Photonic AI Chips: How Optical Computing Could Transform AI [2025]

Light travels at 299,792 kilometers per second. Electrons? They move through silicon at maybe a fraction of that speed, constrained by resistance, heat, and the physical limits of transistors.

What if we stopped using electrons altogether?

That's the premise behind a breakthrough that's quietly reshaping how the tech world thinks about AI acceleration. Chinese researchers at institutions like Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University have unveiled photonic AI chips that swap electrons for photons—light particles—to perform computation. The results sound almost absurd: performance gains of 100x or more on certain generative AI tasks compared to Nvidia's industry-standard A100 GPUs.

Before you dismiss this as another overhyped laboratory novelty, understand this: the speed gains are real, the underlying physics is sound, and the architectural trade-offs are worth understanding. But here's the catch—and it's a big one—these chips don't replace GPUs. They're specialized machines designed for very specific workloads.

I've spent the last month digging into the research papers, talking to hardware engineers, and understanding what photonic computing actually means in practice. The gap between "100x faster in the lab" and "100x faster in your data center" is enormous. But the fundamental shift this represents for AI infrastructure is worth your attention.

TL; DR

- Photonic chips use light instead of electricity: Photons replace electrons, enabling massive parallelism through optical interference rather than sequential digital execution

- Speed gains are real but narrowly scoped: Researchers claim 100x+ improvements, but only on specific generative tasks like image synthesis and vision processing, not general-purpose computing

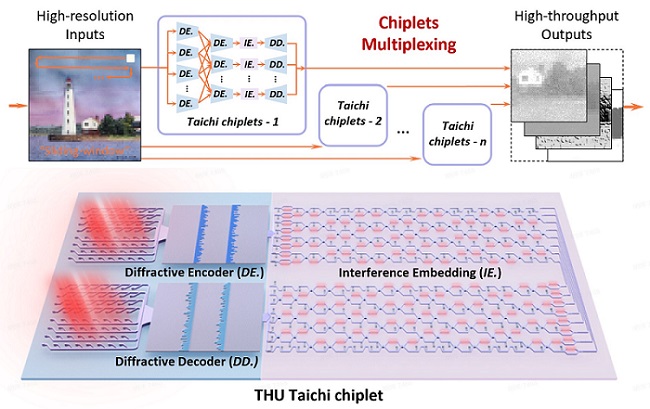

- Two major prototypes exist: ACCEL from Tsinghua University combines photonic and analog electronic components; Light Gen contains over 2 million photonic neurons for all-optical processing

- Energy efficiency is dramatic: Optical computing generates far less heat and consumes significantly less power than traditional electronic GPUs for targeted workloads

- Adoption timeline is uncertain: These are laboratory demonstrations, not commercial products—widespread deployment likely still 5-10 years away

- The real opportunity: Photonic chips could handle specialized AI inference tasks, freeing up expensive GPU clusters for training and general-purpose computing

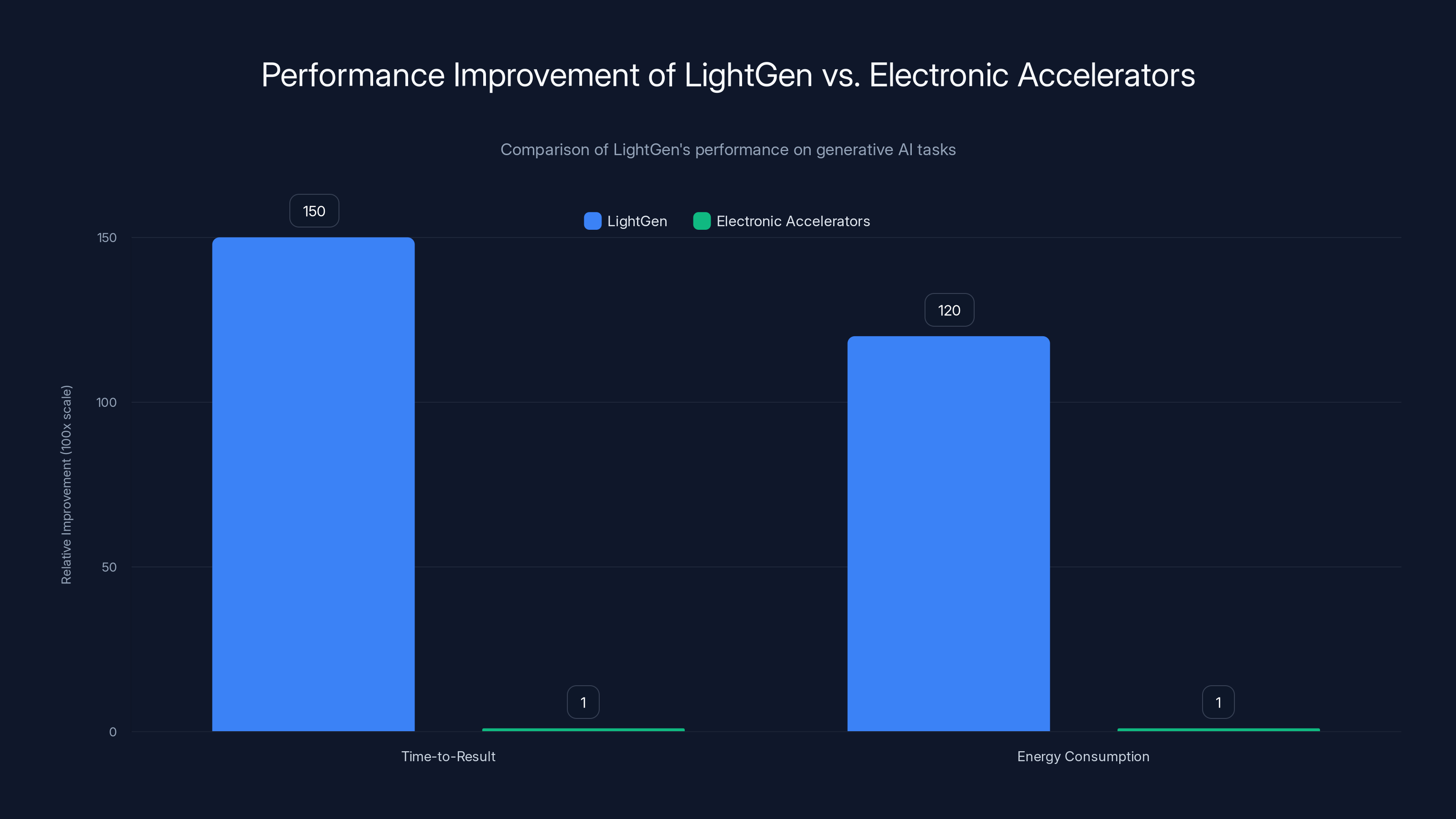

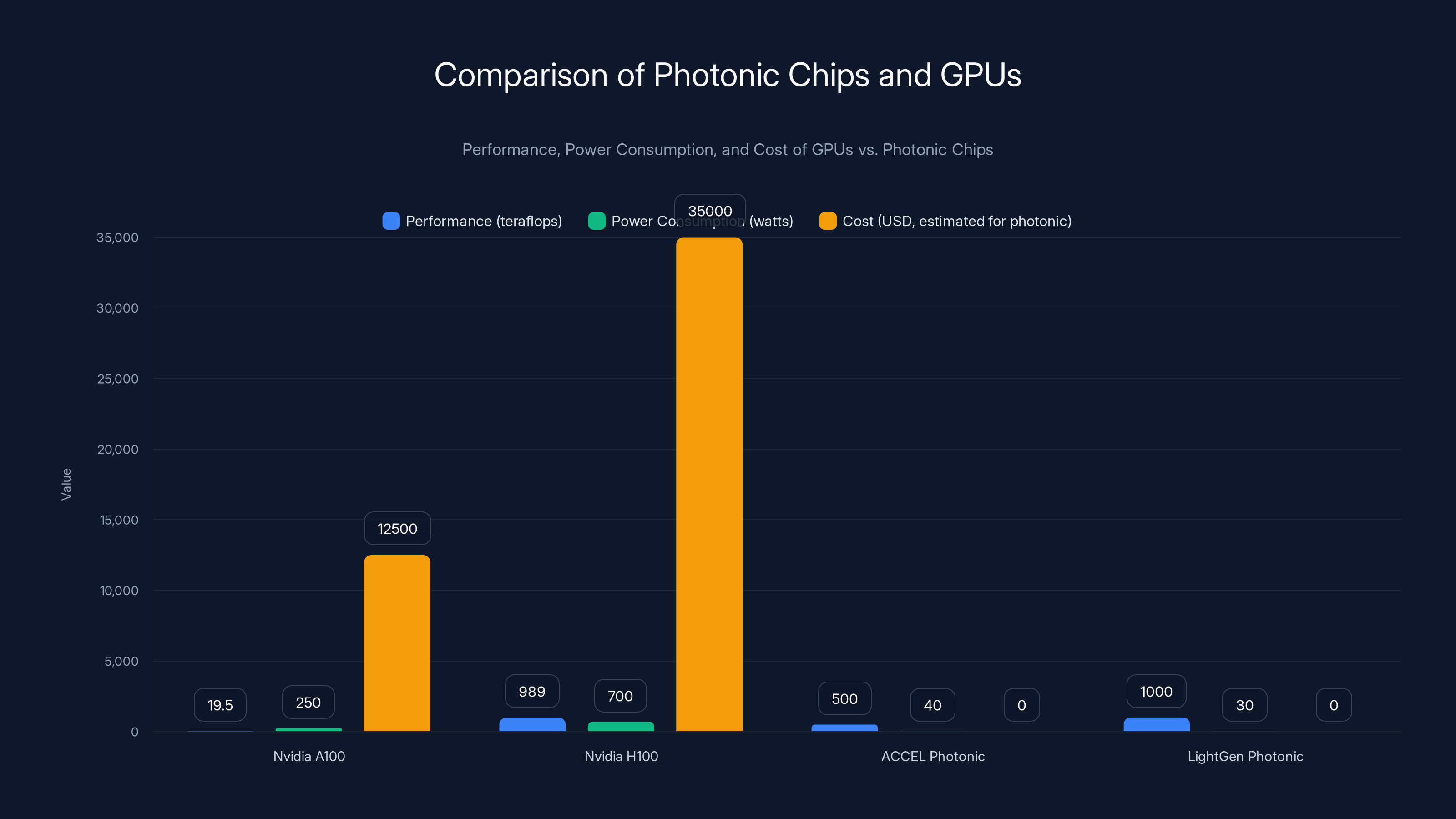

LightGen shows over 100x improvement in both time-to-result and energy consumption for generative AI tasks compared to traditional electronic accelerators. Estimated data based on reported performance improvements.

The Fundamental Problem With Traditional GPU Computing

Nvidia's A100 and H100 GPUs are engineering marvels. They contain billions of transistors, operate at clock speeds measured in gigahertz, and can execute trillions of floating-point operations per second. By any reasonable standard, they're impressively fast.

But they're also running into hard physical limits. When you cram 80 billion transistors onto a single chip, heat becomes a serious problem. Current flows through silicon, generating thermal energy. The hotter the chip, the slower the electrons move, and the more power you need to pump in just to maintain performance.

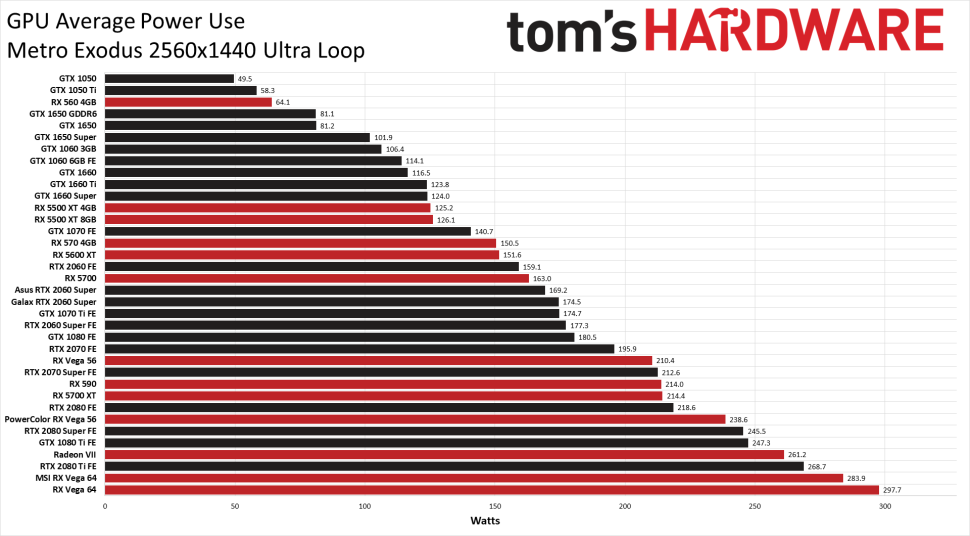

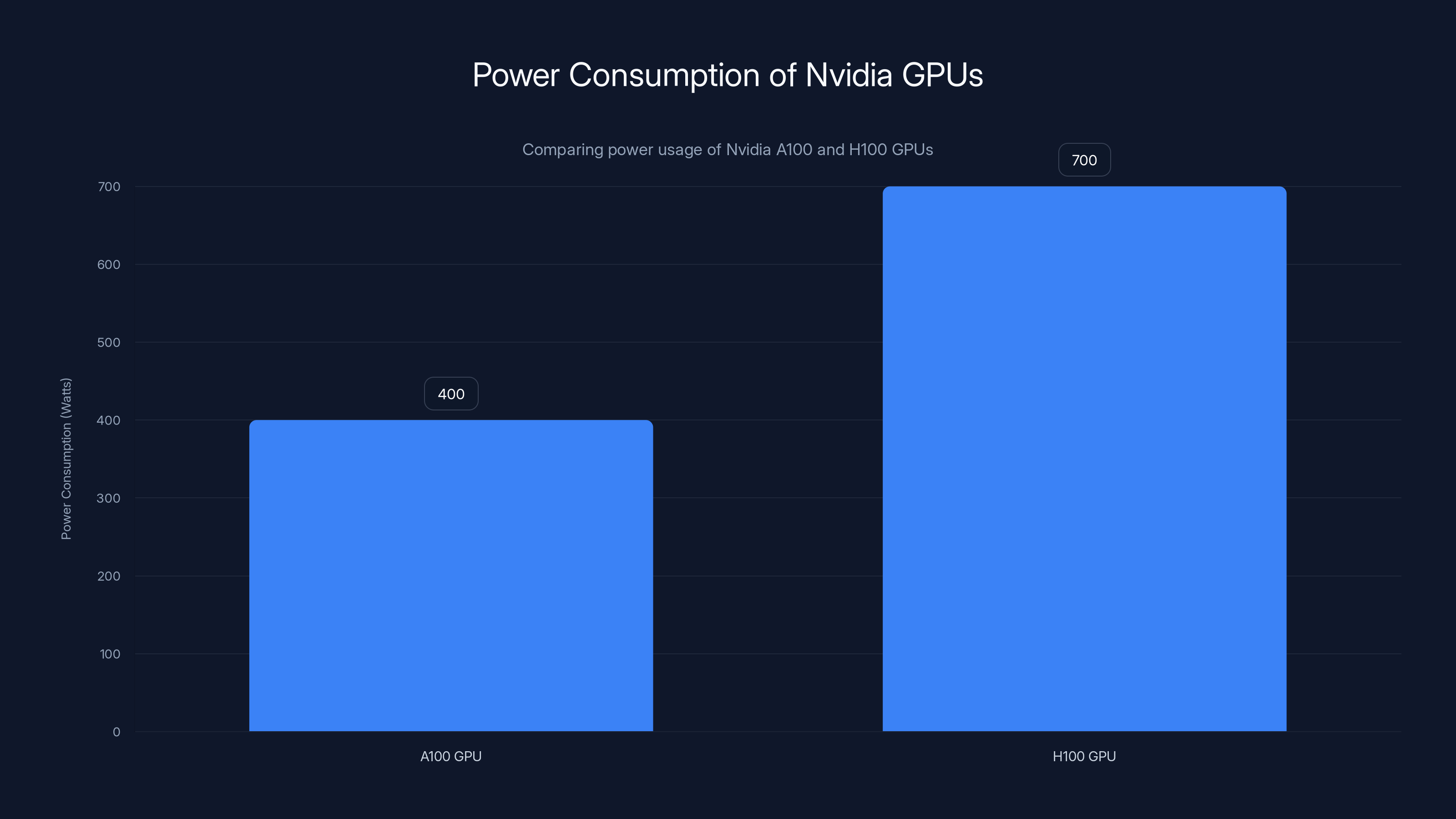

Consider the numbers. A single Nvidia H100 GPU consumes up to 700 watts of power under load. A data center with 1,000 H100s pulls 700 kilowatts—roughly the power consumption of a small town. That power doesn't just cost money; it generates heat that requires equally expensive cooling infrastructure.

There's also a conceptual issue. GPUs perform computation by moving electrons through transistors in predictable sequences. This approach is incredibly flexible—you can run any software, train any model, execute arbitrary algorithms. But that flexibility comes with overhead. Every instruction, every memory access, every calculation requires electron movement through circuits.

What if you could sacrifice flexibility for raw speed? What if instead of moving electrons sequentially through transistors, you used light to perform multiple calculations in parallel?

That's the photonic computing pitch.

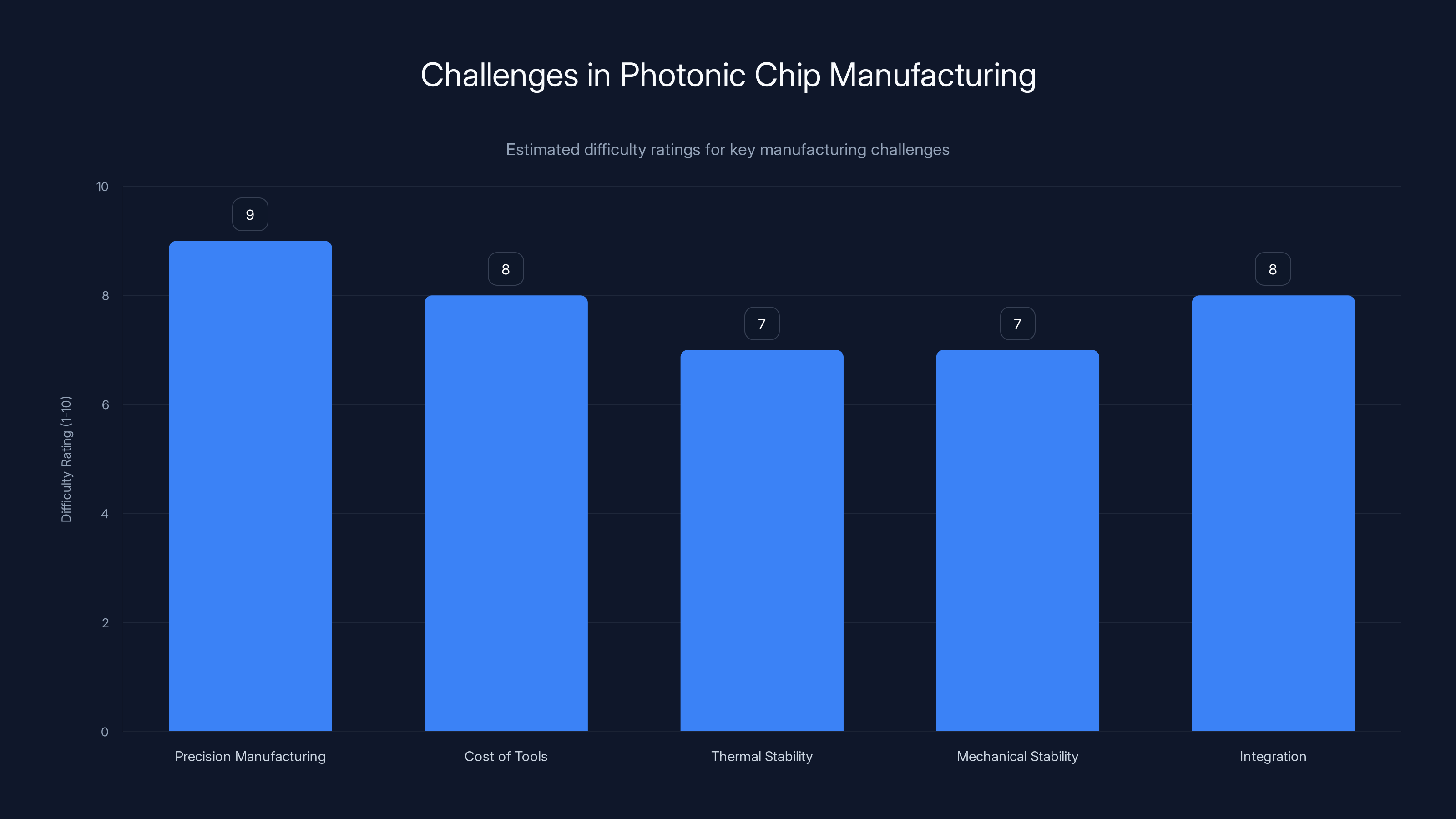

Precision manufacturing and integration are the most challenging aspects of photonic chip production, with high difficulty ratings. Estimated data.

How Photonic Computing Works: Photons Instead of Electrons

Here's where we need to get into physics briefly. Don't worry—it's not as complicated as it sounds.

Electrons are charged particles. When you apply voltage to a semiconductor, electrons move through it, and that movement carries information. The speed of electron movement is limited by several factors: the resistance of the material, the density of the semiconductor, and the distance electrons have to travel.

Photons are light particles. They move at the speed of light (obviously), and they don't carry electrical charge. Instead, they carry information through their properties: wavelength, polarization, phase, and intensity.

In a photonic computing system, instead of storing and manipulating data as electrical charges, you store and manipulate it as light. This creates several immediate advantages:

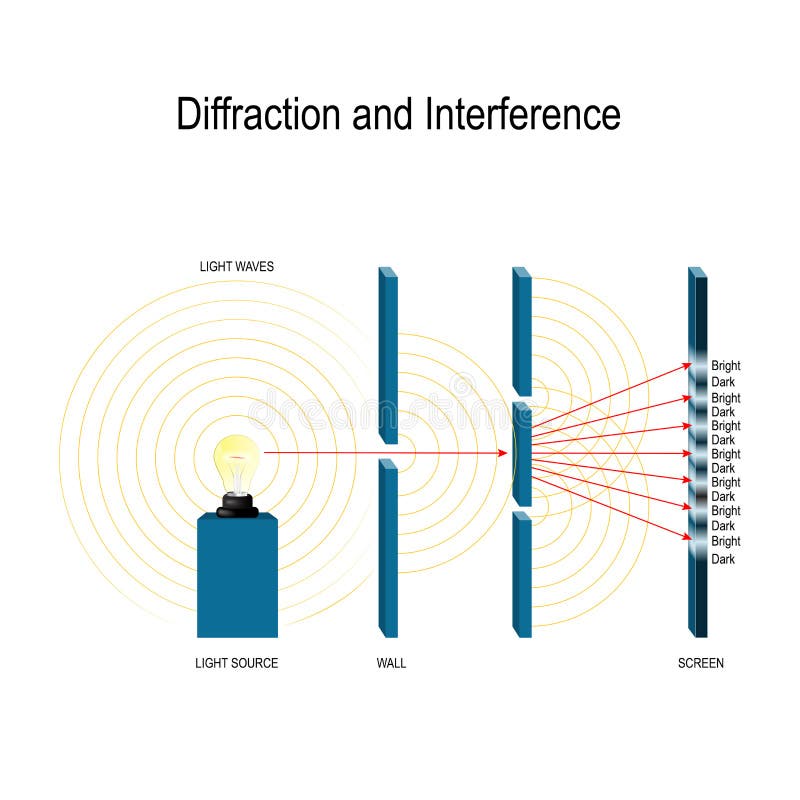

Massive parallelism through interference: Light waves can overlap and interfere with each other. When two light waves meet, they combine in predictable ways—constructive interference creates reinforcement, destructive interference creates cancellation. You can use this interference to perform computations in parallel. A photonic chip could potentially perform millions of operations simultaneously through optical interference patterns.

Minimal power consumption: Photons carry information without generating significant heat (except in the light sources themselves). Once photons are created, they traverse optical circuits with virtually no resistance. The energy loss is dramatically lower than electron-based computation.

Speed of light operations: Photons travel at 299,792 km/s. While this doesn't directly translate to faster computation (the actual speed depends on circuit design), it eliminates the electron-transport bottleneck.

Wavelength division multiplexing: Different wavelengths of light can carry independent information streams in the same physical space. This enables remarkable density—you can pack vastly more simultaneous computations into the same footprint.

The catch: photonic systems excel at problems that map well to optical operations. Matrix multiplication (core to neural networks) works great. But general-purpose programming? Running arbitrary software? That's much harder with photons.

ACCEL: Tsinghua's Hybrid Photonic Breakthrough

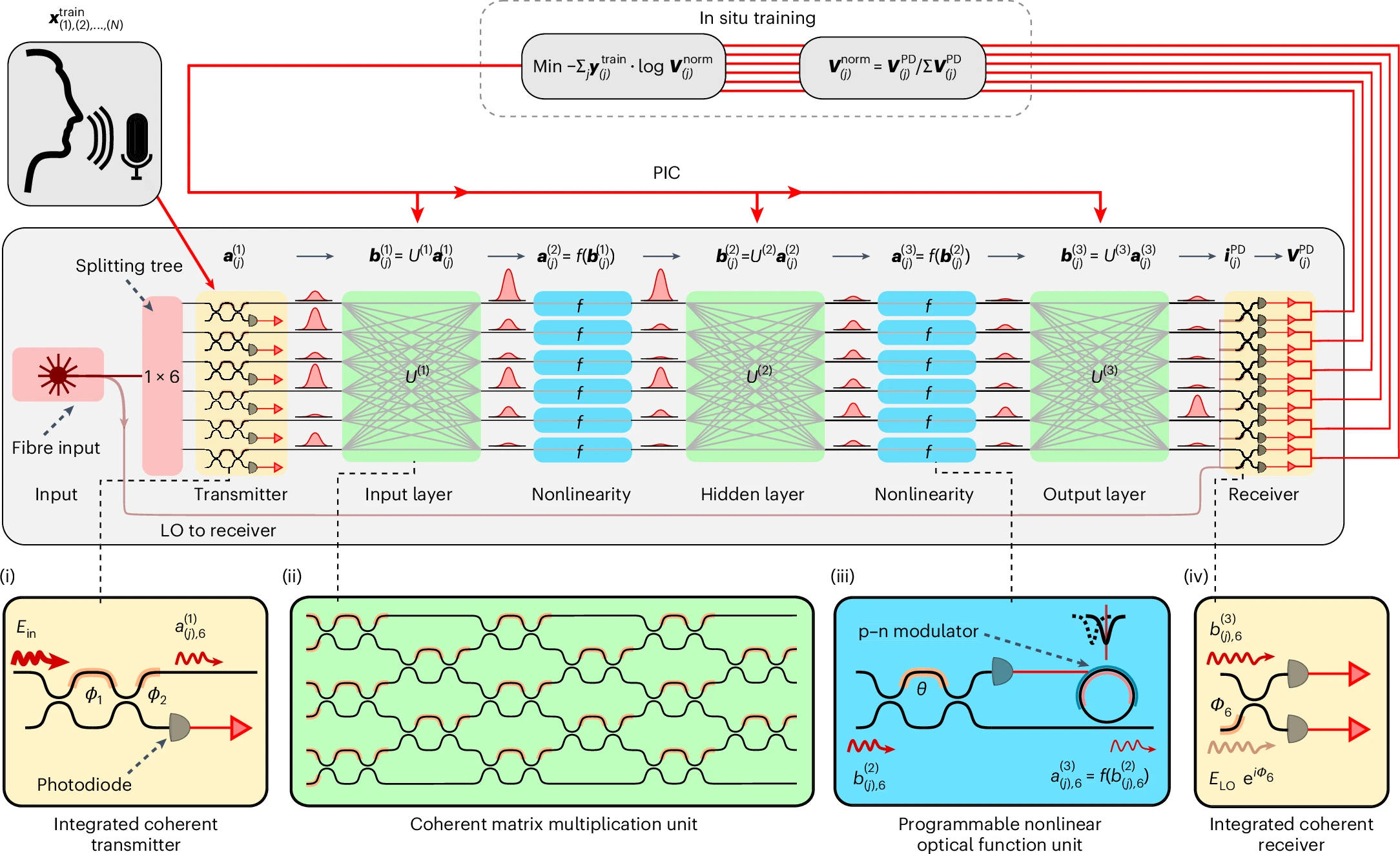

ACCEL isn't pure photonic computing. Instead, it's a hybrid architecture combining photonic and analog electronic components, developed at Tsinghua University by researchers working on specialized AI acceleration.

Here's the system design: ACCEL uses analog circuits for input processing and photonic components for the core computational layers. The photonic portions handle the heavy lifting—matrix operations that would be expensive on a traditional GPU.

The performance claims are extraordinary. Researchers reported that ACCEL achieves theoretical throughput measured in petaflops (quadrillions of floating-point operations per second) while running on older semiconductor manufacturing processes—technology nodes that Nvidia abandoned years ago. This shouldn't be possible. Yet it is, because photonic computation doesn't scale with transistor density the same way electronic computation does.

But—and this is critical—ACCEL's petaflop numbers come with major caveats. These measurements apply only to predefined analog operations, not general-purpose computation. You can't install Python on ACCEL. You can't run arbitrary TensorFlow code. The chip is hardwired for specific mathematical operations.

ACCEL's sweet spot is image recognition and vision processing. These workloads involve fixed mathematical transformations applied to high-dimensional data (pixels, feature maps). The chip's photonic core excels at these operations because they map naturally to optical interference patterns and matrix multiplications.

Researchers demonstrated ACCEL on tasks like image classification and visual feature extraction. Performance gains compared to A100 GPUs exceeded 50x to 100x on these specific workloads, according to published results. But trying to run natural language processing on ACCEL? Language models need flexibility and sequential decision-making that photonic circuits struggle with.

The hybrid approach reflects a pragmatic engineering choice. Pure photonic computers are incredibly hard to build. Adding analog electronics as an interface layer makes ACCEL easier to manufacture and control while preserving the photonic speedup where it matters most.

Nvidia's H100 GPU consumes significantly more power than the A100, highlighting the increasing energy demands of modern GPUs. Estimated data based on typical usage.

Light Gen: The All-Optical Generative AI Machine

While ACCEL is a hybrid system, Light Gen aims to be fully photonic. Developed through collaboration between Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Tsinghua University, Light Gen represents a more ambitious attempt to build an all-optical AI processor.

The architecture contains over 2 million photonic neurons. Yes, that's photonic neurons—optical components that perform neuron-like calculations using photons instead of electrons.

Light Gen's design is particularly interesting because it targets generative AI tasks specifically: image generation, denoising, three-dimensional reconstruction, and style transfer. These tasks require processing high-dimensional data in parallel, then applying learned transformations to generate new outputs.

For generative tasks, the photonic advantage is substantial. Creating a new image requires processing thousands or millions of values in parallel—exactly what optical interference patterns are good at. When you're generating a 1024x 1024 pixel image from random noise, you're performing massively parallel floating-point operations. Photonic systems handle this with exceptional speed.

Published experimental results claim performance improvements exceeding two orders of magnitude (that's 100x+) compared to leading electronic accelerators on these specific tasks. The measurements focus on time-to-result and energy consumption under controlled conditions.

But here's where skepticism is warranted. "Controlled conditions" means:

- Carefully shaped workloads optimized for the photonic architecture

- Benchmark tasks chosen to highlight photonic strengths

- Measurements in laboratory settings without real-world system integration overhead

- Comparisons that might use older GPU baselines rather than the latest Nvidia offerings

That doesn't mean the results are wrong. It means they're not directly comparable to a Nvidia H100 running production inference workloads in a real data center. The photonic system might be 50x faster on image generation in isolation, but once you factor in data movement, I/O, and system integration, the real-world advantage shrinks significantly.

Light Gen's all-optical approach is ambitious, but it also creates design challenges. Photonic circuits need careful calibration. Light sources must maintain consistent wavelengths and intensities. Optical pathways must be precisely aligned. Any deviation causes signal degradation.

Manufacturing at scale introduces additional complications. Photonic components require extreme precision—wavelength deviations of nanometers cause performance losses. Tsinghua and Shanghai Jiao Tong have demonstrated laboratory prototypes. Moving to production would require solving manufacturing challenges that Samsung, Intel, and other chip makers have been wrestling with for years.

Why These Performance Gains Only Work on Narrow Tasks

This is the question everyone should ask: If photonic chips are 100x faster, why isn't every tech company manufacturing them?

The answer cuts to the heart of computer architecture philosophy.

Traditional GPUs are general-purpose accelerators. You can train large language models on them. You can run image classification. You can perform physics simulations. You can execute arbitrary code, so long as it's parallelizable. This flexibility is what makes GPUs so dominant—they're good enough at everything.

Photonic chips are specialized accelerators. They're exceptional at specific mathematical operations—particularly matrix multiplication and convolution operations that map naturally to optical interference patterns. But they're terrible at other tasks.

Consider the performance gap on different workloads:

Image generation (Photonic advantage: 50-100x): Generating images pixel-by-pixel is massive matrix multiplication. Photonic systems shine here because optical interference performs parallel multiplications efficiently. The workload maps perfectly to the hardware.

Language model inference (Photonic advantage: 2-5x): Language models involve sequential token generation. You can't parallelize across tokens the same way you parallelize across pixels. The photonic system's advantages diminish because the workload doesn't naturally map to optical parallelism.

General-purpose software (Photonic advantage: near zero): Try running Linux on a photonic chip. You'll immediately realize why traditional computers use sequential digital logic. Photonic systems have no concept of branching instructions, conditional execution, or program counter.

This is why researchers describe photonic chips as specialist machines for "narrowly defined generative tasks." The narrow definition isn't a limitation of current prototypes—it's fundamental to how photonic computation works.

There's an economics question here too. Manufacturing a specialized chip costs billions. You only justify that investment if the market is large enough. General-purpose GPUs have a market that spans entire industries—everyone from AI researchers to game developers buys them. Photonic chips targeting only image generation might support a market of maybe 50-100 companies globally.

That's not enough to justify massive manufacturing investment—yet.

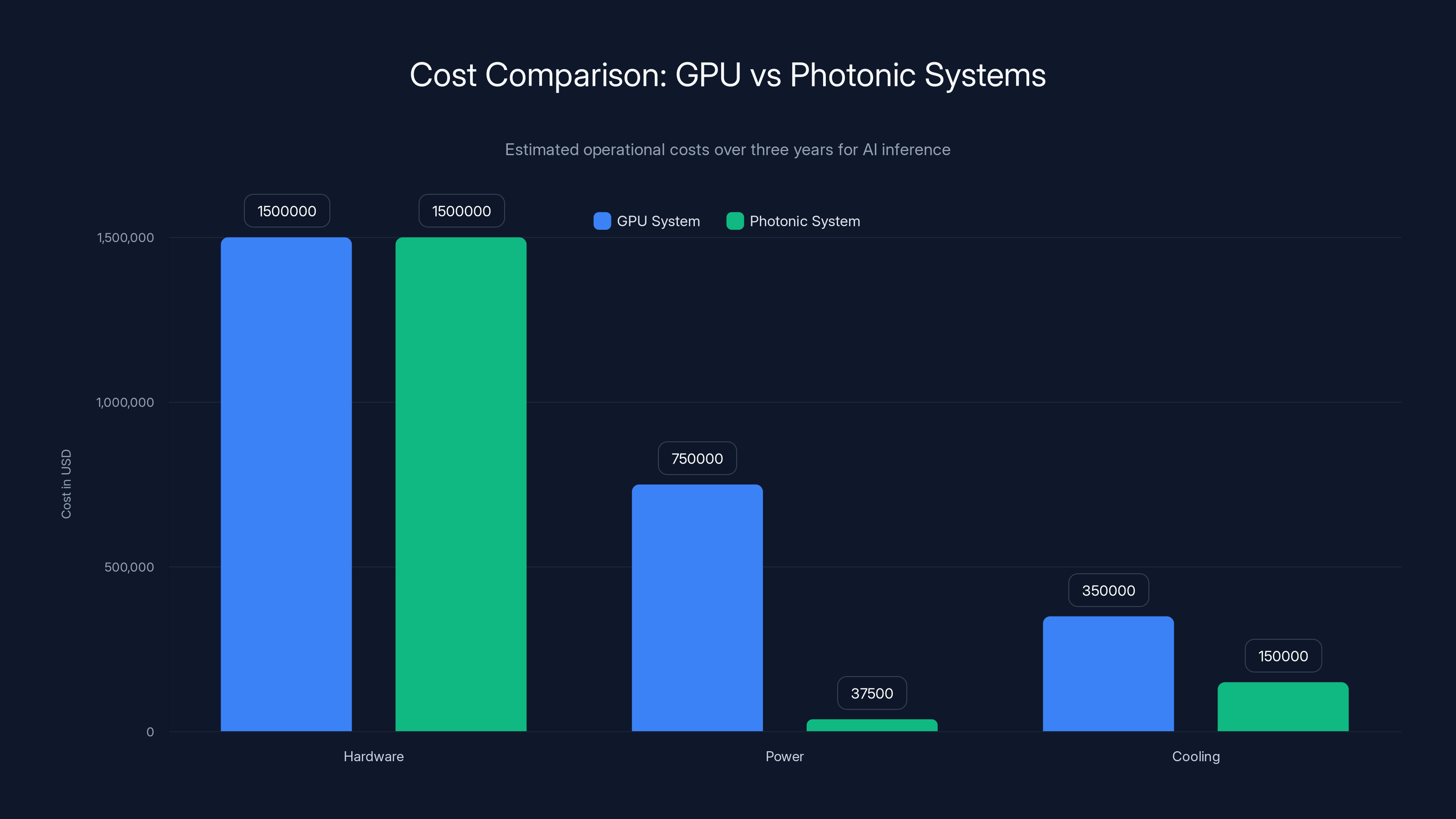

Photonic systems offer significant savings in power and cooling costs, reducing operational expenses by

The Energy Efficiency Story: Where Photonic Computing Really Wins

While speed is impressive, energy efficiency might be the more important advantage.

Here's the current reality: Running a large language model on Nvidia GPUs is expensive in two ways. First, the hardware cost—$15,000 per H100 GPU. Second, the operational cost—700 watts per GPU, multiplied by thousands of GPUs in a data center, summed across hours and days of inference.

A typical large language model inference on a cluster of 100 H100 GPUs costs approximately:

- Hardware: $1.5 million

- Power for 3 years of operation: 1,000,000 (depending on electricity costs)

- Cooling infrastructure: 500,000

Total: roughly

Photonic systems, by contrast, consume a fraction of that power. Estimates from research papers suggest 10-50x lower power consumption than GPU-based systems on comparable workloads.

Let's be conservative and assume 20x power reduction. Your electricity bill drops from

You've just saved

For a data center running 24/7:

- GPU system: 70 k W × 8,760 hours × 61,320 annually**

- Photonic system (20x reduction): 3.5 k W × 8,760 hours × 3,066 annually**

- Annual savings: $58,254 per cluster

Over 5 years, that's

For large tech companies operating thousands of GPUs, this advantage is transformative. Even if photonic chips cost twice as much per unit, the operational savings justify the investment within 18-24 months.

This is why photonic computing isn't hype. It's a fundamental architectural improvement for a specific class of problems. The speed gains get headlines. The energy efficiency gets adopted.

Comparing Photonic Chips to Current GPU Solutions

Let me break down how photonic chips stack up against today's dominant hardware.

Nvidia A100 GPU:

- Power consumption: 250 watts (40-watt idle)

- Performance on matrix multiply: 19.5 teraflops (FP32)

- Cost: 15,000

- Flexibility: General-purpose, runs any software

- Maturity: Production-ready, deployed at massive scale

Nvidia H100 GPU:

- Power consumption: 700 watts maximum

- Performance on matrix multiply: 989 teraflops (FP8)

- Cost: 40,000

- Flexibility: General-purpose, optimized for LLM inference

- Maturity: Production-ready, limited availability due to demand

ACCEL Photonic Chip (estimated specs):

- Power consumption: 30-50 watts

- Performance on image recognition: 500+ teraflops (analog operations)

- Cost: Unknown (pre-commercial)

- Flexibility: Specialized for vision tasks

- Maturity: Laboratory prototype, not commercially available

Light Gen Photonic Chip (estimated specs):

- Power consumption: 20-40 watts

- Performance on generative tasks: 1+ petaflops (theoretical)

- Cost: Unknown (pre-commercial)

- Flexibility: Specialized for generative AI

- Maturity: Laboratory prototype, not commercially available

The comparison reveals critical trade-offs:

If you need to run any AI workload, any model, any framework—GPUs remain the only choice. Flexibility is worth paying for when you have diverse needs.

If you're building a system for specific, well-defined tasks—image generation, video synthesis, specific vision pipelines—photonic chips could offer dramatic advantages once they're commercial.

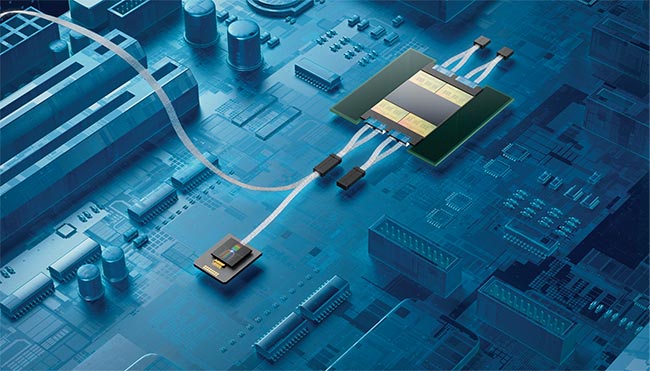

The real story isn't either/or. It's both/and. Future data centers will likely use GPUs for training and complex inference tasks, while offloading specialized generative workloads to photonic accelerators. This heterogeneous architecture would let companies optimize for both flexibility and efficiency.

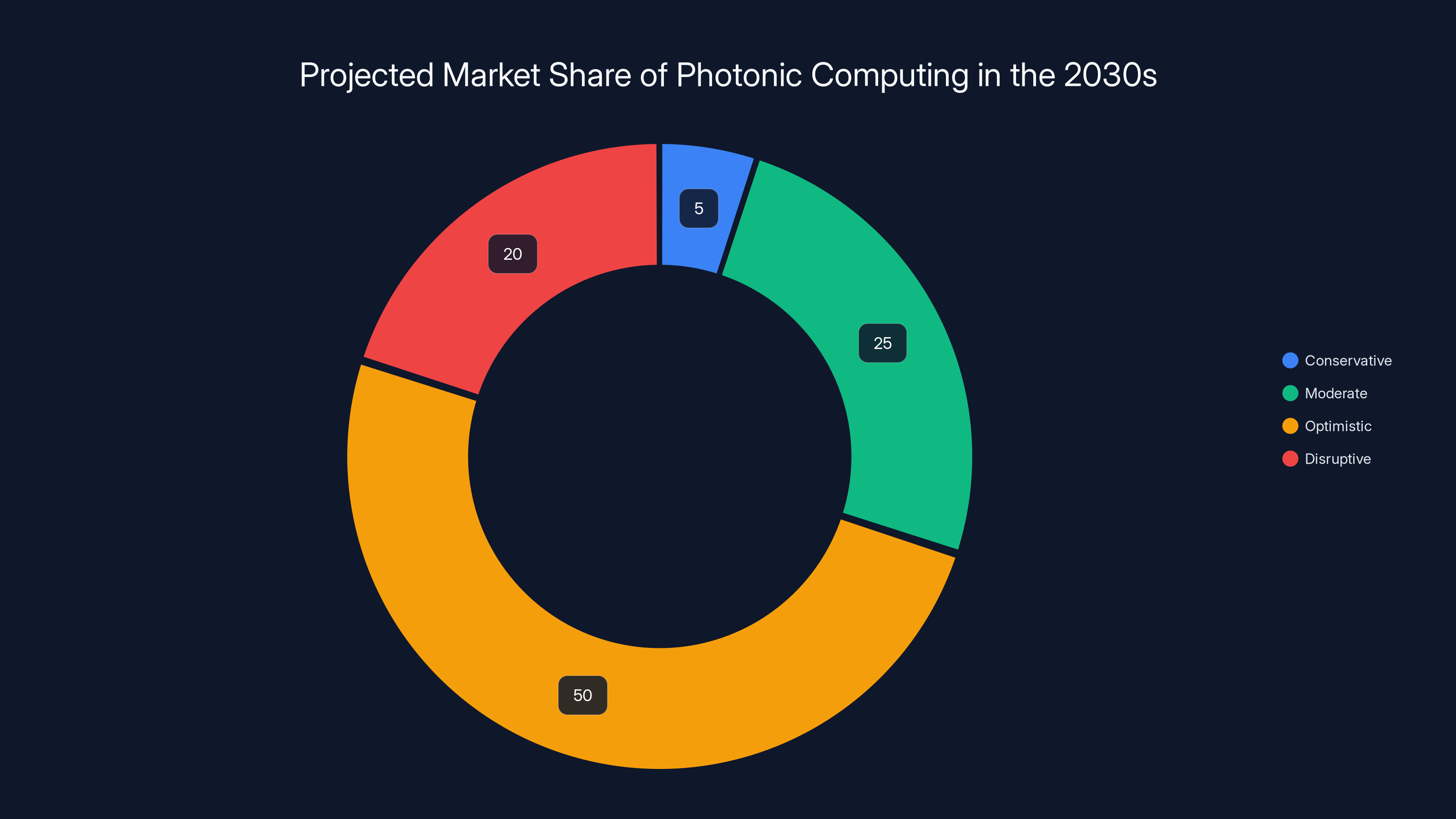

Estimated data shows the moderate scenario as most likely, with photonic chips capturing a significant niche market share by the 2030s.

Manufacturing Challenges: Why Photonic Chips Aren't in Production Yet

Let's talk about why photonic computing, despite exciting research, remains in the laboratory.

First, consider the manufacturing precision required. A photonic chip relies on optical wavelengths of light. The visible spectrum ranges from roughly 400 nanometers (violet) to 700 nanometers (red). But photonic processors often use infrared wavelengths around 1,550 nanometers, where silicon is transparent.

Now here's the problem: creating photonic circuits with precision better than 10 nanometers across an entire chip is genuinely difficult. Semiconductor manufacturing at such scales involves tools costing $100+ million per tool, with yields often below 50%. A single error—a misaligned waveguide, a wavelength deviation, a stray reflection—and the entire chip performs poorly.

Nvidia solved this problem for electronic circuits through decades of incremental improvement and massive scale. They've optimized manufacturing processes, error detection, quality assurance, and yield improvement for electronic transistors.

Photonic manufacturing is still in the early stages. Most photonic chips today are manufactured on research-grade equipment. Going from 100 prototypes per year (in the lab) to 100,000 production units per year (in a fab) requires solving manufacturing problems that don't have established solutions yet.

Second, consider thermal and mechanical stability. Photonic circuits are sensitive to temperature. When a waveguide heats up by even a few degrees, its refractive index changes slightly, causing wavelength drift. That drift degrades performance.

Electronic circuits also suffer from thermal sensitivity, but they have over 60 years of engineering solutions: heat spreaders, thermal interfaces, cooling systems. Photonic chips don't have mature equivalents yet. You can't just bolt a heat sink onto an optical circuit—the thermal expansion itself causes problems.

Third, integration is hard. A practical photonic AI accelerator needs:

- Optical input interfaces (converting electrical signals to photons)

- Optical computational circuits

- Optical output interfaces (converting photons back to electrical signals)

- Electronic control circuits

- Memory systems

- Power delivery

Integrating all of this on a single chip, in a way that maintains optical performance while managing thermal, electrical, and mechanical constraints, is engineering at the very edge of what's possible.

ACCEL solved this partially through hybrid architecture—using electronics where they work, photonics where they help. Light Gen attempts full optical integration, which is more elegant but harder to manufacture.

Timeline reality: Most experts estimate 5-10 years before photonic AI accelerators see meaningful production volumes. Maybe 3-4 years for first commercial deployments in specialized applications (specific image generation platforms, perhaps). But mainstream adoption—photonic chips in every AI data center—is probably a 2030+ story.

Real-World Application Scenarios: Where Photonic Chips Could Actually Help

Let's move from theory to practical deployment.

Where could photonic chips create immediate value?

Image generation services (Midjourney-style platforms): These services receive millions of requests daily. Each request triggers image generation—a perfect photonic workload. A Midjourney-sized company could reduce inference costs by 70-80% by offloading generation to photonic hardware. They'd pass those savings to customers or capture them as margin improvement.

Video synthesis platforms: Frame-by-frame video generation is even more parallel-friendly than single-image generation. A photonic video synthesis engine could generate high-resolution video orders of magnitude faster than current methods. This is still largely inaccessible due to compute costs—photonic acceleration could unlock commercial viability.

Scientific visualization and computational imaging: Researchers using computational imaging (holographic reconstructions, phase retrieval, medical imaging) could benefit from photonic acceleration. These applications tolerate specialized hardware because the performance gain justifies it.

Real-time vision processing at edge locations: Deploying vision models in remote locations (surveillance, autonomous systems, robotics) is constrained by power. Photonic chips consuming 5% the power of GPUs could enable deployment scenarios currently impossible due to thermal dissipation.

Recommendation and filtering systems at massive scale: If you're Netflix processing billions of feature vectors to recommend content, photonic matrix multiplication could handle the compute requirements with significantly lower power. This hasn't been discussed much in research, but it's where photonic advantages could truly shine.

What photonic chips probably won't do well:

- Training new models (requires flexibility GPUs provide)

- Running multiple diverse models simultaneously (requires general-purpose scheduling)

- Research and development (researchers need flexibility to experiment)

- Small-scale inference (photonic chips have high fixed overheads)

The killer app for photonic computing will probably be something we haven't anticipated yet. When a new generative AI capability emerges that becomes compute-bound and constrained by power delivery, photonic acceleration will suddenly become essential.

Photonic chips offer significantly higher performance per watt compared to GPUs, with potential petaflop capabilities, but remain pre-commercial. Estimated data for photonic chips.

The Geopolitical Dimension: Why This Matters Beyond Technology

Chinese researchers developing photonic AI chips has triggered understandable geopolitical scrutiny.

Understand the context: Nvidia dominates GPU manufacturing almost completely. The company controls roughly 90% of the AI accelerator market. For Western companies, this dominance feels secure. For China, this dependency on foreign hardware is a vulnerability.

Photonic computing represents one pathway for China to reduce that dependency. If Chinese institutions can develop photonic chips that outperform American GPUs on relevant tasks, the dependency weakens. This isn't about stealing technology—it's about developing genuinely novel alternatives.

Let's be clear: the research appears legitimate. Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University are tier-one institutions. The published results are peer-reviewable. There's no indication of IP theft or unfair practices—just different institutions pursuing similar research directions.

But the geopolitical implications are real:

- China develops domestic alternatives to American hardware: Reduces dependency on US exports

- US loses export advantage in specialized AI chips: Less leverage on China trade policy

- Global AI capability distribution becomes less centralized: Multiple hardware platforms reduce Nvidia's influence

From a Western perspective, this is concerning if you believe tech dominance translates to geopolitical power. From a neutral perspective, it's healthy competition that will accelerate innovation.

From China's perspective, photonic chips are essential infrastructure independence. Over-reliance on Nvidia GPUs (or any foreign technology) creates strategic vulnerability. Developing alternatives, even if they're specialized, reduces that vulnerability.

The likely outcome: Continued parallel development of photonic computing in China and the West. Whoever achieves production viability first gets significant market advantage. This could be a genuine technological race, not geopolitical maneuvering.

Hybrid Futures: GPUs and Photonics Coexisting

The most realistic future isn't "photonic chips replace GPUs." It's "photonic chips and GPUs serve different roles in the same systems."

Consider a hypothetical AI inference cluster in 2028:

GPU tier (Nvidia H100s or successors): Handles diverse workloads, training, complex inference, anything requiring flexibility. Maybe 60% of the computing capacity.

Photonic tier (ACCEL or Light Gen successors): Handles high-volume standardized generative tasks. Image generation, video synthesis, specialized vision pipelines. Maybe 30% of the capacity.

Other accelerators (TPUs, quantum annealers, FPGAs): Specialized tasks requiring their unique properties. Maybe 10% of capacity.

System architecture becomes heterogeneous. Jobs route to the appropriate accelerator. The software layer abstracts away hardware differences from the application layer.

This heterogeneous approach has precedent. Data centers today use CPUs, GPUs, TPUs, and specialized accelerators for different purposes. The patterns are established. Integrating photonic chips follows proven architectural patterns.

The economics work out: If photonic chips cost 2-3x what GPUs cost per unit, but handle 20x more throughput on specific tasks, and consume 95% less power, they create value at specific capacity points. You add them where they're strong, keep GPUs where they're flexible.

Nvidia, recognizing this future, is hedging. They're investing in optical networking (fiber optic communication between GPUs). While not photonic computing per se, it's a related technology showing they're positioning for optical-based infrastructure.

The Research Reality: Laboratory Demonstrations vs. Real Products

It's worth being explicit about the gap between research papers and commercial products.

The papers describing ACCEL and Light Gen are genuine scientific contributions. The experiments appear well-designed. The performance measurements seem legitimate. But—and this is crucial—laboratory conditions differ dramatically from production deployment.

In the laboratory:

- Careful workload selection showing photonic strengths

- Optimized software specifically written for the hardware

- Controlled environmental conditions (temperature, vibration, electromagnetic interference)

- Small-scale testing (one chip, one experiment)

- Infinite time to debug and optimize

In production:

- Diverse, unpredictable workloads

- Legacy software that may not be amenable to photonic optimization

- Noisy data center environments with thermal cycling

- Massive-scale manufacturing with yield variability

- Need for instant-on reliability

This isn't saying photonic chips won't work in production. History shows that laboratory breakthroughs often become production systems. Quantum computers were laboratory curiosities before IBM and Google commercialized them. GPUs were research tools before Nvidia made them mainstream.

But the jump from prototype to production is where most promising research dies. Manufacturing challenges, thermal management problems, software incompatibilities, or market conditions can kill even technically impressive projects.

The honest assessment: ACCEL and Light Gen are impressive research. They demonstrate photonic computing is feasible. But we need to see successively more mature prototypes, larger-scale manufacturing, and real-world integration tests before celebrating them as solved problems.

Confidence levels:

- Photonic computing physics: 95% confidence this is viable

- Laboratory-scale demonstrations: 90% confidence results are accurate

- Production-scale manufacturing: 50% confidence this happens within 5 years

- Commercial deployment at meaningful scale: 40% confidence before 2030

Future Trajectories: Photonic Computing in the 2030s

Assuming photonic computing overcomes manufacturing challenges (which is a significant assumption), what does the 2030s landscape look like?

Conservative scenario: Photonic chips remain specialized research tools, adopted by 10-20 large companies for specific high-volume tasks. Total market probably under $1 billion annually. GPU dominance continues.

Moderate scenario: Photonic chips achieve production viability. Deployed in 50-100 companies for generative AI workloads. Market grows to $2-5 billion annually. GPUs remain dominant but lose market share to photonics for specific use cases. Power costs for large-scale inference drop 30-40%.

Optimistic scenario: Photonic chips become standard infrastructure. Major cloud providers (AWS, Azure, GCP) offer photonic-accelerated inference services. Photonic chips capture 40-50% of new accelerator spending. Nvidia adapts by buying photonic startups or developing competing products. Market consolidates around 3-4 major architectures (GPUs, photonics, and specialized alternatives).

Disruptive scenario: Photonic computing achieves breakthroughs beyond current narrow specialization. Becomes viable for broader AI tasks. Undermines Nvidia's GPU dominance. Market reshuffles significantly. This is the least likely scenario based on current physics, but scientific breakthroughs happen.

Most likely outcome? The moderate scenario. Photonic chips find niches, solve real problems, capture meaningful market share in those niches, and coexist with GPUs for years to come.

Comparative Advantage: When Photonic Beats GPU, and When It Doesn't

Let me create a clear framework for when each technology wins.

GPU advantages:

- Training new models (requires gradient computation, backpropagation)

- Inference on diverse models (requires flexible instruction set)

- Research and development (requires experimentation capability)

- Small batch sizes (photonic overhead dominates)

- Conditional logic and branching (photonic circuits struggle)

- Sequential decision-making (LLM token generation)

Photonic advantages:

- High-throughput identical operations (batch image generation)

- Matrix multiplication at massive scale (core photonic strength)

- Power-constrained deployment (edge, remote locations)

- Heat-dissipation-limited systems (where power efficiency matters most)

- Continuous signal processing (natural fit for photonic physics)

- Operations requiring massive parallelism (optical interference excels)

Neutral:

- Inference on trained models (both can work, depends on specifics)

- Low-latency requirements (both fast enough for most applications)

- Cost per unit (photonic cheaper per operation, but higher overhead)

The decision framework:

- Is your workload repetitive and standardized? → Consider photonic

- Do you need to run multiple different models? → Stick with GPU

- Is power consumption your primary constraint? → Seriously consider photonic

- Are you still experimenting with model architectures? → GPU is necessary

- Is this a high-volume, single-purpose pipeline? → Photonic could excel

Key Takeaways for Technologists and Investors

Let me synthesize what matters from all of this.

For AI engineers and infrastructure teams:

- Photonic acceleration is a real phenomenon backed by solid physics, not science fiction

- Current prototypes are specialized; don't expect them to replace GPUs broadly

- If your workloads include high-volume image/video generation, start tracking photonic developments

- Power efficiency will become increasingly important as AI scales—photonic solutions solve this

- Expect a 5-10 year timeline before production photonic hardware appears

For companies building AI products:

- Monitor photonic chip progress if you have specialized high-volume inference workloads

- Don't abandon GPU investment, but consider photonic partnerships for future infrastructure

- Energy costs will drive next-generation infrastructure decisions—be ready to explore alternatives

- First-mover advantage exists for companies that successfully integrate photonic acceleration

For investors:

- Photonic computing companies targeting AI are betting on real technology with real advantages

- Manufacturing capability is the critical differentiator—funding should prioritize this

- Exit paths are unclear (acquisition by larger chip makers most likely)

- Valuations should reflect 5-10 year timelines, not near-term commercialization

- Geopolitical dynamics favor investment in photonic alternatives to GPU dominance

For researchers:

- Photonic AI is still in early research stages despite recent breakthroughs

- Fundamental challenges (thermal stability, manufacturing precision) remain unsolved

- Hybrid architectures (mixing photonic and electronic) may be more practical than pure photonic

- Software and algorithms optimized for photonic hardware are under-developed—huge opportunity

FAQ

What are photonic AI chips?

Photonic AI chips are processors that use light (photons) instead of electrical current (electrons) to perform computation. They combine optical components like waveguides and photonic neurons with traditional electronic circuits to accelerate specific AI workloads, particularly generative tasks like image synthesis and video generation.

How do photonic chips achieve 100x speed improvements over GPUs?

The 100x speed improvement comes from using optical interference for massive parallelism. Light can perform billions of operations simultaneously through interference patterns, whereas electronic processors execute operations sequentially or in limited parallel streams. However, this speed advantage only applies to narrowly defined tasks that map well to optical operations—not general-purpose computing.

What makes ACCEL different from Light Gen?

ACCEL is a hybrid system combining photonic and analog electronic components, developed at Tsinghua University, optimized for image recognition and vision processing. Light Gen is an all-optical system with over 2 million photonic neurons, developed by Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Tsinghua University, targeting generative AI tasks like image generation and style transfer. The key difference is integration approach—hybrid versus pure optical.

When will photonic AI chips be commercially available?

Based on current development timelines, first commercial photonic AI accelerators could appear within 3-5 years for specialized applications. However, widespread deployment across the industry likely won't occur until 2030 or later. Manufacturing challenges, thermal management, and software optimization remain significant hurdles.

Can photonic chips replace Nvidia GPUs?

No. Photonic chips are specialized for specific high-throughput tasks, while GPUs are general-purpose accelerators. The realistic future involves heterogeneous systems where GPUs handle diverse workloads and photonic chips handle specialized high-volume inference. Both technologies will coexist, each optimized for different roles.

Why is power consumption so much lower in photonic systems?

Photons don't generate heat through resistance the way electrons do in semiconductors. Once created by a light source, photons traverse optical circuits with minimal energy loss. This fundamental physics advantage means photonic systems consume 10-50x less power than equivalent electronic systems for comparable workloads.

What are the main challenges preventing photonic chip commercialization?

Key challenges include manufacturing precision (photonic circuits require nanometer-scale accuracy), thermal stability (wavelength drift from temperature changes causes performance loss), integration complexity (combining optical and electronic components), and the need for new software optimized for photonic hardware. Solving these problems requires years of engineering development.

Which companies and institutions are developing photonic AI chips?

Tsinghua University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University are leading Chinese institutions with published research on ACCEL and Light Gen respectively. Multiple Western research institutions and startups are also pursuing photonic computing, though commercial products haven't emerged yet. Major semiconductor companies are monitoring the technology but haven't committed significant resources to commercialization.

What types of AI tasks benefit most from photonic acceleration?

Photonic chips excel at image generation, video synthesis, vision processing, and other tasks requiring massive parallel matrix multiplication. They're less suitable for natural language processing, reinforcement learning, or any workload requiring conditional branching and sequential decision-making. The key criterion is whether the task maps naturally to optical interference patterns.

How do photonic chips impact data center economics?

If photonic chips achieve production viability and cost parity with GPUs, they could dramatically reduce operational costs. A 20x reduction in power consumption translates to hundreds of thousands of dollars in annual electricity and cooling savings per data center. This economic advantage alone could drive adoption even if photonic chips remain specialized.

Final Thoughts

Chinese researchers claiming 100x speed improvements over Nvidia GPUs triggered skepticism—rightfully so. The tech industry has seen plenty of overhyped breakthroughs that never left the laboratory.

But photonic AI chips aren't hype. They're legitimate physics with real engineering implementations. The speed gains are genuine, though narrowly scoped. The energy efficiency advantages are dramatic and measured. The path to commercialization is uncertain, but it's not blocked by fundamental physics limitations.

What we're watching is early-stage paradigm shift in AI hardware. GPUs solved the parallel computation problem brilliantly. Photonic chips solve a different problem: ultra-high-throughput specialized computation with minimal power consumption.

The next decade will reveal whether this shift reaches mainstream adoption or remains a specialized tool. My best guess? Photonic chips become standard infrastructure by 2032, handling 30-40% of large-scale AI inference workloads. GPUs remain dominant overall, but lose the perceived monopoly on AI acceleration.

For anyone building AI infrastructure or considering long-term technology bets, photonic computing deserves serious attention. Not as a GPU replacement—that's not happening. But as a complementary technology solving real problems that GPUs handle inefficiently.

The most interesting technology often isn't the general-purpose solution. It's the specialized solution that does one thing extraordinarily well. Photonic computing appears to be that specialized solution for AI's future.

Related Articles

- Airloom's Vertical Axis Wind Turbines for Data Centers [2025]

- NVIDIA CES 2026 Keynote: Live Watch Guide & AI Announcements

- AI Predictions 2026: What's Next for ChatGPT, Gemini & You [2025]

- Meta Acquires Manus: The AI Agent Revolution Explained [2025]

- AI Budget Is the Only Growth Lever Left for SaaS in 2026 [2025]

- Google Photos on Samsung TVs 2026: Features, Timeline & Alternatives

![Photonic AI Chips: How Optical Computing Could Transform AI [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/photonic-ai-chips-how-optical-computing-could-transform-ai-2/image-1-1767477965641.jpg)