.

Second, trademark holders will likely become more aggressive about defending their marks. The Cameo case proved that they can win even against well-resourced defendants. This will encourage other brands to enforce their trademarks more vigorously. We'll probably see more trademark disputes in the coming years, not fewer.

Third, the legal costs of defending intellectual property will increase across the board. Companies will hire more IP lawyers, conduct more thorough research, and build more robust review processes. These are all costs that ultimately get passed down to consumers through higher prices or slower innovation. The Cameo case is a small example of why strong IP protection, while important for protecting brands, does have an economic cost.

Open AI's rebranding from "Cameo" to "Characters" is now complete, but the company's IP challenges are far from resolved. The New York Times case is ongoing, as are the artist copyright suits. The hardware platform naming conflict was only recently resolved. As Open AI continues to innovate, the company will likely face more IP challenges. The company seems to be learning that innovation at scale requires attention to intellectual property realities.

FAQ

What is trademark infringement?

Trademark infringement occurs when one party uses a mark (word, logo, phrase) that is similar enough to an existing registered trademark that it creates a likelihood of confusion in the marketplace. The infringement violates the trademark holder's exclusive rights to use the mark for the goods or services it covers. Courts examine factors like the similarity of the marks themselves, the similarity of the products or services, and whether consumers might reasonably confuse the two brands.

Why did Open AI lose the Cameo trademark case?

Open AI lost because it used "Cameo" as the name for a video feature in Sora, and Cameo had already registered and trademarked the "Cameo" name for its celebrity video platform. The court found that the names were identical, the services were similar enough (both involving personalized video content), and Cameo's trademark was strong (built on nine years of brand recognition). Open AI's argument that "Cameo" was merely descriptive failed because the court found it suggested a connection to the existing brand rather than purely describing the feature.

What is a temporary restraining order?

A temporary restraining order is a court order that stops a defendant from continuing an alleged infringing activity immediately, without waiting for a full trial. It's granted when the plaintiff can show they're likely to win the case and that they'll suffer irreparable harm if the defendant continues. In the Cameo case, the court granted a temporary restraining order that forced Open AI to stop using "Cameo" in November 2024, even before the final ruling in February 2025.

How does trademark law apply to AI products?

Trademark law applies to AI products the same way it applies to any other products. AI companies must respect existing trademarks and cannot use names or brands that are confusingly similar to existing registered marks. There are no special exemptions for AI companies or cutting-edge technology. The Cameo case established that AI companies face the same trademark standards and risks as traditional tech companies or any other businesses.

What is the difference between trademark and copyright?

Trademarks protect brand names, logos, and identifiers that distinguish one company's products from another's. Copyrights protect original creative works like software code, articles, music, and videos. The Cameo case is a trademark dispute because it involves the right to use the brand name "Cameo." Open AI's copyright disputes with the New York Times and artists are separate issues involving whether the company had the right to use their creative works to train its AI models.

How should AI companies avoid trademark infringement?

AI companies should conduct thorough trademark searches before naming new products or features. They should check the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office database and consider working with trademark attorneys for major launches. They should avoid names that could create confusion with existing brands, even in somewhat different markets. They should build systematic trademark review into their product development process and maintain IP checklists for all product launches. This is especially important given how quickly AI companies develop and deploy new features.

What did Open AI's rebranding from Cameo to Characters accomplish?

Rebranding from "Cameo" to "Characters" brought Open AI into compliance with the court's ruling and stopped the trademark infringement. However, the new name is more generic and less evocative, making it a weaker brand from a marketing perspective. The rebranding also required updating all marketing materials, documentation, and customer-facing features. While rebranding solved the legal problem, it carried costs in terms of brand value and user confusion about why a feature they knew had been renamed.

Does this mean AI companies can never use descriptive words as product names?

No, AI companies can use descriptive words as product names, but they cannot use descriptive words if those words are already registered trademarks. If a word is already trademarked and the trademark is strong (well-known and in use), using the same word for a similar product creates trademark infringement risk. The Cameo ruling found that "Cameo" wasn't purely descriptive anyway—it suggested a connection to the existing brand rather than just describing the feature functionally.

Key Takeaways: What the Open AI Cameo Case Reveals

The Open AI trademark infringement case is a watershed moment for how AI companies approach intellectual property protection. At its core, the case demonstrates that rapid innovation doesn't exempt companies from trademark law. When Open AI named a feature "Cameo" without apparently conducting thorough trademark research, it created legal liability that forced a costly rebranding. For a company worth over $100 billion, the financial impact might be manageable, but the reputation impact was real. Open AI had to publicly back down from a product name, and the broader message it sent was that the company's internal IP review processes needed work.

The case also reveals the importance of trademark protection for companies building brands. Cameo, a venture-backed startup, successfully defended its trademark against one of the world's most powerful AI companies. This proves that trademark law works and that companies which invest in brand building have legal recourse when competitors infringe. It creates incentives for responsible branding and discourages free-riders who might try to leverage established brands without authorization.

For the AI industry broadly, the case is a clarion call to take intellectual property seriously. As AI companies develop new products and features at unprecedented speed, they need to build trademark review into their development processes. This isn't optional or conditional on the product's perceived importance. Every feature, every product name, every brand initiative should go through trademark review before launch. The cost of doing this upfront is trivial compared to the cost of fighting lawsuits or rebranding after launch.

The case also matters for startup founders and emerging AI companies. If Open AI—with unlimited resources and presumably competent legal teams—couldn't catch a trademark infringement before launching, startups need to be even more careful. A trademark conflict could be existential for an early-stage company. Startups should treat trademark research and protection as mandatory, not optional.

Looking forward, expect more IP conflicts in the AI industry. As more AI companies launch more products and features, trademark disputes will likely increase. Companies will become more aggressive about defending their intellectual property, knowing that courts will back them up. The Cameo case establishes that even powerful AI companies can lose trademark disputes if they've clearly infringed on established marks. This will make other trademark holders more confident in defending their rights.

The broader lesson is that the tech industry's "move fast and break things" mentality needs to evolve as companies grow and the stakes get higher. You can innovate rapidly and still respect intellectual property. It just requires building IP considerations into your development process from the start. The companies that master this balance—innovation velocity plus IP diligence—will win. The companies that treat IP as an afterthought will face expensive legal battles and brand damage.

Open AI will recover from the Cameo case. A rebranding is a minor inconvenience for a company of its size and resources. But the case serves as a useful reminder that in the tech industry, legal realities matter. No matter how revolutionary your technology or how fast you're moving, you still have to play by the rules. And when you don't, the courts will enforce those rules, even against companies that are changing the world.

Related Articles

- MyMiniFactory Acquires Thingiverse: Protecting 8M Creators From AI [2025]

- Peter Steinberger Joins OpenAI: The Future of Personal AI Agents [2025]

- OpenAI Hires OpenClaw Developer Peter Steinberger: The Future of Personal AI Agents [2025]

- OpenClaw Founder Joins OpenAI: The Future of Multi-Agent AI [2025]

- Seedance 2.0 and Hollywood's AI Reckoning [2025]

- Seedance 2.0 Sparks Hollywood Copyright War: What's Really at Stake [2025]

![OpenAI Loses Cameo Trademark Case: What It Means for AI Companies [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/openai-loses-cameo-trademark-case-what-it-means-for-ai-compa/image-1-1771398372604.jpg)