Pentagon's $100 Million AI Drone Swarm Challenge: Why This Matters

The Pentagon just dropped something big. A $100 million prize. Voice-controlled drone swarms. And the fact that Elon Musk's SpaceX and xAI are actually competing in this thing.

Here's what's wild: This isn't some vague "maybe someday" military project. The Department of Defense has literally opened a six-month competition with real money attached. They're looking for teams that can build autonomous systems capable of translating spoken commands into coordinated actions across dozens, potentially hundreds of unmanned platforms operating simultaneously.

If you've been following defense tech, you know this has been theoretically possible for years. But there's a massive gap between what looks good in a demonstration and what actually works in a contested, GPS-denied battlefield. The Pentagon knows this. That's why they're throwing serious cash at the problem.

What makes this announcement actually significant isn't just the money. It's the timeline. Six months to prototype. The involvement of SpaceX and xAI. And the implicit acknowledgment that the US military believes swarm autonomy isn't optional anymore.

The geopolitical subtext is loud. China has been experimenting with drone swarms for years, as demonstrated in their rapid launch and agility swarm warfare tactics. Russia's been operating distributed attacks in Ukraine, highlighting the importance of autonomous systems in modern warfare. The US can't afford to fall behind on a technology that could fundamentally reshape how modern conflicts actually happen.

But here's the tension nobody's talking about clearly enough: Voice control sounds simple. "Drone swarm, attack that position." In reality, translating human language into coordinated autonomous action under fire, in jammed communications, with degraded sensors, is phenomenally complex. We're not talking about a speaker commanding a single intelligent system. We're talking about a single person's voice somehow coordinating decision-making across machines that need to operate independently because connectivity will inevitably fail.

This article breaks down what the Pentagon actually wants, what makes this technically hard, why SpaceX's involvement changes the equation, and what this means for the future of autonomous warfare.

TL; DR

- $100 Million Prize: Pentagon offering serious funding to teams that can demonstrate voice-controlled autonomous drone swarms within six months.

- SpaceX and xAI Competing: Elon Musk's companies are entering a competition explicitly focused on military autonomy, marking a shift in his stated AI safety priorities.

- Technical Complexity: True swarm autonomy requires decentralized decision-making, resilience to communications loss, and coordination without a single command center.

- Real Combat Application: Unlike previous aerial demonstrations, the Pentagon wants systems that work under electronic attack and GPS denial.

- Speed Matters: The six-month timeline signals urgency and suggests foundational tech may already exist, requiring integration and validation.

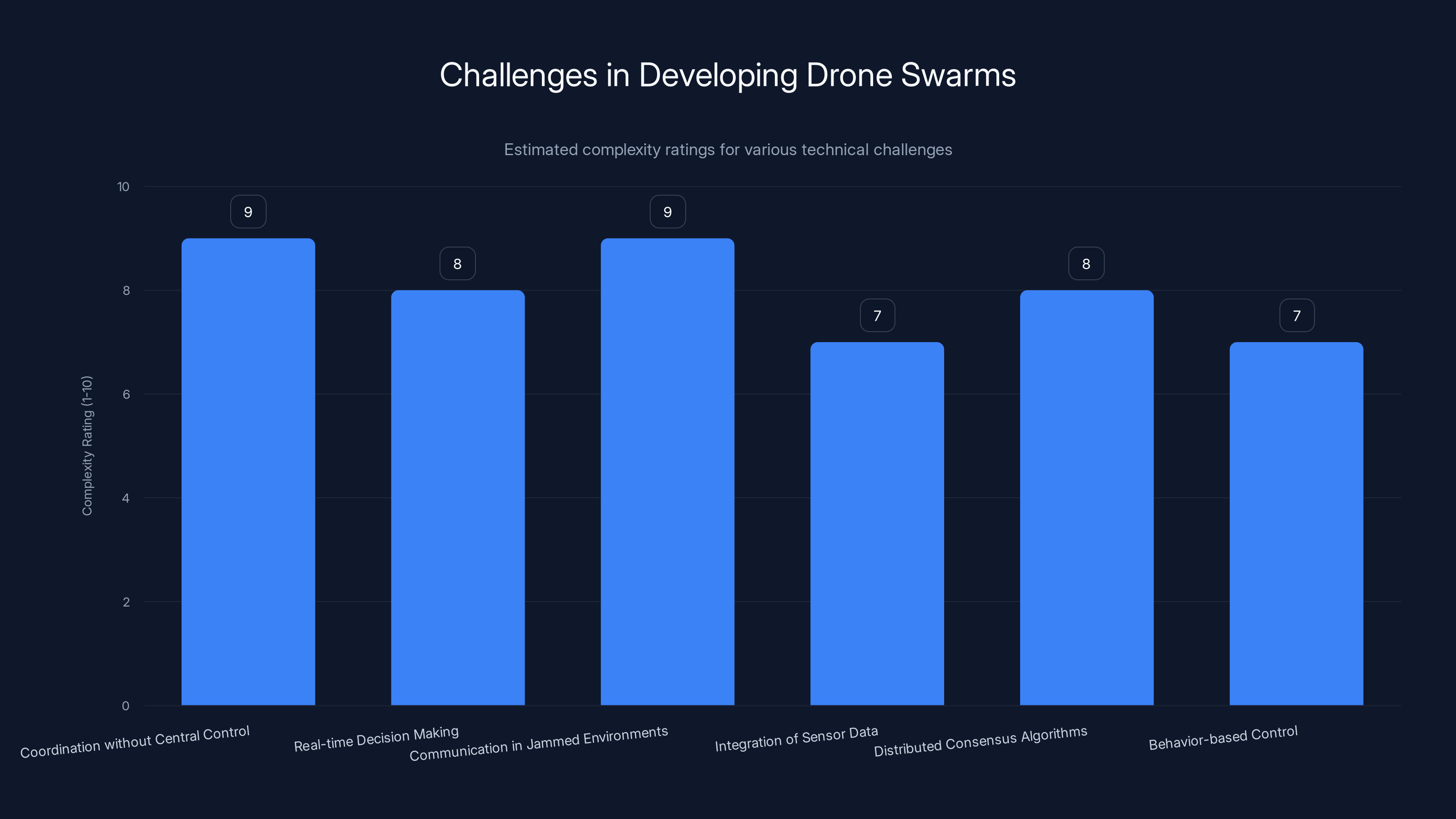

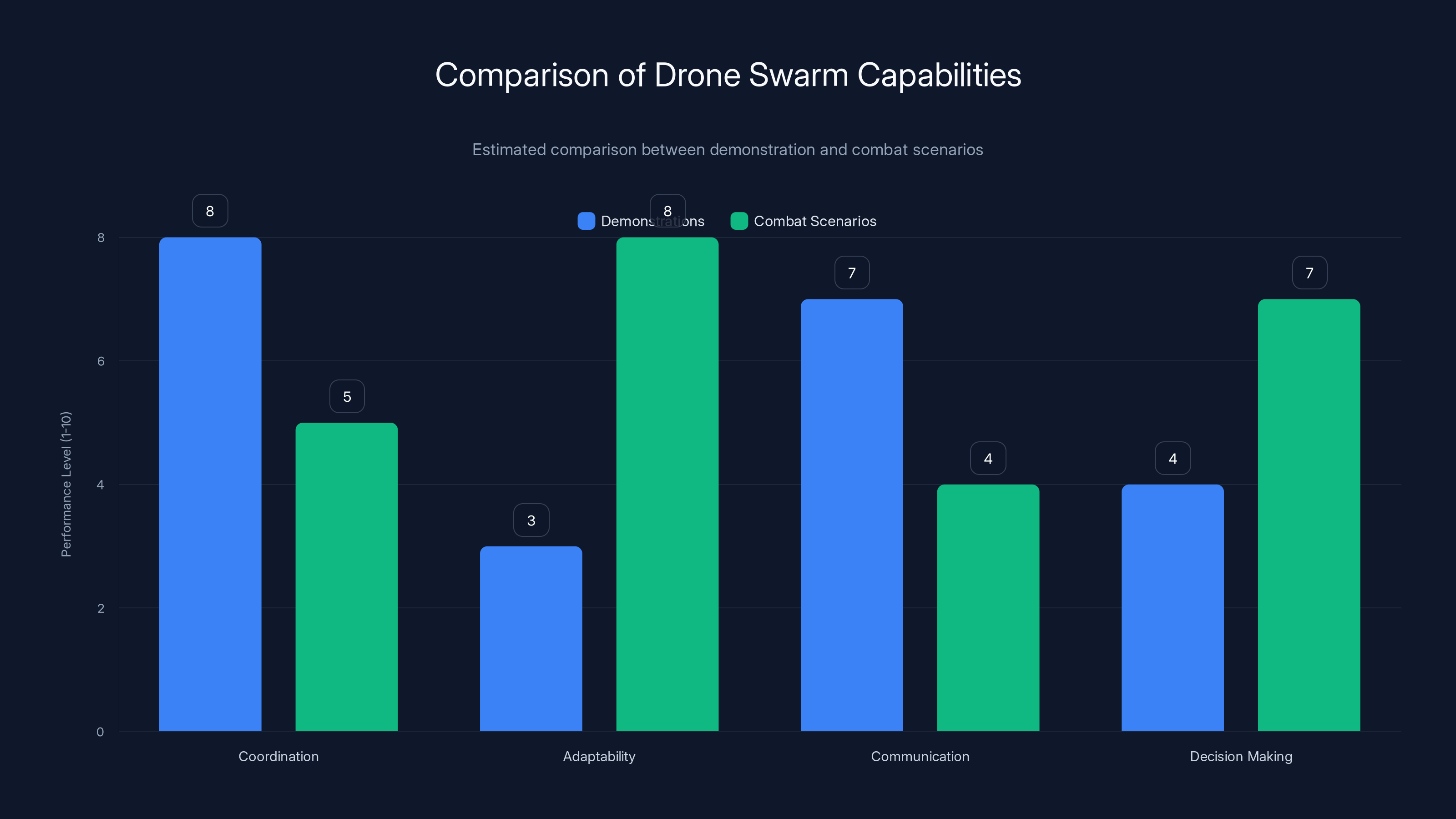

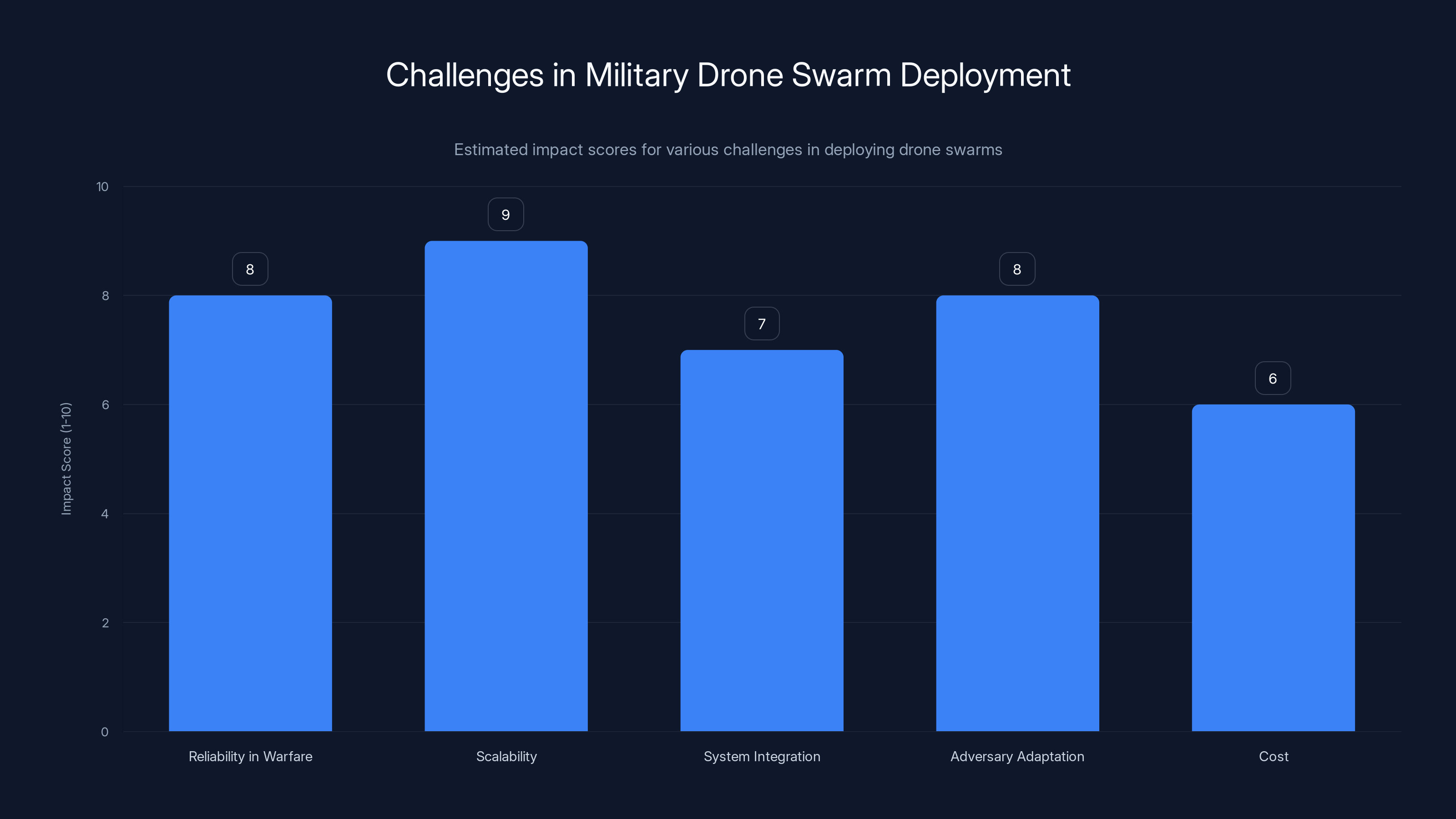

Coordination without centralized control and communication in jammed environments are among the most complex challenges in developing drone swarms. Estimated data.

What the Pentagon Actually Wants: Breaking Down the Challenge

The Pentagon's framing of this competition tells you a lot about military thinking right now. They're not asking for autonomous systems that might be useful someday. They're asking for something very specific: voice-controlled swarms that can operate effectively in contested environments.

The Defense Innovation Unit and the Defense Autonomous Warfare Group under US Special Operations Command are running this. That tells you this isn't just research theater. Special Operations Command means this is meant for actual deployment scenarios, not a decade-from-now think piece.

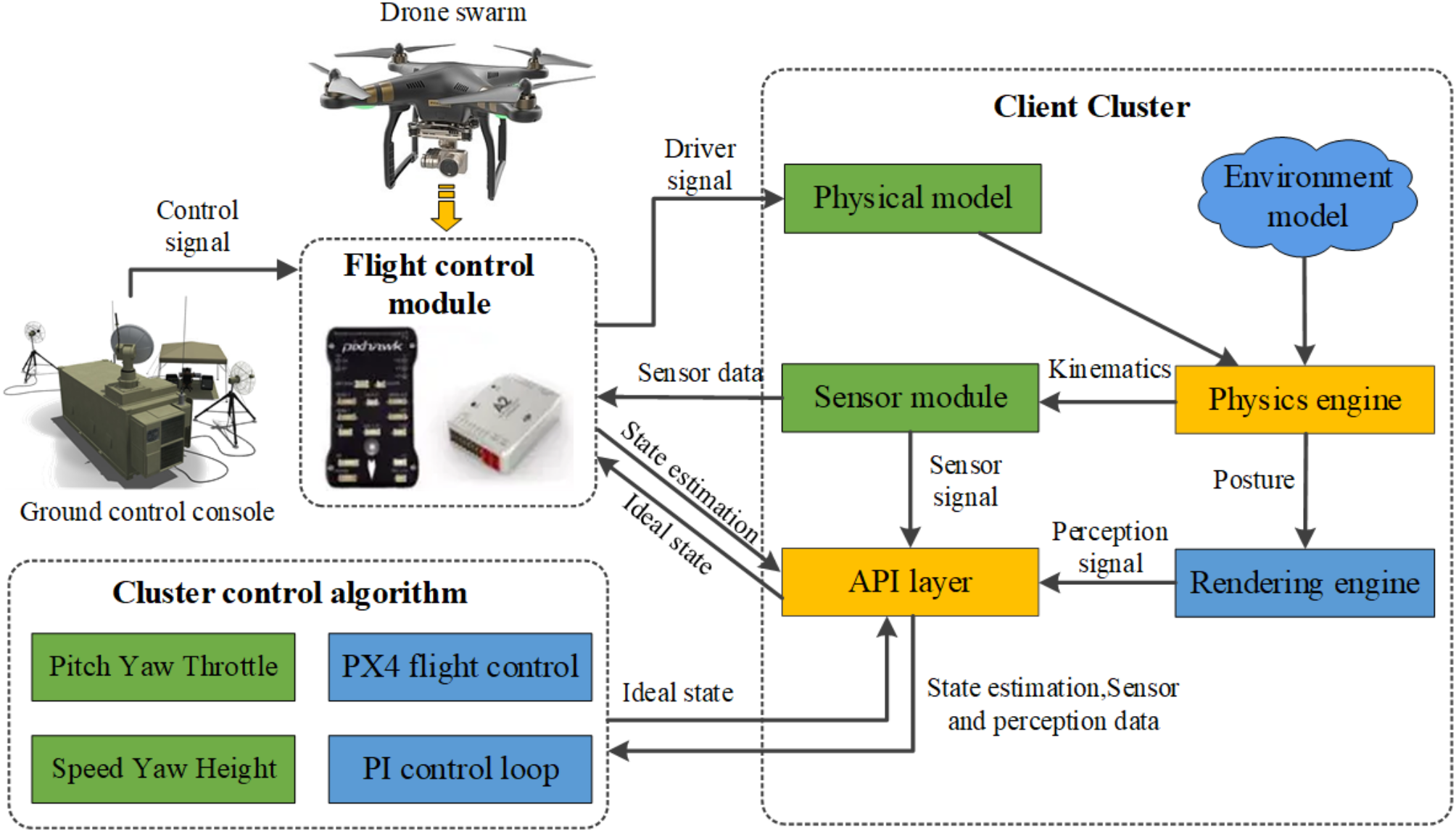

The core requirement is straightforward in concept, brutally hard in execution: translate spoken commands into coordinated autonomous actions across multiple unmanned systems operating together. That means a soldier or commander needs to be able to say something relatively simple, and dozens of drones automatically coordinate the response without further input.

But the real constraint is this: it has to work in environments where GPS is jammed, where radio frequencies are contested, where traditional command-and-control links break down. The Pentagon has seen what happens in modern conflicts. Ukraine showed that anything relying on consistent communications gets disrupted. China demonstrated drone swarms in controlled conditions. Russia's been experimenting with distributed attacks that don't depend on a single network.

So the competition isn't about proving swarms work theoretically. It's about proving swarms work operationally. Under pressure. Against active resistance.

The voice-control component is particularly interesting. It sounds like a user interface feature. It's actually a fundamental architectural requirement. When you're coordinating multiple autonomous systems via voice, you're essentially asking for natural language processing that can translate ambiguous human intent into precise tactical instructions that individual drones can interpret and act on independently.

That's different from what most drone systems do today. Current military drones are typically remotely piloted or follow pre-programmed routes. A swarm system needs to understand context, adapt to changing conditions, and make distributed decisions without a commander literally controlling each machine.

The stated objective is to move from software development to live testing within a structured, multi-phase framework culminating in operational demonstrations. In Pentagon terms, that means: prototype, validate, then show it working in something approaching realistic conditions.

Why Drone Swarms Matter for Modern Conflict

The concept of swarm robotics has been researched in academic labs for decades. You can find papers from the early 2000s discussing emergent behavior, distributed algorithms, and coordinated autonomous systems. Most of that research was theoretical or involved small-scale demonstrations.

What's changed is the military imperative. Modern conflicts have shown that centralized command-and-control is vulnerable. When you rely on a single communications link or a central processing node, you lose everything if that gets disrupted. Swarms work differently. Each unit operates autonomously but coordinates with nearby units. You lose some drones, the swarm adapts. You jam communications, the drones still function based on local information.

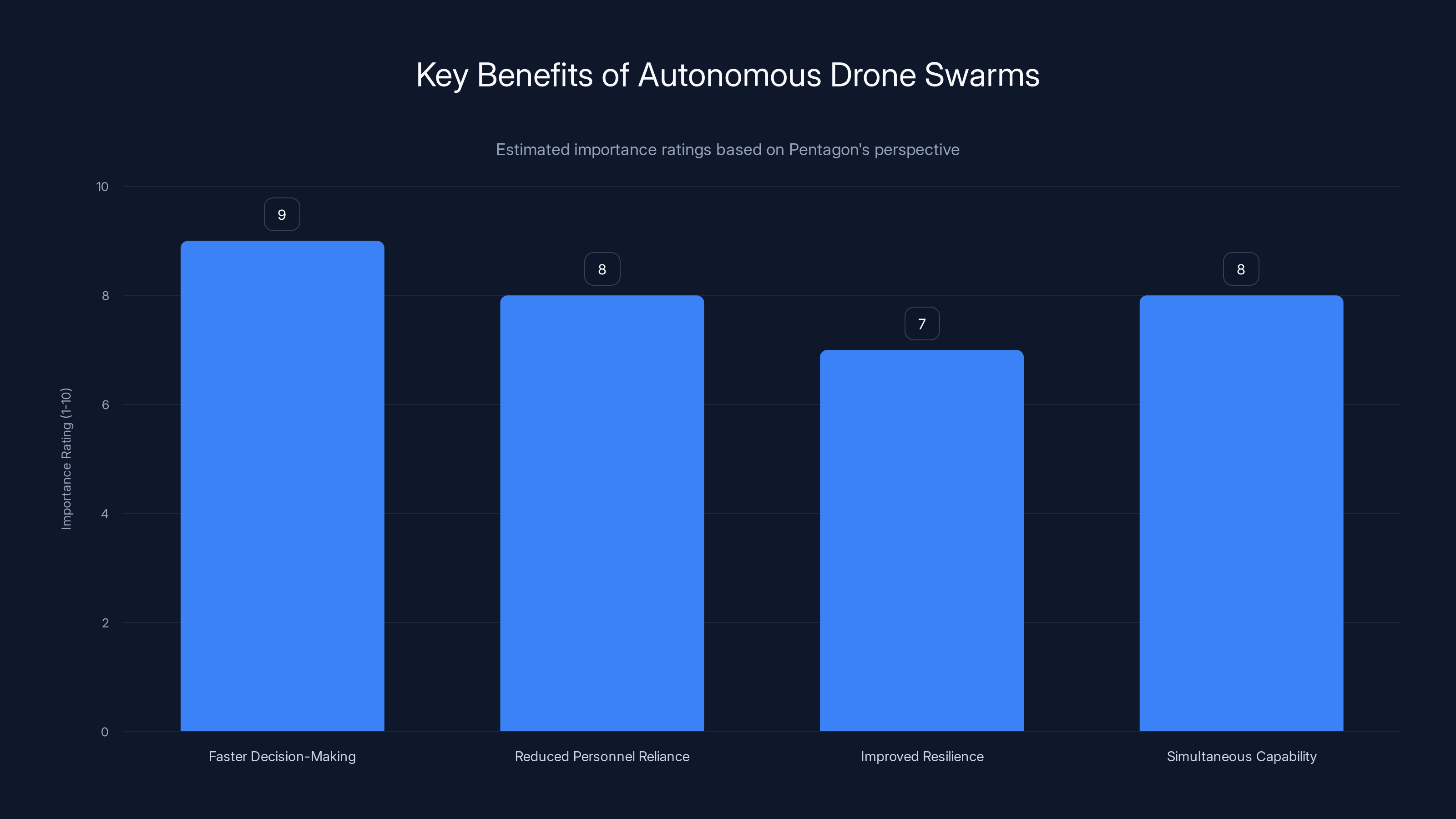

Consider what a military swarm could actually do. You're not just sending multiple drones at a target. You're creating a system where different drones have different roles. Some scout. Some jam radar. Some relay communications. Some execute strikes. A human commander gives one instruction, and dozens of machines automatically coordinate to execute a complex, multi-faceted operation.

The intelligence advantages are significant. A swarm can process sensory information from multiple perspectives simultaneously. It can adapt faster than a centralized system. It can be deployed at scale without proportionally increasing communications requirements.

But here's the reality check: demonstrations of drone swarms often looked more impressive than they actually were. Those elaborate aerial light shows? Mostly pre-programmed routes and centralized control pretending to be autonomous swarms. Real swarm behavior is messier, less synchronized, harder to make look good in a video.

True swarm autonomy requires each drone to share information with nearby drones, adapt to losses in real-time, and make distributed decisions without a single point of failure. That's technically different from what's usually been demonstrated. It's why the Pentagon is investing specifically in this challenge rather than just contracting with existing drone manufacturers.

The competition framework itself is revealing. A six-month timeline suggests the Pentagon doesn't think it's asking for something impossible. Teams are likely expected to build on existing autonomous flight platforms and focus on the swarm coordination layer. The innovation needed is in how drones communicate with each other and make distributed decisions, not necessarily in flight dynamics or basic autonomy.

Autonomous drone swarms are valued for their ability to enhance decision-making speed and operational resilience, with significant importance placed on reducing personnel reliance and enabling simultaneous capabilities. Estimated data.

SpaceX and xAI's Surprising Entry: What Changed?

Elon Musk has a documented history of expressing concern about AI systems being used for autonomous weapons. He's talked about the dangers of advanced AI being weaponized. He's publicly warned about AI risks. xAI was founded with emphasis on building safe, interpretable AI systems.

So when reports emerged that SpaceX and xAI are competing in the Pentagon's drone swarm challenge, it naturally raised questions. Was Musk changing his stance? Was this driven by commercial opportunity? Was there something about the program's structure that aligned with his stated values?

The most straightforward answer: SpaceX and xAI likely see this as a technical problem worth solving, independent of the military application. The challenge of coordinating autonomous systems, processing distributed information, and making real-time decisions is genuinely difficult engineering. For companies working on AI and robotics, this is essentially a high-stakes test of their systems.

There's also a practical consideration: if the Pentagon is going to pursue this technology anyway, having companies like SpaceX (with strong engineering talent and resources) competing might lead to better, safer solutions than if only traditional defense contractors were involved. That's not a bulletproof ethical argument, but it's the argument that companies like this typically make internally.

The competitive nature of the prize might also be significant. A $100 million government contract is substantial, but it's not unprecedented in defense tech. A competition, though, creates a different dynamic. Teams are incentivized to showcase actual capability rather than promise theoretical potential. SpaceX has a track record of pushing technical boundaries and delivering on ambitious timelines. xAI brings specialized AI expertise.

Musk's previous statements about AI safety still stand in tension with this decision. Fully autonomous weapons systems with minimal human control could reasonably be classified as an area he's expressed concern about. But the Pentagon's framing emphasizes voice control and human oversight. That might be the distinction Musk's team is leaning on: this isn't about removing human judgment from military decisions. It's about making human-directed autonomous systems more effective.

That said, the optics here are notable. Major tech leaders have increasingly faced scrutiny for involvement in military AI projects. The fact that Musk's companies are entering suggests either strong confidence in the technical and ethical positioning of the project, or perhaps a shift in how these companies evaluate military contracts.

The Technical Reality: Why Drone Swarms Are Harder Than They Look

Here's where the rubber meets the road. Voice-controlled autonomous swarms sound elegant in a mission statement. Actually building one that works under combat conditions is a different challenge entirely.

The fundamental problem is coordination without centralized control. In a traditional military operation, a commander gives orders to subordinates through a clear chain of command. Radio waves carry instructions from one person to many. If that commander is out of contact, everything defaults to the last known orders.

A true swarm can't work that way. Each drone needs to operate autonomously while remaining coordinated with nearby drones. Imagine dozens of unmanned systems all needing to share information, make decisions, and adjust tactics in real-time, with communications that might be jammed, delayed, or partially disconnected.

The algorithms required are complex. Each drone needs to:

- Maintain awareness of nearby units through limited-bandwidth communications

- Process its own sensor data (cameras, radar, thermal imaging, etc.)

- Integrate information from neighboring drones

- Decide on local actions that align with broader tactical objectives

- Adapt if communications with some neighbors is lost

- Handle the arrival of new orders that might contradict local information

That's not a solved problem. There are partial solutions. Distributed consensus algorithms can help drones agree on shared information even with some communications failures. Behavior-based control can allow drones to follow simple rules that create complex group dynamics. Artificial intelligence can train systems to recognize patterns and make decisions faster than traditional algorithms.

But integrating all of this so it works reliably under stress, in contested electromagnetic environments, with potential adversaries actively trying to disrupt it, is substantially harder than any of these pieces individually.

Consider the GPS denial aspect specifically. Modern military systems rely heavily on GPS for positioning, navigation, and timing. In a contested environment, GPS is often jammed. A swarm system needs to maintain tactical coordination without GPS. That means either relying on dead reckoning (which accumulates errors over time), using alternative positioning systems (like visual navigation or signal triangulation from known landmarks), or accepting reduced positional accuracy.

Each approach has tradeoffs. Visual navigation only works if there's usable imagery and sufficient lighting. Alternative positioning systems might not be available in all operational areas. Accepting reduced accuracy means the swarm's tactical precision decreases.

Then there's the communications layer itself. Traditional military communications use encrypted radio frequencies in specific bands. Adversaries can detect and jam these frequencies. A distributed swarm needs to either use highly resilient communications (which is hard to do with weight and power constraints on small drones), operate on frequencies adversaries might not jam (but those are often lower bandwidth), or accept that communications will occasionally fail and the swarm needs to function in a degraded state.

All of this happens while the swarm is trying to execute a mission and potentially operate in hostile environments where things are actively trying to kill it. That's the test the Pentagon wants to pass.

How Voice Commands Work in This Context

The voice-control requirement sounds straightforward until you actually think through the architecture. A soldier doesn't have time to write detailed technical specifications. They need to speak naturally: "Swarm, clear the area," or "Intercept that vehicle," or something equally vague by technical standards.

That natural language instruction needs to be parsed by a natural language AI system. The system needs to understand context (what area? which vehicle? what rules of engagement apply?). It needs to translate that into tactical objectives. Then it needs to communicate those objectives in a way individual drones can interpret and act on.

This is where xAI's involvement becomes relevant. xAI has been working specifically on AI interpretability and reasoning systems. The challenge of translating human language into executable autonomous behavior is something AI specialists care about deeply.

From a practical standpoint, the system probably doesn't try to parse arbitrary voice commands. More likely, there's a fixed vocabulary of commands that the voice recognition system listens for. "Clear the area" probably maps to a specific tactical formation and behavior set. "Hold position" maps to different behavior. The flexibility is in how the swarm interprets its current environment given those instructions, not in the swarm's ability to understand novel requests.

That's a more tractable problem. Instead of building a system that understands arbitrary human language, you're building a system that recognizes specific commands and executes pre-trained tactical responses. The AI challenge is in making those tactical responses work across varying environments and conditions.

The training process for such a system would be substantial. The AI models need to learn how to adapt tactical responses to environmental conditions. They need to recognize when their initial interpretation is wrong and adjust. They need to handle edge cases and unexpected situations.

All of this needs to work on hardware small enough to fit in a drone. Modern AI systems that can handle complex reasoning tend to be computationally expensive. Deploying that level of capability across multiple devices, each with limited power and processing capacity, requires significant optimization.

This is where SpaceX's involvement might be particularly relevant. SpaceX has deep experience building embedded systems that handle complex autonomy with limited computational resources. Rocket control systems, landing logic, precision guidance. The engineering patterns are different from military drones, but the fundamental challenge of doing sophisticated decision-making on constrained hardware is similar.

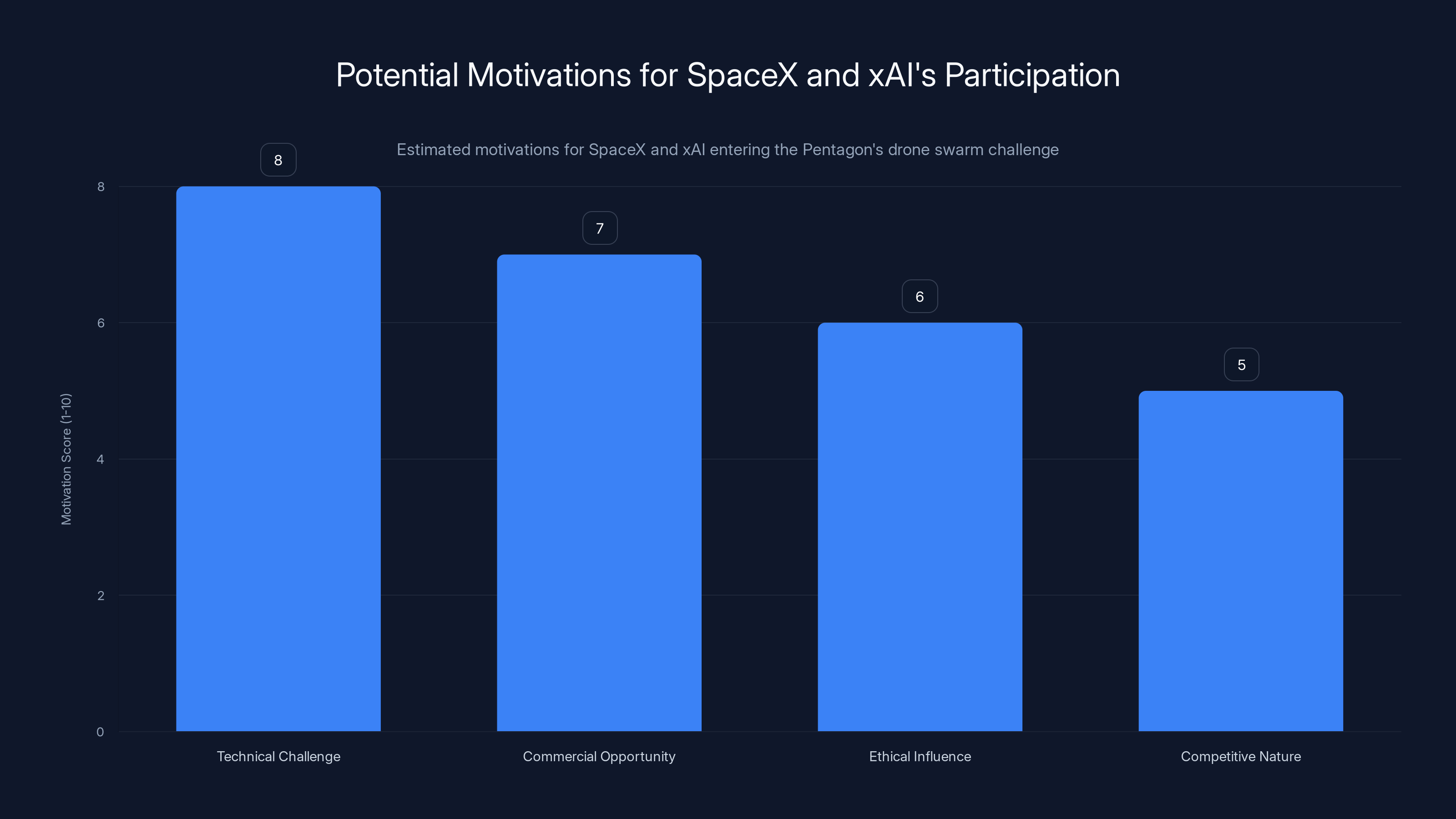

Estimated data suggests that technical challenge and commercial opportunity are primary motivators for SpaceX and xAI's participation in the Pentagon's drone swarm challenge.

Real Combat Autonomy vs. Demonstrations

Most public demonstrations of drone swarms have been impressive visually. Hundreds of small drones creating aerial light shows, flying in synchronized patterns, responding to simple controls. They look autonomous and coordinated. Technically, they usually are.

But combat is different. Combat involves uncertainty. It involves an adversary actively trying to disrupt your systems. It involves communication failures, sensor degradation, and time pressure. Demonstrations are often conducted in controlled airspace, with perfect weather, and with systems that have been extensively tested and debugged.

A military system needs to work on the first deployment, with limited prior testing, in conditions that might not match any training scenario. That's a different standard.

Consider what actually happens in combat operations. Electronic warfare includes active jamming of communications. Adversaries use decoys and false sensor inputs. The operating environment might include urban areas with complex 3D structures, weather that degrades sensor performance, or terrain that obscures positioning systems.

A swarm system needs to maintain coordination through all of this. Individual drones need to recognize when they've lost communications with nearby units and adapt accordingly. The swarm needs to continue executing its mission even if it's at partial strength. It needs to make good decisions with incomplete information.

That's substantially harder than what's usually demonstrated in controlled environments.

The Pentagon's decision to focus on a six-month timeline for operational demonstrations suggests they believe core autonomy algorithms are already sufficiently developed. The innovation they're seeking is in integration: taking existing autonomous flight platforms and existing AI systems and combining them in a way that creates effective military swarms.

That's faster than building everything from scratch, but it still requires substantial engineering. You need to integrate flight control systems with AI decision-making systems. You need communication layers that work with aerial platforms. You need testing and validation that the integrated system actually works.

The fact that multiple teams are competing is important. One team might achieve basic swarm functionality. Another might focus on resilience to communications failures. Another might prioritize rapid decision-making or effective targeting. Competition drives innovation and tests different approaches.

The Autonomous Warfare Debate: Legal and Ethical Dimensions

Drone swarms capable of autonomous action raise significant questions about the future of warfare and the role of human judgment in military decisions.

The Pentagon's emphasis on voice control and human involvement is relevant here. The official framing is that voice commands represent human control. A human is making the decision (attack, observe, maintain position), and autonomous systems are implementing that decision. That's different from fully autonomous weapons where the system decides both the objective and the method without human input.

But there's ambiguity in the space between these two extremes. A voice command like "clear the area" gives human intent but not specific tactical implementation. Individual drones in the swarm make real decisions about target identification and engagement. Is that human control or autonomous decision-making?

International humanitarian law hasn't definitively answered this question. There are ongoing debates at the United Nations about what should be required for human control to be "meaningful" in military systems. Different countries have different positions.

The fact that Elon Musk's companies are competing in this challenge might influence how that debate develops. If companies known for thinking about AI safety are involved in the program, it might create pressure to implement safeguards that purely military-focused contractors wouldn't.

There's also a deterrence angle worth considering. If the US successfully develops effective autonomous swarm systems, that capabilities signals to potential adversaries. It might encourage them to accelerate their own programs. Or it might deter them if they conclude the capabilities gap is insurmountable.

This is classic security dilemma dynamics. Each side wants to develop capabilities to deter others, but the process of developing those capabilities creates security pressure on other sides to develop their own capabilities, leading to arms race dynamics.

The ethical questions aren't resolvable at the technical level. They're policy questions. What authority should be responsible for deploying autonomous systems? What rules should govern their use? What human oversight should be required? These are questions for military leaders, policymakers, and international bodies to address.

But the technical community can influence how these systems work and what safeguards are built in. Systems designed from the ground up with safety and human control in mind will function differently than systems designed purely for effectiveness and then have safety constraints added afterward.

Historical Context: Where This Fits in Military Innovation

The Pentagon's push for autonomous systems isn't new. The military has been investing in robotics and autonomous vehicles for decades. From early mine-detecting robots to modern unmanned aerial vehicles, the trajectory has been toward more autonomy and less direct human control.

Early military drones were essentially remote-controlled aircraft. A pilot sat in a control center thousands of miles away and flew them like remote airplanes. That required continuous communications and constant attention.

Modern drones have autopilot systems. They can fly pre-programmed routes autonomously, follow targets autonomously, and make some tactical decisions autonomously. But they're still ultimately controlled by human operators who can intervene.

Swarms represent the next step: multiple autonomous systems coordinating to execute complex operations with minimal human intervention during execution. Instead of a pilot flying each drone, a commander gives one instruction and dozens of autonomous systems execute it.

This follows a pattern in military technology. Every new military capability has been developed by someone. Every major military technology has been deployed despite significant concerns about its implications. The question isn't usually whether a capability will be developed, but how it will be developed, by whom, and under what constraints.

The Pentagon's structured competition is actually one way to shape that development. By defining requirements clearly and inviting multiple teams to compete, the Pentagon influences what gets built. A well-designed competition can encourage innovation while also pushing teams toward solutions that meet specific requirements (like human control mechanisms).

That's different from a scenario where advanced militaries simply pursue autonomous systems without constraint, leading to arms race dynamics where safety gets deprioritized in pursuit of capability.

Estimated data shows that while drone swarms excel in coordination during demonstrations, their adaptability and decision-making capabilities are more critical and challenging in combat scenarios.

Technical Approaches Teams Likely to Use

Given the six-month timeline and the technical requirements, competing teams probably fall into a few categories in terms of approach.

One approach is consensus-based: drones communicate with neighbors and work toward agreement on shared objectives. Algorithms from distributed computing (like Byzantine fault tolerance) can help drones reach agreement even if some communications are unreliable. This approach emphasizes resilience but might sacrifice speed because reaching consensus takes time.

Another approach is behavior-based: each drone follows simple local rules that interact to create complex group behavior. A drone might have rules like "fly toward other drones but not too close" or "move toward the target but avoid obstacles." From simple rules, emergent behavior can arise. This approach is fast and robust but can be hard to predict and control precisely.

A third approach is hierarchical with distributed elements: drones work in small teams, and teams coordinate with other teams. A drone might have perfect communication within its immediate team but degraded communication beyond that. This creates natural fault lines and can make the system more resilient.

Most competitive systems probably combine elements of these approaches. The voice-control requirement suggests that there's still a command layer that receives human instructions and translates them into swarm objectives. The question is how that translates into distributed decision-making.

From an implementation perspective, teams need to address:

- Communication protocol: How drones share information, what format information is in, how bandwidth is managed

- Autonomy algorithm: How individual drones make decisions given local information and broader objectives

- Adaptation mechanism: How the swarm adjusts when communications fail or conditions change

- Integration with existing systems: How the swarm interfaces with broader military command structures and intelligence

- Testing framework: How to validate that the system works without conducting actual combat operations

The last point is important. Pentagon teams will need to demonstrate capability in controlled tests that reasonably approximate combat conditions. That might involve GPS jamming, simulated communications interference, obstacles, and time pressure.

Comparing Approaches: Technical Tradeoffs

Different team approaches will involve different technical tradeoffs. Understanding these helps explain why the Pentagon runs a competition rather than just contracting with one prime contractor.

Consensus-based approaches prioritize reliability and resilience. The swarm explicitly handles the case where some drones lose communications or fail. The algorithms are well-understood from distributed computing research. The downside is that reaching consensus is slow. In time-critical situations, a swarm that achieves rapid agreement might be better than one that makes very reliable decisions slowly.

Behavior-based approaches prioritize speed and simplicity. Individual drones don't need to process complex state information about the whole swarm. They follow local rules. This reduces communications and processing load. The downside is that controlling the swarm precisely is harder. You might get emergent behavior that's unexpected. Predicting how the swarm responds to new commands requires simulation.

Hierarchical approaches prioritize scalability. You can have a thousand drones organized into teams of ten, with teams organized into larger units. Communications can be optimized within each level. The downside is that this requires more structure, and structure can create failure modes if something disrupts the hierarchy.

Teams also need to consider hardware. Drones capable of carrying meaningful payloads while maintaining swarm coordination need adequate processing power. That requires either more capable drones (which are more expensive) or more efficient algorithms (which are harder to develop).

Battery life is another constraint. A drone that runs out of power is useless. Continuous communication drains batteries. Complex local computation drains batteries. The engineering involves balancing capability with power consumption.

Weather and environmental conditions create additional constraints. Drones fly in wind, which affects aerodynamics. Rain can degrade sensors and communications. Dust or smoke can reduce visibility. Real-world testing needs to account for realistic environmental conditions, not just laboratory conditions.

The Timeline Problem: Why Six Months Is Aggressive

The Pentagon specified a six-month competition timeline. That's aggressive by defense standards, where programs routinely take years from concept to deployment.

The timeline suggests either that foundational technology is already in place, or that the Pentagon is willing to accept a less mature final product in exchange for faster initial capability demonstration. Probably some combination of both.

Teams aren't starting from scratch. Commercial drone platforms already exist with autonomous flight capability. AI models for distributed decision-making have been researched. The integration challenge remains, but existing components can accelerate development.

However, six months is short for:

- System design and architecture: Figuring out how components integrate

- Implementation and debugging: Building the actual code and systems

- Testing and validation: Confirming the system works as intended

- Operational testing: Demonstrating capability in realistic conditions

Typically, each of these phases takes months. Compressed timelines require:

- Parallel work: Multiple teams working on different components simultaneously, with good integration practices to avoid rework

- Technical debt acceptance: Using existing solutions rather than building optimal solutions from scratch

- Risk acceptance: Being willing to proceed with some unknowns rather than fully characterizing the system

- Pre-existing capability: Building on proven components rather than inventing from first principles

The Pentagon's framing suggests they expect the winning entry to be a prototype that demonstrates the core capability, not a fully production-ready system. Subsequent phases (if any) would involve refinement and optimization.

This matters for understanding what SpaceX and xAI likely need to deliver. They're not expected to build a fully robust military system in six months. They're expected to demonstrate that their approach to coordinating autonomous systems works and can be scaled.

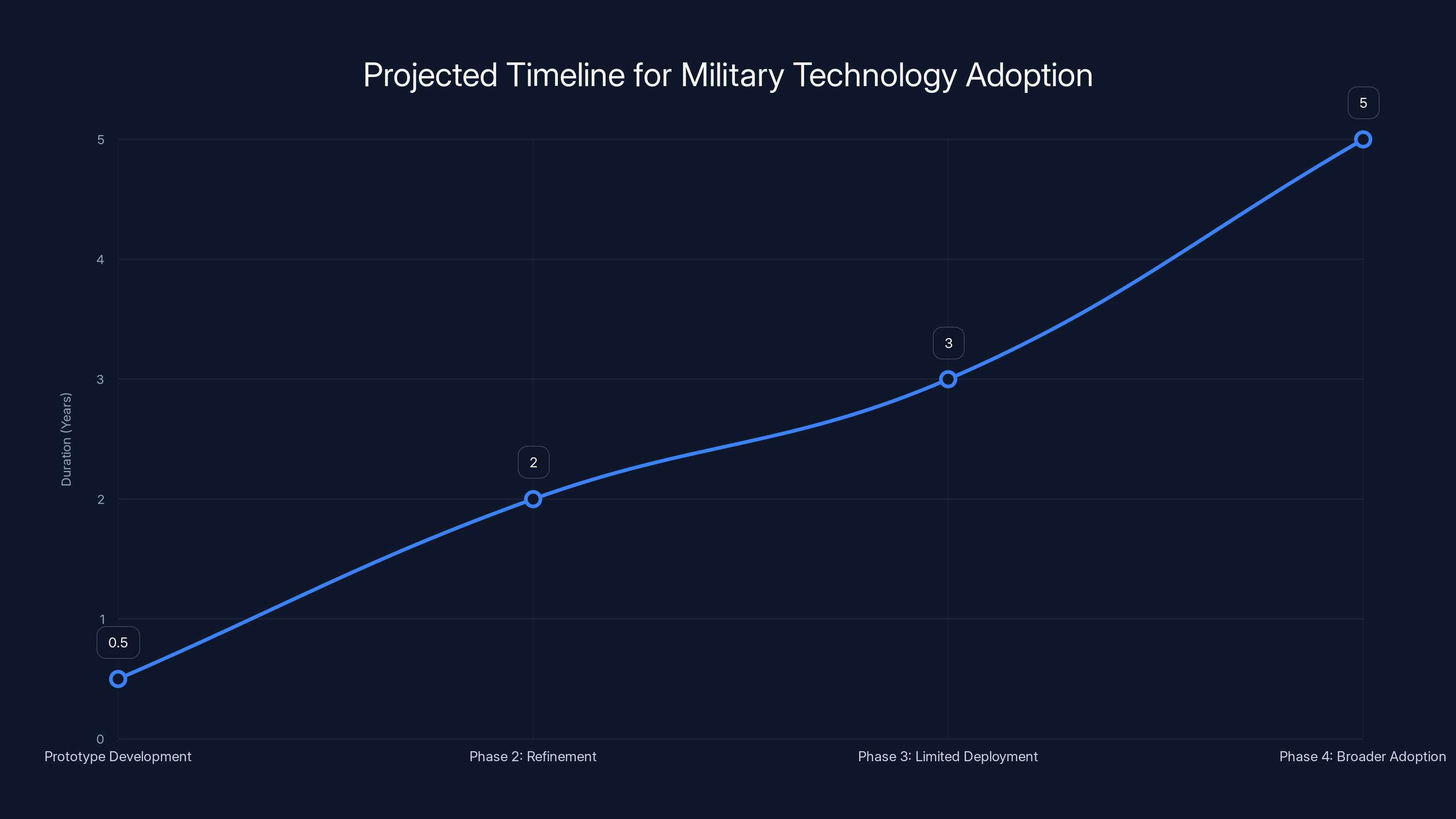

Estimated timeline shows that full adoption of military technology could take up to 5 years post-prototype, reflecting the slow pace of military integration compared to commercial sectors.

What This Means for the Defense Tech Industry

The Pentagon's competition will likely accelerate development of autonomous swarm technology regardless of the immediate outcome. Competitors spend resources developing solutions. Ideas get tested. Technical challenges get identified and addressed. The broader field advances.

For defense contractors, this competition creates pressure to engage with autonomy technology. Traditional defense companies that focus on building platforms (aircraft, ships, vehicles) might need to develop capability in autonomous systems or partner with companies that specialize in AI and robotics.

For commercial robotics and AI companies, military applications represent both opportunity and risk. Opportunity: substantial funding and urgent requirements can drive technical advancement. Risk: involvement in military projects brings scrutiny and potential controversy, as evidenced by the ongoing debates around tech company involvement in defense work.

The involvement of SpaceX and xAI signals that major commercial AI and space technology companies see military autonomy as strategically important. That attracts competitors. Traditional prime contractors like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Boeing have autonomous systems programs. Specialized robotics companies have relevant capability. The Pentagon's competition will filter these into winners and losers.

Long-term, effective swarm technology could reshape military procurement. Instead of buying a single expensive platform, militaries could buy swarms of smaller, cheaper, more expendable platforms. That changes economics and shifts which companies have advantage.

International Context: Arms Race Dynamics

The Pentagon isn't pursuing autonomous swarms in a vacuum. China and Russia are also working on swarm technology.

China has publicly demonstrated drone swarms with hundreds of units. The demonstrations have been impressive, though (like most public demonstrations) they might not represent true autonomous combat capability. China's investment in autonomous systems is substantial, with both military research and commercial applications driving advancement.

Russia's approach has been somewhat different, focusing on integrating autonomous capabilities into existing military platforms rather than building swarms from scratch. Ukraine's experience with Russian military AI systems suggests Russia is actively testing these capabilities in real conflict.

The US military's concern about falling behind is probably genuine. In an arms race dynamic, being second matters. The first country to deploy effective autonomous swarms gains advantage. Other militaries then face pressure to deploy their own versions.

This arms race dynamic creates pressure to advance quickly, which can suppress safety considerations. When military leaders believe an adversary is close to deploying a capability, they become less patient about testing and validation. This is how arms races typically escalate: each side feels threatened by the other's progress and accelerates their own development, which triggers further acceleration by competitors.

The international dimension also affects what other countries do. If the US successfully deploys autonomous swarms, that signals what's possible and what military leaders should prioritize in their own countries. If deployment goes badly (e.g., autonomous systems behave unpredictably in combat), that might slow international adoption.

Future Trajectory: What Comes After This Competition

Assuming the Pentagon competition succeeds in producing a functional prototype, the next steps would likely involve:

Phase 2: Refinement and Operational Testing: Taking the winning prototype and refining it based on testing results. This typically involves identifying edge cases, improving reliability, and adapting the system to work with existing military command structures. This phase usually takes 1-2 years.

Phase 3: Limited Deployment: Testing the system in limited operational deployments with real military units. This might mean actual deployment in ongoing operations (like counter-terrorism missions) or elaborate war games that simulate combat conditions. This helps identify real-world issues that testing environments didn't capture.

Phase 4: Broader Adoption: If limited deployment succeeds, expanding the system to more military units. This involves production scaling, personnel training, integration with logistics systems, and all the infrastructure needed to deploy a new military capability at scale.

Each phase takes time and requires significant additional investment. A successful prototype emerging from the six-month competition doesn't mean autonomous swarms will be deployed widely in the next couple of years. Military procurement and integration moves slower than technology development.

But the trajectory is clear. The Pentagon sees this as important. They're investing. They're creating pressure through competition. They're likely to continue funding regardless of short-term results.

From a strategic perspective, the Pentagon is betting that autonomous swarm technology will be as important to future warfare as aircraft were to warfare in the 20th century. That's a big bet. Whether it's correct depends on whether swarm technology actually delivers on its promise in real operational environments.

But even if swarms don't become the dominant military platform, the research and development triggered by this competition will advance autonomy, AI, robotics, and distributed systems generally. Some of that technology will find civilian applications. Some will influence how other military capabilities develop.

That's how military innovation often works. The military drives development of capabilities it thinks it needs. The technology gets fielded. Some of it becomes important. Some of it doesn't. But the broader technological landscape is shaped by what got developed and how.

Scalability and reliability in warfare are the most significant challenges, each scoring high on the impact scale. Estimated data.

Practical Implications for Military Operations

If autonomous swarms work as intended, how would they actually change military operations?

Tactically, swarms could enable operations that aren't practical with current systems. Instead of sending one manned aircraft with a crew, you could send a swarm of autonomous drones. Some hunt for targets, some provide electronic warfare, some provide communications, some execute strikes. The swarm adapts to what it finds and how adversaries respond.

This makes military operations faster. Instead of a complex decision-making and approval process before each action, a commander gives broad intent and autonomous systems execute tactical details. In environments where speed matters, that's significant advantage.

Operationally, swarms could reduce pilot workload. Instead of a pilot flying each drone, a commander monitors and directs swarms. One person can effectively command more capability. This addresses one of the constraints of current unmanned operations: there are only so many pilots available, so the number of drones you can field is limited by available personnel.

Swarms could also improve survivability. No single platform is critical. If you lose some drones, the swarm continues operating. This is different from a large, expensive platform where losing it is catastrophic.

But there are also potential complications. Autonomous systems might behave unexpectedly in novel situations. Control might prove difficult despite voice-command interfaces. Adversaries will develop countermeasures. Integration with existing military structures might be harder than technology development.

Real military capability requires more than just working technology. It requires training personnel to use the technology effectively, integrating it into command structures, developing tactics that exploit the technology's advantages, and defending against adversary countermeasures.

Challenges and Unknowns

Despite the Pentagon's investment and SpaceX's involvement, significant uncertainties remain.

Proven reliability in contested environments: We don't actually know if swarms can maintain coordination under active electronic warfare. Demonstrations in controlled conditions are insufficient. Only real-world testing (or elaborate simulations) can confirm actual capability.

Scalability: Current demonstrations involve dozens or hundreds of drones. Military operations might need thousands. Scaling algorithms and systems that work for hundreds might not work for thousands. Communication overhead, processing requirements, and coordination complexity all scale nonlinearly.

Integration with existing systems: Military command structures, intelligence systems, and logistics are complex. Integrating autonomous swarms requires not just building the swarms but building interfaces and decision procedures that connect them to existing military infrastructure. This is unglamorous engineering work that often takes longer than developing the core capability.

Adversary adaptation: Once swarms are deployed, adversaries will develop countermeasures. Electronic warfare, physical countermeasures, or tactics that exploit swarm limitations. The technology advantage is temporary. Staying ahead requires continuous advancement.

Cost: While swarms of small drones are cheaper than large manned platforms, they're not free. Producing thousands of combat drones requires substantial industrial capacity and cost. The overall cost of a swarm operation (including logistics, training, maintenance) might not be as favorable as single-platform comparisons suggest.

Why This Matters Beyond the Military

The Pentagon's focus on autonomous swarms shapes broader technology development and raises questions relevant beyond military applications.

Autonomous systems are becoming common in civilian applications: self-driving cars, delivery drones, warehouse robots, industrial automation. Military systems drive development in some areas (sensing, robotics, AI) that filter into civilian applications over time. Understanding how the military approaches autonomous systems and what safeguards they build can inform civilian applications.

Conversely, civilian technology development influences what's possible militarily. AI advances in the private sector become available to military researchers. Commercial drone platforms can be adapted for military use. The boundary between civilian and military technology is porous.

The economic implications are significant. Companies that win this competition gain credibility and likely additional military contracts. They also gain experience developing autonomous systems at scale. That experience might transfer to civilian applications.

The geopolitical implications are broader. How the US develops autonomous weapons influences how other countries develop their own capabilities. If the US emphasizes human control and safety mechanisms, that might become standard internationally. If the US develops systems with minimal human control, that signals to others that such systems are militarily acceptable.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead

The Pentagon's $100 million drone swarm competition represents a significant acceleration in military autonomy development. SpaceX and xAI's participation signals that major commercial tech companies see this as strategically important.

The technical challenges are substantial. Creating truly autonomous systems that coordinate effectively without a central point of control, operate reliably under electronic attack, and execute complex missions under human command, requires solving hard problems. The six-month timeline suggests the Pentagon believes these problems are addressable, but the results will reveal what's actually possible.

From a defense strategy perspective, the competition makes sense. Autonomous swarms could reshape future warfare. Being first to deploy effective swarms creates military advantage. Being last creates vulnerability. The arms race dynamic is real.

From a technology perspective, the competition will accelerate advancement in AI, robotics, autonomous systems, and distributed computing. Some of that technology will find civilian applications. Some will simply advance the frontier of what's possible.

From a policy perspective, questions about human control, autonomous weapons, and the role of AI in military decision-making remain unresolved. The competition proceeds while those policy debates continue. That's typical of military innovation: technology advances while policy catches up.

What's clear is that autonomous swarms are no longer theoretical. The Pentagon is investing in making them real. Teams of talented engineers are working to solve the hard problems. Within six months, we'll see what that investment and effort produces.

The implications will extend far beyond military applications. How this technology develops will influence not just warfare, but the broader trajectory of artificial intelligence, robotics, and autonomous systems generally.

FAQ

What is an autonomous drone swarm?

An autonomous drone swarm is a coordinated group of unmanned aircraft that operate together without a centralized command authority controlling each individual drone. Each drone makes decisions independently based on local information and coordination with nearby drones, creating emergent group behavior. Unlike traditional drone operations where a single pilot controls one or multiple drones through direct commands, swarms operate with distributed decision-making where the system collectively executes broader tactical objectives.

How does voice control work with drone swarms?

Voice control in drone swarms translates spoken human commands into tactical objectives that individual drones interpret and execute autonomously. A commander might say "clear the area," and the swarm automatically coordinates to execute that mission without further input. The system uses natural language processing to recognize specific voice commands, translates those commands into system-level objectives, and then distributes relevant sub-objectives to individual drones that coordinate their actions to accomplish the goal. This differs from direct teleoperation where a pilot would manually control each drone.

Why does the Pentagon think autonomous swarms are important?

The Pentagon sees autonomous swarms as potentially transformative for military operations because they enable faster decision-making, reduce reliance on personnel to operate individual platforms, improve resilience to losses, and allow commanders to direct more capability simultaneously. Swarms can coordinate complex operations that would be difficult for traditional platforms. Additionally, peer competitors like China and Russia are developing swarm technology, creating pressure for the US to develop comparable capabilities to maintain military advantage.

What makes swarm coordination technically difficult?

Swarm coordination is technically difficult because drones need to maintain awareness of nearby units with limited communications bandwidth, make local decisions that align with broader objectives despite incomplete information, adapt when communications fail, and process sensor data from multiple sources in real-time. In contested environments where adversaries actively jam communications and degrade sensors, achieving reliable coordination becomes exponentially more complex. Add to this the requirement to operate under GPS denial and in environments where traditional command-and-control links break down, and the problem requires solving multiple hard problems simultaneously.

Could autonomous swarms be deployed within the next few years?

Depending on how the Pentagon competition proceeds, limited deployment of swarm technology could occur within a few years for testing purposes. However, widespread military adoption typically requires years of refinement, operational testing, integration with existing military systems, and personnel training. A prototype demonstrated in six months could take 2-5 additional years to become a deployable military capability. True operational prevalence across multiple military branches would likely take longer.

What are the risks of autonomous military swarms?

Risks include unexpected autonomous behavior in novel situations, potential for misuse or escalation, challenges in maintaining meaningful human control, adaptation by adversaries to counter swarm tactics, and the possibility that systems behave differently in real combat than in testing environments. Additionally, there are strategic risks related to arms race dynamics where development of swarm technology by one country triggers accelerated development by others, and policy questions about autonomous decision-making in warfare remain unsettled despite technical advances.

Why is SpaceX's involvement significant?

SpaceX's involvement is significant because the company has expertise in building embedded systems that handle complex autonomy under resource constraints, strong engineering talent, and resources to invest in rapid prototyping. Additionally, Elon Musk has previously expressed concern about AI being used for autonomous weapons, so SpaceX's participation represents either a shift in perspective or a distinction in how the company views human-controlled autonomous systems versus fully autonomous weapons. The involvement also signals that major commercial tech companies see military autonomy as strategically important, which might influence technology development priorities.

How does this compare to other countries' swarm technology development?

China has publicly demonstrated drone swarms with hundreds of units and has made substantial investment in autonomous systems research. Russia has been integrating autonomous capabilities into existing military platforms and testing these systems in actual operations in Ukraine. The US competition reflects concern about falling behind these peer competitors in swarm technology development. The arms race dynamic is real: each country perceives threats from others' progress and accelerates their own development accordingly.

What is the realistic timeline for this technology reaching military units?

A realistic timeline would involve: six months for competition and prototype demonstration (Pentagon's timeline), 1-2 years for refinement and initial operational testing, 1-2 years for limited deployment and evaluation, and potentially 3-5 years for broader adoption across military units. However, these timelines can compress if results are promising or extend if unexpected challenges emerge. True operational prevalence across the military would likely take 5-10 years from initial prototype demonstration.

Advanced Integration Concepts

Building on the competition framework, future iterations of swarm technology will likely involve increasingly sophisticated integration with military systems. Autonomous swarms won't operate in isolation. They'll integrate with manned platforms, ground forces, and strategic-level command structures. The technical challenge involves bridging the gap between tactical autonomy (what individual swarms do) and strategic human decision-making (what broader military objectives drive swarm deployment).

This requires standardized interfaces, common operational pictures that humans can understand, and decision support systems that help commanders direct autonomous swarms effectively. It's unglamorous infrastructure work that determines whether the technology actually gets used effectively in real military operations.

The Broader Landscape of Military AI

The drone swarm competition is one piece of a broader Pentagon initiative to accelerate AI adoption across military systems. The Pentagon has also announced programs focused on AI for planning, logistics, intelligence analysis, and targeting. These programs collectively represent a bet that AI will reshape military advantage.

That's a multi-billion dollar bet spanning years. The drone swarm competition is high-profile because swarms are conceptually interesting and raise important questions about autonomous weapons. But in the total portfolio of military AI investment, it's one program among many.

Understanding this context helps explain the urgency and investment level. The Pentagon isn't excited about drone swarms in isolation. It's excited about AI capabilities generally and sees swarms as one application where those capabilities could be particularly transformative.

Note: This article represents analysis of the Pentagon's drone swarm competition and the involvement of major technology companies. Technology development timelines and military adoption are subject to substantial uncertainty. The actual trajectory of autonomous swarm technology will depend on technical breakthroughs, policy decisions, international dynamics, and factors that can't be predicted with confidence.

Key Takeaways

- Pentagon's $100 million competition seeks voice-controlled autonomous drone swarms that coordinate without centralized control.

- SpaceX and xAI's participation signals major tech companies view military autonomy as strategically important.

- True swarm coordination requires solving hard problems: distributed decision-making, GPS-denied operation, resilience to jamming.

- Six-month timeline suggests existing autonomy technology can be integrated rather than invented from scratch.

- Arms race dynamics with China and Russia create urgency driving military autonomy development priorities.

Related Articles

- AI Defense Weapons: How Autonomous Drones Are Reshaping Military Tech [2025]

- AI Safety vs. Military Weapons: How Anthropic's Values Clash With Pentagon Demands [2025]

- AWS 13-Hour Outage: How AI Tools Can Break Infrastructure [2025]

- How an AI Coding Bot Broke AWS: Production Risks Explained [2025]

- Pentagon vs. Anthropic: The AI Weapons Standoff [2025]

- AI Apocalypse: 5 Critical Risks Threatening Humanity [2025]

![Pentagon's $100M AI Drone Swarm Challenge: SpaceX's Bold Bet [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/pentagon-s-100m-ai-drone-swarm-challenge-spacex-s-bold-bet-2/image-1-1771621846328.jpg)