The New Era of Hardware-Optimized AI Coding

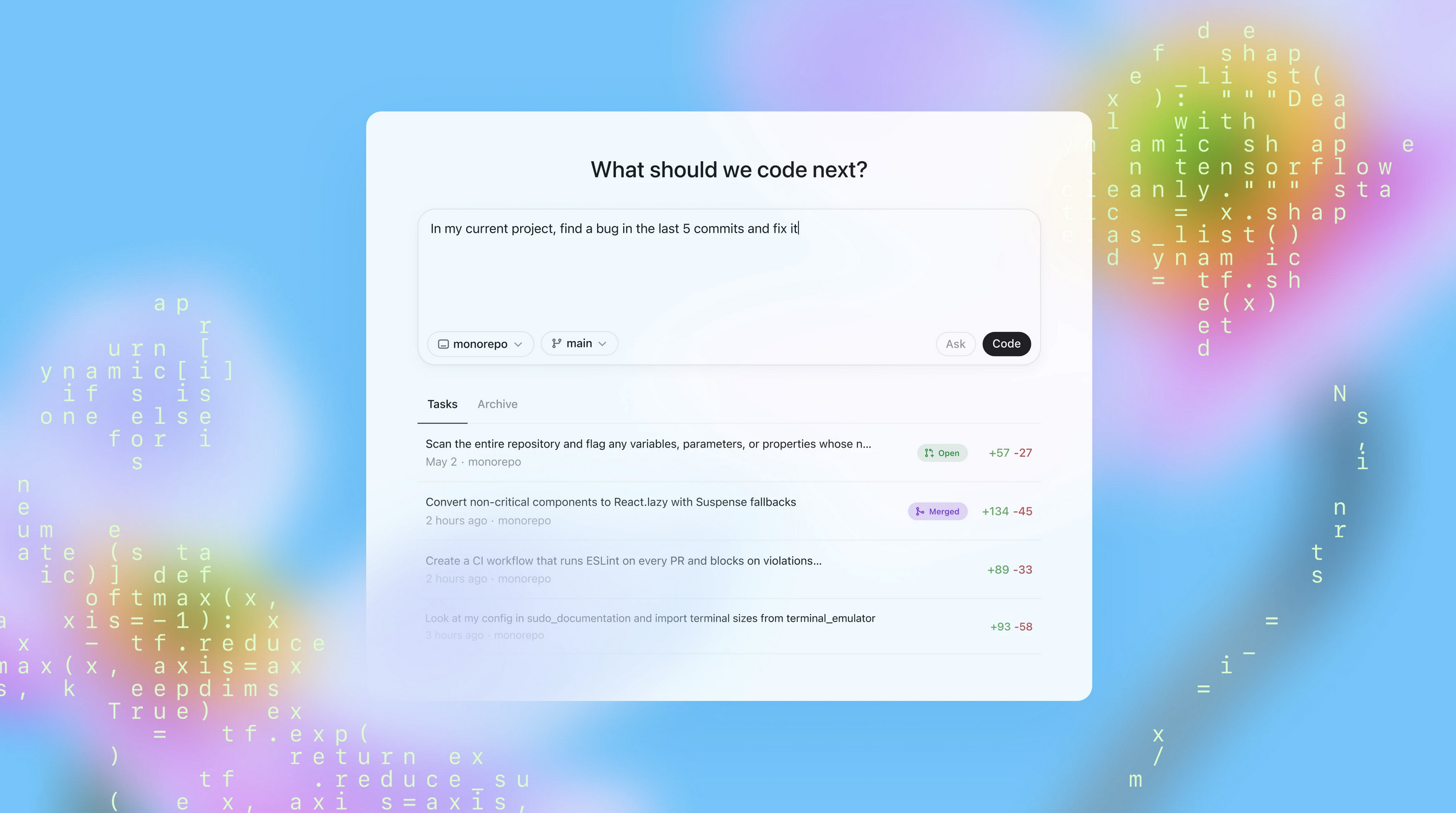

Last Thursday, OpenAI dropped something that probably didn't make headlines outside tech circles, but it should have. The company announced Codex-Spark, a lightweight version of its GPT-5.3-Codex agentic coding tool, paired with Cerebras' custom silicon. This isn't just another model update. It's the first public milestone of OpenAI's multi-billion dollar hardware partnership, and it signals a fundamental shift in how AI companies are thinking about inference optimization.

Let me be straight about what makes this important. Most AI companies treat inference like an afterthought. You build a model, you ship it, you hope it's fast enough. OpenAI is doing the opposite. They're saying: "Real-time coding assistance requires different hardware than batch processing." So they're building custom chips specifically for that job.

The partnership between OpenAI and Cerebras was announced last month with a staggering $10 billion multi-year commitment. At the time, OpenAI positioned it as a way to "make our AI respond much faster." Spark is that first proof point. The tool runs on Cerebras' Wafer Scale Engine 3 (WSE-3), a third-generation megachip with 4 trillion transistors packed onto a single wafer. To put that in perspective, that's roughly 400 times more transistors than a high-end consumer GPU, all designed to work as a unified processor rather than a fragmented system.

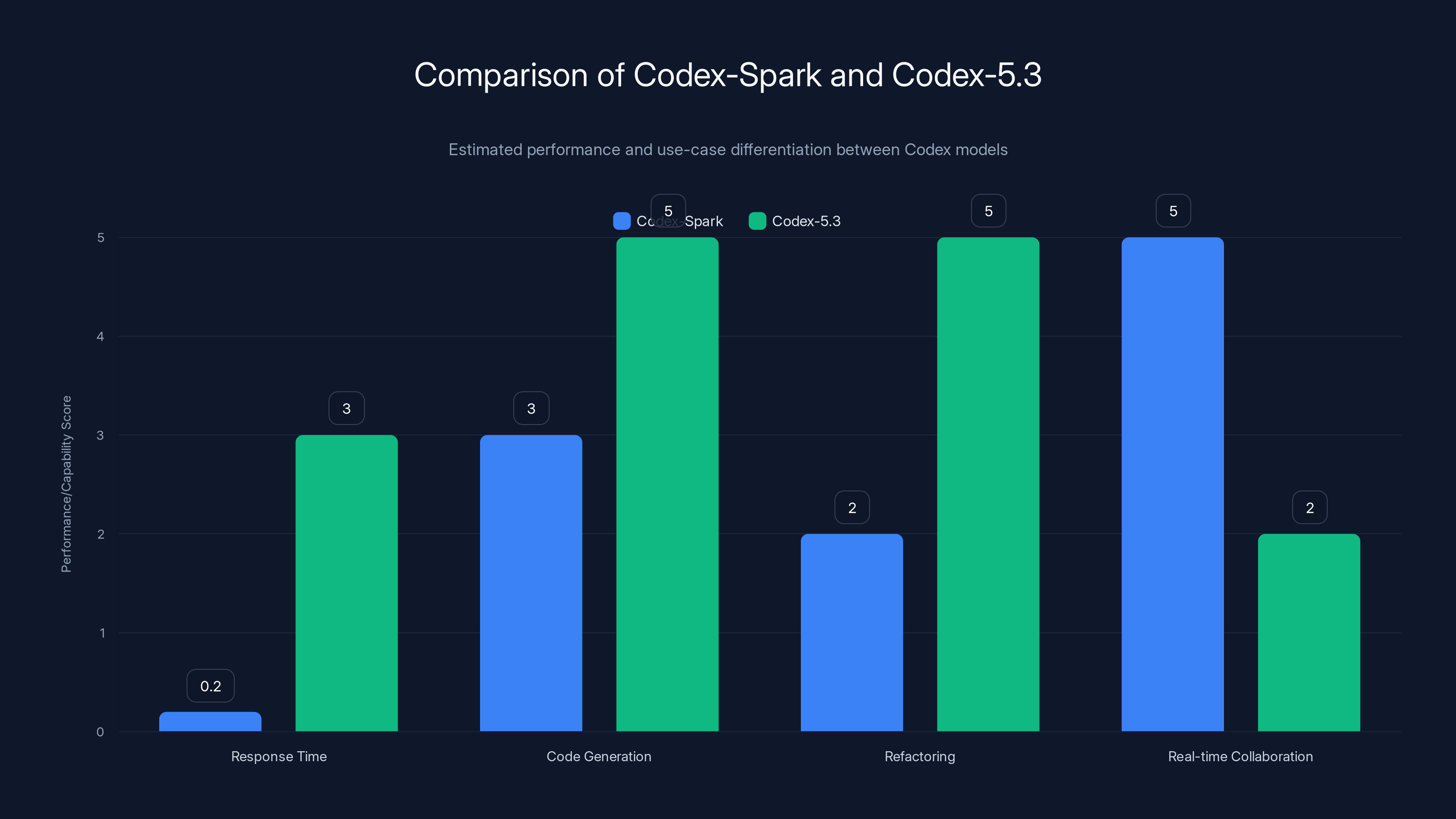

Here's where it gets interesting. Spark isn't the heavy lifter that the full Codex-5.3 is. It's optimized for speed, not raw capability. OpenAI explicitly calls it a "daily productivity driver" for rapid prototyping and real-time collaboration. The original Codex-5.3 handles longer, deeper reasoning tasks. Spark gets you an answer in milliseconds. This dual-model strategy solves a real problem that developers face: sometimes you need a quick suggestion, sometimes you need a thoughtful solution.

The timing matters too. We're in an era where latency has become a competitive moat. Response time isn't just about user experience anymore. It's about whether an AI tool feels integrated into your workflow or like a separate tool you're waiting on. A 500ms delay feels interactive. A 2-second delay feels broken. Spark, powered by Cerebras' architecture, is engineered to stay in that interactive zone even during peak usage.

What's notable is that this partnership between OpenAI and Cerebras represents a broader trend: the commodification of AI compute is over. Companies that can design custom silicon for specific tasks will have a structural advantage over those that don't. We're seeing this play out across the industry. This isn't just OpenAI's strategy anymore. It's becoming table stakes.

Understanding Cerebras' WSE-3: The Hardware Behind the Speed

Before you can understand why Spark matters, you need to understand Cerebras' approach to chip design. The company has been around for over a decade, but it's only in the last few years that their vision has started making sense to the broader industry.

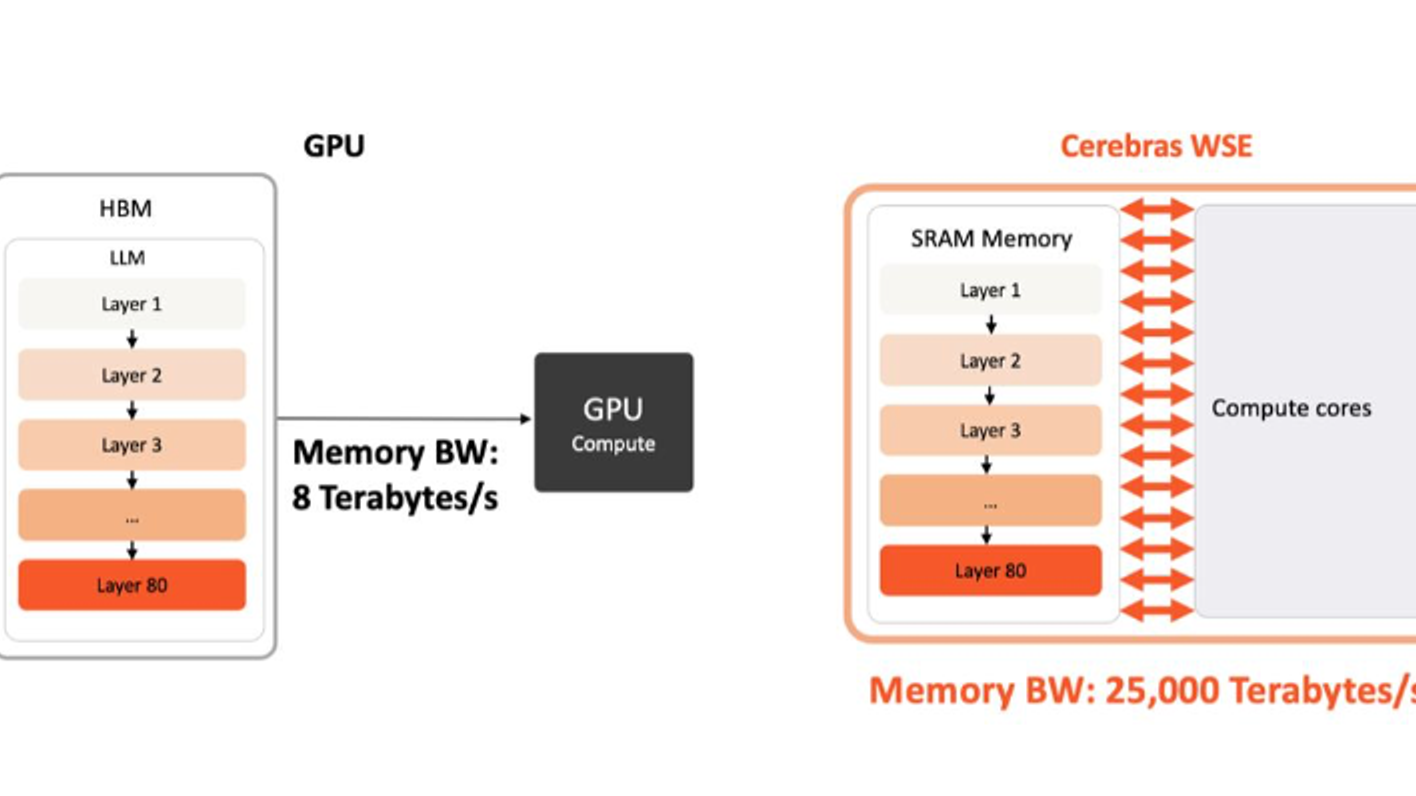

Most processors, including GPUs, are built modularly. You have multiple cores, each with its own cache, connected by a network. This design made sense for general-purpose computing. But for AI workloads, especially inference, this modularity becomes a bottleneck. Data has to travel between cores, through interconnects, sometimes across the network. Every hop adds latency.

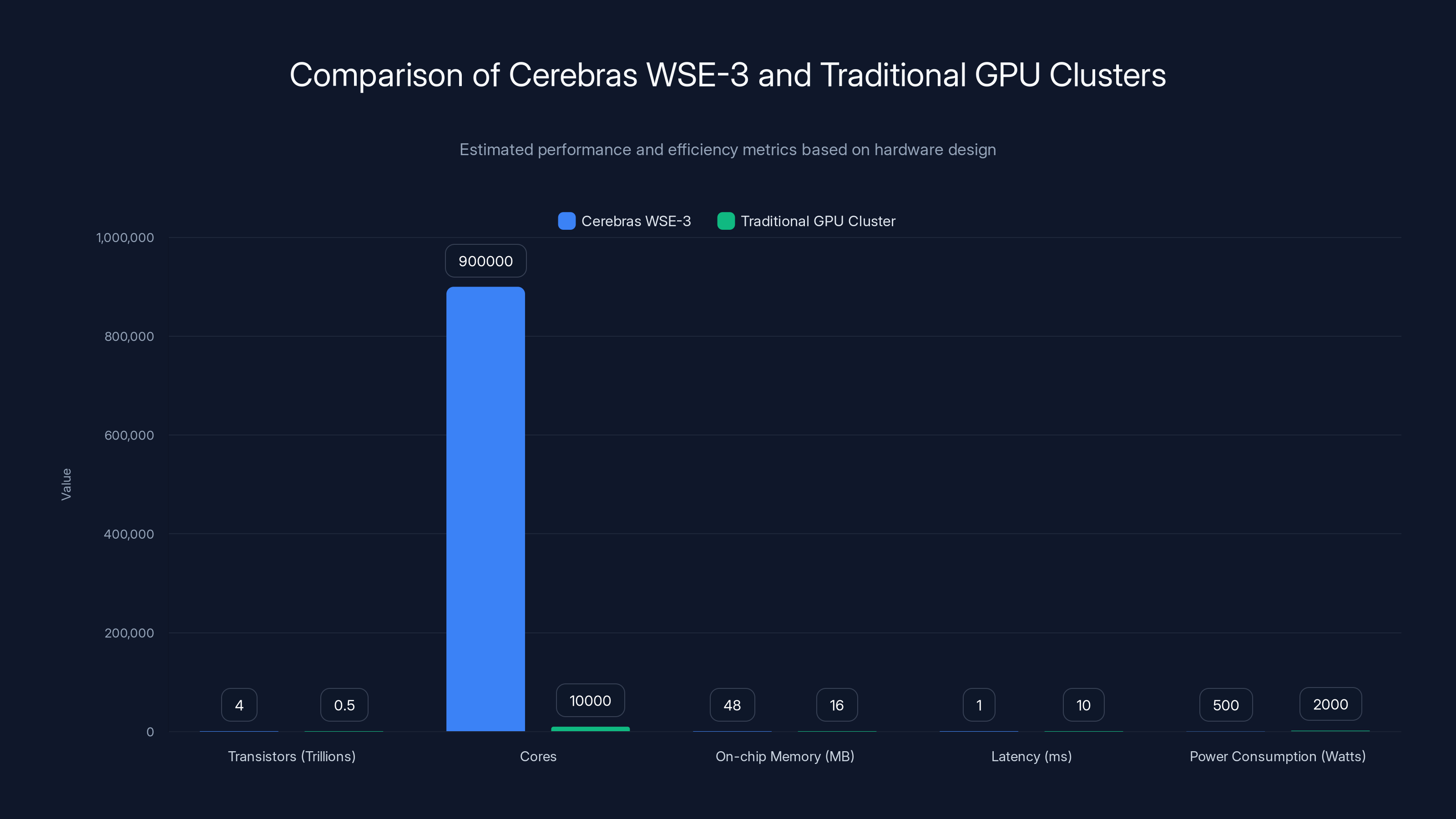

Cerebras' Wafer Scale Engine approach is radically different. Instead of multiple chips on a board, they build one massive chip that covers an entire wafer. The WSE-3 contains 4 trillion transistors, 900,000 cores (yes, you read that right), and 48MB of on-chip memory. All of that is connected by a unified fabric that allows any core to communicate with any other core in a single clock cycle.

Let's think about what this means in practice. When you run an inference operation on a traditional GPU cluster, data bounces around. Tensor A is on GPU 1, Tensor B is on GPU 3, the result needs to go to GPU 2. Each transfer adds latency. On WSE-3, that doesn't happen. The data stays local. Everything is connected by a single ultra-fast fabric. Communication overhead drops dramatically.

The economics are interesting too. Cerebras' chips are expensive. The company isn't competing on cost. They're competing on density and speed. A single WSE-3 wafer can do the work of multiple GPU clusters while consuming a fraction of the power. For a company like OpenAI running millions of inference requests per day, this efficiency compounds quickly.

Cerebras has been investing heavily in software to make their chips accessible. They've built compilers, optimizations, and frameworks that map traditional AI workloads onto their architecture. When OpenAI adopted WSE-3 for Spark, they weren't starting from scratch. They were building on years of optimization work.

The third-generation chip is meaningfully faster than its predecessors. The company has publicly mentioned improvements in bandwidth, memory access patterns, and inter-core communication. These aren't flashy, marketing-friendly numbers, but for inference latency, they're everything. A 20% improvement in memory bandwidth might translate to a 30% reduction in inference time, depending on the workload.

One thing that surprises people is that Cerebras' chips aren't primarily GPU competitors. They're built for a different computational model. GPUs excel at massively parallel operations on fixed-size data structures. Cerebras excels at dynamic, fine-grained parallelism with irregular memory access patterns. For certain AI workloads, especially those that benefit from sparse computation, WSE-3 has a substantial advantage.

The fact that Cerebras just raised

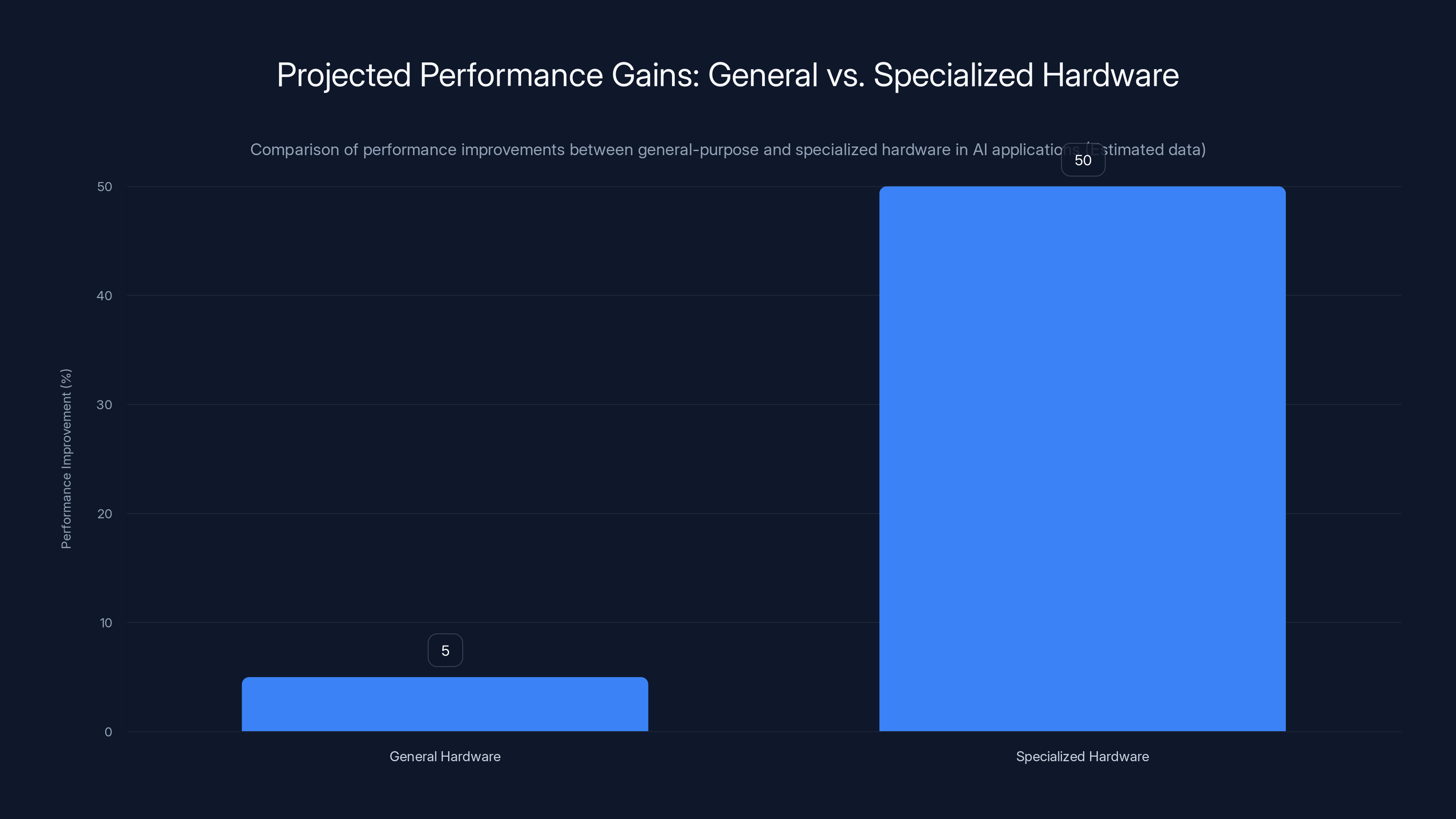

Cerebras' WSE-3 significantly outperforms traditional GPU clusters in terms of core count and latency, while consuming less power. Estimated data.

Codex-Spark vs. Codex-5.3: Understanding the Strategic Split

OpenAI's decision to split Codex into two models is worth examining because it reveals something fundamental about how they're thinking about AI products going forward. This isn't a simple "lite" and "full" version. It's a strategic choice about what different users need at different times.

Codex-5.3, the full version, is designed for comprehensive code generation, complex refactoring, and multi-file reasoning. It's the version that understands architectural patterns, can suggest design improvements, and handles ambiguous requirements. If you ask Codex-5.3 to "refactor this codebase to use dependency injection," it understands the domain, the patterns, the implications. This requires more computation. More reasoning steps. More context processing. That's why it's slower.

Spark is different. It's optimized for immediate feedback. You're typing code, and Spark is suggesting completions. You're debugging, and Spark is pointing out potential issues. You're writing a test, and Spark is filling in the assertion logic. These tasks need answers in under 200ms. Beyond that, the interaction feels sluggish.

The latency requirement is the critical constraint. For Codex-5.3, you're willing to wait 2-3 seconds. For Spark, you're not. That one-second difference forces entirely different architectural decisions. You can't just run Codex-5.3 faster. You have to make it simpler.

What's clever about OpenAI's approach is that Spark isn't just a quantized or pruned version of Codex-5.3. It's a separately trained model, optimized from the ground up for fast inference. The training process itself is different. The model architecture is different. The context window might be smaller. The vocabulary might be optimized for common coding patterns rather than rare edge cases.

This two-model strategy also solves a business problem. Not every developer needs the full power of Codex-5.3. Many would be happy with Spark if it's cheaper and faster. By offering both, OpenAI can serve different customer segments. Pro users get access to Spark immediately. Paying customers who need the full model can access Codex-5.3. Free tier users might get limited access to Spark.

The research preview is currently available to Chat GPT Pro users in the Codex app. That's a significant group. Chat GPT Pro has millions of subscribers. OpenAI gets to test Spark at scale immediately. They're collecting performance data, user feedback, and real-world usage patterns. All of that informs future iterations.

Sam Altman's Twitter hint—"It sparks joy for me"—is worth reading into. The name "Spark" is deliberate. It suggests quick, energetic, immediate. Compare that to the methodical connotations of the full Codex. The marketing is subtle but precise. OpenAI is telling developers: this is for the quick moments, not the deep dives.

Over time, I expect the strategies to evolve. Spark might get capabilities that full Codex doesn't have, specifically for the latency-constrained use case. OpenAI might introduce Spark in different languages or optimization profiles. The infrastructure they've built—the ability to run different models on different hardware—enables this kind of experimentation at scale.

The Silicon-Software Symbiosis: Why Custom Hardware Matters Now

The OpenAI-Cerebras partnership represents something that's been building for years but is now becoming obvious. The age of pure software optimization is ending. The next decade of AI progress requires hardware and software codesigned together.

Here's the fundamental problem. Moore's Law is slowing down. We're approaching the physical limits of transistor shrinking. The easy 2x performance gains every two years are gone. We're in the realm of single-digit percentage improvements. Meanwhile, AI demand is growing exponentially. More models, more users, more inference requests. You can't sustain that with software alone.

The solution is specialization. Build hardware for the specific workload, optimize the software to the specific hardware, iterate on both together. That's what OpenAI and Cerebras are doing. It's what Google does with TPUs. It's what Amazon is doing with Trainium and Inferentia chips. It's what every serious AI company will eventually be forced to do.

The economic incentive is compelling. If OpenAI can reduce the cost per inference by 50%, they can either pocket the margin or drop prices and grab market share. They can serve more users with the same infrastructure investment. They can offer features that were previously uneconomical. All of that compounds.

But there's a cost to specialization. You lose flexibility. A WSE-3 is optimized for inference. It's not great for training. A GPU is general enough to handle both. By going all-in on specialized silicon, OpenAI is betting that inference demand will be stable enough to justify the investment. Given the trajectory of their API business, that's a reasonable bet.

The software side matters as much as the hardware. Cerebras has built compilers that automatically map AI models onto their architecture. But that's not automatic for every model. The more sophisticated the mapping, the better the performance. OpenAI and Cerebras are probably working closely on custom optimizations for Codex-Spark. That's where the real advantage lives.

This also creates a switching cost. If you optimize Codex-Spark for WSE-3, you're not going to randomly switch to a different chip next year. That's a multi-year commitment. For Cerebras, it's validation of their approach. For OpenAI, it's a strategic bet on Cerebras' continued dominance in this space.

What's interesting is that this doesn't mean GPUs are going away. They're not. But they're becoming the commodity tier. If you want maximum performance for inference, you're moving to specialized silicon. If you want good-enough performance with flexibility, you're using GPUs. That's the emerging market structure.

Codex-Spark excels in real-time collaboration with ultra-low latency, while Codex-5.3 is superior in comprehensive code generation and refactoring. Estimated data.

The 10 Billion Dollar Question: Is This Partnership Paying Off?

Let's talk about the elephant in the room. OpenAI committed $10 billion to Cerebras. That's a staggering amount of capital. The first public deliverable is Spark, a lightweight coding tool. Is that a good return on investment?

First, the time horizon matters. This is a multi-year agreement. A single product release isn't the measure of success. The real measure is whether OpenAI can build an entire infrastructure layer on Cerebras silicon. If Spark is successful, it won't be the last product running on WSE-3. OpenAI will likely migrate more inference workloads. They might build products specifically designed for WSE-3's strengths.

Second, the efficiency gains are real. If Spark running on WSE-3 costs 50% less to run than it would on GPU clusters, that difference matters at scale. OpenAI runs millions of inference requests per day. A 50% cost reduction translates to tens of millions of dollars annually. Over a 10-year commitment, that's hundreds of millions. The math starts to work.

Third, there's a strategic dimension. By investing in Cerebras, OpenAI is securing supply of specialized silicon. They're not dependent on NVIDIA, Intel, or AMD. They have a dedicated partner whose success is tied to OpenAI's success. That's valuable insurance in a world where AI compute is a bottleneck.

But there are risks. Cerebras has never scaled manufacturing to the level that OpenAI needs. The company has announced plans to scale production, but that's easier said than done. If Cerebras can't deliver enough wafers, the whole strategy falls apart. That's probably why Cerebras just raised $1 billion. They need to invest in manufacturing capacity.

There's also the technical risk. What if WSE-3 doesn't perform as well in production as it did in the lab? What if the power consumption is higher than expected? What if Cerebras' software stack has limitations that become apparent at scale? These are real risks. OpenAI is betting on Cerebras' engineering, but no engineering is perfect.

From Cerebras' perspective, this partnership is validation and liability in equal measure. Validation that their approach is correct. Liability because they're now responsible for supporting one of the world's most demanding customers. If Cerebras fails to deliver, OpenAI will have expensive alternatives available. Cerebras' entire business case rests on executing flawlessly.

The market will ultimately judge whether this partnership pays off. If Spark is fast, responsive, and cheaper to run than alternatives, it will gain adoption. If it underperforms, users will gravitate toward competitors. The competitive landscape matters here. Are there alternatives that are just as good? That's an open question.

What we do know is that this partnership signals OpenAI's seriousness about vertical integration. They're not content to be a software company running on commodity hardware. They want to control the entire stack. That's the trajectory of successful tech companies. Google did it with TPUs. Apple did it with custom silicon. OpenAI is following the same playbook.

Real-Time Collaboration: The Use Case That Justifies the Hardware

Why does latency matter so much? Because it changes how people interact with tools. This is a principle that product designers understand intuitively, but it's worth making explicit.

There's a concept in human-computer interaction called the "response time threshold." Below 100ms, interactions feel instant. The user doesn't consciously perceive a delay. Between 100ms and 1000ms, the interaction feels responsive but slightly laggy. Above 1000ms, the interaction feels sluggish and broken. Users start to switch context, open email, check Twitter.

For real-time coding assistance, the ideal is below 200ms. That's in the sweet spot where suggestions feel instantaneous. The developer's flow state isn't interrupted. The suggestion arrives before the developer has typed the next character.

Codex-Spark is engineered specifically for that threshold. Running on WSE-3, with its ultra-low latency architecture, Spark can deliver suggestions in the 100-200ms range. That's a meaningful difference compared to systems that require 500ms to 2 seconds.

What does this enable? Imagine you're writing a function. You type the function signature, and Spark immediately suggests the implementation. The suggestion appears while you're still thinking about the logic. You can accept it, reject it, or modify it. The interaction is fluid. You're not waiting. You're collaborating.

Compare that to a slower system. You type the function signature. You wait two seconds. The suggestion appears. You've already started typing the body yourself. The suggestion is less useful because you've already committed to a direction. The tool feels like an afterthought rather than a collaborator.

This distinction is profound for productivity. Studies on developer tools have shown that interaction latency is one of the strongest predictors of tool adoption. Faster tools get used more. They get integrated into workflows. They become indispensable. Slower tools get sidelined, even if they're technically superior.

OpenAI's focus on real-time collaboration is sophisticated product thinking. They're not trying to build a tool that generates perfect code. They're building a tool that fits into the natural rhythm of coding. Spark is the interface between the developer's thinking and the AI's suggestions, and that interface needs to be seamless.

The technical challenge is substantial. Real-time inference at scale is hard. You need sub-200ms latency while serving millions of concurrent users. You need to handle variable load. You need to ensure reliability. One slow request can cascade and blow out the entire tail latency for that batch. Cerebras' architecture helps with the fundamental latency, but OpenAI's engineering has to optimize everything else: batching, scheduling, prioritization, fallbacks.

The fact that OpenAI is leading with real-time collaboration as the headline for Spark tells you something about where they think the value is. It's not raw capability. It's not accuracy. It's not breadth of knowledge. It's responsiveness. That's product-market-fit thinking. They're building for actual user needs.

Competitive Implications: What This Means for the Industry

If OpenAI successfully executes on this strategy, the competitive landscape for AI infrastructure shifts significantly. Let me walk through the implications.

First, any company that wants to compete with OpenAI on inference needs to think seriously about custom silicon. The cost and latency advantages are too significant to ignore. That's a substantial barrier to entry. Not every company has the capital to invest $10 billion in hardware partnerships. That creates consolidation pressure.

Second, the model of "build inference, serve to users, iterate" becomes less viable. If you're trying to compete with OpenAI on cost or latency, you need custom silicon from day one. You can't start on GPUs and graduate to custom chips later. By then, you're behind.

Third, the companies that control silicon become more important. Cerebras is now OpenAI's key infrastructure partner. That's an enormous amount of leverage. Other companies will seek similar partnerships. You'll see more exclusive arrangements between AI companies and chipmakers. That's bad for competition. Exclusive arrangements reduce flexibility and increase switching costs.

Fourth, there's a resourcing implication. Building custom silicon is a specialized skill. There are only a handful of companies globally that know how to do this well. OpenAI, Google, Amazon, Meta, and maybe a few others. Everyone else is at a disadvantage. Talent and expertise become the limiting factor, not capital.

Fifth, the international dimension matters. Custom silicon development involves significant IP and export controls. Governments care about this. The U.S. government will likely continue to restrict China's access to advanced AI chips. That creates geopolitical dimension to this infrastructure race. Countries without indigenous silicon capacity will be at a disadvantage.

For smaller companies, the implications are sobering. If you're building an AI product and you don't have a hardware strategy, you're already losing the race. The question isn't whether to invest in custom silicon. It's how. For most startups, the answer is to find an investor with deep pockets and a long-term vision. Alternatively, partner with a chipmaker and focus on specific use cases where you can optimize more aggressively than incumbents.

Open source projects face particular challenges. How do you compete with proprietary inference infrastructure? You can't. What you can do is focus on areas where latency isn't the primary constraint or where users prefer flexibility over performance. That's a smaller market, but it's real.

Estimated data: Using WSE-3 could reduce inference costs by 50%, potentially saving OpenAI tens of millions annually.

The Broader Hardware-Software Codesign Trend

OpenAI and Cerebras aren't alone in this thinking. The entire industry is moving toward hardware-software codesign. It's worth stepping back and understanding why this is happening now.

For most of software history, the abstraction between hardware and software was sacred. You wrote code, it compiled to instructions, the CPU executed those instructions. The abstraction was so clean that you could switch CPUs and your code still worked. That was the power of the Von Neumann architecture.

But AI breaks that abstraction. AI workloads have such specific computational patterns that generic hardware is inefficient. A GPU was designed for graphics rendering. You can map AI workloads onto that pipeline, but it's not optimal. A TPU was designed for tensor operations. That's closer, but still a compromise. Custom silicon designed specifically for a particular AI workload can be orders of magnitude more efficient.

Google learned this with TPUs. TPUs enabled Google to scale machine learning internally. Google now has TPUs embedded throughout their infrastructure. Cloud TPU is a commercial product. Google is betting that specialized silicon is the future of computing infrastructure.

Amazon is doing the same with Trainium (for training) and Inferentia (for inference). Meta is investing in custom silicon. Microsoft is partnering with chipmakers. Everyone is moving the same direction.

The trend accelerates because of economics. If you can build inference hardware that's 3x faster and uses 5x less power, you can profitably undercut your competitors. That margin is too attractive to ignore. So every serious AI company is investing in custom silicon.

What emerges is a new model of competition. It's not just about software anymore. It's about the entire stack: hardware, compilers, optimizations, algorithms, training data, interfaces. Companies that can integrate all of these layers win. Companies that focus on a single layer lose.

OpenAI's partnership with Cerebras is their way of saying: we're going to compete across the entire stack. We're not going to be dependent on NVIDIA. We're going to build our own infrastructure. That's the stance of a company that wants to dominate the market, not just participate in it.

The implication for the industry is that the next 10 years will be defined by vertical integration. Companies will control more of their supply chain. We'll see fewer partnerships and more acquisitions. Companies that can't keep up will be acquired or die. The landscape will consolidate around a few dominant platforms.

Infrastructure Requirements: What Spark Demands Behind the Scenes

When you talk about Spark running on WSE-3, it's easy to think of it as a simple swap: run the model on different hardware, get faster results. The reality is much more complex. Spark running on WSE-3 requires rethinking the entire inference infrastructure.

First, there's the question of batch size and scheduling. Traditional GPU inference systems optimize for throughput. You batch as many requests as possible into a single GPU kernel. That maximizes utilization but increases latency variability. Some requests wait longer than others. For real-time applications, you need predictable latency.

WSE-3's architecture actually helps with this. Because the entire wafer is a unified processor, there's less scheduling overhead. But you still need to make scheduling decisions. How many concurrent requests do you schedule? How do you prioritize them? How do you handle stragglers that might slow down everyone else?

Second, there's the memory architecture. WSE-3 has 48MB of on-chip memory. That's enormous compared to GPU caches, but it's still finite. You need to carefully manage which parts of the model live on-chip and which live off-chip. Memory access patterns become critical. Poorly optimized memory access can negate all of WSE-3's latency advantages.

Third, there's the question of batching vs. latency tradeoffs. If you batch 100 requests together, you reduce the per-request cost but increase latency for each request. For Spark, the latency constraint is tight. You probably can't batch more than 10-20 requests before exceeding the 200ms threshold. That's much lower than traditional inference systems that batch 100+ requests.

Fourth, there's failover and redundancy. You can't have a single WSE-3 as your production system. If it fails, everything fails. You need multiple wafers, load balancing, fallback mechanisms. But now you're talking about multiple $10+ million investments in hardware. The capital requirements are substantial.

Fifth, there's the question of model updates. When you publish a new version of Spark, you need to deploy it to all the WSE-3 systems. That's straightforward in principle but complex at scale. You're rolling out across multiple data centers, potentially globally. You need sophisticated deployment infrastructure. A bad rollout can make the service unreliable.

Sixth, monitoring and observability. You need deep insight into what's happening on WSE-3. How much memory is being used? How are requests being scheduled? Where are the bottlenecks? Traditional profiling tools don't work on custom silicon. You need custom instrumentation.

Seventh, there's the question of multi-tenancy. Can multiple customers run their workloads on the same WSE-3? Probably not initially. The latency guarantees would be difficult to maintain. So initially, OpenAI might dedicate wafers to specific use cases. That's capital intensive but necessary for reliability.

All of this means that the infrastructure team behind Spark is probably substantial. It's not just about running a model on different hardware. It's about building an entirely new inference platform from the ground up. That's a significant engineering investment.

The Path to Production: How Spark Evolved from Announcement to Reality

Let's think about the timeline here. OpenAI announced the Cerebras partnership last month. This month, they're announcing Spark. That's fast. Faster than you'd typically expect for a project of this magnitude. What does that tell us?

One possibility is that the work was already underway before the public announcement. OpenAI and Cerebras probably spent months (or longer) collaborating before they felt confident enough to announce the partnership. The announcement was just the public reveal of work that was already advanced.

Another possibility is that OpenAI had Spark in development as part of their broader Codex-5.3 efforts and brought Cerebras into the project after initial prototypes were working. That would allow for faster integration because the model architecture was already mature.

A third possibility is that OpenAI and Cerebras worked together quickly because of existing relationships. Both companies have deep expertise with large-scale AI infrastructure. They probably understand each other's constraints and capabilities. Collaboration with an expert partner is faster than collaboration with a novice.

The research preview is interesting from a development perspective. OpenAI isn't shipping Spark as production-ready. It's a research preview for Chat GPT Pro users. That's a large user base but still contained. OpenAI gets to iterate quickly based on real-world feedback without the pressure of full production support.

This staged rollout is smart. Early users find bugs and edge cases that testing doesn't catch. OpenAI collects telemetry on latency, failure rates, user satisfaction. They identify bottlenecks in the infrastructure. They optimize based on actual usage patterns. By the time Spark is production-ready, it will have been battle-tested at significant scale.

The fact that Sam Altman tweeted about it before the official announcement suggests the company is excited about the progress. When CEOs personally promote product launches, it usually means the project exceeded internal expectations. That's a good signal for users.

Looking ahead, the progression probably goes: research preview for Pro users, then general availability for Chat GPT Pro, then integration into other OpenAI products. Eventually, maybe Spark appears in the API for third-party developers. Each step requires infrastructure scaling and optimization.

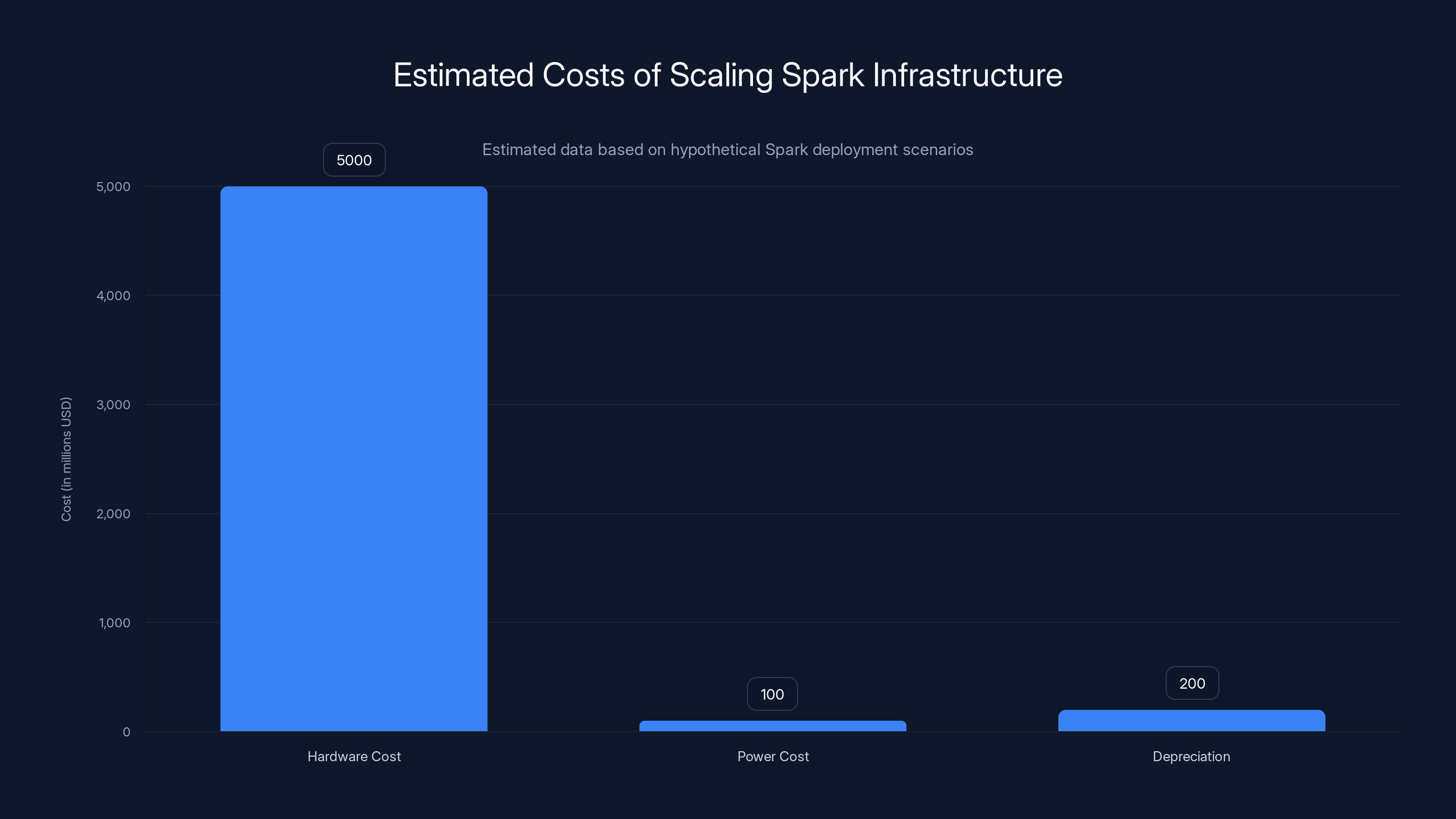

Estimated costs for scaling Spark to serve millions include

User Experience: How Real-Time Feels Different

Here's something that's easy to miss if you're focused on the technical details. Real-time coding assistance changes the user experience fundamentally. It's not just faster, it's different.

When you interact with a slower system, you adopt a different workflow. You write more code locally before asking for help. You batch your requests. You minimize context switches. You optimize for throughput rather than latency. The tool becomes asynchronous to your thinking.

With Spark, the opposite happens. You write a function signature, and the implementation appears before you've finished thinking. You start writing a test, and Spark suggests the assertion. You make a change and immediately see suggestions for related changes in other files. The tool becomes synchronous to your thinking. It's collaborative, not auxiliary.

This matters for productivity in subtle ways. When a tool is fast enough, you start using it for things you wouldn't ask a slower tool to do. You might ask for a single-line completion. You might ask Spark to explain why a particular pattern is used. You might ask it to generate test cases for edge cases you hadn't considered. The tool enables exploration rather than just implementation.

For learning, this is valuable. Junior developers can work alongside Spark and learn from its suggestions. The feedback is immediate, so the learning loop is tight. Over time, developers internalize the patterns and need Spark less. That's the goal of a tool like this.

For experienced developers, the value is different. Spark handles the boilerplate. The routine stuff. The patterns that don't require deep thinking. That frees up mental energy for the complex parts. Architecture decisions, edge cases, performance optimization. The developer and the tool divide labor based on what each is good at.

The user experience of real-time is also about trust. If a tool responds instantly, you trust it. You interact with it like a colleague. If a tool takes five seconds, you're skeptical. You second-guess it. You double-check its suggestions more carefully. Latency undermines trust, even when the quality is identical.

OpenAI understands this. That's why they invested so heavily in the latency side. Spark isn't just a lighter model. It's a rethinking of what coding assistance should feel like. The hardware is a means to that end, not the goal in itself.

Scaling Challenges: What Happens When Millions Use Spark

The research preview is one thing. Production at scale is another. Let's think about what happens when Spark has millions of users.

First, there's the raw capacity question. How many WSE-3 wafers do you need to serve millions of concurrent users? If you need 200ms latency, you probably can't batch more than 10-20 requests per wafer. A single wafer can process, let's say, 500 requests per second in that regime. To serve 100,000 concurrent users with 200ms latency, you need 500+ wafers. At

Second, there's geographic distribution. You can't serve all users from a single location. Latency would be too high. You need distributed inference across multiple regions. That means distributing the infrastructure globally. That's a complex operational challenge.

Third, there's model updating. When you release a new version of Spark, you need to roll it out to all the wafers globally without dropping requests. That's a sophisticated operation. You're probably doing rolling deployments with canary testing. You need to monitor performance closely. One bad deployment can impact millions of users.

Fourth, there's the question of model staleness. If you're constantly updating Spark, users will see different behavior from day to day. How do you version the API? How do you ensure consistency? Do you commit to a specific version for a session, or do you update on the fly? These are UX and technical questions that matter.

Fifth, there's the cost model. At scale, inference cost becomes a critical business metric. You need to understand the cost per request. If you're running Spark on WSE-3 and WSE-3 has

Sixth, there's redundancy. You probably can't tolerate more than 1-2 seconds of downtime. That means N+1 or N+2 redundancy. Every critical component needs failover. That compounds the capital requirements. If you need 500 wafers for normal capacity and 1.5x that for redundancy, you're talking 750 wafers. At

Seventh, there's the organizational challenge. Operating infrastructure at this scale requires expertise. You need SREs who understand WSE-3 deeply. You need specialized teams for monitoring, debugging, optimization. You need processes for handling incidents. As the scale grows, the complexity compounds.

These challenges are solvable. Companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have solved them for their own infrastructure. OpenAI has the resources and expertise to do the same. But it's not trivial. The engineering required to go from research preview to production at scale is substantial.

The Future of Coding Assistance: Where Spark Points

If Spark is successful, what comes next? That's the question worth thinking about.

One direction is deeper integration into development environments. Instead of using Spark as a separate tool, it becomes part of your IDE. You're editing code and Spark suggestions appear inline. Your IDE understands the context better than a standalone tool. Integration with your codebase, your team's conventions, your project's history. This makes suggestions more relevant.

Another direction is multi-modal assistance. Right now, Codex-Spark handles code. What if it also handled documentation, tests, and requirements? You're writing a feature, and Spark simultaneously generates tests, updates documentation, and suggests architecture changes. The tool becomes a full-stack assistant, not just a coding tool.

A third direction is real-time learning. Spark learns your preferences, your coding style, your patterns. It gets better at predicting what you want. Over time, the suggestions become more accurate because the model has internalized your personal style. This requires privacy-preserving training, but it's technically possible.

A fourth direction is collaboration. What if Spark helped multiple developers work on the same codebase? It could suggest merge strategies, identify conflicts, propose refactoring to reduce interdependencies. The tool becomes a facilitator of team coordination.

A fifth direction is creative coding. Using Spark not just for implementation but for ideation. You describe what you want to build in natural language, and Spark generates multiple possible implementations. You explore the design space quickly. You iterate on variations. The tool becomes a partner in design decisions.

Sixth is the question of autonomy. When does a coding assistant become a coding agent? When does it suggest not just individual functions but entire features? When does it proactively identify technical debt and propose fixes? The boundary between assistant and agent is blurry, but it's shifting toward autonomy.

All of these directions share a common theme: faster feedback loops. Real-time inference enables tight feedback loops. Tight feedback loops enable new workflows. New workflows attract users. Users driving new use cases informs the next generation of models. It's a virtuous cycle.

The hardware investment OpenAI and Cerebras have made is foundation for this cycle. If Spark enables these new workflows, they'll justify the infrastructure investment many times over. If Spark is just a faster version of existing tools without new capabilities, the ROI is questionable. OpenAI is betting that speed enables capability. History suggests they're right.

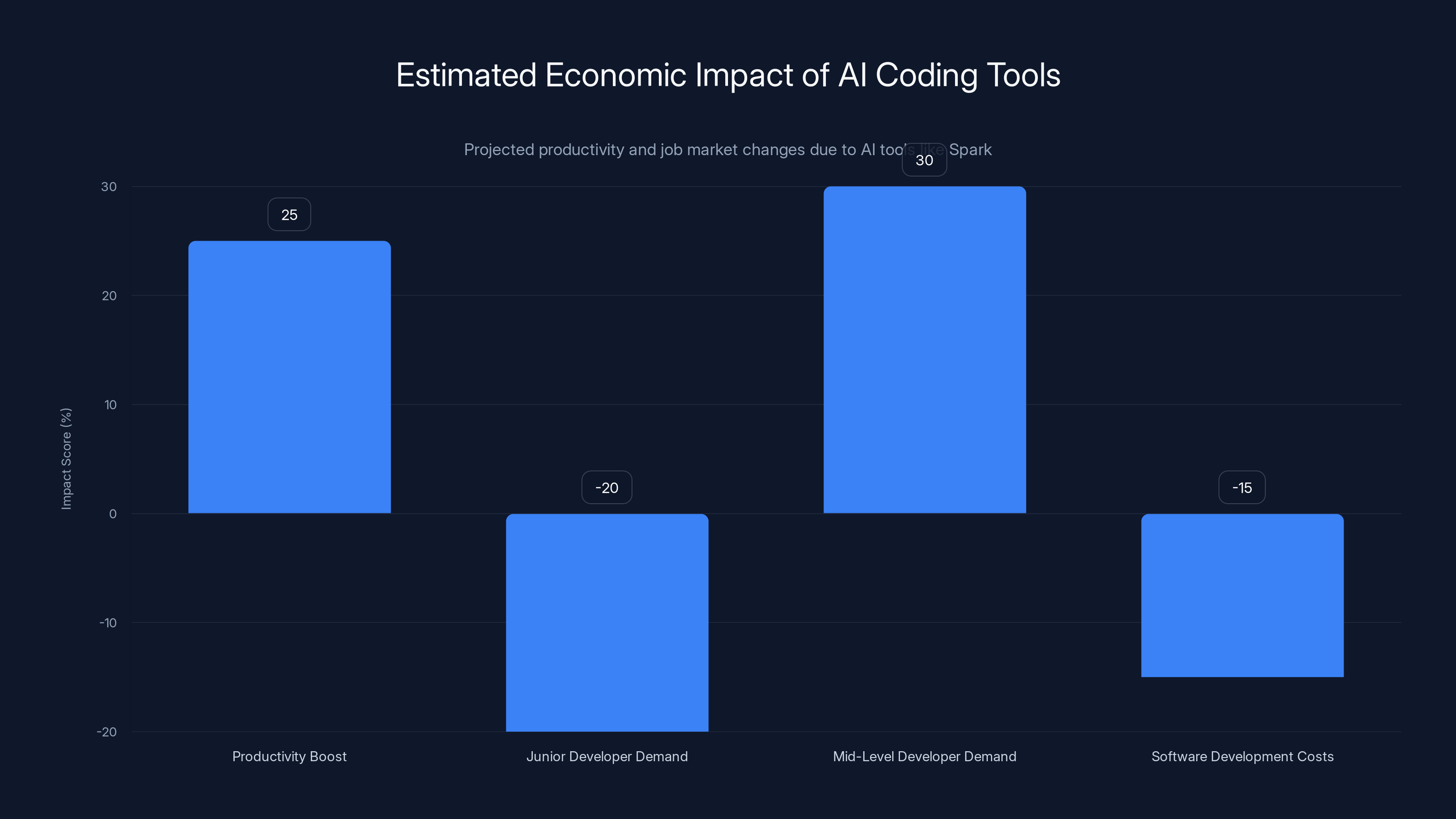

AI coding tools like Spark are estimated to boost developer productivity by 25%, reduce demand for junior developers by 20%, increase demand for mid-level developers by 30%, and decrease software development costs by 15%. Estimated data.

Competitive Reactions and Market Response

When OpenAI launches something significant, competitors respond. It's worth thinking about what that might look like.

Google has TPUs and access to enormous amounts of compute. They could build a coding assistant on TPUs that's competitive with Spark. They have the infrastructure. They have the talent. The question is whether they prioritize it. Google has PaLM and Bard. They could invest more heavily in code generation. Whether they will depends on strategic priorities.

Microsoft has GitHub Copilot, which was the first widely used AI coding tool. Copilot was built on Codex. Now that OpenAI is moving to Spark, Microsoft is behind. They could continue to use the full Codex-5.3 and focus on the IDE integration, which is where Copilot has an advantage. Or they could invest in lower-latency models of their own. Given Microsoft's partnership with OpenAI, they might get access to Spark as well. That would shift the competitive dynamic.

Amazon has CodeWhisperer, built on their own models. CodeWhisperer is competent but hasn't captured market share from Copilot. Amazon could invest heavily in latency optimization. They have Inferentia chips that could help. The question is whether Amazon prioritizes this market. They have other priorities.

Startups could attack the market from a different angle. Instead of trying to compete on latency globally, they could focus on specific languages or frameworks. Codex-Spark is general-purpose. A focused tool optimized for Python, or React, or Rust could be superior for that niche. Startups have the agility to find and dominate niche markets.

The open-source community could build on models like Llama 2 and create their own coding assistants. These would run on commodity hardware and wouldn't have the latency advantages of Spark, but they'd be free and private. For teams that value privacy or cost, that's compelling.

Overall, I expect Spark to accelerate competition in coding assistance. The market will expand. More players will invest. We'll see differentiation not just in model quality but in latency, integration, customization, and cost. The competitive landscape will get more sophisticated.

Economic Impact: The Broader Implications

Let's zoom out and think about the economic implications of Spark and the broader trend it represents.

At the micro level, developers who use Spark will probably be more productive. There's been research suggesting that AI coding tools can boost productivity by 20-30%. If Spark achieves that through latency improvements, developers can do more work in the same time. That increases economic output per developer.

But there's a counter-effect. If AI can generate boilerplate code, the demand for junior developers writing boilerplate decreases. Entry-level coding jobs will be harder to find. The market for mid-level developers who specialize in complex problems will strengthen. The workforce will bifurcate.

At the macro level, if coding becomes more efficient, software development costs decrease. That makes software more accessible. Companies that previously couldn't afford to build their own software can now do so. That's good for innovation. It's bad for software companies with a cost-based business model.

The capital intensity of building AI products is increasing. Custom silicon investments are measured in billions. Not every company can afford that. This creates consolidation pressure. Smaller companies can't compete on infrastructure. They either partner with larger companies or exit. We'll see fewer but larger AI companies.

From a labor perspective, the impact is complex. Some jobs (coding boilerplate) will be automated. Other jobs (architecting complex systems) will become more valuable. The labor market will shift. There will be disruption. But overall, productivity growth usually creates more jobs than it destroys, albeit different jobs in different places.

From an investment perspective, this is bullish for infrastructure plays. Companies that provide the chips (Cerebras), the software stack, the deployment infrastructure, and the operational support will capture value. The opportunity cost of not investing in these capabilities is high.

From a geopolitical perspective, this reinforces the importance of leading in AI. The country that can build the most efficient AI infrastructure will have an economic advantage. That's probably the U.S. right now, but it's not guaranteed. China is investing heavily. Europe is trying to catch up. The race is on.

TL; DR

OpenAI launched Codex-Spark, a lightweight coding model optimized for real-time inference, powered by Cerebras' WSE-3 custom silicon chip. This represents the first milestone of their $10 billion partnership with Cerebras, signaling a strategic shift toward custom hardware optimization. Spark is engineered for sub-200ms latency to enable interactive coding workflows, splitting duties with the full Codex-5.3 model which handles deeper reasoning tasks. The partnership exemplifies the broader industry trend of hardware-software codesign, where specialized silicon becomes essential for competitive advantage. Success depends on scaling infrastructure globally while maintaining latency guarantees and managing capital-intensive hardware requirements. The implications ripple across the industry: competitors must invest in custom silicon, startups face higher barriers to entry, and the market consolidates around companies that can control the entire stack. Ultimately, Spark's success will define whether OpenAI's massive hardware bet pays off and establishes the template for next-generation AI infrastructure.

Specialized hardware can achieve significantly higher performance improvements compared to general-purpose hardware, with estimated gains up to 50% versus 5% for general hardware. Estimated data.

The Architecture of Speed: Understanding Wafer-Scale Processing

When Cerebras designed the WSE-3, they made fundamental choices about how to organize computation. These choices explain why the architecture is so well-suited to AI inference, particularly for tasks like Codex-Spark.

Traditional processors organize computation around cores connected by a network. The GPU paradigm extends this with thousands of small cores and massive parallelism. But there's a hidden cost: communication. When data needs to move between cores, it travels through interconnects. Those interconnects have bandwidth limits and latency. They consume power. They create bottlenecks.

The WSE-3 approach eliminates this intermediate layer. Instead of discrete cores connected by a network, it's a continuous fabric where every computational unit has direct access to every other computational unit through a unified switched network. Think of it not as thousands of cores connected by highways, but as a single massive system where every part can talk to every other part with equal efficiency.

This matters for AI workloads because AI computation is communication-heavy. In a transformer model, you're moving activations between layers. You're gathering attention weights. You're shuffling data for the next batch of operations. In a system with discrete cores, this movement is expensive. In a unified architecture, it's nearly free.

The 48MB of on-chip memory distributed across the wafer is another critical advantage. When you process a request in a traditional system, you pull the model weights from main memory, pull the input from main memory, process, write output back to main memory. Each of these memory accesses is a potential bottleneck. The model weights for a medium-sized model are gigabytes. You can't fit them on-chip. You have to fetch them continuously.

But with WSE-3's distributed memory, you can organize computation so that data stays local. The compiler knows the computation graph, knows the memory architecture, and organizes the execution to minimize long-distance data movement. The memory system becomes transparent. The programmer writes high-level operations, the compiler figures out the optimal layout.

There's also an efficiency story. All those discrete cores and interconnects in a traditional system consume power. The WSE-3, for a given amount of computation, consumes less power. That's because the architecture is optimized for the specific computation pattern of AI workloads. You're not paying for generality. You're getting efficiency.

But with efficiency comes specialization. The WSE-3 is phenomenally good at tensor operations with specific patterns. It's less good at sparse operations, conditional logic, or irregular computations. Codex-Spark probably exhibits patterns that play to WSE-3's strengths. That's why the partnership works. The model architecture and the hardware architecture are aligned.

The Software Stack: Making Hardware Accessible

Specialized hardware is worthless without software that knows how to use it. Cerebras has been building that software for years. The stack includes compilers, optimizers, runtime systems, and libraries.

The compiler is the critical piece. You write AI code using standard frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow. The compiler takes that code and maps it onto the WSE-3 architecture. This is non-trivial. The compiler has to understand the computation graph, the memory constraints, the execution model, and the specific performance characteristics of the hardware. It has to make tradeoffs.

For example, if you have a tensor operation that requires more than the available on-chip memory, the compiler has to spill to off-chip memory. But there's a choice: do you keep the data on off-chip memory and fetch portions as needed? Or do you tile the computation so that each tile fits on-chip? Each choice has implications for latency. The compiler has to make that choice intelligently.

The runtime system handles scheduling and execution. When you send a request to WSE-3, the runtime decides which parts of the chip process which parts of the computation. It manages synchronization between different parts of the computation. It handles the movement of data. It monitors progress and handles failures.

For a system like Spark, the runtime also handles multiple concurrent requests. Requests can't interfere with each other. The runtime has to partition the chip's resources fairly and ensure that one request doesn't monopolize the system. That's a constraint that traditional GPUs handle through batching. WSE-3 handles it through fine-grained scheduling.

The library ecosystem is another critical layer. Developers don't write low-level code. They use libraries for common operations: matrix multiplication, activation functions, attention. Cerebras has optimized these libraries to the WSE-3 architecture. When OpenAI uses these libraries in Codex-Spark, they get the performance advantages automatically.

All of this software is the result of years of investment. It's not something you can build in a few months. That's why partnerships between AI companies and chipmakers are valuable. The chipmaker brings the hardware expertise and the software stack. The AI company brings the models and the use cases. Together, they're more powerful than either could be alone.

Debugging and Observability: Visibility into Black Boxes

When you run Codex-Spark on WSE-3, what happens inside the chip? How do you know if it's working correctly? How do you debug problems? These questions matter when you're operating at scale.

Traditional processors have rich debugging tools. You can set breakpoints, inspect memory, trace execution. With GPUs, debugging is more limited but still possible. With a massive custom chip, debugging is an art form. You can't just halt the entire wafer to inspect memory. Too many concurrent requests would be affected. You need sophisticated instrumentation.

Cerebras has built tracing tools that record events during execution without significantly impacting performance. You can see which cores executed which instructions. You can see data movement. You can see where time was spent. This gives developers insight into what's happening inside the black box.

For OpenAI, this observability is crucial. When Spark serves a request in 200ms, where did the time go? Computation? Memory fetches? Scheduling overhead? By analyzing traces, OpenAI can identify bottlenecks. They can optimize the model, the compiler settings, or the runtime behavior. The feedback loop between observation and optimization is critical.

There's also the question of correctness. Does the model produce the right answers on WSE-3? You need numerical comparisons with reference implementations. You need edge case testing. You need validation that the optimization hasn't introduced bugs. This requires specialized testing infrastructure.

As OpenAI scales Spark to millions of users, observability becomes even more important. You need to monitor thousands of wafers globally. You need to detect anomalies. You need to identify when performance degrades. You need a global control plane that can manage the entire fleet. That's a non-trivial engineering challenge.

The Supply Chain Reality: Can Cerebras Scale?

There's a practical question underlying this partnership: can Cerebras actually manufacture enough wafers to meet OpenAI's demand? The company is planning to scale manufacturing, but that's easier said than done.

Manufacturing cutting-edge chips is a specialized skill. You need state-of-the-art fabs. Cerebras works with Samsung and other manufacturers. But fab capacity is limited. The global semiconductor industry is stretched. Getting wafer allocation from a fab is competitive. Established companies like Intel and TSMC get priority.

The WSE-3 is a massive chip. It uses the entire wafer. That creates manufacturing challenges. Yields might be lower than for smaller chips. A lower yield means higher costs. If Cerebras is only getting 70% of wafers at acceptable quality, the effective cost is 40% higher. That impacts the economics of the partnership.

Cerebras has raised capital to invest in manufacturing. But even with capital, they can't build fabs from scratch. That takes years. They have to work with existing manufacturers. That's a constraint on growth.

If Cerebras can't deliver enough wafers, OpenAI has options. They could diversify to other chip providers. They could invest in their own fabrication capacity (unlikely but possible). They could adjust Spark to use fewer wafers (reduces performance). None of these are ideal.

From Cerebras' perspective, the manufacturing challenge is existential. They have to deliver on time and at scale, or the partnership fails. That's a lot of pressure. But it's also opportunity. If they succeed, they're the provider of a critical resource for OpenAI. Their valuation reflects that.

Data Privacy and Model Training: The Spark Development Timeline

How did OpenAI and Cerebras get Spark ready so quickly? Part of the answer is that OpenAI had already done significant work on lightweight coding models. They weren't starting from scratch.

Another part is that the model itself might not be new. What's new is the deployment on WSE-3. OpenAI might have had a candidate model for Spark already ready. The work was integrating it with Cerebras infrastructure and optimizing it for WSE-3's architecture.

But there's a question about training data. Did OpenAI retrain Spark specifically for WSE-3, or is it a distilled version of an existing model? Retraining would be expensive and take time. Distillation would be faster. We don't know the answer, but it's likely some combination. A base model distilled from a larger model, then fine-tuned for specific use cases and performance characteristics.

The training process itself has privacy implications. If Spark was trained on user data from Codex, there are privacy considerations. OpenAI is likely careful about this. They probably have mechanisms to anonymize data, get consent, and limit exposure. But it's worth noting that the training data for these models often comes from real user interactions. That's why privacy and data security matter.

For a researcher, the reproducibility question is interesting. We don't know the exact details of how Spark was built. Was it a standard distillation process? Were there special optimizations? Were there specific architectural changes to optimize for WSE-3? These details matter for understanding the approach. But they're also competitive secrets. OpenAI isn't going to publish the full recipe.

Broader Context: AI Infrastructure as Strategic Moat

OpenAI's investment in Cerebras isn't an isolated decision. It's part of a broader strategy to control the infrastructure layer of AI. That strategy has deep roots in how successful tech companies operate.

Google's strategy with TPUs is instructive. Google built TPUs not because GPUs were insufficient, but because they wanted to reduce dependency on external vendors and optimize for their specific workloads. TPUs are now central to Google's AI offering. Cloud TPU customers pay a premium for the performance advantage. Google captures the value.

Apple's strategy with custom silicon is similar. Apple builds chips for iPhones, MacBooks, and other devices. These chips are optimized for Apple's specific use cases. They're more power-efficient than generic processors. That translates to longer battery life, which is a key selling point. Customers pay a premium for the device because of the performance and efficiency benefits.

OpenAI is applying the same logic. Build specialized infrastructure optimized for our specific workload. Reduce dependency on NVIDIA and other commodity chip vendors. Capture the efficiency gains and either lower costs or increase performance. Control the moat.

The $10 billion investment is huge, but it's an investment in strategic advantage. If it works, OpenAI reduces the operational cost of inference dramatically. That gives them a competitive advantage that competitors can't easily replicate. They can either offer lower prices or invest in research and development. Either way, they pull further ahead.

This strategy has risks. If Cerebras fails to deliver or other approaches prove superior, OpenAI has locked in a bad decision. But if it works, the returns compound. The infrastructure advantage grows over time as the entire fleet of Spark deployments becomes more efficient.

The Talent and Expertise Question: Who Can Execute This?

Building custom silicon for AI is hard. It requires deep expertise in hardware design, software optimization, compiler technology, and distributed systems. It requires engineers who understand both the hardware and the algorithms. These people are rare.

OpenAI has probably hired heavily in infrastructure. They're building teams that understand WSE-3 in detail. They're working with Cerebras engineers who designed the chip. The collaboration brings together the best people from both sides.

But this creates a broader market dynamic. The companies that can execute this strategy will dominate. The companies that can't will lag. It creates a talent concentration. The best infrastructure engineers go to companies that are investing in custom silicon. Startups can't compete for talent because they don't have the capital to invest in hardware.

This talent concentration has long-term implications. The companies with the best infrastructure engineers will make better decisions. They'll optimize faster. They'll respond to problems more quickly. The advantage compounds. Winners pull further ahead. The market consolidates.

For education, this is a challenge. Universities need to teach chip design, compiler technology, and distributed systems optimization. But most researchers focus on algorithms and models. The infrastructure side is underfunded. That creates a gap between what industry needs and what universities produce.

Regulatory and Geopolitical Considerations

The OpenAI-Cerebras partnership has regulatory implications. Both companies are U.S.-based. The chips are manufactured by Samsung and other international fabs, but they're for a U.S. company. That attracts regulatory scrutiny.

The U.S. government has been focusing on AI safety and security. Custom chip partnerships are part of that focus. The government might view this partnership positively (good, companies are investing in U.S. infrastructure) or negatively (bad, concentration of power in one company). The trajectory isn't clear.

From a China perspective, the partnership reinforces the view that the U.S. is pulling ahead in AI infrastructure. China is making investments in custom silicon, but they're playing catch-up. The lead in custom silicon translates to a lead in AI capability, which has economic and military implications. That drives geopolitical tension.

Europe is trying to develop its own AI infrastructure strategy. The EU is investing in European chip design and manufacturing. But they're behind the U.S. and China. Partnerships like the OpenAI-Cerebras deal are reinforcing that gap.

The question of export controls also matters. Should the U.S. restrict the sale of advanced chips to other countries? The government has already restricted GPU sales. Custom AI chips might face similar restrictions. That affects which countries can participate in the AI economy.

All of this is context for why OpenAI is willing to invest $10 billion in Cerebras. It's not just an economic question. It's a strategic question about who controls AI infrastructure and what that means for the future.

FAQ

What is Codex-Spark and how does it differ from the full Codex-5.3 model?

Codex-Spark is a lightweight, optimized version of OpenAI's GPT-5.3-Codex designed specifically for real-time, interactive coding assistance. Unlike the full Codex-5.3 model, which excels at comprehensive code generation, complex refactoring, and multi-file reasoning tasks that can take several seconds to complete, Spark is engineered for ultra-low latency inference, targeting response times under 200 milliseconds. This architectural difference reflects different use cases: Spark handles rapid prototyping, inline suggestions, and real-time collaboration workflows, while Codex-5.3 addresses deeper reasoning tasks that benefit from more processing time and capability. The distinction represents a strategic choice to optimize for user experience rather than raw computational power.

How does Cerebras' WSE-3 chip enable the performance improvements Spark requires?

Cerebras' Wafer Scale Engine 3 (WSE-3) achieves its performance advantages through a unified architecture rather than the modular design of traditional processors. The chip contains 4 trillion transistors organized as a single connected fabric where every computational unit can communicate with every other unit in a single clock cycle. This eliminates the communication overhead that plagues traditional GPU systems, where data must travel through interconnects between discrete cores. Additionally, the WSE-3 includes 48MB of distributed on-chip memory, allowing computation to be organized so that data stays local, minimizing expensive off-chip memory accesses. For inference workloads like Codex-Spark, this architecture delivers sub-200ms response times that would be difficult to achieve on commodity hardware, enabling the real-time collaborative workflows that define the user experience.

What are the key benefits of running Codex-Spark on dedicated custom silicon rather than on GPUs?

Running Codex-Spark on Cerebras' WSE-3 offers multiple compounding advantages over traditional GPU infrastructure. First, latency is predictable and ultra-low, enabling the responsive user experience that real-time coding assistance requires. Second, energy efficiency is substantially higher because the architecture is optimized specifically for AI inference patterns rather than being general-purpose hardware. Third, operational costs per inference request decrease significantly, allowing OpenAI to either lower prices or invest the savings into research and development. Fourth, reduced dependency on external vendors like NVIDIA provides strategic autonomy and reduces supply chain vulnerability. Fifth, the unified architecture enables fine-grained scheduling of concurrent requests without the batching overhead that traditional GPUs require, which is essential for maintaining low latency under variable load. These benefits compound as scale increases, giving OpenAI a structural cost advantage that competitors cannot easily replicate without similar hardware investments.

Why did OpenAI and Cerebras decide to split Codex into two models with different capabilities?

The split reflects a fundamental insight about developer workflows and latency requirements. Most coding tasks don't require maximum capability; they require immediate feedback. Developers working on rapid prototyping, writing boilerplate code, or seeking inline suggestions benefit most from speed. However, complex tasks like major refactoring, architectural analysis, or multi-file reasoning benefit from deeper model capacity and longer processing time. By offering two models optimized for different constraints, OpenAI serves different needs efficiently. Spark users get sub-200ms responses, enabling real-time collaboration. Codex-5.3 users get comprehensive capabilities without latency pressure. This approach also solves business problems: it allows OpenAI to serve price-sensitive users with a lower-cost offering while maintaining a premium product for users who need maximum capability.

What does it mean that Spark is OpenAI's "first milestone" in their partnership with Cerebras?

The term "first milestone" indicates that the OpenAI-Cerebras partnership is a long-term strategic relationship, not a one-off collaboration. Spark's launch demonstrates that the partnership is functional and delivering real value, establishing proof of concept for running production AI workloads on Cerebras' custom silicon at scale. This success creates a foundation for expanding the collaboration: additional OpenAI products might migrate to WSE-3, more use cases might be optimized for the hardware, and the infrastructure advantage can deepen over time. From Cerebras' perspective, it validates their architecture and business model. From OpenAI's perspective, it demonstrates that the $10 billion investment is paying off. Future milestones might include broader availability of Spark, integration into the API for third-party developers, or optimization of other inference workloads on WSE-3. The partnership signals long-term commitment from both sides.

How will OpenAI scale Spark to serve millions of concurrent users while maintaining its latency guarantees?

Scaling Spark to millions of users while maintaining sub-200ms latency requires substantial infrastructure investments and sophisticated engineering. OpenAI will likely need hundreds of WSE-3 wafers distributed across multiple global data centers to minimize network latency to users. The infrastructure must implement N+1 or N+2 redundancy for reliability, meaning effective capacity requirements roughly 1.5 times the peak demand capacity. The software stack must handle request batching carefully (probably 10-20 requests per batch rather than the 100+ typical for GPU systems) to preserve latency while maximizing hardware utilization. Monitoring and observability become critical: OpenAI needs deep visibility into what's happening inside each wafer to identify and fix bottlenecks. Load balancing and routing mechanisms must be sophisticated enough to maintain latency even during traffic spikes. Finally, the organization must develop operational expertise in managing WSE-3 at scale, which is a specialized skill set. The capital requirements are substantial, but if executed successfully, the per-request cost advantage justifies the investment.

What are the competitive implications of OpenAI's custom silicon strategy for other AI companies?

OpenAI's investment in Cerebras sets a new competitive standard that other AI companies must contend with. Companies that aspire to compete on inference cost or latency now need their own hardware strategy. This creates several effects: first, it raises the capital barrier to entry in the inference market, making it harder for startups to compete with incumbents. Second, it creates urgency for other large AI companies to develop similar partnerships or build their own chips (Google with TPUs, Amazon with Trainium/Inferentia, Meta with custom silicon). Third, it benefits chipmakers that can support AI workloads, creating consolidation around specialized chip providers. Fourth, it pushes the market toward closed, proprietary infrastructure, reducing flexibility and increasing switching costs. Fifth, it advantages companies with strong engineering teams capable of deep hardware-software integration. For smaller companies and startups, the implications are sobering: competing on pure capability alone becomes insufficient if you can't also compete on efficiency. The market will likely consolidate around a few dominant platforms with integrated infrastructure stacks.

What role does custom software optimization play in making Spark successful on WSE-3?

Custom software optimization is as critical as the hardware itself. Cerebras provides the hardware and a software foundation (compiler, runtime system, libraries), but OpenAI's engineers must optimize specifically for Codex-Spark's workload and usage patterns. The compiler must map the model's computation graph onto WSE-3's architecture in ways that minimize memory movement and maximize compute utilization. The runtime must schedule concurrent requests fairly while maintaining latency targets. Libraries must be tuned for the specific operations that Spark performs most frequently. The model itself might be optimized for WSE-3 (through architecture changes, quantization, or distillation) to play to the hardware's strengths. All of this optimization work requires teams with deep understanding of both the algorithm and the hardware. The result is that two companies running the same model on WSE-3 could see dramatically different performance if one is better optimized than the other. For OpenAI, this represents a competitive advantage that's difficult for competitors to replicate without similar technical depth.

What manufacturing and supply chain challenges does Cerebras face in scaling to meet OpenAI's demand?

Manufacturing custom silicon at Cerebras' scale presents significant challenges. The WSE-3 uses an entire silicon wafer, which is unusual and creates manufacturing complexity. Wafer yields (the percentage of wafers that meet quality standards) might be lower than for smaller, more conventional chips, driving up effective cost. Cerebras depends on external fabs (Samsung and others) for manufacturing, competing with other companies for fab capacity. Advanced chip fabrication is constrained globally, and getting priority wafer allocation is competitive. Scaling production requires not just capital but also time: new manufacturing lines take years to build. If Cerebras can't deliver enough wafers on schedule, the partnership with OpenAI is limited by supply, not demand. Conversely, overinvestment in manufacturing capacity could leave Cerebras with excess capacity if other customers don't materialize. The company's recent $1 billion funding round suggests they're preparing to scale manufacturing aggressively. Success depends on execution: delivering wafers at acceptable quality, cost, and volume. Any failures here directly impact OpenAI's ability to scale Spark.

How does the real-time nature of Codex-Spark's latency requirement change the software architecture compared to batch-oriented inference systems?

Batch-oriented inference systems optimize for throughput, processing many requests together to maximize hardware utilization. You batch 100 requests into a single operation, process them together, and amortize overhead. This approach minimizes cost per request but increases latency for individual requests because each request waits for batching. Real-time systems like Spark must prioritize latency, limiting batch size to perhaps 10-20 requests to keep latency under 200ms. This means lower hardware utilization and higher cost per request, but it enables the interactive experience users expect. The architectural implications are significant: scheduling becomes more complex, request priority mechanisms are essential, memory management must be tighter to fit working sets on-chip, and fallback mechanisms become critical because system capacity is tighter. The tradeoff is explicit: lower utilization for lower latency. On WSE-3, the unified architecture makes this tradeoff more attractive than on traditional GPUs because the baseline overhead is lower, so even small batches can achieve reasonable efficiency. For OpenAI, accepting lower per-wafer utilization in exchange for latency is a worthwhile tradeoff because it enables the product experience that users value.

Key Takeaways

- OpenAI's $10B Cerebras partnership launches Codex-Spark, a lightweight model optimized for ultra-low 200ms latency through WSE-3's unified 4-trillion-transistor architecture

- Real-time inference demands architectural tradeoffs: smaller batches, lower hardware utilization, and sophisticated scheduling to maintain latency under variable load

- Hardware-software codesign is becoming table stakes for competitive advantage, raising capital barriers to entry and accelerating consolidation in AI infrastructure

- Cerebras' manufacturing challenges and fab capacity constraints are critical risks that could limit OpenAI's ability to scale Spark globally

- The strategy signals broader industry trend toward vertical integration, where companies control entire stacks from silicon to models rather than relying on commodity hardware

Related Articles

- Benchmark's $225M Cerebras Bet: Inside the AI Chip Revolution [2025]

- OpenAI Codex Hits 1M Downloads: Deep Research Gets Game-Changing Upgrades [2025]

- GPT-5.3-Codex: The AI Agent That Actually Codes [2025]

- WebMCP: How Google's New Standard Transforms Websites Into AI Tools [2025]

- OpenAI Disbands Alignment Team: What It Means for AI Safety [2025]

- OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads, Warns of 'Facebook' Path [2025]

![OpenAI's Codex-Spark: How a New Dedicated Chip Changes AI Coding [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/openai-s-codex-spark-how-a-new-dedicated-chip-changes-ai-cod/image-1-1770919726032.jpg)