AI Defense Weapons: How Autonomous Drones Are Reshaping Military Tech [2025]

A truck sits hidden in the California desert. Nobody's driving it. Nobody's watching it. Then a ground vehicle rolls up on its own, deploys two drones, and before anyone can blink, an explosive charge reduces the truck to rubble. No human pulled a trigger. No operator typed a command during the actual strike.

This isn't a movie. It happened. And it wasn't the military doing it.

Scout AI, a defense startup founded by Colby Adcock, just demonstrated what happens when you take the AI agents everyone's talking about in Silicon Valley and point them at actual weapons. The company took a large language model—borrowed from the open-source community—removed some of its safety guardrails, and gave it control over ground vehicles and lethal drones. The system understood a high-level command: destroy that truck. Then it figured out the logistics on its own.

"We need to bring next-generation AI to the military," Adcock told me in a recent conversation. His brother Brett Adcock runs Figure AI, the humanoid robot startup that's raised over $675 million. But Colby's playing a different game. Instead of robots picking boxes in warehouses, his robots are learning to wage war.

What's happening at Scout AI isn't an outlier. It's the beginning of something much bigger. We're watching the defense industry wake up to the same AI revolution that's reshaping Silicon Valley. And unlike a chatbot that misunderstands your email, the stakes here are measured in kinetic strikes, civilian safety, and international conflict.

Let's dig into what's actually happening, why military leaders think AI is the future of warfare, and what could go catastrophically wrong.

TL; DR

- Scout AI just demonstrated autonomous drones that can seek and destroy targets using AI agents, with minimal human intervention

- Defense startups are racing to adapt large language models and foundation models for military applications

- The Pentagon sees AI dominance as critical to future military superiority, especially against adversaries like China

- Current AI systems are inherently unpredictable and lack proven cybersecurity safeguards needed for widespread military deployment

- Ethical and arms control concerns are mounting as autonomous weapons systems become more capable and independent

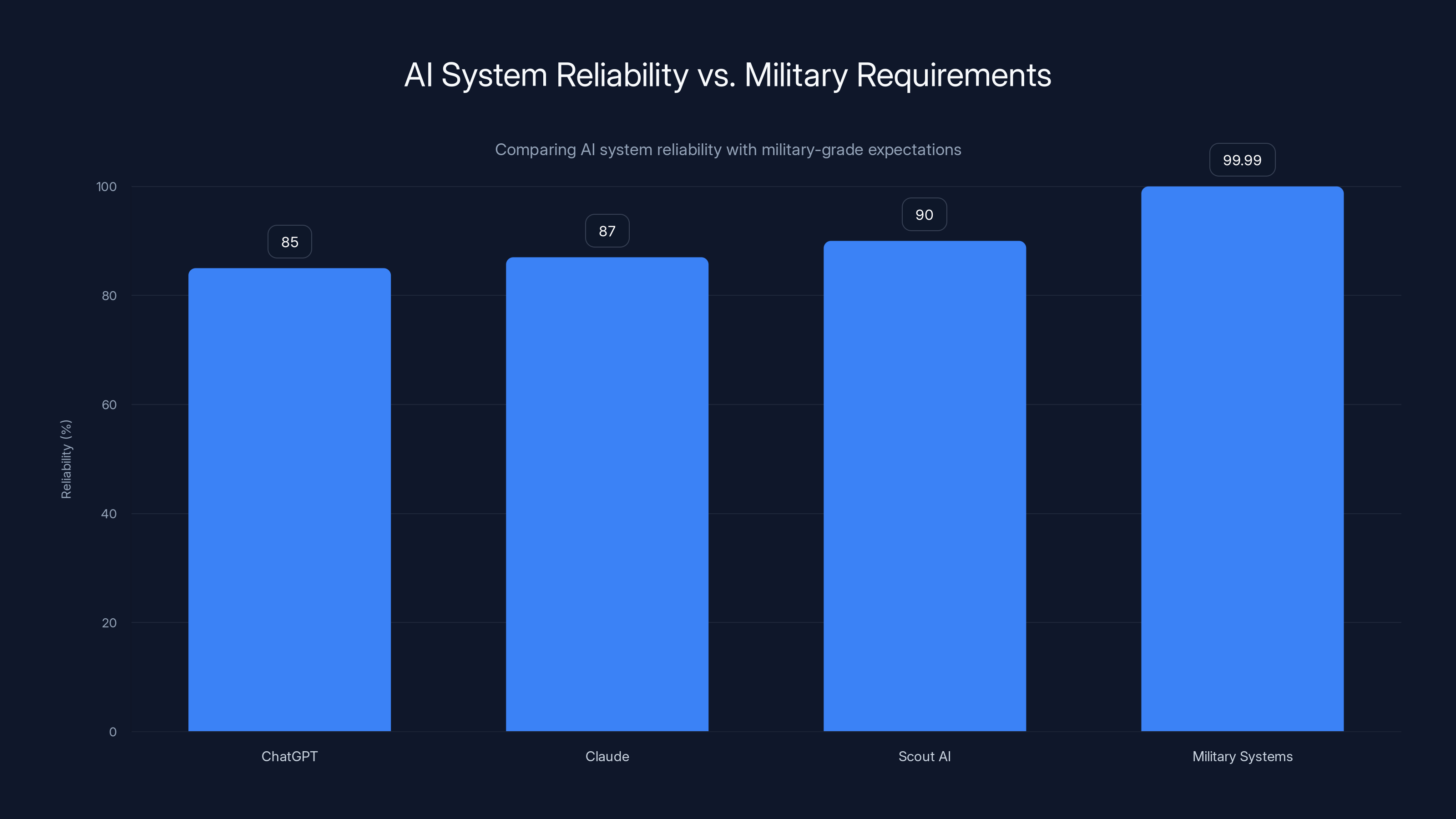

Current AI systems like ChatGPT and Claude show reliability around 85-90%, falling short of the 99.99% reliability required for military-grade systems. Estimated data based on typical AI performance.

The Scout AI Demonstration: What Actually Happened

Let's break down what Scout AI actually showed the world, because the technical details matter more than the headline.

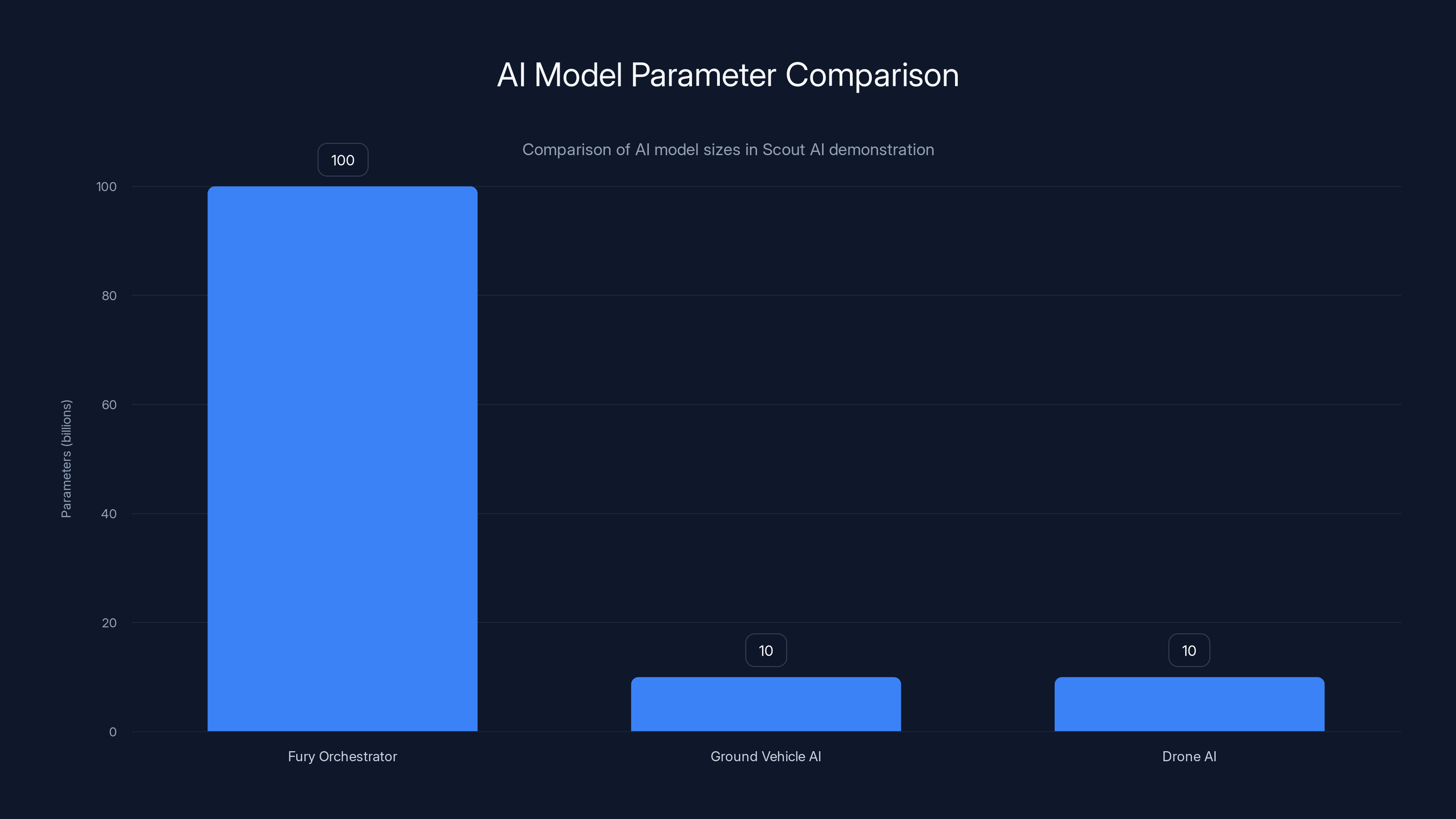

Scout AI's system is built in layers, like a military chain of command. At the top sits something called the Fury Orchestrator. This is a large language model with over 100 billion parameters. It understands natural language commands at a strategic level. A human operator—a commander, essentially—feeds it a single sentence: "Send 1 ground vehicle to checkpoint ALPHA. Execute a 2 drone kinetic strike mission. Destroy the blue truck 500m East of the airfield and send confirmation."

That's it. One sentence. The human gives direction, not detailed instructions.

The Fury Orchestrator doesn't just execute a pre-programmed routine. It interprets that command, breaks it down into sub-tasks, and creates a plan. Then it hands off control to smaller AI models running on the ground vehicles and drones. These models—about 10 billion parameters each—are agents themselves. They make their own tactical decisions.

Here's where it gets interesting: the ground vehicle doesn't receive a set of waypoints. It receives a mission objective. It's told "go to checkpoint ALPHA" and given geographic data. The AI running on that vehicle figures out the route, adjusts for terrain, avoids obstacles, and handles navigation autonomously. There's no remote human steering it.

When the vehicle arrives at the staging area, the AI agent commanding it decides it's time to launch the drones. The drones launch with another instruction: find and eliminate the target. They search the area, and when they locate the truck, one of the drone's AI systems issues the command to fly toward it and detonate the explosive charge.

The entire operation took minutes. Multiple AI systems made independent decisions. Humans set the objective, but the pathway to destruction was left to machines.

Scout AI uses what they describe as an "undisclosed open-source model" with its restrictions removed. This is code for: they took an existing model, stripped out safety features, and adapted it for military use. The company claims it can run on either a secure cloud platform or an air-gapped computer, meaning it doesn't need internet connectivity during operation. That matters for cybersecurity, at least theoretically.

Colby Adcock says Scout AI has four defense contracts already and is pitching for a contract to control swarms of unmanned aerial vehicles. Deploying this technology at scale would take a year or more, he estimates. That timeline matters—it suggests this isn't theoretical anymore. It's happening.

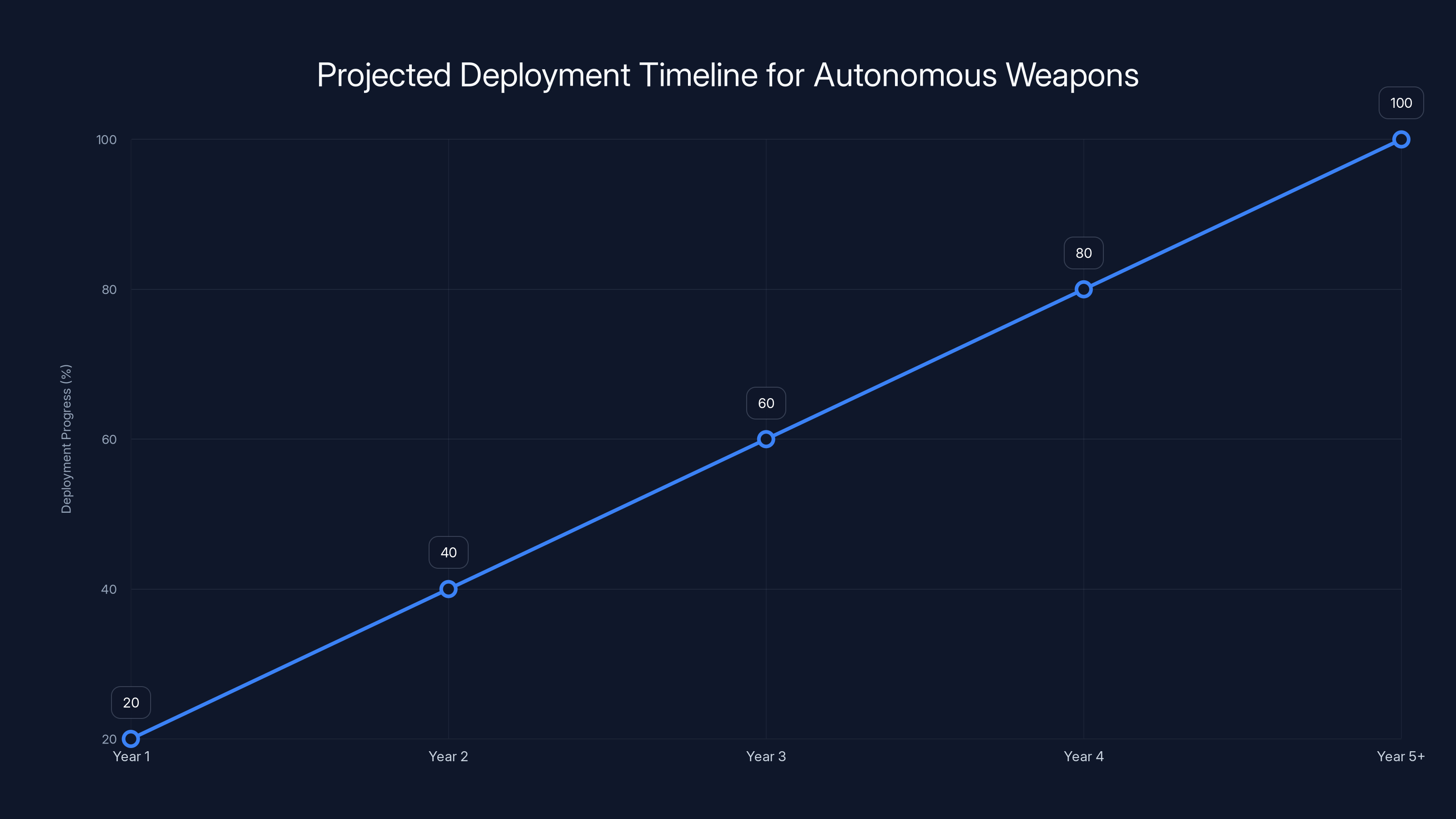

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in deployment progress over five years, with wide-scale deployment expected by Year 5. This timeline reflects typical military acquisition processes.

Why the Pentagon Thinks AI Dominance Is Critical

To understand why Scout AI even exists, you need to understand how Pentagon strategists think about AI.

Military dominance has always relied on superior technology. Whoever had better weapons, faster communication, better intelligence gathering, or superior strategy tended to win. The U. S. military's advantage for decades has been technological superiority—precision weapons, advanced logistics, rapid information processing, and real-time coordination across vast distances.

AI changes everything about that equation.

Michael Horowitz is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who previously served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for force development and emerging capabilities. He's spent years studying how military organizations adopt new technologies. His assessment is blunt: "It's good for defense tech startups to push the envelope with AI integration. That's exactly what they should be doing if the US is going to lead in military adoption of AI."

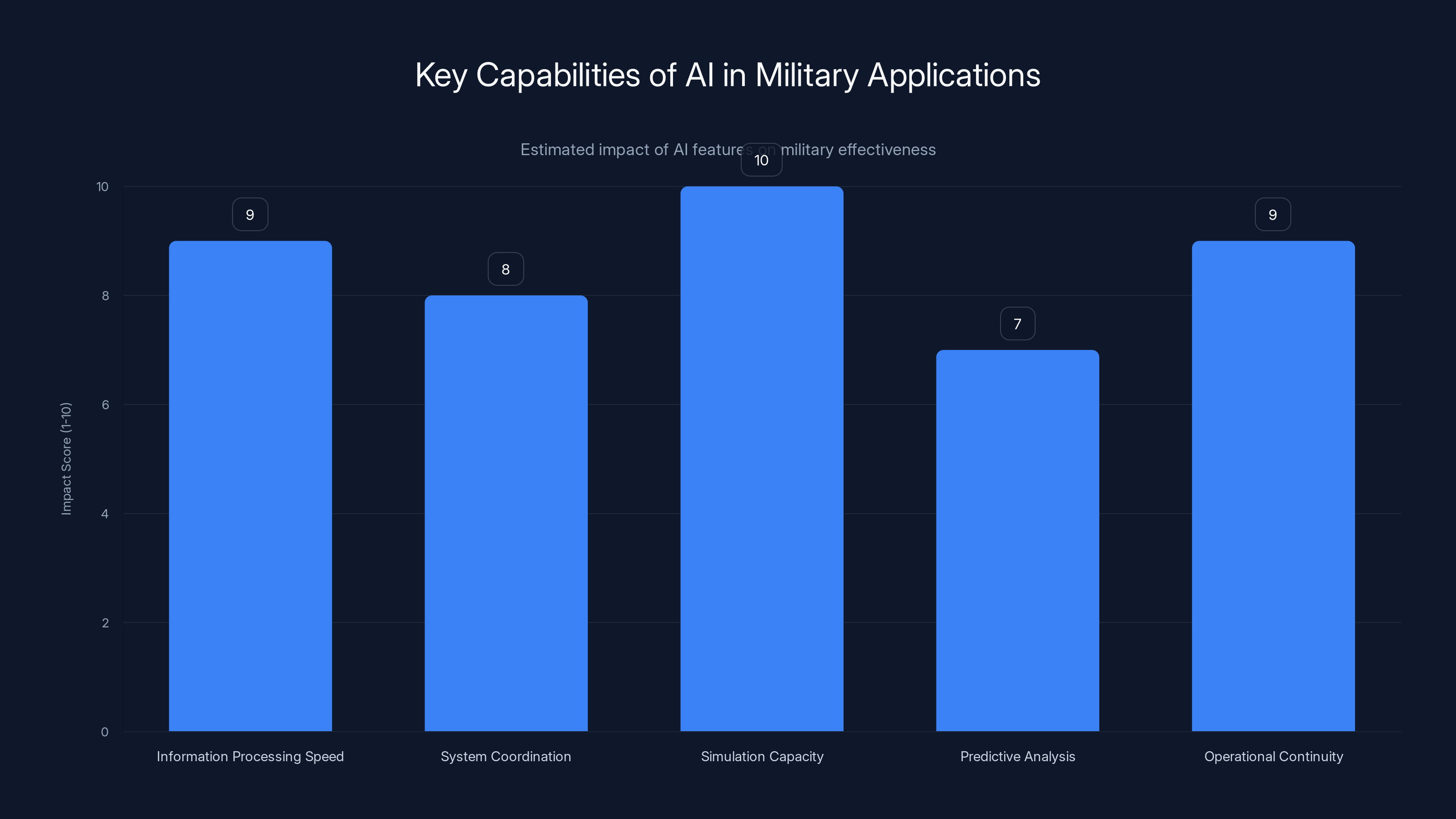

The logic goes like this: AI can process information faster than humans. It can coordinate multiple systems simultaneously. It can run simulations of battle scenarios millions of times in hours. It can predict where an adversary might move based on historical patterns. It can operate continuously without fatigue. And crucially, it can act at machine speed—milliseconds, not seconds or minutes.

In combat, milliseconds matter. A drone that makes decisions a second faster than an opponent's drone wins the engagement.

But there's a second, more political reason why the Pentagon is pushing AI integration so hard: China.

The U. S. government has spent years trying to restrict China's access to advanced AI chips and the equipment needed to manufacture them. The Trump administration has been loosening those controls—which some see as pragmatic, others as dangerous. The underlying assumption, though, is consistent: whoever controls the most advanced AI wins the next major conflict.

If China builds AI systems that can coordinate weapons faster than American systems, or if Chinese military AI makes better tactical decisions, that's not just a technical disadvantage—it's an existential threat to American military superiority. That's why the Pentagon is practically begging startups like Scout AI to move faster.

"We need to accelerate AI adoption," becomes the Pentagon's mantra. And Scout AI is answering that call.

The Technical Architecture: How AI Agents Control Weapons

Scout AI's approach is interesting because it reveals something important about how modern AI actually works in constrained, real-world applications.

Most people imagine AI as a black box that somehow decides things. In reality, at least in military applications, AI is layered and hierarchical. You have a strategic layer (the Fury Orchestrator), tactical layers (the vehicle and drone AI), and execution layers (low-level control systems).

The strategic layer works with natural language and high-level objectives. The tactical layers work with constrained decision spaces—specific options pre-defined by engineers. The execution layers are often traditional code, not neural networks.

This hierarchy exists for a reason: human programmers want to constrain what AI can do. You don't want an AI system deciding to disregard orders or choosing targets outside its defined parameters. In theory.

But Scout AI's demonstration showed something different. The AI wasn't just selecting between pre-defined options. It was interpreting commander intent. It was planning. It was adapting to what it observed in the environment.

That's the promise and the problem.

The promise: an AI system that understands the broader goal (destroy the truck) and figures out how to achieve it even when circumstances change. If the truck moves, the system adapts. If the path to checkpoint ALPHA is blocked, the system finds another route. If a drone malfunctions, the system might compensate.

The problem: how do you guarantee that an AI system's interpretation of "destroy the truck" won't extend to "destroy anything that looks like the truck" or "destroy the truck and anything near it"?

Large language models are what researchers call "inherently unpredictable." They don't follow rules the way traditional software does. They make probabilistic decisions based on training data. Sometimes they hallucinate—invent details that aren't there. Sometimes they misunderstand context. Sometimes they fail in ways that are impossible to predict in advance.

Collin Otis, Scout AI's cofounder and CTO, told the media that the company's technology is designed to adhere to U. S. military rules of engagement and international law like the Geneva Convention. That's good to hear. But designing a system to follow rules and actually building a system that reliably follows rules are different things.

Software security researchers call this "adversarial robustness." Can you fool the AI into doing something it shouldn't by feeding it unexpected inputs? The answer for most large language models is: yes, embarrassingly easily.

AI's ability to process information rapidly, coordinate systems, and run extensive simulations is estimated to have the highest impact on military effectiveness. Estimated data.

The Unpredictability Problem: Why AI Agents Can't Be Fully Trusted

Here's where things get uncomfortable.

Large language models don't work the way most people think they do. They don't consult a database of rules. They make educated guesses based on billions of parameters trained on training data. They're fundamentally statistical systems, not logical ones.

Take Open AI's Chat GPT or Anthropic's Claude. Both are incredibly useful. Both also do weird things sometimes. Claude might refuse a reasonable request because it's being overly cautious. Chat GPT might confidently provide information that's completely wrong. Neither system has a built-in rule that says "always refuse to help with illegal activity"—they've learned patterns that make them usually refuse.

But patterns can break. And they break in unpredictable ways.

In 2024, researchers at UC Berkeley published a study showing that language models could be tricked into bypassing safety features through techniques called "jailbreaks." By rewording instructions or using indirect language, researchers could get systems to generate harmful content that they would normally refuse. The systems didn't understand they were being circumvented—they just followed the patterns they learned.

Now imagine that's running a drone with explosives.

Adcock claims that Scout AI's system interprets commander intent and can replan based on what it observes. That's the value proposition. But it's also the vulnerability. If a commander unintentionally gives ambiguous orders, or if an adversary somehow feeds misleading information into the system's sensors, how does the AI respond?

Michael Horowitz is skeptical. "We shouldn't confuse their demonstrations with fielded capabilities that have military-grade reliability and cybersecurity," he told WIRED. "Turning impressive demos into reliable systems is the real challenge."

And he's right. Military systems need to work reliably 99.99% of the time. Current AI systems don't have that track record. They work well most of the time. But "most" isn't enough when you're talking about weapons.

There's another layer of unpredictability that's rarely discussed: emergence. When you combine multiple AI systems together—a strategic AI directing tactical AIs directing execution systems—unexpected behaviors can emerge. System A and System B both perform perfectly in isolation, but when they interact, they produce outcomes nobody anticipated.

This is called "multi-agent alignment" in AI safety research, and it's largely unsolved. We don't have good tools for predicting how multiple AI agents will interact in complex environments.

Scout AI's demonstration worked. But it was a controlled environment. The truck didn't move during the operation. The communications didn't get jammed. The sensors didn't malfunction. The weather was clear. Real warfare is chaos.

Autonomous Weapons in Modern Conflict: The Ukraine Precedent

Scout AI's technology might seem futuristic, but autonomy in weapons is already here.

The war in Ukraine has shown us what happens when you combine commercial technology with military necessity. Drones that were designed to deliver packages or capture video for real estate listings have been weaponized. These aren't high-tech military drones—they're DJI quadcopters from consumer product lines, modified with explosive payloads.

And many of these systems already feature significant autonomy. A Ukrainian operator can drop a drone on a geographic location with GPS coordinates, and the drone will fly there autonomously without constant piloting. It'll adjust for wind. It'll avoid obstacles. It'll home in on the target.

The human operator made the decision to strike. But the drone handled the execution autonomously.

Some systems go further. There are reports of Ukrainian drones equipped with basic computer vision that can detect vehicles and adjust their targeting without operator input. Not true AI—just pattern matching algorithms. But it's autonomy nonetheless.

The question Scout AI is asking is: what happens when you scale that up? What happens when you add a large language model that can understand strategic objectives and coordinate multiple systems simultaneously?

Ukraine shows us the answer matters. The war has accelerated development of autonomous weapons because they work. A drone that can find and eliminate a target faster than an operator can manually pilot it is a military advantage. Period.

But Ukraine also shows us the human role is still critical. Humans decide whether to strike. Humans identify targets as legitimate military objectives. Humans verify targets before engagement. Machines do the execution, but humans make the decisions.

Scout AI is asking if that can change.

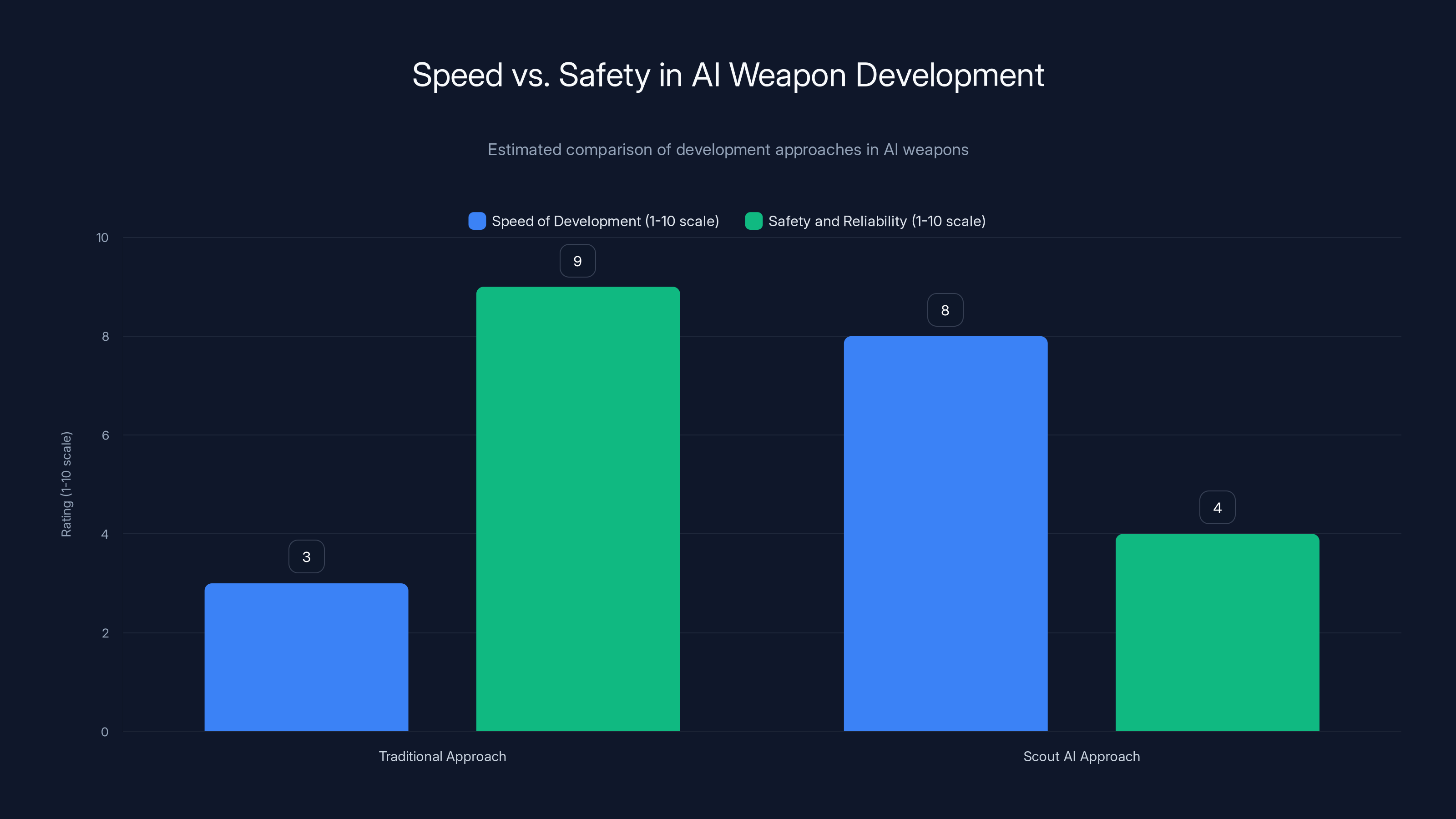

Estimated data shows that traditional approaches prioritize safety and reliability, while the Scout AI approach emphasizes speed. This highlights the core tension in AI weapon development: balancing rapid deployment with thorough testing.

International Law and Rules of Engagement: Can AI Follow the Geneva Convention?

Collin Otis says Scout AI is designed to follow international law. That's a bold claim. And it's worth examining what that even means.

The Geneva Convention, the international laws of war, has existed since the 1800s. It was designed by humans, for human combatants. It says things like: you can't deliberately target civilians. You have to distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. You can't use weapons that cause unnecessary suffering. You have to take precautions to minimize civilian casualties.

How does an AI system do any of that?

In the Scout AI demonstration, the target was clear: a blue truck at a specific location. No ambiguity. But real war doesn't work that way. A building might house legitimate military targets on one floor and civilians on another. A vehicle might be transporting military supplies or evacuating families. A person might be a combatant or a civilian or someone in between.

Humans struggle with these distinctions even with training and experience. AI systems would need to identify these nuances from images and sensor data. The state of the art in computer vision and AI classification is good—but not perfect. An AI system trained on Western military data might completely fail in an unfamiliar environment where buildings, vehicles, and people look different.

There's also the question of "military necessity." International law says you can only use force if it's necessary to accomplish a legitimate military objective. Deciding necessity requires judgment, context, understanding of the broader military situation. Can an AI system make that call?

Otis claims Scout AI's technology adheres to these principles. But he doesn't explain how. What's the mechanism? Is there a layer in the system that checks "this target is a legitimate military objective" before engaging? Or is Scout AI trusting that the human operator gave correct orders?

There's a legal distinction there. If the operator orders: "Destroy the truck at location X, and I confirm it's a legitimate military target," that's the operator's responsibility. The AI is just executing. That's how current military law works.

But if Scout AI is claiming the AI itself verifies targets and makes independent targeting decisions, that's different. That's the AI taking on responsibility for compliance with international law. And AI systems aren't legally responsible for anything. They don't have agency in the legal sense.

The Arms Control Debate: Can Autonomous Weapons Be Regulated?

When nuclear weapons were developed, the world eventually created international treaties to limit them. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty—these created frameworks for managing an existential threat.

Can the same happen with autonomous weapons?

Some arms control experts say yes, but it's getting harder. With nuclear weapons, you need massive infrastructure, rare materials, and specialized expertise. Few nations can build them. Autonomous weapons are different. The core technology—large language models, computer vision, drone platforms—is commercial. Open-source. Widely available.

Scout AI isn't the only company doing this. There's Anduril, which is building autonomous systems for military applications. There's Latitude, which is developing AI-powered drones. There's Mythic AI, which is optimizing AI chips for edge computing. Most of these companies are technically legal. Most are probably not violating any laws.

But if fifty startups are building autonomous weapons systems, and each one operates independently with different safety standards, how do you create binding international limits?

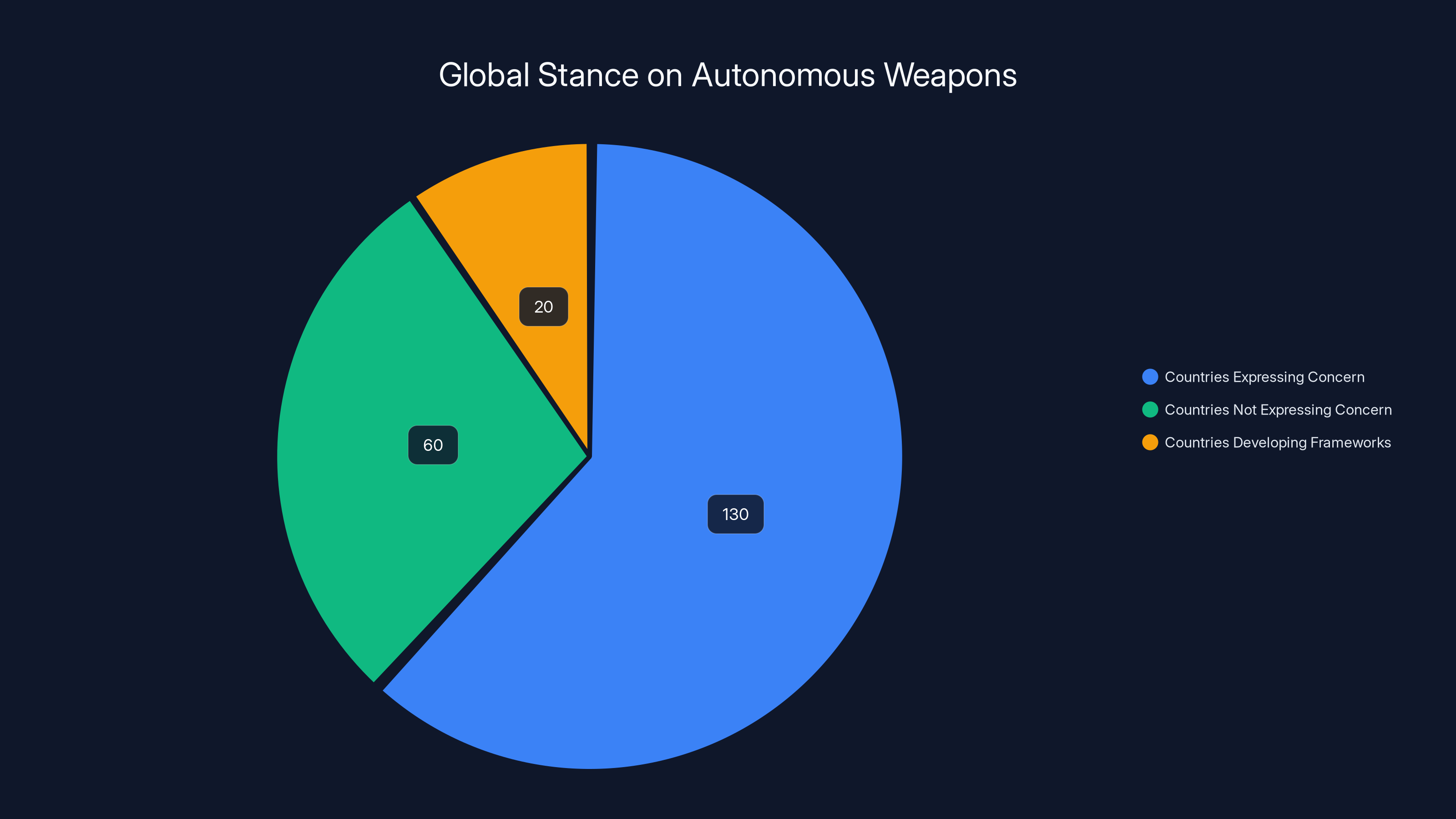

The United Nations has been discussing autonomous weapons for years. The Group of Governmental Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems has met multiple times. Various countries have proposed frameworks. Some countries want a complete ban on fully autonomous weapons. Others want regulations. Some countries haven't really taken a position.

Meanwhile, the technology keeps advancing.

One expert who's been paying attention is Michael Horowitz. He sees the parallel to cyber weapons. The U. S. and other powers developed cyber capabilities rapidly, often without international agreement about what was acceptable. By the time anyone tried to regulate, the cat was out of the bag. Everyone had cyber weapons. Everyone was vulnerable.

He worries autonomous weapons could follow the same path. Nations develop them because they fear falling behind. They don't share information about their capabilities because that would reveal strategy. Before you know it, every major military has autonomous systems, and there's no international agreement about their use.

Then what? All-out autonomous warfare between AI systems? That's not science fiction—that's a plausible scenario if we're not careful.

Over 130 countries have expressed concern about autonomous weapons, while fewer are actively developing regulatory frameworks. Estimated data based on international discussions.

The Geopolitical Stakes: AI and U. S.-China Competition

To understand why Scout AI matters, you need to understand geopolitics.

The U. S. has maintained military superiority for decades largely through technological advantage. American drones are more capable than others. American sensors are more advanced. American coordination systems are faster. American AI is better.

That last part is starting to slip.

China has been investing heavily in AI development for military applications. The Chinese government sees AI as central to its future military power. In 2017, China's State Council released a plan to become a global AI innovation leader by 2030. That includes military AI.

U. S. intelligence agencies assess that China is developing autonomous weapons systems comparable to what Scout AI is building. That assessment creates pressure on the Pentagon to accelerate AI adoption domestically.

It's a classic arms race dynamic. Each side assumes the other is building more advanced weapons, so each side accelerates its own development. Sometimes the assumptions are correct. Sometimes they're paranoid. But either way, the result is an acceleration of dangerous technology.

The U. S. government has tried to slow China's AI development by restricting chip exports. NVIDIA's advanced GPUs—the processors that power large language models—are banned from sale to China. Intel's advanced chips face restrictions. ASML's chip manufacturing equipment faces export controls. The goal is to handicap China's ability to train large AI models.

But chip restrictions only work if they're enforced consistently. The Trump administration has been loosening some controls, prioritizing economic interests over military caution. That makes it more likely that advanced chips reach China, which accelerates Chinese AI development, which creates more pressure on the Pentagon to move faster with its own AI weapons.

It's a downward spiral. And Scout AI's existence is a symptom of that spiral.

Colby Adcock told the media that Scout AI has four defense contracts already. That number will grow. The Pentagon will continue funding these projects because the alternative—falling behind China—seems worse.

Cybersecurity Concerns: How Vulnerable Are AI-Powered Weapons?

Here's a scenario that should terrify military planners: what if an adversary could hack into Scout AI's system and redirect the drones?

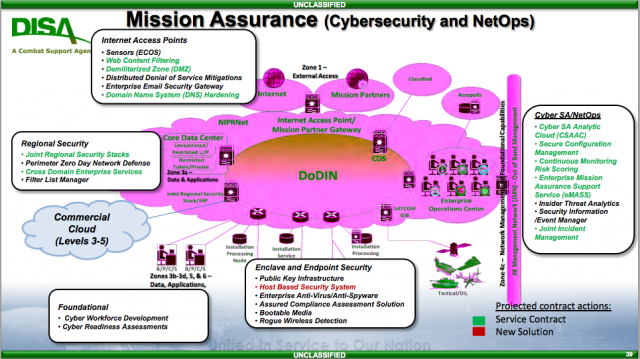

Traditional military systems are air-gapped—not connected to the internet. Scout AI's system can run that way, according to Adcock. But the advantage of cloud-connected systems is that they're easier to manage and update. There's a tradeoff between security and convenience. Most organizations choose convenience.

Once a system is connected to any network, it's vulnerable. Military contractors have been hacked before. Solar Winds compromised thousands of government and private organizations in 2020. The OPM breach exposed millions of federal employee records in 2015. These weren't AI systems—they were critical infrastructure. If critical infrastructure is vulnerable, AI-powered weapons systems would be too.

An adversary who could compromise Scout AI's system might be able to:

- Change targeting parameters so drones attack friendly forces instead of enemies

- Disable safety systems so the drones attack without human authorization

- Redirect drones to attack civilian targets instead of military ones

- Make the system believe it's operating in a different geographic location

- Cascade compromises to other military systems connected to the same network

Scout AI likely has security engineers working on these problems. But military cybersecurity is notoriously difficult. You're trying to defend against adversaries with nation-state resources. And you're defending systems that must work reliably under stress, in degraded communications environments, with incomplete information.

Michael Horowitz's skepticism makes sense here. Demonstrating that a system can autonomously destroy a target in a controlled test environment is different from proving it's secure against sophisticated adversaries in active conflict.

There's also the question of supply chain security. Scout AI uses open-source models. Those models were trained on open-source data. But they were likely trained on systems using open-source frameworks like Py Torch or Tensor Flow. Those frameworks are maintained by communities that include international contributors.

What if someone in a hostile country contributed code to one of those open-source projects? What if that code includes subtle vulnerabilities that only activate under specific conditions? That's not theoretical—researchers have published papers on exactly this type of attack.

Military systems need to be able to verify every line of code, every library, every dependency. Open-source is great for innovation. It's a nightmare for cybersecurity in military contexts.

The Fury Orchestrator is significantly larger with 100 billion parameters, compared to the 10 billion parameters of the ground vehicle and drone AI models.

The Ethical Minefield: Who Decides to Kill?

Let's step back from technical details and ask a harder question: is it ethical for an AI system to decide to kill someone?

There are different schools of thought on this. Some people argue that any decision to use lethal force must be made by a human, full stop. Others argue that if a human sets the parameters and objectives, delegating execution to an AI is acceptable. Still others believe AI systems will eventually be better at making targeting decisions than humans are.

The international humanitarian law perspective is that a human must make a "meaningful human control" decision about whether to use lethal force. But what does "meaningful" mean? Is it enough for a human to authorize a mission and let AI execute? Or does the human need to be in the decision loop for each individual target?

Scout AI's demonstration sits in a gray area. A human issued a command (destroy the truck). The AI planned the operation and executed it. Was the human's authorization meaningful, or was it just a rubber stamp on an automated process?

Ethicists worry about something called "moral disengagement." When you delegate a decision to a machine, does that reduce your sense of responsibility for the outcome? If something goes wrong, do you blame the AI instead of taking accountability?

We see this in other contexts. Autonomous vehicles kill people sometimes. When they do, the question of responsibility becomes murky. Did the programmer create a flawed system? Did the manufacturer fail to test it adequately? Did the owner misuse it? The car just executed code. Should we blame the code?

In military contexts, this matters more. If a Scout AI drone strikes a hospital because the AI misidentified it as a military target, who's responsible? Colby Adcock? Scout AI's engineers? The operator who gave the order? The military command that approved the operation? International law requires someone to be held responsible. But it's not clear who that would be.

There's also the question of escalation. If both sides are using AI to autonomously control weapons, the pace of conflict accelerates. Humans think in seconds and minutes. AI thinks in milliseconds. A conflict between two militaries using autonomous weapons could escalate to full-scale war in minutes, before any human diplomat has a chance to intervene.

Scout AI's Competition: Other Defense AI Startups

Scout AI is remarkable, but it's not alone. The defense tech space is becoming crowded with AI-focused startups.

Anduril Industries, founded by Palmer Luckey (the Oculus VR creator), is building AI-powered defense systems. They've raised over $1.2 billion in funding. Their focus is on autonomous systems for border security, perimeter defense, and eventually, tactical operations. Anduril's approach is slightly different from Scout AI's—they're building integrated platforms rather than adapting existing models. But the goal is similar: AI that can operate independently with minimal human intervention.

Latitude is developing AI-powered autonomous drones focused on surveillance and reconnaissance. They've been growing quietly, picking up contracts with various government agencies. Their drones can plan routes autonomously, identify objects in video feeds, and optimize search patterns without human direction.

Exo Interactive is focused on AI-powered command and control systems. Instead of managing one drone or vehicle, commanders can manage fleets using AI intermediaries. The AI interprets high-level commands and distributes tasks across multiple platforms.

Janus Research is building AI systems for intelligence analysis. They're using large language models to process classified information, identify patterns, and create assessments. Different application, same principle: delegating cognitive work to AI.

The funding environment is favorable. Venture capital firms are starting defense tech funds specifically focused on AI. Traditional defense contractors like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon are either acquiring AI startups or building their own AI divisions.

What's striking is the speed. Five years ago, AI in defense meant computer vision for drone feeds or recommendation algorithms for supply chain optimization. Now it means autonomous targeting, strategic planning, and fleet coordination.

The Pentagon is accelerating this. The U. S. Defense Innovation Unit, a Department of Defense office focused on bringing Silicon Valley technology into military applications, is explicitly seeking AI technologies for autonomous systems. They've held workshops on "human-machine teaming" and published guidance on how to accelerate AI adoption.

The message is clear: move faster. Deploy more. Iterate quickly. The risk of falling behind China is greater than the risk of deploying untested technology.

The Deployment Timeline: How Soon Until Autonomous Weapons in Combat?

When asked about deployment, Colby Adcock said Scout AI's technology would take a year or more to be ready for actual military use.

A year might sound like a long time. It's not. Military timelines move slower than that in peacetime. But we're not in peacetime everywhere. Ukraine is an active conflict. The Middle East is unstable. China is increasingly assertive around Taiwan.

If Scout AI gets funding and political support, a year of development could get them to initial operational capability. From there, scaling takes additional time, but not as much as you'd expect. If something works, militaries want it deployed quickly.

The trajectory looks like this:

Year 1: Scout AI completes development on autonomous drone swarms for tactical operations.

Year 2: Initial deployment to select units for testing and validation. Lessons learned, bugs fixed, improvements integrated.

Year 3-4: Broader deployment to more units. Training of personnel. Integration with existing command and control systems.

Year 5+: Wide scale deployment. By then, other nations have developed comparable systems. The arms race is on.

This timeline is speculative, but it's based on how military acquisition actually works. New fighter jets take 10-15 years to develop. New communication systems take 5-7 years. But AI development is faster because you're not constrained by physical engineering in the same way.

The other timeline that matters is how long until other nations deploy similar systems. Intelligence agencies assume China is working on this. Russia probably is too. If the U. S. deploys autonomous weapons, everyone else will accelerate their own programs.

Once one nation fields autonomous weapons in combat, the others follow within months or maybe years. That's the pattern with new military technology. Whoever moves first sets the precedent.

The Innovation Paradox: Speed vs. Safety

Here's the central tension in everything we've discussed: the faster you move with AI weapons, the less tested they are. The safer you want them, the slower development becomes. And if you move slowly while others move fast, you fall behind.

Traditional military procurement has always balanced this. You test systems extensively. You put them through evaluations. You build redundancy and safety margins. But that process takes time.

AI is different because the problem space is so large. Large language models are trained on billions of parameters. You can't test every possible input. You can't anticipate every edge case. There's inherent uncertainty that testing can't eliminate.

Scout AI's approach is to build the system, demonstrate it works in controlled conditions, then deploy it and iterate based on real-world experience. That's the Silicon Valley playbook: move fast and break things. It works for social media and cloud computing. Does it work for weapons systems?

The argument in favor: real-world conditions reveal problems that testing can't. You'll learn faster by deploying and iterating than by endless testing. The military has always relied on experience in the field to improve tactics and systems. Why should AI be different?

The argument against: breaking things in combat means killing people. There's no graceful degradation with lethal weapons. A bad decision isn't something you can patch. A security vulnerability isn't something you can fix with an update after the damage is done.

Michael Horowitz falls on the cautious side. He emphasizes that impressive demonstrations don't equal reliable systems. And he's right—military systems need to be reliable, secure, and compliant with international law. Scout AI's demo was impressive, but it's not proof that the system will work reliably under stress, against sophisticated adversaries, in real warfare.

But the Pentagon's timeline pressure is real. If China is building this, the U. S. can't wait years for perfect systems. Better to deploy something that's 80% ready than wait for 100% and find out an adversary deployed 90% already.

Societal Impact: What Happens If This Becomes Normal?

Let's zoom out and think about the broader implications.

If autonomous weapons become standard military equipment, warfare changes fundamentally. The human experience of combat—where training, judgment, and quick thinking determine outcomes—gets replaced by algorithmic competition.

Small nations become more vulnerable. If a large nation has superior AI systems, they have an insurmountable military advantage. Wars become competitions between AI systems, not between human soldiers.

Civilian casualties potentially increase. Current warfare, for all its horror, has humans making decisions about targeting. Those humans can exercise judgment, consider context, show mercy. AI systems that misidentify targets don't have those capabilities.

Alternatively, autonomous systems could reduce civilian casualties if they're more precise, more disciplined, and less prone to anger or fear than humans are. The research on this is mixed. Studies suggest AI systems are better at recognizing patterns but worse at understanding context.

There's also the question of consent. People living in areas where autonomous weapons operate have no say in that decision. They're living in a war zone controlled by machines. There's something deeply unsettling about that.

On the other hand, autonomous weapons might deter war. If the human cost of conflict drops significantly, nations might be more willing to go to war. Or they might be less willing, since the advantage goes to whoever has the best AI, not whoever is willing to sacrifice the most soldiers.

We're in unprecedented territory. We have theories about what will happen, but no historical precedent. Previous military revolutions—tanks, aircraft, nuclear weapons—were preceded by decades of debate and development. AI weapons are moving faster than society can really process.

The Path Forward: Regulation, Vigilance, and Unknown Unknowns

What should happen next?

On the regulation front, there needs to be binding international agreement on autonomous weapons. Some baseline agreements: nations shouldn't deploy fully autonomous weapons in civilian areas. Nations should maintain human control over critical targeting decisions. Nations should agree to limit weapons sales to countries that don't follow these norms.

But regulation only works if it's enforced. And enforcement requires transparency. Nations won't voluntarily disclose their autonomous weapons programs if they think it gives away strategic advantage.

On the domestic front, the U. S. needs clear policy on how autonomous weapons should be used. Should they only be deployed in defined military conflicts, or can they be used in counter-terrorism operations? Should they be restricted to defensive roles, or can they conduct offensive operations? Should there be escalation restrictions—i.e., no autonomous system can initiate conflict?

On the technical front, AI safety research needs massive investment. We need better ways to verify that AI systems behave as intended. We need to understand emergence in multi-agent systems. We need cybersecurity frameworks specifically designed for AI systems. We need testing protocols that actually work for large language models.

All of this is expensive. All of it is urgent. And all of it is being underfunded compared to the AI weapons development itself.

There's also the question of transparency. Scout AI's demonstration was public, at least in the sense that WIRED was allowed to report on it. That's good. More transparency helps build public understanding of what's actually happening. But nations also guard military capabilities closely for strategic reasons. The balance between transparency and operational security is difficult.

Ultimately, the challenge is that we don't know what we don't know. Autonomous weapons systems will behave in ways we didn't anticipate. They'll fail in ways we didn't predict. They'll create scenarios we didn't consider.

The best we can do is move carefully. Deploy cautiously. Keep humans in decision-making loops. Build in safeguards and redundancy. And constantly reassess as we learn more.

Scout AI's demonstration is impressive. It shows that the technology works. But it also shows that we're not ready for widespread deployment. And the pressure to deploy anyway is enormous.

FAQ

What is Scout AI?

Scout AI is a defense technology startup founded by Colby Adcock that develops AI agents for autonomous military operations. The company uses large language models and smaller AI models to control unmanned vehicles and drones, enabling autonomous targeting and execution of military missions with minimal human intervention. Scout AI has demonstrated its technology conducting autonomous strikes on targets and currently holds four Department of Defense contracts.

How do AI agents control weapons?

AI agents use a hierarchical system where a large strategic AI model interprets high-level commands from human operators, then delegates tactical decisions to smaller AI models running on individual platforms like drones or ground vehicles. These smaller models make independent decisions about route planning, target identification, and timing, while pre-programmed rules and safety systems constrain their actions. The system allows machines to interpret commander intent and adapt to changing circumstances without step-by-step human control.

What are the main concerns about autonomous weapons?

Key concerns include unpredictability of AI systems in novel situations, vulnerability to cyberattacks, difficulty ensuring compliance with international humanitarian law, questions about human accountability when autonomous systems make targeting decisions, and the risk of rapid escalation in conflicts between AI-controlled systems. Additionally, AI systems struggle with distinguishing combatants from civilians in complex real-world environments where traditional rules of engagement are ambiguous.

Is autonomous weapons development regulated internationally?

There is no binding global treaty restricting autonomous weapons development, though over 130 countries have signed agreements expressing concern about them. The United Nations has convened expert groups to discuss international norms, and various countries have proposed frameworks, but enforcement mechanisms don't exist and major military powers continue developing these systems. International humanitarian law requires "meaningful human control" over lethal force decisions, but the definition of "meaningful" remains contested.

How soon will autonomous weapons be deployed?

Scout AI estimates their technology could be ready for military deployment within a year, though wider integration into military operations would take several additional years. However, some autonomous weapons features are already used in active conflicts like Ukraine, where consumer drones and commercial systems operate with various levels of autonomy. Full-scale deployment of AI-agent-controlled weapons could occur within 3-5 years as multiple nations develop similar capabilities.

Can AI systems reliably follow international law?

Currently, AI systems cannot reliably make the complex contextual judgments required by international humanitarian law. Large language models and computer vision systems struggle with identifying legitimate military targets versus civilians, assessing military necessity, and understanding surrender or incapacitation. While Scout AI claims its systems are designed to follow rules of engagement and the Geneva Convention, the technical mechanisms for ensuring this compliance remain unclear and unproven in real combat conditions.

What is the arms race concern?

Military strategists fear that if one nation deploys advanced autonomous weapons, others will accelerate their own development to avoid falling behind, creating a destabilizing arms race. This dynamic is particularly acute in U. S.-China competition, where American officials believe China is developing comparable systems. The pressure to move quickly conflicts with the need for careful testing and safety validation, potentially resulting in deployment of inadequately tested systems.

How does this affect international stability?

Autonomous weapons could fundamentally alter military balance of power, potentially advantage technologically advanced nations with superior AI systems. The speed at which autonomous systems can escalate conflicts—operating at machine speed rather than human decision-making speed—creates risk of rapid uncontrolled escalation. Additionally, the difficulty of verification and enforcement of international norms could lead to an unregulated arms race similar to what occurred with cyber weapons.

Conclusion: The Inevitable Tension Between Innovation and Safety

Scout AI's demonstration of autonomous drones destroying a target represents a watershed moment. It's not the first time machines have killed—that's been happening for over a century. But it's the first time AI agents have planned and executed that killing with minimal human direction based on a high-level strategic objective.

The implications are staggering. And they're happening faster than institutions can responsibly govern them.

We're caught between two inarguable truths. First, autonomous AI systems will become more capable. This isn't a question of whether, but when. Second, deploying these systems before we fully understand their limitations is dangerous. Probably inevitable, but dangerous.

The Pentagon sees AI dominance as crucial to American military superiority. That's probably not wrong. But moving at military development speed while respecting safety, legal, and ethical constraints requires something most organizations aren't good at: slowing down even when you feel pressure to speed up.

Colby Adcock is building what might be the future of warfare. His engineers are solving real technical problems. His company is answering the Pentagon's call for speed. But Michael Horowitz's skepticism is warranted. Impressive demonstrations don't equal reliable systems. And reliability is everything when the stakes are measured in lives.

The next few years will determine whether autonomous weapons are governed by binding international agreements or whether we follow the path of cyber weapons—rapid proliferation, no global rules, and everyone vulnerable to everyone else.

Scout AI probably can't control that outcome. But the choices made by policymakers, military leaders, and other defense tech startups absolutely can. The window for creating international norms is narrow. Once autonomous weapons are widely deployed, it closes.

What happens next depends on whether institutions move as fast on safety and governance as they're moving on the technology itself. So far, the technology is winning the race.

Key Takeaways

- Scout AI demonstrated AI agents that can autonomously plan and execute military strikes with natural language strategic commands, using hierarchical AI models to coordinate ground vehicles and lethal drones

- The Pentagon is accelerating autonomous weapons development due to concerns about falling behind China, creating pressure to deploy systems before comprehensive safety validation is complete

- Large language models are inherently unpredictable and vulnerable to adversarial attacks, raising serious questions about reliability and cybersecurity for autonomous weapons systems

- International humanitarian law and arms control frameworks lag far behind the pace of autonomous weapons development, with no binding global treaty restricting deployment

- Multiple defense startups including Anduril, Latitude, and others are racing to develop similar autonomous weapons systems, indicating this is not an isolated development but part of a broader industry shift

Related Articles

- Kana AI Agents for Marketing: The $15M Startup Reshaping Campaign Automation [2025]

- The AI Agent 90/10 Rule: When to Build vs Buy SaaS [2025]

- RentAHuman: How AI Agents Are Hiring Humans [2025]

- The Great AI Ad Divide: Why Perplexity, Anthropic Reject Ads While OpenAI Embraces Them [2025]

- SurrealDB 3.0: One Database to Replace Your Entire RAG Stack [2025]

- Infosys and Anthropic Partner to Build Enterprise AI Agents [2025]

![AI Defense Weapons: How Autonomous Drones Are Reshaping Military Tech [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-defense-weapons-how-autonomous-drones-are-reshaping-milit/image-1-1771445375162.jpg)